YOUR ULTIMATE WILD DECEMBER

December 2020 | Vol. 38 No. 13

COULD YOU SPOT 500 SPECIES BY CHRISTMAS?

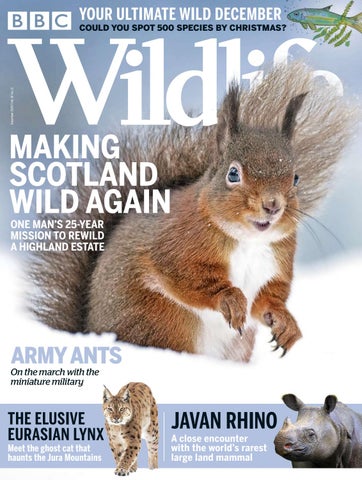

MAKING SCOTLAND WILD AGAIN ONE MAN’S 25-YEAR MISSION TO REWILD A HIGHLAND ESTATE

ARMY ANTS On the march with the miniature military

THE ELUSIVE EURASIAN LYNX Meet the ghost cat that haunts the Jura Mountains

JAVAN RHINO A close encounter with the world’s rarest large land mammal