of

Read more on page 22.

of

Read more on page 22.

Recognition of individual ICMA member achievements in the areas of career excellence, development of new talent, excellence in leadership as an assistant (regardless of title), early-career leadership, academic contributions, and advocacy for the profession.

Recognition of outstanding local government programs in the areas of community equity and inclusion, community health and safety, community partnerships, community sustainability, and strategic leadership and governance.

Recognition of retired ICMA members who have made an outstanding contribution to the local government management profession.

Recognition of the dedication of ICMA members to public service and professional management at the local level, from 25 to 55 years of service.

Reimagining community through a visionary framework emphasizing trust, connection, and collaboration.

Jon Mallon, Christa Daniels, PhD, Tom Rossman, and Michelle Kobayashi

How

Join me in congratulating the recipients of ICMA’s 2025 Local Government Excellence Awards.

BY JULIA D. NOVAK, ICMA-CM

This may be the edition of Public Management Magazine that I look forward to most each year. It’s time for us to celebrate our members and connect one another with best practices being recognized in local communities through ICMA’s Local Government Excellence Awards. The professional awards focus on individual career accomplishments—leadership, contributions to the profession, etc.— and our program awards focus on innovative initiatives or processes that benefit the community.

JULIA

D.

NOVAK, ICMA-CM, is executive director of ICMA.

Learning about our professional awards—and the prominent figures they are named for—involves a little walk through ICMA history, from legendary city manager L.P. Cookingham to our very own ethics champion, Martha Perego. I hope members will appreciate the standard set by the individuals we remember with these awards. There is a high bar established for people to be eligible for these awards and receive an honor named for some of the true icons of our profession. This year’s awardees are very deserving professionals.

As you move to the program awards, you will learn about best practices in community equity and inclusion, health and safety, community partnership, sustainability, and strategic leadership and governance. These programs are building blocks of great communities and knowing how communities of all sizes are setting the standard in these areas creates opportunities to learn and innovate in your individual context.

International City/County Management Association icma.org

October 2025

Public Management (PM) (USPS: 449-300) is published monthly by ICMA (the International City/County Management Association) at 777 North Capitol Street. N.E., Washington, D.C. 20002-4201. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C., and at additional mailing offices. The opinions expressed in the magazine are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of ICMA.

COPYRIGHT 2025 by the International City/County Management Association. All rights reserved. Material may not be reproduced or translated without written permission.

REPRINTS: To order article reprints or request reprint permission, contact pm@icma.org.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: U.S. subscription rate, $60 per year; other countries subscription rate, $155 per year. Printed in the United States. Contact: 202/289-4262; subscriptions@icma.org.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Public Management, ICMA, 777 N. Capitol Street, N.E., Suite 500, Washington, D.C. 20002-4201.

ARTICLE PROPOSALS: Visit icma.org/writeforus to see editorial guidelines for contributors. For more information on local government leadership and management topics, visit icma.org.

Early in my own career I received the Assistant Leadership Award in Memory of Buford M. Watson Jr., and it meant a lot to me because I knew Buford. He was city manager of Lawrence, Kansas, when I was a graduate student at the University of Kansas, and he was serving as president of ICMA that same year. In 1989, his untimely death at the age of 59 was a shock to our entire profession. Six months

Public Management (PM) icma.org/pm

ICMA

777 North Capitol Street, N.E. Suite 500 Washington, D.C. 20002-4201

EDITORIAL OFFICE: pm@icma.org

ADVERTISING SALES: Justin Wolfe, The YGS Group 717-430-2238 justin.wolfe@theygsgroup.com

ICMA MEMBER SERVICES: 800.745.8780 | 202.962.3680 membership@icma.org

ICMA Creating and Supporting Thriving Communities

ICMA’s vision is to be the leading association of local government professionals dedicated to creating and supporting thriving communities throughout the world. It does this by working with its more than 13,000 members to identify and speed the adoption of leading local government practices and improve the lives of residents. ICMA offers membership, professional development programs, research, publications, data and information, technical assistance, and training to thousands of city, town, and county chief administrative officers, their staffs, and other organizations throughout the world.

Public Management (PM) aims to inspire innovation, inform decision making, connect leading-edge thinking to everyday challenges, and serve ICMA members and local governments in creating and sustaining thriving communities throughout the world.

later, the city of Lawrence renamed their own Central Park in his honor. It became Watson Park, a fitting tribute to the impact he had on the city. (Not a lot of communities name parks after city managers.) And whenever I return to Lawrence, passing by the park is a reminder of the impact he had on me personally. Buford’s son Mark and grandson Kevin have both been active and engaged ICMA members as well, and I’m

proud that we have an award in memory of their father/grandfather.

Awards can connect what is “best” about our past to what is “best” about today, and I appreciate that connection. The standards set by the people and programs being recognized in 2025 set a new standard for us to strive for in the future. I hope you are inspired, and I hope that you consider how your own contributions are shaping your

community, your organization, and your profession. Each of us has the potential to make a positive and lasting contribution. It’s a reminder of the importance of the work we do.

Thanks for taking the time to read about your remarkable colleagues and the communities being honored. I can’t wait to see them walk across the stage in Tampa!

PRESIDENT

Tanya Ange*

County Administrator Washington County, Oregon

PRESIDENT-ELECT

Michael Land*

City Manager Coppell, Texas

PAST PRESIDENT

Lon Pluckhahn* City Manager Vancouver, Washington

VICE PRESIDENTS

International Region

Colin Beheydt

City Manager Bruges, Belgium

Doug Gilchrist

City Manager Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada

Lungile Dlamini

Chief Executive Officer

Municipal Council of Manzini, Eswatini

Midwest Region

Michael Sable*

City Manager Maplewood, Minnesota

Jeffrey Weckbach

Township Administrator Colerain Township, Ohio

Cynthia Steinhauser*

Deputy City Administrator Rochester, Minnesota

Mountain Plains Region

Dave Slezickey* City Manager The Village, Oklahoma

Pamela Davis

Assistant City Manager Boulder, Colorado

Sereniah Breland City Manager Pflugerville, Texas Northeast Region

Dennis Enslinger

Deputy City Manager Gaithersburg, Maryland

Steve Bartha* Town Manager Lexington, Massachusetts

Brandon Ford

Assistant Township Manager Lower Merion Township, Pennsylvania

Southeast Region

Jorge Gonzalez*

Village Manager Village of Bal Harbour, Florida

Eric Stuckey

City Administrator Franklin, Tennessee

Chelsea Jackson

Deputy City Manager Douglasville, Georgia

West Coast Region

Jessi Bon

City Manager

Mercer Island, Washington

Nat Rojanasathira*

Assistant City Manager Monterey, California

Elisa Cox*

Assistant City Manager

Rancho Cucamonga, California

*ICMA-CM

** ICMA Credentialed Manager Candidate

ICMA

Julia D. Novak, ICMA-CM Managing

Lynne Scott lscott@icma.org Brand Management, Marketing, and Outreach

Senior Managing Editor Kerry Hansen khansen@icma.org

Senior Editor Kathleen Karas kkaras@icma.org

Graphics Manager Delia Jones djones@icma.org

Design & Production picantecreative.com

BY JESSICA COWLES

The year 2013 was the year of the book, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead; the iPhone 5s; the word “selfie” went into the dictionary; and when ICMA’s Code of Ethics review cycle first began!

