Asian-American Abstraction: Historic to Contemporary

Fu Qiumeng Gallery, located at 65 East 80th Street, is presenting a concurrent exhibition, Transcultural Dialogues: The Journey of East Asian Art to the West. Focusing on the exchange between traditional Eastern art and modern American abstraction, the show spans the past few centuries and provides another historical angle through which to understand this interplay.

Asian-American Abstraction: Historic to Contemporary

July 11–September 7, 2024

Essays by Jeffrey Wechsler and Emily Chun

Hollis Taggart

521 West 26th Street

New York, NY 10001

Foreword

Hollis C. Taggart and Debra V. Pesci

8

Historical Art Becomes Modern: From East to West

Jeffrey Wechsler

16

Asian-American Artists Influenced by East Asian Art

52

Notes on Tradition, Newness, and Asian-American Art

Emily Chun

54

American Abstract-Expressionist Artists Influenced by East Asian Art

I have just had my first lesson in Chinese brush from my friend and artist Teng Kwei. The tree is no more solid in the earth, breaking into lesser solids in the earth, breaking into lesser solids bathed in chiaroscuro. There is pressure and release. Each movement, like tracks in the snow, is recorded and often loved for itself. The Great Dragon is breathing sky, thunder and shadow; wisdom and spirit vitalized. All is in motion now . . . One step backward into the past and the tree in front of my studio in Seattle is all rhythm, lifting, springing upward.

— Mark Tobey, 1951

Foreword

This exhibition marks a foray for the gallery into an area of art historical investigation that has long been of interest to us. This extensive exhibition traces several generations of modern and contemporary Asian-American artists, discovering the roots of their inspiration and techniques. There has been a broad, enduring contribution of the Asian diaspora on the development of American art. The core premise of this presentation was originally conceptualized in a ground-breaking show by curator Jeffrey Wechsler who has spearheaded this endeavor as well. Mr. Wechsler’s survey began at the Zimmerli Art Museum in 1997 and traveled to other museum venues in the United States, Japan, and Taiwan. The event gleaned much critical praise including a favorable review from famed New York Times writer Holland Cotter. The show explored ways in which Asian-American artists of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean heritage incorporated distinctive traditional East Asian techniques and philosophies in their art. Expanding upon this complex and multi-layered theme, the current show examines the artists’ responses to nature, palette, and iconic compositional forms. Individual exploration of abstraction of landscape and natural forms, gestural and calligraphic techniques, use of compositional voids and intentional monochromatic fields of color are some of the points of intersection and reveal identifiable connections.

Added to the investigation is a generation of American Postwar artists who have traceable ties to Asian traditions as well. A pantheon of Abstract Expressionists including Robert Motherwell, Theodoros Stamos, Richard Pousette-Dart, Sam Francis, and Franz Kline, among others, are included in this discussion. Propelled by artistic modes of expression and informed by ancient philosophies, these painters assimilated East-Asian traditions both directly and subliminally. They are joined by their Asian-American counterparts working and exhibiting as contemporaries. Our examination of this phenomenon continues with

Asian-American artists working today. These artists renew the past with current interpretations of the evolution and continuation of these innovative ideas.

We are grateful for the opportunity of working with Jeffrey Wechsler whose extensive knowledge and sensitivity to this material is highly impressive. Similarly, art historian Emily Chun has offered a compelling essay on artists working today, bringing this analysis up to the moment. This exhibition, presented on both our floors of the gallery, including forty-five artists is a monumental endeavor on every level. The behemoth project was realized with expert care by the collaborative efforts of our professional staff. Administrative and outreach tasks were handled brilliantly by Antonio Rosales and Severin Delfs, both of whom deserve high praise. Our appreciation is also extended to Kara Spellman for research and catalogue production, and for her overall guidance of this project from its conception. We salute our Logistics Manager, Stan Charnin, for his efforts at overseeing all of the moving parts that a show of this magnitude requires.

The use of the term “Asian American” began in the late 1960s. The phrase has gone through countless transmutations and social connotations over the decades. This show demonstrates that through these shifts, essential key artistic traditions and methodology have endured. Far more than mere adaptations of formal techniques or subject matter, these shared influences show a deep synthesization of Asian traditions and philosophical ideologies in the American art historical vocabulary. We trust you will find this thematic concept as intriguing as we do.

Hollis C. Taggart

Debra V. Pesci

Historical Art Becomes Modern: From East to West

Jeffrey Wechsler

Fig. 1.

Yujian Ruofen (active late 13th century), Chinese, Mountain Market, Clearing Mist, late 13th century. Vertical hanging scroll, ink on paper, 13 × 32 5/8 in. (33.1 × 82.8 cm).

Idemitsu Art Museum, Tokyo, Important Cultural Property

Fig. 2.

Zhu Yunming (1461–1527), Chinese, Flowers of the Seasons (detail), 1519. Handscroll, ink on paper, calligraphy: 17 11/16 × 625 1/8 in. (45 × 1587.9 cm); mount: 18 ¼ in. high (46.3 cm high), Princeton University Art Museum, Bequest of John B. Elliott, Class of 1951

In 1997, a traveling exhibition entitled Asian Traditions/Modern Expressions: Asian American Artists and Abstraction, 1945–1970, organized by the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, presented the achievements of a selected group of Asian-American artists in the context of a broad and vital trend in American art: the increasing importance of abstraction in the mid-twentieth century. Specifically, it demonstrated how Asian-American artists were able to make use of traditional East Asian art techniques and philosophies to develop a creative blending of Eastern and Western art. Drawing upon aspects of the distinctive artistic traditions of their cultural origins—China, Japan, and Korea— they found ideas and techniques that prefigured abstract modes in the West, and applied them in their work during the era of Abstract Expressionism. Indeed, as a group, they represented a true merging of early Asian and modern Western concepts of art and abstraction, and a knowledgeable blending of Asian and Western aesthetics. Thus, the exhibition sought to present three intertwined themes: the recognition of the “abstract” qualities found in much early East Asian art, and their relationship to forms of abstraction (in particular, painterly and gestural abstraction) that were regarded as “advanced” in the United States in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s; the documentation, reconsideration, and appreciation of the work of a neglected generation of Asian American abstractionists; and the description of how the bicultural expressions of these artists comprise a coherent subset of American Abstract Expressionism, with recognizably East Asian elements and attitudes purposefully merged in a successful modern synthesis of East and West.

