5 minute read

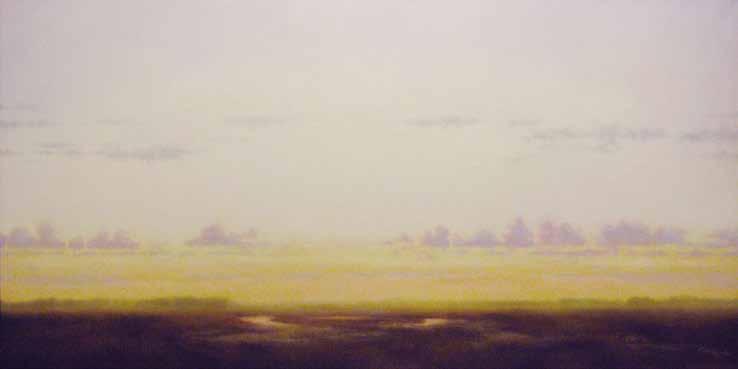

Slant of Light

By Janelle Masters

Stepping outside the house in Niobe one winter evening, I looked west to the escarpment hills ten miles away and saw the prairie snow drifting to the south, rolling fast and red. The cold North Dakota sun was setting, making the snow look as if it were on fire, drenching it with color. Through the blowing snow, I saw long-eared animals at least ten feet tall bouncing on their hind legs in great arcs south with the wind.

Advertisement

I backed into the house, awe-struck, and rushed into the living room. “Mom,” I said, “you were right. There are kangaroos in the hills.”

Dad, Elizabeth, and Cooper (my sister and brother) all laughed as they had laughed at my mother a few minutes before when she’d said she had seen kangaroos outside. But one at a time, my family went out to the porch and gazed west toward the Missouri Escarpment where my grandfather had homesteaded at the turn of the twentieth century. Each of them stood and looked over that frozen, rolling, scarlet expanse, then came back in, shaken.

I studied my father’s face when he entered the house. His eyebrows leaping up and down was a sure sign he was tamping down some emotion. “By God, I think they are kangaroos,” he stammered.

And I remember ten years later when I was in high school, at a time when I thought all mystery was gone from the world and certainly from Niobe, population 33, I stepped outside again onto that same porch, ten o’clock at night, and looked up into what I assumed was going to be a black sky. Green and violet curtains lined with silver hung in the sky. Not a speck of sky was unadorned. Hypnotized, I walked into the middle of the yard, my head upward. Every second, the curtains flowed into different folds and hues of purple, magenta, burgundy, lime, and forest green.

I ran into the house to my mother’s bedroom. “Mom,” I said, “you’ve got to see this.” There was no one else in the house to rally. Dad was gone on one of his long disappearances, Cooper was in the army, and Elizabeth was married.

My mother looked up, startled, from the bed. “What, Zan?” She put down the True Story magazine she’d been reading, her brown eyes widening in fear as if I were about to announce some terrible calamity.

“The whole sky is lit up.”

“Oh, you mean the Northern Lights?”

“No. No. I’ve never seen anything like this. You’ve got to come out and see this.” I started looking around for her bathrobe.

“Oh, Zan, I can’t go out. My feet are so bad I could barely get into bed tonight.” She had arthritis, the family disease. If one looked closely at the black-and-white figures in the family albums, one could see twisted hands folded into one another and crooked ankles for generations back. I sat her up, put her white chenille bathrobe on her, and helped her stand. Then I picked up my mother and carried her outside.

I set her down carefully and stood behind her, steadying her as we gazed into the sky. The curtains had changed into caverns and cliffs of purple and gold, the shimmering lights casting sparks onto my mother’s face.

“Zan, I can’t stand it,” Mom whispered. “Take me back in.” I lifted her and carried her into the house. As I tucked her in bed, she said, “You know what I mean, don’t you, Zan?” I nodded and walked across the hall to my bedroom.

I rested on my bed for awhile, then got up and went outside. The lights weren’t as intense as they’d been a few minutes before. I sat down on the granite rock on top the cistern to watch for a little longer. I thought about what my mother had said. Sometimes in ripe summers, I would run through wheat fields and then lie down so I could see the sky through the smell of grain. But I couldn’t bring the beauty far enough inside. I would cry, my fists pressed against my chest. It wasn’t the cold and pain that my mother couldn’t stand that night. It was the beauty.

Later that same year, I was waiting out in the yard for the school bus to take me to Kenmare High School, six miles away. I was listening to the mourning doves cooing in the lilac bushes when I looked high into the eastern sky and felt the hair on my neck prickle, for I looked into a misty town hanging in the sky over Niobe. A ghost town that was a duplicate of Niobe. Two grain elevators loomed over the rest of the spectral buildings, and a few cars trailed down the foggy main street. Science would call it a mirage, a superior image caused by light rays reflected off colder air below it, but for me it was a ghost town, a precursor of the future.

The honk of the school bus shook me out of my trance, and I stepped into the noisy, hot vehicle. Making my way down the aisle, I craned my neck for another look, but the town was fading. When we turned around in the yard and headed east, I seemed to be the only one who noticed that we were heading down the disappearing main street of a phantom prairie town.

Years later, I would understand perfectly when I read Libby Custer’s description of her husband’s final departure from North Dakota only a few miles from where I now live in Mandan on the Missouri. Marching toward the Little Bighorn, Custer and his troops rode under another cavalry, ghostly white, galloping above them in the sky.

The house and Niobe are so submerged in my psyche, I seem to think and dream almost constantly about them, their miracles, their tragedies, their losses. But then, what can one expect from a town named after a woman who lost all her children and eternally mourns? And a place whose slant of light and distance transforms jackrabbits into kangaroos?

Janelle Masters is currently the dean of academic affairs at Bismarck State College. She taught English at BSC for twenty years. She is originally from Niobe, North Dakota.