Newsletter of the History of Art Department at the Fashion Institute of Technology

Volume 7, Spring 2025

Volume 7, Spring 2025

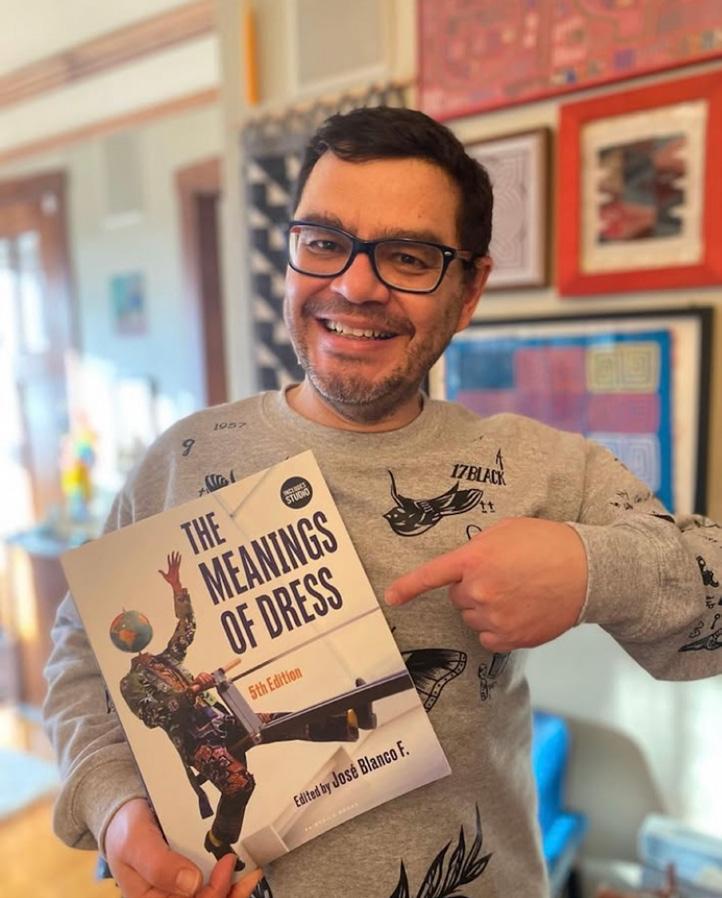

In Fall 2024 the History of Art Department was thrilled to welcome a new full-time faculty member, José Blanco F., a fashion historian who specializes in men’s fashion and in fashion and visual culture in Latin America and the Latinx diaspora. We also celebrated the retirement of Lourdes Font, who created much of the fashion history curricula in the department and founded the Fashion History, Theory and Culture minor. We’re happy to say she will continue to teach a few courses for us online.

We are grateful to Lourdes for her heroic efforts this year to expand our costume design history offerings from one course to three new ones, each cross-listed with film. Look for HA/FI 257: Costume in Science Fiction and Fantasy Films, HA /FI 263: Fashion in Film, and HA/FI 275: Costume in Period Films starting next spring!

Andrea Vázquez de Arthur also wrote a new Presidential Scholars course, HA 323: Luxury in the Indigenous Americas (Honors), which will be offered for the first time in Fall 2025. Jennifer Babcock, who already teaches our study abroad course in Morocco (offered again in Winter 2026) and who specializes in Egyptian art, has written a new course, Study Abroad in Egypt: The Pyramids and Beyond (HA 250), which will first be offered in Summer 2026, so plan ahead!

In this age of AI, we are also grateful to new part-time faculty member Eana Kim and to Kyunghee Pyun for developing the new course HA 324: Art and Technology Since 1960. We also approved three courses for online delivery: Global Modern Art 1750–1950 (HA 131), Dada & Surrealism (HA 232), and Global Baroque (HA 302).

This year the department taught more than 4,800 students, including 45 majors in our Art History and Museum Professions program. Our new courses and the new General Education requirements for students entering in Fall 2024 resulted in a slight bump in our enrollment; we’re teaching more than 100 more students than last academic year.

AHMPA, the art history and museum professions student club continues to thrive and do exciting field trips, including to Washington DC with Prof. Kristen Laciste. The Fashion History Club also was approved to restart meetings and events in Fall 2025.

The Fashion History Timeline website attracted more than 2 million visitors in the last year, and its Instagram page hit more than 60k followers. We’re grateful to the Liberal Arts and Sciences Dean’s office and Academic Affairs for funds to redesign the ten-year-old site, which will make the site faster and more mobile friendly. Look for its refreshed look later this summer!

We’re grateful as always to the efforts of our Department Coordinator, Jasmin Miranda, who keeps everything running smoothly and is celebrating her one-year anniversary in the department. Thanks as ever to Molly Schoen, Visual Resources Curator, and Nanja Andriananjason, Technologist, for their essential support of our faculty and students.

We look forward to the return from sabbatical of professors Rich Turnbull and Alex Nagel in the fall, which promises to be another exciting year for the department!

Justine De Young, Associate Professor and Chair, History of Art

The History of Art Department extends its gratitude to Professor Lourdes Font, who retired at the end of the Spring 2025 semester. She received a PhD from NYU with her dissertation “Fashion and the Art of Literary Illustration.” In 1992, her career at FIT began when she was hired as an adjunct to teach HA 344: History of Western Costume (now called European Fashion: Ancient Origins to Modern Styles.) In 2003, she was promoted to a full-time faculty position in both the History of Art Department and the Fashion and Textiles Studies program in the School of Graduate Studies. She is the first professor in FIT’s history to have a split appointment. From 2020 to 2022, she served as Acting Chair of Fashion and Textile Studies. Among Professor Font’s many contributions to FIT, she created the interdisciplinary Fashion History, Theory, and

minor.

The FIT History of Art Department acknowledges that it is located on Lenapehoking, the ancestral homelands of the Lenape people. We recognize the continued significance of these lands for Lenape nations past and present; we pay our respects to the ancestors, as well as to past, present, and emerging Lenape leaders. We also want to recognize that New York City has one of the largest urban Indigenous populations in the United States. We believe that addressing structural Indigenous exclusion and erasure is critically important and we are committed to actively working to overcome the ongoing effects and realities of settler-colonialism within the institutions where we currently work.

PROFESSOR KYUNGHEE PYUN

ACTING CHAIR, ART HISTORY AND MUSEUM PROFESSIONS

For the Fall 2024 semester, the Art History and Museum Professions (AHMP) major program accepted twenty-two new students. Four students were new to FIT, while eighteen had completed an associate degree program at FIT before starting the AHMP program.

A highlight of the program’s activities this year was the

Led by curator Lisa Yen (AHMP ‘25) and advised by Professor Kyunghee Pyun, students reflected on museums’ responsibility to the public in recognition of Black History Month. Contributors included Thursday Abad, Samantha Barnes, Ashley Villegas Hernandez, JaDea Houston, and Cassandra (Cassie) Hughes —all graduating in May 2025. On view at the Gladys Marcus Library’s fourth-floor display case, this project showcased books related to five recent exhibitions in five different New York City museums. Students demonstrated how these shows—including the Whitney’s Edges of Ailey, the Met’s Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt 1876–Now, and the FIT Museum’s Africa’s Fashion Diaspora—provided glimpses into the world of Black artists who have shaped so much of American art and music, yet their names too often remained unspoken. History is full of forgotten voices, but large cultural centers can forever change the way they are remembered. Museums hold power, and with that power comes an obligation to the communities that support them. The types of artwork and artists that museums choose for exhibitions reveal what is valued in society (figs. 1–6)

Patrick Garry (AHMP ‘25) was awarded the student award from the FIT Couture Council in September 2024. Ashley Villegas Hernandez (AHMP ‘25) landed a job at Queens Museum as visitor service associate. Wyley Menolascino (AHMP ‘25) worked as a seasonal visitor services associate at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in his hometown of Jackson, Wyoming and will begin an internship in the museum’s education department this summer. Samantha Barnes was elected President of the FIT Student Government Association. She also was admitted to the FIT Master of Arts program Fashion and Textile Studies: History, Theory, Museum Practice. Renée Dery (AHMP ‘25) was a finalist for the George T. Dosch Endowed Scholarship and found a position at the Metropolitan Opera as a chaperone for the children’s chorus. She spent one semester in Florence.

Meanwhile, collaborations between AHMP and the Museum at FIT (MFIT) continued to flourish.

