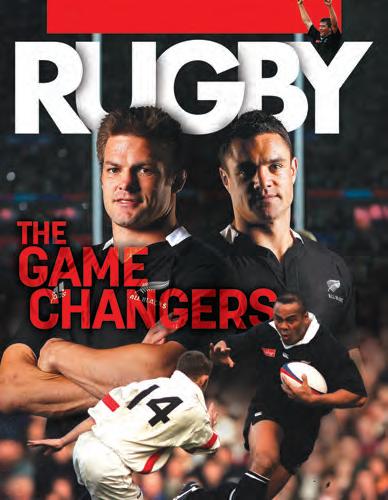

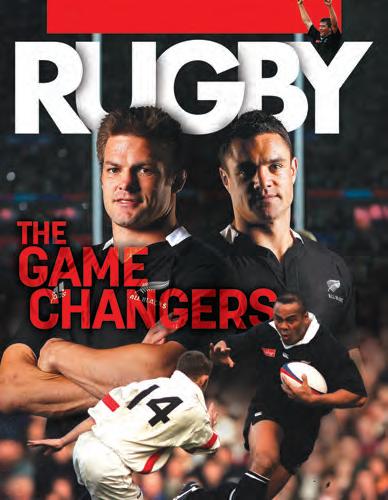

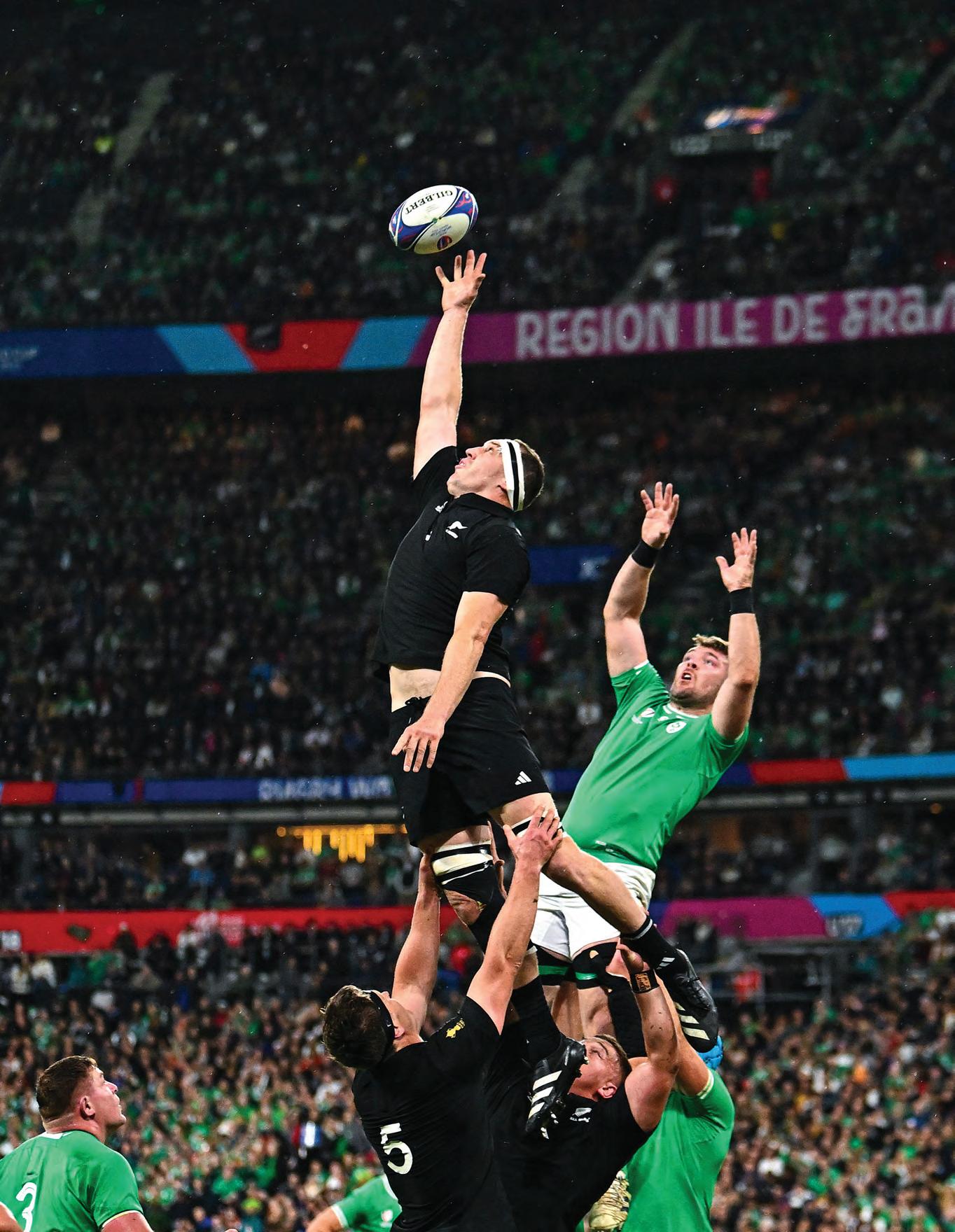

FROM A LONG LIST OF CONTENDERS 15 ALL BLACKS ARE SINGLED OUT FOR HOW THEY CHANGED THE GAME

BY JIM KAYES

FROM A LONG LIST OF CONTENDERS 15 ALL BLACKS ARE SINGLED OUT FOR HOW THEY CHANGED THE GAME

BY JIM KAYES

UNLIMITED SOPHISTICATION. BENCHMARK LUXURY. UNRIVALLED CAPABILITY. The RAM 1500 Limited is New Zealand’s most luxurious full-size pickup truck.

Maximise your slice of the Pie Founder and CIO, Mike Taylor, shares the history behind the Pie Funds name and why it transcends mere corporate identity.

When I first started Pie Funds in 2007, I received plenty of jokes and some genuine confusion, “What do you mean, you don’t sell mince and cheese!”. But 17 years on, “Pie” has grown to over $2.1 billion* in funds under management from everyday Kiwis just like you, and the name “Pie Funds” carries much greater awareness, not just because of our name!

The history of the name

Behind every good name is a story; here’s the story of how Pie Funds got its name.

Back in 2007, well before the iPhone became mainstream, when I was dreaming of being an investment manager, I thought a good name for my business would be ANZAC Funds. A strong name that showed we were focused on Australian and New Zealand investments. But when I heard about the new tax regime, called PIE, or Portfolio Investment Entity, I thought that would be a clever and catchy name with the added bonus of anyone googling “pie fund” seeing my business pop up at the top of the results. I couldn’t believe my luck when I checked the Companies Office!

I registered the name right there and then on the 9th of July 2007.

Fast forward to today, and we’ve made our “Pie Funds” investors around $800m* in wealth, so thank you to all our loyal supporters. So why am I writing about the name now?

Following the trust tax rate increase on 1 April 2024, investors, advisers and accountants are becoming increasingly interested in PIEs.

What is a PIE (Portfolio Investment Entity)?

A PIE is a pooled investment vehicle such as a managed fund, that meets specific criteria set by the Inland Revenue. PIEs generally offer exposure to various asset classes, such as cash, fixed income, or shares, with some holding a mix of these assets. PIEs can provide diversification through the assets they hold, providing benefits that help to manage risk whilst also enhancing returns, and through effective portfolio implementation and rebalancing. KiwiSaver Funds are usually PIEs for this reason.

An important feature of PIE funds is their intended tax advantage vs individual and trust tax rates Investment income in PIE funds is taxed at a maximum rate of 28%, compared to the top personal tax rate of 39% for individuals earning over $180,000 per year. Starting 1 April

2024, trusts earning net income above $10,000 annually will also be taxed at 39%, an increase from the previous 33% rate, and significantly higher than the PIE funds maximum rate of 28%.

By strategically assessing your portfolio and reallocating some investment assets into funds with a PIE structure, you may benefit from the capped top tax rate of 28%. This, combined with the diversification benefits which most PIE funds typically provide, can be a compelling strategy navigating today’s investment landscape. Of course, the tax efficient nature of an investment isn’t the only consideration when constructing your portfolio.

We’d love to talk further with you about your financial goals and objectives.

Pie Funds offers a diverse range of products to suit every investor’s needs. Our product suite covers Australasian equities, global equities, property & infrastructure and fixed income (cash and bonds) and also KiwiSaver.

Get in touch today to discuss your portfolio and how we can become your trusted PIE fund manager.

For over 28 years Cruise World have been curating amazing contemporary, luxury, expedition and boutique small ship experiences to exotic destinations around the globe. Let us chart a course to your next travel adventure. With our experienced team, you’re in safe hands.

We enjoy promoting our wonderful products but more importantly we love finding you the experience that suits you best. Our personal touch ensures we deliver on our motto ‘right guest, right voyage’.

Cruise World travels the world in search of the best products available and our team are here to help navigate a world of experiences. Let our passion fuel your excitement.

You deserve to enjoy your entire travel experience, right from the booking and planning through to your departure date. Travel is one of life’s great adventures and we believe the lead up to and anticipation of your holiday should almost be as much fun as the holiday itself.

We sell travel all over the world but we are proudly a New Zealand owned and operated family business. We support and work closely with our New Zealand based travel agent partners.

It’s a fact. The straighter your drives, the longer your drives.

The G430 MAX 10K’s record-setting MOI puts you in the fairway and closer to the green.

Carbonfly Wrap crown saves weight to help lower CG and reduce spin.

Combined MOI exceeds 10,000 g cm 2

Perched above Queenstown with sweeping views of Lake Whakatipu and the surrounding mountains, Hulbert House is more than just a place to stay—it’s an experience steeped in elegance and history. A beautifully restored 1888 Victorian villa, this boutique hotel offers an intimate and tranquil escape, where each of the six individually styled suites and one Queen studio, invites guests into a world of timeless charm.

The warmth of the team, combined with thoughtful touches such as nightly turn-down service, indulgent breakfasts, Bath Butler experience, and curated local recommendations, creates a stay that feels personal and utterly luxurious. Whether you’re nestled by the fireplace in the inviting Palm Lounge or relaxing on the veranda taking in the memorable landscape, Hulbert House offers an oasis of calm just moments from the vibrant heart of Queenstown.

Perfect for romantic getaways or those seeking a retreat from the everyday, Hulbert House seamlessly blends sophistication with heartfelt hospitality, making it one of the most dreamy places to stay in New Zealand. Here, every detail is designed to make you feel at home, while the setting ensures you never want to leave.

hulberthouse.co.nz

Ilove the concept of a “game changer”. For so many of us who plodded up and down rugby fields, the sight of someone doing something exceptional was a sight to behold.

It still is.

There have been many magnificent All Blacks over the years, but even some of the best did not have a transformative impact on the game: they were simply brilliant in their position. That is not a knock on them. Those types of players are, in fact, a coach’s dream.

But then there are those whose impact is so profound they change the way the game is played and their influence on how we mere mortals view the game extends beyond the time limits of their careers. That sort of player is very special indeed and they are celebrated here.

I’ve also always loved a list. They are subjective, arbitrary even, so there really is not a right or wrong. You might find players on here that you didn’t particularly rate and that’s fine, but hopefully, after reading, you understand why they were game changers.

After careful thought, I’ve decided to restrict my selections to the modern, post-professional era. That has meant some casualties who I could have easily made a case for, like my wonderful mate Sir John Kirwan. Instead, he has helped me form views on those who stretch across these pages.

Thanks must also go to the three coaching knights, Sirs Wayne Smith, Graham Henry and Steve Hansen, for their time and thoughts, and likewise to my Sky Sport colleagues Mils Muliaina, Jeff Wilson and Justin Marshall. Their contributions along with the great Richie McCaw, Keven Mealamu and Laurie Mains have made this magazine possible.

Thanks are also due to Dylan Cleaver for not just editing my work, but elevating it. You are, mate, one of the very best in our business.

And to Don Hope (Publisher), who has the passion and enthusiasm of a man half his age, I salute you!

I am forever thankful to those who have given me the opportunities over the past few decades to write and talk about the great game of rugby, but mostly to my wife, Hiria, and daughters Olivia and Ruth, for tolerating my frequent absences.

