SONG SUNG BLUE

BIDDING ADIEU

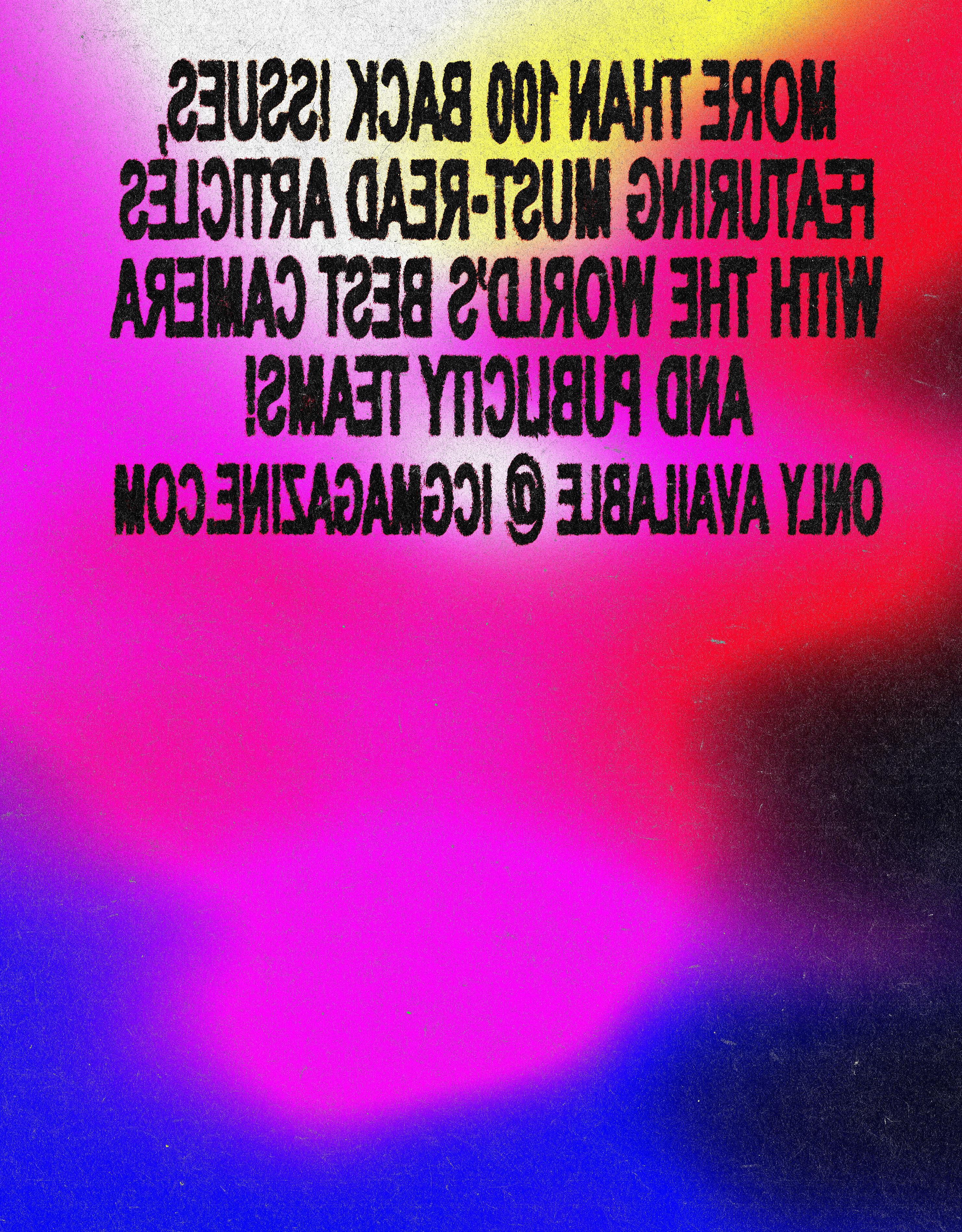

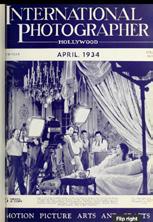

There was a lot going on in March of 1929. Herbert Hoover was sworn in as the thirty-first president, and the San Francisco Bay Bridge opened. By then, 70 percent of films had become “talkies,” a shift that would see “silents” gone for good in a few short years. March 1929 also brought the birth of this magazine, then called The International Photographer Today, you hold its final issue – whether on paper or electronically. For almost 100 years, these pages showcased the work of our union members, as well as the artists and artisans who created and promoted the visual storytelling seen by millions – in theaters, living rooms and more recently, on screens everywhere in the world.

All change carries some loss, but it also opens the door to new growth. In this case, it creates exciting opportunities for how we communicate with our members and with our industry. We all see an ever-increasing demand for image-driven stories that will be told in contemporary ways for fresh audiences. The International Cinematographers Guild will continue to spotlight our colleagues in fresh and powerful formats, marking a new beginning as this publication writes its final chapter. Everything this magazine has highlighted will continue to be celebrated by the union, and all past issues will remain available in our archive for those drawn to explore the history of our members and our crafts.

I thank all the hundreds of people who have contributed to this publication over so many decades, and I thank you, the readers, who made the work feel meaningful and fulfilling. The International Cinematographers Guild is not going away. We look forward to meeting you again, in other ways and in new places.

John Lindley, ASC

National President International Cinematographers Guild IATSE Local 600

photo by Robb Rosenfeld

Publisher Teresa Muñoz

Executive Editor

David Geffner

Art Director

Wes Driver

NATIONAL DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Jill Wilk

COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

Tyler Bourdeau

COPY EDITORS

Peter Bonilla

Maureen Kingsley

CONTRIBUTORS

David James, SMPSP

Jay Kidd

Margot Lester

Kevin Martin

Valentina Valentini

IATSE Local 600

NATIONAL PRESIDENT

John Lindley, ASC VICE PRESIDENT

Jamie Silverstein

1ST NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Deborah Lipman

2ND NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Mark Weingartner, ASC

NATIONAL SECRETARY-TREASURER

Stephen Wong

NATIONAL ASSISTANT SECRETARY-TREASURER

Selene Preston

NATIONAL SERGEANT-AT-ARMS

Betsy Peoples

Tobin Yelland December 2025

NATIONAL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Alex Tonisson

COMMUNICATIONS & OUTREACH COMMITTEE

Jamie Silverstein, Chair

CIRCULATION OFFICE

7755 Sunset Boulevard

Hollywood, CA 90046

Tel: (323) 876-0160

Fax: (323) 878-1180

Email: circulation@icgmagazine.com

ADVERTISING REPRESENTATIVES

WEST COAST & CANADA

Rombeau, Inc.

Sharon Rombeau

Tel: (818) 762 – 6020

Fax: (818) 760 – 0860

Email: sharonrombeau@gmail.com

EAST COAST, EUROPE, & ASIA

Alan Braden, Inc.

Alan Braden

Tel: (818) 850-9398

Email: alanbradenmedia@gmail.com

Instagram/Facebook: @theicgmag

ADVERTISING POLICY: Readers should not assume that any products or services advertised in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine are endorsed by the International Cinematographers Guild. Although the Editorial staff adheres to standard industry practices in requiring advertisers to be “truthful and forthright,” there has been no extensive screening process by either International Cinematographers Guild Magazine or the International Cinematographers Guild.

EDITORIAL POLICY: The International Cinematographers Guild neither implicitly nor explicitly endorses opinions or political statements expressed in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. ICG Magazine considers unsolicited material via email only, provided all submissions are within current Contributor Guideline standards. All published material is subject to editing for length, style and content, with inclusion at the discretion of the Executive Editor and Art Director. Local 600, International Cinematographers Guild, retains all ancillary and expressed rights of content and photos published in ICG Magazine and icgmagazine.com, subject to any negotiated prior arrangement. ICG Magazine regrets that it cannot publish letters to the editor.

ICG (ISSN 1527-6007)

Ten issues published annually by The International Cinematographers Guild 7755 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, CA, 90046, U.S.A. Periodical postage paid at Los Angeles, California POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: ICG Magazine 7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, California 90046

Copyright 2025, by Local 600, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States and Canada. Entered as Periodical matter, September 30, 1930, at the Post Office at Los Angeles, California, under the act of March 3, 1879. Subscriptions: $88.00 of each International Cinematographers Guild member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. Non-members may purchase an annual subscription for $48.00 (U.S.), $82.00 (Foreign and Canada) surface mail and $117.00 air mail per year. Single Copy: $4.95

The International Cinematographers Guild Magazine has been published monthly since 1929. International Cinematographers Guild Magazine is a registered trademark. www.icgmagazine.com www.icg600.com

“CINEMATOGRAPHER TAKURO ISHIZAKA MAKES WONDERFUL USE OF TOKYO, frequently employing shots depicting its vast urban landscape to underscore the loneliness of Phillip and many of its inhabitants.”

“HIKARI crafts a VISUALLY RICH NARRATIVE.”

“Rental Family is PURE MOVIE MAGIC.”

