• Service • Advocacy Quarterly Journal - May 2024

Stakeholder Engagement

Impact

Building Strong Schools with

Do you want to provide immediate support for your staff? Consider leveraging Title II funds to increase awareness, and professional training opportunities for your team, school, or district. Contact us @ ilascd.director@gmail.com D O N ’ T M I S S T H I S O P P O R T U N I T Y G R O U P M E M B E R S H I P R E Q U I R E S A M I N I M U M O F 2 5 P E O P L E W H A T A R E T H E T O P M E M B E R B E N E F I T S ? 5 B O O K A S C D L I B R A R Y ( G O O D F O R O N E S T A F F M E M B E R ) D I S C O U N T O N A S C D B U L K B O O K O R D E R S - A D D B O O K S T O Y O U R I N I T I A L R E G I S T R A T I O N ! $ 4 9 D I S C O U N T O N A N Y I L A S C D C O N F E R E N C E S O R W O R K S H O P S V I R T U A L I L A S C D Q U A R T E R L Y J O U R N A L D E L I V E R E D T O Y O U R M A I L B O X V I R T U A L I L A S C D W E E K L Y E D B R I E F S D E L I V E R E D T O Y O U R M A I L B O X V I R T U A L A C C E S S T O I L A S C D S C H O O L I M P R O V E M E N T D A Y V I D E O S E R I E S Group Membership

size/cost 25 to 100: $500 101 to 500: $2500 1000+: $5,000 Join and Win! Our Membership Form

Group

esengland@umes.edu

When I began in education, I shied away from stakeholder engagement. I fell back on the too many cooks in the kitchen excuse. But two things begin to happen when we do that. First of all, we begin to experience burnout far faster. Second, we begin to grow stagnant—even with our new ideas implemented. And many times it is because we had zero input.

The quarterly theme of this journal is about building stronger schools with stakeholder engagement. We can do that because we have more people becoming invested. And though we are talking about schools (it

3 A Letter from the President Quick Links

Stakeholder Engagement Principles Can Be Applied Everywhere

7 Whole Child 25 Book Review: Personal & Authentic 28 Resource Corner 34 Pump-Up Primary Recap 41 Enhancing Educational Excellence 45 Transforming Early Childhood Environments 57 The Power of Parent Engagement 60 Stakeholder Involvement 66 Upcoming Events

ILASCD Leaders

Scott England, President esengland@umes.edu

Belinda Veillon, Past President bveillon@nsd2.com

Amy Warke, President-elect awarke2008@gmail.com

Doug Wood, Treasurer dawlaw1986@gmail.com

Amy MacCrindle, Secretary amaccrindle@district158.org

Debbie Poffinbarger, Media Director debkpoff@gmail.com

Ryan Nevius, Executive Director rcneviu@me.com

Bill Dodds, Associate Director dwdodds1@me.com

Task Force Leaders:

Membership & Partnerships

Denise Makowski, Andrew Lobdell

Communications & Publications

Amy MacCrindle, Jacquie Duginske

Advocacy & Influence

Richard Lange, Brenda Mendoza

Program Development

Terry Mootz, Sarah Cacciatore, Dee

Ann Schnautz, Doug Wood, Amie Corso

Reed

is an education journal after all), the same can be applied to any scenario.

For my example, I’ll use house cleaning. Because let’s face it, if you’re just one of many in your family with kiddos in sports & multiple activities, house cleaning is often pushed down the to-do list. But what if you got stakeholder engagement from everyone? What if everyone discussed how they could contribute? You might find out that one likes to wash the laundry but hates folding it. Which is great because someone else loves folding. For me, I love cleaning bathrooms and cooking— it should be noted I love to do these separately from each other.

This can all be learned just by engaging the stakeholders of the house. One thing I’ve learned that doesn’t work for my two children (i.e., stakeholders) is exasperation or raising my voice. Neither responds to that. So when the rat’s cage needs to be cleaned, I give them a deadline and let them work it out between themselves with the finer details.

It’s not a far leap from household chores to building stronger schools using the same principles. Look at the numerous referendums and other ballot issues

4 Welcome (cont.)

during this past election. You can’t get stakeholder buy-in if you don’t engage them. I think many classroom teachers will tell you that including parents helps build stronger classrooms. Principals who include teachers and staff in major decisions tend to find transitions to go more smoothly.

We are not in this great profession alone. Simply engaging with one another empowers us to be a little better today than we were yesterday. And that’s ultimately the goal. I hope you enjoy this Spring Journal.

5

GET INVOLVED WITH OUR SOCIAL MEDIA! MORE INFORMATION

Whole Child Recognition Awards

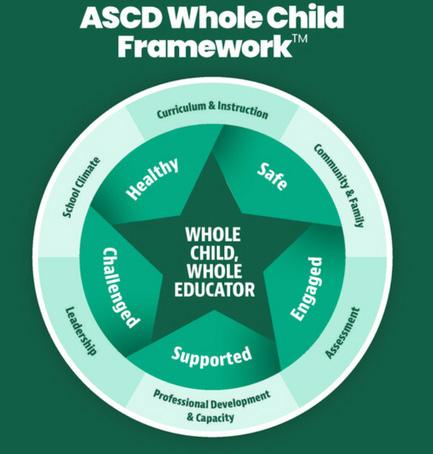

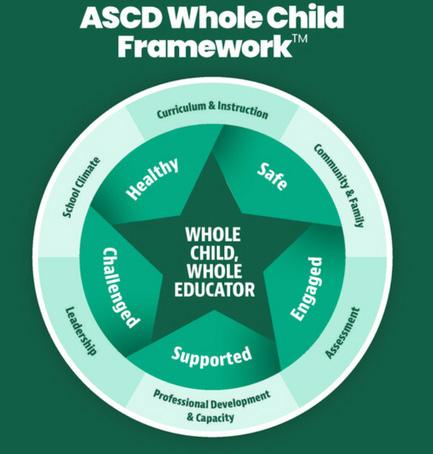

ASCD promotes the Whole Child Tenets to ensure student success in our schools.

Each year, IL ASCD encourages schools and districts to seek recognition for implementing the Whole Child Tenets in their schools.

Submissions may be made in any of the five tenets, Healthy, Safe, Engaged, Supported, & Challenged, or by submitting in all categories for the Overall Recognition.

Click to view the application process.

The 2023-2024 Whole Child Awards Award Applications are being accepted March 18th - May 31st, 2024.

Whole Child

Dr. Jenifer Ericson

Dr. Jenifer Ericson

Preparing All Teacher Educators to Provide an Inclusive and Engaging Classroom Learning Environment

“Inclusion is a philosophy that allows students, families, education, and community members to create schools and other social institutions based on acceptance, belonging, and community” - Battaglia & Brooks, 2019, p. 80

The theme of this journal is “Stronger Schools with Stakeholder Engagement.” As with anything in life, individuals need their attention grabbed to be engaged with what is happening in the moment. This is especially true within schools and classrooms. Students may become easily distracted or lose interest in a topic quickly. Educators have less than thirty-seconds to grab a student’s attention and engage them in the concept they are teaching. According to Trost (2022) “… some students report short breaks in attention as early as 30 seconds into a class period.” In addition to engaging students in their learning, it is equally important to engage

7

their families as well. Communication and collaboration with families allow educators to better support the students in the classroom. In this article, I will discuss how teacher educators can prepare to provide engaging and inclusive classroom learning environments through using the framework of the five Whole Child Tenets.

Whole Child Healthy Tenet: Academic and Social-Emotional Well-Being

How are educators supporting students’ social-emotional well-being as well as their academic ability? Since the pandemic of Covid-19, this core focus on the students is even more essential, especially in ensuring that they are socially-emotionally capable as well as academically capable of functioning in their adult life. The pandemic shifted individuals’ mindsets. Covid-19 heightened the senses of fear and isolation and the coping skills to be a part of society. Teacher educators across the world have been grappling with how to meet the needs of all learners in their classes, including their needs for academic support as well as social-emotional support, providing an inclusive classroom environment with the proper supports put into place through classroom management, collaboration, and knowledge of educational laws we can enhance a

student’s weakness and utilize the student’s strengths to do so. Providing an inclusive classroom environment can be a challenge, especially with the aftereffects of Covid-19. However, providing an inclusive and engaging classroom learning environment is needed for all learners. Ensuring the Whole Child is acknowledged by applying and aligning the Whole Child Tenets of “Healthy, Safe, Engaged, Supported, and Challenged” (ASCD) is the building block for supporting all learners.

Whole Child Supported Tenet: Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

How are teachers going to provide engaging and inclusive classroom environments that support each learners’ individual learning needs? Teacher educators may struggle with knowing how to support their students’ learning needs. Collaboration between the general education teacher and the special education is an effective way to ensure all students are having their academic and social-emotional needs met. This collaboration helps reduce barriers for students in the classroom, “Inclusive education is an approach to education for all that focuses on reducing barriers to participation in education for marginalized individuals and groups” (qtd. in Florian, 2021). When a teacher utilizes supports, strategies, and

8

Whole Child (cont.)

accommodations with a student the prior year, that knowledge could be passed on to the next year's teacher to provide continuous, uninterrupted support for the student. Collaboration also provides the general education teacher

It could be beneficial if teacher preparation programs provided general education pre-service candidates with knowledge of education and special education law.

with support in understanding how to implement a student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP).

