Twelve Paintings Colin Davidson

Mark Carruthers is one of Northern Ireland’s best known and most respected broadcasters. He joined BBC Northern Ireland in 1989 and now presents several well-established political programmes on television and radio, including The View, Sunday Politics and Red Lines. Mark studied political science at Queen’s University Belfast, graduating in 1987. In 1989 he was awarded a Master’s degree in Irish politics. He received an honorary doctorate (DLit) from Queen’s in 2019 and is currently Visiting Professor of Media at Ulster University.

Beyond politics, Mark is a passionate advocate of the arts. He served on the board of the Lyric Theatre in Belfast for almost fourteen years – eight of them as chairman – and was a leading figure in the successful campaign to rebuild the theatre at a cost of over eighteen million pounds. He also served for many years as chairman of Tinderbox Theatre Company and sat on the board of the Old Museum Arts Centre. In 2011 he was awarded an OBE for services to the arts in Northern Ireland.

His previous publications include Stepping Stones: The Arts in Ulster 1971–2001, co-edited with Stephen Douds and published by Blackstaff Press in 2001, and Alternative Ulsters: Conversations on Identity, published by Liberties Press in 2013.

Colin Davidson

Twelve Paintings

conversations with Mark Carruthers

For Pauline and Alison

First published in 2025 by Merrion Press 10 George’s Street Newbridge Co. Kildare Ireland www.merrionpress.ie

© Mark Carruthers and Colin Davidson, 2025

978 1 78537 572 9 (Hardback)

978 1 78537 576 7 (eBook)

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Typeset in Minion Pro

Merrion Press is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Foreword

Simon Callow

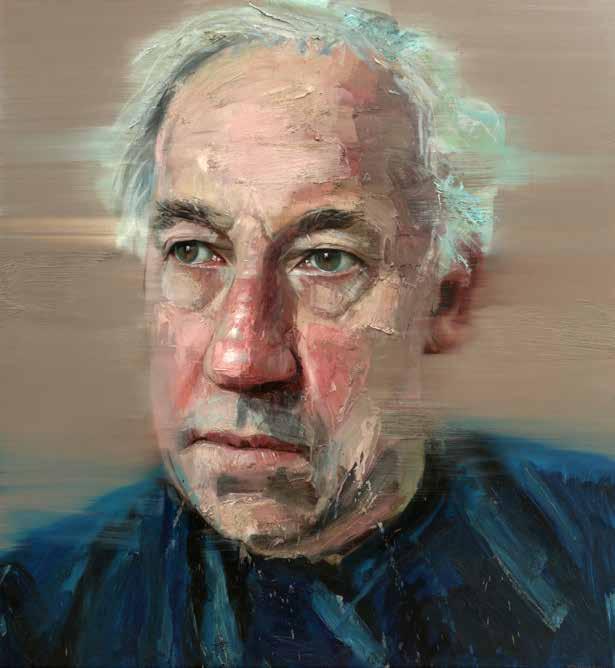

Sitting for a portrait is an immensely intimate experience. Clothed or unclothed, one is utterly naked. Nobody looks at you the way a portraitist does, except perhaps your mother, your lover or your doctor. In each case, the purpose is the same: penetration of the surface. What’s going on inside you? When I sat for Colin, I was rehearsing a play, heavily pregnant, as rehearsing actors are, with the character – or rather, in this particular case, the characters, plural. I was wrestling with Matthew Hurt’s extraordinary The Man Jesus, in which I was playing sixteen different people, starting with the pregnant Mary and taking in among others, en route to Calvary, John the Baptist, sundry apostles, Judas, Herod, Pontius Pilate and Mary Magdalene. Little of this, I’m sure, was visible from the outside, but when he showed me the portrait, it was filled – swarming – with inner life. A little while later I wrote of Colin and his portraits, a selection of which were on view in the foyer of the Lyric in Belfast: ‘He told me he had been a landscape painter by trade until he came to portraiture. That made sense. Those faces were part of a landscape, the landscape of a particular mind-set, a bodily vernacular, a facial terrain. And the paint itself, the physicality of it, created a sort of physiognomic topography, pits and craters and ridges. A facescape, you might say.’ opposite

