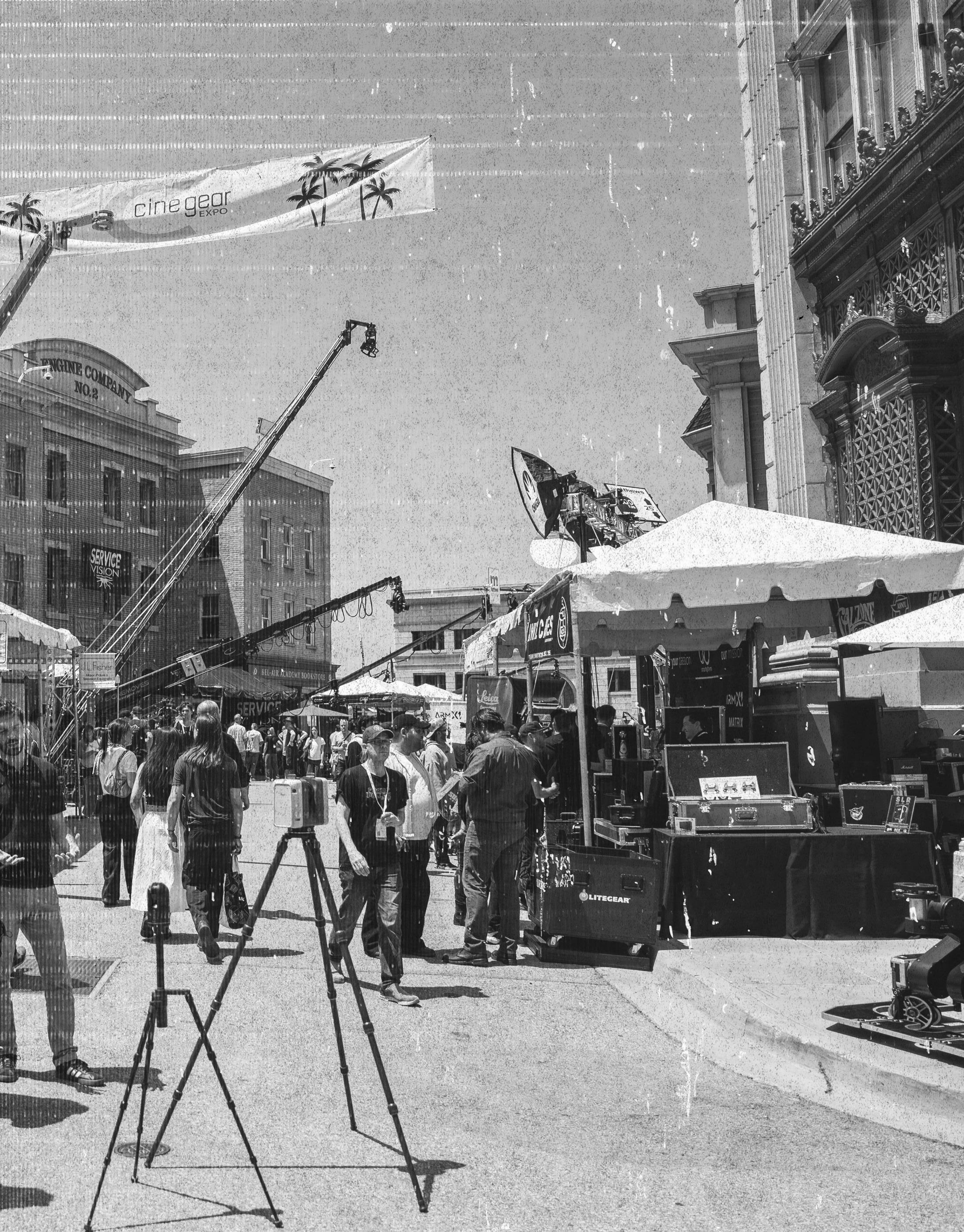

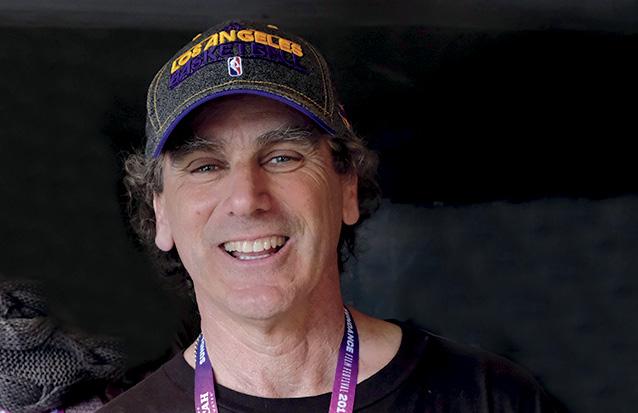

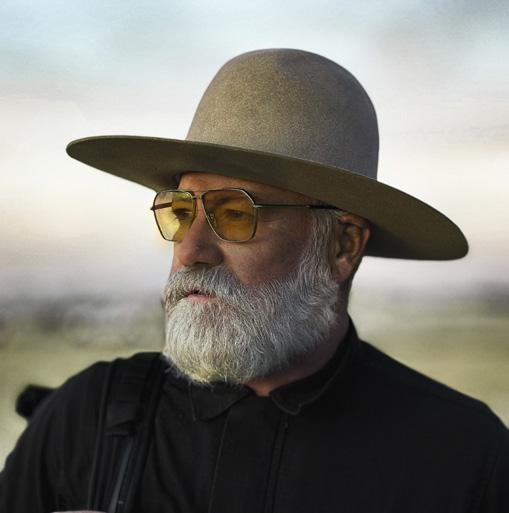

INTERVIEWS AT CINE GEAR EXPO

LOS ANGELES

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

ANA AMORTEGUI, ADFC

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

JESSICA LEE GAGNÉ

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

OREN SOFFER

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

HENRY BRAHAM, BSC

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

ADAM BRICKER, ASC WATCHNOW!

S

7kUailUega SKR Bgmc A6C 51

K g n ns 5 1 i i en p i S s 7 8 t o sn 06! e o r S m c 068 to sn 5! eor uhsg 05 rsnor ne cwmSiha pSmfd

Fhfg Odp enplWmad HmsdpmWi LdchW enp Pdanpchmf

I Wpfd EnplWs Rdmrnp

Ihud Rvma Wmc Cchs LdchW Sghid s gd BWldpW hr Pniihmf

T N R 8 B h m d q d b n q c r W m G C o q nw x h m G -15 3 h m W c c h s

7kUbilUegb SLR Bgmd .6C 51 Epnl !12$,54

“The report of my death was an exaggeration.”

Mark Twain may or may not have made this now famous statement, but in any case, he was still alive and in a good position to prove his existence. Over the years, other famous obituaries include the death of the novel, the theater, radio and on and on. A well-known streaming titan recently said: “Folks grew up thinking, ‘I want to make movies on a gigantic screen and have strangers watch them [and to have them] play in the theater for two months and people cry and sold-out shows’ … It’s an outdated concept.”

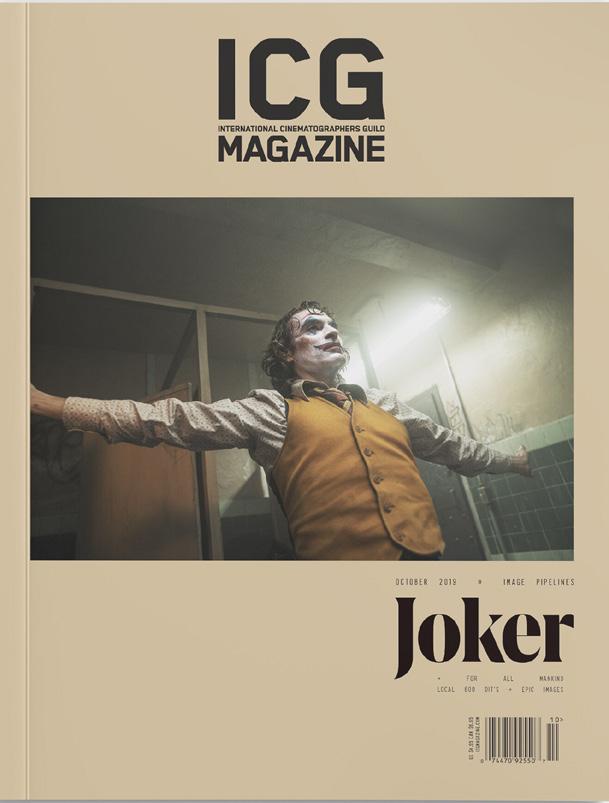

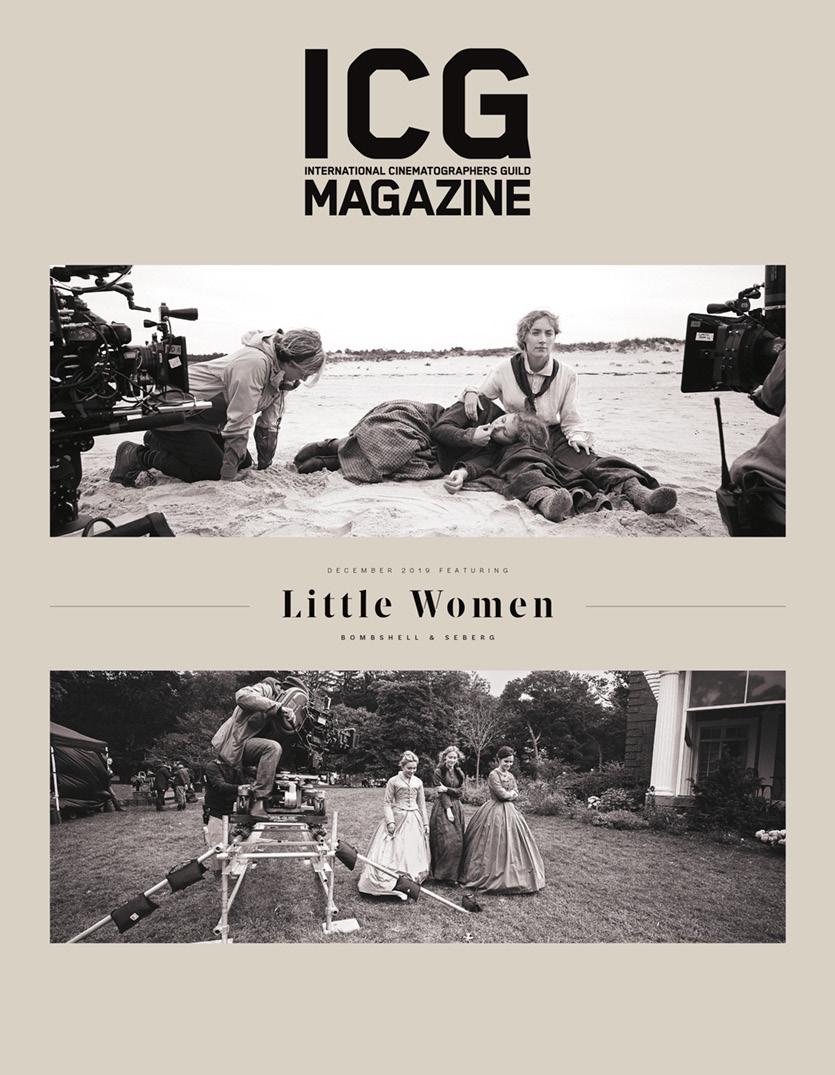

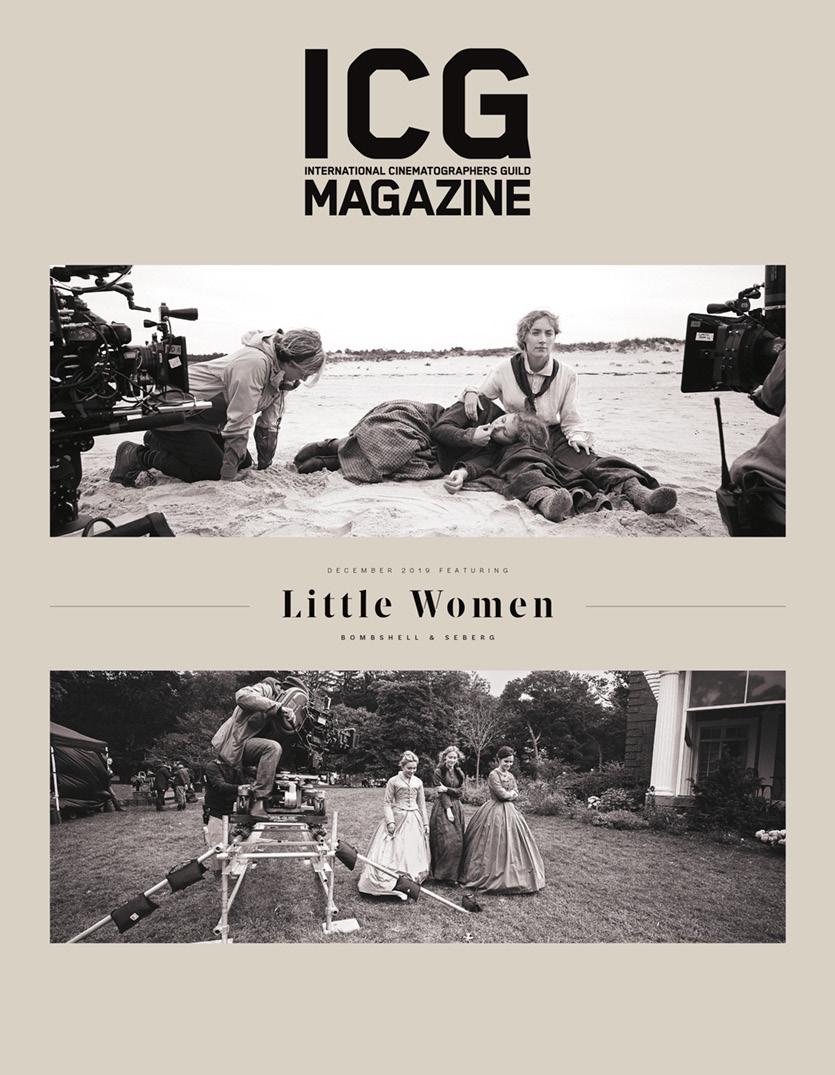

Maybe. But this month’s issue of ICG Magazine includes pieces about theatrical releases for which the technical innovations and artistry of our members can only be fully appreciated on a big screen. Their vision is worth fighting for as audiences continue to be drawn into theaters. As you read about the complex work that camera crews provided to bring these movies to their theatrical releases safely, despite some dangerous shooting situations, I hope you will agree: The death of the movie theater experience has been greatly exaggerated.

