4 minute read

Who Will I Be When Place Changes?

By Ken Rogers

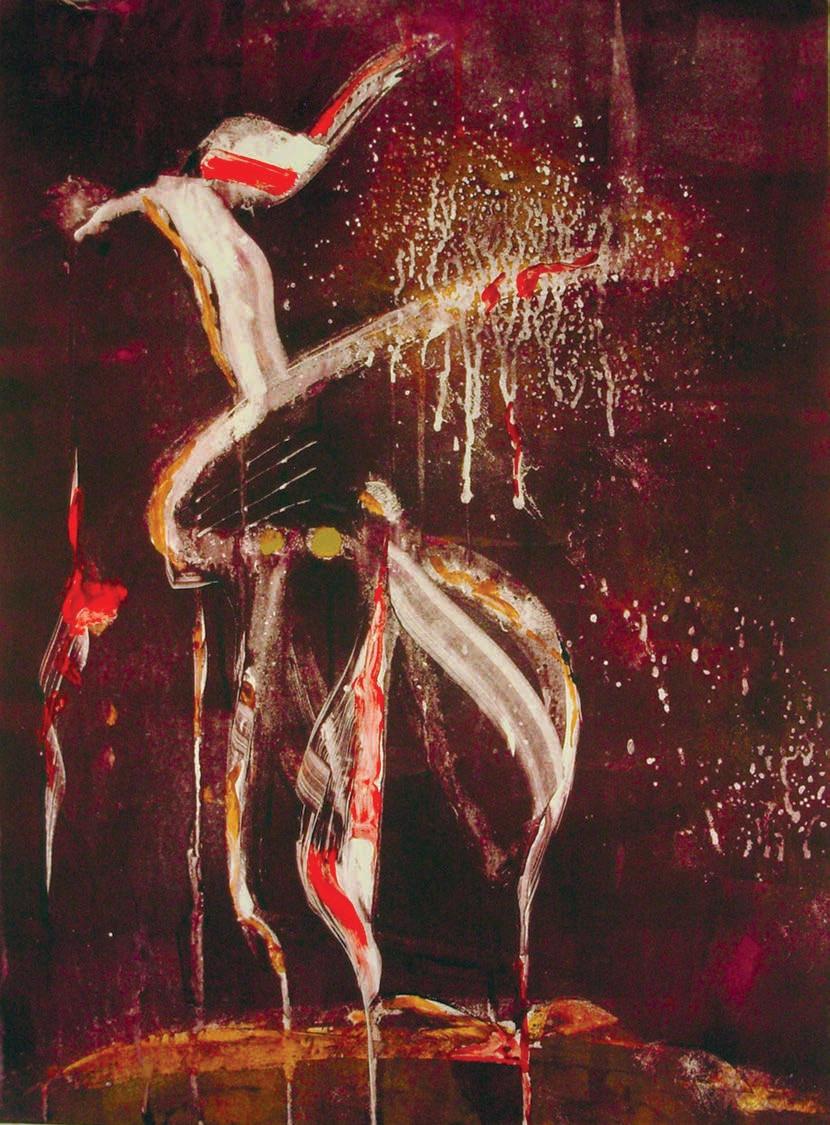

Spiritual Awakening IV by Michelle Lindblom, 24x18 monotype

Advertisement

The clatter of cottonwood leaves in a warm breeze. A pale red plume of dust drifting behind a pickup on a scoria-topped road. The scratch of buck brush on the legs of jeans. A jab from the thorn of a wild plum tree. Each strand of experience like DNA, hardwiring a person into this place—the short-grass prairie of western North Dakota. While some people have a calling—to God, to Medicine—others are shaped more by the coming together of earth, sun and water, living plants and animals and spirit in a particular landscape. These people are defined by a sense of place. So life has been for me, living here.

Why this place? Western North Dakota offers no easy life. Living must be scratched from its surface. The seasons can confound. Drought and blizzard test us time and time again. But living here, adapting to the cycle of life on the land, person and place merge. Memory and experience tell the story.

The sound of those waxy cottonwood leaves brings to life walking the creek bottoms or drowsing on the screened porch of the house I grew up in beneath a line of old cottonwoods. The scoria roads lead to summer memories of driving out in the country to meet a farmer’s daughter or a camping trip in the Badlands. We have become steeped in experiences and memories of our lives dovetailed with fieldstone, shale, and the white alkaline dust left behind by the sun and wind on the rolling prairie.

Sense of place becomes layered over years with an understanding of how life works here. Where the deer will lie down out of the storm. How following the coulees and draws will take you down to the creek. How in the morning calm, you know the wind will come. What farmers will be talking about when bringing grain to the local elevator. Or how to manage starting a car engine at 25 below zero.

William Least Heat-Moon, in PrairyErth, took the Jeffersonian grid laid over Chase County, Kansas, like an archeologist’s string grid at a dig site, and scraped back the layers of people and place. The hard logic of the grid allowed Least Heat-Moon to inspect the intersection between people and place and how they change each other.

The range, township, and section lines cannot push people and place into orderly boxes for study. Where the Norwegians settle overlaps with the Germans from Russian homesteads. Juneberries are best west of the Missouri River. The buttes are bigger, more imposing even farther west, where cattle are the bread and butter, not wheat. None of these follow the surveyor’s straight line.

Places, I think, are like churches. Over time, people praying and singing God’s praises there penetrate the plaster and wood with grace. And eventually people who enter the sanctuary can feel the sacred. When that church was newly blessed, it was little more than a building. Prayer made it a church, prayer over time made it sacred.

People living hard on the prairie have created for the land, and themselves, a particular, if not unique, sense of place.

Medicine Rock, along the Cannon Ball River southeast of Elgin, North Dakota, juts out into the prairie. For hundreds of years, young men from the Mandan and Hidatsa nation came to the sandstone outcropping to watch the grassy horizon for the return of the buffalo. While waiting, they carved turtles, bison hooves, and bear claws into the soft stone. They sang. They prayed. Standing on that stone today the spirit of that place looms large. It draws spirit seekers who leave behind prayer bundles tied to bushes and the fence surrounding the stone.

When beleaguered, we walk out on a high hill, along the river or to a rock or special place. Time and time again we return to tap something larger on the land than ourselves—its spirit and our relationship to that spirit.

Looking for direction in this place, a person cannot rely on the typical map, or even Least Heat-Moon’s grid; they are only stepping-off points, beginnings. For direction in landscape where people and place have become one, a person must turn to poems, songs, and stories. These contain clues to living on and moving across the land. These are narrative maps recorded by the people, like those of the aborigines of Australia that Bruce Chatwin writes about in The Songline— songs that show the way. Listening to these geographic histories gives truer direction to a persona than a topographical map.

Energy development has begun to rewrite the narrative map of western North Dakota, a place that has been slow to change. Oil rigs replace cottonwoods on the ridge line. A steady rumble from heavy trucks drowns out echo of the pounding hooves of the buffalo. New smells, sounds, sights are all around. Uncertainty swells in the sky above the sweeping prairie along the buttes. A thunderstorm, black as ink, black as oil, comes.

To have a sense of place, and to have that place change, puts at risk connections made between people and the land over a long life. What happens to the spirit when peoples’ roots are yanked from the narrative? What happens to the song on the prairie when noise from machines overcomes the music? Who will I be when place changes?

Presently the opinion page editor for the Bismarck Tribune, Ken Rogers grew up in Hebron. He has been a working journalist in western North Dakota since 1976, and, over the years, developed an interest in the history of the people living here and of this place. He and his wife, Debi, live in Mandan.