Ensuring the Code’s relevance for all members working in service to a local government had been an ad hoc effort up until that point, with just a few revisions from 1924 through 1998.1

ICMA’s Committee on Professional Conduct (CPC) is a standing committee of the Executive Board (board). The CPC developed a plan to review a few principles of the profession at a time by engaging the membership through feedback on what works, what is missing, and what should be revised. This comprehensive effort had never been done before, and it was responsible to assess it just as local governments do for their own policies.

ICMA’s Constitution requires members vote by ballot to change the Code’s tenet language; the board has the authority to revise tenet guidelines, and this usually occurs at the CPC’s recommendation. As background, the tenets express the values of the local government management profession while the guidelines assist members in understanding their ethical obligations as outlined in the tenet.

Through at least 103 sessions, 11,000 member engagements such as attendance at a discussion or via written comments, and more than 10 feedback surveys, we have completed the review of all 12 tenets of the Code and their associated guidelines with the membership!

JESSICA COWLES is director of ethics at ICMA (jcowles@icma.org).

This past 14 months, the CPC completed the final two tenets for membership review: Tenet 8 (professional development) and Tenet 10 (job interference). The CPC facilitated conversations with members during the Local Government Reimagined Conferences and state association meetings, then invited all members to share feedback through a survey.

The CPC drafted proposed revisions and surveyed the membership again. The CPC further refined the tenet language, and members who responded to the final survey supported the CPC’s proposed changes

to Tenets 8 and 10. The board approved placing the revisions on the May 2025 ICMA annual election ballot. Members overwhelmingly voted in favor of the revisions to Tenet 8 (95% approval) and Tenet 10 (87% approval). The following is the updated Tenets 8 and 10 language:

Tenet 8. Continually improve professional capabilities and those of others while fostering growth and development through ethical leadership and effective management practices.

Tenet 10. Oppose efforts to interfere with professional responsibilities by consistently executing official duties, policies, and processes with an unwavering commitment to unbiased public service.

8,

Based on member discussion at eight conferences and via three online surveys, the CPC drafted proposed revisions to Tenets 8 and 10 guidelines, then the board voted to approve them. Members responding to the final survey approved the proposed guideline language. (For Tenet 8, 85% SelfAssessment and 81% Professional Development; and for Tenet 10, 81% Information Sharing and Feedback and 83% Personnel and Operational Matters). The comparison between the former and revised/current guideline language can be seen in Figure 1.

The CPC also received significant feedback about revisiting Tenet 3’s guidelines on Professional Respect and Conduct Unbecoming. The language of Tenet 3 is “Demonstrate by word and action the highest standards of ethical conduct and integrity in all public, professional, and personal relationships in order that the member may merit the trust and respect of the elected and appointed officials, employees, and the public.”

These two guidelines warranted review because they have been cited in ethics complaints, i.e., unsolicited public commentary about a colleague’s organization; managers whose conversations with governing body members and staff without informing their colleagues had the effect of undermining their successors; running for elected office in retirement in the community where the member recently served; and unprofessional conduct at work events. The comparison between the former and revised/current guideline language can be seen in Figure 1.

These revisions mark the completion of the Code review effort. To view a complete history of the Code, visit icma.org/page/ history-icma-code-ethics.

I’d like to extend a big thank-you first to our members for providing thoughtful feedback and suggested revisions to make sure the CPC and board got it right! I share congratulations especially to current and former CPC and board members for prioritizing this when there are many other issues competing for their time. ICMA’s former managing

Tenet 8

Self-Assessment. Each member should assess his or her professional skills and abilities on a periodic basis.

Professional Development. Each member should commit at least 40 hours per year to professional development activities that are based on the practices identified by the members of ICMA.

director of member services and ethics, Martha Perego, spearheaded the initiative for many years and the profession extends a big thanks for her leadership in ensuring the Code stays relevant for the next generation of local government practitioners.

ENDNOTE

1 https://icma.org/articles/pm-magazine/ethics-mattertm-icma-code-ethicsretrospective-past-12-years

Self-Assessment. Members should evaluate and enhance their professional skills and competencies annually through self-reflection and by proactively soliciting feedback.

Professional Development. Members should stay informed about emerging issues, practices, and challenges, actively engage in development activities year-round, and support others in enhancing their professional and ethical competencies.

Information Sharing. The member should openly share information with the governing body while diligently carrying out the member’s responsibilities as set forth in the charter or enabling legislation. This was the only guideline to Tenet 10.

Tenet 3

Former

Conduct Unbecoming. Members should treat people fairly, with dignity and respect and should not engage in, or condone bullying behavior, harassment, sexual harassment or discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, age, disability, gender, gender identity, or sexual orientation.

Professional Respect. Members seeking a position should show professional respect for persons formerly holding the position, successors holding the position, or for others who might be applying for the same position. Professional respect does not preclude honest differences of opinion; it does preclude attacking a person’s motives or integrity.

Information Sharing and Feedback. The member should collaborate with the governing body to establish clear communication protocols for effective, equitable, and transparent information sharing and reciprocal feedback.

Personnel and Operational Matters. The member shall lead personnel and operating decisions consistent with responsibilities established in the charter or enabling legislation without interference from the governing body.

Conduct Unbecoming. Members should treat people fairly, with dignity and respect and should not engage in, or condone bullying behavior, harassment, sexual harassment, unwelcome contact, advances, or discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, age, disability, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, or veteran status. Members should foster respectful, inclusive environments in all professional and social settings.

Professional Respect. Members should demonstrate professional respect for colleagues, including predecessors, successors, and others who might be candidates for the same position. Professional respect does not preclude sharing honest differences of opinion privately between colleagues; it does preclude attacking a person’s motives or integrity, undermining them, or actively interfering with their work.

Showing professional respect involves acknowledging power dynamics between different career points and tenures. Undue influence, abuse of power, and intimidation are inappropriate and must be avoided.

A member no longer working in service to a local government should be mindful of professional respect before running for elected office in a jurisdiction where they recently served.

The Current State of Student Debt and Forgiveness | Savi

October 2 | Free Webinar

A Tale of Two Cities: Data That Reveals Why/When/How AI Deployments Fail Or Succeed in US Local Government | GovAI

October 7 | Free Webinar

Effective Supervisory Practices

October 8–December 17 | Training Series

A Budgeting Guide for Local Government

October 9–23 | Training Series

Beyond Access: Advancing Digital Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusive Engagement in Local Government | CivicPlus October 14 | Free Webinar

Asking Police Chiefs the Right Questions October 21 | Webinar

Emerging Leaders Development Program 2.0

January 27–June 30

Elevate your career with this six-month experience designed for early- to mid-level local government professionals aspiring to leadership roles. Through interactive workshops, flexible learning tracks, mentorship, and networking opportunities, develop essential skills in adaptive leadership, digital innovation, and community resilience.

Opening Session Begins April 15–17

Develop essential local government competencies through this one-year intensive program. Participants engage in 12 courses, interactive online learning, two in-person events, and a capstone project, gaining practical skills in ethics, communication, strategic leadership, and community engagement. Apply by December 5 to secure your spot!

For a full listing of events and details, visit icma.org/events. Shop all courses at learning.icma.org.

Title Sponsor

Champions

Sponsors

Supporters

Sponsors as of September 17, 2025

BY THE TOWN OF CARY, NORTH CAROLINA

What happens when a town decides to write its own story instead of letting others write it for them? Cary’s journey shows how vision and intentional leadership, through a culture where anyone can lead from their seat, can transform not just a community but the way we all think about what’s possible within local government.