In 2024, Asian-American Abstraction: Historic to Contemporary, an exhibition at Hollis Taggart, offers an updating of the themes from the 1997 exhibition, revealing that the visual and conceptual goals of the earlier presentation have been honored, maintained, and given further new expressions through several generations of Asian-American artists, right up to the present day. In an

introductory section, several of the artists displayed in the original exhibition — producing works within the years of Abstract Expressionism’s rise and spread— are again present. Differing from the original show, this part of the display intersperses Asian-American abstractionists with a group of recognized American figures of the Abstract Expressionist era whose work demonstrates the often overlooked fact that many non-Asian-American abstractionists were influenced by East Asian art and aesthetics— a situation often vehemently denied by many art critics and writers who wished to promote the notion of a thoroughly unique American art style, sui generis and utterly unaffected by any external influences. The bulk of the new exhibition is devoted to work from the 1970s to the 2020s, with emphasis on the more contemporary examples to confirm that the synthesis of traditional Eastern and modern Western art persists even now in vital artistic modes.

When abstract art began to dominate the Western art scene from the 1940s through the ’60s, many American writers praised American abstract artists as highly innovative, claiming their use of very free methods of abstraction — such as rapid, gestural brushstrokes, dripped pigment, and large areas of monochrome or even blank canvas — as a historical breakthrough. This notion simply overlooked the long, venerable, and quite different artistic tradition of East Asia. In this tradition, precise and detailed description of objects was rarely considered a goal. Instead, revealing the essence of an object or a part of the natural world, and evoking feelings and thoughts from the observer, were more important. In this aesthetic philosophy, art is not imitative of reality, and the physical properties and expressive qualities of the artist’s medium could be appreciated to some measure as independent aesthetic ends. Thus, the fundamental concept of art as essentially a process of abstraction, by definition several degrees removed from reality, is fundamental to East Asian artistic practice, and is arguably East Asian in origin.

Many writers who championed Abstract Expressionism stressed its historical importance in terms of technical and compositional innovation. However, many of the formal and visual attributes they appreciated as advanced in American art had been applied for centuries in East Asian art, including gestural. semi-controlled techniques of paint application; calligraphic methods, emphasizing free linearism; acceptance of accidental effects; asymmetrical compositions; restriction of color range, often to just black and white; prominent voids or empty spaces; and freely applied washes that create stains or fields of color.

So consider the following: the spreading washes and spatters of the i-p’in (untrammeled) and p’o-mo (flung ink) techniques; the lightning-like delivery of pigment in sumi ink painting and the most vigorously brushed manners of calligraphy; the great expanses of untouched white ground that dominate so many East Asian works of art; the insistently flattened effects of many screens and scrolls. In all of these, aspects of modern methodologies are prefigured or paralleled. It is startling to read accounts of certain early Chinese artists at work; the following describes the methods of a painter of the eighth century, over a millennium ago:

When he was ready to paint, he would first lay out numerous pieces of silk on the floor; then he would grind the ink and prepare various colors, and put them into containers . . . he would then run around the silk several dozen times, finally taking the ink and spilling it all over. Next he would sprinkle on the colors. The places where they spilled he would cover with a large cloth; then he would have someone sit on it, while he himself grasped it by one corner and pulled it all around. After he was finished, he would then add the finishing touches with a brush.1

This method may be an extreme one, but in many abbreviated suggestions of landscapes conjured out of the briefest dabs and blottings of ink (fig. 1), and countless outpourings of writhing calligraphy so freely gestural that they nearly forsake legibility (fig. 2), one sees the tendency toward abstraction that underlies much East Asian art.

Scholars of Asian art who have considered East/West interaction in modern art are familiar with the cultural tendency toward abstraction in traditional Eastern art and realize that abstraction as a concept is assuredly there but is used in a different sense than in the West. For instance, as art historian George Rowley has written,

[T]he abstract quality of Chinese design arose from simplification and elimination rather than from mechanization and distortion of form; and suggestion in Chinese painting, although used to heighten the awareness of the unknown, seldom departs from the laws of nature. [Modern Western] artists strain after the new and startling, while Chinese artists built upon the old and the mature.2

The understanding of the differences between Eastern and Western approaches to the concept of abstraction, along with the deliberate insertion of traditional Eastern notions within a modern Western context, created the unique bicultural visions of mid-twentieth century Asian-American artists. Thus, the abstract art of this group of Asian Americans is generally perceptibly distinct from other American abstractions of their time.

Abstraction of form in East Asia flows from an a priori understanding that what one paints is not reality and is not meant to imitate it. Impelled by the creation of moods, the elicitation of emotions, and the striving for a spiritual vitalism of technique, Eastern art is based in a sense on non-artistic principles such as religious and philosophical beliefs. For example, Buddhism teaches not that the mind perceives existing things, but that things are created by the mind — it is concerned with interpreting values rather than describing facts. It has been stated that Buddhism, applied to the field of artistic activity, affords the purest kind of inspiration, and if an artist “possesses the proper means of exteriorization, he will transmit in symbols or shapes something which contains a spark of that eternal stream of life or consciousness”3 —wherein “symbols and shapes” touch upon the process of artistic abstraction. Also, the appreciation of “the void” in Taoism and Buddhism encourages the perception of what many might consider “empty” space to be instead an energized medium, equally as important as solid

matter, and worthy of presence and contemplation in art—what Western compositional aesthetics somewhat dismissively calls “negative space.” This Eastern view of the void is prominent in works by Don Ahn (fig. 3), Hayoon Jay Lee (pl. 15), Tad Miyashita (pl. 17), and Emi Sisk (pl. 23), and is sometimes linked to color field painting, as in works by Kikuo Saito (pl. 22).