vii Foreword

Portrait of Simon Callow (detail) 2013 oil on canvas 127 x 117 cm

We didn’t talk much during the session, but I felt I knew him – that we knew each other, in a curiously intimate, no words necessary sort of a way. Once when we happened to be in Belfast at the same time, I took him to a lunchtime concert given by the Ulster Orchestra. He sat next to me and I was aware of a huge concentration emanating from him. I turned round and found him listening with his eyes. He later, after that visit, sent me an exquisite crayon sketch of Queen’s University, an institution I attended for just one year, 1968–69, an epoch-making year both for me and rather more so for Ulster. It is a place I love and to which I owe a great deal, even though I ran away from it to become an actor. By the same alchemy with which Colin’s portraits capture the face and what lies behind it, in the drawing of Queen’s he has somehow managed to catch what the place meant and means to me.

Some time passed without my seeing him. Out of the blue, he texted me to tell me that there was an exhibition of his work – Silent Testimony – at the National Portrait Gallery which he’d like me to see. I went as soon as I could, not quite sure what to expect. What I saw that afternoon overwhelmed me. It was unlike anything I’d seen before, certainly unlike anything of Colin’s. I texted him immediately:

viii Foreword

My dear Colin, I finally caught Silent Testimony on Tuesday. God knows what I was expecting, but it hit me with overwhelming force. Not having read anything about it, or even referred to the captions, I was instantly shaken by the intensity of the sitters caught in your passionate brushwork, and then became aware of – deeply moved by – the eyes, the dark reflection in the eyes, always the still centre of each canvas, gazing on the unthinkable, the unfathomable, the unbearable. Then I read the captions, which took me back to ’68/’69, when I was at Queen’s and it was all brewing, and then to ’74, when I came back with the Edinburgh Traverse theatre company and we played at the Arts Theatre as the bombs erupted all over the city and the tanks were rolling down Botanic Avenue, and then later that same day met my old chums from Queen’s, who, quietly, emotionlessly, spoke of what had happened to them and their families, the cumulative horror of it all. And standing there in the NPG, with just a couple of others in that cube of a room, I found myself suddenly shaking with emotion, welling with tears, sobbing, reliving the whole ghastly history, which is now being repeated all over the world every day of our lives. Well: thank you for reawakening my numbed humanity. It’s a magnificent show. As you know, one reaches it via the Elizabethan monarchs, aristocrats, soldiers in the Long Gallery, and I thought as I left your room, that they too had known all the above, they too were standing on the tombs of family, friends, lovers, and the whole hideous pageant continues, but that you and Holbein and co in painting them somehow manage to heal us in some mysterious way. Bravo, my friend, congratulations and salutations. You have created something truly unforgettable, indelible. A thousand thanks, Simon.

I thought I knew Colin. I didn’t.

ix Foreword

Introduction

Mark Carruthers

He calls it ‘the act of looking’. Colin Davidson sees the world through an artist’s eyes and in Twelve Paintings he explains how and why he does what he does. A painter long admired in his native Ireland, Colin now enjoys a burgeoning international reputation. His work features in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC, the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, the Ulster Museum in Belfast, and in many private and corporate collections. In his practice he is a restless perfectionist whose work ranges from portraiture through landscape to three-dimensional painting. His outsized head paintings of prominent cultural and political figures vie for attention with his vast window reflections and his Belfast cityscapes. Silent Testimony, his series of portraits of people united by their loss during Northern Ireland’s many years of conflict, has inspired and unsettled audiences from Derry to London and Dublin to New York. This huge body of work, built up over decades of dedicated endeavour, is what we set out to explore, together, in this series of twelve face-to-face conversations.

The opportunity to discuss all aspects of Colin’s practice in this book – and to illustrate them comprehensively – has enabled us to produce a unique overview of artistic output. Colin and I have been firm friends for more than fifteen years and Twelve Paintings has