Publisher Teresa Muñoz

Executive Editor

David Geffner

Art Director

Wes Driver

NATIONAL DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Jill Wilk

COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

Tyler Bourdeau

COPY EDITORS

Peter Bonilla

Maureen Kingsley

CONTRIBUTORS

Scott Garfield

David Geffner

Matt Kennedy, SMPSP

Margot Lester

Parrish Lewis

Kevin H. Martin

COMMUNICATIONS & OUTREACH COMMITTEE

Jamie Silverstein, Chair

CIRCULATION OFFICE

7755 Sunset Boulevard

Hollywood, CA 90046

Tel: (323) 876-0160

Fax: (323) 878-1180

Email: circulation@icgmagazine.com

ADVERTISING REPRESENTATIVES

WEST COAST & CANADA

Rombeau, Inc.

Sharon Rombeau

Tel: (818) 762 – 6020

Fax: (818) 760 – 0860

Email: sharonrombeau@gmail.com

EAST COAST, EUROPE, & ASIA

Alan Braden, Inc.

Alan Braden

Tel: (818) 850-9398

Email: alanbradenmedia@gmail.com

Instagram/Facebook: @theicgmag

October 2025 vol. 96 no. 08

IATSE Local 600

NATIONAL PRESIDENT

John Lindley, ASC VICE PRESIDENT

Jamie Silverstein

1ST NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT

Deborah Lipman

2ND NATIONAL VICE PRESIDENT Mark Weingartner, ASC

NATIONAL SECRETARY-TREASURER Stephen Wong

NATIONAL ASSISTANT SECRETARY-TREASURER

Selene Preston

NATIONAL SERGEANT-AT-ARMS Betsy Peoples

NATIONAL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Alex Tonisson

ADVERTISING POLICY: Readers should not assume that any products or services advertised in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine are endorsed by the International Cinematographers Guild. Although the Editorial staff adheres to standard industry practices in requiring advertisers to be “truthful and forthright,” there has been no extensive screening process by either International Cinematographers Guild Magazine or the International Cinematographers Guild.

EDITORIAL POLICY: The International Cinematographers Guild neither implicitly nor explicitly endorses opinions or political statements expressed in International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. ICG Magazine considers unsolicited material via email only, provided all submissions are within current Contributor Guideline standards. All published material is subject to editing for length, style and content, with inclusion at the discretion of the Executive Editor and Art Director. Local 600, International Cinematographers Guild, retains all ancillary and expressed rights of content and photos published in ICG Magazine and icgmagazine.com, subject to any negotiated prior arrangement. ICG Magazine regrets that it cannot publish letters to the editor.

ICG (ISSN 1527-6007)

Ten issues published annually by The International Cinematographers Guild 7755 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, CA, 90046, U.S.A. Periodical postage paid at Los Angeles, California. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ICG 7755 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, California 90046

Copyright 2025, by Local 600, International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States and Canada. Entered as Periodical matter, September 30, 1930, at the Post Office at Los Angeles, California, under the act of March 3, 1879. Subscriptions: $88.00 of each International Cinematographers Guild member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to International Cinematographers Guild Magazine. Non-members may purchase an annual subscription for $48.00 (U.S.), $82.00 (Foreign and Canada) surface mail and $117.00 air mail per year. Single Copy: $4.95

The International Cinematographers Guild Magazine has been published monthly since 1929. International Cinematographers Guild Magazine is a registered trademark. www.icgmagazine.com www.icg600.com

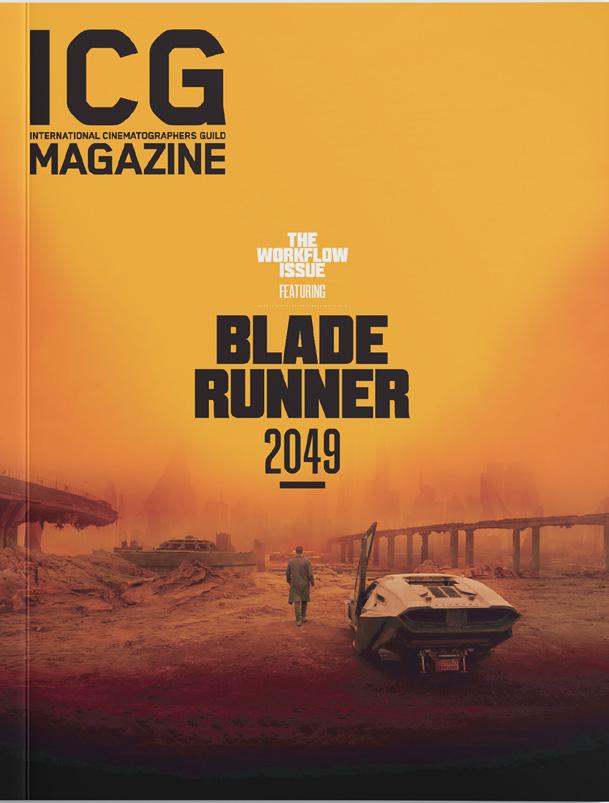

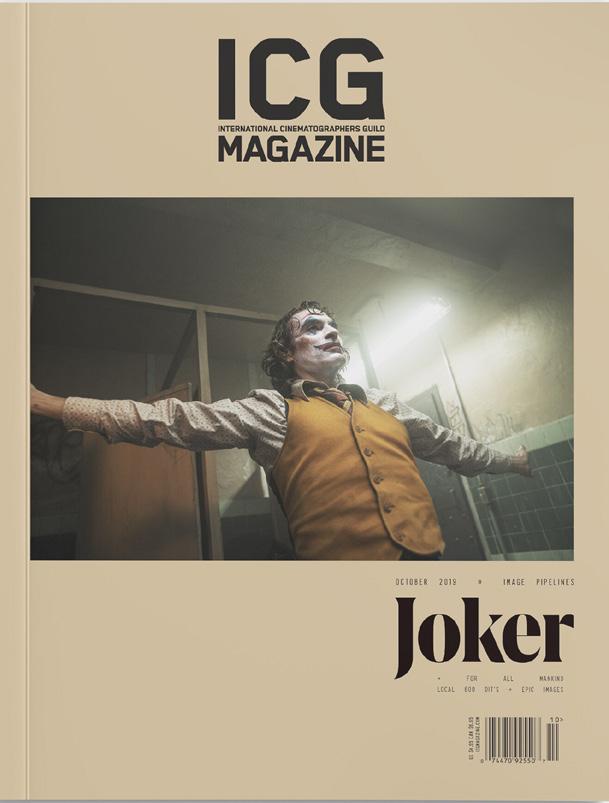

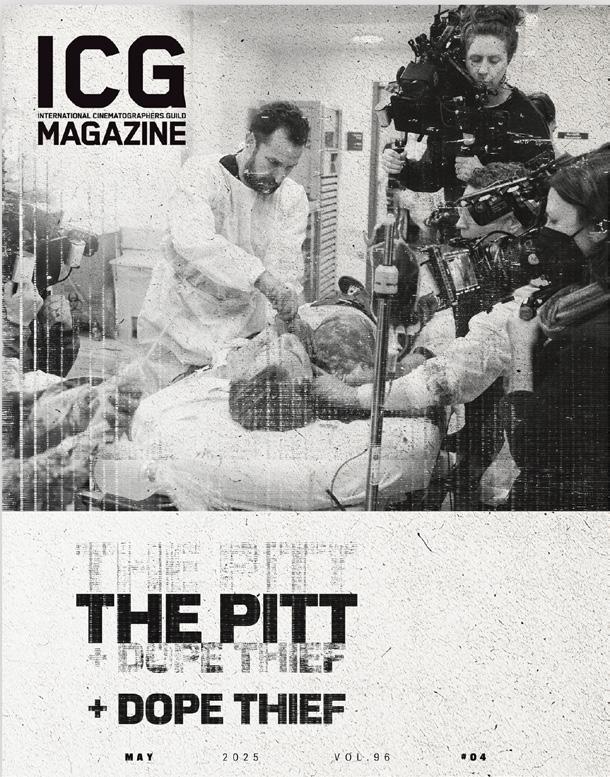

Welcome to ICG Magazine’s third (of four) print issues for 2025. This month’s theme, “Image Pipelines,” points out the evolving relationship between on-set capture and postproduction, which, these days, is not so much a linear as a lateral process. And it’s one that has multiple departments – camera, VFX, editorial, etc. – all roaring together toward the finish line. And the racecar metaphor fits my October cover piece on this summer’s crowd-pleasing blockbuster F1, one of the most satisfying stories I’ve written in my 17 years with ICG Magazine (page 30). Why? Because it perfectly illustrates how Local 600 members are the most innovative filmmakers on the planet.

Speaking with four principals from F1’s creative team – Director Joe Kosinski; Director of Photography Claudio Miranda, ASC; A-Camera Operator Lukasz Bielan; and 1st AC Dan Ming –I was awed at the lengths these technicians/ artists will go to fulfill an on-screen vision. Not that it came as a surprise – all of them (sans Bielan) accomplished a similar feat on Top Gun: Maverick [ICG Magazine June/July 2022] when they convinced the U.S. Navy that, yes, it is possible to put six Sony VENICE cameras inside an F18 fighter jet. But as both Ming and Miranda told me, “Top Gun was easier than F1 because once the plane was airborne, we had no control over the cameras. The film, essentially, shot itself.”

Kosinski had a much higher-level ask for F1

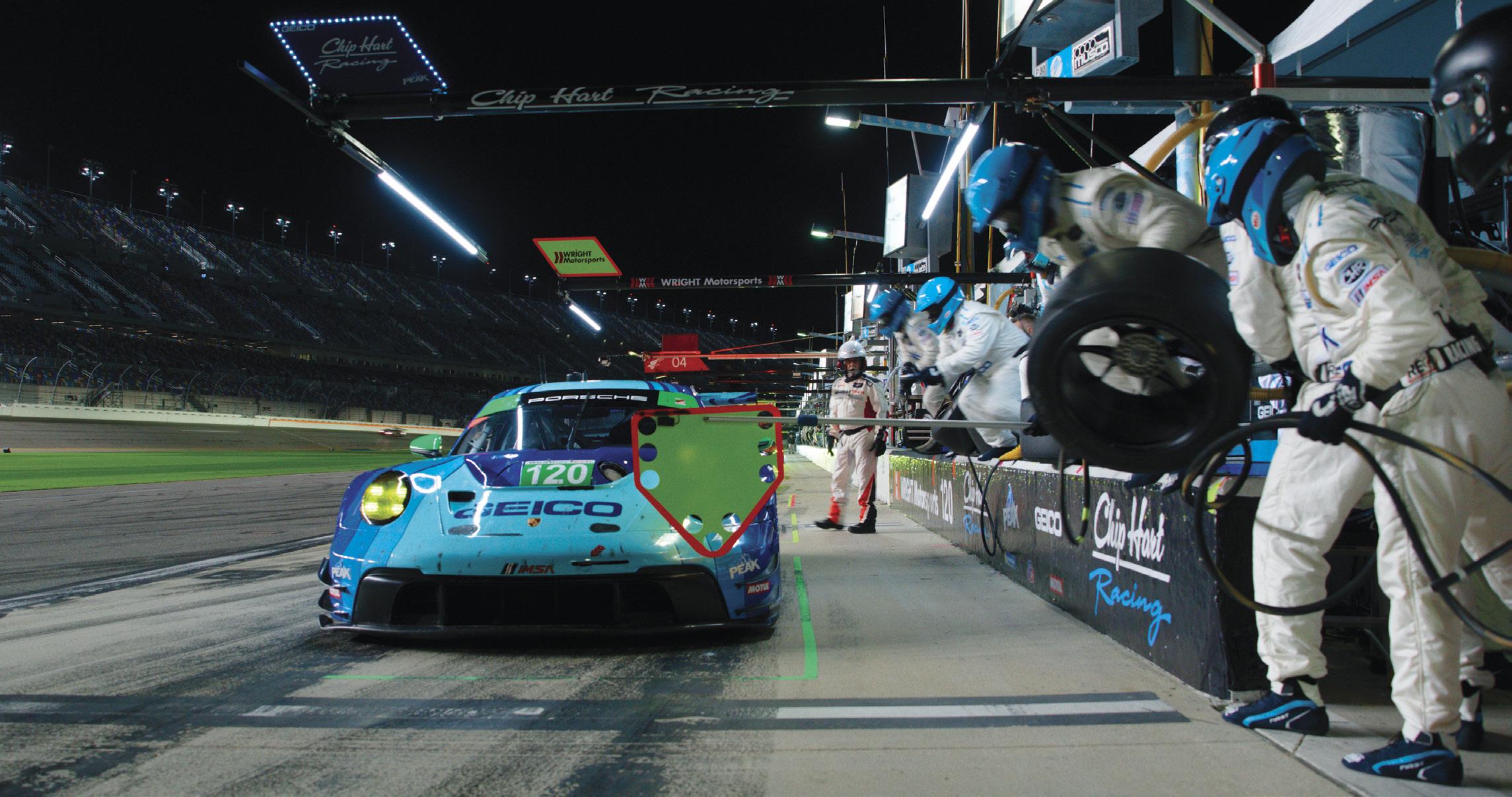

Not only would they need to design a camera system that resulted in 19 different mounting positions on a purpose-built Mercedes/AMG F2 race car, but many of those cameras had to pan and be focusable on nine different racetracks around the globe (F1 enjoyed a full Local 600 camera team at the Las Vegas and Daytona tracks, as well as for specialty footage shot in Pismo Beach, CA). Miranda collaborated with Apple’s designers for a 4K POV wing camera that was mounted on the F1 teams’ race cars, and his close relationship with Sony’s engineers resulted in what the team called “a sensor on a stick” fullframe, IMAX-quality camera.

Going off Miranda’s CAD drawings, Panavision designed an ultra-light pan head for the Sony

cameras, with the electronic guts of the system stowed in the belly of the race car, and just a 9-foot cable rising up to meet the cameras. Working with RF Film, Ming and the team helped to install a robust wireless mesh system to relay the video signal from the cars – which were travelling in excess of 175 mph – back to “Mission Control,” where four operators and four AC’s (per car) listened intently to Kosinski – on a comm with actors/drivers Brad Pitt and Damson Idris – calling out camera moves.

If you’re not impressed yet, know that the F1 team had to individually tune every camera at every track (due to varying conditions and camera placement) using different thicknesses of Sorbothane and adjusting tire pressure to maintain the rock-solid, cinematic image Kosinski wanted. As the director told me, “We didn’t want to compromise the on-track footage and go with a documentary look. It needed to feel like the rest of the film, which meant proper coverage and imagery designed for the IMAX screens.”