As noted above, the Eastern artistic heritage “seldom departs from the laws of nature.” This partially explains why modern artists living in East Asia, with a heritage extraordinarily free in its abstraction of nature, were often resistant to making the step into completely nonobjective art. An imaginative envisioning of reality could be stretched nearly indefinitely but not snapped and released to drift without any connection to it. Consequently, nature imagery has been incorporated in the work of many Asian-American artists. Their refusal to discard all vestiges of nature from their art and their decision to work in the realm of semi-abstraction were contrary to the tenor of the Abstract Expressionist era, when even so prominent a figure as Willem de Kooning could be branded a traitor to Abstract Expressionism for initiating a series of paintings based on images of women. However, to the Eastern mind, nature is the irrefutable, ultimate source of all things, including art. The artist James Suzuki noted that most abstraction by Japanese Americans is a nature abstraction (pl. 26).

When dealing with nature, AsianAmerican artists were free to move beyond the internal technical abstraction of the East into the pictorial abstraction of the West. In effect, nature abstraction for Asian Americans could proceed from the outside in (rendering abstract impressions of nature or its forces) or from the inside out (using one’s latent emotional and spiritual ties to nature to imbue abstraction with natural properties). Allusions to the diverse forms and phenomena of the natural world find expression in the work of Peter Arakawa (pl. 2), SoHyun Bae (pl. 3), Aesther Chang (pl. 4), Arnold Chang (pl. 5), Gabrielle Yi-Wen Mar (pl. 16), Jennifer Jean Okumura (pl. 21), Marlene Tseng Yu (pl. 33), and many others.

Another major manner of expression of Asian-American abstraction incorporates intertwined visual and philosophical elements: calligraphy, gesture, and ch’i. The mysterious agency of ch’i, or spirit, has a crucial role

in East Asian art, once summarized as follows: “If an artist caught ch’i everything else followed, but if he missed ch’i, no amount of likeness, embellishment, skill, or even genius could save the work from lifelessness.”4 Ch’i, as it affected the art of Asian Americans, can perhaps best be visualized through abstraction based on gesture, energized brushwork, and calligraphic motifs. The work of certain New York School Abstract Expressionists was sometimes compared to East Asian linearism and calligraphy — especially the black-andwhite abstractions of Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell. But a fundamental difference was evident to Asian-American artists who had extensive training in traditional brushwork, in which apparent spontaneity results only from the masterful control learned from long experience. New York School gestural abstractions may appear brusque, choppy, and overworked compared to art by Asian Americans intent on capturing the vitalizing quality of ch’i. In contrast, Ahn, an admirer of Zen calligraphy, created paintings with graceful, sweeping, and seemingly effortless gestures. His work often combined the delicacy of traditional brush and ink work with the wide, slashing paint strokes of Abstract Expressionism (pl. 1). Walasse Ting seemed to confront this difference of approach directly; even when a painting is dominated by a bulky black form (as in pl. 27), Ting tipped the shape to appear delicately balanced on a point, and surrounding spatters and voids allow the composition to occupy its space lightly.

Asian-American abstractionists were logically attracted to gestural and calligraphic methods because calligraphy is itself an art form in East Asia, ranked on an aesthetic level as equal to or higher than painting. Traditional East Asian writing is pictographic in its sources, developed through successive stages of simplification; thus, Eastern artists are fully aware that these written characters are inherently a system of abstraction. The mastery of brush gesture associated with fine calligraphy and the freedom of the most radical examples of calligraphy (fig. 2) were a cultural basis for Asian Americans to use calligraphy, or the rapid calligraphic gesture, for expressive abstraction in the Western sense. Among the artists in the current exhibition who employ this mode of expression to varying degrees are Oonju Chun (pl. 11), Nishiki SugawaraBeda (pl. 24), Wang Ming (fig. 4), Ivy Wu (pl. 31), and Taro Yamamoto (pl. 32).

An imaginative use of calligraphy imbued with several levels of meaning can be found in Chuang Che’s Love (fig. 5), in which the form of the Chinese character for “love” is altered, deleting parts of its component strokes. A compound character, it includes the independent symbol for “heart” set near its center. Reversing the historical procedure of pictographic abstraction, the artist replaced the character for heart with a rendering of an actual human heart. But to indicate that he is working between Eastern and Western notions of abstraction, he abstracted the heart in the Western sense, reducing it to an organic orangish object in a red ring. This clever hybrid painting is a double inversion of cultural content because it combines Eastern abstraction of ideographic writing and Western concepts of abstraction as simplification

and nonobjectivity. More recently, some artists integrate actual characters, or distortions of characters, into their work, such as Yuming Sun (pl. 25), and Steve Wada (pl. 28). The calligraphic gesture has even been transformed into three dimensions, as in sculptures by Gwen Yen Chiu (pl. 9).

A further example of Asian-American abstractionists transferring traditional modes into modern expressions can be seen in the context of field painting and “stain” painting, which was held to be a stylistic advance of the utmost significance within Abstract Expressionism. The influential art critic Clement Greenberg posited that the inherent aesthetic qualities of painting were those that grew directly out of the material and nature of painting itself; he lauded Color Field painting, and in

particular its refinement in “stained” painting, in which the pigment soaks into the canvas surface, integrating color and surface. However, East Asian art, with its emphasis on water-based pigments and ink, has essentially been creating stain painting for centuries, even millennia. The colors applied onto silk or paper of such art fully suffuse into the surface, with color and support becoming one. Indeed, the waywardness of highly liquid media—spreading and puddling or dispersing in waves or runnels—encouraged the acceptance of accidental effects as a parallel to the randomness, effulgence, and essentially uncontrollable spirit of nature appreciated by Eastern artists. Therefore, landscapes are often begun by washing liquid media over a surface to produce abstract color areas—essentially stained field paintings—before the

6.

details of nature suggested by the abstraction are added. Images created by the semi-controlled flow of pigmented media, varying from transparently thin to more substantial textures, can be seen in work by Yuho Chang (pl. 6), Chinyee (fig. 6), Hisao Hanafusa (pl. 13), Emi Sisk (pl. 23), Kelly Wang (pl. 29), and Marlene Tseng Yu (pl. 33).

