13 minute read

Šhuŋg nağí kičhí okižhu: Becoming One with the Spirit of the Horse

By Dakota Goodhouse

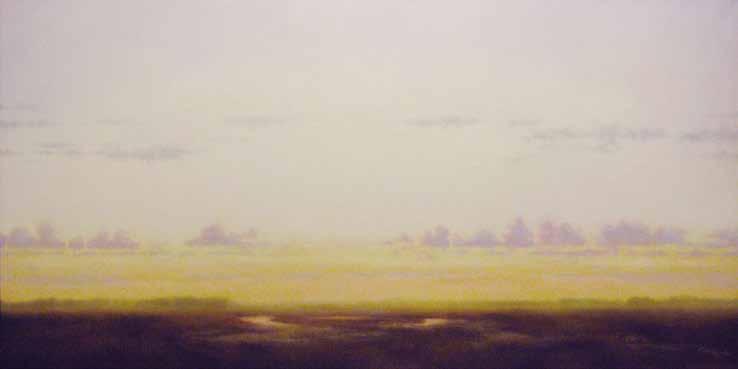

I met Jon Eagle at Sitting Bull College just outside of Fort Yates on the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation. It was a bright spring morning: a few distant clouds hung in the sky, not enough to provide shade, nor heavy enough to promise rain. Meadowlarks flew boldly through a light breeze, carrying short, sweet songs of courtship.

Advertisement

Jon had taken me to his niece’s land just south of Fort Yates near the wačhipi (powwow) grounds. We followed a short bumpy dirt road, more trail than road, and the pickup kicked up a small cloud of dust that dissipated with the quiet wind. Suddenly we were there, where we saw his horses grazing along the meandering Akičhita Haŋska Wakpa (Long Soldier Creek).

The sun shown clear and true, but not hot, at least not yet, not in the spring in the land of forever. The snow had all but melted, and only in the shade of the bends of the creeks was compacted snow still holding out. Tips of trees and ends of bushes bore small tight buds, a sure sign that spring had arrived.

On the drive to the horse range, we spoke of family lines. I had heard Jon refer to a lekšhi (uncle) of mine as lala (grandfather). To one another, however, we addressed each other as théhaŋšhi (male cousins), which seemed comfortable as we are closer in age than in generation. Jon possesses practical, experiential, traditional knowledge, handed down to him, and he’s quick to acknowledge where he acquired it and from whom.

Jon brought me to the horses to talk about them in front of them; it was far better to speak about the return of traditional horsemanship on site rather than in the confines of an office. The talk bounced between ancestral or genetic memory, traditional stories of the horse, Lakĥóta societies of history and the recent Black Spotted Horse Society, and traditional horsemanship, which is based on developing a relationship between horse and rider rather than the western dominion of horse-breaking.

We stepped out of his pickup and onto the floodplain of the creek, a gentle steppe above a wandering waterway that has quietly shaped and cut a path at the bottom of the valley floor over thousands of years. Horses circled around the little steppe looking for fresh green spring grass and found it shooting up through last year’s brown remains.

Jon stopped us perhaps twenty feet from a mottled brown-and-white pony as we continued to exchange pleasantries about the day. After a while the mottled pony came over and shared an affectionate greeting with Jon, and introduced herself to me. I held my hand up and she sniffed and huffed at me for a few minutes and tolerated the touch of my palm to the bridge of her face. “When a horse shares breath with us, that’s a sacred thing,” explained Jon. “They’re sharing their spirit with us.” The mottled pony made a final quiet noncommittal huff of me, took a few steps back into the grass, and put her nose back to the ground.

In the cool breezy morning air under a now cloudless sky, our conversation began in earnest about the horse and the return of the practice of traditional horsemanship by the people of Iŋyáŋ Wosláta (Standing Rock).

“The horses have a language of their own, and a natural social order,” explained Jon. According to him, with domestication of the horses, humans have interrupted the natural order.

Jon described the pony that had come over and introduced herself to me as “untouched”: “She’s never known a halter, she’s never been saddled, and I’m trying to preserve that in her. Indeed, there’s a spirit of equality that emanates from her as though we’re brother and sister, rather than man and animal. It feels as though she would let me ride on her back at her prerogative, rather than mine.”

Jon says that he looks for a telling quality of spirit, a gentle quality found in their eyes. "It tells me that they're intelligent and trainable, and that I can develop a relationship with the horse,” he says. Much more than a domestic work animal for breaking, pulling and riding, Jon thinks of horses as friends. When people ask him how to learn how to ride a horse, he says that’s something that he can’t teach. In fact, he insists that one needs to develop a relationship with the horse. It’s the only way to learn to ride.

This philosophy is intrinsic to Jon Eagle’s life. He was born into a horse-ranching family who rode along the Snake and Grand Rivers in South Dakota. In those days, not so long ago, before all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), ranchers depended on horses to ride the range and cross the steppe. “We wanted what we called an ‘all day horse’— a horse that could go all day and could get the job done,” Jon said.

Jon’s children take an active role in horsemanship. They water and feed the herd, venture into the field to repair fence line, and volunteer for anything that puts them in direct field contact with their horses. They ride some of their horses and are equally practiced in saddle and tack, as well as bareback riding. Jon doesn’t push them into the field, but rather lets his children determine their own time with their horses. “I want them to enjoy this. It’s a way of life,” he said.