1 Introduction

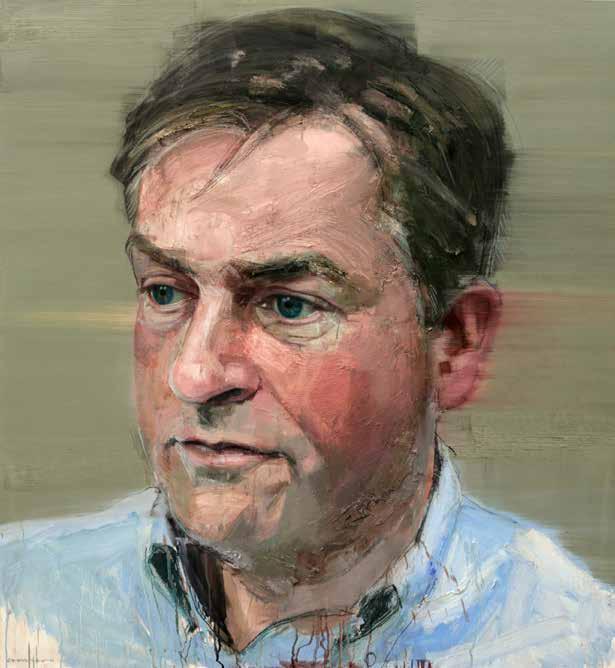

opposite

Portrait of Mark Carruthers

been a joint enterprise since its inception. We were introduced by a mutual friend when I was chairing the board of Belfast’s Lyric Theatre and Colin had just begun to experiment with his now familiar larger-than-life portraits. The walls of the newly rebuilt Lyric quickly became a favoured place for him to hang his ever-expanding series. Some years later I approached him with the idea of publishing a book of interviews exploring both his work and his world view, and he signed up without hesitation. Providing a platform for Colin to set out his thoughts in book form was, in truth, no more than an extension of what we had already found ourselves doing at various festivals and literary events. It was obvious in those encounters the extent to which audiences were as fascinated by the insights he provided into his working practices as they were by his views on art and its place in our world.

The premise for this publication is a simple one: a dozen discrete conversations, each focusing on a specific piece of Colin’s work, which, in turn, serve as entry points into wider explorations of his craft. Hence, our interview about Colin’s portrait of Seamus Heaney leads into a conversation that also touches on his encounters with Michael Longley, Paul Muldoon and Edna O’Brien. Similarly, the Duke Special portrait opens up a discussion that brings in, amongst others, Brian Friel, Kenneth Branagh and Liam Neeson. While some of Colin’s portraits may have attracted attention because of the visibility of those who have sat for him, he nevertheless rejects any suggestion that he is a ‘celebrity’ painter. The late Queen Elizabeth II, President Bill Clinton and Ed Sheeran may feature prominently in his body of work, but he is quick to emphasise what he sees as the democracy of painting portraits. His process for capturing the likeness and the personality of his subjects does not differ in any meaningful way from sitter to sitter. The pigment he puts on the cloth and how he does it, he maintains, is the same if he is painting a head of state or a little-known, up-and-coming poet.

In fact, Colin Davidson does not regard himself as a portrait painter at all. He sees elements of landscape painting in his portraits, and portraiture in his much-admired Belfast landscapes. His work is a constantly evolving mix of ideas and genres. Always on the lookout

for the next challenge, he admits in these encounters to getting bored easily and maintains he is at his most productive when forced out of his comfort zone. He insists he is rarely completely satisfied with what he produces. Willem de Kooning, Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud and Basil Blackshaw may be among his many artistic heroes, but this is an artist whose focus is fixed firmly on exploring and developing his own singular voice, and tackling his uniquely personal artistic challenges.

Colin Davidson’s imagination is what drives his expression. His artistic output speaks for itself, but these dozen conversations – each of them, I hope, engaging, heartfelt and candid – reveal an artist who thinks deeply about his role and is confident making the case for its value. In my day job I am paid to talk to people. Holding decisionmakers to account on behalf of the public is a large part of what I do. This project, however, required a very different approach. As a facilitator, my task was to tease out answers and encourage reflection, and, of course, our friendship underpinned the mechanics of the interview process. My overarching concern throughout was a simple one – to ensure Colin’s voice is properly heard.

Our interviews took place over many months and the book itself has been several years in gestation. Translating lengthy sitdown interviews into readable text is time-consuming and does unavoidably require surgery, but edits, where necessary, were always made to provide clarity and ensure accuracy. I am confident the authenticity and the liveliness of our encounters remains intact in these published versions of our conversations.