Asian-American artists were, of course, quite aware of the various aspects of traditional East Asian art which foreshadowed modernist Western methods, because they generally had personal knowledge and practical experience with them. They easily adapted their

cultural traditions to the burgeoning flow of abstraction around them to create their modern, fully abstract compositions. It is heartening that a few non-Asian Abstract Expressionists freely admitted their Eastern influence, such as Motherwell, Mark Tobey, Richard Pousette-Dart, Sam Francis, and Sal Sirugo (fig. 7).

In effect, the East and West historically approached abstraction from two complementary, but opposite, philosophies. In the East, the breakthrough of abstract art was at first simply ignored, not as non-art, but as irrelevant to—or insignificant within—the great continuity

of Eastern art whose ideas of abstraction were based in spirit or inner meaning. The East had all the technical and philosophical inclinations toward abstraction for centuries but did not move into nonobjectivity because it simply saw no need to do so. The more individualistic and literal-minded Western aesthetic viewed abstraction more as a pictorial achievement. In sum, the East stood at an artistic boundary with its proto-abstract tradition for a long, long time and said, “Why?” The West, catching up all in a rush with a new-found gesturalism and abstraction, finally reached the same brink and said, “Why not?”

The earlier generation of Asian American artists represented in this exhibition created their work in a certain place and at a particular moment in history that was particularly opportune for a new artistic interpenetration of East and West. Later artists continued in their footsteps, appreciating both tradition and modernity, and devising individual variations, expanding and enriching the synthesis. It is fascinating that a phenomenon so vast in its implications—the meeting of two of the major cultural entities on this planet—can be manifested in a single artist’s vision. Many artists have revealed, often through personal anecdotes marked both by directness and touching humility, their dedication to their chosen path, as in these words by Noriko Yamamoto, an artist included in the 1997 exhibition: “My background comes from my intense calligraphy training since childhood (six years old). My tremendous respect is for the old Zen masters. Because of my Japanese and Western background, I am trying to integrate both cultures . . . to synthesize the greatness of both.”5

Notes

1. S. Shimada, “Concerning the I’pin Style of Painting,” Part 1, trans. J. Cahill, Oriental Art 7, no. 2 (1961): 69, quoted with slight author emendations in: Charles Lachman, “‘The Image Made by Chance’ in China and the West: Ink Wang Meets Jackson Pollock’s Mother,” The Art Bulletin 74, no. 3 (1992): 499.

2. George Rowley, Principles of Chinese Painting, rev. ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974), preface.

3. Osvald Siren, “Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism and Its Relation to Art,” The Theosophical Path (October 1934), quoted in Christmas Humphries, Buddhism: An Introduction and Guide, 3rd ed. (Harmondworth: Penguin Books, 1985), 208.

4. Rowley, 34.

5. Noriko Yamamoto, statement in Young America 1960 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1960), 118.

Jeffrey Wechsler held the position of Senior Curator at the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University until retiring in 2013. Specializing in lesser-known aspects of twentieth-century American art, he has organized over fifty exhibitions in that field, including Surrealism and American Art, 1931–1947 (1977), Realism and Realities: The Other Side of American Painting, 1940–1960 (1982), Abstract Expressionism: Other Dimensions (1989), and Transcultural New Jersey: Crosscurrents in the Mainstream (2004), as well as the original 1997 exhibition on which Asian-American Abstraction: Historic to Contemporary is based.

plate 1

plate 2

Peter Arakawa (b. 1956)

5.25.02, 11:56 AM, 2002

Gouache and acrylic on rice paper

73 × 39 1/2 in. (185.4 × 100.3 cm)

plate 3

SoHyun Bae (b. 1967)

Untitled, 2023

Rice paper and pure pigment on canvas

72 × 24 in. (182.9 × 61 cm)

Oil and mixed media on canvas

16 × 20 in. (40.6 × 50.8 cm)

Corona Landscape 2020.01, 2020

Ink on paper

28 3/4 × 18 3/8 in. (73 × 46.7 cm)

courtesy Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, New York

plate 7

Chao, Chung-hsiang (1918–1991)

Flowing Moon, n.d.

Chinese ink and acrylic on paper

29 1/8 × 28 1/2 in. (74 × 72.5 cm)

courtesy of Alisan Fine Arts, New York

Ink

No. 2, 2023

Welded aluminum

40 × 36 × 36 in. (101.6 × 91.4 × 91.4 cm)

plate 13

Hisao Hanafusa (b. 1937)

Uchuiden Kioku (Cosmic Inherent Memory) – QM2, 2003

Aluminum paint on canvas

36 × 48 1/2 in. (91.4 × 123.2 cm) courtesy of Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, New York

plate 14

plate 15

the Universe, 2022

plate 17

Tad Miyashita (1922–1979)

Untitled, circa 1950s

Mixed media on paper

22 1/2 × 30 in. (57.1 × 76.2 cm)

plate 18

Untitled, circa 1960

40 × 50 in. (101.6 × 127 cm)

plate 19

Untitled, circa 1970

Oil and collage on canvas

39 1/2 × 31 1/2 in. (100.3 × 80 cm)

plate 20

Through Smoke and Ruin the Sun Still Shines, 1958

54 × 46 in. (137.2 × 116.8 cm)

plate 22

Kikuo Saito (1939–2016)

Ashes Ruby, 1982

Acrylic on canvas

92 × 47 in. (233.7 × 119.4 cm)

courtesy of the Kikuo Saito Estate and James Fuentes

plate 23

Emi Sisk (b. 1976)

Blue Tranquility, 2023

Watercolor on paper

12 × 9 in. (30.5 × 22.9 cm)

plate 24

KuroKuroShiro The S, 2023

Sumi on wood

40 × 30 in. (101.6 × 76.2 cm)

A Thousand Miles of East Wind, 2020 Ink and color on rice paper

Walasse Ting (1929–2010)

Windmill, 1959

32 × 42 1/2 in. (81.3 × 108 cm)

13 1/2 × 9 3/4 in. (34.3 × 24.8 cm)

plate 30

Wang, Ming (1921–2016)

Book, 1996

Acrylic and ink on paper 20 panels each measuring 20 × 16 in.