WIDE ANGLE

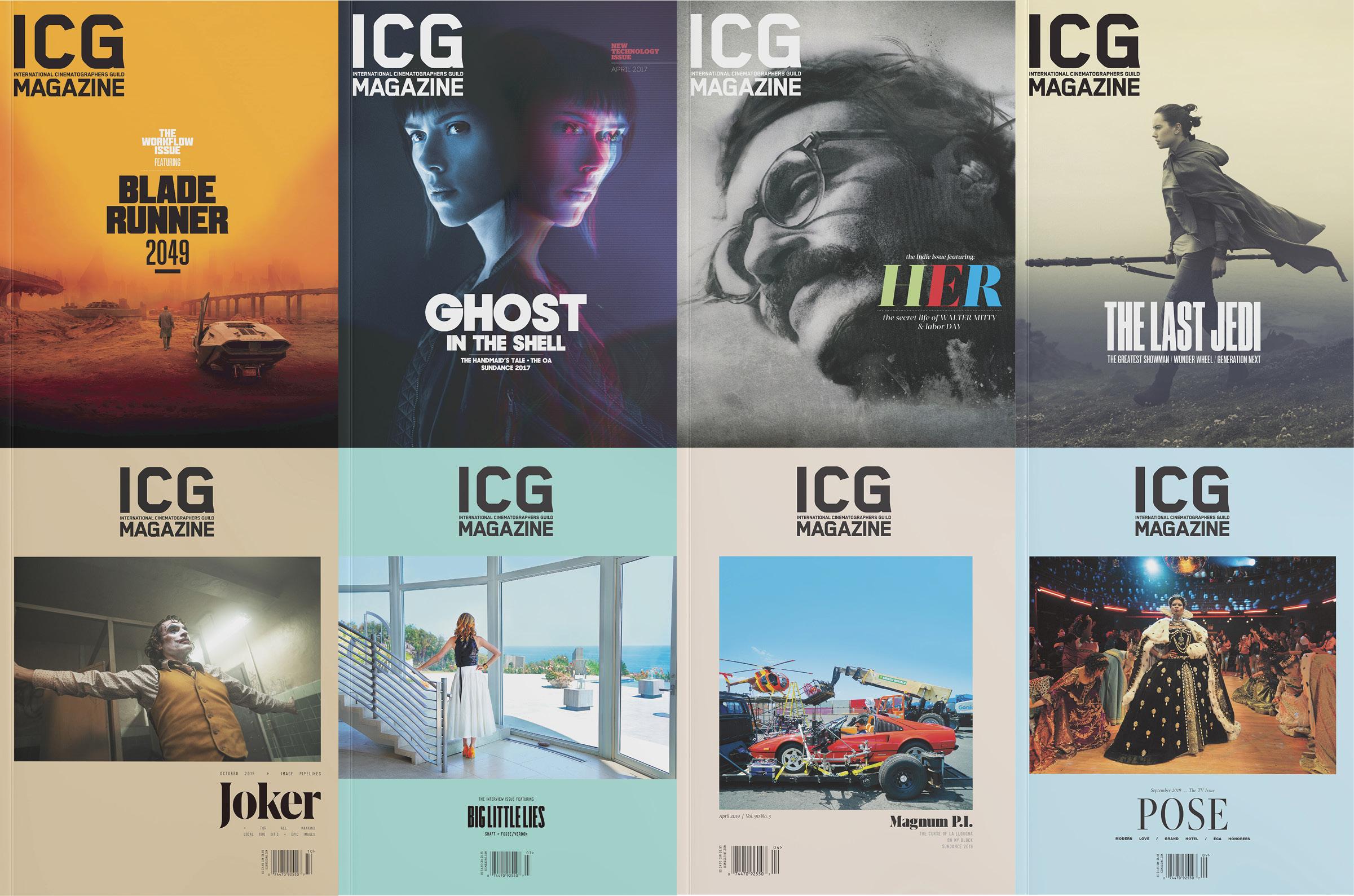

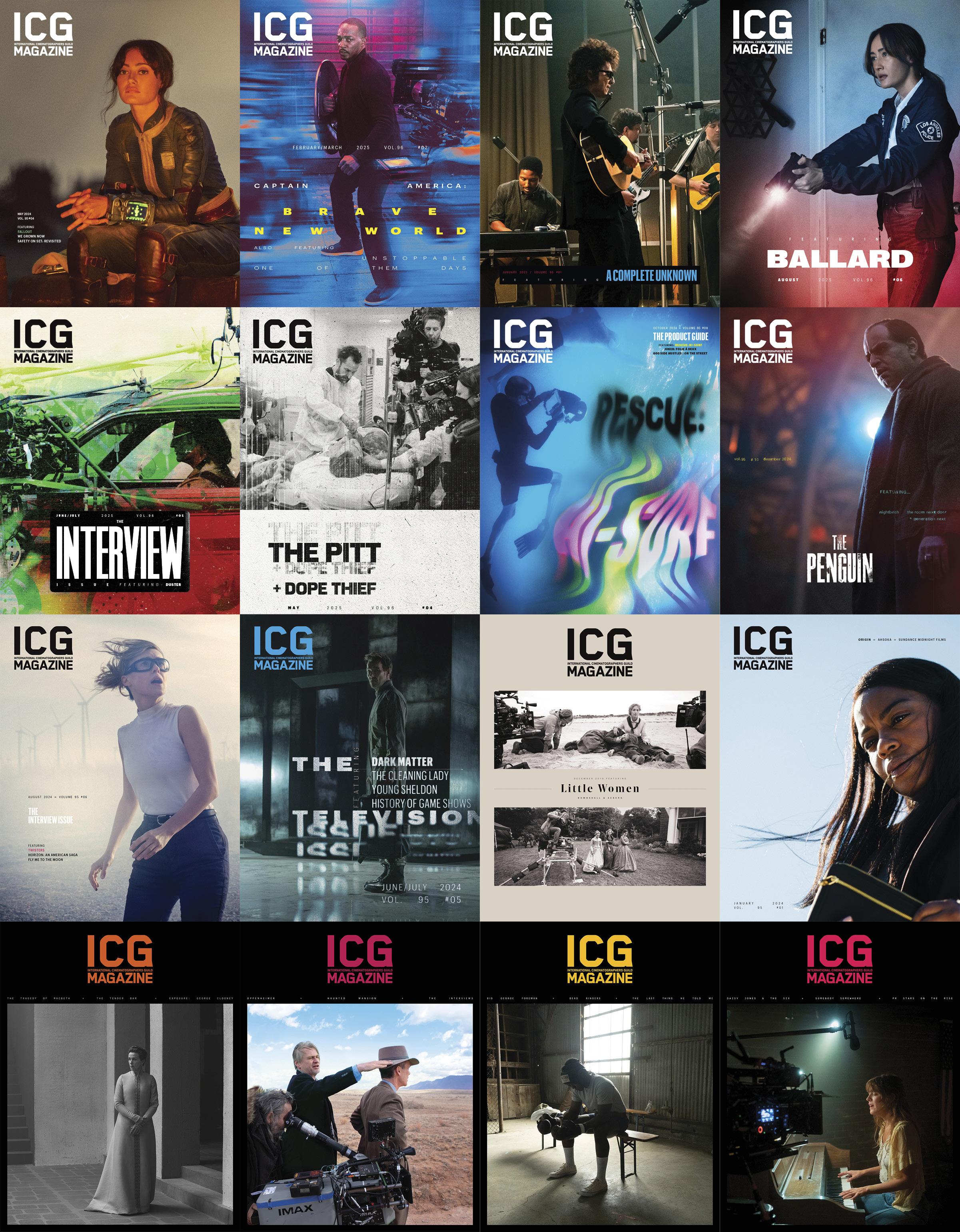

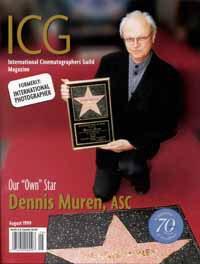

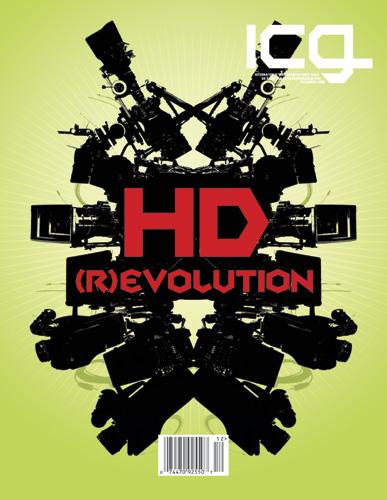

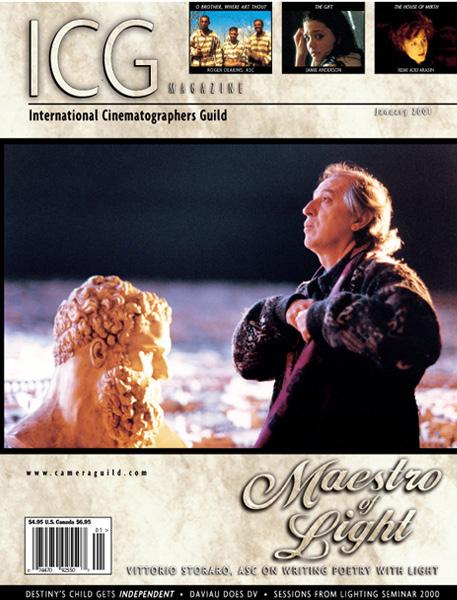

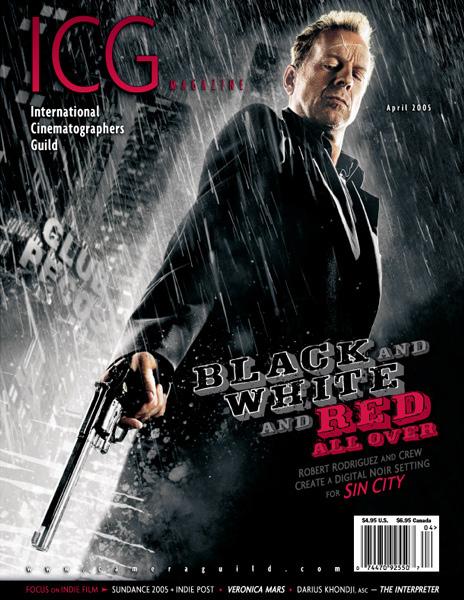

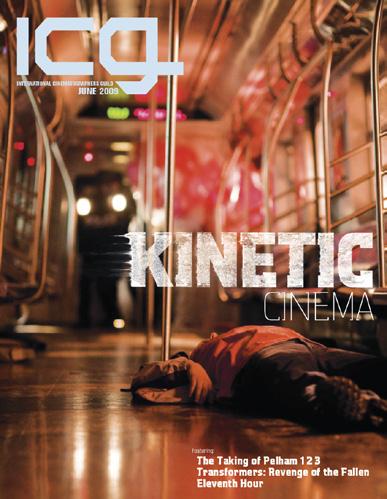

When we got the news that ICG leadership was going to “sunset” the magazine, meaning this December 2025 issue would be the last in its 96-year history (see page 34 for a detailed historical timeline of the magazine since its inception in 1929), my first mental image (probably because it’s awards season!) was of the many ICG directors of photography I’ve gotten to know who, upon winning a – pick one: Oscar, Emmy or ASC award – frantically try to name all the people they want to thank before the music plays them off. Although my tenure as executive editor was long by contemporary standards – seventeen-anda-half years – the list of individuals who helped this magazine win dozens of Maggie (Publishing) Awards, and, more importantly, helped connect, promote and support (literally) thousands of union film and television workers, began well before I arrived.

Within recent memory, that list starts with ICG President Emeritus George Spiro Dibie, ASC (working with then-Editor Suzanne Lezotte), who transitioned the magazine from galleys to computers in the mid-1990s, on through to the arrival of former ICG President Steven Poster, ASC in the mid-2000s, whose creative support (first with my predecessor, Neil Matsumoto, and then with me and current art director, Wes Driver) helped make ICG Magazine the world’s premier filmmaking journal. Past art directors Joy Orlino, Edgar Orlino, Matthew Ward, and especially Stefan Viterstedt (who immediately preceded Driver) all elevated the magazine to new visual heights, while our longtime ad sales team, Sharon Rombeau and Alan Braden, worked hard to make each issue a revenue driver for Local 600.

Pauline Rogers was not just the only staff writer this magazine had in the modern era, she was (at the time of her passing in 2024) the longestrunning employee of the union’s national team. (You can read about Pauline’s brilliant career in the Web Exclusive I wrote early this year.) Longtime freelance writers under my (and Neil’s) tenure, including Kevin Martin, Ted Elrick, Margot Lester, Matt Hurwitz, Elle Schneider and Valentina Valentini, along with copy editors Peter Bonilla and Maureen Kingsley, all made me a much better editor, while current ICG Assistant Western Region Director Michael Chambliss ensured all those visits to snowy Utah (and windy Palm Desert) were that much more fun and productive. And, of course, there are the many, many publicists who lined up interviews on Sundays and holidays, and pitched me so many of our awarding-winning stories.

Teresa Munoz, who joined Local 600 in 1995 (and was associate publisher for nearly a decade before assuming the role of publisher in 2009), is the

lone historical link to our pre-digital days. Her calm, thoughtful leadership is what made the 200-plus issues this team did together (without failing to deliver an issue!) unparalleled in any of our working lives. Thanks also go to the Communications Department, led by National Director of Communications Jill Wilk (who advocated our work to leadership), Communications Assistant Joey Gallagher (who banked yeoman hours editing video for the magazine), and, especially, Communications Manager Tyler Bourdeau, who showed dogged persistence tracking down imagery, lining up photo portraits, and chasing video interviews (from Park City to Universal City), and was a blessed addition to our small staff. As for Wes Driver’s stunning, textured layouts, I have no doubt they belong as much in a high-end art gallery as they do on the latest iteration of WordPress; Wes’ artistry never failed to impress and surprise.

Numerical highlights of this group’s tenure include 19 (layout/design) Maggie Awards; 16 trips to the Sundance Film Festival to host ICG Magazine’s Snowdance party; 11 Deep Dive (the series created at the onset of COVID) virtual and in-person panels; 14 issues devoted entirely to ICG’s publicist and unscripted members; 15 Interview Issues, which gave voice not only to every single job classification in Local 600 but to their many filmmaking partners; 17 Product Guides, the result of our staff’s annual trips to NAB, Cine Gear and HPA to visit with our many vendor partners; and, just this year, three episodes of our first-ever podcast, Outside the Frame

It’s impossible to thank all the many union members who made time for Zoom, phone and email interviews over these many years, so I’ll just mention a few whose love for the magazine knew no bounds. They include Nancy Schreiber, ASC; Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC; Checco Varese, ASC; Matty Libatique, ASC; Alice Brooks, ASC; Todd Banhazl, ASC; Rachel Morrison, ASC; Reed Morano, ASC; Oliver Bokelberg, ASC; Claudio Miranda, ASC; Phedon Papamichael, ASC; Todd A. Dos Reis, ASC; Adam Biggs; James Bagdonas; Robert Elswit, ASC; John Schwartzman, ASC; and the amazing Shana Hagan, ASC. If you think that list (which is only DP’s!) is awesome, then check out our Quote Tribute (page 36), where many more share parting thoughts about how the magazine imprinted their careers, on and off the set.

