Health in the Margins

IN THIS ISSUE

EDITORS-IN-CHIEF:

Kristen Ashworth

Nayaab Punjani

Kyla Trkulja

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

Beatrice Acheson

Jasmine Amini

Kevan Clifford

Alyona Ivanova

Lizabeth Teshler

DESIGN EDITORS:

Ravneet Jaura (Co-director)

Jinny Moon (Co-director)

Qingyue Guo

Athena Li

Vicky Lin

Josip Petrusa

Raymond Zhang

PHOTOGRAPHERS:

Katherine Guo

Nancy Kim

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM:

Lizabeth Teshler (Lead)

Lielle Ronen

Abigail Wolfensohn

JOURNALISTS & EDITORS:

Aria Afsharian

Stefan Aguiar

Tesam Ahmed

Yalda Champiri

Mya Chronopoulos

Sara Corvinelli

Anthaea-Grace Patricia Dennis

Clarize Donato

Mia Feldman

Sreemoyee Ghosh

Grace Gibson

Katherine Guo

Omar Hassan

Vanessa Ip

Hamzah Khan

Nancy Kim

Josephine Machado

Madeleine Matthews

Christina Pereira

Lielle Ronen

Rubab Shafiq

Steven Shen

Selina Tang

Kowsar Teymouri

Priya van Oosterhout

Abigail Wolfensohn

Saleena Zedan

By Vicky Lin, MScBMC

Letter from the EDITORS

Dear IMS,

Happy Fall!

As Nat King Cole sings, “The falling leaves drift by the window, The autumn leaves of red and gold.”

The falling leaves are definitely drifting by in beautiful colours across Toronto right now, and whether you’re admiring them from the window in campus library, at the lab, or in the hospital, we can all agree: it’s cozy season. Doesn’t it just make you want to curl up with a blanket, a hot cup of coffee, and something great to read? Luckily, we have the reading material for just that kind of day!

In our Fall 2025 issue of the IMS Magazine, we are excited to present the theme Health in the Margins. This issue shines a light on some of the most pressing challenges facing communities in Canada (and around the world) who have long been underserved or underrepresented in the context of healthcare policy, research, and in the clinical and hospital setting—including women, children, BIPOC individuals, LGBTQ2IA+, and other groups.

In this issue, we feature IMS faculty making significant inroads in this field right now, including Dr. Jenny Lau, who is working to break down barriers to palliative care access for those with substance use disorder; Dr. Sloane Freeman, who founded the Research Equity Advocacy in Child Health (REACH) School Network program to better connect school-aged children to health professionals; Dr. Flora Matheson, who is researching interventions to address the hidden determinants of homelessness, addiction, and criminal-legal involvement; and, Dr. Aisha Lofters, who is investigating the health inequities in cancer screening, including those related to income, race, and immigration.

Alongside this impressive line-up of featured faculty, our Viewpoint articles cover a breadth of topics that may spark some important conversations at the dinner table–from an early detection tool for ovarian cancer, to the current barriers to gender-affirming care; from seasonal affective disorder in racialized communities, to inclusive LGBTQ+ healthcare; and from the impacts of the water contamination in Canadian communities, to healthcare inequalities in our federal prisons.

We are also thrilled to spotlight two outstanding members of the IMS community—Nafia Mirza, President of IMS Students’ Association, and Dr. Anna Badner, an IMS alumna making big waves in the world of biotech.

A very warm welcome to our incoming 2025-26 team of designers, who have visually brought this issue to life—thank you, and we are grateful to have you join the team! And of course, a huge thank you to our talented team of journalists and editors, whose hard work makes all of this possible.

We hope you enjoy all of what this issue, and the changing season, has to offer!

With warmest autumn wishes,

Kristen Ashworth

Kristen is a PhD student studying the use of a human-based retinal organoid model to investigate cell therapies for genetic eye disease under the supervision of Dr. Brian Ballios at the Krembil Research Institute.

@K_Ashworth01

Kyla Trkulja

Kyla is a PhD student studying the mechanism of action of novel therapies for lymphoma under the supervision of Dr. Armand Keating, Dr. John Kuruvilla, and Dr. Rob Laister.

@kylatrkulja

Nayaab Punjani

Nayaab is a PhD student examining a neuroprotective drug therapy for cervical-level traumatic spinal cord injury at the Krembil Research Institute under the supervision of Dr. Michael Fehlings.

@nayaab_punjani

Interim

DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE

Dear IMS Community,

Welcome to a new school year!

I am delighted to welcome you to the Fall 2025 issue of the IMS Magazine, themed Health in the Margins.

This is an issue of particular importance, as it explores some of the most persistent health inequities affecting underserved groups in our society, including barriers to care, disproportionate burden of illness, and gaps in health policy and representation. At the same time, this issue highlights the exceptional efforts of members of our IMS community who are working tirelessly to address these challenges through innovative and inclusive research. Some of the featured faculty include Dr. Jenny Lau, Dr. Sloane Freeman, Dr. Flora Matheson, and Dr. Aisha Lofters—all of whom are doing groundbreaking work to improve health outcomes for marginalized communities. In addition, the Viewpoint pieces shed light on some of the most topical concerns in our healthcare system, including disparities in access to care faced by specific groups. In this issue, we are also proud to spotlight IMS student Nafia Mirza and IMS alumna Dr. Anna Badner for their exceptional leadership and accomplishments at IMS and beyond.

At IMS, our goal is to be a global leader in graduate education to improve human health. To do this, we must cultivate an environment that champions innovation, equity, and collaboration, and empowers our trainees and faculty alike to drive meaningful change in health research and care. This makes the topics covered in this issue especially significant, and I encourage you to engage with these important conversations, and to carry them forward within your own work as scientists, physicians, caretakers, leaders, and educators.

I would like to extend an enormous thank you to the journalists, editors, and designers of the IMS Magazine for their wonderful work, and to the Editors-in-Chief, Kristen, Kyla, and Nayaab, for their leadership in bringing the Fall 2025 issue to fruition. I hope the stories within these pages inspire our community to continue advancing equity, inclusion, and compassion in health research as we “turn over a new leaf” this fall.

Sincerely,

Dr. Lucy R. Osborne

Interim Director, Institute of Medical Science

DR. LUCY OSBORNE

Director, Institute of Medical Science Professor of Medicine, University of Toronto

Photo Credit: Dr. Lucy Osborne

Contributors Fall 2025

Aria Afsharian is a second-year MSc student at St. Michael’s Hospital under Dr. Andras Kapus. His research focuses on cell biology, specifically the role of signalling proteins in the antiviral immune response. Apart from the lab, Aria enjoys drawing, reading and working out.

Tesam Ahmed is a first-year MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Daniel Felsky at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Her research investigates the interaction between structural and functional brain changes and genetic factors to influence trajectories of psychosis in youth. Outside of the lab, Tesam loves to read, enjoy nature, and spend time with friends.

Yalda Champiri is a second-year MSc student under the supervision of Dr. Fehlings at Krembil Brain Institute. Her research focuses on enhancing respiratory function following spinal cord injury. She enjoys spending quality time with her puppies and exploring new restaurants when possible.

Sara Corvinelli is a PhD student supervised by Dr. Jacques Lee at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. Her thesis is exploring innovative ways to improve delirium recognition for older people who seek emergency care. When she’s not researching, Sara enjoys ballet, nature walks, and spending time with loved ones.

Mia Feldman is a secondyear MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Isabella Caniggia at the Lunenfeld Tanenbaum Research Institute. They are studying the placental-maternal crosstalk in cardiovascular diseases of pregnancy. In their free time, Mia enjoys reading and exploring different neighborhoods in Toronto!

Grace Gibson is a second-year MSc student in the Biomedical Communications program studying to become a medical illustrator. She aims to work in patient-facing media and outreach focused on the LGBTQ community. In her free time, Grace enjoys reading books and painting.

Omar I. Hassan is an MSc student transferring to PhD in the laboratory of Dr. Michael Fehlings. He studies neuromodulatory and regenerative strategies in spinal cord injury and has a particular focus on translation from laboratory to clinic. Currently his work is focused on restoring chloride homeostasis through repurposed pharmacological agents. Outside of the lab, he enjoys horology, falconry, and yapping over election politics.

omar_hassan1535

Vanessa Ip is finishing up their MSc working with Dr. Vicky Stergiopulos in General Psychiatry and Health Systems Division at CAMH. She is investigating the characteristics of forensic patients designated ALC in the last 5 years, the housing needs and preferences of this population, and their challenges and barriers to accessing housing. Aside from research, Vanessa has a passion for dogs, photography, and espresso.

vanessaaip

HamzahKhanisafourth yearPhDcandidateworking withsupervisorandvascular surgeonDr.Mohammad QaduraatSt.Michaels Hospital.Hisresearchfocuses onthediscoveryofnovelproteinplasma biomarkersforpredictingadversecardiovascular eventsinpatientswithvasculardisease.Outside ofresearchHamzahistheDirectorofPueblo Science,anot-for-profitorganizationthat focusesonincreasingscienceliteracyandcritical thinkinginruralandunderservedcommunities inCanadaandabroad.

Josephine Machado is a second-year MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Andrea Knight at The Hospital for Sick Children. Her research is focused on examining the neuropsychiatric impacts of childhoodonset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) through the study of brain-aging in children with the condition. Outside of research, Josephine enjoys reading, playing the piano, nature walks, and volunteering.