As museum facilitators, students Sacha Lewis, Reeana Miller, Rebecca Lefvre , Lola Eguiguren, Isabella Rasch , and Tessa Young had the exciting opportunity to work for the MFIT exhibition Africa’s Fashion Diaspora (figs. 7–8). Other museum facilitators in the Spring 2025 semester included Kelsea Scarlett , James Pantano , Meribelle Halsema , Sophie Hodge , and Ja’Dea Houston . They guided visitors for the exhibition Fashioning Wonder: A Cabinet of Curiosities

Opportunities for AHMP students are not limited to the New York City area, however. Maria Martin, Marielle Hickley , and Maria Monge studied abroad in the fall semester; in the spring semester, Maimouna Sow, Katherine McConnell, Isabella Rasch , Alexa Bonaci , and Michelle Shevtsov studied abroad in Italy. AHMP students also organized a field trip to Washington, DC this spring. This wonderful opportunity resulted from the collective efforts of the Art History and Museum Professions Association (AHMPA). Professor Kyunghee Pyun and Professor Kristen Laciste are co-advisors of the club. With their guidance, students visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the National Gallery of Art.

Our AHMP students also participated in FIT’s Womxn’s Empowerment Conference on March 14, celebrating Women’s History Month. In a panel called “From Campus to Career: How FIT Leadership Transforms Your Path,” FIT SGA President Samantha Barnes and FIT Gender Equity Senator Thursday Abad discussed how their leadership roles outside the classroom have influenced their careers. Other panelists included Tara Levy (AMC ‘18), Account Director at VaynerMedia; Jordyn DeCosta (FBM ‘24), Merchandise Assistant at TJX Companies, Inc.; and Rach Brosman (AMC ‘20), Founder of Support Women DJs and CEO of Delirium Entertainment.

The AHMP program sincerely thanks Dean Patrick Knisley and Chairperson Justine De Young for providing financial support for these important experiential learning experiences with museum professionals.

AHMP students organized a talk with speaker Lucian Simmons, Head of Provenance Research, a new position within the Director’s Office at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Thanks to Professor Amy Werbel’s initiative, AHMP students also participated in The State of the Museum panel discussion as part of the ARTSpeak series organized by FIT’s Fine Arts Department. Our students engaged thoughtfully in the discussion by asking critical questions of panelists Ashley James, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art, Guggenheim Museum; Andrea Achi, Associate Curator of Byzantine Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Eric Shiner, President of Powerhouse Arts; and Sara Raza, Artistic Director and Chief Curator of the Center for Contemporary Art in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

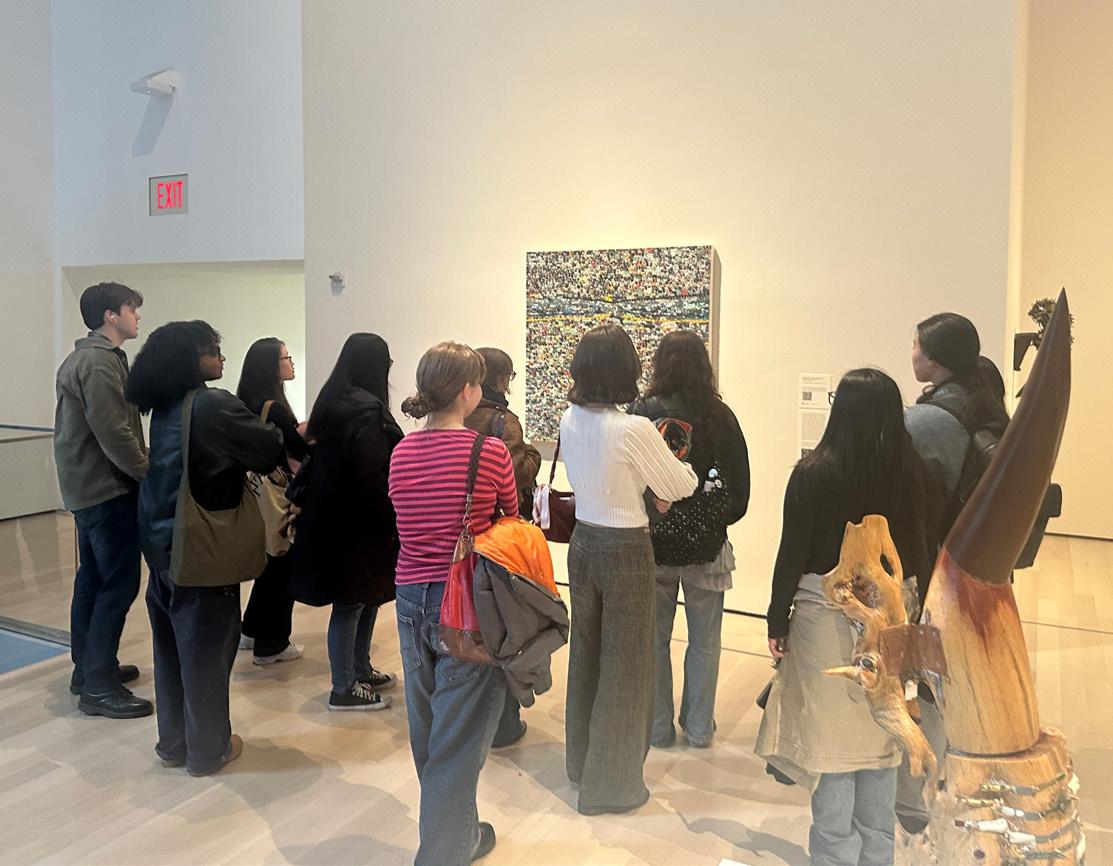

Guest speakers in our courses included Molly Schoen, our department’s Visual Resources Curator and Visiting Assistant Professor of information science at Pratt Institute; Tanya Melendez-Escalante, Frida McKeon Loyola, and Sonia Dingilian of the Museum at FIT; Professor Brenda Cowan in FIT’s Exhibition and Experience Design department; Laure Dubois, Director of Marketing for the Armory Show; Paul Galloway, Collection Specialist of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art (figs. 9–12); Audrey Teuber and Arielle Dumornay, both from the FIT Foundation (figs. 13–15); John Lindaman, Head of Technical Services at the Thomas Watson Library of the Metropolitan Museum (figs. 16–17); Caroline Samuels, Deputy to the Vice President for Finance and Administration at FIT and a collector of contemporary prints serving the board of the Print Club of New York; Shawnee Turner, Director of Interpretation and Visitor Experience at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati; Melissa Falkenham, Senior Manager for Tours and Groups at the Museum of Modern Art; Bethany Gingrich, Collections Specialist at the Costume Institute, the Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Stella Hobart, an AHMP graduate working at the time for Visitor Services at the the Whitney Museum.

Karla Medina (AHMP ‘21) is now the curatorial coordinator at the American Federation of Arts. Natalie Przybylski (AHMP ‘21) is working for the New York Botanical Garden as a business operations associate. Michael Naples (AHMP ‘18) has been promoted to manager of development at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. Stella Hobart (AHMP ‘24) left her position at the Whitney Museum of American Art and became an exhibitor services associate for SPACE | Design + Production, which produces art fairs and trade shows such as the Armory Show and the Affordable Art Fair. Tessa Young (AHMP ‘24) is working at the Morgan Library & Museum (fig. 18) Frida McKeon Loyola (AHMP ‘22) became an assistant curator of education and public outreach at the Museum at FIT after completing a master’s at FIT in Fashion and Textile Studies: History, Theory, Museum Practice.

Finally, I want to congratulate all the 2025 AHMP graduates for their dedication, teamwork, and brilliant ideas throughout their time in the program. This year, we celebrated our senior banquet on the glamorous stage of the Morris W. and Fannie B. Haft Auditorium on May 12, which featured live music by guest performer John Lindaman of the band True Love Always. (Thank you, John!)

The History of Art Department wishes you all the best in your future careers!

PROFESSOR ANNA BLUME

During my 2023–2024 year-long sabbatical I was able to complete several projects that would not have been possible for me while teaching. The mindset of teaching—especially at FIT where we in the liberal arts teach over a hundred students a semester with four different preparations— necessitates a centrifugal mind, spinning outward to fully engage with students in the classroom. On sabbatical, however, the movement is centripetal, allowing my mind to move inward, to linger on thoughts, get tangled and lost, fishing for ideas and words to shatter or reveal understandings and perspectives.

In the midst of research and writing, the Max Planck Institute at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, Italy accepted my proposal to present a paper on the aesthetics of spider web construction at the Mapping Animals in Global Spaces interdisciplinary workshop, held 25–26 January 2024. As a historian of prehistoric art, I had recently expanded my studies into the influence that animal architecture and aesthetics has had on the earliest known human-made architecture and art. In 2022 I began teaching a new class at FIT entitled Animals, Architecture, and Aesthetics (HA 230) as an elective in the History of Art Department and in the Ethics and Sustainability minor. This has led to my specialization in spider web construction.

