Impact • Service • Advocacy Quarterly Journal - May 2023

Gardener

Be A

Do you know someone who might be a candidate for IL ASCD membership? Please share this digital journal with them. We are always looking to reach additional Illinois educators who would enjoy more information about learning, curriculum, Common Core, PERA and education in general.

If you are reading this and are not yet a member, please join!

Our Membership Form

2

GET INVOLVED WITH OUR SOCIAL MEDIA!

A Letter from the President

Belinda Veillon, President bveillon@nsd2.com

Welcome to this beautiful time of the year! Mostly a time of rebirth after a long and, at times, harsh winter. We look forward everyday to see what new beauty has sprung from the Earth. The vibrant green of the grass, the harmonious tunes of the birds, and the smell of freshness. In Spring, everything around us can be a haiku moment.

The Earth readies for the season of growing and new beginnings. As educators, we are gardeners. What will we sow? What do we desire to reap? And, what do we need to do in between to ensure that our time and efforts benefit those around us and ourselves?

The metaphors abound, and can be so cliche. But, when seeking metaphors for growing a garden and being an educator, if the metaphors are personal, they are not cliche. There resides a certain calm inside as I attempt to metaphorically answer related to my career as a gardener of humans and thoughts. How am I a gardener?

3

Quick Links

5 Whole Child

Book Review: DeImplementation 20 Resource Corner 26 If You Water It 32 Novice Gardener 36 Strategic Planning 41 Instructional Coaching 46 Growing Independent Learners 52 Growing the Teaching Profession 59 Fertilizing Student Growth Using MTSS 63 Affinity Spaces 69 Agronomic STEM 71 Sustainable Gardens for Schools 78 Upcoming Events

15

ILASCD Leaders

Belinda Veillon, President bveillon@nsd2.com

Akemi Sessler, Past President asessler@sd25.org

Scott England, President-elect escottengland@gmail.com

Amy Warke, Treasurer awarke2008@gmail.com

Debbie Poffinbarger, Media Director debkpoff@gmail.com

Amy MacCrindle, Secretary amaccrindle@district158.org

Ryan Nevius, Executive Director rcneviu@me.com

Bill Dodds, Associate Director dwdodds1@me.com

Task Force Leaders:

Membership & Partnerships

Denise Makowski, Andrew Lobdell

Communications & Publications

Joe Mullikin, Jeff Prickett

Advocacy & Influence

Richard Lange, Brenda Mendoza Program Development

Bev Taylor, Terry Mootz, Sarah

Cacciatore, Dee Ann Schnautz, Doug Wood, Amie Corso Reed

In what ways have I been a gardener?

What have I learned in my attempts to be a gardener?

At what point in our professional environment will we finally be able to experience the rebirth and rejuvenation that Spring annually brings. The struggles of the last few years have impacted our soil, our tools, our conditions, our seedlings. Gardeners do not give up. Their toils include observing and responding to the needs of their seedlings. Some things are in control of the gardener, and some things are not within the gardener’s control, but that never stops the gardener supporting the seedlings for the best possible outcome.

As educators, we are the soil, the nourishment and the sunlight. The labors of gardening are self-evident. And, the beauty is, we will take what we have learned and nurture a new crop. Approach everyday with a gardener’s heart, mind, and soul.

Belinda Veillon, President IL ASCD

4 A Letter from the President (cont.)

Whole Child

For the Growth of the Child: A Mindset and Whole Child Approach

Spring in Illinois packs quite a punch, when the gray days and dreary weather of winter finally give way to bursts of color. If Spring carried a message at all, it would be “rebirth, renewal, regeneration,” each word representing a different manifestation perhaps of growth—Growth, by definition, requires the channeling of movement into a purposeful action. Yet growth usually does not come about on its own—growth happens as a result of intention, from developing our talents—and believing they can be developed—as a result of one’s own efforts to improve (Dweck, 2006).

This is the idea behind the growth mindset (as opposed to a fixed mindset, in which one’s talents and abilities remain static). Dweck (2006) posits that no one is completely one or the other, rather, every person has a combination of both mindsets and both evolve and are impacted by a person’s individual experiences. Additionally, like growth, gardening, and being a gardener, providing a space that is ideal for growing is one that is cultivated with intention for students to learn, create, make connections, stumble and rise while being supported. Thus demonstrating the tenets of, not just implementing, but promoting and

5

Dr. Yurimi Grigsby

Dr. Israel Espinosa

Dr. Andrea Dinaro

instilling the safe, healthy, supported, engaged, and challenged tenets of the Whole Child Approach a foundation to help grow in learners a belief in the self.

Growth mindset and gardening

Growth mindset can be compared to gardening in several ways. In gardening, just as in learning and personal growth, there are stages of growth, setbacks, and opportunities for improvement.

Here are some ways in which a growth mindset can be compared to gardening, in alignment with the ASCD Whole Child Framework:

1. Preparation: Before planting a garden, it is important to prepare the soil and create the right conditions for growth. Similarly, in fostering a growth mindset, it is important to create a supportive and encouraging environment that promotes a safe space, effort and persistence. SAFE Each student learns in an environment that is physically and emotionally safe for students and adults.

2. Planting: When planting a garden, it is important to choose the right plants and place them in the right location to ensure optimal growth. Similarly, in fostering a growth mindset, it is important to provide students with the right challenges and opportunities

to encourage their growth and development. ENGAGED Each student is actively engaged in learning and is connected to the school and broader community.

3. Watering and nurturing: In order for a garden to thrive, it needs to be regularly watered and nurtured. Similarly, in fostering a growth mindset, it is important to provide students with regular feedback and encouragement to help them stay motivated and engaged in the learning process. SUPPORTED Each student has access to personalized learning and is supported by qualified, caring adults.

4. Pruning and weeding: Just as in gardening, where it is important to prune back dead or overgrown plants and remove weeds that can hinder growth, in fostering a growth mindset it is important to help students identify and overcome obstacles and challenges that can hinder their progress. CHALLENGED Each student is challenged academically and prepared for success in college or further study and for employment and participation in a global environment.

5. Growth and harvest: When a garden is well-tended and nurtured, it can produce a bountiful harvest. Similarly, when students are encouraged to

6

Whole Child (cont.)

develop a growth mindset and work hard to achieve their goals, they can achieve academic success and personal growth. They also learn what a healthy environment needs, and have the opportunities to practice.

HEALTHY Each student enters school healthy and learns about and practices a healthy lifestyle.

Overall, the analogy of gardening can help teachers and parents understand the importance of fostering a growth mindset in children and students. Additionally, the Whole Child Framework helps schools and educators be certain to tend to each tenet mindfully and with purpose. Just as a garden requires consistent effort and care to thrive, so too does a growth mindset require ongoing support and encouragement to flourish.

What a growth mindset looks like in teaching and learning contexts

A growth mindset is a belief that one’s abilities and talents can be developed and improved through dedication, hard work, and persistence. It is the opposite of a fixed mindset, which assumes that abilities are innate and cannot be changed. In teaching and learning contexts, a growth mindset can foster a love of learning, encourage risk-taking and experimentation, and promote resilience in the face of challenges.

Here are some examples of what a growth mindset looks like in teaching and learning contexts, in alignment with the ASCD Whole Child Framework:

1. Emphasizing effort over talent: Teachers with a growth mindset emphasize the importance of effort and hard work in achieving academic success, rather than just innate talent or ability. They provide students with opportunities to learn and practice new skills, and encourage them to persevere even when they face challenges. HEALTHY Each student enters school healthy and learns about and practices a healthy lifestyle.

2. Encouraging risk-taking and experimentation: Teachers with a growth mindset create a safe and supportive environment where students feel comfortable taking risks and experimenting with new ideas. They encourage students to try new things, make mistakes, and learn from their failures. SAFE Each student learns in an environment that is physically and emotionally safe for students and adults.

3. Fostering a love of learning:

Teachers with a growth mindset instill a love of learning in their students by promoting curiosity, creativity, and exploration. They encourage students to ask questions, seek out new

7

information, and make connections between different subjects. ENGAGED Each student is actively engaged in learning and is connected to the school and broader community.

4. Embracing challenges as opportunities for growth: Teachers with a growth mindset view challenges as opportunities for growth and learning, rather than as obstacles to be avoided. They help students develop strategies for overcoming challenges and provide them with support and encouragement as they work through difficult problems. CHALLENGED Each student is challenged academically and prepared for success in college or further study and for employment and participation in a global environment.

5. Providing feedback that promotes growth: Teachers with a growth mindset provide feedback that is focused on helping students improve their skills and knowledge, rather than just evaluating their performance. They provide specific, actionable feedback that helps students identify areas for improvement and develop strategies for addressing them. SUPPORTED Each student has access to personalized learning and is supported by qualified, caring adults.

Overall, a growth mindset is essential for creating a positive and supportive learning environment that promotes personal growth and academic success. Teachers with a growth mindset can help their students develop the skills, knowledge, and mindset they need to succeed in school and beyond. The ASCD Whole Child Framework supports schools in aligning identifying the ways in which they are moving beyond singular or siloed definitions of success, and serving students in multiple opportunities.

