12 minute read

The Chance to Stay Home

By Jessie Veeder Scofield

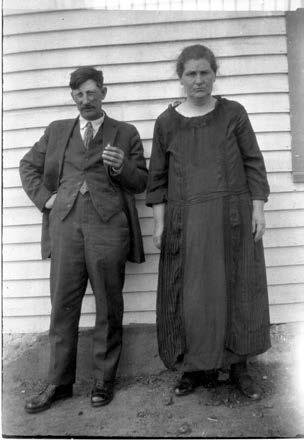

He sits at the kitchen table as I fill up his coffee cup, his overshoes dripping mud on the linoleum floor, wool cap pushed up off of his ears, his neckerchief loosened. It’s a beautiful morning in western North Dakota, and my father has been outside moving hay bales from the fields to the barn in a tractor that has been used for the same type of work year after year for as long as I can remember. We talk about the weather as he stands up and looks out the kitchen window that faces the red barn and the corrals below the house. I imagine him having done this a million times before as a young man growing up in this house.

Advertisement

But he’s a guest in this house now, having moved away from the 3,000 acres of ranchland on the edge of the Badlands in North Dakota when he was eighteen to grab that education his father made him vow to get. An education that would help ensure there were other ways to make a living besides ranching.

My father returned with that education, first in the early 1980s when he was twenty-seven with a wife and two children, when his father was still alive. He bought some land down the road and put in a house, took a construction job and helped his father run cattle. But it wasn’t enough. A lump hits his throat each time he talks about the day he had to pack us up and move to eastern North Dakota where there was a living waiting for my mother and him.

“It was the worst day of my life,” he recalls. “Saying goodbye to my parents, giving up on the idea of living here and raising my family. I can’t imagine what it was like for them to wave goodbye to their grandchildren, not knowing if there was a chance we would ever come back.”

Five years later, after his father died, we were back at the ranch and here to stay. I was six years old, and just as this landscape was in my father’s heart, it was also in mine. I would sit next to him in the pickup on cold winter evenings feeding cattle in the dark after he got home from his job in Watford City thirty miles away, and I would ride horse next to him and my grandmother on warm summer evenings moving cattle from one pasture to the next. I couldn’t imagine another life. I vowed I would live here forever.

But as a young child I had no idea what it meant to take on the responsibility of being the fourth generation on my family’s nearly 100-year-old homestead. And no one could foresee how different my experience would be from my father’s, moving back home at twenty-seven.

I fill his coffee cup again as we sit in the house where he grew up, where his parents lived their lives. My house.

Yes, I moved back here a year ago after making the same promise to my father that he made to his. It was always my dream, but I am reminded every day of the changes that had to occur to make that dream come true. I am reminded when my husband pulls on his boots and leaves our yard before the sun comes up to get to his job, maximizing the production of the oil wells that now dot the landscape. And we are reminded this morning as the rumble of trucks driving back and forth from the three oil rigs behind this old house replaces the silence that once was the backdrop of the landscape.

But some things have stayed the same, like the big oak tree where I married my husband; the pink road that leads to our house; that red tractor and my father’s deep-seated commitment to his home and community.

The latter is true because the same man who taught me how to ride a horse and fix a fence hangs up his cowboy hat each morning to step into the role of director of economic development in McKenzie County, the largest county in the state with major play in the oil activity in western North Dakota. And although Gene Veeder, my father, has been in this position for nearly twenty years, nothing could have prepared him for the changes that would occur due to new technology that allows oil to be extracted from the Bakken Reservoir 10,000 feet below the surface of the land—the land his community has been built upon.

In his role, he has become the go-to contact for direction on tough matters needing solutions. With a current count of 50 oil rigs in McKenzie County alone, each creating 120 direct and indirect jobs, he works with his board of five county commissioners, along with members of the city council, to examine the repercussions and impacts this booming industry has on the community.

It’s difficult to explain what this means to a man who, just ten years ago, was working diligently to come up with innovative plans to help recruit new businesses and residents to a county with 2,861 square miles and only 6,000 people—the same amount of people as there are new oil-related job opportunities today.

“I was here when it seemed like nothing was going to happen. It seemed like everything was happening every place else in the world,” he said. “For someone in my position, this is one of the most exciting things you could ask for.”

“Exciting” is my father’s optimistic synonym for a task that is equal parts thrilling and challenging. Each day he gets dozens of calls from people from all over the country looking to start a new business, relocate to the county, pick up an industry job, or develop a property into a motel, an apartment complex, a restaurant, or a daycare facility. Many of those voices on the other end of the line are coming from desperate situations, situations where they have lost jobs, development has ceased, and houses have been foreclosed. Many people drive to Watford City on a hope that they can meet with someone like Gene Veeder who will help them find a new direction or a new opportunity. But in a town like Watford City that has grown from 1,400 residents to an estimated 6,000 in just five years, the answers aren’t black and white.

The growth stems from an industry that is moving at an unprecedented pace and the most immediate solutions simply are not immediate enough. Housing, and the infrastructure that supports it, are two of the biggest challenges at the helm of McKenzie County’s vision for a community that one day will not be solely dependent on one industry for prosperity.

And so it starts there. In order to grow and maintain a population you must have adequate accommodations that begin with permanent housing and continue with quality school systems, healthcare, and service industries, all which are being stretched to their limits as people flock from all over the country for work and opportunity.