A similarly innovative spirit motivated the team behind A Big Bold Beautiful Journey (page 66). Led by a visionary director, Kogonada, whose indie feature After Yang was the highlight of the (online) 2022 Sundance Film Festival, this genredefying movie dares (like F1) to convey its many visual surprises in-camera. Shot by Benjamin Loeb, FNF, around L.A.-area locations, the set-to-post connection was deep, with Loeb working closely (up front and in the DI) with Harbor Pictures colorist Damien Vandercruyssen. As Vandercruyssen told ICG writer Kevin Martin, “They approached me with a wide range of references, including still photography by William Eggleston, Shinkai’s anime, and designs by Charles and Ray Eames. We were looking to create a bespoke look that mixed all these references into one big, bold beautiful journey.”

The Guild camera team also faced challenges not typical for L.A.-based productions. As Loeb adds, “Kogonada suggested we make it rain for the first 30 pages of the script. That idea also came out of the anime, seeing sun and rain together in a way we called ‘liquid sunshine.’ The look was abstract and unique and had elements that I loved. Normally when it rains, it gets cloudy, but our rain had that strange difference.”

Strangely different, boldly innovative, fearlessly explorative – however one describes the road the union filmmakers profiled in this issue traveled, the destination remains the same: stunning cinema meant for the big screen.

David Geffner Executive Editor

Email: david@icgmagazine.com

“I can’t put into words how unique, epic and creatively nourishing F1 was. It’s the type of project anyone interested in working in film dreams about being a part of. Every day I was amazed by the technicians around me. From the A+ camera crew to the RF crew to the drivers. Every single person brought their A-game every day of the nearly 18month shoot. Nothing short of that would’ve yielded the extraordinary results that became F1. I am proud to have been a small part of it. Truly a once-in-alifetime experience.”

In the Red Zone, Stop Motion “As still photographers, we don’t set the stage – we respond to it. What struck me [shooting stills for HIM in New Mexico] was watching Kira [Kelly] measure shots and direct the crew in such a vast, unforgiving environment. There’s a rhythm to filmmaking even in the middle of nowhere: grips maneuvering gear over rocky ground, the camera team keeping everything steady against the wind and actors waiting for their cue. My role was simply to watch, anticipate and capture how the DP’s precision translated into this wide, unpredictable space.”

COMPILED BY MARGOT LESTER

PRICE VARIES ARRI.COM

“The standout feature to me with the ALEXA 35 Xtreme is the Open Gate 4.6K at 120 fps,” describes Director of Photography Charles Bergquist, who was involved in the camera’s testing. “With deliverables expanding, being able to use the full width and height of the ALEXA 35 sensor at 120 frames per second, with the same quality that we’re accustomed to with the original ALEXA 35, this new system removes all previous frame rate constraints. I can bring one camera body on a project that can shoot 24 frames per second, then reach all the way up to 240 frames per second or further with the same dynamic range and color science as the original ALEXA 35, foregoing the need, in most situations, for a specialty camera. Knowing how colors and dynamic range are going to respond with high frame rates gives every project a unified look.” Users can easily toggle between overdrive off or switch it on to achieve significantly higher frame rates with the original ALEXA 35’s color science and only a slight tradeoff in dynamic range.

BASE PRICE $1,850 BLACK-MULE.COM

Move thousands of pounds of gear with a single finger! That’s the selling point for BLACK MULE’s electric power driving system that can be attached to most production tracks, fast and without drilling into your carts. The rig has tire packages for every situation – all-terrain, sand or studio. The idea came to Local 600 DIT Eduardo Eguia [ICG Magazine August 2024] while he was working on The Mandalorian. “We were constantly shooting on a backlot that had all kinds of terrain,” Eguia recounts. “It was challenging to push carts around the location, so I started thinking of systems that could be added to the carts we already had. By using a powered differential motor, our systems provide extremely smooth operation, capable of doing very tight turns. Besides making production life easier, we also want to make your work safer. That’s why our systems also include a slow-speed mode, lights and an auto-brake.”

$32,995 BLACKMAGICDESIGN.COM

When Metaverse Stage Director of Photography Hugh Hou needed to capture continuous footage to put viewers in the heart of a two-hour live professional sporting event, he selected the Blackmagic Design URSA Cine Immersive system. Its dual 8K sensors deliver 8160 × 7200 resolution per eye with pixel-level synchronization and 16 stops of dynamic range. It comes with a custom lens system and 8 TB of removable high-performance media, and high-speed 10G Ethernet and Wi-Fi for fast media upload and syncing. “In live sports, there are no doovers,” Hou states, “and the camera was reliable and steady, delivering footage in Apple Vision Pro’s highest spec of 8K per eye, 90-fps HDR, with Apple Spatial Audio Format. We’re proud to have pioneered this format, demonstrating that a headset experience can capture the pace, emotion and nuance of an entire game, not just the highlight reel. Paired with innovative crew practices and a bit of ingenuity, it enables immersive storytellers like us to aim higher than ever.”

$11,495

FLANDERSSCIENTIFIC.COM

These newly released displays give DP’s, DIT’s, editors and colorists reduced display-matching challenges. As FSI Sales Manager Adam Patterson describes, “Until now, on-set HDR monitoring has been difficult, impractical and cost-prohibitive – but the XMP270 marks a turning point, delivering true UHD HDR mastering capabilities in a compact, affordable package.” The display is built on the same panel technology as FSI’s HPA Award-Winning 55-inch XMP550. The monitor’s 1,000 peak luminance, 1.5 million:1 contrast ratio and 10-bit QD-OLED panel provide pure RGB additive white. It also meets Dolby Vision mastering specs. The XMP270 comes pre-calibrated from the factory and offers accurate volumetric Auto Calibration for users to recalibrate over time. “Its smaller, lighter, and fanless design [including an aluminum chassis that helps conduct heat away from the panel] makes it ideal for field use,” Patterson adds, “while features like Quad-View, four 12G-SDI inputs, look LUT support and onboard volumetric AutoCal streamline production workflows without sacrificing performance or precision.”

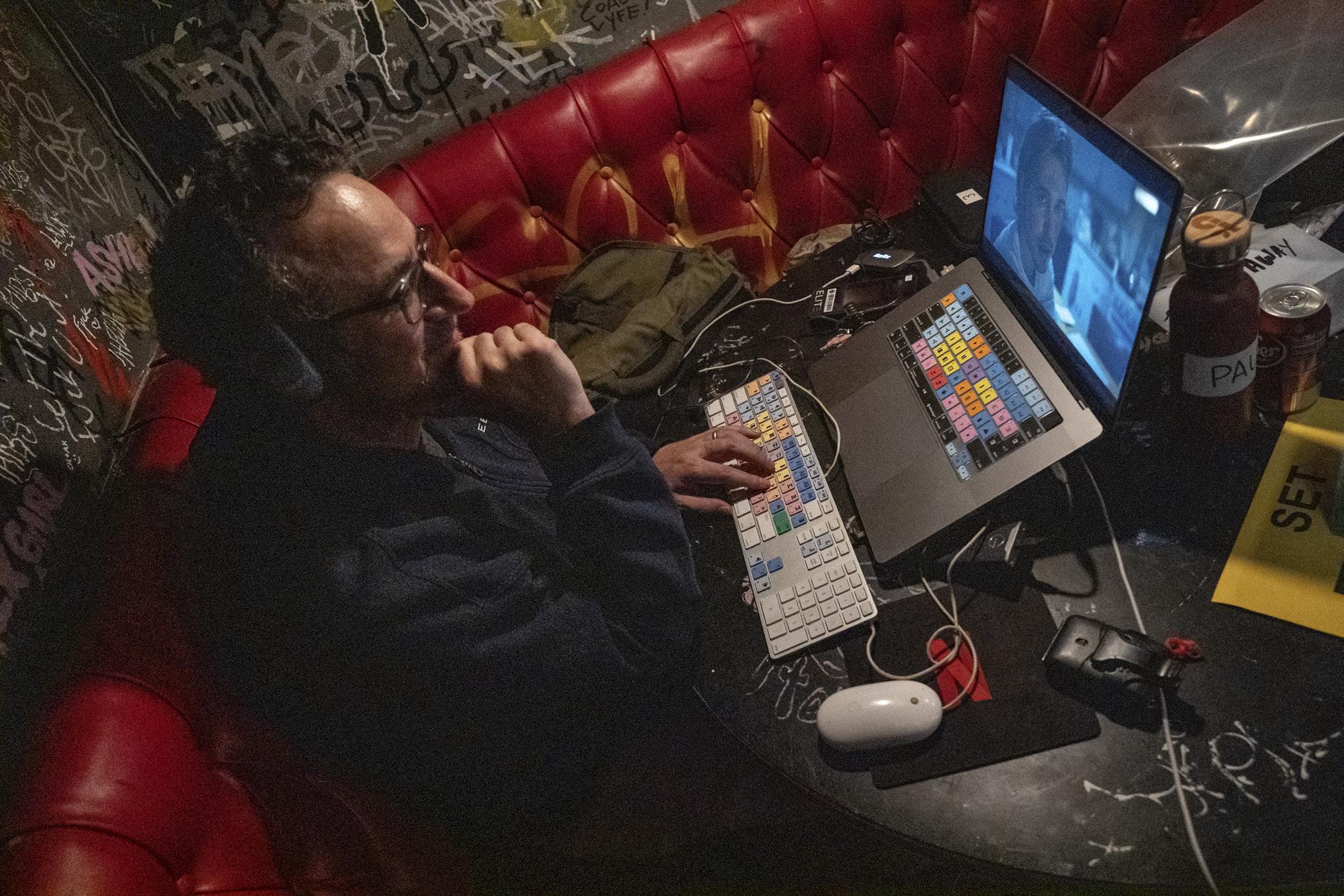

EDITOR

BY KEVIN H. MARTIN

PHOTO BY NIKO TAVERNISE / SONY PICTURES

Nearly all of the work Local 700 Editor Andrew Weisblum, ACE, has done has been with indie-minded directors. Most notably, it reflects his recurring partnership with directors with a strong point-of-view – i.e., Wes Anderson and Darren Aronofsky – as well some television and features for Zal Batmanglij (The OA and The East, both written by and starring Brit Marling). Weisblum has been twice Oscarnominated, for Aronofsky’s Black Swan and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Tick, Tick … BOOM. With Aronofsky’s newest film, Caught Stealing (ICG

Magazine September 2025), now in theaters, Weisblum reflected on the nature of their recent collaboration as well as how trust and experience fueled their long-term relationship. He explains how this more mainstream studiobacked film impacted his end of the filmmaking process.

ICG Magazine: Caught Stealing is a real departure for Aronofsky and his regular collaborators, like you and Matty Libatique. What was your approach when digging into

the footage? Andrew Weisblum: Darren and I both wanted to avoid any feeling of melodrama. Tonally, there was room to dig deeper into the emotions, especially with all the dark things happening, but for this movie, we wanted room for the comedy to play, and also didn’t want the tone to vacillate too far.

Matty and Darren both talked about the importance of the period aspect of the story and maintaining the integrity of the many locations they used. While it absolutely sits

At about 70% smaller than the current system, the VENICE Extension System Mini offers unprecedented mobility without sacrificing image quality.

Equipped with the VENICE 2 full-frame sensor, the VENICE Extension System Mini enables you to extend the sensor block from the camera body up to 12 meters awayfor ultimate creative freedom.

“WHILE HE AND MATTY MOSTLY SHOOT SINGLE CAMERA, DARREN’S NEVER BEEN WHOLLY AVERSE TO A MULTI-CAM APPROACH...FROM AN ASSEMBLY PERSPECTIVE, IT WAS DIFFERENT BECAUSE EXCEPT FOR NOAH, WE HADN’T DONE A LOT OF ACTION.”

in the After Hours vein of dark comedy, we still thought it very important to get our memories of the period in which it is set [late 1990s New York], conveying specific detail to those who weren’t there or old enough to remember. For me that was principally about getting periodaccurate music in there; and since there’s so much multi-culturalism in the movie, we wanted those communities to have their unique musical voices represented. One important aspect for us was getting real newscasters instead of actors to do our news reports, because those voices were so distinctive. Everybody in their cars always listened to 1010 WINS [radio station] for their traffic reports and news. Since we had a TV on, we thought about it and realized what everybody watched back then was The Jerry Springer Show, and we included a clip from that.

What about the large amount of action/ violence in this film relative to Aronofsky’s other projects? There is always license for action in movies, but we were very careful not to make any of the fights come off like superheroes or what you see in John Wick There’s nothing wrong with that particular kind of choreography, but if your protagonist isn’t trained in combat, he isn’t going to be working by reflex in dealing with dangerous people. We looked at Marathon Man and especially Three Days of the Condor, which has a fight with an assassin dressed as a mailman in the apartment. The latter is actually a bit more choreographed than we remembered, but watching that, it was still scary seeing this killer coming after someone with no training.

The number and size of action beats also meant employing a slew of cameras for certain major stunt moments. How did that factor into your editing choices? While he and Matty mostly shoot single camera, Darren’s never been wholly averse to a multi-cam approach. On this film, it was a logical and practical necessity. For me, from an assembly perspective, it was different because except for Noah, we hadn’t done a lot of action. The other thing that I’m able to do now is to edit remotely using QTAKE server

while they’re shooting, so I could be working on already-shot scenes in my cutting room while simultaneously observing whatever’s happening on the set. I can also communicate via text with Darren, Matty or our Script Supervisor Alexandra Torterotot, while they are rolling, about shots that may be needed or any issues that come up, to make sure all our bases are covered. I would get QTAKE feed or files as it happened, whether I was on location or in the cutting room, so I could essentially cut the tap as he shot. Often, Darren will ask me to slap something as a test in the middle of the shoot to make sure we have what we need for a specific moment, and I can immediately give him feedback and discuss with him while they are still on that set or location. Given our tight schedule, that was an efficient way to work, knowing we had what was needed before going on to the next location. Ultimately it changed our typical assembly process because things got done so quickly; in many scenes, there only had to be limited massaging done after the initial work.

Early in your partnership, Aronofsky would insist on reviewing the dailies prior to any assembly work, but that changed with time, correct? Darren knows I will thoroughly mine all footage – I provide multiple versions on everything before I show it to him. That’s because I watch the shooting and know what he is after, instinctively. I take the position that I care deeply about making the film as good as it can be. He always values my input and even seeks it out, but ultimately it is his film and he makes the decisions. I don’t have any qualms about sticking with his call, in part because I never feel that I haven’t been heard. I provide him with options and offer pros and cons. It’s rare we dig into performance issues, but if it happens when we’re looking at a full cut, we can talk it out and he then leaves me to resolve that on my own. There’s that distance, so that when I show it to him, he can be objective. There’s not a lot of revisiting – at least there wasn’t on Caught Stealing

How have tech developments impacted your collaboration? Since I cut The Wrestler, I would

say that we’re able to use visual effects much more frequently to address all sorts of editorial issues that help improve the film in terms of pacing or storytelling details or whatever manipulations may be required. Often they are completely invisible. It’s just become more affordable and expected as a regular part of our toolset. And Matty clearly understands the ways these tools can help us and in determining methodology for shooting – it comes up quite a lot. We have about 900 VFX shots in Caught Stealing, but I don’t think most viewers would ever know this … at least I hope not!