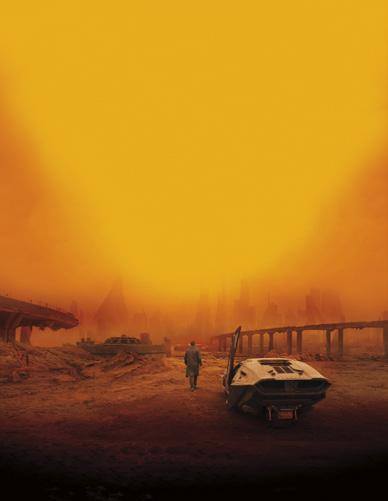

Finally, it can only be described as heaven-sent symmetry that the last issue of ICG Magazine is themed around Generation NEXT, which highlights those union filmmakers leading the charge into the great beyond. Song Sung Blue, this month’s cover story, was shot by Amy Vincent, ASC, whom I first met at Sundance twenty years ago when she was a Generation NEXT filmmaker and who continues to define what it means to belong to this very special community of technicians and artists.

So (before the music plays me off), a huge thank you from the ICG Magazine staff to all who shared in this magical ride. We couldn’t have done it without you!

David Geffner Executive Editor Email: david@icgmagazine.com

Cover Photo by Sarah Shatz

Photo by Sara Terry

VALENTINA VALENTINI

TOBIN YELLAND

COMPILED

BY

MARGOT LESTER

ZR CINEMA CAMERA

$2,195 NIKONSUSA.COM

This new lightweight, compact camera boasts an internal 6K REDCODE RAW recording capability, using the CFexpress media as on the V-Raptor [X] and KOMODO-X cameras. “This makes the footage integrate seamlessly into established workflows,” describes Director of Photography Markus Förderer, ASC, BVK. “The ZR allows me to capture raw video with RED’s excellent color science, with the ability to use the same LUT’s I use in the bigger cameras but in a very small camera that can be rigged pretty much anywhere. I can bring it on location scouts and experiment to develop a unique look and feel during pre-production.” That makes it a good choice for setups that are too dangerous or complicated to mount a traditional camera. “This camera allows you to go out on your own to remote places and capture images that will hold up on an IMAX screen when exposed properly.”

Sean Bobbitt, BSC

“A proliferation of arresting moments— CAUGHT ON THE WING IN WIDE-SCREEN IMAGES, THANKS TO SEAN BOBBITT’S CINEMATOGRAPHY—that balance tragedy and horror with excitement and wonder”

This new lens set features a “huge image circle of 65 millimeters ready for the current and upcoming slate of larger-format cameras, unlocking new lens characteristics and flares that are hidden on smaller sensors,” notes Lensworks’ Chief Engineer Stephen Gelb. “The lenses are awesome for any format, but they really come alive on the new larger imagers.” The set distills many lenses, landing on optics chosen for both the huge 65-mm image circle and a character-rich image. It delivers a consistent, fast, workable T-stop and open-gate coverage for the ARRI ALEXA 65 and Blackmagic Design 17K sensors. Other highlights include excellent close focus, micro contrast for smooth skin tones, and lens flares across a variety of focal lengths, making it perfect for narrative storytelling or commercial work. Housed in aircraft-grade aluminum with an expanded focus scale and spring-loaded cam-driven movement that eliminates backlash and image shift, these lenses excel in the most demanding production environments.

BEST PICTURE

CINEMATOGRAPHY Robbie Ryan , BSC, ISC

“ THE BEST PICTURE OF THE YEAR .”

“BUGONIA looks spectacular thanks to the sheer

’s

images.” e

Reporter

LEITZ HEKTOR LENSES FOR MIRRORLESS CAMERAS

$42,000 FOR THE SET OF 6 LEITZ-CINE.COM

Four years in development, the hand-built Leitz HEKTOR lenses provide classic photo beauty and cine glass without their limitations. The field curvature and spherical aberration gently soften focus and give bokeh a little more personality without sacrificing the relatively high contrast. Dynamic, colorful flares can be produced at certain focal lengths with less veiling glare than older optics. The lenses have an unusually durable construction for mirrorless-format lenses, making them a versatile option. Director of Photography Bret Curry recently used the lenses on a commercial shoot in Montana. “Chasing not only the light, but also some truly wild cowboys and horses, we needed a no-compromise lightweight prime set to hop between our smaller camera builds like the Freefly Ember S5K and the DJI Ronin 4D,” Curry recalls. “The Hektors provided a beautiful mix of vintage and modern characteristics, and their truly unmatched quality-to-size will certainly make them a staple in my lens packages going forward.”

FUJIFILM

GFX ETERNA 55

$16,499

FUJIFILM-X.COM

The GFX ETERNA 55 is the company’s first purpose-built digital camera for filmmaking production. Its variety of sensor modes includes a GF 4:3 Open Gate, the tallest commercially available and one of the widest (about 8.5 mm taller and 7 mm wider than Full Frame). Users can also fine-tune their images with the F-Log2 C logarithmic gamma curve that provides 14+ stops of dynamic range. “GFX ETERNA 55 users can make use of Fujifilm’s newly developed 3D Film Simulation LUT’s, made for use with F-Log2 C and inspired by some of our most popular analog film stocks,” says John Blackwood, product marketing director for FUJIFILM North America Corporation. “Paired with the new lightweight FUJINON GF3290-mm T3.5 Power Zoom lens, filmmakers are afforded a great range of options for crafting their stories. Featuring GF lens communication protocol, users will have full focus, iris, and zoom control through the use of controllable dials featured on the camera body and optional handle.”

MALCOLM SERRETTE

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

BY MARGOT LESTER

“I came up in a pro-union, working household,” explains Local 600 Director of Photography Malcolm Serrette, a 13-year ICG member. “My father, Dennis Serrette, started organizing labor unions in the 1960s, and that spirit he worked toward – of healthy working conditions and familial-like camaraderie – has carried with me into how I like to crew up.”

That love for labor also ingrained in Serrette a deep understanding of the value of his union, ICG. “I believe that in such a collaborative medium, having an optimistic, passionate, and talented team that feels appreciated for their

knowledge and skillset yields the best results for everyone,” he adds.

That people-first philosophy was also informed by Serrette’s early experiences growing up in Washington, D.C. Serrette says he knew in high school that he’d pursue a career in some aspect of the entertainment industry. So, he took summer courses at American University, which also included acting. When he got to NYU for film school, he was drawn to the camera department. Between classes, he worked as a production assistant and AC on productions shooting in the city, including a

lot of documentaries and unscripted shows, like MTV’s The City

“I learned so much watching documentary DP’s do a lot with a little, covering scenes single-cam and setting up interviews,” Serrette remembers. “That was great paired with more traditional scripted lighting classes. With that base, and over time, I learned how to be flexible in any environment and to know when and how to shift gears based on available crew and equipment.”

By age 26, Serrette had landed his first sixepisode, multi-cam gig with Producer/Director

PHOTOS COURTESY OF RICKY PONCE

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION BEST PICTURE

BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY DAN LAUSTSEN, ASC, DFF

“Dan Laustsen’s awe-inspiring cinematography is to die for. This is why I go to the movies.” FIRSTSHOWING

“Achingly gorgeous. Dan Laustsen’s cinematography will take your breath away.” NME

A film by Guillermo del Toro

Rasheed Daniels, also for MTV. “The thing is, I didn’t naturally have an eye,” he admits. “It took experience and years of studying for me to develop an in-depth understanding of what makes a shot what it is and why. I continued to work with directors over the years that were passionate about unscripted shows with highly stylized elements in multi-cam environments.”

The effort paid off, says Director of Photography Jeremiah Smith, who first met Serrette on Project Greenlight: A New Generation. “Malcolm has an amazing eye, masterful lighting skills, and a work ethic that makes any set that he is on pleasant,” Smith explains. “He’s super easy to work with and is collaborative, yet very certain in knowing what he wants. I personally like to have a good time on set, and working with him, you’re guaranteed to.”

These days, Serrette is a student of the “psychology of cinematography,” or, as he describes, “how we experience it and how different people approach it. I’ve found that my love isn’t just with playing with cameras, lenses, and light, but also in the act of impacting lives in whatever large or small way the profession allows, preferably in ways that are thought provoking and/or empowering.”

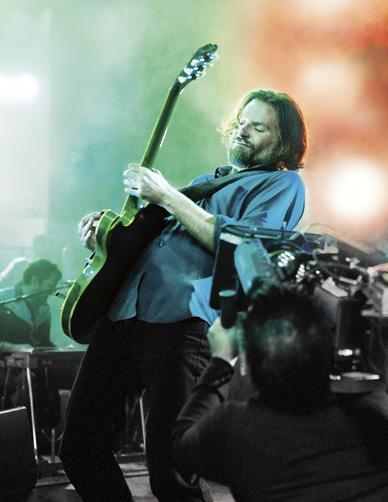

His most recent project was the marketing competition On Brand with Jimmy Fallon . Other credits run the unscripted gamut, from documentaries ( The Year of the Scab ) to live productions ( Lizzo: Live in Concert ), reality series ( Breaking Point , Long Island Medium ), cooking challenges ( Baking It , Gordon Ramsay’s Food Stars ), and music competitions ( American Idol , Rhythm + Flow ).

“One of the elements of shooting unscripted that gets less attention than geeking out at the 20-plus camera checkouts, big cameras on gimbals following cars, or Technocranes swinging around kitchens is the logistical Rubik’s Cube of how we’re going to dress and light new locations in unthinkable timeframes so that we can then play with those toys,” the L.A.-based Serrette notes.

A prime example was Rhythm + Flow, with Eminem, for which Serrette and crew scouted several locations in the rapper’s hometown of Detroit, including the Michigan Theatre. “The space is incredible, and I was salivating at the possibilities of lighting it up for rap battles, with epic Steadicam entrances up ramps and all the angles,” Serrette recounts, “not to mention tipping the hat towards a location used in 8 Mile.” But after weeks of discussion, the location was a budgetary no-go, and they moved to St. Andrews, the inspiration for the basement in 8 Mile and the place where Eminem (then Marshall Mathers) got his start freestyling. One problem: the space required a lot of lighting – and most of the crew (including Serrette) and all the camera packages were needed back in the Atlanta studio to finish filming a recording session.

“Our lighting director, Dave Thibodeau, is fantastic, and he split with our gaffer, Chris Roseli, to get a jump on load-in, while our tech producer, Mike Nichols, managed to source alternate camera gear to send from New York,” Serrette recalls. “Camera operators and AC’s would be pushing into sixth and seventh days, so production didn’t want to send all of

our team, either, so we needed to send a lot of new crew, with the exception of HOD’s. That alone is a challenge, as a lot of efficiency is built into the flow that gets established once a show is up and running.”

Upon landing in the Motor City, Serrette, showrunner David Friedman, and Director Jan Genesis had a small window to get the cameras up, make adjustments, set Eminem’s master interview, and light a bar next door for contestants.

“When camera images went up at MCR, we decided the stage just didn’t look good enough, as it lacked depth,” Serrette continues. So, they quickly pivoted to stage the rap battles on the floor in the middle of the audience. “Thanks to some good scouts, I had asked the production design team to hang some fluorescent fixtures for Titan Tubes to live in and be great foreground elements for the Technocrane,” Serrette says. “In this new spot, they provided a beautiful base layer of cyan in the shadows, and we redirected a few lights away from the stage to shape the rappers where they’d circle each other in battles.

“I’m not going to pretend all the location switches and lack of time made it more fun,” he adds. “But they’re the type of real-world challenges we always face in unscripted, and it highlights how important it is to have an amazingly talented crew with a can-do attitude. On screen, folks watching might just pay notice to the silhouette Ronin shot of Eminem walking down the stairs when he enters or the color palette we leaned into. But behind the scenes, a lot of the magic and work is in executing under pressure – and I believe we did.”

Smith isn’t surprised Serrette and his crew pulled it off.

“Malcolm’s a beast and will do his best to deliver the best product to the best of his ability,” he asserts. “He carries himself like a true professional and makes sure his team is taken care of.”

Says Serrette: “We’re humans first and workers by passion and trade. Connection and balance are everything. Our jobs don’t have to be the main source of our happiness, but ideally, they aren’t the source of our sadness. The protections that come with union membership make everyone better and happier on and off set. The guidelines allow companies to square capitalistic tendencies with human values, and everyone wins as a result.”