Lielle Ronen is a firstyear MSc student in Dr. Andrew Sage’s Lab at the Latner Thoracic Surgery Research Labs in PMCRT. Her research investigates smoking damage in donor lungs to improve post-transplant outcomes using Ex-Vivo Lung Perfusion (EVLP). Aside from research, she loves painting, baking, running and trying local restaurants in Toronto.

KowsarTeymouri isafourthyearPhDstudentworking underthesupervisionof Dr.JamesKennedyatthe CentreforAddictionand MentalHealth(CAMH). Kowsarisinvestigatingtheroleoftheimmune systemgenesinschizophreniaandhowthey areassociatedwithdifferentsubgroupsof schizophrenia.IfnotatCAMH,youcanfind Kowsartakingcareofherson, runningalongthe lakeshore,orcreatingcontentforhertravelblog. lady.kokolat

Priya van Oosterhout is a second-year MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Yuliya Nikolova at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Priya is investigating how substance use disorders affect the way in which the brain ages, as measured by MRI data. In her free time, she enjoys trying new food, watching movies, or going on hikes.

priya.vo

Copy Editors

Tesam Ahmed

Aria Afsharian

Mya Chronopoulos

Sara Corvinelli

Anthaea-Grace Patricia Dennis

Clarize Donato

Sreemoyee Ghosh

Katherine Guo

Omar Hassan

Nancy Kim

Madeleine Matthews

Christina Pereira

Rubab Shafiq

Steven Shen

Selina Tang

Abigail Wolfensohn

Saleena Zedan

Photography Team

Katherine Guo is a second-year MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Shannon Lange at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Her work focuses on patterns of alcohol consumption and its related harms, aiming to betterunderstand the association between alcohol consumption and suicide mortality. Outside of her academics, Katherine spends her time working on various graphic design projects, taking photos, and exploring the wildlife in and outside of the city.

Nancy Kim is a first-year MSc student under the supervision of Dr. Amanda Boyle at the Center of Addiction and Mental Health. Her research focuses on neuroinflammation in different brain tumours originating from glial cells. She uses PET neuroimaging and histology studies to quantify neuroinflammation for early diagnosis and staging of these tumours. Outside of her research, she enjoys playing volleyball, exploring restaurants (mostly ramen places) and cafes (especially for matcha) near campus.

Social Media Team

Lizabeth Teshler (Lead) is a PhD student supervised by Dr. Brian Feldman at The Hospital for Sick Children. Her research investigates how to improve the clinical examination of musculoskeletal health for people with Hemophilia. Outside of research, she loves biking, spending time outdoors, and exploring new cities.

Abigail Wolfensohn is a second-year MSc student in Dr. Mojgan Hodaie’s lab at Toronto Western Hospital. She is researching how the brain’s waste-clearance system functions in people with trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic facial pain condition. In her free time, she enjoys outdoor activities, puzzles, trying new restaurants, and playing the piano.

abbywolfen

IMS Design Team

The IMS Design Team is a group of 2nd-year MSc students in the Biomedical Communications (BMC) program. Turning scientific research into compelling visualizations is their shared passion, and they are thrilled to contribute to the IMS Magazine

ravneetjaura.com

Vicky Lin

Breaking the Stigma

Working Towards Equitable Palliative Care for People Who Use Drugs

By Lielle Ronen

Prior to the pandemic, people with opioid use disorder (OUD) were 33% less likely to receive palliative care in their final three months of life, with the gap widening to 45% during the COVID-19 period.1 Prescription opioids are essential in managing symptoms, such as pain and shortness of breath, in palliative care.2 Clinical guidelines emphasize the use of opioid therapy to relieve suffering experienced by patients with life-threatening illnesses.3 Despite the central role of opioids in providing relief during palliative care, many people who use(d) drugs face inequitable access to palliative care due to stigma from healthcare providers, restrictive prescribing practices, social inequities, and past negative experiences when accessing the healthcare system. These gaps raise significant questions, such as how healthcare systems can ensure that marginalized populations receive equitable, compassionate, and high-quality care up until the very end of life.

Dr. Jenny Lau, a palliative care physician, clinician-investigator, and medical director of the Harold and Shirley Lederman Palliative Care Centre at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, focuses on developing strategies to deliver palliative care to marginalized populations. Dr. Lau completed her residency in family medicine at the University of Ottawa, followed by palliative care training at the University of Alberta. She then joined the University Health Network as a

palliative care physician and scientist. After witnessing the many challenges people who use(d) drugs encounter in the healthcare system, she pursued a Master of Science with a Collaborative Specialization in Addiction Studies through the Institute of Medical Science at the University of Toronto. Since that time, Dr. Lau and her research coordinator, Rebecca Bagnarol, have established a research program focused on addressing OUD in the context of life-threatening illnesses.

Dr. Lau’s research inspiration is rooted in her clinical practice, where she has observed inequitable access to palliative care for patients with a history of drug use. People who use(d) drugs are often denied access to opioids during end-of-life care due to healthcare provider fears of relapse and non-medical opioid use,4 and these barriers are compounded by additional challenges, including complex medical histories and social inequities like poverty and homelessness. She explains, “One of the goals [of her research] is to try to get a more comprehensive understanding of the needs of this patient population and to identify the gaps that they face.”

To do so, Dr. Lau partnered with Dr. Sarina Isenberg at Ottawa’s Bruyere Research Institute to use the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) provincial database to assess palliative care delivery for people with OUD, while also interviewing patients with life-limiting illnesses and OUD, their caregivers, and health care providers to better understand

their palliative care experiences. Her most recent study found that people with OUD are receiving significantly less palliative care in the last 90 days of life compared to those without OUD, especially in clinics and homes.1 The results of the study highlight the need for innovative solutions to improve palliative care for this patient population. Dr. Lau hopes to establish more tailored models of care to address medical and social needs, as well as to implement clearer guidance for clinicians to safely prescribe opioids to individuals with OUD receiving palliative care.

Dr. Lau utilizes her expertise in various clinical settings within the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, including the outpatient palliative care clinic, inpatient palliative consultation service, and the tertiary palliative care unit. She provides care to a wide range of patients with advanced cancer, from those still in treatment to those at the end of their lives. Inspired by her interactions with patients, Dr. Lau views research as an advocacy tool. She explains, “Through my clinical practice, I identify problems that typical clinical care can’t fix, and these problems are usually systemic problems related to the delivery of healthcare.” She noted that change is underway, and adds, “Through my research, I have an opportunity to try to make a meaningful difference, to try to make a change to the care that I provide to my patients and to advocate for system-level changes.” In practice, this means amending policies and

Dr. Jenny Lau, MD, MSc Clinician-Investigator, Princess Margaret Research Institute; Clinician-Investigator, Division of Palliative Care, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto

guidelines that exclude people who use(d) drugs, collaborating with community organizations to make palliative care more accessible, shaping clinical care to improve opioid prescribing practices, and ensuring patients with life-limiting illnesses receive adequate symptom relief. She has found that patients with OUD are more likely to access palliative care in an acute care setting.1 Care providers in acute settings can better assist with the identification and management of structural vulnerability and OUD. Moving forward, Dr. Lau hopes to build on her previous projects that have identified gaps in patient care, equipping acute care providers with the tools and

resources to improve the delivery of palliative care for this patient population.

Additionally, Dr. Lau is examining equity in cancer care for people with a history of drug use. These patients frequently experience poverty, homelessness, and mental health challenges, making it difficult to navigate a system that assumes stable housing and social supports. Dr. Lau is collaborating with Dr. Melanie Powis, scientific director for the Cancer Quality Lab at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, to identify the structural barriers to equitable cancer care access for these individuals and develop potential solutions on how to overcome them. To do so, she is engaging with people with lived experiences of cancer and drug use, as well as key individuals and organizations. For example, Drs. Lau and Powis are collaborating with the Toronto Harm Reduction Alliance to conduct their project and to engage people who use(d) drugs to improve cancer care for them. Meaningful community engagement is a pillar of Dr. Lau’s work. She highlights, “It all boils down to working with the community, listening to the community and meeting them where they’re at.” In more ways than one, Dr. Lau works with vulnerable populations and centers her work around the voices of those with lived experience.

Dr. Lau specializes in breaking systemic barriers for these underserved populations receiving palliative care, but we all serve a role in achieving these goals and decreasing the stigma associated with OUD. Dr. Lau

emphasizes the importance of interacting with the population she intends to serve, stating that, “The easiest thing that you can do is to treat these people like humans, with respect and dignity.” She highlights the power of language to help people who use(d) drugs feel more welcome when receiving health care. The use of nonstigmatizing language to describe drug use and substance use disorders is a simple strategy that all healthcare professionals can adopt. Through her work, Dr. Lau challenges the notions associated with conventional stereotypes of people who use(d) drugs and encourages people to exercise compassion, curiosity, and a desire to understand an individual’s circumstances. Dr. Lau strives to create a more welcoming and compassionate healthcare system for marginalized populations, moving beyond judgment and towards equitable palliative care.

References

1. Lau J, Scott MM, Everett K, et al. Association between opioid use disorder and palliative care: a cohort study using linked health administrative data in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association journal. 2024 Apr 28;196(16):E547–57.

