LANDSCAPES OF HUMOR PARAJES DEL HUMOR

SELECCIÓN, INTRODUCCIÓN Y NOTAS / SELECTION, INTRODUCTION, AND NOTES BY EDGARDO MACHUCA TORRES, SANTIAGO VAQUERA-VÁSQUEZ, INMACULADA LARA-BONILLA

HOSTOS REVIEW REVISTA HOSTOSIANA

AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND CULTURE

REVISTA INTERNACIONAL DE LITERATURA Y CULTURA

LANDSCAPES

OF HUMOR PARAJES DEL HUMOR

CO-EDITORS / CO-EDITORES/A:

HOSTOS REVIEW / REVISTA HOSTOSIANA

Chief Editor / Editora en Jefe

Inmaculada Lara-Bonilla

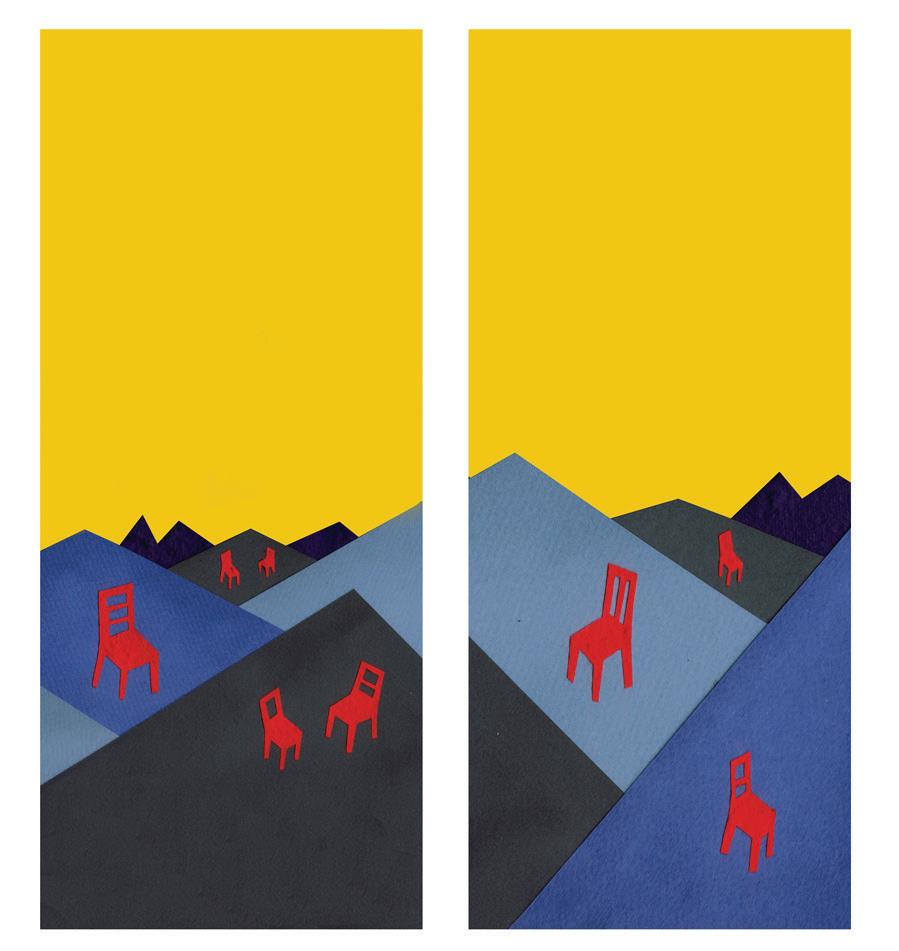

No. 21 Cover Image / Imagen de portada

©Rosaura Rodríguez / Días Cómics

Layout Design / Diagramación Benchmark Signaats Printing Company

Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana es una publicación internacional dedicada a la literatura y la cultura. Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana is an international journal devoted to literature and culture.

La revista no comparte necesariamente la opinión de sus colaboradoras/es. Articles represent the opinions of the contributors, not necessarily those of the journal.

Mailing Address / Dirección postal:

Instituto de Escritores Latinoamericanos

Latin American Writers Institute

Hostos Community College, CUNY

Office of Academic Affairs

500 Grand Concourse Bronx, New York 10451 U.S.A.

HOSTOS REVIEW / REVISTA HOSTOSIANA

Esta publicación es posible gracias al apoyo de / This publication is made possible with support from:

Daisy Cocco De Filippis President

Hostos Community College, CUNY

Andrea Fabrizio

Provost & Vice President of Academic Affairs

Hostos Community College, CUNY

Esther Rodríguez-Chardavoyne Vice President of Administration and Finance

Hostos Community College, CUNY

Humberto Ballesteros Chair, Humanities Department

Hostos Community College, CUNY

Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana would like to thank the Office of the President and Office of Academic Affairs at Hostos Community College, CUNY, for their support in the publication of this issue.

ISSN: 1547-4577

Copyright © 2025 by Latin American Writers Institute Todos los derechos reservados / All Rights Reserved

CONSEJO EDITORIAL HONORARIO/ HONORARY EDITORIAL BOARD

MARJORIE AGOSÍN (Wellesley College)

CARMEN BOULLOSA (City College, The City University of New York)

MARIO BELLATIN (Author, Mexico/Peru)

MARÍA JOSÉ BRUÑA BRAGADO (Universidad de Salamanca)

NORMA E. CANTÚ (Trinity University)

CARLOTA CAULFIELD (Northeastern University)

RAQUEL CHANG-RODRÍGUEZ (City College, The City University of New York)

JACKIE CUEVAS (University of Texas, Austin)

ARIEL DORFMAN (Duke University)

ALICIA GASPAR DE ALBA (University of California, Los Angeles)

MARGO GLANTZ (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México)

ISAAC GOLDEMBERG (Author, Founder, Latin American Writers Institute and Hostos Review/ Revista Hostosiana, Hostos Community College, The City University of New York)

ÓSCAR HAHN (Academia Chilena de la Lengua, Fundación Huidobro)

STEPHEN HART (University College London)

YLCE IRIZARRY (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

GISELA KOZAK ROVERO (Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico & Universidad Central de Venezuela)

ELENA MACHADO-SÁEZ (Bucknell University)

LOUISE M. MIRRER (New York Historical Society)

FRANCES NEGRÓN MUNTANER (Columbia University)

JULIO ORTEGA (Brown University)

EDMUNDO PAZ SOLDÁN (Cornell University)

EMMA PÉREZ (The University of Arizona)

CRISTINA RIVERA GARZA (University of Houston)

GIOVANNA RIVERO (Author, Bolivia - U.S.)

ALEJANDRO SÁNCHEZ AIZCORBE (Southwest Minnesota State University)

RÓGER SANTIVÁÑEZ (Temple University)

MAYRA SANTOS FEBRES (University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras)

JACOBO SEFAMÍ (University of California, Irvine)

MARÍA ANTONIA OLIVER ROTGER (Universitat Pompeu Fabra)

SAÚL SOSNOWSKI (University of Maryland)

ANTHONY STANTON (El Colegio de México)

ILÁN STAVANS (Amherst College)

SILVIO TORRES-SAILLANT (Syracuse University)

VÍCTOR TOLEDO (Universidad Autónoma de Puebla)

SANTIAGO VAQUERA-VÁSQUEZ (New Mexico State University)

SHEREZADA (CHIQUI) VICIOSO (Author, Dominican Republic)

HELENA MARÍA VIRAMONTES (Cornell University)

ÍNDICE / TABLE OF CONTENTS

Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro

Me parió mi abuela, la de la chancleta voladora 132 I Was Birthed by my Grandmother, She of t he Flying Flip-Flop 135

Angelina Sáenz

Elidio La Torre Lagares Informe secreto remitido al consejo superior de ganimedes, por Q-kito 145 Secret Report Sumbitted to The Ganyemede High Council, By Q-Kito 152

Carlos Manuel Rivera ¡Vengo, María, dito! Texto para performance o bululú 159

Susana Chávez-Silverman Toy Story/The Gang’s All Here

NOTA EDITORIAL

Hace más de un año, durante una reunión del consejo asesor del Instituto de Escritores Latinoamericanos (LAWI), una colega propuso dedicar un número de Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana a la literatura humorística latina de Estados Unidos. El comentario resonó, no solo debido al auge de esta vertiente literaria en el país, sino también a la asombrosa escasez de antologías o números especiales dedicados a ella. Esta escasez se convirtió en catalizador del nuevo número, cuya llama se propagó para incluir la escritura del Caribe hispano, una región siempre presente en la ciudad de Nueva York y en otras tantas ciudades del país. El resultado es la vibrante, impredecible, y necesaria compilación que ahora tienen en sus manos, así como nuestro renovado compromiso con el estudio y la celebración del humor en nuestro campo y en nuestro tiempo.

