290 SHERBOURNE STREET A HOUSE HISTORY

PETER J. MARSHALL

Published 2023 by Hogtown House Histories Toronto, Canada www.househistories.ca

Printed and bound in Canada by The Printing House

Cover illustration: Jake Tobin Garrett

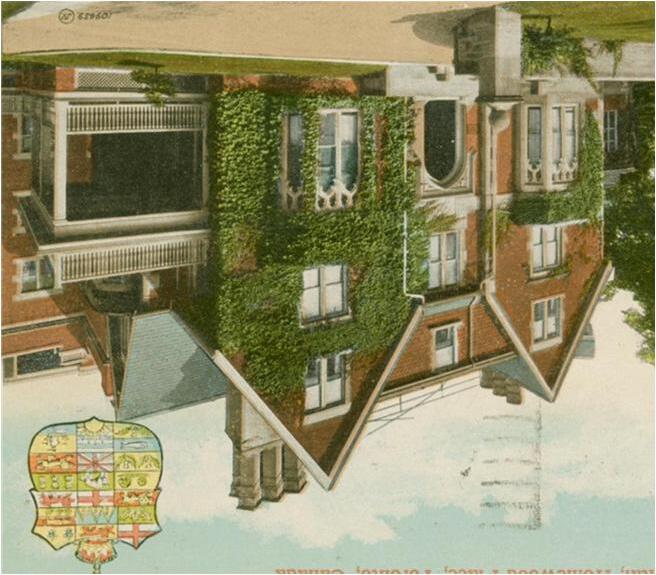

Frontispiece photo: Tim Ford

The city of Toronto is located on the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. The city is covered by Treaty 13 signed with the Mississaugas of the Credit.

It was a mistake to think of houses, old houses, as being empty. They were filled with memories, with the faded echoes of voices. Drops of tears, drops of blood, the ring of laughter, the edge of tempers that had ebbed and flowed between the walls, into the walls, over the years.

Wasnʹt it, after all, a kind of life?

And there were houses, he knew it, that breathed. They carried in their wood and stone, their brick and mortar a kind of ego that was nearly, very nearly, human.

Nora Roberts, Key of Knowledge

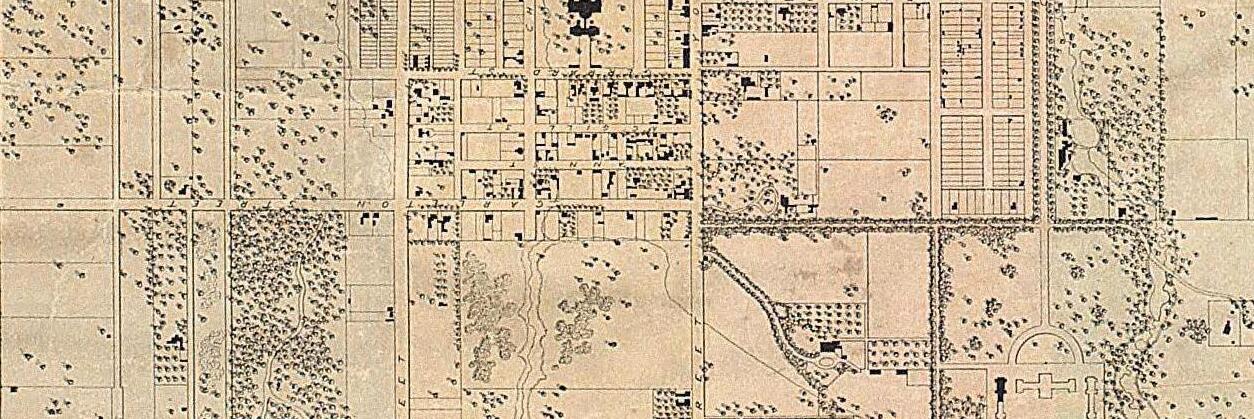

Every property in Toronto located between Queen and Bloor Streets can trace its ownership back to John Simcoe’s 1793 scheme to lure Upper Canada’s nascent gentry to the newly founded town of York. Having decided that the remote outpost would become the province’s temporary capital, the Lieutenant Governor enticed senior members of the military, government and judiciary to relocate there from the current capital of Newark (Niagara‐on‐the Lake) and the more prominent settlement of Kingston by offering 100‐acre “Park Lots” for just £1 per acre.

