Amy Warke ILASCD President

I Can See Clearly Now: A New Lens on Education

Welcome to this quarter’s journal, where we embrace the theme, “I Can See Clearly Now.” In education, clarity is more than a moment of insight—it is a way of seeing, thinking, and acting that helps us move forward with purpose. In a world marked by rapid change and increasing complexity, clarity is what grounds us. It enables us to pause in the midst of challenges, to step back from the noise, and to rediscover the values and vision that guide our work.

Clarity does not always come easily. It requires reflection, humility, and the willingness to see with fresh eyes. It asks us to question assumptions, to

Amy Warke, President awarke2008@gmail.com

Scott England, Past President esengland@umes.edu

Amy MacCrindle, President-elect amaccrindle@district158.org

Sarah Cacciatore, Treasurer scacciatore@d75.org

Andrew Lobdell, Secretary lobdella@le-win.net

Debbie Poffinbarger, Media Director debkpoff@gmail.com

Ryan Nevius, Executive Director rcneviu@me.com

Bill Dodds, Associate Director dwdodds1@me.com

Task Force Leaders:

Membership & Partnerships

Denise Makowski, Amie Corso Reed

Communications & Publications

Belinda Veillon, Jacquie Duginske

Advocacy & Influence

Richard Lange, Brenda Mendoza Program Development

Jamie Bajer, Heather Bowman, Scott England, Amy MacCrindle, Terry Mootz, Amie Reed, Dee Ann Schnautz, Belinda Veillon, Richmond Burton, Amy Warke, Doug Wood

open ourselves to new perspectives, and to listen deeply to the voices around us. When we find clarity, we gain not only a sharper understanding of where we stand, but also a stronger sense of where we are going. It is this balance of reflection and forward-looking vision that allows both educators and students to thrive.

Seeing clearly also means embracing transformation. Change, when viewed through a lens of clarity, shifts from being a disruption to being an invitation—a chance to grow, to innovate, and to reimagine what is possible. In our schools, classrooms, and communities, clarity empowers us to see potential where once we saw obstacles, and to recognize that every challenge holds within it the seeds of progress.

Just as importantly, clarity reminds us of the support we need to sustain ourselves on the journey. It is not only about big ideas or distant goals, but also about the daily practices, relationships, and

commitments that keep us steady. Clarity helps us align our actions with our values, nurture our own well-being, and draw strength from one another. When we see clearly, we not only chart our own path but also create the conditions for others to flourish.

As you move through the pages of this journal, may you find inspiration that sharpens your vision, challenges that

stretch your thinking, and insights that renew your sense of purpose. Let this issue remind us all that when we choose to see with clarity—both the present moment and the horizon ahead—we discover not only where we are, but also who we can become as learners and leaders.

Amy Warke, Ed.D. President, IL ASCD

- PD 365

Ryan Nevius ILASCD Executive Director

rcneviu@me.com

As we kick off another fantastic school year, I want to welcome back the dedicated educators across Illinois whose passion leads to meaningful learning experiences for all students. We are grateful for the countless ways you inspire, innovate, and make a difference every day. Cheers to another year filled with endless learning opportunities!

The theme of ILASCD’s fall journal, “I Can See Clearly Now,” feels especially fitting this time of year. Listening to the Johnny Nash classic on Spotify reminds me of the clarity, hope, optimism, and renewal we all crave at the start of a school year. Its lyrics serve as a powerful metaphor for clearing away the clouds, embracing possibilities, and helping students and ourselves thrive.

Building on that theme, we invite you to keep Illinois ASCD in mind as a partner in your professional journey. Together, we can help remove the obstacles in your way, clear the rain, and keep your year feeling like a bright, sunny day.