La década de 2010 suele considerarse una “época dorada” de la sátira en la literatura cómica estadounidense1, un modo ciertamente apropiado en el cambiante panorama político y cultural de los años prepandémicos, y muy apropiado también ahora. Sin embargo, como evidencian las páginas de este número, la escritura latina de Estados Unidos, de sus zonas fronterizas y del Caribe despliega hoy modos de comicidad e ironía de una amplitud y un variedad fascinantes. Esta obra se nutre de fuentes compartidas (ironía angloamericana, irreverencia, absurdismo performativo…), pero también hereda otras tradiciones: crónicas fantasiosas e hiperbólicas, escepticismo anticolonial, testimonios ficcionalizados, autobiografía simulada, farsa política, lo carnavalesco, la bufonería, performances paródicas, narrativas anacrónicas, intraducibles juegos lingüísticos bilingües, etc. Este humor y sus variantes, a menudo tejido en español, inglés, spanglish o en una sintaxis propia, se nutre pues de siglos de subversión literaria. Lo que emerge es un cuerpo de escritura que nos obliga a repensar las formas y los límites de la cultura, del idioma, el idealismo, la noción de pertenencia… La rica complejidad de tal paisaje exige no solo atención, sino celebración, y ciertamente mucho más que este número bilingüe (y translingüe) de Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana.

Aun así, nuestro volumen reúne una fascinante constelación de textos. Compilado por dos excepcionales editores invitados y

1 Caron, James E. “Introduction to the Special Issue.” Studies in American Humor, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2019.

autores —Edgardo Machuca Torres y Santiago Vaquera-Vásquez— y, en una rara excepción, también por esta editora general, el número es necesariamente inconcluso, inevitablemente provocador y, sobre todo, una invitación. Está concebido como un racimo bilingüe (incluida la introducción), un conjunto caleidoscópico, un tapiz viviente. Los textos se presentan deliberadamente abiertos, con sus hilos entrelazados suspendidos y en movimiento, listos para ser retomados, extendidos, desenredados y rehechos en futuras obras. Confiamos en que este entramado permitirá a lxs lectorxs conectar con los matices cambiantes del humor latino y caribeño, que disfrutarán de momentos de aguda perspicacia cómica, de felices encuentros con códigos inesperados, de la complicidad del pensamiento crítico compartido, de la emoción de reconocerese en algo colectivo y, si no de la risa (ese santo grial del humor), al menos de una sonrisa que se esboza a pesar de la ferocidad de nuestros tiempos.

Si el humor es un terreno particularmente controvertido en nuestra época, quizá se deba precisamente a su excepcional poder no solo de iluminar y escrutar la realidad histórica, sino también —y sobre todo— de generar diálogo, de influir, e incluso de infundir una sensación de esperanza. El humor no solo genera nuevas formas de narrar, sino que también ofrece refugios y nuevos caminos. Une a lectorxs o público en torno al desconcierto, la desobediencia, la ironía, o el desencanto. Esperamos que encuentren alguno de estos tipos de cobijo en estos textos.

Mi profunda gratitud a quienes hicieron posible esta publicación en el señalado año de 2025, y especialmente a las autoras, autores, e ilustradoras que contribuyen a este cónclave literario. Gracias por invitarnos a recorrer los sinuosos parajes de su imaginación e ingenio.

Cordialmente,

Inmaculada Lara-Bonilla, PhD

Editora en Jefe, Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana Directora, Latin American Writers Institute Hostos Community College, CUNY Nueva York, NY

EDITORIAL NOTE

Over a year ago, during a meeting of the Latin American Writers Institute’s advisory board, a colleague proposed that we devote an issue of Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana to U.S. Latinx/e comedic literature. The comment struck a chord. Not only did we notice that this writing was in ascendance, but also the shocking dearth of anthologies or special issues devoted to it. Such absence became a call—a catalyst, the flame extending to include the writing of the Hispanic Caribbean region, always present in New York and so many other cities throughout the country. The result is the vibrant, unpredictable, and necessary compilation you now hold in your hands—as well as our own renewed commitment to the study and celebration of humor in our field and in our time.

The 2010s are often referred to as a “golden age” of satire in U.S. comedic literature2—a mode well-suited to the shifting political and cultural landscape of the pre-pandemic years, as well as nowadays. Yet, as this issue demonstrates, Latinx/e writers across the United States, its borderlands, and the Caribbean are now crafting comedic literatures of an astonishing breadth and range. Their work taps shared wells—Anglo-American irony, irreverence, performative absurdism…—but it also inherits other traditions: mock autobiography, anticolonial skepticism, parodic performance, political farce, imaginative and hyperbolic crónicas, carnivals, buffoonery, anachronistic narratives, and untranslatable multilingual language games, among other sources. Their humor, often woven in Spanish, English, Spanglish, or a syntax of their own, draws thus from centuries of literary subversion. What emerges is a body of writing that compels us to rethink the shape and limits of culture, language, idealism, or belonging... The complexity of such landscape demands not only attention, but celebration—and certainly much more than this bilingual (and translingual) issue of Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana.

Still, our volume brings together a remarkable constellation of texts. Compiled by two exceptional guest editors and authors— Edgardo Machuca Torres and Santiago Vaquera-Vásquez— alongside this chief editor (in a rare appearance), the issue is necessarily inconclusive, inevitably provocative, and most of all,

2 Caron, James E. “Introduction to the Special Issue.” Studies in American Humor, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2019.

an invitation. It is conceived as a bilingual racimo (including the introduction): a cluster, a kaleidoscope, a living tapestry. The texts remain deliberately open-ended, their interwoven threads suspended and in motion, ready to be picked up, extended, unraveled, and respun in works to come. We trust that this method will allow readers to connect with the ever-evolving hues of Latinx and Caribbean humor, that you will enjoy moments of sharp comedic insight, encounters with unexpected codes and signals, the complicity of shared critical thought, the thrill of collective recognition, and if not humor’s holy grail of laughter, at least a smile a that arrives while facing the ferocity of our times.

If humor is a particularly contested terrain these days, it may be precisely because it holds the rare power not only to illuminate and scrutinize, but also to generate dialogue, persuade, and even to instill a sense of hope. Humor not only sparks new forms of chronicling but can also offer a refuge and new paths forward. It draws readers and audiences together around bewilderment, insight, irony, disenchantment... We hope that you will find such havens in these pages.

With deep gratitude to those who made this publication possible in the significant year of 2025, and especially to the contributing authors and illustrators who joined this literary conclave: thank you. Thank you for inviting us to traverse the sinuous landscapes of your wit and imagination.

Sincerely,

Inmaculada Lara-Bonilla, PhD Chief Editor, Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana Director, Latin American Writers Institute

Hostos Community College, CUNY New York, NY

INTRODUCCIÓN/

INTRODUCTION

Inmaculada Lara-Bonilla Edgardo Machuca Torres

Santiago Vaquera-Vásquez

INTRODUCTION

:O: Somewhere in Zoomlandia

ESTABLISHING SHOT.

Three colleagues—editors X, Y, and Z—log into Zoomlandia from different corners of the globe. The agenda: the journal issue on Latinx humor they are co-editing. Z proposes opening the introduction with a joke. Without hesitation, they launch into one—a long, winding barroom narrative halfremembered from years ago about a man having to choose to spend eternity in either Heaven or Hell. X and Y wait for the punchline. And wait. The silence lengthens as Z, knowing that the joke is too long but refusing to pull the ripcord, trudges on toward the punchline. Finally, the joke sputters to an end. Nothing. Two blank screens, two blank stares. A pause. In Zoomlandia, Z thinks, as in outer space, no one can hear you scream. The colleagues shift uneasily.

Y finally breaks the silence: Me gusta el ascensor. The elevator was not even the point of the joke.

FADE OUT. END OF SCENE.

Opening with a failed joke may seem an odd way to introduce an issue dedicated to Latinx and Caribbean humor, but failure itself can be generative. A bad joke teaches us something—about timing, about context, about the fragile contract between teller and audience. Failure, after all, can be puzzling and knowledge producing. A failed joke can also underscore one of the central problems of a project like this: what counts as funny? what counts as funny across diverse cultural and political worlds? Humor is mercurial, culturally specific, and unruly. It may not even be able to keep up with the incongruous, outlandish nature of our current reality. So, why even attempt a special issue gathering literary humor?

Moreover, to catalog Latinx/e and Caribbean humor is less like assembling a neat taxonomy and more like wrestling with a puzzle whose pieces won’t quite fit, yet may still create surprising pictures when brought together. And that is precisely the challenge—and joy—of this issue of Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana. Humor resists being pinned down, but

when placed side by side, these varied texts create sparks, resonances, and contradictions that illuminate more than any single frame could. Editing such an assemblage a seis manos was at once rewarding and maddening— something like telling a joke across time zones in Zoomlandia.

{} Ensamblaje

No simple task indeed was to think in a comedic key and attempt to anthologize humor as it is used today by U.S. Latinx/e and Caribbean writers. To refine the scope of the project, we decided to focus on writings produced within, or closely related to, the United States, where the journal is published. Within this frame, we envisioned a collection that would compile some of our most contemporaneous literature, in which humor might permeate writing, a literature where perhaps a sense of hopeful witticism could be the dominant tone for a historical moment in which a hopeless perplexity abounds. We asked ourselves: how is this moment being perceived and understood in Latinx/e and border literature in the United States; how in the nearby Caribbean and its diaspora; what attitudes and positions result in comedic genres; what humorous tools are used in times of crisis, division, or polarization? Historically, parody, satire, farce, burlesque, slapstick, pastiche, comedia costumbrista, absurdist narratives, and other forms of literary humor have functioned as a safety valve, as mirrors, as vehicles for analysis, or as sources of pleasure and lightheartedness.

