INVESTIGATIVE INVESTIGATIVE

QUARTERLY

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

Dear Colleagues, Members and Sponsors,

We are slowly winding down the year and coming into the holiday months. Thus far, 2023 has been an exciting year for the International Homicide Investigators Association (IHIA). We have had the opportunity to facilitate and share training, experiences, and best practices with over 1500 course attendees in the United States, Colombia, and the United Kingdom. The second half of the year remains just as exciting as the first half of the year with the upcoming DNA and Genealogy Summit in Washington, DC, the Cold Case/No Body Homicide Investigation & Prosecution course in Mesa, Arizona hosted by the Mesa Police Department, the Advanced Homicide & Violent Crimes Investigation hosted by Grand Prairie Police Department, as well as Bogota, Colombia and Sri Lanka with ICITAP and the FBI. Please continue to check www.ihia.org for the latest training opportunities.

Planning for the 2024 Symposium in Washington DC is currently underway. As many of our members and sponsors know, we are dedicated to bringing our members great case presentations, the latest investigative tools, and developing technologies that could assist our members in their death investigations. The Symposium Planning Committee is currently seeking case presentations and emerging trends/technologies nominations for Washington, DC. If you know of any great cases that you would like to be presented or any new trends, please reach out to your Regional Director or myself, the Vice President, the Executive Director, or the Training Coordinator via the website. We would love to hear from the membership.

Additionally, we recently updated and improved our website. The new design provides for a better user experience. Please continue to utilize the website, www.ihia.org, for the latest training opportunities, our association sponsors, as well as our valued exhibitors. The website is also a great tool for locating investigators in other states and other countries.

On behalf of the Association Board, I want to thank you for your membership and continued support. We couldn’t do any of this without you. We will continue to strive to provide resources, guidance, and training to each of you and our profession.

What’s Inside the IQ:

• Letter from President Paul Belli

• From the desk of the IHIA

Executive Director Steve Lewis

• Article: Beyond Violent Extremism

• Article: Can You Reuse Evidence Gathered by a Different Agency’s Case

• Article: Cold Case and Collaborations

• Article: Stand by Me

• Article: Use of Deadly Force on a Suspect Armed with a Replica Firearm

• Your Leading Role in the DNA Evolution of FIGG Enabled Criminal Investigations

• Biography of “New” Board

Member: Jessica Koong

• Biography of “New” Board

Member: Ed Streidinger

• Save the Date: 2024 Symposium

• Regional Marketing Opportunities

• Sponsor Advertisements

President Rob Peters International Homicide Investigators Association

™

www.IHIA.org

The IHIA is the world’s largest and fastest growing organization of homicide and death investigation professionals. The non-profit organization represents the largest network of homicide professionals and practitioners ever assembled. The IHIA has representatives in every U.S. state and nations on six continents. For membership information, visit: www.ihia.org/Membership

SEPTEMBER 2023

A Publication by the International Homicide Investigators Association (IHIA)

Sergeant Rob Peters, Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office

The IHIA 29th Annual symposium was held in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, the week of August 7th, 2023. The Sheraton OKC was an outstanding venue, and the surveys proved the attendees enjoyed the training and experience. Over 350 people were in attendance and the lessons learned were outstanding. The social events were fun, the food was amazing and the networking among members of 35 states and 11 different countries proved to be beneficial.

As we concluded the symposium, we welcomed the new President of the IHIA, Sergeant Rob Peters, Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office, to his new position. Rob has been a part of the IHIA for several years and we look forward to his leadership, passion, and experience. We also welcomed a new Vice President, Detective/First Lieutenant David Eddy (retired), Michigan State Police. Our newest member of the IHIA board and Western Region Director, Senior Investigator Edward Striedinger, Washington State Attorney General’s Office, has some big shoes to fill in the west. And Sergeant Neal Clanton, Sacramento County Sheriff’s Office, has moved into the Director at Large position.

Additionally, two of our senior leaders have vacated the IHIA board. We congratulate Captain Greg Esteban (retired), Hawaii Police Department and Captain Mike Corrado (retired), Atlantic County Prosecutors Office, for their many years of service to the IHIA. Their leadership has shaped the future of the IHIA. We wish them well in their future endeavors.

In our continuance in building the IHIA, your Board of Directors created a new position, “Chairman of the Corporate Council”. This new position will be filled by one of our corporate members. This board position was voted on by the corporate council, who are the exhibitors/sponsors you see at the symposium and other events. The Chairman will be a voting member of the board and brings a new perspective to the IHIA. The IHIA congratulates and welcomes Jessica Koong, Senior Marketing Development Manager, Verogen (now a QIAGEN company).