Strategies and Whole Child alignment to foster a growth mindset

Fostering a growth mindset involves promoting the belief that skills and abilities can be developed through effort, persistence, and dedication. The ASCD Whole Child Tenets strengthen the ability to identify evidence of those areas of strength or opportunities for improvement in schools. Here are some strategies that can help foster a growth mindset in students:

1. Encourage effort and persistence (Engaged): Emphasize the importance of effort and persistence in achieving success, rather than innate talent or ability. Encourage students to take on challenges and to persist even when they face setbacks or difficulties.

8

Whole Child (cont.)

2. Emphasize the power of “yet” (Safe): Encourage students to add the word “yet” to the end of statements such as “I can’t do this.” This simple addition can help shift the focus from fixed abilities to the possibility of growth and development.

3. Model a growth mindset (Healthy): Teachers and parents can model a growth mindset by acknowledging their own mistakes and setbacks and emphasizing the importance of learning from them. Avoid praising innate abilities or talent, and instead praise effort, hard work, and perseverance.

4. Provide specific feedback (Supported): Provide specific and actionable feedback that focuses on how students can improve their skills and knowledge so that students know what, where, and how they are growing. Again, avoid evaluative feedback that focuses on innate abilities or fixed traits.

5. Encourage reflection and selfassessment (Supported): Encourage students to reflect on their learning process and assess their progress. Help them identify areas where they have improved and areas where they can still develop.

6. Provide opportunities for challenge and growth; Encourage risk-taking and experimentation (Challenged): Provide students with opportunities to take on challenging tasks and projects that require effort and persistence. Encourage risk-taking and experimentation, and provide support and encouragement as they work through difficult problems.

7. Teach growth mindset explicitly (Supported): Provide students with explicit instruction on the concept of growth mindset and how it relates to learning and achievement. Use examples and case studies to illustrate the importance of effort, persistence, and dedication in achieving success.

8. Set high expectations (Challenged): Set high expectations for students and provide support and encouragement as they work to meet those expectations, as well as the ability / willingness to attempt and learn from any experience.

By implementing these strategies, teachers and parents can help foster a holistic growth mindset in students, which can promote resilience, motivation, and academic success in safe, healthy, supported, engaged, and challenged ways.

9

Whole Child (cont.)

In closing, by starting with intention, using a Whole Child foundation, and implementing these growth mindset strategies, educators, parents, and administrators can, like a gardener, provide an ideal space for growing.

Garden assessment: Identify in what ways you or your teams are already promoting and instilling the safe, healthy, supported, engaged, and challenged tenets of the Whole Child Approach as a foundation to help prepare your garden (environment), and help learners thrive in every season.

is a seminal work on the importance of a growth mindset in achieving success in various domains, including education. It provides evidence and case studies to support the idea that individuals who embrace a growth mindset are more likely to succeed and be resilient in the face of challenges.

References

ASCD. Whole child tenets. https://www. ascd.org/whole-child

Dweck, .C. (2016). What having a “growth mindset” actually means. Harvard Business Review. https:// hbr.org/2016/01/what-having-agrowth-mindset-actually-means

The following are some references to support the importance of a growth mindset in teaching and learning contexts:

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. This book by psychologist Carol Dweck

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge. Visible Learning is a research-based book that synthesizes over 800 meta-analyses related to educational achievement. The author, John Hattie, identifies the importance of a growth mindset in learning and teaching, stating that students who believe that intelligence and abilities can be developed tend to have higher academic achievement and are more likely to persist in the face of challenges.

Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child development, 78(1), 246-263. This study investigated the relationship between mindset and academic achievement in middle school students. The results showed that students who believed

10

that intelligence is malleable and can be developed (i.e., had a growth mindset) achieved higher grades and were more motivated than those who believed that intelligence is fixed.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational psychologist, 47(4), 302-314. This article discusses how a growth mindset can promote resilience in the face of academic setbacks and challenges. The authors suggest that interventions that promote a growth mindset can help students develop a more positive and adaptive mindset and improve their academic performance.

The following resources are focused on fostering a growth mindset:

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. In this book, psychologist Carol Dweck discusses the concept of a growth mindset and provides evidence and strategies for promoting it. She emphasizes the importance of effort and persistence in achieving success, and provides examples of how parents, teachers, and coaches can foster a growth mindset in children.

Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child development, 78(1), 246-263. This study found that interventions that emphasized the concept of a growth mindset were effective in improving academic achievement in middle school students. The authors suggest that explicit instruction on the concept of a growth mindset can help students develop a more positive and adaptive mindset.

Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). What Predicts Children’s Fixed and Growth Intelligence Mind-Sets? Not Their Parents’ Views of Intelligence but Their Parents’ Views of Failure. Psychological science, 27(6), 859869. This study found that parents who emphasized the importance of learning from failure and adversity were more likely to have children with a growth mindset. The authors suggest that parents can play a key role in fostering a growth mindset in children by modeling and encouraging adaptive attitudes and behaviors.

Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Romero, C., Smith, E. N., Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Mind-set interventions

11

are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological science, 26(6), 784-793. This study found that a brief intervention that emphasized the concept of a growth mindset was effective in improving academic achievement in lowperforming high school students. The authors suggest that this type of intervention can be a scalable and cost-effective way to promote a growth mindset in students.

The following references provide evidence and strategies for fostering a growth mindset in children and students. As well as some that connect growth mindset to gardening:

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Digital, Inc.

Diener, C. E., & Dweck, C. S. (1978). An analysis of learned helplessness: II. The processing of success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(3), 340-345.

Boaler, J. (2016). Mathematical mindsets: Unleashing students’ potential through creative math, inspiring messages and innovative teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T., & Volet, S. E. (2015). Teacher emotions in the classroom: Associations with

students’ engagement, classroom discipline and the interpersonal teacher-student relationship. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(4), 385-403.

Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(31), 8664-8668.

Note: While these references do not specifically compare growth mindset to gardening, they discuss the importance of growth mindset in academic achievement, emotional well-being, and overcoming obstacles. The analogy of gardening can be used to illustrate these concepts and provide a relatable example for teachers and students alike.

Dr. Yurimi Grigsby is a Professor at Concordia University Chicago in the College of Education, Division of Curriculum, Technology, and Inclusive Education. She is the Program Leader for the ESL and TESOL programs supporting educators working with Culturally and Linguistically Diverse K-12 and adult learners. Contact: yurimi.

grigsby@cuchicago.edu

12

Whole Child (cont.)

Dr. Israel Espinosa is the Chair of the Psychology programs at Saybrook University for psychology programs— generalist track as well as specializations at the Master’s and Doctoral levels. Contact: iespinosa@saybrook.edu

Dr. Andrea Dinaro is Professor of Special Education at Concordia University Chicago, is the Chair of the Division of Curriculum, Technology, and Inclusive Education, and Program Leader for special educationrelated doctoral programs. Contact: andrea.dinaro@cuchicago.edu

13

CHARACTER INITIATIVES

Click here to take the next step!

CULTIVATE THE INNER CHARACTER in yourself, your students, your colleagues and your school. Learn more about North Central’s online resources and start SOWING THE SEEDS OF CHARACTER TODAY! Educational Leadership: For aspiring leaders seeking an endorsement to become a principal, assistant principal, dean, athletic director or department chair. Character Education Certificate: For teachers, school specialists and administrators, social workers and instructional coaches. Start your garden of character virtues today! mbwebster@noctrl.edu 630-637-5842 northcentralcollege.edu/character-initiatives Marsha Webster Character Initiatives Outreach & Recruitment Coordinator

Book Review

Weeding the Education Garden with Peter Dewitt’s De-Implementation: Creating the Space to Focus on What Works

Duginske

Duginske

In our daily academic lives, on the news, and on social media we have become aware of an exodus of educators from our profession as 300,000 public school teachers and staff departed from February 2020 to May 2022 (Dill, 2022). According to a survey conducted by the National Education Association, a staggering 55% of teachers reported they are considering leaving education earlier than planned (Walker, 2022). Knowing public education needs to change to keep our schools staffed, Peter Dewitt has written De-Implementation: Creating the Space to Focus on What Works. DeWitt has created a

framework for school leaders and teachers to weed the education garden and reduce the number of initiatives in our schools. In the introduction of his book, DeWitt reveals this is not just a concern among teachers, but also among educational leaders stating that 42% of principals indicated they were considering leaving the profession (DeWitt, 2022, p. 1). De-implementation is critical to sustaining public education and ensuring our youth receive the highest quality of education they

15

Click the cover to view on Amazon

Review by Jacquie

deserve. DeWitt writes, “What we all need is time to focus and cut down on the noise. We need time to breathe and engage in conversations that focus on deeper impact,” (DeWitt, 2022, p. 10). This forces us to ask ourselves as educators are we doing the right things and are we doing things right?

DeWitt’s De-implementation: Creating the Space to Focus on What Works provides a process for teachers and school/district leaders to de-implement with the focus remaining on student learning. DeWitt leverages Adam Grant and the science of implementation which emphasizes doing less of something does not simply lead to better results, rather it is a balance of quantity and quality (DeWitt, 2022, p. 19). Thus, educators are cautioned to not simply target eliminating practices we are not fond of, but those that are not impactful on student learning.