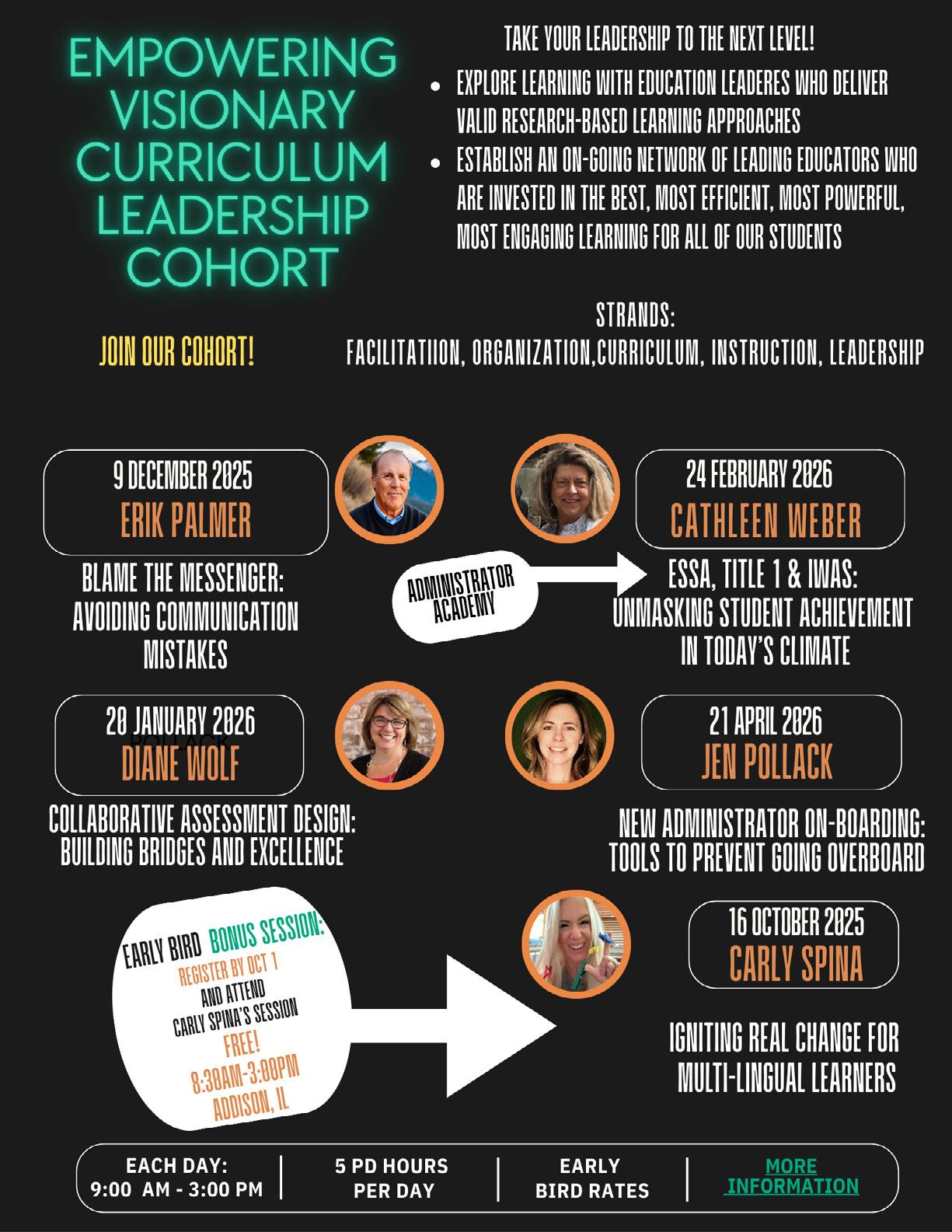

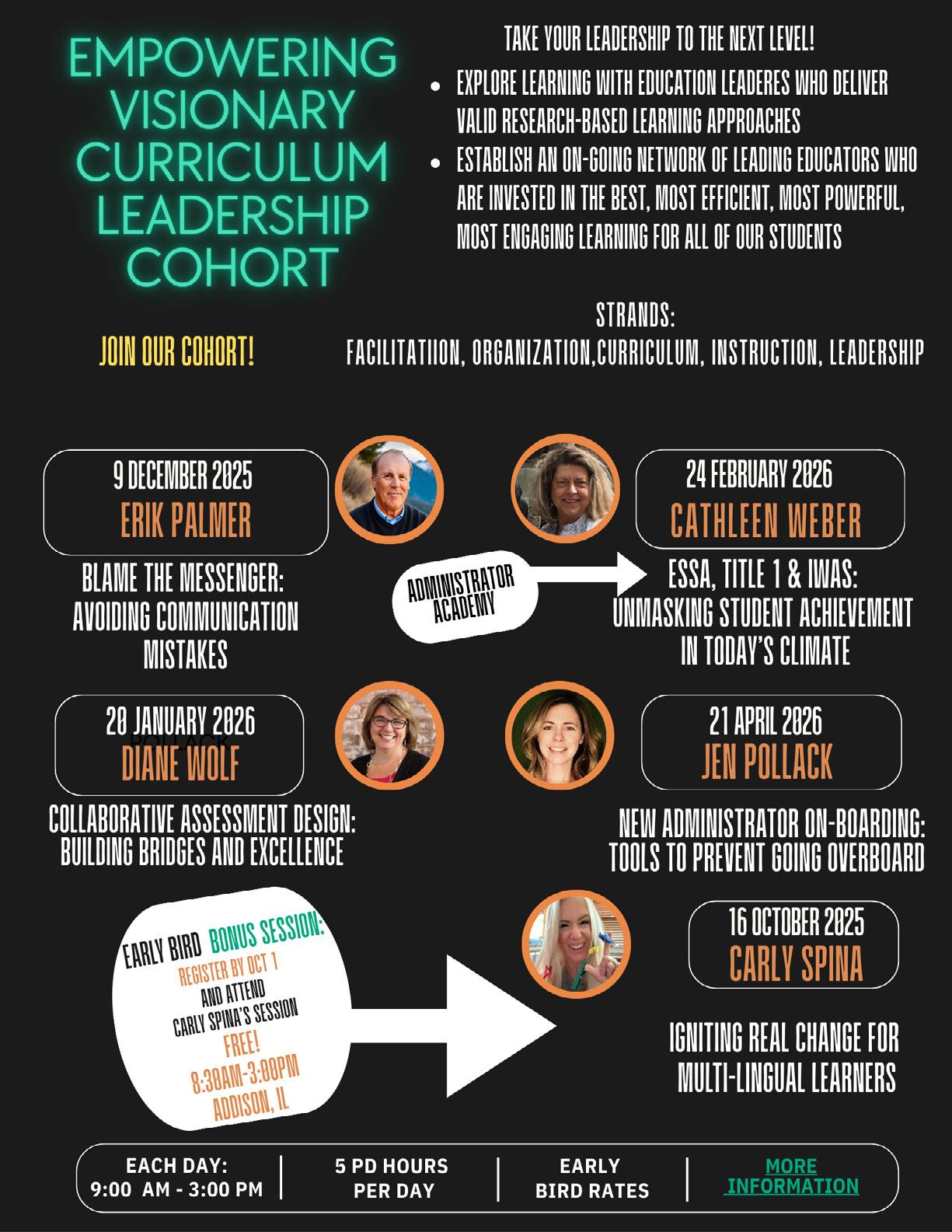

I’m also thrilled to announce that the clouds have lifted on our Fall Professional Development Calendar and the sunshine is bright! This year’s offerings feature a brand-new event we hope will become an annual favorite:

• When: November 5, 6, 12, and 13

• Time: 9:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. each day

• Format: Live and on-demand options to fit your schedule

Vision 365 brings together the most requested topics from last year’s statewide needs assessment, including:

• Math

• PLCs

• Writing

• Burnout

• Literacy

• Restorative Practices

• Absenteeism

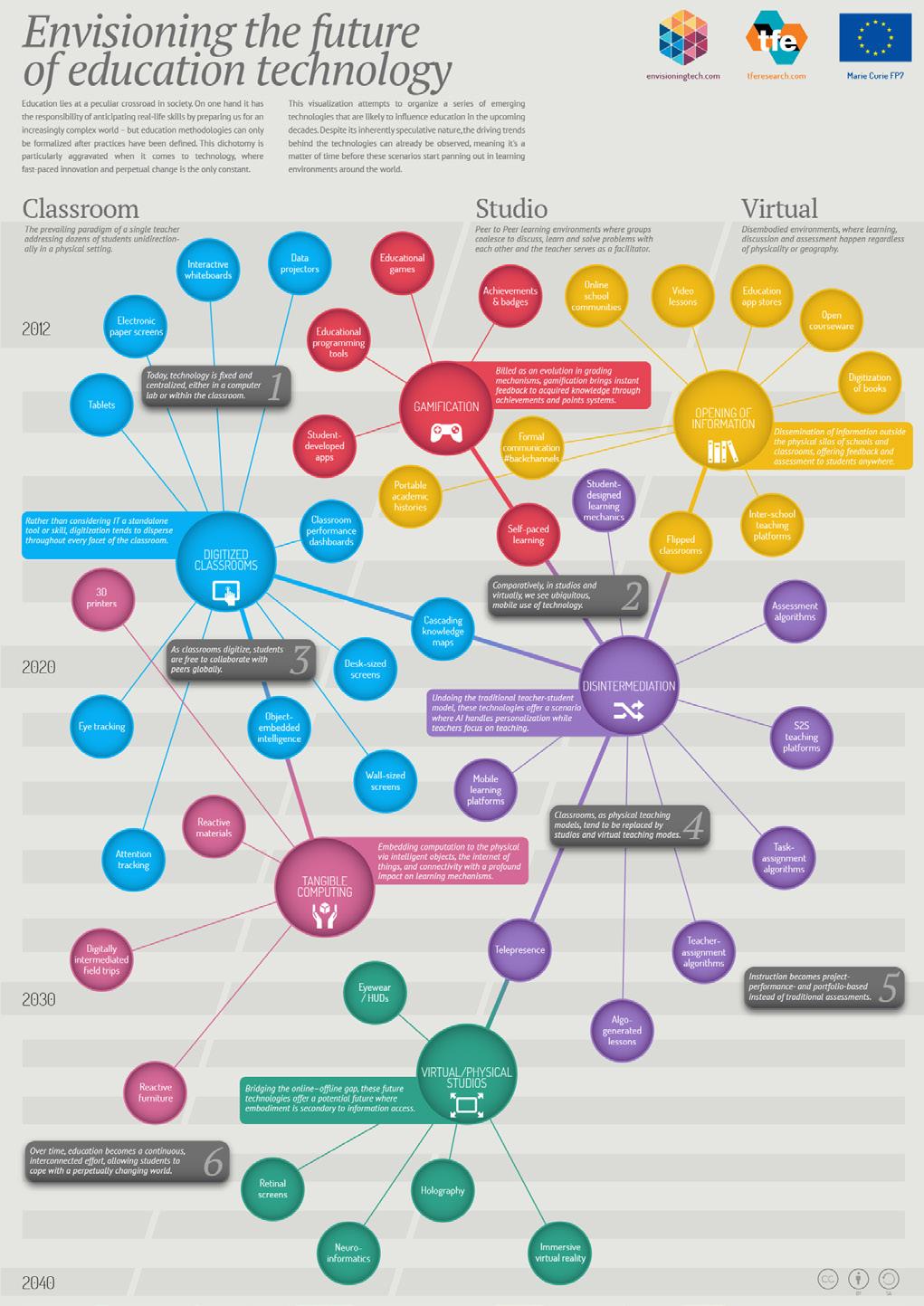

• AI in Education

• Grading

• Communities of Belonging

Our speaker lineup is packed with leading voices in education: Anthony Muhammad, Diane Sweeney, Tony Frontier, Dave Nagel, Ricky Robertson, Ali Hearn, Vanessa Vakharia, and many others.

To ensure budgets aren’t a barrier, we’ve launched a Back-to-School Registration Special with affordable rates for individuals as well as small and large groups.

Join us as we reimagine school improvement, together.

We can’t wait to see how Vision 365 and all our fall professional learning opportunities help clear the path for a brighter future in our schools.

Thank you for the work you do every day to inspire and lead. We look forward to learning, growing, and celebrating success alongside you throughout the year ahead.

When resources are limited, connection is amplified as our most powerful tool.

Across Illinois, and nationally, teacher shortages have become persistent and systemic, affecting not only general education but also critical supports such as special education, mental health, speech, social work, school psychological, hearing, and vision services (National Center for Education Statistics, Dec. 2024). These shortages strain financial onboarding, standard operating procedures, and delivery of services, particularly for students with disabilities. This article draws upon peer-reviewed research and ASCD-based leadership wisdom to explore the impacts of shortages on school leadership and to share lessons learned and lessons in-progress.

The chronic shortages of qualified special education teachers and related service providers continues to be

a major challenge for Human Resource and Special Education Directors. The demand for special education providers remains very high. This can be attributed to the following factors (Gilmour, MasonWillimas, & Bettini, 2024):

• Limited Applicant Pool

• High Turnover and Impacted Stress and Resilience Rates

• Lack of Support from Administration

• The High Workload Variables for Special Education Providers

student outcomes, teacher morale, and organizational culture, forcing principals to focus more on crisis management than strategic vision (Ingersoll et al., 2018; Creagh et al., 2023; ASCD, 2024).

Effective leadership, especially that which fosters trust and positive culture, plays a critical role in recruiting and retaining teachers and other school-based providers (Nguyen, et al., 2024)). Growing workloads has significant consequences, not only for educator well-being but

Teacher and related service provider shortages may destabilize instruction, staff well-being, and school climate, while also significantly altering principal leadership roles and priorities.

Shortages of special education teachers and related service staff members seemingly lead to negatively impacting staff members and the students (Gilmour, Mason-Williams, & Bettini, 2024). Teacher and related service provider shortages may destabilize instruction, staff well-being, and school climate, while also significantly altering principal leadership roles and priorities (see Table 1 for samples). As some are experiencing, shortages negatively affect

also for student engagement and academic performance (Creagh et al., 2023; Will, 2022; Bettini, 2024). For those supporting learners with disabilities, barriers may include maximum capacity of specialized service providers due to shortages (Bettini, 2024).

In typical times, often leaders may lose track of available external resources. Although already valuable, sharing

resources has become crucial. The Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) provides a comprehensive suite of Special Education Technical Assistance Projects designed to strengthen success, inclusive practices, and various student access needs; these align with the Whole Child framework. Several align with more than one Whole Child tenet, however for illustrative purposes, one is shared for each as an example.

Regarding the Healthy tenet, ISBE’s Behavior Assessment Training Project (BAT) supports educators in developing culturally responsive Functional Behavior Assessments and Behavior Intervention Plans that enhance emotional wellness (Illinois State Board of Education [ISBE], 2024). Under Safe, the Autism Training and Technical Assistance (ATTA) initiative equips schools with tools for fostering accessible learning environments through strategies for communication, as well as high school to secondary opportunities/ transition planning for students with autism (ISBE, 2024).