Jim Kayes

EDITOR JIM KAYES

CREATIVE DIRECTOR DES FRITH d.DESIGN

SUB EDITOR DYLAN CLEAVER

THANKS TO Sir John Kirwan

Mils Muliaina

Jeff Wilson

Justin Marshall

Richie McCaw

Keven Mealamu

Sir Wayne Smith

Sir Graham Henry

Sir Steve Hansen

Laurie Mains

John Hart

PUBLISHER

DON HOPE don@hopepublishing.co.nz

PHOTOGRAPHY Getty Images

PRINTING SCG

DISTRIBUTION Are Direct NZ

2O

THE GAME CHANGERS

38 58

28

48

7O

8O

9O

1OO

11O

122

DAN CARTER

134

BRAD THORN

AARON SMITH

COACHES HENRY, SMITH, HANSEN

DANE COLES

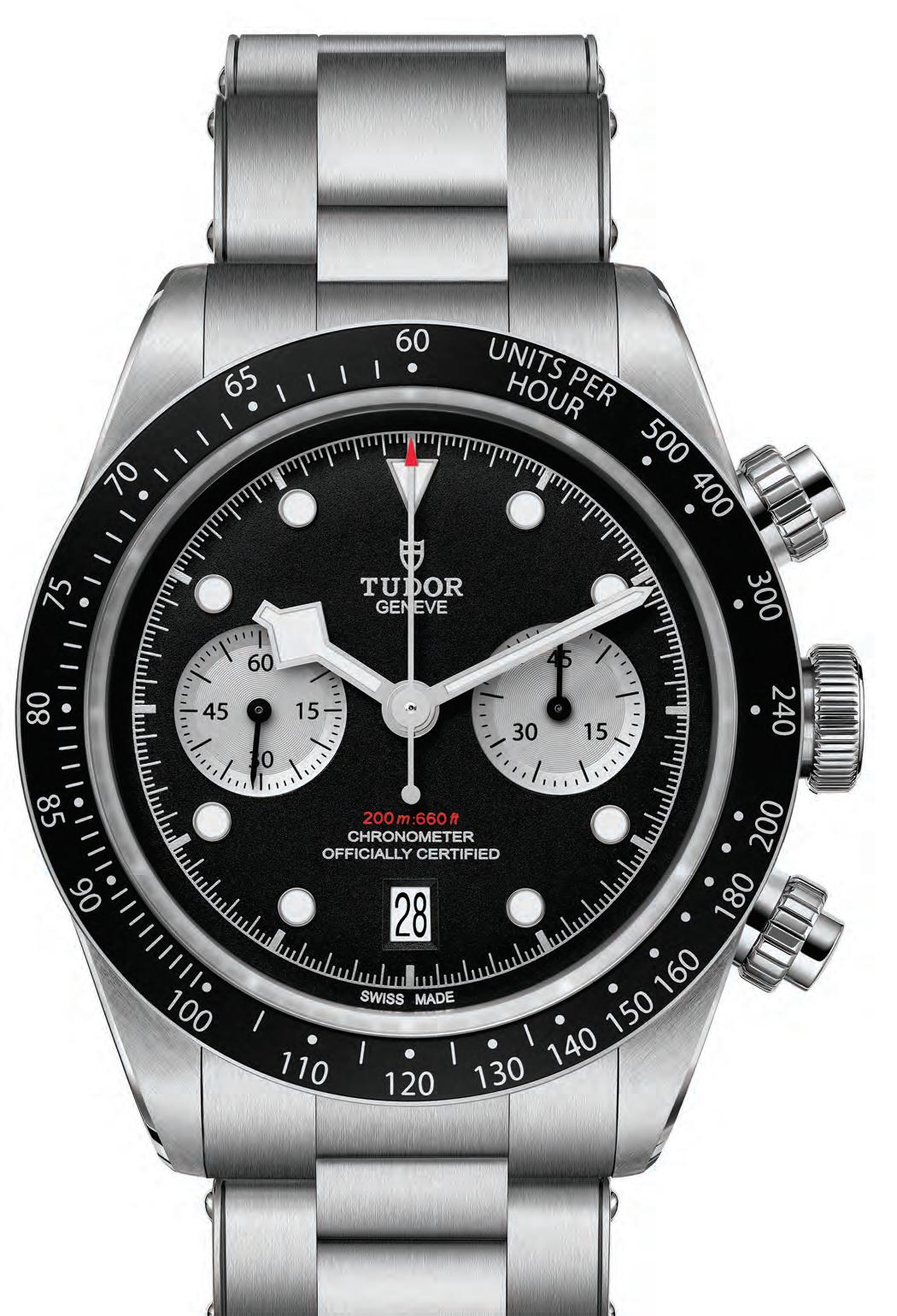

BORN TO DARE TUDOR

Introducing five new models to the PLD Milled family, tour-validated designs that can be custom-built for you: the Anser, Anser 2D, DS72, Oslo 3 and Ally Blue 4. The variety ensures a choice to match your stroke and eye, and they are milled to perfection and feature a gunmetal finish. Tour-preferred deep AMP grooves produce a soft feel for precision and control.

FROM A LONG LIST OF CONTENDERS 15 ALL BLACKS ARE SINGLED OUT FOR HOW THEY CHANGED THE GAME ON THE FIELD, AND OFF IT.

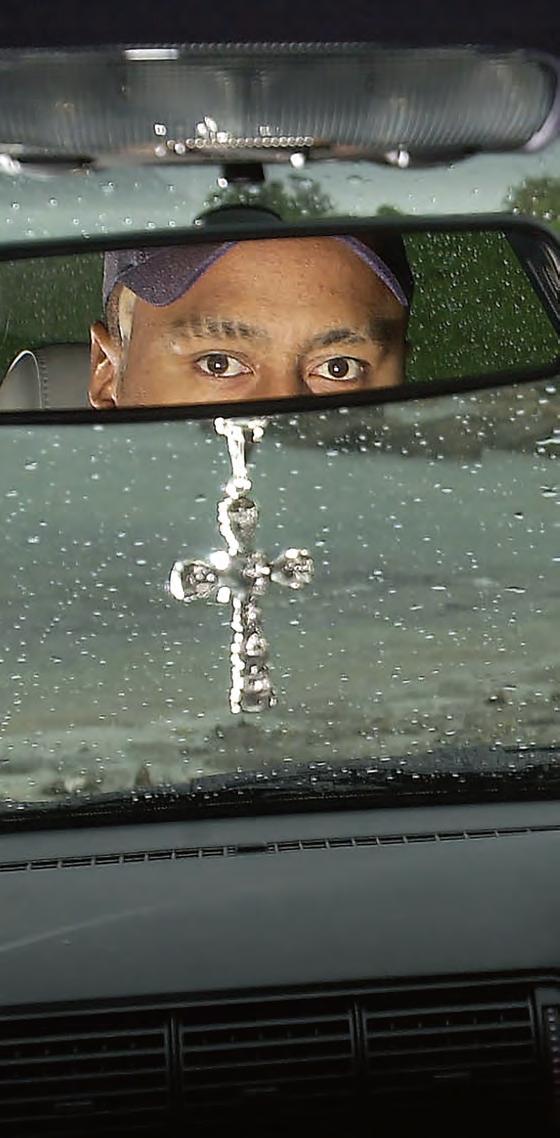

It was an awful Wellington day, with that horizontal rain and a wind that seems like it’s cutting though you like a circular saw.

Yet here was Jonah Lomu sitting in the driver’s seat of his luxury car with all the windows down and the rain pouring in, soaking the leather seats. The flash from the photographer’s camera was competing with the lightning outside as Lomu stared into the car’s rear-view mirror, the No 11 shaved into his left eyebrow the focus for the lens.

When Wellington’s two daily newspapers, the Evening Post and Dominion, merged in July 2002 to create the Dominion Post, we were on the hunt for iconic photos for the first edition. I asked Jonah if he would help and he happily agreed, meeting us on the road that acts as a buffer between the sea and the airport. The photographer, Ross Giblin, was trying to get a shot of Lomu staring into the rear-view mirror with that famous left eyebrow peering back at him, but with the car’s tinted windows, there wasn’t enough light.

“What do you need?” Jonah asked.

“Well, I really need the windows down,” Ross replied as we all looked at rain smashing into the panes.

“Let’s do it,” Jonah said.

It was typical of the man: Lomu was generous to a fault and although he was shy about it, he also was aware of his place in history.

When that photo was taken, Lomu was living with the debilitating illness, nephrotic syndrome, which eventually forced him into a life-saving kidney transplant and all but ended his playing days. Through it all he remained a global phenomenon — and not just in rugby playing countries.

“He is the biggest game changer we’ve had,” says Jeff Wilson, who played alongside Lomu in the All Blacks. “I loved playing with him but he gave me nightmares when I knew I had to play against him.”

His impact at the 1995 Rugby World Cup in South Africa saw him catapulted into a stardom he was nowhere near ready for, yet he coped with it as well as he could.

It is amazing, as you will read in the chapter on Lomu, to learn from Ric Salizzo, the All Blacks media manager at the 1995 World Cup, that the giant wing arrived in South Africa to no fanfare. He was a novice All Black who had failed to impress a year earlier and was promptly dropped by coach Laurie Mains. Lomu only just made the World Cup squad, yet by the end of the All Blacks first game against Ireland, Lomu was all anyone was talking about.

By the end of the tournament, he was a superstar and the perfect player to usher the sport into the professional era.

“LOMU-MANIA WAS A PROMOTER’S DREAM AND THE ATTENTION THAT FOLLOWED HIM NEVER ABATED. THERE WERE PLENTY OF PEOPLE WHO CASHED IN ON JONAH’S MARKETABILITY, INCLUDING THIS RUGBY JOURNALIST.”

Lomu-mania was a promoter’s dream and the attention that followed him never abated. There were plenty of people who cashed in on Jonah’s marketability, including this rugby journalist. French publications paid well for stories on the All Blacks, but much more still when they featured Lomu.

As much as he had a transformative impact on the game, Lomu didn’t have the trophies to match it. He won two Super 12 titles with the Blues and an NPC with Wellington, but he was part of All Blacks sides that tripped over at two World Cups, somewhat unluckily in the final in 1995 and more shockingly in the semifinal four years later.

In that respect he has good company within these pages: Christian Cullen, Tana Umaga, Carlos Spencer and Andrew Mehrtens also missed the big prize and the first two never won a Super Rugby title either.

If it is not winning, then, what makes a game changer?

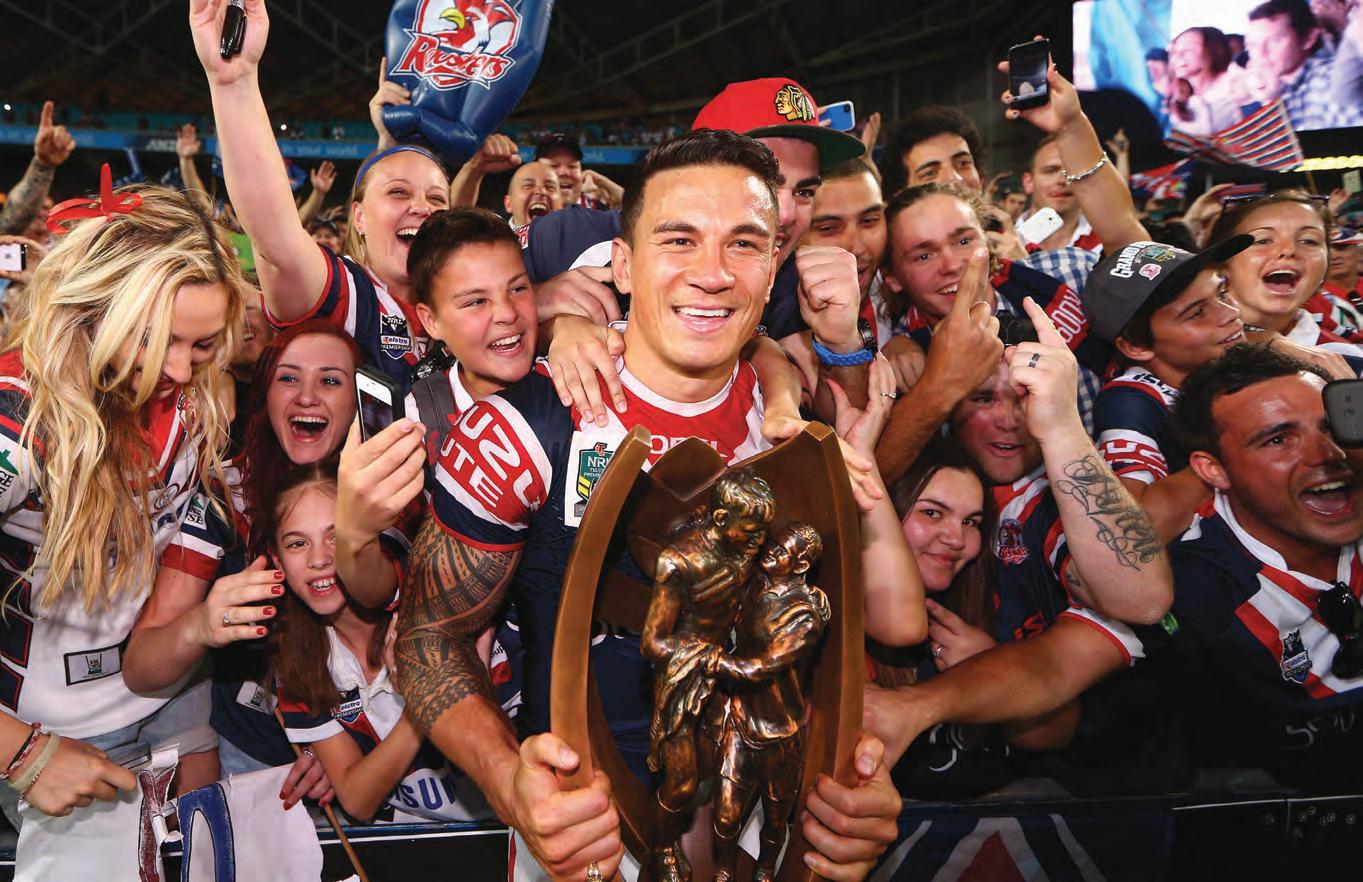

The simplest criteria is that they changed the way their position, and in some cases, the game as a whole, was played. For players like Lomu, Cullen, Spencer, Sonny Bill Williams and our hookers, Sean Fitzpatrick and Dane Coles, what they did with the ball in hand speaks for itself.