It is crucial for all teacher educators to understand what an (IEP) and a 504 Plan are, what the law says about each, and how the teacher educator will use the information given in the plan to implement in their inclusive classroom environment to ensure the students will be provided free appropriate public education (FAPE). It could be beneficial if teacher preparation programs provided general education pre-service candidates with knowledge of education and special education law. This would provide the teacher educator with valuable information that they can then ensure they are not only meeting the needs of the students but also complying with the law. It would also benefit the teacher educator to be taught how to provide and document the accommodations or

modify the curriculum while balancing all their students, creating and delivering instruction. One way this could be accomplished is by utilizing Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and meeting the needs of all the learners in their classroom. Collaboration among the general education teachers and the special education teachers would support the general education teacher in understanding how to implement UDL to support all learners in an inclusive classroom learning environment.

Whole Child Healthy, Safe, Engaged, Supported, and Challenged Tenets: Consistency and Exploring Tech

How does an inclusive learning environment encompass all five of the Whole Child Tenets: “Healthy, Safe, Engaged, Supported, and Challenged” (ASCD, 2023)? One of the potential challenges to teacher educators in providing an inclusive learning environment is classroom management. Classroom management seems to be an ever-existent obstacle for all teacher educators. It does not have to be an obstacle if the teacher educator is provided initial and continual

9

professional development on classroom management strategies,

“During the start of a teacher’s career, there is a collision between idealized notions of what classroom management should be and what classroom management must be due to the realities of teaching” (Gray, 2021, p. 71).

Consistency is the foundational key in each aspect of classroom management:

sense of preparedness and teacher candidates’ concerns because of the impact each has on their future success” (Livers et al., 2021).

Teacher educators require hands-on realworld application to be prepared for the classroom and to manage the behaviors that arise. Books with not only concepts for teacher educators to learn but with templates, examples, and web links that they can use to create instructional lessons and activities are valuable

Calming corners can be created to provide a safe place for students.

(a) Consistency in building relationships with the students; (b) Consistency in engaging the students in learning; (c) Consistency in protocols and procedures of the classroom and school; (d) Consistency in recognizing adherence to the protocols and procedures; (e) Consistency in organizing the learning environment. Research shows that

“Teacher candidates’ sense of preparedness is integral to success as a teacher and longevity in the profession. Beyond preparing teacher candidates with content knowledge and pedagogy, elementary teacher preparation programs must be cognizant of teacher candidates’

resources for teacher educators. It is also essential to expose teacher educators to professional articles and journals to stay up to date with trends and current issues in education teaching and learning. Providing the teacher educators with research-based evidence to support their learning is an integral part of teacher educator preparedness which leads to effectively managing their classrooms.

To help manage the classroom, teacher educators can create a consistent inviting, calming, and positive atmosphere by utilizing positive behavioral supports and interventions, such as stickers, fidget modalities, coloring activities, crossword puzzle

10

Whole Child (cont.)

pages, and/or word search puzzle pages. Calming corners can be created to provide a safe place for students. Flexible seating of pillows, rug squares, and/or balance ball chairs, can also be included in the calming corner. By creating a calmer corner teacher educators can relocate a student that may be presenting disruptive behaviors and provide strategies and support to them away from the whole class.

Creating a schedule A, B, and C will also provide the teacher educator with options to keep the whole class on task while they work with the students on their behavior. Positive redirection will also support the teacher educator in providing a calming and inviting classroom. For example, before having the students line up the teacher educator can use phrases including: “Before we line up, I would like to thank you for lining up quietly and walking on the blue line to the library today.” When the students arrive at their location give each a fist bump or high five as they walk into the location quietly and when they sit down comment to the whole class, “I appreciate how you followed directions walking quietly and on the blue line to get here. Enjoy paying attention to the librarian’s storytelling this morning.

I will see you in 45 minutes.” These examples are a few of many ways teacher educators may provide an engaging and

inclusive classroom environment using classroom management strategies.

How can utilizing interactive technology tools in the classroom allow a teacher educator to engage the students in the instruction and formatively and summatively assess their students’ knowledge and understanding of concepts? Engaging students is one of the foundational steps in effectively managing your classroom. Technology tools can make a teacher educator’s life a lot easier and help them engage students in their classroom. According to Jotform (2019):

…classroom technology often comes at a price that’s simply too high for teachers. Many teachers already have to spend their own money just to keep the necessities in the classroom, and paid software doesn’t always fall high on that list.

It is necessary to prepare teacher educators on how to find free or lowcost interactive technology tools to assist them in creating an inclusive and engaging learning environment. (See Table 1 on the following page.)

Utilizing technology tools in the classroom will provide support to the teacher educators in providing an inclusive and engaging classroom for all learners. Finding technology tools that

11

Table 1

Low-Cost Interactive Tech Tools for the Classroom

Tech Tool

Read Theory

Pear Deck

Remind

Google Forms

Edpuzzle

Quizlet

Blooket

Spelling City.

IXL

Purpose

● Online individualized reading comprehension improvement program

● Students take a pretest that assesses individualized reading grade and Lexile levels

● The program selects passages at that reading grade level for each student

● If a student chooses the incorrect answer the program provides the student with an explanation and reading strategy

● Provides progress monitoring data in curriculum standards: Craft and Structure, Integration of Knowledge, and Key Ideas and Details

● Interactive learning tool

● Allows the teacher to insert multiple styles of response slides for students to respond on the PowerPoint presentation

● Provides immediate feedback in the form of a copy of the slides and their responses at the end of the lesson

● School to home communication center

● Parents can interact with the student’s teacher Parents can receive communication on grades, assignments, and announcements

● Interactive learning tool

● Formatively and summatively assess students

● provides immediate feedback

● Interactive learning platform

● Educators can create videos and insert questions throughout the video

● Educators assign lessons to students for review, learning virtually, or were absent from school that day

● Interactive learning platform

● Educators and students create and review concepts

● Educators can create a class Quizlet and monitor students’ progress in reviewing the concepts

● Interactive game-based learning platform

● Educators create an interactive game to review concepts

● Interactive game-based program

● Educators create individualized spelling practices that can be completed in school and at home

● Interactive online practice and progress monitoring program

● Aligns practice to educational standards

● Educators assign the whole class or an individual student a concept to review and practice

12

Utilizing technology tools in the classroom will provide support to the teacher educators in providing an

Whole Child (cont.)

are appropriate and cost effective can be a challenge for teacher educators, especially with limited funding. It is beneficial to provide teacher educators with the knowledge to find appropriate and cost-effective resources that are free or low cost to use the basic programming.

Whole Child Safe Tenet: Collaboration

How can a teacher create a collaborative and supportive working environment for their entire team? In addition to building relationships with students, building relationships with colleagues through collaboration is crucial to teacher educators being able to provide an inclusive classroom environment. However, collaboration may be a challenge for teacher educators. Collaborating with paraeducators is vital to managing a classroom, and providing appropriate instruction, and instructional support to the students. Not only do students need to feel included and have a safe place, but so do the faculty and staff, “Paraeducators play a crucial role in providing services to students with disabilities” Gentile, Zagata, & Sinclair, 2023, p. 168). Every day the classroom teacher has the responsibility to create and share a daily to-do list for the next day of what each person in the classroom is doing, which student they are working with, any supports they are putting into place, any data that needs to be collected.

While paraeducators and special educators are expected to collaborate to meet the needs of their students, they do encounter challenges in their respective roles and the way they function as a team. Issues related to training, communication, scheduling, and managing caseloads often must be addressed to ensure a successful professional relationship between both parties (Gentile, Zagata, & Sinclair, 2023, p. 168).

The teacher educator is the certified personnel with the training and background to create, deliver, and assess the instruction. This educational background and knowledge are used to guide the paraeducator in supporting the teacher educator and the students daily in providing an inclusive classroom learning environment.

For example, having set times to collaborate between the teacher and paraeducators would support open communication. Providing each team member with an agenda list of items that need to be discussed and actions taken to improve would support all team members. Providing the team members with pre-made data sheets and clipboards to document student behaviors and progress monitor students’ IEP goals. Then, in the weekly meeting,

13

—discussing what triggering language or actions bothers each person on the team helps to keep an open healthy line of communication open to collaboratively support the students.

each team member discusses strategies, supports, and/or accommodations that provided the student with positive support, as well as discusses what may have not worked with the student.

Collaboration on the above items requires the team to have an open communication dialogue. It is essential to set ground rules amongst the team at the beginning of the year regarding how things will be addressed if an issue arises—discussing what triggering language or actions bothers each person on the team helps to keep an open healthy line of communication open to collaboratively support the students. The use of a shared drive with a Google Doc or Google Sheet where each team member can create a list of questions, ideas, or supports they have used in the classroom would be beneficial in supporting open communication. This open communication would provide the team members with a healthy, safe working environment to express their needs to support the student’s needs.

As well as collaborating with paraeducators, collaborating with coteachers ensures an effective working relationship and appropriately supporting the students. As quoted in Battaglia and Brooks (2019):

“The ideal co-teaching scenario is where both teachers share instruction and assessment equally and can use advanced co-teaching strategies to provide intervention, enrichment, pre-teaching, and reteaching through flexible grouping.”

