7 minute read

History of the Ghost Dance

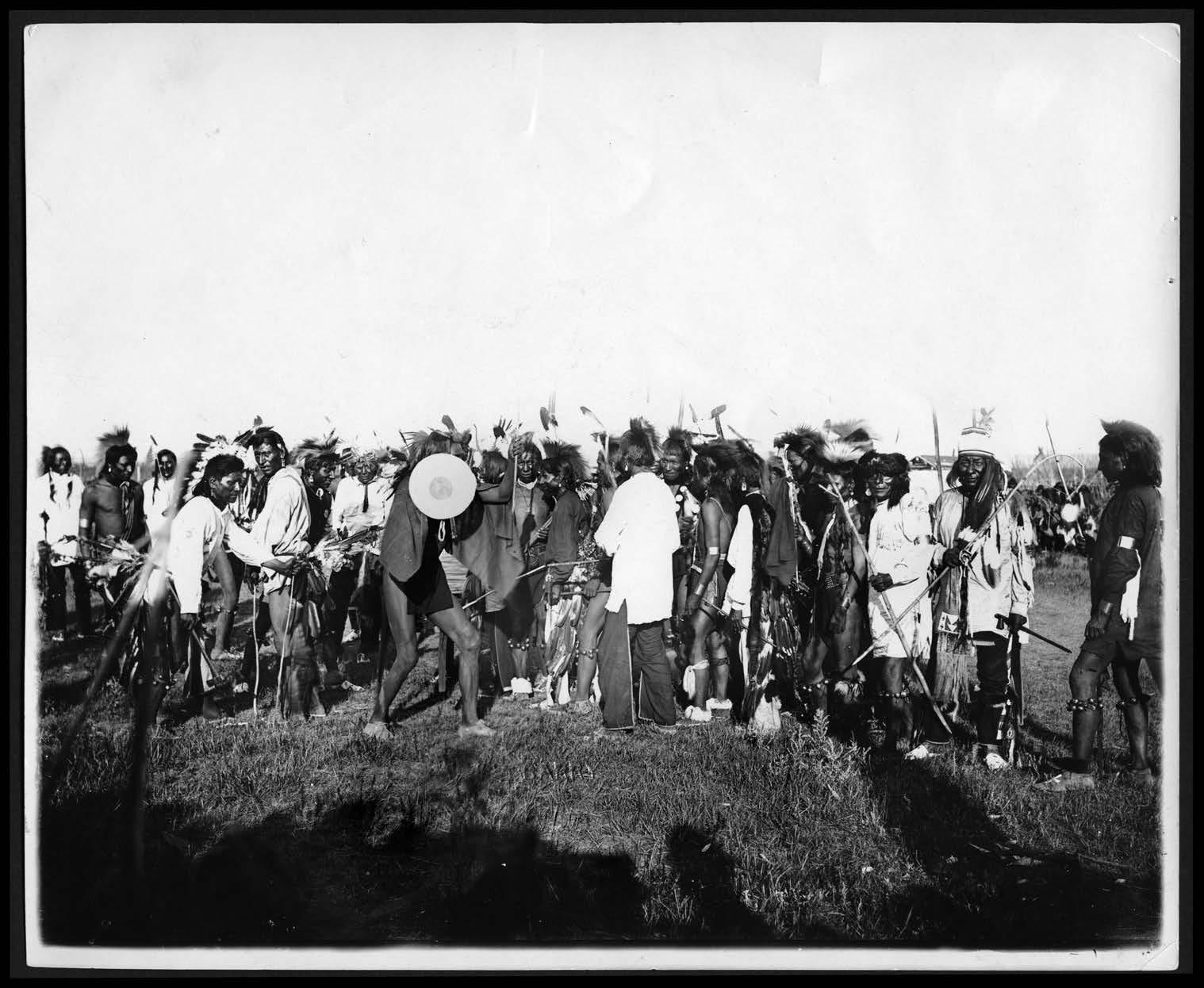

Cover Image: Ghost Dancers. State Historical Society of North Dakota C0256

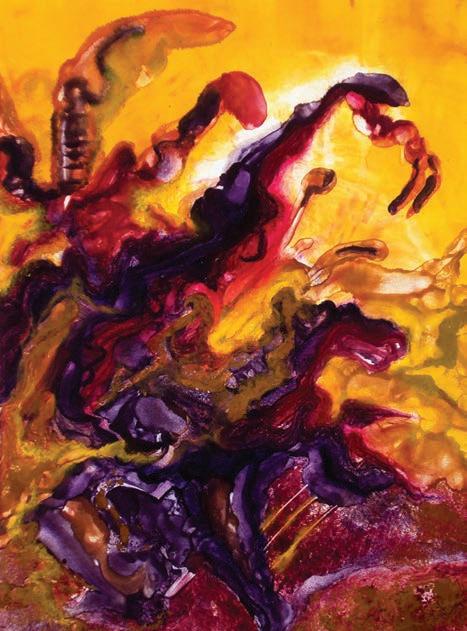

The origin of the Ghost Dance stemmed from the introduction of Christianity to the native people of the Northwest, specifically the Shaker Movement, in which Christians prayed and danced for the Second Appearance of Jesus Christ.

