Lemon’s THE SWEETNESS OF

Dr Cormac Moore is an historian-in-residence with Dublin City Council and a columnist with The Irish News who also edits its ‘On This Day’ segment. He has published widely on Irish history, including the books The Root of All Evil: The Irish Boundary Commission (Irish Academic Press, 2025), Laois: The Irish Revolution, 1912–1923 (Four Courts Press, 2025), Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019), The Irish Soccer Split (Cork University Press, 2015), and The GAA v Douglas Hyde: The Removal of Ireland’s First President as GAA Patron (The Collins Press, 2012).

Alan Tate is a grandson of Thomas Tate who, with his son Frank (Alan’s father), led and modernised Lemon’s from 1917. Alan remembers very well his grandfather and his many visits to both the O’Connell Street shop and the factory in Drumcondra. His interest in family history spurred him to assist Emma Blain with her book ‘A Sweet Life’: Recollections of Frank Tate and to assemble and preserve the family collection of Lemon’s official records and other memorabilia, much of which is referred to in this book.

Lemon’s THE SWEETNESS OF

THE S TORY OF T

I RELAND ’ S FAVOURITE C ONFECTIONER

Cormac Moore and Alan Tate

First published in 2025 by Merrion Press

10 George’s Street

Newbridge Co. Kildare

Ireland

www.merrionpress.ie

On behalf of Dublin City Council

c/o Dublin City Library & Archive

139–144 Pearse Street

Dublin 2

© Cormac Moore and Alan Tate, 2025

978 1 78537 582 8 (Hardback)

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owners and the publisher of this book.

Typeset in Minion Pro 11/16 and Royal Signage Cover and internal design by Alba Esteban | Alestura Design

Merrion Press is a member of Publishing Ireland

Introduction

Lemon’s Pure Sweets has been a part of the Irish landscape for almost 200 years. Started in the 1840s by Armagh-born Graham Lemon, the brand epitomised quality above all else. While two families – the Lemons and the Tates – dominated the running of the company for most of its history, the mantra of exceptional quality and purity remained throughout.

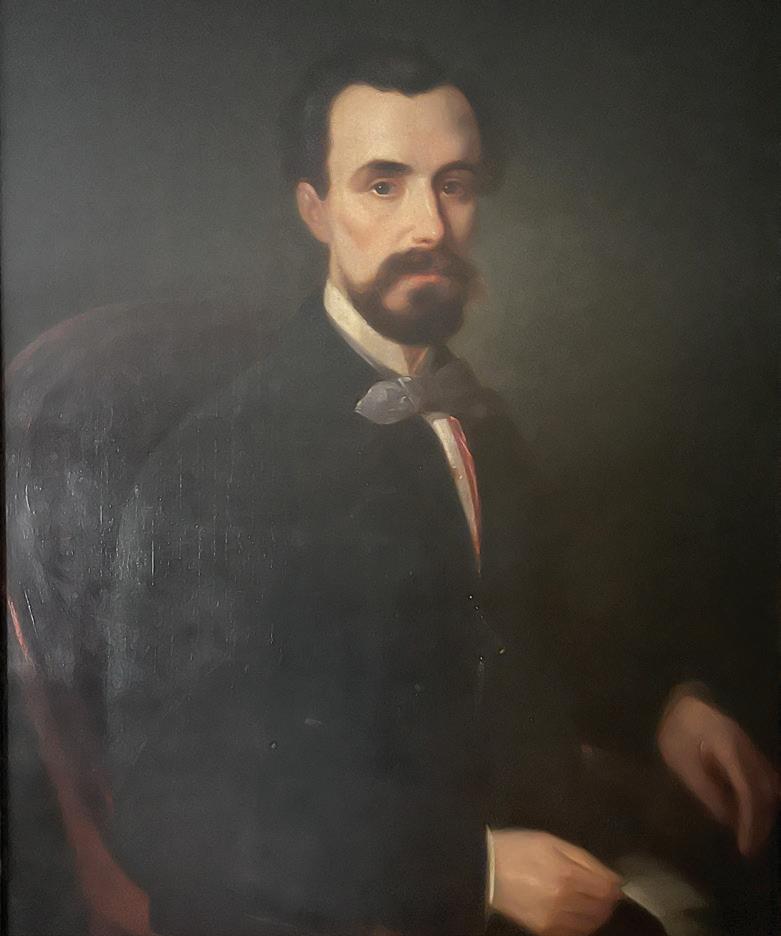

This book tells the fascinating story of the Lemon family, who, through Graham’s ingenuity and business skills, achieved great wealth and fortune during his lifetime. He would come to own and lease multiple properties in prime locations in Dublin city centre, and as he owned most of the property on Little Grafton Street, off Grafton Street, it was renamed Lemon Street in his honour in 1871. Tenants of Graham’s included the Gunn brothers and their new Gaiety Theatre, as well as James Connolly. Inexplicably, however, Graham left no will, so, after his death, bitter intra-family feuds, many of them played out in court, lasted for decades.