The Top of the Arc: Cocreating a More Innovative, Adaptive, and Effective Local Government (Radius Book Group, 2025) is our contribution to the profession. Though our town manager, Sean R. Stegall, ICMA-CM, is credited as the author, the copyright belongs to the town because the voices in the book—council, staff, and residents—are what make it Cary’s story.

Like most of you, we work within a council–manager form of government. Our elected council sets policy, and nearly 1,300 staff carry it out. Cary sits in the heart of North Carolina’s Research Triangle and is often recognized among the nation’s best places to live. We’re grateful for those honors, but accolades don’t tell the full story.

For the past 17 years, Cary has maintained a steady population growth rate of 2 to 2.5% annually. That stability followed decades of hypergrowth that saw the town expand from 1,000 residents in the 1960s to more than 190,000 today. The shift from expansion to maturity brought new realities: redevelopment pressures, tougher choices, and at times humbling results at the ballot box. For a community once fueled by rapid growth, it meant learning to evolve differently.

It was in this context that council launched Imagine Cary in 2012, the most ambitious planning process in our history. Thousands of residents joined with council and staff to shape a single vision through 2040. With over 60 nationalities represented and one in four residents born outside the United States, creating a shared pathway forward was both daunting and energizing.

In 2016, council charged our town manager with making that vision real. Out of that challenge came a phrase we’ve carried ever since: “We are creating the local government that

doesn’t exist.” At first, it was casual, but people responded. Some heard a call to aim higher. Others pictured a government so seamless it hardly registered. What mattered most was the permission it gave us all to imagine a government that could be more adaptive, more human, and more effective than what we had known.

That spirit, and the culture we built together through the OneCary Toolkit, ultimately gave us the courage to share our story in The Top of the Arc.

Cary’s journey shows how vision and intentional leadership can transform not just a community but the way we all think about what’s possible within local government.

“The launch of Cary 311 was a confirmation of this. Staff developed new skills, got new titles, and worked with new equipment. … [That] paid off with increases in confidence and pride and a sense of empowerment.” —From Chapter 10, “The Top of the Arc and The Importance of Reinvention”

The first expressions of Imagine Cary weren’t abstract policies but projects that reshaped how our community works and lives:

Cary 311. A 311 system typically functions as a call center for non-emergency needs. We wanted ours to be something more. Today, each case is owned by a member of our citizen advocate team until it is resolved. Often the Salesforce case becomes a cross-department collaboration across all levels, reminding us that trust is built as much among colleagues as with residents.

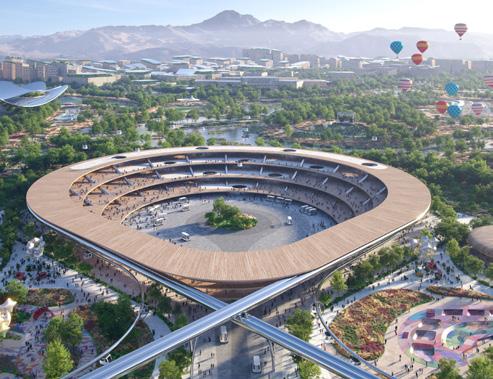

Downtown Cary Park. What began as a modest greenspace idea two decades ago grew into a $70 million civic heart launched in 2023. Hosting nearly 500 events a year— from fitness classes to art displays and concerts to festivals—it has redefined Downtown Cary as a destination and given our community a new center of gravity. Its Nest play area, named the nation’s best public playground by USA TODAY readers in 2025, is only part of the story.

Fenton. For decades, Cary was defined by single-family neighborhoods and a “drive-through” downtown. Then, on 92 acres at our eastern gateway from Interstate 40, council approved the town’s first vertical mixed-use district. Nearly $1 billion in investment has created a new regional draw with a walkable hub of housing, retail, offices, and public space. More than an economic project, it marked the moment Cary embraced urban form and a willingness to grow up as well as out.

Each of these projects stretched us with council making bold choices, staff providing the expertise to carry them out, and residents trusting their government to deliver something beyond the ordinary.

“It’s easy to view referendums in up-or-down victories or defeats. But none of the referendum projects, which were

inspired by the Imagine Cary Community Plan, have been completely wiped off the table forever. Only the proposed specific funding mechanism that would have propelled the projects forward was stopped.” —From Chapter 8, “Changing the Horizons”

In 2024, Cary voters rejected $590 million in bond referendums for parks, recreation, and housing. For decades, bonds had passed by wide margins. This time, after a tax increase and earlier bond approvals, many residents shared they had simply reached their limit. Voter fatigue was real.

For a community used to strong support on these referendums, it was humbling. But it also was clarifying. As Cary has matured, we’ve learned that choices get harder, not easier. And that lesson isn’t only for elected officials or senior managers. In our culture, anyone can lead, whether in a council seat, a crew leader’s role, or through influence without a formal title. Leadership is about recognizing when a community says, “not now,” and responding with candor, adaptability, and persistence.

“Aiming for excellence and then achieving that goal requires dreaming and analyzing, investing and taking risks, and embracing responsibility. Repeating that process requires building a culture that embodies and sustains our commitment to excellence, to staying at the top of the arc.” —From Chapter 7, “Consensus Building and Development”

Projects can change landscapes, but culture sustains excellence. The values shared in our OneCary Toolkit, detailed in The Top of the Arc, remind us that innovation doesn’t come from a handbook but from empowering staff to lead at every level. One of our favorite commitments is simple: “We reserve the right to get smarter as we go.” That mindset has freed us to adapt, to learn publicly, and to evolve without apology.

Across America, redevelopment pressures, financial limits, and rising expectations are testing local governments. Cary’s story is not a prescription, but an encouragement: we’re all capable of creating the local government that doesn’t exist when we choose to cocreate with our elected officials, our staff, our residents— and one another.

The Top of the Arc is Cary’s story told through the voices of past and present councilmembers, our staff, and our community. We share it not as an ending, but as an invitation to peers across the profession. Sustaining excellence isn’t about preserving what is. It’s about creating what could be.

Read Cary’s journey in The Top of the Arc, and then share your own, so together we can keep creating the local government that doesn’t exist.

A community-driven transformation to promote sustainability, biodiversity, and resource efficiency in West Burlington, Iowa

BY GREGG MANDSAGER, ICMA-CM

In West Burlington, a meaningful transformation is taking root—not just in our soil, but in our vision for the future. Across our community, native prairie plants and grasses are being planted in parks, along trails, and even around our wastewater treatment plant. The city has launched several native prairie and pollinator park projects, transforming public spaces into thriving habitats for pollinators with resilient native plants, all while creating places for community enjoyment. These micro prairies and pollinator parks aren’t just beautiful; they’re purposeful. They reflect a commitment to sustainability, habitat restoration, and practical stewardship of city resources.

This work is rooted in partnerships—with local experts, passionate volunteers, and organizations like the University of Iowa’s Institute for Sustainable Communities (IISC). Through this growing network, we’ve created something uniquely West Burlington: a city-led, community-supported approach to conservation and smart land use.

We’ve teamed up with Sam Hollingsworth of Prairie Roots for prairie design and installation, while master gardeners from the community generously gave their time to help get the plants in the ground. City staff, particularly from public works, have been essential in site preparation, mulching, watering, and maintenance. Together, we’re proving that even small urban projects can have meaningful environmental and social benefits.

GREGG

MANDSAGER, ICMA-CM, is city administrator of West Burlington, Iowa, USA.

We’ve launched several prairie initiatives across the city: City Hall and Trail Micro Prairies: Compact, densely planted gardens featuring native grasses and wildflowers. These vibrant sites were designed in partnership with Prairie Roots and installed with help from local volunteers and city staff.