2. Cleary J. Essential medicines in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2014;28(4):291-2. doi:10.1177/0269216314527036

3. World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief. 1986 Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43944

4. Witham G, Yarwood G, Wright S, et al. An ethical exploration of the narratives surrounding substance use and pain management at the end of Life: A Discussion Paper. Nursing Ethics. 2019 Sept 16;27(5):1344–54. doi:10.1177/0969733019871685

Photo Credit: Dr. Lau

By Aria Afsharian

Around 20 to 30 percent of Canadian children have a mental health or neurodevelopmental problem.1 Children with social inequities often experience barriers accessing health care and are less likely to receive early interventions for neurodevelopmental and mental health problems. This issue was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw increased demand for mental health services as well as increased wait times for seeing healthcare professionals.1 There are major systemic barriers that prevent school-aged children from accessing appropriate care in Canada. One innovative method for alleviating these barriers is by bringing healthcare into the schools.

This is the mission of the Research Equity Advocacy in Child Health (REACH) School Network, as discussed in our interview with its founder, Dr. Sloane Freeman, a pediatric physician at St. Michael’s Hospital and Associate Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Toronto. One of the pillars of St. Michael’s Hospital is its focus on at-risk populations. Pediatrics is an extension of this focus, as children from these disadvantaged families may face further psychosocial problems, especially at school. When asked what drove her towards pediatrics, Dr. Freeman explained, “One of the unique things about pediatrics is the population. Having the opportunity to intervene early in the life course of an individual is very rewarding, especially when you can make meaningful differences

REACHing New Heights: Bringing Healthcare into the School

that impact their future.” This sentiment motivated Dr. Freeman to start the REACH program, a system that connects school children to health professionals.

Schools emerge as a natural environment to connect children with healthcare. Children spend much of their daily time at school, and there is an established system of trust in place between the school system and families. As Dr. Freeman put it, “Merging healthcare and education allows us to overcome many barriers that families may face.” Prior research supports the association between low socioeconomic status (SES) and poor academic outcomes, psychiatric disorders, and chronic health problems in children.2 These same marginalized families also have the greatest difficulties accessing healthcare.3,4 School-based health is not new, with the United States having over 4,000 SchoolBased Health Centres (SBHCs), mostly serving low SES families.1,3,4 Research on American SBHCs have shown an improvement in vaccinations, quality of life, and academic performance, as well as lower hospitalization rates.2 In Canada, SBHCs are emerging as potential avenues for connecting underserved children to healthcare providers.

The REACH School Network is a collaboration between Unity Health Toronto’s hospital networks and the Toronto District School Board (TDSB). Currently the program has two physical SBHCs: one at Nelson Mandela Park Public School, serviced by St. Michael’s

Hospital, and the other at Parkdale Public School, serviced by St. Joseph’s Health Centre. These schools act as hubs, supporting over 150 additional schools to help connect children with mental health and developmental problems to pediatric health care. The centres are staffed by family physicians, pediatricians, therapists, and patient navigators.3 This physicianled team diagnoses and treats mental health and neurodevelopmental disorders, and collaborates with allied health professionals who provide counseling, and direct families to accessible community resources.3 Students are referred to the REACH clinics by school staff, parents, or the School Support Team (SST).3 The SST includes psychologists, social workers, teachers, and other school staff who meet monthly to discuss student wellbeing, and whether individuals’ behaviour or mental health warrants a referral to the program.3 This system is designed for the delivery of precise care to students who need it, allowing for faster, more accessible diagnosis, treatment, and support.

3

Dr. Freeman notes that since REACH and similar systems are still relatively new in Canada, feasibility studies are only just emerging, and additional research is needed to make conclusions about the efficacy of the program. A recent pilot study on the REACH program examined the feasibility of Coping Power, an evidence based cognitive behavioural intervention method, on the mental health of children.1 The 10-week program aimed to improve children’s social competency

the SBHC setting, which was unexpected given that boys are usually diagnosed at a higher rate, likely due to them displaying more obvious symptoms that help with early recognition compared to girls.2 It is believed that the increased accessibility of SBHCs may improve the detection of psychosocial disorders in girls that would otherwise be overlooked.2

can the REACH program continue its mission in connecting children with health professionals. Increased governmental awareness and visibility are necessary to ensure the continued delivery of accessible and efficient care for our most vulnerable patient populations.

and self-regulation. At the end of the study period, parents/guardians were asked to fill out a follow-up survey.1 13 out of 18 participants (parent/guardianchild dyads) who completed the program and the survey reported being somewhat or very satisfied with the program.1 An earlier retrospective feasibility study on SBHCs reviewed the charts of 379 children enrolled at a SBHC over one year.2 Most children were from low-income families whose first language was not English.2 Of the 127 children who attended the clinics, 74% received a new diagnosis and 90% received a treatment plan.2 Interestingly, more girls were diagnosed than boys in

It remains unclear whether SBHCs impact children’s academic outcomes. A recent quasi-experimental prospective cohort study on 14 TDSB schools compared measures of academic achievement between students who had access to SBHCs and those who did not during the 2016/2017 to 2018/2019 school years.3 While there was insufficient evidence to show a difference in grades, many children who accessed the SBHCs received a new neurodevelopmental diagnosis.3 Several limitations in this study, including COVIDmediated school closures, further the need for additional research on the matter.3

Nonetheless, Dr. Freeman’s passion for the vast potential and importance of the REACH program is evident. She explains that “In a perfect world, in the next decade, the program will expand. More health centres will be built, allowing us to expand throughout Toronto.” The biggest limiting factor to this expansion is funding; “Bringing this to the attention of the government and Ministry of Health is critical for our program’s sustainability,” Dr Freeman says. Only with sustained funding and support

References

1. Rasiah S, Andrade BF, Cohen-Silver J, et al. Coping Power at the REACH School Network: A pilot feasibility study. Paediatrics & Child Health [Internet]. 2024 Nov 17 [cited 2025 Aug 14];29(8):493–500. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/ pxae060

2. Freeman S, Sgro M, Wormsbecker A, et al. Feasibility study on the Model Schools Paediatric Health Initiative pilot project. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2013 Aug;18(7):361–5.

3. Rasiah S, Jüni P, Sgro MD, et al. School-based health care: improving academic outcomes for inner-city children—a prospective cohort quasi-experimental study. Pediatric Research [Internet]. 2023 Feb 8;(94):1488–95. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pmc/articles/PMC9907190/

4. Freeman S, Sgro M, Mamdani M. Novel approach to health care delivery for inner-city children. Canadian Family Physician. 2013 Aug;59:816–7.

Dr. Sloane Freeman, M.D., FRCPC, MSc., UofT Department of Pediatrics

Photo Credit: Dr. Sloane Freeman

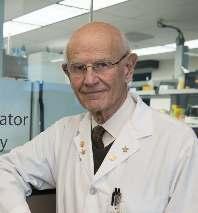

Diving into Hidden Drivers and Fragile Supports in Marginalized Populations through Flora Matheson

By Omar I. Hassan

As a liberal democracy that is shaped by social democratic values, Canada carries the duty to safeguard not only the rights of its citizens but also uphold the dignity of its most marginalized. In the face of rising homelessness,1 addiction,2 and overrepresentation of racialized individuals in the criminal-legal system,3 Canada is losing ground in upholding its own values. These issues signal major systemic failures. It is precisely in this context that researchers focused on inequities intersecting with social determinants of health become critical. Dr. Matheson, a sociologist and the Endowed Chair in Homelessness, Housing, and Health at Unity Health Toronto, recounted her experiences growing up in Prince Edward Island in a small village where there was “a lot of differentiation based on income status.” Her experience inspired her to determine the origins of these disparities. With a vested interest in addressing societal inequity, Dr. Matheson combines academic rigor and community collaboration to uncover the drivers of these systemic failures and develop innovative interventions.

Dr. Matheson provides novel and compelling new perspectives to examine inequities. She has developed a career centred around community-engagement in research that bolsters academic inquiry through lived-experiences. Instead of imposing research questions in a top-down manner, Dr. Matheson engages in dialogue with local organizations such as homeless shelters and advocacy groups to orient her research. This strategy allows her to uncover the hidden causes of marginalization.

Her significant collaborations with the Good Shepherd Ministries resulted in the first Canadian shelter-based study tying gambling to housing instability.4 The later development of the Problem Gambling App (SPRinG app) showed a novel method to extend gambling supports digitally to those without stable housing. Furthermore, Dr. Matheson has found brain injury (BI) rates to be a hidden, yet determining factor, in criminal-legal involvement–pushing for policy implementation and greater accommodation. These initiatives exemplify the strengths of Dr. Matheson’s work, which is not only scientifically rigorous but also vertically integrated in community needs.

In 2013, Dr. Matheson launched a landmark research project in collaboration with the Good Shepherd Ministries men’s shelter in Toronto. Her project revealed a troubling gap: despite a focus on services for substance use, mental health, and housing, gambling remained an unrecognized driver of homelessness. Acting on this concern, Dr. Matheson and her team conducted the first shelter-based prevalence study in Canada. Of the 264 clients interviewed, 35% reported problems with gambling, compared to just 4% in the general population.5 The nine-fold difference suggests that gambling is likely a strong contributor to housing instability. Acting on these results, Dr. Matheson and her team supported the establishment of the Gambling Addiction Program (GAP) by the Good Shepherd Ministries. Funded by the Local Poverty Reduction Fund, the three-year GAP intervention offered case management, cognitive behavioural therapy,

and support from Gamblers Anonymous (a standalone self-help group).4 Dr. Matheson recalled fondly that “clients showed great enthusiasm and described GAP as uniquely supportive and understanding of their environments and experiences.” Despite these positive responses, this program was discontinued due to a lack of funding, a recurring theme that exposes the fragility of our current program-based government models. Dr. Matheson’s work bolsters community driven priorities but is constrained by short-term policy cycles.