Despite this, the brand survived and, following the death of Graham Lemon’s last remaining son, Thomas Owens, in 1917, the running of the company passed to

The Confectioner’s Hall. (Courtesy of the Tate Family Archive)

another family: the Tates. Belfast-born Thomas Tate led Lemon’s for over forty years before his son Frank became managing director. Both Thomas and Frank oversaw the expansion and modernisation of the company after the twenty-six counties in Ireland gained their independence.

However, this is not just a story of two families. It is a social history of Ireland told through the prism of one company that existed throughout a crucial period in the country’s history. Lemon’s Pure Sweets bore witness to famine, the Victorian era, the campaign for Home Rule, two world wars, the Irish revolution and the first sixty years of statehood. While its directors, as in any other company, made good and bad decisions, external factors outside of their control had the most impact and were the primary reason for the company’s closure in the early 1980s. Even so, the name lives on through the brand, through the remaining letters on the ‘The Confectioner’s Hall’ sign on O’Connell Street, and through the many nostalgic memories people have of one of Ireland’s most iconic companies and its popular products.

Beginnings On�

Company histories of Lemon’s Pure Sweets state that the company was started by Graham Lemon on Dublin’s Capel Street in 1842, before moving to a larger premises on Sackville Street (present-day O’Connell Street) in 1847. In one of the first publications about the company’s history, written for Lemon’s in 1919, it was claimed that Graham was ‘an industrious and enterprising young man, who was skilled in the making of sweetmeats’ and who ‘started in a very small shop in Capel Street to cater for the wants of the sweet-loving public’.1 It is known that Graham lived above the shop at 102 Capel Street, with his wife, Mary Barkley, whom he married sometime in the 1840s.

An Irish Times version of the Lemon’s origin story, published in 1955, gives a flavour of its humble beginnings:

a young woman in a dark blue velvet cloak with open sleeve edges with grey fur to match her muff, and wearing a pale blue satin bonnet and dress, pushed open the door of a little shop in Dublin’s Capel Street.

A young man in a clean white apron greeted her. Nobody knows the name of the young woman, but the man was Graham Lemon, steadily gaining a reputation throughout the city of his skill as a maker of bonbons, barley sugar and such-like sweet meats.2

Graham Lemon. (Courtesy of Keith Lemon)

Mary Lemon (née Barkley). (Courtesy of Keith Lemon)

‘Sweetmeat’ denoted any sweet delicacy, from candies, cakes and pastries to preserves and sugar-coated fruit. Confectionery itself originated in or around 2,000 bc when ancient Egyptians combined fruit and nuts with honey; chocolate originated in about 1,000 bc with the Aztecs of Mexico, who used cocoa beans to make a bitter drink – sugar was not added until hundreds of years later. In the nineteenth century, some popular British sweetmeats took their names from prominent figures of

the Napoleonic Wars: Bonaparte’s Ribs were lollipops, Wellington Pillars were sweetmeats flavoured with ginger, and Nelson’s Balls were made from gingerbread and sugarplums.

When Graham Lemon was starting his business, chocolate and confectionery were beginning to be made on an industrial scale. As food historian Marjorie Deleuze noted, in 1847:

Capel Street and Essex Bridge, Dublin. (Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Advertisements for Chocolat Lindt (1924) and Toblerone (1925) (Illustrated London News)

the British chocolate maker Joseph Fry had an idea that revolutionized the chocolate trade. He decided to mix cocoa powder and sugar with melted cocoa butter and obtained as a consequence a chocolate paste that was mouldable. In 1868, John Cadbury produced his first chocolate box decorated with a painting of his daughter cuddling a kitten. In 1879, Swiss man Rudolph Lindt invented the ‘fondant’ and twenty years later Jean Tobler created what was to become the world famous Toblerone bars.3

