ISSUE 03 2009 A HOUSE RE-CRAFTED COLOUR & LIGHT THE BEST NEW SIDEBOARDS POOLE’S DESIGN FOR TRACEY MOFFATT MOD LIVING IN SINGAPORE GOLLINGS: BEYOND THE LENS NZ’S MARSHALL COOK THESEUS CHAN – GRAPHIC DESIGN REBEL NEW DINING FURNITURE SOUTH AMERICA – DESTINATION URUGUAY CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN HOMES AUD $12.95 NZ $13.95 USD $15.95 CDN $16.95 GBP 8.50 SGD $10.95

For more information on Miele’s impeccable fleet design range of ovens, rangehoods, microwave combi ovens, cooktops, plate warmers, steam ovens, coffee machines, dishwashers and refrigeration contact the specialist Project Division in your state. VIC 03 8633 8335 NSW 02 8977 4235 QLD 07 3632 2471 SA 08 8352 9500 WA 08 9286 7800 NZ 09 573 1269 www.miele.com.au TRP MI 1218

Because great coffee should be up there with great food, our machines are built in, next to our ovens.

Built into your kitchen, a German engineered Miele coffee machine makes a clear statement of streamlined, good taste – along with impeccable espresso, cappuccino or latte macchiato, all with perfect Barista crema.

Hey,it’sonlynatural. puretann ® VegetabletannedPureAnilineLeather OnlythefinestBavarianhidesareselectedforPuretann®. Eachuniquehideistannedonlywithextractsfrompodsofthe Taratree,growninthetemperateclimateofthePeruvianAndes. ThisgivesPuretann® anunbelievablysoft,luxuriousfeeland appearance. AvailableexclusivelyfromContemporaryLeathers.

c contemporaryleathers contemporaryleathers www.contemporaryleathers.com.au c yescommunications

Casamilano

Made in Italy

Images shown: Pillopipe sofa/pouf, Ray table lamp, Jackie floor lamp, Sissi armchair.

To view the full Casamilano catalogue and more go to www.fy2k.com.au

FY2K 17 Thurlow St, East Redfern, Sydney Ph +61 2 8399 1644 info@fy2k.com.au

Zip HydroTap® at home. Imagine. Imagine. No more waiting for water to boil. No more bottled water to buy. Zip HydroTap gives filtered boiling water and filtered chilled water instantly. For a free quotation call 1800 42 43 44 or visit www.zipindustries.com The terms ‘HydroTap’ and ‘Zip’ are trade marks. Instant Boiling Water

1. HABITUS REVIEWS

I CELEBRATE THE BEST IN DESIGN – BOTH CLOSE TO, AND FARTHER FROM, HOME. READ ABOUT THE LATEST BOOKS. TAKE A LOOK AT DESIGNER SIDEBOARDS AND CONTEMPLATE BUYING A CLASSIC CAR.

23

DeSign newS

Habitus takes you through the latest and most exceptional design objects for the home, the office, for travel and for children.

32 re-SHoot

We celebrate the reinvention of the sideboard and take a fresh look at this multi-purpose essential.

35 conVerSation

Kirsty de Garis gets behind the wheel at Rory Johnson’s Classic Throttle Shop and discovers why design enthusiasts the world over are excited about classic cars.

47 inSPireD

Australian architectural photographer, John Gollings, has taken decades to hone his craft, based on a love of form. Stephen Crafti examines Gollings’ own inspirations – with surprising results.

64 on location

Malaysian-born fashion designer Grace Tan calls Singapore home these days. Darlene Smyth gets the inside track on Tan’s life in her new home town, a melting pot of local cultures and creative influence.

86

Slow DiSSolVe

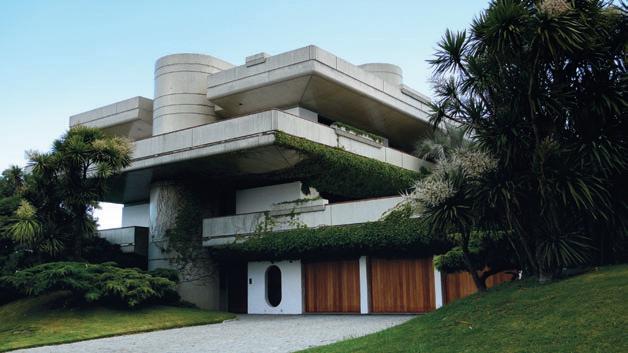

Australian-born Richard Goodwin took a long time to decide whether he was an artist or an architect – or is he both? Paul McGillick meets the enigmatic visionary.

3. HABITUS HOMES

I A DIVERSE SELECTION OF THE BEST IN RESIDENTIAL DESIGN FROM AUSTRALASIA AND SOUTH-EAST ASIA.

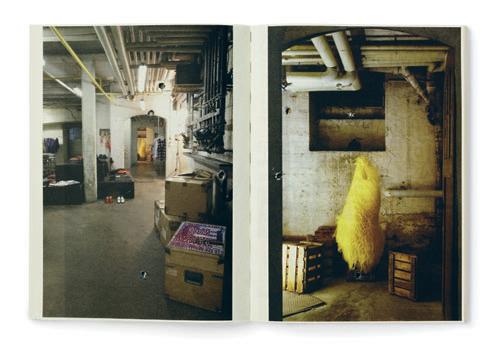

72 creation

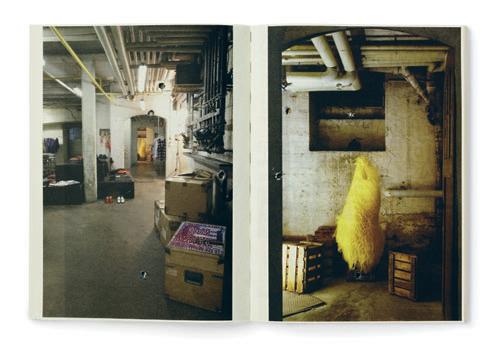

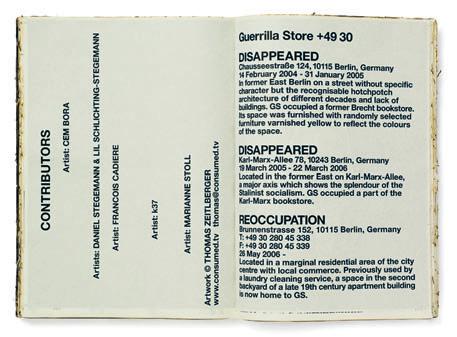

Theseus Chan has come a long way from his life as an electrical engineer industrialising Singapore. The graphic designer shares his thoughts with Darlene Smyth.

52 at Home

Jac + Jack knitwear designer, Jac Hunt, lives in a style that is a wacky, colourful and eclectic departure from her minimalist creations. Kirsty de Garis reports.