To promote Engaged learning, the Illinois Assistive Technology Program (IATP) and Infinitec provide training, evaluations, and assistive technology services that enable students with disabilities to access curriculum and participate meaningfully in academic activities (ISBE, 2024). Another example

is the Autism Professional Learning & Universal Support Project | Home for effective behavioral and communication supports. Ready-made visual supports for engagement, and social-emotional growth are helpful to any educators, and especially to new teachers and teams.

Within the Supported tenet, the Illinois Elevating Special Educators (IESE) Network focuses on mentoring, leadership development, and family engagement, helping retain early-career special educators (ISBE, 2024). Several on-demand free webinars are available to access. The QualityIEP Project provides clear direction, samples, and structure for educators in developing high-quality IEPs. Specifically for Special Education Leadership looking for advancing knowledge and skills as leaders that support programs, the Special Education Leadership Academy focuses on decision-making, communication, continuous improvement process, and resources/technical supports (ISBE, 2024).

Finally, the Challenged tenet is advanced through the Specific Learning Disability (SLD) Support Project evidenced-based and promising practices, real examples of supports, and free trainings. Also, the Early Choices and STAR NET Early Childhood Inclusive Practices, offers resources for approaches, targeted instruction, and early intervention

resources to close achievement and opportunity gaps to foster equitable academic opportunities (ISBE, 2024). Regarding older learners, the IL Center of Transition and Work provides direction and support in self-determination, work place support, and understanding employment pathways, with the aim to improve employment outcomes.

To address staffing shortages and improve educator retention, consider implementing the following strategies:

• Accelerated Pathways. Explore licensed educator fast-track programs to help staff earn certifications more efficiently. Pair this with quality mentoring.

• Internship Opportunities. Offer districtbased placements, with an emphasis on Multilingual Learners (MLL) and Special Education.

• Competitive Compensation. Use financial incentives to attract and retain talent in hard-to-fill positions.

• Consider ISBE Avenues. Utilize teacher vacancy grants available to districts with the highest number of unfilled positions.

• Enhance Working Conditions.

• Establish structured mentor programs.

• Provide targeted support from

Directors, Principals, HR, and Curriculum leaders.

• Implement a comprehensive onboarding plan for new hires.

• Reduce Administrative Burden. Streamline special education paperwork to minimize extensive compliance requirements.

To strengthen recruitment efforts and promote sustainable staffing solutions, adopt a multifaceted approach:

• Diversify Recruitment Channels. Go beyond traditional postings by leveraging social media, connecting with college field experience site managers, and contacting college department chairs directly.

• Strategic Use of Staffing Agencies. Partner selectively with specialized education staffing agencies for short- and long-term vacancies, ensuring clear expectations and active collaboration.

NOTE - these individuals do not fall on the district evaluation schedule, therefore it is crucial to have a plan for providing feedback and support. Staffing agency personnel may or may not be required to attend professional development sessions or complete

after-school activities. Be diligent in a team approach working with HR and the Chief School Business Official so that someone is thoroughly appraised of the staffing agency contract details.

• Flexible Staffing Solutions. Hiring substitutes and alternative staff may

angle, has provided some improvements. What leaders are living right now may involve several main areas: (a) Finance: Increased costs from contracts and recruitment; (b) Vision: Balancing inclusivity with limited resources, (c) Service Delivery: Ensuring equitable access for students with disabilities; (d) Culture

Educator shortages are policy challenges as much as operational ones.

be a viable solution. This can impact the districts’ substitute pool. The use of substitutes for special education providers requires that a certified special education staff member must lead (i.e., develop/write annual goals, develop lesson plans, and provide progress monitoring support for the substitute, who cannot directly complete such tasks).

• Explore Virtual Options. Evaluate the benefits and limitations of using thirdparty vendors or virtual educators to fill service gaps.

Educator shortages are policy challenges as much as operational ones. Engaging with ISBE and state-wide professional organizations to learn and secure systemic solutions, and explore every

and Climate: Building morale during high turnover (Will, 2022); (e) Student Outcomes: Shortages directly affect student engagement and performance (Darling-Hammond, et al., 2023).

Although challenges remain, leaders and educators power through. Crucial lessons learned/lessons in-progress consistently emphasize connection and clarity. To build capacity, save time from manually learning about resources, and establish connections, the following list includes ideas for new leaders or veteran leaders looking for new ideas.

The ASCD Educational Leadership collection on teacher shortages provides research-driven recommendations for school leaders facing these challenges (ASCD, 2024). Regional

Offices of Education (ROEs), and ISBE professional development and technical assistance supports, such

Assign internal liaisons to onboard and integrate contracted professionals for continuity and quality assurance.

as the QualityIEP Project, and the SLD Project offer onboarding assistance ideas, professional development, and collaborative options. Additional supports include Illinois professional organization networking, and targeted professional learning, such as ILASCD, IAASE, ILPP, IASBO, and IASA.

For contracted professionals such as speech-language pathologists or school psychologists, establish explicit agreements on onboarding, quality monitoring, and integration into school culture. Create contingency plans for performance feedback and support, as many contracted providers operate outside PERA evaluation systems.

Develop comprehensive protocols for early screening of student needs, ensuring timely access to health, behavioral, and academic supports.

Centering leadership decisions around the Whole Child framework (ASCD, 2013) promotes sustainable student success and educator support. For example, begin with the following ideas:

• Healthy: Establish a process to screen students for health and social/ emotional needs.

• Safe: Establish a process to communicate critical information to ensure safe learning environments.

• Engaged: Establish a process to build capacity for teams to maintain student participation and for leaders to connect directly with families (e.g., ParentSquare).

• Supported: Establish a process to offer professional development and wellness supports for practitioners, including a schedule for veteran and new educators’ needs.

• Challenged: Establish a process to

acquire, build fluency, maintain, and generalize professional learning that is evidenced-based and manageable addressing rigorous academic standards, and proven specialized supports.

In typical times and in times of scarcity, connection is key. Leaders who seek local, state, and regional supports, foster partnerships, and advocate for promoting connection and clarity in processes, may better transform challenges. With a Whole Child Approach and connection as your vision, consider:

• In what ways can we connect with the resources available?

• What is working well and where do I need support?

• Have I given myself credit and celebrated all that I have accomplished (individually and collaboratively) in contributing to access, processes, and student success?

• Have I acknowledged where there are opportunities for growth?

• What examples can I share for families to connect healthy, safe, engaged, supported, challenged progress?

ASCD, (2007). Whole child approach to education [tenets]. https://files.ascd. org/staticfiles/ascd/pdf/siteASCD/ publications/wholechild/WC-OnePager.pdf

ASCD, (2013). The whole child approach. https://www.ascd.org/whole-child

ASCD, (2024). Addressing teacher shortages: Leadership strategies. Educational Leadership, 81(3), 1218. https://information.ascd.org/ january-2024-el-topic-addressingteacher-shortages

Bettini, E. (2024). Addressing special education staffing shortages: Strategies for schools [Brief]. EdResearch for Action. 55015-EdResearch-SpecialEducation-Staffing-Brief-31FINAL-1-1.pdf

Creagh, S., Thompson, G., Mockler, N., Stacey, M., & Hogan, A. (2023). Workload, work intensification and time poverty for teachers and school leaders: a systematic research synthesis. Educational Review, 77(2), 661–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/0 0131911.2023.2196607

Darling-Hammond, L., DiNapoli, M., Jr., & Kini, T. (2023). The federal

Table 1 Summary Key Issues, Strategies, and Resources

Key Issues Strategies & Resources

Teacher Shortages Across Specializations

Fragmented Onboarding & Training for Contracted Providers

Financial Strains Due to Staffing Gaps

● Partner with Regional Offices of Education (ROEs) and cooperatives to explore shared staffing models.

● Consider existing projects such as the SLD Project and ISBE programs for professional pipelines.

● Use ASCD’s resources on retaining educators (ASCD, 2024).

● Develop clear onboarding protocols.

● Establish explicit agreements with outside providers on training and supervision.

● Use mentors or liaisons to integrate specialists into school culture.

● Seek grants for high-need areas, such as ISBE Teacher Shortage licensure opportunities.

● Explore cooperative purchasing and staffing agreements to reduce costs.

● Seek existing resources for training, such as the ISBE Technical Assistance projects.

Student Outcomes and Learning Gaps

● Prioritize equitable service delivery to protect academic growth.

● Provide targeted interventions, UDL, differentiated instruction, assistive technologies, and free resources from the ISBE Technical Assistance projects.

● Collaborate with ISBE and professional associations for training and resources.

● Access ASCD’s guidance on maintaining positive culture during staffing crises.

role in ending teacher shortages. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi. org/10.54300/649.892

References

Gilmour, A., Mason-Williams, L., & Bettini, E. (2024). How the special education teacher shortage affects students with SLD. Learning Disabilities

ASCD, (2007) Whole child approach to education [tenets] https://files.ascd.org/staticfiles/ascd/pdf/siteASCD/publications/wholechild/WC-One-Pager.pdf

Association. [U.S. Department of Education Grant R324C240002]. https://ldaamerica.org/howthe-special-education-teachershortage-affects-students-with-ldand-what-to-do-about-it/

Illinois State Board of Education. (2024). Special education technical assistance projects. https://www.isbe.net/ Pages/Special-Education-TechnicalAssistance-Projects.aspx

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., and Collins, G. (2018). Seven trends: The transformation of the teaching force [updated October 2018]. CPRE Research Reports. https:// repository.upenn.edu/cpre_ researchreports/108

Nguyen, D., See, B. H., Brown, C., & Kokotsaki, D. (2024). Leadership for teacher retention: exploring the evidence base on why and how to support teacher autonomy, development, and voice. Oxford Review of Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10. 1080/03054985.2024.2432635

OpenAI. ChaptGPT4.0 [for formatting, table, crosschecking, alignment].