Pat Kline Park: A larger prairie restoration designed by IISC students and faculty, including Professor Mike Fallon. Their work included research, design, and community outreach—culminating in a new kind of park that prioritizes ecology and education.

Wastewater Treatment Plant: Native habitat has been added both inside and outside the plant’s perimeter. A short walking path allows residents to explore this natural space and see native wildflowers in bloom and pollinators in action.

Native plants like milkweed, coneflowers, little bluestem, and black-eyed Susans are well-adapted for Iowa’s soil and climate, offering a sustainable and efficient alternative to traditional turf grass. Native plantings are far more resilient and require less water, mowing, and maintenance once established. Their deep root systems:

• Help retain soil and prevent erosion.

• Improve water infiltration and reduce runoff.

• Store carbon and support healthier air and water.

• Survive droughts and extreme weather.

By shifting from turf to prairie in select public spaces, we’re saving time, fuel, and money—freeing up resources for other city needs, such as road repairs and community projects.

Beyond their practicality, prairies are essential to restoring biodiversity. They provide vital habitat for pollinators—bees, butterflies, birds, and other species whose populations are declining due to habitat loss and pesticide use. By integrating prairies into our public spaces, we’re helping pollinators thrive while improving soil health, filtering stormwater, and reducing maintenance costs. In a time of increasing environmental challenges, small local actions like these help build resilience.

Native plantings are far more resilient and require less water, mowing, and maintenance.

Pollinators are critical to ecosystems and agriculture, yet many are under threat. Cities like West Burlington can play an important conservation role by restoring native habitats in public spaces. Our plantings include a wide range of species that bloom from early spring through late fall, beautifying the city and ensuring a continuous food source for pollinators throughout the growing season.

Educational signage will soon be added to each prairie site, highlighting what’s growing, why it matters, and how residents can engage with these spaces. We hope these natural areas will not only enhance beauty and biodiversity but also inspire learning—serving as living laboratories for local students, scout troops, gardeners, and nature lovers.

Whether you’re walking the trail, watching butterflies, or just enjoying a quiet moment outdoors, these spaces offer something for everyone and demonstrate our shared responsibility as stewards of the land and city resources.

West Burlington’s prairie and pollinator projects are a testament to what’s possible when cities think long term and work collaboratively. With thoughtful planning and community partnerships, we’re making the most of our public spaces—saving resources, supporting wildlife, and enhancing quality of life. By restoring a piece of Iowa’s natural landscape, West Burlington is investing in both its environment and its future, creating healthier spaces for generations to come.

As we continue to grow as a community, we’re doing so in a way that respects and restores Iowa’s natural heritage. Our small prairies may not cover vast acres, but they carry a big message: that sustainability starts at home, and that every square foot of native habitat matters.

BY RICH MORAHAN

RICH MORAHAN writes frequently about security and marketing for a number of industries, including ATMs, information management, petroleum and propane distribution, and vending. Contact him at 617-2400372 or rmwriteg@ gmail.com, or visit rmorahan.com.

For information about enclosures and cages, contact:

D&M Manufacturing backflowtheft.com info@backflowtheft.com

866-308-9911, 951-674-1908

Safe-T-Cover safe-t-cover.com

customerservice@ safe-t-cover.com

800-245-6333

For information about security locks, contact: Lock America, Inc.

laigroup.com sales@laigroup.com

800-422-2866

Recently, the Denver city council passed new regulations on scrap metal transactions in an effort to deter scrap metal theft. As reported by Denverite and Colorado Public Radio, this proposal requires scrap dealers to:

• Refuse all cash transactions.

• Keep detailed records of purchases from scrap sellers.

• Collect signed affidavits explaining how and where the scrap metal was obtained.

• Keep copies of photo IDs and license plate numbers.

Officials with the department of excise and licensing and the Denver police department would have the power to inspect transaction records and inventory at scrap merchants. Noncompliance could result in fines of up to $5,000 per violation per day, as well as license revocation.

Last year I reported on the increase in fire hydrant thefts, and some of the efforts to stem the tide. In the past year, some water commissions have taken the initiative to protect their assets.

Marko Mlikotin of Randle Communications notes the success of its client, Golden State Water Company of San Dimas, California, installing hydrant shields with locks. “After experiencing 396 fire hydrant thefts in 2024, resulting in a loss of $2 million, thefts have decreased significantly in 2025. This is partly due to the installation of security devices such as collars and tracking devices on fire hydrants, increased policing, and a public education campaign that discourages scrap yards from accepting stolen property and encourages customers to report thefts in progress.”

Shields and locks, increased law enforcement and community awareness, and close monitoring of scrap metal dealers all appear to have played a part in reducing theft.

Regulations such as Denver’s can deter threats to a city’s infrastructure, but a hardened target remains an organization’s first line of defense against theft. Denver is not alone. From Columbine and Littleton in Colorado to Southern California to Florida, scrap metal theft can cost municipalities thousands of dollars, even when there is only a small return for the criminal.

This article will focus on measures to deter theft of brass valves and water infrastructure elements. I’ll highlight some basic protective steps for copper in my summary. Enhanced regulations, heightened public awareness, and restrictions on cash sales can deter crooks, but the major tactic to protect backflow valves and water infrastructure is hardening the target with cages, enclosures, and locks.

Communities and water commissions have a variety of upgrade paths to protect their assets. Companies such as D&M Manufacturing of Lake Elsinore, California, manufacture a variety of protective devices, from open cages to sealed boxes and custom shackles.

Source: Randle Communications

A cage secured with a high-security “hockey puck” lock provides a straightforward upgrade. D&M uses high-security locks from Lock America, Inc. of Corona, California, for all its products. These locks feature tamperresistant keyways and key control with key registration to each customer. D&M also offers customer security boxes with shielded locks and a retrofit shackle option, a

cost-effective upgrade that is also based on Lock America’s lock system.

Safe-T-Cover, located across the country from D&M in Nashville, Tennessee, produces a wide range of enclosures, including some especially suited for harsh environments in the northern U.S. As an additional option to their enclosures, Safe-T-Cover offers a patented MUNILOK system, which addresses the frequent issue of customers not locking their enclosures. MUNILOK automatically secures the enclosure at installation and integrates with a city’s existing utility vault key system, giving authorized personnel quick access without compromising security.

A system for smaller applications features a flushmounted locking rod and tamperresistant puck-style lock that eliminates exposed hasps, reducing vulnerability to bolt cutters.

Safe-T-Cover has recently introduced a firerated enclosure built with NFPA 285compliant panels. Ideal for urban areas and public spaces, this enclosure resists flame spread and discourages misuse while offering the durability and security SafeTCover is known for.

In addition to securing hardware on the spot, a number of municipalities, such as Glendale, Arizona, make additional suggestions:

• Paint, coat, or label valves and pipes to decrease resale value.

• Sample, label, or code to brand contraband.

• Post warnings and use surveillance when possible.

Unlike backflow valves and hydrants, which are cumbersome objects that can be shielded and locked, copper wire is everywhere. Cities can only secure a fraction of the target.

It’s possible to increase the security for traffic and electrical boxes, but the more practical tactic to prevent copper theft is to attack the dealer, as the recent multi-department investigation in San Jose, California, demonstrates.

Detectives with the police department’s vice unit targeted several recycling centers in the city following an increase in copper wire thefts. Undercover officers conducted a successful sting operation with spools of copper wire, electronic components, and metal items to sell as “stolen” property, successfully busting some shady scrap metal dealers with the help of the department’s financial crimes unit and the city’s department of transportation.