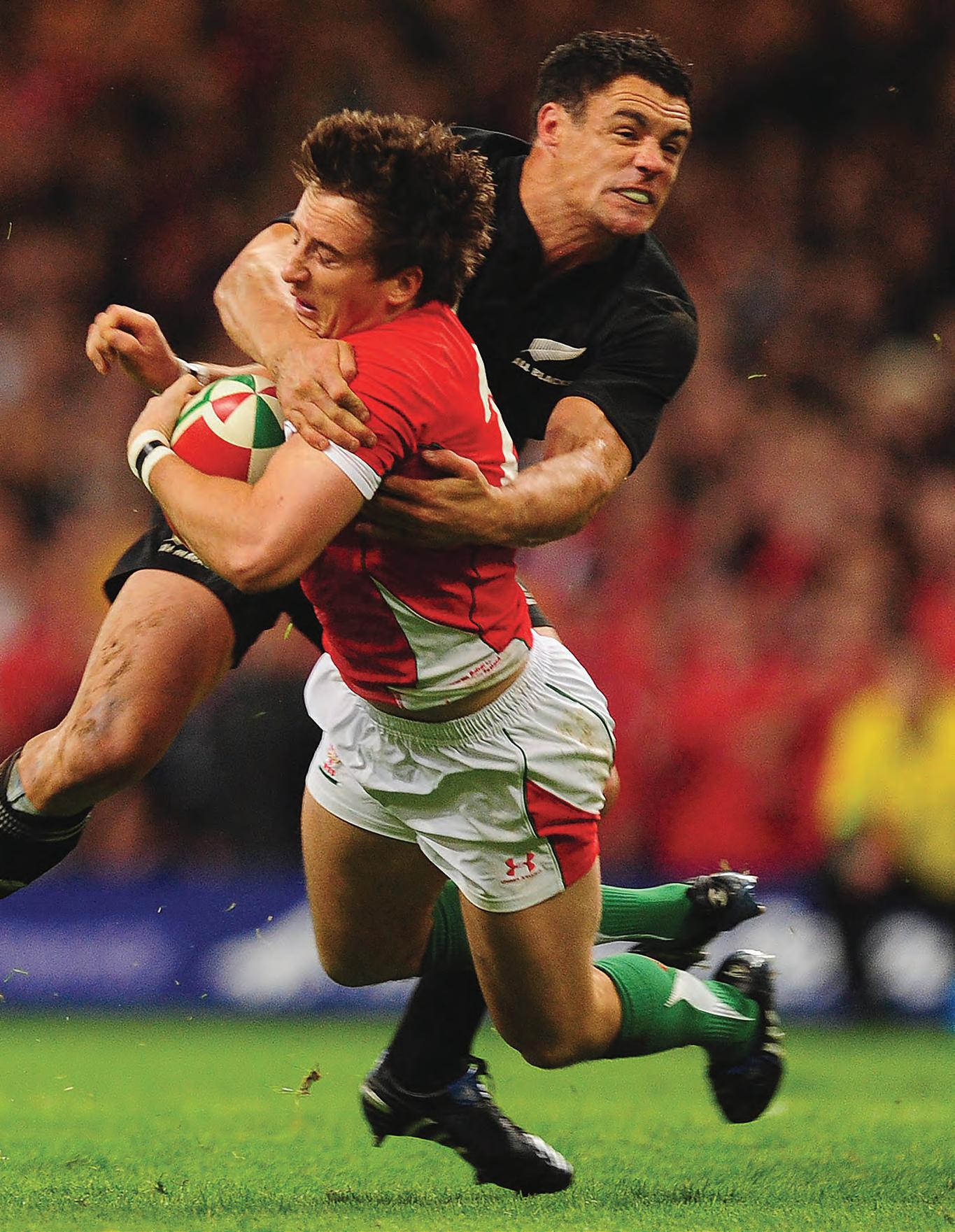

Carter’s performance in the second test against the British and Irish Lions in Wellington in 2005 was hailed as a once-in-a-generation display and catapulted the young first five-eighth into stardom with the notoriously anti-All Blacks English press lavish in their praise.

became the first Pasifika player to captain the All Blacks in a test. The God-fearing cultural mores of Pasifika communities placed a high price on humility and their rugby players were more often than not deferential to authority within team settings, but Umaga changed that — he didn’t defer to authority as much as he was the authority. Young Pasifika players coming through in his wake saw that and in turn grew more confident.

Fitzpatrick also had a massive impact as captain, as did the greatest skipper of them all, Richie McCaw. Both men were omnipresent and each was hugely successful on the field, captaining sides that dominated the international game. Fitzpatrick became the first All Black captain to win a series in South Africa, for so long the Holy Grail of New Zealand rugby, while McCaw twice lifted the Webb Ellis Cup.

Williams is one of two league converts on the list alongside former Kangaroos hard man Brad Thorn. What they brought to rugby was significant — SBW with his offloads and Thorn with his tungsten edge and superhuman work ethic.

“LOMU IS THE DEVIL WE KNOW, CULLEN IS THE ONE WE’RE LEARNING ABOUT.”

– SCOTLAND’S CAPTAIN ROB WAINWRIGHT COMMENTS AFTER CULLEN SCORED FOUR TRIES AGAINST THE SCOTTS, 1996.

Cullen’s running game from the back was freakish, particularly his ability to change direction sharply without losing pace. Although his All Blacks career ended before YouTube started, his career was made for that format and his “Greatest Tries” videos to this day still sparkle and collect views in their hundreds of thousands. I covered his test career from go to whoa and it was stunning, but if there is a game that stands out it was in the modest setting of New Plymouth’s Yarrow Stadium in 2000, when a possession-starved Hurricanes side still managed to thrash the Reds 43-25. Cullen was incredible, helping Umaga to a hat-trick and scoring himself in a breathtaking display of long-range attacks.

Umaga changed his own game, moving from wing to centre and then second five-eighth, but his gamechanging impact was as much felt off the field when he

Williams was also uniquely, outspoken and saw himself as more than a rugby player, with boxing acting as a lucrative second sport. He was a polarising figure who snubbed the All Blacks victory parade after the 2011 World Cup triumph and gave his winners medal away in 2015. It was illustrative of his ability to rub some up the wrong way that Sir Graham Henry chose not to talk about him for this magazine.

Thorn also courted controversy early in his rugby career when he turned down All Blacks selection, saying he didn’t feel he was ready to play international rugby. When he was ready, he was one heck of a player and has amassed more trophies across both codes than any suburban mantlepiece could ever cope with.

My list almost picked itself, but wasn’t without second guessing and the odd change of heart. Jock Hobbs was an early inclusion due to the impact he had in securing the players to New Zealand Rugby contracts when the game turned professional and the anti-establishment rival, the Kerry Packer-backed World Rugby Corporation, threatened to steal the best players away.

As critical as Hobbs’ intervention was, it jarred having an administrator included, even if he was a former All Blacks captain. Equally, game-changing coaches like Sir Wayne Smith were left out so that the focus could stay on the players.

With so many amazing players to pick from throughout history, it was decided to focus on the professional era, thus excluding the likes of Sir John Kirwan, who made the shift to league in 1995.

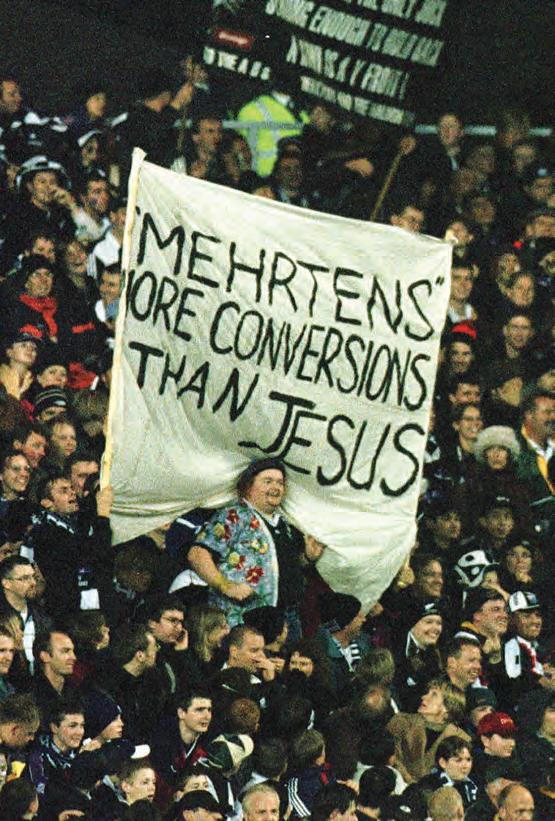

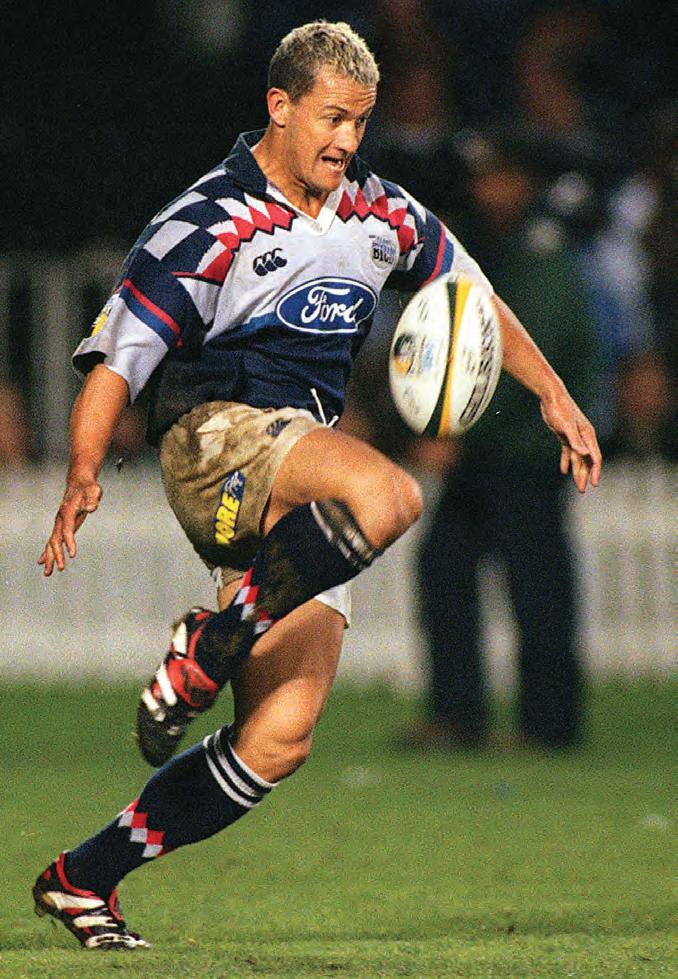

The one player I had not initially considered but was talked into including was Mehrtens. I’d always seen him as a wonderful player but hadn’t necessarily thought of him as a game changer. Jeff Wilson and Justin Marshall convinced me his on-field impact was significant. Off the field he was somewhat revolutionary, too, with his intelligence, wit and willingness to speak his mind with the media cutting against the grain for your typical All Black.

Mehrtens’ propensity for speaking his mind could cause conniptions among NZR management, like when he bagged major sponsor Adidas’ test-match ball, calling it, among other things, a “pig”. Calls from team management for his comments to be treated as off the record were ignored and Mehrtens, to be frank, seemed to enjoy the kerfuffle.

He enjoyed a bit of drama on the field, too, like when he nailed a match-winning drop goal for the Crusaders against the Bulls at Pretoria and saluted the Loftus Versfeld crowd with a universally recognised single-digit salute.

“When the pressure was on he wasn’t fazed by it and didn’t make panicked decisions,” Marshall says of his great mate. “Mehrts would think so quickly that he always made the right decision to get himself out of trouble, or to get us into the right area of the field. That’s uncoachable. I’ve never seen a player with his time and awareness.”

Mehrtens is one of three first-fives in this book, which is perhaps not surprising as it is a position of huge influence and control.

There are two outside backs, or three if we count Umaga as a wing, and two midfielders in Umaga and Williams. There is one halfback, three loose forwards, two locks and two hookers.

It’s an arbitrary list, for sure, and there were many other

All Blacks that might have been included. Wilson was a terrific player who went very close, but Goldie was simply brilliant rather than transformative. The same can be said of try-scoring machines like Doug Howlett, Joe Rokocoko, Sitiveni Sivivatu, Ben Smith and even Julian Savea, who was Lomu 2.0.

Kieran Read was superb, and when he was used as a ball-playing loose forward on the edge, often in combination with Savea, he was close to unstoppable, but as a No 8 he didn’t break the mould and change the game in the way Zinzan Brooke, with his drop goals, long passes and willingness to give anything a crack, did.

I first saw Zinny playing for Marist in the Auckland 3rd grade (under 21) competition in the early 1980s. He was a hard man to miss, especially as he was kicking goals from the sideline. Phil Gifford saw him earlier, when he won a radio competition for shovelling gravel. “There were about 100 contestants, many of whom defined ‘hard bitten’: timber workers, road builders, bushmen from Tokoroa, most with muscles on muscles and tattoos on tattoos, all grimly determined to take home the $1000 prize. We all watched in astonishment as the lanky kid from Puhoi cleaned them up.”

I initially wrote that Brooke was as tough as Buck Shelford. Sub Editor Dylan Cleaver questioned my sanity. “This might be the biggest call in NZ rugby history,” he suggested. “Zinny was tough and unflinching... but was he really as tough and unflinching as Buck?” We tinkered with it as you will see, but I stand by the claim. Zinny was as tough as teak.

Finally, Michael Jones is my favourite game changer, simply because I was an impressionable schoolboy when he came on the scene and I adored the way he played the openside flanker position. Later, after Jones suffered a gruesome knee injury, I admired how he transformed himself from a No 7 with speed, support, timing and skills, to a brutally tough blindside flanker. For connoisseurs of a list like myself, thank goodness he did move to No 6 because choosing between Jones and McCaw as the greatest All Blacks flanker is a thankless task made possible only because the former can be named at six and the latter at seven.

To many followers of the Great Game, this will represent an imperfect list — which is perfectly fine. Sports lists are meant to be debated, just like those about movies, music and books. If yours is different, that’s great, but I still hope you enjoyed sifting through mine.