Building on her shelter-based research, Dr. Matheson increased outreach through digital innovation, reaching marginalized populations on a larger scale. The SPRinG (Supporting People Recovering from Gambling) app was designed by Dr. Matheson and her team to provide “flexible, accessible support for individuals experiencing problem gambling, particularly those who did not have stable housing or found themselves underserved by traditional [in-person] treatment programs,” she said. The app used evidence-based tools derived from cognitive behavioural therapy and provided easier access to educational resources and support/crisis networks.4 The design reflected a curious insight from Dr. Matheson’s work: while homelessness is often associated with disconnection, many unhoused individuals use smartphones, allowing for digital equity interventions. The SPRinG app extended care beyond the shelter walls, and provided useful resources for unstably housed individuals, mitigating risk of homelessness. Like the

(This is for spotlight photos! Delete this later.)

solutions to directly address service gaps but remain vulnerable to structural issues.

Good Shepherd initiative, the program was discontinued when funding expired. Dr. Matheson explained that, despite promising results, “The SPRinG app has sprung; we had to decommission the app as we could not find additional funding to keep it going. We built it with our community partners and people with lived experience. We tried to get funding through the [gambling] industry and through Government options; we even participated in the University of Toronto Early-Stage Technology (UTEST) program.” Despite promising feedback, the program was cut short due to a lack of long-term funding sources. Dr. Matheson’s approaches are innovative and provide community-informed

Alongside her work on gambling, Dr. Matheson has pushed frontiers in inequity research within the criminal-legal system. By documenting BIs in people who are incarcerated, she and colleagues found that young adults with a history of traumatic BI (those caused by external blows to the head) were over 2.5 times as likely to experience incarceration than those without, and the trend impacts both men and women.6 Further, her research found that the prevalence of these injuries increased the risk of a serious disciplinary charge by 39%.7 BI limits individuals’ abilities to navigate the criminal-legal system, from police questioning to hearings, and increases the chance of cyclical incarceration. Despite these findings, Dr. Matheson noted that “we have very few brain injury services available in Ontario with long wait lists and many of them require a formal diagnosis of brain injury to access care.” She also remarked the difficulty in getting such diagnoses, “leaving many people without access to care.” Despite this, Dr. Matheson remains hopeful. She said that with more “funding and training we can see improvement.” She continues her research in the hopes of her advocacy shaping structural change. Dr. Matheson’s findings have informed policy discussions in Ontario with calls to include BI screening in with correctional health records. This way, Dr. Matheson has ensured that her research uncovers more hidden inequities while seeking to mitigate system-level shortcomings to address such inequities.

Dr. Matheson’s work demonstrates the strengths and vulnerabilities of community-engaged health research in Canada. Whether through GAP, SPRinG, or BI screening, Dr. Matheson exemplifies a consistent pattern: her research is empirical, rigorous, community-focused, and promotes equity. These successes, however, are often dampened by programbased funding cycles. In the face of these challenges, Dr. Matheson remains determined to “keep plugging away at it” even if “our government has expanded the number of prisons rather than community healthcare.” Dr. Matheson has proved the value of her research through effective interventions, but the premature discontinuation of these programs underscores the urgent need for sustained structural investments in solutions for marginalized communities. Without such investments, Canada risks allowing further innovative and community-centred progress to wither.

References

1. Statistics Canada. Homelessness: How does it happen? (2023).

2. Miller J and Carberg C. Addiction Statistics Canada (2025).

3. Office of the Correctional Investigator. 2020-2021 Annual Report (2022).

4. Matheson FI, Hamilton-Wright S, Hahmann T, et al. Filling the GAP: Integrating a gambling addiction program into a shelter setting for people experiencing poverty and homelessness. PLOS ONE 2022.

5. Matheson FI, Devotta K, Wendaferew A, et al. Prevalence of gambling problems among the clients of a toronto homeless shelter. J Gambl Stud 2014. DOI: 10.1007/s10899-014-9452-7.

6. McIsaac KE, Moser A, Moineddin R, et al. Association between traumatic brain injury and incarceration: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open 2016. DOI: 10.9778/cmajo.20160072.

7. Matheson FI, McIsaac KE, Fung K, et al. Association between traumatic brain injury and prison charges: a population-based cohort study. Brain Injury 2020. DOI: 10.1080/02699052.2020.1753114.

Dr. Flora Matheson

Associate Professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, the Institute of Medical Science, and the Centre for Criminology & Sociolegal Studies at the University of Toronto.

Photo Credit: Dr. Flora Matheson

Cancer Screening Inequities in Ontario

The Work of Dr. Aisha Lofters

By Kowsar Teymouri

Cancer is a leading cause of death in Canada, with one in every 2.2 Canadians expected to be diagnosed with cancer in their lifetime.1 Cancer screening has been proven to reduce cancer morbidity and mortality rates;2 thus, it is a crucial part of primary care in Ontario.3 Despite efforts to provide comprehensive cancer screening for the entire population at no cost, there are well-documented inequities across Ontario, especially for people of low socioeconomic status, people living in low-income neighbourhoods, and immigrants. These complex barriers exist at the level of the patient, provider, and overall healthcare system.

Dr. Aisha Lofters, a family physician and clinician-scientist at Women’s College Hospital, and an Associate Professor at the Institute of Medical Science and Dalla Lana School of Public Health, has dedicated her research to investigating health inequities in cancer screening. Social justice was always at the forefront of Dr. Lofters’ upbringing, which cultivated her strong interest in addressing inequalities, regardless of the career path she chose.

After obtaining her medical degree at the University of Maryland, Dr. Lofters completed her residency and fellowship in family medicine at the University of Toronto (UofT). Dr. Lofters was interested in family medicine as it prioritizes powerful, but simple tools:

prevention and screening. Dr. Lofters believes that while cancer treatment is important, “catching it early can really change the trajectory of someone’s life.” During her residency, Dr. Lofters, under the supervision of Dr. Rick Glazier from St. Michael’s Hospital, investigated cervical cancer screening in areas with higher proportions of new immigrants and low-income individuals. This project inspired her to pursue her PhD in Clinical Epidemiology and Health Care Research at UofT and later become a clinician-scientist.

Dr. Lofters’ research aims to answer the fundamental question: “Where are the inequities in care?” To do so, she leverages quantitative methods on population-level data to address where and for whom these inequities in cancer screening exist. Then, she implements qualitative methods to gain a deeper understanding of why these disparities exist and eventually identify solutions for alleviating them. Dr. Lofters believes there is an interplay between discrimination on the bases of income, race, and immigration, which contribute to these disparities—highlighting the underlying theme of health equity in her work.

Dr. Lofters’ work has a particular focus on cervical cancer screening. Her studies have demonstrated that immigrant women who are newer to the country, as well as those living in low-income neighbourhoods, had lower uptake of available screening programs.4 Screening

rates also varied among immigrant women, with the lowest rates observed in South Asian, Middle Eastern, and North African women. Considering Ontario’s universal healthcare system covers the direct financial cost of cervical cancer screening, understanding the indirect costs that prevent usage in these populations is important. To address this, Dr. Lofters, in collaboration with Dr. Mandana Vahabi, has conducted qualitative studies on Muslim women from the aforementioned countries.4,5 Cultural barriers pertaining to modesty and privacy—particularly with limited same-gendered providers—as well as access to transportation and childcare, limit visitations. Furthermore, some patients lack access to a general practitioner and have limited knowledge about cervical cancer screening, restricting their ability to self-advocate. In some instances, patients didn’t have the opportunity to be screened as the test was not offered to them. This study highlights key patient, and importantly, practitioner factors which are important to consider when determining the effective uptake of screening programs.5,6

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection is responsible for nearly all cervical cancer cases.7 Ontario Health recommends conducting an HPV test as part of its cervical cancer screening program.8 However, the experience of having a healthcare provider collect a vaginal swab could be traumatizing or

Looking at immigrant health is looking at the health of our population. “ “

uncomfortable for some women, which may discourage them from undergoing screening. HPV self-collection kits offer an alternative which allows patients to collect the swab at home. Currently, HPV self-collection kits have been implemented in British Columbia, Australia, and parts of Europe. Dr. Lofters has studied the acceptability and uptake of these kits in Ontario and is currently investigating the most effective ways to implement them into the province’s cervical cancer screening program. 9

In addition to the concerns associated with the screening process, some patients also delay seeking care following a previous

unpleasant experience with the healthcare system or a lack of knowledge about the symptoms. Dr. Lofters said that “in Canada, cancer is not a death sentence.” In fact, two in five Canadians will develop cancer over their lifetime, and only one in five will die from it.10 Healthcare providers should, therefore, educate patients about the symptoms and create a safe space where patients feel comfortable seeking care before it is too late.

Dr. Lofters’ work extends beyond cervical cancer. In collaboration with Dr. Ambreen Sayani, she has investigated lung cancer in marginalized communities.11 They observed that rates of lung cancer are higher among low-income individuals, and this correlates with increased smoking rates in the low-income population.11 Further stigmatization surrounding income status and smoking may compound to create additional barriers to care in these populations.11

As Canada’s immigration rates rise, Dr. Lofters emphasized that the healthcare system should monitor health outcomes in immigrants and how they are influenced by their home country, income, and immigration path. According to Dr. Lofters, “looking at immigrant health is looking at the health of our population.” In addition, Dr. Lofters believes that we, as the general public, can alleviate the healthcare disparities by recognizing and leveraging our power and privilege to support others in society.