“If you do business in San Jose, you have to follow the law,” said Police Chief Paul Joseph in a prepared statement. “We will not tolerate crime, whether you are the one stealing the copper wire or purchasing it with the intention of making a dime off of victims.”

At a roundtable of business and municipal leaders in June, California Attorney General Rob Bonta issued a new law enforcement bulletin that summarizes the California statutes related to copper wire theft and laws governing junk dealers’ and recyclers’ obligations to collect and report information on copper transactions.

The solution here appears to be enhanced enforcement at the dealer market especially by prohibiting cash sales, requiring identification for transactions, and increased public awareness. There are copper disguises (spray painting to mimic plastic, for example) to protect the target, but until the price level drops below the risk level, copper will attract low-level crooks and shady scrap metal dealers.

Fire hydrants and back flow valves appear to lend themselves to hardware protection, but increased awareness and proactive tactics may make a dent in the copper theft market too.

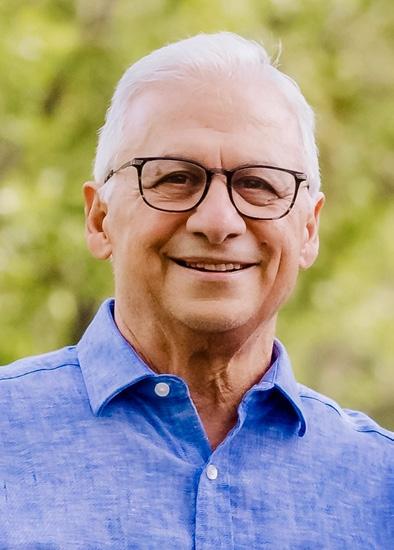

As the city manager of McKinney, Texas, Paul G. Grimes exemplifies commitment to excellence in local government and dedication to creating thriving communities. His leadership style has transformed McKinney’s workplace culture and improved countless lives across the community he serves.

For nine years, Grimes has guided McKinney through transformational changes that have strengthened the larger community, and his leadership style has been central to his success. After assuming the role of city manager, Grimes initiated efforts to gather staff input and promote organizational cohesion. Through personally leading nearly 50 small group meetings with employees, four core organizational values were identified: respect, integrity, service, and excellence. These values were foundational to all the positive changes that followed.

managers and an emerging leaders course for promising junior staff. Partnering with the University of Texas at Dallas, employees gained access to graduate certificate programs in local government management. He also started a “buddyto-boss” course for employees promoted into their first supervisory role. Grimes prioritized staff development by establishing an organizational development department that now offers more than 100 classes and workshops to employees each year.

His legacy of leadership has left a longstanding impact on the community.

Grimes’s leadership emphasizes the importance of input from employees at every level. He led the establishment of strategic working groups like the executive leadership team and department leadership teams to carry out a philosophy that embodies a shared approach to leadership. There are several successful outcomes generated from his leadership efforts that highlight the excellence achieved in his career, some of which are outlined here.

Staff development. Grimes implemented several initiatives to promote opportunities for staff to learn and grow. They include the establishment of a leadership academy for supervisors and

Workplace culture and communication. Grimes’s organizational vision is focused on the power of creating strong relationships to build trust and increase efficiency. By inviting staff to provide input at every level, his efforts led to improved relationships across departments and increased employee engagement to more than twice the national average. In response to a growing need to improve communication, Grimes implemented several key strategies, ranging from informal breakfast meetings to formal organizational “cascades” for staff across departments to connect and discuss relevant issues with one another.

A number of city-wide infrastructure improvements have been made, such as the construction of a new city hall complex; the completion of multiple capital projects, including approval of a new airport passenger service terminal; the improvement of recreational centers; and securing long-term funding for road maintenance. As these projects were completed, a total of $96 million in grant support was secured, ensuring a decreased tax burden for residents. Furthermore, in 2024, USA Today named the city of McKinney one of the “Top Places to Work in America.”

This award was established in memory of former ICMA Executive Director Mark E. Keane. With funding support from MissionSquare Retirement, this award recognizes an outstanding local government administrator who has enhanced the effectiveness of government officials and consistently initiated creative and successful programs.

The attempt to improve communication efforts was not limited to employees. By increasing regular communications with local nonprofits and organizations, trust has grown between the city and the community. For example, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, McKinney’s vaccination hub administered 70,000 shots to residents through efforts led by Grimes in partnership with local community organizations.

Community-driven results. Throughout this time as city manager, Grimes has achieved real results that have had longstanding effects on the lives of residents. The city of McKinney has repeatedly received national recognition for the quality of life it offers the community.

Under City Manager Paul Grimes, McKinney has seen notable success. His legacy of leadership has driven significant achievements and left a longstanding impact on the community, and his career has embodied excellence in local government.

Assistant Town Manager, Sahuarita, Arizona, USA

Beth Abramovitz recognizes that tomorrow’s leaders can often be found among today’s staff. She doesn’t let current job titles or responsibilities hold people back from pursuing their passions.

Abramovitz came into her role as assistant town manager from a management position in the Sahuarita public works department. She knows firsthand the value of developing internal talent and finding opportunities for local government professionals to thrive outside of traditional career paths. She currently oversees four departments with eight employees in leadership roles, four of which were promoted into these positions under Abramovitz’s leadership. She is the kind of leader who recognizes, encourages, and develops the talent that surrounds her. One of her colleagues noted that in his interview Abramovitz described her leadership style as hiring the best people to do all the things she doesn’t know how to do and trusting them to do the job effectively and efficiently. This leadership style is demonstrated through her ability to mentor others and open doors to new opportunities.

An example of this leadership and mentorship can be found in the career pathway of the town’s community development deputy director. He had a background in planning, but he sought to do something different. After finishing a program in human resources management, he found himself in a dead-end position in

another community. When an opportunity opened in Sahuarita, Abramovitz quickly hired him and provided him with opportunities in public works, planning, and parks and recreation. In addition, she found new projects related to the town’s human resources that allowed the employee to explore his interests beyond the confines of the role. As a result of Abramovitz’s encouragement and professional support, he is now part of the leadership team in the town manager’s office and is able to pursue multiple areas of interest and grow his local government expertise.

In addition to helping staff explore new areas and obtain promotions, Abramovitz encourages her staff to join professional associations and participate in events outside of the employee’s immediate field but still related to local government. She consistently helps others improve their presentation skills and expand their networks by providing opportunities for staff to present at professional conferences or to community groups. She helps employees improve their job performance, enhance their knowledge of interdepartmental functions, and develop greater confidence in themselves and their work.

She is the kind of leader who recognizes, encourages, and develops the talent that surrounds her.

from the Women’s Transportation Seminar, and the Jane L. Morris Scholarship from the Arizona City Management Association.

Abramovitz’s ongoing assessment of internal talent to offer relevant career opportunities has improved Sahuarita’s culture, making it a valued workplace where talent is recognized.

This award goes to an outstanding local government administrator who has made a significant contribution to the career development of new talent in professional local government management, in honor of former ICMA President L. P. (Perry) Cookingham, who is credited with creating the local government internship.

Abramovitz is not only a leader among staff but a leader within the community as well. She guided the town’s parks and recreation department through a collaboration with a local mining company and a nearby Indian reserve to develop a park on a former smelting site. This project earned a local award for its exemplary level of collaboration, cooperation, and communication.

While her projects have been recognized, she herself has also been lauded for her exceptional leadership and dedication. She received the Professional Manager of the Year award from the Arizona Chapter of the American Public Works Association, the Woman of the Year award

ASSISTANT EXCELLENCE IN LEADERSHIP AWARD IN MEMORY OF BUFORD M. WATSON JR.