As DeWitt guides the reader through the process of de-implementation, he provides realistic examples from schools he has successfully completed this work in. DeWitt stresses the importance of collaborating in teams and not in isolation. Through sharing his own experiences, DeWitt allows the reader

the opportunity to engage and reflect on their current practice (DeWitt, 2022, pp. 3-4). He presents discussion questions that educators can ask themselves and colleagues to weed their garden and develop their own path to success.

Although earlier chapters lay the foundation for the work of deimplementation, DeWitt gets down to business in chapter three: “What Gets Deimplemented.” Here, he discusses partial reduction (reducing a practice we engage in) which is where most educators will become familiar with de-implementation (DeWitt, 2022, p. 47). DeWitt provides practical examples of areas we can start to minimize including the number of meetings, emails, assessments, teacher talk (versus student talk), and homework (DeWitt, 2022, p. 48). Through these examples, DeWitt presents rationale on how reducing these initiatives can help lighten the weight on educators, but also be impactful to student learning. DeWitt identifies four criteria for the deimplementation of programs/practices and urges school leaders and teachers to use the criteria as guidance when planning for de-implementation (DeWitt, 2022, pp. 51-52). (Figure 1 on the following page.)

16

Book Review (cont.)

...are we doing the right things and are we doing things right?

planning for de-implementation (DeWitt, 2022, pp. 51-52).

Criteria for De-implementation:

Program/Practice

The program/practice has not been shown to be effective and impactful

The program/practice is less effective or impactful than another available.

The program/practice causes harm

The program/practice is no longer necessary

“De-implementation is not cut and dried,” (DeWitt, 2022, p. 58). As teams initiate de-implementation, DeWitt emphasizes the importance of utilizing direct and indirect evidence as well as valid research when making decisions about the impact initiatives have on student learning. To that point, it is critical that student learning remains the focus and as educators, we are only looking to de-implement initiatives that are proven ineffective.

Example

● Frequent PowerPoint lessons

● Popcorn reading

● One size fits all professional development

● Homework

● Zero Tolerance Policies

● Fixed Groupings

● Chalkboards

● Heavy Textbooks

“De-implementation is not cut and dried,” (DeWitt, 2022, p. 58). As teams initiate de-implementation, DeWitt emphasizes the importance of utilizing direct and indirect evidence

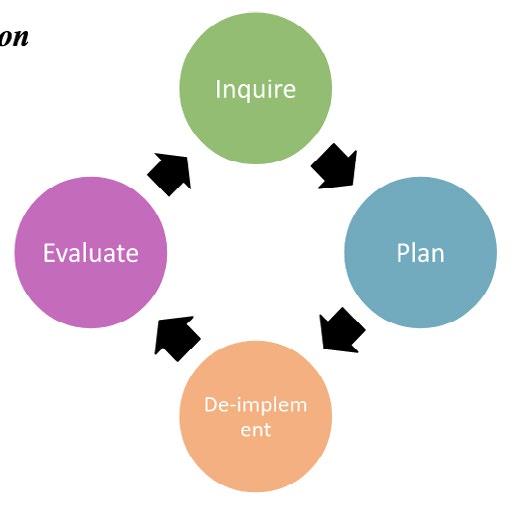

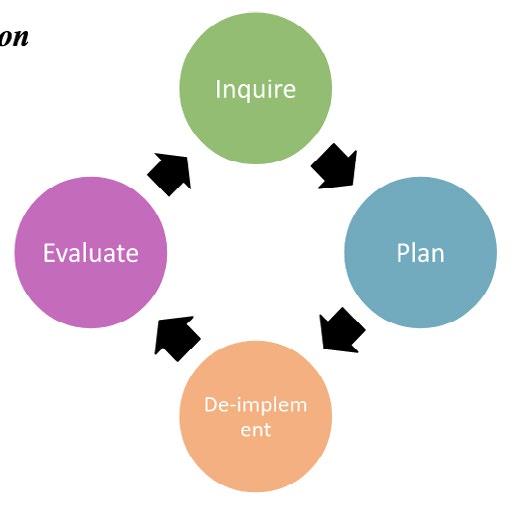

In chapter four: “The Cycle of Deimplementation,” DeWitt shifts from understanding what needs to be de-

implemented to tackling the process, (DeWitt, 2022, p. 66). (Figure 2.)

As DeWitt guides the reader through a thorough explanation of each phase in the cycle of de-implementation, he references one professional experience of when he de-implemented traditional grading and implemented standards-

based grading. Walking the reader through the steps of the process, DeWitt includes templates that educators can utilize within their own schools and teams. Once a team has identified what and why they are targeting for deimplementation, DeWitt also provides a program logic model including a theory of action, resources, activities,

17

FIGURE 1. Criteria for De-implementation

FIGURE 2. Cycle of De-implementation

timetables, and impact (DeWitt, 2022, pp. 78-79). Through the sharing of his experiences, DeWitt ensures the reader knows how to use the tools throughout the process.

Within the program logic model, DeWitt includes a de-implementation checklist. He denotes the deimplementation checklist is needed when a team approach is being utilized to formally de-implement an initiative or activity (DeWitt, 2022, p. 81). The de-implementation checklist has eleven sections that are detailed and userfriendly to be completed by teams.

The final chapter motivates the reader by giving them the tools necessary to find a better work-life balance. Educators and team members become more knowledgeable as they engage in the de-implementation process. DeWitt continues to drive the focus back to students, “De-implementation is about taking our control back in an effort to provide a deeper learning experience for students and that requires the input of each member of the instructional leadership team,” (DeWitt, 2022, p. 96).

DeWitt outlines how to build a team, who should be on the team and cautions against over-utilizing the same teacher leaders in our schools who volunteer routinely and could face burnout. He

suggests the structure for the teams including team roles and the idea of a co-chair to ensure more than one person is leading the work (DeWitt, 2022, p. 98). Continuing to share useful models for the reader, DeWitt provides an example of a pacing guide for deimplementing teacher talk to increase student engagement and learning. The teacher talk pacing guides showcase the de-implementation process over a six-month period including reaching the maintenance stage (DeWitt, 2022, pp. 101-102). He also provides a yearlong pacing guide for standards-based grading, allowing readers to see how de-implementing a large-scale initiative takes time to have the impact we hope to achieve.

It is likely that no matter what phase of the process you are in, roadblocks will exist. There will be challenges and not every teacher will be on board with proposed initiatives and activities. However, DeWitt believes the need for this work is essential and given the times we are currently living in, there is a heightened sense of urgency. DeWitt continues to emphasize, as educational leaders, these conditions will only get worse if we do not set boundaries and tackle de-implementation in our schools. In his final thoughts, DeWitt states “We need to take time to de-implement what doesn’t work in an effort to keep

18

Book Review (cont.)

implementing what does work. Our profession is at stake” (DeWitt, 2022, p. 123). To that end, this bares the question, again, are we doing the right things and are we doing things right?

As we start the process of finishing this school year, and planning for next, districts, leaders, and teachers can utilize DeWitt’s De-implementation: Creating the Space to Focus on What Works to weed our own education gardens. If this work is completed in collaboration with all stakeholders, a path will be made for the future where students and staff can flourish.

References

DeWitt, P. (2022). De-Implementation: Creating the Space to Focus on What Works. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Dill, K. (2022, June 20). School’s Out for Summer and Many Teachers Are Calling It Quits. Retrieved from The Wall Street Journal : https://www. wsj.com/articles/schools-out-forsummer-and-many-teachers-arecalling-it-quits-11655732689

Walker, T. (2022, 1 2). NEA News. Retrieved from NEA Today: https:// www.nea.org/advocating-forchange/new-from-nea/surveyalarming-number-educators-maysoon-leave-profession

Dr. Jacquie Duginske is currently serving as the Executive Director of Learning Services for McHenry Elementary School District 15. Dr. Duginske is an expert in the areas of curriculum design and assessment with a focus on instructional best practices to positively impact student outcomes. Dr. Duginske believes student growth occurs through teacher growth and has built a systemic model of instructional coaching to support teaching and learning.