When I asked Jon if he rode bareback, his answer led us into a discussion about western horsemanship and traditional Lakĥóta horsemanship. “I can’t ride bareback,” he said, and then recounted an incident back in 2000 when he rode a two-year-old mare all summer and then put her away for the winter. When spring returned, he corralled her and when he rode her, she “clicked,” doing everything he wanted as though he had ridden her only yesterday. Enthusiastic about his mare’s recall, he took her out in the field where she began to behave unfavorably. Thinking that he had to “correct” his mare, Jon directed her to a run.

“I was five eleven when I started that day and was five foot ten by day’s end,” Jon recalled. “I had shattered my pelvis and fractured my back in that ride,” he recalled, with a distant gaze in his eyes that told me he wasn’t just looking over my shoulder down the dirt road, but was looking back in time. The incident humbled Jon. He was raised as a cowboy and trained to have dominion over the horses, to break them. “I realized that our cowboy way of horsemanship was disrespectful and abusive. We broke them and they resented it.”

While Jon was laid up in recovery, he began to rethink his approach to the horse. He picked one of Monty Roberts’ books about natural horsemanship. Roberts, who is known as “the horse whisperer,” originated the term “join up” for the way a trainer and a horse can engage in a voluntary and mutual relationship.

Once he was healed up, Jon brought his horse into the corral and gave her plenty of time to read his body language. It wasn’t long before she became comfortable with him again and was willing to approach him after a short time.

Jon’s théhaŋšhi (cousin), Greg Holy Bull, in Red Scaffold on the Cheyenne River Sioux Indian Reservation told him the Lakĥóta story of the horse. Jon graciously shared it with me:

*Note: According to the story as Jon heard it, the enemy from whom the Lak óta took women and horses were Spaniards.

The natural approach to the horse, the singing and allowing the horse to come forward on its own accord, is the method the Lakĥota came to call Šung Naği K’sapa, the Wisdom of Spirit. The spirit of the horse senses the natural order of the world and the natures of men, and they respond. In the natural world, they know when thunderstorms are coming. Horses read the body language of men, and determine if they will get close or allow humans to come close to them.

Jon doesn’t teach people how to ride horses or master horses. He teaches people how to have relationships with horses. He passionately recalls the lessons of the Lakĥota people and how they look at the horse as their own nation, the Šung Wakaŋ Oyáte: That everything out there is a nation unto itself. That everything has a spirit.

This natural and spiritual approach to horsemanship has allowed Jon to harness and ride his horses without going through the traditional “breaking” or bribing of the horse. “I can actually get them to walk over and stick their head in that halter, and it’s all because we’ve established a meaningful relationship based on trust,” Jon explains.

Jon has carefully examined the meaning of the Lakĥota word for horse. A search online, and in person among various Lakĥota communities have yielded different words and even different meanings. Šhuŋka Wakáŋ is often given a contemporary interpretation as “Holy Dog,” but Lakĥota elders render the term in the traditional sense as “pitiful,” not as in the western meaning of downtrodden but as “beautiful, innocent, and pure.”

Part of the Lakĥota word for horse, wakáŋ, reaches back to creation. When Iŋyáŋ (Stone) let his blood flow, his blood (which ran blue and became the waters of the world) was Kaŋ, full of energy, with the potential for destruction and to give life. When the Lakĥota say Wakáŋ, it means something with energy, energy with good and negative potential. Taken altogether, Šhuŋka Wakáŋ means beautiful, pure innocence with energy.

Jon described traditional horsemanship with the Lakĥota phrase Šhuŋg nağí kičhí okižhu, which translates as “becoming one with the spirit of the horse.” The Lakĥota people say it is a way of life, and breaking a horse or having dominion has no part in building a relationship with people, nations, or creation. Jon notes that with a natural spiritual relationship with horses, the horses put people in a place of honor, čhatkú, a middle place between the natural authority of the mares and the sires. It is a place that is earned by trust, which is not so different from how one earns friends and holds them in esteem.

Before we left the horses, Jon related one more story, which had come to him from Mr. Albert Foote, Sr., who heard from his Lala (grandfather) on the origins of the horse:

The sun shone true and fair upon us; a few clouds hung high in the azure sky and rambled slowly eastward. I don’t wear a watch and I didn’t see one on Jon’s wrist either, but the growl in my stomach let me know it was about midday. The horses had wandered across Long Soldier Creek to graze on the fresh, dark-green grass there. Jon had finished his coffee long ago, and now he sat patiently on the gate of his pickup and gently tapped his empty paper cup against the palm of his hand.

For a moment, I imagined Jon in another time, sitting on the back end of a travois, tapping the rim of a hand drum, about to break into song. There are no roads in this vision, only the telltale ruts of the travois that show how we arrived here. The lofty clouds are the same that floated here three hundred years ago, in a sky the same blue, above a quiet wandering creek just as hauntingly quiet then as now. The same breeze grazes me and cools me.

I am brought out of this reverie the moment we step into Jon’s pickup. We barrel up an incline back onto the lonely dirt road that brought us here. It’s my turn to open the barbed wire fence gate. The dirt road gives way to gravel, then blacktop. We drive back into town and into the twenty-first century much as the efforts of traditional Lakĥóta people also carried the tradition of the horse culture into a new age.

Dakota Goodhouse is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Goodhouse is a theologian by education and a public historian by trade. His published works include chapter 4 of The Year the Stars Fell: Lakota Winter Counts at the Smithsonian and articles in the First People’s Theology Journal, Vols. 2 & 8.