These estates were laid out in narrow north‐south tracts running between present day Queen and Bloor Streets and the story of 290 Sherbourne begins with Park Lot 5, bounded by present day Sherbourne and George Streets, first being granted to Chief Justice William Osgoode in 1793.

ABOVE: Upper Canada Lt. Governor John Graves Simcoe. (Government of Ontario Art Collection)

OPPOSITE: 1851 Topograph‐ical Plan of the City of Toronto by Sandford Fleming overlaid with Park Lot boundaries. (University of Toronto Map and Data Library)

Osgoode turned down the offer and remained in Newark prompting the lot to be re‐assigned to Deputy Surveyor David William Smith in 1798. In 1819 Smith returned to England and sold the land to Duncan Cameron for £500 who transferred it a week later to William Allan, a businessman, politician and land speculator who was one of York’s wealthiest citizens.

Allan began development of the property by erecting his grand Moss Park mansion in the south half of the Park Lot and constructing a road along the tract’s eastern boundary which became known as Allan’s Lane. In 1844 he and Thomas Gibbs Ridout, the owner of neighbouring Park Lot 4, agreed to replace the lane with a proper street by utilizing the eastern twenty feet of Allan’s land and western 30 feet of Ridout’s. Ridout asked the city to name the new road Sherborne Street after the English town where his father had been born. Like many other Toronto street names, the spelling would eventually be arbitrarily altered, resulting in the addition of a “u” within a few years.

Initially, the street’s northern and southern terminus were determined by geographical barriers: the Rosedale Valley ravine prevented it from extending north of Bloor Street while Taddle Creek prevented its connection to Caroline Street due south of what is now Queen Street.

Two years later in 1846, Allan granted the north half of the Park Lot to his only surviving son George William Allan as a wedding gift. Soon after that, Carlton and Gerrard streets were extended through the Park Lot prompting George to build his own mansion north of the former. George inherited the remainder of the family property when his father died in 1853 and began to subdivide it not long after.

