7 minute read

Whirlwind: A Spirit Dancing

By Denise Lajimodiere

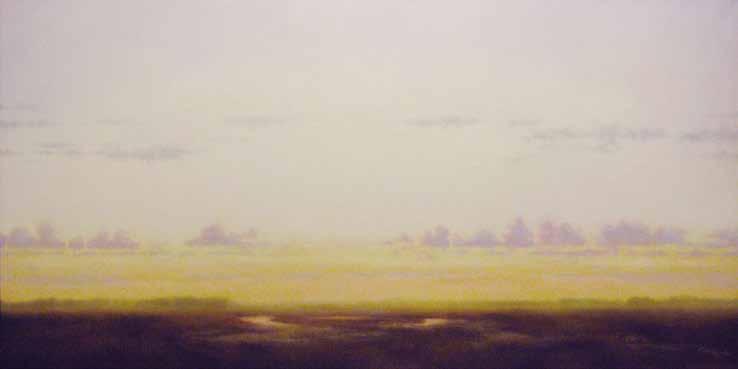

The day is hot and dry. While running on a narrow prairie trail barefoot, braids flying, kicking up dragonflies, listening to the whirr and tick of wings, loud in the thin summer heat, I am suddenly engulfed in a rotating wind, my skirt flapping wildly around my legs. The whirlwind released its grip and continued down the trail ahead of me, tall and thin, spinning clockwise. I still see it dancing for a ways before flicking its tail and disappearing.

Advertisement

I was six years old that summer day. Born on the Turtle Mountain Reservation in the north-central part of North Dakota, along the Canadian border, I spent the first years of my life in the village of Belcourt, the rolling turtle shell hills to the north, the prairie to the south. Later that summer I found myself stuffed into our family station wagon with my grandmother, brother, and sister in the back seat, and Ring Eye, our dog, curled up on a blanket in the “way back.” A trailer packed with all our meager household belongings was hooked up to the wagon. We were relocating to Portland, Oregon. Relocation was a Bureau of Indian Affairs program designed to help Native people leave the reservation and find work in large cities. Years later ,I learned it was also a program to encourage Native people to assimilate into White society. My father, a carpenter, had a difficult time finding work in North Dakota’s brutal winters, and feeding a family of six on the reservation commodity food program proved difficult. We took the “high line” road through Montana, brutal in its length and long stretches between towns. The few stops we made were for gas, while we kids fueled up on Nehi orange pop and potato chips. Dad hated stopping, even for potty breaks—we had to pee in coffee cans!

We left the plains and entered the mountains. Terrified as we climbed higher and higher, I laid as low on the backseat floor as I could, my father teasing me for years, saying, ‘I thought the engine was knocking, but it was your knees!” Several days later, we arrived in Gresham, a small town outside of Portland, near Mt. Hood. My uncle and cousins were there to greet us and offer temporary housing until we could get on our feet. Also there to greet us, were tall fir trees that shut out the sky, sun, and horizon. The damp, dank, mildew smell everywhere was overpowering. Dark grey clouds hung low overhead. That first night in Oregon, the nightmares began, waking me up at night, screaming in terror. Horrifying monsters chasing me, Kookoosh under the bed trying to grab me. Night terrors that seemed never ending and relentless.

As the only Native in all-White schools, I was subject to teasing, being called “squaw,” “stinking injun;” and I was jerked around the playground by my long braids, chased home with crowds of kids throwing dirt clods and pine cones after me. By fourth grade, I had stopped speaking, refused to go to school, and was sent to see a child psychologist, a kind gentleman who let me play with dolls and toys in a sandbox. I eventually began speaking again, but also became a fighter and fought my way through the rest of grade school and high school.

Throughout the fourteen years living in Portland, we would often travel back to the reservation, and I would plead with my parents to let me stay with my cousins and my grandfather. I loved their lilting singsong patois, a mixture of French, Cree, and Ojibwe. The people on the reservation looked like me. Having been literally stolen and sent to boarding schools in the 1920s, my parents refused to be separated from us kids. I vowed I would return to the reservation to live as soon as I could.