99

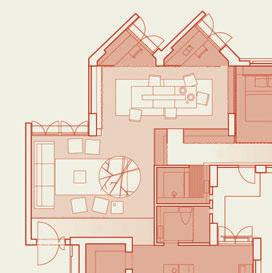

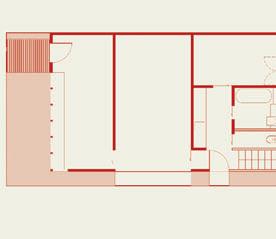

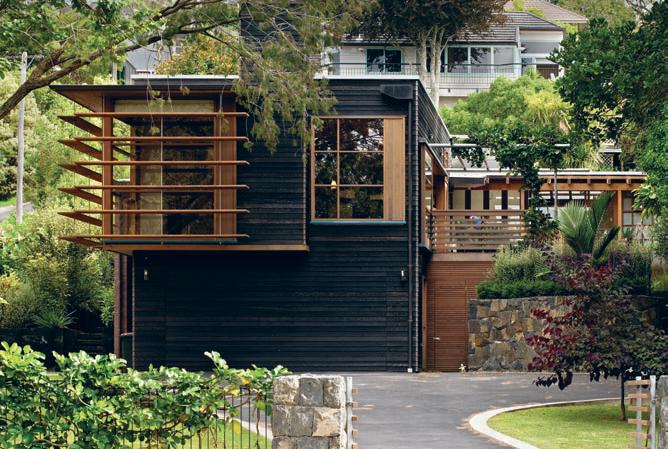

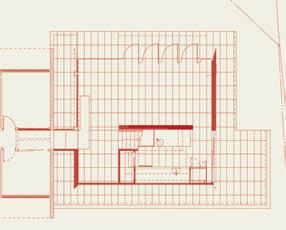

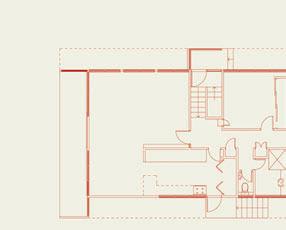

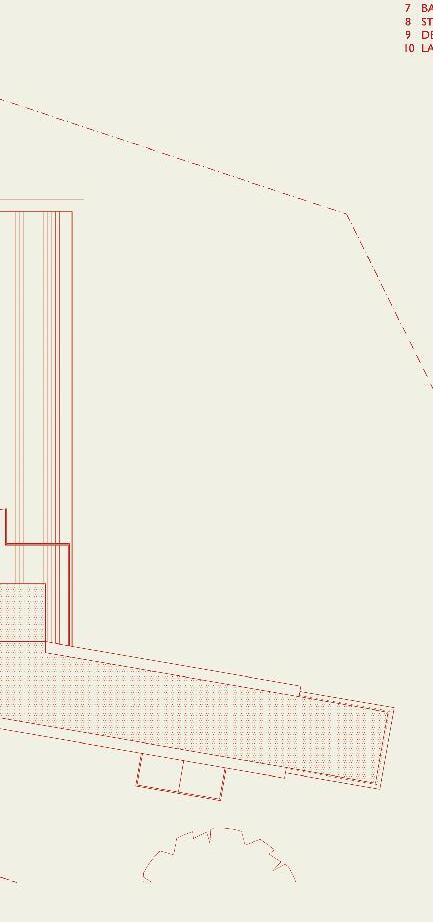

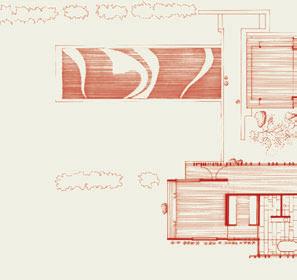

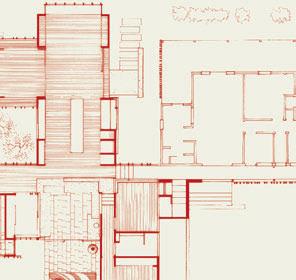

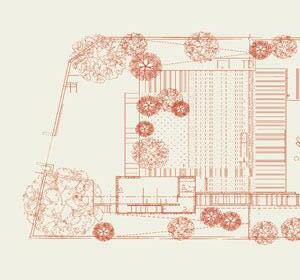

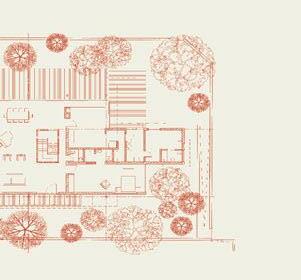

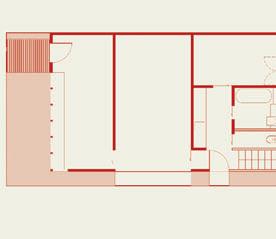

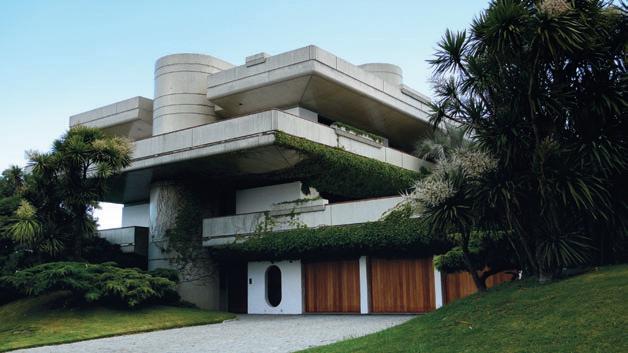

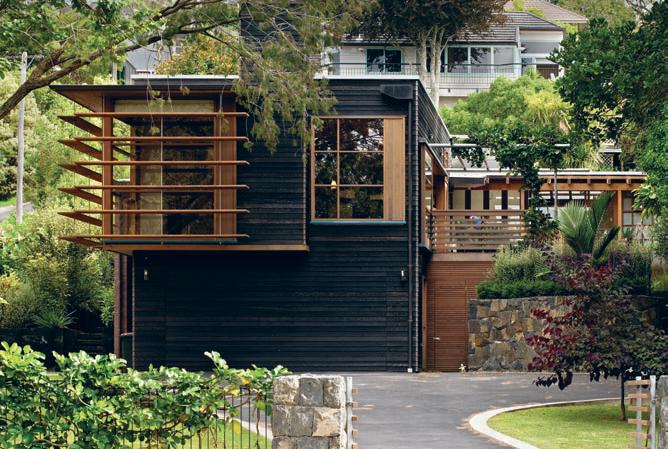

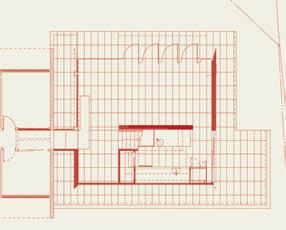

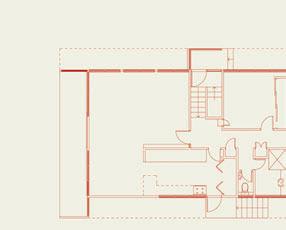

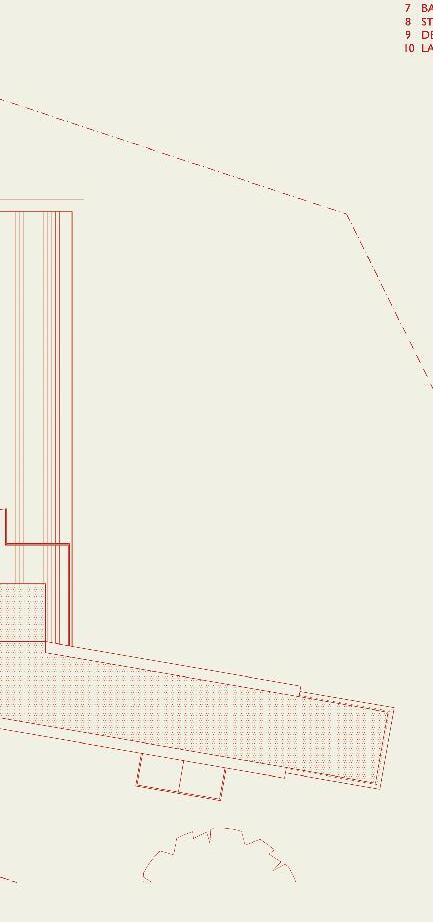

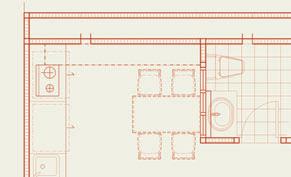

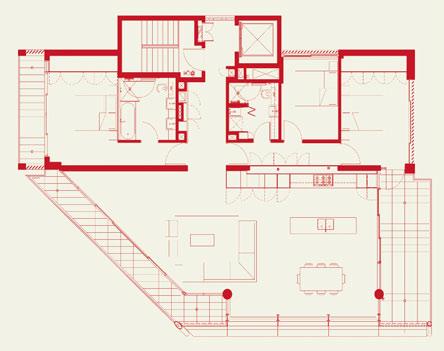

Scenario: corintH Street

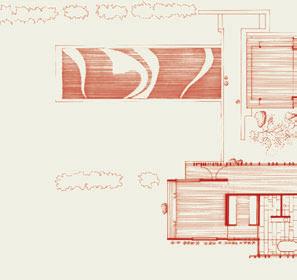

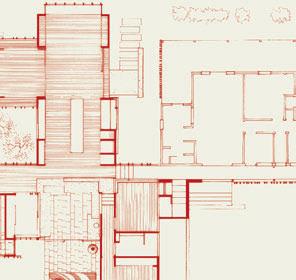

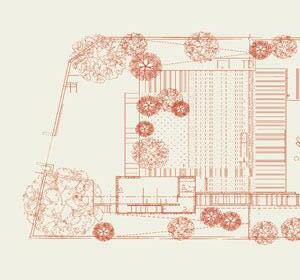

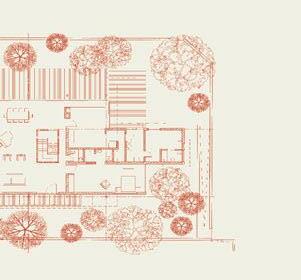

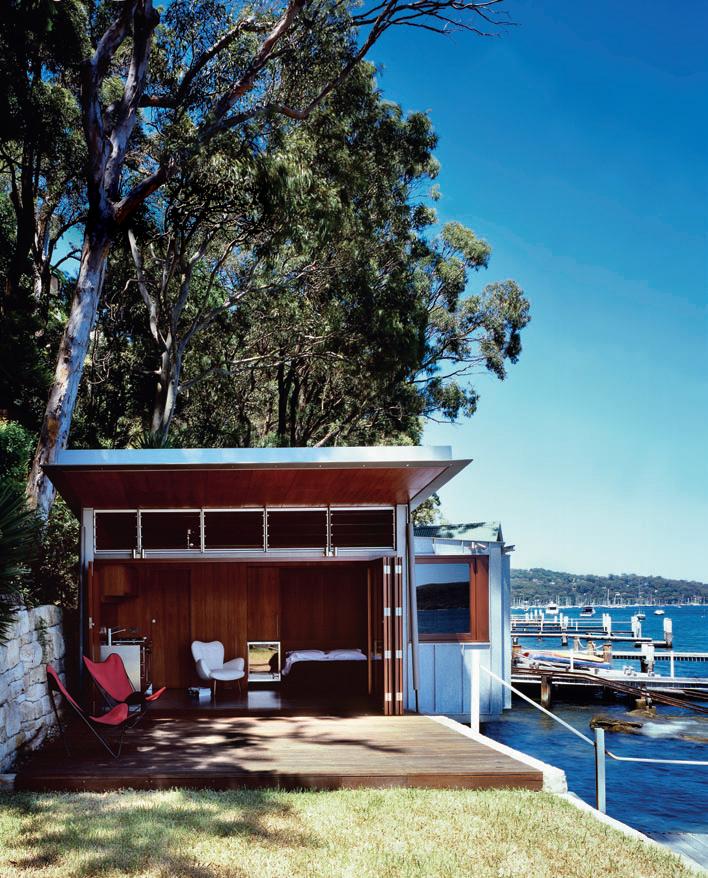

Andrea Stevens talks to Aucklandbased architect Daniel Marshall and his clients, the McCabe family, about the contemporary renovation of a classic post-War home design.

39 montage

Philip Drew is inspired by three new books to reflect on the importance of hand drawing in architecture.

2. HABITUS PEOPLE & PLACES

I MEET A COLLECTION OF DESIGN ADVENTURERS WHO HAIL FROM SOUTH-EAST ASIA AND AUSTRALASIA, AND SEE HOW THEIR ENVIRONMENTS REFLECT THEIR LIFE AND WORK.

76

cloSe UP

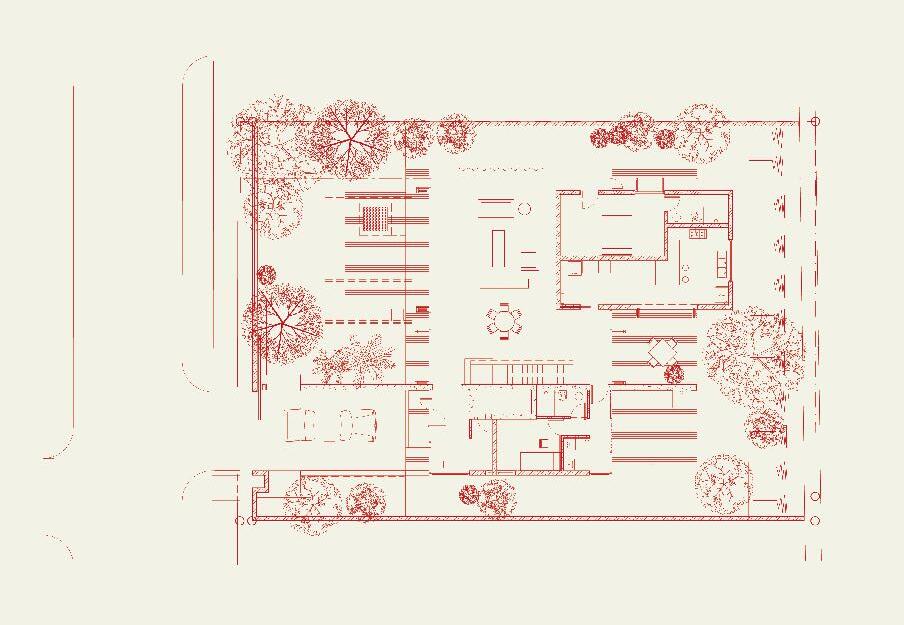

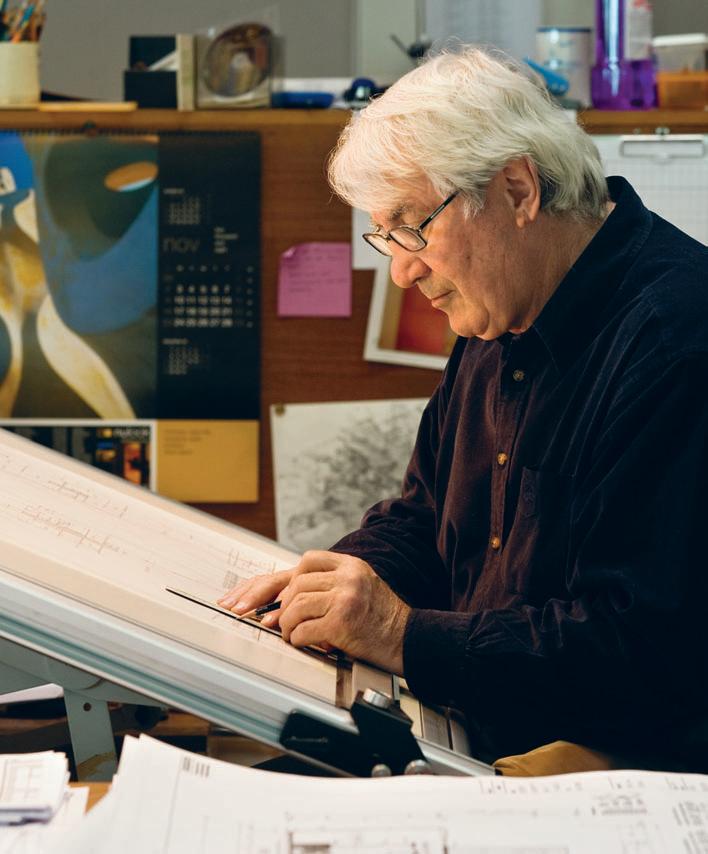

Truly a Pacific Rim architect, Marshall Cook draws on his travels around the far-flung islands of his native New Zealand and beyond to create an authentic Kiwi flavour in his work. Andrea Stevens reports.

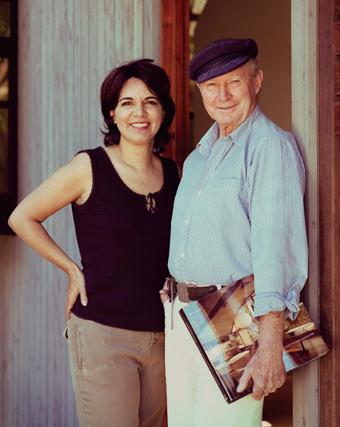

59 PartnerSHiP

21 years ago, Steve and Pat Ronayne found themselves in the Adelaide Hills almost by accident. The result is a delightful local gallery of international standard, housed in a reinvigorated church.

110

Scenario: manSfielD loDge

In the high country of rural Victoria, Nicky Lobo visits this family holiday retreat, which embodies the elements of style that are the hallmarks of great design.

habitus | Issue 03

07

contents

121

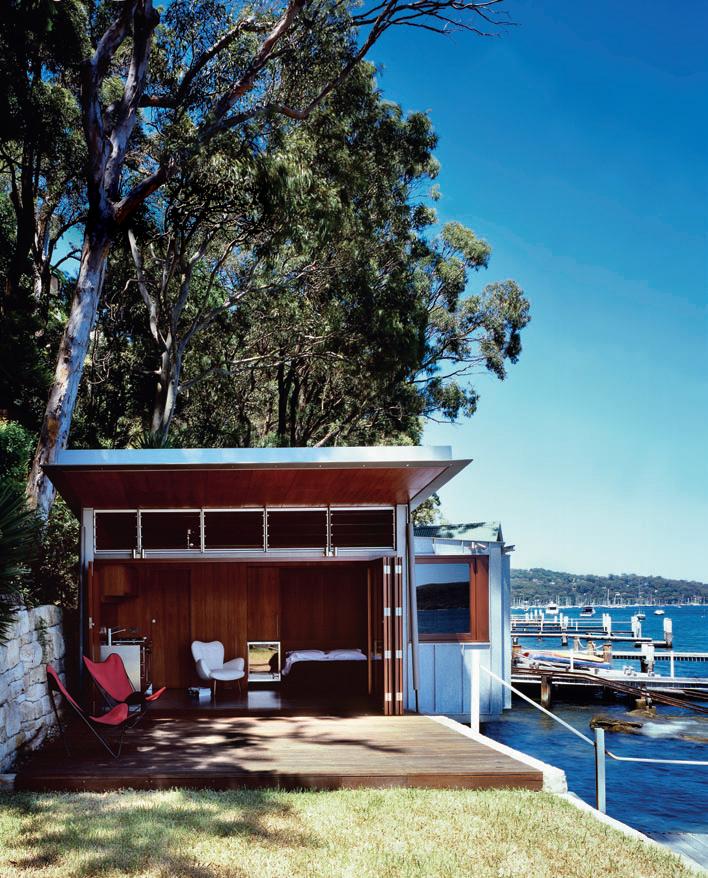

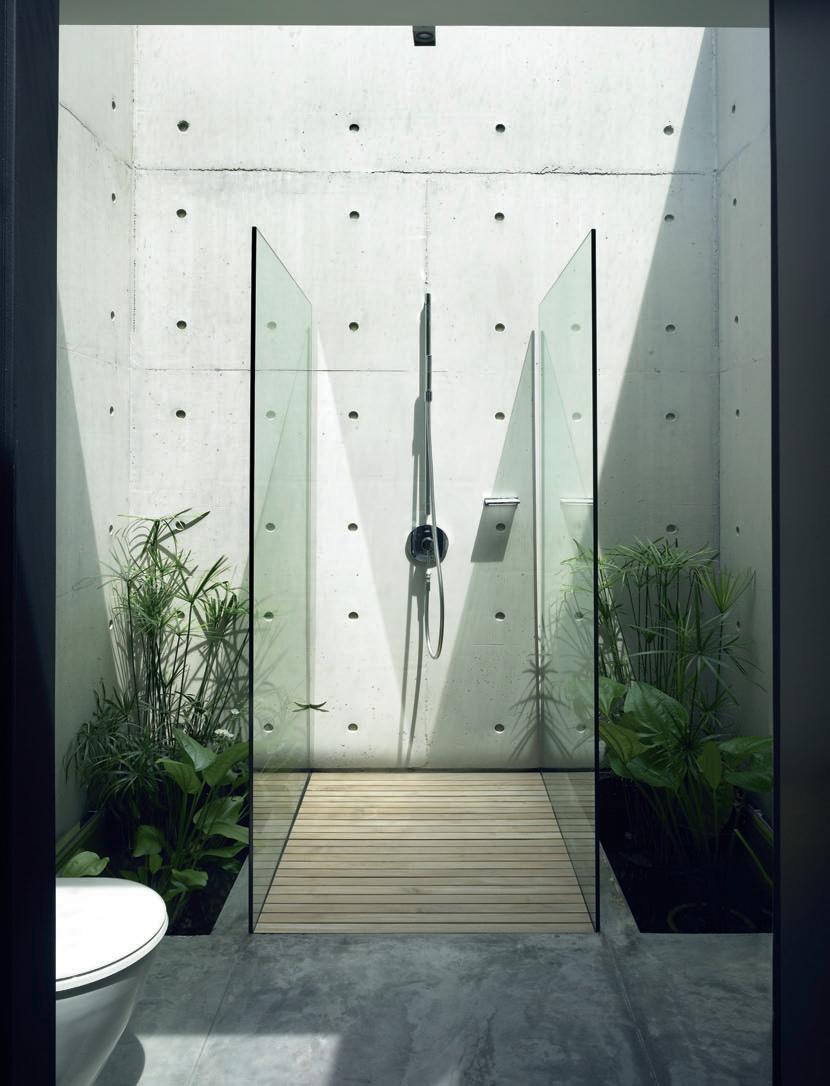

sCENARIO: whAlE bEACh

The owners of this Whale Beach, home sought a result that they could hose down, in keeping with the archetypical beach house. Heather Barton investigates.

