6 minute read

The Dakota Project

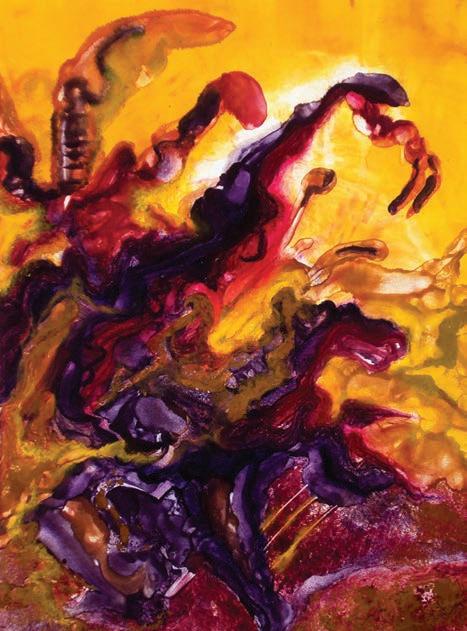

Cover Image: Rupture of the Psyche by Michelle Lindblom 52x46 acrylic on canvas

By John Helgeland

Advertisement

All too often ethics is taught, or conceived, as a private exercise dealing mostly with individual rights and wrongs. Is it right to tell a lie? What if a lie protects someone from an unjust authority as happened many times in the Third Reich? Can I tell a lie, a white lie so called, to buck up a person with sagging spirits? Does “finders keepers” permit me to keep anything I might find along the road, or in a public washroom? These are examples of individual ethics, involving at most one, two, or three people.

But let us turn our thinking to the category of social ethics. Here the questions do not relate to a single person’s virtue or vice, but to building and maintaining the commonwealth. Ideally, this exercise takes place under the auspices of democracy. If the ethical decisions affect large numbers of people then large numbers of people must be involved in the construction of a social ethic. Americans do not take kindly to the model of a benevolent dictator or any other political model that squelches peoples’ individualities. On the one hand, we are an independent people; on the other, we must surrender some of that independence in order to get something done, but it will not do to have policies dictated to us in order to make that happen.

The democratic process gets the ball rolling. Here at the Northern Plains Ethics Institute we think about this issue frequently. In order to have many more people come together to form a decision, we ask those who come to us to consider two questions: “What kind of a world do we want to live in?” and “How do we propose to get there?” There are a number of elements involved in these pedagogical questions—some obvious, some not.

First, the pronoun “we” is employed in both these questions, not “I.” “We” means society, or participants, or those concerned. Second, the expression “we want” implies imagination. Our imaginations need to be exercised, developed, or focused; it means to dream going beyond the present and then sharing that vision with others. Perhaps we could dig out a concordance to see if this appears somewhere in scripture but here it is, nevertheless, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” Ethics involves what should be, not what is or was. It implies a vision of a shaped future.

So where is it that visions arise? Are they not some evanescent intrusion into our consciousness? Perhaps in some cases that happens, but more frequently, visions are a mix of our thoughts with those of other people. They develop in community, such as programs presented by the North Dakota Humanities Council.

Appreciation for the humanities is as important to our society as knowledge of economics, law, technology or management. It would be impossible to answer the question, “what kind of a world do we want to live in?” without taking into consideration philosophical questions of justice and community, historical examples of well-ordered societies and the forces that undermined them, or visions of a better world created in literature.

These themes then must be connected with the Dakota Project. The entire state of North Dakota has been bombarded for the last year with reports of all the dislocations connected to the oil boom. Most of these problems must be addressed elsewhere. One salient fact, however, is that oil is bringing to the state resources beyond anything we have ever enjoyed or imagined. What is the most equitable way to deal with this windfall? What visions will this new wealth make possible? And who is it that will decide how it ought to be distributed?

The Dakota Project’s proposal is to invite people from across the state to join in making suggestions. Our procedure will be to start with town hall meetings on various topics. Over the years, the Northern Plains Ethics Institute has conducted town hall sessions on capital punishment, education, technology, business, and statistics. The topics we propose for the Dakota Project are agriculture, technology, finance, knowledge transfer, and culture. Each meeting will begin with the help of various authorities or panels of authorities to spark the conversation. The situations of North Dakota must be understood in global perspective. Agriculture, by way of example, in fifty years may become more valuable than oil since the world’s population is predicted to grow by another billion by then.

The goal of the project is to advance many areas of the state’s endeavors. It is also to bring together interested citizens from across the state, because one major theme of the Northern Plains Ethics Institute is democracy. As with so many in our society, it is our perception that democracy is a threatened species. We have only to mention several developments in the last generation that have diminished the democratic process—money, vested interests, control of political parties by fewer and fewer rich people, and the power of business to the disadvantage of the middle class.

Another perspective that needs to be counteracted is that government should or even can provide the leadership in society at every level. One result of such thinking is that the population at large feels that its contributions to a civil and creative society are not needed, perhaps even not wanted. We would not suggest that government at various levels doesn’t makes valuable contributions, some that only the power of government can accomplish. But while government is necessary for a well-ordered society, is it sufficiently creative to meet the demands many see on the horizon?

The Institute for American Values finds that uncivil discourse is a powerful detriment to an open and free society; this treatment of fellow citizens in public causes many to withhold contributions that would benefit the entire culture. The present state of political conduct alone should prompt many to worry whether our nation, our culture, is headed for collapse.

Dare we hope that North Dakota can escape the uglier manifestations of these problems? Maybe it can even lead the way so that even the nation can join with us in a polity of creativity. Perhaps the small population of North Dakota is a blessing in that we know each other better than citizens of large states. Already this state has had an astounding record of creativity and innovation that must be an encouragement to further doing experiments. One example of such daring is the institution of the Group Decision Center (GDC) at North Dakota State University in Fargo. Supported by Provost Craig Schnell, this is a series of computers linked by decision-supporting software. This laboratory does problem solving, brainstorming, and statistical analysis to name its most salient features. Since all input to the system is anonymous, the timid need not fear exposure, blustery people are put in place, and everyone takes credit in the end for a successful outcome, of which there have been many over the years. Indeed the GDC has helped greatly to spare meetings of uncivil discourse while it amazes the participants what can be done in concert. Imagine that: technology in service of humanity.

Clearly we are in the process of the development of this project. We invite the participation of any who share our concerns. A number of influential citizens have already expressed interest in this project and are willing to make contributions to it. For the present, let us say how fortunate we are to have the interest and support of the North Dakota Humanities Council as we begin the initial stages of our work. Let us dare to make a difference.

Dr. John Helgeland is a professor of history and religious studies at North Dakota State University and the director of Northern Plains Ethics Institute. Dr. Helgeland was instrumental in the formation of the Northern Plains Ethics Institute (NPEI), as well as the Group Decision Center (GDC). His key area of interest is the connection between religion and violence.