I sincerely appreciate all our members, speakers, sponsors, exhibitors, and board members. Your support matters and the IHIA is excelling because of all of you!

Stay Safe!

Steve Lewis IHIA Executive Director

SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 2 ™ From the desk of The

IHIA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Steve Lewis

Coined in 1993 by a young woman expressing her frustration over romantic failures online, the term “incel” largely did not emerge in the media or scholarly literature until the 2010s. What began as a support group for men and women alike had long been evolving to exclude women and establish an ideology of both male supremacy and grievance. The incel community was brought into the public eye in 2014 by an adherent to the movement who expressed anger over his own involuntary celibacy first in written and video-recorded manifestos and then in an act of extreme violence that left 14 people injured and seven (including the shooter) dead in Isla Vista, California. The incel movement and community were thrust into the spotlight, and although the number of subsequent violent attacks inspired by the Isla Vista shooter has been relatively few, their lethality thrust the entire incel movement into the spotlight as they were labeled as a newdomestic terror threat (Hoffman&Ware, 2020).

As a result of these concerns, scholarly research on self-identified incels took off, focusing primarily on the threat that self-identified incels posed to others, particularlywomen (e.g., Hoffman et al., 2020; Tomkinson et al., 2020). This critical work largely overlooked, however, the nearly 2 decades of incels’ online existence, which had been marked primarily by depression and loneliness. More recently, evidence has arisen demonstrating that the most severe risk of harm posed by self-identified incels may be to themselves (Daly & Laskovtsov, 2021; Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2022). This lack of research and attention to the propensity for depression and suicidal ideation among incels is perilous. Congregating online and often shunning mental health treatment, (male) incels are often targeted with narratives that explain to them how to address their grievances. Some narratives may be presented as modes of self-improvement: If you are being rejected by women, you should exercise more, get plastic surgery, take steroids; anything to improve your physical appearance (Halpin, 2022). Other narratives promote suicide as the only way to take control over one’s life (Daly & Laskovtsov, 2021) by escaping the pain of rejection that is unlikely to end. Still, others encourage violence against women, as well as the men whom they are claimed to prefer (Zimmerman, 2022), as a form of revenge and of settling the account with those who reject them. It is through these different narratives that self-described incels, bound together by a shared grievance of repeated

romantic rejection and feelings of worthlessness and insignificance (Cottee, 2020), diverge in their behaviors. Those who adhere to violence-promoting narratives may grab the media spotlight and pose a meaningful risk to women and society at large (Hoffman et al., 2020). However, focus should also be directed toward those who do not espouse a violent ideology but could gravely harm themselves or move along a trajectory toward violence as they spend more time on incel forums online. The present article aims to distinguish between these three groups of incels using the 3N model of radicalization (Kruglanski et al., 2019) as a theoretical framework for cluster analysis using a sample of 272 self-described incels.

The 3N Model of Radicalization

The 3N model of radicalization, proposed by Kruglanski et al. (2019), holds that there are three necessary elements to deciding to engage in a given behavior, including extremist violence: The need, that is, the motivating force that propels the behavior; the narrative, which prescribes actions that should be taken in order to meet the need; the network, the person’s reference group (Merton & Kitt, 1950), which validates the narrative. In the case of violent extremism, the need element is the universal human craving for significance and mattering, the narrative portrays a given behavior as the path to significance, and the network is the audience of sympathizers that support the narrative and rewards the individual with significance for behaving in accordance with the narrative, thus satisfying their need for significance. This model is consistent with other models of radicalization, most notably the “lethal cocktail of terrorism” (Speckhard, 2016). Each element of the 3N model can be clearly applied to incels. In the following section, we consider them in turn.

READ MORE

Article: Beyond Violent Extremism SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 3 ™

Issue

Law enforcement’s reuse of evidence legally obtained: lawful or not?

Background

I’m periodically asked whether evidence lawfully in the possession of one law enforcement agency can be turned over to another agency, informally, for their use. Without any appellate court case or statutory authority indicating that I might be wrong, I would tell both agencies that it should not be a problem. To me, it’s just common sense. If the cops already have lawful possession of the evidence, a suspect’s privacy rights as to that evidence have already been compromised. So, it matters not which agency uses it in court.