Your workflow changes when working with a director like Wes Anderson. Can you point out those differences? Wes does an animatic for most, if not all, of the film prior to shooting. So, he gives me his vision for the film and we work that version first. After that, he is completely open to whatever other ideas I have or experiments I think are worth considering, assuming they’re not in contradiction to what we’ve already done. If I do work up my ideas on the side, which Wes expects, it might not be exactly what he wants, but it might still help in getting us to what he wants. I sometimes also volunteer these ideas earlier in the process just to see if he wants to explore or for me to keep working from his original concept.

Other filmmakers you reteamed with include Britt Marling and Zal Batmanglij, going from a feature to some key Season 2 episodes of The OA. What was it like jumping into such an unusual series in mid-stream? Your second episode was the one that fans describe as living practically in David Lynch-land, with your star appearing publicly on stage with a rather grabby telepathic octopus! I had known Bit and Zal for a while and was familiar with the first season of the show, so I wasn’t coming in blind per se. I would say that we were conscious of making things clear enough to stand on their own for people who were not familiar with the show–and it was also very much its own story. For the octopus, I remember trying to stay with Nina’s [played by Marling] POV as much as possible and to not reveal the creature too soon!”

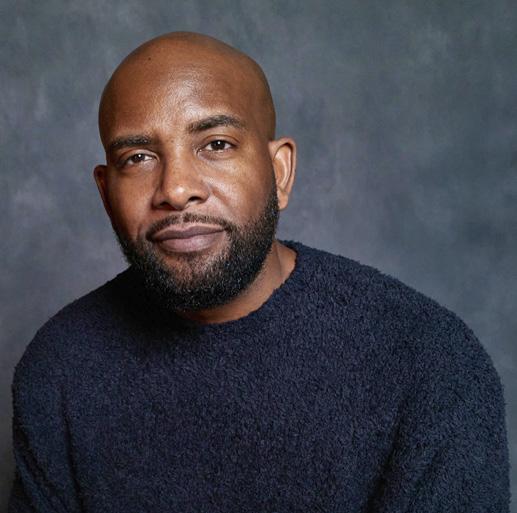

DIRECTOR/CO-WRITER | HIM

BY MARGOT LESTER

PHOTOS BY PARRISH LEWIS/UNIVERSAL PICTURES

Sometimes things just fall into place. Back in 2017, after his “really tiny micro-budget” film, Kicks, had debuted, Writer/Director Justin Tipping met Jordan Peele, who had just won an Oscar for Get Out and kicked off his unique company, Monkeypaw Productions.

“[Peele] was sitting down with filmmakers generally, and because he had seen my movie – which was shocking to me at the time – he wanted to meet me,” Tipping remembers, still sounding surprised. “This is someone I looked up to. Hearing him admire my work and be curious the first time I met him – it was a pretty surreal experience.”

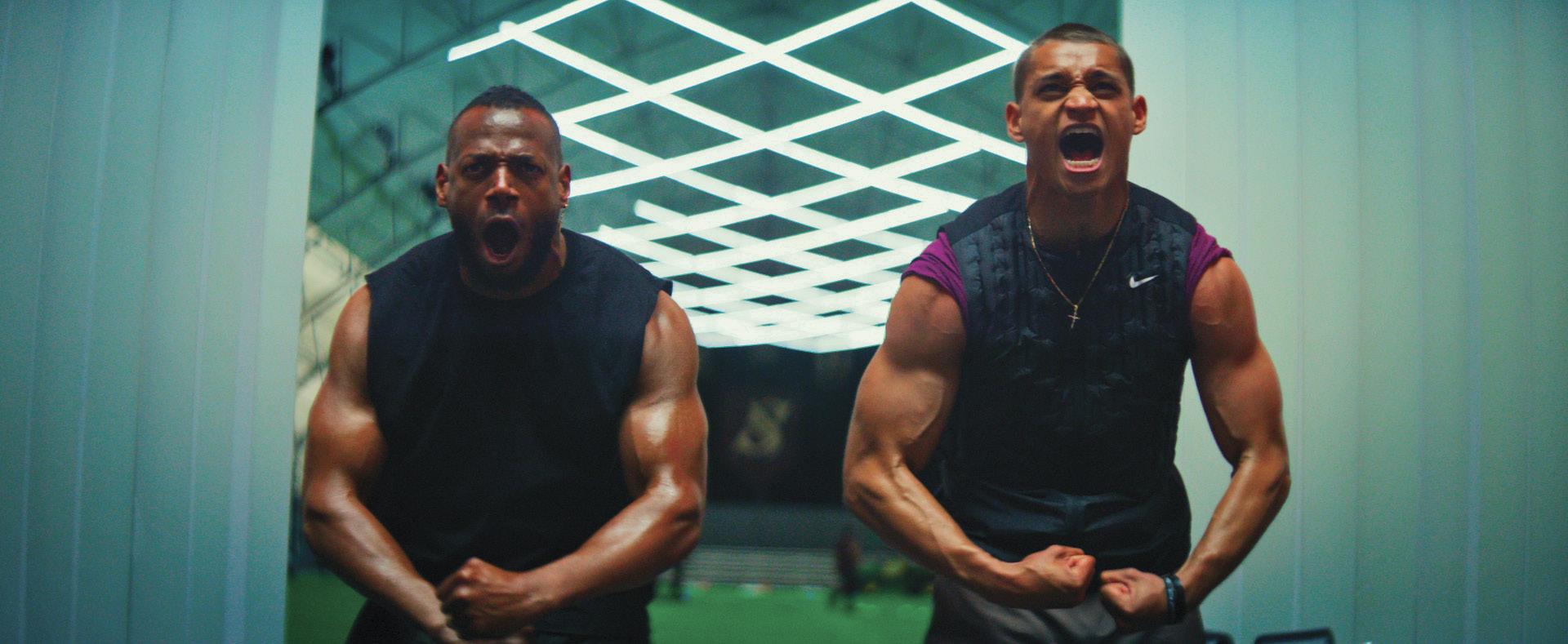

It took a while for the right project to come around, and during that time Tipping moved into directing television, including Lena Waithe’s The Chi, Justin Simien’s Dear White People and Etan Frankel’s miniseries Joe vs. Carole. When he got the script for Monkeypaw’s sports-horror feature, HIM, he jumped at the chance to helm the project. The story revolves around two oncein-a-generation athletes (one retired from the playing field, the other just coming into his own). Through them, HIM explores the psychology of what it takes to be the greatest of all time.

“They wanted a writer/director to make it their own,” recalls Tipping, himself a former athlete. (He stepped away from sports in college to pursue film, though the Bay Area native is still a serious fan.) And HIM brought Tipping’s own two worlds together in such a compelling way that he couldn’t resist. “It was like a feeling. I could see it. I came in hot. ‘This is what I would do, exactly how I would do it. It’s pretty crazy. What do you think?’ Well, Monkeypaw likes crazy, so...”

The film, Tipping’s feature debut, reunited him with Local 600 A-Camera Operator Scott Dropkin (and introduced him to ICG Director of Photography Kira Kelly, ASC). The two last worked together on the director’s first-ever episode of television, The Chi’s “Ease on Down the Road.”

“Now I’m on my first feature, and Scott Dropkin’s right there again,” Tipping smiles. “It was a comforting feeling to know that’s who’s driving the main camera. Having worked with Scott already, there’s a level of quick communication without needing to say anything.”

ICG freelancer Margot Lester visited with Tipping to talk about how he approached his feature film debut, its genre mashup and the ground-breaking technology that made it possible.

Jordan Peele redefined what the modern horror-thriller combo movie could be – all on a modest budget. How did you work within

that approach? We had a capped budget and it did inform a lot of the choices. There was no wriggle room, and it was a very massive puzzle to put together. But I come from the film school and the film school/micro-budget feature world, so I was accustomed to, “This is the sandbox. Here are the toys. Figure it out.” We didn’t have the money to make, in a classical sense, a larger-than-life, let’sjust-go-crazy-and-get-this-this-and-this film within our 30-day schedule. But Jordan is a fan of doing things in-camera as much as possible and not relying heavily on visual effects and I totally agree, so there was synergy there.

This film extends past Monkeypaw’s horrorthriller lane to add in sports, sci-fi and high tech. How did you blend all those genres? It was a fine needle to thread that was very, very difficult! [Laughs.] This is a Friday Night Lights -like classic sports tale and then at some point, we’re going to pull the rug out from under everybody, and it will evolve or devolve, depending on your point of view, into something else. You don’t have to do much for [the] body horror, so I wanted to lean into psychological horror, too. Films like Jacob’s Ladder and The Shining , which are these kinds of descent-into-madness archetypes. There’s a Venn diagram that we approach in the script and on set with every scene, of like, is this serving that itch of the promise of horror and is it serving the promise of sports?

And is it doing it at the same time? That was a pretty amazing ask to take on, and all departments at every level were all working towards that goal.

Monkeypaw projects all have a bigger message. What’s the subtext of HIM? What Jordan and his films also do best, which I think HIM does as well, is that anyone can see the movie and have fun. It’s still an exciting…shared experience. Then if you want to look deeper, there’s plenty to find! This film is more of a mirror. There’s nothing that we’re taking on that hasn’t already been addressed in the world of sports. My first film, Kicks, was about exploring toxic masculinity…commodity fetishism and how that drives us as young men. The maturation of that for me was what happens when the athlete becomes the commodity. How are they moved throughout the system and the institutions of sports at large?

How was it shooting in New Mexico with Kira Kelly, who’s shot there before? There are so many benefits to shooting in Albuquerque, where a lot of the tinsel and things are out of the way, and it’s more, “This is what we’re here to focus on.” It’s calm, quiet and kind of meditative out there. I guess that’s why they call it the Land of Enchantment! Kira Kelly is incredible – a savant, a painter with light. And my favorite part was that she’s the sweetest person ever at the same time. She knew what it would take to shoot there. She already

had her goggles for the sand and already had a rapport with a lot of the crew. That’s invaluable, just on a human level. Everyone was in sync. I mean, I don’t want to brag, but we came in on time, we came in under budget at the end of the day during principal. So a big shout-out to every crewmember who worked on this film.

What did you bring from directing episodic to this film? That’s a great question. Part of shooting a feature with this budget is knowing how to make each day, and that comes from TV. I can look at a scene or a day’s work five minutes before and just go, “This is what we’re doing.” Having that in the back pocket for when something does go wrong is a tremendous value-add because something goes wrong – constantly! And instead of going over [budget] because you’re fighting to save something that can no longer exist and trying to force it through, working in TV has given me a muscle where I could tell the same story or scene just by re-blocking or reapproaching it in real time without sacrificing any of the emotion or story beats. It’s mainly just another way to improvise.

So you’re a director who is very conscious of the budget? Definitely. I pride myself on not going over. I don’t think it’s necessary. I think that directors that come in and take pride, saying, “I shot 20 hours” – that’s an ancient way of thinking. You shouldn’t be

proud of that. You should be embarrassed that you can’t execute what you need to execute without killing your crew and not letting them go home to see their families. So, I’m putting that into the universe, hoping that we set a new standard.

It’s worth noting you made your days using a first-of-its-kind stereo-rig sporting an ALEXA 35 and a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) thermal camera. Oh, yes! I feel like everyone felt we were in middle school again and someone’s parent had brought in a camera. “Oh my God, let’s try to figure it out and make a movie!” It was very exciting.

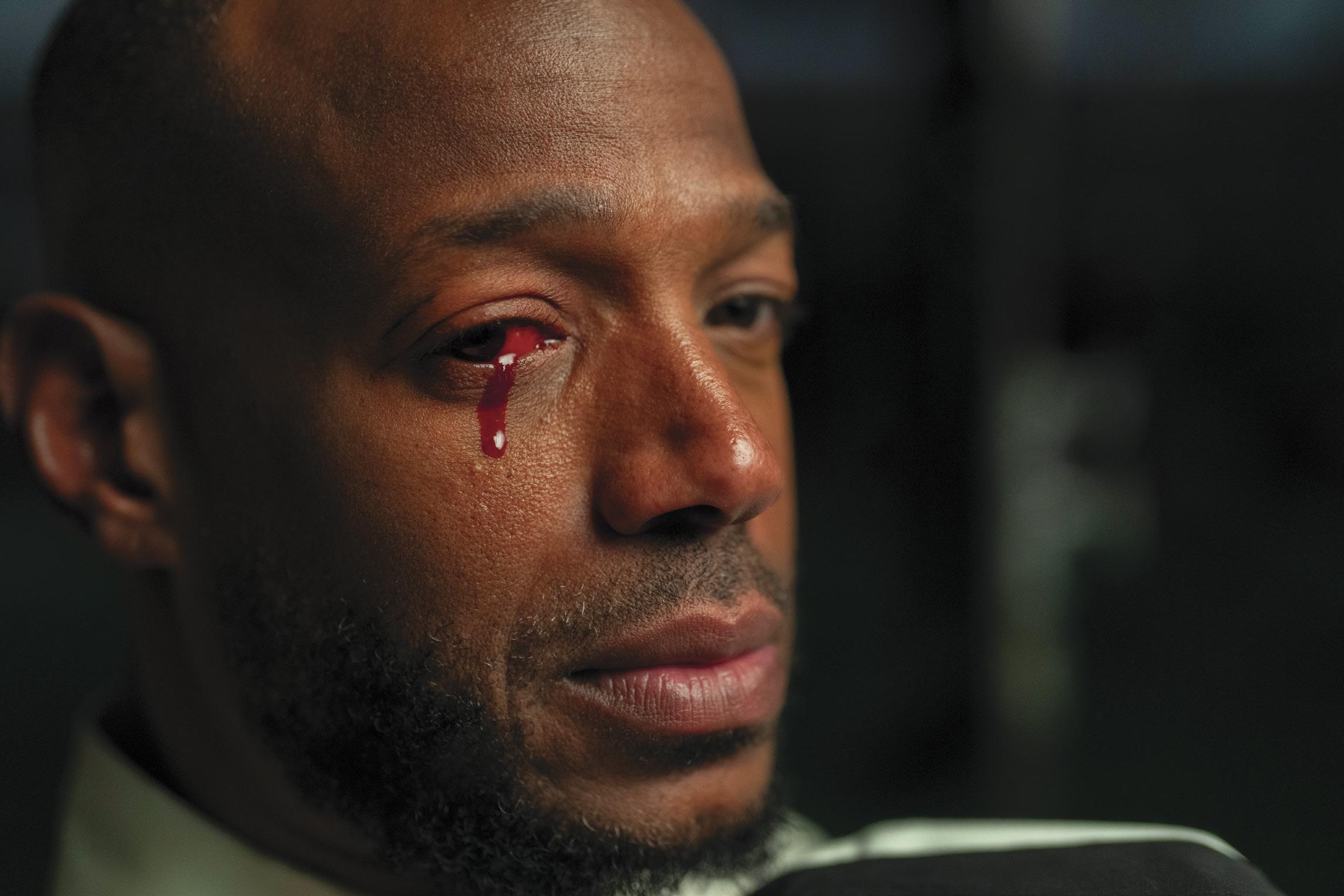

But the tech supported an important part of the narrative. Body horror is inherent in the DNA of sports, [but] most people just don’t get behind that curtain. They don’t see what these athletes actually go through week to week, just in terms of recovery, let alone obvious injuries. So how do you frame it, how do you lens it, and how do you show it? I wanted to show people that weren’t familiar with what physical collisions on a football field look and feel like. You don’t necessarily know anyone’s bleeding. There’s nothing to visually convey how much that hurts. But there’s so much – needles, pills, you name it – tears, tendons. I just kept going back to, What if we could look inside the body and see what neurons shut down, what muscles get shot off, how it’s actually affecting a player – to track our main character’s descent into

the horror [in a way] that was still tethered to football?