The possible kinds of texts were innumerable; we did not expect any particular genre, and authors could use any number and forms of comedic resources. One-liner zingers or long-winded narrative jokes; dichos and juegos de lenguaje; satire, parody, slapstick, texts full of puns, wry observations, dark humor, dry humor, tragicomedy—the list trailed off because the possibilities were endless. We hoped to capture some of this rich contemporary repertoire and contribute to what was a pending assignment in our field. We were familiar with anthologies of Latinx literature from the 1990s, and some compilations of the work of well-known comedians.1 Others wonderfully compiled the comic as a genre2 (which is not always humorous). There were also important edited collections of academic essays on humor in Latinx literature and an attractive book of conversations between two prominent Latino scholars and writers on Latin American and Western European humor in literature, philosophy, and popular culture.3 We also found volumes dedicated to specific cultural landscapes, such as Puerto

1 The Latino Kings of Comedy and The Latino Queens of Comedy (both published by Uproar Entertainment, 2001) are audiobooks gathering the best known Latinx stand-up comediennes and comedians in the U.S. to date.

2 See, for instance, Tales from la Vida: A Latinx Comics Anthology (edited by Frederick Luis Aldama; Ohio State University, 2018), the YA collection Mañana: Latinx Comics From The 25th Century (Power and Magic Press, 2022), or From Cocinas to Lucha Libre Ringsides: A Latinx Comics Anthology (edited by Frederick Luis Aldama and Ángela M. Sánchez; Ohio University Press, 2025).

3 Aldama, Frederick Luis and Ilan Stavans. Laughing Matters: Conversations on Humor. SDSU Press, 2016.

Rico4 or the border and Chicanx literature/culture of the US Southwest.5 But we were lacking a compilation of literary writings using humor as a key resource in the broader U.S. Latinx/e and Caribbean context. So, we set out to create such a collection in English, Spanish, and their combinations. Soon, a lively, unclassifiable set of texts began to form and entered in a conversation of sorts with each other. Writers of diverse languages and from different geographies contributed pieces to an exchange from the border culture of Mexico to New York, California, other regions of the US, Puerto Rico, Cuba, or the Dominican Republic. El resulting número especial became an assemblage, a construction of texts fitting together in unexpected but exciting ways. As curators, rather than corralling the contributions into neat thematic or stylistic cajas (the kind that get labeled, shelved, and forgotten), we chose to present this issue as such assemblage—a reunión, tal vez a piñata, of texts that brush against each other at odd angles, spark improbable connections, and occasionally side-eye or wink at each other. A piece that shouts its humor loud and clear might find itself paired with one that whispers under its breath. The result, esperamos, is less a clash than un flow—a current where sharp contrasts generate sparks, where the whole hums with the syncopation of laughter arriving on different beats. We do not pretend to offer a master plan or a single punchline. Instead, this issue assembles a set of jokes, gestures, ironies, and provocations whose resonance emerges in their juxtaposition. And at a time when we seem to speak different languages when speaking the same, we bring together the two main tongues of the United States, English and Spanish, and their in-betweens, in originals and translations, as exchanges between the centers of culture and politics and what those centers perceive as peripheries. Hopefully, the issue will resonate and inspire new conversations recognizing the artistry and the vast potential of Latinx/e humorous exchanges.

<> Caleidoscopio

The literary map drawn by our experiment will, thus, be assembled by each reader. It can be composed as an awkward puzzle, or as a kaleidoscope of perhaps discordant colors. The issue is certainly not an exhaustive compilation, but rather a brief snapshot of the radically diverse horizon of humorous genres and instruments employed by a group of writers dedicated to cultivating them. Readers may notice how the texts address, in different tones, some of the personal, social, and political ills of our time. Humor here operates as a form of intervention in current debates about our embodied and disembodied lives, about blindness, ingenuity, and deception, or the need to understand and connect, about sexuality, gender, labor, freedom of expression, public figures, political oppression, or about literature itself.

4 See, for instance, Salvador Tió. Amor, humor y literatura. San Juan: Editorial EDP University. 2012.

5 See, for instance, Hernández, Guillermo. Chicano Satire. U of Texas P, 1991.

Some will notice how these conversations, while global, also connect with specific local, regional traditions and settings. All in all, the gesture of bringing together these diverse forms of humor in a single volume not only draws a labyrinthine map of styles and strategies, but also underscores how comedic resources, in their multiplicity, transcend linguistic, cultural, and geopolitical boundaries.

If one were to choose a linear reading of this compendium, one would first encounter two texts by Giannina Braschi, a contemporary maestra of provocative and profoundly ingenious writing who calls for new thinking frameworks and a revolution in aesthetics, politics, and philosophy. The initial pages of her “Palidode,” the first part of her latest published work, Putinoika (2024), summon Antigone, Ismene, Oedipus, and other characters from classical Greek tragedies to converse with Giannina, the author’s alter ego, about debts and the financial, political, cultural, and spiritual implications of capitalist thinking. Gianinna is a poet and thinker who reflects on the abundance of life, while the ancient classical characters, in their new incarnation, rebel against their imposed destinies and proclaim freedom from inherited family crimes and debts. This excerpt and Braschi’s Fray Luis de León Prize acceptance speech—also included here—remind us not only how ancient political ills persist in our time, but also of how, even when burdened by the most irreconcilable contradictions or aberrant legacies, a powerful emancipatory vitality lies in the transformative force of creativity.

Not everything is spirited and inspiring humor, however, in this issue. We observe—not surprisingly—that the gaze can become somber and unsettling before the eyes can foresee a hint of liberation. Sylvia Aguilar Zéleny’s “Maquila” draws on a dark, ironic humor that exposes the everyday absurdities of factory life through a matter-of-fact, almost conversational narration. The humor often comes in a deadpan register, as the narrator recounts harsh labor conditions and strict rules with a casual tone that makes their severity all the more striking. At the same time, the story satirizes the maquila’s structures of control and exploitation by highlighting small, supposedly “generous” perks—like soda machines or surprise holiday baskets—alongside invasive practices such as locker checks and pregnancy tests. This wry comedy unsettles as much as it entertains, turning humor into a form of social critique that underscores the precarity and contradictions of maquila labor. Also crossing from the EEUU to México, Marcos Pico Rentería’s “Los acarreados” [“The Acarreados”] employs humor in a satirical and ironic register, poking fun at both political spectacle and the absurdities of today’s mass travel. The narrator frames his return to Mexico City with comedic exaggeration and layers this with wry observations about mass mobilizations and bureaucratic rituals. The story’s humor lies in its

blend of parody, cultural wordplay, and biting social critique in a portrait where political sheepishness and gastronomic passions coexist.

Inexplicable human incongruities and habits stubbornly embedded in social realities also appear in other texts. Talking and thinking animals emerge to expose human tendencies in absurdist, surrealist allegories and fable-like writing. Ahmel Echevarría’s pig, Robespierre, engages in thoughtful exchanges with a human narrator who attempts to unravel uneasy paradoxes about sexual desire and identity. Through the limitations of language, and in an often-oppressive interior setting, the narrative evokes the exterior of a Cuba that we don’t get to see. In his otherness, the pig—a well-known character in Latin American and Caribbean literature—stands as a powerful figure who, bordering on the grotesque and despite his grunts and clumsiness, is intelligent to the point of manipulation and illumination. Other—more benevolent or jovial—personified animals are protagonists of the quartet titled “Poemas chiquitos para reír” [“Little Poems Just for Laughs”] by Geraldine de Santis. In the form of a fable, her verses swing between funny, musical children’s poetry and restless leaps of the imagination. Here, the human or animal characters make a commotion with humor that seeks to relieve loneliness, weave imaginary worlds, untangle mischief, and play with the sound of words. In these poems, laughter can be loud, provoked by occurrences that do not allow for boredom, but rather may lead to bursts of laughter. As a whole, the brief, scattered bestiary featured in the issue invites us to notice behaviors that make humans resemble birds, mammals, or crawling creatures as our close relatives. Whether through musical fable or surrealist narrative, animals underscore, ironically or grotesquely, our kinship with them, as they expose human qualities that range from the wise to the bestial, from the mischievous to the absurd, including the bouts of doubt and ignorance that are possible in our species.

Our blindness in the face of delusions and simulations is precisely at the core of some other of the compiled texts. The short story “La mujer del pastor” [“The Pastor’s Wife”] by Haydée Zayas Ramos presents us with a satire where the distorted interpretations of a Protestant pastor are the central strategy to take advantage of the naivety of the parishioners. The pastor’s wife criticizes her husband’s actions and his lack of cleverness to act for his own benefit, and seemingly for the benefit of the community, and decides to form a new church. The story thus criticizes the abuse of religious power, a fertile ground for corruption woven with a constant and exaggerated humor. Other religious figures emerge in the issue—not necessarily as protagonists—, inviting us to reflect on our narrow-mindedness, obsessions, or the power of appearances. The thrones of the heads of official religions, such as a rabbi, a pope, or a Buddhist monk, are incisively stripped of their sacred halo in the micro-stories of Isaac Goldemberg, the blog posts of Josefina Báez, or the poetry of Rolando Pérez, for instance. Placed in

contrast to social realities or the quotidian, these characters often come across as trivial or hardly venerable.