But now, thanks to a 2017 case out of a federal district (trial) court in South Dakota referred to me by Dennis Gomez of Behavior Analysis Training, Inc., (BATI), I have to qualify that advice.

Case Law Gives Some Clarity

In a case of first impression — United States v. Hulscher (District of South Dakota, S. Div. 2017) 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22874 — digital evidence was seized from Robert Hulscher’s cellphone by a state law enforcement agency via a search warrant, to be used in the prosecution of the defendant for his alleged forgery, counterfeiting and identity theft activities. Combined with the evidence seized, but not used, in the state prosecution was evidence related to the defendant’s alleged illegal firearms possession, a matter which was already pending in federal court. A federal ATF investigator got wind of the state’s possession of that evidence and asked that he be given access to it, a request that was granted by the state agency. When the federal prosecutor sought to use that evidence in court, Hulscher filed a motion to suppress. The federal court trial judge granted his motion, publishing his decision in the above-cited case.

Citing the U.S. Supreme Court case of Riley v. California (2014) 573 U.S. 373, the South Dakota federal district court judge in Hulscher noted that the High Court has held that “because cellphones contain immense amounts of personal information about people’s lives, they are unique, and law enforcement officers must generally secure a warrant before conducting such a search.” Thus,

as in this case, where an ATF agent seeks access to digital evidence from a defendant’s cellphone that has been collected by another law enforcement agency but not used, the agent “should have applied for and obtained a second warrant [that] would have authorized him to search Mr. Hulscher’s cellphone data for evidence of (the federal) firearms offenses.”

In so ruling, the court rejected the government’s argument that “law enforcement agencies can permanently save all unresponsive data collected from a cellphone after a search (and use it in) future prosecutions on unrelated charges.” (Page 7) To the contrary, the court held that because information contained in a person’s cellphone is often sensitive, personal information, a warrant asking for a court’s permission to access such information is required under the Fourth Amendment.

The court also rejected the government’s arguments that either (1) the “plain view” doctrine applied (Pages 8-9) or (2) that there was an insufficient “deterrence” effect to justify the suppression of the resulting evidence, as discussed in Herring v. United States (2009) 155 U.S. 135. (Page 9). Although the court tells us that the rule announced here is limited to these facts (i.e., involving cellphones), the judge also cites authority for the proposition that this ruling may be broader than intended. In other words, the theory of the Hulscher decision might well apply to any evidence, whether or not obtained from a suspect’s cellphone.

Specifically, the judge in Hulscher noted that for an officer to obtain warrantless access to information retrieved under the authority of a separately justified search warrant, the net effect would be to convert that warrant into what is commonly referred to as a “general warrant.” A general warrant is one that purportedly allows a law enforcement agency to go on a fishing expedition without justifying the necessary probable cause for whatever is being sought. General warrants are prohibited under the Fourth Amendment. (Page 6; also see Burrows v. Superior Court (1974) 13 Cal.3rd 238, 249-250, for a discussion on “general warrants.”) The rules on general warrants apply whether or not a cellphone is involved.

READ MORE

Article: Can You Reuse Evidence Gathered by a Different Agency’s Case SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 4 ™

Article: Cold Case and Collaborations

Introduction

Translational criminology refers to the interface between scientific discoveries through empirical research and policy and practice (National Institute of Justice/ United States Department of Justice, 2011). It is concerned with the applicability of criminological knowledge which can solve real-world problems. Although the term is relatively nascent, the practices have an established tradition in the discipline of criminal justice. Collaborations between law enforcement and academics to approach specific problems related to crime have become increasingly common and there has been significant progress in the relationships between the two (Bradley & Nixon, 2009; Cordner & White, 2010; Engel & Whalen, 2010; Fyfe & Wilson, 2012; Goode & Lumsden, 2018).

Perhaps one of the most notable of these partnerships was during the 1970s when there was a growing number of stranger killings, seemingly random and motiveless. As a response, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) formed the Behavioral Science Unit (BSU), which included a specialized group of agents who developed and refined offender profiling, an innovative method utilized as a tool to infer personality characteristics from crime scene behaviors. One of these agents, Roy R. Hazelwood, discovered an academic paper authored by forensic nurse and academic Ann W. Burgess on rape victimology and suspect motivations. Hazelwood, a trailblazer in criminology who always sought innovative methods, made a phone call to Burgess. The rest is criminological history—Burgess became the academic force behind the FBI’s most celebrated crime-fighters. The partnership resulted in both advances in scholarly knowledge and investigative practice.