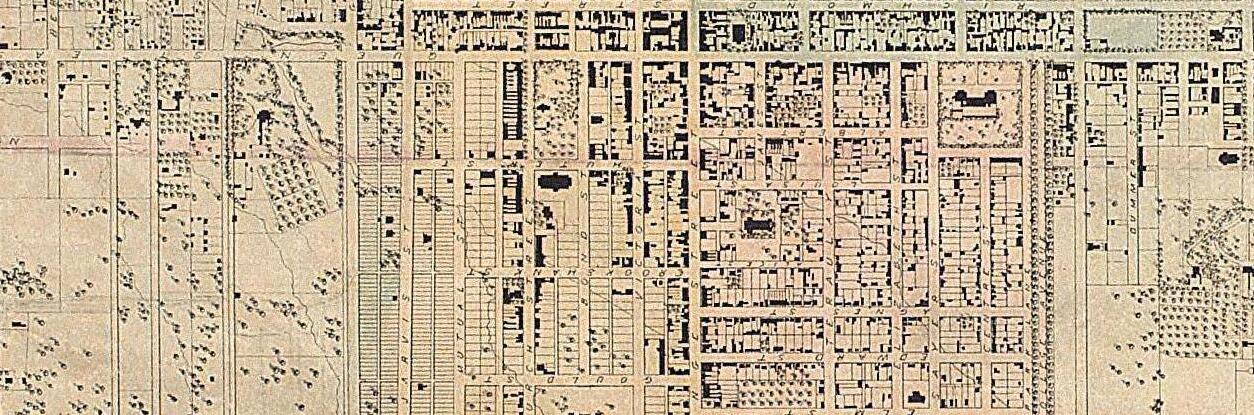

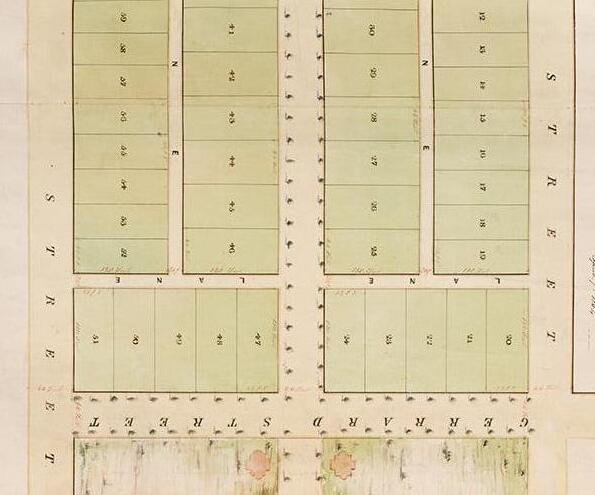

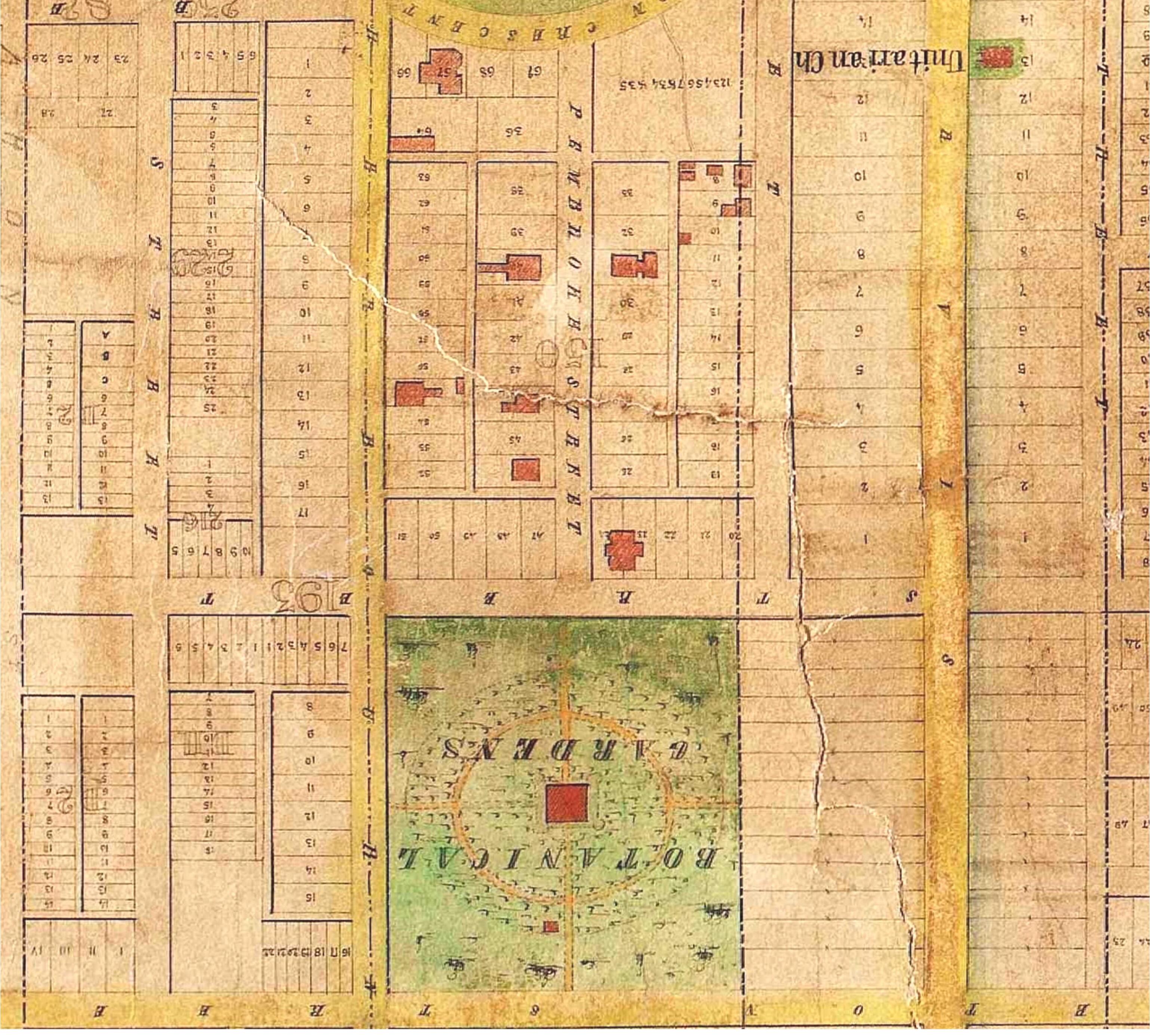

His first initiative was to section off the area between Gerrard, George, Sherbourne and present day Dundas Streets in 1854. (The western boundary of Park Lot 5 actually fell twenty‐four feet shy of George Street in neighbouring Park Lot 6 but Allan had presciently purchased that strip of land from owner Samuel Jarvis two years earlier.) Allan’s plan included designating building lots along Sherbourne that were fifty feet wide and 138 feet deep and accessed by a north‐south laneway behind them that also serviced lots along the newly constructed Pembroke Street.

With the official registration of this survey as subdivision plan number 150 in March 1856, the stage was set for the construction of the first house to bear the address 290 Sherbourne.

George W. Allan’s Home Wood mansion, erected circa 1847. By the mid 1850s the house name was contracted to a single word and lives on today in Homewood Avenue, the street that replaced the mansion’s original driveway. (Painting by Paul Kane)

RIGHT: George Allan’s 1854 subdivision of a portion of his lands into building lots. The plan included the creation of two new streets: Wilton Crescent to the south—later incorporated into Dundas Street—and tree‐lined Pem‐broke Street. Allan originally intended for Pembroke to lead to a mixed development of stately homes and gardens between Gerrard and Carlton but he later donated that land to be used as a Botanical Gardens. (Toronto Public Library Baldwin Collection)

OPPOSITE: An 1863 illustra‐tion of the Victoria Skating Rink at the southwest corner of Gerrard and Sherbourne which was open to paying members from 1862 to 1866. The drawing also contains the earliest known depiction of the new Botanical Gardens, officially opened three years prior and later re‐christened as Allan Gardens after George’s death. (Toronto Public Library Baldwin Collection)

In 1857 George Allan had the first house constructed on the west side of Sherbourne Street, a detached dwelling located on lot 55 of his new subdivision where the current 290 and 292 Sherbourne now stand. The two‐and‐a‐half‐storey structure – originally numbered 148 Sherbourne – was constructed of brick with a one‐storey wood extension in the rear and a wood outbuilding which was likely stables. Although Allan never resided there himself, the size of the home and the status of its occupants attest to a distinctly upper‐middle class nature.