When fellow History of Art professor Alex Nagel told me of a call for papers by the Max Planck Institute—an institute foremost in the study of empirical aesthetics—to present research on the complex interrelationships between human and other animal constructions, I was delighted to see that there are other scholars with similar interests to my own. This two-day immersion into discussion and shared debate with a selective group of international scholars on animal aesthetics

greatly benefitted my own research and further revealed the extraordinary intellectual environment of FIT, where a professor such as myself can devise and teach a course in a nascent and vitally important field of study. I look forward to future semesters teaching this course and to publishing a revised version of my paper in the months and years ahead.

A few months after presenting my paper on spider web construction in Florence, Hannah Baeder, the director of the 4A_Lab of the Max Planck Institute in Berlin, invited me to present a keynote paper in November 2024 at a week-long conference entitled Ecological Entanglements Across Collections – Plant Lives and Beyond. To meet this challenge, I wrote a paper entitled Maya Cloud Forests and Muybridge Photographs, 1875. I had studied these photographs thirty years ago when I was still a graduate student writing a chapter of my dissertation. It was exceedingly meaningful for me to return to them with a vastly different perspective, more attentive to the plants and trees and to the complex photographic practice than I had been in the past. In preparation for writing this essay, I was able to see and study at Stony Brook University’s special collections the most extensive of the original Muybridge bound books of images from his 1875 travels in Central America.

For the remainder of my sabbatical year into the fall and spring of 2024–2025, I have been rewriting and editing an essay on bannerstones. These artworks of the ancient Indigenous past of North America are often locked in cabinets in the storage areas of museums or held in private collections, rarely seen by scholars, and almost never seen by the public. Against the custom of this kind of exclusive ownership or viewing of the ancient Indigenous past, all the work that

I have done on bannerstones is available on open-source platforms. While researching and writing, I was invited to give a paper on bannerstones by the Theoretical Archaeological Group in Santa Fe in Santa Fe from May 21–23, 2024. Sponsored by the Picuris Pueblo Native American Tribe, this particular conference included a vast number of Indigenous scholars and artists who shared unique and vitally important reflections on bannerstones and their place within collections and in the land. The discussions and feedback I received at a conference has fundamentally shifted my approach to the research and writing I will do during the month of June. Throughout the two-day conference I meet with scholars from across the field of archaeology to discuss new approaches to the gathering, interpreting, and care of the remains of past cultures. These discussions have also given me new ways to think and respect the ancient history of Indigenous people of the Americas. Soon after the conference ended, I received a much welcome invitation to publish an online open-source version of this paper with the Yale University journal MAVCOR

Now, as I write this in March 2025, I am astounded by the current federal government’s assault on colleges and universities. We are the brunt of anger and intolerance toward any production of knowledge or critical thinking that might reveal the greed and cruelty of an administration bent on narrow definitions of bodies and beings in time and space. Our greatest hope is to stand together.

F.

Some of the fondest memories of my childhood in Costa Rica come from my obsession with sticker albums—well, they were not stickers at that time, just collectible trading cards on soft paper that you would then glue to the album pages. I had so many of those albums during my childhood and teenage years and treasured them for decades. My parents, Flora and Porfirio, were truly working class and were never able to give me much money to buy stamps. I managed to save some money to buy my collectible cards from working at the store owned by my uncle Nello and my aunt Cocora, who were wealthier than my parents and treated me as one of their children. One of my favorite albums was Paises y Costumbres (Countries and Customs). I loved looking at the images and reading about the lives of people in lands so far away that I knew I could never visit. Their clothing, jewelry, hats, and other elements of dress were always striking to me. I was fascinated with the idea that people could look and dress so differently from me. The excitement of learning about global people and their material culture never went away. I am happy to report that I have visited many of those places pictured in my albums and have collected a few textile pieces from around the world.

The past five years of my life have been incredibly busy.

I would say “the busiest I have ever had,” but my friends keep telling me that I always say that. I worked on several writing projects while teaching full time and, well… yes, I also moved to New York last year to start a new job at the History of Art Department at FIT. While selling a house and packing boxes to move to a smaller apartment in New York, I finished editing the fifth edition of The Meanings of Dress (Fairchild, 2024) and co-edited, with my husband, Raúl J. Vázquez-López, a special issue on Latin American and Latinx Fashion for Fashion, Style and Popular Culture (Intellect, 2024). Once in New York, Raúl and I finished our upcoming book Dress, Fashion and National Identity in Puerto Rico (Bloomsbury, 2025) and I continued working with my friends Ben Barry and Andy Reilly on the upcoming The Intellect Handbook of Men’s Fashion (Intellect, 2026). Are you tired yet? I am! Still, there is one more project—the one that took me five years—my upcoming book Global Perspectives: Dress and Fashion in the 20th and 21st Centuries (Fairchild, 2026).

As a child, I had limited experience with fashion. Most memories come from helping my aunt Teresa in her sewing workshop. She was an expert seamstress, and I loved organizing fabrics and notions in her store. I did that for hours only to come back the following day to find out she had made a mess again rushing to finish pieces for customers. If I were to go back and tell that kid that one day he would write a book about fashion, he would be confused. If I told him it would include material about global fashion and dress as fascinating as those images in his childhood album, he would get up fast and find a way to get to the future as soon as possible— I would tell him to wait and enjoy life.

I conceived Global Perspectives: Dress and Fashion in the 20th and 21st Centuries as a learning solution for the study of dress and fashion in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. My desire as an educator and author was to write a book that would keep readers intrigued, curious, and excited to learn about fashion in the last 124 years. The book also encourages readers to consider their location and identity. In other words, as they read, they should always be asking themselves: Why does this matter? How is this important to me?

The textbook questions the still dominant view that Europe and the United States (“The West”) have an almost exclusive hold in the creation of modern societies and, therefore, have been and are the locus of innovation for fashion. Instead, I explore dress as global material culture and fashion as a global phenomenon that reflects and influences both local and global cultures.

This project is presented as a departure platform and a learning resource to fuel and guide conversations about global fashion—including what the term means.

The emphasis is on establishing larger contexts that allow for a study of global dress and fashion in response to the zeitgeist of a certain period, regardless of whether that zeitgeist is global, regional, or national. The first two chapters provide a review of terminology, concepts, and methodologies used in the fields of fashion history, dress history, fashion studies, material culture, and other connected fields. Chapters 3 to 10 present a chronological narrative of fashion history through selected global case studies. In each chapter, the first unit reviews the zeitgeist in terms of dress and fashion and connections to dominant art and design movements. The second unit examines social aspects including the influence of global changes in demographics, politics, economics, trade, migration, and conflicts in the historic development of dress and fashion. The third unit reviews ways in which dress and fashion communicate meaning in cultural identity, material culture, and human behavior. The last unit centers on the business of fashion and includes a review of major global trends in design, manufacturing, marketing, retailing, consumer behavior, causes and forms of injustice in the global fashion industry, and industry efforts to promote agency, equity, and justice. The goal is to expand beyond the stories traditionally told in fashion history books to achieve a more complete picture of the history of global fashion.

So, in a few months, I should figure out how to get into a time machine and deliver a copy of this book (signed, of course) to my childhood self. Stay tuned!

I am excited to have embarked on this next chapter of my career at FIT, where I began as a graduate student in the Fashion and Textile Studies program. Upon completion of my master's degree, I began teaching as an adjunct in the History of Art Department. For five years, I taught Costume and Fashion in Film (HA 347) and History of Twentieth-Century Fashion in Europe and the U.S. (HA 346)—two courses I was deeply passionate about. As of the beginning of this past academic year, I have transitioned into a full-time role at the Museum at FIT.

Working at a museum has been a long-time career goal for me, and I consider myself profoundly lucky to be at an institution with such a vast and rich collection. Some of my duties include overseeing the Study Collection, giving exhibition tours, and fielding research requests. My experience as an instructor prepared me well for the job—I became very familiar with the Study Collection’s holdings after bringing my classes to visit over the years. Additionally, I came into the job with an understanding of the needs of the faculty and am able to work with them to put together a selection of garments that best suits their curriculum.

It is so nice that this new position allows me to cross paths with my HA colleagues—and former students as well! I like to think that I am still serving the department and helping to support its educational mission… just from a different angle.

–Raissa Bretaña, Education and Collections Assistant, Museum at FIT

To help illustrate this year’s issue of Art History Insider, students currently or previously enrolled in History of Art courses submitted their own original artworks.

Thank you to all who submitted. We love seeing your work!