It is vital that before a teacher educator co-teaches, they need to get to know their co-teacher and discuss what coteaching style will benefit that class the most. Key questions to ask each other: (a) What is the general education teacher’s expectation of the special education teacher during that co-taught class? (b) What content knowledge does the special education have about that subject? (c) Is the special education teacher comfortable teaching that content’s concepts? (d) How will the

14

Whole Child (cont.)

co-teachers set up weekly collaboration time dedicated to creating the coteaching model, instruction, instructional activities, and assessments? The answers to these questions will affect the style of co-teaching they will choose.

In a co-teaching classroom, “The goal is to establish collaborative, supportive, and nurturing communities of learners by giving all students the services and accommodations they need to learn and respecting and learning from each other’s differences” (Battaglia & Brooks, 2019). Universal Design for Learning may be utilized to promote an inclusive coteaching classroom. Jung (2021) reports that

“UDL offers guidelines on how we can make our instruction and classroom environments welcoming, responsive, supportive, and flexible so that the fewest students possible require additional support or adaptations” (para. 7).

There is so much more to co-teaching than just knowing the name and definition of the co-teaching styles. As research exemplifies,

“Deliberate planning on the part of the general education teacher in collaboration with the special education teacher allows for

a successful implementation of inclusion for students with disabilities, regardless of the severity of the disability” (WombleEricson, 2022, p. 41).

The teacher educator needs to be prepared in the beginning of the collaboration process to carry out the co-teaching process from start to finish to support an inclusive and engaging classroom learning environment.

Whole Child Engaged and Challenged Tenets: 21st Century Skills

How can teacher educators be prepared for being possibly the only teacher in that classroom managing all learners and their needs? Students need teacher educators to engage and challenge them in their learning. Research supports that “Today’s youth face a rapidly changing world, requiring them to move beyond basic formulaic knowledge and skills. Current educational policy, such as the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), represents a shift away from rote learning and memorization of facts to the development of the 21st-century skills of creativity: critical thinking; communication; collaboration; and information, media, and technology skills (IMTS)” (Urbani, Roshandel, & Truesdell, 2017, p. 27). The world of teacher preparation is ever changing as our society evolves. Students are no longer

15

being only taught how to memorize a fact sheet instead. The teacher educator must prepare the students to be able to critically think and learn the foundational “why” of a concept and the real-world use of the knowledge. For teacher educators to prepare the students to be able to critically think and learn the foundational “why” of a concept and the real-world use of the knowledge they need the tools to be able to plan their instruction and instructional activities.

Preparing Teacher Educators: What’s next?

This leads us to what’s next. How do we prepare teacher educators to support students in becoming critical thinkers but also support their academic and social-emotional well-being? Who will be responsible for educating the teachers? How will teacher preparation programs adjust, modify, accommodate, and support teacher educators themselves to be critical thinkers, innovative, and engaging in an inclusive classroom learning environment? How will schools support teacher educators with continuing education in professional development? We can begin to plan out the responses to these questions by focusing on the Whole Child Tenets of “Healthy, Safe, Engaged, Supported, and Challenged” (ASCD). These tenets provide the foundation for teacher educators to create inclusive

and engaging classroom environments for all learners. It is not an easy task but implementing these tenets with fidelity and consistency allows teacher educators to build relationships with students, and engage the students in motivating and enriching instruction, which should result in an effective inclusive classroom learning environment for the students and the teacher educators.

References

Battaglia, E., & Brooks, K. (2019). Strategies for co-teaching and teacher collaborations. Science Scope, 43(2), 80–83. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/26899069

Florian, L. (2021). The universal value of teacher education for inclusive education. In A. Köpfer, J. J. W. Powell, & R. Zahnd (Eds.), Handbuch Inklusion international / International Handbook of Inclusive Education: Globale, nationale und lokale Perspektiven auf Inklusive Bildung / Global, National and Local Perspectives (1st ed., pp. 89–106). Verlag Barbara Budrich. https://doi. org/10.2307/j.ctv1f70kvj.8

Gentile, M. G., Zagata, E., & Sinclair, T. E. (2023). Challenges in paraeducator supervision. In J. DeSimone & L.

16

Whole Child (cont.)

Roberts (Eds.), Cases on Leadership Dilemmas in Special Education (pp. 168-179). IGI Global. https://doi. org/10.4018/978-1-6684-8499-9. ch013

Gray, P. L. (2021). Mentoring firstyear teachers’ implementation of restorative practices. Teacher Education Quarterly, 48(1), 57–78. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/27094716

Jotform. (2019, March 15). 13 tech tools for teachers on a tight budget: The path to paperless. The Jotform Blog. https://www.jotform.com/blog/13tech-tools-for-teachers/

Jung, L. (2021). Lesson planning with universal design for learning. ASCD, 78(9). https://www.ascd.org/el/ articles/lesson-planning-withuniversal-design-for-learning

Livers, S. D., Zhang, S., Davis, T. R., Bolyard, C. S., Daley, S. H., & Sydnor, J. (2021). Examining teacher preparation programs’ influence on elementary teacher candidates’ sense of preparedness. Teacher Education Quarterly, 48(3), 29–52. https://www. jstor.org/stable/27094741

ASCD. The whole child approach to education. (2023, April 13). ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/whole-child

Trost, J. (2022, November 1).

Maintaining student attention in the classroom. Notre Dame Learning. https://learning.nd.edu/stories/ maintaining-student-attention-inthe-classroom/

Urbani, J. M., Roshandel, S., Michaels, R., & Truesdell, E. (2017). Developing and modeling 21st-century skills with preservice teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 44(4), 27–50. https://www. jstor.org/stable/90014088

Womble-Ericson, J. R. (2022). Preparing and sustaining general education high school teachers to provide inclusive classrooms: A qualitative collective case study of teachers’ perceptions [Doctoral dissertation]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Dr. Jenifer Ericson has for the past sixteen years, been a leader in the field of special education with various experiences in public and private Catholic schools. Dr. Ericson is a member of the National Association of Special Education Teachers (NASET) Advisory Council for Board Certification Programs. Additionally, she is a Read Theory Certified Educator and a Pear Deck 23-24 Ins’pear’ational Educator. Contact her at drjenericson@gmail.com

17

Whole Child

Preventing Compassion Fatigue in Special Education

Paraprofessionals: Considering the ‘Supported’ Whole Child Tenet

Introduction

Paraprofessionals continue to express feelings of isolation and disrespect, fueled by low compensation and the fact that too many of them continue to be asked to assume teacher duties without adequate preparation, training, direction, or supervision (Giangreco. al, 2010, Wallin, 2024). There is a need for more information on how to address compassion fatigue within particular special educational contexts such as paraprofessionals who work with students who have autism and intellectual disability (Ziaian-Ghafari & Berg, 2019). Paraprofessionals are an essential part of the classroom, providing support for students and helping special educators do their jobs successfully. This article will highlight the key findings of the study “Exploring Special Education Paraprofessional Stress and Resilience”, that focused on fostering paraprofessional self-advocacy and exploring paraprofessional stress through a compassion fatigue conceptual framework. Additionally, practitioners will be provided with reflective questions that focus

18

Dr. Samantha Wallin

on how to promote paraprofessional retention through improved professional development and collaborative relationships.

Strong Leadership and Paraprofessional Stress Reduction

Paraprofessional participants in Wallin’s (2024) study talked about the significance of their working relationships with teachers, as well as feeling valued by school leaders, to feel less emotional exhaustion during the school day. Consider that it is crucial for paraprofessionals to have ongoing

quality of services students with severe disabilities receive may depend on having a positive dynamic between special educators and paraprofessionals (Biggs et. al, 2018). Paraprofessionals also mentioned that having constructive and open communication with the teacher is pivotal to helping reduce their studentrelated stress (Wallin, 2024). Having a positive attitude, supporting each other, and offering ongoing assistance, can help special educators and paraprofessionals make stress more manageable within their classroom team.

The quality of services students with severe disabilities receive may depend on having a positive dynamic between special educators and paraprofessionals (Biggs et. al, 2018).

opportunities to collaborate and have a professional dialogue with their teachers and administrators. Previous research aligns with this notion, that paraprofessionals feel a sense of commitment to their jobs in classroom environments characterized by respect and collaborative work (Barnes et. al, 2021). Most importantly, when paraprofessionals feel that they can trust and rely on their classroom teacher, supervisor, and/or administrative leader, then they feel less stressed and their work with students can improve. The

Collaborative Teams and Paraprofessional Resilience

Paraprofessional participants in Wallin’s (2024) study expressed how important it is for them to feel like a valuable team member, who has fundamental input to give regarding practices implemented with students. Being able to give ongoing feedback and reflect on strategies being used with students is a critical part of paraprofessional participation in a collaborative classroom team. Considering the supported whole child tenet, it is important to note that

19

paraprofessionals are only able to be effective in adequately supporting their students when they feel respected and useful in the classroom. Additionally,

Contextual challenges may include interpersonal ones, such as difficulties in relationships with students, parents, or colleagues (Hascher et. al, 2021).