And that’s when Kira and [Producer] Ian Cooper suggested the FLIR? Yes. We [wanted to] go in and out of the arena footage and a kind of X-ray language without doing a hard cut, but a truly symbiotic synthesis, flickering in and out like an X-ray or a CAT scan. There was a lot of trial and error. Creativity is making mistakes. Art is knowing which ones to keep. We kept some mistakes and it worked!

Do you see yourself returning to episodics, continuing in indie features or maybe making the jump to large-budget studio fare if the opportunity presents itself? I have original ideas for both TV and film. If I return to TV, it will hopefully be for a show I’m creating, not necessarily episodic. Otherwise, film was my first love, and that will never change. I tend to generate stories that may be too risky for bigger budgets, but I do have them. Whether or not someone lets me make them at a specific price point is a different story. [Laughs.] With that said, I’m a blockbuster kid who watched Predator and Terminator 2: Judgment Day on a VHS tape over and over until Saturday morning X-Men came on… so, yes, if the opportunity and story made sense, I’d love to make a massive blockbuster. Either way, I know I won’t be playing it safe.

HOW CLAUDIO MIRANDA, ASC, AND HIS LOCAL 600 CAMERA TEAM PUSHED THE LIMITS OF IN-CAMERA CAPTURE FOR THIS YEAR’S SCORCHING RACING EPIC, F1 .

BY DAVID GEFFNER

SCREENGRABS COURTESY OF APPLE

Towards the end of my Zoom conversation with filmmaker Joe Kosinski, I joked that he and Claudio Miranda’s next feature had to be in the water. They had already put six cameras inside the cockpit of a U.S. Navy fighter jet for the 2022 Oscar-winning Top Gun:

Maverick, and they’d done it again on land for this year’s monster hit F1, building a remarkably ingenious pan-and-focusable camera system that mounted on a Mercedes-built race car travelling in excess of 180 miles per hour.

“THE MAIN THING I LEARNED FROM TOPGUN WAS THE BELIEF THAT IT WOULD FEEL MORE VISCERAL AND YOU WOULD FEEL MORE CONNECTED IF WE SHOT FOOTAGE IN AN F18, PRACTICALLY.”

DIRECTOR JOSEPH KOSINSKI

While Kosinski (not a water lover) modestly agreed that may be his next journey, it’s clear he and his core Local 600 camera unit – Director of Photography Miranda, 1st AC Dan Ming, and A-Camera Operator Lukasz Bielan – are filmmakers who will stop at nothing to create actiondriven cinema – in camera. In fact, when I asked whether he and Miranda ever considered capturing the racing footage in a Volume (given the current level of digital technology), he said one of the main things learned from Top Gun: Maverick , was that “if you go to the trouble to shoot it for real, with actors responding in the moment, the audience will know and will respond.”

Top Gun: Maverick was, in some ways, a proof of concept for even attempting F1 . But, as Miranda pointed out, “it was easier in many respects [than F1 ], as once the planes went up in the air with our cameras, that was it. We had no more control.”

The on-car system built from scratch for F1 was another matter entirely.

Kosinski wanted the cameras to withstand the intense g-force of Formula One speeds and be able to pan and focus anywhere – on track conditions all over the world (including rain and desert dust). Miranda needed them to be full frame (to accommodate an IMAX release) and knew their overall weight and size couldn’t impede hitting full track speed or block the driver’s vision.

With four cars (each with four cameras), Ming had to design and coordinate with

Panavision, RF Film, and the Mercedes AMG F1 team to build and house an entire camera system, complete with a wireless relay system (back to Video Village) that fit inside the massive F1 machine, already saturated with RF signals as it travels the global circuit to tech-heavy cities like Las Vegas and Dubai.

As for Bielan, not only did he (and B-Camera Operator Natasha Mullen) have to execute pans before they’d happen on the track (due to signal latency), he also had a narrow window of time (11 minutes) allotted by F1 during an actual race to cover scenes with actors on the track.

How this union team managed to find “clean air” (a racing term for when an F1 car encounters smooth airflow that maximizes downforce and grip on the track) and create some of the most visceral and cinematic racing footage ever put on screen is a special story – one that reveals much about their approach to filmmaking: when all improbable outcomes fail, you’re left with the impossible to pull you through.

Were there lessons learned from Top Gun: Maverick that could be applied to F1 ? Director Joseph Kosinski: The main thing I learned from Top Gun was the belief that it would feel more visceral and you

would feel more connected if we shot footage in an F18, practically. But, I didn’t know if going to all the effort to shoot [fighter jets] for real would translate to the audience until the movie was released. So, I guess you could say Top Gun affirmed that even if you execute something technically perfect with VFX or on the Volume, because we can reproduce anything these days, there’s still this X-factor that the audience can tell when something is really happening. Part of that is the performance of the actor in that moment, because some of it is acting, but some of it isn’t. When Brad and Damson are driving, there’s a level of authenticity because they’re really trying to keep that car on the track. And while several hundred pounds of camera gear won’t change the performance of an F18 jet, every kilo we added to the race car would affect its handling and speed and work against our goal. In that sense, F1 was an entirely different challenge than what we faced with Top Gun

Director of Photography Claudio Miranda, ASC: Top Gun’s aerial footage was determined by fixed cameras and whatever the jets did in the air. But how do you capture F1 speeds safely and cinematically in camera? We looked at a bunch of racing footage that had been done with Biscuit Rigs, and while the exteriors were fast, the interiors felt like they were overly shaking the camera and undercranking. It just didn’t feel real, and that’s because those rigs only go a third the speed of a race car. A Biscuit

A-CAMERA OPERATOR LUKASZ BIELAN (L) DESCRIBES DIRECTOR JOE KOSINSKI (LOOKING THROUGH FINDER) AS “INCREDIBLY PRECISE AND SPECIFIC, WHILE STILL CREATING A REALLY FUN WORK ENVIRONMENT.”

Rig that can do 70 miles per hour on a straightaway and 20 miles per hour on the turns is way too big a gap to make up for what we wanted the audience to experience in F1 . As for doing it all on a Volume, of course I get the cost savings. But can you imagine if Top Gun had been done on a Volume? That would look awful!

1st AC Dan Ming: Top Gun was easier because after we were able to retrofit the jets with the six Sony VENICE cameras, the main work was to prepare the system to record and then just let it go. We couldn’t make any adjustments – iris, pan, focus or tilt –once the plane was up in the air. For F1 , Joe wanted all the cameras on the cars to be able to pan and focus, and for us to have control of them anywhere on the track. That was the rough bones of what he and Claudio needed, and then it eventually ended up with us having three to four cars on the track at the same time and three to four cameras on each car. Given all the weight and space restrictions, we had to build a system from scratch, with each rig approved for safety by the F1 and FIA [Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile], the governing body for the sport.

A-Camera Operator Lukasz Bielan: For me this movie was all about precision. Joe and Claudio are incredibly precise about what they do, and that started from day one with Claudio working with Sony to design the cameras, and with Mercedes as to where the rigs could be placed – precisely and safely – on the cars. Joe comes from the world of architecture, so he wants compositions that are very specific. On Oblivion, we called him “Mr. Nodal,” as you would need a level to confirm what his eye told him about the frame. He’d say, “Lukasz, I think we’re a tiny bit off…” [laughs]. And he was always right, usually by a millimeter! He and Claudio create an environment that is fun and welcoming and yet also very precise. Of course, when I saw that one of the fallback plans was to have the operator on a picture car, driving at track speed, and working the remote panhead [because the large distances of the F1 tracks would create signal latency], I was like, “okay, that’s a vomit machine waiting to happen.” [Laughs again] Thanks to Dan Ming, we never had to go that route.

Miranda: I’d also add that Top Gun pointed to the relationship you can have with a camera manufacturer and what can come of that. The Rialto basically came about because I kept pushing Sony to help us figure out a way to get six cameras up in the jet. I kept asking them, “Is this possible? Can we do this?” trying to keep the doors open between myself, Sony, and the engineers. And the Navy said, “There’s no way you’ll be able to get more than one camera in the plane.” F1 was the same. “There’s no way you’ll get four cameras on the car. Maybe one.” Top Gun showed that if you keep imagining different ways of doing something, you can shift what everyone thinks is possible.

FOR F1, JOE WANTED ALL THE CAMERAS ON THE CARS TO BE ABLE TO PAN AND FOCUS, AND FOR US TO HAVE CONTROL OF THEM ANYWHERE ON THE TRACK.”

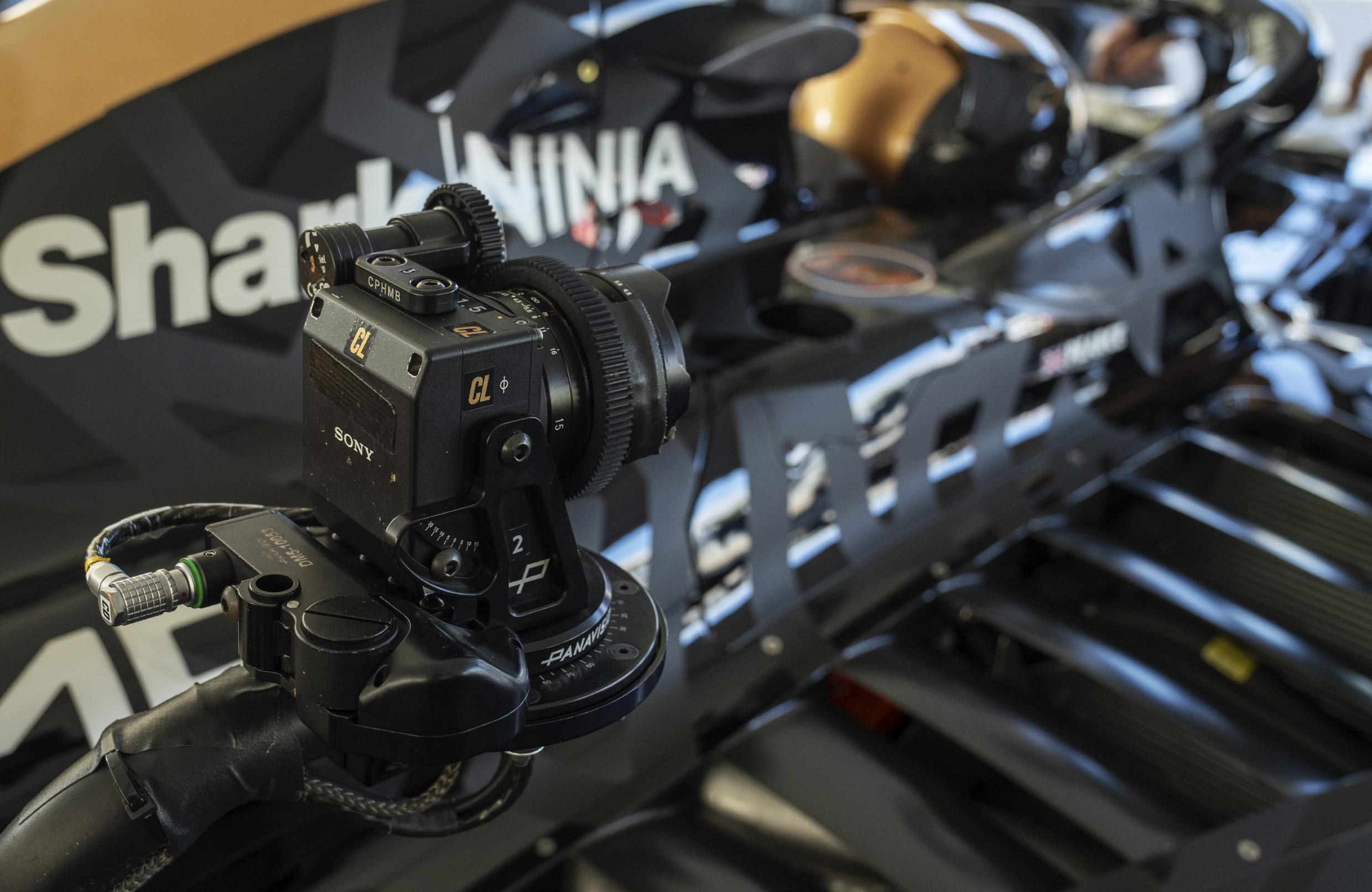

PER MIRANDA’S CAD DESIGNS, SONY ENGINEERS CREATED A “SENSOR ON A STICK,” A CUSTOM-BUILT 4K FULL-FRAME CAMERA USING THE FX6 SENSOR DESIGN AND MOUNTED TO A SLIMMED-DOWN PAN-HEAD CUSTOM BUILT BY PANAVISION.

“ALL THE NEWER LENSES WE LOOKED AT HAVE ELECTRONIC FOCUSING, AND WE LEARNED THAT WOULDN’T WORK DUE TO THE INTENSE VIBRATION.

WE HAD TO USE ALL MECHANICAL FOCUS AND MECHANICAL IRIS LENSES.”

Kosinski: The first challenge was how do we slim-down our Top Gun package to a fraction of its size without sacrificing any of that image quality because this needed to play on the biggest screens? The other challenge I gave to Claudio was that I want to move the camera. How do we do that? Because we couldn’t move the cameras on Top Gun. But, unlike Top Gun, we didn’t have to worry about tilt and roll – we only had to solve 180 degrees of panning. That allowed us to simplify the remote head.