This exhibition, held in Fall 2024, deals with the subjugation of people that had grown up as girls, examining the delicate balance between social conformity and self-discovery. Highlighting the tension between cultural norms and personal identity through the medium of photography, this project was developed as a creative partnership between Sacha Lewis, an Art History and Museum Professions exchange student and Adriana Gavilanes, a Photography major. Gavilanes sourced the photographers; Lewis wrote and conceptualized the exhibit. Both curated and installed the show on the 4th floor wall displays in the Photography Department’s first student-led exhibition. It was pivotal, in the current climate, that the exhibition

engineered social discourse on subjugated bodies. Seven FIT photography students interpreted this topic to produce a varied show.

Mia Baric, framed by her viewpoint as a queer first-generation American, depicts her own conflictions with the memory of girlhood. A disposition that is culturally specific, the position of “girl” is questioned via traditional projections of a nostalgic bedroom wall.

Massiel Cedeño questions the notion that Black girls are “strong” or “angry.” These labels obscure the actuality of their lived experiences. Cedeño’s work aims to dismantle these reductive tropes, choosing to

emphasize grace and vulnerability. In capturing moments of tenderness and self-reflection, Cedeño provides a space where Black women are seen as autonomous and multidimensional.

Polina Farage evokes an all-too-familiar voyeuristic lens on the female body. Peering through door frames, the viewer is placed to invade another’s space.

Lily Fong denotes the innocence of girlhood to be complicated by an outsider’s perspective. In its purity, girlhood evokes a tangible reality of a reclaimed past and simultaneously to be an invented fiction.

Adriana Gavilanes dissects the roles that comprise a “girl” in a tripartite series. These external standards, rooted in tradition and perpetuated by the media, often create a narrow framework for femininity that can stifle individuality and authenticity. The series explores themes of self-discovery and the defiance of these societal expectations, highlighting the tension between conforming to idealized versions of girlhood and embracing a true self.

Bitzy Lyn subverts femininity and the perception of people raised as girls. Subjected to societal belief systems, Lyn’s work amplifies the brutal confinement these roles have on one’s body and mentality. The restraint of being raised a girl and the struggle to attain acceptability is influenced by the artist’s experience. Lyn’s work champions transcending binaries to dissolve prescribed gender roles in adolescence to ask the question: where will we go when gender is no longer burdensome?

Elsa Propper foregrounds the performance that creates womanhood. Performance is a mask to hide and pretend, but it is also multi-faceted as it can celebrate the individual within. The harsh reality of girlhood is viscerally amplified in Propper’s interpretation, with streams of blood dripping down the artist’s face, highlighting the unease between the true self and the performing self.

About the curator: Sacha Lewis (they/she) is an Art History and Museum Professions student on exchange from York University, UK. They are passionate about modern and contemporary art’s ability to create space for social influence.

George Dorsch, a professor at FIT for thirty-eight years and chairperson of the History of Art Department between 1990 and 1994, is remembered by many of his colleagues for his kindness and extraordinary generosity. The latter was only fully understood after his death: he had bequeathed funds for annual awards to both students and adjunct faculty at FIT. Since 2004, the George T. Dorsch Endowed Scholarship has supported students who have performed exceptionally in History of Art courses, and the George T. Dorsch Endowed Fellowship has supported research and travel for adjunct art history professors with PhDs. Every year, the winning student and faculty member each receive an award of approximately $20,000 each.

George's face expressed his kind nature, as evident in this photo from the 1989 volume of Portfolio, FIT’s yearbook. He was a large man, who often swam before going to work, according to colleagues.

An obituary notice sent by FIT to The New York Times (Oct. 4, 2000) tells us the following:

The History of Art Department of FIT is grieved to announce the death of our friend and colleague who was born July 2, 1936 and died on September 15. A beloved and inspiring teacher at FIT since 1968, Professor Dorsch served as chairperson of the department from 1990 to 1994 and oversaw its growth from its inception in 1989, particularly fostering the areas of East and West Asian art, modern architecture and medieval art. He opened these and other worlds to many students who will mourn him as deeply as do the members of the department and the FIT community.

Prof. Dorsch was born in Manhattan. His 1966 thesis for his M.A. in art history from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts is entitled “The Raising of Lazarus in Late Medieval Northern European Art: A Study in Iconography.” It is available in its original form in Special Collections at the FIT Library.

Some colleagues whose employment overlapped Prof. Dorsch’s have shared memories of him. Dr. William Barcham, who taught at the school from 1977 until 2010, responded with:

First, George’s gift was not only unexpected, it was unique among all liberal arts programs at FIT. Whereas the professional majors have outside industrial or business support, history of art does not, and George’s generous gift allowed worthy students and professors to further their studies and perhaps travels which they otherwise could not have done. Second, and I remember George for this, he was a gentle soul, perhaps with too little grit for my taste, but that’s neither here nor there. His affability and sweetness (because he was really sweet) surely stood behind his generosity. He always had a smile for others in the corridors, even when frazzled.

Dr. David Dearinger, an adjunct at FIT from 1989 to 2011, offered these memories:

Adjectives: kind, low-keyed, informal, collegial, unpretentious (certainly no intimation that he had enough money to fund fellowships… Who knew!?)

I never heard anything negative about him from my students, some of whom didn’t hesitate to dish other art history teachers. A few did comment about his informality of dress, of which they seemed to approve. As far as I could tell, George’s informality at work was simply an extension of his domestic life: I ran into him several times in the Village, walking his dog (I think), dressed in the exact manner he dressed at work—baggy shorts, shortsleeved untucked shirt. I never saw him in a suit, jacket, or tie.

Far more importantly: George had a rare, perhaps unique, concern about the well-being of the adjuncts in the department; and, as I witnessed on several occasions, [he] defended us as best he could.

Most impressively, and as he proved with his legacy—the only one of its kind that I’ve ever heard of—George apparently had a deep, unsuspected loyalty to FIT and sought, in his quiet way, to make it a better place… His concern for FIT was not expressed in some sort of performance for the administration or a phony, self-serving fundraising gambit, but in his decision to support what he took to be the more vulnerable members of the faculty, i.e., the adjuncts. This might be taken as a brand of paternalistic condescension on his part; but if it was, I never saw a hint of that in his interactions with me or any of my colleagues.

Various colleagues remember Prof. Dorsch’s low-keyed approach to administrative matters while also recalling that he often moved quietly but with haste to resolve problems. Prof. Louis Zaera, a colleague

from the Social Sciences Department when it shared a chairmanship with History of Art, provided the following memory: “George was a very private, quiet, nice person. I never head him raise his voice nor complain about anybody or anything.” Potential adjuncts who were interviewed by George for positions still gratefully remember the ease of the process.

Editor’s note: the quotations in this article have been condensed for length.

Jennifer Miyuki Babcock, PhD, recipient of the 2024 George T. Dorsch Endowed Fellowship

William Viquez Mora, Photography and Related Media ’26, recipient of the 2024 George T. Dorsch Endowed Scholarship

Many congratulations to Jennifer and William!

For more information, visit the George T. Dorsch Awards page on our website.

On April 5th, AHMPA students visited museums in Washington, D.C., accompanied by Professor Kristen Laciste. Though he is currently on sabbatical, Professor Alex Nagel led students on a tour of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History (pictured here). For more photos, please visit AHMPA's Instagram account.

History of Art is the most popular minor at FIT, according to a 2018–2023 analysis conducted by the Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness.

Even though my major is Fashion Design, I’ve always been drawn to art and the stories behind it, which is why I chose to minor in History of Art. It’s something I truly enjoy, and it has had a big impact on how I think and create as a designer.

Art history and fashion are more connected than they might seem. Learning about different time periods, styles, and cultures gives me a wide range of visual inspiration. I often find myself inspired by paintings, sculptures, and historical objects. The colors, textures, and shapes I see in art often spark ideas for new designs.

One example is my final thesis project, which was inspired by Japanese Edo-period Rinpa school paintings. I was fascinated by these artists’ use of gold backgrounds and the way they combined nature and abstraction. That idea stayed with me, and I ended up creating a fur garment with golden pigment brushed onto the surface. It was my way of translating the mood and richness of Rinpa art into fashion. Without my art history classes, I might never have discovered that connection.

I also love learning the context behind art—why it was made, what it meant at the time, and how it influenced the culture around it. That deeper understanding helps me think more carefully about my own design choices. I don’t just want to make something beautiful—I want to tell a story or express a feeling.

Minoring in History of Art has expanded my creative world. It helps me look at things differently and find meaning in details I might have missed before. It’s made me a more thoughtful, curious, and inspired designer, and I’m really glad I chose it.

I committed to FIT to pursue a business degree, but I have always had a fascination with the artistic world. While taking business-oriented classes, I became drawn to History of Art courses that were offered outside of the Fashion Business Management program because they offered a wide variety of courses and niche subject matters. I found that my art history studies aided my development in my overall education, allowing me to better tailor my career aspirations to align with my interests and future goals.