Our compendium seems to affirm, moreover, that perhaps there is nothing like looking at everyday life to find an inexhaustible fountain of humorous inspiration. Never without political undertones, the apparent “normality” of the daily offers an endless source of anecdotes and commonplaces in which error, delusion, or incoherence are not difficult to come across. Memory and humor are combined in “Me parió mi abuela, la de la chancleta voladora” [“My Grandmother Gave Birth to Me, She of the Flying Flip-flop”], a chronicle by Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro, an ode to her abuela’s chancla. Sprinkled with nostalgia, the story celebrates grandmothers as great maternal figures, and rethinks the concept of parir, or birthing, in connection to upbringing and the construction of identity stemming from these superpowers. In the story, the clever gaze of the grandmother detects and sends messages from afar, since she knows her granddaughter as if she had “given birth” to her. The author does not romanticize past habits of adults hitting children but recasts the old practice of the flying flip-flop as a symbol of resistance. The matriarch’s corrective strategies are roadmaps of life, tools for bringing us into this world. Her figure means struggle, action, and courage. Also immersed in daily grind “La carrera” [“The Race”] by Sylma González García is a young adult short story that humorously narrates how two high school students face their lack of interest in sports. Both characters must participate in a track and field race as part of their Physical Education class. Even though athletics will not be the route to reach his goal, the clever way in which the story ends may bring the audience into a burst of laughter or pavera, in Puerto Rican Spanish. The story seems to suggest that one should not abandon a task until it’s completed. The shortcomings and desires inherent in day-to-day decision-making also take center stage in “Tierra y aire” [“Earth and Air”] the short story by Awilda Caez, which moves from the lightly ridiculous all the way to the outright absurd. This parody of letter-writing narratives captures the conversation between a desperate boyfriend and a couple’s pop therapist. We are led into the adventures of the lover, his desperation to please his girlfriend, and his lack of communication with his partner. The story will soon reveal how the intolerance of one and the inflexibility of the other frustrate communication, impeding a healthy relationship that may allow for difference.

In a poetic turn and also settled in an urban daily life of failed couples and powerful mothers and grandmothers, we arrive at Angelina Sáenz’s earnest, unaffected poems, published here in Spanish and English, with translations by the author. The solid voices and bodies of Sáenz’s women are filled with life, history, fearlessness, and—whether in first or third person—all speak against prejudice associated with immigration, indigenous experiences, language, gender, or motherhood. Lastly, the science fiction parody “Informe Secreto remitido al Consejo Superior de

Ganímides, por Q-Kito” [“A Secret Report Submitted to the Ganímides, by Q-Kito”] by Elidio Lagares, imagines an extraterrestrial immersion in daily life in Puerto Rico. The linguistic feast that threads the story is filled with an inventory of idiomatic expressions that bring humor to the text while exploring identity and the social and political struggles that the islanders experience. The extraterrestrial character reports to its galactic superior about its social experiences, its assimilation into colloquial expressions, as it tastes the traditional food of the locals while delighting itself with the essence of local cultural festivities. Humor here serves to highlight the vicissitudes of a country that laughs at itself so as not to cry.

Also quotidian is our use of language, a “normal” part of daily life, except when we pause, as we must in Lagares’s piece, to consider the profound strangeness and arbitrariness of our codes. In several other texts of our compilation, the capriciousness of language appears as a centrifugal point of comic and critical intervention, inextricably linked to its public and its literary dimensions. A playful use of words and sounds in English, Spanish, or Spanglish unfolds like changing outfits of an ingenious content in ironic, refined texts aimed at disrupting what we assume to be a language, literary speech, or even culture. Freed from both the expectations of monolingualism and the literary impositions of genres, performance-oriented writings such as those by Josefina Báez, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Urayoán Noel, or Susana Chávez-Silverman immerse us in the world of translingualism as a path to explore humor and aesthetic realities that disintegrate the attachments and expectations of monolingual readers.

Josefina Báez presents the “bucle interminable” of her Levente no. Yolayorkdominicanyork alongside blog posts published by its protagonist, la Kay, whose voice fills the digital stage to document everyday life in her New York City building. At the beginning of the text, la Kay presents herself as a literary force in an urban, vulgar register, with a colloquial Dominican-york rhythm and translingual sassy humor. The blog entries that follow allow her to continue commenting on present local and global issues—her building part of, and an allegory of, the entire world. Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s “Selected Poems” also deploy humor performatively and translingually, in this case through parody and absurd exaggeration, blending pop culture, politics, and performance art. His poems often use irreverence and satire, mixing English, Spanish, and Spanglish to destabilize authority and poke fun at cultural anxieties. The humor is at once playful and biting, transforming pandemic worries, border politics, and technology into ironic, surreal comedy. Urayoán Noel, for his part, transports us through a sonic, playful code to an orality in which technology meets a critical contemplation of diaspora and of poetic practice itself through a “language of sargassum.” The metaliterary text overflows with insights on the overwhelming sociocultural and economic energies of colonial expansion, but also on the resilience and constant struggle for survival of the Puerto Rican people. As

a continuum of resilience, and in a register replete with orality and destined for performance, we find “Vengo, María, dito!” by Carlos Manuel Rivera. In this performance poem, we delve not so much into linguistic play between Spanish and English, but into the dialectal slang of a voice that at all costs attempts to make sense of his dystopian migrant experience in New York. Interestingly, knowing the stage practice of these authors, we imagine all of these mixed-genre and mixed-language writings being performed before an audience that can connect to the topics not only through humor but also through language, be it Chicanx, Espinglés, Dominicanish, or Spanglish.

Finally, and with a definitive vocation for lively and public dialogue, we find excerpts from plays written by two well-established Chicano playwrights. Herbert Sigüenza’s Bad Hombres/Good Wives uses humor through parody and farce, blending Shakespeare, Molière, and telenovela melodrama. The play thrives on exaggerated characters, slapstick, and witty dialogue, poking fun at machismo, narco-culture, and toxic masculinity. Its humor is both playful and satirical, using laughter as a tool to critique power, gender roles, and cultural stereotypes. On the other hand, Carlos Morton’s On the Border a Mysterious Stranger Arrives uses humor as biting political satire, parodying both classical drama and contemporary politics. The play exaggerates real-world figures into absurd caricatures whose antics mock authoritarianism and global power struggles. Through farce, parody songs, and outrageous dialogue, the text deploys comedy to critique border policies, imperial ambition, and the spectacle of politics itself.

The issue closes with the incisive translingual “Toy Story/The Gang’s All Here Crónica,” by Susana Chávez-Silverman. Both personal and political, the chronicle flows like a torrent of contemporary references woven into a brash and daring Spanglish. The speaker searches family archives for the humor that may allow us to write about our political moment and concludes with a eulogy to the virtues of erotic love and its profoundly healing properties in a forward-looking present. Such is the closing of this special issue, which may perhaps also be read as a chronicle, as a momentary and collective narrative that recounts how some authors like Chávez-Silverman are thinking, writing, and experiencing our turbulent times through the prism of humor in a Latinx/e, a Caribbean, a borderlands, or a diasporic key.

~ Coda

The collection of texts that we have gathered thus displays a range of comedic topics and registers, from sober and deadpan irony to the most savage political satire and over-the-top theatrical farce. Stories that narrate everyday life with mordacity and exaggeration, highlighting the absurdities of work, politics, and intimacy, coexist here with texts that use performance and Spanglish as tools of parody, destabilizing the “serious” aspect of official

culture. At the same time, this volume opens space for voices that experiment with playfulness in a childlike way—wordplay, laughter, boundless imagination—or that recover intimate memory and Caribbean popular culture with a critical, nostalgic, and irreverent twist. There are also satires that denounce the cunning of religious power, absurd epistolary pieces about love and communication, and youthful stories that transform an “attack of the giggles” into creative resistance. Together, these stories, poems, and plays trace a vibrant map of contemporary Latinx/e and Caribbean literature, where humor becomes a survival strategy, social critique, collective memory, and above all, a bridge of complicity and wink-wink with the reader.

At the same time, we resist the tidy seduction of declaring once and for all what humor “does.” Is it resistance, a loud laugh at the emperor’s lack of clothes? Is it a funhouse mirror, revealing how society already looks absurd before we even start laughing? Is it decolonial praxis, undoing colonial logics with a joke, a pun, or a perfectly timed eye-roll? Is it a survival tactic, a way to breathe when history tries to suffocate or controlarnos? Yes. And also— maybe tal vez, sometimes, not only, or not at all. Humor, after all, refuses to sit politely in theory’s waiting room. Es resongón. It heckles. It says “yes, but, y además.” It multiplies, contradicts, interrupts. It thrives on excess. Bakhtin tells us laughter is centrifugal; Anzaldúa reminds us it thrives in nepantla, the in-between; de Certeau would call it tactical, a small but sly maneuver. We might just call it slippery—every time we think we’ve got the joke, the joke has already moved on, like Barthes punctum. A joke can pierce us, but sometimes not in its punchline. Me gusta lo del ascensor, for example. So rather than offer a final word, this issue offers a kaleidoscope: turn it once, you see parody; turn it again, irony; turn it again, a subterranean murmur that only surfaces later, maybe while you’re cooking dinner. What holds the issue together is not uniformity but assemblage: a shared recognition that humor matters, that it unsettles, reframes, resonates—and, if we’re lucky, makes us laugh out loud in the process. Like the best jokes, the effect is cumulative, disruptive, and just a little bit unruly. The punchline? We’re still waiting for it. Or maybe we’ve already missed it.