Miranda: The drawings I sent to Sony’s engineers were basically of a sensor and a cable attached to it. No internal ND’s, no internal stabilization, just a fixed sensor, as the vibration from that many G’s would knock the block apart and it wouldn’t work. We tried a [Sony] FX3, but it was way too big. We landed on a custom-built camera using the FX6 sensor design, which, unlike the FX3, does not have internal stabilization. It’s 4K full frame, recording to [codec] XAVC. Sony created what we called “a sensor on a stick.” Of course we couldn’t put a stabilized head on it because, besides the added weight, the added size would impact the drivers’ visibility. We had to be very conscious about how many cameras we put in front of the driver. Even the smallest camera could block their view. We even built a little riser for the front-mounted camera so they could have a viewing gap under the rig. Weight was such a big concern – there was already grumbling a bit about having four cameras on the car – so we couldn’t use anything fancy like a motorized slider to have the camera move. The system had to have a light footprint, with all of the electronic guts stowed precisely in the belly of the vehicle.

Ming: We tested a bunch of small remote heads, and none of them had the torque or speed we needed because, of course, they weren’t meant to perform under violent G-force conditions. Since Claudio said all our moves would be linear, we could eliminate the tilt axis and concentrate solely on creating a panhead. I knew RF Films [an L.A.-based wireless solutions company staffed by Local 600 technicians] had already devised a way of stretching the range of the Preston’s focus and iris controls, converting it from serial to IP and putting it into a local network. There wasn’t enough time to engineer something new, so I told Claudio, “Let’s just build the panhead

around the Preston motor,” and he started sketching out ideas. The next conversation was about video. For that, Hornets Tech and Wireless Wizards in the U.K. provided a system with a 4K transmitter, via antenna and plug-in, done quad so that each transmitter could take one of the four cameras per car. Then we had to figure out how all of these systems could talk to each other. What’s the output? What’s the communications protocol?

Kosinski: Four cameras was kind of the most weight we wanted to carry, and also when Brad and Damson were driving, it was the most you’d ever want around them just in terms of limiting their field of view. We started with 15 different [camera] positions, and by the end we had found another four, so 19 different mounting spots on the car. The amount of cameras, lenses and setups we were going through every day was astonishing. Being first AC on this film…Dan Ming deserves a medal. He was amazing.

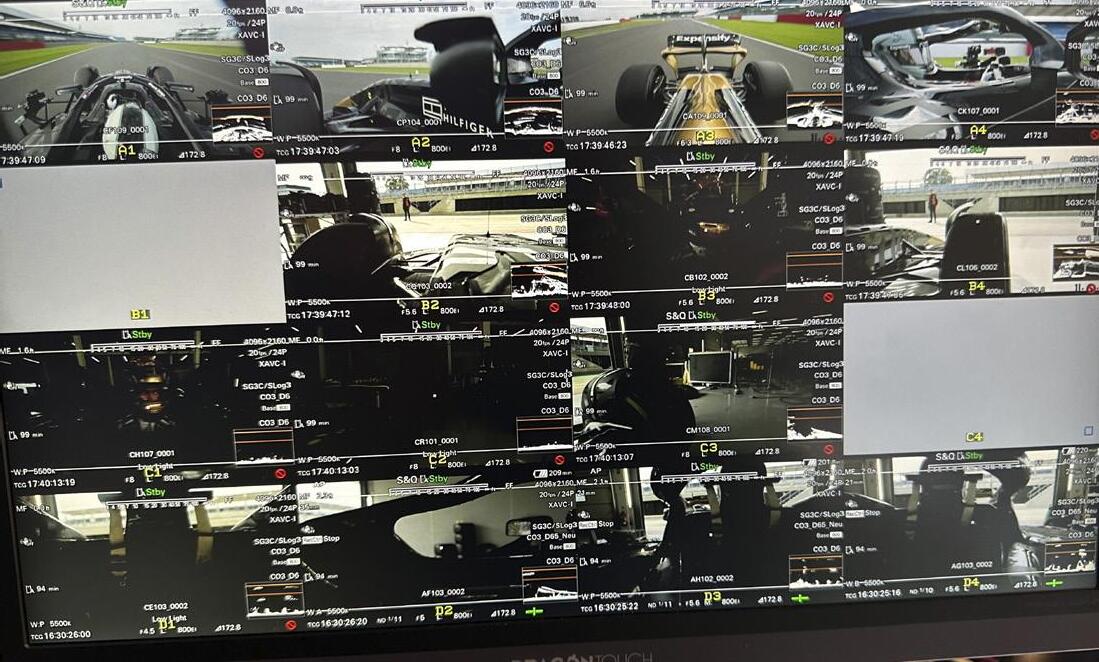

Ming: Sony built the cameras around the FR7 communications protocol, which is a full-frame [robotic] pan-tilt-zoom cinema line camera that uses VISCA – a lowbandwidth control protocol. That worked great because we didn’t want to open a web page to sixteen different cameras; we wanted a slimmer bandwidth. I got the Sony FR7 protocols over to RF Film, who helped create a local network in each car. All four cameras, the mesh radio for data, the video transmitter, the motor drivers and a voltage monitor were all hooked into a switch that became the local network in each car, and then each car had an Ethernet port built in on either side so we could just run up and plug in. Each car became a floating mesh point within the network, and RF Film had mesh nodes all around the track. It was this large, dynamic system where we could bounce the signal off various points on the track to get it back to us at mission control.

Bielan: Dan figured out that the Preston was the only device that could be active at the kinds of distances we had on these F1 tracks. So, for the operators, that means basically one-to-one – you turn the knob and the pan action goes. Almost zero lag. But it’s so fast, there’s no way to see it with your eyes. For the shots where the camera would whip-pan from the ground to the car – with the stunt driver going at speed – we tried to emulate the broadcast whip pans with a remote head and a fluid head, and nothing worked to get the precision Joe wanted. So, we took the panhead devices from the cars

and mounted them on sticks, very close to the track, and did those whip pans with the Preston, like the ones mounted on the cars.

Ming: We went to Panavision with the design Claudio had done for the panhead, which was very simple. We didn’t need stabilization, just a motor and gear. The components had to be light, because they wanted the cars to go fast, so we started milling out every piece of aluminum we could. Every 10 kilograms is a third of a second of lap time, which to most of us is like, “A third of a second! So what?” But Joe was like, “No, we have to stick to accurate lap speeds.” Our action vehicle team would use fuel to balance the vehicles based on what gear we had installed. We based everything off the 26-volt Anton Bauer on-board batteries because we had to ship them all over the world and keep our cells under 98-watt hours. Each side of the car had two cameras/recorders and two batteries, with the battery systems wired to each other –that way we could swap batteries and not lose power to the system and have to reboot.

Miranda: Way before we had determined the cameras, I talked with the engineers at Mercedes about how we were going to make this all happen. Their AMG F1 team built the cars we would use on the track. They sent me CAD drawings that I worked with to figure out camera angles, all of which had to be locked off. In a normal movie, you can move camera mounts all day. But to move a mount a few millimeters on these racing cars is a big deal! If I had an idea for a new camera position, I’d have to give F1 and Mercedes a two-to-three-month lead time to get it approved. The car they built for us was an F2, stretched by about 200-millimeters to look the same length as an F1. We had three Mecachromes [the 3.4-liter turbocharged engine used in an F2 car] and one electric car. All of the camera electronics – batteries, transmitters, recorders and networking – were housed in this gap under the radiator they call “the pan,” which could be lowered for us to load everything in and raised back up. All that came up from the car was this little 9-foot cable to the sensor, as envisioned in my original drawings for Sony. F1 and FIA had to approve everything for safety, including our camera mounts, which all had to shrink and crumble away from the driver in the

event of a crash. We did have a stunt driver wreck a car going at 180 miles per hour, and he was fine. Incredibly, the cameras never even stopped rolling.

Ming: All the newer lenses we looked at have electronic focusing, and we learned that anything that was electronic and floating wouldn’t work due to the intense vibration. We had to use all mechanical focus and mechanical iris lenses. We ended up with the same lens package as Top Gun – the wide Voigtländer E-mounts and the Zeiss Loxia E-mounts. We also added a few wide compact Voigtländer lenses for the camera angle facing the driver, which was mounted so close that when the driver turned the car, his knuckles would scrape the lens! Claudio also worked with Apple to have them redesign the wing camera they used on F1 cars during an actual race. That camera is low-resolution, compressed, and meant only for a POV shot behind the driver. Apple built all new cameras with the exact same weight, size and footprint [so it would not create any race advantages or disadvantages] to fit into the wing. They had 4K internal recording and ProRes RAW, and we would ingest that footage after the race, with F1 taking the video output for their purposes. The angle was either side of the driver’s helmet and seeing the oncoming track.

Kosinski: The first few tests we did at Willow Springs [about 80 miles north of Los Angeles] had way too much vibration. We trashed a bunch of lenses and basically vibrated a camera to death. It became this process of figuring out how to dampen all those G-forces and keep the footage cinematic. Changing tire pressure, accounting for surface conditions, using shock and vibration materials at each camera’s mounting point – it was this giant science experiment that continued throughout the entire movie, because what worked at one track might not work at another.

Ming: We used Sorbothane, a foamdampening material that you can bolt through, between the base of the head and the receiver on the car. The amount of Sorbothane had to be tuned for each track depending on different conditions and camera placement on the car – the further out from the center of the car, the more vibration you had. Some mounts were on the engine block itself, so vibration from the engine would transfer through. It wasn’t just the G-forces; the high-frequency

vibration put the cameras through severe punishment.

Kosinski: We also had issues with bugs hitting the lenses at some of the tracks, and we found out that coating the lenses with Rain-X made the bug kill look like raindrops. You never knew what was coming next, so this movie depended on a crew who were incredibly agile and resourceful. People like Dan Ming, who would print out new camera parts on a 3D printer at night in his hotel room and install them the next day. Every shot in this movie was earned with a lot of trial and error.

Kosinski: Lewis Hamilton [executive producer and holder of seven F1 titles] said to me at the beginning, “I drive the car every day, and when I watch the broadcast coverage, it doesn’t feel fast. Why is that?” He was trying to help us figure out how best to convey his experience inside the car. As we analyzed it, you can see that the [broadcast] operators are not trying to give the sensation of speed, they’re trying to clarify the race for the viewer. A shot they use a lot is down a straightaway, at the end of a long zoom, that slowly widens out as the cars come toward camera. They [the broadcast team] also run a very skinny shutter angle – 250th of a second. After embedding with them, I found out they do that – even on the pans – to ensure the commercial signage is always sharp. As for [narrative] films, the one that’s still the most impressive is Grand Prix. The fact that they went to the real tracks, shot during the real season, and mounted film cameras on cars makes it kind of timeless. The way [Director] Frankenheimer used wide-angle lenses was a paradigm of sorts for what we wanted to reach and go beyond with all the tools we have today.

Bielan: Operating on this film was like a live sporting event, as Joe would be on the comm with Brad, waiting for a specific line or a specific action coming up on the track, and then call out the pan at the precise moment it had to happen. In a regular film you block and rehearse with the actors to figure out the camera movement on the action you’ve designed. But all of our camera moves were based on the actors’ dialogue and the positioning of the cars as they were driving in the moment. It was interesting for some

of the pans, especially on a turn, as the latency at distance [created by a buffering system RF Film installed] meant you had to make the pan before you could see the action on the monitor; otherwise, you’re late. The AC’s watched the operators, pulling focus when they made the pan, for the same reason.

Miranda: The football-game analogy does fit, as we couldn’t do all that much on-the-fly, other than change ISO’s. But I did have the chance to account for exposure because the cars would do four laps and then come in for a pit stop. So, if there was an issue, we could try it again [laughs], very quickly. These cameras are not Sony VENICEs, shooting full RAW, so ISO was definitely something I could play with. The F1 broadcast team was impressive and so generous. They have this massive command center connected to their hub in London, with fiber carrying coverage all around the world. So, to let us integrate and embed was huge. Many times when we were on the track, they would help us cover with their cameras. They even stretched their shutter so the coverage was more filmic. All the sponsor signage had to read, so there was sort of a breaking point they could go to stretching the shutter – and not go past.

Ming: We had a separate team whose job was to collect the broadcast footage before it was compressed and retransferred. We had our own setup in the broadcast tent, and Joe would ask the broadcast director, before each race, for shots that would be great for us to have. They would add those to their broadcast plan, and that would be piped to our system so that our team could capture that live race footage. We got assigned slots during the F1 race weekend of events to run our cars so that we could shoot at speed with the crowds and the signage; Joe would try to get as many shots in as we could with the actors in those designated slots. We also had a camera array on a car that would gather plate footage of the crowds and the signage so that we could keep racing on an empty track after everyone left, and VFX could drop the crowds and signage back in. For all those incredible moving shots with the actors in the paddock and the starting grid, Lukasz was on the Ronin 4D, with the Sony G Master Primes, to get whatever he could in the compressed window of time we had.

Bielan: We called the [Ronin] 4D camera “the turkey head.” It’s an 8K camera with a stabilizing head; they used it on Adolescence to create true oners with no stitches. It’s like

VEGAS IS AN INSTALL, SO ALL THE LIGHTING IS LOW, AND IT GIVES THIS STARWARS WARP-SPEED FEELING – A STACCATO EFFECT WHERE THE FOOTAGE LOOKS FASTER THAN ANYTHING YOU’D EVER SEEN.”

CLAUDIO MIRANDA, ASC

a Steadicam with a much smaller footprint. There’s a limitation as far as lenses, because it’s so small. But you can go up and down without creating an arc, run forwards or backwards and change modes instantly. Since F1 allowed us to shoot on the starting grid, it was the perfect tool. We used it during the anthem at Silverstone. We were live with 140,000 people watching from the stands, millions more on television, and one shot to get the walk-and-talk with the actors as they got into their cars. No pressure! [Laughs.] We had another scene after the race when they go to weigh the cars and we had no idea where our hero car was placed, let alone how to navigate through all the different mechanics and car support people. You cannot even brush a car or it could be disqualified, so the size of the 4D saved us there as well.

Kosinski: At Silverstone, I knew we had to shoot Brad and Damson standing next to the real drivers during the anthem, another scene where a reporter approaches Brad and Damson at the back of the grid, and then Javier Bardem and Tobias Menzies waiting at the APX GP car, where Brad would walk into a third scene. We had eleven minutes to shoot all three scenes, and there would be about 2,000 people standing on the grid. We rehearsed with a stopwatch for two weeks. Every night we

would walk out onto the grid with cameras, and our AD would time it. On the day, we did a lens swap halfway through, but the beauty of the Ronin as an 8K platform is that you can really get two sizes out of one piece of coverage. There were limitations to those scenes, to be sure, but we could never have recreated that level of detail.