Classes such as the History of Business in the Visual Arts (HA 309) and Art In New York (HA 214) provided perspective on both the overall impact of art within business and the contribution of artistic expression to the modern world. Art history classes allowed me to

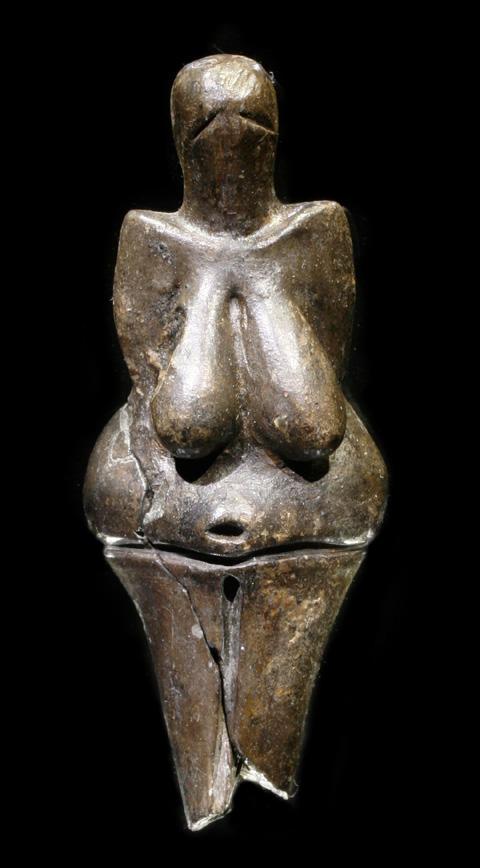

Where to begin? My name is Andrew and I am a junior in Graphic Design, minoring in History of Art. I never had the opportunity to formally study art history in high school, which honestly felt like a crime considering how integral of a role it has played in my life. My journey began with HA 111: History of Art and Civilization in the Mediterranean and Beyond: Prehistory Through the Middle Ages. One of the very first pieces I was introduced to was the Venus of Vestonice, created around 30,000 years ago. I see it as the foundation of my curiosity: something just clicked. That tiny sculpture is not just a sculpture to be admired; it offers a glimpse of early humanity, how people saw themselves, the world, and the values they cherished. And that perspective of viewing art just stuck with me.

Right as I was entering my first semester in the Graphic Design bachelor’s program, I took HA 211: Asian American Art and Design. The class could not have come at a better time. To be honest I felt lost at sea with no compass nor a north star to guide me during that semester. But then I was introduced to artists like Tyrus Wong, Hideo Noda, Nam June Paik, and Chiura Obata, creatives who paved their way in a society that often ignored them and did not consider them part of “American” history. Seeing how they navigated their identities through art, despite the barriers they faced, gave me a sense of belonging I didn’t even realize I needed and became the guide I sought.

explore a personal interest, while adding insight and direction to my business degree. Aside from developing my career interests, studying art history encouraged me to gain insight into politics, government, and sustainability, all with new, more globally centered perspectives. Studying art history in tandem with a business degree led me to pursue further studies in sustainability and conservation within the fashion and art industries, introducing me to new opportunities and areas of study.

I am currently pursuing a law degree with the eventual goal of working within corporate social responsibility, art conservation, and environmental sustainability. I credit my Art History minor with providing direction for my career aspirations, leading me toward fields that I am passionate about. Further, studying art history has greatly impacted my college experience. It’s allowed me to engage with a more diverse group of students, travel, and gain interests outside of the classroom, including involvement with local museums and galleries. Selecting this minor has resulted in a prolonged interest in the art industry as well as critical insight into real-world issues, human connectivity, and the importance of history.

–Lily Peterson, Fashion Business Management ‘24

It also made me rethink the nature of art itself not just as a visual form, but also as a means of reclaiming history and reshaping those narratives. I felt it was my responsibility to learn this history: to learn about those who paved the way for future generations but also to explore this idea of identity and what defines me.

I think that is why minoring in History of Art seamlessly works hand-in-hand with my major in Graphic Design. The field of art and design is not just strictly about making visuals look good; it is also about communication, purpose, and what perspective is presented. It is the depth needed to think beyond the surface, to look at cultural contexts more closely and carefully. Art has always been about the moments that are bigger than ourselves.

I was an artist before I became a designer; it is best to not let that part of myself die but rather to join hands and be the bridge of those two practices.

–Andrew Guo, Graphic Design ‘26

Visit the History of Art minor page to learn more.

On March 24th, I had the special opportunity to bring my Western Theories of Art (HA 411) class to Jack Whitten: The Messenger, the landmark retrospective that had just opened to the public at the Museum of Modern Art on March 23. It was not only a remarkable chance for students to experience Whitten’s deeply experimental and expansive practice up close, but also personally meaningful for me—as I had the privilege of working on the exhibition while working at MoMA.

Spanning six decades of Whitten’s work, this long overdue and critically acclaimed retrospective occupies the museum’s largest gallery and has already been recognized as one of the most significant surveys in recent years. As part of the curatorial team, I brought both my research expertise and curatorial experience to the project—contributing to the development of the exhibition and catalogue while managing major deadlines, overseeing content development, and coordinating cross-departmental workflows.

One of the contributions I am proudest of involved leading the research and preparation of rare archival materials. Among these was the discovery of exclusive, never-before-published photographs of Whitten taken by his close friend, photographer Paul G. Viani. I had the absolute thrill of uncovering these images, which had likely remained unseen outside the artist’s estate until now. These photographs now appear throughout the exhibition and catalogue. I also selected and

prepared other archival materials such as studio logs and family photographs, directing the high-resolution scanning process and curating selections for display in the vitrines.

To prepare for our visit, my students read Whitten’s 2017 interview in The Brooklyn Rail with Jarrett Earnest. Grounded in that text, we had an engaging discussion in the museum, guided by close looking and the incredible material complexity of Whitten’s work. As makers themselves, many students were especially drawn to his inventive

use of materials—particularly in his iconic Black Monolith series, where he embedded mosaic-like tiles and various found elements into richly layered acrylic surfaces. They asked thoughtful questions about process, surface, and form and were eager to unpack how such complex surfaces were built.

One of the most impactful moments came while viewing 9.11.01 (2006), a monumental painting incorporating ash, dust, blood, and bones. The physicality of the materials—and the emotional charge— left a strong impression. And while discussing a work from the Greek Alphabet series, one student remarked, “It’s so overwhelming—it has multiple layers that evoke optical illusions.”

During our visit, I shared behind-the-scenes stories from my time on the project, ranging from my collaborations with the artist’s family and studio team to installation decisions involving lighting, sound licensing, and conservation concerns. These glimpses into the exhibition’s making process helped bridge the gap between museum work and classroom learning.

While HA 411 is a theory-focused course, my primary goal is to make the material relevant to students’ lives: engaging with contemporary issues, exhibitions on view, and applying theoretical frameworks in direct, experiential ways. This visit did exactly that: it brought our discussions to life and sparked a level of engagement that extended well beyond the classroom.

As a newly appointed faculty member at FIT, this visit was one of the highlights of my semester. It was deeply rewarding to connect students with the work of such a visionary artist, and to share in their discoveries through the lens of both curatorial practice and critical theory.

At the Frick Collection, I am a museum educator. I facilitate close-looking dialogues for school and college visits, gallery talks during special events, and private tours. I have also been developing a series of art-making programs, the first of which we conducted virtually and later in-person at partner institutions. I began with a presentation of collage examples in the history of art before inviting participants to explore different techniques for building compositions out of “found images,” pulling from old art books and magazines. Now that the museum is reopened, we have the brand new Ian Wardropper Education Room, which expands our reach as a department, particularly with more art-making programs. You can also read this recent blog post about our recent education programs.

–Samuel Snodgrass, Adjunct Instructor

CHLOE PAPLIN, INTERIOR DESIGN ‘26, MINORING IN HISTORY OF ART

Written for HA 309: History of Business in the Visual Arts 1800–2000 (Honors), taught

by Professor Kyunghee Pyun

Often referred to as America’s first interior designer, Elsie de Wolfe was the first in her field to receive commissions for her work, shaping the design world as a result. De Wolfe created a reputation for herself through her hospitality, fashion, world travels, and sought-after interior aesthetics allowing her to charge commissions on her work and establish her revolutionary design career. Taking advantage of the general public’s desire to live the high life, as well as her social status, de Wolfe was able to monetize her looks, writing, design style, and overall personality to a variety of audiences. People would aspire to hire her for her services and if they could not afford that, they would aspire to follow her design advice on their own.