Research of professional development indicates that PLCs help school communities move from individual professionalism to collective professionalism and facilitate practitioners to work interdependently rather than independently; the professional collaboration, collegiality, and expanded professional roles improve collective teacher and paraprofessional efficacy (Tam, 2014).

paraprofessionals are interested in growing in their role by participating in peer support groups with fellow paraprofessionals and teachers (Wallin, 2024). Professional peer support groups are an effective strategy to combat compassion stress in helping professions. Schools should replicate the practice of professional peer support groups, creating a regular space where teachers and paraprofessionals can come together to check in with each other about how they are doing emotionally (Lander, 2018). The ability for paraprofessionals to feel resilient and self-confident hinges on the working relationships they have and how they can cope with challenges that arise in daily social interactions.

Professional Development and Paraprofessional Stress and Resilience

Importantly, paraprofessional responses in Wallin’s (2024) study indicate a strong need for current professional development practices and expectations to be reassessed by school leaders. Without using the terminology “professional learning communities”, many paraprofessionals spoke about how being a part of a collaborative team that reinforces ongoing feedback and active learning helps them to feel less stressed and more confident when student and workload struggles come up (Wallin, 2024). PLCs need to be implemented as opportunities for personal and professional growth and communitybuilding amongst paraprofessionals and

20

Whole Child (cont.)

teachers. These professionals can be part of a stronger support system for students when they are in a collaborative relationship that emphasizes professional growth and utilizing evidence-based practices together. Research of professional development indicates that PLCs help school communities move from individual professionalism to collective professionalism and facilitate practitioners to work interdependently rather than independently; the professional collaboration, collegiality, and expanded professional roles improve collective teacher and paraprofessional efficacy (Tam, 2014).

Another crucial element to successful paraprofessional training is that it should be done in informal ways, and focus on coaching, feedback, and communication, to ensure the relevance and application of these skills (Wallin, 2024). It is imperative that training is connected to paraprofessional needs, along with their students’ needs. When teachers informally monitor paraprofessionals and their application of strategies, as well as collaborate with them on behavior support practices, then paraprofessional compassion stress can be lessened (Wallin, 2024). Additionally, informal training in the classroom setting may lead to increased administrator buy-in with supporting the implementation and assessment of

these types of PD. A critical element to the success of informal training is that teachers and paraprofessionals have time to reflect on their practices and to give each other feedback. There needs to be an opportunity for professional dialogue that includes a reflection of role expectations, and on the specific expectations for paraprofessionals, especially if they are given the responsibility to implement a new strategy or task with a student (Wallin, 2024).

Looking Ahead- Future Research

There are several directions for future research that can be taken to develop the findings and address the gaps from Wallin’s (2024) study. Figley (2002) notably pointed out two central questions that can be posed in future studies and are relevant to this research: Who is most vulnerable to compassion fatigue in what type of work setting and under what types of conditions? Future studies should also focus on investigating the relationships between paraprofessionals and special educators to better understand how their communication and dynamics are impacting their stress and resilience levels. Wallin’s (2024) study has shown the significance of the paraprofessional and teacher relationship, and it would be important to learn more about how increased collaborative time and mentoring can support these

21

professionals, along with their students, in the face of various immediate and long-term challenges.

It is abundantly clear that paraprofessionals need to have more opportunities to engage in PLCs that focus on shared values and vision, collective responsibility, reflective professional inquiry, and teacher and paraprofessional collaboration (Wallin, 2024). The promotion of group and individual knowledge is a powerful route to large scale change that can potentially help strengthen or even alter social growth (Mullen & Hutinger, 2008). Paraprofessionals are vital members of classroom teams; these professionals need to be part of a collaborative community that values respect and ongoing learning, to ensure that they stay in their positions and continue to positively support the students they work with.

Below are some key questions that school leaders should ask themselves to aid their efforts in supporting their special education paraprofessionals:

• What professional development do we offer our staff and do the paraprofessionals find training to be relevant, connected to their students’ needs, and applicable to daily work tasks?

• How are the working relationships between paraprofessionals and teachers, and how can school leaders

increase opportunities for collaboration and coaching between these professionals?

• Do our paraprofessionals have opportunities to be part of a professional learning community; if not, how can we create more opportunities for these types of professional learning spaces for paraprofessionals?

References

Barnes, T. N., Cipriano, C., & Xia, Y. (2021). Cultivating effective teacher–paraprofessional collaboration in the self-contained classroom. Beyond Behavior, 107429562110218. https://doi. org/10.1177/10742956211021858

Biggs, E. E., Gilson, C. B., & Carter, E. W. (2018). “Developing that balance”: Preparing and supporting special education teachers to work with paraprofessionals. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 42(2), 117–131. https://doi. org/10.1177/0888406418765611

Figley, C. R. (2002). Treating compassion fatigue. Brunner-Routledge.

22

Whole Child (cont.)

Giangreco, M. F., Suter, J. C., & Doyle, M. B. (2010). Paraprofessionals in inclusive schools: A review of recent research. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 20(1), 41–57. https://doi. org/10.1080/10474410903535356

Hascher, T., Beltman, S., & Mansfield, C. (2021). Teacher wellbeing and resilience: Towards an integrative model. Educational Research, 63(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013 1881.2021.1980416

Lander, J. (2018). Helping teachers manage the weight of trauma: Understanding and mitigating the effects of secondary traumatic stress for educators. Usable Knowledge: Relevant Research for Today’s Educators. https://www.gse.harvard. edu/news/uk/18/09/helpingteachers-manage-weight-trauma

Mullen, C., & Hutinger, J. (2008). The principal’s role in fostering collaborative learning communities through faculty study group development. Theory into Practice, 47. https://doi. org/10.1080/00405840802329136

Tam, A. C. F. (2014). The role of a professional learning community in teacher change: A perspective from

beliefs and practices. Teachers and Teaching, 21(1), 22–43. https://doi.or g/10.1080/13540602.2014.928122

Wallin, S. (2024). Exploring paraprofessional stress and resilience [Doctoral dissertation, Concordia University of Chicago]. ProQuest.

Ziaian-Ghafari, N., & Berg, D. (2019). Compassion fatigue: The experiences of teachers working with students with exceptionalities. Exceptionality Education International, 29(1), 32–53. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei. v29i1.7778

Dr. Samantha Wallin earned her doctorate in Special Education Leadership from Concordia University of Chicago. As a researcher, Samantha is interested in learning more about traumainformed practices, culturally responsive teaching, family communication, and paraprofessional and special educator stress and resilience. She is an academic support specialist for students with lowincidence disabilities and a teacher of adult learners, focused on developing safe spaces for reflection and active learning. Swallin@camphillschool.org

23

TARGETING:

LOCAL ASSESSMENT

An On-Line Video Series for Teachers and Administrators

Not webinars, but live-capture presentations defining “what is testing in standards-based learning environments leading to successful growth model attainment.”

These video tools will help to explain formative and summative assessment techniques so that teachers, and those evaluating them, can speak the same language and work together for student success.

Each Video will:

Deliver definitions of tests

Explore detailed information about their impact on the learning in classrooms

Allow break times for discussion by the viewing group under the leadership of the local host (principal, professor, department chair, PLC leader.)

TEACHER, PRINCIPAL, ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENT, CREATOR OF COURSEMASON & STAFF DEVELOPER

ON-Demand PD REady for you today!