Inmaculada Lara-Bonilla is an essayist, poet, and Professor of Latin American, Caribbean, and Latinx/e Studies at Hostos College, CUNY, where she directs the Latin American Writers Institute (LAWI) and serves as chief editor of its multilingual literary journal, Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana. Her research on Latin American and Latinx Literature and Cultural Studies has been published internationally, focusing on feminist theory and the contributions of Latina and Latin American literary authors to transnational philosophical thought. As a poet, she is the author of the collection decir bóveda (2022), translated into English and Arabic, and the unpublished Aullido/Howl. Her bilingual poetry has been included in anthologies and international journals, such as Stone Canoe, Literal Magazine, Home Planet News, Zenda Libros, or Journal of the Southwest. Lara-Bonilla is recognized for her multifaceted contributions to research, poetry, editorship, and cultural leadership.

Edgardo Machuca Torres is a college professor. He obtained his Master’s and Doctorate degrees at the Center for Advanced Studies of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean. In 2005, his short story “The Trace of his Guilty Foot” won second place in the Literary contest held at NUC University. Some of his poems are part of the anthology La magia de la palabra escrita (2007) published by the Center for Advanced Studies of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean. In 2009, he published the book, Cuando un hombre merece la vida: la obra de Aníbal Nieves y EDP College. Machuca has also published literary research works in the academic journals Academia, Exégesis, and Identidad. He has served as a judge for the International Pen Novel Contest and the City of Carolina Short Story Contest. He is currently an Associate Professor at EDP University.

Santiago Vaquera-Vásquez is an unrepentant border crosser, ex-dj, Xicano writer, painter, and academic. A Professor of Creative Writing and Hispanic Southwest Literatures and Cultures at the University of New Mexico, he has also taught and lectured at universities across the United States, Latin America, and Europe. He has also held Fulbright Fellowships in Spain, and Turkey, and served as a Fulbright Specialist in Poland. His books include, Algún día te cuento las cosas que he visto (2012), Luego el silencio (2014), One Day I’ll Tell You the Things I’ve Seen (2015), and En el Lost y Found (2016). His most recent works are a photographic chapbook of photos and stories from his travels in Turkey, Yabancı [Foreigner] Extranjero (2019), and the novel Nocturno de frontera (2020). Widely published in Spanish, his literary work has appeared in anthologies and literary journals in Spain, Italy, Latin America and the United States. Commenting on his writing, Junot Díaz has said “Santiago Vaquera is literary lightning. He impresses, he illuminates, and when he is at his best you are left shaken, in awe.”

Inmaculada Lara-Bonilla Edgardo Machuca Torres

Santiago Vaquera-Vásquez

INTRODUCCIÓN

:O: En algún lugar de Zoomland

PLANO GENERAL.

Tres colegas —editores X, Y y Z— se conectan a Zoomlandia desde distintos rincones del planeta. The agenda: el número especial sobre humor latinx y caribeño que están co-editando. Z propone abrir la introducción con un chiste. Sin pensarlo dos veces, arranca con uno—largo, enredado, a barroom tale medio olvidado de hace años, sobre un hombre obligado a escoger dónde pasar la eternidad: en el Cielo o en el Infierno. X e Y esperan el punchline. And wait. El silencio se extiende mientras Z, fully aware de que el chiste ya se estiró demasiado, pero rehusándose a jalar del paracaídas, sigue avanzando hacia el final. Finalmente, el chiste se desploma en un aterrizaje forzoso. Nada. Dos pantallas en blanco, dos caras sin expresión. Pausa. En Zoomlandia, piensa Z, como en outer space, no one can hear you scream. Los colegas se mueven incómodos. Y, por fin, rompe el silencio: Me gusta el ascensor. El ascensor ni siquiera era el point del chiste.

FADE OUT. FIN DE LA ESCENA.

Empezar con un chiste fallido puede sonar raro como opening para un número dedicado al humor latine, pero el fracaso también produce. A bad joke nos enseña algo—about timing, sobre contexto, sobre el contrato frágil entre quien cuenta y quien escucha. El fracaso, al fin y al cabo, puede ser desconcertante y, sin embargo, generador de conocimiento. Un chiste que no funciona también subraya una de las preguntas centrales de un proyecto como este: ¿qué cuenta como funny?; ¿qué cuenta como funny across mundos culturales y políticos distintos? El humor es mercurial, cultural-specific, indomable. Quizá ni siquiera alcance a seguirle el paso a lo incongruente, lo outlandish, de nuestra realidad presente. Entonces, ¿por qué insistir en armar un número especial de humor literario latina/o/x y caribeño?

Catalogar el humor latino y caribeño no es como armar una taxonomía neat and tidy, sino como pelear con un rompecabezas cuyas piezas nunca encajan del todo, aunque, al forzarlas, a veces revelen imágenes inesperadas.

Y ese es precisely el reto—y el joy—de este número de Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana. El humor se resiste a que lo clasifiquen, pero cuando se ponen estos textos lado a lado, saltan chispas, resonancias y contradicciones que iluminan más de lo que podría cualquier marco solitario. Editar un assemblage así, a seis manos, fue rewarding y maddening a la vez—algo así como intentar contar un chiste across time zones en Zoomlandia.

{} Assemblage

Nada simple sin duda fue el acto de pensar en clave de humor para componer el número, de intentar antologar el humor como es empleado hoy día por escritores y escritoras latinxs y caribeñxs. Para delimitar la empresa, decidimos centrarnos en escrituras producidas dentro de, o en relación cercana con, el Estados Unidos de nuestros días. Dentro de este marco, visionamos un conjunto que compilara algo de la literatura más contemporánea (años 2024 y 2025 sobre todo) en la que el humor empapa la escritura, una compilación en la que quizá una agudeza esperanzada pudiera ser el tono dominante para un momento histórico de aturdimiento e incluso desesperanza. Nos preguntamos: ¿cómo se está percibiendo y pensando este momento y su clima social en la literatura latina y fronteriza de Estados Unidos, en el nearby Caribe, y en su diáspora? ¿Cuáles son las actitudes, las posiciones que permiten lo cómico hoy día? ¿Cúales las herramientas humorísticas a las que recurrir en momentos de crisis, división, o polarización? There must be some, pues históricamente, la parodia la sátira, farsa, lo burlesco, lo bufonesco, el pastiche, la comedia costumbrista, las narraciones absurdistas y otros los modos literarios del humor han funcionado como válvula de escape, or as a mirror, or as vehículo de crítica y análisis, o fuente de placer o ligereza. Los tipos de textos posibles eran innumerables, no adscritos a ningún género en particular y podrían utilizar múltiples recursos. Remates fulminantes o chistes narrativos larguísimos; dichos y juegos de lenguaje; sátira, parodia, humor físico, textos repletos de juegos de palabras, observaciones mordaces, humor negro, humor seco, tragicomedia—la lista se desvanece porque las posibilidades son infinitas. Confiamos en poder captar algo de este rico trabajo, e invitamos a escritoras y escritores a componer con nosotres lo que era asignatura pendiente en nuestro campo. Conocíamos antologías de literatura Latinx de EEUU desde los años 1990, también algunas que recogían el trabajo de mujeres y hombres humoristas bien conocides aquí.1 Había aún otras que han compilaban maravillosamente el género del cómic2 (por supuesto, no siempre humorístico) y un atractivo libro de conversaciones entre prominent Latino scholars y escritores sobre el humor en la literatura,

1 The Latino Kings of Comedy and The Latino Queens of Comedy (Uproar Entertainment, 2001) son audiobooks que compilan trabajo de les humoristas Latinx de EEUU más conocidos hasta el momento de su publicación.

2 See, for instance, Tales from la Vida: A Latinx Comics Anthology (edited by Frederick Luis Aldama; Ohio State University, 2018), the YA collection Mañana: Latinx Comics From The 25th Century (Power and Magic Press, 2022), or From Cocinas to Lucha Libre Ringsides: A Latinx Comics Anthology (edited by Frederick Luis Aldama and Ángela M. Sánchez; Ohio University Press, 2025).

filosofía y cultura popular de Latinoamérica y Europa Occidental.3 Existían también importantes colecciones de ensayos académicos sobre el humor en la literatura latinx4 y algunos dedicados paisajes geo-culturales específicos como el de Puerto Rico5 o el de la literatura/cultura fronteriza y chicana del suroeste de EEUU.6 Sin embargo, una compilación de escrituras que, en el contexto latino de Estados Unidos mostrara el humor como recurso central nos estaba faltando. Y nos propusimos confeccionarla en inglés y/o en español e incluir una latinidad que se extendiera en el Caribe y los espacios limítrofes, vecinos y fronterizos de este país.