In more contemporary criminal justice practice, new issues have arisen which demand innovative responses. The United States has experienced what Adcock and Stein consider an “epidemic” of cold case homicides (2014). While definitions vary, a cold case is one which has become inactive because investigative leads have been exhausted and the crime remains unsolved (Regoeczi et al., 2008; Walton, 2017). Despite the growing problem of unsolved cases, only about 18% of the nation’s approximately 18,000 law enforcement agencies have designated “cold case units” to investigate these cases and approximately 20% of those units do not utilize proper protocols or evidence-

based practices (Adcock, 2018). These unsolved crimes must often be assigned low priority by law enforcement agencies due to limited resources and competing duties and responsibilities (Mardigan & DePue, 2017). Law enforcement and academic collaborative models of cold case investigation can provide not only the resources necessary to investigate these cases, but also can assist with developing and implementing protocol. Quite often, however, there are mutual misunderstandings which can negatively affect or even prevent these relationships (Bradley & Nixon, 2009).

Historically, there have been several barriers to successful academic-practitioner partnerships, as these relationships can range from difficult to extraordinarily challenging (Steinheider et al., 2012; Yu, 2017). Law enforcement and academics occupy “very different worlds” (Burkhardt et al., 2017, p. 509). Several research traditions have led to the perception that academics are anti-police (Engel & Whalen, 2010). MacDonald (1986) discussed the concept of the dialogue of the deaf, where law enforcement and academics have defensively criticized and talked at one another, failing at effective communication. Despite these challenges, it is possible to acknowledge these difficulties and work to develop mutually beneficial relationships that allow for the successful dissemination and application of scientific research on policy and practices (Fox et al., 2020).

The collaboration between law enforcement agencies and academia to work cold cases is not new. There are examples of these partnerships across the country with varying protocols and practices, specifically in relation to the roles and responsibilities of the academic partners in the collaboration. In some cases, academics and students prepare the case files while investigators focus on traditional law enforcement tasks. Other models include university partners are who are actively involved in case management and provide analytic products, investigative recommendations, and other specific services such as forensic analysis.