147

sCENARIO: multIplICIty

Stephen Crafti guides us through this dynamic blend of architectural styles in Melbourne’s Hawthorn, where a family lives in harmony.

131

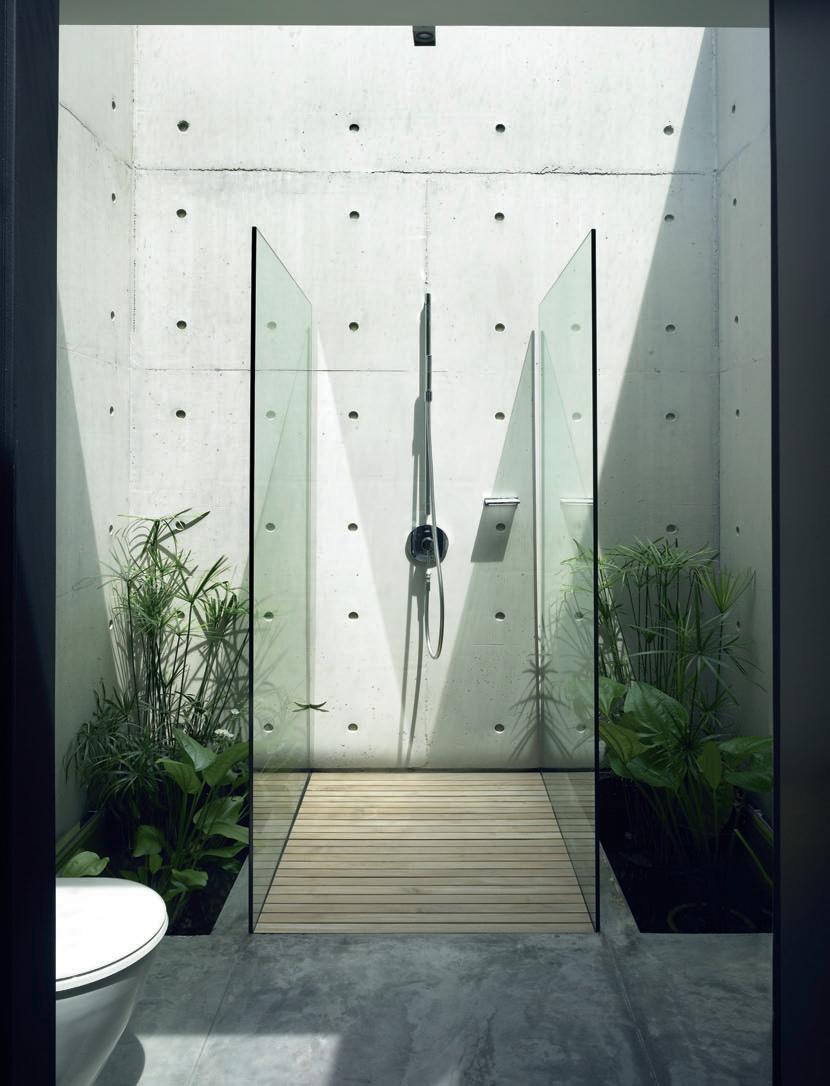

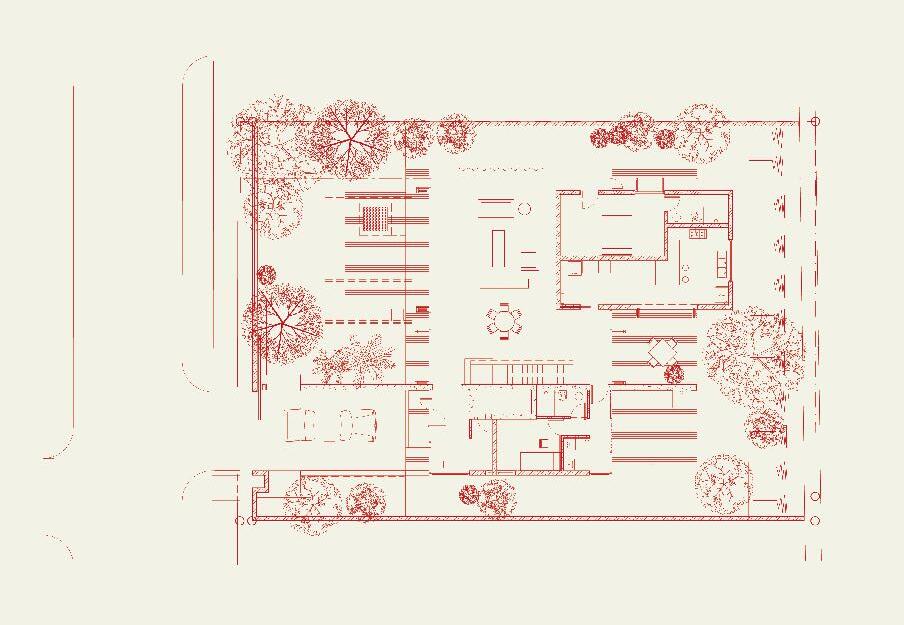

sCENARIO: CODE hOusE

Nestled in the steaming backstreets of Bangkok’s bustling heart, this bold architectural gem embodies the realisation of dreams both for the Thailand of old – and the new.

138

sCENARIO:

m AROub RA A pAR tmEN ts Sydney architect, William Smart, interpreted the rocky coastline at Maroubra in a dazzling new way with this four-storey apartment building, dressed to thrill.

157

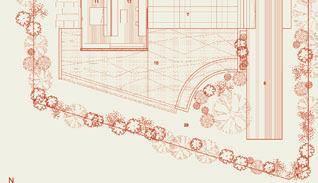

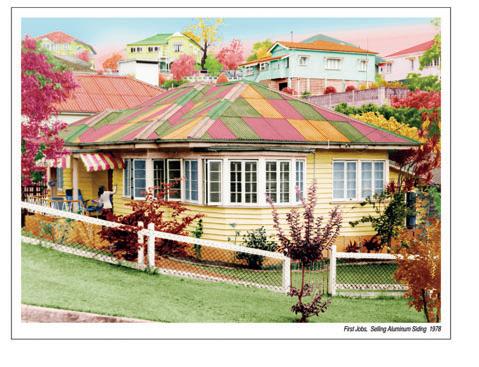

sCENARIO: NA’s hOusE

On the green outskirts of Brisbane, Margie Fraser reports on a creative blend of Asian sensibilities with the vast, open Australian landscape.

175

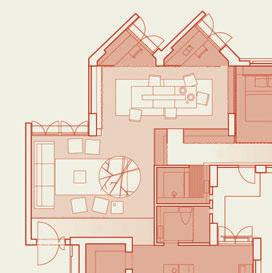

DIRECtORs Cut: COlIN sEAh

Colin and Joy Seah approached the interior design of their first home purchased as a couple with an almost sacred joy. Andrea Stevens savours the benefits of their work.

184

DIRECtORs Cut: bEllEmO CAt

Peter Hyatt explains how partners, Michael Bellemo and Cat McLeod, have renovated their Melbourne warehouse to house their home and work lives in one exceptional space.

202

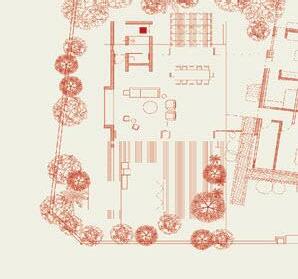

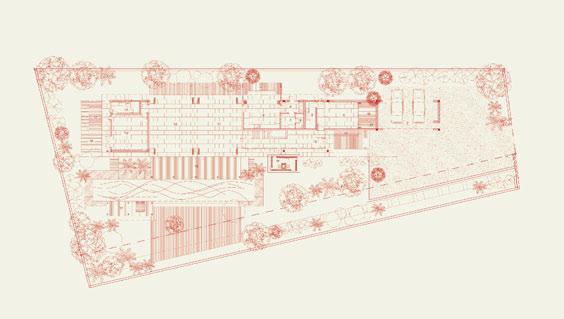

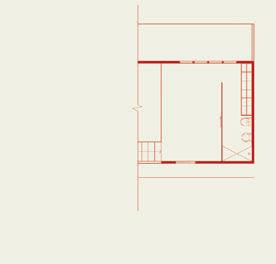

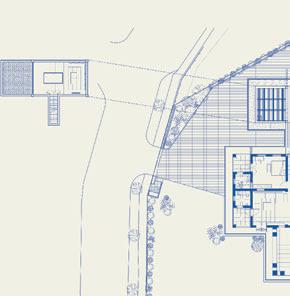

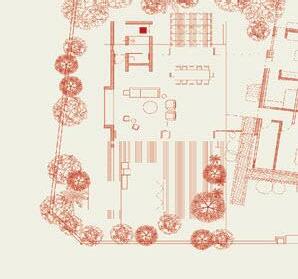

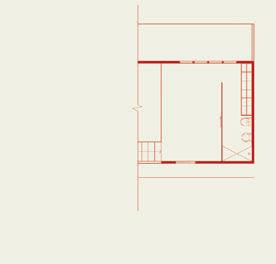

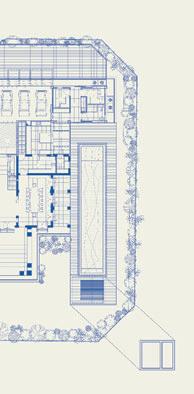

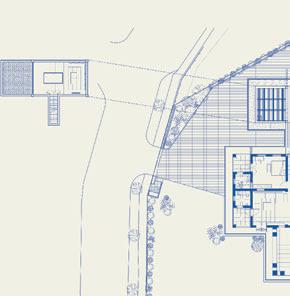

Jump Cut: CsyA

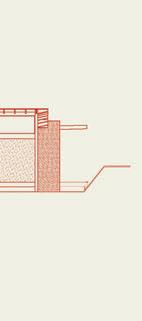

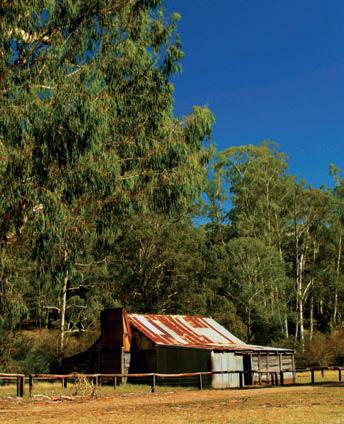

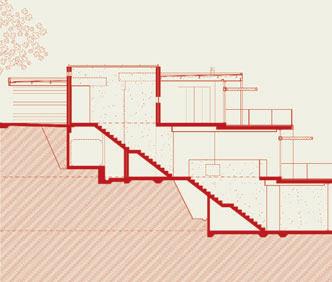

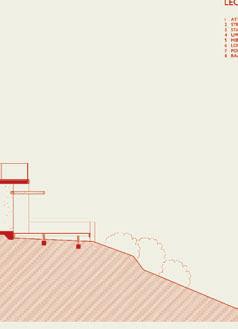

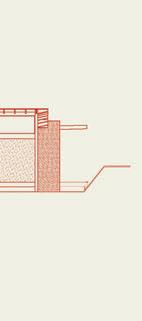

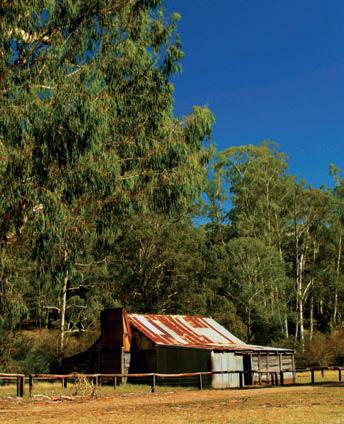

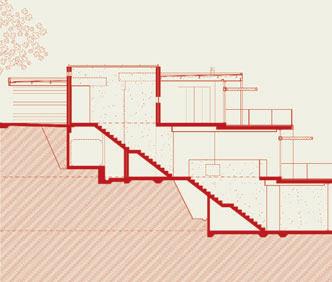

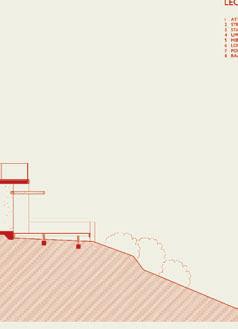

Singaporean architect Chan Sau Yan’s design approach is entirely dependent upon the site he’s presented with Darlene Smyth examines a renovated barn-style dwelling and a bungalow addition.

4. HABITUS SIGN-OFF VISIT INSPIRATIONAL SPACES FROM ACROSS THE REGION, MARVEL IN THE BEAUTY OF THE IDEAL DINING SETTING, AND FLOAT AWAY ON A URUGUAYAN ODYSSEY OF LOVE.

216

spACEs wE lOVE

A collection of diverse spaces from the Region, with water at their heart.