Colin Davidson is a uniquely Northern Irish painter and his sense of himself is not something he shies away from confronting in this book. His reflections on Northern Ireland’s three decades of Troubles – the backdrop to his early life in Belfast – are informed by his astute grasp of place and identity in what remains a visibly divided society. Conscious, too, of the Irish and British dimensions to his identity, he is a painter who is keenly attuned politically, something which is particularly evident when he is discussing his encounter with the late Queen and his highly charged Silent Testimony series of paintings. It is

3 Introduction

also apparent when he reflects on making his portraits of politicians –Senator Mitchell, President Clinton, Ian Paisley, Martin McGuinness, John Hume and David Trimble in particular. His observations on those encounters are sharp and insightful but never self-absorbed. We are familiar in this place with public figures who excel at conviction politics; the more convinced they are of their cause, the louder they tend to expound upon it. Not so Colin Davidson.

One key challenge we did have to confront during the project was striking the appropriate balance between sharing relevant insights from Colin’s sitters without feeling we were breaching anyone’s confidence. When the Queen sat for him in Buckingham Palace in May 2016, it was the first Northern Irish portrait of a British monarch, painted at a time when Anglo-Irish relations were at a historical highpoint. The conversation in the Yellow Drawing Room flowed freely. Much of what was said between the two protagonists in that encounter remains – and will remain – private to them, but there is still ample detail in our discussion about that sitting to shed light on the persona of the late monarch without crossing the line into intrusiveness.

Silent Testimony is another case in point. Colin describes it in our conversation as his most meaningful and most personal piece of work. He says painting the eighteen victims of the Troubles who make up the series required him to stretch himself beyond anything he had done before. The stories of loss he encountered when making those paintings back in 2014 and 2015 clearly had a profound effect on him. So moved was he by what he heard, in fact, that he decided afterwards to become a visible and forthright advocate for victims. I suggested we should record that interview not in his studio, as we had most of the others, but surrounded by the paintings in the National Portrait Gallery in London on the final weekend that the exhibition was being shown there in early 2025. It was an intensely moving experience for both of us. Colin speaks with great clarity about meeting and painting the individuals who feature in Silent Testimony, careful always to acknowledge and respect the burden of loss they were carrying with them during those sittings.

While Colin’s distinctive portraits are the most recognised and celebrated aspects of his practice internationally, his Belfast cityscapes, window reflections, drawings and 3D paintings are also important elements of his output. Appreciating why he returns every year to make at least one large painting of his home city is to begin to understand his essential sense of place. Hearing him talk through the complexities of capturing reflected and refracted light in his window paintings is revelatory, as are his insights into the foundational importance of drawing and his current explorations into the world of 3D painting. The human connections wrapped up in all of that work are what matter most to Colin, and that must be a factor in what has increasingly led to him being cast in the dual role of public conscience and chronicler of our time.

On the basis that, for the purposes of this book, Colin’s thinking matters as much as the work he is discussing, we both agreed from the outset that the text of the interviews should be given the same weight as the illustrations. The conversations link many of the individual pieces he has produced with the experiences that went into making them, though we were clear our task was not to produce anything resembling a definitive career review. How could it be that, anyway, when the artist still has, potentially, so many years of endeavour ahead of him? However, I hope it is a timely stocktake, and that our conversations reflect that.

The themes that punched through during the course of our conversations came as no great surprise to either of us. It is clear, for example, that the home Colin grew up in and the childhood he experienced shaped significantly the artist he went on to become. The seminal moment when he first realised at the age of eight that he had a talent for drawing continues to influence his approach to this day. His time at art college and the years he spent working as a graphic designer are also writ large in the narrative of his artistic development. He mentions on several occasions – and with gratitude – the serendipitous encounters in recent years that linked sitters and opened doors to career-changing opportunities.

Finally, the idea that comes around most frequently in our conversations is the notion that, as an artist, he needs the viewer to feel there is a gap in his work that he or she can fill. At its simplest, the great skill of Colin Davidson is his ability to place before us material that invites us to engage. Our participation, he is convinced, is required to complete any piece of art. It is an invitation from him to share in the moment. The art critic Kelly Grovier, in an essay published in the catalogue that accompanied the successful retrospective of Colin’s work at the F.E. McWilliam Gallery in Banbridge in 2022, says this: ‘Davidson knows that the specific details of any given painting, its scale and texture, genre and palette, are ultimately incidental to his larger aim: to glimpse through the myth of pigment and linen what it means to be here – to be alive in the world.’

Colin Davidson has a rare ability to find a voice for his subjects –whether those subjects be people, places or plate-glass windows – in paint. This book of interviews quite rightly celebrates that work, but it is also an opportunity for the artist to raise his voice and speak for himself, this time not in paint but in print.

1