19

Resource Corner

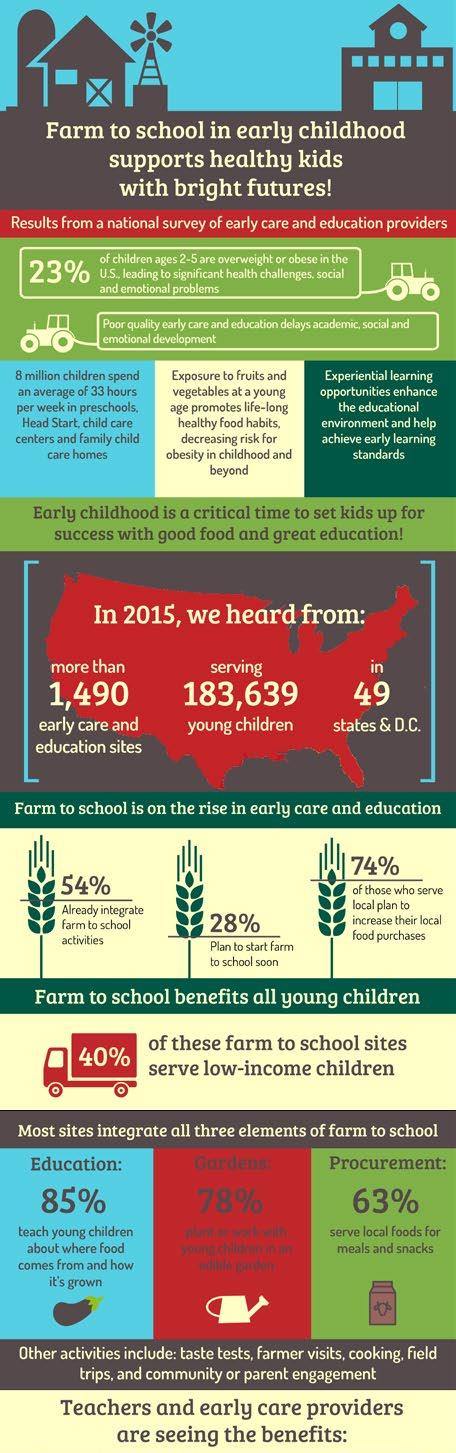

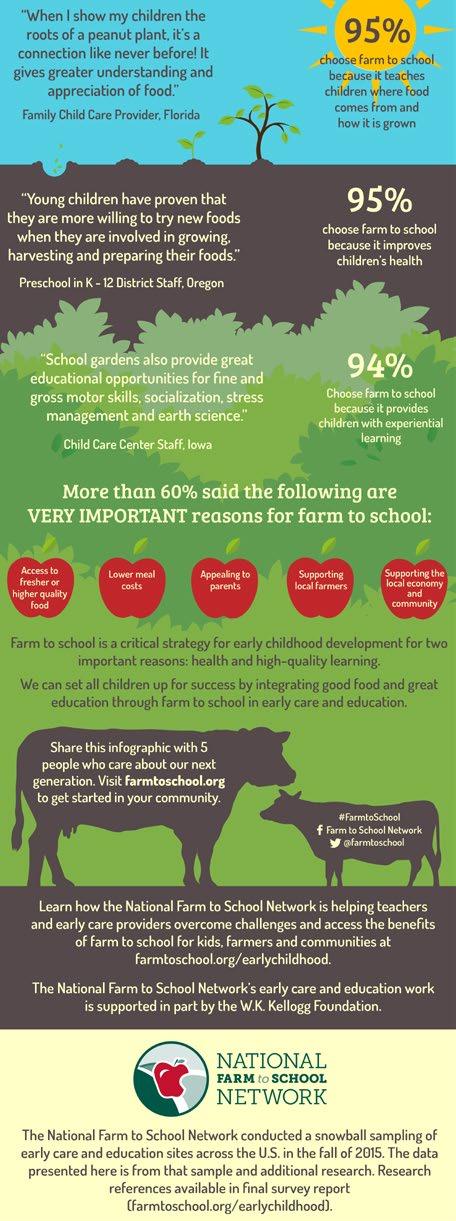

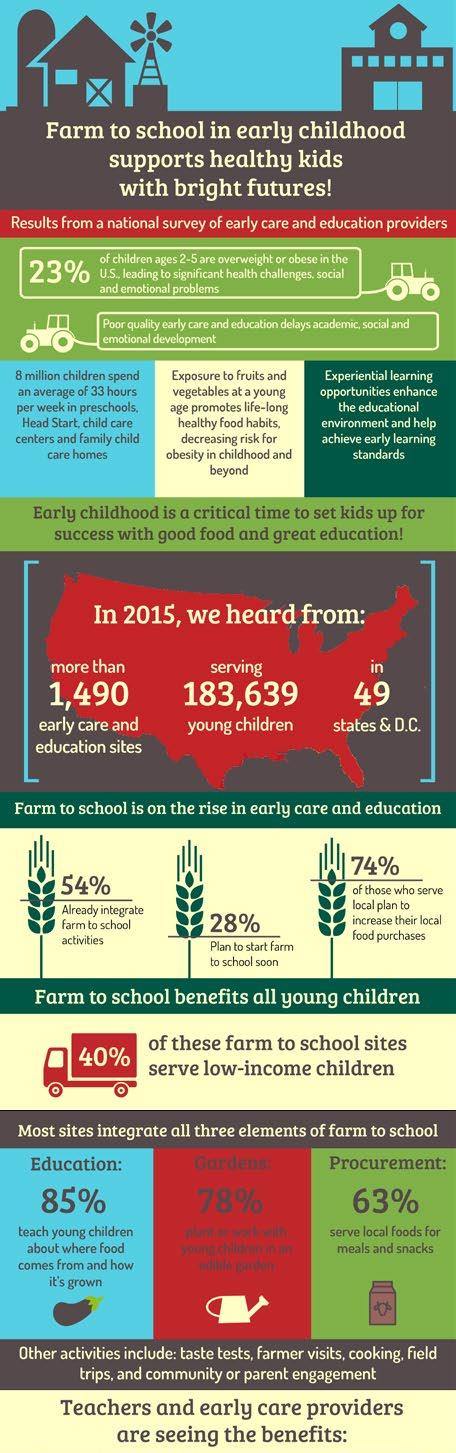

PLANT POWER | 5 BENEFITS OF PLANTS IN THE CLASSROOM

As a teacher, having plants in the classroom can take your teaching game to a whole new level. READ MORE...

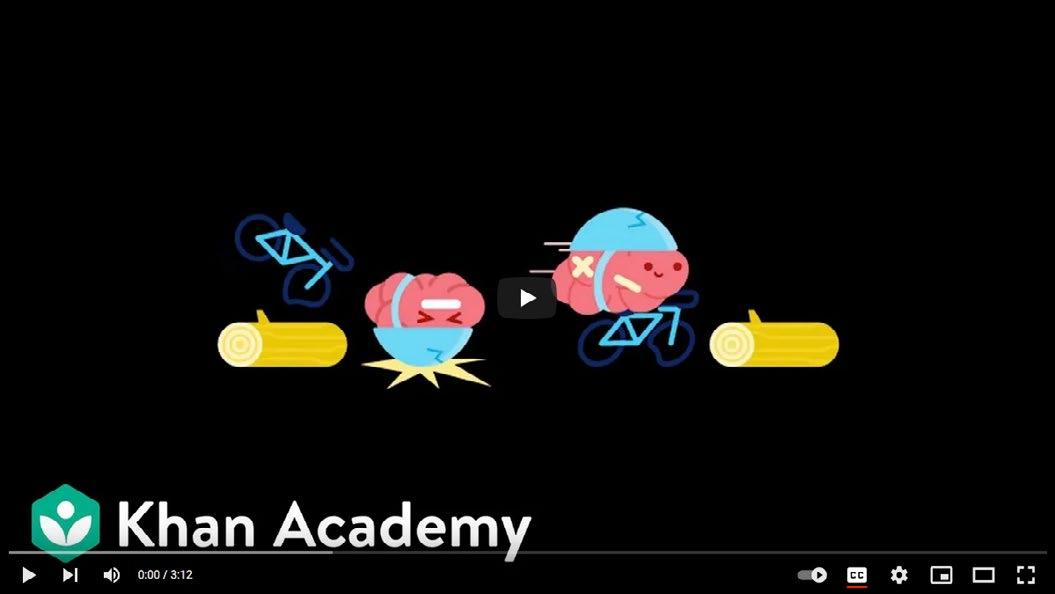

KHAN ACADEMY | LEARNSTORM GROWTH MINDSET: THE TRUTH ABOUT YOUR BRAIN

Explore growth mindset with Thinky Pinky as he takes you through a exploration of what happens in your brain when it learns. This video is part of the Growth Mindset

Curriculum available with LearnStorm, a back-to-school program aimed at helping students start the school year strong. WATCH THE VIDEO...

20

23 IDEAS FOR SCIENCE EXPERIMENTS

USING PLANTS

The following plant project ideas provide suggestions for topics that can be explored through experimentation. READ MORE...

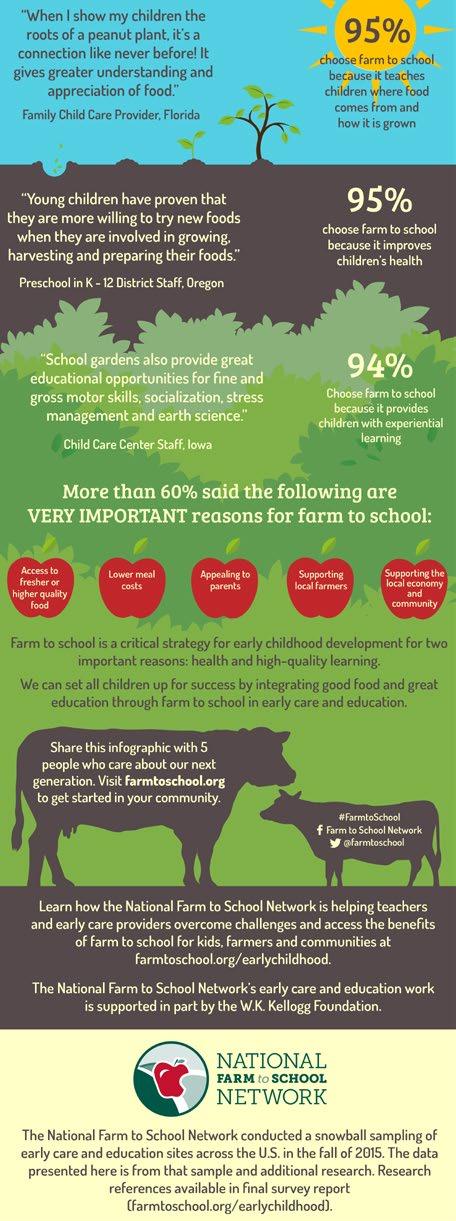

AMAZON BOOKS Click the cover to learn more.