Elsie de Wolfe describes herself in her autobiography, After All, as “an ugly child born in an ugly time (1865).”¹ She recalls her childhood being comfortable but inconsistent as she and her family had to move often. Her father, a doctor, was able to support the family but had debts of his own that would end up forcing the family to move from brownstone to brownstone, a style of home Elsie always despised. She later would go on to describe such architecture as dismal, gloomy barracks with long flights of ugly stairs. She expresses her distaste at the sameness of these homes and questions how an owner could possibly know their brownstone from another.² Elsie would go on to renounce the dark and drab interiors of said brownstones, along with the design of the homes she lived in as a child. As one example, Elsie recalls a day when she arrived home from school to find that her parents had re-wallpapered the drawing room. The William Morris wallpaper, popular at the time, sent Elsie into a tantrum with its grey palm leaves and red and green splotches set on a tan background. Upon seeing this decor, she threw herself onto the ground and cried, “It’s so ugly! It’s so ugly!”³ Based on these vivid memories that de Wolfe recalls throughout her books, it is safe to say that she always had a strong connection with interior design and how it could elicit feeling. Her sense of style would only be a fraction of what made her so admirable as a friend, partner, and businesswoman.

Taking a rebellious stance against the classic Victorian interiors that she had grown up surrounded by, de Wolfe decided it would be her duty to design in a completely opposite way. Where Victorian interiors were heavy, dark, and drab, de Wolfe’s interiors were light, airy, and natural. Utilizing mirrors, pale colors, chintz, white flowers, trellises, white paint, and light furniture, Elsie brought back more of a Rococo style in her designs.4 This transformation from regal to refreshed can be seen in almost all of de Wolfe’s projects.

It is important to note the success of de Wolfe’s design style before discussing her client base due to the fact that her sense of style was

a personal endeavor from the start. It is said that de Wolfe created interest among her neighbors and would often help them to redecorate their homes. After some time providing her services as a favor, de Wolfe decided it would be appropriate to begin charging for her work. She then sent out business cards that declared herself a professional interior designer. This is where the demand for de Wolfe’s design skills would come into play.

Guests of all statuses and affluence levels would find themselves in awe of de Wolfe’s homes and ask for her assistance in their own homes. These beginnings—mixed with word of mouth—would get de Wolfe started in her new career as a luxury interior designer. By 1905, de Wolfe would receive her first large commission for the design of the Colony Club, America’s first exclusive private women’s club.5

While Elsie de Wolfe’s design style was incredibly influential towards her successes and legacy, it is important to understand the other factors that made her so successful as a designer and even more importantly, a businesswoman. During the 19th century, it was critical for women in business to hold a certain reputation. While qualifications and skill were important in the world of self-employment, social status also held a large amount of value. It can be concluded that clients would often hire de Wolfe for one of two reasons. They either felt that she was a talented designer who would be able to transform their interiors into something of an ideal form or they believed that having a woman of higher socioeconomic status work for them would aid their own desires in becoming part of that “club” as well. Lees Maffei states, “De Wolfe’s signature mixture of Louis this and that—a general ‘Francophile aesthetic’—appealed to the self-made elite, for whom de Wolfe worked, as a mode of communicating success, wealth, educated taste and the niceties of life as well as ‘dynastic gloss.’”6 Of course this conclusion is generalized, and it is understandable that clients may have been drawn to her for a number of other reasons, however it is crucial to see the connection between de Wolfe’s social status, economic situation, and her successes as an interior designer and entrepreneur.

With that being said, the question then becomes how did Elsie de Wolfe create such a name for herself? It is easy to say that she was a woman of varied interests and talents. As many have noted, Elsie De Wolfe lived life in high style, surrounding herself with wealthy and well-known public figures. Before her career as an interior designer, de Wolfe worked as a Broadway actress; when that failed, she became one of the first female theater agents and Broadway producers. It was during her time in the theatre world that de Wolfe would meet her longest and closest companion, Elizabeth (Bessie) Marbury. Benjamin Weaver of The London List describes Bessie Marbury as a self-made businesswoman as well. She did this by “convincing Victorien Sardou, the president of the French Society of Dramatic Authors, that she should collect royalties on behalf of the French writers whose plays in translation were Broadway hits.”7 Drawn to Marbury’s social status and wealth, de Wolfe saw her as a role model and friend. The two would soon move into the Irving House together where Elsie would establish herself as New York’s most luxurious and unapologetic interior designer.

From there, Elsie would take on small jobs until she landed her first big client, the Colony Club. Giving a woman such a job was unorthodox for the founding members of the club, but eventually they decided de Wolfe was a good fit. As the club’s architect stated, “Give the job to Elsie, and let the girl alone. She knows more than any of us.” The Colony Club’s successful design would put Elsie on the map for wealthier clients. The rooms were designed luxuriously and tastefully, while also avoiding following the common design of a gentlemen’s club. De Wolfe’s timeless designs and concepts can still be found in classic bedrooms and hospitality spaces today.8 Following her work for the Colony Club, de Wolfe would be hired to design Henry Clay Frick’s fifth avenue mansion. Frick, one of the greatest industrialists

and collectors of all time, was willing to pay de Wolfe commission for anything that she sourced for him. One morning, de Wolfe took Frick to view the French Decorative Arts Assembly, where Frick would go on to spend one to three million dollars on paintings, sculptures, furnishings, and other decorative art. While de Wolfe had only asked for a 10% commission for the job, as it was one of her first, this purchase by Frick gave de Wolfe one of the highest incomes in America that year.9 This job in particular would make de Wolfe the wealthy aristocratic woman she is remembered to be.

Later, de Wolfe married Sir Charles Mendl, press and media manager for the British Embassy, further projecting her into the limelight. In the beginning of their relationship, the Mendls lived in a mansion in Versailles, France, built by Louis the XV from 1661–1715. Here, de Wolfe turned one of the mansion’s many bathrooms into a lounge and would even host dinners right next to the bathtub, making her the talk of the town in the 1930s. The room was decorated with animal-print cushions and a fireplace for ambiance with space to seat guests of incredible status. While the room itself was beautiful, guests were often in awe of Elsie’s creativity and confidence in designing such a space.¹0 The Mendls named their house the “Villa Trianon,” and Elsie worked on restoring it until 1941, when they were forced to flee Europe after the Nazi invasion of Paris. Moving from Europe to Beverly Hills, Elsie had gained a new sense of luxurious classic European style, which further honed her love for antique goods and ornamented finishes. This developed style would be used in her new home, which she affectionately named “After All,” likely as an homage to her book under the same name, and which would serve as a portfolio of her skill for guests to admire.¹¹ Elsie found herself surrounded by many actors, film producers, and directors. It was in her “After All” house where she would host the rich and famous of Los Angeles at her over-the-top parties and events.

While the planning and hosting of lavish dinner parties and dances was a hobby of de Wolfe’s, she also took the opportunity to impress potential clients with her design skills. Parties became yet another way that Elsie de Wolfe was able to advertise herself to the public and develop her reputation. Her love of hosting was known to be methodical and “all inclusive.” When hosting, she made sure that the house and guest rooms were fully stocked with anything and everything a guest may need. She kept notes of who was invited, who attended, what was done, and what was served. She used this information to

improve future events and make sure that all of her guests were taken care of. This would then allow her to keep track of potential clients and get to know them more personally before working with them. Elsie also used these parties to test recipes, games, decor, and table settings. If they were a hit, she would write about them in her Vogue magazine column, which allowed women at home to read about and replicate Elsie’s good housekeeping.¹² Her biography A Decorative Life states that it was a mix of Elsie’s design talents and her own appearance that won the hearts of her guests. As film director and guest George Cukor said, “It was a perfectly ordinary house, but her personality made it lambert.”¹³ Elsie would lean into this concept of selling herself through appearances in other ways.

While de Wolfe was famous for her classic designs, she was also famous for her fashion and beautiful looks. The fact that de Wolfe could grab consumers’ attention with more than just her title as interior designer meant that she was able to generate more buzz surrounding her name. This act of advertisement made her well-known to the wealthy and an idol to those of a lower socioeconomic status. Penny Spark’s essay “The ‘Ideal’ and the ‘Real’ Interior in Elsie de Wolfe’s The House in Good Taste of 1913” summarizes this: “The shift from de Wolfe as actress and fashionable clotheshorse to decorator was one that the delineator felt it needed to spell out to its readers.”¹4 In an attempt to make her work more accessible to those who could not afford her services, Elsie began writing women’s magazine columns. Her articles spanned across topics such as how to spruce up one’s home for cheap, how to utilize a room for more than one activity to save space, how to use white paint to transform a space, and how to paint motifs on simple furniture for a new look. Elsie also wrote columns on women’s fashion, beauty, hosting, and table settings. By writing to a more general audience, she aimed to make her designs more accessible to those who could not afford them. While this was a nice gesture, it also aided in the self-advertising and monetization of her work. If women at home could not afford to hire Elsie, they could at least read her articles and carry out the work themselves, making Elsie all the more popular.