Advertisement

In October 1881, a Squaxin Indian man, known locally as John Slocum and living on the southwestern arm of Puget Sound, knelt down in the woods to pray about the evils in his life. Slocum reflected about the impacts that hard liquor, gambling, idleness, and general vice had on his life and the life of his people. Slocum took ill and by all accounts died. Later in the day Slocum revived and told everyone of his journey to heaven, where he was given a choice: either go to hell or return to the world and minister to his people. He chose to live again.

Slocum’s shaker ministry quickly spread to the native population in the Northwest, causing some unease among settlers because the Indian shakers had their own priests and built their own churches. The

Presbyterian ministers actively sought to include the Indian shakers in the body of the Presbyterian Church.

The Indian shakers became well known for visiting the shut-in and sick over whom they prayed themselves into a trance. A ritual followed the trance in which the sickness was pulled out of the patient and absorbed by the priest/medicine man who fell down dead and the patient recovered.

James Mooney, author of The Ghost Dance and Wounded Knee, collected the story of two shaker medicine men venturing south into central Oregon to apprentice a young Indian man of the tribes there, whom Mooney postulates could be none other than Wovoka, The Cutter.

Wovoka was the son of a highly respected medicine man or prophet of the Indian people in Mason Valley, called Tavibo. Tavibo died about 1870, leaving a fourteen-year-old son Wovoka. Wovoka came into the employment of David Wilson and was given the Anglo name, Jack Wilson. David Wilson employed Wovoka until about 1886, when Wovoka decided it was time to share his experience of heaven and the message he received.

During the solar eclipse of August 1868, Wovoka had fallen asleep and was taken up to heaven. There he saw all the people who had already departed and he met with God. Wovoka received the mission to go back to his people and tell them, “They must be good and love one another, have no quarrelling, and live in peace with the whites; that they must work, and not lie or steal; that they must put away the old practices that savored of war; that if they faithfully obeyed his instructions they would at last be reunited with their friends in this other world, where there would be no more death or sickness or old age.”

Wovoka was given a dance to take to the Indian peoples, a dance which must be performed for five consecutive days. Mooney, who interviewed Wovoka when he made a study of the Ghost Dance religion from December 1890 to April 1891, said that Wovoka disclaimed responsibility and association with the Ghost Dance shirt which had become an important part of the Sioux Ghost Dance. In fact, Wovoka asserted to Mooney, that it was “better to follow the white man’s road, and to adopt the habits of civilization,” and that his religion or practices were ones of universal peace.

Wovoka had gone to live among the Paiute Indians of Utah and spread his message and vision. From there his message spread east to the Northern Arapaho and Shoshoni of Wyoming, then on to the Lakota and Cheyenne. A few of the Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan became caught up in the news from Fort Washakie, Wyoming.

In the fall of 1889, three principal delegates—Porcupine (a Northern Cheyenne from Montana), Kicking Bear (Mniconjou Lakota, Cheyenne River Agency, South Dakota) and Short Bull (Sicangu Lakota, Rosebud Agency, South Dakota)—made a pilgrimage to Fort Washakie to hear about the Ghost Dance for themselves.

The Ogallala Lakota, Sword, had this to say, “In 1889, the Ogalala [sic] heard that the son of God had come upon earth in the west. They said the messiah was there, but he had come to help the Indians and not the whites, and it made the Indians happy to hear this.”

Porcupine, Kicking Bear, and Short Bull didn’t stop at Fort Washakie but continued on to Pyramid Lake to witness the Ghost Dance performed there. According to Porcupine, they were treated with kindness by the whites as they journeyed to the lake, and that even the whites participated in the Ghost Dance.

From Pyramid Lake, the delegation traveled to Walker Lake where Wovoka himself led a Ghost Dance. After the dance there, Wovoka entered into a trance. According to Porcupine, Wovoka awoke and proclaimed to all that he went to heaven, saw all those who had died before, and that he had been sent back to instruct the native people. Porcupine essayed further that Wovoka claimed to be the returned Christ, that the dead would be resurrected, the Indian people would live forever; that there would be universal peace, and death and destruction to those who refused his message.

The delegation returned to their agencies.

In October 1890, Kicking Bear introduced the Ghost Dance to Standing Rock at Sitting Bull’s invitation to perform the dance at his camp along the Grand River. The Indian Agent, Major James McLaughlin, dispatched the Indian police to arrest Kicking Bear, but they returned to the agent’s office unsuccessful. Sitting Bull promised McLaughlin that Kicking Bear would leave when he was finished, which he did after two days. Sitting Bull did not discourage the Ghost Dance on Standing Rock, and on the Cheyenne River reservation, the Indian police couldn’t stop Big Foot’s band from dancing.

It is important to remember that the Ghost Dance controversy was coming to a head on the heels of North and South Dakota achieving statehood. Indian reservations were made smaller. Hunting grounds were being settled and turned into farmland. Traditional and culturally significant landmarks were given over to citizens for farming or ranching. Drought had caused native farmers’ crops to fail two years in a row, and those who received government-issued rations received a third to a half of what was promised by treaty. People were nearly starving. It was a desperate time and the native peoples clung to a desperate faith.