Assistant City Administrator, O’Fallon, Missouri, USA

Lenore K. Toser-Aldaz embodies the essence of service. She works tirelessly behind the scenes to elevate everyone around her and is fully dedicated to helping employees, supervisors, and elected officials achieve success in their roles. In times of need, she is always willing to step up and support the O’Fallon community. Her dedication and tireless work ethic are a model for all employees.

Serving as O’Fallon’s assistant city administrator since 2011, Toser-Aldaz’s calm and steady leadership has helped the city navigate challenging times and ensure that the needs of residents and businesses were met despite leadership changes. Her thoughtful guidance provided stability and reassurance for staff and elected officials as she was called upon to serve as interim city administrator three times over the last 14 years. This leadership has contributed to minimal staff turnover, which has ensured consistency and excellence in service delivery for the community. Her reputation as a trusted and selfless leader preceded her time in O’Fallon as these traits were recognized in previous roles in Clayton, Missouri; Johnson County, Kansas; and Kansas City, Missouri.

Toser-Aldaz’s leadership goes beyond city staff and has extended to the community and outside organizations. Through oversight of both planning and development and economic development, Toser-Aldaz has had a hand in virtually every major development in the city during her tenure. With her ability to navigate complex projects and communicate issues simply and effectively, she has played an integral role on the city’s negotiating team

to help bring quality projects to fruition. She has also served on the board of directors for both the St. Louis Area City Management Association, culminating as president; and the Missouri City Management Association, from which she received the organization’s highest leadership award for assistants.

In overseeing various city departments, it’s clear that her support and guidance have propelled the city staff forward. In keeping with the city’s commitment to transparency and community engagement, the communications department operates a 24-hour television channel that airs all city meetings, as well as original programming and public service announcements. The department has also recently redesigned and relaunched six websites to ensure accessibility and ADA compliance ahead of regulatory deadlines. The human resources department has conducted multiple salary studies to ensure fair and competitive compensation, and the department has updated policies and improved recruitment processes. The information technology department transitioned to cloud-based infrastructure and implemented a work-from-home program, which also contributed to staff recruitment, retention, and work-life balance.

Her calm and steady leadership has helped the city navigate challenging times, and her thoughtful guidance provided stability and reassurance.

This award, commemorating former ICMA President Buford M. Watson Jr., honors a local government management professional who has made significant contributions toward excellence in leadership as an assistant (regardless of title) to a chief local government administrator or department head.

Through this visionary leadership, she has distinguished herself as a principal member of the team and an asset to the organization. Her achievements make O’Fallon a better place to live, work, and play now and for the future.

ACADEMIC AWARD IN MEMORY OF STEPHEN B. SWEENEY

Associate Professor and Associate Director, School of Public Affairs (Master of Public Policy and Administration Program), University of Utah

Jonathan M. Fisk serves as the associate director for the School of Public Affairs at the University of Utah. Previously, he was an associate professor at Auburn University, where he contributed significantly to student development. Drawing on his extensive experience, professional network, and resources, Dr. Fisk demonstrates a strong commitment to supporting the next generation of leaders in local government management.

Fisk first became intrigued by local government management when receiving his master of public administration from the University of Kansas and through experiences such as his work as a research associate with the League of Kansas Municipalities. He earned his PhD from Colorado State University and has focused his career on encouraging students to engage in public service.

students were accepted as ICMA Local Government Management Fellows and have since launched their careers across the country. Fisk worked tirelessly to assist in securing impactful work opportunities for his students so they could gain knowledge, expand their skill sets, and advance their network of local government professionals.

At Auburn University, Fisk taught courses in leadership, public administration, public personnel administration, and ethics while inspiring students to pursue a career in local government. Notably, he exposed aspiring local government leaders to available resources like the Alabama City-County Management Association (ACCMA) and ICMA. Fisk’s encouragement of local government initiatives and ongoing support for his students is reflected in their achievements and engagement with insightful career opportunities. Over the years, many of his students have participated in AACMA and ICMA conferences and events. Ten of his

One of Fisk’s key accomplishments as an associate professor is exemplified in his collaboration with students to create an ICMA Student Chapter at Auburn University. The students who worked alongside Fisk became the chapter’s first president and vice president, and he served as the chapter’s faculty advisor during his tenure. Through his collaboration with the Government and Economic Development Institute at Auburn University came the development of a scholarship program that supported the annual part of five students in the ACCMA Local Government Professional Management Certificate Program.

Fisk has consistently demonstrated a strong commitment to preparing the next generation of local government management professionals for success.

excellence from Auburn University and the ACCMA.

Established in the name of Stephen B. Sweeney, the longtime director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Fels Institute of Government, this award is presented to an academic leader or academic institution that has made a significant contribution to the formal education of students pursuing careers in local government.

Fisk has facilitated the integration of students into the local government management profession through participation in meaningful experiences, though his impact extends beyond his efforts to expose his students to key opportunities for professional development. His academic accolades include the inclusion of his publications across prestigious journals and policy blogs, such as the American Society for Public Administration (ASPA). He has served on ICMA’s Graduate Education Advisory Committee and served as the chairperson for ASPA’s Section on Environment and Natural Resources Administration (SENRA). He has been repeatedly recognized for his academic achievements and contributions, including awards for distinguished service and teaching

Fisk has consistently demonstrated a strong commitment to preparing the next generation of local government management professionals for success, a dedication that has remained steadfast throughout his career transitions and will surely continue into the future.

Director of Strategic and Government Affairs, Sugar Land, Texas

Shayla Lee’s visionary leadership, strategic approach, and unwavering commitment to public service have allowed her to rapidly ascend through the ranks and distinguish herself as an early career local government leader.

Lee began her career as a management analyst in the city of Sugar Land’s data and innovation department.

In this role, she was seen as an innovative problem solver, which led her to be quickly promoted to the role of assistant to the city manager, where she worked on citywide strategic initiatives. As a result of her success, she was tasked with leading the newly formed strategic and government affairs department.

strengthening collaboration, streamlining processes, and driving innovation across the organization.

Lee is a trailblazer in local government, demonstrating exceptional leadership, innovation, and strategic foresight.

In her current role, she is responsible for the development and implementation of the city’s most robust and comprehensive strategic action plan. She has taken the city to new levels of success in data-driven governance, strategic planning, and intergovernmental relations, which has helped position the city as a leader in these areas.

Lee is a proactive and results-driven leader, known for her ability to drive organizational change, cultivate talent, and implement innovative strategies. Three of these strategies include:

Strategic Decision Making. She possesses an exceptional ability to anticipate challenges and implement proactive solutions. In overseeing the merger of the data and innovation department with the strategic and government affairs department, she has played a key role in

Collaborative Leadership. Lee has built strong relationships with the city council, department heads, and external partners to advance Sugar Land’s priorities. She is highly regarded for her ability to bring people together and facilitate crossdepartmental collaboration to improve operational efficiency. She has enhanced the city’s relationship with the Fort Bend Independent School District by mentoring high school students and providing them with leadership opportunities and hands-on experience in local government.

Commitment to Professional Growth. As a champion for talent development, Lee has strengthened Sugar Land’s management analyst program, ensuring that emerging professionals receive mentorship, hands-on experience, and leadership opportunities to grow in local government.

demonstrating exceptional leadership, innovation, and strategic foresight. Through her work in strategic planning, employee empowerment and interdepartmental collaboration, she has transformed city operations, enhanced workplace culture, and positioned Sugar Land as a model for excellence in local governance.”