Will, M. (2022). Stress, burnout, depression: Teachers and principals are not doing well, new data confirm. Education Week. https://www.

edweek.org/teaching-learning/ stress-burnout-depressionteachers-and-principals-arenot-doing-well-new-dataconfirm/2022/06

Heath Brosseau is a transformative and servant leader. As Director of Pupil Personnel Services, and program mentor to administrators of special education interns, he brings decades of experience in mentoring new and veteran faculty, leading departments, developing programs, navigating the unexpected, and advancing continuous improvement beyond compliance. Contact Info: hbrosseau@ isd109.org; heathbrosseau@gmail.com

Andrea Dinaro Ph.D., is a Professor of Special Education at Concordia University Chicago, is the Chair of the Division of Curriculum, Technology, and Inclusive Education (CTIE), and Program Leader for special education related doctoral programs. Research interests include assistive technology, disability in the curriculum, specialized curriculum and instruction, special education leadership, and special education preparation program improvement. Contact: andrea.dinaro@ cuchicago.edu

Self-reflection is often spoken about in teacher education programs and faculty development workshops, but in practice, it is far more complex than simply asking, “What could I have done better?” For educators, particularly those navigating emotionally

...sometimes the barrier to clarity is not the student, the material, or the classroom dynamics. It is ourselves.

and intellectually charged topics, self-reflection is a discipline that requires humility, vulnerability, and adaptability (Nduagbo & Cassle, 2023). It involves the ability to pause, assess not just what we are teaching but how we are showing up as teachers, and recognize that sometimes the barrier to clarity is not the student, the material, or the classroom dynamics. It is ourselves.

I say this not to point fingers outward. I say this because I have had to do this work inwardly for most of my life. As a trained therapist, you might assume self-reflection comes naturally to me. In some ways it does. In other ways, it is

as difficult and humbling as it was when I first began learning about it in fifth grade.

I still remember the day vividly. I had just struggled through a math problem, and my frustration was written all over my face. I was someone who felt intense pressure to get it right the first time. When that did not happen, anxiety would creep in and cloud everything else. My teacher could have moved on, but instead, she paused and asked me a simple yet profound question: “Can you tell me what part of the problem you didn’t understand, and what you might try differently next time?” At the time, I did not have the full vocabulary to explain my frustration or fear, but I knew something important had just happened. She had seen me, not just the mistake. And in that moment, I began learning how to see myself too (Nduagbo & Cassle, 2023).

the students became resistant, not just to the content but to the way it was being taught. I was met with persistent challenges and what felt like a lack of collaboration in the learning process. Their questions did not seem intended to

I asked myself how I could reframe my approach, not to avoid resistance, but to meet it with compassion.

promote dialogue. They felt defensive, and at times, dismissive. It was tempting to frame this as their problem, not mine. But that fifth-grade lesson reminded me otherwise. Research within the Whole Child framework underscores that students learn best in environments that are physically and emotionally safe for students and adults, otherwise they cannot fully engage or concentrate.

That memory returned to me recently in a very different setting. I was teaching a graduate-level multicultural psychology course. The class included difficult data, material that required students to confront systemic inequities and examine their own social positioning. Some of

After class, I returned to some of my graduate texts (Myllykoski-Laine, 2024). I pulled out Sue and Sue, a foundational resource I had once used to help clients explore their internalized conflicts. Suddenly, it was guiding me back to myself. The message was clear. Selfreflection is not just about hindsight. It is about responsiveness in real time. I asked myself how I could reframe my approach, not to avoid resistance, but to meet it with compassion. I shifted from

a didactic style to a more dialogical one. At the next class, I began with a personal story. I shared transparently why this material matters to me. Then I invited the students to speak honestly about what was showing up for them. This shift aligns with the Whole Child tenet that active engagement and a sense of connection to the school and broader classroom community can transform learning dynamics. This was not to debate the data, but to examine how it was landing emotionally and intellectually.

The change was subtle, but powerful. It did not eliminate resistance overnight, but it transformed the energy in the room. The space opened. Students began to reflect out loud, not only on the material but on their reactions to it. That clarity was not achieved through stronger arguments or polished slides. It came through self-reflection. By reframing my approach to foster dialogue rather than avoid resistance, I was living the Whole Child principle of challenging students academically while preparing them as critical thinkers in a global environment (Constanza, 2019).

In a world that moves quickly and prizes certainty, reflection can feel inefficient or even indulgent. But it is what allows us to teach with integrity. It is what allows us to see clearly. Not just the curriculum or the outcomes, but ourselves and the

students in front of us. I remain grateful for the teachers who modeled reflection for me, for the authors who reminded me to return to it, and for the students who challenge me to practice it more deeply every time I teach.

ASCD, (2007). Whole child approach to education [tenets]. https://files.ascd. org/staticfiles/ascd/pdf/siteASCD/ publications/wholechild/WC-OnePager.pdf

CDC. (2024). Whole school, whole community, whole child (WSCC). https://www.cdc.gov/whole-schoolcommunity-child/about/index.html

Costanza, V. (2019). The whole child bridge. https://teachingstrategies. com/blog/the-whole-child-bridgelinking-tenets-to-developmentaldomains

Myllykoski-Laine, P. (2024). Self-reflection supporting teaching and well-being in higher education. Reflective Practice, 25(5), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080 /14623943.2024.2376784

Nduagbo, S. O., and Casale, C. (2023). Reflective practice and preservice teachers’ professional growth:

Impacts on self-efficacy. Experiential Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 6(1 - March), 56–66. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ EJ1422264.pdf https://doi. org/10.46787/elthe.v6i1.3555

Dr. Israel Espinosa is a humanistic leader and transformative educator dedicated to fostering academic excellence, equity, and integrity across higher education. As Chair of the Humanistic Psychology

Department at Saybrook University, he brings decades of experience in mentoring doctoral students, developing interdisciplinary programs, and advancing inclusive pedagogical practices. His leadership is rooted in compassion, clarity, and a deep commitment to empowering learners to think critically, live authentically, and engage meaningfully with their communities.

Contact: iespinosa@saybrook.edu

John Hattie, Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey and John Taylor Almarode

Review by Belinda Veillon

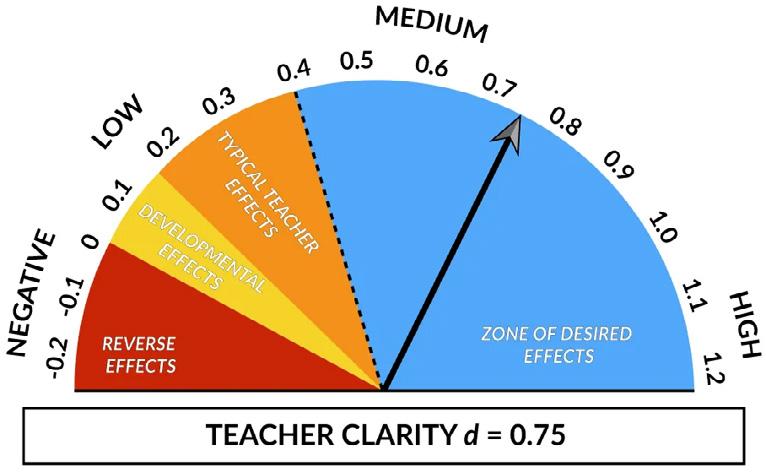

The Illustrated Guide to Visible Learning: An Introduction to What Works Best in Schools, authored by John Hattie, Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and John Taylor Almarode, is an excellent resource for any educators who desire to enhance their practice utilizing robust, evidence-based strategies. The Illustrated Guide, published by Corwin Press in 2024, incorporates John Hattie’s research, which is based on 2,100 meta-analyses and 130,000 studies involving more than 300 million students. In conjunction with authors Doug Fisher, Nancy Frey, John Almarode, and illustrator Taryl Hansen,

Visible Learning has been translated into an accessible, visually engaging guidebook. The goal of which is to make the foundational goals of Visible Learning accessible to educators.

The Illustrated Guide is based on four big ideas that serve to connect Hattie’s research findings together: climate first, learning second, achievement third; students should drive their learning; know thy impact; and collective responsibility for learning. In addition to the four big ideas, there are targeted sets of mindframes for learners, teachers,

leaders, family/caregivers, belonging, identities, and equity that can be used as self-assessments for determining strengths and providing guidance for where to begin an implementation journey toward more effective practices. To support the journey, The Illustrated Guide is divided into eleven signature practices: classroom and school climate, teacher clarity, phases of learning,

to absorb ‘chunks’ of related information that can then be digested in conjunction with a set of related chunks that support implementation. For those desiring additional explanations and more indepth background research to support the strategies, there is Visible Learning: The Sequel (2023). The structure is based on concise summaries that are organized into meaningful sections and chapters.

The selection of high-impact strategies included is a ‘just right’ launch into bringing these practices into action within any learning environment.

teaching students to drive their learning, teaching with intent, practice and over-learning, feedback, the power of the collective, learning learning, implementation, and evaluative thinking. These signature practices are elaborated through the use of key influences, implementation guidance, checklists, and organizers, bringing Visible Learning from concept to practice.