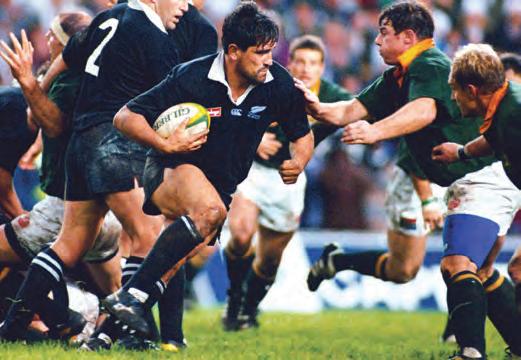

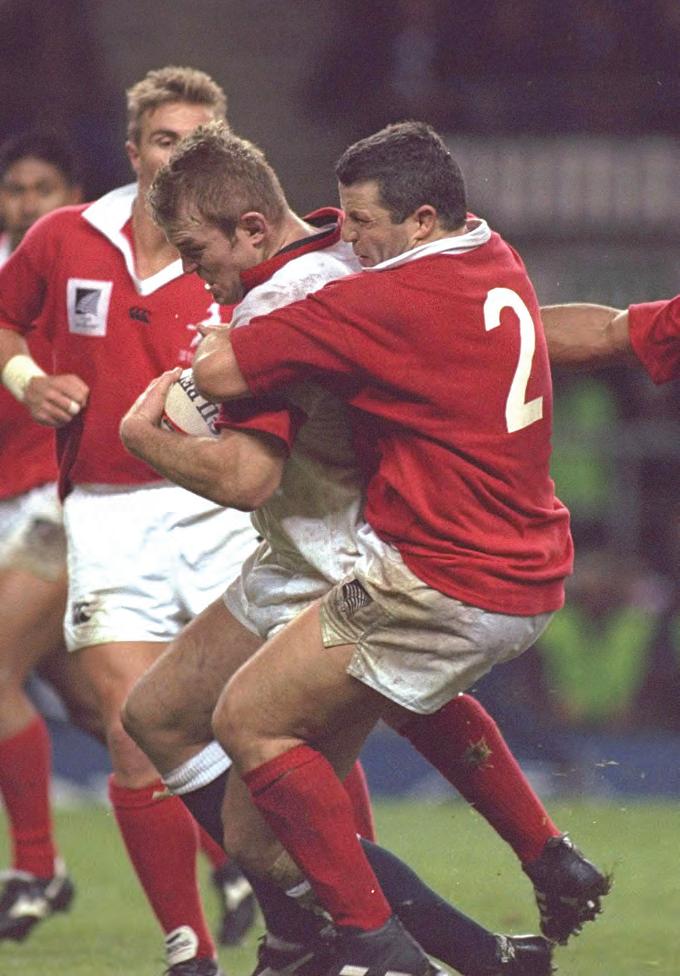

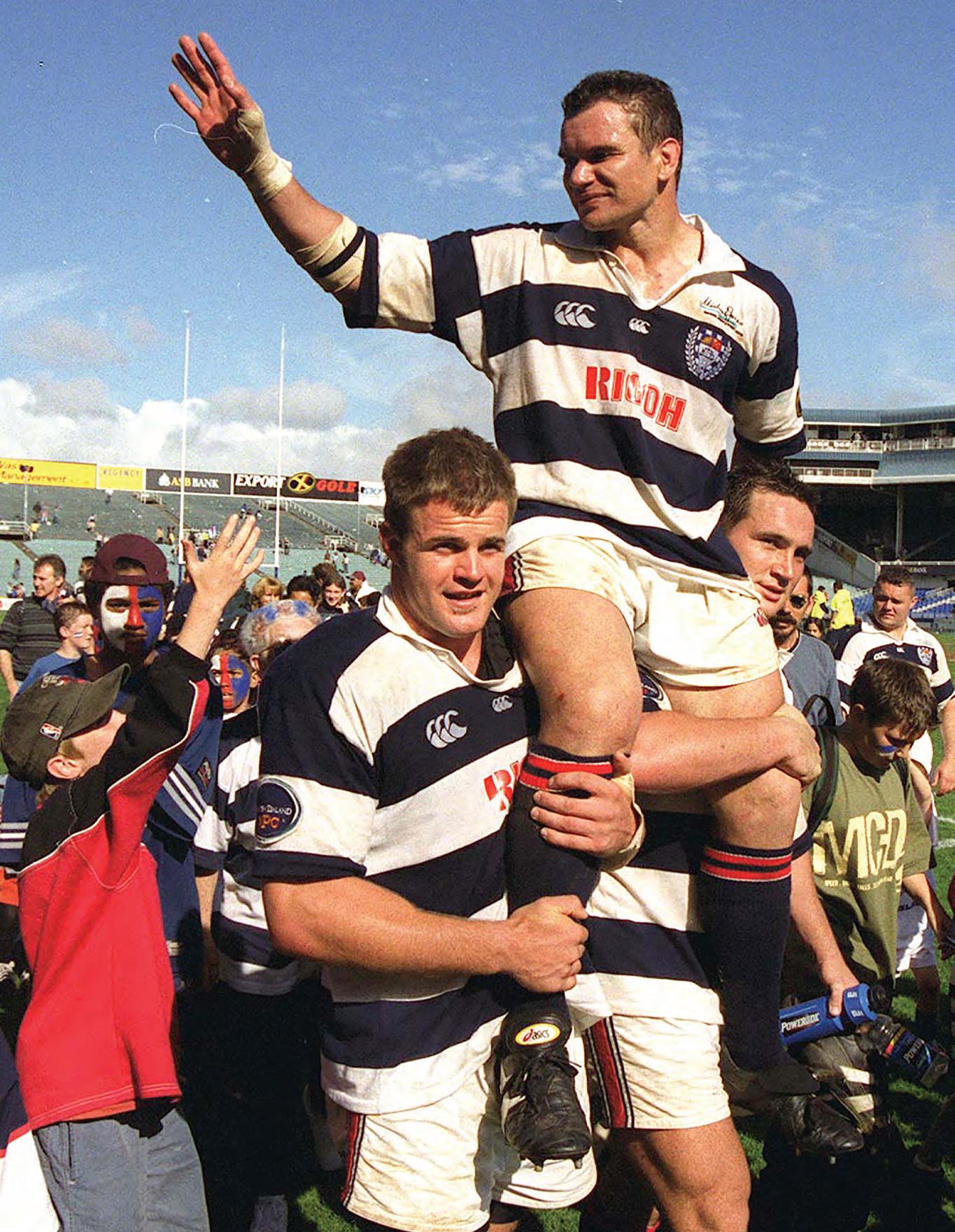

SEAN FITZPATRICK HAD ALL THE USUAL TRAITS OF THE BEST TIGHT FORWARDS, BEING TOUGH AND STREET SMART, BUT IT WAS OUT WIDE WHERE HE FOUND THE POINT OF DIFFERENCE THAT ELEVATED HIM TO THE GREATS.

Sir John Kirwan likes to tell a story about the time he was dropped from the All Blacks.

Coach Laurie Mains told him he wasn’t scoring enough tries as he explained why Kirwan wouldn’t go away on the tour to England and Scotland at the end of 1993. Kirwan retorted that he’d score a lot more “if that bloody hooker wasn’t always on the wing”.

The hooker was Kirwan’s great mate Sean Fitzpatrick. To be fair, Fitzpatrick did score some of his 12 test tries on the wing, with Kirwan often delivering the final pass.

Fitzpatrick was no ordinary seagull, however. He wasn’t scavenging, or glory hunting for selfish reasons. Quite the opposite. He was canny, realising that as the game sped up there was little point in him trying to get from set piece to a ruck on the other side of the field when the play was likely to come back to him.

“Fitzy changed the game,” Kirwan says. “He was the first running hooker who was mobile and wanted to get the ball in his hands.”

It was Fitzpatrick’s willingness to stay out wide that became a hallmark of his game and remains a big part of every hooker’s repertoire, including modern All Blacks like Dane Coles, Codie Taylor and Asafo Aumua.

Sean Fitzpatrick

Born 4 June 1963 in Auckland, New Zealand All Black 871 All Blacks Test Debut Saturday, 28 June 1986 v France at Christchurch aged 23 years, 24 days Test Caps 92 Test Positions Hooker High School Sacred Heart College Club Auckland University

“He realised there was no need for him to clear a ruck that had already been cleaned out by three other blokes just because he was supposed to be there,” Marshall says. “It’s massive intelligence and awareness of where his place could be in the game. Not where it should be, but where it could be. He led the way and all of a sudden you started to see other hookers and props thinking about how they can offer the game more.”

Former All Blacks coach Sir Graham Henry, who coached Fitzpatrick at Auckland and the Blues, said Fitzpatrick’s seagulling never came at the expense of his core roles. “He was a big man, so he scrummaged well, but he was probably the start of the loose forward-style hooker because he had a skill set that was not seen by hookers in those times. He was an extraordinarily skilful hooker.”

Those “extraordinary skills” extended to the dark arts, both subtle and in your face.

“Fitzy was the first guy to really try to manipulate the refs — with a smile on his face,” says Kirwan.

Fitzpatrick was the master at on-field niggle. He infuriated Springbok Johan le Roux so much during 1994’s second test in Wellington, won 13-9 by the All Blacks, that the tighthead prop chomped on Fitzpatrick’s ear. On the same Athletic Park turf four years earlier, Wallabies hooker Phil Kearns was moved to stand over Fitzpatrick while giving him the fingers after scoring a try in a seismic 21-9 Australian victory that shifted the immediate trajectories of both sides.

“He never liked his opposition getting the better of him,” says Justin Marshall, another player noted for living at the extremities of competitiveness. “That’s why he had so many ding dongs. There were some niggly, annoying hookers around during his time and Fitzy was a master at putting people off their game, but it never put him off his.”

Fitzpatrick combined his new-school philosophy on how his position could be played with an amplified old-school mentality about what it meant to be an All Black.

Lineage played a role in that. His father Brian was a midfield back who played 19 matches (three tests) for the All Blacks in the 1950s. Fitzpatrick senior made the All Blacks out of Poverty Bay, where he’d been a teenage

“THERE WERE SOME NIGGLY, ANNOYING HOOKERS AROUND DURING HIS TIME AND FITZY WAS A MASTER AT PUTTING PEOPLE OFF THEIR GAME, BUT IT NEVER PUT HIM OFF HIS GAME.”

Sean Fitzpatrick captained the All Blacks to their first series win in South Africa in 1996.

prodigy at Gisborne Boys’ High. He transferred to Victoria University in Wellington before settling in Auckland, where son Sean cut his own rugby path through Sacred Heart College and the University club.

“I think Fitzy cared the most of any All Black about the jersey. He recognised the significance of leaving the jersey in a better place,” says Marshall, who played alongside Fitzpatrick when they beat the Springboks in South Africa for the first time in a series in 1996.

“IF YOU LOOK AT HIS REACTION WHEN THE FINAL WHISTLE WENT, THUMPING THE GROUND, HE KNEW THE SIGNIFICANCE OF WINNING IN SOUTH AFRICA. NO ALL BLACK HAD DONE THAT BEFORE. NO TEAM HAD BEATEN THEM IN A SERIES BEFORE ON THEIR OWN SOIL. THAT REACTION TYPIFIED HIM.”

“If you look at his reaction when the final whistle went, thumping the ground, he knew the significance of winning in South Africa. No All Black had done that before. No team had beaten them in a series before on their own soil. That reaction typified him.”

Jeff Wilson agrees that Fitzpatrick brought a new level of care to the All Blacks legacy, while also demanding high standards from his teammates and coaches.

“The one thing you never wanted to do was let Sean Fitzpatrick down because you knew he would sacrifice everything for the All Blacks jersey — and I’m sure he would have sacrificed everything for the Auckland and Blues jerseys too,” Wilson says.

“He led by example and by expectation. His standards were high and he knew what it took to be successful and he wanted you to be successful. That is great leadership.”

While Fitzpatrick was synonymous with Auckland, it was an Otago stalwart in Mains who promoted him to test captaincy. It was an unlikely partnership that got off to a rocky start, but proved to be the making of Fitzpatrick.

“Fitzy was part of an Auckland group that misunderstood their role in New Zealand rugby and thought perhaps they were a bit more important than they really were, but I very quickly warmed to him.”

It was an injury to captain-elect Mike Brewer at the All Blacks trials and Mains’ dislike of Gary Whetton that left Fitzpatrick as the only realistic option to lead the team against the World XV in 1992. He went on to captain the All Blacks in 62 of his 128 games (51 times in 92 tests) and was the first out of the tunnel 44 times with Mains as coach.

“I always used to say he had a backbone of stainless steel. He was unbendable,” Mains says. “He had a great ability during a game to assess the best thing he could do whether it was to be on the wing or be right in the middle of the tough stuff. He just seemed to pick it right every time.”

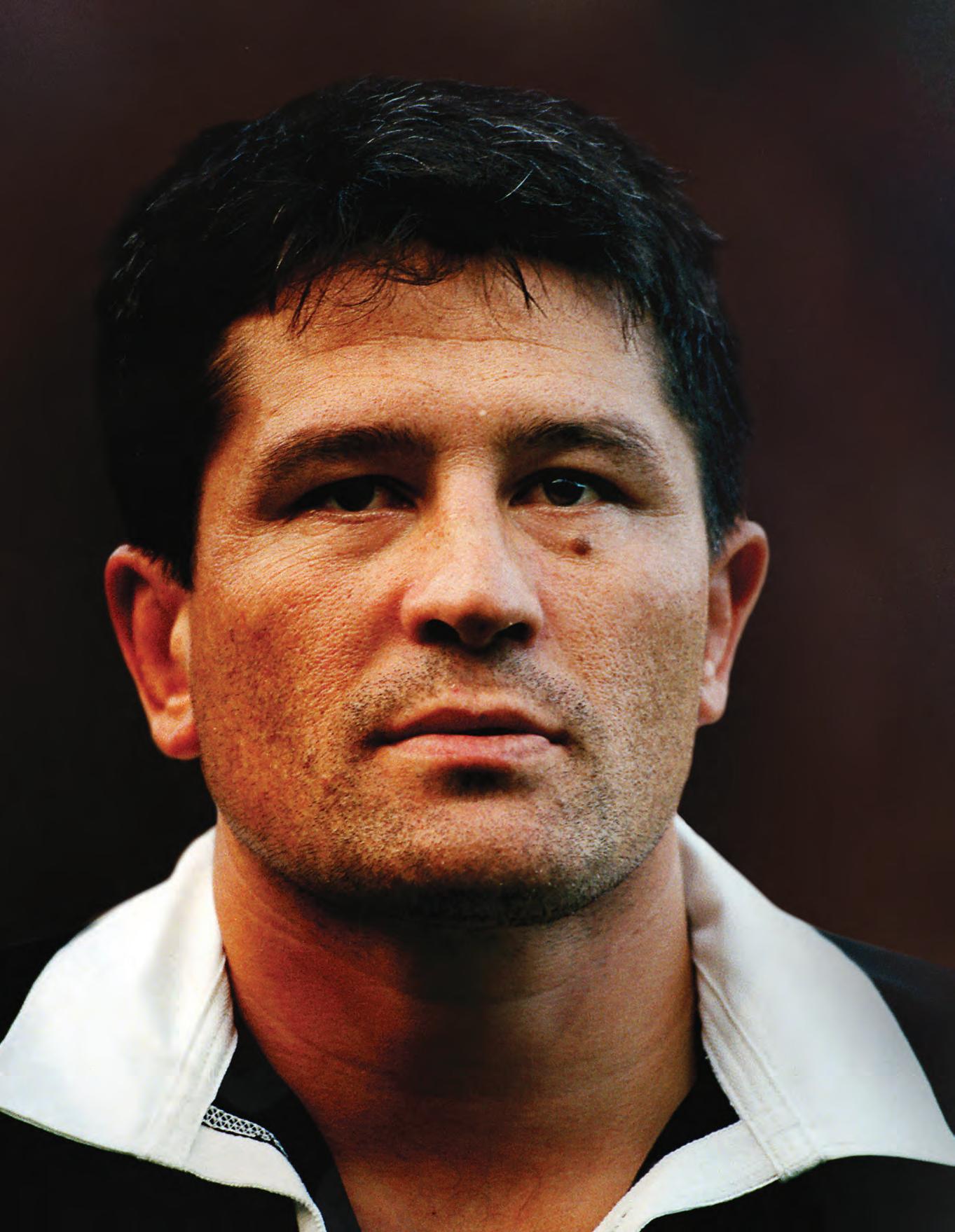

MICHAEL JONES HAD SUCH A DEEP RESERVOIR OF TALENT, NO MATTER WHICH SIDE OF THE SCRUM HE PACKED DOWN ON, HE COULD INFLUENCE TESTS WITHOUT TOUCHING THE BALL.