ADOLPHO VELOSO, ABC AIP

“THE MOST BEAUTIFULLY SHOT FILM OF THE YEAR.”

“ADOLPHO VELOSO’S CINEMATOGRAPHY IS RAPTUROUS.”

“THE BEST FILM OF THE YEAR.”

JOEL EDGERTON

FELICITY JONES

KERRY CONDON WILLIAM H. MACY

CRAIG BREWER

WRITER/DIRECTOR

BY VALENTINA VALENTINI

Twenty-five years ago, Craig Brewer wrote, directed and shot The Poor & Hungry for $20,000. He skipped the festival circuit and cut a deal with a local Memphis, TN theater chain to recoup what it cost to make. Five years later, he lived the indie dream when his film Hustle & Flow took Sundance by storm. That beloved musical drama rocketed Brewer’s stock in Hollywood and beyond, offering him the opportunity to direct studio features, sequels, remakes and more gritty indies.

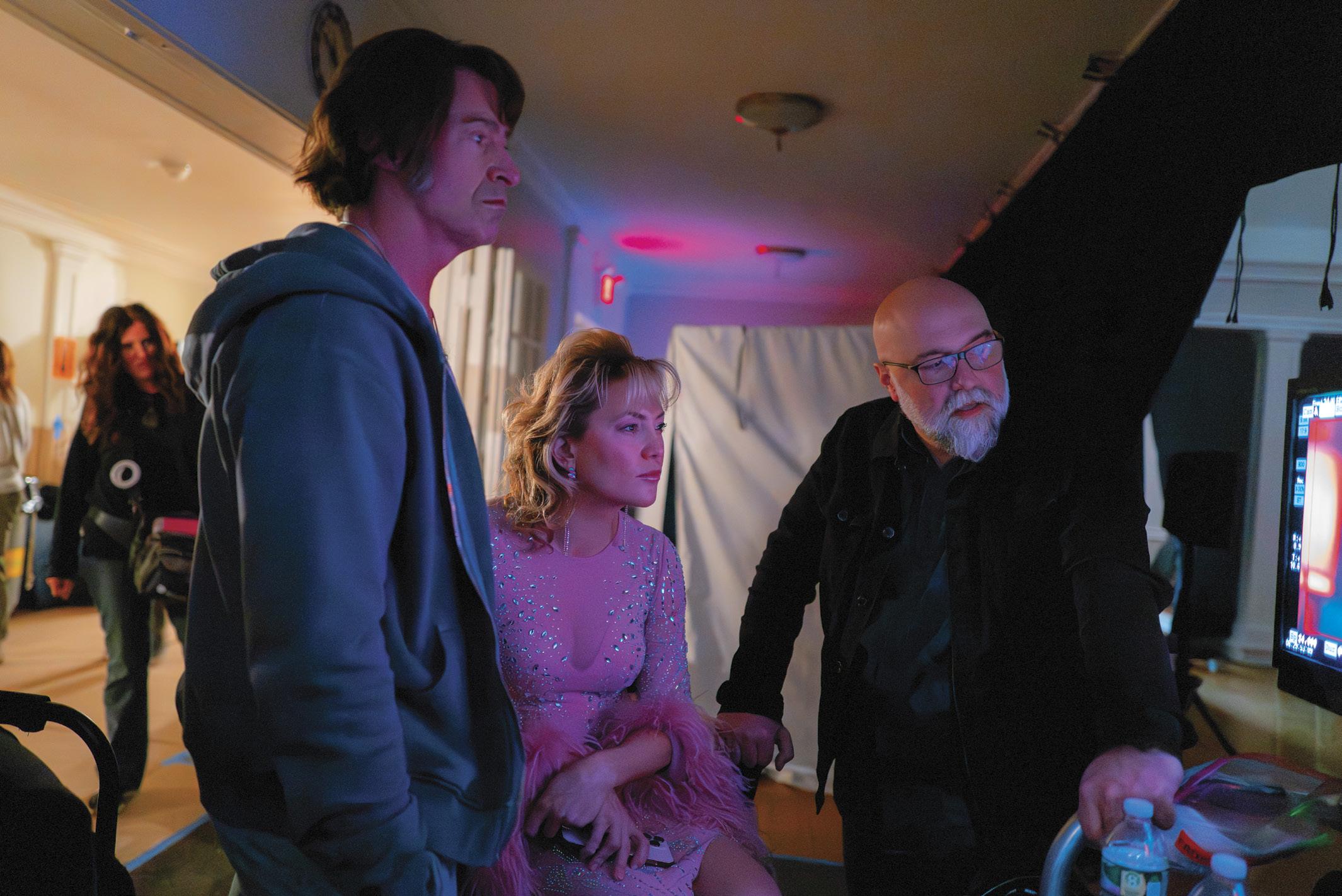

PHOTOS BY SARAH SHATZ FRAMEGRABS COURTESY OF FOCUS FEATURES

Despite the bespoke indie credentials, Brewer actually comes from a sports family. “My granddaddy was a New York Yankee and a New York Met,” the Memphis native says. “My dad went to the University of Tennessee, so in all of my baby pictures I’m wearing tacky orange. I think there was always the assumption that I was going to go into sports. But I was never good at sports, and that embarrassed me. I was drawn to movies.”

Brewer started acting as a young teen in the mid-1980s. His “film school” was browsing the local video store, where Dad would pick The Bridge on the River Kwai, sister would choose The Care Bears Movie, and he’d take Raiders of the Lost Ark. (Inevitably, Brewer would watch all three.) When he learned that Michael Jackson’s Thriller was done by a filmmaker named John Landis, who’d also done American Werewolf in London and The Blues Brothers, the doors to these cinematic worlds opened for Brewer (and it was how he and his father would bond).

By the time he was 14, he knew that all he wanted to do in life was make movies.

His latest, Song Sung Blue (yet another musically centered story) from Focus Features, shot by his longtime creative partner, Amy Vincent, ASC, is a feel-good, fight-for-yourdream story about a husband and wife who form a Neil Diamond tribute band. Emotionally, Brewer says, it meets him where he is in his life: divorced, parenting adult children and still fulfilling his dream of making movies.

ICG: Do you have a process that you always follow as a director? Actually, and on this movie in particular, I wanted to try to embrace a different methodology. I wanted to get in there on the rehearsals, make sure the actors felt comfortable and inspired, and then gather the crew around. I’d have my little boombox, with my musical cues, and I’d hit play and act out the whole sequence. What happened was that I got to see everyone from the stars to

the P.A.’s see it and get it. They’re seeing what I’m seeing in my head and what I’m going to put together later. And – sorry for the sports analogy here – it’s like we’re at the 10-yard line and ready to go.

So why a different methodology of directing now? I’m a parent of young adults, and I’ve realized that a lot of the stress and specificity that you put on what you think is what is right ultimately does not equal success. You can allow a lot more; you can let go. When I was a young man, I thought that that meant you were not doing your job. It’s much more of a tenet of confidence to allow and trust collaborators around you. My way of directing on this film was a lot looser. Hugh always said, “You’re jazz.” And that’s funny because most of my life has been anti-jazz! Only recently am I realizing that filmmaking is jazz – have a great drummer and a bunch of talented people doing their own riffs, and allow it to flow. That might make for a really good movie. continued on page 30

Black Snake Moan , Coming 2 America , Footloose, Song Sung Blue – these are all very different films. What attracts you to a story? I have to find an emotional connection. When I was making Black Snake Moan, I was suffering tremendous anxiety attacks and was fearful about so much in my life. I had lost my father unexpectedly from a heart attack. He was 49 years old. It made me wonder whether mortality was more urgent. And I found that the best way that I could handle that anxiety was to connect with people who also felt that same thing, and somehow be tethered to each other and get through it together. With Footloose, I know it’s the studio coming to me and saying they’re going to do a remake – with or without me. But I wanted to make it because I was a parent at that point, holding onto my son and daughter to keep them away from this scary world. With Song Sung Blue, I’m divorced and wondering if there’s a life after. I’ve made plenty

of mistakes; I’ve hurt myself and other people, so you begin to question whether you have any worth moving forward and is there grace or love to be found in any direction. As much as these stories feel different, and as much as I know some people feel that the landscapes and even racial dynamics are different, for me there’s a clear through-line.

What do you look for in your director of photography? I want a soldier who’s gonna share that foxhole. I can’t think of a closer relationship than the one you have with your director of photography. Forgive the analogy, but they’re literally shining light on your dreams. Above anything else, I need that encouragement to communicate. One thing that Amy and I found this time was a game changer: We took the van ride together every morning to location. They’d pick her up and then me, and we would talk and dream about

the day and what we were shooting. And Amy would be texting her team the ideas right then and there. I think that if we had planned too much early on, it would’ve lost the urgency of that moment – the ideas that come when you’re truly backed up against the wall of time and schedule. It’s a relationship that is completely about communication and trust. I love that.

Those are two things you clearly have in spades with Amy Vincent, as you’ve worked together for twenty years. To me, the results feel like you’ve reinforced each other’s good habits. Well, I think when you’ve got family, family will show up. You know they will bend but not break and say, “Kiss my ass” and hit the road. I don’t think there’s really much negativity there, only, maybe, what comes about from the battle. The battle for not only just making your day, but making a day where you walk away with that magic. That you somehow caught

BEST PICTURE

CINEMATOGRAPHY

MICHAEL BAUMAN

“Michael Bauman’s vividly textured cinematography is a sight to behold.”

– INDIEWIRE

something that maybe you planned for, but, more times than not, it’s those elements that you weren’t planning on that ultimately define the work and the image.

Does Amy fight for her ideas? She is always fighting for the image and every once in a while, I’ll be a bit like the brother to her sister, and going: “I see what you’re doing. But just remember I call action and I’m gonna call it in 60 seconds, starting now.” [Laughs.] And, Amy will be tweaking the shot all the way up to that 60 line, and then I’ll give her another 10 in those tough situations. What’s great about us is that when I call cut, and the day is finished, we give each other a big old hug, and we’re right back to where we are. Especially on this last movie. I needed to have someone I trusted that I could, more times than not, turn to her and say, “Where’s the master on this?” I can tell you where I want it to move, but

don’t put a 40-millimeter on a finder for me. Just find it. Yes, I’m gonna look at the monitor and give some adjustments. But I want to be surprised, because we just felt like there was a comfort, and I don’t know if I would’ve been that trusting with a new situation. I also knew that the subject matter, and what we were trying to make, was close to Amy and close to myself, and we wanted to do our best. Sometimes the best thing to do with someone as talented and knowledgeable as Amy is just get out of her way.

The industry is going through some major shifts – has been for a while. Any thoughts? There is a lot of uncertainty on so many levels. People don’t know if where they live there will be an industry anymore. They’re concerned about tools they think might replace a tremendous amount of crafts and jobs. I think the larger thing that we’re afraid of, though, is

what is everybody going to want? Not just the people who make the entertainment, but the people who consume it. Do they want cinema anymore? I take comfort that since the dawn of man, we’ve never quite kicked this need for storytelling. There is something so deep within us all that needs to know we’re not alone. Sure, we can get it from family, marriage, friendships, work, but really, we need to sit in a dark place and we need to look at a flickering light to see these stories that tell us that this pain you have is in this story and here in this story and this one. I don’t think that that’s going to go away.

Can a technology like AI be a positive disruption? One advantage of AI, and the tools that are coming, is that they might just usher in a lot more storytellers. This is largely still a privileged art form. You need a lot of money and a lot of industry behind you to tell these stories. I came up in a digital world where

someone handed me a Hi-8 camera and said, “You know you can make a feature film with this?” So many people told me no, that I had to shoot 35mm or 16mm and do a 35mm blowup. They had all these rules, but I was working in Receiving at Barnes and Noble; I didn’t go to film school. I was just passionate about making movies on the streets of Memphis. And now, I just did a feature with Amy where we shot our first digital film. I know that the industry is going through a transition, but I think we all need to trust that audiences are still going to want to see authentic storytelling from human beings.