21

Join Alex & host Gilbert Cadiz to learn about how you can encourage your student to build a growth mindset. LISTEN TO THE PODCAST...

Resource Corner (cont.)

23

CREATING OPPORTUNITIES FOR UNSTRUCTURED PLAY

When schools make space for free play in a natural environment, students are left to their own devices to build, create, and problem-solve—and the benefits continue once they are back in the classroom. WATCH THE VIDEO...

24

Resource Corner (cont.)

STRATEGIES FOR RETAINING TEACHERS OF COLOR AND MAKING SCHOOLS MORE EQUITABLE

Imagine – just for a moment – going through your entire K-12 experience without seeing a teacher that shares one of your most significant identities. READ MORE...

25

Click the cover to view on Amazon.

If You Water It, It Will Grow

Play is back and needed in a big way! The students in our classrooms today have much different needs than the students of 10, 15, and 20 years ago. With an uptick in social-emotional behaviors and less time spent with families, play has taken root in kindergarten classrooms and even sprouted into first grade.

Rototilling the Soil

If you walked into PH Miller Elementary seven years ago, kindergarten looked like a high school for 5-year-olds. Play had been stricken from daily activities and replaced with what some would say, was rigorous instruction for high academic achievement. There were several different prog rams teachers were following and all were separate from each other.

One day at a meeting with the kindergarten teachers, they asked, “How are we supposed to rate the students’ development of sociodramatic play on the KIDS assessment if we are not playing?” As the principal and I began to learn about the school in our first year, we become familiar with the Kindergarten Individual Development Survey (KIDS). We noticed how the assessment looked at the whole child through evidence from observation and the measures were developmentally appropriate for 5 and 6-year-olds. Remember, the 5-year-old brain has never changed, it

26 Article

Melissa Crisci

still develops the same way it always has. The answer was to meet the kids where they were and bring play back. Our minds were worn and trodden by ‘No Child Left

As we began to implement play, we were shocked to find that a vast majority of kids did not know how to play. Yes, from not being able to pretend to play

Behind’ mandates and our practices were dormant. But as soon as we started to overturn our previous beliefs, the culture was fertile for new ideas and practices.

Planting the Seeds

The kindergarten teachers erupted with clapping as the principal announced at a faculty meeting that we are bringing play back! We started digging into our own basements and asking for donations of kitchen sets, blocks, matchbox cars, and anything we could use to at least provide students with “play time” during the instructional day. Little did we know these seeds would grow into a whole garden we could have never imagined. We began educating ourselves about play in the classroom by reading books, taking classes, visiting other districts, and redesigning our classrooms to make way for play areas. A three-year plan was developed by a team of teachers in grades K-2, the principal, and myself at the Teach to Lead Summit.

“house” in a home living area to building a structure with blocks. We had to put some stakes in the ground and scaffold how to play by taking on the role of a mom in the play area or the customer at the grocery stand, helping them take turns with cards and blocks, and asking questions about what they were doing during their play. We knew we had a big field ahead of us, but we were determined to get it sown.

The Drought

Right as the momentum for playing in the classrooms was building, COVID hit. We had to remove all the toys, baby dolls, blocks, and anything that students played with. Even though students could not engage in play, new sprouts began to emerge with the first-grade team. They had been hearing about the benefits of play and wanted to learn more about the KIDS assessment. Soon, we were dissecting the IL Early Learning Standards and writing progressions that would be used to rate students’ abilities

27

As we began to implement play, we were shocked to find that a vast majority of kids did not know how to play.

If You Water It (cont.)

throughout the year. Grappling with how to integrate the necessary skills, and building language and background knowledge for students, particularly English Language Learners, play and content-based units began to enter the discussion. Before we knew it, with a little wind to carry seeds, play had been planted in first grade!

As we emerged from the drought of COVID and opened boxes that resembled time capsules, we had to start soaking the seeds to get the plants growing. Soon we found that play was more than just a “time,” in the day, it was a method we could use for teaching foundational skills kindergarteners needed in a way that was developmentally appropriate and authentic. Not only could play-based

Here Comes the Sun

As an instructional coach, my job is to provide professional development, support teachers along their path of best practices in instruction, ensure we have a viable curriculum, and analyze the data. Play-based instruction is not easy, but when we sit back and remember that the standards are not the curriculum, but an endpoint, we can choose whatever path we want to get there. We dug into our science and social studies standards and used those as the foundation for our units and integrated math and literacy skills into the play. Teaching this way allows for the sun to shine much brighter by teaching the standards crosscurricular instead of isolated lessons throughout the day. The assistant

instruction be a way to teach academic learning goals but it could strengthen the social-emotional development of students. But how do we add all of this into our day? How do we convert worksheets from a prescribed curriculum and turn them into play? We definitely needed to rototill our mindset from teacher-directed instruction to studentled learning and growing.

principal and I wrote a grant for funds to continue moving play-based instruction forward and one sunny day, the assistant superintendent visited one of our firstgrade classrooms to experience playbased instruction and was astonished at the learning taking place. Before long she was reallocating funds so we could continue to water our garden! I began a focus group called, Prepared to Play. As

28

We definitely needed to rototill our mindset from teacher-directed instruction to student-led learning and growing.

with our students, our teachers are all on their own path to play and it is my job to meet them where they are. I provided information and resources and then teachers headed back to their gardens to implement what they soaked in about play.

Walking into our classrooms five years ago looked much different than today. Now you will see students counting down for lift-off in a rocket to the moon,

students are blooming in their critical thinking skills, writing, and reading ability. They are growing by leaps and bounds, building background knowledge and language. In analyzing one of our firstgrade classrooms that is integrating math and literacy into play, the percentage of projected growth met on the MAP assessment was 112.9% in math and 136.4 % in reading from fall to winter. Another teacher in kindergarten, who uses play as a method for math concepts,

sorting, measuring, and weighing rocks and then writing about what they found while in space instead of measuring a drawing of a pencil on a worksheet. You might walk into a room and spot students fishing for power words while studying life in the 1800s, building a home for their pet out of blocks after researching what kind of habitat and food the animal likes, or waiting on customers and even delivering the mail from the classroom post office while learning about places in the community.

Beautiful Blooms

I know what you are thinking. With all this play and not enough academics how will these students ever be ready for the next grade? Well, play is the work of children and the data doesn’t lie! Our

began the year with 32% of students in tier 3 on the Aimsweb assessment, and by winter scores had decreased to 10% of students in tier 3. Our data is living and breathing proof that play-based instruction is the fertilizer that will allow students to bloom, creating bright, critical thinkers, preparing them for life.

We have been sharing our seeds with others as well. This past December I presented at the Multilingual Illinois conference on how to build language through dramatic play and presented a session with another teacher about playbased learning in K-2nd grades at the DKG conference in April. We have hosted several visitors from other districts who want to learn about play and Senator Cristina Pacione-Zayas who wanted to

29

...play is the work of children and the data doesn’t lie!

If You Water It (cont.)

learn about how we are using assessment through play. We have been featured in the Illinois state video, “Kindergarteners Learn Best Through Play,” and I came full circle in March by being a critical friend for another school district wanting to implement play-based instruction, at the 2023 Teach to Lead Summit.

Being a gardener in our school is all about rolling your sleeves up, getting dirty, and digging in, doing the hard work. It requires patience, imagination, and planning to see the fruits of your labor (growth of the students). You have to be willing to let go of being the sage on the stage to become the guide on the side and let the students lead. Playbased instruction is what kids need in our schools today. And all good gardeners know, once you’ve planted the seeds and added the fertilizer, all that’s left is to water it and it will grow.

Melissa Crisci is in her 24th year of education. She taught for ten years in elementary grades, was a PreK-8th grade administrator for seven years, and is currently an Instructional Coach in Plano CUSD #88 for all subjects in general education, blended and dual language classrooms. Melissa has been featured in ISBE’s video “Kindergarteners Learn Best Through Play,” served as a critical friend for another district at the Teach to Lead Summit for play-based instruction in K-2, planned content-based units of study with play-based methods, hosted several visitors from other districts including state senator Cristina Pacione-Zayas and received the KIDS VIP award. She holds two master’s degrees; one in Teaching and Learning and another in Administration, as well as an ESL Endorsement. Curriculum design, play & inquiry-based instruction, authentic learning experiences, and formative assessment are a few of her areas of expertise.

30

WATCH THE VIDEO Kindergarteners Learn Best Through Guided Play

PD On - Line

Topics:

Research-Based Instructional Strategies for Emerging Bilinguals in the Dual Language Classroom

Rocio del Castillo

Student Engagement

Elementary

Monique Belin

Middle & High School

Greg Urbaniak

Creating a Culture of Conversation in an ELA Classroom

Chris Wagner

Data-Based Decision

Making for Better Learning

Terry Mootz

Perfect for SIP Days, Faculty meetings, PLC Sessions

Building use cost: 1 Showing $150. Multiple Showings: $299. EachTopic

Package of 3 topics for Multiple Showings: $499.