These magazine articles would later snowball and culminate into Elsie’s 1913 book, The House in Good Taste. The promotion of consumer fantasy through The House in Good Taste aimed to let women

of lesser wealth know that they too could in fact design their homes to display an aristocratic style. Alongside those words of affirmation and tips on how to create a more budget-friendly space, de Wolfe also shared images of her incredibly lavish interiors that she had created for wealthy clients.¹5 This disconnect was evident but did not keep common women from following de Wolfe’s writing, further developing her client network. The consumer not only wanted to replicate Elsie’s interiors, they wanted to replicate her life.

Taking de Wolfe’s reformative design style, her bold personality, and her talent in networking into account, it is easy to see how she was able to create such a reputation for herself. While her interior design skills are impressive on their own, her business skills are what truly made her such a successful designer. Without her talent for knowing how to draw in clients through hosting, her desirable persona, and selling her work through various forms of media, such as magazines and books, Elsie de Wolfe would not have been as much of an inspiration as she is today. It is an important note for any self-made artist and designer: talent in the arts is only half the battle. The other half is having the drive and talent to sell yourself in a world full of other talented artists, something that Elsie de Wolfe perfected throughout her career.

1. Ayaz Basrai, “The First Interior Designer: Here’s the Story of Elsie de Wolfe,” Houzz, 2021, https://www.houzz.in/magazine/the-first-interior-designer-heres-the-story-of-elsie-de-wolfe-stseti vw-vs~153487844.

2. Elsie De Wolfe and Cairns Collection of American Women Writers, The House in Good Taste. (Century Co., 1913), p. 35.

3. Ayaz Basrai, “The First Interior Designer.”

4. John Nielsen, “The Elsie de Wolfe Design Revolution,” The New York Times, December 24, 1987.

5. Ronald C Budny, “Interior Design from the Beginning: Elsie de Wolfe,” Indianapolis Business Journal 29, no. 17 (2008).

6. Grace Lees-Maffei, Elsie de Wolfe, and Mitchell Owens, Elsie De Wolfe : The Birth of Modern Interior Decoration, (Acanthus Press, 2005), p. 174.

7. Benjamin Weaver, “The House in Good Taste,” The London List, 2020, https://www.thelondonlist.com/culture/elsie-de-wolfe.

8. Bundy, “Interior Design.”

9. Weaver, “The House in Good Taste.”

10. Cecil Beaton, “Elsie de Wolfe: Making of a Legend,” A Decorative Affair (2016), https://adecorativeaffair.wordpress.com/2016/05/01/elsie-de-wolfemaking-of-a-legend/.

11. Bundy, “Interior Design.”

12. Bundy, “Interior Design.”

13. Nina Campbell and Caroline Seebohm, Elsie de Wolfe: A Decorative Life, (C. Potter Publishers, 1992), p. 130

14. Penny Sparke, “The ‘Ideal’ and the ‘Real’ Interior in Elsie de Wolfe’s The House in Good Taste of 1913,” Journal of Design History 16, no. 1 (2003): 63–76.

15. Sparke, “The ‘Ideal’ and the ‘Real,’” p.66–67.

I started at FIT in 2019 originally as an illustration student. At the beginning, I had no idea what kind of career I wanted to pursue, except that I had to be around art in some capacity. During my third year in the illustration program, I realized that the only classes I was excited to take were the art history classes on my schedule. With the encouragement from a friend who was already in the program, I decided to change my major to Art History & Museum Professions.

While in AHMP, I felt very motivated to get involved in the program and all it had to offer. I did three internships, I was a museum facilitator at the Museum at FIT, I was a finalist for the George T. Dorsch Endowed Scholarship, and I ended up winning the Museum at FIT Student Award at the Couture Council Luncheon in 2023. The biggest takeaway I got from the AHMP program was realizing just how many museum- and arts-related careers and opportunities are out there and how to find them.

Upon graduation, I landed a job in Visitor & Gallery Assistance at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In March, I started a new full-time position as an Exhibitor Services Associate for a company called SPACE Productions that produces art fairs such as the Armory Show, the Affordable Art Fair, PULSE Contemporary Art Fair, and Art Basel Miami. None of this would have been possible without the education, encouragement and guidance from my professors and peers in the AHMP program.

If I could give any advice to students currently in AHMP, it would be to take every opportunity at FIT you can. Whether it be doing the MFIT facilitator program, joining the AHMP Association, being a student curator for MFIT, or getting involved in the Student Government Association, being a part of the FIT AHMP community is an amazing way to jumpstart your career. Also, keep in touch with your professors and the staff at FIT! They’re so helpful and great people to have in your network.

–Stella Hobart, AHMP ‘24

In September 2024, I had the opportunity to visit the Paul Allen collection on view at Christie’s with my classmates in MP 361: History and Meaning of Museums. The collection is a perfect representation of the journey from idea to reality to legacy. Whether big or small, each piece in the collection has an irrevocable place in human history.

Relishing in the various pieces of our modern history and observing their newfound significance has broadened my perspective tremendously. The Paul Allen collection is futuristic in the most antiquated way. Compared to the other auction rooms, it stood on its own and echoed the hopes of what tomorrow would look like while honoring the advancements of yesterday.

Starting with an RMS Titanic First Class Luncheon Menu from 1912 to the Apple Computer 1 of 1976, my peers and I were introduced to the venerable innovations that helped create our current world. We walked through the gallery and pondered over whether these were pieces of art or not. It was a profound experience because we had just finished our History and

Meaning of Museums class earlier that day: a course where we question, learn, and understand how the display of art and other historical pieces give them a new meaning. We can easily acknowledge the value each piece holds, but we cannot entirely discern how to rate its intrinsic value.

This exciting field trip was a great way to begin the semester; it was fun and beautiful to discuss with classmates as we were all still relatively new to one another. We all spoke and mingled while enjoying complimentary treats and drinks. Then we had the opportunity to break off and explore each room alongside one another.

The best part, for me, was meeting Neil DeGrasse Tyson filming outside of Christie’s. He graciously took photos with us, leaving a lasting impression on the entire experience.

–Maimouna

Sow, AHMP ‘26

In 2020, I began developing a photography project about my family and their health adversities. When I first heard about the George T. Dorsch Endowed Scholarship award going into my senior year at FIT, I knew that my project would be the perfect fit for this prestigious opportunity. With support from professors and peers, I gained the confidence to apply and was awarded this scholarship that changed my life.

As a photographer, my way of handling extreme events happening in my life, or to my loved ones, is by documenting what is happening and turning it into something beautiful. That’s why I started photographing close family members who were going through health issues like cancer. This is a pain that too many of us have also known, watching a close relative like a mom or sister struggle with overcoming such a diagnosis. I knew I needed to make something bigger with this photo project, in a way that would help share my experience and let others know they are not alone. So I completed the project by developing a photo book entitled Flowers Grow from Broken Bones. Thanks to the grant I was able to travel between my hometown of Utica and New York City to visit with my loved ones and photograph the process of them overcoming their illnesses to become happily cancer-free today. Soon my book will be available for purchase, for people of all kinds to look through, and hopefully they will be able to share emotions presented in its pages. Even though you are going through a difficult time, you can still find the beauty in things; flowers really can grow from broken bones.

Not only did this grant aid me in completing my fine arts photography project, but since being awarded The George T. Dorsch Endowed Scholarship, I have been able to launch my photography career into the professional world. With this generous award I was able to purchase top-of-the-industry lighting and photo equipment to help take my photoshoots to the next level. Without this grant, I would have had to rent and pay for each use of lights like this. Now I have them at my disposal whenever I need to use them. With this new equipment added to my arsenal, I have done photo shoots for the cover of an editorial, for modeling agencies, for a designer during New York Fashion Week, and I have expanded my freelance work. Additionally, I have been able to let my creativity loose and experiment with advanced techniques. I feel more confident now to say yes to freelancing jobs and to be able to create beautiful images without the stress of how much renting the gear will cost. One of the best parts about this is how long this equipment will last me. I fully believe these lights will support my photography journey over the next 30 years in the industry.

I always try to remember where I have come from; giving back to the FIT community by mentoring or inspiring other students to develop projects and apply for this grant is something I hope I get the opportunity to do. I am endlessly grateful for the professors and peers who encouraged me to go for this opportunity.

See images from my most recent shoots and from February NYFW 2025.