Sundance is where you got your break. Do you think anything like that exists for young, scrappy, ambitious filmmakers these days? I’m going to be controversial here. I lived the dream that I’d read about in books when I got my 35 percent discount at Barnes and Noble. I made Hustle & Flow, and the premiere blew the

EXPOSURE

doors off the Eccles Theater [at Sundance]. It was in a bidding war for a 16-million-dollar deal, and then it went on to win an Academy Award [for Best Original Song] and Terrence Howard was nominated. Suddenly, I had a career in filmmaking. And the festival circuit worked swimmingly. I don’t think we’re there anymore. I do think that festivals still serve a purpose in introducing new minds and new films, but we must be honest about the market part of that hierarchy and the publicity elements of that whole venture.

Honest how? The tail may well have been wagging the dog for many years, and we felt okay about that because some great movies got to premiere at big festivals and then be in the multiplexes later. Today, I would tell a new filmmaker to figure out a way to go directly to theaters. Like what I did with The Poor & Hungry, a black-and-white digital movie that

I still think is some of my best work. It went to the Hollywood Film Festival, and nobody bought it. But, there was a lot of press in Memphis. The local theater chain asked if I’d like a week-long run and made a deal with me like I was the studio. I got half the house for that week, and I filled the seats every night. I outsold Gladiator! And they gave me another week. It ran six weeks, and I made back the $20,000 that I spent making the movie. There are opportunities to make that kind of a deal nowadays. I’m not saying don’t do the festival circuit, but I think that that dream of what they used to be is as fruitful as the dream of what a college education is supposed to get you in terms of employment. Put energy into cultivating an audience. Go to direct distribution. There are other models out there that filmmakers should try. And if that’s not working, know that it might be time to let it go and move onto your next project.

THROUGH THE YEARS

1927 – THE JAZZ SINGER POPULARIZES SYNCHRONIZED RECORDED DIALOGUE AND MUSIC, USHERING IN THE ERA OF THE “TALKIES.” BY THE END OF 1929, HOLLYWOOD IS PRODUCING ALMOST EXCLUSIVELY SOUND FILMS, MARKING THE END OF THE SILENT ERA.

1926 – IATSE LOCAL 644, THE FIRST UNION FOR CINEMATOGRAPHERS, IS CHARTERED IN NEW YORK CITY.

1929 – A THIRD MAJOR LOCAL FOR CAMERA CREWS, IATSE LOCAL 666, IN CHICAGO, IS FORMED.

1928 – A SECOND CAMERAMEN’S UNION, IATSE LOCAL 659, IS CHARTERED IN LOS ANGELES.

1989 – THE FIRST AVID PROTOTYPE DEBUTS, ENABLING FRAMEACCURATE, FLEXIBLE DIGITAL EDITING AND REPLACING TAPE-TOTAPE LINEAR WORKFLOWS.

1980s – THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER IS ARCHIVED AT THE ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES LIBRARY, SPANNING FROM 1929 TO PRESENT.

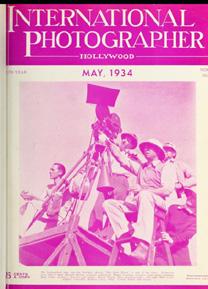

1934 – THE MITCHELL BNC CAMERA SYSTEM, WITH ITS NEW BLIMPED DESIGN (SOUNDPROOF HOUSING) GEARED TOWARD TALKING PICTURES, BECOMES A HOLLYWOOD WORKHORSE.

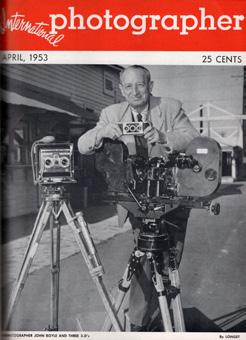

1929 – ICG MAGAZINE’S HISTORICAL ANTECEDENT, THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER IS LAUNCHED BY LOCAL 659 (LOS ANGELES) WITH SILAS EDGAR SNYDER AS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, IRA B. HOKE AS ASSOCIATE EDITOR, AND LEWIS W. PHYSIOC AS TECHNICAL EDITOR.

1994 – SUZANNE LEZOTTE BECOMES EDITOR OF THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER UNDER THEN LOCAL 659 PRESIDENT GEORGE SPIRO DIBIE, ASC.

1989 – PANAVISION RELEASES ITS PRIMO PRIME LENSES, WHICH QUICKLY BECOME THE OPTICAL STANDARD FOR HOLLYWOOD FEATURE FILMS.

1937 – THE ARRIFLEX 35, THE FIRST REFLEX VIEWING SYSTEM (MIRROR SHUTTER), IS INTRODUCED, ALLOWING THROUGH-THE-LENS COMPOSITION.

1935 – BECKY SHARP BECOMES THE FIRST FEATURE-LENGTH FILM TO SHOOT ENTIRELY WITH TECHNICOLOR’S THREE-STRIP (THREE-COLOR) CAMERA/PROCESS, INTRODUCING VIBRANT, REPRODUCIBLE COLOR CINEMATOGRAPHY.

1995 – THE ARRIFLEX 435/435ES COMES TO MARKET, BRINGING ELECTRONIC SPEED CONTROL AND ADVANCED FILM TRANSPORT CAPABILITIES TO 35MM CAPTURE.

1995 – ICG MAGAZINE (STILL KNOWN AS THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER) WINS ITS FIRST-EVER MAGGIE AWARD FOR “MOST IMPROVED MAGAZINE.” TWENTY-SEVEN MORE MAGGIES WOULD FOLLOW IN THE NEXT THREE DECADES.

1938 – JOHN CORYDON HILL JOINS THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER AS THE PUBLICATION’S FIRST ART DIRECTOR.

1940s –THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER PUBLISHES ARTICLES ON THE MANY LOCAL 659 MEMBERS DRAFTED INTO WARTIME FILM UNITS, AS WELL AS TECHNICAL ADVANCES BORN FROM WARTIME (FASTER LENSES, PORTABLE LIGHTS AND DURABLE CAMERAS).

1946/47 – "THE WAR FOR WARNER BROTHERS," THE FIRST MAJOR STRIKE IN HOLLYWOOD HISTORY ENSUES, INVOLVING THE MAJOR IATSE LOCALS, SAG AND CSU.

1937 – DISNEY’S SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS SHOWS HOW TECHNICAL ADVANCES (MULTIPLANE CAMERA, COLOR PROCESSES, SOUND DESIGN) CAN ENABLE NEW STORYTELLING FORMATS AND BIG BOX-OFFICE RETURNS.

1996 – IATSE LOCALS 644, 659 AND 666 MERGE TO FORM THE INTERNATIONAL CINEMATOGRAPHERS GUILD, LOCAL 600.

1995 – PIXAR’S TOY STORY BECOMES THE FIRST FEATURE FILM CREATED ENTIRELY WITH CGI.

1999 – SONY INTRODUCES THE F900, THE FIRST HD 24P DIGITAL CINEMA CAMERA.

1930s – THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER PUBLISHES REGULAR CONTRIBUTIONS FROM WORKING CINEMATOGRAPHERS, STILL PHOTOGRAPHERS AND LAB TECHNICIANS, AS WELL AS INCREASING UNION CONTENT: CONTRACT UPDATES, RATE SHEETS AND JURISDICTION NEWS.

2002 – NEIL MATSUMOTO BECOMES EDITOR OF ICG MAGAZINE, SERVING IN THAT ROLE FOR SIX YEARS.

1947 – THE ÉCLAIR CAMEFLEX DEBUTS. IT IS A COMPACT, HANDHELD 35MM CAMERA THAT FOREVER CHANGES NEWS GATHERING AND INTRODUCES CINÉMA VÉRITÉ TO NARRATIVE FILMMAKERS.

2002 – A CONSORTIUM OF MAJOR STUDIOS (DISNEY, FOX, PARAMOUNT, SONY, UNIVERSAL AND WARNER BROS.) FORM THE DIGITAL CINEMA INITIATIVE (DCI) TO ENSURE A UNIFORM STANDARD ACROSS DIGITAL PROJECTION SYSTEMS.

1999 – THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER CHANGES ITS NAME TO ICG MAGAZINE

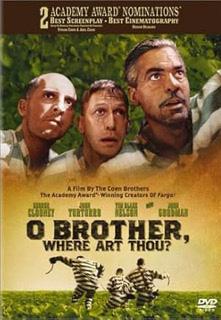

2000 – O BROTHER, WHERE ART THOU?, SHOT BY ROGER DEAKINS, ASC, BSC, IS THE FIRST HOLLYWOOD FEATURE TO USE A DI (DIGITAL INTERMEDIATE) POSTPROCESS, ENABLING FAR GREATER COLOR CONTROL AND VFX INTEGRATION.

2002 – THE SCREEN PUBLICISTS GUILD, FORMED IN 1937 TO REPRESENT HOLLYWOOD ENTERTAINMENT PUBLICISTS, MERGES WITH LOCAL 600.

2007 – THE RED ONE DIGITAL CINEMA CAMERA IS INTRODUCED, MAKING 4K RAW WORKFLOWS MORE ACCESSIBLE AND ACCELERATING THE MOVE TO DIGITAL CAPTURE ON BOTH LARGE PRODUCTIONS AND INDIES.

1954 – CINEMASCOPE ACCESSORY MAKER PANAVISION BRINGS SUPERIOR ANAMORPHIC AND SPHERICAL LENSES TO MARKET (REPLACING CINEMASCOPE OPTICS) THAT INCLUDE ADJUSTABLE FOCUS AND FLARE-CONTROL INNOVATIONS FOR WIDESCREEN LENS CAPTURE.

1953 – HENRI CHRÉTIEN’S ANAMORPHIC LENSES, WHICH SQUEEZE A WIDER FIELD OF VIEW ONTO STANDARD 35MM, ARE LICENSED BY 20TH CENTURY FOX. THE STUDIO RELEASES THE ROBE IN CINEMASCOPE, THE FIRST BIG WIDESCREEN EXHIBITION FORMAT.

1950s – LOCALS 644, 659 AND 666 CONTINUE TO OPERATE UNDER A “TRI-LOCAL” SYSTEM (NEW YORK, LOS ANGELES AND CHICAGO), COVERING CINEMATOGRAPHERS/CAMERA CREW WITHOUT A UNIFIED NATIONAL STRUCTURE. THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER’S COVERAGE IS DOMINATED BY NEW WIDESCREEN FORMATS, THE IMPACT OF TELEVISION AND STUDIO PUBLICITY METHODS.

1956 – THE AMPEX VRX-1000 BECOMES THE FIRST COMMERCIAL VIDEOTAPE RECORDER FOR TV STATIONS, REPLACING KINESCOPES FOR RECORDING BROADCASTS AND SETTING THE TABLE FOR THE ELECTRONIC EDITING AND TAPELESS WORKFLOWS THAT FOLLOWED.

2007 – NETFLIX LAUNCHES “WATCH NOW,” AN ON-DEMAND, INTERNETDELIVERED LONG-FORM VIDEO “STREAMING” SERVICE (INITIALLY AS A COMPLEMENT TO DVD RENTAL), FOREVER CHANGING FILM/TV DISTRIBUTION MODELS.

2009 – ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER TERESA MUÑOZ BECOMES PUBLISHER OF ICG MAGAZINE, SERVING IN THAT ROLE THROUGH 2025.

2008 – DAVID GEFFNER AND WES DRIVER TAKE OVER ICG MAGAZINE AS EXECUTIVE EDITOR AND ART DIRECTOR, RESPECTIVELY, SERVING IN THOSE ROLES THROUGH 2025.

1971 – JVC, SONY AND MATSUSHITA

COLLABORATE TO CREATE THE FIRST CASSETTE FORMAT (U-MATIC) THAT IS A UNIFIED STANDARD.

1960s – THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER HIGHLIGHTS NEW LIGHTWEIGHT CAMERAS (ARRIFLEX, ÉCLAIR), FASTER FILM STOCKS AND HANDHELD AND DOCUMENTARY-STYLE SHOOTING, AS WELL AS HOLLYWOOD LABOR TURMOIL – I.E., STRIKES AND JURISDICTION DISPUTES.

1972 – PANAVISION INTRODUCES ITS LIGHTWEIGHT PANAFLEX 35MM CAMERA SYSTEM, WHICH SOON BECOMES A WORKHORSE FOR HOLLYWOOD PRODUCTIONS.