Teachers, contact us for your own personal viewing at reduced costs.

45 - 60 minute video sessions that: Inform Promote discussion

Are ready to useTomorrow

Are Asynchronous

VIDEO PD FOR SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT

CLICK HERE TO PURCHASE

The Wants and Needs of a Novice Gardener/New Teacher

Judy Kmak Background

For the last few years, I have had the privilege of working with 100 new teachers prior to their first day of school. I value their feedback and know the importance of making sure I am meeting their needs throughout our staff development time. During my work with these educators, I surveyed their wants and needs to determine the best way I could support them throughout the first year of teaching.

How Does Your Garden Grow?

Many of these teachers were not new to gardening. In fact, a number of them had several years of growth and decided to test out the soil in another field. However, all of them were novice gardeners in their new plots of land.

Prior To Planting (The Wants)

In July, I surveyed a group of 30 new staff members from a variety of school districts. I wanted to know if they were assigned to a mentor. The answers varied, depending on the district and the teaching experience they brought to the new district. I asked them to complete the statement, “I feel that the most important role of a mentor is to . . .” The chart on the following page shows their responses to this open-ended statement.

32 Article

to know if they were assigned to a mentor. The answers varied, depending on the district and the teaching experience they brought to the new district. I asked them to complete the statement, “I feel that the most important role of a mentor is to . . .” The chart below shows their responses to this open-ended statement.

It doesn’t surprise me that the new gardeners weren’t thinking about assistance in the areas of curriculum, procedures, and weekly check-ins. When interviewing potential new staff, we delve into their background and experience. Many curriculum questions are targeted to determine their skill level. We ask how they organize themselves for long-term and short-term planning. Districts have confidence in who they hire to match the open positions and the recently hired staff members have selfconfidence in their ability to do the job.

It doesn’t surprise me that the new gardeners weren’t thinking about assistance in the areas of curriculum, procedures, and weekly check-ins. When interviewing potential new staff, we delve into their background and experience. Many curriculum questions are targeted to determine their skill level. We ask how they organize themselves for long-term and short-term planning. Districts have confidence in who they hire to match the open positions and the recently hired staff members have self-confidence in their ability to do the job.

members wanted someone they could trust. They wished for a relationship built on mutual respect before tackling more difficult questions.

However, 43% of the 30 new teachers said that they were hoping for a mentor who would support and encourage them and 30% wanted their mentor to be a resource and collaborator. 16% wanted an individual they could rely on to answer all of their questions and be their go-to person. 10% felt that a mentor should be willing to share ideas and suggestions. This data tells me that the new staff members wanted someone they could trust. They wished for a relationship built on mutual respect before tackling more difficult questions.

However, 43% of the 30 new teachers said that they were hoping for a mentor who would support and encourage them and 30% wanted their mentor to be a resource and collaborator. 16% wanted an individual they could rely on to answer all of their questions and be their go-to person. 10% felt that a mentor should be willing to share ideas and suggestions. This data tells me that the new staff

If you consider yourself a gardener, think about the first time you wanted some flowers near your front door. Did you seek out curriculum assistance such as books or websites about plants? I didn’t think about the procedures in my planning. I wasn’t concerned with those weekly check-ins with my garden to do the weeding. The local gardening center was my resource, and I got lots of ideas by examining the pots that were already put together with a variety of plants and colors. The thing I was looking for the most, was for people to notice the colorful combination I chose for the pots at the front door. This was my moral support and encouragement as a novice gardener. These are the same things new teachers hope to obtain from their future mentor.

33

Comment # of new staff who listed this in their comments % of new staff who listed this in their comments Moral Support/Encouragement/Listen Non-judgmental 13 43% Resource/Collaboration 9 30% Answers to all my questions/Go-To Person 5 16% Ideas/Suggestions 3 10% Curriculum Assistance 0 0% Procedures 0 0% Weekly Check-Ins with the Mentor 0 0%

1

After Planting (The Needs)

In a local school district, I worked with 70 new hires over a period of 2 years. Each of these staff members was assigned to a mentor who would assist them throughout their first year, regardless of their previous teaching experience and position. In the month of October, I asked them to complete the statement, “The most helpful part of working with my mentor has been…” The chart below shows their responses to this open-ended statement.

working with their mentor was receiving answers to their questions and having a go-to person. They had transitioned their time together into the educational program and focused on curriculum assistance (13%) and valued their mentor as a resource and collaborator (19%). Both Procedures (11%) and Weekly Check-Ins (4%) became a priority.

New staff members indicated that curriculum assistance, procedures, and weekly check-ins were more important once the mentor began to assist them. They began to dig deeper as a team to build skills in their area of expertise.

If you consider yourself a gardener, think about the first time you wanted some flowers near your front door. Did you seek out curriculum assistance such as books or websites about plants? I didn’t think about the procedures in my planning. I wasn’t concerned with those weekly check-ins with my garden to do the weeding. The local gardening center was my resource, and I got lots of ideas by examining the pots that were already put together with a variety of plants and colors. The thing I was looking for the most, was for people to notice the colorful combination I chose for the pots at the front door This was my moral support and encouragement as a novice gardener. These are the same things new teachers hope to obtain from their future mentor.

AFTER PLANTING (The NEEDS)

After a few months of experience in the new district, these teachers had needs that looked different from the wants of a new staff member prior to meeting their mentor. They were getting the moral support and encouragement from their mentor and had moved into a relationship that contributed to meeting their needs.

The data shows that 39% of the 70 new teachers said the most helpful part of

In a local school district, I worked with 70 new hires over a period of 2 years. Each of these staff members was assigned to a mentor who would assist them throughout their first year, regardless of their previous teaching experience and position. In the month of October, I asked them to complete the statement, “The most helpful part of working with my mentor has been…” The chart below shows their responses to this open-ended statement.

Now that I consider myself an experienced gardener, I reflect on what I did last year that made my plantings successful. The drought-resistant flowers were exactly what was needed in a spot that never gets shade. I did seek out books and websites to find out how I can get more of those. I read the suggestions about how far to separate each plant

After a few months of experience in the new district, these teachers had needs that looked different from the wants of a new staff member prior to meeting their mentor. They were getting the

that

34

Novice

Teacher (cont.)

Gardener/New

Comment

of new staff who

this in

comments

of new staff

this in their comments Moral Support/Encouragement/Listen Non-judgmental 0 0% Resource/Collaboration 13 19% Answers to all my questions/Go-To Person 27 39% Ideas/Suggestions 10 14% Curriculum Assistance 9 13% Procedures 8 11% Weekly Check-Ins with the Mentor 3 4%

#

listed

their

%

who listed

into relationship

moral and from their and had moved

and how much each type would spread. Now it was critical to think about those weekly check-ins with my garden and find someone to water the plants when I was on vacation. The curriculum, procedures, and weekly check-ins became my priorities. These are the same things that the new teachers were looking for after their relationship had blossomed.

Successful Gardening (The Demands)

I’ve been gardening for a while and thought I had everything figured out. However, I didn’t consider that my neighbors would remove a tree that would cause my shade plants to wilt and die. I wondered why my daffodils were not as plentiful as in previous years. Revisiting my resources answered many of my questions that allowed me to change and modify my garden.

What this teaches us, is that we can successfully grow a garden each year as we develop and refine our skills. The tools I utilize now are very different from those I used as I was learning the basics. My priorities have shifted as I return to the same garden each year with a renewed level of excitement.

I know that we can apply this to what staff members encounter each year, even if they are returning to the same garden. I wonder if second and thirdyear “new” staff continue a relationship with their mentor. I’m sure they utilize other people as resources as they learn about their colleagues’ strengths and draw from their knowledge. The greatest thing we can hope for is that new teachers remember the relationship they had with their mentor and share their gardening expertise to nurture others in the field of education.

Dr. Judy Kmak has implemented new teacher orientation programs in multiple school districts and has coached hundreds of teachers as an administrator. Throughout her career she focused on student engagement, professional collaboration, and community partnerships. Judy currently works with mentors and new teachers as they work together to expand their teaching skills.

35

MORE INFORMATION

Redefining and Reinventing Strategic Planning

On July 1, 2019, I arrived at Community Unit School District 200 to serve as the Assistant Superintendent for Educational Services. At that time, the Vision 2022 Strategic Plan was in its first year of implementation, and I was excited about the work outlined for the district. Eight months later, those plans were put on hold to design pandemic learning. The challenges of the pandemic persisted, and soon enough, the reality that Vision 2022 was sunsetting and the time had come to create a new strategic plan. We knew that our organization had entered a new normal, and we could not just pick up from where we were before the pandemic. Instead, we needed to reimagine, redefine and reinvent (Sneader & Singhal, 2020).

Before March 2020, our leadership team had engaged in a comprehensive and inclusive process involving multiple stakeholders, including teachers, students, parents, and community members, to ask what qualities and skills our students should have when they graduate. What emerged from this work was a Portrait of a District 200 Graduate.

The Portrait of a Graduate for District 200 includes four core components:

• Effective Communicators

• Collaborative Learners

36 Article

Melissa Murphy

• Resilient Learners, and

• Effective Problem Solvers. With these four core components, the central focus is Academic Excellence. The Portrait of a Graduate became the centerpiece of our strategic plan and the moral purpose of deep learning for all students (Fullan & Quinn, 2016). Next, we needed to develop the roadmap to achieve the Portrait of a Graduate. Since

school programming, and high school programming. Then within each of those systems, each building leader designs the goals and direction for their building.