And so, una viva y difícilmente catalogable producción literaria entró a nuestras pantallas y entró en conversación. Escritoras/es que escriben en diversas lenguas y desde diferentes geografías dialogaban desde la cultura fronteriza con México, hasta Nueva York y otras regiones de EEUU, pasando por Puerto Rico, Cuba o la República Dominicana en un fascinante intercambio. El número especial resultante es, así, un assemblage, un puzzle de textos que encajan entre sí de maneras quizá inesperadas pero siempre estimulantes. En vez de encajonar las contribuciones en temáticas o estilos ordenaditos (esas cajas que se etiquetan, se archivan y se olvidan), hemos preferido presentar este número como tal ensamblaje— una reunión, tal vez una piñata, de textos que se rozan en ángulos extraños, que encienden conexiones improbables y que, de vez en cuando, se miran de reojo o se lanzan un guiño. Una pieza que grita su humor en voz alta y clara puede encontrarse junto a otra que apenas susurra entre dientes. El resultado, esperamos, es menos un choque que un flow—una corriente en la que los contrastes agudos generan chispas, donde el conjunto entero vibra con la síncopa de una risa que llega a destiempo, en diferentes beats. No pretendemos ofrecer un plan maestro ni un punchline único. Más bien, este número reúne un conjunto de chistes, gestos, ironías y provocaciones cuya resonancia surge de su yuxtaposición. Y en un tiempo en el que parece que hablamos distintos idiomas al hablar el mismo, juntamos aquí las dos lenguas principales de Estados Unidos, inglés y español, y sus in-betweens, originales y traducciones, intercambios entre los centros de cultura y política y lo que esos centros perciben como periferias. Ojalá el número también contribuya a desarrollar nuevas compilaciones que reconozcan el arte y el alcance de brillantes encuentros humorísticos.

<> Caleidoscope

El mapa literario que dibuja nuestro experimento será ensamblado, pues, por cada lector/a. Podrá leerse como un rompecabezas incómodo o como

3 Aldama, Frederick Luis and Ilan Stavans. Laughing Matters: Conversations on Humor. SDSU Press, 2016.

4 Latino Humor in Comparative Perspective (available via Oxford Bibliographies) o Latinas and Latinos on TV: Colorblind Comedy in the Post-racial Network Era (by Isabel Molina-Guzmán), entre otros.

5 Véase, por ejemplo, Tió, Salvador. Amor, humor y literatura. Editorial EDP University, 2012.

6 Véase, por ejemplo, Hernández, Guillermo. Chicano Satire. U of Texas P, 1991.

un caleidoscópico de colores quizá discordantes. Definitivamente, no como una compilación exhaustiva, pero sí quizá como radiografía breve del radicalmente diverso horizonte de los géneros e instrumentos humorísticos empleados por un grupo de escritoras y escritores dedicades a cultivarlos. Se verá que abordan, desde muy distintos tonos y con muy diversos recursos, algunos de los males personales, sociales y políticos de nuestro tiempo. El humor aquí opera como forma de intervención en los debates actuales sobre nuestras vidas encarnadas e incorpóreas, sobre la ceguera y el engaño, la necesidad de entender y conectar, la sexualidad, el mundo laboral, la libertad de expresión o la misma literatura, entre otros temas. Y estas conversaciones globales entroncan con tradiciones locales, regionales y transnacionales específicas. El gesto de reunir estas escrituras del humor en 2025 en un mismo espacio puede no solo haber trazado un laberíntico mapa de estilos y estrategias, sino también subrayado cómo los recursos cómicos, en su multiplicidad, constituyen prácticas que desbordan fronteras lingüísticas, culturales, ideológicas, o geopolíticas.

Si se elige una línea de lectura lineal, se encuentran en primer lugar dos textos de Giannina Braschi, maestra contemporánea del pensamiento y la estética literaria, de propuestas provocadoras, revolucionarias e ingeniosas que nos llaman a la transformación política de nuestro tiempo. Las primeras páginas de su “Palidode”, primera parte de su última obra, Putinoika (2024), convocan a Antígona, Ismene, Edipo y otros personajes de la tragedia clásica griega para conversar con Giannina, alter ego de la autora. Su discusión gira en torno al tema del endeudamiento y las implicaciones financieras, políticas, culturales y espirituales del pensamiento capitalista. Gianinna, poeta y pensadora, reflexiona sobre la abundancia de la vida mientras los antiguos personajes clásicos se rebelan, en su nueva encarnación, contra el destino impuesto, proclamando su liberación de deudas y de crímenes familiares heredados. Este fragmento de Putinoika, así como el discurso de Braschi que incluimos, nos recuerda cómo incluso con las contradicciones aparentemente más irreconciliables y los más aberrantes legados podemos encontrar una vitalidad emancipadora en la potencia transformadora de la creación.

Pero no todo es humor esperanzado en este número. Observamos, sin que resulte sorprendente, que la mirada a veces se torna sombría e inquietante antes de prever cualquier punto de fuga o liberación posible. “Maquila” de Sylvia Aguilar Zéleny se nutre de un humor oscuro e irónico que expone los sinsentidos cotidianos de la vida en la fábrica mediante una narración directa, casi conversacional. El humor aparece con frecuencia en un registro seco, cuando la narradora relata las duras condiciones laborales y las estrictas reglas con un tono casual que hace resaltar aún más su severidad. Al mismo tiempo, el relato satiriza las estructuras de control y explotación de la maquila al poner en primer plano pequeños beneficios

supuestamente ‘generosos’—como las máquinas de refrescos o las canastas sorpresas en días festivos—junto a prácticas invasivas como las revisiones de casilleros y las pruebas de embarazo. Esta comedia mordaz inquieta tanto como entretiene, convirtiendo el humor en una forma de crítica social que subraya la precariedad y las contradicciones del trabajo en la maquila.

También cruzando de Estados Unidos a México, “Los acarreados” de Marcos Pico Rentería emplea el humor en un registro satírico e irónico, burlándose tanto del espectáculo político como de las absurdidades de los viajes contemporáneos. El narrador enmarca su regreso a la Ciudad de México en una exageración cómica y lo adereza con observaciones mordaces sobre movilizaciones masivas y rituales burocráticos. El humor del relato reside en su mezcla de parodia, juegos culturales de lenguaje y crítica social punzante en un retrato donde coexisten la sumisión política y las pasiones gastronómicas.

Encontramos también otros textos en los que las incongruencias de ciertos hábitos sociales aparecen obcecadamente instaladas en la realidad. Entre el absurdo, la alegoría surrealista y la fábula, emergen animales parlantes y pensantes que a veces conversan con humanos. El cerdo Robespierre de Ahmel Echevarría entra en sesudos intercambios con un narrador que intenta desentrañar paradojas incómodas sobre el deseo a través de las limitaciones del lenguaje y en un sórdido y represivo ambiente interior que deja entrever la Cuba del exterior. La otredad del chancho, personaje bien conocido de la literatura latinoamericana y caribeña, representa una potente figura que, rozando lo grotesco y a pesar de su torpeza y gruñidos, es inteligente hasta el punto de la manipulación. Otros animales personificados, más benévolos o joviales, son los protagonistas del cuarteto titulado “Poemas chiquitos para reír” de Geraldine de Santis. En clave de fábula, sus versos se columpian entre una poesía infantil divertida, musical y los saltos inquietos en la imaginación. Aquí los personajes humanos o animales alborotan con un humor que aspira a despejar la soledad, a hilar mundos imaginarios, a desenredar travesuras y jugar con la sonoridad de las palabras. En estos poemas las risas pueden ser en voz alta, provocadas por las ocurrencias particulares que no permiten bostezos de aburrimiento, sino carcajadas de diversión. En su conjunto, la animalia que hace aparición en este número nos invita a reparar en comportamientos que nos asemejan a las aves, a mamíferos o a seres reptantes como parientes cercanos. Ya sea a través de la fabulación musical, ya en una suerte de surrealismo onírico, estas criaturas subrayan, irónica o grotescamente, nuestro parentesco con ellas, así como cualidades humanas que van de lo sabio a lo bestial, de lo pícaro a lo absurdo o a la ignorancia posible en nuestra especie. Precisamente nuestra ceguera ante ciertos fingimientos y simulaciones, sobre todo en el plano religioso, es protagonista en varios otros textos recogidos. El cuento “La mujer del pastor” de Haydée Zayas Ramos nos presenta una sátira donde las interpretaciones dislocadas de un pastor

protestante son la estrategia central para aprovecharse de la ingenuidad de los feligreses. La esposa del pastor critica las ocurrencias de su marido y le expresa su falta de astucia para actuar en beneficio propio que parezca en beneficio de la colectividad. No obstante, la mujer despoja al hombre de todos los bienes y reformula una nueva iglesia. Así, el relato, hilvanado con un humor constante y exagerado, critica las astucias del poder religioso donde la corrupción puede encontrar terreno fértil. Aunque no necesariamente como protagonistas, varias otras figuras religiosas exponen fenómenos relacionados con cerrazones, obsesiones, o el poder de las apariencias. Figuras entronizadas por las religiones oficiales como un rabino, un papa, o un monje budista, son incisivamente desarmados y desprovistos de su halo sacro en los microrrelatos de Isaac Goldemberg, en las entradas de blog de Josefina Báez, o la poética de Rolando Pérez, por ejemplo. En contraste con su realidad social y lo cotidiano, estas figuras llegan a resultar ridículas o al menos difícilmente venerables.