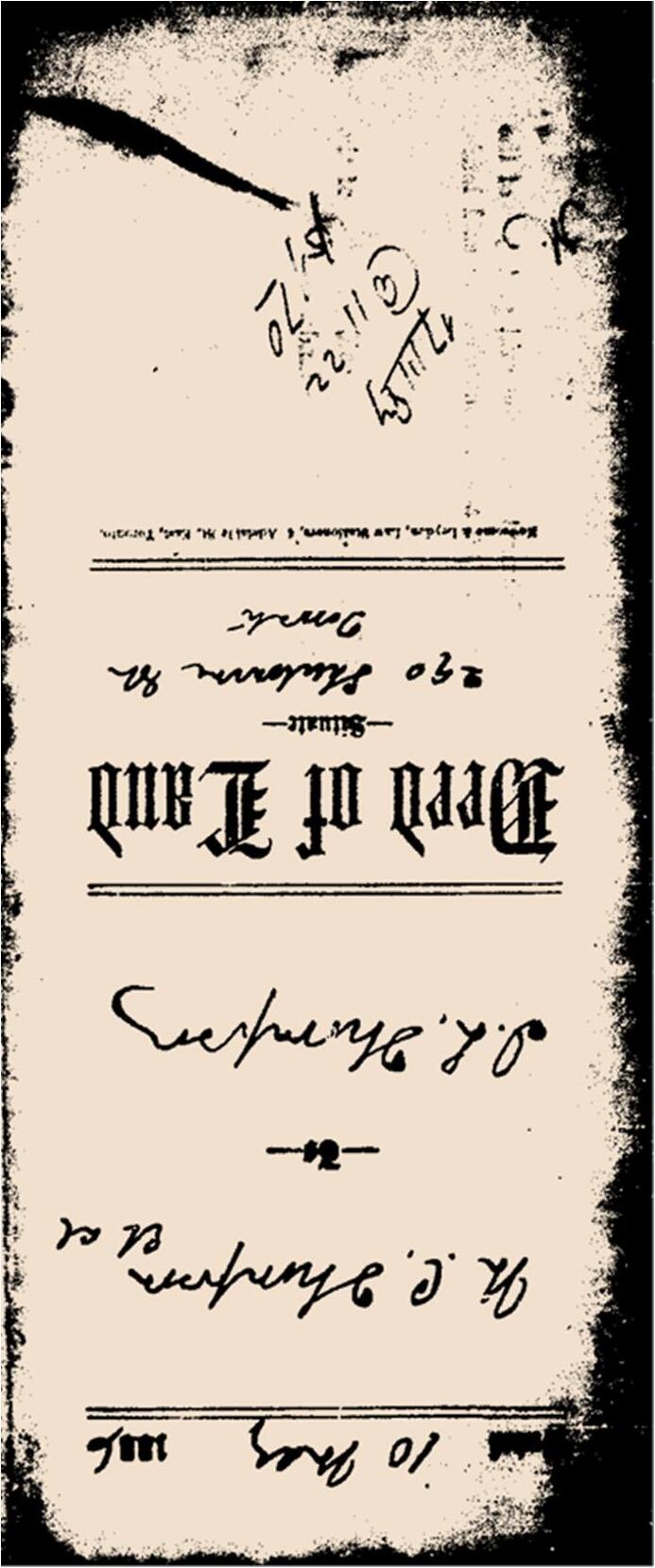

Allan leased the home to renters until selling it in 1868 to John Herbert Mason along with 200 feet of Sherbourne Street frontage spanning lots 54 through 58. Mason’s success as Secretary and Treasurer of the Canada Permanent Building Society allowed him to afford not only the $4,600 purchase price but also the luxury of three

OPPOSITE and ABOVE: Excerpts from 1862 Plan of the City of Toronto by H. J. Browne. The outline indicates the property sold with the house in 1868. (University of Toronto Map and Data Library)

live‐in servants to service a household of seven children. The family remained until 1877 during which time Sherbourne was finally linked to Caroline Street after the city filled in the ravine that had separated the two roads. The incorporation of Caroline into Sherbourne Street not only extended the latter to the lake but also necessitated the renumbering of its homes, with the Mason residence changing its address to 290.

The next owner was hardware manufacturer and merchant James Booth who acquired the house and 225‐foot parcel of land for $12,500 (Mason having bought an additional twenty‐five feet from Allan for $250 in 1869). Booth constructed three new houses on the property and moved into number 280 while renting the others. 290 was leased along with fifty feet of land for $400 per year and Booth’s tenant from 1879 through 1886 was Janet Merritt and her family. Janet had been widowed in 1860 at the age of thirty while pregnant with her third child and was now living with her two adult daughters. However, she was by no means destitute as the 1881 census reveals that the household also consisted of an eighteen‐year‐old butler and seventeen ‐year‐old housemaid.

Booth died in early 1880 and in April 1885 his widow Mary sold the house and fifty‐foot plot to Mary and John Thompson for $5,500. On a per‐acre basis, this amounted to more than twice the price that the Booths had paid just eight years prior which was a clear indication of Sherbourne’s evolution into one of Toronto’s preeminent residen‐tial avenues. An early history of Toronto published in 1884 vividly described just how impressive the neighbourhood was at the time:

Of all the avenues extending south from Bloor Street to the Bay, the noblest are Church, Jarvis and Sherbourne

Streets . . . Jarvis and Sherbourne are lined on either side through most part of the extent by the mansions of the upper ten. Of a summer evening it is pleasant to saunter down one of those streets while the thick verdure of the chestnut trees is fresh with the life of June, and the pink and white bunches of blossom are as beautiful as any of the exotic flowers and gardens of the houses.