Emerging from the pandemic allowed us to hit a reset and reimagine how to address the urgent needs best sitting in front of our educators. Throughout the pandemic, our organization pulled together to work in a more united manner

the needs of our students were more significant than ever before, we knew our next strategic plan, Vision 2026, had to create a roadmap that ensured we would reimagine educational opportunities for our students and create a clear and focused direction for our organization system-wide.

Building Coherence

District 200 is a large unit district with twenty schools serving students in early childhood through transitional special education programming. Large unit school districts are complex systems and can naturally fall into the habit of working as separate units, early childhood programming, elementary programming, middle

to address the common and urgent complexities of the time. We found incredible value in breaking down the silos of individuality and pulling together to work horizontally and vertically to create a shared focus. With the development of Vision 2026, the importance of a focused system with a shared depth of understanding and purpose to create coherence was valued more than ever before (Fullan & Quinn, 2016).

Therefore, our Vision 2026 strategic plan identified six broad strategies tied to Academic Excellence to achieve our central mission of the Portrait of a Graduate.

1. Implement learning acceleration strategies and programming.

37

We found incredible value in breaking down the silos of individuality and pulling together to work horizontally and vertically to create a shared focus.

2. Design and implement a balanced assessment system.

3. Develop implementation resources aligned with our Portrait of a Graduate.

4. Expand programming to prepare students for a full range of postsecondary opportunities.

5. Develop a comprehensive professional learning program and support system for staff.

6. Support the social and emotional needs of students.

Monitoring Progress to Ensure Accountability

An organization must have a clear strategic plan with well-defined outcome metrics and strategies. In the case of Vision 2026, the district’s Citizens Advisory Committee played a crucial role in providing feedback on the Vision 2022 Data Dashboard, which resulted in a redesign to better align with the six strategies and provide more clarity on how success would be measured.

Working with ECRA Group, the district operationalized our strategic plan and dashboard to communicate more effectively. The Vision 2026 Data Dashboard contains more specific measures to communicate the goals and

progress for academic excellence. The outcomes have clear targets to achieve by the end of the 2025-26 school year. The data dashboard serves as the glue to focus the organization’s direction.

Overcommunicating for Clarity

Once the District 200 Vision 2026 Strategic Plan and Dashboard were finalized, we were proud of the visual look. Creating something consumable and straightforward for our stakeholders was essential, but we knew more than just having glossy and sharp documents would be needed to ensure success. We knew this needed to be more than just a document but a guide to redefine and reinvent learning for the next four years.

Therefore, our Senior Leadership Team committed to overcommunicating our priorities. We studied the work of Patrick Lencioni and knew that we needed to remind our people of the direction we are headed often (Lencioni, 2012).

For my role as the Assistant Superintendent for Educational Services, charged with all things teaching and learning, we selected three key strategies, College and Career Readiness (Strategy 4), Accelerating Learning (Strategy 1), and Balanced Assessment (Strategy 2), to concentrate our efforts. The phrase “Catch a Cab” was

38

(cont.)

Strategic Planning

developed to help our leadership team to remember these three big priorities.

I use multiple structures to serve as what Lencioni calls the Chief Reminding Officer to overcommunicate the Catch a CAB focus (Lencioni, 2012). These include monthly newsletters to staff, monthly newsletters to administrators, monthly administrative teaching and learning meetings, and weekly meetings with instructional coaches. Each venue focuses only on implementing the Vision 2026 Strategic Plan and the priorities with the “Catch a CAB” focus.

Creating a Collaborative Culture to Achieve Success

Creating coherence to ensure the strategies laid out in our plan would be implemented to the fullest intent, our system focused on creating a collaborative culture (Fullan & Quinn, 2016).

One of the biggest game changers in creating coherence and collaborative work for learning acceleration has been the adoption of high-quality instructional materials. This year, in grades K-8, our staff is implementing a new math curriculum aligned with our Portrait of a Graduate components. This curriculum adoption has served as an

anchor to create collective leadership efficacy across the system (Donohoo, 2021). At the leadership level, teaching and learning meetings focus more on a collective purpose.

Collective efficacy has also increased across our district by focusing on collaborative professional learning. Over the last year, our elementary leaders have studied the science of reading to build expertise. Taking the time to learn together has created a common, unified sense of urgency. As our teachers learned more, it resulted in a request to secure new instruction materials for ELA as quickly as possible, even on the heels of the adoption of math. We are now engaged in a pilot of high-quality instructional materials for ELA, and the use of those materials has expanded to classrooms beyond the pilot teachers because of the knowledge gained by our staff through collective professional learning.

Lastly, creating a commonly developed approach has resulted in success. For example, our Career Pathways work has laid out a four-year plan to focus on further developing one pathway at a time. Narrowing the focus to a

39

At the leadership level, teaching and learning meetings focus more on a collective purpose.

specific pathway at a time has allowed for a concentrated and dedicated focus. This year’s focus was on the Education Pathway, which included the addition of dual-credit programming and an internship that has included each of our buildings having a mentor to support our sixty-five students enrolled in the course. While this work is meaningfully taking shape for students, our staff is working on the IT Pathway and creating unique and meaningful student experiences.

Concluding Thoughts

Creating a strategic plan is just the beginning for an organization, but the power comes in how to bring that plan to life. Just one year into the Vision 2026 Strategic Plan, our staff has reported having a clearer sense of where we are going and a stronger sense of how our plan will impact students and staff. The difference-maker for us has been building coherence, creating clarity for our outcome measures, overcommunicating the work, and creating a collaborative culture that has resulted in collective efficacy. Not only does our organization have a clear sense of the work, but it has also significantly impacted our students. With this trajectory, we are certainly on track to redefine the next normal for our students (Sneader & Singhal, 2020).

References

Community Unit School District 200. (2022). Portrait of a Graduate. https:// www.cusd200.org/Page/17867

Community Unit School District 200. (2022). Vision 2026 Strategic Plan.

https://www.cusd200.org/vision2026

Donohoo, J. (2021). 10 Mindframes for Leaders. Corwin

ECRA Group. (2022). Strategic Dashboard Community Unit School District 200

Fullan, M., & Quinn, J. (2016). Coherence. Corwin

Lencioni, P. (2012). The Advantage. Jossey-Bass

Sneader, K & Singhal, S. (2020). Beyond coronavirus: The path to the next normal. https://www.mckinsey. com/featured-insights/leadership/ the-future-is-not-what-it-used-tobe-thoughts-on-the-shape-of-thenext-normal

Melissa Murphy serves as the Assistant Superintendent for Educational Services in Community Unit School District 200. She has been fortunate to work for twentythree years as a teacher, instructional coach, elementary principal, and assistant superintendent. Mrs. Murphy is passionate about creating high-quality instructional experiences for all students.

40

Strategic Planning (cont.)

Cultivating Student Growth Through

Instructional Coaching

As a small rural community in northern Illinois, we are no strangers to cultivating the land in order to produce quality crops. This year, North Boone CUSD 200 embarked on a journey to cultivate student growth through Instructional Coaching. We hired four instructional coaches for our six schools, and have implemented student-centered coaching, based on Diane Sweeney’s model, and our efforts are already producing strong results.

Preparing the Soil

In the Spring of 2022, I started the process of building an instructional coaching program in the North Boone School District. I knew that this would be no small feat, having previously worked in districts that had started instructional coaching programs. I knew that to be successful, I would need to implement an instructional coaching program that supported student growth and learning while also supporting teachers in their instructional practices. I knew that if I wanted instructional coaching to take root in our district, I would need to prepare our teaching and learning soil before I could plant the coaching seeds.

41 Article

Kari Neri

Instructional Coaching (cont.)

I wanted our coaching program to include coaching cycles, and I wanted student learning to be front and center. In order to meet these goals, I developed our coaching program around the pillars of Diane Sweeney’s Student-Centered Coaching model. I focused on partnering with building leadership to hire a strong instructional coaching team. The four coaches we hired were from our own district, so we were excited that we were able to “grow our own,” so to speak.

Planting the Seeds

Over the summer, I focused on planting the seeds for a successful first year of instructional coaching. In June, our four coaches started an online course introducing them to Sweeney’s studentcentered coaching model. The same month, I met with our building principals to prepare them on how to create a culture for coaching. Taking direction from Leading Student-Centered Coaching (Sweeney, 2018), we focused on creating a “no optout” culture, on keeping evaluation separate from coaching, and on making it clear to staff that the coaching model is valued. Principals dug into the

Checklist for Getting Coaching Cycles

Up and Running and focused on Stage 1: Calibrate with the Principal (Sweeney, 2020). I wanted our principals to have a strong sense of the student-centered coaching model, and I wanted to provide them the time to brainstorm and problemsolve as an administrative team.

In August, I hosted a principal/coach planning session so they could plan how they were going to kick off coaching at the start of the school year. Each principal/coach team discussed what would work best for the individual building, and they developed a kick-off presentation for institute day. Giving our principals and coaches this opportunity allowed them to determine how best to plant coaching seeds in their buildings, and where to focus their attention as the year began.