Cancer screening has proven to reduce cancer-related morbidity and mortality. Dr. Lofters is leveraging her expertise and passion for health equity to address the needs of marginalized populations to enhance cancer screening programs in Ontario. Dr. Lofters’ advice to young investigators interested in studying health inequities is to find the niche that they are most excited about, as there are still many opportunities in this realm to address the historical gaps in the field.

References

1. CCSD | Home [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://cancerstats.ca/

2. Cancer | Ontario Health [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.ontariohealth.ca/clinical/cancer

3. Lofters AK, Mark A, Taljaard M, et al. Cancer screening inequities in a time of primary care reform: A population-based longitudinal study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1).

4. Lofters AK, Hwang SW, Moineddin R, et al. Cervical cancer screening among urban immigrants by region of origin: A population-based cohort study. Prev Med (Baltim). 2010;51(6).

5. Lofters AK, Vahabi M, Kim E, et al. Cervical cancer screening among women from Muslim-majority countries in Ontario, Canada. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2017;26(10).

6. Marshall S, Vahabi M, Lofters A. Acceptability, Feasibility and Uptake of HPV Self-Sampling Among Immigrant Minority Women: a Focused Literature Review. Vol. 21, Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2019.

7. Walboomers JMM, Jacobs M V., Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. Journal of Pathology. 1999;189(1).

8. Cervical Screening | Cancer Care Ontario [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/ types-of-cancer/cervical/screening?utm

9. Devotta K, Vahabi M, Prakash V, et al. Reach and effectiveness of an HPV self-sampling intervention for cervical screening amongst under- or never-screened women in Toronto, Ontario Canada. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1).

10. Lifetime probability of developing and dying from cancer in Canada - Statistics Canada [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/4547-lifetime-probability-developing-and-dying-cancer-canada?utm

11. Ruco A, Lofters AK, Lu H, et al. Lung cancer survival by immigrant status: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Cancer [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Aug 14];24(1):1114. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ articles/PMC11380402/

Dr. Aisha Lofters, MD, PhD. Associate Professor, University of Toronto

Photo Credit: Dr. Aisha Lofters

Master of Science in Biomedical Communications

Winter Kraemer

Winter is a current MScBMC student with a focus on 2SLGBTQ+ Health. He is interested in communicating the complexities of healthcare to patients and healthcare providers alike. You can see more of his work on his website: winterkraemer.cargo.site

Vicky Lin is a first-year Master’s student in the Biomedical Communications program at the University of Toronto with a background in Biology from McMaster University. She has worked extensively in multimedia design and print publishing in her previous work experience and is eager to use her passion for science visualization to make tools that help make science accessible for wider audiences.

Vicky Lin

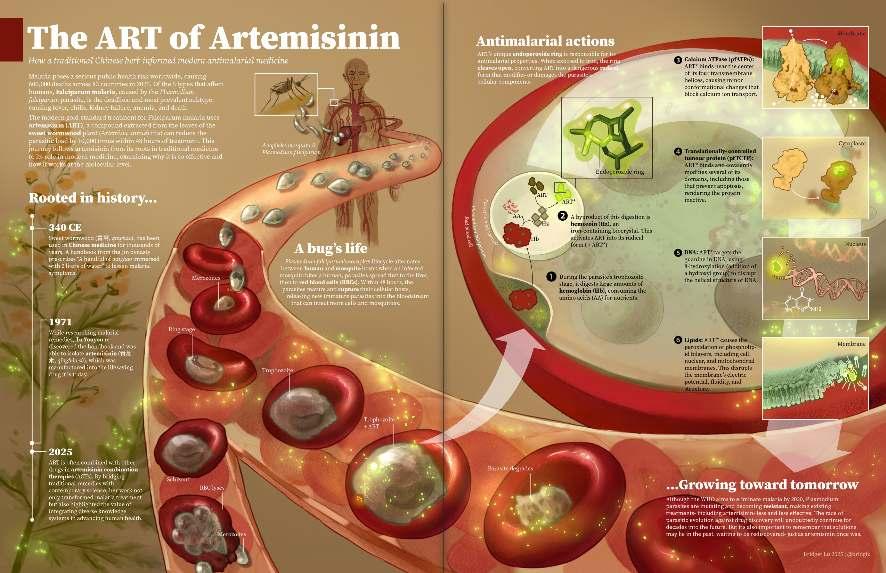

The ART of Artemisinin

Bridget Lu

Bridget is a biomedical communications student and artist aiming to create work that’s not only accurate and informative, but also beautiful to look at. Driven by curiosity and creativity, she enjoys exploring complex ideas and creating visuals that inspire viewers to look more closely at the world around them.

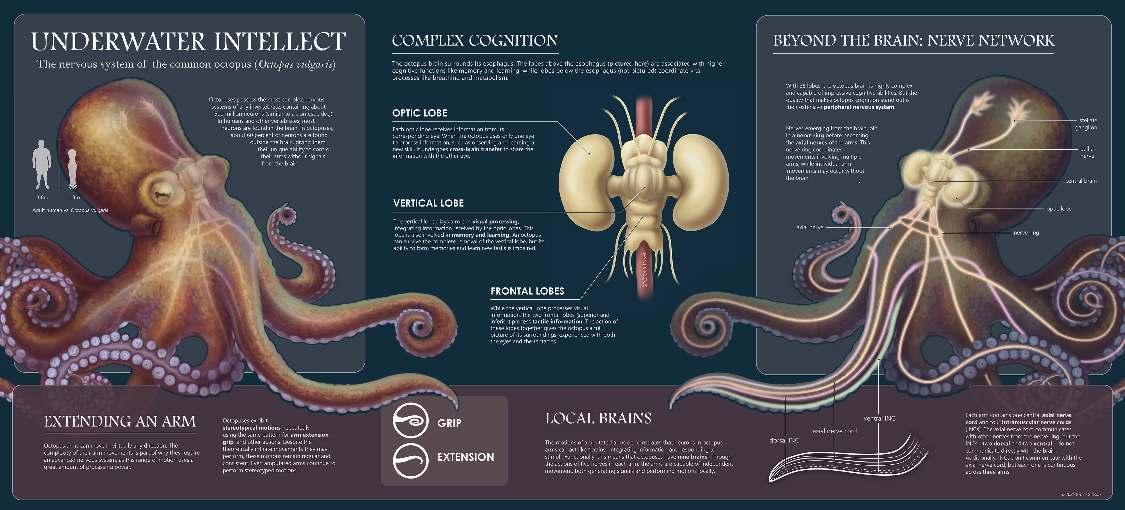

Underwater Intellect: The Nervous System of the Common Octopus

Grace Gibson

Grace Gibson is a second-year MSc student in the Biomedical Communications program studying to become a medical illustrator. She aims to work in patient-facing media and outreach focused on the LGBTQ community. In her free time, Grace enjoys reading books and painting.

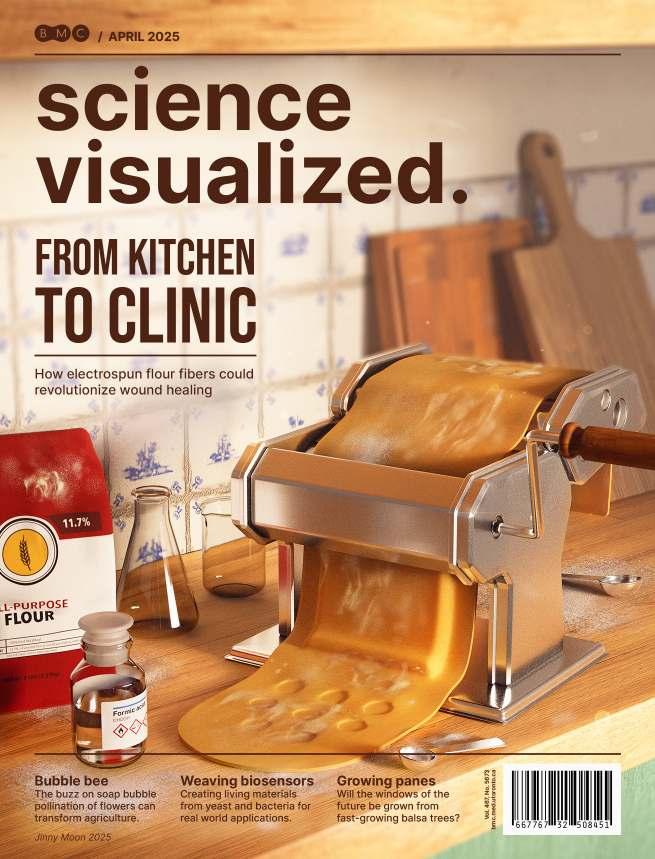

From Kitchen To Clinic

Jinny Moon is a biomedical communicator and designer studying in the Master of Science in Biomedical Communications (MScBMC) program. With a background in anatomy and cell biology, she explores how visual storytelling can bridge disciplines—translating ideas in neurobiology, mental health, and public health into meaningful connections between science and society.

* This piece was awarded the Award of Excellence in Student Still Media at the 2025 Association of Medical Illustrators Salon.

Cathy is a second-year MScBMC student in Toronto, Canada. She is particularly interested in pharmacology and toxicology, and new, inventive graphic design. You can find her work on her website at cathyzhou.com.