READ MORE

SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 5 ™

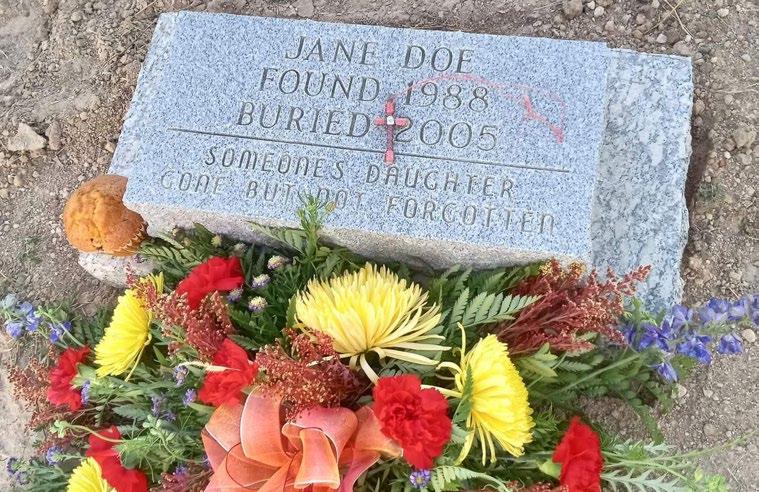

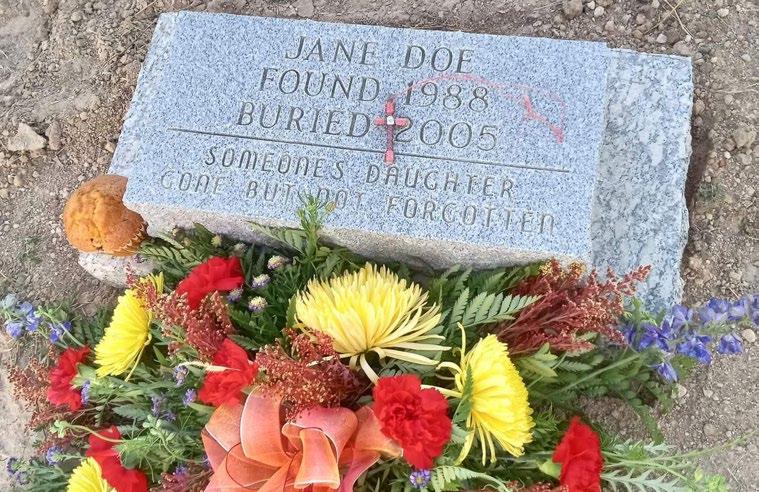

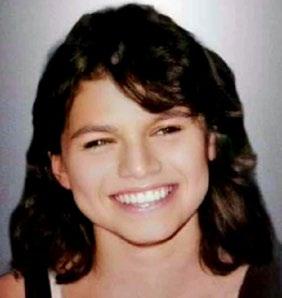

Investigative Genetic Genealogy Identifies Missing Mom of Two After 35 Years

In June of 1988, a farmer living 20 miles southwest of Springfield, Colorado called 911 to report that he had found human remains on his property. Springfield, in Baca County in extreme southeastern Colorado, had only 1,500 residents in 1988. The Baca County Sheriff’s Office and the Baca County Coroner’s Office responded to the scene where the remains were found. The remains were determined to belong to a Hispanic or Native American female in her late teens to early twenties, between 5’00” and 5’03” tall, deceased for one-and-a-half to two years. Her cause of death was unknown; however, due to her young age and location in the field, cause of death was listed as homicide in the coroner’s findings. There were no signs of injury or trauma, but only her skull and about half of her skeleton was recovered. Her skeleton had been bleached white due to prolonged exposure to the sun. All her clothing was recovered, and a quarter recovered in her pants pocket was dated 1986.

facial reconstructions were done, and her tooth fillings were analyzed. A press release at the time her remains were discovered was also fruitless, and there was no report of anyone that was missing in the Springfield area. DNA wasn’t well known in forensics in 1988 and the DNA extraction method from bones didn’t exist at the time, so Jane Doe was buried without the preservation of a blood card or a DNA sample.

Investigative Genetic Genealogy Emerges

In 2018, investigative genetic genealogy (IGG) emerged onto the scene as a new tool to identify suspects in violent crimes and to identify human remains. IGG combines the use of crime scene DNA and relative matching from directto-consumer DNA databases along with genealogical research to predict where a suspect or unidentified person may fit in a family tree. If there are no matches in the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) database, crime scene DNA samples are converted to a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) file and the file is then uploaded to the two databases authorized for law enforcement use— GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA.

These two databases give users the ability to opt-in for law enforcement access. Determining how different clusters of relatives connect can oftentimes narrow the search to a small number of family members or even to a specific person. The investigative leads are then confirmed with STR (short tandem repeat) analysis, typically done by government forensic labs, and are compared to the CODIS profile prior to a confirmed identification.

New Efforts Begin

The woman’s remains were stored in a Baca County evidence locker until 2005 when the community rallied to raise enough money for a proper burial in the Springfield Cemetery under the name Jane Doe. Prior to her burial, all leads to identify her had been exhausted and her cause of death was never determined. Dental impressions were submitted to the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), an anthropological study and

In July of 2021, the Baca County Coroner’s Office contracted with Solved by DNA, an IGG company in Colorado. In December of that year, the Baca County Coroner’s Office and the Baca County Sheriff’s Office exhumed Jane Doe to obtain DNA samples from pieces of her femur and teeth. The samples were sent to the Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI) for extraction and analysis.

READ MORE

Article: STAND BY ME SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 6 ™

CASE LAW

An officer is not required to take the potentially dangerous route of failing to shoot simply because there is reason to believe that a weapon pointed at the officer by a suspect may not be real.

• Fourth Amendment seizure by shooting a suspect

• Use of deadly force by law enforcement officers

• Brandishing a replica firearm and an officer’s use of deadly force in response

RULES

When a suspect points a firearm at an officer, the Constitution entitles the officer to respond with deadly force. The officer, however, need only have “probable cause” to believe that the weapon used by the suspect was, in fact, a real firearm. The officer is entitled to be reasonably mistaken about the nature of the threat. The fact that the weapon used appeared to be nothing more than a replica firearm does not make it unreasonable for the officer to assume otherwise.