Before joining FIT’s History of Art Department in Fall 2023, I had the pleasure and privilege of serving as the 2023 Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Scholar at Smarthistory: The Center for Public Art History. While there, I contributed ten essays for the Arts of Africa section, which I have assigned in two of the courses I teach at FIT: HA 123 African Art and Civilization, and HA 239 History of African Textiles and Fashion. The practice of writing these essays—which are intended to be accessible and conversational—and assigning them in courses reflects how Smarthistory got its start.

Smarthistory is a nonprofit that creates free, open-access resources that make art history approachable for learners and supportive for instructors, giving them good-quality images to teach with.

All the content is contributed by experts in their respective fields of study. This past March, I had the joy of speaking with Smarthistory’s co-founders, Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. The first Smarthistory resources stemmed from the essays and videos that Beth and Steven created for their online courses taught as full-time History of Art Department faculty at FIT. The initial impetus came from the desire to provide engaging content for students free of cost. Since its inception, Smarthistory has grown over the past two decades in terms of content, moving geographically beyond Europe and the United States to across the world; delivery of content, including videos, guides, and books; number of contributors and partners (from two experts to eight hundred, and from museums based in New York City to partnerships with sixty around the world); and reach (from a couple hundred views from students in the classroom to 5 to 10 million worldwide per year).

One of the surprising aspects I learned about Smarthistory during my conversation with Beth and Steven was that there was never a grand plan for how the nonprofit would operate and unfold. Rather, they envisioned that Smarthistory would be a “platform for the discipline of art history,” meeting the needs of the classroom and adapting to innovations in technology. According to Beth, one of the first audio tracks recorded for students was on Auguste Renoir’s Two Young Girls at the Piano (1892) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was recorded using a microphone plugged into an iPod. While the technology has changed over the years, the aim of creating content that is clear, comprehensible, and compelling to audiences has not.

When I asked Beth and Steven about their hopes for Smarthistory for the next 20 years, they said that they hope that Smarthistory would “impact the discipline of art history” by being a “model for collaborati[on].” For Steven, Smarthistory would encourage scholars to move beyond “working alone in a library and see[ing] their research as theirs [alone].” As I reflect on my brief time at Smarthistory and my time at FIT so far, I find that the collaborative process, or the process of dialoguing and working with others, is becoming more of the norm for me. The essays I contributed to Smarthistory would have not been possible nor published without the insight and feedback of colleagues within and outside my field of study, African art history. At FIT, I find that it is near impossible to be alone working—I have been in countless conversations with my colleagues within the History of Art Department, with those on the verge of beginning their doctoral research or completing their graduate studies, and with those work-

ing in other colleges/universities and museums. In one of the courses I am teaching this semester, MP 307 Professional Practicum for Museums and Galleries, I had students choose a work to write in the style of a Smarthistory essay as a way to teach them how to write in an accessible manner. Before grading these essays, I gave students the opportunity to review each other’s essays and practice giving feedback.

Lastly, Beth and Steven hope that Smarthistory “will get people around the world to fall in love with art history.” Art history has the potential and power to broaden horizons, challenge preconceived notions, and help people become more open, curious, and understanding of peoples and cultures across time and space. I am certain and confident that because of Smarthistory, art history has captured the hearts of many around the world.

Recipient of the 2024 George T. Dorsch Endowed Fellowship, JENNIFER MIYUKI BABCOCK also received an FIT faculty development grant in April 2025. This award supported her presentation “Animal Amulets and Their Designs: A Special Look at the Hare” at the annual conference of the American Research Center in Egypt. Additionally, she gave two invited lectures in the past academic year, one at FIT and one at Pratt Institute. Rethinking Ancient Egypt, a book she co-edited and wrote a chapter for, was published in 2025; she also signed a contract with Palgrave-Macmillan for a book set to be released in 2028.

The Meanings of Dress, a volume edited by new fulltime History of Art faculty member, JOSÉ BLANCO F., was released in 2024. Additionally, José wrote the prologue for (Re) Dressing American Fashion, released in 2025; co-authored an article in the Fall 2024 issue of ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America; and guest edited a special issue of the journal Fashion, Style and Popular Culture. He presented the opening plenary at the Power and Possibility in Fashion Media conference at Southern Methodist University, was a panelist at two FIT events, and he gave a lecture to the Latino/Latin American Studies Program of Saint John’s University in Minnesota.

ANNA BLUME published articles on bannerstones for Yale University’s MAVCOR Journal and for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Their speaking engagements included lectures for the Theoretical Archaeology Group of New Mexico, the Max Planck Institute of Berlin, and the Pre-Columbian Society of New York. This summer, they will begin a research fellowship at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, Italy.

Department chair JUSTINE DE YOUNG organized a screening of the documentary Red Fever, including a Q&A with fashion designer Korina Emmerich and moderated by

Natalie Nudell, in conjunction with the FIT Library and the Fashion Studies Alliance. She was an invited speaker at the Nineteenth-Century Studies Association conference, the Nineteenth-Century French Studies Annual Colloquium, and for Study Day at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She was also an invited participant for an event at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art.

DAVID DROGIN was a panel chair and an invited roundtable participant at the Sixteenth Century Society Annual Conference in November 2024, and he also served as a panel chair at the Renaissance Society of America Annual Conference in March 2025.

In August 2024, MARIANNE EGGLER published a book review of Screen Interiors: From Country Houses to Cosmic Heterotopias in the journal Design and Culture.

ISABELLE HELD co-authored a chapter in The Routledge Handbook of Archaeology and Plastics, wrote an article for the June 2024 issue of Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty, and reviewed the exhibition

John Waters: Pope of Trash in the Summer 2024 issue of Fashion Theory. Additionally, in August 2024 she gave a lecture for an event hosted by the Costume Studies department at New York University.

EANA KIM served as curatorial assistant for the Museum of Modern Art exhibition

Jack Whitten: the Messenger and wrote an essay for its accompanying catalogue. She presented at the Aesthetics of Bio-Machines

and the Question of Life conference, held at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. She also authored six exhibition reviews for The Brooklyn Rail, The Art Newspaper, and the Korean magazine Public Art

Awarded an FIT faculty development grant in 2024, KRISTEN LACISTE was a presenter and session co-chair for multiple sessions of the African Studies Association conference; she also presented at the College Art Association conference. In addition, she was invited to lecture at two FIT events as well as for a graduate course at New York University. Her recent publications include contributions to the Fall 2024 issue of African Arts and the pamphlet text for the exhibition Ukupupuka: An Exploration of Transcendence, held at the University of California Santa Cruz.

SUMMER LEE published “Modern Monstrosities: The Depth and Breadth of the Oxford Bags Phenomenon” in the March 2025 issue of Dress, the journal of the Costume Society of America. She also gave talks at the George Washington University Museum, the Genesee Country Village & Museum, and for the Feminist Lecture Program.

KENNA LIBES , editor of the upcoming book Fashion’s Missing Masses: The Representation of Marginalized Populations in Collections and Exhibitions of Dress, published articles in the June 2024 issues of Dress and the Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology. She also presented at the Costume Society of America’s Dress panel as well as at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Symposium on Historical Dress.

While on sabbatical, ALEX NAGEL received news that his book Color and Meaning in the Art of Achaemenid Persia was selected for Iran’s 2025 World Book Award. Fifteen hundred publications were considered for

this prestigious honor. A few months earlier, he also was awarded a Paul Mellon Senior Visiting Fellowship from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. His conference presentations over the past year included the Seventeenth International Conference on the Inclusive Museum (Vienna, Austria) as well as two sessions at the 2025 International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (Lyon, France). He was a guest lecturer at Cambridge University, the University of San Francisco, and the University of California, Berkeley. He also was a virtual speaker at the Nowruz Lecture in Persepolis, Iran. Here in New York City, Alex organized the conference panel “The Achaemenid Body: Making and Reflecting on Achaemenid Art and Fashion Histories” for the annual conference of the College Art Association.

DOMINIQUE NORMAN presented “Nike and Afrofuturism” at a January 2025 event at Poster House as well as at the Fashion/ Media: Power & Possibility research symposium at Southern Methodist University.

In American Fashion: Ruth Finley’s Fashion Calendar, a book by NATALIE NUDELL , was released in September 2024. Natalie also contributed a chapter on the Ruth Finley Collection to the book Teaching Labor History in Art and Design: Capitalism and Creative Industries, which was co-edited by Kyunghee Pyun. As principal investigator of the Fashion Calendar Research Database (FCRD), she presented at the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations annual conference and at the inaugural symposium of the Fashion Studies Network. Additionally, she was invited to lecture for events at the FIT Library, the Fashion Committee of the National Arts Club, the Digital Humanities Program at Bard Graduate Center, and the Costume Studies Department of New York University. She co-organized an event with the FIT Holocaust Commemoration Committee and the FIT