224

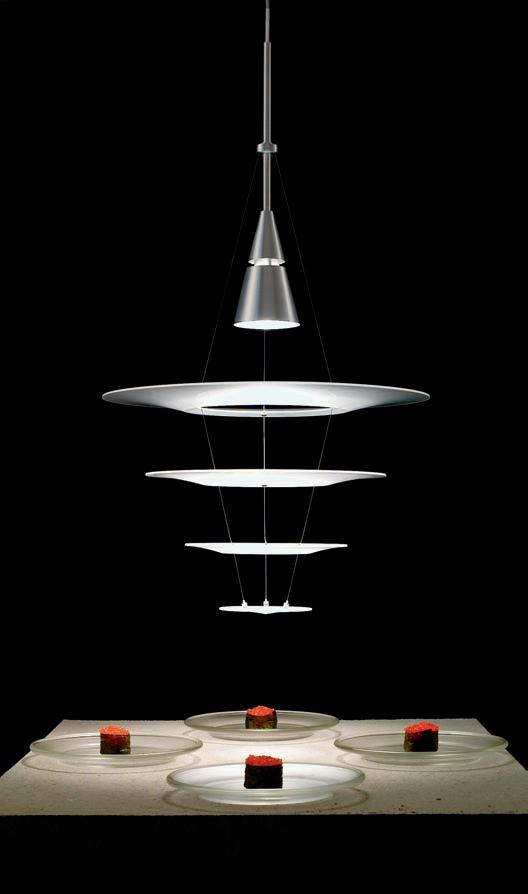

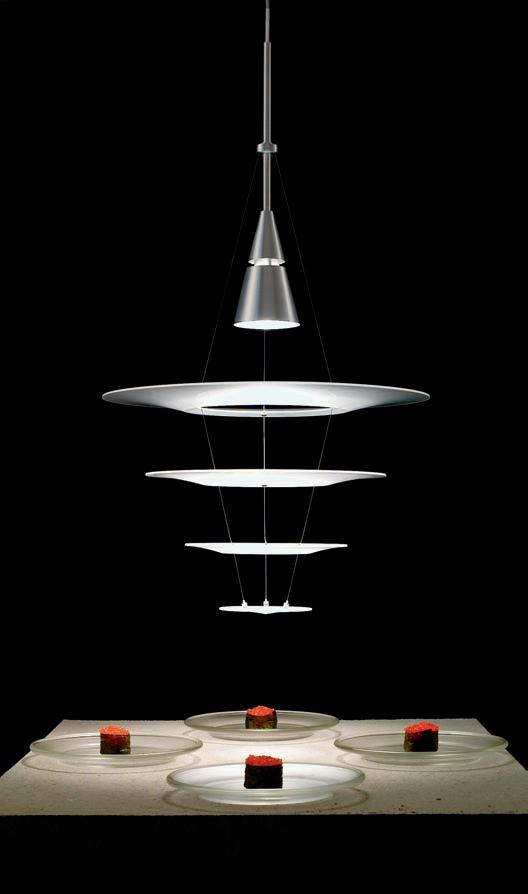

IN CAmERA: DININg

Rethink one of the most luxurious rooms in the home – designed for pleasure. The best in dining settings.

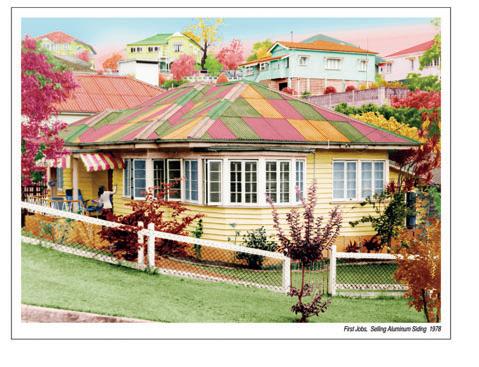

192

hOmE mOVIE: tRACEy mOFFAt

Once Manhattan-based, artist Tracey Moffatt now divides her time between the Big Apple and this tranquil Queensland retreat, designed by one of her heroes, Gabriel Poole. Margie Fraser visits.

166

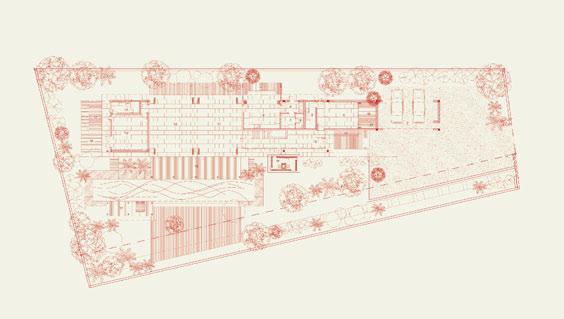

CROss FADE: kAmpuNg hOusEs

Chu Lik Ren investigates four dramatically different takes on the re-thinking of the traditional Singaporean Kampung house.

232

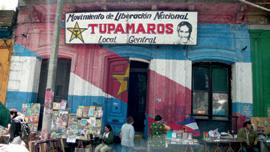

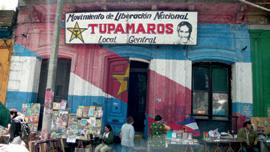

sNAp shOt: uRuguAy

Andrea Millar travels to the South American country of her birth and reveals exciting design finds, both in Montevideo and off the beaten track.

contents habitus | Issue 03 08

KOS

84 O’Riordan Street Alexandria 8339 7000 103–123 Parramatta Road Auburn 9648 5411 bathroom design centre

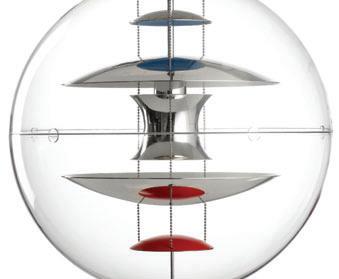

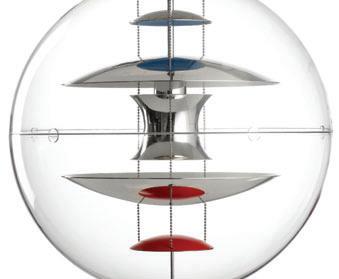

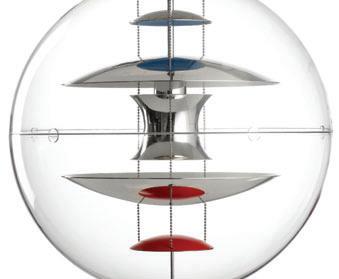

Introducing the Corporate Culture Lighting Collection

Warm your turbo heart. Saab 9-3 Convertible.

Performance. Design. Together as one. To empower the senses. All of them. Open your eyes. Feel. Touch. Listen. Saab 9-3 Convertible. Designed with you in mind. And inspired by Scandinavia. Where nature’s elements affect daily life. Making it a true four-season, four-seater convertible. That’s sporty. Elegant. And exhilarating. Even standard features are innovative. Enjoy heated front seats. Automatic climate control. So you can avoid the cold. Even with the roof down. It’s everything your turbo heart desires. No compromises. The heart of every Saab is its turbo. Experience it with a test drive. Call 1800 50 7222 or visit saab.com.au

SAA27861/HAB

Ask any architect and they will tell you that great architecture only happens with great clients. Actually, that’s the case with all design, because it is the clients – consumers, buyers, punters, players, call them what you will – who give permission to the designers to be genuinely creative.

This is all about vision. The client has a vision. It may not be clear or articulated. It is probably just a general vision of how they want to live. But where it is most particular is in its passion to live a life of quality –to reject the mediocre in favour of uniqueness, and to have the courage to try something new and different.

This doesn’t have anything to do with following fashion blindly. That is for the herd and for those who would rather have other people think for them. People with a real passion for quality design are looking for houses and products which align with who they are and what matters to them.

Enter the architect stage right; the designer stage left. Prompted by the passion of their clients, they now have permission to play with possibilities, play with place and play with the personalities of the clients who will be their collaborators on the journey.

This is why Habitus gives air time to the people who live in the houses, who furnish them, decorate them, landscape them and generally enjoy them. Our agenda is to tell the stories of all those collaborations which go to make up a life of quality and value. Albert Einstein once remarked: “Do not try to be a successful man. Try to be a man of value.”

We are interested in the values that people invest into their lives and how these find expression in the houses they have designed for them, for all those products which give their lives texture.

More or less any of the stories in this issue of Habitus would illustrate my point. But take Na’s house in Brisbane as an example. Here the architect, in close collaboration with her clients, has not only created an extension which successfully blends old and new, but also manages to embody Thai and Japanese elements which express the origins and history of the family.

Or take the Corinth Street house in Auckland, the Bellemo Cat house in Melbourne, Colin Seah’s own apartment in Singapore’s Little India or the remarkable Code house in Bangkok – all of them are architectural expressions of the way of life of the people who live in them, all of them are furnished and are decorated with art works which tell the story of the people who live there and all become a statement of what is most important to the people who live in them.

Stories lie at the heart of all human experience. Habitus tries to tell some of those stories.

15 paul mcgillick editor’s letter habitus | Issue 03

Paul McGillick, Editor

I The client has a vision. Where it is most particular is in its passion to live a life of quality.

I This is why Habitus gives air time to the people who live in the houses,who furnish them, decorate them, landscape them and generally enjoy them.

Darlene Smyth

Writer

For this issue of Habitus, Darlene Smyth wrote the story on Theseus Chan on page 72. She says: “Despite feeling like a knock-kneed teenager auditioning for the school drama club, I found it truly refreshing to have met such a colourful, inspired professional who, despite his years of experience, does not seem to have lost any of the joy and youthful innocence in his artistic creation.”

a aron Pocock

Photographer

Born in NZ, Aaron attempted several different career paths (including architecture) until he discovered photography. He shot one of the Jump Cut projects on page 202 of this issue. Aaron lives with his actor girlfriend in a classic art-deco apartment in the leafy suburb of Hawthorn in Melbourne’s inner east. Aaron’s favourite object at home is his hand-made 7’6” Ashley surfboard – it’s perfectly designed for his height, weight (and skill), and beautiful to look at from any angle.

h an S SchluPP

Photographer

Hans shot Na’s House, a Scenario story in Brisbane on page 157 of Habitus 03. He has humble plans for 2009 – to spend more time at home. And his inspirations are also very close to home: Hans says he gets a kick out of assistants coming to his studio and teaching him new and interesting photography tricks.

c hriS Jone S

Photographer

Chris, who has barely put his camera down since his passion for photography was ignited while travelling 12 years ago, shot Tracey Moffatt’s house on page 194. He lives with his wife, Carla, on an acreage north west of Brisbane and loves the recently completed ‘pod’ studio extension to his house, which references the surrounding bush.

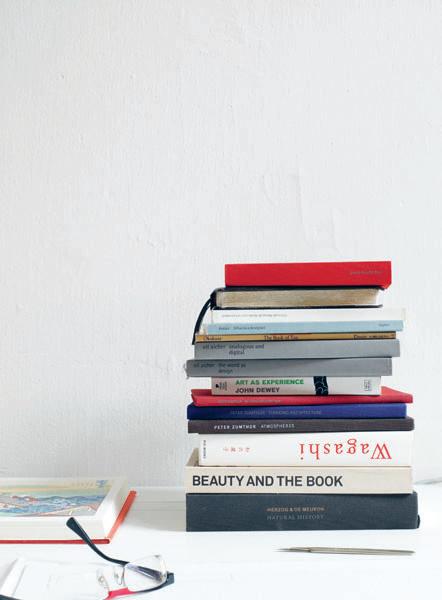

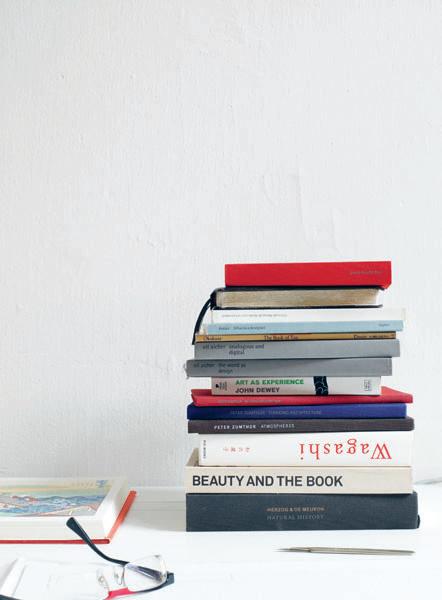

a lina Gozin’a

Photographer

You can see Alina’s artistic approach to photography in the Conversation story on page 35. She lives in Sydney’s Potts Point where, “on Macleay Street, I can pretend I am in Europe – the cafés, the trees and the street buzz”. At home, Alina loves her Tower of Knowledge bookshelf by Peter Mortiz because it’s easy to dust and in 2009 Alina will direct her next short film, expand her shoe collection and exhibit On Both Sides of the Camera –a collection of portraits of people who work in the film industry.

Derek Swalwell

Photographer

Derek lives with his partner, Georgia, and young daughter, Mia, in a funky 1950s apartment in Caulfield, Melbourne. He shot the Multiplicity project on page 147 and also travelled to shoot Grace Tan for the On Location story on page 62. Derek loves to look at his 1970s Chiswell sideboard, saying, “they just don’t make ‘em so authentic anymore”.

e ric Sieren S

Photographer

Eric lives in a 100-year-old semi in Sydney’s Crows Nest but shot something a little more modern for this issue: a house in Whale Beach on page 121. He lives with graphic designer wife, Emma, and two children, Sonicka and Andrej. He says: “the house barely survives a semi-demolition by the kids so there isn’t much left by way of design.”

a laana fitz Patrick Writer

Alaana contributed to the Design News pages of Habitus 03 from her new home in London. She is thoroughly enjoying all that the city has to offer, and will spend at least part of 2009 exploring Europe. Having packed light for the move, she doesn’t have much in the way of design with her, but her favourite object is a Tord Boontje-designed garland, which she has draped over a lampshade.

Sam noonan Photographer

Living in the Adelaide Hills with wife, Sophie, and daughter, Hannah Aurora, Sam didn’t have to travel far to shoot Steve and Pat Ronayne of Aptos Cruz for the Partnership story on page 57. Sam’s favourite object is his handcrafted and well-used Laguiole knife for its simple beauty, sentimental value and corkscrew.

a lbert l im Photographer

Albert shot the kampung houses in the Cross Fade story on page 166. He lives on the east coast of Singapore in a house/ studio designed by Richard Ho Architects that won an SIA Award. Last year, Albert completed an exhibition on the theme of “man and environment” and he loves the lightwell in the middle of his house. “I enjoy the light change every time I pass by it,” he says.

m arG ie fra S er Writer

Margie was able to indulge in her first love, writing, for the Na’s House Scenario story on page 157. She lives in Brisbane next to the bush and mountains and can see Moreton Bay on a clear day. Her children are intermittent residents, but Margie and her husband hold the fort while they’re away travelling. She loves her Lloyd Kwilla painting, which she bought on a recent trip to Australia’s Kimberley region, and plans to explore Egypt this year.

S Pace S hift Stu Dio Photographers

Multi-tasker Pirak

Anurakyawachon flexed his photographic muscles on the Code House story on page 131, for which he also wrote the text. He and his partner Aranyarat Prathomrat say their signature in photography is “not only to take pictures of buildings or design objects, but also to clarify the creativity and imagination of those creators into frames”.

heather barton

Writer

Heather, who wrote the text for the Whale Beach story on page 121, lives in Darling Point, Sydney with husband, Paul, and seven-year-old son, Turlough (Tully). They spend a lot of time in nearby Rushcutters Bay Park where Tully gets very spoiled by the staff at the park’s café. Heather loves her reindeer skin, saying it is “intelligent design and feels wonderful in a barbaric sort of way”.

k

Writer

For this issue of Habitus, Kirsty wrote the At Home story on page 52 about Jac + Jack designer Jackie Hunt. This year Kirsty will be busy in the middle of nowhere on South Australia’s Yorke Peninsula writing a feature-length film script. She gets a kick out of beautiful design and admires “people who live courageously, something my husband does with aplomb”.