(50.8 × 40.64 cm), mounted on paperboard in accordion style book Private collection

plate 31

Ivy Wu (b. 1981)

I’m Sleepy When Awake but Don’t Wake Me Up 1, 2023

Acrylic on canvas

24 × 20 in. (61 × 50.8 cm)

I’m Sleepy When Awake but Don’t Wake Me Up 2, 2023

Acrylic on canvas

24 × 20 in. (61 × 50.8 cm)

Untitled, 1971

Oil and sand on canvas

40 1/4 × 50 in. (102.2 × 127 cm)

Notes on Tradition, Newness, and Asian-American Art

Emily Chun

Asian-American Abstraction: Historic to Contemporary features contemporary Asian-American artists who draw upon aspects of traditional East Asian artistic techniques and philosophies, incorporating them into their practices on their own terms. Works as varied as SoHyun Bae’s watery veils of blue pigment, Oonju Chun’s gestural bundles, Gwen Yen Chiu’s aluminum serpentine sculpture, and Hayoon Jay Lee’s rice reliefs, among many others, emerge from this broad premise.

The incorporation of tradition into one’s practice, however, is never as straightforward as the concept might imply. Tradition does not come to us as facticity but through side shadows and back alleys. Like the invisible causation of wind — in which we see the wind only through its effects on other objects— artistic conventions are not static readymades that pass down and become retranslated in a clear, linear chain of causation. In his 1976 essay “Convention and Innovation,” Clement Greenberg observed how the relationship between tradition and innovation necessarily speaks in riddles and puzzles: “The conventions of art, of any art, are not immutable, of course. They get born and they die; they fade and then change out of all recognition; they get turned inside out. . . . A tradition of art keeps itself alive by more or less constant innovation.”1

What complicates the relationship between tradition and innovation in the specific context of contemporary Asian-American art is, of course, the ever-present risk of its collapsing into essentialized, intrinsic, knowable ideas of “Asianness,” which Susette Min describes as “visual characteristics or indexes of ‘Asian’ self-expression, authentically drawn from some kind of Asian tradition.”2 Asian-American art has been a catch-all phrase for a wide range of artistic activity, and consequently a term that frequently obscures more than it clarifies. As art historian Marci Kwon noted at a related panel at the annual College Art Association conference in 2023, the difficulty of discussing Asian American art lies in the question of “how to not replicate the violence of racial

classification while not leaving works unmarked by racial classification.” How should we linger in these contradictions while resisting the conscriptions of such unwieldy and totalizing terms like “Asian-American art?” We ought to approach the category, art historian Pamela Lee suggested at the same panel talk, with humility about the stakes involved and sensitivity to the contingencies and shifting axes of the term.

Nishiki Sugawara-Beda, creator of the sumi work KuroKuroShiro The S (2023, pl. 24), grew up studying and practicing Japanese calligraphy both at school and at home. Her philosophy of art is based on the concept of onkochishin, the Confucian concept of how the “old” informs and exists in the new, and how contemporary culture is a manifestation of deeply embedded traditions. Practicing onkochishin allows SugawaraBeda, in her words, to be “alert to the new by making a connection between the old and the new in order to move forward. The ‘old’ existed and still exists now.”

Sugawara-Beda’s ideas recall William Faulkner’s well-known statement that the past is “not even past.” Her statements help us move beyond the superficialities of the binary opposition of tradition and innovation in order to ask: how does a painting get into another painting? How does a “tradition” get smuggled into a contemporary work or practice? For guidance, we might look to the art historical methods of Aby Warburg, who attempted to theorize how pulsations of life and existence transmit and survive in art through the centuries, how pathos and principles from centuries prior can show up, still wet and breathing and slimy, in contemporary works.3 Sugawara-Beda’s practice of making her own sumi ink localizes such magical understandings of the past. She begins by burning local wood to create soot, which carries the spirit of its originary geographic location. Each subsequent artistic mark created with this soot then, through its final form of sumi ink, umbilically testifies to and constantly restages its past.

In further complicating the notion of unmediated, inherited traditions, we might also look to other artists in the show, such as Aesther Chang and Makoto Fujimura, whose works are as inflected by Eastern traditions as by their religious beliefs. Taiwanese-American artist Chang, whose painting Ether .04 (2023, pl. 4) telegraphs a weightlessness against the weightiness of our own selves, has discussed the importance of both her Christian faith and Eastern heritage (the latter which came to life for her through the well-known text In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichiro Tanizaki) in her practice. Indeed, Chang’s abstract landscape paintings, made through long processes of layering multiple layers of oil paint on canvas, seem as much imbued by Eastern ideas of natural cycles of growth, decay, and death, as her belief in the hiddenness of God, which she has conveyed in interviews. In her case, the past and the present do not function as a perfect superimposition of two images, but rather a messier entanglement of faith, tradition, and history.

Makoto Fujimura, who grew up biculturally in both the United States and Japan, undertook a traditional Japanese painting doctorate program at Tokyo University of the Arts for almost seven years. Through this profound period of study, Fujimura honed the technique of nihonga, a traditional art form based on medieval conventions and then reconfigured in the late 1800s during the Meiji Restoration as an indigenous art movement. Combining his deep love for Abstract Expressionists, particularly Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning, Fujimura began pulverizing minerals such as gold, platinum, malachite, and azurite to create iridescent works such as Interior Castle–Night (2019, pl. 12). An exquisite calibration of lightness and darkness, Interior Castle suggests a survival of the soul through aesthetic continuity. The art critic and curator Peter Frank aptly observed that for Fujimura, the cultural and philosophical differences between Western and Eastern sensibilities “require not resolution, but rather, harmonization.”4

