4 minute read

North Dakota Through a Poet’s Eyes: Poems by Bill Schneider

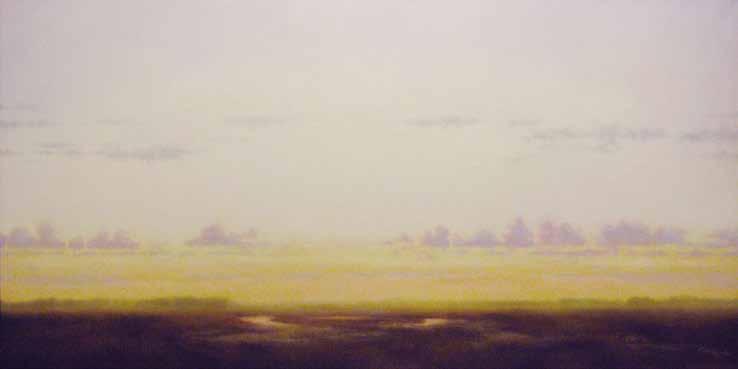

David Boggs,South Central Storm. Oil on linen, 36” x 36”

Bill Schneider has poems published in The Atlanta Review, The Southern Review, Northwest Review, Folio, and Cottonwood among others. He was the co-winner of the 2001 Grolier Poetry Prize and winner of the 2002 Kinloch Rivers Chapbook competition. He teaches writing and literature at Concordia College, Moorhead, MN.

Advertisement

BUS

By Bill Schneider

A man asks off at Island Park, steps down,

struggles over the snowplow bank

at the not-quite corner where we stop.

Then we rattle down the street, down

its furrowed tracks of graveled, salted ice.

An early moon floats behind the bare-limb trees

and street lamp crooks, above

the high dike hill rubbed slick

by tubes and boards kids slide down on.

I walked there on Saturday, frisky and fresh,

luxurious in the spring-like swelter, in the dry,

clear light we had that day, and I marveled at

the yellow hats and boots, the red canvas coats,

the bright green leggings, all the kids

trudging up, sliding down. It was hard though,

seeing kids like that, but it was the fathers

who got me most—on sleds behind,

or running down shouting watchitwatchit,

or the one who knelt in the snow to zip

a snowsuit leg, his child’s mittened hand

familiar at his neck. I’d like that too. I’d cherish

the zipping, linger long with it—to sense

that small hand—its familiarity, its balance

and trust. Then, sledding done, I would have shown

that kid the tunnels squirrels make

through deep park snow, or how

the river freezes above its bouldered falls

like a shell, and later, how I fix a pretty good

grilled cheese. But still, tonight, even without

those things, I feel fine—I do like buses—

moments inside that are just for seats, for

sitting down, for letting bus be bus,

and for the jouncing over ice and rut that shakes

a heart—for the pain that might slip out.

First published in Louisiana Literature

FEBRUARY CROWS

By Bill Schneider

The bus ride home—windows rimy, heater weak.

An early dusk, and dense, gray clouds.

Snow again tonight. And in the cold, in

the muted light, crows circling icy trees.

-

A stop at the Seniors Home, and a man

climbs on, his face crimped and blank

beneath a John Deere cap, coat snapped tight.

He stares at the puddled, rubber floor,

-

his fingers kneading thighs through faded denim,

his boot heels lifting, dropping, like a clock

wound low. Or a heart.

I get off soon after, and after stir-fry

-

and rice, and after washing up, I smooth

Dakota on the kitchen table, trace

the blue and the straight black lines

from Fargo out through flat and white

-

to Cando, Mohall, McClusky. I picture

homesteads battered and lost—A-frame, silo,

shed and gate—breached by snow and wind,

splintered white and dry like husks of sheep.

-

Later, in bed, warm, and blanket-heavy, that man

comes to me again and I think that if I’d

been him, on my way to Cash Wise or K-Mart,

or just on for the ride around, I—I hope—

-

would have pried a window open, or with

an elbow, or with the red axe beneath

the driver’s seat, smashed the window into little jabs

of shattered glass—no matter blood

-

or cops or cold snow drifting—then

mustered in those crows and commandeered

their purple-black and pounding wings

to fly me, fly me up, fly me back.

First published in Confluence

FARGO ELMER FUDD

By Bill Schneider

One of my students wrote

a poem about her father, and how, in a persistent

rage, he’d rigged shotguns to dispatch the rabbits

that were stripping his garden. At the time I thought,

well, that’s extreme, and too, I was a liberal

about the rights of rabbits. But then I bought

a house. And now, though I don’t grow vegetables,

and though I can’t name my hedge plants

to save my soul, or my flowers, except

the tulips I bought in Amsterdam, I don’t want

my nature eaten up around me. There are laws

in cities, even in Fargo, so I haven’t

bought a shotgun, though I did buy a trap.

But the door seemed tricky, and I’d’ve had

to have toted it, with the rabbits, far enough away

to discourage Peter-come-homes.

But, relax, you say, calm down. Why

so agitated? Why so shrill? Well, if rabbits

can eat with impunity, then anything,

everything can be eaten—my guitars could, or

my confidence, or my IRA, or my

Civic even (just last week the oil change guy said

I needed the injectors cleaned): the world

is at risk, nothing’s for sure. So I bought some

chicken wire, spent Saturday making

a little rabbit proof fence, a twelve-inch strip around

the bottom of the chain link out back. But after

a day of unrolling the wire, of snipping it

into long, tie-able strips—the snipped, sharp

ends pricking my hands and wrists like Sebastian’s,

and just as bloody—then twisting it tight

to the fence’s diamond squares, I realized—surprise—

that this is North Dakota, and that winter

would come. And if the snow is deep enough

again this year, and with a good strong crust on top

like last year, the rabbits will hop

across that snow and squeeze through the links

above my proof. And eat. Which is why I finally

understand: there is no hope, no future. I’m

being eaten alive, and I have been, all of my life.

First published in Wisconsin Review