Watering for Growth

As we started the school year, the coaches and I were planning on coaching cycles starting by October 1st. I wanted the coaches to have time to plant those coaching seeds in their buildings, and we thought it would take the whole month of September to make that happen. To our surprise, that wasn’t the case! We had teachers signing up for coaching cycles in early September, and coaches were able to hit the ground running.

42

In their cycles, coaches focused on supporting teachers in selecting a standard, pre-assessing that standard, focusing instruction on students’ growth to proficiency, and post-assessing that standard. Using Sweeney’s ResultsBased Coaching Tool, our coaches kept their coaching conversations on student growth and partnered with teachers to support student learning (Sweeney,

those who were celebrated through the Teacher

Spotlight.

Producing Crops

At the end of January, I pulled our coaching data as a mid-point benchmark during the year. The coaches and I were already excited about the success of the individual coaching cycles, and we were anxious to see our impact. We were

2020). The growth we saw during those first coaching cycles was beyond our initial expectations, and other teachers started to notice the impact coaching was having on students.

As the first part of the year went on, we wanted to build more understanding around the coach’s role as well as celebrate teacher success. We decided to create a monthly newsletter, titled “Instructional Coaching Connection,” where we would give instructional tips and where we would celebrate teachers through a Teacher Spotlight. This turned out to be a great way to water the seeds the coaches were planting in their buildings. The newsletter created a buzz in our buildings, and teachers congratulated

ecstatic to see that as a team, we were reaping the benefits of careful planning.

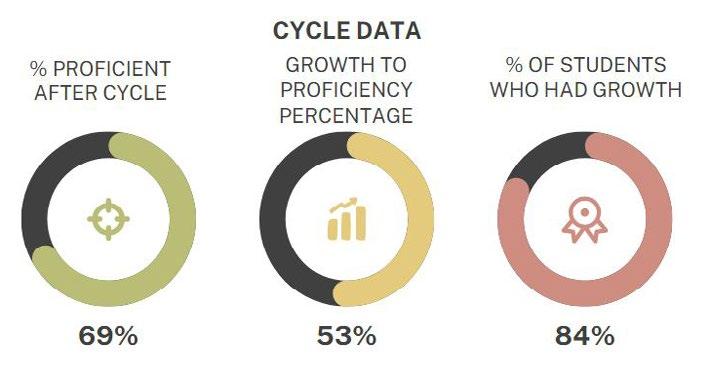

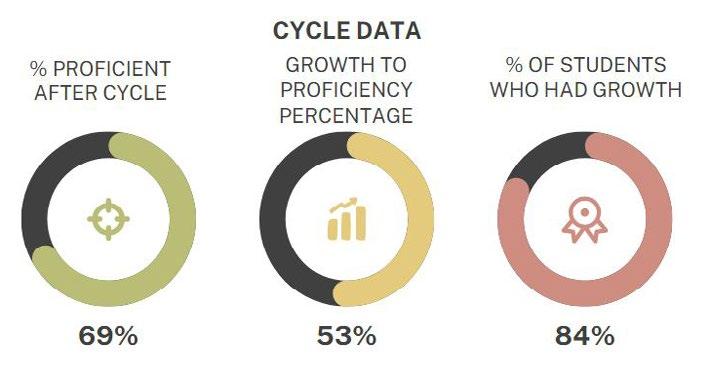

Collectively, the coaches were in coaching cycles for almost the same amount of cycles they had already completed (see Figure 1 on the following page). This showed us that our watering for growth efforts were working as we had almost doubled our cycles. Additionally, our combined cycle data showed us that our model was having an impact on student learning. Figure 2 on the following page illustrates that after completing fourteen cycles, 69% of our students were proficient in the standard(s) measured during the cycle, while 53% of our students grew to proficiency during

43

We decided to create a monthly newsletter, titled “Instructional Coaching Connection,” where we would give instructional tips and where we would celebrate teachers through a Teacher Spotlight.

those cycles. Even more exciting to us was the percentage of students who had growth during the cycles, which totaled 84%. So, even if students did not reach proficiency, 84% of them were making progress toward proficiency.

Seeing this collective impact made our team proud of the work happening in our buildings. After analyzing this data, we started thinking about how we could expand our program in order to reach more teachers and students.

Cultivating New Land

During the second half of this year, our coaches have expanded their reach. Our two elementary coaches are using Professional Development Boxes to find new ways to work with teachers. When a teacher signs up, that teacher

receives a PD Box with a new strategy, along with some incentives and snacks. The coach either observes the teacher using the new strategy or debriefs with a teacher after using the strategy. For their first round, our coaches worked with 13 teachers. Our two secondary coaches have taken a different approach but with similar success. One has created “PD under 3” videos that he sends to staff weekly. These PD videos under three minutes provide an explanation of a strategy, examples for multiple content areas, and specific examples of a teacher from our district using the strategy with students. Our other secondary coach creates infographics or handouts for strategies, shares them with teachers, then models the strategy in one of their classes. Both

44

Adjust the Ingredients (cont.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

of these approaches are allowing them to work with new teachers.

For our second year of implementation, we are already planning on cultivating new land for coaching. Our coaches are excited that they have teachers already requesting coaching cycles at the beginning of the school year; so, the seeds we have planted are going to harvest new crops. Next year, we also plan on tracking additional data so we can further measure our impact. We are still in the planning stages of what data to track, but we have brainstormed measuring our impact on coaching teachers in creating assessments, modeling a new instructional strategy, and discussing and analyzing data.

None of this would be possible without our four amazing coaches: Becke, Ben, Mike, and Retha. I am so lucky to have a coaching team that cultivates our teaching and learning soil every day. I can’t wait to see what next year brings!

References

Sweeney, D. & Harris, L. (2020). The essential guide for student-centered coaching: what every k-12 coach and school leader needs to know. Corwin Press, Inc.

Sweeney, D. & Mausbach, A. (2018). Leading student-centered coaching: building principal and coach partnerships. Corwin Press, Inc.

Kari Neri serves as curriculum director for North Boone Community Unit School District 200 in Poplar Grove, IL. She has been in education for more than 20 years and has served as a high school English teacher, a staff developer, and an English language arts curriculum dean before becoming a director.

Steve Oertle

Growing Independent Learners In a Fertile Classroom Garden

Classrooms are often viewed as sterile environments where students sit and absorb information, but what if we started thinking of classrooms as gardens and students as plants? This analogy has the potential to transform the way we view education and the learning process (Baptist, 2002).

Just like a garden, a classroom requires careful cultivation and nurturing. The teacher acts as the gardener, providing the necessary tools and resources for students to grow and thrive. A gardener prepares the soil, plants seeds, waters, and fertilizes them. A teacher prepares the classroom environment, creates a curriculum and lesson plans, provides resources and materials, and guides students in their learning.

While plants need sunlight, water, and nutrients to grow, students require the proper conditions to flourish. They need to feel safe and valued, to have access to resources and support, and to be challenged and encouraged to reach their full potential. Like plants, students come in many varieties, with different needs and strengths. Some may need more support and attention, while others may require more autonomy and independence. A

46 Article

skilled gardener can identify the unique needs of each plant and provide the appropriate care, and a skilled teacher can do the same for each student.

As with any garden, there are challenges and obstacles to overcome. Sometimes plants may not grow as expected, or may be damaged by pests or weather. Similarly, students may face obstacles such as learning difficulties or social and emotional issues. However, just as a gardener persists in finding solutions to these challenges, a teacher can provide the necessary support and resources to help students overcome their obstacles and reach their full potential.

So what are the critical elements that students need to thrive? What are the essential components that create the conditions for optimal student growth? What educational influences are analogous to soil, nutrients, water, sunlight and air? While there are certainly an endless list of strategies and influences that positively impact student growth, there are some, by research and evidence, that have the potential for creating exponential growth and learning in the classroom “garden.” Regardless of each teachers unique style and approach to teaching, all highly impactful classrooms require a guaranteed and viable curriculum, high levels of student voice and choice, relevancy and novelty

that drive student curiosity and regular clarity of purpose and progress.

A GUARANTEED AND VIABLE CURRICULUM - The Soil of the Garden

Just as a rich soil filled with nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium is essential for plants to grow and flourish, a well-designed “fertile” curriculum is necessary for students to develop and thrive. A guaranteed and viable curriculum (GVC) provides that “soil” and sets the foundation for learning with all of the nutrients that help students grow and develop.

With nutrients like

• Essential Standards,

• Essential Questions,

• Learning Progressions and

• Success Criteria, a GVC provides a soil designed to meet the diverse needs of students. When teachers use a well-designed curriculum, they ensure that students have access to a range of knowledge and skills that will help them develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration skills.

Additionally, like a gardener who continually tends to the soil to ensure optimal conditions for plant growth, teachers who consistently evaluate and update the curriculum to meet the changing needs of their students, guarantee optimal growth. By providing

47

a fertile learning environment that is rich in knowledge and skills, teachers can help students grow and develop into strong, healthy, and productive members of society. Gardeners must be knowledgeable and committed to their gardens and

“If schools are to establish a truly guaranteed and viable curriculum, those who are called upon to deliver it must have both a common understanding of the curriculum and a commitment to teach it.”

(Marzano, 2003, p.37)