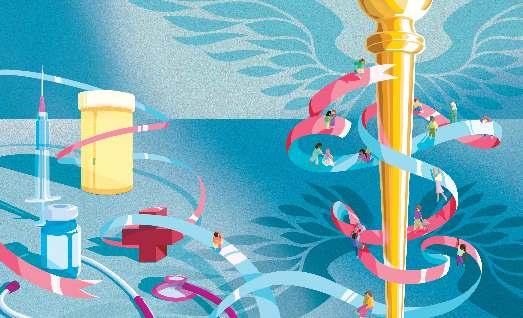

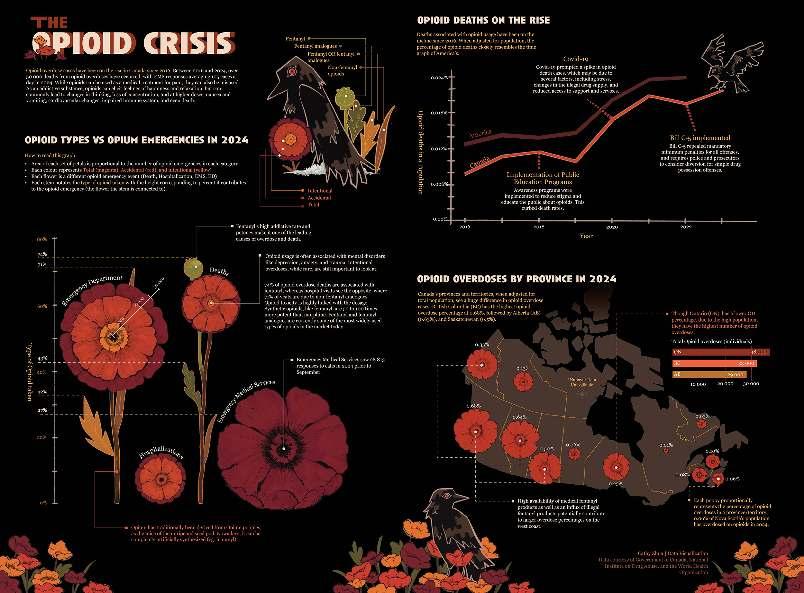

The Opioid Crisis in Canada

Cathy Zhou

Jinny Moon

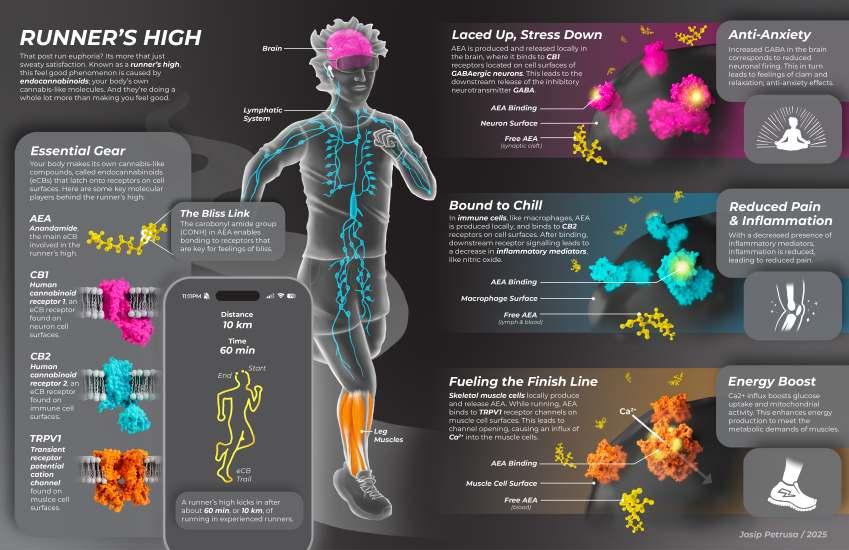

High Josip Petrusa

Josip is in his second year of studies in the Master of Science in Biomedical Communications program. He strives to bring science to life through visual storytelling, making science accessible and engaging for all.

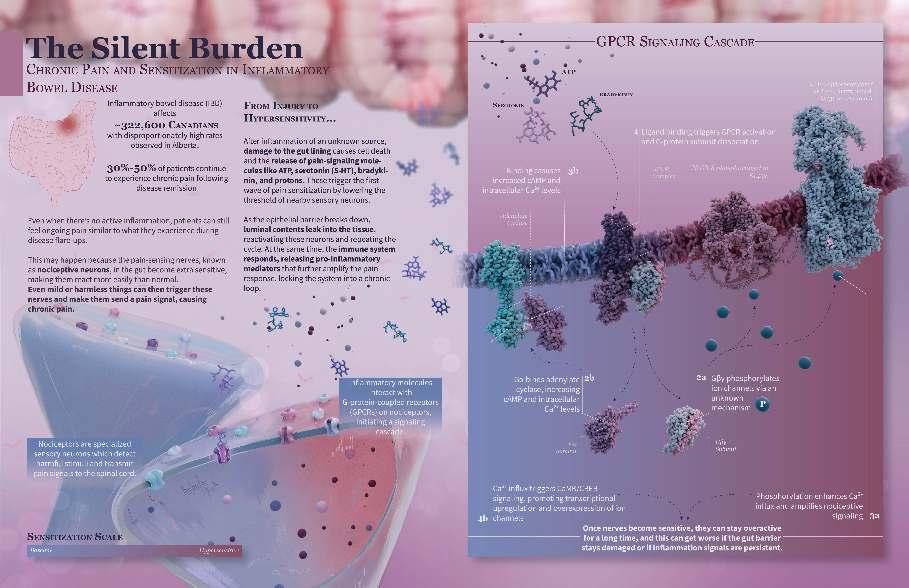

The Silent BurdenA Visualization of Chronic Pain in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Eve Higgins

I began my journey in science communication during my BHSc in Biomedical Sciences at the University of Calgary, where I discovered the power of visuals in making complex topics clearer. Through my honours thesis on WNT signalling and later work in Dr. Derek McKay’s lab, I combined research in immunology and physiology with creating scientific figures and patient-focused resources. Today, I focus on transforming complex data into clear, engaging visuals, because great science should be accessible to everyone!

Liquid Biopsy: A Promising Application in Ovarian Cancer

By Tesam Ahmed

Ovarian cancer, the most fatal female reproductive cancer in the world, is responsible for over 240,000 new cases and 150,000 deaths in women every year.1,2 There are various risk factors associated with its development, including obesity, diet, physical inactivity, and advanced age (>65 years).3

High mortality rates in ovarian cancer are, in part, a result of its frequent late-stage detection. Decreased efficacy of surgical or pharmacological therapies result from approximately 75% of cases being diagnosed when the disease is in its advanced stages.4,5 The presentation of ovarian cancer often includes vague, nonspecific symptoms that are late in onset. In addition, surveillance is generally only reserved for populations at high-risk, such as those with known genetic mutations or a strong family history.6 The five-year survival rate for women with advanced ovarian cancer is alarmingly low, hovering around 20%.5 These statistics highlight the urgent need for improved early detection strategies.

Current ovarian cancer diagnostic tools, including serum markers like CA-125, imaging, and tissue biopsy approaches, present with limitations. CA-125 lacks adequate sensitivity and specificity in detecting earlystage disease. Tissue biopsies

are physically invasive, presents with limitations for longitudinal monitoring, and is spatially limited. Ovarian cancer treatment and diagnostics are in urgent need of tools that are minimally invasive, sensitive, and capable of detecting early or minimal residual disease (MRD), a small number of cancer cells that remain post-treatment and may lead to relapse.8,9

In this context, liquid biopsies have emerged over the past decade as a promising, non-invasive molecular screening and monitoring tool. Unlike traditional tissue biopsy, liquid biopsy serves to measure various tumour-derived components in peripheral blood: cell-free RNA (cfRNA), circulating tumour cells (CTCs), tumour DNA (ctDNA), tumour-educated platelets (TEPs), and exosomes. Tumours are hypothesized to release these components into the bloodstream via one of three primary mechanisms: secretion, apoptosis (regulated cell death), or necrosis (unregulated cell death). 9

Decoding Tumour Biology Through the Blood

Circulating Tumour Cells (CTCs) are cells deriving from the primary tumour site that have entered the circulatory or lymphatic system.10 CTCs have properties distinct from

cells of the primary tumour, and can be isolated from blood using various methods, based on their biological surface markers or underlying physical properties, including size, density, and electric charge.9,11

Cell-free RNA (cfRNA), consisting of mRNA and microRNA (miRNA) are produced as a result of high levels of gene transcription caused by quick tumour turnover. cfRNA in the plasma provides information about the body’s response to tumour growth, and about the tissue of tumour origin.12 miRNA specifically has also been implicated in tumour metastasis, genesis, and apoptosis.9

Tumour-Educated Platelets (TEPs) play an important role in the progression of tumour growth. 13 The “education” component of their name refers to the process of sequestration of tumour cell biomolecules into platelets, leading to changes in their RNA and profiles of protein expression. TEPs are involved in the systemic and local response of the body to cancer, changes in their profile make them a useful diagnostic biomarker, providing information about tumour bioactivity, and cancer progression. 14

Exosomes are small extracellular vesicles (EVs) released from both healthy and cancerous cells.9 Exosomes are released in higher

levels from cancerous cells than normal ovarian epithelial cells, providing utility in ovarian cancer detection.15 In addition, exosomes are involved in cancer progression, drug resistance, and tumour metastasis.16

Clinical Utility and Future Potential

Liquid biopsy, compared to standard techniques, offers several clinical advantages. It is noninvasive, allows for earlier detection and temporal surveillance of ovarian cancer, and for a more precise prognosis.17 By analyzing various tumour components within collected samples of plasma, treatment resistance, and molecular therapy targets can be identified. The ability of liquid biopsy to carry out non-invasive routine screening in the general population is also beneficial.9

Despite its promise, liquid biopsy is not without limitations. In my view, while these challenges are significant, they are not insurmountable. Technical challenges include variability in isolation methods, and low abundance and instability of molecules of interest. Research also suggests that liquid biopsy may be more effective when used as a complementary tool rather than singularly when determining clinical approach. I believe this emphasizes the importance of integrating tools

including liquid biopsy into a broader diagnostic strategy. Ongoing research is focused on improving methods of detection for specific cell types and establishing standardized protocols for implementation.9

It appears the future of ovarian cancer may lie in the bloodstream. In my opinion, liquid biopsy has the potential to become a crucial component of the diagnostic toolbox, as research advances its techniques and broadens its uses.