On Sherbourne Street, those mansions of the “upper ten” – the city’s most elite families – included the residences of various Gooderhams (of the prosperous Gooderham & Warts distillery), a number of Pellats (one of whom would later build Casa Loma), Edward J. Lennox (arguably Toronto’s most significant architect) and John Ross Robertson, the highly influential historian and newspaper publisher whose stately home across the street at 291 Sherbourne still stands today. The street’s picturesque chestnut blossoms and Allan Gardens’ splendid landscapes were shared by these families with residents from all over the city thanks to horse‐drawn streetcars that had been introduced to Sherbourne in 1874.

Itʹs no wonder that the Thompsons decided the property was worth the expense of a $5,000 mortgage, especially since John was a real estate agent and would have doubtless understood the area’s tremendous development potential. Sure enough, just fourteen months after buying the lot he sold it to his brother Joseph Logan Thompson for a $1,000 profit.

Like John, Joseph was more interested in the prospective value of the land rather the worth of the vacant home. And being a builder by trade he knew just how to maximize that potential: double the number of houses.

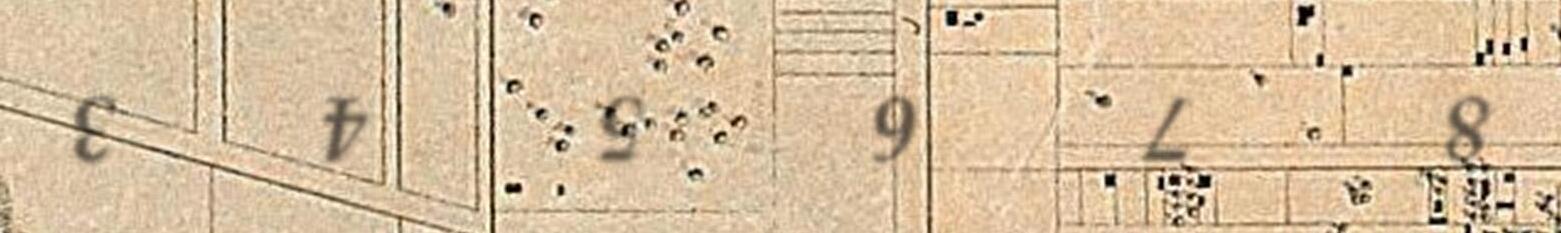

By the close of 1886 Thompson had taken out separate $4,000 mortgages on the north and south halves of his property. After pay‐ing off the $5,000 loan he had assumed from his brother, he used the remainder of the funds to demolish the existing house and construct a pair of semi‐detached homes in their place the following year.

The two‐and‐a‐half‐storey brick dwellings were designed in the handsome bay and gable style that proliferated Toronto during its Victorian building boom. Although built as a pair, the two homes were asymmetrical in their designs with the most notable variation being the placement of the main entrance on the side of number 290 rather than facing the street like its neighbour.

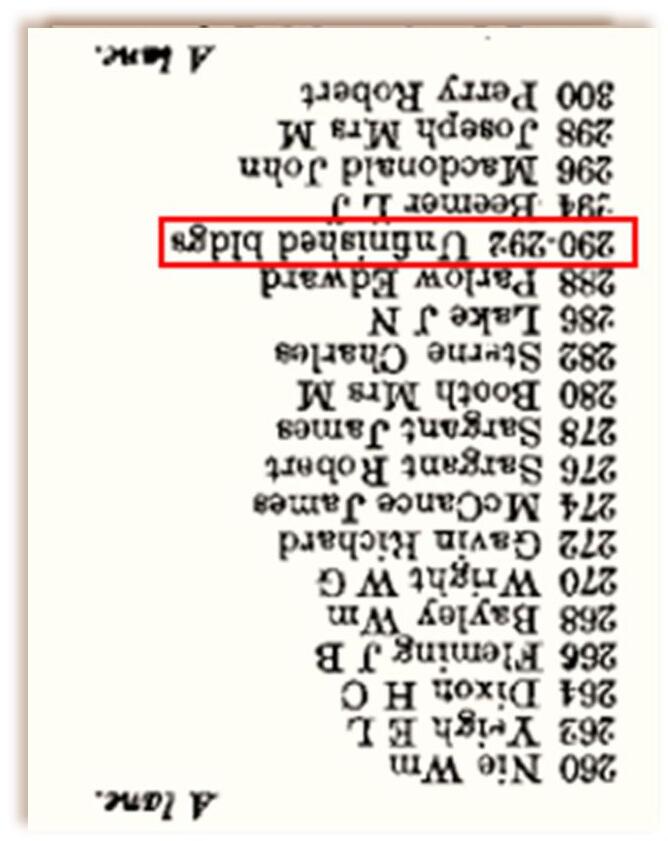

ABOVE: The first appearance of the semis in the Toronto City Directory for 1888, compiled in 1887. (Toronto Public Library)