Speaking in 1918, Wilfred Hartnell, who represented grocer and retail businesses in Dublin, claimed chocolate was first sold in Ireland in the late eighteenth century. According to Hartnell, in 1782, ‘at the conclusion of the inaugural dinner of the Knights of St Patrick at Dublin Castle, it [chocolate] was handed round in bowls as a beverage’. He also claimed chocolate was first retailed by Findlater and Co. on Sackville Street in 1832 and seventeen years later, in 1849, the first confectionery shop was started on the same street by Graham Lemon who ‘did not handle chocolate until 1866’.4

Findlater’s shop front, O’Connell Street, Dublin. (Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

The origin story of Graham Lemon greeting the lady customer was the inspiration behind the company’s logo years later. If she ever existed, it is probable the young woman who entered Lemon’s shop in Capel Street was reasonably well off because, at the time, Lemon’s barley sugar cost a shilling an ounce. Sugar was still a very expensive commodity and a luxury product in the 1840s,

although from then the falling price of sugar made it practical for confectioners to set up shops for the first time, so that sweets became available to the general public. And Graham Lemon’s growing status as a maker of high-quality sweets allowed his business not only to survive, but to consider expanding.

While no records exist to show that Graham Lemon started his confectionery business in Dublin in 1842, there are records of him having a share in a confectionery business on Donegall Street in Belfast in the mid-1840s. Born in Mountnorris in County Armagh in 1819, the eldest son of James Lemon and Sarah Graham, Graham had grown up in Belfast. His interest in confectionery probably came from his father, who was listed as a grocer and confectioner on the Falls Road in 1846. By then, Graham was running his own business on Donegall Street with his cousin

Lemon’s Pure Sweets logo with the silhouette of the first lady customer from the origin story. (Courtesy of David Twamley)

Mountnorris Presbyterian Church, where Graham Lemon was baptised. (Courtesy of Mary E. Lemon)

In July 1846 the Banner of Ulster newspaper reported on a meeting of the Independent Order of Rechabites, a temperance movement, when the first ‘Olive Branch Tent’ was opened in Ireland. After the meeting, the attendees ‘adjourned to Mr. Graham Lemon’s confectioner, Donegall Street, where a tea party was held’. The refreshments were ‘of the best quality, and abundant in quantity’. The newspaper also claimed that ‘[a]mongst the invited guests was Frederick Douglas[s], the celebrated anti-slavery lecturer’.6 Douglass was a famous African-American abolitionist, orator and writer, who

was formerly enslaved. He toured and lectured in Ireland and Britain from 1845 to 1847, and at the same time his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, was published. Douglass visited Belfast in June and July 1846, giving several lectures on slavery and the temperance movement, of which he was also a big advocate.

Months later, in September, at a Belfast Protestant Association ‘annual soiree’ that saw a large Orange Order presence, Graham Lemon acted as caterer. The ‘refreshments consisted of tea and cakes, and fruits. They were of excellent quality and supplied in profusion.’7 A more unsavoury incident occurred in November 1847 at his William Redmond Lemon, but by 1846 he was the sole proprietor, after a falling out with William Redmond.5

Frederick Douglass. (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper)

The Confectioner’s Hall – A Retrospect, 1847–1919. (Courtesy of the Tate Family Archive)

Belfast shop, when ‘some maliciously-disposed person, on a car driving rapidly, threw a stone at the window of Mr. Graham Lemon’s, Donegall-street, breaking a pane of glass, a jar of confections, and striking on the cheek a female who was in charge of the shop’.8

Interestingly, the company histories of Lemon’s fail to mention the shop Graham Lemon had in Belfast and instead claim he started his career as a confectioner in Capel Street before moving to Sackville Street. Perhaps his focus moved from catering to the manufacturing of confectionery after moving to Dublin. What is indisputable is the quality of the products that Lemon produced. He began his business ‘with the policy that quality was

of paramount importance; only the freshest, purest ingredients went into the making of his product’.9 This remained company policy within and beyond his lifetime. While other shops sold confectionery at cheaper prices,

Sackville Street – The Finest Thoroughfare in the World: Civil and Uncivil Servants. (Courtesy of Dublin City Library and Archive)

A woman with child begging in Clonakilty. (Illustrated London News)

A famished boy and girl search for potatoes in the ground at Caheragh in Cork. (Illustrated London News)