Michael Lynagh was baffled.

It was the day after a test against the All Blacks and the great Wallabies first-five was telling those at a dinner that he couldn’t believe how little recognition Michael Jones had received for wreaking havoc on the Australian backline.

The celebrated cartoonist Tom Scott, who was at the dinner at Kiwi business tycoon Sir Bob Jones’ Sydney residence, asked what the flanker had done that was so special. “Lynagh said that Jones had tackled him so hard early in the match that it put him off his game,” Scott recalls. “He explained that because it hurt so much he didn’t want to get tackled by Jones again.”

The mere threat of another crunching at the hands of Jones laid waste to the Wallabies backline plans, with Lynagh telling his fellow diners that it led to a succession of poor passes and broken play.

“He’d get the ball from halfback Nick Farr-Jones and would spy Jones coming at him, so he would throw a hasty pass to the second-five, who would also see Jones change his trajectory, so he would throw a hasty pass to the centre,” Scott recounts.

Born 8 April 1965 in Auckland, New Zealand

All Black 882 All Blacks Test Debut Friday, 22 May 1987 v Italy at Auckland aged 22 years, 44 days Test Caps 55 Test positions Openside, Blindside, No 8 High School

Henderson High School Club Waitemata

The end result was a shambolic creep across the field with the wing too close to the touchline to have any impact.

“He didn’t have to touch anyone to completely ruin what we wanted to do,” Lynagh told Scott and those at the dinner, who included the future World Cup-winning skipper Farr-Jones.

Jones’ Auckland, Blues and All Black teammate Sean Fitzpatrick was well aware of the psychological impact an in-form Jones could have on the opposition.

“I remember Nick Farr-Jones telling me that the Wallabies felt if they could keep Michael Jones quiet, they had a chance at beating the All Blacks, because he could dominate a game,” Fitzpatrick says.

“He’s like Dan Carter for me. When Dan dominated a game, the All Blacks won, and it was the same with Michael. He could single-handedly dominate a game, which is quite unusual for his position.”

There are several strands to what makes Michael Jones such a dominant player, but also why he had such a transformative impact on the game. There is Jones the player, but equally there is Jones, a proud product of blue-collar Henderson in Auckland’s multicultural west, the community leader and an inspiration to many who followed in his footsteps.

Jones was an athlete in the truest sense of the word. Tall, muscular, agile and spring-heeled, Jones was quick and strong. He was an excellent basketballer in his youth, which assisted his footwork and aerial skills. All of those physical and technical gifts combined to give the All Blacks something truly unique. “The lines he ran, the short balls, we hadn’t seen a seven play that way before,” Fitzpatrick says.

His opening try at the 1987 World Cup was the perfect distillation of the sort of skills that marked him out as a game changer. Winning a tighthead scrum deep in Italian territory, the All Blacks probed the blind through Wayne

Shelford, Alan Whetton and Grant Fox. When Fox was tackled 10 metres from the line he looked for an inside pass and who was ranging up but Jones, who had run a perfect line to get there from the openside of the scrum. He caught the pass, fended off a would-be tackler and dived full length to score. That spectacular dive has since been immortalised in bronze, with Natalie Stamilla’s statue welcoming visitors inside the gates of Eden Park.

Jones was more than just athletic. He was rugby smart, running incisive lines in the days when an openside supported the inside shoulder of his wings. “When he was a seven I didn’t have to look for him on my wing, I just knew he would be there,” Sir John Kirwan recalls.

Sir Graham Henry, who coached Jones as a blindside flanker at Auckland and the Blues, says he played the game two or three moves ahead of anyone else. “His anticipation was the greatest of any player I coached. He was always in the right place at the right time.”

Jones changed the way we thought about opensides, which is an achievement in itself. To do it again at blindside flanker, where he started 19 of his 55 tests, speaks again to his gamechanging greatness. The switch from number seven to six for the final third of his career was largely due to one of the defining moments of his career: a catastrophic knee injury suffered while playing Argentina at Wellington’s Athletic Park in 1989.

“I ruptured every single ligament in my knee,” Jones would later say, “and I remember the doctor gave me the prognosis that it was the end of my career.

“The injury was like being hit by a car at 40km/h, and it was the worst knee injury the doctor had seen. I didn’t want to give up on the dream; I didn’t want any regrets. It was excruciatingly difficult [to come back], but my faith was important.”

His first-class return was for Auckland against Southland at Eden Park and when Jones took a pass from Terry Wright with about 30 metres to run and no defender in sight, the modest crowd rose to their feet. They were still standing as he ran back to halfway to join his teammates.

“JONES CHANGED THE WAY WE THOUGHT ABOUT OPENSIDES, WHICH IS AN ACHIEVEMENT IN ITSELF. TO DO IT AGAIN AT BLINDSIDE FLANKER, WHERE HE STARTED 19 OF HIS 55 TESTS, SPEAKS AGAIN TO HIS GAMECHANGING GREATNESS.”

A month later, he was back in the All Blacks for the 1990 tour to France, starting at openside in both tests, which is where he would remain through to the end of the All Blacks’ bitterly disappointing 1991 World Cup campaign.

Jones knew he had lost pace and that a shift to the other side of the scrum was inevitable. “I had to reinvent myself,” he said. “I had to live with a lot of related niggle injuries due to the fact my knee was basically reconstructed. I think that’s why my other knee went in 1997, when I ruptured the patella tendon. I lost a metre or two of speed but got wiser and smarter.”

Michael Jones was universally respected for what he did on and off the field.

The man dubbed Ice was as gentle off the field as he was ferocious on it. Asked in the This is Your Life television show how he reconciled his brutal tackling with his deep Christianity, Jones smiled and said: “The Lord says it is better to give than to receive.”

Kirwan still chuckles at the story.

“We used to see tackling as something you had to do before you got the ball back, but Michael thrived on smashing people and we thrived on him doing that. He led the way for others like Jerry Collins and Jerome Kaino who were passionate about smashing people on defence.”

The softly spoken Jones overcame his shyness to become a leader off the field. He was resolute in his faith and his determination to not play on Sundays, even though that saw him miss several key matches, such as the semifinal of the 1991 World Cup when New Zealand were humbled by a David Campese-inspired Wallabies side. That strength of conviction led to the next All Blacks coach, Laurie Mains, omitting him from the 1995 World Cup squad because two pool games and the likely semifinal were on Sundays.

Despite such setbacks, Jones, a Samoan who represented that country once in 1986 before he switched his allegiance to New Zealand, never swayed from his stance and that resonated with many who followed in his footsteps, especially Pasifika players. There had been a sprinkling of others of Pacific Island heritage who had played for the All Blacks, with wing Bernie Fraser and Sir Bryan Williams the highest profile, but Jones captured the attention of a burgeoning Polynesian rugby population.

“He was an inspiration to me,” says 132-test veteran Keven Mealamu. “It’s not just the way he played the game but how he carried himself. He was an All Black who wouldn’t play on Sundays and he stood behind that, saying ‘this is what I believe in, this is who I am’. That stood out to me,” says Mealamu.

“He was a man of values.”

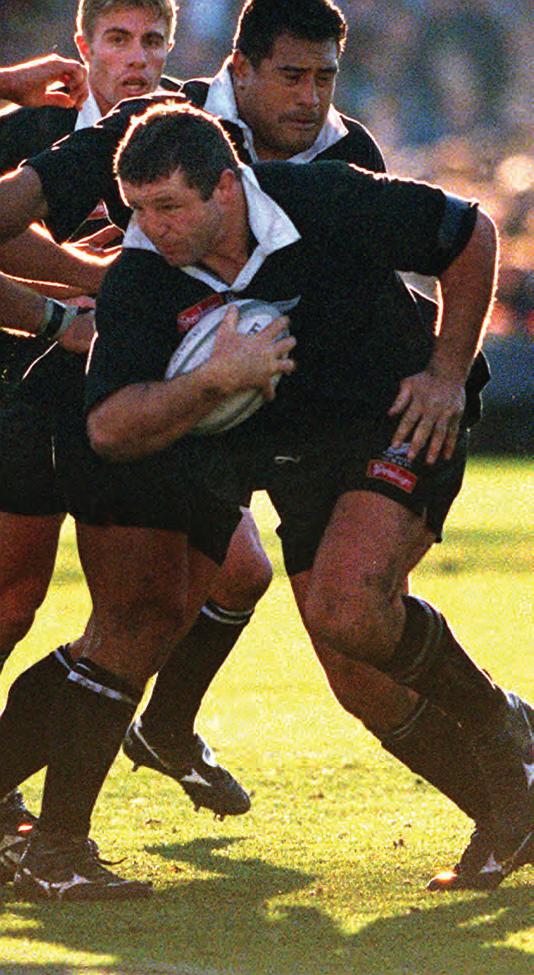

ZINZAN BROOKE COULD DO IT ALL. TOUGH AND UNCOMPROMISING, HE HAD THE SKILLS OF A BACK AND THE COURAGE TO KICK DROP GOALS IN TEST MATCHES.

Jon Preston had never been happier to have the ball bypass him.

Late in the second test against South Africa in Pretoria in 1996, in what became a historic win, the All Blacks led by just four points, 30-26. From a ruck on the 22m line and just to the left of the posts, halfback Justin Marshall looked first at Preston on his right, then turned to his left and fired a pass to Zinzan Brooke.

The No 8 calmly slotted a drop goal, one of three he will kick for the All Blacks.

“We were on either side of the ruck and calling for the ball, and Zinny must have called louder than me,” Preston says. “I wasn’t unhappy when the ball went to him and he slotted it.”

Preston wasn’t shy of pressure — he had earlier kicked a critical penalty immediately after replacing Simon Culhane — but Brooke was the man for the moment.

“Zinny thought he could do everything,” says his long time Marist, Auckland and All Blacks teammate Sir John Kirwan, “and he probably could.

Zinzan Brooke

Born 14 February 1965 in Waiuku, New Zealand

All Black 883 All Blacks Test Debut Monday, 1 June 1987 v Argentina at Wellington aged 22 years, 107 days Test Caps 58 Test positions No 8, blindside, openside High School Mahurangi College Club Auckland Marist

“When you look at Zinny as an athlete, he wasn’t chiselled, he wasn’t cut, but he was tough, he was uncompromising and skilled. He would stay out for an hour after training having a competition with the kickers about who could kick better. He would have a parking competition, just because he could. He never played for fun; he hated losing.”

As talented as Brooke was, it took three years and a controversial dropping for him to establish himself as an All Black. Having shone in the New Zealand sevens team in 1987, Brooke was part of the All Blacks World Cupwinning squad that year, playing in one test, against Argentina, at openside flanker.

It wasn’t until 1990 and in his fifth test, that he got his first start at No 8 following skipper Wayne ‘Buck’ Shelford’s sensational dropping. The axing shocked a nation and saw “Bring Back Buck” signs adorn sports grounds for decades to come. As Shelford’s immediate replacement, Brooke was

the subject of intense scrutiny and criticism. It was probably no surprise that he struggled to become a fixture at the back of the scrum, especially when Laurie Mains won the job to replace co-coaches Alex Wyllie and John Hart at the conclusion of an underwhelming 1991 World Cup campaign.

Mains flirted with Arran Pene and Richard Turner, but Brooke’s skills and competitive drive, and Sean Fitzpatrick’s support, eventually wore the southerner down.

“I wasn’t a big fan of Zinny,” Mains admits. “I was disappointed when Buck Shelford got dropped because I really rated and respected Buck. Fitzy talked me into taking Zinny to Australia in ’92. I said, ‘Okay Fitzy, that’s a captain’s pick and I’ll go with it.’

“Fitzy said to me, ‘You tell Zinny what you want him to do, and he will do it.’ Well I found out over the next four years that whatever you wanted Zinny to do, including playing openside flanker, Zinny could do it. He could do anything.”

Brooke carried much of the blame for Shelford’s axing, as if he had unduly influenced coach Wyllie, but for the all the glitz in his game, with audacious long-range reverse passes or receiving long kicks from the opposition by trapping the ball with his feet, he was tough and unflinching. While Shelford might still be considered the toughest of No 8s, Brooke was no softie.

Veteran journalist Phil Gifford loves to recount the first time he saw a skinny, teenaged Brooke.

“I first met him in 1982 when he was 17, the youngest entrant in a gravel-shovelling contest at a Henderson

hardware store, sponsored by the radio station I was working for. There were about 100 contestants, many of whom defined ‘hard bitten’: timber workers, road builders, bushmen from Tokoroa, most with muscles on muscles and tattoos on tattoos, all grimly determined to take home the $1000 prize. We all watched in astonishment as the lanky kid from Puhoi cleaned them up.”

Brooke was naturally strong from a farm upbringing that saw him shearing 300 sheep a day aged 14. He brought that innate toughness to his rugby with defence nearly every bit as staunch as the hugely respected Michael Jones.

It was his skill set that set him apart, though, and even those who had been on the receiving end of Brooke’s

outrageous talents had to admit he was one of a kind. In 2007, former England centre and captain Will Carling published his list of the “50 Greatest Rugby Players” in The Daily Telegraph, and ranked Brooke the ninth-best player of all time.

“For a forward his skills were outrageous,” Carling wrote. “As comfortable playing sevens as 15s, he had better kicking and handling skills than some fly-halves playing international rugby. You align that with his strength and ability as a forward to read the game — he was unique.”

Carling would have seen Brooke up close and personal when the No 8 signed for his Harlequins club in England in 1997. Professionalism had come just in time for Brooke to put himself on the open market, having previously eyed

“BROOKE

WAS NATURALLY STRONG FROM A FARM UPBRINGING THAT SAW HIM SHEARING 300 SHEEP A DAY AGED 14. HE BROUGHT THAT INNATE TOUGHNESS TO HIS RUGBY WITH DEFENCE NEARLY EVERY BIT AS STAUNCH AS THE HUGELY RESPECTED MICHAEL JONES.”

Ultra competitive, Brooke won 45 of the 58 tests he played for the All Blacks.

up a big-money switch to rugby league. He had in fact signed with the Manly Sea Eagles in 1989 before asking for the contract to be annulled, and he was also close to moving to Japan where his older brother Marty was playing.