Though thoroughly steeped and fluent in the syntax and aesthetics of traditional Japanese painting and craft, the work of Fujimura “accepts, even declares, its own spiritual, indeed religious, devotion,” operating at the “cusp of the real, in that visual border region where the everyday abuts the visionary.”5 According to the artist, it is his Christian faith—ironically enough, a religion that is Western in its origins— that attracts him to the metaphysical aspects of abstraction i n both traditional Japanese art and twentieth-century American art. In his recent book A Theology of Making, Fujimura wrote, “I now consider what I do in the studio to be theological work as much as aesthetic work.”6

The contemporary artists in this exhibition raise questions about the utmost importance and frustrating opacity of the concept of “tradition.” Who is the ventriloquist for tradition? How should we productively, ritualistically draw from the techniques and materials of our East Asian heritages, while still defamiliarizing them to narrate a more honest, interesting relationship between the past, present, and future? As historian Eric Hobsbawm suggested in his landmark study The Invention of Tradition in 1983, the stronger the language and imaginary of tradition and continuity with a historical past, the more selectively this past is usually presented. At stake in this exhibition is not necessarily prescriptions and descriptions of how tradition gets metabolized in contemporary works, but how the past lives on, ensouled, in intensified gestures. And in spite of the simultaneously insufficient and overindexed category of “Asian-American art,” such categorizations can be useful in brokering and attending to AsianAmerican art, which, as seen in this rich exhibition, compel so many different types of abstraction, each with its own compounds of visibility and invisibility.

Notes

1. Clement Greenberg, “Convention and Innovation,” in Homemade Esthetics: Observations on Art and Taste (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 52.

2. Susette Min, “Introduction,” in Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 8.

3. This description of Warburg’s theories is indebted to Alexander Nemerov.

4. Peter Frank, “Makoto Fujimura: An Immanent Abstraction,” September–October 2020, Makoto Fujimura makotofujimura.com/assets/ pdf/An_Immanent_ Abstraction.pdf.

5. Frank, “Makoto Fujimura.”

6. Makoto Fujimura, Art and Faith: A Theology of Making (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 3.

Emily Chun is a doctoral candidate in the history of art at Stanford University. Her interests include the nexus of art history, social theory, and theological thinking in modern and contemporary art, with particular attention to art of the 1980s and ’90s. She has held research and curatorial positions at the Anderson Collection at Stanford, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Tufts University Art Galleries.

American Abstract-Expressionist Artists

Influenced by East Asian Art

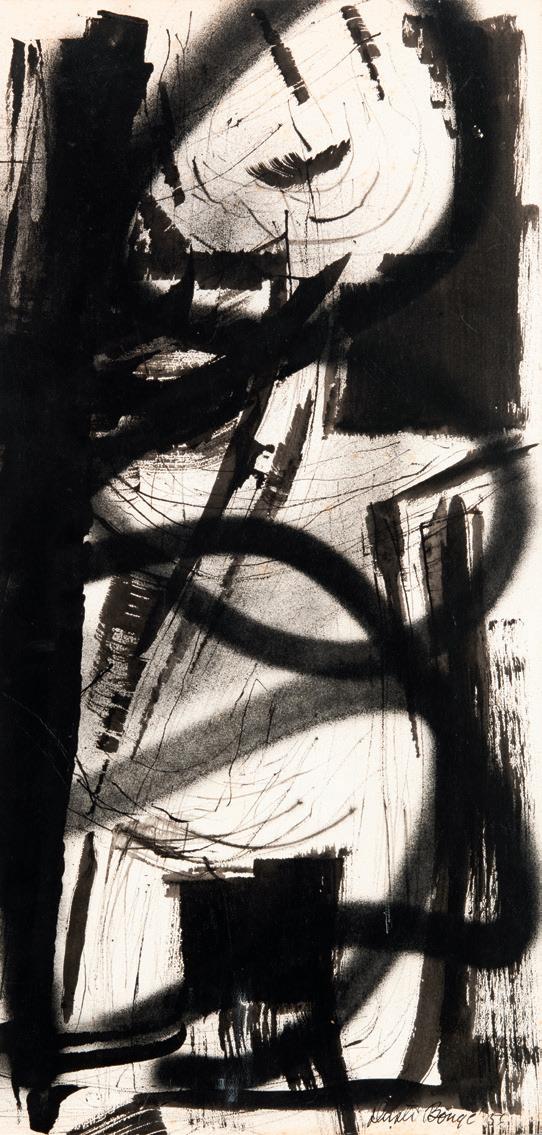

plate 34

Dusti Bongé (1903–1993)

Untitled (Black Abstract), 1956 Ink on paperboard

26 × 12 1/2 in. (66 × 31.8 cm)

The yin is black

The yang is white

Or yang is black And yin is white

Time rolls on time

One circle divided Seeking That ultimate.

plate 35

Rollin Crampton (1886–1970)

Dark Harbor, 1959–60 Oil on canvas

26 1/2 × 31 1/2 in. (67.3 × 80 cm) courtesy of Irene Sirugo

[Crampton’s] “conception of art” . . . was based on “essentially an Oriental philosophy, especially Zen.” . . . He respected Buddhism’s “regard for nature” and Zen’s “getting down to a basic sort of simplicity.”

Interview with Rollin Crampton, 1969, in Abstract Expressionism: Other Dimensions (New Brunswick, NJ: Zimmerli Art Museum, 1989), 93.

plate 36

Sam Francis (1923–1994)

Red, Yellow, and Black (SF54-069), 1954 Gouache on paper 8 3/4 × 6 1/2 in. (22.2 × 16.5 cm)

In the work of Sam Francis, Western and Eastern aesthetics engage in a profound intercultural dialogue. . . . His expressive handling of negative space shared pictorial and philosophical affinities with aspects of Eastern aesthetics, particularly the Japanese concept of ma, the dynamic between form and non-form.

“Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, lacma.org/ art/exhibition/sam-francis-and-japanemptiness-overflowing.