The best feature of this book is its accessibility. The selection of high-impact strategies included is a ‘just right’ launch into bringing these practices into action within any learning environment. The format of The Illustrated Guide to Visible Learning is reminiscent of a professional graphic novel, which allows the reader

It is an excellent reference guide for specific details related to the influences.

While one track of my mind was reading The Illustrated Guide to Visible Learning, the other tracks of my mind were focusing on its use with educators. It would make an excellent text for a professional book club. If being read by a whole staff or in groups, utilize a workshop model differentiated by educator capacity. Additional salient features include:

• Non-linear structure: The Signature Practices sections can be implemented in the order that best matches the goals and needs of any educator, classroom, and/or school.

• Terminology: The Illustrated Guide to Visible Learning high impact strategies provide terminology that teachers can use with their students.

• Practical Tips, Models, and Dialogue: Throughout the book are provided that teachers can use to support their students’ learning dispositions

• Enhanced Design Features: The arrangement of texts, illustrations, and graphic organizers is key to The Illustrated Guide’s being accessible, actionable, and motivational for teachers and leaders.

I recommend The Illustrated Guide to Visible Learning as an essential professional resource for any educator who desires to bring high-impact strategies alive in their daily learning environment, whether within a professional learning community, a classroom, or a school.

Belinda Veillon has served and continues to serve in education as a teacher, gifted program coordinator, building administrator, and Director of Curriculum. She has been instrumental in the development of district-wide programs including school improvement, MTSS, gifted, inclusion; she has written and manages federal and state grants. Belinda is an active member of the Board of Directors of PD365 (formerly IL ASCD), having most recently served as Past President. Belinda is the Affiliate Director of Illinois Future Problem Solving.Referred to as a “squiggle” because of her ‘outside of the box thinking’; she is often able to envision the impossible as a reality. Her inspiration comes from her ability to make connections with people, concepts, and projects.

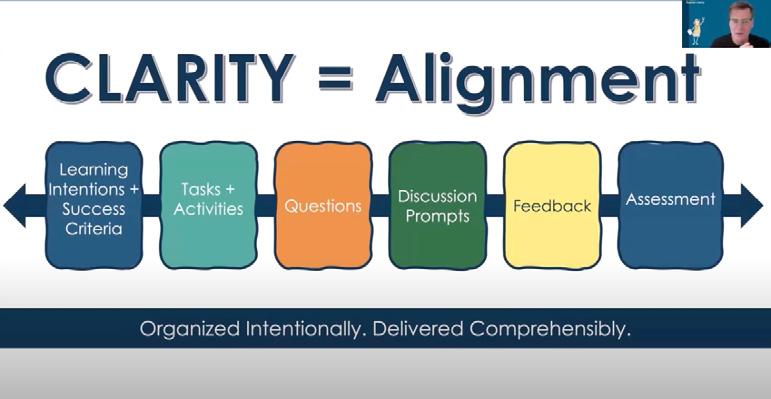

Making sure you understand what your students need to learn, and that you can identify how they will know that they learned it. READ MORE...

There are a number of ways you as the teacher can clearly articulate the objective of the lesson. READ MORE...

THROUGH

Clear understanding doesn’t come from a teacher’s presentation of information—it evolves through students figuring out what they are learning, together.. READ MORE...

Click the covers to view on Amazon.

Strengthen your team’s capacity for data-driven dialogue with a tool built for clarity and coherence. READ MORE...

Alignment, alignment, alignment. WATCH THE VIDEO

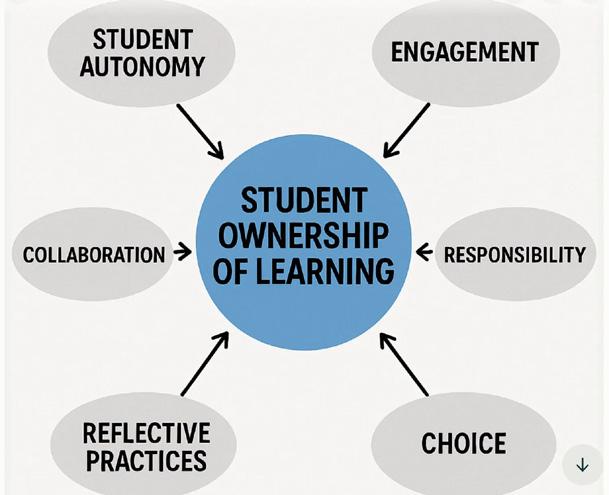

Students take responsibility for their learning process, set goals, make decisions, and monitor their progress with course content. READ MORE...

Four years ago, I looked in the mirror and no longer recognized myself. The vibrant, energized, and full-of-life educator-mom-wife seemed gone, and instead, I saw a worn-out and exhausted version of myself.

At the time, I was teaching in a college of education at a local university. It was my third year working full-time in higher education and my 17th year teaching. Ever since I started my career as a high school English teacher, I thought, “Some day, I might want to teach teachers.”

Here I was doing just that. In my mind, “I had made it”: I had taught high school for over a decade, coached multiple youth sports, stepped into school leadership roles, pursued a master’s degree and then my doctorate, and had landed the “dream job.” I was teaching bright and enthusiastic young people about how to teach and observing them in their novice and student teaching placements. I loved the classes I was teaching and felt like I was making a difference in their lives as future educators.

However, when I visited local teachers' classrooms to watch my college students teach, I noticed something

else, too. The exhaustion. The giving of oneself to one’s job. The wearing down of one’s mindset year after year when we pour everything into our classrooms, our students, and our school community. The secondary trauma of supporting students who come from a variety of backgrounds and home lives.

disapproval. A few years prior, I heard our new school district superintendent during our opening day of the school year tell an auditorium full of my colleagues:

They were hearing horror stories about teaching from those in the field, versus encouragement.

“My daughter told me she wanted to be a teacher. I told her, ‘Don’t do it.’”

I not only saw it, but I heard it in conversations with excellent, veteran teachers who would tell me things like this: “I’ve been teaching for over a decade. I don’t know how much longer I can.” “This job isn’t the same as when I started, and I feel like I’m barely surviving.” “It’s really hard to be an excellent teacher these days.”

For years, I also heard rumblings from my college students that teachers in their placement schools would “warn them” about the teaching profession. Some even urged them to “get out before it’s too late,” causing my college students to question whether they had chosen the right path to become an educator. They were hearing horror stories about teaching from those in the field, versus encouragement. Some were even pursuing a teaching degree despite their parents’

These experiences—of my college students, colleagues, and teachers across the state—in addition to my personal experiences, made me realize that something needed to change in my life and how we support educators.

From the very beginning of my career, I believed that being a “good teacher” meant giving all of myself to the job: late nights at school planning, weekends filled with grading and coaching youth sports, and summers spent preparing for the next school year. It’s just what you do, especially in the initial years of teaching.

Once I had children, I learned to put necessary boundaries in place between work hours and family time. I stopped coaching so that I could spend evenings at home and on the weekends focusing on my family. Even during my doctoral program, I had healthy boundaries.

However, due to the stress of doctoral work on top of motherhood, I developed unhealthy habits that I used to cope with the stress. Late evenings and little sleep due to working on my dissertation, having a drink “to take the edge off,” eating easyto-grab and highly processed foods, and a lack of daily movement due to the hours of reading, researching, and writing.

the universe has a sense of humor, she was also potty training, so I often took meetings with the camera and sound off while I sat on the bathroom floor. Mentally, I just pushed through. Emotionally, I had to keep it together.

With the move to one-to-one technology, teaching expectations, new district initiatives, curriculum changes, etc., it’s hard to balance work and life unless you intentionally do so.

Physically, I sat behind my desk all day and late into the evenings, catching up on emails, preparing for class, and recording lectures.

Those unhealthy habits continued post-graduation with the new stress of working in higher education, but I still had boundaries. Family time was important to me.

Then COVID hit. That’s when all boundaries and work-life balance disappeared. I was teaching college courses at home and leading meetings, while also helping my two elementaryaged children with their virtual classes and their schoolwork. I kept my threeyear-old entertained while I logged into department meetings and held live, virtual classes. Oftentimes, she’d make an appearance, climbing on my lap to pretend to do my makeup. And because

When we went back to work and into classrooms, the former boundaries I had in place didn't magically reappear. It’s as if work and life blended together without any separation. And this continued for years, until I looked at myself in the mirror and decided it was time to change.

While my story reflects my own life experiences, for many educators, setting boundaries and work-life balance has also been a challenge (Doan et al., 2024). With the move to one-to-one technology, teaching expectations, new district initiatives, curriculum changes, etc., it’s hard to balance work and life unless you intentionally do so.

Like so many educators, year after year, I slowly lost touch with the things that once brought me joy outside of the classroom—connection with my children, presence with my family, and a sense of balance in my own mind, body, and spirit.

What I realized in that moment of looking in the mirror was this: losing oneself doesn’t mean you can’t find your way back. The first step was acknowledging that change was needed, and the next step was a step forward in the right direction.