Established in memory of former ICMA Executive Director William H. Hansell Jr., this award recognizes an outstanding early career local government professional who has demonstrated leadership, competency, and commitment to local government as a profession.

Outside of her work in her department, Lee is committed to improving staff culture. She was a founding member of the City Care Club, which provides support to employees in times of hardship and celebrates employee milestones and successes. This group is built on the core principles of transparency, accountability, and fostering a culture of care. This initiative has contributed greatly to staff morale and reinforces the city’s commitment to employee well-being and community building.

Lee’s management style is based on three core principles: encouraging innovation, prioritizing mentorship and development, and building a culture of accountability and engagement. These values are present in all of her work and help her to succeed in her daily operations.

As her nominator noted, “Lee is a trailblazer in local government,

Bondurant, Iowa, USA

Marketa George Oliver, ICMA-CM, City Administrator

Bondurant seeks to create community spaces for people of all abilities to ensure that no resident faces barriers to accessing community life. Through investment in accessible facilities, the creation of inclusive programming, and the development of public-private partnerships, Bondurant has prioritized creating an accessible, welcoming community for all.

Ensuring the availability of free and accessible recreational opportunities was a top priority for Bondurant. As a result, the city invested nearly $2 million to install adaptive playground equipment including an assisted zip line with a secure harness, a wheelchair-accessible merry-go-round, an innovative swing that accommodates wheelchair-users, and sensory-friendly areas. The

second phase of the project will bring a splash pad and adaptable swing set that will expand the available community play options.

The carefully selected elements ensure that children with mobility or sensory challenges can play with their peers and that all families, regardless of ability, can access highquality, free recreational spaces in their own community.

Bondurant partnered with private developers and nonprofit organizations to develop a downtown that combines historic preservation with accessibility and innovation. This project follows a jointly developed master plan that included community input. The highlight of the redevelopment is the T12 Distillery, which is run by a community member who uses a wheelchair after enduring a spinal cord injury. The space is fully accessible and not only serves as a distillery but also as an educational and philanthropic hub that raises awareness of spinal cord injuries and supports related nonprofit organizations. Collaboration with community members, private developers, and nonprofit organizations ensures that the city meets the needs of all residents while also honoring Bondurant’s rich agricultural history.

In addition to the partnerships developed in the redevelopment project, Bondurant has taken their commitment to accessibility and inclusion a step farther by partnering with the nonprofit organization Can Play, which provides adaptive sports and recreation programming for individuals facing physical, cognitive, and financial barriers. To ensure the community is able to take full advantage of these offerings, Bondurant developed its first building dedicated exclusively to parks and recreation. The adaptive reuse project called The Station redevelops an old emergency services building into an inviting community space that can host programming and includes a variety of services such as a wellness room. The new building fills a critical gap in the city’s infrastructure and provides an opportunity for all residents to fully participate in recreational activities. Individuals of all abilities will be able to use this space to connect, feel valued, and thrive.

Bondurant’s commitment to community equity and inclusion shines through these recreational initiatives. The success of this project showcases the importance of the key pillars of collaboration, innovation, and intentionality. By ensuring community involvement and partnering with innovative developers and nonprofit organizations, Bondurant shows that equity and inclusion is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Careful planning, collaboration between city staff and community members, and creativity help design programs and spaces that serve everyone.

Melissa A. Valadez, ICMA-CM, City Manager

Chasidy Benson, Assistant City Manager

Alison Ream, Assistant City Manager

When building a new library, the city of Cedar Hill looked to create more than just a space for books. They sought a true community hub that provided a variety of resources for residents while also maintaining the values of accessibility, equity, and sustainability. To do this, they had to rethink traditional locations and building structures and spend significant time engaging all stakeholders.

This first-of-its-kind facility was developed through extensive public engagement, data-driven planning, and strategic investments. The investment came from a combination of public funds, private investments, and grant funding to allow the Traphene Hickman “Library in a Park” to realize its full potential as a cultural destination to stimulate economic development and civic engagement.

The library includes cutting-edge technology, a museum of city history, a professional podcast and music recording studio, nature trails, public art, and an outdoor performance area in the heart of the Signature Park. Sustainability was at the forefront in design considerations for the Library in a Park, garnering the city’s first LEED Silver certification for its incorporation of innovative energy saving features and context sensitive design. In keeping with the city’s sustainability values, trees removed from the construction site were repurposed to create custom furniture, interior wall panels, and decorative features throughout the building—ensuring that

nature remained an intentional part of the space. Its unique location allows for community access to expand beyond the building itself and for residents to enjoy activities beyond the traditional features of a library, incorporating both nature and play. As a result, the library has seen great success, including a 250% increase in membership within the first six months of operation, more than 40,000 attendees at events and programs, hundreds of entrepreneurs and small businesses engaging with the business center, and more than 30,000 visitors to the Signature Park since its opening.

The success of the library goes beyond the grounds. The new opportunities spurred by the catalytic nature of this project are expected to exceed over $155 million in private investments in the Midtown District where the facility is located. The Library in

a Park has become a powerful symbol of equity and innovation for the Cedar Hill community and other communities that look to the success of Cedar Hill as a model for their own projects. The commitment to equity and inclusion began from the project’s development. Overall, 48.6% of project expenditures were with minority- and women-owned businesses, far surpassing traditional diversity benchmarks, and the end result demonstrates how local governments can redefine public spaces to drive both social and economic progress.

In addition to being a great success for the city of Cedar Hill, the Traphene Hickman Library in a Park sets an example for other local governments looking to develop similar centers of community life. The intentional focus on inclusivity from the very beginning stages led to a community resource for all—a location truly beyond the traditional library—brought to life through the collective fingerprints of a community deeply invested in its future. Cedar Hill was very fortunate to have strong support from elected leadership and the community at large, both young and old. The community support led to intensive public engagement that led residents to feel invested in the process and allowed them to contribute to the overall design and development. The city also used this as an opportunity to showcase the project to the media and raise awareness about the role of local government in innovative urban planning. The Library in a Park is more than a library. It is a key feature of Cedar Hill’s community life that showcases the power of inclusive, forwardthinking, community-driven governance.

Austin, Texas, USA

T.C Broadnax Jr., ICMA-CM, City Manager

Jon E. Fortune, Deputy City Manager

David Gray, Director, Homeless Strategy Office

In December 2023, the city of Austin opened the Eighth Street Women’s Shelter to address a critical gap in the local homeless response system: the lack of gender-responsive shelter options. Data showed that 40% of Austin’s unhoused population identified as women or gender-diverse, yet existing shelters often failed to meet their distinct needs. Without access to safe and inclusive environments, many women and gender-diverse individuals were discouraged from seeking shelter or support.

To address this gap, the city of Austin purchased The Salvation Army’s former Downtown Center that was slated to close due to high operating costs. The city quickly redeveloped the building with the intention of providing safe, accessible, and effective services specifically designed to meet the needs of women, transgender, and nonbinary people experiencing homelessness. Guided by input from individuals with lived experience, local service providers, and other key stakeholders, many of the building’s former offices and administrative spaces were converted into bedrooms, community rooms, and service spaces to maximize the building’s capacity and ensure that more people could be safely supported.

Today, the Eighth Street Women’s Shelter provides safe, dignified accommodations for more than 160 individuals. The shelter offers a range of room types—including ADA-accessible units, two-person rooms, and larger congregate spaces—to meet varying needs. It also includes up to a dozen overnight safe sleep beds for individuals seeking short-term accommodations. In addition to delivering critical community services, the shelter stands as a strong example of how aging infrastructure can be creatively repurposed to respond quickly to urgent housing needs.