Y es que nuestro compendio también parece afirmar que quizá no hay nada como posar la la mirada sobre la vida cotidiana para encontrar una fuente inagotable de inspiración humorística. Nunca exenta de fondo político, la aparente “normalidad” de lo diario ofrece un sinfín de anécdotas y lugares comunes en los que el error, lo delirante, o lo incoherente son fácilmente detectables. La memoria y el humor se conjugan así en la crónica “Me parió mi abuela, la de la chancleta voladora” de Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro, una oda a la chancleta de su progenitora. Este texto salpicado de nostalgia celebra a la abuela como referente materno y replantea el concepto de parir desde la crianza y la construcción de la identidad a partir de ciertos superpoderes. La autora no romantiza los chancletazos, los clasifica como un símbolo de resistencia. Las estrategias correctivas de la matriarca son mapas de vida, herramientas para parirnos al mundo. Además, presenta la mirada astuta de la abuela que detecta y envía mensajes a la distancia como señal de que conoce a su nieta-hija como si la hubiese “parido”. Su presencia representa lucha, acción, valor.

Abundando en lo cotidiano, “La carrera” de Sylma González García es una breve narración juvenil donde el humor es una herramienta para manejar la falta de afición por los deportes por parte de dos estudiantes de escuela superior. Las dos amigas deben participar de una carrera como parte de su clase de Educación Física. Sin embargo, el atletismo no será la ruta para llegar a su meta. En el lenguaje puertorriqueño el ingenioso final del cuento provoca en el lector “una pavera”, pero destaca que el comienzo de una tarea no se abandona hasta su culminación. Las deficiencias y deseos implícitos en los hábitos diarios son también protagonistas en el cuento “Tierra y aire” de Awilda Caez, con un humor que tiende al absurdo. Esta parodia epistolar narra los diálogos entre un novio desesperado y una consejera en relaciones de pareja. La autora nos sumerge en las peripecias del enamorado, su desesperación por agradar a su novia y su falta comunicativa

con su pareja. La autora devela cómo la intolerancia de uno y la inflexibilidad de la otra frustran los procesos de la comunicación para establecer relaciones saludables y destacan un amplio espacio para las diferencias. En un giro hacia la poesía, y también instalada en una cotidianidad urbana de parejas fallidas y abuelas y madres poderosas, aparecen los poemas honestos y sin afección de Angelina Sáenz, que publicamos en español e inglés traducidos por la autora. Las voces y los cuerpos de sus mujeres están llenos de vida, historia y coraje, y ya en primera o en tercera persona, desafían patrones y prejuicios asociados a la inmigración, la experiencia indígena, la lengua, el género o la maternidad. Elidio La Torre Lagares por su parte, en un texto de ciencia ficción titulado “Informe Secreto remitido al Consejo Superior de Ganímides, por Q-Kito”, parodia la cotidianidad boricua. El banquete lingüístico que hila la historia está aderezado por un inventario de puertorriqueñismos que le brindan humor a la narración, explora el sentido de identidad y comenta las luchas sociopolíticas que experimenta el puertorriqueño. El personaje extraterrestre presenta un informe a su superior galáctico acerca de las vivencias sociales, mientras no solo se asimila a los modismos coloquiales, sino que también degusta parte de la tradición gastronómica y enamora su paladar con la esencia de la festividad cultural. El humor funciona para señalar las peripecias de un país que se ríe de sí mismo por no llorar.

Cotidiano es también nuestro uso de la lengua, excepto cuando nos detenemos a reparar, como lo hacemos en la pieza de La Torre Lagares, en la profunda extrañeza y la arbitrariedad de nuestros códigos. En otros textos del número la lengua también aparece como punto centrífugo de intervención cómica e inextricablemente unida a su dimensión pública y literaria. Un uso lúdico de las palabras y sus sonidos en inglés, español o spanglish se despliega como atuendo que recubre ingeniosos contenidos en varios textos irónicos, finos, y orientados a desordenar lo que asumimos como lengua, como lenguaje literario, e incluso como cultura. Liberados tanto de las expectativas del monolingüismo como de las imposiciones literarias de los géneros, escritos como los de Josefina Báez, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Urayoán Noel, o Susana Chávez-Silverman nos adentran en las estancias del translingüismo como vía poderosa para explorar el humor y realidades estéticas que desintegran nuestros apegos y expectativas como lectorxs monolingües. Báez enlaza el “bucle interminable” que dice ser su Levente no. Yolayorkdominicanyork con el blog que publica su protagonista, la Kay, dejando primar la voz de este personaje en su dominicanish para documentar lo cotidiano. En el inicio de este texto para performance la Kay se nos presenta soberana del espacio literario en un registro urbano, vulgar, con ritmo coloquial dominicanyork, con humor translingüe y pícaro. Las entradas de su blog que siguen le permiten continuar relatando, comentando cuestiones locales y globales del presente, siendo su edificio a la vez parte y alegoría del mundo. “Selected Poems” de Guillermo Gómez-Peña también despliega el

humor a través de la parodia y la exageración absurda, mezclando cultura pop, política y arte performático. Sus poemas recurren con frecuencia a la irreverencia y la sátira, combinando inglés, español y spanglish para desestabilizar la autoridad y burlarse de las ansiedades culturales. El humor es a la vez lúdico y mordaz, transformando las ansiedades de la pandemia, la política fronteriza y la tecnología en una comedia irónica y surrealista. Urayoán Noel, por su parte, nos traslada a través de un nuevo código poético y lúdico, a una oralidad en la que technology meets contemplación crítica de la diáspora y de la práctica poética en sí en un “lenguaje de sargazo.” El texto metaliterario se entrecruza a su vez con observaciones de fenómenos socioculturales propios de las energías arrolladoras del colonialismo, pero también con la resiliencia y la constante lucha por la supervivencia del pueblo boricua. Como un continuum de adaptibilidad y también con un lenguaje repleto de oralidad y destinado a la performance, encontramos “¡Vengo, María, dito!” de Carlos Manuel Rivera. En este caso no nos adentramos en un juego lingüístico entre el español y el inglés, sino en un baño de jerga dialectal muy puertorriqueña que a toda costa intenta hacer sentido de una distópica experiencia neoyorquina. Interestingly, y conociendo la práctica escénica de sus autores/as, estos escritos los proyectamos inevitablemente como textos performáticos, orales, con la posibilidad de ser leídos ante un público que puede conectar a través del humor en chicanx, espinglés, dominicanish, o spanglish.

Finalmente, y con definitiva vocación de diálogo vivo y público, se encuentran extractos de dos obras de teatro de veteranos dramaturgos chicanos. “Bad Hombres/Good Wives” de Herbert Sigüenza utiliza el humor a través de la parodia y la farsa, mezclando a Shakespeare, Molière y el melodrama de la telenovela. La obra se sostiene en personajes exagerados, humor físico (slapstick) y diálogos ingeniosos, burlándose del machismo, la narco-cultura y la masculinidad tóxica. Su humor es a la vez lúdico y satírico, utilizando la risa como herramienta para criticar el poder, los roles de género y los estereotipos culturales. Por otro lado, “On the Border: A Mysterious Stranger Arrives” de Carlos Morton recurre al humor como sátira política mordaz, parodiando tanto el drama clásico como la política contemporánea. La obra exagera figuras del mundo real hasta convertirlas en caricaturas absurdas cuyas acciones ridiculizan el autoritarismo y las luchas de poder globales. A través de la farsa, las canciones paródicas y diálogos desmesurados, el texto despliega la comedia para criticar las políticas fronterizas, la ambición imperial y el espectáculo mismo de la política. El número se cierra con una incisiva, arrojada y translingüe crónica de Susana Chávez-Silverman. En clave tanto personal como política, “Toy Story/The Gang ‘s All Here Crónica” fluye como un torrente de referencias trenzadas en un deslengüado y atrevido bilingüismo. El texto busca en los archivos familiares el humor que permita escribir sobre nuestro tiempo y concluye con una alabanza a las bondades del amor erótico y a

sus propiedades profundamente sanadoras para el momento presente. Y así, este special issue quizá puede entenderse como un archivo momentáneo, como una suerte de crónica colectiva que cuenta cómo se está pensando, escribiendo, y experimentando a través del prisma del humor y en clave latinx norteamericana y caribeña en nuestros días.

~ Coda

El conjunto de textos en esta antología despliega, pues, un abanico de registros humorísticos que van desde la ironía sobria y deadpan, hasta la sátira política más savage y la farsa teatral over the top. Aquí conviven cuentos que narran la vida cotidiana con mordacidad y exaggeration, poniendo el dedo en los absurdos del trabajo, la política y la intimidad, junto con textos que hacen del performance y del spanglish herramientas de parodia, destabilizing lo “serio” de la cultura oficial. At the same time, este volumen abre espacio para voces que experimentan con lo lúdico en clave infantil —juegos de palabras, carcajadas, imaginación sin fronteras— o que recuperan la memoria íntima y la cultura popular caribeña con un twist crítico, nostálgico e irreverente. También aparecen sátiras que denuncian las astucias del poder religioso, piezas epistolares absurdas sobre el amor y la comunicación, y relatos juveniles que transforman an attack of the giggles en resistencia creativa. Together, estos relatos, poemas y obras teatrales trazan un mapa vibrante de la literatura latina y caribeña contemporánea, donde el humor se convierte en survival strategy, en crítica social y en memoria colectiva, pero sobre todo, en un puente de complicidad y wink-wink con el/la lector/a.