‘those [for] whom quality counted … purchased their sweets exclusively from Graham Lemon. Purity was the foundation on which he built up his reputation, and this fact accounts for the success he gained at the start.’10 Initially, he made his sweets by hand, with no assistance. As he ‘cranked the handle of the little “mangle” which formed his barley sugar into twisted sticks he began to think of more space in which to work and the employment of some assistants’.11

Whether by moving all the way from Belfast or just a few blocks away from Capel Street, Graham Lemon expanded his business, opening his shop at No. 49 Lower Sackville Street. Company histories say this happened in 1847, but it was most likely later, in 1849 or 1850. (The Irish Times claimed it opened in 1849.)12 To mark the new premises on Sackville Street, Graham Lemon put the name ‘Lemon & Co.’ on the fanlight over the door – and, being a man proud of his craft, he named the premises ‘The Confectioner’s Hall’. He hoped to benefit from ‘carriage trade’: busy Sackville Street was known as ‘the finest thoroughfare in the world’, which ‘civil and uncivil servants’ frequented.13 The Freeman’s Journal considered it ‘splendid … so deservedly admired by strangers, and not equalled as a streetway by any in any other city in the world’.14

While Graham Lemon was starting out on his career

Skibbereen in 1847. (Illustrated London News)

providing confectionery to people who could afford to buy his luxurious treats, millions in Ireland were struggling to find anything to eat at all. Ireland, experiencing its darkest period, was deep in the grip of the Great Famine. The poorer half of the population was almost totally reliant for subsistence on one food source alone – the potato. When a series of blights struck – particularly at the end of July 1846, which wiped out over 90 per cent of the crop – death and devastation followed in unprecedented numbers.15 The famine, which lasted from 1845 and ended in some places as late as 1852, had a catastrophic impact on the island, with over 1 million dying as well as the mass emigration of about 1.5 million people. Emigration continued throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, resulting in the halving of the Irish population from about 8 million in 1840 to 4 million by the turn of the twentieth century. Rural parts of Ireland were most affected, with some western parishes losing over 50 per cent of their population.

During the famine years, Ireland also mourned the death of one of its most revered figures, Daniel O’Connell, the ‘Liberator of Ireland’. O’Connell died in Genoa, Italy, in May 1847 on his way to a pilgrimage in Rome. His dying wish was for his heart to be buried in Rome and his body in Glasnevin Cemetery. His funeral in August 1847 in Dublin was one of the largest the city had ever seen. The cortège proceeded along the street that would later bear O’Connell’s name as it made its way to Glasnevin. It was during this time of upheaval and flux that

(Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Funeral cortège of Daniel O’Connell on Westmoreland Street, before moving to Sackville Street, on its way to Glasnevin Cemetery in August 1847. (Illustrated London News) Daniel O’Connell.

Graham Lemon moved to his new, enlarged facilities on the same street, installed manufacturing machinery and hired front-of-house sales staff. The machinery and processes were new to Ireland at the time – indeed, Lemon & Co. is considered to be the first company in Ireland to manufacture confectionery on an extensive scale. The entire building on Sackville Street was used for the sweet-making operation – production, packaging and sales. The firm, proud of the purity of its product, used the slogan ‘You cannot eat a better sweet’.

Passers-by ‘stopped to look through diamond-paned windows at the little piles of sweet-meats he set out for exhibition; smart carriages drove up to the door and Graham Lemon and his staff prospered.’16 On a visit to Ireland, the actress Frances Anne ‘Fanny’ Kemble (famous in Britain and America, particularly for her performances in Shakespearean plays), who was performing at the Theatre Royal, raved about Lemon’s bonbons, helping to further raise the company’s profile. Although confectionery was still so expensive that it

The actress Fanny Kemble reading Shakespeare in 1850. Her visit to Lemon’s shop to try the bonbons helped the profile of the company to grow. (Illustrated London News)

could only really be bought by the gentry, Lemon’s was becoming a household name.

In April 1850 a freak thunderstorm hit Dublin: it was followed by a shower of huge hailstones that some witnesses claimed were ‘as big as hen’s eggs’ – they were certainly as large as the mint humbugs made by Lemon’s.17

The Cork Examiner described the storm as ‘fearful and destructive’, claiming there ‘never was a hurricane so peculiar in its effects, so tropical and violent while it lasted – upwards of half an hour’. The storm caused damage totalling £27,000. The Round Room of the Rotunda, the show yard of the Royal Dublin Society and the Mansion House were among many of the buildings damaged by the storm. The Cork Examiner wrote that the ‘quantity of glass destroyed is enormous, and whole streets, especially those which faced the west and north, had not a whole pane left in the windows’.18 The Confectioner’s Hall did not escape either – the charm of the diamond-paned windows was gone, a heap of broken glass.