1972 – THE ARRIFLEX 35BL, A QUIET, PORTABLE, SYNC-SOUND 35MM SYSTEM, COMES TO MARKET, ALLOWING THE “NEW HOLLYWOOD” FILMMAKERS TO SHOOT ENTIRELY ON LOCATION.

2010 – ICG MAGAZINE IS REVAMPED TO INCLUDE POPULAR NEW ANNUAL OFFERINGS, INCLUDING THE PRODUCT GUIDE, THE INTERVIEW ISSUE AND GENERATION NEXT.

2012 – ICG MAGAZINE RE-LAUNCHES ITS WEBSITE FEATURING AN ENHANCED USER EXPERIENCE AND INCREASED MONTHLY CONTENT.

1975 – ZEISS RELEASES ITS FIRST SUPER SPEED LENS (B-SPEED – MKI), THE FASTEST CINEMA LENS OF ITS KIND WITH A T1.4 APERTURE.

1975 – LOCAL 659 CAMERA OPERATOR GARRETT BROWN DEBUTS THE STEADICAM ON THE FEATURE FILM BOUND FOR GLORY. THE RIG’S STABILIZED, FLUID CAMERA MOVEMENT – LACKING TRACKS OR CRANES – FOREVER CHANGES THE LANGUAGE OF CINEMATOGRAPHY.

2015-2022 – WIDESPREAD CONSUMER ADOPTION OF 4K/UHD, HDR AND IMMERSIVE AUDIO FORMATS (DOLBY VISION/ HDR10, DOLBY ATMOS) CHANGES PRODUCTION DELIVERABLES AS THE STREAMING MARKET EXPLODES WITH NEW HOLLYWOOD PLAYERS (AMAZON, HULU, DISNEY+, APPLE TV+), CREATING THE “STREAMING WARS.”

1976 – THE “DYKSTRAFLEX” MOTION-CONTROL CAMERA SYSTEM IS CREATED AT A WAREHOUSE IN VAN NUYS, CA, THE HOME BASE FOR THE UPSTART VISUAL EFFECTS COMPANY INDUSTRIAL LIGHT & MAGIC. THE SYSTEM IS THE FIRST TO USE MOTION CONTROL TO EXECUTE REPEATABLE EFFECTS PASSES FOR THE 1977 SCI-FI RELEASE STAR WARS

1975 – CANON’S FIRST VENTURE INTO THE HIGH-SPEED CINEMA LENS MARKET, THE K35, WINS A TECHNICAL OSCAR (1977) AND IS REDISCOVERED BY FILMMAKERS IN THE 2020s SEEKING VINTAGE GLASS WITH SOFT CONTRAST AND WARM COLOR RENDITION.

2020 – ICG MAGAZINE SHIFTS TO AN ALL-DIGITAL (10 ISSUES PER YEAR) MODEL WHEN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC SHUTS DOWN ALL U.S. PRODUCTION.

1970s – THE INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER EXPANDS COVERAGE OF NEW ZOOM LENSES AND LOCATION FILMMAKING, ADDING INCREASED LABOR AND POLITICAL CONTENT AS HOLLYWOOD UNDERGOES A SHIFT IN PRODUCTION.

2025 – ICG MAGAZINE LAUNCHES ITS FIRST-EVER PODCAST, ENTITLED OUTSIDE THE FRAME, VISITING WITH DP KRAMER MORGENTHAU, ASC, AND DIRECTOR JULIUS ONAH FROM CAPTAIN AMERICA: BRAVE NEW WORLD FOR THE INAUGURAL EPISODE.

2009 – ICG MAGAZINE LAUNCHES ITS FIRST-EVER “SNOWDANCE” PARTY AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL, A YEARLY EVENT FOR ICG MEMBERS, VENDORS AND CREATIVE PARTNERS VISITING PARK CITY WITH INDIE PROJECTS.

2010 – THE ARRI ALEXA COMES TO MARKET AND SOON BECOMES THE BENCHMARK DIGITAL CINEMA CAMERA FOR THE FILM AND TV INDUSTRY.

2012-2020 – ICG MAGAZINE WINS 19 MAGGIE AWARDS (INCLUDING “BEST OVERALL DESIGN” - TRADE MAGAZINE) SIX TIMES IN AN EIGHT-YEAR PERIOD.

2020 – ICG MAGAZINE PUBLISHES THE FIRST OF MULTIPLE COVER STORIES ON DISNEY/ ILM’S GROUNDBREAKING USE OF AN LED VOLUME (REAL-TIME VIRTUAL PRODUCTION) FOR THE MANDALORIAN, SHOT BY GREIG FRASER, ASC, ACS; AND BAZ IDOINE.

2020 – ICG MAGAZINE INTRODUCES ITS “DEEP DIVE” SERIES OF VIRTUAL FILMMAKING PANELS TO STAY CONNECTED WITH AN INDUSTRY QUARANTINED UNDER COVID. THE SERIES WOULD RUN THROUGH 2025 AND INCLUDE THREE IN-PERSON PANELS, ALONG WITH EIGHT VIRTUAL SESSIONS.

A CENTURY OF INNOVATION, DEDICATION AND COMMUNITY

SAYING GOODBYE TO ICG MAGAZINE IN THE WORDS OF THOSE WHO KNEW IT BEST.

It’s a very tall task to summarize a century’s worth of filmmaking knowledge, talent, personalities and community in a few pages. So, for this final issue of ICG Magazine, we thought it best to let some of those closest to the publication – past and present – have the last word. We asked them one simple question:

“What did ICG Magazine mean to you (on and off the set)?”

QUOTES HAVE BEEN EDITED FOR LENGTH

“OUR BELOVED MAGAZINE WAS MORE THAN 96 YEARS OLD, AND FOR ALL THOSE YEARS IT FAITHFULLY CONNECTED WITH OUR MEMBERS, THE CREWS WE WORKED WITH, AND THE COMMUNITY AROUND US. MANY KNEW WHO WE WERE BECAUSE THE MAGAZINE WAS OUR PUBLIC VOICE. WE WERE ALWAYS PROUD UNION MEMBERS, PROUD TECHNICIANS AND ARTISTS WHO MADE THE MOVIES, TELEVISION SHOWS, THE SPORTS AND SPECIAL EVENTS THAT ENTERTAINED AND INFORMED THE WORLD. MOST OF ALL WE WERE A FAMILY, AND OUR MAGAZINE TOLD THAT STORY BRILLIANTLY.”

STEVEN POSTER, ASC ICG PRESIDENT FOR 13 YEARS ICG MEMBER FOR 56 YEARS

“My involvement with ICG Magazine started over 35 years ago when then-President George Spiro Dibie, ASC, asked me to serve as the copy editor. Since I was already an avid reader of the publication, I was thrilled to accept. Not only has it been a pleasure working with David, Teresa, Wes and the rest of the team, but I’ve also gotten tremendous satisfaction by watching the magazine grow, evolve, and win multiple Maggie Awards. I will dearly miss ICG Magazine!”

PETER BONILLA DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

COPY EDITOR, ICG MAGAZINE

ICG MEMBER FOR 48 YEARS

“I was so sorry to hear of the demise of the ICG Magazine , which I have been reading from cover to cover for almost 50 years! The magazine started as my guiding light through all of the steps in my career – from film loader to second assistant to first assistant to camera operator to director of photography to my acceptance into the ASC. Thank you to the magazine’s staff for all of the support and attention to detail throughout the years. Here’s to hoping that our paths all cross again.”

GARY BAUM

4X EMMY-WINNING DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY ICG MEMBER FOR 44 YEARS

“ ICG MAGAZINE WAS A PLACE FOR LOCAL 600 MEMBERS TO SHARE THEIR CRAFT AND SHOW THE WORK THEY WERE PROUD OF. I SPENT SEVEN YEARS HELPING SUPPORT THEIR STORIES, AND IT WAS CLEAR THE MAGAZINE MATTERED BECAUSE THE MEMBERS CARED SO MUCH ABOUT WHAT THEY DO. IT WAS THEIR VOICE, AND I WAS GRATEFUL TO PLAY A SMALL PART IN SHARING IT.”

NEIL MATSUMOTO EDITOR, ICG MAGAZINE 2001–2008

“Even before joining Local 600, ICG Magazine was one of the things that made me feel truly connected to something bigger than myself. Every month, it landed in my hands like a reminder that what we do isn’t just a job. It’s a craft, a community and a collective with one another. Through its pages, and after being invited to join, I met my union brothers, sisters and kin – people whose work and words illuminated corners of our industry I might never have seen otherwise. The magazine was never about the latest gear or the biggest productions. It was about people. It was about the crew who together found and created poetry within a frame. Reading ICG always reminded me that behind every image is a family of workers who make it possible, and a union that has our backs when the lights go out. I take the responsibility of carrying that spirit forward very seriously. I try to stay informed, to stay connected and to remember that every one of us is a link in a long, proud chain of artists and technicians who have fought to make this a sustainable life. As ICG Magazine sadly ends, I find myself reflecting on how deeply it’s woven into the fabric of our shared story. A monumental loss to us all.”

GREIG FRASER, ASC, ACS OSCAR-WINNING (AND 3X OSCAR-NOMINATED) DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY ICG MEMBER FOR 16 YEARS

EVERY TIME I GOT A CALL TO DO AN INTERVIEW WITH ICG MAGAZINE, I FELT LIKE ALL THE WORK WE’D PUT IN WOULD BE NOTICED BY SOMEONE, NO MATTER HOW OUR MOVIE DID AT THE BOX OFFICE. IT WAS ALWAYS AN OPPORTUNITY TO HIGHLIGHT THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF ALL MY FELLOW SHOT-MAKERS – PERPETUALLY UNSUNG HEROES – AND MAKE SURE ANY UP-ANDCOMERS READING THE ARTICLE GOT TO SEE EXACTLY HOW IMPORTANT THE ROLE OF EACH POSITION IS ON THE ROAD TO MAKING MOVIES WE’RE ALL SO PROUD OF.”

MATTHEW MORIARTY, SOC PRESIDENT, SOCIETY OF CAMERA OPERATORS ICG MEMBER FOR 28 YEARS

“With every beautiful cover, ICG Magazine has been a joy to open, waiting to enlighten us about the diverse corners of our craft. It’s been the place to find insights and read about the real goings-on behind the lens – ready with the most in-depth impressions of a specific project or the expanse of a genre, so often revealing the distinct personality of the creatives and the technology behind the art. The industry will not be the same without the shining light of the always articulate, visually stunning and setsavvy ICG Magazine , and the team who created a vast new world with each issue.”

SUSAN LEWIS OWNER/PUBLICIST LEWIS COMMUNICATIONS ASSOCIATE MEMBER, ASC

“ICG Magazine has been a steady presence throughout my career, from my earliest days as a studio publicist to my work on set as a unit production publicist, and the projects I’m part of now. It consistently championed Local 600 cinematographers, crews and publicists with a level of insight, accuracy, and respect that few if any outlets ever matched, becoming a trusted partner in highlighting the artists and artisans who shape every frame. For me, it was both a bridge to my ICG sisters and brothers and an advocate for the people whose work often goes unseen. Its absence will be deeply felt, and I’m grateful to have been even a small part of its history along the way.”

GREGG BRILLIANT UNIT PRODUCTION PUBLICIST

MEMBER FOR 34 YEARS

“ ICG MAGAZINE ALWAYS RESPECTED THE WORK OF STILL PHOTOGRAPHERS, BOTH NEW AND ESTABLISHED. SOMETIMES, IT WAS THE ONLY PLACE WHERE MULTIPLE BTS SHOTS WERE PUBLISHED. IN THIS COMING AGE OF 10-SECOND VIDEO CLIPS, GIFS AND MEMES, OUTLETS LIKE ICG MAGAZINE WILL BE SORELY MISSED.”

MEMBER FOR 25 YEARS

“The experience of shooting features and episodic work is fully immersive and all-consuming. You become bonded with your crew and somewhat cut off from the world beyond – including the larger filmmaking community. ICG Magazine has been my connection to that world, a way to keep up with friends and peers, their work, their approaches, and their mindsets. Even a single idea that sparks a new way of thinking is invaluable. I’ll miss turning the pages and discovering what’s inside.”