For All 8 Sessions

LOCAL ASSESSMENT: OVERVIEW

LOCAL ASSESSMENT: CRITICAL TERMS & CONCEPTS

LOCAL ASSESSMENT: STANDARDS & EVIDENCE

LOCAL ASSESSMENT: SELECTED RESPONSE

LOCAL ASSESSMENT: CONSTRUCTIVE RESPONSE

LOCAL ASSESSMENT: FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT

01

LOCAL ASSESSMENT: PERFORMANCE TASKS

An ISBE and CPS Approved Provider

LOCAL ASSESSMENT: COMMON ASSESSMENT REVIEW

Eight - 45 TO 60 MINUTE SESSIONS

24

PRESENTED BY: STEVE OERTLE,

CLASSROOM $99

TO PURCHASE - EMAIL DWDODDS1@ME.COM

Book Review

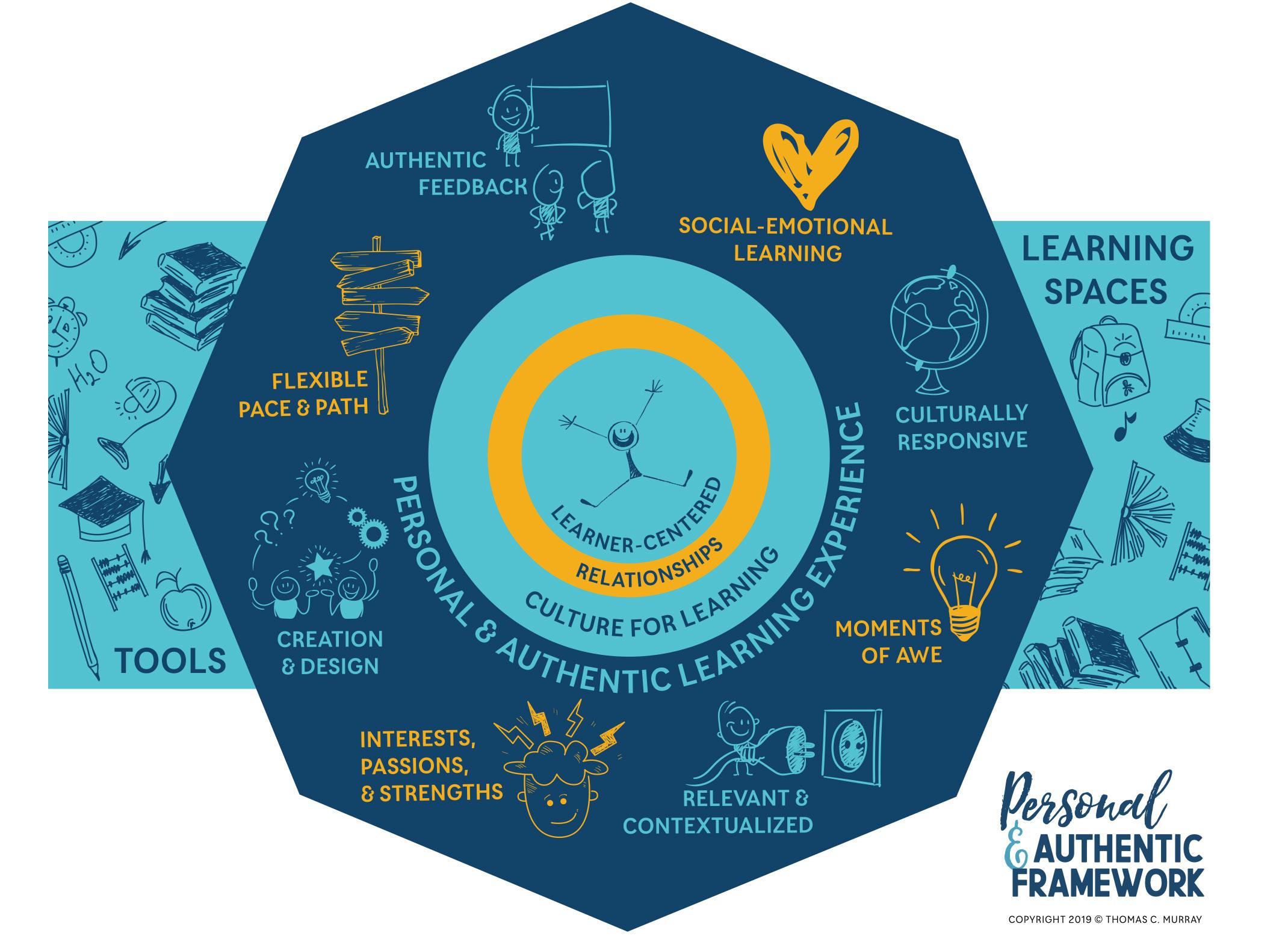

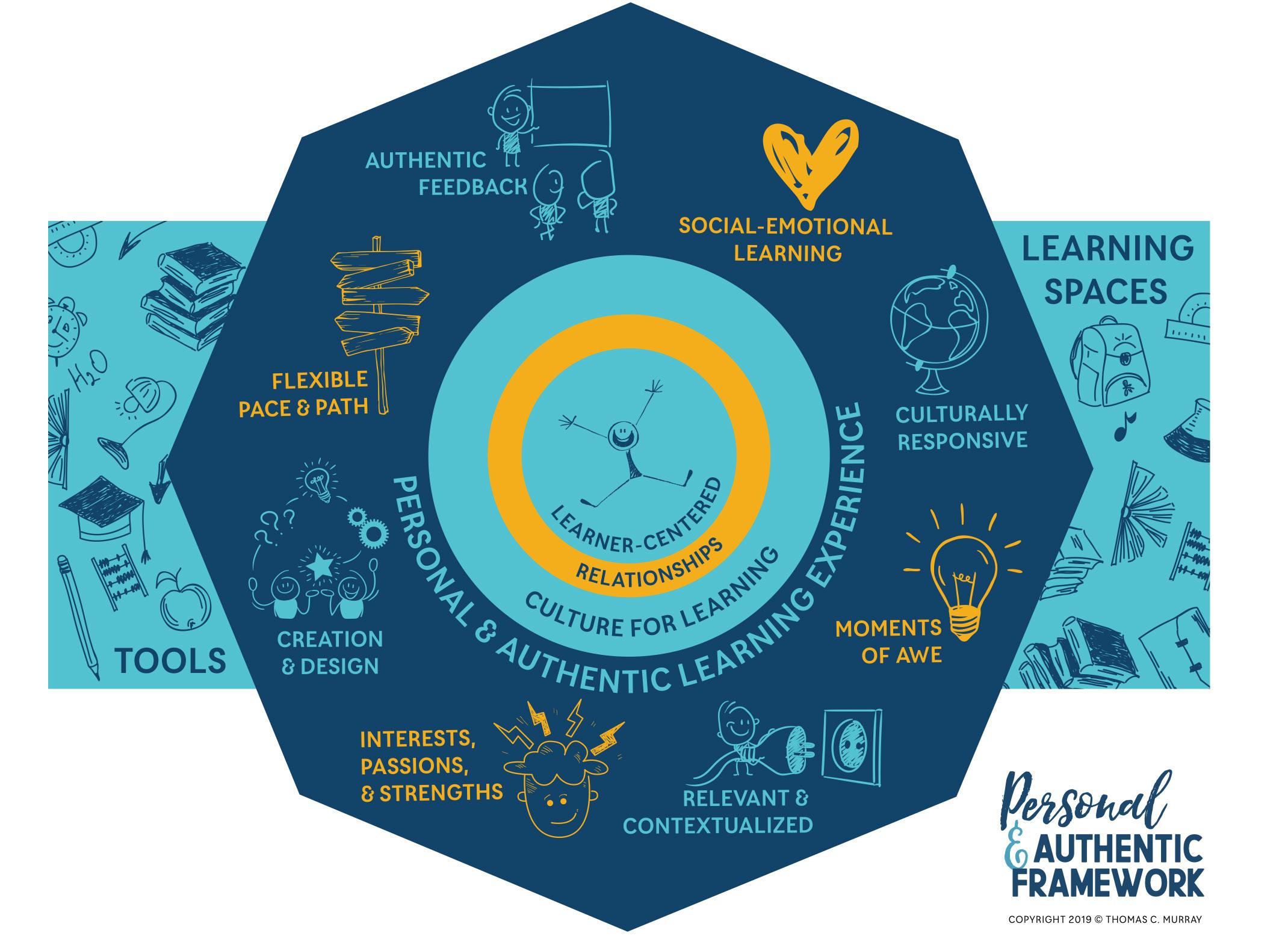

The author begins with a framework for personal and authentic work that to reflect, and to recognize with awe the work that educators do every day, with all children who enter our schools. Murray

25

suggests that we start with the heart so that we see the beauty and potential within each child.

The book is structured to support learning and reflection. There are “Stop and Reflect” entries that solicit the reader to pause and consider their own connection to the content. There are also “Try This” activities that provide options and opportunities for the application of what has been shared. The “Try This” activities are no-cost, encouraging suggestions that will support the creation of a more positive classroom, school climate, and district community. The book also has a modern viewpoint of working with children who have experienced trauma and has a culturally responsive approach. Within each chapter, there are stories, photos, and images that illustrate the chapter’s

26

Book Review (cont.)

message. At the end of each chapter, there is a link to additional free resources and tools related to the content. This text is a perfect selection for a book study for a collaborative team, leadership team, or professional development group. If you are looking for a “feel good” title that will help you reflect and rejuvenate this summer consider adding this text to your shopping cart: Personal & Authentic: Designing learning experiences that impact a lifetime, by Thomas C. Murray.

Dr. Elizabeth Freeman is the Chief Academic Officer at District 300. Liz Freeman has been a middle school and high school classroom teacher, curriculum director, director of professional development, and assistant superintendent and is a frequent presenter at workshops and conferences. Freeman has a focus on Professional Learning Communities and transforming student experiences through innovative and high-impact, modern instructional approaches. Freeman has a Master’s degree in Curriculum and Instruction from National Louis University and a Doctorate in Curriculum, Instruction, and Educational Psychology from Loyola University Chicago.

27

Resource Corner

BUILDING AND SUSTAINING TEACHER ENGAGEMENT

When educators are fully engaged, they perform better and their students learn more.. READ MORE...

PRIORITIZING TEACHERS' GROWTH AND PASSIONS: CREATING A SUSTAINABLE AND ENGAGED TEACHING TEAM

The success of schools and districts depends on designing successful, meaningful, and innovative professional development experiences that ignite teachers' passion for continuous improvement. READ MORE...

FIVE TEACHER ENGAGEMENT STRATEGIES TO FOSTER A COLLABORATIVE CULTURE

Increased teacher engagement promotes positive outcomes for all. Use these strategies to promote collective teacher efficacy and a collaborative culture. READ MORE...

28

WHY FAMILY ENGAGEMENT MATTERS

Research shows that a stronger connection between home and school means better outcomes for students.

READ MORE...

PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT IN YOUR CHILD’S EDUCATION

Over the past three years, we at NAFSCE, have been on a journey to uncover and understand the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that familyfacing professionals bring to forming strong family, school, and community partnerships. We are bringing what we have learned together into the Family Engagement Core Competencies: A Body of Knowledge, Skills, and Dispositions for Family-Facing Professionals (Family Engagement Core Competencies). READ MORE...

A Walk Through The Family Engagement Core Competencies WATCH THE VIDEO...

30

Resource Corner (cont.)

Click HERE to browse through the Niki Spears video blog!

Niki Spears returns in this follow-up book to The Beauty Underneath the Struggle with this powerful book about shifting positive culture, community, and life for the better VIEW ON AMAZON...

31

Click HERE to browse the videos!

THE CASE FOR STRONG FAMILY AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IN SCHOOLS

A roundup of the latest K–12 research reveals persuasive evidence.

32 Resource Corner (cont.)

READ MORE...

Listen to the Podcasts!

EVERYONE WINS! THE EVIDENCE FOR FAMILYSCHOOL PARTNERSHIPS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE | BOOK TALK

Harvard Graduate School of Education presents authors Karen Mapp & Stephany Cuevas CLICK THE COVER TO PURCHASE THE BOOK... WATCH THE VIDEO...

33

Pumped Up and Ready to Grow: A Recap of the Transformative Pump-Up Primary Conference

The atmosphere was electric, and the energy was high, as educators gathered at the 43rd Annual Pre-K, Kindergarten, and 1st Grade Conference hosted by IL ASCD. It wasn't just another conference; it was a transformative experience that left attendees inspired and empowered to revolutionize their teaching as well as their thinking about this complicated profession.

An insightful reflection on navigating our post-COVID educational landscape took place. In a world filled with challenges, I urged educators to reassess their perspectives, emphasizing the power of focusing on the positive as a force for driving meaningful change.

The concept of an "energy map," was presented and provides educators a powerful tool for understanding and elevating one's energy levels. From the depths of helplessness and tension to the heights of ownership, servant leadership, and love, I did my best to light a path towards greater fulfillment and joy in not only teaching but also in life.

34 Article

Niki Spears, Keynote Speaker

Many times, our life lessons offer great learning about ourselves and others which will spill over into the relationships we have with our colleagues, students, and families we serve. The essence of ownership seemed to resonate with the audience as they began to think about ways to elevate their energy during challenging times. It's easy to succumb to negativity, blaming external factors for our circumstances. But true power comes from taking responsibility for our thoughts, actions, and outcomes.

The room buzzed with enthusiasm as educators embraced this mindset shift recognizing that each day presents an opportunity to craft their narrative, to fill the pages of their stories with positivity as they remember their Connection Moment, those instances in life when your passion and purpose collide to reveal your purpose. The choice was clear: dwell on the negative or embrace the boundless potential of each moment.

What emerged was a collective sense of empowerment and fellowship. This conference brings educators together so that they realize they are not alone on this journey; they are part of a vibrant community committed to uplifting each other as well as their students. The conference wasn't just about acquiring knowledge; it was about igniting a passion for positive change.

As my keynote concluded, the energy lingered, a testament to the transformative power of collective inspiration. Many left that morning with renewed vigor, telling me how eager they were to implement their newfound insights in their classrooms and beyond.

In the end, the Pump-Up Primary Conference wasn't just amazing; it was a springboard to profound personal and professional growth. It reminded us that, amid the challenges, there's immense potential for progress. And as we embark on this journey together, let's continue to write our beautiful stories with passion, purpose, and unwavering positivity. After all, the pages of our lives are ours to fill – let's make them extraordinary. Yes! Yes! Yes!

In 2016, when founding Culture Cre8ion, Niki Spears marked a turning point that propelled her into a world of positive transformation. Today, her focus is on presenting powerful messages and creating unique programs for schools, districts, and organizations that elevate personal energy, inspire a shift in mindset and drive the transformation of culture. Every speech, every word, and every interaction is dedicated to creating a positive impact.

35

Pump Up Primary recap (cont.)

Ryan Nevius, Illinois ASCD Executive Director

Ryan Nevius, Illinois ASCD Executive Director

Pumped Up and Ready to Grow: A Recap of the Transformative Pump-Up Primary Conference

Most people associate the start of spring with flowers blooming, longer days, school break and maybe the first cookout of the year. At Illinois ASCD the start of early spring is always marked by our largest event of the year. The ILASCD Pre-K, Kindergarten, and 1st Grade Conference, now called Pump Up Primary, is cornerstone event for teachers and administrators dedicated to early childhood education.

For over 43 years this Conference has provided a platform for collaboration, learning and professional growth. The 2024 Conference has been no exception. Nearly 1800 educators left the Schaumburg Convention Center feeling more connected, inspired and recharged. Most important, they left with a backpack full of new ideas to try in the classroom.

The 225+ diverse sessions from 125+ national and local expert presenters offered a wide array of topics such as literacy, play based learning, SEL, classroom management, centers, calendar time, differentiated instruction and so much more! All sessions were

38 Pump Up Primary recap (cont.)

designed to address the ever-changing needs and challenges faced by teachers working in 2024. All Pump-Up Primary speakers are renowned experts with experience sharing evidence-based practices and innovative strategies paired with practical application!

Another great resource at the Conference was the sold-out Expo Hall. Over 75 companies showcased the latest resources, books, materials and technology relevant to the classroom. Attendees had the opportunity to shop for products in the morning 60 minutes before the start of the show, during passing times, over lunch and for 30 minutes after the last session ended. Applications for the 2025 Conference are scheduled to open in July.

The entire two-day experience was enhanced by the newly renovated Schaumburg Convention Center and Hotel. The venue is conveniently located 20 minutes from O’Hare Airport and less than 2 miles away from several major highways. The Schaumburg area itself offerd lots of excitement after the final session ended. Within a 5-minute drive is IKEA, the Streets of Woodfield Mall, Top Golf and many other shopping opportunities. There is no shortage of great food available at the venue. Conference goers had a plethora of lunch options including Burritos, sandwiches,

salads, burgers, crab cakes, soups and just about anything else imageable.

An event of this size and scale is not an easy undertaking. I would like to thank the Illinois ASCD Staff and Planning Committee for their tireless work over the past 12 months. Beyond the tangible outcomes, it was the spirit of collaboration that truly made the conference special. Their dedication created an inclusive and welcoming environment for educators to come together.

If you haven’t already, consider saving the date for next year’s show on March 6-7, 2025! While it can be difficult to leave your classroom, I truly believe this event can take your teaching and student outcomes to the next level. None of us can get better and gain new perspectives while at home. Thank you for reading and we hope to see you next March 6-7, 2025!

39

FOR EDUCATORS AND SCHOOL PROFESSIONALS

North Central offers a variety of online degrees, certificates, and endorsement programs to help you elevate your skillset and make an impact in your school.

» Master of Education in Educational Leadership with Eligibility for Principal Endorsement

» Master of Arts in Trauma-Informed Practice

» Trauma-Informed Educational Practices Certificate

» Director of Special Education Endorsement GET STARTED ON YOUR GRADUATE EDUCATION JOURNEY TODAY! SCAN TO REQUEST MORE INFORMATION SAVE 20% ON TUITION through our Education Alliance Partner program! Learn more by visiting northcentralcollege.edu/edu-alliance

40

GRADUATE PROGRAMS

PROGRAMS

OFFERED

CONTACT

The School of Graduate and Professional Studies grad@noctrl.edu | 630-637-5555

US

northcentralcollege.edu/grad

Dr. Melissa Byrne

Dr. Melissa Byrne

Enhancing Educational Excellence: Barrington 220's Implementation of the Revised Danielson Framework

Abstract

In alignment with their strategic plan Framework 220, Barrington 220 has embarked on an innovative journey to implement the revised Danielson Framework, enriching teaching practices and nurturing professional growth within the district. This initiative underscores the district's steadfast dedication to the strategic priorities outlined in Framework 220, which emphasizes personalized learning and inclusive education. By integrating the revised Danielson Framework into the fabric of its educational approach, Barrington 220 is fostering a culture where educators are empowered to design instruction to meet the diverse needs of every student. As Barrington 220 advances in this transformative journey, it is not merely implementing a framework, but aligning with the overarching vision of Framework 220, where innovation and excellence converge to shape the future of learning experiences in Barrington 220.

Strategic Planning and the Revised Danielson Framework

In the ever-changing landscape of education, the

41 Article

pursuit of excellence is perpetual, driven by a commitment to student learning, innovation, and continuous improvement. In Barrington 220, we have had the opportunity to focus on the future of our district by developing and implementing a new strategic plan, Framework 220. Framework 220 has multiple components that will help shape the work and future of our district in the years to come. Those components are a Mission Statement, Core Beliefs, a Learner Profile, and six Strategic Priorities.

Our six Strategic Priorities are:

• Community Partnerships and Communication

• Health and Well-Being

• Inclusive Education

• Future Readiness

• Personalized Learning, and

• Stewardship.

These strategic priorities serve as guiding pillars, enabling us to collaboratively delineate objectives and action plans supported by internal Design Teams.