I started to work on my physical wellness first because I found myself on the couch most afternoons, absolutely exhausted. This wasn’t just “the first week of school, teacher tired”; I was completely drained, day after day. I worked with a nutrition and fitness coach to help me examine my current habits and make small shifts each week to help me nourish my body. I focused on what I was eating, drinking, how I was moving my body, and my sleep. I made sure to drink enough water, move my body daily through morning and evening walks, and began to put boundaries in place so that I could “shut down work,” spend time with my family, and get a good night’s sleep (Aguilar, 2018; Tate, 2022). I learned that if I wanted my body and mind to perform a certain way, I had

to fuel it with food and movement that energized me, versus drained me.

I examined my daily routines so that I could put systems in place that supported me. My stress level was at an all-time high, so I began to start my day in a more peaceful state. I woke up 10 minutes early for quiet reflection before my children woke up. Four years later, it is still how I start my morning. I call it my “10-Minute Power Practice.” I brain dump, set three intentions for the day, and express gratitude–all research-based strategies to support my mental and emotional health (Strom, 2024). I also built in things that “filled my cup” on a daily basis: connecting with my children and spouse, walking in the morning and evenings, reading before bed–things that I had sacrificed before became a priority once again.

Managing my stress helped to boost my resilience and change the negative habits I had developed. This included taking deep breaths before responding to emails, standing up to stretch before starting a new work task, walking to the water fountain to clear my mind before a meeting or starting class, or going on a distraction-free walk after work. I also became more self-aware of my emotions throughout the day and asked myself, ‘How am I feeling? Why might I be feeling this way? And what can I do about it?’

In Onward: Cultivating Emotional Resilience in Educators, Aguilar explains, “With emotional intelligence, we can register our physical state and learn strategies to regulate our physiological response so that we can return to a clearer thinking state” (p. 57). I became more aware of my emotional state

school communities, teachers, and students can thrive (Aguilar, 2024; Aguilar, 2018; Tate, 2019).

At the school district level, socialemotional initiatives, programming, and professional development can support faculty and staff to help individuals

Professors can encourage setting healthy boundaries, modeling how they do so themselves, and talking about the challenges and successes of doing so.

as I practiced different mindfulness strategies, like becoming aware of my emotional cycle and the conditions under which my emotions developed, focusing on my breath, sitting in stillness, and then deciding the best next step for that situation (Aguilar, 2018; Hanson, 2020). Over time, these strategies became part of my day.

With rising teacher burnout, lack of newteacher mentorship, and overwhelming responsibilities pushing educators to the brink (Diliberti & Schwartz, 2023; Dill, 2022; Marken & Agrawal, 2022), it is essential that we support the whole teacher, not just the role they play in the classroom. As educators, we must remember that our wellness isn’t optional—it’s foundational. When we support the whole teacher,

At the university level, department initiatives and teacher education coursework can focus on supporting students and their overall well-being. Wellness initiatives can be encouraged through programming, events, and mentorship of teacher candidates (Ireland et al., 2024). Professors can encourage setting healthy boundaries, modeling how they do so themselves, and talking about the challenges and Teacher Wellness (cont.)

establish boundaries (Stevens, 2024), create healthy habits at work and at home (Tate, 2019), and do things that bring them joy each day (Aguilar, 2028). School administration and teacher leaders can model what it looks like to hold healthy boundaries, listen to teachers’ needs, and provide time for teachers to focus on teaching and learning.

successes of doing so. Coursework can encourage students to read about and practice wellness habits and work on resilience strategies as they develop their teacher identity.

Our schools cannot function without healthy, fulfilled adults who are taking care of our students. The “collective wellbeing” of educators and school leaders matters more now than ever before (Aguilar, 2024, p. 2). In my own home, classroom, and in the schools I’ve had the privilege to work in, I have experienced firsthand what Aguilar states here: “Students cannot thrive unless the adults who spend all day with them are also thriving; teachers cannot thrive unless the coaches and administrators who support them are also thriving” (p. 2). Teacher wellness must be a priority because it’s foundational to every classroom and every school.

Aguilar, E. (2024). Arise: The art of transformational coaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Aguilar, E. (2018). Onward: Cultivating emotional resilience in educators. John Wiley & Sons.

Diliberti, M.K, & Schwartz, H. L. (2023). Educator turnout has markedly increased, but districts have taken actions to boost teacher ranks. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/ research_reports/RRA956-14.html

Dill, J. (2022, June 20). School’s out for summer and many teachers are calling it quits. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ schools-out-for-summer-andmany-teachers-are-calling-itquits-11655732689

Our schools cannot function without healthy, fulfilled adults who are taking care of our students.

The lesson I’ve learned is this: our individual wellness must come first. Then, collectively, we must move forward to do better for ourselves, our families, our students, and our school communities so that we can help our students to become thriving, healthy individuals themselves.

Doan, S., Steiner, E.D., & Pandey, R. (2024). Teacher well-being and intentions to leave in 2024: Findings from the 2024 state of the American teacher survey. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/ research_reports/RRA1108-12.html

Hanson, R. (2020). Resilient: How to grow an unshakable core of calm, strength, and happiness. Harmony.

Ireland, A., Hill, L., & Twomey, S. (2024). Preservice teachers and school health and wellness. In Education, 29(3): 77-93. https://www.researchgate. net/publication/386065033_ Preservice_Teachers_and_School_ Health_and_Wellness

Marken, S., & Agrawal, S. (2022, June 13). K-12 workers have highest burnout rate in U.S. Gallup News. https://news. gallup.com/poll/393500/workershighest-burnout-rate.aspx

Stevens, G. (2024). Beat teacher burnout with better boundaries: The secret to thriving in teaching without sacrificing your personal life. Red Lotus Books.

Strom, K. (2024). Start your day strong: “10-Minute Power Practice.” drkristenstrom.com. https://www. drkristenstrom.com/journal/startyour-day-strong-10-minute-powerpractice

Tate, M. L. (2019). Healthy teachers, happy classrooms: Twelve brain-based principles to avoid burnout, increase optimism, and support physical wellbeing (Manage stress and increase your health, wellness, and efficacy). Corwin.

Dr. Kristen Strom, Ph.D., is a keynote speaker, published author, and awardwinning leader in education and agriculture. She began her career as a secondary language arts teacher and has taught and mentored preservice teachers at Illinois State University, Knox College, and Bradley University. She has presented at state and national conferences, including the National Council of Teachers of English and the Illinois Association of Teachers of English, and has been published in peer-reviewed journals and edited book collections. She currently serves as the Director of Education and Agriculture Outreach for an Illinois State Representative and consults with Illinois Regional Offices of Education and schools on professional development focused on wellness, curriculum, literacy, and new teacher support.

As the founder of her brand and website (www.drkristenstrom.com), Dr. Strom helps educators and professionals prioritize work-life balance and personal wellness through speaking engagements, workshops, coaching, and digital content. Her weekly newsletter for educators can be found at https://hope-notes-foreducators.kit.com/signup

It was a moment no leader is ever truly prepared for. One of our high school students collapsed during a basketball game and died later that night. Her family was present. Her peers witnessed the scene. And our staff—teachers, coaches, board members—were suddenly thrust into the kind of collective trauma we hope we never face.

And yet, what surprised me most wasn’t the tragedy itself. It was how instinctively our team responded. It wasn’t a script. It wasn’t a formal plan. It was presence, compassion, and relational leadership in motion.

In the weeks and months that followed, I reflected deeply on what shaped that instinct. Where had I learned to lead with such care, caution, and awareness in a moment where there was no guidebook? The answer was simple: my mistakes.

Some were professional—things I had done wrong in lower-stakes moments. But many were personal. I’ve lived through a lot of school-based loss. As a student.

As a peer. As the child of a teacher in a small rural district. And those formative experiences informed not only my actions, but also the boundaries I put in place to protect our students, our staff, and our grieving community.

This article isn’t about a single moment. It’s about the lessons I carried into that moment—and the ones I’ve learned since.

When we lost our student, our district had a crisis plan. It was strong—so strong, in fact, that our Regional Office of Education now uses it as a model. But a plan on paper is a very different thing from living through a crisis in real time.

What carried us through wasn’t just the plan. It was the lens of emotional intelligence:

• Self-awareness kept me from rushing decisions out of my own fear and urgency.

• Empathy allowed me to anticipate the needs of grieving staff and students before they had words for them.

• Relationship management helped me navigate the tension between public grief and private pain.

In those first days, we made choices grounded in people, not just optics: restructuring a SIP day to focus on grief

and trauma, creating safe spaces for tributes away from the students’ locker, and drawing on trusted mental health providers for support. Each step was guided by transparency and compassion.

By Friday night—less than 24 hours after her passing—a memorial had already begun to appear outside our Junior High. Students gathered there, hugging, crying, leaving flowers, teddy bears, and handwritten notes. It was natural and deeply human. In moments of collective grief, people need something to do, and pop-up memorials are one of the most organic expressions of that need.

But from my home that night, I saw the safety risks right away. The memorial sat alongside a busy road with no barrier between traffic and the crowd. It was also directly at the Junior High entrance—a space that served our fifth through eighth graders, many of whom were still developmentally unable to process such visible grief.

By Saturday morning, I was out in a cold January rain, gently moving the tributes. We relocated them to the High School lawn—a safer, symbolic space marked by a flagpole and raised base. Before moving anything, I called the student’s mother, explained the concerns, and

promised every item would be preserved. She was gracious and supportive.

National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement:

• Temporary memorials are appropriate when they arise organically, but they should be time-limited.

That was the moment I learned this truth: the first act of mourning sets the tone for everything that follows.