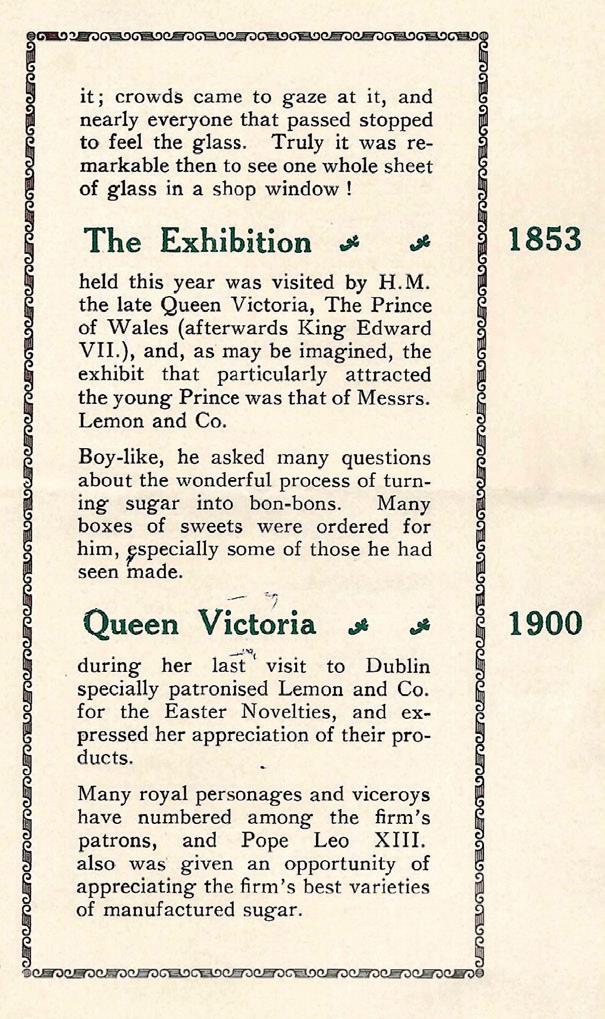

Graham Lemon turned this misfortune into an opportunity: the windows had contained tiny, square panels of glass but now the shop became the ‘first shop in Dublin to have plate glass in the windows … The public wondered at it; crowds came to gaze at it, and nearly everyone that passed stopped to feel the glass.’19 At the time, it was considered remarkable to see one whole sheet of glass in a shop window.

With a new, enlarged display window on show, the business continued to thrive. Admitted to the Board of Irish Manufacture and Industry in February 1851, Graham Lemon was described as ‘lozenge manufacturer

An illustration in From Bustle to Hustle 1842–1942, Lemon’s Centenary Booklet, telling the story of the square-shaped glass being replaced by plate-glass windows in 1850. (Courtesy of the Tate Family Archive)

In 1851 Graham Lemon travelled to London, where he had a stand at the Great Exhibition in the newly designed Crystal Palace building in Hyde Park. It offered him an opportunity to demonstrate his products and processes at the first-ever international exhibition, which over six million people visited from May to October 1851. So successful was the exhibition that it spawned a long succession of fairs in other cities, including Paris, New York, Vienna, Chicago and Dublin. But it was the Great Industrial Exhibition of Dublin two years later, in 1853, that provided the biggest boost to Graham Lemon’s business yet.

The Great Industrial Exhibition Building in London in 1851. (Illustrated London News) and confectioner, of Sackville Street, a gentleman who has successfully competed with foreign manufacturers in his own line’.20 Customers sought Lemon’s barley sugar and mint humbugs; others asked for the now-forgotten brown sticks called ‘Bath pipe’, known for their health benefits in removing ‘coughs and colds’. People could also purchase ‘Yellow Man’ – one of the earliest kinds of rock, later to become a feature of most tourist resorts.

‘… one of our most wealthy and respectable citizens’ chapter Two

Opening of the Great Industrial Exhibition in Dublin in 1853. (Illustrated London News)

Map of the Great Industrial Exhibition in Dublin in 1853. (Illustrated London News)