FACTS

Gabriel Strickland was well known to the Nevada County Sheriff’s Office as a homeless man with serious mental issues, including bipolar disorder, PTSD, and anxiety disorder. Since at least 2016, he’d been in and out of custody and undergone a number of mental evaluations. On Dec. 26, 2019, he was arrested again (unknown for what) and incarcerated at a correctional facility in Nevada City, Ca. At that time, Wellpath Management, Inc., a contractor providing medical services at the facility, performed a physical and mental intake assessment, determining that Strickland was uncooperative, angry, and had active mental health issues. It was further determined that he needed an urgent and more complete mental health evaluation. However, he was released after four days by the Nevada County Superior Court following a pretrial release hearing without further mental health evaluation. Two days later, on Jan. 1, 2020, the Nevada County Regional Dispatch received reports of a man walking on a residential road near a neighboring town –Grass Valley – with “what appeared to be a shotgun” slung over his shoulder. Officers from the Grass Valley Police Department and the Nevada County Sheriff’s Office arrived at the scene, finding Strickland to be carrying what appeared to be a black plastic airsoft rifle marked with a telltale orange tip to its barrel, signifying that it was a

replica and not a real firearm. At least some of the officers recognized Strickland from prior contacts and knew that he had mental issues and thus “would” (or should) “have known that Strickland?was likely suffering from a mental health episode and would not likely respond to their commands in a ‘normal or expected manner.’” With guns drawn, five officers surrounded Strickland while repeatedly yelling at him to drop the gun. Strickland initially held the gun away from his body, telling the officers that it was a BB gun, and pointing to the orange tip as he slapped it with his hand making a noise that sounded more like plastic than metal. Taking no chances, the officers nonetheless continued to yell at him to drop the gun, that they didn’t want to kill him, and that he could have painted the orange tip. Strickland responded that he was “not doing nothing wrong.” Up to this point, Strickland merely stood there while pointing the gun toward the ground. As the officers began to tighten a circle around him, Strickland dropped to his knees. But then he started waving the gun around, pointing it at times toward the sky and then toward several of the officers. One officer deployed a Taser but missed. Seconds later, Strickland lowered the barrel, pointing it directly toward the officers, resulting in three of the officers opening fire. Struck several times, Strickland was taken to a nearby hospital where he was pronounced dead. The whole encounter, from the initial contact until Strickland was shot, lasted a little more than three minutes. A year later, Strickland’s mother, child, and estate sued the officers and their departments in federal court pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983. The district (trial) court dismissed the case, and the plaintiffs appealed.

HELD

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal affirmed. In so holding, the court first noted that shooting someone qualifies as a “seizure” of that person, and thus falls within the gambit of the Fourth Amendment. To be lawful under the dictates of the Fourth Amendment, such a seizure must be “reasonable.” A seizure is not reasonable if excessive force is used.

READ MORE

Article: Use of Deadly Force on a Suspect Armed with a Replica Firearm SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 7 ™

Your Leading Role in the DNA Evolution of FIGG Enabled Criminal Investigations

In the preface to the second edition of his book Homicide Investigation, LeMoyne Snyder wrote that “During recent years, the role of science in the field of homicide investigation has expanded enormously.” Furthermore, “…a scientific revolution is unfolding to aid in the administration of justice.” 2

That was 1967.

ANOTHER SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION?

While investigative application and greater overall understanding of DNA has increased exponentially the last few decades, another revolution in its evolution arguably began in 2018 with the emergence of Forensic Genetic Genealogy (FGG), or Forensic Investigative Genetic Genealogy (FIGG). In just five short years, FIGG has provided new life for hundreds of dead-end cold case investigations, as well as given new hope to countless families who had perhaps long-ago lost hope of locating their loved ones, identifying those responsible, or otherwise finding justice.

For instance, for over 35 years the murderer of a Niles, Michigan woman was never identified, while the victim’s husband remained the primary suspect for most of those years. The investigating agency had, unsuccessfully, done everything they could off and on over the years with what they had. They eventually resolved simply to wait for the assistance of more advanced technology to fully reexamine the existing evidence. That happened in 2020, when the genetic genealogy process and a genealogist developed a possible suspect through familial connection still in the area. A 67-year-old convicted rapist was charged and ultimately pled guilty to the 1987 sexual assault and murder – which he committed six months after being released early from a previous rape conviction.

This is just one of dozens of examples that have begun cementing the firm foundation of this next chapter of DNA, investigations, locating the lost, and finding justice. This rapidly evolving technology and adaptation process are remarkable, no doubt. But perhaps equally impressive and important to note is the level of cooperation and collaboration still ongoing, and necessary to successful implementation of these advancements. For not unlike the tireless efforts and laborious fact-finding of the oldtime gumshoe, despite its power and complexity, good

old-fashioned determination, commitment, ingenuity, diligence, and a team approach are as important as ever for FIGG to be successful.

WHAT CAN I DO?