General Miles, of Civil War fame and the capture of Indian leaders like Chief Joseph and Geronimo, advised that no additional military force was necessary; to let the Ghost Dance run its course; that “the excitement would die out of itself.” Indian agents at Lakota Sioux agencies became increasingly alarmed because they could not stop the dancing.

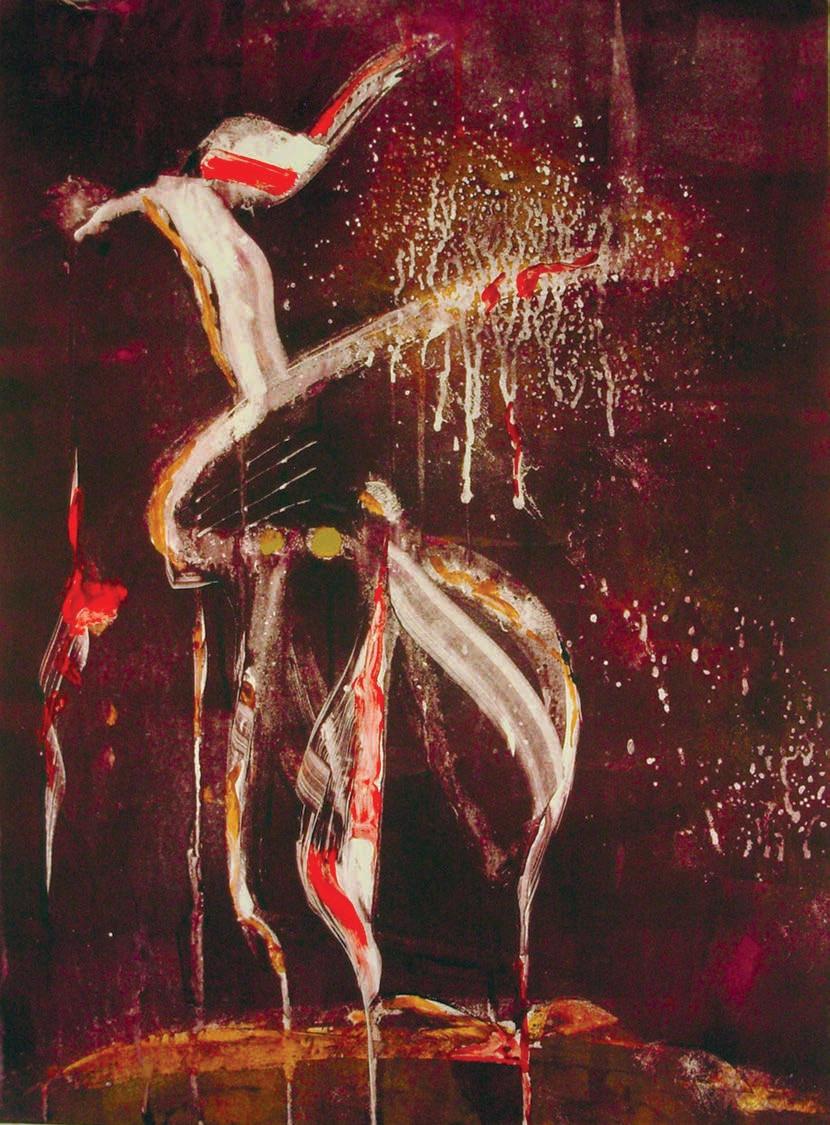

On October 31, 1890, Short Bull rounded up his Ghost Dance followers and encouraged them to gather in one place and prepare for the coming of the messiah, even if they were surrounded by troops, even if they were fired upon. The Lakota who participated in the Ghost Dance firmly believed that their Ghost Dance shirts made them impervious to bullets; that the bullets would pass through them without causing injury.

On November 17, 1890, soldiers were ordered to report throughout the Indian agencies at Cheyenne River, Lower Brule, Rosebud, and Pine Ridge, under the field command of General Miles, altogether about 3,000 soldiers. No action was needed as the mere presence of soldiers was enough to dissuade dancers from dancing. John Noble, Secretary of the Interior, immediately ordered full rations to be distributed according to treaty.

The Department of War assumed control of Standing Rock and made plans to arrest Sitting Bull. To convince Sitting Bull that his cooperation was necessary, former U.S. Military Scout William F. Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill, was sent to persuade Sitting Bull to turn himself in. Cody arrived at Fort Yates on November 28, 1890, but his orders to continue to Sitting Bull’s camp were halted by Agent McLaughlin.

According to Mooney, Agent McLaughlin believed that a conflict would follow if the military were to arrest Sitting Bull. The military arrest was delayed on the advice of McLaughlin who told Cody that he’d send Indian police, which he did on December 14, 1890. The next morning Lieutenant Bull Head led the attempt to arrest Sitting Bull. The effort ended in disaster with the death of Sitting Bull and seven of his followers, and the death of Bull Head and seven of his police officers.