Peter h yatt

Writer / Photographer

Peter wrote and shot the Bellemo Director’s Cut story on page 184. He lives in a Victorian-style house with partner, Jennifer, and two daughters, Ella and Sunday. His favourite object at home is a turn-of-the-19 th-century Italian bust that expresses a beautiful poise and elegance. Peter says of 2009: “Who knows? It’s a year at a time and a step at a time.”

Paul l ovelace

Photographer

Paul wants to make time this year to spend on his own photography projects outside of work assignments, but we’re pleased he was able to shoot Richard Goodwin’s portrait for the Slow Dissolve story on page 86. His craft inspires him, as “one never stops learning as a photographer”. As for specifics, he mentions Richard Avedon and Guy Bourdin as photographers whose work have inspired him over the years.

16 habitus | Issue 03 contributors

ir S ty De GariS

editorial contributors

17

Eric SiErEnS Photographer

AlAAnA fitzpAtrick Writer

AlinA Gozin’A Photographer

pEtEr HyAtt Writer / Photographer

pAul lovElAcE Photographer

AlbErt lim Photographer

mArGiE frASEr Writer

SpAcESHift Studio Photographers

AAron pocock Photographer

HAnS ScHlupp Photographer

cHriS JonES Photographer

HEAtHEr bArton Writer

dArlEnE SmytH Writer

kirSty dE GAriS Writer

SAm noonAn Photographer

dErEk SwAlwEll Photographer

Shop 8, Q1 3011 Surfers Paradise Boulevard QLD 4217 +61 7 5592 4866 enquiry@stiledivita.com.au www.stiledivita.com.au Available Nationwide

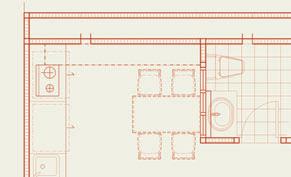

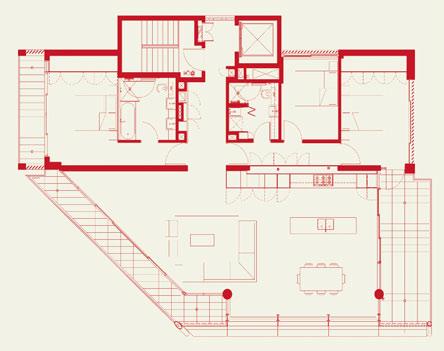

“Where the kitchen is the home, it is the home which revolves around the kitchen.”

ITALIA - design Antonio Citterio

“Where the kitchen is the home, it is the home which revolves around the kitchen.”

ITALIA - design Antonio Citterio

Lignum et Lapis – design Antonio Citterio

Editorial dirEctor Paul McGillick habitus@indesign.com.au

associatE Editor Andrea Millar andrea@indesign.com.au

assistant Editor Nicky Lobo nicky@indesign.com.au

dEsign and art dirEction Wishart Design wishartdesign.com

Art Director Karlee Bannon

contributing WritErs

Pirak Anurakyawachon, Heather Barton, Chu Lik Ren, Stephen Crafti, Kirsty De Garis, Philip Drew, Alaana Fitzpatrick, Margie Fraser, Peter Hyatt, Tempe Macgowan, Darlene Smyth, Andrea Stevens

contributing PhotograPhErs

Pirak Anurakyawachon, Patrick Bingham-Hall, Anthony Browell, Simon Devitt, James Geer, Alina Gozin’a, Peter Hyatt, Chris Jones, Albert Lim, Paul Lovelace, Rocket Mattler, Ben Millar, Sam Noonan, Esteban Perez, Aaron Pocock, Andy Rasheed, Sharrin Rees, Prue Ruscoe, Hans Schlupp, Kyal Sheehan, Eric Sierens, Dianna Snape, Darren Soh, Derek Swalwell

PublishEr / Managing dirEctor

Raj Nandan raj@indesign.com.au

oPErations ManagEr

Adele Troeger adele@indesign.com.au

businEss dEvEloPMEnt

ManagEr

Richard Burne richard@indesign.com.au

Production dEsignErs

Bronwyn Aalders, Lauren Mickan, Sarah Djemal, Camille Manley, Eunice Ku

Production coordinator

Kristy Macfie kristy@indesign.com.au

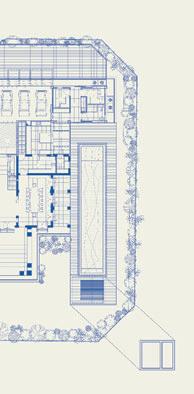

Financial dirEctor

Kavita Lala kavita@indesign.com.au

accounts

Gabrielle Regan gabrielle@indesign.com.au

Darya Churilina darya@indesign.com.au

onlinE

coMMunications ManagEr

Rish Raghu rish@indesign.com.au

onlinE coMMunications assistant Simon Layfield simon@indesign.com.au

EvEnts coordinators

Kylie Turner kylie@indesign.com.au

Angela Raven angela@indesign.com.au

advErtising EnquiriEs

Richard Burne richard@indesign.com.au

(61) 423 774 126

Marie Jakubowicz marie@indesign.com.au

(61) 431 226 077

Bernadette Bellwood bernadette@indesign.com.au

(61) 401 641 679

covEr iMagE auckland, new Zealand daniel Marshall architect

Photography: simon devitt

indEsign Publishing Level 1, 50 Marshall St Surry Hills NSW 2010

(61 2) 9368 0150

(61 2) 9368 0289 (fax) indesignlive.com

Printed in Singapore

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this publication, the publishers assume no responsibility for errors or omissions or any consequences of reliance on this publication. The opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the editor, the publisher or the publication. Contributions are submitted at the sender’s risk, and Indesign Publishing cannot accept any loss or damage. Please retain duplicates of text and images. Habitus magazine is a wholly owned Australian publication, which is designed and published in Australia. Habitus is published quarterly and is available through subscription, at major newsagencies and bookshops throughout Australia, New Zealand, South-East Asia and the United States of America. This issue of Habitus magazine may contain offers or surveys which may require you to provide information about yourself. If you provide such information to us we may use the information to provide you with products or services we have. We may also provide this information to parties who provide the products or services on our behalf (such as fulfilment organisations). We do not sell your information to third parties under any circumstances, however, these parties may retain the information we provide for future activities of their own, including direct marketing. We may retain your information and use it to inform you of other promotions and publications from time to time. If you would like to know what information Indesign Group holds about you please contact Nilesh Nandan (61 2) 9368 0150, (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax), subscriptions@indesign. com.au, indesignlive.com Habitus magazine is published under licence by Indesign Group.

ISSN 1836-0556

20 habitus | Issue 03

Hamilton, seating system design: Rodolfo Dordoni

Australia: Sydney - Dedece - Tel. 02 9360 2722

Melbourne - Dedece - Tel. 03 9650 9600

Brisbane - Dedece - Tel. 07 3367 0755

New Zealand: Auckland - ECC Lighting & Living - Tel. 09 379 9680

Minotti S.p.A. 20036 MEDA (MI) ITALIA via Indipendenza, 152 Tel. +39 0362 343499

- info@minotti.it

www.minotti.com

Discerning design: the best in furniture & lighting, technology

designer kids &

23 habitus | Issue 03 1. news

habitus | Issue 03

24 living

design news

I 01

PAULISTANO ARMCHAIR This masterpiece was designed by 2006 Pritzker Architecture Prize laureate Paulo Mendes da Rocha in 1957. The single bar of bent steel, and leather or cotton seat gives it a light aesthetic that feels just as at home in contemporary settings as in its original place in the Athletic Club of Sao Paulo, objekto.fr / hubfurniture.com.au

“Form and function SHOULD BE ONE, joined in a spiritual union”

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

FURNITURE OR OBJECT A sculptural solution to the age-old problem of what to do with excess coats and bags, this piece is both intriguing and understated and aligns with Kwon Jae Min’s belief that “furniture is a metaphor of that time”, kwonjaemin.com

SYSTEM 2D Uniting technology, handcraft and a sense of playfulness, the woven felt segments of this rug puzzle can be configured into endless designs and the material is dust- and water-repellent, mohodesign.com

25 living

I 04

TWIG Designed by the husband and wife team behind Pinch, Russell Pinch and Oona Bannon, the Twig bench and stool offer a small slice of nature in an increasingly modern world, pinchdesign.com

I 02 I 03

STELLA RUG Taking inspiration from vintage lace, this rug by designer Michelle Mason is made from 100 per cent Merino wool felt. You can choose from either black or natural cream, and they are 5.5mm and 6mm thick respectively, michellemason.co.uk

I 05 I 06

RELAX CHAIR Dutch designer Sander Bokkinga’s collection of hosepipe furniture is guaranteed to put a smile on your face, sanderbokkinga.nl

RAVEN

habitus | Issue 03 living

26

design news

CORIAN LOVES MISSONI A union of the iconic Missoni style and the versatility of DuPont’s Corian solid surfaces, Corian Loves Missoni is a project highlighting the best that each has to offer. After years of mutual respect, it is little wonder that the union has achieved such an inspirational result, dupont.com / missonihome.com

I 09

H5981 This new range from Miele offers a combination of elegant design and innovative features in a roomy 90cm width. The oven loving continues with Moisture Plus technology and more than 100 automatic programs are available, miele.com.au

I 07 I 08

HANGER With these striking pieces by Ingibjörg Hanna, you’ll want to keep your clothes on display. Available with steel wire to attach directly to your ceiling, or with a conventional hook, ihanna.net

baby + child

I 11

I 13

PLAY SHED The pre-finished panels of this childsized playhouse are just as easy to assemble as a shed, but a lot more glamorous, with a sloping roof, Dutch doors and windows, modern-shed.com

I 14

SHORTSTOP This stool/table/storage system has been a hit with the youngsters for some time now, and with good reason. They now come in an array of fabulous laminate colours, inyourroom.com.au

JAPANESE DOLL CRAYON CADDY Keep little fingers busy when on the go with this handy crayon caddy in fun fabric, which contains eight crayons and a notebook, styledbaby.com.au

27

I 10

12

TWO BIRD CAGE Hand stitched from treasures of linen, mohair, wool, cotton, vintage fabrics, tweed and antique embroidery, these bird cage mobiles are works of art, tinypeople.com.au

I

OTTO The modern silhouette of this table and chair set is not just good looking, it’s space saving as well – the chairs slide right underneath the table when it’s pack-up time. Otto is formed in patented stylewood and is available in a range of shades, bloombaby.com

YVES A classic design for a classic piece of furniture

the writing desk. Yves, designed by Russell Pinch, is built in solid walnut with a leather top and two drawers, pinchdesign.com

I

MANTEL DOME The first product in a collaboration between Innermost and designedbyitem, this design thrusts an industrial aesthetic upon the traditonal carriage clock, innermost.co.uk / optique.com.au

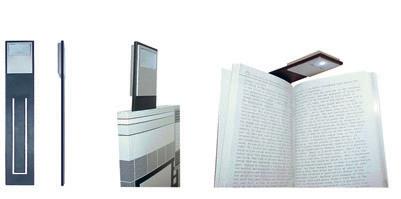

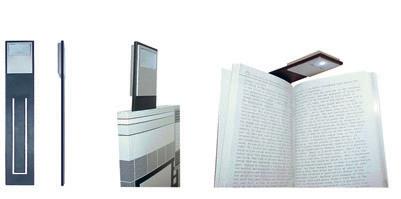

FLAT Anything but flat, this flexible bookmark, designed by Gabriele Pezzini, has a handy built-in reading light that marks the spot, areaplus.com.hk / muji.it / habitat.co.uk

I

ANYTHING SCISSORS The Samurai sword was the inspiration for these scissors, which are part of a collection that creates visual cohesion for stationery items, michaelsodeau.com / anything-design.com

I 17 10KEY CALCULATOR Designed by Ippei Matsumoto, this simple and colourful calculator can be connected to your computer with a USB cable – a particularly helpful addition to the laptop, idea-in.com

habitus | Issue 03

28 work I 15

18

design news

I

19

–

16

www.rado.com RADO TRUE CHRONOGRAPH JUBILÉ

ONEHUNDRED&TEN To commemorate British luggage brand Globe-Trotter’s 110th anniversary, Ross Lovegrove has designed this case from lightweight, durable carbon fibre and Kevlar, globe-trotterltd.com

KIRIKABU The green bug has bitten JVC, who have created these personal speakers that double as plant holders. In the form of tree stumps, the Kirikabus can be connected for a rich audio experience, jvc.com

LEAF SWING The delicate veins of leaf are traced and make up the playful yet sophisticated seat of this grown-up swing. Revert to your childhood for just a few moments as you rock back and forth in your surrounds, enea-studio.com

BABUSHKA LIGHT Capturing the familiar nesting shapes of Russian Babushka dolls, these ornamental lights are made from blown glass and Perspex, and are highlighted by coloured LEDs, mathmos.com

B20 With a simple aesthetic, this bicycle from Fritsch Partners is extra-clean for the environment, by virtue of its function and through its material – it’s made completely of bamboo fibre, fritsch-associes.com

habitus | Issue 03

30 play

design news

I 20

22

23

24

21

I

I

I

I

LUSH SPOT A STRIKINGLY BEAUTIFUL VELVET COLLECTION. wovenimage.com

Photo: Paul Gosney / Stylist: Kathy McKinnon / Corporate Culture Furniture

Vissy Frag Woodall Woodmark woodmark.com.au

RRP $11,000

The elegant form and squeaky-clean highgloss finish of the Vissy – highlighted by the fruit bowl morphing into the surface of the credenza – is juxtaposed with the exuberant textured fabric on the doors. The credenza is also available with timber sliding doors stamped with a dandelion-inspired motif.

Tierra George Harper Tide Design tidedesign.com.au

RRP $4100

The handmade Tierra (Spanish for ‘earth’) in American cherry or American oak, boasts careful attention to detail and a unique leg structure, as well as surprising door-todrawer proportions. Tierra can be custom made to suit individual requirements.

Alba Russell Pinch Pinch pinchdesign.com

RRP £3995

Lewis Sideboard Design Refinery Tongue and Groove tongueandgroove.com.au

RRP from $3575

BoReD WITH SIDeBoARDS?

This low sideboard in sustainable Hoop Pine plywood celebrates the traditionally elegant angles of Scandinavian design, with the modern twist of a screenprinted illustration by Tim Fleming. Just the right height for a flat-screen television, Lewis also doubles as an entertainment unit.