Al mismo tiempo, nos resistimos a la seducción cómoda de declarar de una vez por todas lo que el humor ‘hace’. ¿Es resistencia, una carcajada fuerte ante el rey desnudo? ¿Es un espejo de feria, revelando cómo la sociedad ya luce absurda antes incluso de empezar a reírnos? ¿Es praxis decolonial desarmando lógicas coloniales con un chiste, un juego de palabras o un eyeroll perfectamente cronometrado? ¿Es una táctica de supervivencia, una manera de respirar cuando la historia intenta asfixiarnos o controlarnos? Sí. Y también—maybe, tal vez, a veces, no solo, o quizá para nada. El humor, al fin y al cabo, se niega a sentarse educadito en la sala de espera de la teoría. Es rezongón. Interpela. Dice “sí, pero, y además”. Se multiplica, se contradice, interrumpe. Se alimenta del exceso. Bakhtin nos dice que la risa es centrífuga; Anzaldúa nos recuerda que florece en el nepantla, el in-between; de Certeau la llamaría táctica, un movimiento pequeño pero astuto. Nosotros quizá la llamemos escurridiza—cada vez que creemos atrapar el chiste, el chiste ya se ha movido, como el punctum de Barthes. Un chiste puede traspasarnos, pero no siempre en el punchline. Me gusta lo del ascensor, por ejemplo.

Así que, en lugar de ofrecer la última palabra, este número ofrece un caleidoscopio: lo giras una vez y ves parodia; lo giras de nuevo y ves ironía;

lo giras otra vez y escuchas un murmullo subterráneo que solo emerge más tarde, quizá mientras cocinas la cena. Lo que mantiene unido al número no es la uniformidad, sino el assemblage: un reconocimiento compartido de que el humor importa, que descoloca, replantea, resuena—y que, con suerte, nos hace soltar una carcajada en el proceso. Como los mejores chistes, su efecto es acumulativo, disruptivo y un poquito indisciplinado. ¿El punchline? Todavía lo estamos esperando. O quizá ya se nos pasó.

Inmaculada Lara Bonilla es ensayista, poeta y Catedrática de Estudios Latinoamericanos, Caribeños y Latinx/e en Hostos College, CUNY, donde también dirige el Instituto de Escritores Latinoamericanos y ejerce como editora en jefe de su revista literaria multilingüe, Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana. Su investigación sobre literatura y estudios culturales latinoamericanos y latinx se ha publicado internacionalmente, centrándose en la teoría feminista y las contribuciones de autoras literarias al pensamiento filosófico transnacional. Como poeta, es autora de la colección decir bóveda (2022), traducida al inglés y al árabe, y del libro inédito Aullido/ Howl. Su poesía bilingüe también se ha publicado en antologías y revistas internacionales, como Stone Canoe, Literal Magazine, Enclave, Home Planet News, Zenda Libros o Journal of the Southwest. Lara Bonilla es reconocida por sus contribuciones multifacéticas a la investigación, la poesía, la edición y el liderazgo cultural.

Edgardo Machuca Torres es profesor a nivel universitario. Obtuvo su grado de Maestría y Doctorado en Literatura puertorriqueña y del Caribe, del Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe. En 2005 ganó el segundo lugar de Cuentos del Certamen literario de NUC University, por su cuento “La huella del pie culpable”. Algunos de sus poemas forman parte de la antología La magia de la palabra escrita (2007) publicada por el Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe. En el año 2009 publicó el libro Cuando un hombre merece la vida: la obra de Aníbal Nieves y EDP College. Ha publicado diversos trabajos de investigación literaria en la revista Academia, Exégesis e Identidad. Algunas de sus investigaciones se han presentado en foros, simposios y congresos nacionales. Desde el año 2012 es fundador y director de la Editorial EDP University y editor de la revista Academia. Ha participado como jurado en el certamen de novela del Pen Puerto Rico Internacional y certamen de cuento del Municipio de Carolina. Actualmente es Catedrático Asociado en EDP University.

Santiago Vaquera-Vásquez es impenitente cruzador de fronteras, narrador Xicano, académico y ex dj. Profesor Catedrático en la Universidad de Nuevo México, imparte cursos sobre cultura fronteriza, chicana y talleres de escritura creativa. Ha impartido cursos y conferencias en universidades a través de los Estados Unidos, América Latina y Europa. Ha sido también becario Fulbright en España, Turquía y Polonia. Ha publicado cuentos en antologías y revistas literarias en España, Italia, México y Estados Unidos. Sus libros incluyen Algún día te cuento las cosas que he visto (2012), Luego el silencio (2014), One Day I’ll Tell You the Things I’ve Seen (2015), y En el Lost y Found (2016). Sus publicaciones más recientes son un chapbook de fotos y cuentos de sus viajes por Turquía, Yabancı [Foreigner] Extranjero (2019) y la novela Nocturno de frontera (2020). Comentando su narrativa, Junot Díaz ha dicho: “Santiago Vaquera es un relámpago literario” que “impresiona e ilumina hasta dejar al lector sobrecogido.”

LANDSCAPES OF HUMOR/ PARAJES DEL HUMOR

Giannina Braschi

“PALINODE”1

Excerpt of “Palinode” from the epic tragicomedy PUTINOIKA (2024)

Oedipus: I killed my father.

Agamemnon: I killed my daughter.

Orestes: I killed my mother.

Clytemnestra: I killed my husband.

Jocasta: I hung myself.

Oedipus: I blinded myself.

Cassandra: I recoiled. And when I recoiled Apollo Phoebus said— you will see, but nobody will believe you. But do I need to be believed in order to see? I recoiled. I stopped the coitus. So did Teiresias. He stopped the coitus between two serpents with his staff—and for that he was transformed into a woman for seven years. And then after seven years he saw the same serpents coupling—and he struck with his staff again—and he was transformed back into a man. Although nobody believed Teiresias either after he was blinded by Hera and given the gift of seeing by Zeus. Nobody believed that he was right. Not Creon. Not Oedipus. It’s better not to believe what you’re seeing. But Teiresias never saw his own destiny—nor Manto nor Calchas—none of those seers—with my exception because I am exceptional. I saw my own death—and nobody would believe it—because I spoke in tongues and I was a slave—and a refugee—and a princess—and a gift of war—and I died the moment I recoiled—the

1 [Editor’s Note] We present here the opening pages of Giannina Braschi’s Putinoika (2024), from the first part of the work titled, “Palinode.” We reprint this excerpt with permission from the author and the publisher, Flowersong Press. Its placement as the first text in this issue of Hostos Review / Revista Hostosiana recognizes Braschi’s dexterity in combining political and philosophical humor to discuss the ills of our time, as well as the potential of writing—and rewriting—as a harbinger of social transformation.

moment I saw my death—and nobody would believe that I saw what I saw.

Antigone: So now what are they saying?

Ismene: They say we are lazy.

Antigone: Who calls us lazy?

Ismene: The Germans.

Giannina: And they say I am lazy too.

Antigone: Who calls you lazy?

Giannina: The Americans. They say I don’t like to work. And that’s why I am on welfare, always depending on their radiation, on their generosity of spirit that is so huge especially when it comes to tax deductions. If I were born in Cuba, I would have no debt. They liberated themselves from the system of demolition and debt. They don’t owe anyone anything, not even the Russians who protected them during the Bay of Pigs. If the Russians would have invaded Puerto Rico, the Americans would have charged us for every radiation of a missile that they would have pointed at the Kremlin. Now they don’t need us for that. They come here to play golf and avoid taxes. And when they go bankrupt, they leave us with the debt. The debt of ingratitude for all the golf courses, hotels, and shopping malls they’ve built for themselves.

Antigone: The Germans owe me. I don’t owe them. They owe me Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides. They owe me Aristophanes, Socrates, Aristotle. They took so much culture from us, and we never charged them interest for the inspiration—the divine madness they took from us. I mean, all those Romantics. Ask Goethe. Ask Hölderlin. Ask Schiller. And what about their philosophers. They learned how to think with us. Where were their souls nourished—in whose tradition. Ask Nietzsche. Ask Schopenhauer. Ask Heidegger. They took everything from us. And from our temples, they stole our art. Did we ever charge them interest? No, because we bury our dead—and with them our debts. We nourish talents.

We don’t bury alive what is dead. Even our god, our highest god, Zeus, was so fertile that he gave birth twice. From his head to Athena, and from his thigh to Dionysus. Aren’t we generous? Watch out. Don’t even try to victimize a Greek. We don’t become victims. We become heroines. You bury me alive—and look what I do—I create a tragedy for you. I give you hell.

Ismene: There’s a problem here.

Antigone: What’s the problem here?

Ismene: We don’t share the same gods.

Antigone: I adore Apollo Phoebus, the sun. They worship money.

Giannina: And they say the sun is lazy, and it gives sunspots. And they use sunscreen. And you know why they charge us interest? Because we know how to enjoy. And because we know how to cherish, they put a price tag on our cherishment, on our enjoyment, on our gratitude. They can’t stand to see us happy—if we are happy—it is because we are lazy.

Ismene: But the creditors are knocking on every door. They knock and knock and knock.

Antigone: Open the doors. If you don’t have money, give them flowers. If you don’t have flowers, give them apples, oranges, quenepas.

Giannina: Give them nothing. I owe them nothing. I will pay no debt. It’s not a debt. It’s the cost of running a colony.

Ismene: They say everything has a price tag.

Antigone: Life is precious.

Ismene: Precious is a jewel. That’s why it has a price tag. Nothing is free.

Giannina: Fruit falls in abundance from the tree—in abundance giving—and not taking what it is giving. If you take what you give, it should be the way the sea takes what it gives