Marty had led the way in terms of making the call to join Marist out of Mahurangi College, which was in those days still in the North Auckland union, with North Harbour only coming into existence in 1985. Zinzan followed, as did younger brother Robin.

In age-grade rugby for Marist, Zinny was the long-range goal kicker and he never lost his sight for a goal. With the All Blacks he added the three drop goals to his 42 tries (17 in tests, which was a record) with the famous kick in Pretoria, one a year earlier against England in the 1995 World Cup semifinal and the third in his penultimate test, against Wales in 1997.

“Watching him you saw a guy who was quite prepared to gamble on his skills,” says Marshall, who stood behind Brooke in many of his 58 tests. “The reason he was able to do that was he practised his skills. Anything that was skill oriented, he didn’t believe anyone was superior to him.”

Which brings us back to Loftus Versfeld, Pretoria, and the droppie that drove a stake through Springbok hearts, helping to win the test and a historic series victory in South Africa.

“That did not go according to plan,” Marshall admitted, saying all he could hear was a cacophony of voices calling for the ball as it emerged from the ruck. “As I turned around to pass, I saw Zinny in the pocket and I tried to stop but didn’t and the pass lobbed its way to Zinny. My thought was, ‘What are you doing there?’”

Nevertheless, it left Marshall in the ideal spot to watch history unfold as the ball sailed off Brooke’s boot and over his head.

“He hit it magnificently and I’m thinking, ‘That’s got a chance’.”

Of course it did . It was Zinny.

JONAH LOMU WAS RUGBY’S FIRST TRULY GLOBAL SUPERSTAR. THE SPORT WOULD HAVE GONE PROFESSIONAL EVENTUALLY, BUT THE PAINFULLY SHY KID FROM SOUTH AUCKLAND CERTAINLY SPED UP THE PROCESS.

At a media call to chat with Jonah Lomu ahead of the All Blacks opening World Cup game against Ireland in 1995, nobody turned up.

Lomu and the All Blacks media manager Ric Salizzo waited in the lobby of the team hotel for more than 20 minutes until they realised it was a waste of time.

The no-show might have been frustrating for Salizzo and was probably a relief for the painfully shy Lomu, but it was hardly surprising. Lomu had played his only two tests for the All Blacks against France the previous year and had not impressed. He was dropped after the second test defeat at Eden Park and hadn’t featured in coach Laurie Mains’ plans for the World Cup in South Africa.

It was only after a concerted fitness campaign and an injury to Eric Rush that Mains was persuaded by the senior players to pick the teenager who turned 20 a few days before the World Cup kicked off.

“I’ve often told Rushy the greatest thing he did for the All Blacks was pull a hamstring to let Jonah join the World Cup squad,” Salizzo says with a laugh.

The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

Lomu was outstanding in the opening match against Ireland and the man no one wanted to talk to before the game was all anyone could talk about after it.

Born 12 May 1975 in Auckland, New Zealand All Black 941 All Blacks Test Debut Sunday, 26 June 1994 v France at Christchurch aged 19 years, 45 days Test Caps 63 Test positions Wing High School Wesley College Club Weymouth

“The press conference was packed and every second question was about Jonah. We knew we had a movie star in our ranks,” Salizzo remembers.

By dint of his on-field deeds during those two months in South Africa, Lomu became a global superstar, his four tries in the semifinal against England catapulting him into a sporting and celebrity orbit no All Black had flown in before, or since.

Fame grabbed Lomu and never let him go.

There have been a lot of incredible All Blacks, many of whom have changed the game and their position. Colin Meads was a colossus. John Kirwan was the first of the truly big, strong and fast wings. Michael Jones was an athlete beyond compare who could play all three loose forward positions.

Sonny Bill Williams brought a skill set to rugby the game had never seen before. Richie McCaw dominated the game like nobody else and Dan Carter was simply the most complete first five-eighth the game had seen.

None of those men captured attention like Lomu. As the World Cup unfolded it became standing room only at Lomu’s media appearances, a depth of interest that accompanied him throughout his career. Lomu was often uneasy with the attention, but in his own way was an accommodating subject, even when the interest in him reached tabloid status — especially outside New Zealand. Lomu’s rise to stardom saw him hit the headlines for all manner of reasons beyond the white lines of the field. He

had a computer game and street named in his honour. He was the subject of not one but two This is Your Life shows — one in New Zealand and the other in the United Kingdom. In 2000, he hit the news when a New Zealand First MP urged him to end his bid to have the loudest car stereo in the world, citing the country’s grim hearing-loss statistics among youth. He was often in the gossip-driven sections of newspapers and magazines due to a string of failed relationships and his three marriages, while the revelation that he was battling a chronic kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, which would eventually require a donor transplant, was front-page news and led bulletins.

His commercial heft was recognised by global corporate heavyweights Adidas, who personally sponsored him,

“AS THE ’95 WORLD CUP UNFOLDED IT BECAME STANDING ROOM ONLY AT LOMU’S MEDIA APPEARANCES, A DEPTH OF INTEREST THAT ACCOMPANIED HIM THROUGHOUT HIS CAREER.”

and McDonald’s, which rebranded its McFeast as the Jonah Burger in New Zealand. The NFL, the world’s richest professional sports league, was understood to be keen to tap into Lomu-mania and for a while he was linked with a potential move to the Dallas Cowboys — ‘America’s Team’ — as a one-two punch alongside legendary running back Emmitt Smith.

“ON THE FIELD, LOMU SET THE ATTACKING STANDARD NO OTHER WING COULD EMULATE.”

Yet, despite all his fame and global appeal, when Lomu died aged just 40, it was discovered he was virtually penniless. At his funeral, which was held at Eden Park, the ground where his test career nearly ended after just two appearances, Rush offered the most poignant portrait of his great mate, saying Lomu might have been the most famous player on the planet, but he was also the loneliest.

On the field, Lomu set the attacking standard no other wing could emulate. A schoolboy sensation at No 8, Lomu shifted to the wing at the request of Mains.

“As a loose forward he wasn’t going to be much bigger and certainly not a lot tougher than a lot of the international loose forwards, so his great ability would be nullified to an extent,” Mains says. “But if we were good enough to develop him as a wing, then he could be something the world had never seen and fortunately that was the way it turned out.

“Jonah was the most dangerous rugby player that has played the game, given a little bit of space. He was fast, he could sidestep three metres, or he could go straight over the top of almost anyone and we saw all of that in the semifinal against England at the ’95 World Cup.”

Ahead of his test debut against France, Lomu roomed with Kirwan in Christchurch. The great All Blacks wing preferred not to share his sleeping quarters with forwards and when Lomu knocked on the door the oblivious Kirwan told him he had the wrong room. At 1.96m tall and weighing a muscular 119kg it’s no wonder Kirwan mistook Lomu for the former No 8 he was.

Lomu’s deeds on the field for the All Blacks were indelible, but the raw numbers don’t do him justice. They do, however, show that he was the man for the big stage as 20 of his 37 tries were scored at the 1995 and 1999 World Cups.

After his anonymous start to the tournament in South Africa, a bewildered Lomu soon became the star attraction.

“We were at a shopping mall and a woman asked Sean Fitzpatrick to sign a rugby ball. He had got to about S-E-A when she ripped it out of his hands because she spotted Jonah,” Salizzo says. “No one has transcended rugby like him. Nothing has got close to what happened to Jonah.”

Fitzpatrick, whose legendary career was winding down as Lomu’s was elevating, agrees.

“Jonah Lomu is the only global superstar we’ve had in rugby; there hasn’t been one since and I don’t think there will ever be another player like Jonah. He [went from nobody to icon] in the space of five games — literally five games. When you think about it he shouldn’t have gone to the World Cup, but he came in and totally dominated. By ’96 he had been dropped.”

A major reason for that decline was the kidney illness that restricted Lomu’s international career between the 1995 and ’99 World Cups, when he should have been at his peak.

He missed most of the 1997 test season, but did help New Zealand win sevens gold at the 1998 Commonwealth Games, and he was back near his best at the 1999 World Cup in the United Kingdom.

“HE WAS A GLOBAL SUPERSTAR WHO SCORED TRIES THAT NO ONE ELSE WOULD HAVE SCORED, BUT I ALWAYS THINK, JUST WHAT WOULD HE HAVE BEEN HAD HE EVER BEEN TRULY FIT.” – JOHN HART

Even in the infamous semifinal loss to France, Lomu scored two tries and was one of the few All Blacks who enhanced their reputations that day.

By now, John Hart was the All Blacks coach and looking back he cannot help but lament what might have been.

“He was a global superstar who scored tries that no one else would have scored, but I always think, just what would he have been had he ever been truly fit,” Hart says. “We never saw him at his peak. He was at 60, 70, 80 per cent because of his illness. If he had ever been 100 per cent healthy, what would we have seen? We saw a colossus as he was, but I don’t think we have any idea what he might have done.”