Miranda: All the tracks were so different. Vegas is an install, so all the lighting is low, and it gives this Star Wars warp-speed feeling – a staccato effect where the footage looks faster than anything you’d ever seen. I tried to get the track lights turned down because they were so bright – like a T11. From an aerial view it looked like Tron , this burning white light of brightness speeding through the streets. Vegas is a very bright city, but it was overwhelmed by the F1 lights. It was definitely a different look than the other locations. I loved the look we got at Monza. It starts in the day, and then the storm comes as we go into night, and that really served that part of the story, where Damson has the big crash that sidelines him from driving. The track at Abu Dhabi had the most variance from

a DP’s perspective. It starts an hour before sunset, goes into sunset, and then into night. While it looked great for camera, it was a challenge for continuity because we were shooting these races in real time.

Kosinski: From my point of view, Vegas was the most dangerous track for our actors. That track only exists for three nights out of the year, so there was no way for Brad and Damson to practice on it. All of their practice for Vegas had to be done on a simulator. The only time we had access to the track was in the middle of the night, when it was very cold and the tires didn’t have much grip. It’s a street track with no run-off areas, so the walls are right there. It’s also one of the fastest tracks on the circuit, and we only had one 15-minute window to shoot the sequence. For all those reasons, Vegas was the toughest track to work on.

Ming: The worst thing for us as camera technicians was if a track was dirty. You’d get these pits in the filters. With the 10-millimeter Voigtländers, you couldn’t put a flat in front, so we’d literally just toss the lens after it got beat up. Cold was good for the electronics but not wet, as we had some water get into the side pods. As for the wireless transmission, Vegas was an urban environment and full of RF, so that was tough to navigate; the track at Spa,

“I TRY TO LEARN SOMETHING NEW ON EACH MOVIE I DO, AND THIS FILM WAS AN ENTIRE ACADEMY OF THINGS WE’D NEVER DONE BEFORE.”

in Belgium, is out in the forest. Anything with high water content, like a ton of trees, means the transmissions won’t reach as far. There had been a sandstorm the first time we went to Abu Dhabi, and when we showed up they hadn’t cleaned up all the dust and debris, so we lost a lot of flats and lenses. The cameras looked like they had been sandblasted. Even at Silverstone, where the light was amazing at sunset, we’d start seeing bugs splattering all over the lenses. [Laughs.] Never a dull moment.

Bielan: All of the tracks had such a unique personality. The Spa track in Belgium felt like the most dangerous, where accidents were likely to happen. The track in Monza, where Damson’s car had the big crash, was quite an experience. For the crash, we had a dummy driver in the car going off a ramp at about 120 miles per hour. I was in a container on a remote head, and the other two cameras were on long lenses. I couldn’t bring the car into frame as we needed to cut, so I’m waiting for it to come into frame, going at speed, and I have to follow up in the air until it hits the ground. Well, the car launched much higher and further than anyone expected. I still remember Joe’s reaction watching [laughs]. I had no idea what 120 miles per hour would look like on the remote head, so once it hit my frame, I just stayed with it until it finally came down. I was the only camera of the three that got the landing.

on the podium

Kosinski: Lewis [Hamilton] introduced us to F1’s CEO, Stefano Domenicali, so we started at the top. Jerry [Bruckheimer], Brad and I flew to London and met with Stefano in the downtown London headquarters of F1. And I pitched him the concept of the movie. This was five months

A-CAMERA

before Top Gun had come out in theaters. I explained the methodology we wanted to use for the film, and then after the meeting we walked across the street and watched Top Gun: Maverick in IMAX. He was a huge fan of the original Top Gun . So, I think he understood, after seeing what we did with Top Gun , how we wanted to take that style of filmmaking and apply it to F1, and what a good thing it could be for the sport.

Miranda: I was initially a little scared about doing the car shots with no stabilization, as you need to connect with the eyes of the actors, and if there was too much shake, that would detract from the emotional pitch of each scene. I have to say that by the end of the film Brad was just flying. He got faster and faster with each track, and by Abu Dhabi, we were joking, “Maybe we need to start this all over again.” Ironically, the bonding company wouldn’t allow him to drive over 140 miles per hour at first. So, he had to do a presentation to explain how it’s more dangerous to drive these cars at a lower speed than they’re designed for, because there’s less downforce and your traction on the track isn’t as good. Basically, the faster Brad went, the less likely he was to crash the car.

Bielan: I try to learn something new on each movie I do, and this film was an entire academy of things we’d never done before. Like, “How the hell am I supposed to pan from point A to point B with that car going almost 200 miles per hour?! How the hell am I supposed to walk backwards with Brad Pitt not knowing who or what is behind me, with no camera assist because we weren’t allowed to have anyone else from the crew in the grid during the shot?” Of course, working with Joe and Claudio, you always manage to figure out all those questions and have a blast doing it. This film was more than a job; it was a journey that I’d put at the very top of my entire career.

Ming: I remember at the beginning, Production asked Joe and Claudio when they would be capturing footage for the Volume, and they were like, “No, you don’t understand. There is no Volume work on a Kosinski/Miranda production. Everything is practically done.” [Laughs.] But the cooperation from all the different stakeholders on this was amazing. Starting with F1, which allowed us to be the eleventh team on the circuit. We had our own garage at Silverstone between Mercedes and Ferrari. People would walk down the pit lane and say, “Who is APX GP?!” The same with Apple, whose camera incubation team worked with Claudio to redesign the wing camera for us; Panavision, who jumped in to make the panheads; and Sony, who quite literally stopped manufacturing other products in their pipeline to make these cameras. They learned on Top Gun the kind of physical stress we put on the gear, so their engineering was durable and amazing. Most importantly, I want to thank everyone in the camera crew who were so key to making this happen. My long-time 2nd AC, Max Deleo, who got things going from the beginning and finished the film with us, and the skilled Local 600 team in Daytona, Florida, Las Vegas and Pismo Beach, California, as well as the U.K. team who got us through the rest of the world. You are only as good as those around you.

Kosinski: I’ve worked with Claudio on six features, with Dan on four, and Lukasz on two, and I can say they are all not just great filmmakers and artists, they’re people, like myself, who love solving technical problems. Claudio is a mad scientist, and Dan is on another level as far as AC’s go. It’s so important to have collaborators that you know and trust so well; the shorthand I have with Claudio means there’s no need for long conversations about aesthetic points of view. On this movie it was like, “We just have to go.”

“YOU NEVER KNEW WHAT WAS COMING NEXT, SO THIS MOVIE DEPENDED ON A CREW WHO WERE INCREDIBLY AGILE AND RESOURCEFUL,” KOSINSKI DESCRIBES. “PEOPLE LIKE DAN MING [ABOVE], WHO WOULD PRINT OUT NEW CAMERA PARTS ON A 3D PRINTER AT NIGHT IN HIS HOTEL ROOM AND INSTALL THEM THE NEXT DAY. EVERY SHOT IN THIS MOVIE WAS EARNED WITH A LOT OF TRIAL AND ERROR.”

LUKASZ BIELAN

(CENTER) SAYS THAT “THIS FILM WAS MORE THAN A JOB; IT WAS A JOURNEY THAT I’D PUT AT THE VERY TOP OF MY ENTIRE CAREER.”

Directors of Photography

Claudio Miranda, ASC

A-Camera Operator

Lukasz Bielan, SOC

A-Camera 1st AC

Dan Ming

A-Camera 2nd AC

Max DeLeo

B-Camera Operator

Natasha Mullan

B-Camera 1st AC

Bob Smathers

B-Camera 2nd AC

Farisai Kambarami

C-Camera 1st AC

Mateo Bourdieu

C-Camera 2nd AC

Jeremiah Kent

D-Camera Operator

Tucker Korte

D-Camera 1st AC

Jacqueline Stahl

D-Camera 2nd AC

Tracy Myrick Loader

Lauren Cummings

Rohan Chitrakar

Additional DIT

Calvin Reibman Utility

Justine Quinones

Matrix Head Tech

Kenny Rivenbark

Hydroscope Lead Tech

Adrian Santacruz

Hydroscope 1st AC

Hilton Garrett

Still Photographer

Scott Garfield

Directors of Photography

Claudio Miranda, ASC

A-Camera Operator

Lukasz Bielan, SOC

A-Camera 1st AC

Dan Ming

A-Camera 2nd AC

Kalli Kouf

B-Camera Operator

David Emmerichs, SOC

B-Camera 1st AC

Bob Smathers

B-Camera 2nd AC

Tracy Myrick

C-Camera Operator

John Skotchdopole

C-Camera 1st AC

Sean Kisch

C-Camera 2nd AC

Kyle Deven

D-Camera 1st AC

Jordan Pellegrini

Loader

Hillary Baca

Utility

Justine Quinones

Additional Utility

James Smathers

Car Rigging ACs

Max DeLeo

Jeremiah Kent

Farisai Kambarami

Crane Operator

Adrian Santacruz

Crane Tech

Jesse Hinojosa Jr.