I followed up with a message to families and students: clear, compassionate, transparent. Everyone needed to know this was done with care and with the family’s blessing. When students returned to see their items had been moved, they didn’t feel erased—they felt respected.

Still, one question gnawed at me: how long should this stay? A week? A month? Until the end of the school year? And practically, this was January in the Midwest. Balloons deflate, flowers rot, teddy bears get soaked. At what point does a tribute meant to comfort actually harm those walking past it every day?

Until that moment, I had been leading by instinct. But this decision had no obvious answer. So I turned to the mental health professionals who had surrounded us that weekend. Their advice was clear: two weeks—one week after the funeral.

That guidance aligned with what I would later read from the NASP and the

• Long-term displays can stall healing or unintentionally communicate that one life is valued more than others.

• Visually intense shrines in common spaces can overwhelm students and impair their ability to return to normalcy.

So we followed their lead. I communicated a removal date, explaining that every item would be preserved and delivered to the family. When the day came, we gathered each note, flower, and ribbon quietly and respectfully. Nothing was discarded. Nothing was treated as debris.

Looking back, if I could do one thing differently, it would be this: I would have anticipated the memorial’s formation from the very start. Pop-up tributes are so common, so expected, that leaders should be ready before the first flower is ever placed.

That was the moment I learned this truth:

the first act of mourning sets the tone for everything that follows.

In the immediate aftermath, memorials were raw and necessary. They gave students and staff a place to channel their sorrow, to feel connected, and to begin the impossible work of making sense of what had happened.

But as the weeks passed, the tributes didn’t slow. They multiplied.

Her birthday in May brought requests for a balloon release on our newly installed turf field—a request complicated not only by facilities and cost, but also by pending state legislation against helium releases. We offered alternatives. The family declined. The tribute moved to the cemetery.

That moment marked a subtle shift. The center of gravity moved from school to family. In some ways, that was natural. Four months had passed. Students were finishing the school year. The sharpest edges of grief had softened, and many were ready for remembrance rather than active mourning.

But it wasn’t that simple.

Because this student had been so involved in sports, in clubs, in friendships—there was always another group who hadn’t yet grieved publicly,

who hadn’t had their moment. Each new tribute carried love, but also unintended consequences: students who felt suffocated by reminders, families who compared tributes against their own past losses, and staff unsure how or when to move forward.

The longer it went on, the more memorialization became a dividing line instead of a unifying force.

This tension wasn’t new to me. I’d seen it before.

In high school, I was on the yearbook staff during an unusually tragic year. Four students in our school died, each in separate incidents. By the time we submitted our cover design in March— red bricks with the theme “Another Brick in the Wall”—three students had passed. We added their initials on the back cover, carved into the design as a subtle but powerful tribute.

And then, in May, a fourth student died by suicide.

It was too late to change the cover. Inside the book, we honored all four equally. We explained. We apologized. But the absence of that last student’s initials on the cover lingered. Some believed it was intentional. Others believed it reflected judgment about the manner of his death.

In trying to honor the dead, we hurt the living. Our inconsistency left wounds.

That experience stayed with me. Years later, as a school administrator, I understood why: grief needs consistency, and perceptions matter more than intentions. And we must always be ready for the unthinkable to happen again.

What I learned in those months—first as a teenager, later as a leader—was this: grief must be honored, but it must also be guided. Without boundaries, one loss risks overshadowing others. Without

remembrance and family-led efforts.

• The courage to redirect tributes in ways that balanced compassion with developmental appropriateness for students.

There is no way to lead perfectly through grief. But if I could offer one lesson, it would be this: anticipate the memorials. Don’t wait for them to appear. Gently guide them toward safe, visible, timebound spaces.

Protect emotional space—remember that not all students grieve publicly. Plan

Without consistency, one family feels honored while another feels forgotten.

consistency, one family feels honored while another feels forgotten.

Schools sit at the crossroads of public and private grief. That means leaders must make hard calls—sometimes saying no to what feels emotionally urgent in order to protect the longer arc of healing.

We found ourselves needing policies we didn’t yet have:

• Clear memorial guidelines rooted in equity and trauma-informed practice.

• Boundaries between school

ahead, even if you never need the plan. Name the tensions instead of pretending they don’t exist. And above all, lead with heart as much as with protocol. In the middle of the emotional tumult of a crisis is not the time to try to think clearly about unintended messages and longterm sustainability.

I didn’t get everything right. But what we did well—what allowed our district to carry this loss with dignity—was rooted in presence, humility, and care.

And if the worst day comes for another

leader, I hope these reflections help light their way, even just a little.

Dr. Lynette Thrasher is the Assistant Superintendent at Momence CUSD #1, where she leads curriculum and student

services with a focus on relationships and well-being. A founding member of her region’s Crisis Assistance and School Support Team, she is currently working on a forthcoming book on grief leadership in schools.

Dakota Horn

Incorporating instructional design best practices has so many intricate layers to consider. Instructors can find best practices on how to structure content, build a rubric, create an assignment description... and the list goes on. It is a constant conversation that evolves. Every educator can point to certain expectations, standards, practices supported by research, and tricks they learned through their many years of teaching. But what happens when all of those things actually cause concern for your students? And they call you out on this?

One of the authors is a student who voiced concerns over course design principles. The other author was their instructor. Their conversations open the door to a reflection on what can be done to improve our instructional efforts and to the challenge that these efforts need to be prioritized. We explore how instructional materials using best practices “box in” a student. We discuss that the focus of the course content is limited, and the student is looking for more. Finally, we walk through how “good” assessment design limited the student. This is not an exploration of what is right or wrong, but how these conversations helped improve courses. This is an encouragement to be reflective and

Instructional Design (cont.)

include students in the conversation strategically. And it’s ok to admit that you need to change something.

Best practice at issue:

Using standardized course materials and uniform content delivery to ensure consistency across classes (Phillips & Garcia, 2015)

Instructor:

I’ve always tried to choose standardized course materials and a single textbook for specific subjects so every student receives the same information and structure, ensuring fairness and consistency across all sections, classes, and different groups. It is assumed this approach helps reduce confusion, provides a clear roadmap for success, and helps students meet learning outcomes more efficiently. When a student comes to you and says that the materials themselves were causing concern, it gave me quite a shock.

I understood these structures were meant to help us meet learning outcomes, but for me, they limited creative expression.

Student:

One of my biggest challenges in the course was how the content was presented through the textbook and assignment materials. While intended to guide students toward success, I often felt “boxed in” by the standardized formats and rigid examples. Specifically, in my speech class, the outline structures promoted in the textbook felt formulaic, almost as if deviating from them meant my work would be considered “incorrect.” I understood these structures were meant to help us meet learning outcomes, but for me, they limited creative expression. So, I went to the instructor and brought up my concerns.

Conversation Result:

After our conversations, we reconsidered how content could be framed to keep essential learning goals intact while providing more flexibility. For example, instead

of requiring one standard outline format, multiple models could be presented, allowing students to choose the structure that best fits their communication style. Similarly, assignment instructions could focus more on the “why” and “purpose” of the task, rather than over-emphasizing one “correct” way to execute it.

Content

Best practice at issue:

Focusing content to cover fewer areas with more depth and rigor (Hess, 2023)

Instructor:

In this speech class, we cover speech anxiety and apprehension. The focus is to cover particular techniques, such as systematic desensitization and breathing exercises in depth, and not cover other ideas because of the concern of too much breadth instead of covering the depth needed. I emphasized repeated practice and exposure because research shows it helps reduce performance anxiety and builds skill over time. I believed this method would give students confidence and a sense of mastery, making them more comfortable in communication settings. Again, the student came to me with concerns over the lack of broad applications. This was the issue that was hardest to hear about. I believed the material provided had a universal approach.

It ... sometimes created pressure to “fix” ourselves in ways that felt unrealistic.

Student:

The course briefly covered communication apprehension and anxiety, but often framed these as challenges that could be overcome simply by practicing more. For students with deeper or ongoing challenges, whether anxiety-related, neurological, or otherwise, this seemed to oversimplify the reality. It also sometimes created pressure to “fix” ourselves in ways that felt unrealistic. I just wanted more information, broader perspectives, and other things to consider.

Conversation Result:

In response, we worked to design instructional materials that more explicitly acknowledged different learner needs. This included adding brief resource sections

in modules linking to campus support services, integrating optional practice activities for different comfort levels, and presenting multiple pathways to demonstrate learning. These strategies didn’t lower the expectations but provided flexibility for students to meet them in ways that worked for their abilities and circumstances.

Assessment

Best practice at issue:

Using detailed rubrics and highly prescriptive assignment descriptions to make grading transparent and consistent (Frontier, 2021)

Instructor:

I created detailed rubrics and highly specific assignment descriptions to make grading transparent and objective. Having a clear and specific rubric to help students meet standards seems like what needs to be done. I believed that outlining every expectation would remove ambiguity, help students self-assess their work, and make the grading process feel fair and predictable.

Student:

Rubrics, while intended to provide clarity, often increased my anxiety and reluctance to use my voice when writing or speaking for an assignment. Knowing that my grade hinged on meeting exact criteria sometimes made me more focused on “checking boxes” than on actually communicating well. Assignment descriptions could also feel overly prescriptive, which limited experimentation. I understood their purpose, but wanted to talk about how I could work around them.

Following our discussions, we experimented with rubrics that emphasized broader performance categories rather than narrowly defined checklists...