ARMANDO SALAS

2X EMMY-NOMINATED

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

ICG MEMBER FOR 12 YEARS

“Writing for ICG, I’ve covered this industry through a global pandemic, strikes, natural disasters and rapid technological change –and the good times, too, of course – reporting on these innovative, resilient, brilliant, humble, generous, union storytellers is what made my part so meaningful. There are many highlights, but the work I’m most proud of went beyond chronicling the craft to capturing the humanity of this community – how they advocated for representation or safety, how they gave each other days and opportunities, how they stood firm for equity and belonging. That’s a whole other kind of ‘set magic,’ and it was a privilege to share those moments with our readers.”

MARGOT LESTER

ICG WRITER FOR 17 YEARS

HOPPER STONE, SMPSP

AMY VINCENT, ASC, JOINS LONGTIME COLLABORATOR, WRITER-DIRECTOR CRAIG BREWER, FOR THE NEIL DIAMOND-ADJACENT BIOPIC SONG SUNG BLUE .

BEAUTIFUL

BY

FRAMEGRABS COURTESY OF FOCUS FEATURES

VALENTINA VALENTINI

PHOTOS BY SARAH SHATZ

AMY VINCENT, ASC, (ABOVE) BEGAN HER CAREER IN THEATER LIGHTING BEFORE WORKING HER WAY UP THROUGH EACH JOB IN THE CAMERA DEPARTMENT. SHE WAS ONE OF JUST A HANDFUL OF WOMEN WHO WERE EARLY INVITEES TO THE ASC.

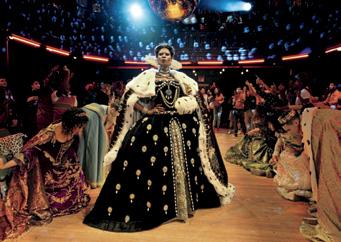

If you had to choose three words to describe Mike and Claire Sardina – aka “Lightning and Thunder, the Neil Diamond Experience” band – scrappy, ambitious, and passionate would fit. Likewise, those three words could be assigned to writer-director Craig Brewer and his longtime director of photography, Amy Vincent, ASC.

“I like to think that Craig and I have always kept our edge, even as we matured,” says Vincent, who was introduced to Brewer and his script Hustle & Flow through producer Stephanie Allain a few years before the 2005 film went on to win an Oscar for Best Song. Vincent, a graduate of the theater arts and film program at UC Santa Cruz who earned an MFA at the American Film Institute, came up through theater lighting to assistant editing to nearly all the ranks of the camera department. Her debut feature, Eve’s Bayou (1997), was accepted into the Library of Congress National Film Registry, and she was one of the first women to join the ASC. Vincent received the Women in Film Kodak Vision Award in 2001 and the ASC President’s Award last year. Her work on Hustle & Flow earned her Sundance’s cinematography award.

“During our time on Hustle & Flow ,” Vincent shares, “we were both learning so much. To come back together for Song Sung Blue with 20 years of experience behind us – he’s still the same incredible writer

and incredible human being, and the confidence that he has now really inspires me to raise my game.”

In Brewer’s early days of directing, as he was finding his footing on set, it was Vincent’s vibe that helped solidify their working relationship – jeans, combat boots and a motorcycle. “She was a soldier,” Brewer describes. “Always right there by the camera, and no matter what was coming, she faced it with fierce tenacity.”

The dynamic proved to be a winning combo. They went on to shoot Black Snake Moan (2006) and Footloose (2010) and are reuniting for Song Sung Blue, a film that is both sweet and sad, with visuals that draw the audience in so close it’s like watching a live performance from the first row. Based on a true story that Brewer adapted from Greg Kohs’ 2008 documentary of the same name, Song Sung Blue tells the fanciful tale of the Sardinas (Hugh Jackman and Kate Hudson) and their almost-rise to fame as a Neil Diamond tribute band in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

ABOVE/OPPOSITE PAGE: VINCENT SAYS A FOUNDATIONAL ASPECT OF THE LOOK CAME FROM CLASSICAL MOVIE STAR PORTRAITURE," COUPLED WITH REALISM AND AUTHENTICITY. "WE WANTED TO CENTRALIZE THE CREATIVE FOCUS ON THE PERFORMANCES AND FACES OF THE TWO STARS," SHE ADDS.

For this collaboration, Vincent wanted to steer away from their previous projects’ looks, which were all shot on film. And given the film’s long takes and concertstyle setups, digital capture would assure a different approach than past work.

“A foundational aspect of the look was to take great care, in a classical sense, of movie star portraiture and photography,” Vincent describes. “But at the same time we needed to keep the film grounded in realism and authenticity because of its true story origins.” Vincent had detailed conversations with Jackman’s makeup artist, Pamela Westmore; his hair designer, Sean Flanigan; Hudson’s makeup artist, Debra Ferullo; and her hair designer, Johnny Villanueva, about centralizing the creative focus on the performances and faces of the two stars but also being able to expand it out into a naturalistic love story.

“Craig and I love to work in the Kelvin scale,” Vincent continues. “So much of the storytelling can be told in the range of warm to cool. I often use a saturated deep orange, offset by saturated blues, and we love our deep blacks. I think you can see that

through the course of our collaborations.”

Vincent calls it a “privilege” to be able to work with Company 3 Senior Colorist Tom Poole, noting that “during preproduction, we shot extensive hair and make-up tests with our cast, complete with costumes and art direction and tungsten lighting, enabling Tom to create an extraordinary show LUT. We played around with a chalky slate-blue fall-off, in the blacks, and a slight warming of the actors’ faces, all the while maintaining a distinctive look, akin to Brewer’s and my tastes. We stuck with the singular LUT throughout the film.”

Song Sung Blue was shot entirely on location in New Jersey (playing for Milwaukee from the mid-1980s through mid-90s). Kohs’ documentary provided extraordinary historical research for an intimate look into the Sardinas’ world, which Brewer and Vincent, along with the entire creative team, used extensively. Indeed, Production Designer Clay A. Griffith says it was their touchstone document.

“The challenges of shooting an alllocation movie in New Jersey were many,” recalls Griffith, who designed Dolemite Is

My Name for Brewer. “Given the time of year, with beginning principal photography in mid-October, we knew we were going to be up against some cool weather conditions, and no stage sets to get the crew out of the onset of winter. We toughed it out in our last weeks of shooting, finishing our schedule in mid-December, and the Jersey weather showed little signs of mercy.

“On the other hand,” Griffith adds, “this was my first time shooting a project there, and I have to say that I found it thrilling to scout an entire state that has been mostly untouched by film productions. From a design point of view, New Jersey locations have a tremendous amount of grit and character. A perfect stand-in for the Rust Belt of Wisconsin – it reeks of history and urban architecture. Recreating the early nineties was accomplished through wardrobe, periodcorrect automobiles, authentic signage/ graphics and the lack of digital electronics. We chose New Jersey as our base largely due to the timeless locations that exist there with robust working-class neighborhoods and a topography and infrastructure that matched Wisconsin almost perfectly.”

“SO MUCH OF THE STORYTELLING CAN BE TOLD IN THE RANGE OF WARM TO COOL. I OFTEN USE A SATURATED DEEP ORANGE, OFFSET BY SATURATED BLUES, AND WE LOVE OUR DEEP BLACKS.”

DIRECTOR

OF PHOTOGRAPHY

AMY VINCENT, ASC

It was immensely important to Brewer to show a working-class family accurately without feeling like they lived in a dreary landscape. “Yes, there can be clutter, there can be dingy bars,” the director reports. “But we still wanted to believe in an aspirational feeling when you’re in these places, that we’re not here to judge, but we’re here to give an epic retelling of people on the margins. So, every chance that we could get, we’d find those opportunities. This meant we talked a great deal about color – how, when we were in a muted landscape, do we achieve that saturated, magical realism?”

Vincent had three Sony VENICE 2s to work with at 8.6 K in a 1:1.85 aspect ratio. She leaned into her familiarity and comfort level with the VENICE sensor and color science and found its dual ISO capabilities useful for the film’s location work, especially the smaller nightclubs and bars, and night interior work at the family home. For broadcast segments, they had an old DVW700WS (recorded onto an Odyssey external recorder) and used a Sony DCR-TRV120 Hi8

tape to portray the Handycam work filmed by Sardina’s son.

For lenses, Vincent was excited to pair the Leitz Cine Hugos with the VENICE2. “I’ve long been a Leica glass user, both for cinema and still photography, especially fond of M.08s, and I often shoot with Leica Summilux C lenses,” she shares. “The Leitz Hugos use the M-series glass, described as ‘vintage/modern’ – they have a beautiful fall-off on the edges, all contained in a compact, lightweight build. I love the way the focus falls away in foreground elements in close focus. I also wanted a family of fullframe zooms for three cameras during live performances and was easily able to match the Fujinon Premistas with the Hugos.”

Tucked away in tiny houses and low-ceilinged dive bars, it was a unique opportunity to recreate the lives of the Sardinas. Griffith recounts Brewer giving his design team an inspiring clue to the family’s journey: It might look like a mess in here, but it’s my mess.

“This era was pre-digital, pre-

electronic, pre-cell phone, pre-apps, and pre-all the stuff we know now to be part of our daily routines,” says Griffith. “You knew where your piles of stuff were, and you kind of knew what each pile represented.”

Griffith had Set Decorator Lisa Sessions Morgan to create said piles. “If it’s not written on the page, I like to create my own backstory,” says Morgan, who first worked as an additional buyer to Griffith’s set decorating on Se7en . “[The documentary] was pure gold, but the challenge was: How much of their real life do we emulate? I remember Angela, our art director, and I would converse at length about how to convey that on the screen. I decided the best approach was to streamline the dressing to fit our [leads]. I wanted Claire’s life to feel busy and slightly out of control and keep Mike’s house sparser and lonelier. My theory was that only when they got together and their lives intertwined did their home reach pure harmony. It also was intended to ebb and flow depending on their circumstances in the film.”

ABOVE/OPPOSITE: BREWER SAYS IT WAS IMPORTANT TO PORTRAY A WORKING-CLASS FAMILY ACCURATELY WITHOUT FEELING LIKE THEY LIVED IN A DREARY LANDSCAPE. "WE’RE NOT HERE TO JUDGE," HE SHARES. "WE’RE HERE TO GIVE AN EPIC RETELLING OF PEOPLE ON THE MARGINS."

Vincent credits Morgan with being integral to creating window dressings that helped them cheat night for day or day for night. “Amy had a true vision of how she intended to shoot the movie and was very collaborative on how we could make it happen,” says Morgan, who met the DP when Vincent was the key second assistant camera on Natural Born Killers “Since there are no prop houses in New York filled with vintage drapes,” Morgan adds, “I appreciated her letting me know early on how important each window and its treatment was in her lighting. We wanted to make sure that if we were shooting night during the day, each window had enough layers or filtering that it wouldn’t look like a black hole from the black tenting over each window. Creating ‘window vignettes’ became a buzzword for me and my assistant decorator, Roxy Toporowych. There were lots of eBay and Etsy fabrics shipping in and going to our draper in New York City.”

For these quietly beautiful and universally relatable domestic scenes, Chief Lighting Technician Daniel McCabe often

used Litemats, Astera tubes in light socks with custom louvers, Creamsource panels, HMI’s, and a small Fiilex G3 ellipsoidal unit that Vincent is partial to. This is in great contrast to the performance scenes Lightning and Thunder have. Starting in small dives and going all the way to the main stage in Milwaukee, theatricality and lighting increased as the story progressed.

“These people lived a lo-fi existence,” says McCabe, who recently gaffed Dying for Sex and worked under longtime lighting sensei Andy Day with Jackman on The Greatest Showman . “Amy wanted to use more hot lights than many shows often use these days, which was both period appropriate and a great chance to get back to my pre-LED-era training. Amy has an intuitive approach to visual storytelling, and I was grateful to find an early trust with her. I was also blessed to have a great working relationship with Key Grip Brendan Lowry – one of the best of our generation.”

One of the most important date-stamp aspects for Vincent was sourcing periodaccurate performance lighting. “The oldschool PAR cans and gel colors, that was the centerpiece for me,” says Vincent. “I

was raised photochemically, so going back to the discipline of tungsten lights with gels is a joy. I began lighting for theater, which made working with theatrical lighting designer Christina See for the big show at The Ritz so special.”