The city’s plan to open and operate the Eighth Street Women’s Shelter had four key elements:

Comprehensive Support Services: Shelter residents receive case management, mental health counseling, substance use treatment referrals, housing navigation, vital records support, job training and placement assistance, and many other services to help them exit the shelter quickly and positively.

Trauma-Informed Care: All staff are trained in traumainformed practices to ensure a safe, respectful, and dignified environment for all residents.

Accessibility and Inclusivity: The shelter is intentionally designed and operated to safely accommodate women, transgender, and non-binary individuals—addressing a long-standing gap in gender-inclusive shelter services.

Public and Private Partnerships: The city partners with service organizations, advocacy groups, local colleges, workforce development programs, healthcare providers, and others to support shelter operations and enhance service delivery.

These four elements are critical to the success of the Eighth Street Women’s Shelter, which is evidenced by the shelter’s impact. In its first year of operation, the shelter served roughly 500 women and gender-diverse individuals. Nearly 100 secured permanent housing through on-site services and support, while many others made progress toward stability—obtaining identification, connecting to health care, engaging in case management, or moving into other housing programs. The previously underserved population now has enhanced safety, security, and stability.

In addition to meeting a critical community need, the city learned valuable lessons in developing gender-responsive homeless services. Community engagement is crucial, flexible and low-barrier entry is essential, equity and inclusion principles must guide the program design, and continuous staff training matters. The city of Austin is using these lessons as guiding principles for future projects spanning the homeless response system—from new homeless prevention efforts to the designs of future permanent supportive housing communities. The Eighth Street Women’s Shelter highlights a commitment to equity-driven governance and responsive service delivery, which are key principles of any local government project.

Bondurant, Iowa, USA

Marketa George Oliver, ICMA-CM, City Administrator

Marketa George Oliver

As one of the fastest growing communities in Iowa, Bondurant is continually faced with ensuring the public receives necessary education and training on staying safe in the community and their everyday lives. As new residents continue to arrive, there is a growing need for a combined educational program taking into account health, safety, wellness, and community engagement. Bondurant Safety Connecting coordinates existing city efforts, as well as developing new ones, to ensure all community members have access to education and resources.

In order to address community needs, the city realized it needed a coordinated program to ease communications and interactions among different agencies. The multi-agency collaboration allows the city to meet the diverse needs of its growing population from multiple angles.

Safety Village: One of the main programs under the Bondurant Safety Connecting initiative is Safety Village. This takes place annually and allows community members to interact with local law enforcement and emergency services. The engagement helps community members to feel more comfortable and confident about interacting with law enforcement and emergency services, while also providing important education around fire safety, rules of the road, and bike safety. The event is designed to encourage families to participate and provides tangible resources in addition to educational opportunities.

Certified Crisis Response Canine: This important team member was added to the Bondurant emergency services team to provide emotional support to first responders and engage with the community by making school visits, attending community events, and being directly involved in crisis situations.

Youth Safety: Through workshops such as Babysitting Basics and Home Alone Awareness, young adults are equipped with the skills they need to stay safe in their homes.

B Safe Bondurant Public Service Information Program: While all of these programs are critical to safety, B Safe Bondurant provides education from another angle, focusing on three key information initiatives: safety in parks and on trails, safety while traveling, and safety at home. These initiatives include topics such as outdoor emergency preparedness, traveling safely, and gun safety and home security.

Lastly, the Bondurant Safety Connecting program makes sure that community members of all ages stay safe online and children learn personal safety skills through community-based programs hosted at the local library.

Bondurant is able to provide a wide range of services at little to no cost due to effective community partnerships. Each of the previously mentioned programs has a community sponsor, which reduces costs for the city and the community members. From other agencies such as the Polk County Sheriff’s Office, the Polk County Health Department, and the Emergency Services Department to local hospitals and universities to business partners and nonprofit organizations, each program is run with a partner organization. This ensures that the programs are run by subject matter experts, and it expands the reach of local government services through utilization of partner organizations’ networks.

The coordinated program demonstrates the central role of local government in improving community health and safety and ensuring residents are educated not only about city services, but also about keeping themselves and their families safe. Local government managers facilitated the numerous community organization partnerships and played a pivotal role in ensuring processes were streamlined so that bureaucracy did not bottleneck engagement.

The city government provided opportunities for residents to engage directly with local government personnel to foster trust and build relationships. The outreach helps community members see their local government as responsive, approachable, and invested in community well-being. Bondurant Safety Connecting created a cohesive approach to public health, wellness, and safety that has had an immediate impact on residents while also ensuring health and safety education is woven into the fabric of the community for years to come.

Elk Grove Village, Illinois, USA

Matthew Roan, Village Manager

David Dorn, Chief of Police

Telia DeSarno, Social Services Supervisor, Police Department

Reframing illegal drug use from a problem for law enforcement to a public health crisis that needs treatment and support led Elk Grove Village to develop the Elk Grove Village Cares program, the first community-based program of its kind in the Chicago area. This program serves anyone over the age of 12, regardless of residency, and not only includes access to treatment and support services, but also financial support for those who are uninsured or underinsured. Elk Grove Village Cares goes beyond the boundaries of the village to provide help when people need it and combat a crisis that reaches far beyond village limits.

The program, run by the police department, directs individuals with addiction to community services that can better assist them and meet long-term needs. This not only provides better services for those in need but also directs them away from jails and courtrooms, freeing up space for serious crimes. It builds trust between the police and the community as they are seen as partners and not just law enforcement. The police-assisted deflection program addresses the root cause of the criminal behavior—substance abuse—which leads to better outcomes for individuals, families, and the community as a whole.

Funded nearly completely by state and federal grants, the Elk Grove Village Cares program also removes financial obstacles to treatment. The program is available to anyone who contacts the police department to ask for help, regardless of ability to pay, and those asking for help will not face arrest. The village partners with community-based care centers and foundations to connect those seeking treatment with proper care and support. All police officers are trained on the program, and no one is turned away.

The partner organizations offer a wide variety of services, including inpatient and outpatient care, transitional housing,

medication-assisted treatment, counseling, detoxification, case management, behavioral health screenings, and diagnostic evaluations. In addition to the treatment options, the program also covers transportation to and from the treatment centers to ensure barrier-free access to recovery. This holistic approach provides measurable progress toward fighting the public health crisis.

While many programs exist for adults, Elk Grove Village Cares also includes adolescents, which helps to treat addiction before adulthood, keeps kids in school, and reduces the likelihood of criminal behavior. As a final part of this program, the village installed a free Narcan dispensing machine and prescription drug collection box to fight overdoses and encourage proper disposal of unneeded medications.

In the first five and a half years of the program, Elk Grove Village Cares has made 383 connections to treatment providers. The Narcan dispenser was added in June 2023, and the free kits led to 17 overdose reversals in the first 18 months of their use.

The community-based initiative brought together numerous stakeholders, and the police department has been able to build and maintain these strong relationships to keep the program in operation. Acting quickly when someone needs help is key to success, and having trusted, reliable treatment partners allows this to happen easily. The program’s success has been recognized by multiple state and federal agencies and showcases the importance of local government managers in community health and safety. Ultimately, the availability of these resources leads to a safer, healthier community for all.

William Bowman Ferguson, ICMA-CM, City Manager

Wanda S. Page, Retired City Manager