References

1. Proin ullamcorper suscipit hendrerit. Mauris lacinia tortor vel tellu Coburn SB, Bray F, Sherman ME, et al. International patterns and trends in ovarian cancer incidence, overall and by histologic subtype: Ovarian cancer trends. Int J Cancer. 2017 Jun 1;140(11):2451–60.

2. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Intl Journal of Cancer [Internet]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijc.29210

3. Stewart C, Ralyea C, Lockwood S. Ovarian Cancer: An Integrated Review. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2019 Apr;35(2):151–6.

4. Hennessy BT, Coleman RL, Markman M. Ovarian cancer. The Lancet. 2009 Oct;374(9698):1371–82.

5. Schiavone MB, Herzog TJ, Lewin SN, et al. Natural history and outcome of mucinous carcinoma of the ovary. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011 Nov;205(5):480.e1-480.e8.

6. Golia D’Augè T, Giannini A, Bogani G, et al. Prevention, Screening, Treatment and Follow-Up of Gynecological Cancers: State of Art and Future Perspectives. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Aug 2;50(8):160.

7. Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Hallett R, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Lancet Oncol. 2009 Apr;10(4):327–40.

8. Della Corte L, Russo G, Pepe F, et al. The role of liquid biopsy in epithelial ovarian cancer: State of the art. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024 Feb;194:104263.

9. Zhu JW, Charkhchi P, Akbari MR. Potential clinical utility of liquid biopsies in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022 Dec;21(1):114.

10. Lin D, Shen L, Luo M, et al. Circulating tumour cells: biology and clinical significance. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2021 Nov 22;6(1):404.

11. Pantel K, Speicher MR. The biology of circulating tumour cells. Oncogene. 2016 Mar 10;35(10):1216–24.

12. Roskams-Hieter B, Kim HJ, Anur P, et al. Plasma cell-free RNA profiling distinguishes cancers from pre-malignant conditions in solid and hematologic malignancies. NPJ Precis Onc. 2022 Apr 25;6(1):28.

13. Haemmerle M, Stone RL, Menter DG, et al. The Platelet Lifeline to Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities. Cancer Cell. 2018 Jun;33(6):965–83.

14. Ding S, Dong X, Song X. Tumour educated platelet: the novel BioSource for cancer detection. Cancer Cell Int. 2023 May 11;23(1):91.

15. Taylor DD, Homesley HD, Doellgast GJ. “Membrane‐Associated” Immunoglobulins in Cyst and Ascites Fluids of Ovarian Cancer Patients*. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 1983 Jan;3(1):7–11.

16. Tian W, Lei N, Zhou J, et al. Extracellular vesicles in ovarian cancer chemoresistance, metastasis, and immune evasion. Cell Death Dis. 2022 Jan 18;13(1):64.

17. Feng W, Dean DC, Hornicek FJ, et al. Exosomes promote pre-metastatic niche formation in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019 Dec;18(1):124.

The Necessity of Gender-Affirming Surgery

By Grace Gibson

Recognition of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people— individuals whose gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth—has greatly increased over the past decade. Correspondingly, as more people have come to identify as transgender and gender non-conforming, the medical field has seen increased demand for genderaffirming healthcare—medical treatments that contribute to a patient’s gender transition.1 Despite these interventions being medically necessary for many patients,2 the politicization of transgender healthcare and the growing movement of anti-trans legislation throughout North America threatens their accessibility to patients in need.3,4 Promoting access to gender-affirming care helps TGD people, an already underserved group, avoid further marginalization in seeking healthcare.

Gender-affirming care, also called transition-related care, consists of medical interventions like hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and genderaffirming surgery (GAS) that enables a patient’s physical traits to more closely align with their gender identity.5 This often reduces gender dysphoria, a state of distress or discomfort caused by the incongruence between one’s gender identity and physical characteristics.6 While every person’s transition is unique, many TGD people seek out one or more forms of GAS as part of their transitionrelated care.7 Though the popularity and visibility of transition-related surgeries have increased in recent years,1 these

surgeries are not as new or experimental as they may seem. Many modern forms of GAS—including orchiectomy (removal of the testes), penectomy (removal of the penis), and vaginoplasty (construction of a vagina)—originated in the early 20th century with the work of surgeon Magnus Hirschfeld at the Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin, Germany.1,9 While historical understandings of gender identity differed widely from modern standards, patients undergoing GAS at the time reported therapeutic benefits from receiving these surgeries, and outcomes only improved throughout the mid-20th century as surgeons refined and shared their techniques.1 Modern surgeons established current practices of GAS from over a century of development in surgical techniques, making many transitionrelated surgeries older than procedures like coronary artery bypass (first performed in 1960),10 heart transplantation (1967),11 and total knee replacement (1966-68).12

From the earliest days of GAS, the primary goal of surgery was to align a patient’s physical traits with their gender identity; however, secondary outcomes go beyond a simple resolution of this incongruence. Though some of these procedures may be labelled as cosmetic, there is significant evidence that receiving GAS is medically necessary and even life-saving for TGD patients.2 Postoperative GAS patients experience significant clinical benefits, including improved body image, fewer hospitalizations related to mental health emergencies, reduced suicidal ideation

and suicide attempts, and even reduced tobacco use.13 These improvements persist in both the short and long term.13,14 There is further evidence that even when patients experience complications or dissatisfaction with their surgical outcomes, few express regret for having received GAS—overall regret rates for all gender-affirming procedures are reported between one and two percent according to recent reviews.13,15,16 Gender-affirming procedures appear to offer their recipients significant improvements without equivalent drawbacks that induce postoperative regret.

Due to these factors, access to transitionrelated care is crucial for the well-being of TGD patients. Despite this, many TGD people face significant barriers to receiving healthcare, whether transition-related or not. Many healthcare providers are

undereducated about the needs of TGD patients, limiting their ability to provide culturally competent care that addresses the specific challenges that these patients experience.17,18 Some TGD people report facing discrimination or harassment from medical professionals, and even those who encounter sympathetic clinicians often find they are unaware of the healthcare needs of TGD patients, placing a burden on the patients to educate their providers.18 Beyond these barriers to accessing medical care, pursuing GAS comes with its own challenges, including outdated methods for assessing eligibility for GAS and few surgeons specializing in these procedures.2,17

Due to a rise in politically motivated transphobia, legislation aiming to limit transition-related healthcare has become prevalent throughout the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK), with similar legislation being introduced in some regions of Canada.3,4,20 Such social and political opposition to genderaffirming healthcare is not new. In an extreme example, Nazi book burnings in the 1930s targeted Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research, where many advancements in modern GAS originated.1 For several decades following this destruction of research and medical advancement, the amount of surgeons practicing GAS remained scarce because of societal and political opposition to this kind of medical care.1 Public perceptions and awareness of TGD people have shifted since the mid-1900s; however, recent years have seen a rise in misinformation

about transgender healthcare and a surge in transphobia, leading to extensive legislation banning or limiting certain forms of gender-affirming care.3,4,19

Throughout the US, lawmakers introduced 120 anti-trans bills—many of which restricted transgender healthcare—in November and December 2024 alone,19 while in the UK, extensive anti-trans legislation has limited access to and even criminalized transition-related care in some circumstances.3 In Canada, federal protections for TGD people are currently robust, but 2024 legislation in Alberta proposed a complete ban on transitionrelated hormone therapy under the age of 16 and GAS under the age of 18, prompting some fears that Canadian federal lawmakers may follow the antitrans example set by the US and UK in the future.20 Compounded upon existing healthcare barriers and inequities, this legislation further threatens the ability of TGD people to receive gender-affirming care, including GAS.

The inequity and discrimination faced by TGD people reveal a need for improved understanding of TGD patient experiences among medical professionals, a greater effort to promote access to effective interventions like GAS, and a stronger advocacy movement for the rights of TGD people. While GAS may seem like a niche sub-specialty within the medical field, achieving healthcare equity means ensuring that all patients, regardless of their identity or background, can access the medical care they require.

References

1. Oles N, Fontenele R, Abi Zeid Daou M. Transgender History, Part II: A Brief History of Medical and Surgical Gender-Affirming Care. Behav Sci Law. 2025 Jul-Aug;43(4):351-356.