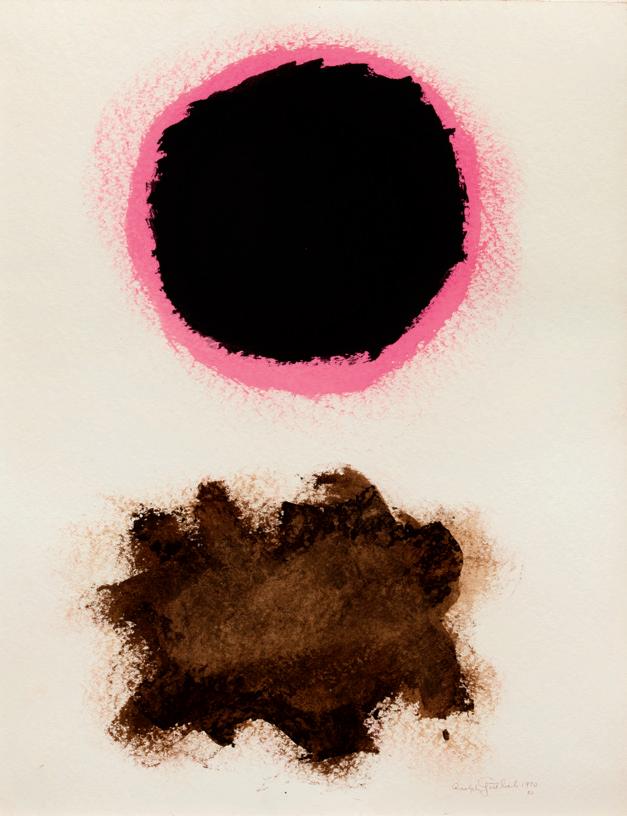

plate 37

Adolph Gottlieb (1903–1974)

Untitled, #30, 1970

Acrylic on paper 23 3/4 × 18 3/4 in. (60.3 × 47.6 cm)

[Manfred] Schneckenburger discussed the Eastern conception of bipolarities, or yin and yang, and cited an example of “Zen Buddhist brush drawings of the moon or of a circle with unconnected calligraphic characters strewn alongside,” as a depiction of such. The similitude of Gottlieb’s Bursts to these brush drawings makes them a suitable example of such bipolarity; “The circle, as a symbol of the cosmos, hovers in the upper half of the picture, while below there is the black blot: chaos.”

G. S. Russell, “‘Writing a Picture’: Adolph Gottlieb’s Rolling and Yoshihara Jiro’s Red Circle on Black,” MA thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1995, 40.

plate 38

Sheila Isham (1927–2024)

Song of the Palace – A Taoist Poem, 1965–65

Acrylic on canvas with Chinese ink 78 × 40 in. (198.1 × 101.6 cm)

Ralph Isham, New York

[Isham’s] move to Hong Kong in 1962 proved catalytic for the artist, who began rigorous study of classical Chinese calligraphy for three years and assimilated the abstract possibilities of Chinese hieroglyphs into her visual vocabulary. Returning to Washington, D.C. in 1965, Isham adapted the airbrush technique to create color abstractions that evoke dreamscapes of mottled, cloud-like forms. These she combined with chance procedures and specific titling sourced from the I Ching, reinvigorating Eastern artistic traditions and merging them with her atmospheric fields of acrylic coloration.

“Sheila Isham,” Hollis Taggart, hollistaggart.com/artists/264-sheila-isham.

plate 39

Franz Kline (1910–1962)

Untitled, 1950 Ink on paper 17 3/4 × 20 1/2 in. (45 × 52 cm)

Kline was not only looking at modern Japanese calligraphy, but was also involved in its promotion abroad . . . in the mid-1950s by introducing it to his network of American abstract artists and their benefactors. The letter to Morita shows that not long after his turn to abstraction in the late 1940s, Kline enthusiastically cherished his relationship with the Bokujinkai [Kyotobased avant-garde calligraphy group] Kline’s letter spiritedly confirmed that he felt as if he was “working very close[ly]” with Japanese calligraphers.

Eugenia Bogdonova-Kummer, discussing a letter from Franz Kline to Morita Shiryu, in “Contested Comparisons: Franz Kline and Japanese Calligraphy,” Tate, tate.org.uk/research/ in-focus/meryon/japanese-calligraphy.

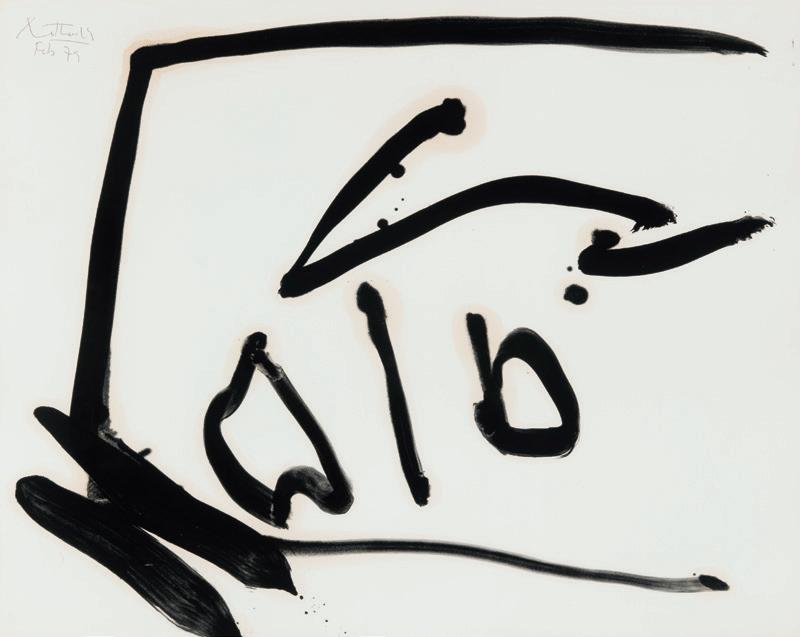

plate 40

Robert Motherwell (1915–1991)

Drunk with Turpentine, 1979 Oil on paper 23 × 29 in. (58.4 × 73.7 cm)

I have been conscious of the Oriental concept of a painting representing a void. . . . Some of my pictures are arranged that way. You learn from Japanese calligraphy to let the hand take over.