Radii

Jason Bird Interstudio interstudio.com.au

RRP from $3500

This intriguing piece in 100% FSc timber draws inspiration from mid-century relief plasterwork for its façade. The sculptural doors conceal two centre drawers and two cupboards, each with an adjustable shelf. Alba is available in a range of colours.

Designed and manufactured in Australia, this sideboard is both classic and contemporary, with an oak veneer carcass that can be colour stained and two-pack polyurethane lacquer to the cupboard facings.

32 habitus | Issue 03 re-shoot

We’ve got some inspiration for you

HIDDEN BEAUTY

The Fifty Table is beautiful both outside and in. Hidden beneath the surface lies a very clever extension mechanism, allowing you to extend from six to ten or up to twelve people in an instant! Perfectly suited to home and office, Fifty is available with a light-weight timber surface, or in polished or matt glass in numerous colours. Made in Italy using only the finest materials and manufacturing techniques, Fifty proves that beauty is not only skin deep.

Milk Furniture 1 St Kilda Road St Kilda 3182 tel 03 8598 9900. Open 7 days. www.milkfurniture.com KMD 0620 HAB

technology with style

With twin fully-fl edged 60cm Thermoseal ovens, the Smeg CSA122X gastop freestander will

help make you twice the cook. www.smegappliances.com.au

TWICE THE EXPERIENCE.

Rory Johnston doesn’t take holidays. Instead, he attends classic car events across the world. It’s lucky, then, that his wife is as car-obsessed as he is (“that’s how we met”), and it’s also lucky that Johnston loves what he does. Such are the benefits of following his passion unfettered by pressure to do anything else. “It absolutely becomes about the people,” Johnston explains, “it’s a way of life and I love it.”

He grew up around classic cars, learning to drive aged 11 in a split-window Volkswagen Kombi. “I suppose you could call that my first classic car. I was always fixing up cars with my dad, so it’s something that I’ve been involved with all my life.”

It is no surprise, then, that Johnston chose to work with classic cars himself. Since emigrating to Australia from the UK with wife Karin in 2002, he has built a booming business around Australians’ increasing enthusiasm for one-of-akind, top-of-the-line automobiles.

Classic renaissance

The mascot of the business, Classic Throttle Shop – based beneath the austere arches of the Sydney Harbour Bridge run-off that forms the start of the Pacific Highway – is a pale blue Messerschmitt KR200. This charming cabin scooter was owned by Johnston’s father 40 years ago and Johnston brought it to Australia when he and his wife moved to Sydney.

They arrived in Australia with nine collectible cars and a sketch of an idea to somehow work with the vehicles they loved. Shortly after arriving, they set up shop in a studio space a few doors from where the business is now based and began to trade. From those beginnings, Classic Throttle Shop flourished.

For Rory, his whole business is indulging a design passion. Various factors contribute to a car’s sale value and at this end of the market, entry level is high. Badge, provenance, availability, number built, condition and previous owners all contribute to a car’s contemporary retail value. “I do a lot of research before I buy a car,” he explains. “There are fakes out there.” Johnston

habitus | Issue 03 35 conversation designer drive

I For the hunters and collectors of design classics, it’s irrelevant whether the object of desire is a chair, a bottle opener, a watch or a car. What matters is its ability to inspire emotion. Rory Johnston has created a successful, full-time career out of his passion for classic design automotives, and while new car sales seem to be dwindling, Rory’s Classic Throttle Shop in Sydney is a hub of activity.

Text Kirsty De Garis

Photography Alina Gozin’a

I 01 Rory Johnston in one of his beloved vintage cars. I 02

I 01 I 02

This Messerschmitt KR200 is the mascot of the business.

has one Ferrari in his showroom valued well over a million dollars; it is the only example of the car built in aluminium rather than stainless steel, so that it could be driven as a lightweight racing vehicle, and was custom-made for an Italian race car driver.

Johnston considers the golden era of automobile design to be the 1960s and 1970s, when the design of top-notch cars at that time was in the hands of a chosen few elite designers who forged their careers with the big car manufacturers of the era. Italian design studio Bertone’s designer, Marcello Gandini, was just 27 when he drew the outlines of Johnston’s current obsession, the Lamborghini Miura, in 1966. “I’m a big fan of Bertone,” Johnston muses. “I think their design in the 1970s was fantastic.”

Johnston even sold his home to buy the Miura, believing the car’s value increase would far outweigh the financial benefits of home ownership. His eyes glaze over as we look at it. “It was designed so that, on its side, it had the curves of a woman’s body,” explains Johnston. With only 760 ever made during the early 1970s,

this rare right-hand drive model, painted a racy red (paint jobs can set you back in the hundreds of thousands) sports a V12 engine and has a resale value of somewhere around $1.5 million. It reaches a speed pushing 300 km/hour, however driving blogs insist it isn’t an easy car to drive.

On the showroom floor at the time of publication was a 1971 Lamborghini Espada Series 2. Looking, at first glance, like something out of Austin Powers, the car benefits from some of the Miura’s spectacular detailing and tops the speedometer at more than 200 km/hour. “Love it or hate it, you just have to look at it,” he laughs.

Classic Throttle Shop’s clientele is a select community. Last year, Johnston and Karin traveled to Goodwood Revival – the UK’s premier

classic car racing meet – with one of their cars. “Once you’re invited – and you’re only invited if you own one of these cars,” he says, “you are admitted into a fantastic social scene.”

The showroom and its staff also star in a new television program, airing in early 2009 on Australia’s Network Ten. “It’s about the cars and the racing, with a bit of lifestyle,” Johnston explains. It seems from the outside that Rory Johnston can’t quite believe his luck, as he strolls leisurely around the showroom, caressing the body of a priceless Lamborghini. “These cars are really pieces of art,” he sighs. “I could never treat them like a modern bit of metal.”

Classic Throttle Shop, classicthrottleshop.com

habitus | Issue 03 36

drive conversation I

A

I

A

designer

03

print of Stirling Moss in a Ferrari 250 GT SWB graces one wall of the showroom.

04

range of Le Mans gear is displayed in homage to the Steve McQueen film.

I 04

03

I Badge, provenance, availability, number built, conditions and previous owners all contribute to a car’s retail value.

I

Tibetan Carpets ...imagine the possibilities www.rc-d.com.au MELBOURNE (HEAD OFFICE) 573 CHURCH STREET, RICHMOND T: 03 9428 6223 SYDNEY 112-116 PARRAMATTA ROAD STANMORE T: 02 9519 8555 BRISBANE 5 LIGHT STREET FORTITUDE VALLEY T: 07 3852 6300 PERTH T: 04 2221 2400

For distributor listing & complete product range please visit www.parisi.com.au or call 02 9559 3666 2008 Series

the best

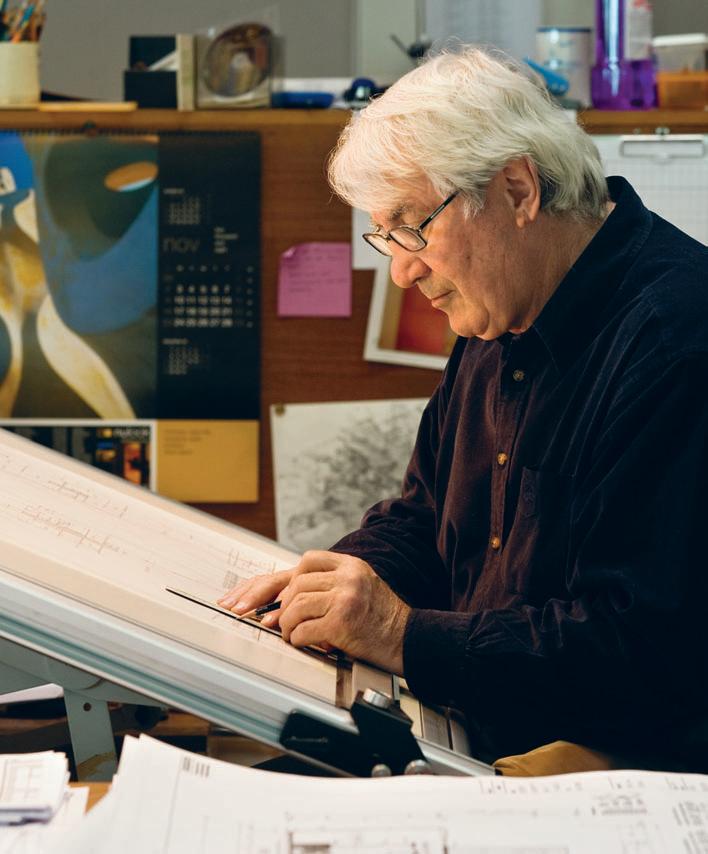

architects EVEN TODAY still draw by hand. PHILIP D REW discusses three books which EXPLORE drawing and architecture

habitus | Issue 03 montage 39

the lamp of drawing:

michelangelo to murcutt

“I say he ‘thinks’ this, and ‘introduces’ that. But strictly speaking, he does not think at all. If he thought, he would instantly go wrong; it is only the clumsy and uninventive artist who thinks. All these changes come into his head involuntarily; an entirely imperative dream, crying, ‘Thus it must be,’ has taken possession of him…”

John Ruskin commenting on Turner, ‘Of Turnerian Topography’, 1856 Drawing involves more than simply seeing what is there. It is a magical act, the beginning of speech in making the world real. It played a crucial role in primitive religion, as in the early Paleolithic cave art of Altamira and Font-de-Gaume. To draw an animal was to make it real and tame it. Sight was more important to John Ruskin than drawing. He thought its value lay in learning to love nature rather than looking at nature as a subject. Drawing does teach us to see better, to notice and analyse, possibly to understand how things are constructed and, thereby, to understand a little better their design.

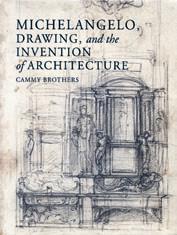

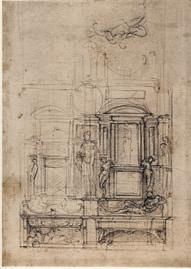

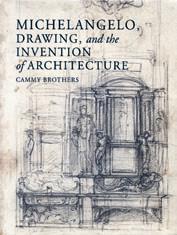

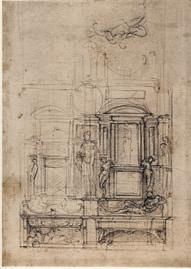

Two new books – one on Michelangelo’s drawings, and another on the architectural drawings of Glenn Murcutt – challenge the dominant worship of digital imaging in architecture. This is most welcome: we place too much emphasis on the visual fakery flowing from the computer, which can prove so misleading. Computers lie because they are just machines – perverted into selling architectural dreams.

The over-reliance on the computer substitutes for genuine creativity and encourages the production of meaningless forms. It generates images that, while they are noticeably excellent in depicting alien life forms and alien worlds, they are distant and cold. Drawing, like handwriting, has a real intimacy, a directness that instantaneously connects us to the mind of the drawer. They are very personal – unique to that individual.

Both books accept the premise that drawings are design and Cammy Brothers points out that the Italian word for drawing, disegno, also included design in its meaning. Drawing was inseparable from and integral to the design continuum – part exploration, part discovery.

I

01, 02, 03, 05 Michelangelo, Drawing, an D the i nvention of a rchitecture

Cammy Brothers

Published and distributed by by Yale University Press 272pp hardcover US$65 yalepress.yale.edu

04, 06 glenn Murcutt: t he a rchitecture of glenn Murcutt

glenn Murcutt: t hinking

Drawing/ working Drawing

Published by Toto Shuppan

Distributed by Idea Books

328pp hardcover AUD$140 & 248pp hardcover AUD$106 ideabooks.nl

07 t he JuDicious e ye

Joseph Rykwert

Published by Reaktion Books

Distributed by Footprint Books 432pp hardcover AUD$92 footprint.com.au

Previous books have concentrated on the relationship between the architecture and Michelangelo’s drawings. Brothers adopts a different perspective by examining how the artist used drawing as a medium of thought and design, using procedures he developed for painting and sculpture, then applied with great success to architecture. In this way the reader can see the same procedures at work, but to different ends.

Michelangelo used drawing to discover his own language of architecture. It was a gradual process, built upon his earlier drawing practices of tracing, overlaying and sketching models in series. His great obsession, indeed his sole subject as an artist, was with the human figure. He believed, “…it is a certain thing, that the members of architecture derive from the members of man. Who has not been or is not a good master of the human body, and most of all of anatomy, cannot understand anything of it.”

Michelangelo extended what he learned about the human figure and its gestures to architecture. With this he animated the classical scaffolding the Quattrocento had studiously re-invented by measuring and drawing the ancient monuments of Rome, often from scattered incomplete fragments. But Michelangelo was less interested in archaeological authenticity, than in using Ancient Rome as a starting point.

He was not content to copy the ancients, following their rules of proportion, imitating moulding profiles, applying Vitruvius. He meant to outdo them. This sits at the core of his Mannerism – the need to go beyond the ancients in a free interpretation and inversion of classicism. Along the way, he created his own anti-Classical language that overturned and inverted classical convention. For

habitus | Issue 03 40

montage philip drew

01

02

I

nearly two centuries, until the advent of Neo-Classicism, Michelangelo’s capricious undermining of Renaissance practice was widely influential. He harnessed the classical to his own expressive ends. Though the drawings are exquisite and seductive in themselves, they are arbitrary distortions of the classical.

In the Laurentian Library he imprisoned paired pilasters within the wall. Brackets that were supposed to support them were too fragile for the loads they carry, and a gap separates the two. The stair explodes into the vestibule. It is much too large and presses itself against the confining walls. The result is psychologically oppressive. His architecture, like his sculpture, strains against its corporeal bonds. The body, Michelangelo seems to say, is a prison for the immortal soul.

He glories in his war with flesh. Yet it imprisons him, leaving him a restless, tortured and unquiet soul.

Not only did Michelangelo not measure and draw the Roman monuments – he saw no point in doing so, just as he thought perspective, the very foundation of Renaissance pictorial space, was a waste of time – he displayed no interest in ancient monuments except to re-draw the reconstructions of other antiquarians. He plays with and teases such profiles, adds a mouth, a nose, human features, that humanise otherwise abstract geometrical exercises in light and shadow, that express load and support and the flow of gravity to the ground through a frame of classical architectural lineaments glued to the wall.

His overthrow of classicism initiated Baroque and Mannerism, leaving a difficult legacy behind for lesser talents.