The recent and rapid expansion in the field of FIGG has been pioneered largely by genealogists, fueled by an emerging number of forensic laboratories specializing in degraded DNA and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) generating capability. Consider that just five years after the dawn of FIGG in Sacramento County, California, hundreds of cases are currently moving through the United States and international criminal justice systems, and hundreds more are in the queue. It is crucial that law enforcement assume a leadership role in FIGG-related investigations.

First and foremost, law enforcement (investigators and administrators, alike) must have a foundational understanding of FIGG, especially concerning things like the delicate nature of working with old evidence and degraded DNA; respecting privacy and maintaining public trust concerning the sensitive nature of volunteer profiles within genealogical databases; and safeguarding investigative and prosecutorial integrity throughout the entire judicial process, just to name a few. In addition to well-grounded basic knowledge, it’s imperative that agencies nationally invest in the development of sound, sustainable, long-term policies, procedures, and protocols to assess and stratify investigations likely to benefit from the use of FIGG. The FBI has taken the lead in creating an internal policy with respect to FGG capabilities and is extending their know-how to many local agencies. However, standard operating procedures (SOP) addressing how to initiate cases using new DNA technologies, who should be assigned, and how to triage cases and/ or interface with forensic labs (public or private) should be considered vital for any agency intending to utilize the FIGG process. Further, the importance of identifying investigative and procedural benchmarks, as well as implementation and adherence to established industry standards cannot be overstated. Where and when to obtain standardized training is a key consideration.

READ MORE

SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 8 ™

Biography

of “New” Board Member: Jessica Koong

Jessica Koong is the Senior Market Development Manager at QIAGEN’s Human ID and Forensics business. With degrees in biology and psychology, she has enjoyed a 12-year career as a marketing professional in various biotech companies. In her current role at QIAGEN (the steward of GEDmatch and GEDmatch PRO), she is committed to building rigorous training programs for law enforcement and aims to democratize access to forensic application of next-generation DNA sequencing. Jessica is a community builder - as a solution provider to the law enforcement community, she believes in the additive power when different technologies join forces. Jessica is grateful to become the newly elected Chairman of the Corporate Council to the IHIA Board of Directors, and she looks forward to connecting with more solution providers in the investigative intelligence realm. Her goal is to find opportunities to amplify the presence and voice of innovative solution providers and collectively, add value to IHIA members and law enforcement community at large.

SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 9 ™

Lt. Edward Striedinger (ret) Seattle PD/Washington Attorney General’s Office

I was born in Montana and moved to Seattle, Washington at age six along with my parents and three siblings. My father was a truck driver and my mother a practical nurse. Dad was a WWII veteran who continued his service in the Army Reserve until retiring as a 1st Sergeant. Our family moved quite a bit but stayed in the Seattle area. I attended four different elementary schools, three junior high schools and two high schools, eventually dropping out after one semester of my sophomore year.

At age 16, I entered the Job Corps, based in Moses Lake, WA where I obtained a GED and trained in automotive mechanics. I went directly from there into the US Army in 1971, completing my basic training at Ft. Lewis, WA and the US Army Signal School at Ft. Gordon, GA, followed by assignment to the 4th Infantry Division at Ft. Carson, CO.

The following year, I met a wonderful woman who I immediately fell in love with! Nine days later, (yes, days) we were married, me being eighteen and her nineteen. After settling in as newlyweds at Ft. Carson, I transferred to Karlsruhe, West Germany for the balance of my enlistment. In late 1974, we returned to the Seattle area where I went to work in a factory making plastic bags. I then opened my own insurance agency, until 1979. I eventually took the test with Seattle PD. Surprisingly, I scored high enough that I placed toward the top of the eligibility register. I entered the academy in the fall of 1979. After graduation and field training, I spent the next few years working the streets until moving to the Vice Unit in 1983. This happened to be during the height of activity for what became the nation’s most prolific murderer: The Green River Killer. My work in Vice led to an invitation to join the newly formed Green River Task Force. I spent the next two years conducting body recoveries, searches and investigating suspects. It was truly an intense period of “on the job” training.

In 1986, I moved back to my own department and into the Special Assault Unit, Child Abuse Squad. This was the most gut wrenching assignment one could imagine. Every victim, as the squad name would suggest, was a child. Sitting across the table from suspects who had committed such unspeakable acts was difficult but I knew that if I did my job right, not only would these acts stop but also the child would never have to testify. It turned out that the only thing these miscreants enjoyed more than what they did to children was talking about it. Confessions were the rule rather than the exception.