Conversation result:

Following our discussions, we experimented with rubrics that emphasized broader performance categories rather than narrowly defined checklists, giving students more room to demonstrate mastery in their own way. They also added reflective prompts where students could explain their design choices, which allowed the assessment to capture both the final product and the thinking behind it.

Instructional design should be flexible enough to evolve with student feedback, maintaining academic rigor while also making space for varied ways of learning and demonstrating knowledge.

The most valuable part of this process was the conversation itself. The student shared how certain “best practices” of instructional design unintentionally created stress or limited their engagement. The instructor was willing to re-examine those practices and not to discard them entirely, but to adapt them so they worked better for different learners. This is difficult when it challenges things you thought were the best idea for learning. These ongoing discussions have shaped course materials, assignment formats, and assessment strategies. The takeaway: instructional design should be flexible enough to evolve with student feedback, maintaining academic rigor while also making space for varied ways of learning and demonstrating knowledge.

The prompt for this forum was to reflect on learning experiences that might have been difficult. Having a student come to you and tell you that the best practices you’ve followed are causing them concern is not a fun conversation. Those conversations happened because

of a strong student and a chance to give that feedback. As an educator, be vulnerable to have those conversations. Build in opportunities for students to provide that feedback, and be willing to listen to these difficult conversations and change on the fly. It is crucial to realize that it is okay to have students challenge and question set expectations as long as these challenges are presented in a respectful manner, and can help improve the learning environment. As educators, be open to reviewing how what we thought was best for our students might actually be getting in the way, and how we can strategically build in ways to get that feedback. From this student and educator to everyone out there, it wasn't easy, but changed the educational experience for the better.

References

Frontier, T. (2021). Teaching with clarity: How to prioritize and do less so students understand more. ASCD.

Design (cont.)

Hess, K. (2023). Rigor by design, not chance: Deeper thinking through actionable instruction and assessment. ASCD.

Phillips, G. & Garcia, A. (2015). Setting Performance Standards for Success. A. American Institutes for Research.

Dr. Dakota C. Horn is Associate Dean for Academic Programs and Associate Professor in the Department of Communication at Bradley University, serving as the Oral Communication Course Director. His research interests and contributions span areas such as communication pedagogy, instructional communication, instructional clarity, humor, storytelling, accessibility in online education, general education initiatives, K–12 education, communication anxiety,

teaching activities, civic engagement, and fostering teacher-student relationships that enhance clarity and reduce anxiety.

Dr. Horn served on the Board of Education, presented research at the Illinois State Board of Education conference, and at the National Rural Educators Association.

Dr. Horn oversees Bradley’s corporate Instructional Design Certificate, a 15-week non-credit program.

Joanna Franco is a lover of learning, who has used that passion to become a firstgeneration college graduate and current law student. She earned her bachelor’s degree at Bradley University, with majors in Political Science and Philosophy, and minors in Business Law and Ethics. As part of her journey and goal of becoming an elected official, she is continuing her education at Marquette University Law School.

Michael Lubelfeld

Vision is one of our most precious senses. For most of my life, I took my eyesight for granted. Then, about a decade ago, my personal vision began to blur. The experience of my eyesight deteriorating became a powerful metaphor for the importance of organizational vision. Just as I had to make a conscious choice to address my failing sight, leaders must actively work to clarify and maintain their organizations' vision.

My journey began with a slow but steady decline in the vision of my left eye. For 35 years, eyeglasses had been my simple solution. They were a reliable method of correction. But suddenly, they weren't enough. I learned I had cataracts in both eyes. Interestingly, my brain had compensated, allowing my right eye to work harder to make up for my left. It fooled me into believing I could still see clearly.

This experience got me thinking. Have you ever been in a leadership position where you felt a shared vision existed, but in reality, your team was compensating for a lack of clarity? A cataract on the eye is like a blurry, unshared vision in an organization. It impedes progress and distorts reality. The old ways of doing things—like my reliable

eyeglasses—were no longer sufficient. To see clearly again, I needed to unlearn old habits, embrace change, and grow.

Cataract surgery required the removal and replacement of the lens in each eye—a much more invasive process than simply updating my glasses. As someone squeamish about medical procedures, this was a difficult choice. I had to confront my fears, accept the risk and uncertainty, and let go of a 35-year habit of wearing glasses.

After two successful surgeries, the change was nothing short of miraculous. My brilliant ophthalmologist inserted a distance lens in my right eye and a reading/mid-range lens in my left. The result? I had better vision than ever before—no more glasses, no more limited night vision. The new "normal" was far superior to the old one. This personal transformation was a powerful lesson in embracing significant change for a dramatically better outcome.

Like personal change, organizational change is often a response to something that happens, and it requires us to adjust, grow, and unlearn. Our vision, both personal and professional, often needs to be corrected so that new methods and improvements can be embraced.

In North Shore School District 112, where I've served as superintendent since 2018, we recently embarked on a strategic planning process. This wasn't about small tweaks; it was about defining our future. Strategic planning is a complex, multi-faceted process of input, reflection, and shared aspiration. It's about collaboratively creating a new mission, vision, and values.

Our new vision, established in March 2025, is this:

"Our vision is to be a thriving, inclusive, learning community where each student is empowered to reach their full potential and achieve their greatest aspirations. By utilizing evidence-based practices, innovations in teaching and learning, and personalized support, we create an environment where each student learns, grows, and achieves academic excellence. We nurture resilience and foster meaningful relationships, while developing transformative leaders, engaged learners, and responsible citizens who are inspired and equipped to make a positive impact."

An organizational vision is an aspiration, a hope for the future. But a shared vision is what makes it powerful. It's when every member of the organization synthesizes

their individual hopes and aspirations into a common cause. My role as a leader is to inspire that shared vision, to turn multiple points of input into a coherent action plan, and to create meaningful change that everyone is invested in.

where technology would reduce a threeperson job to a single person and a robotic arm?

This technological shift didn't necessarily eliminate two jobs; it transformed

My role as a leader is to inspire that shared vision, to turn multiple points of input into a coherent action plan, and to create meaningful change that everyone is invested in.

The importance of a clear vision extends beyond our own organizations. We must also have a clear vision for the future our students will enter. I was reminded of this recently while walking my dog and watching a waste management truck. The truck pulled up to the recycling bin, but the driver didn't get out. A robotic arm extended, grabbed the bin, emptied its contents, and placed it back on the curb.

I couldn't help but think about my childhood. When I was a boy in the 1970s, a garbage truck had a crew of three people: a driver and two workers who rode on the back. This simple observation sparked a big question: Did my elementary school teachers, four decades ago, contemplate a future

them. It created new jobs in robotics engineering, engine design, and technology maintenance—roles that required skills and knowledge unimaginable in the 1970s. The waste management industry’s vision to increase efficiency and integrate technology changed the nature of the labor force.

As educational leaders, this is our challenge. We must support and lead organizations that are preparing students for jobs that may not even exist yet. The waste management story is a reminder that we must consistently refine our vision to meet the demands of a rapidly changing world. My personal vision is clear, thanks to medical intervention. My organization’s vision is clear, thanks to a strategic planning process.

My question for you is: can you see clearly in your personal and professional life? What will you do to correct your vision?

Subject content was taken from blog posts I previously published at https:// mikelubelfeld.edublogs.org on January 22, 2017 and April 5, 2016.

Dr. Michael Lubelfeld is superintendent of North Shore School District 112 in Illinois and has led school districts since 2010. A nationally recognized education leader, author, and speaker, he presents on leadership, student voice, global service, and innovation. He co-authored five books, including The Unlearning Leader and The Unfinished Teacher. Dr. Lubelfeld was honored as a 2025 Top 100 Influencer in Education and is a 2025-26 ISTE-ASCD Generation AI Fellow and Google-GSV Fellow. He has received multiple leadership awards and remains dedicated to empowering future-focused educators.

Click the covers to view on Amazon.

Our “Area Reps” are a link to and from the various regions of our state. IL ASCD follows the same areas established by the Regional Offices of Education.

Our Area Reps are led by a members of our IL ASCD Board of Directors, Denise Makowski.

AREA 1: (Green)

Denise Makowski

Chicago

618.203.3993

dmkowski224@gmail.com

Amie Corso Reed

O'Fallon School District

618.203.3993

amie.corso@gmail.com

AREA 2: (Dark Blue)

AREA 3: (Yellow)

AREA 4: (Pink)

AREA 5: (Light Blue)

AREA 6: (Gold)

April Jordan

Jennifer Winters

Stacy Stewart

Jen Pollack

Chad Dougherty

Heather Bowman

Jamie Bajer

Mica Ike

Vacant

Contact information for them can be found HERE.

The roles of the IL ASCD Area Representatives are:

• Encouraging IL ASCD membership to educators in their local areas;

• Assisting with professional development;

• Attend board meetings and the annual leadership retreat, when possible;

• Disseminating information from IL ASCD board meetings or other sanctioned IL ASCD activities to local school districts or other regional members

• Being a two-way communication vehicle between the local IL ASCD members regarding IL ASCD or any educational issues.

• Keeping IL ASCD Board of Directors apprised of pertinent information regarding personnel issues (e.g., job vacancies, job promotions) and district program awards/recognition within the local area.

• Communicating regularly with IL ASCD Executive Director and the Co-Leaders of the Membership and Partnerships Focus Area.

Melissa Gill

"One fundamental misconception is that SoR advocates simply want more phonics instruction. Rather, the advocates who know what they’re talking about want more effective phonics instruction” (Wexler, 2025).