A contemporary Spaniard, Santiago Calatrava, also starts with the human figure. Its gestures inspire his structures, as if they are human figures that resist loads. So we place ourselves within his creations, feel and resist the loads in place of his constructions. Calatrava is an heir of Michelangelo with a similar emphasis on architecture as sculpture. Glenn Murcutt’s subject is Australian nature. Unlike Michelangelo, the human figure is only of passing interest.

The two Murcutt volumes were published simultaneously with the Thinking Drawing/Working Drawing exhibition at the Gallery Ma in Tokyo (June 12-August 9, 2008). There are supporting essays by Catherine Lassen, Tom Heneghan, Shoko Seyama and Maryam Gusheh. Shoko Seyama is by far the most perceptive. She does not

shrink from asserting: “Murcutt’s architecture is an Australian architecture, born of the uniqueness of his country. And, it is his manner of response to this uniqueness that gives Murcutt’s architecture its irresistable beauty”.

and including, sketches simultaneously exploring aesthetic and construction assembly issues, joints, culminating with working drawings and large details. Taken together, they offer a fascinating opportunity to explore Murcutt’s architectural process. This is a welcome change from the customary glamour coffee table genre beloved by architects, and instantly registers his emphasis on construction. Unlike an earlier Haig Beck monograph, which included digital scans, the drawings with their notes can be easily read. You have to chip away at a problem – Michelangelo and Murcutt’s drawings do so patiently. Sometimes the discoveries seem inevitable, at other times a surprise. The essays miss Murcutt’s deeper preoccupations; he emerges instead as a dexterous technician when it is really the poetry that sets the agenda – “the dream that has taken possession of him”, which says “thus it must be.” If the technician was all there is to Murcutt he would be far less interesting an architect and far less important. It is a mistake to read his drawings too literally and not to inquire into what they work towards. What is his goal, or, as Ruskin asked: what is the imperative dream that cries out to Murcutt?

41 I 03 I 04 I 05

The second drawings volume surveys 13 projects from the 1972 Douglas Murcutt House to the 2005 Walsh House. These are copiously illustrated by early conceptual sketches through to,

Michelangelo inverted Classicism. Murcutt turns modernist orthodoxies and conventions to secure an Australian expression that responds to the country, instead of twisting northern hemisphere approaches, following the example of Sydney Ancher who did so much to encourage him in this enterprise. The Renaissance invented perspective. It was so much more than a drawing technique, inasmuch as it unified the visual field and rendered it coherent. The world is tied to a single vanishing point. It was a closed world that Renaissance artists constructed, space was contained and limited, just as explorers were breaking out of European geography and discovering a new world beyond it. Ships did not fall off the edge as was supposed.

Murcutt’s architecture expresses a different spatial sense, one that is mono-axial and emphasises the dimension of distance. His is a world of limitless horizons, single axes driving into nothingness, even though the majority of his buildings are on the coastal edge away from the outback within a comfortable three-hour drive of Sydney. His railway carriage houses recall endless steel tracks running on and on to the horizon. This makes his space special. The poetry derives from this expanding frontier utilising a hybridisation of our 19th Century colonial industrial foundations, in combination with modernism.

He remains anchored to this model. The Lidco aluminium windows don’t seal properly, they are 1970s technology that has been superseded; his corrugated iron is a 19th Century invention that also has been superseded.

This has largely gone unnoticed. Murcutt’s engineer and collaborator, James Taylor, says: “Glenn makes his buildings as light as possible, partly out of a concern to minimise the use of natural resources”. In fact, the amount of steel used is excessive: something like 38 tonnes in one 250m 2 house, or 26 psf (152.7kg/m 2), compared to 42.2 psf (206 kg/m 2) for the 102-storey Empire State Building with its 1930s riveted-steel frame, and 33 psf (161 kg/m 2) for the 110-storey Sears Tower. Look for inconsistencies – they lead directly to real discoveries, if you wish to truly understand the architecture.

The value of the two Murcutt volumes is less what they say than what they illustrate. That is why Murcutt’s drawings are so valuable and repay close study and analysis. They manifest an intense concentrated focus on specific problems. Too many architects seem afraid to work out their own solutions and are content to copy from others instead of thinking for themselves.

That way leads to Zaha Hadid and the erosion of function in meaningless forms. This is in part the subject of Joseph Rykwert’s most recent book which takes for its subject the breach between architecture and the arts of painting and sculpture from 1760 to the 1930s. It is a dense work of scholarship that could have benefited from judicious editing. He frequently strays off subject, but there are rewards – though often, irritatingly, it seems that Rykwert has lost contact with his chosen theme and is writing a history of architecture with asides on art. It is not without its errors: the Nazis are credited with closing down the Bauhaus when what happened was Joseph Goebbels approved its continuance only to see it closed by Mies van der Rohe.

Not only does the narrative lack continuity, the book produces no conclusions. If we are to conclude anything, it is that any synthetic work of architecture, painting and sculpture, even when this is the given goal, is an achievement against all odds. Rykwerk does find one example worthy of celebration. This is Josep Lluis Sert’s Spanish Pavilion for the Paris International World’s Fair of 1937, about which he writes: “…what seems powerful now, 70 years after the event, is that a political conjunction prompted the incandescent fusion of building, painting and sculpture”.

Sydney’s well-intentioned attempt at a similar political fusion in the Federation Pavilion of 1988 resulted in a saccharine imitation of a Roman temple and a plagiarised Aboriginal art work by Imants Tillers. If anything, it demonstrated just how impossible such Gesamtkunstwerke are. Hermann Finsterlin’s architecture game in Frühlicht 3, played out the generation of architectural styles from orthogonality to organic form now seems especially prophetic in view of the current Hadid craze.

Drawing, because it is a tool common to painting and sculpture, offers a means for architecture to move closer to the other visual arts of painting and sculpture. In Michelangelo’s time an artist could be an architect, painter and sculptor, so it was not an accident that buildings and the arts were total works. We have largely lost this capacity. Drawing is a natural spontaneous activity that, like handwriting, we are in danger of losing under the onslaught of the computer and digital technology. It is perhaps time to think again about, and to re-value, what drawing can contribute in the increasingly rarefied artificial culture we are creating. That which flows directly from the mind to the hand can unite us with others and assist us in shaping the public sphere when it expresses our imperative dreams. Drawing makes us human and individual.

habitus | Issue 03 42 philip drew

montage

I 06 I 07

FORWARD THINKING IDEAS, PLACES OF INTEREST, CREATIVE SOULS & VALUABLE

INSIGHTS

45 2. people & places habitus | Issue 03

German design and engineering has made Neff a market leading brand in Europe.

The latest sales figures from Europe by industry research specialist GfK show that Neff is No. 1 in Great Britain, No. 2 in Germany and No. 4 in Central Europe. *

And is it any wonder given Neff has been writing kitchen history with their cooking appliances for over 130 years. Today Neff is still 100% German designed with extensive production facilities and headquarters in Bretten.

Perhaps another surprise - Neff is more technically advanced and offers superior features to many other leading brands. Like the precise temperature control of the CircoTherm cooking system, the unique rotating Revolution handle, the Point & Twist cooktop control and the reassurance of a 4 year warranty on all Neff appliances.

To uncover the benefits of Neff for yourself arrange an appliance demonstration at one of our showrooms, or locate your nearest retailer by calling 1300 727 421 or visit www.neff.com.au.

Proudly imported, distributed and supported by Sampford IXL.

Europe’s kitchen specialist

*The GfK Group is one of the largest market research companies in the world. Figures refer to the period from January to August 2008 based on sales value. Central Europe is Austria, Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, UK, Greece, Italy, Netherlands and Sweden.

lens Through the

John Gollings is widely regarded as the master of architectural photography in Australia. His images typically convey the inspiration behind buildings. But what inspires John Gollings? Stephen Crafti finds out.

47 habitus | Issue 03 inspired

Photography John Gollings

Text Stephen

Portrait Photography Tom Hutton

Crafti

I 01

john gollings — VIC, australia

photographed Denton Corker Marshall’s first building, a pilot station at Queenscliff.”

DCM’s concrete bastion, a radio communication centre designed to guide ships into port, was photographed with seagulls circling the building. “I wanted to show the bastion against the elements – against the roughness of the heads,” Gollings adds.

Architect Peter Corrigan had also just completed two churches, both of which were to feature in Domus magazine. “Peter was considered one of Australia’s greatest proponents of post-Modernism,” says Gollings, who understood Corrigan’s theatrical approach to architecture. “I photographed both churches at night. I wanted to accentuate the polychrome brickwork as much as the forms,” he says. In one photo, a tree creates a shadowy effect over a spire. In another the priest stands in front, with his parish almost painted with light.

John Gollings has had a camera in his hands since he was 12. “My first photos were of my sister and brother jumping off a mountain of potting mix,” says Gollings. Another photo captured his sister balanced precariously on top of the ‘mountain’. “My brother was supporting her on his shoulders. But he’s concealed from view,” says Gollings, who has always been fascinated by surrealist images.

The mountain of potting mix was one of many in the garden nursery surrounding the Gollings’ family home in Carnegie, Melbourne. While ‘Gollings the Florist’ nursery provided a fertile environment for an inquisitive teenager, it was his father’s ‘Ensign’ folding camera that took hold of his imagination. “Ray Oliver (a keen amateur photographer and employee of the nursery) taught me how to develop and make contact prints, “ says Gollings. “I knew I’d always come back to photography.”

Gollings’ father sold the nursery and went into the building industry. “I have to confess my father was responsible for many of the walkup 1960s apartments around Prahran and South Yarra,” says Gollings. With the intention of joining his father in the construction business, Gollings enrolled in architecture at Melbourne University in 1964. His contemporaries at university included the directors of Denton Corker Marshall, as well as architect Peter Corrigan of Edmond and Corrigan. But unlike his esteemed classmates, Gollings wasn’t in the graduating class. “I was already married with two children and I needed work. But in the four years I was there I spent more time as a stage manager in the Union Theatre than in architecture classes.”

In photography, as in life, timing is everything. Gollings’ friend, the late photographer Rennie Ellis, introduced Gollings to the advertising agency, Orpin & Bourne. “They were probably the edgiest agency at the time, completely in step with swinging London of the late 60s,” says Gollings, who stayed with the agency for three years.

While not formally trained, Gollings’ inquisitive mind was appreciated. “Before I photograph anything I like to read up on the subject, garnishing as much detail as possible. I learnt everything I could about colour theory as well as optics and lenses.”

One of Gollings’ first assignments was photographing a disco in Melbourne’s Flinders Lane. “The brief was to capture the energy in the club,” says Gollings, who used a 35mm camera with high speed film. “From memory, my black and white photos taken that night were quite grainy, with people completely intermeshed,” he says. By the mid-70s, Gollings’ architectural friends were completing their first buildings. “Peter Corrigan and Kevin Borland wanted their buildings photographed. I also

One of Gollings’ first large assignments was via the Australia Council. Three photographers (the others were David Moore and Max Dupain) were selected to photograph some of Australia’s most significant buildings. “We all approach architecture quite differently. Max had a slightly romantic perspective and David worked with a small camera, creating a documentary style,” says Gollings. “I worked with colour and captured wide elevations. I always show the context of a building, where it sits in a landscape, be it urban or rural.”

Since the early 1980s, Gollings’ name has become synonymous with architecture because he has photographed most of Australia’s landmark buildings.

Whether it is an individual building or an entire region (Gollings has just completed a book on mud brick homes in Xianjiang in China), composition is the foundation of each image. “I’ve often said my approach is quite dumbly simple. My horizon lines are always in the centre of a photo. And I never tilt my camera, even if it is considered artistic. I think it’s important to offer a critique of the building as well as allowing the viewer to come to their own conclusions,” says Gollings, who tries to expose a building for what it is, rather than covering it up with photographic tricks.

Form is also a crucial feature in Gollings’ photographs. Whether he is behind a lens, or looking out of a hotel window, the form of a building resonates. He was recently standing at his hotel window in Sydney, looking out towards the Art Gallery of New South Wales. While he found the 19 th Century building inspiring, an addition made to the gallery in the 1980s disturbed him. “[The extension] may be a suitable interior, but it failed to communicate its ideas on the outside,” he says. “Look at the Richard Johnson extension – It’s far more discrete, but more engaging.”

habitus | Issue 03 48

inspired

I 02

One of Gollings’ first assignments was photographing a disco on Flinders Lane.

I 01 Previous John Gollings

At work, photographed by his assistant, Tom Hutton.

I 02 Kashgar, China by John Gollings.

I 03

A Giardino painting

Commissioned by John Gollings, it features Gollings’wife, Marion, and also his son, Sam.

I 04

Artist Pasquale Giardino

Who migrated to Melbourne from Spain with his family.

I 05

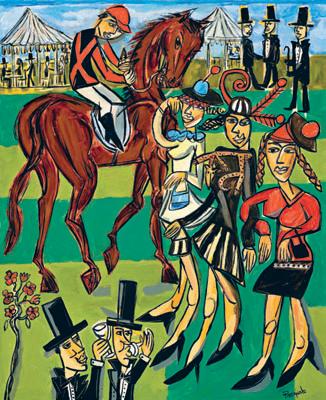

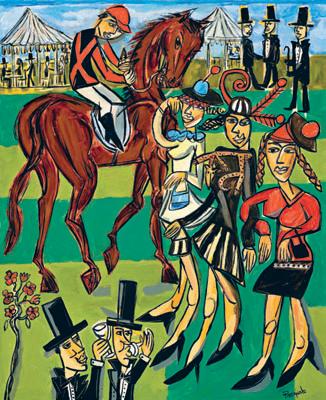

Fashions on the Field From A Day at the Races series by Pasquale Giardino.

49 I 04

I 05 I 03

I

John Gollings’ photographic studio in St.Kilda was designed by Denton Corker Marshall. A graphic staircase leads to a gallery-like environment. The studio features several sculptures by various artists, including Lauren Berkowitz, Louise Lavarack, Robert Owen and Tony Pryor. In his collection are several paintings by artist Pasquale Giardino, a Spanish painter. “Pasquale’s family migrated to Melbourne several years ago,” says Gollings. “The entire family understands the pleasure that comes from domesticity. The family bottles their own home grown tomatoes.”

Gollings started purchasing Giardino’s paintings from the early 1980s when the artist was part of Raw Studios (which also included artist David Larwill). “Pasquale isn’t part of the art scene. You could say that he’s not popular taste. And he doesn’t compromise,” says Gollings, who appreciates the artist’s ‘ joie de vivre’. “His paintings bring a European understanding of the simple pleasures of life,” he adds.