The finale, when Lightning and Thunder play to a packed house at The Ritz, was rehearsed and performed, for the most part, like a live show. Brewer likes to run long takes when it comes to capturing musical performances, and this one was three numbers running together – though it was shortened to two for the film. In real time, it was about 12 minutes long.

See had worked with McCabe on Succession and Mean Girls (2024) and was no stranger to being called for bigger concert scenes in film and TV. Her designs have been on Succession (Kendall’s 40th birthday bash), almost the entire third season of Only Murders in the Building, and In the Heights. For Song Sung Blue, See knew Brewer and Vincent wanted that 80s/early 90s rock-show vibe.

“I drew sketches with the truss visible and narrow beams coming from the PAR cans, and a cyc behind the stage to add color and give it depth,” See describes. “I

looked up Neil Diamond’s shows because they’re a good example of that type of [lighting]. We stayed away from spinning lights that you’d see at a show today and stuck to focusable lights, which we could spin around and use as a key light or backlight depending on where we were shooting from and what the camera was seeing.”

See’s moving light programmer, Max Lagonia, previsualized the songs as Production was loading into the theater. “It’s always a fingers-crossed moment,” See continues, “when the rig turns on and we see if we got close to what we wanted. We were also using so much more power than people expected because it was all conventional lighting. We had 116 PAR 64s, three Lycian Medium Throw M2 2.5-kw Followspots, 30 Ayrton Huracan LT’s, 12 ETC Source Four Lustr 2 36 degree, eight Stubby PAR 56s and more. Max and I went on a little field trip to an old lighting company, United Stage Associates, for vintage fixtures. We rummaged through their warehouse to find a bunch of polished silver snubnose PAR cans.”

Adds Vincent: “The footlights were a big deal to me. They define the bottom of the frame of the proscenium when the camera is looking towards the performers. When the camera is behind the performers, a slightly cooler color temperature plays in the audience, the separation enhanced by the line of footlights. And the vintage fixtures themselves are quite beautiful.”

In addition to See’s theatrical rig and design, McCabe rigged Lekos with various lenses and, for closer shots, used big broad fill sources from stands in the pit – usually a LiteMat Plus 8 or SkyPanel S360 through 12×12 diffusion, and sometimes a 12K tungsten bounce.

“Doing the Ritz show was a real treat to go back to my roots – I love a PAR can like nobody else!” Vincent enthuses. “A big part of what makes that sequence work was Christina’s design and Max’s programming into our modern lighting technologies coupled with old-school followspots and their operators. Truly, that whole show was a coming together of all departments. I had A-Camera Operator Dave Thompson and Dolly Grip extraordinaire Andy Sweeney on the Technocrane with a Matrix head from Monster Remotes. We worked in broad strokes with a few punctuation points. I’d let them know, ‘At the end of this verse you need to land in symmetry on the wide of the 19-45.’ And I’d let these extraordinary craftspeople, technicians and artists do their jobs.”

Vincent says, as a department head, it’s a sign of creative maturity that both she and Brewer were willing to cede so much to their fellow union craftworkers. “It’s what was so special about the finale at the Ritz,” she concludes. “You give them their marks, but then we roll in real time, and I think the music is so inspiring along with Hugh and Kate’s performance, that it all just comes together seamlessly.”

LOCAL 600 CREW

Director

A-Camera

A-Camera

VINCENT SAYS DOING THE BIG FINALE AT THE RITZ WAS A CHANCE TO GO BACK TO HER ROOTS. "I LOVE A PAR CAN LIKE NOBODY ELSE!” SHE ENTHUSES. “AND A BIG PART OF WHAT MAKES THAT SEQUENCE WORK WAS CHRISTINA’S DESIGN AND MAX’S PROGRAMMING INTO OUR MODERN LIGHTING TECHNOLOGIES COUPLED WITH OLDSCHOOL FOLLOWSPOTS AND THEIR OPERATORS. IT WAS TRULY A COMING TOGETHER OF ALL DEPARTMENTS."

border

ELEVEN-TIME OSCAR-NOMINATED WRITER/DIRECTOR PAUL THOMAS ANDERSON AND DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY MICHAEL BAUMAN RESURRECT VISTAVISION FOR A HIGH-OCTANE AMERICAN ROAD ODYSSEY.

BY JAY KIDD

BY MERRICK MORTON, SMPSP

FRAMEGRABS COURTESY OF WARNER BROS.

lines

PHOTOS

“It’s 100 degrees, we’re dying, the cameras are jamming, and there’s no bathroom,” laughs Director of Photography

Michael Bauman, recalling the grueling conditions he and his Local 600 camera team endured on Writer/ Director Paul Thomas Anderson’s recent Warner Bros. feature, One Battle After Another. “Our love language as a crew was definitely sarcasm and dry irony. You just had to have a sense of humor to roll with it all.”

Loosely adapted from Thomas Pynchon’s novel Vineland, One Battle After Another tells the story of Bob “Rocketman” Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio), a washed-up former revolutionary who is forced back into his old lifestyle when a corrupt military official (Sean Penn) kidnaps his teenage daughter (newcomer Chase Infiniti). The story feels urgent, unfiltered, like it’s been shot out of a cannon, and the camera crew chased it through the streets, rooftops, and deserts of America with every ounce of energy they had.

The project is the fifth feature film Bauman has shot for Anderson, but it is their first lensed in VistaVision. In fact, Battle is the first major U.S. feature both photographed and released in VistaVision since Strategic Air Command in 1955! Still, this wasn’t completely uncharted territory. In 2019, Anderson and Bauman experimented with VistaVision on Anima , a short film made to accompany Thom Yorke’s album of the same name. Ever since, the director has

been itching to see what would happen if he built a full-length movie around the format.

It’s easy to see why Anderson fell in love with the format. VistaVision carries a mythic pedigree, having captured the shimmering dreamscapes of Hitchcock’s Vertigo and the wind-scoured horizons of John Ford’s The Searchers. The magic lies in its design: unlike standard 35 mm, which runs film vertically through the camera, VistaVision runs it horizontally, exposing a larger 8-perf frame on the same stock. What results is a deeper, richer image that feels impossibly detailed. For a time, it was Hollywood’s most advanced format until newer technologies pushed it aside. Even then, VistaVision found a second life in visual effects, most famously on the original Star Wars trilogy. Anderson, however, had a very different goal. “Our North Star, visually, was The French Connection,” Bauman recalls. “We wanted to take this pristine format, gorgeous 8-perf VistaVision, and make it look like that movie.”

He describes their mission as an exercise in contrast. “When people think of VistaVision, they think of this glorious, perfect picture,” Bauman adds. “But Paul was like, ‘No, screw all that! We’re going to strap this camera to cars. We’re going to put it on a Steadicam, on a helicopter. There’s going to be lots of movement. We’re going to loosen the bolts and see what happens. Let’s muck it up.”

Resurrecting VistaVision for a fullthrottle action flick was not an easy task. The last cameras had rolled off the assembly line some twenty-five years ago, and the remaining units had spent decades gathering dust.

“VistaVision in its current iteration is not intended for narrative filmmaking at all,” explains the film’s 1st AC Sergius “Serge” Nafa. “It’s been used almost exclusively for visual effects for decades, and the only working cameras belong to a bunch of guys who basically rebuilt them in their garages.”

This production’s initial luck came

from Giovanni Ribisi, an actor and cinematographer who also restores vintage cameras. His personal Beaumont VistaVision camera became their template. Bauman vividly recalls the handoff: “I remember Paul saying, ‘Look, this camera is your baby. We don’t want to hurt it.’ And to Gio’s credit, he said, ‘This is for making movies. Go make a movie.’” Two additional Beaumonts were sourced from Geo Film Group, and with Panavision’s support, all three machines were brought back to life.

Nafa calls Ribisi “a godsend. His camera was brilliantly well-kept, so we used that as a model for the other two cameras,” the veteran AC shares. “Panavision handled the optical side, fabricating new eyepieces, replacing lens mounts, adding

HD taps, and solving our power issues. We had to update three different bodies to have the same genetic coding so they could withstand a twelve-hour day in the desert for 100 days straight. It’s like asking a Ferrari to run the Baja 1000. That’s not what they’re made to do.”

Some of the Beaucams’ problems couldn’t be fixed. “It’s an incredibly noisy camera,” says A-Camera/Steadicam Operator Colin Anderson, SOC. “It sounds like a coffee grinder.” As a workaround, the team supplemented with two Panavision Millennium XL cameras for long, dialogueheavy scenes. The 4-perf Super 35 mm footage from these cameras was then blown up to match the 8-perf VistaVision, maintaining visual consistency while capturing every second of the film’s rapidfire, often hilarious dialogue.

Operating the Beaucams brought its own ergonomic challenges. Because the system’s horizontal magazines sit differently than vertical 35 mm, they are tricky to operate. As Anderson continues, “Any camera position over chest height or higher became an issue. I’d have to stand on a box or a ladder to see through the eyepiece. One-hundred-and-eighty-degree pans were also a problem. I tend to be a little old school – I always want to look through the eyepiece. That makes me feel more connected to the shot. So, I had to do a lot of complex dolly moves, sort of contorted over the camera. That was a challenge, to say the least,” he laughs. “I’m glad I do a lot of yoga!”

The horizontal magazines also presented a challenge for Steadicam. Because VistaVision travels film from left to right, the weight shifts, throwing the rig off

balance. The fix came from Geo Film Group in the form of a brilliantly simple piece of vintage tech: a traveling weight that moves in opposition to the film. Anderson notes this same tool was once used by Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown while shooting background plates for the speeder bike chase in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi . “It’s an extraordinary piece of equipment and a nice bit of film history,” the operator shares. “Garrett Brown was a pioneer, so getting to use something of his felt wonderfully nostalgic.” Paired with Anderson’s Steadicam Volt system, the weight restored perfect balance to the rig, linking two eras of camera ingenuity.

A major chase that included a helicopter added another layer of complexity. Dylan Goss, the film’s aerial director of photography, was tasked with fitting the

“WITH PAUL, NOTHING COULD BE TOO CUTE, TOO SET UP, OR TOO CONTRIVED. THERE’S A CERTAIN LOOSENESS, A GRIT TO THIS FILM.”

A-CAMERA/STEADICAM

OPERATOR COLIN ANDERSON, SOC

with large-format magician Scott [‘Smitty’] Smith alongside the guys at Team5 going nonstop. I can’t stress how much we felt like we had done something that hadn’t been done before. I’m really proud of that.”

Paul Thomas Anderson was so fastidious about VistaVision that he even reached out to the cinematic community to source a VistaVision projector to review dailies with his crew. Every night, department heads would gather to watch, with Anderson himself often playing composer Johnny Greenwood’s developing score through his iPhone.

As Nafa recalls, “I never felt happier to come in battle-worn after a thirteen-hour day and watch an hour of dailies. It was so fun. It really helps with tone, because when you hear the music playing over the dailies, you begin to think, ‘Okay, that’s what we’re after.’ It subtly informs how we all do our jobs. Maybe the speed of a focus pull is going to be different now, based on my understanding of the dailies that I saw the night before.”

The French Connection’s influence on One Battle After Another is plain to see. Like its predecessor, the film used almost no built sets for its interiors. And, like the crew of The French Connection , the team on One Battle After Another faced punishing weather conditions – but instead of New York’s bitter winter, it was the scorching deserts of California and Texas. The car chases were captured practically: just a camera bolted to the hood, rattling and bouncing with every crunch and smash as the vehicles tore through traffic.

unwieldy Beaucam into a modern stabilized gimbal – a feat complicated by a 1000-foot magazine and massive 11:1 zoom. The biggest hurdle was vibrations. “That 1000foot magazine was shaking like an old Chevy,” Goss recalls. “When the camera vibrates on a gimbal, the image will be soft – even more so at the near-1000-millimeter focal lengths we were on. We had to find some way to brace the thing.”

After rigorous testing, a solution emerged: custom 3D-printed sandwich plates turned the curved VistaVision magazine into a perfectly flat surface, allowing it to be effectively clamped and stabilized. “I can’t think of another team that could have pulled this off,” Goss says. “I’m not speaking about myself; I mean the team at Geo Film Group and Panavision. We had James O’Hara, my gimbal tech, working