A year later I transferred to the Homicide and Assault Unit. My initial training for the unit was the two-week Southern Police Institute program at the University of Louisville, KY. I later attended an IACP class on Police Medico-Legal Investigation of Death at Key Biscayne, FL. I had the privilege of spending time with Chief Medical Examiner Joe Davis, considered at that time to be the “Dean of the ME’s”. I remained a detective in Homicide until promoted at the end of 1991, then as a newly minted Sergeant, started over in patrol, later winding up in Robbery, then Domestic Violence and finally back to Homicide, where I stayed until 2007. After a couple years, I was able to move back into Investigations as a supervisor. First Robbery, then Domestic Violence and back to Homicide where I stayed until mid-2007. Short stints followed with the Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force, the Traffic DUI Squad, Major Crimes Task Force then back to Patrol as a Watch Commander. I made Lieutenant in 2015 and retired from SPD as the Commander of the Domestic Violence Unit in the spring of 2017.

In retirement, I spent two years as a Captain with the Colville Tribal Police in Eastern Washington then back to Seattle with the Washington State Attorney General’s Office as a Senior Investigator/Analyst.

Aside from policing, I spent many years as a member of the US Coast Guard Reserve, retiring as a Chief Petty Officer in 2010. I also served two terms as the President of the Seattle Police Officer’s Guild, the union representing all Seattle Police officers and sergeants.

On the home front, that nine-day whirlwind romance I mentioned previously is still going strong. We have our fifty-first wedding anniversary coming up this November. We have five now adult daughters and seven grandchildren.

As the newest Western Regional Director for IHIA, I am determined to advocate for the highest quality, up to date training in the field of Death Investigation and to make that training available to our members through affordable classes at convenient locations.

Biography of “New” Board Member: Ed Streidinger

SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 10 ™

THANK YOU TO OUR 2023 SYMPOSIUM SUPPORTERS

IHIA would like to thank our Exhibitors & Sponsors for their efforts and support of the 2023 IHIA Symposium

THANK YOU TO OUR

2023 SYMPOSIUM SUPPORTERS

SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 11 ™

AUGUST 11 - 16, 2024 HYATT REGENCY ON CAPITOL HILL WASHINGTON, D.C. 2024 IHIA INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM 30 30 A n n i v e r s a r y t h SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 12 ™

SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 13 ™

UPCOMING REGIONAL TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES

DNA AND GENEALOGY SUMMIT

October 2, 2023

Washington, D.C.

COLD CASE/NO-BODY HOMICIDE INVESTIGATION & PROSECUTION

October 30, 2023

Mesa, Arizona

ADVANCED HOMICIDE/VIOLENT CRIMES INVESTIGATIONS COURSE

December 4, 2023

Grand Prairie, Texas

MASS CASULTY RESPONSE AND ACTIVE SHOOTER INVESTIGATIONS COURSE

February 26, 2024

Largo, Florida

LEARN MORE ABOUT TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES HERE

REGIONAL MARKETING OPPORTUNITIES

As a company investing time and resources to the Law Enforcement Homicide Investigator’s field, you have an opportunity as an exhibitor or sponsor to visit with these investigators to enhance your relationship with each individual and their departments. Enhance your company’s exposure and your relationship with these investigators and their departments at one of these new events. Please contact Collette Csintyan collette@cypressplanninggroup.com

SPONSORSHIP RECEPTION $2,000 ($2000 exclusive, sponsorship will be shared with non-competing companies if exclusive is not secured.)

SPONSORED COFFEE OR SPONSORED BREAKFAST $500 each day

SPONSOR DAY $500 each day

Be the exclusive sponsor of a specific day at this event. You may come in meet with the attendees, mingle, accompany them to Lunch and so on. A few minutes will be provided to introduce yourself to the attendees and pass out information.

Investigative Quarterly Newsletter Ads

The IHIA e-Newsletter is e-mailed to over 9000 readers quarterly. The e-Newsletter is placed on the IHIA website for members. Advertising spaces are available to those companies wanting to reach the IHIA membership and are available in each issue.

Trim Size: 519 wide x 200 high (in pixels) Static Only

Rates: $350

$300

$250

• Premium Position #1

• Premium Position #2

• ALL other positions

Due Date for Reservations and Materials:

2023

November

February

Issue Due Date

December Issue

20th

March Issue

2024

20th

SEPTEMBER 2023 | PAGE 14 ™