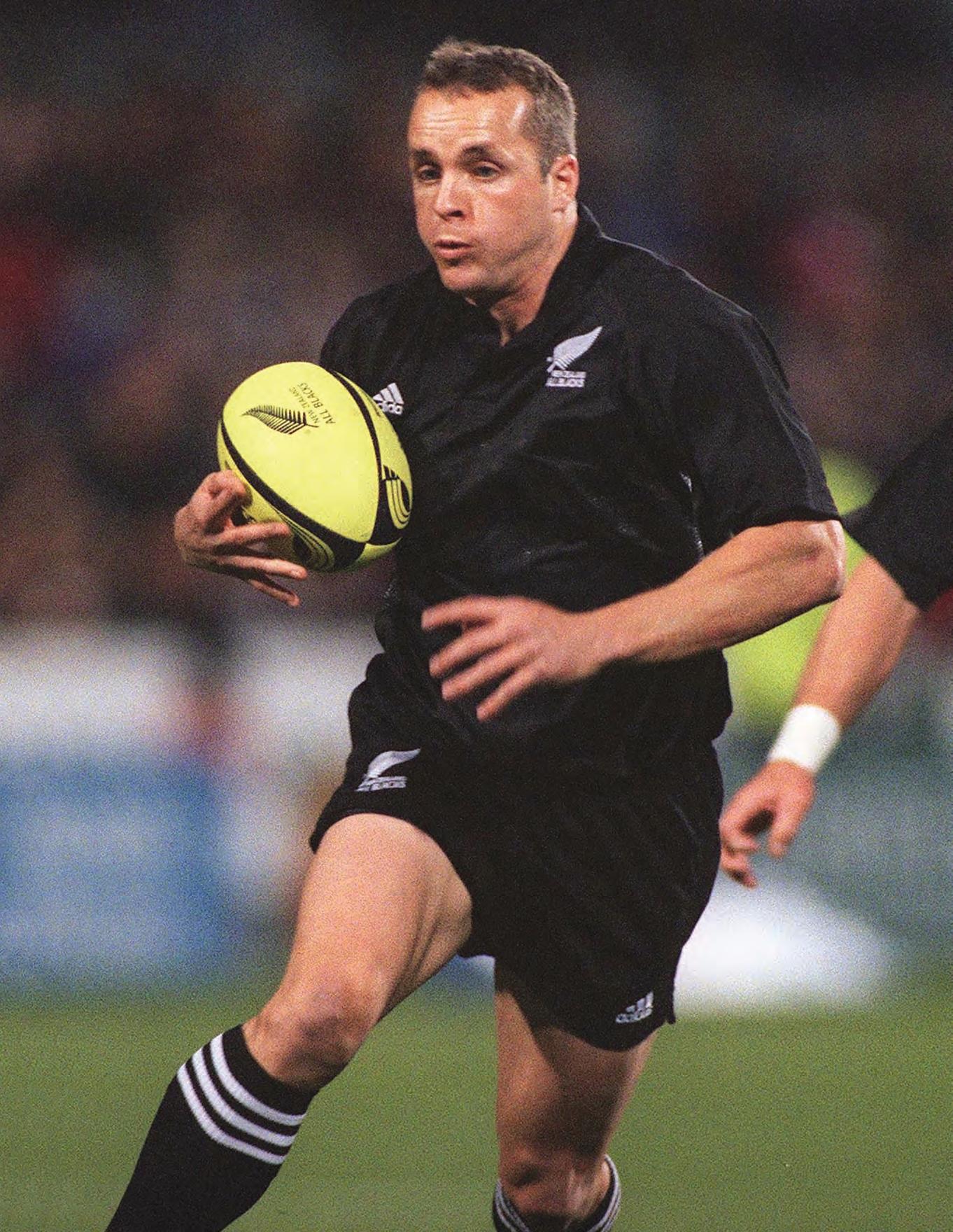

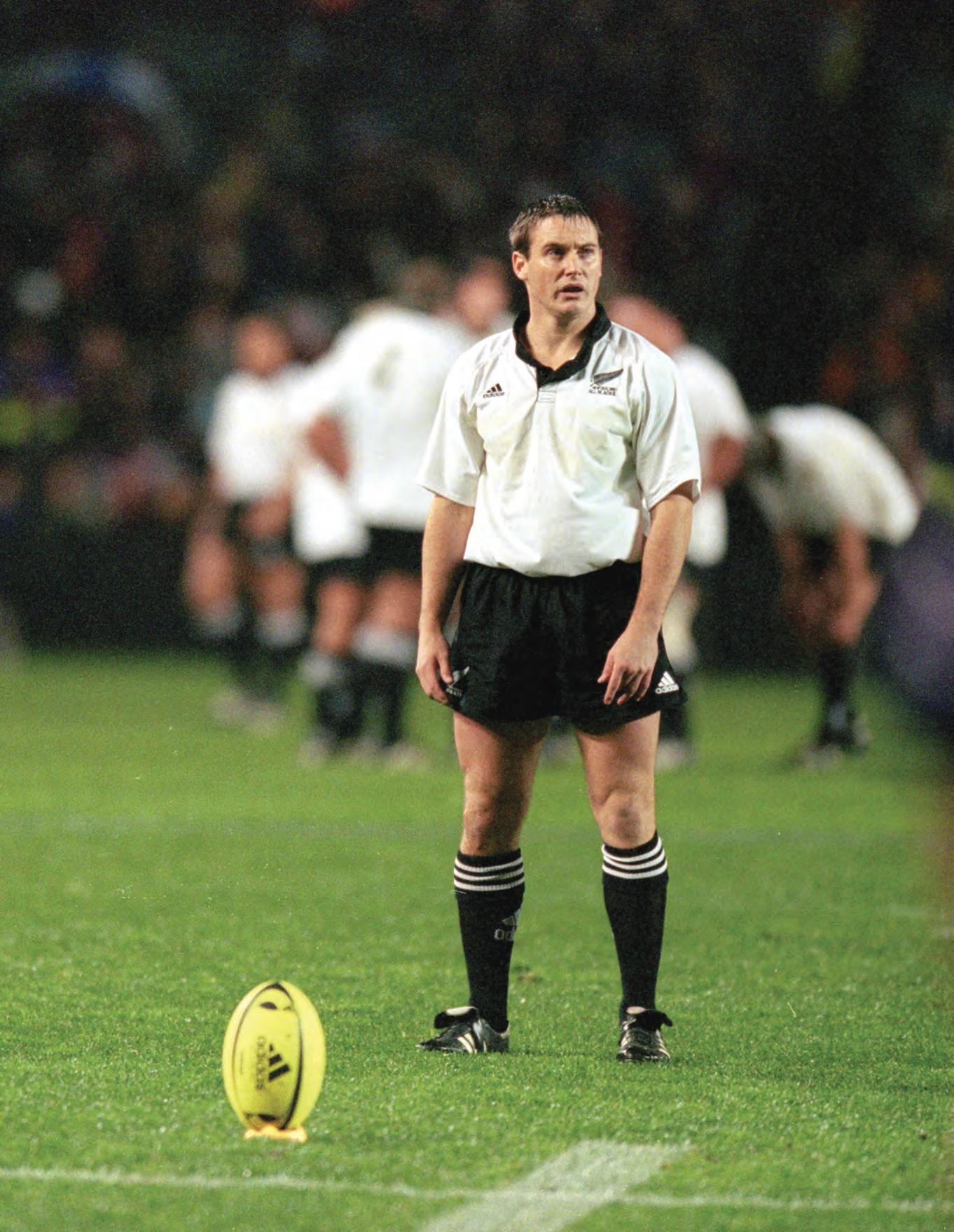

ANDREW MEHRTENS WAS AN EXPRESSIVE PLAYER, ON THE FIELD AND OFF IT, WEARING HIS HEART ON HIS SLEEVE, EVEN WHEN IT GOT HIM IN TROUBLE. HE WAS ALSO ONE HECK OF A PLAYER.

Andrew Mehrtens has always been a maverick.

Who could forget his flipping the bird to the Bulls faithful after a drop goal for the Crusaders at Pretoria’s Loftus Versfeld in 1999. Or, a few years later, when Adidas gave the All Blacks a much-hyped yellow ball to play with against Ireland and Mehrtens dubbed it both a lemon and a pig that wouldn’t fly.

Born 28 April 1973 in Durban, South Africa

All Black 944 All Blacks Test Debut Saturday, 22 April 1995 v Canada at Auckland aged 21 years, 359 days

Test Caps 70

Test Positions

First five-eighth High School

Christchurch Boys’ High Club Christchurch HSOB

For the maligning of a sponsor’s product, he received a ticking off by All Blacks management — they actually tried to stop his quotes from being reported — and the executives at the German sports apparel giants were far from impressed, but Mehrtens was resolute. He knew his way around a decent rugby ball and that wasn’t one.

“The ball is dead. It doesn’t fly and we’ve told them that until we’re blue in the face,” Mehrtens told a couple of intrepid reporters, including this author, the morning after the All Blacks had beaten Ireland 15-6 at Carisbrook in the first of a two-test series in 2002. “The white ball we used in the NPC last year wasn’t too bad. They’ve kept telling us the white and the yellow balls are the same, but they’re not. I’m not using that as an excuse but the ball’s a pig. It’s slippery.”

Team media manager Matt McIlraith tried to stop us using the quotes and later that day manager Andrew Martin called both reporter and editor with the same request.

Mehrtens’ comments carried weight. While Adidas suggested the articulate first-five was trying to deflect from a sub-par All Blacks performance, they also sent the match balls away for testing.

The player himself would have chuckled as he watched the story gather momentum. He never stressed too much. He was a gift for journalists of that era because he was one of the few prepared to be open and honest in his media interviews and he wore his heart on his sleeve on the field. You were never short of angles and stories when he was around, which must have driven his more media wary coaches and managers to distraction.

Against the Bulls that day in Pretoria, the Crusaders were under huge pressure and Mehrtens had been copping abuse from the crowd whenever he lined up a kick. So, when the match winning droppie sailed through the posts, he vented with two single-fingered salutes.

Justin Marshall, who played inside Mehrtens for Canterbury, the Crusaders and All Blacks, says one of his mate’s greatest strengths was his ability to deal with pressure — to ignore the weight of the occasion.

“When the pressure was on he wasn’t fazed by it and didn’t make panicked decisions. Mehrts would think so quickly that he always made the right decision to get himself out of trouble, or to get us into the right area of the field. That’s uncoachable. I’ve never seen a player with his time and awareness.”

The great Colin Meads once dubbed Mehrtens a “cheeky little bastard” but he almost wasn’t afraid to tell all who would listen that he thought he was the best first fiveeighth New Zealand had produced. There was indeed, underneath all the wit and wisecracks, a serious side to Mehrtens the rugby player.

“He was a larrikin, he liked to have a bit of fun, but when he walked onto the pitch he was green for go,” Steve Hansen says.

Born in South Africa while his parents were there on a working holiday, Mehrtens had a strong pedigree. His grandfather, George, played for Canterbury in the 1920s as a fullback and was an All Black in unofficial internationals against New South Wales in 1928. His father, Terry, also a first-five, represented Canterbury between 1964 and 1976, was a New Zealand under-23 player, and while living in South Africa played as a fullback for Natal against the 1970 All Blacks.

It was therefore fitting that Mehrtens, with just one test against Canada in Auckland under his belt, truly burst onto the international scene in South Africa at the 1995 World Cup, alongside fellow newbies Jonah Lomu and Josh Kronfeld. Mehrtens had an outstanding tournament, but as we all know history is written by the winners and what he’ll best be remembered for is missing a match-winning attempt at a drop goal in normal time, while his opposite Joel Stransky nailed his in extra time.

It was the high point of Stransky’s career, while Merhtens kept growing his legend across 70 tests and 967 points.

“The timing was right for him,” says Jeff Wilson. “He was a confident young man with a great skill set, good athlete, great speed and a great kicking game as well. He played on instinct. If the best option was to run, he would take that and he had great fast hands so as a teammate you had to be ready to react because he had the ability to change the game in a second.”

One thing Mehrtens was not renowned for was his defence. All Blacks coach Scott Robertson often jokes that playing alongside him for Canterbury and the All Blacks boosted his tackle count as he had to make the first-five’s as well. If he was poor on defence, Mehrtens was a genius with the ball and his speed allowed him to ghost across the field before straightening either to take the gap himself or put someone else in it.

Hansen first coached Mehrtens at club level in Christchurch and vividly remembers chatting with the 18 year old on his front porch about how he would cope in a team full of seasoned men.

“I wasn’t sure that he could lead the team because he was only a baby and I’ll never forget he said, ‘I’ll run the team Steve, don’t worry about that’. He wanted to be in charge, doesn’t matter what it was,” Hansen says. “If you were playing a game of cards he wanted to be in charge, if you were doing the dishes he wanted to be in charge. That’s one of the things that made him a great player, but he also had the time and space to play a game of footy that at that time no one else could play.

“His passing game was unbelievable. He could throw the ball 25 metres and put it on a dime and his kicking game was great. He certainly changed the game. Grant Fox was a great player but he didn’t have Mehrts’ running game. Carlos had the running game but he didn’t have the same tactical nous as Mehrts. He was a combination of both Foxy and Carlos and that is a rare commodity — and he had a massive influence on the next guy, who was Dan Carter.”

Mehrtens enjoyed huge success with Canterbury (scoring 1056 points across 108 games) and the Crusaders (87 games, 990 points), and saw off three strong contenders in Carlos Spencer, Tony Brown and Simon Culhane, who played 59 tests between them, to be the regular first-choice No 10 for most of his time as an All Black.

After he stopped playing in New Zealand, Mehrtens had stints with Harlequins in England and Toulon, Racing Metro and Beziers in France. Since retiring, Mehrtens has lived mainly in Australia and has been a kicking coach for the Waratahs. His intelligence and wit means Mehrtens is a popular after-dinner speaker and he has enjoyed regular work as a pundit on Australian television where, it should surprise nobody, he likes to crack a joke from time to time and treats the game as something less than a life-or-death matter.

CARLOS SPENCER WAS A SCHOOLBOY PRODIGY WITH A RANGE OF SKILLS AND BAG OF TRICKS THAT HIS FANS LOVED AND DETRACTORS DETESTED.

Born 14 October 1975 in Levin, New Zealand

All Black 951 All Blacks Test Debut Saturday, 21 June 1997 v Argentina at Wellington aged 21 years, 250 days Test Caps 35 Test Positions First-five High School Waiopehu College Club Ponsonby

It has become something of an iconic YouTube clip — and it got veteran radio broadcaster Brian Ashby into hot water.

Playing for the Blues at Christchurch’s Lancaster Park, Carlos Spencer caught a pass on his line with two Crusaders players bearing down on him. Spencer threw a long pass across the front of the posts to wing Joe Rokocoko, who launched a daring break out before passing to Justin Collins. The flanker in turn found Spencer on his shoulder, who proceeded to race toward the Crusaders’ posts for a stunning try.

Except he didn’t put the ball down straight away, as is customary. Spencer instead trotted to the corner, where he placed the ball just inside the deadball line, then kicked the conversion from out wide and sealed the deal by flipping the finger to an infuriated and febrile Christchurch crowd.

It was vintage, swaggering Spencer, but as he ran toward the sideline, Ashby, calling the game on Radio Sport, let rip.

“I think I said something along the lines of, ‘He’s been superb tonight but now he’s behaving like an absolute dickhead’,” Ashby says, recalling the 2004 Super 12 game won 38-29 by the visitors. “I reasoned at the time that giving himself a sideline conversion wasn’t the best idea. Just a few months earlier, he’d had the goal kicking yips at the World Cup. Had he missed on this night, the Crusaders would’ve secured a bonus point which could’ve proved crucial later in the season.

“He nailed it beautifully.”

Ashby was given a ticking off by his boss, talk-radio legend Bill Francis, who told him that it wasn’t appropriate language in a commentary. Ashby stands by the rationale for his outburst, however, and for balance adds that he was critical of the crowd throughout the match for their boorish behaviour toward Spencer. Fair comment or not, it wouldn’t have bothered Spencer who delighted in winding up opposition crowds as much as he enjoyed running at tiring forwards.

Spencer was a polarising figure whose maverick play thrilled his fans, who dubbed him King Carlos, but infuriated those who thought he was a show pony. While he had fans and detractors in all corners of the country, as a general rule the bulk of the first group lived in Auckland while the second group resided in the South Island — and Canterbury in particular.

Exacerbating matters was the fact that he was in a battle for the All Blacks first five-eighth slot with Canterbury’s favourite son, Andrew Mehrtens, and Otago’s cult-hero Tony Brown.

Never outwardly short of confidence — he starred, topless and rippling with muscles, in a Toffee Pops commercial — Spencer was ahead of his time when it came to flair on and off the field. He delighted his fans with a dazzling array of skills that included corkscrew kicks, using his knee or thigh to chip and chase, through-the-legs passes and passes to himself that dumbfounded defenders. He also retained a canny ability to isolate lumbering tight forwards to run at.

Jeff Wilson says much of what Spencer did was far

from the orthodox or the percentage play but it was his confidence to have a crack, even in the All Blacks, that made him so special.

“If it comes off, fantastic, but if it doesn’t you have to live with the consequences and that was Carlos — he was always happy to live with the consequences because he had worked on it so much that it was a calculated risk.”

Spencer’s daring play was almost a push back against the hyper-analysis and structured play that came in with professionalism.

“We went from planning two or three phases to five or six, so the play was a lot more patterned and players knew the areas they had to be in,” says former Crusaders

“IF

IT COMES OFF, FANTASTIC, BUT IF IT DOESN’T YOU HAVE TO LIVE WITH THE CONSEQUENCES AND THAT WAS CARLOS — HE WAS ALWAYS HAPPY TO LIVE WITH THE CONSEQUENCES BECAUSE HE HAD WORKED ON IT SO MUCH THAT IT WAS A CALCULATED RISK.”

and All Blacks halfback Justin Marshall. “Within those patterns, if Carlos saw something, he would take it. If he saw a defender he could beat, he would take him on and I would always feel sorry for the forwards he preyed upon.

“He was happy to gamble on his skills and his skill set was off the Richter scale. His ability to pass pre- or post-contact off either hand, one-handed offloads, and his ability to see who was coming at him and use those around him — he was a genius at that.”

“HE WAS HAPPY TO GAMBLE ON HIS SKILLS AND HIS SKILL SET WAS OFF THE RICHTER SCALE.”

Yet his cavalier style didn’t always impress the selectors at the international level. Spencer played 35 tests to Mehrtens’ 70, despite them both making their debuts for the All Blacks in 1995, and playing their final tests in 2004.

Mehrtens was seen as the more solid option: less flighty, a better positional kicker and thus better able to drive a game and construct wins. Or so conventional wisdom suggested, except that Spencer’s test win rate of 77 per cent was higher than Mehrtens’ 70 per cent.

Spencer’s prodigious talents were recognised early. He made his first-class debut for Horowhenua aged just 16 and while still a pupil at Levin’s Waiopehu College. A year later he scored a spectacular try against Auckland when the blue-and-whites took the Ranfurly Shield on tour and coach Sir Graham Henry was quick to lure him north.

“HE HAD THE ABILITY TO PLAY FLAT, HE HAD THE HANDS AND THE PASS AND THE SKILL LEVEL TO PLAY IN THE TRAFFIC AND CREATE OPPORTUNITIES NOT ONLY FOR HIMSELF, BUT FOR OTHERS. HE HAD THAT CHEEKINESS.”

– GRAHAM HENRY

“He was a genius. I don’t think he knew he was a genius and I don’t know if he always knew what he was doing, but what he did was fantastic,” Henry says. “He had the ability to play flat, he had the hands and the pass and the skill level to play in the traffic and create opportunities not only for himself, but for others. He had that cheekiness.”