With a serious concern about preventing landlords from taking advantage of incoming workers and an equal concern about current, non-oilfield workers being priced out of their homes, he is in constant contact with housing developers every day. His hope is that more projects like the newly completed 1,000- unit housing development will come to fruition. He is currently talking with two such developers and he keeps his finger on the pulse of progress with an end goal of adequate permanent housing plans to help entice development of retail and service businesses and school and healthcare system expansion—major leaps that will keep new and existing residents here for the long term.

“Right now, there are growing pains. There are frustrations. I feel them too.” I hear my father say this every day. Then I see him tap his fingers on his desk and ask that people not give up on their community based on the last five years of change.

Change like the constant oil field-related traffic that wears down county roads and state highways, kicking up dust near farmsteads, and altering the way local people have grown accustomed to traveling.

“The traffic, getting in and out of the community and moving around within the community, seems to frustrate people more than anything,” he observes. And he lives it, driving thirty miles to town one way every day.

It’s an issue that community leaders like my father had in their line of sight ten years ago when they began the Highway 85 expansion project known as the Theodore Roosevelt Expressway that would turn the highway from two-lane traffic to four-lane all the way from Canada to Texas. They had a vision for growth before they could see it coming down the road.

“It is evident now that we were on the right path,” he says of his community’s involvement with the highway expansion. “Now it is about building and maintaining and getting those wells on pipelines to help ease the traffic.”

The county leaders had a similar vision for the water supply, another important pillar of infrastructure in a boomtown. As the community recognized the strain oil development has on groundwater usage, they invested in a water system that would provide rural farm and ranching residents with quality water by selling a portion of the supply to oil companies. It’s a move that ensured their investment would serve other commercial needs as well as the new residential developments and help provide an attraction for new businesses when oil activity slows down. It was an innovative plan, one that has spent years in development but couldn’t be more timely.

Time. It is taking on a new meaning here where life, just a few years ago, had a different pace, where questions had a few moments to be answered, and most nights my father got home from town before the sun sunk below the buttes.

But McKenzie County is no stranger to the oil industry and to the pace it demands. This year the county will be celebrating its sixtieth year of oil activity and its county seat isn’t even 100 years old. Many long-time residents have had their hand in the industry at one point or another in their lifetime. Some have stories about finishing high school or returning home from college and working in the oil fields in the 1970s, moving up in the industry, making their place, seeing it through the rough times, and coming out on the other side as leaders and veterans of the industry.

The veterans of the oil industry were like the ranchers and farmers in this area today, working to exist and tend to their land while the search for oil below their wheat fields and pastures carries on around them. During rough times—times when cattle prices were low, or the rain didn’t fall—some of those landowners have taken a second job driving truck or pumping for oil to make ends meet, to pay off some debt, to get their kids through college.

And now, here we are again on the same landscape my great-grandfather settled almost 100 years ago and my generation is given the opportunity to come home to family ranches and a home that has, miraculously, stood up to the test of time. We’ve come back to live next door to our parents and have a hand in building up a now prosperous community that showed little signs of hope when we left it ten, twelve, twenty years ago.

Yet, we can’t help but hear the whispers and wonder about the pace, the gravel trucks, and rumors of booming businesses and new roads: What is going to happen when its slows down and the drilling moves on? Who will stay? What will become of this? Will we be able to afford to stay?

I talk about this with my father, back in his cowboy hat, when he stops over on Sunday mornings. I talk about our plans for the family’s ranch, how we would like to run our own cattle someday, how we would like to keep the landscape vital and raise a family in agriculture, community, and oil. We talk about what his parents would say if they were living today, if they could have had a little help from the minerals below the ground to pay off that tractor, to build a new fence, to fix up the barn.

What would they say about the sound of the trucks rolling over the hills? What would they say as another well goes up near their land? Would they go visit a neighbor to hear how their son is doing now that he has moved home? Would they go to church and marvel at how the pews are a little more full and then come home to lunch and a Sunday afternoon ride through the fields that are still theirs, the land they can still call home?

I don’t know. And I don’t know how our story will turn out in the end. But I do know this. I am home and it is very likely that without my husband’s work in the oil industry, I would not be writing these words. And, without the sacrifices my family made to keep the ranch in our family, we might find ourselves in similar situations as those people on the other end of my father’s phone line.

So I am grateful I have the opportunity now to ask the right questions and to have a hand in the leadership that is working on a long-range plan for the community where I want to raise my children—a plan that includes using an industry that has a presence in the community to help preserve a quality of life that includes well-maintained highways, safe water for our homes, thriving school systems, and quality medical services. If we keep these as our foundation, no matter what happens in an industry that is touching all of our lives out here in many ways, we will remain vital for years to come.

My father pulls down his wool cap and I grab my coat. My husband is home from work now and we are going out to check on things, to ride our horses to the top of the hills, to see if there is any fence that needs fixing. . . see if they’ve started on that pipeline.

As we step out the door, my father pauses for a minute, takes in a deep breath and looks around. “You know, there was a time not too long ago that I didn’t think anyone was going to be able to live back here. It was so quiet,” he says, as he steps off the porch. “I’m glad you’re home.”

Jessie Veeder Scofield is a singer, songwriter, photographer and writer who lives and works on her family’s 3,000-acre cattle ranch in western North Dakota with her husband Chad. She keeps a record of ranch life on her popular blog, “Meanwhile, back at the ranch...”, provides regular commentary on Prairie Public Radio’s program “Hear it Now,” and performs her original music throughout the Midwest. Visit veederranch.com for more information.