Under the umbrella of inclusive education, our focus extends to various objectives, notably hiring practices and Professional development. Within this realm, our Design Team has meticulously defined objectives aimed at fostering the recruitment, retention, and support

of a diverse cadre of high-caliber staff. Additionally, we are committed to the ongoing development and execution of a comprehensive professional development plan encompassing inclusive education and culturally responsive teaching practices, which prominently feature the revised Danielson Framework for Teaching.

By seamlessly integrating the revised Danielson Framework into our educational ethos, Barrington 220 cultivates an environment where educators are empowered to tailor instruction to meet the diverse needs of every student. Released in 2022, the revised framework serves as a beacon guiding our district toward the enhancement of teaching methodologies, enrichment of student learning experiences, and the establishment of inclusive, equitable, and affirming educational environments.

In the fall of 2022, the district’s Joint PERA Committee (Supervisory Task Force) engaged in professional learning on the revised Danielson Framework, taking a deep dive into the Framework Clusters and the revised Domains. There are six themes that emerge from the 2022 framework which include equity, cultural competence, high expectations, developmental appropriateness, attention to individual

42

Enhancing Educational Excellence (cont.)

students, and student assumption of responsibility. After building capacity as a team and discussing implications for implementation, the Supervisory Task Force made the decision to implement the revised Danielson Framework in the 2023-2024 school year.

indicators and look-fors. Subsequently, all staff received initial professional development during a spring staff

...to kickstart the academic year, each principal conducted a refresher on the revised Danielson Framework, ensuring that all stakeholders were adequately prepared.

meeting to ensure a foundational understanding before the culmination of the school year.

Planning for and Implementation of the Revised Danielson Framework

To ensure a successful implementation of the revised Framework, the remainder of the 2022-2023 school year was dedicated to collaborating with administrators and teachers in designing and implementing professional learning initiatives. A set of common performance indicators and look-fors were developed to enhance the capacity of all staff members. The District Leadership Team engaged in targeted professional development to deepen their understanding of the revised domains while beginning to establish inter-rater reliability through meticulous observation analysis. Concurrently, the District Equity Team and Building Equity Cohorts underwent professional learning on the revised Domains, contributing to the formulation of common performance

During the summer of 2023, over 100 staff members participated in a series of courses offered through our Summer University program, providing immersive learning experiences and facilitating early planning utilizing the framework as a guide to support instructional planning. Furthermore, to kickstart the academic year, each principal conducted a refresher on the revised Danielson Framework, ensuring that all stakeholders were adequately prepared.

Continued Work

The journey of implementing the revised Framework has continued throughout this school year through personalized learning opportunities for teachers and administrators, which includes instructional walkthroughs identifying evidence of the Domain Components and continued work with inter-rater

43

reliability and calibration with our teacher evaluators. Additionally, our Supervisory Task Force is currently drafting specialty rubrics for non-classroom positions such as Teacher Librarian, Instructional Coach, and Social Worker slated for implementation in the fall of 2024.

In conclusion, by harnessing the transformative potential of the revised Danielson Framework, Barrington 220 is laying the foundation for a future that empowers excellence in every learner.

Dr. Melissa Byrne is in her third year in the role of Assistant Superintendent of Teaching and Learning in Barrington 220. Before coming to Barrington 220, Dr. Byrne served in St. Charles School District 303 for 15 years in multiple capacities, including middle school English Language Arts teacher, Associate Director of Curriculum, and Director of College and Career Readiness. Dr. Byrne also serves as an adjunct professor at Aurora University, teaching undergraduate and doctoral students, and sitting on various dissertation committees. Dr. Byrne's passions and areas of expertise within the field of education include curriculum and instruction, competency-based learning, career pathway development and implementation, personalized learning, and student agency. Follow Melissa @DrMelissaByrne on X!

44

Educational Excellence (cont.)

Enhancing

Transforming Early Childhood Environments: A Unique Approach

The early childhood physical environment holds a powerful and positive (or negative) influence on young children’s growth and development. Recognizing the important influence of early childhood environments, the Freeport School District 145 made a commitment to transforming its preschool environments and began a complete renovation of eight classrooms in the 20222023 school year concluding in 2024. Reimaging and transforming these environments involved a wealth of the district’s stakeholders including the students, families, board members, administration, and teachers.

The Freeport School District 145 is located in the northwest corner of Illinois and serves approximately 3800 students. Within the school district, there are four elementary schools, which house 240 early childhood students under the Preschool For All and Preschool For All Expansion Grant. At least 75% of the preschool students live at (or below) the 100% poverty line.

45 Article

Sarah Latimer

Dr. Sandra Duncan

Research has illustrated the positive relationships between classroom design and the development of young children’s growth and learning. There were seven key elements that were considered in the reimagination of the district’s preschool classrooms.

1. Physical Layout and Organization:

The physical layout of the classroom can influence how young children engage with the environment and interact with their peers and teachers. Well-organized spaces with clearly defined learning areas, accessible materials, and ample room for movement support children's independence, engagement, and exploration.

2. Flexibility and Adaptability:

Classroom designs that offer flexibility and adaptability allow for various learning activities and accommodate different teaching approaches. Flexible furniture arrangements and multifunctional spaces enable teachers to create different learning settings, such as small project work, individual exploration, or collaborative projects, based on young children's needs and learning objectives.

3. Comfort and Safety: Comfortable and safe classrooms promote a positive learning environment. Adequate lighting, appropriate temperature control, and comfortable seating

contribute to children's physical wellbeing and attention. Additionally, ensuring safety features, such as ageappropriate furniture, secure storage, and childproofing is essential to prevent accidents and create a sense of security.

4. Access to Learning Materials:

Classroom design should provide easy access to age-appropriate learning materials, books, and resources. Open shelves, adequate storage spaces, and displays of children's work facilitate independent exploration and encourage children to interact with a variety of open-ended materials that support their learning and development.

5. Use of Color and Visual Stimuli:

Colors, visuals, and displays in the classroom can impact children's mood, attention, and engagement. Thoughtful use of color schemes, well-designed vertical learning spaces, and displays of children's work can create a visually stimulating and inspiring environment that supports active and child-led learning and creativity.

6. Acoustic Considerations: Noise levels in the classroom can significantly affect children's ability to concentrate and communicate. Classroom design should incorporate acoustic measures to reduce background noise, such as soundabsorbing materials, proper insulation,

46

Childhood Environments (cont.)

... childhood experiences and education lay the foundation for future successes, affecting physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development.

Investing in the well-being and development of young children is crucial for building a strong and prosperous society. At Freeport School District 145, we believe that investing in the quality of early childhood in our community dramatically improves the future of all children and their families.

-Dr. Anna Alvarado, Superintendent

and strategic furniture placement to create a quieter and more conducive learning atmosphere.

7. Technology Integration: As technology becomes more prevalent in education, classroom design should consider the integration of appropriate technological tools. The provision of adequate power outlets, internet connectivity, and flexible technology spaces can support the use of digital resources and interactive learning experiences.

Design

Principles

In addition to the seven key elements, the district’s classroom transformations focused on the incorporation of three design principles, which were (1) metamorphic, (2) biophilic, and (3) empathic design. These design principles helped transform everyday elementary

school classrooms into places where young students can thrive in welcoming environments and calming spaces. By combining metamorphic, biophilic, and empathic design principles, the Freeport School District 145 intentionally created learning environments that emphasized the cognitive, physical, emotional, and social needs of young learners.

More importantly, these three design approaches contributed to the overall well-being and development of our youngest learners. It was important to use these three design approaches in order to address the increasing mental health and behavior challenges of Freeport students. These challenges include adverse childhood experiences such as housing insecurity, chronic illness, families with substance and physical abuse, incarcerated parents,

47

and violence. In addition, stakeholders from the school district strongly believe that the classroom for many children is a point of refuge, a place of security, and a space of safety. Intuitively, the district understood the importance of classroom environments as an essential part of young children’s emotional and physical well-being.

#1: EMPATHIC DESIGN

Transforming early childhood environments using empathic design involves understanding and designing from the end user’s viewpoint, which is the young child. To understand the child’s viewpoint, try these exercises. With each exercise, ask: What do I see?

• Knee-walk around your classroom.

• Skootch down to the height of the children with whom you teach in the middle of the classroom door.

• Sit down in the middle of the room. and look toward each corner of the classroom.

• Knee-stand directly in front of a bulletin board.

At the child’s height, do you see the backs of cabinets, table legs, or custodial furniture? Were you able to see into all the learning areas or did furniture block your view? Were you able to see what’s across the room or only what’s directly in front of you?

48

Childhood Environments (cont.)

A. Adult Viewpoint

B. Child Viewpoint

The two images below were taken at the exact same spot in the classroom. The only difference was that Image A was taken from the adult’s height and Image B was taken from the child’s height. A child’s viewpoint is totally different than an adult’s viewpoint. Consequently, it is very important to be mindful and design toward their viewpoint and not your own.