Robert Motherwell, in an interview with Jack D. Flam, in Robert Motherwell (Buffalo, NY: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1983), 13, 23.

plate 41

Richard Pousette-Dart (1916–1992)

Untitled (Black Circle, Space), 1983 Acrylic on paper mounted on board 22 1/2 × 30 1/4 in. (57.1 × 76.8 cm)

Pousette-Dart was interested in Asian philosophy (Zen Buddhism, Taoism, and the Bhagavad Gita, in particular). . . . “I strive to express the spiritual nature of the Universe,” he said. “Painting for me is . . . mysterious and transcending.”

Richard Pousette-Dart, ”Fugue Number 2, 1943,” MoMA, moma.org/collection/works/80558.

plate 42

Sal Sirugo (1920–2013) C-4, 1950

Casein on board 22 × 27 3/4 in. (55.9 x 70.5 cm) courtesy of Irene Sirugo

After so many years of utilizing black and white like the ancient Chinese painters, I have no limitations in its use. . . . There is a 17th century album of Chinese painting titled “Within Small See Large.” This is how I view my work.

Sal Sirugo, Statement, Still Working (New York: Parsons School of Design,1994).

plate 43

Vivian Springford (1921–2008)

Stain Pale Yellow, Red (VSF 738), circa 1970s

Acrylic on canvas

72 × 72 in. (182.9 × 182.9 cm)

Some of the older Chinese drawings are much more abstract than anything done today. I adapted their rhythm and free motion to develop my own abstract painting.

“The Works: Calligraphic Works, 1957–1963,” Vivian Springford Archives, vivianspringford. com/calligraphy.

plate 44

Theodoros Stamos (1922–1997)

Untitled, circa 1950–52 Oil on canvasboard

19 7/8 × 29 7/8 in. (50.5 × 75.9 cm)

[In] 1951, Stamos began a series of paintings influenced by Asian philosophy and Japanese calligraphy. In an undated essay by Stamos “Why Nature in Art,” he focuses on how the Asian artist related to nature, “the eastern artist tried to become the object itself.”

“Theodoros Stamos,” Art in Embassies, U.S. Department of State, art.state.gov/personnel/ theodoros_stamos/.

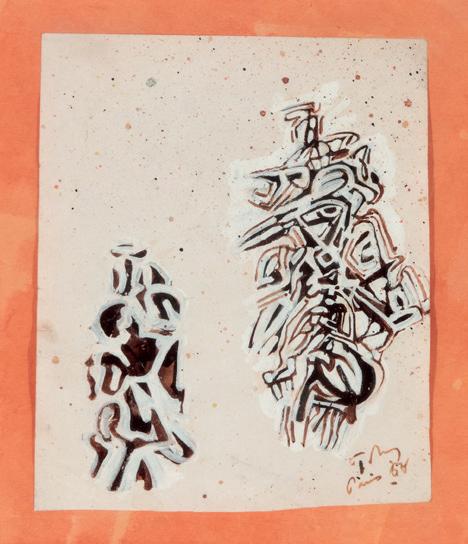

plate 45

Mark Tobey (1890–1976)

Totem #2, 1953

Tempera on paper 6 × 5 3/8 in. (15.2 × 13.7 cm)

He found Zen released him . . . and he took as his own the Japanese emphasis on . . . simplicity, directness, and profundity. He accepts the idea of accident, and especially the freedom of the “flung” style. . . . More importantly, China and Japan gave the final encouragement to Tobey’s natural “writing impulse,” and to his idea that forms could migrate from Orient to Occident.

plate 46

Michael (Corinne) West (1908–1991)

Nyo Ze Tai, 1975

Oil on canvas

52 × 18 inches (132.1 × 45.7 cm)

To the calligrapher

It seems that the world is “Written” —

“Recreating the Creation”

Until everything seen or felt is unnamed & wound up again until it becomes the sky & the air & energy — & space —

the soul of things — the structure of things

Structures & soul are so close

Notes – Mich West, circa 1950s, The Michael (Corinne) West Estate Archives.

This catalogue has been published on the occasion of the exhibition

“Asian-American Abstraction: Historic to Contemporary” organized by Hollis Taggart, New York, and presented from July 11–September 7, 2024.

“Historical Art Becomes Modern: From East to West” © Jeffrey Wechsler “Notes on Tradition, Newness, and Asian-American Art” © Emily Chun

ISBN: 979-8-9902841-9-7

Publication © 2024 Hollis Taggart All rights reserved. Reproduction of contents prohibited.

Hollis Taggart

521 West 26th Street 1st & 2nd Floors New York, NY 10001 Tel 212 628 4000 www.hollistaggart.com

Catalogue production: Kara Spellman Copyediting: Jessie Sentivan Design: McCall Associates, New York Printing: Point B Solutions, Minneapolis Photography: Joshua Nefsky, New York

Front and back covers: Chinyee, Dragon Dance (detail), circa 1955

Frontispiece: Wang, Ming, Book (detail), 1996 Page 4: Sam Francis, Red, Yellow, and Black (SF54-069) (detail), 1954

© 2024 Sam Francis Foundation, California/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY (p. 4 and pl. 36) // © Idemitsu Art Museum (fig. 2) // © The Estate of Sal Sirugo (fig. 7 and pl. 42) // © Ralph Iwamoto Estate (pl. 14) // © Kikuo Saito Estate, photographed by Jason Mandella (pl. 22) // © 2024 Estate of Walasse Ting/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (pl. 27) // © Dusti Bongé Art Foundation (pl. 34) // © Estate of Rollin McNeil Crampton (pl. 35) // © 2024 Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation/ Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY (pl. 37) // © Sheila Isham Estate (pl. 38) // © 2024 The Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (pl. 39) // © 2024 Dedalus Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY (pl. 40) // © 2024 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (pl. 41) // © The Estate of Vivian Springford (pl. 43) // © Estate of Theodoros Stamos (pl. 44) // © 2024 Mark Tobey/Seattle Art Museum, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (pl. 45) // © The Michael (Corinne) West Estate (pl. 46)