After completing my sophomore year at Portland State University, I saw a flyer advertising a Northern Plains Indian Teacher Corps Program at the University of North Dakota where I could be stationed on my home reservation. I applied and was accepted. I packed all that I owned in an old, worn, leather suitcase and dragged it through downtown Portland to the train station, my arm lengthening along the way from the weight—no wheelies in those days.

Another Teacher Corps intern and I rented a small house in Dunseith. I was home. I was fulfilling a life’s goal of working on the reservation as a teacher to the youth of my tribe. After years of city living, pollution, concrete jungle, and heavy traffic, I reveled in the vast emptiness of the plains, the beauty of the Turtle Mountains covered in aspen, bur oak, willow, and freshwater lakes. That first summer home I experienced North Dakota thunderstorms that shook the earth: massive flashes of light rent the air, followed by explosive booms, torrential downpours, and then, just as quickly as the storm came on, it was over, so different from the fretting gloomy veils of rain that could last for weeks and weeks on end in Portland. I wanted to fully experience a blizzard, so I bundled up and went out walking in a great December snowstorm, tribal police pulling up beside me yelling that the wind chill was fifty below! And did I want a ride home?

I sat in teaching lodges listening to elders. I gave Grandma Great Walker tobacco and asked to be given my spirit name. Through ceremony, I received the name Thunder Cloud Woman, a name she had dreamed. “I saw you on top the high thunderclouds.” I began dancing, driving to powwows—celebrations— throughout the state, in love with how the wide prairie sky ramped up and over my truck and landed behind me. The smell of sage and sweet grass wafting in through my open windows was intoxicating. On a warm August night, achingly beautiful hand drum round dance songs brought out the northern lights, jiibayag niimi’idiwag, over our tribal powwow grounds, a healing power, our ancestors dancing with us.

One day, a dragonfly hovered in front of me while I was dancing at the Red Lake celebration. We were dancing for the spirits of the children that had been killed that year in a school shooting. It looked at me with its huge eyes, eyes that have 30,000 facets; eyes that provide a nearly 360-degree field of vision that can detect movement sixty feet away, eyes I felt were looking right through me. It spun around and joined other dragonflies dancing above our heads. Ojibwe spiritual beliefs tell us the spirits of our ancestors are carried to earth on the backs of the dragonfly. Perhaps the children joined us that day.

Dragonflies, obodashkwanishi, are considered holy creatures with healing powers. Elders counsel us, “If a dragonfly lands on you and is moving its feelers, you are being cleansed.” Dragonflies are the world’s fastest insect and are capable of rapid evasive action. Warriors were drawn to them because of their quickness, and when they fly near the ground, they create dust that makes them hard to see, thus decorating their shields, clothing, moccasins and bodies with dragonfly designs. Dragonflies are also “of the women.”

We carry our babies surrounded by one of the four sacred waters. Dragonflies come from another of those sacred waters as nymphs that eventually undergoes a metamorphosis. Elders tell me that dragonflies are the “little whirlwind of the People.” They can be seen formed into funnel-shaped swarms, moving across the prairie. Whirlwinds, gizhibaayaanimad, often appearing on sunny days, are believed to have sacred power by plains tribes. They are considered literally to be stirred up by the rotation of dragonfly wings.

Nightmares have long ago ceased. Living in my beloved North Dakota, I have absorbed the healing powers of Thunder Beings, Northern Lights, dragonflies, and whirlwinds. Driving across the plains from my university job in Fargo to the Turtle Mountains, whenever I see a whirlwind, I’m engulfed in memory of that day long ago. The warmth of that day, the wind on my arms, my cotton skirt billowing, hot and cold bits of air encircle me as I return to that magical moment when my spirit danced with a whirlwind stirred up by dragonfly wings.

Denise Lajimodiere is an enrolled citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and an assistant professor in North Dakota State University’s Educational Leadership program. She has a published book of poems entitled Dragonfly Dance.