There are several strategies for improving children’s viewpoints, especially from the middle of the classroom. The biggest strategy, however, is transparency (the ability for children to see the classroom from their height). A rule of thumb for creating transparency is to position furniture in such a way that children can see across the room from anywhere they are located. The easiest way to do this is to position taller furniture against the classroom walls with shorter furniture in the middle of the room. Another strategy is to position shelving units so children are not looking at the back of cabinets. When children can readily see what’s on the shelves, they are more likely to be engaged with its contents. Finally, too much furniture in the classroom is the biggest barrier to transparency so consider reducing the number of shelving units in the room. Instead of including a large bookshelf that is visually and physically large, for example, try placing books in several baskets that are scattered throughout the classroom.

By applying empathic design principles, early childhood environments can be transformed into nurturing, inclusive, and engaging spaces that support children's holistic development and wellbeing. Collaboration between designers, educators, parents, and children is key to creating environments that truly reflect and respond to their needs.

49

#2: METAMORPHIC DESIGN

The evolution of a butterfly includes going through the metamorphic stages changing from caterpillar, to chrysalis, to butterfly, and emerging with wings ready to fly. Children are much like butterflies. They are in a constant state of change and evolving in every way: emotionally, socially, cognitively, and physically. Young children transform from year to year, month to month, week to week, hour by hour, minute to minute—and even in the blink of an eye. If we believe that children are like butterflies and ever-changing, then it becomes important to design our environments to meet children’s continuous change.

Metamorphic design focuses on change and encourages adaptability and flexibility in classroom space, which allows the environment to evolve with the changing needs of children. By incorporating elements that can be easily modified or rearranged, educators can create environments that support various activities and learning styles. This design approach encourages exploration and creativity, providing children with the freedom to shape their own learning experiences. One good example of metamorphic design is flexible seating.

In many classrooms, teachers assign children places where they must sit. This place might be a specific chair at a

table or it might be an identified spot on the group meeting rug where the teacher has affixed the child’s name to a spot indicating where children must sit. Regardless of personal preferences, children have no choice of where to sit. They must sit where the teacher has dictated. Ultimately, the teacher has all the power, and the children have none. When teachers rely on power to control children’s bodies and minds, they relinquish their autonomy and the opportunity to practice making good choices. Giving children choices is a relatively small but consequential mindset shift. Rather than assigning children spots on the rug where they must sit, for example, let them choose where they want to sit and with whom. Let them choose whether to sit alone or with a friend. If (by chance) they make an inappropriate choice, then figure out a way to turn the wrong choice into a lesson in learning. Giving children opportunities to practice making choices ultimately acknowledges and respects their humanity and recognizes the fundamental importance of agency.

In addition to giving choices about where to sit, consider giving children opportunities for a variety of different types of seating. Typically, classrooms offer two types of seating, which are on the floor or a traditional chair. In real life, however, there are so many

50

Childhood Environments (cont.)

different types of seating (i.e., rocking, benches, stools, recliners, couches, and overstuffed chairs). They come in all sizes, shapes, colors, and textures. Think about your own home. How many different seating options do you have? There are probably quite a few. Yet, there may be few seating options or choices in your classroom. Consider increasing the variety of seating options using the following ideas:

• Rocking Chairs

• Benches

• Ottomans

• Stools

• Swings

• Beanbags

• Tree Stumps

• Futons

• Couches

• Chaise Lounges

• Pillows

• Overstuffed Chairs

• Crates with Cushions

• Beach Chairs

• Camper Stools

interests of children. The metamorphic approach recognizes that early childhood is a period of rapid growth, development, and exploration, and aims to design

Transforming early childhood environments using a metamorphic approach involves creating dynamic and adaptable spaces that can evolve and respond to the changing needs and

environments that support children's curiosity, creativity, and self-discovery. Here are some additional strategies for implementing a metamorphic approach in early childhood environments:

51

1. Flexible Layouts: Design spaces with modular furniture, movable partitions, and versatile storage solutions. This allows for easy reconfiguration of the environment to accommodate different activities, group sizes, and learning styles. Provide spaces that can be transformed from individual workstations to collaborative areas, or from quiet reading corners to active play zones.

2. Mobile and Portable Elements: Incorporate mobile and portable elements such as lightweight furniture, movable learning stations, and flexible play equipment. These elements can be easily rearranged or transported to different areas of the environment, allowing for variety and adaptability in the use of space.

3. Transformable Surfaces: Integrate transformable surfaces that can be altered or customized by children. For example, writable walls, magnetic boards, or interactive display panels can be used

to promote creativity, collaboration, and self-expression. These surfaces can be easily changed or updated based on the children's interests and projects.

4. Personalized Spaces: Provide opportunities for children to personalize their own spaces within the environment. Allow them to display their artwork, creations, or personal items, giving them a sense of ownership and identity. This can be achieved through individual cubbies, display boards, or designated areas for personal belongings.

#3: BIOPHILIC DESIGN

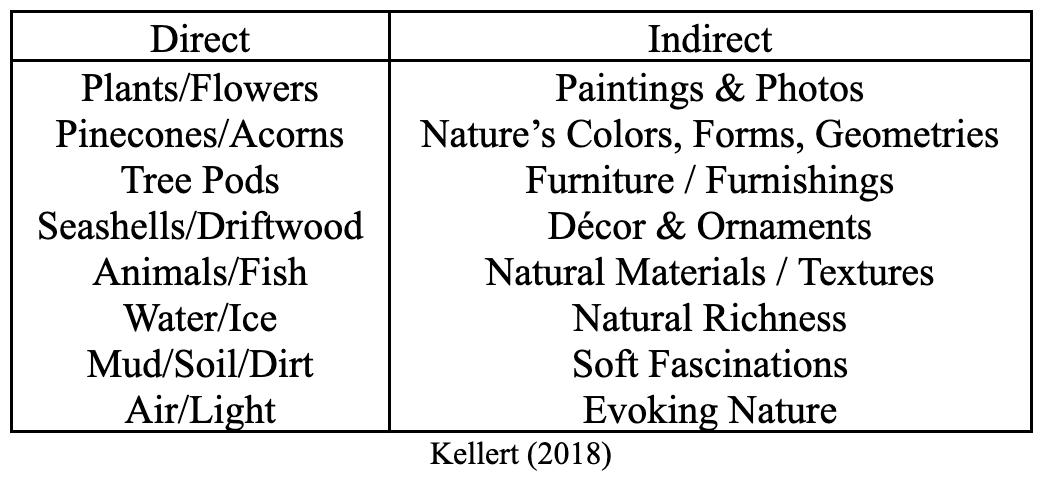

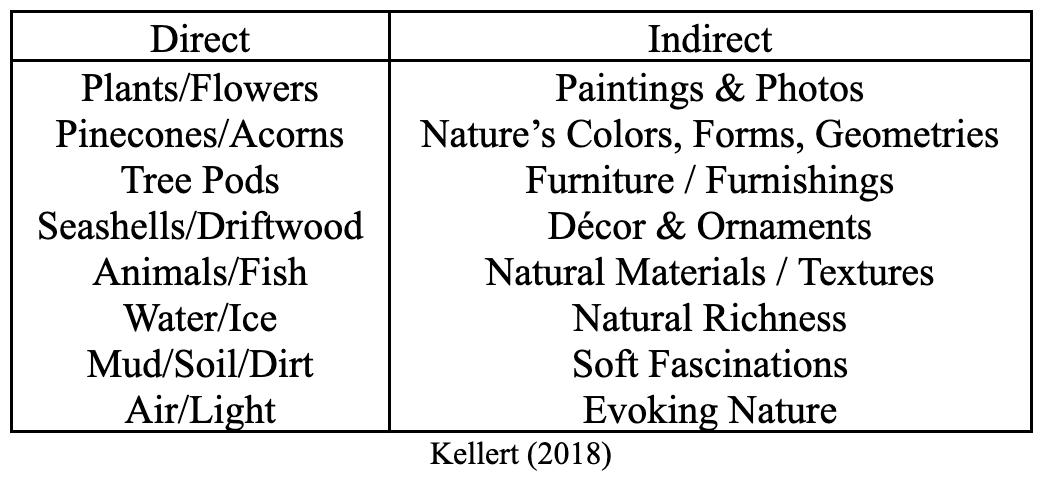

Biophilic Design is a design approach that acknowledges the innate human connection to the natural world and proposes ways to incorporate nature directly and indirectly into the learning environment. Direct experiences include animals, birds, and anything that is alive or has been alive at some time in the past. Indirect objects of nature include representation of nature. For example,

52

Childhood

(cont.)

Environments

the representation of nature includes shapes, forms, and textures.

The importance of connecting children with nature cannot be overstated. Children who have regular contact with natural environments tend to have better cognitive functioning, improved attention spans, and reduced stress levels. By incorporating nature-inspired design elements such as natural light, natural materials, and representations of the natural world, the team at Freeport School District 145 created environments that promote learning, creativity, and well-being among young learners. The biophilic approach not only enhances the physical environment but also nurtures the hearts and minds of young learners, setting the stage for a lifelong love and awe of nature and learning.

One effective way to implement the biophilic approach is to bring the outdoors indoors by incorporating natural items such as pinecones, tree cookies, driftwood, and seashells into the learning environment. The district’s preschool classrooms made a concerted initiative to reduce the amount of plastic and replace it with natural elements. For example, teachers replaced plastic containers with natural containers

53

Childhood Environments