2. Tanenbaum GJ, Holden LR. A Review of Patient Experiences and Provider Education to Improve Transgender Health Inequities in the USA. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Oct 20;20(20):6949.

3. Connolly DJ, Meads C, Wurm A, et al. Transphobia in the United Kingdom: a public health crisis. Int J Equity Health. 2025 May 28;24(1):155.

4. Smallens Y. “They’re Ruining People’s Lives.” Human Rights Watch. 2025.

5. Joseph A, Cliffe C, Hillyard M, et al. Gender identity and the management of the transgender patient: a guide for non-specialists. J R Soc Med. 2017 Apr;110(4):144-152.

6. Atkinson SR, Russell D. Gender dysphoria. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(11):792-6.

7. Arteaga R, Dryden K, Blasdel G. Patient education and surgical decision-making in genital gender-affirming surgery. Curr Opin Urol. 2024 Sep 1;34(5):308-313.

8. Selvaggi G, Salgado CJ, Monstrey S, et al. Gender Affirmation Surgery. Biomed Res Int. 2018 Jul 5;2018:1768414.

9. Zilavy AJ, Santucci RA, Gallegos MA. The History of Gender-Affirming Vaginoplasty Technique. Urology. 2022 Jul;165:366-372.

10. Rocha EAV. Fifty Years of Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Jul-Aug;32(4):II-III.

11. Cooper DKC. Christiaan Barnard-The surgeon who dared: The story of the first human-to-human heart transplant. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2018 Jun 30;2018(2):11.

12. Albana MF, Scuderi GR, Tria Jr AJ. The Evolution of Total Knee Replacements. In: The Cruciate Ligaments in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024. p. 3–15.

13. Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Association Between Gender-Affirming Surgeries and Mental Health Outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2021 Jul 1;156(7):611-618.

14. Park RH, Liu YT, Samuel A, et al. Long-term Outcomes After Gender-Affirming Surgery: 40-Year Follow-up Study. Ann Plast Surg. 2022 Oct 1;89(4):431-436.

15. Ren T, Galenchik-Chan A, Erlichman Z, et al. Prevalence of Regret in Gender-Affirming Surgery: A Systematic Review. Ann Plast Surg. 2024 May 1;92(5):597-602.

16. Bustos VP, Bustos SS, Mascaro A, et al. Regret after Gender-affirmation Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prevalence. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021 Mar 19;9(3):e3477.

17. Hostetter CR, Call J, Gerke DR, et al. “We Are Doing the Absolute Most That We Can, and No One Is Listening”: Barriers and Facilitators to Health Literacy within Transgender and Nonbinary Communities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 22;19(3):1229.

18. Holloway BT, Gerke DR, Call J, et al. “The doctors have more questions for us”: Geographic differences in healthcare access and health literacy among transgender and nonbinary communities. QSW: research and practice. 2023;22(6):1073–91.

19. Taylor T. “The State of Trans Healthcare Laws in 2025.” Advocates for Trans Equality. 2025.

20. Jeffrey A. “Alberta legislation on transgender youth, student pronouns and sex education set to become law.” CBC. 2024.

SeasonalAffective Disorder in the Context of Racialized Individuals

By Vanessa Ip

With the transition to daylight savings at the end of every year, our sunlight exposure becomes limited. The decrease in sunlight, and thus vitamin D exposure, is linked to a decrease in mood. We often hear the terms “depression”, and “seasonal affective disorder” used colloquially, but what do they really entail? Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a clinical subtype of mood disorders with recurrent episodes of major depression occurring in a seasonal pattern,1-3 associated with recurrent depressive episodes in the fall and winter.2 Symptoms may include low mood, fatigue, changes in appetite, and loss of interest or pleasure in activities.2 Although light therapy has gained interest as a novel treatment for SAD, it is not the only option. With approximately 2-3% of Canadians experiencing SAD in their lifetime, and 15% experiencing mild SAD with symptoms of slight depression, it’s timely to bring additional regimens and strategies for equality in treatment availability to light; pun intended.3

SAD has been suggested to have further implications on racialized individuals. Previous research suggests that individuals with darker skin tones are more susceptible to vitamin D deficiencies.4 Furthermore, African Americans have been shown to be more likely to be deficient in vitamin D, as skin pigmentation reduces vitamin D production, and subsequently developing SAD.4,5 Interestingly, even individuals with darker eye colour have been linked

to increased risk for depression and fatigue compared to those with blue eyes.6 However, a common limitation in research investigating SAD is the absence of racialized population samples.7,8 Given that people of colour are at greater risk of SAD, it is important to identify the effectiveness and development of treatments.

Despite these research gaps, various evidence-based treatments for SAD have been identified for the general population and have become more popular and accessible in recent years.9 Similar to treatments for other mood disorders, pharmacotherapy involving second-generation antidepressants (i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) reduces depression scores and remission rates better than placebo.10 Another option is light room therapy (LRT), which is typically done in hospitals where light boxes, meant to mimic natural sunlight with 10,000 lux of white, fluorescent light, are for patients’ personal use.10,11 Although light boxes are easily accessible, there are better results with the use of LRT as opposed to light boxes in patient homes—namely due to exposure and intensity of light. In addition, light therapy requires patients to wake up and spend 30 minutes in the light, requiring behavioural commitment. But between light therapy and pharmacotherapy, which one is better? Surprisingly, some evidence suggests that light therapy may have comparative benefits to pharmaceuticals!1

One double-blind randomized controlled trial found that light therapy was equally as effective as the antidepressant fluoxetine at treating SAD.1 Therefore, the choice between the two options will often depend on personal preference and whether patients would rather adjust their morning routines or commit to taking medication.

Another treatment option involves cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), a psychological intervention targeting maladaptive thinking and behavioural patterns which is well established in mood disorder treatment.12 Several variations of CBT exist, tailored to the unique needs of different mood disorders, with CBT-SAD leveraging psychoeducation, behavioral activation, and cognitive restructuring to specifically target winter depression.13 CBT-SAD has shown to be comparable to light therapy treatment after one year. Whereas light therapy is more accessible and less of a time commitment, CBT had more long-term effects, despite stopping the treatment.13

However, does ethnicity influence the course of SAD presentation and treatment? When looking at research with racialized samples, light treatment has been shown to be equally as effective for treating SAD amongst African-American compared to Caucasian patients.5 In addition, a study looking at hospital admissions for seasonal depression found that those of Asian race had more depressive episodes in the winter. This may be due to the lower

latitudes of where Asians originate, causing them to have more frequent depressive symptoms in response to the harsh weather found in higher latitudes.14

Beyond evidence for differing susceptibility and treatment outcomes for SAD in racialized individuals, existing systemic differences in treatment availability for mental health pose a considerable barrier for people of colour.15 This, coupled with the limited availability and insurance coverage of light boxes, make newer treatment options even less accessible.16 This disparity is further reflected in CBT-SAD treatment. Recent research supports ‘culturally adapted’ CBT as better suited for racialized individuals,17 but the more niche implementation of CBT-SAD risks generalization. Ultimately, novel SAD treatments can only be effective for racialized individuals if existing inequalities in mental health services are addressed concurrently.

The array of treatments for SAD is encouraging, opening more options for patients to explore and tailor their treatment. The current evidence suggests that light therapy and cognitivebehavioural therapy may be most effective for treating winter depression. Given recent evidence, SAD should be treated more seriously among North American people of colour, and that treatment should be consistent and repeated over time, especially in the winter months.

However, further research is necessary to better identify the genetic underpinnings and clinical outcomes of SAD, in concert with addressing systemic limitations to treatment availability. It is through more extensive research that treatments can be tailored to meet the unique needs of each individual, ensuring that no one is left behind when dealing with the cold, dark winter months.

References

1. Lam RW, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, et al. The Can-SAD Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effectiveness of Light Therapy and Fluoxetine in Patients With Winter Seasonal Affective Disorder. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163(5):805–12.

2. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ seasonal-affective-disorder

3. Seasonal affective disorder [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Jul 25]. Available from: https://bc.cmha.ca/documents/seasonal-affective-disorder-2/

4. Stewart AE, Roecklein KA, Tanner S, et al. Possible contributions of skin pigmentation and vitamin D in a polyfactorial model of seasonal affective disorder. Medical hypotheses. 2014;83(5):517–25.

5. Uzoma HN. Light treatment for seasonal Winter depression in African-American vs Caucasian outpatients. World journal of psychiatry. 2015;5(1):138–46.

6. Goel N, Terman M, Terman JS. Depressive symptomatology differentiates subgroups of patients with seasonal affective disorder. Depression and anxiety. 2002;15(1):34–41.

7. Øverland S, Woicik W, Sikora L, et al. Seasonality and symptoms of depression: A systematic review of the literature. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2020;29:e31. doi:10.1017/ S2045796019000209

8. Magnusson A, Partonen T. The Diagnosis, Symptomatology, and Epidemiology of Seasonal Affective Disorder. CNS spectrums. 2005;10(8):625–34.

9. Westrin Å, Lam RW. Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Clinical Update. Annals of clinical psychiatry. 2007;19(4):239–46.

10. Kurlansik SL, Ibay AD. Seasonal Affective Disorder. American family physician. 2012;86(11):1037–41.

11. Terman M, Terman JS. Controlled Trial of Naturalistic Dawn Simulation and Negative Air Ionization for Seasonal Affective Disorder. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2126–33.

12. What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy? [Internet]. American Psychological Association; 2017 [cited 2025 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/ cognitive-behavioral