Gollings feels that he often intellectualises too much over what he sees behind his lens. In contrast, Giardino’s paintings show a more spontaneous side to life, imbuing each of his canvases with emotion. One of Giardino’s larger paintings is displayed in Gollings’ living

I 06

Virupaksha Temple, Hampi, India

By John Gollings.

By John Gollings.

room. Commissioned by Gollings, the painting features several figures enjoying a festive occasion. Gollings’ son Sam is depicted patting his dog, and his wife Marion is also part of the celebrations. The image of a horse and cart appears in one corner of the painting. “They relate to an earlier painting I commissioned,” says Gollings.

“I remember being hit with a ruler by the art teacher when I was in grade two. Like Pasquale, I outlined my figures in heavy black lines. I was told it was stupid and just to use flesh colours,” says Gollings, who appreciates Pasquale’s heavily defined eyes and lips.

Giardino’s paintings are a sharp contrast to Gollings’ photos, which are highly composed, with the context of each building clearly articulated. Giardino’s paintings are far from ordered – if anything, there’s a sense of chaos. “With Pasquale’s paintings, you get to understand how other people see the world. There are certain things that may escape me when I’m behind the lens. But I’m reminded of some of the simple pleasures in life when I stand back and look at these paintings.” Gollings Photography, gollings.com.au

50 habitus | Issue 03 inspired

06

“ I always show the context of a building, where it sits in a landscape, be it urban or rural.” JOHN

STYHAB0309 available exclusively from stylecraft moon chair design pietro arosio Sydney 1300 306 960 Melbourne Brisbane Canberra Adelaide Darwin Perth Singapore +65 6511 9328

jac hunt — NSW, australia

Treasure BOX

For a designer known for her timeless, understated creations woven from quality yarns – a truly noughties approach to knitting – it comes as something of a shock that Jac + Jack designer Jac Hunt lives in what can only be described as creative chaos. However you would only draw this conclusion from the surface.

Jac does a lot of designing for the nearly five-year-old label from her home in Sydney’s Centennial Park. She looks out the windows onto the vivid pops of Australian outdoor colour. Much of the colour inside her home comes from Jac’s extensive shawl collection, which she’s been collecting for 20 years and displays in wire baskets. “I look at all these beautiful textiles together and it reminds me of the places I have been to collect them,” she says.

The Jac + Jack brand was born as a conversation between Jac and then-colleague at Marcs,

Lisa (‘Jack’) Dempsey. “I was womenswear buyer at Marcs and we worked together there, then at Jigsaw, and again at Marcs when I went back as brand manager,” Lisa explains. While working together, Jac recalls, “We would constantly talk about our label, how it would look, different ideas.” The ideas distilled until they met with the third member of their business team, honed the idea, and went into business. Their first collection was a 29-piece ensemble, several items of which are still in the collection today, which says a lot about the effortless, enduring tone Jac has set with her creations – both in form and style.

In 2004, when Jac + Jack was born, the concept of an Australian fashion label devoted entirely to knitwear was a new one. Lisa says, “We always felt knitwear in this country was lacking in simplicity.”

“Simplicity in the true sense of the word,” Jac elaborates. “Quality yarns, well designed and beautifully knitted.”

Homegrown support for the young label has been fantastic, with David Jones a major stockist. Independent boutiques including Belinda, Blood Orange, davidmetnicole, and Lee Mathews have also taken up Jac + Jack, which Lisa reports many customers still perceive to be an imported knitwear label.

For Jac, inspiration begins with the raw materials. “I’m not one of those designers who says, ‘I’m going to do Santa Fe now,’” she explains. Instead, she does her groundwork, visiting yarn fairs (the world’s best are in Shanghai and Florence). At the fairs, Jac will select yarns: “I’ll take a kilo of something I like,” she explains, and from there will experiment with swatches. It’s important, she says, to see how something knits.

habitus | Issue 03 52 Photography

Text Kirsty de Garis

Prue Ruscoe

at

home

I The Sydney-based fashion label Jac + Jack is quietly gaining cult status for its purist yarns and simple forms. At home, designer Jac Hunt – one half of the Jac + Jack duo – prefers a bowerbird approach to collecting pieces to live with.

I 02

This can be a prolonged process of trial and error, as was the case with recently developed ‘second skin’ cashmere. “It took a long time,” she says. “There are so many elements to consider. But we are thrilled with the result, and it is always worth it to work so hard to get it right.” Jac and Lisa are also passionate about using australian superfine merino wool in their designs. “It’s such an under-utilised raw material,” she says.

Jac is also very hands-on with the creative team that makes her designs a reality. “I spend a lot of time at our factories,” she explains, adding that she has recently made contact with a 30strong team of women hand-knitters in India, with whom Jac + Jack are set to work moving forward. “I was so excited to meet with these women and see what they do,” she says.

I 01 Previous Design duo Jac + Jack at the dining tableturned-workspace.

I 02

Jac Hunt has taken an eclectic approach to her apartment.

I 03 Opposite Her collection of coloured glass has been amassed over the years and is regularly rearranged.

Jac’s approach to the decoration of her home interior is a lively, colourful complement to the warm minimalism of her knitwear. “I like the idea that your life evolves,” she says, “your style evolves. That’s why I like pieces with a bit of history.” So while you will find a classic Noguchi coffee table in her home, it is not filled with modern classics. “In context with other things, it looks really fantastic,” Jac explains, “but not en masse. That doesn’t speak to me of a personal touch. I like to put things together my way.”

and that’s exactly what Jac does: a decades-old collection of glass is displayed on one surface, and Jac confesses to frequently rotating the vases on display. The stack of brightly coloured hats is an expression of the world in which she works as much as it is a decorative feature. “For me there’s no philosophy. It’s intuitive,” she says. “I’m not into anything that’s too contrived. Really I respond to whatever I think looks good.” This usually means items with texture; what Jac would describe as pieces with a history and soul. “I’m not into things that are too shiny and clean. I like the idea of pieces adding layers to a home,” she says.

Back to the subject of work, Jac says thatwhen it comes to turning to other designers for inspiration, the name that comes immediately is Dries Van Noten. “His are such classic designs, with a wonderful choice of colour,” Jac says.

“We don’t take the easy route of choosing off a colour palette,” Lisa adds. “at the end of the day it’s about function: it has to be wearable, feel great, and have a timelessness about it so it’s not in one season, out the next.”

habitus | Issue 03 54

“I look at all these beautIful textiles together and it remInds me of the places I have been to collect them.”

–Jac

at home

“And you’ll find that our greys are never just grey,” says Jac. “We do grey marle, charcoal, slate grey, donkey grey. And we never just do a brown – it is every shade of that.”

This commitment to taking the difficult path to great design is one element that has set the work of Jac + Jack far apart from other contemporary Australian fashion designers. The rich variety of colour is indicative of their meticulous approach to their business. As a result of this attention to detail, business is going brilliantly for the pair. And, despite past protests, Jac may even see herself moving from her cosy apartment overlooking the trees to somewhere with a bit more space for the homewares range – in timeless shades and silken cashmere, of course – that is next on the agenda for Jac + Jack.

I 06

habitus | Issue 03 56

at home

I 04 I 05

Jac + Jack, jacandjack.com

I 04 Olive Dress in Coffee from Jac + Jack Winter 09 collection.

I 05 Baskets of coloured shawls brighten up corners of Jac’s apartment.

I 06

Kyd Shawl in Wedgewood, Sadie Tank in Wedgewood and Jonnie Pant in Grey, all from Jac + Jack Winter 09 collection.

“I’m not into things that are too shIny and clean. I like the idea of pIeces addIng layers to a home.”

–JAC

FEEL THE DIFFERENCE. LONGBARN COMPANY SYDNEY 95 BRIDGE ROAD GLEBE NSW 2037 T 02 9692 8822 MELBOURNE 1 B CHATSWORTH ROAD PRAHRAN EAST VIC 3181 T 03 9510 0501 W WHITECLIFFE.COM.AU E SALES@WHITECLIFFE.COM.AU

Aptos Cruz — SA, australia

Cultural Cross-Over

I They had worked all over the world, but came to rest in a pretty village called Stirling in the Adelaide Hills. Twenty-one years later, Steve and Pat Ronayne still complement one another running their gallery/showroom/bookstore, Aptos Cruz. Now, reports Paul McGillick, it boasts a new gallery extension by architect Con Bastiras.

I visited Aptos Cruz with Con Bastiras on a crisp and sunny day last August. It’s a magic name in a magic location and winter is probably the ideal time to make the short drive up from Adelaide into the Hills. The light has an alchemic effect on the trees and the local bluestone from which many of the buildings are constructed.

Aptos Cruz has never advertised and it does not have a sign. But you can’t miss it. It’s in the 1869 bluestone Ashton Memorial Church which sits at the crest of the hill with a verdant and enticing valley as a backdrop. You can’t help but pull off the road and drop in. aptos /æptos/ n.(Amerindian) coming together; cruz /kruz/ n. (Spanish) cross

Directors Steve and Pat Ronayne used to live in a village in California called Aptos, the inspiration for a gallery that brands itself by bringing together different cultures. “We’re a complement,” says Steve. “She’s the designer

– and all the nuts and bolts. I just kind of hang out. But there’s the buying and manufacturing. And I put words to what she is doing.”

It is quite a story. Originally from California, they have been an item now for 38 years, working together in the U.S. and Europe before coming to Sydney in the 1980s where Steve was director and general manager of Design Warehouse with Pat doing the importing. After 10 years, they wanted a break. Steve was offered a position in importing in Adelaide. “That lasted three months,” he says. “It was the worst mistake I ever made. I decided I didn’t want to work for anyone else again.”

So, they hired a campervan and travelled around Australia for six weeks trying to decide what to do next. “Because of my experience,” says Steve, “I hated Adelaide. But nothing worked out elsewhere, so we thought: ‘Why not Adelaide?’”

Starting from where they had left off at

Design Warehouse, they set up in a little cottage in Druid’s Avenue, Stirling, where the key idea was to use room settings to show people how they could use the products on show. “Why would people buy this sort of thing?” asks Steve rhetorically. “The general public had no concept – only the architects. The room setting was a way to soften it.”

When they moved into the church, it had been vacant for 13 years. A firm of engineers had owned it and they had done some renovations and added a mezzanine. “It was unbelievably cheap,” recalls Steve, “but in disrepair.” Later, running out of space, Steve and Pat decided on an extension. Needless to say, the original pitched roof and arched windows of the church give the place a lot of character – for the antiques and tribal art, but not necessarily for their contemporary furnishings and lighting.

According to Con Bastiras, the arched

59 habitus | Issue 03

Text Paul McGillick

Photography Sam Noonan

partnership

windows gave the building an “introverted feel”. So, his strategy for the new extension was to “open it all up, open up to the views and make it suitable for the display of modern furniture – take advantage of the views and contrast it with the existing spaces”.

Con had gotten to know Steve as a supplier of furniture for both residential and commercial projects. “He was familiar with my work,” he recalls, “and wanted something of that language here.”

Working within the original envelope of the building, Con designed a seven-metre extension with new gallery and terrace above, and storage below. He wanted hard, clean surfaces, but also to make it pleasant acoustically – hence, the perforated metal ceiling to prevent echo. The addition itself is supported on the original stonework, which provided a connection between the old and the new, as well as keeping costs down.

Aptos Cruz products have a fascinating range and diversity. On the one hand, there are antiques, contemporary art (they hold six exhibitions a year) and tribal art. On the other, they have a wide range of contemporary furnishings – they are distributors for Corporate Culture, Fontana Arte, Ke-Zu and Kenneth Cobonpue lights, for example, and produce their own products (such as the handsome

I 01

The new extension for contemporary product

I 02

The new extension is unapologetically modern against the old church.

habitus | Issue 03 60 partnership

I 03 Steve and Pat Ronayne upstairs in the original gallery.

I 01 I 02

stainless steel and glass Trapeze table) which are often customised and intended to complement the other ranges.

According to Steve, the “eclecticism of the product” makes the gallery a destination. “People will come and have a look,” he says, “because it is interesting, less intimidating. That’s why we have the books. They had seen an exhibition, but didn’t know what to think. But they could buy a book and the next time they came they were experts.”

I put it to them that their location was surely irresistible, but Steve responds that it is both a plus and a minus. “It is a plus,” he says, “because it is a destination. We’re only 20 minutes away from Adelaide, but the perception is that it is a long way away. Where it is difficult is in the commercial field. It is difficult to get the architects and designers to come up. So, we have to go to them.”

Well, we had dealt with the partnership, the character of the building and the gorgeous location. So, what else has helped Aptos Cruz survive all the economic ups and downs? Steve responds decisively that it is their consistency of quality. Other showrooms can have strengths and weaknesses, he says, but Aptos Cruz’s consistency, coupled with its diversity make it one of the brightest gems among many in the Adelaide Hills.

62

habitus | Issue 03 partnership I 04 Gallery Interior The original upstairs space shows antiques, art and tribal artefacts. I 05 Gallery Detail Contemporary art and ceramics in the original gallery.

Aptos Cruz, aptoscruz@tpg.com.au

I 04 I 05

“People come and have a look because it is interesting, less intimidating. That’s why we have The books.”

STEVE

First called the A811, this early 1920s design may be attributed to Josef Frank. Available with handsewn cane seat and back. European beech frame.

Hoffmann

Melbourne 237 Napier Street, Fitzroy VIC Australia 3065 Freecall 1800 800 777 Phone 03 9417 0077 Fax 03 9417 0011 Email sales@thonet.com.au Sydney 21 Boundary Street, Darlinghurst NSW Australia 2010 Phone 02 9332 1600 Fax 02 9332 4073 Email nsw@thonet.com.au Adelaide 1000 Chairs 45 Gilbert Street, Adelaide SA Australia 5000 Phone 08 8232 2155 Perth Katsui Phone 08 9385 3005 Newcastle HVD Phone 02 4929 6066

on

fashioning fabric: GRACE tan

I She is originally from Malaysia, but these days Grace Tan calls Singapore home. It is here that she is pushing the limits of fashion design, with a unique approach that combines a grounding in mathematics and structure, with a hands-on application of her ideas. Grace speaks to Darlene Smyth about her work and why she takes her inspiration far and wide, from legendary architects to intricate Japanese confectionary.

64

location

Text Darlene

Photography Derek Swalwell, Darren Soh

Smyth grace tan — singapore

habitus | Issue 03