Henry says the Lancaster Park try that riled up the locals, including Ashby, should have been scored under the posts instead of the corner flag. “But that was Carlos. He just loved playing in the big environment, with a big crowd. That was his stage, he was an actor, and he loved it and there were not many better.”

AN EXCITEMENT MACHINE, CHRISTIAN CULLEN COULD CHANGE DIRECTION WITHOUT BREAKING STRIDE AND IN DOING SO, RAN RINGS AROUND DEFENDERS, AND HIMSELF INTO THE PANTHEON OF GREATS.

Such was Christian Cullen’s iconic status, it is difficult to reconcile the fact that by the standards of today’s legends, his test career was relatively brief. It is also crazy to think that the fullback who used to run past and around defenders while scoring tries for fun, never got to play a full World Cup campaign in the No 15 jersey.

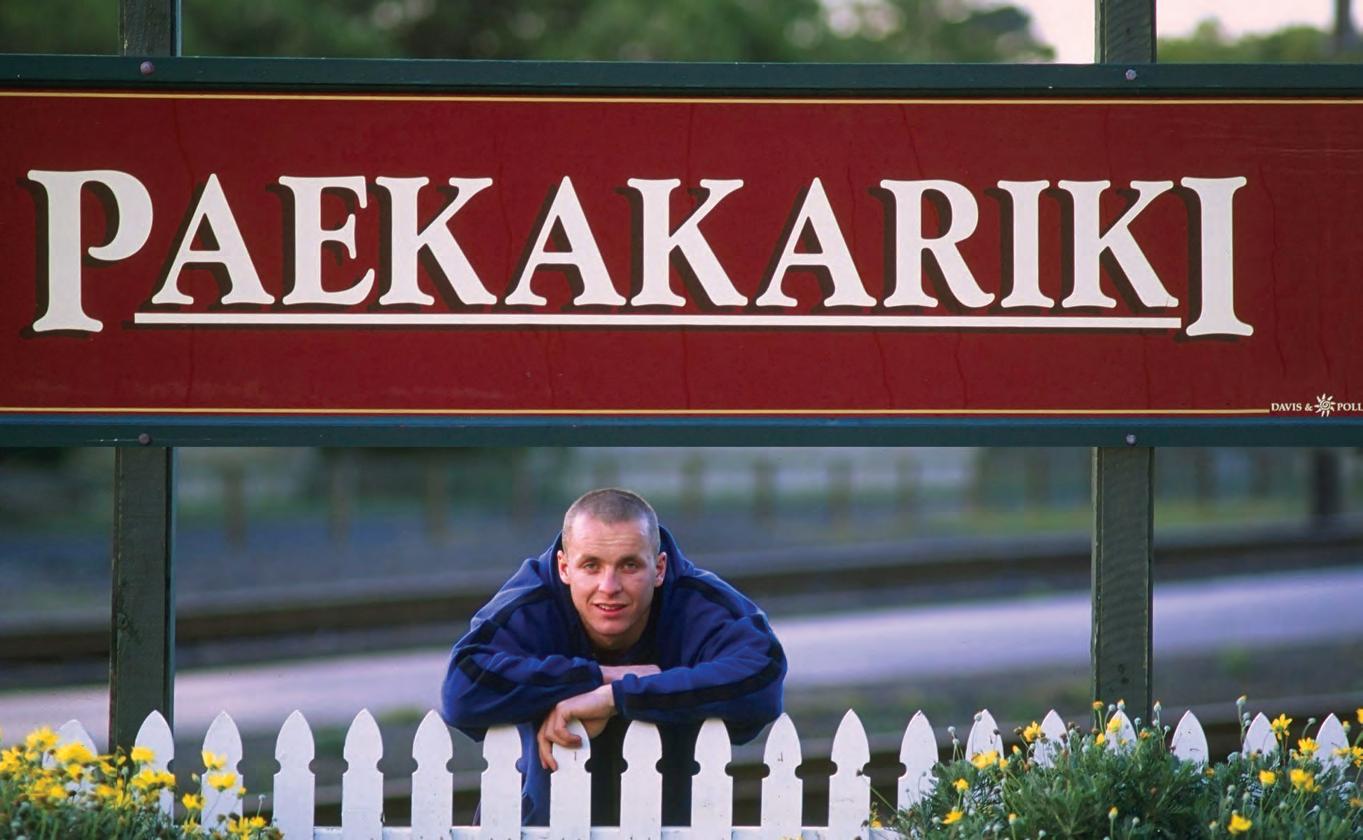

Dubbed the Paekākāriki Express by the Evening Post’s rugby correspondent David Ogilvie, there was no great mystery behind Christian Cullen’s nickname; nothing cryptic that required code breaking.

“I called him that because he was fast and he came from Paekākāriki,” says Ogilvie, who penned the line as Cullen emerged as a free-running fullback in the mid-90s.

From there it took on a life of its own, with a sign erected in his honour at the train station in the small Kapiti Coast town north of Wellington.

Christian Cullen

Born 12 February 1976 in Paraparaumu, New Zealand

All Black 952 All Blacks Test Debut Friday, 7 June 1996 v Samoa at Napier aged 20 years, 116 days Test Caps: 58 Test Positions

Fullback, centre, wing High School Kapiti College Club Kia Toa

Cullen also had a standardbred horse named after him and the four-legged version was a champion in his own right, winning 22 of 31 starts and reaping prize money of $1.25 million. After winning the New Zealand Cup in 1998 with a typically dominant front-running performance the commentator remarked that “in a galaxy of stars, he’s the brightest of all”, and the same might have been said of his rugby namesake, though Cullen the man was very much a thoroughbred.

“He was limitless in his attacking ability,” says Jeff Wilson who would shift from fullback to the wing to accommodate Cullen in the All Blacks. “There was nothing, if you gave him the ball, that he couldn’t do. He was powerful, dynamic, had a fantastic sidestep, was incredibly fast and his fend was strong.

“He added this electricity to the game and the moment it was time to go, he was gone. He didn’t hesitate. He never second guessed himself. He wanted to run, he didn’t want to kick.”

It is that last comment that set Cullen aside from all other fullbacks and was such a large part of how he changed not only the way fullbacks played, but how the All Blacks attacked. The template had been to kick for territory, but Cullen preferred to run there.

“We hadn’t seen that before,” Cullen’s All Blacks skipper Sean Fitzpatrick says. “A player running those sorts of lines — he changed our attack and when we demolished Scotland at Carisbrook in 1996, a lot of that was down to him.”

Cullen scored four tries that afternoon, the first a remarkable effort where he beat his marker on the outside then chopped his way back infield with a series of rightfoot sidesteps. When he dotted down he had either beaten or shrugged off seven would-be tacklers. To prove he was no one-trick pony, his second try saw him execute two massive left-foot steps that left defenders grasping at shadows. All this came a week after he had scored three tries on debut against Samoa in Napier, a test notable for being the first played at night and outside New Zealand’s four main centres.

Night rugby became a permanent fixture as did Cullen, scoring tries for fun as he notched 46 in 58 tests, and more than 150 in a first-class career that spanned more than 200 games.

The All Blacks have had plenty of prolific try-scoring fullbacks, with John Gallagher, Wilson and Glen Osborne featuring before Cullen came along, while Mils Muliaina, Leon MacDonald and Ben Smith were exceptional attacking fullbacks who followed in his wake.

“TO PROVE HE WAS NO ONE-TRICK PONY, HIS SECOND TRY SAW HIM EXECUTE TWO MASSIVE

It was where Cullen launched his attacks from, however, and his ability to change angles without slowing down, that set him apart.

Those talents were well known in the age-group system, despite Cullen attending his local Kapiti College, which was not a noted rugby nursery. He made his first senior appearance at the 1995 Hong Kong Sevens, back then the gold-standard tournament for the truncated version of the game, and although he scored a try in his first game, he spent the rest of the tournament watching from the sidelines as New Zealand went on to win.

The following year it was a different story, with Cullen scoring 18 tries and marking himself down as a young man for the big occasion when creating a breathtaking try from difficult circumstances in the final against crowd favourites Fiji. With New Zealand under pressure from a sloppy lineout on their line, Bradley Fleming shovelled the ball under pressure to Cullen, who caught it deep in his in-goal. Cullen cut against the grain, skirting the dead-ball line while escaping the attentions of

three Fijian defenders, before surging clear through the posts and passing to Waisake Masirewa who had no one between him and the try line. New Zealand would go on to win the final 19-17 in controversial circumstances when Fiji were not given the opportunity to restart after scoring a late try.

“That’s my favourite try that I never scored,” Cullen says.

Cullen debuted for the All Blacks later that year, bringing those attacking instincts he nurtured in sevens to the 15s game. He had made his first-class debut for HorowhenuaKapiti against a touring Transvaal side two years earlier, before shifting north to Manawatu for three years, the final one as part of the short-lived Central Vikings concept, before settling in Wellington from 1998.

As freakish as Cullen was, he was helped by having great attacking players like Jonah Lomu, Tana Umaga and Wilson around him, the first two at Wellington and the Hurricanes, and all three at the All Blacks. The help was reciprocal. On one memorable night in New Plymouth in 2000, the Hurricanes thrashed the Reds 43-25 despite seeing little of the ball. Cullen assisted Umaga to a hat-trick and scored himself, while Lomu also crossed for a try.

Few can forget, also, the ‘Game of the Century’ against the Wallabies in Sydney later that year, when the All Blacks raced to a 21-0 lead with Umaga scoring after two minutes, Pita Alatini from the following kickoff and Cullen in the fifth minute. Lomu scored the match winner on full time after a remarkable Wallabies comeback.

As an attacking back three, Cullen, Umaga and Lomu were beyond formidable. Add in Wilson, as John Hart did when he shifted Cullen to centre at the 1999 World Cup, and you had four of the best attacking players of their generation in the same backline.

Cullen had played a lot of age-grade rugby at centre, but those four never quite gelled in the way the public expected them to and the coaches hoped. In fact, Cullen’s positional shift is often blamed for the All Blacks semifinal loss to France. It’s a ridiculous assertion as a lot went wrong for the All Blacks that day, especially up front, but it was ironic that a year later it would be Umaga shifting from wing to centre, immediately establishing himself as a world-class midfielder.

A bad knee injury in 2000 saw Cullen lose a shade of his exceptional pace, but it was still a shock when he was sensationally dropped by John Mitchell for the end-of-year tour in 2001.

The dropping left a bad taste in Cullen’s mouth because he claimed that he had already been left out on medical grounds. The fullback was never notified that he was being “dropped”, with Mitchell, who had just taken over from Wayne Smith, saying he didn’t owe Cullen a call because he had never picked him in the past. In his book, Life on the Run, Cullen made his antipathy for Mitchell and his assistant Robbie Deans clear, saying the latter made his love for his Canterbury boys very clear and that Mitchell was a “bit of a dick”.

Though the 2001 dropping was poorly handled and a PR nightmare, it didn’t take the gloss off Cullen’s reputation — if anything, it enhanced it with the New Zealand public.

Mitchell made a u-turn in 2002 when he picked Cullen for six tests, but the 20-20 draw against France in Paris that November was Cullen’s last test.

Grant Nisbett had witnessed Cullen’s transcendent career from start to finish from Sky’s commentary box. The veteran caller is in no doubt about the quality of what he saw.

“Christian Cullen is the greatest rugby player I have ever seen,” Nisbett says. “I have never seen another player with the ability to change the course of a match so often in one game. He could do everything.”

FA’ALOGO TANA UMAGA WAS THE ALL BLACKS FIRST PASIFIKA TEST CAPTAIN WHO ALSO SUCCESSFULLY MOVED FROM WING TO BECOME A WORLD CLASS CENTRE.

Tana Umaga wasn’t the first Pacific Islander to captain the All Blacks. That honour fell to Joe Stanley, born in Auckland of Samoan heritage, who led New Zealand against a French XV at La Rochelle, in 1990, and against Mar del Plata in Argentina a year later. Auckland-born Frank Bunce, who is Niuean and played for Western Samoa at the 1991 World Cup, captained the All Blacks against Italy A at Catania in 1995.

But Umaga, who was born in Lower Hutt to Samoan parents, was the first to lead the All Blacks in a test, and he did it 21 times from June 12, 2004, in a win against England, through to his international retirement against Scotland in late November 2005, a 29-10 victory that sealed New Zealand’s second Grand Slam.

Umaga opened the door for more to follow. Rodney So’oialo captained the All Blacks in five tests; Jerry Collins, Mils Muliaina and Keven Mealamu in three, while Ardie Savea has worn the skipper’s armband in nine tests at the time of writing.

“Coming from Samoan heritage, it was a very proud moment for us,” Mealamu says of Umaga’s elevation to the test captaincy.

Born 27 May 1973 in Lower Hutt, New Zealand

All Black 961 All Blacks Test Debut Saturday, 14 June 1997 v Fiji at Albany aged 24 years, 18 days Test Caps 74 Test positions Wing, centre and second-five High School Parkway College Club Petone

Under his captaincy the All Blacks won 18 of 21 tests, including a clean sweep in the three-test Lions series and the Grand Slam — beating all four Home Unions in a single tour — in 2005. Umaga also led the adoption of a new haka, Kapa o Pango, that reflected the Pasifika heritage within the team.

For those of us who reported on the game, Umaga was an interesting choice as captain for Sir Graham Henry. He could be stubborn and had a prickly relationship with the media. He imposed several bans on the Dominion newspaper for various slights and refused to talk to TV3 after the network aired footage of him stumbling drunk, through Christchurch’s Cathedral Square, after a post-match celebration. Intensely private, Umaga felt the use of the footage was a gross invasion of his personal life.

His attitude toward the media had to change when Henry offered him the captaincy as he realised it was a role that required him to be front-facing and a conduit between the players and the public. But it was not a case of

forgiving or forgetting and once he walked away from playing, he slammed the door shut again on those he didn’t like.

Whether he liked it or not (and rest assured, he almost certainly didn’t), Umaga was a magnet for a headline as a player and captain.

On one famous occasion he could be heard telling Australian referee Peter Marshall “we’re not playing tiddlywinks” after what he felt was an unfair penalty for a high tackle while playing for the Hurricanes. He also courted controversy when he and Mealamu were accused of a spear tackle on Brian O’Driscoll early in the first test of the 2005 British and Irish Lions tour — a tackle that ruled the Ireland superstar out of the rest of the doomed tour.