Head Tech

Garrett Dunn

Still Photographer

Scott Garfield

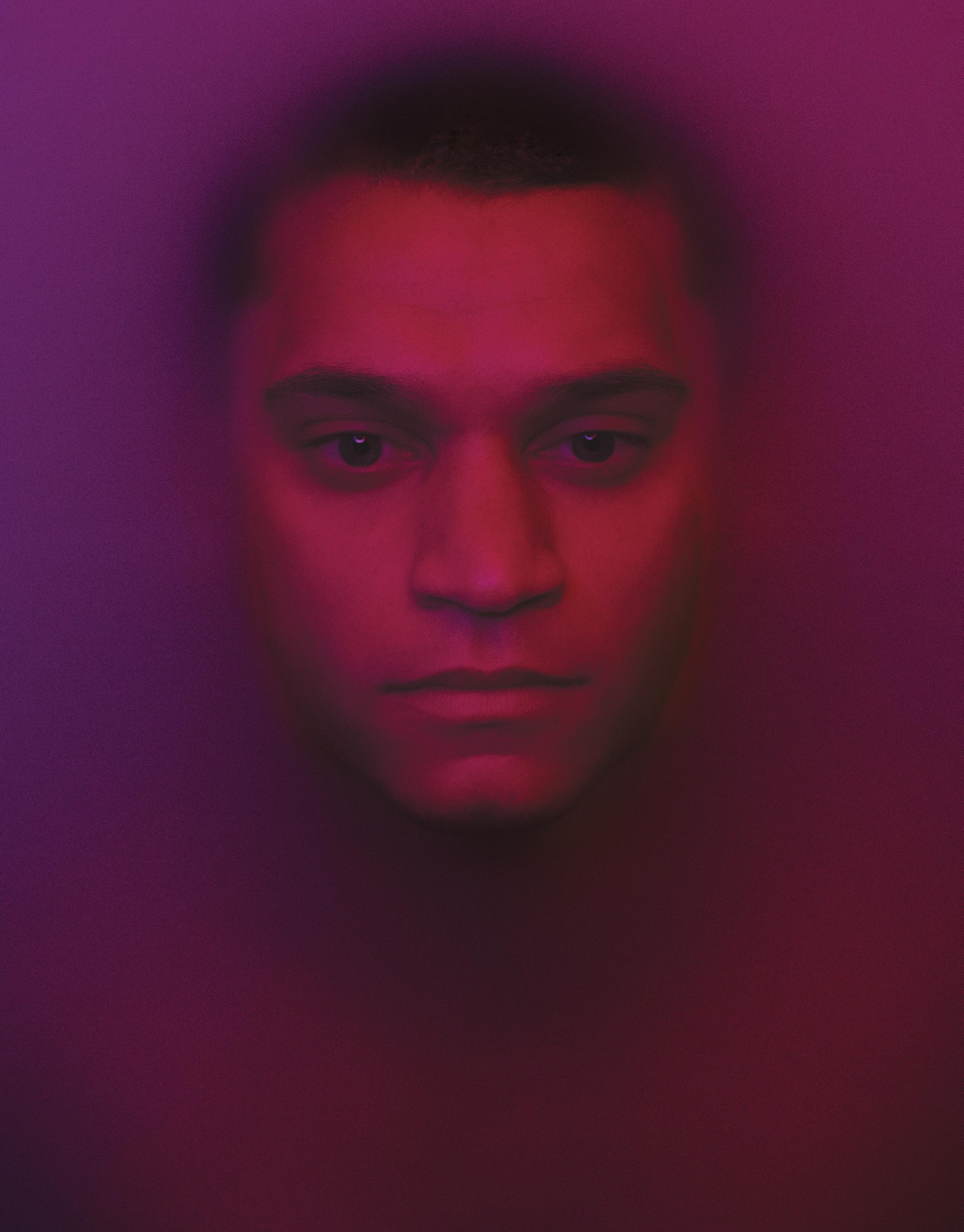

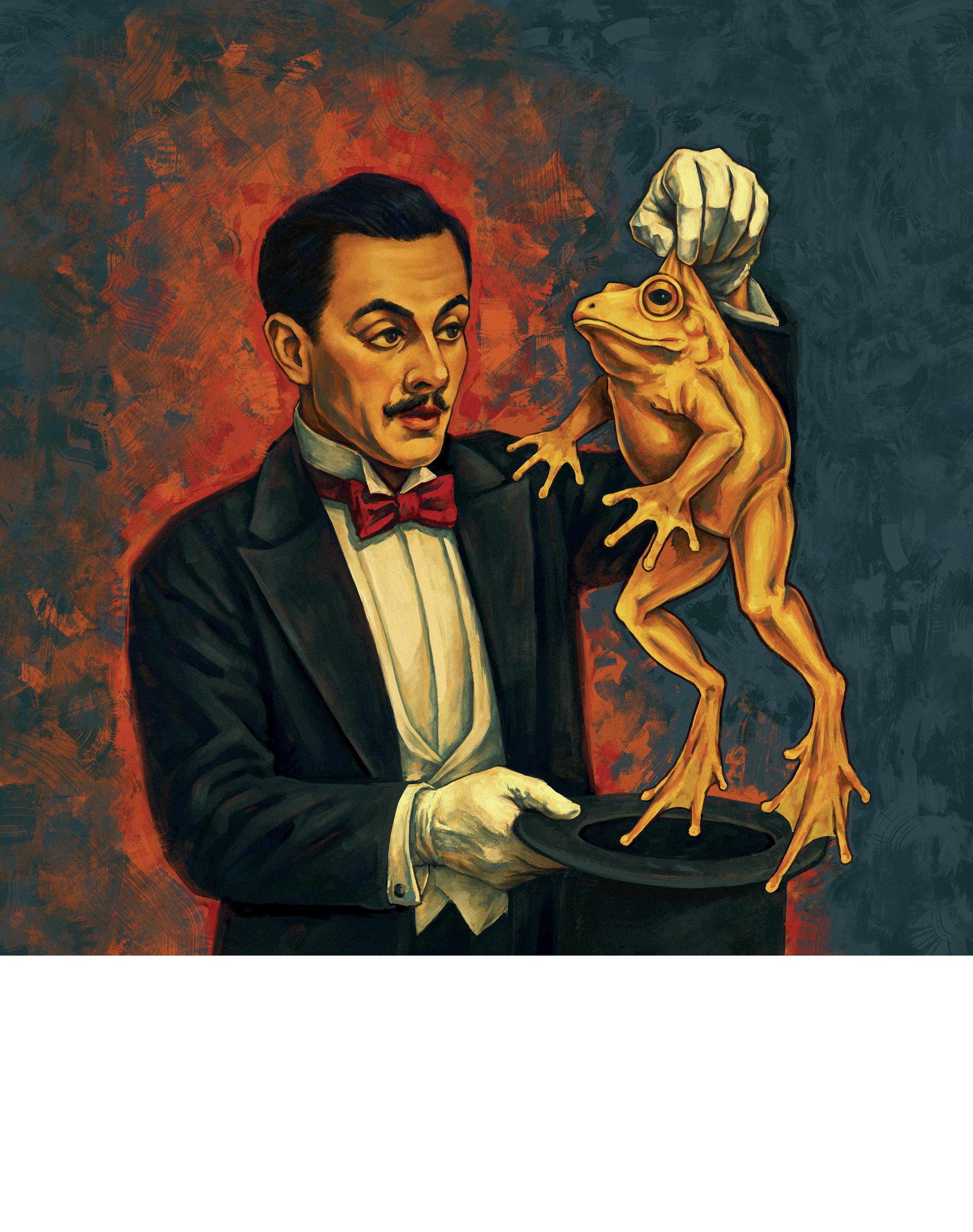

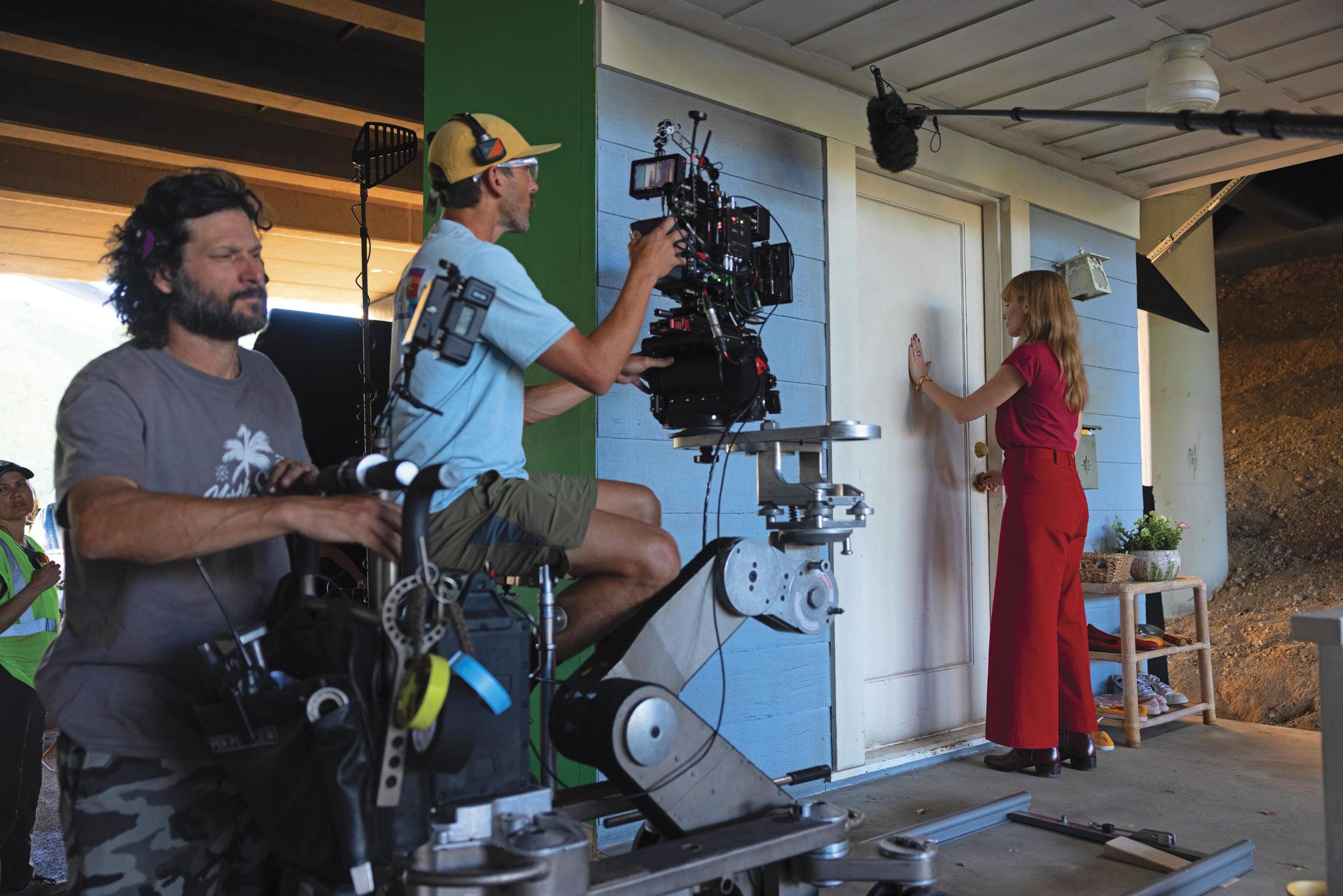

KIRA KELLY, ASC, AND HER UNION CAMERA TEAM CALL AN ON-SET AUDIBLE: SHOOTING WITH THE FLIR THERMAL CAMERA FOR THE SPORTS-HORROR FEATURE HIM .

BY MARGOT LESTER

It’s not every day one says yes to a project that turns out to do something no other film has. But that’s exactly what happened for the union crew on HIM, the latest feature from Jordan Peele’s Monkeypaw Productions (distributed through Universal Pictures). The film’s horror-thriller, as you’d expect from Peele, is mashed up with many other cinematic genres, including sports, sci-fi, and high-tech among them; one is hardpressed to find a precedent of the innovative use of new technology required to deliver it.

HIM chronicles a week in the life of Cameron Cade (Tyriq Withers), an elite football player at the apex of his early career fame, and his mentor Isaiah White (Marlon Wayans), himself an aging gridiron great. We see the two athletes navigate a system that treats people like resources to be commodified and exploited. It is, in its own way, ripped from the pages of real life.

“Jordan and Win [Rosenfeld] read the script and rightfully thought that the central mischief of making a football-horror movie was too delicious to pass up,” says Creative Producer Ian Cooper. “This film operates on multiple levels – as an allegory, a warning, an advertisement, a fever dream, and a revisionist unpacking of one’s origin story.”

To tell the tale, first-time feature director Justin Tipping ( Exposure , page 22) approached Cooper and Local 600 Director of Photography Kira Kelly, ASC [ICG Magazine October 2024], with an idea to deliver a literal inside look at the physical and mental strain players go through on the field and during conditioning and recovery. The challenge: Find a way to “slip in and out of a sort of ‘concussionvision’ living X-ray format to visually tell the story of Cameron’s head injury,” Cooper remembers. “We discussed what Łukasz Żal and VFX Supervisor Rachael Penfold accomplished in Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest using the FLIR thermal camera. I immediately thought of attempting a version of the stereoscopic day-for-night rig that our Nope cinematographer, the

legendary Hoyte Van Hoytema, invented.”

The idea was to ride the Teledyne FLIR with an ARRI ALEXA 35 to capture images in both formats simultaneously. “The rig would make it so that if you were shooting in ‘normal,’ at the point of impact the image would suddenly flicker into this thermal, haunting slow-motion world,” Kelly explains. “But it was just a theory because we didn’t have a thermal camera.”

And finding one was not as simple as dialing-up the local camera house. The image-capture technology, originally developed for military and surveillance use, is now regularly deployed in medicine, firefighting and building inspections, among other uses, which increasingly includes cinema. “We first tried a traditional stereo rig, but it didn’t work – the FLIR reads heat, and the reflection off two-way glass was cold,” explains Kelly’s longtime Key Grip Rudy Covarrubias. The goal was to get the FLIR “just millimeters from the Panavision lens on our main camera,” he adds. “Since no rig like that existed, we had to fabricate a custom cage for the FLIR –something we could easily take on and off, with micro-adjustments. Once we found the parallax point where the FLIR and the main lens converged, we locked it in.”

Covarrubias made the aluminum rig to “adjust the pitch, roll and positioning of the FLIR so we could have the minimum amount of parallax and control the convergence point of the two cameras,” adds VFX Supervisor Andrew Woolley. “The lenses and aspect ratios meant the

‘work safe’ area of the thermal camera was cropped, so Kira had to frame wider on the ALEXA 35 than desired in order to capture the center-punched safe area of thermal. The camera crew shot grids for every lens variation so we could map those beautiful characteristics back into the cropped frame.”

As Kelly describes, “We were shooting anamorphic with the T-series lenses from Panavision that Dan Sasaki customized for me – he was able to dial-in a look that I ended up loving.” Customizations included several falloff adjustments to some of the wider T-Series focal lengths. The package also included 2× anamorphic zooms, AutoPanatars, Pathé and Petzval anamorphics. The flashbacks were captured with spherical H-series lenses for a unique style and aspect ratio. The FLIR’s lens set included 21 2 -, 36and 83 4 mm focal-length glass.

The project paired the ALEXA 35’s anamorphic 4.6K 1.85× desqueeze with FLIR’s 1K spherical image. “After calculating FOV, we determined the FLIR 36-millimeter matched most closely to the T-Series 50-millimeter, and that became our starting point,” explains D.I.T. James Notari. “In terms of thermal file format, we chose CSQ over MPEG – it offered more consistent FPS and didn’t embed thermal

metadata. However, CSQ files could only be opened with proprietary FLIR software on a Windows workstation. After testing and working closely with VFX, Kira, and Ian, we finalized the plan to magnify the FLIR image by 25 percent and the ARRI image by 20 percent. VFX would later enhance these thermal images, filling in the remaining negative space. At my D.I.T. cart, I used a Blackmagic Design ATEM splitter to fine-tune the overlay – adjusting position and magnification – before feeding the composite image to an on-set monitor for [A-Camera Operator] Scott Dropkin [SOC] to view.”

They were almost there. But the FLIR body wasn’t made to support extra rigging or pulling focus with a motor. So Scott Steele at Panavision New Mexico helped design some custom gears, and Albuquerque-based A-Camera 1st AC Meghan Noce 3D-printed a focus-pulling ring that clamped to the body. Noce pulled focus for the FLIR, and B-Camera 1st AC Lewis Fowler pulled for the ALEXA 35.

Dropkin was happy with the results. “It wasn’t like a true 3D rig where it was just massive, so when we started rolling with it, we treated everything like a normal shot with the actors and football players and the camera movement,” he recalls. “We

probably spent a little more time in the playback, mainly to watch the FLIR footage and make sure that that worked.”

Now that they had the camera and the rig, the Local 600 team could put the FLIR through its paces. “Those first tests were to find our boundaries,” Kelly recounts. “Can we make this work in studio mode? Can we make it work handheld? We found that about five feet away from the camera is where the focus and the two images would come together.” Speaking of handheld, the crew mounted full-sized helmets to the front of the ALEXA 35 for several of the action sequences, including a shot with a special-effects vomit hose attached. “For that one, Scott had to suit up in weather gear and put on football cleats so he could hand-hold the camera as if he was puking through the helmet!” Noce remembers. Testing also revealed unanticipated issues unique to thermal photography. Right off the bat, they discovered that the FLIR couldn’t read traditional slates. Second AC’s Oscar Cifuentes and Hillary Baca were tasked with figuring out a solution. They made aluminum foil-backed slates with 3D-printed magnetic letters. When the team was in rooms with no reflective heat

(the system worked off reflective heat) they would use heat guns to generate the necessary temperature contrast between the background and letters. “The ‘thermal slate’ quickly became a crew favorite,” Noce shares. “It got some chuckles and turned into one of those little things everyone looked forward to.”

Another issue was showing sweat oncamera – a crucial element of a sports movie (suspense as well). “If you wanted to see sweat on a person’s face, you actually had to cool them down with ice because the sweat showed up warm, like their skin,” Dropkin shares. “The ‘sweat’ had to be cold to be seen!”

Chief Lighting Technician Bob Bates had to factor in the heat put off by the onset lighting. “The main consideration was avoiding hot tungsten lights since they would interfere with the thermal imaging,” Bates explains. “I usually work mainly with LED fixtures, which don’t emit as much heat as traditional tungsten units, but we did have some sets that had larger tungsten units that would alter the look of the frame. I was impressed with the rigs that our grip team was able to build for the scenes that required them in stereo.”

One of these was on the Whites’ private practice field, which Kelly describes as “basically a prop storage tent. We found out well into prep, I mean like a few weeks out, that it couldn’t support any rigs – it wasn’t weight-bearing at all. I ended up working with Bob and Rudy trying to figure out the lightest-weight lights I [could] use and still make it look cool. We ended up using Hyperion tubes and aircraft cable to rig it.”

With disruption and damage being core elements of the story, Kelly and Tipping wanted a symmetrical mise en scène to ground the characters within their surroundings.

As Dropkin recounts, “When we’d lay dolly track and do moves, we were tape measuring, using the laser pointer, and even using construction line markers to make sure we were perfectly centered. For example, if there were two lights in the frame, we’d measure, and sometimes it’d be like, ‘Oh, this lamp on this side is a half-inch off from the lamp on that side.’ And we’d actually have to talk to the art department and electricians: ‘Can we move this by half an inch?’ There was a lot of math involved!”

Notari recorded and captured all the footage at his cart to ensure consistent lighting, framing, and exposure. “I kept detailed notes and regularly reviewed the camera department’s Zoe logs,” he states, “so when it was time to recreate or match a previously shot scene, we had all the information we needed locked in.”

While Tipping was loyal to Peele’s preference for doing as much in-camera as possible, there was still plenty of effects work that was required. “[VFX Supervisor] Andrew [Woolley] had to synthesize all the footage and add to the imagery by compositing CG skeletal assets for all the characters, which was an elaborate, painstaking process that necessitated a graphic pipeline flowchart that looks like a NASA manual,” Cooper marvels.

“Tipping’s vision was rightfully grand,