OPPOSITE: The 1892 Goad’s Insurance Plan of the City of Toronto shows the new semis soon after construction. The location of the predecessor house is outlined in white. (University of Toronto Map and Data Library)

A year after construction, Thompson sold both semis with their combined fifty‐foot frontage to Frederick Macqueen and Allan Pyne in June 1888 in exchange for a land swap and their assumption of the two new mortgages. Later that same year Macqueen officially subdi‐vided the property into two twenty‐five‐foot lots when he sold 292 Sherbourne for $8,500 plus the corresponding $4,000 mortgage, while keeping 290 as a rental property.

290 Sherbourne’s original tenant was lawyer William Albert Reeve, his American wife Sarah and their nine children. The forty‐seven‐year‐old Toronto native had recently begun his own practice and was appointed principal of the newly re‐opened Osgoode Law School the same year he moved into the new house. By all accounts he was a gifted criminal lawyer and very popular with his students which made his sudden death a few years later a great loss. He died in his bedroom in May 1894 and the subsequent funeral at the home

was attended by leading members of the city’s legal profession as well as students from the law school.

Macqueen and Pyne eventually sold number 290 in 1899 to forty‐three‐year‐old dry goods merchant Robert Stanley for $4,500, notably less than their selling price for the other semi. Despite the low price and lack of a mortgage to assume, Stanley still needed to take out a $4,300 loan to afford the purchase.

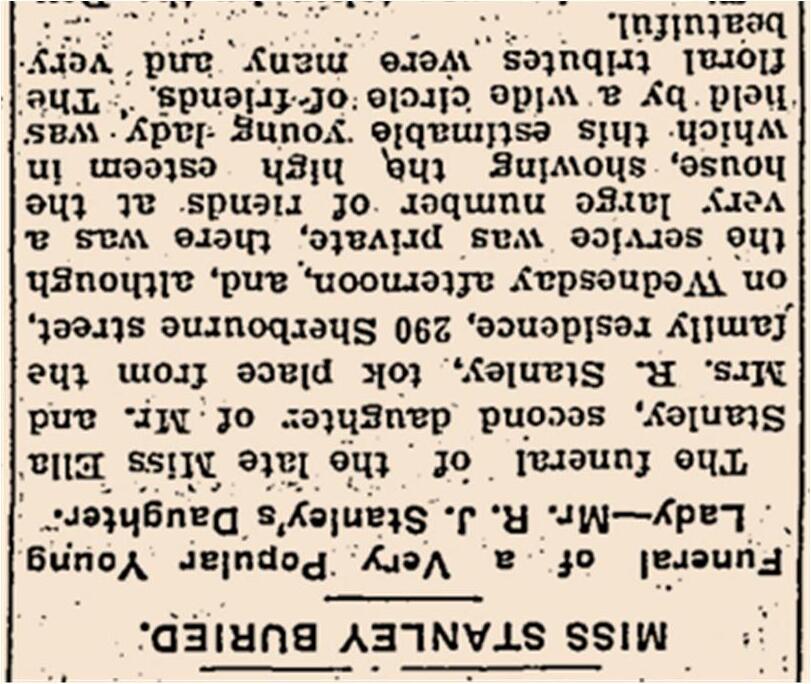

For the next eleven years Robert and his wife Sarah, both Irish immigrants, raised their family in the house. According to the 1901 census that family consisted of three sons and three daughters ranging in age from eight to twenty years. Tragically, sixteen‐year‐old daughter Isabella died at the house in 1909 due to dilation of the heart. Her loss was profound according to The Toronto Daily Star’s report on the funeral service at the home.

The Stanleys relocation to Rosedale in 1910 – and Sherbourne Street’s extension into the posh neighbourhood twenty years earlier –was indicative of a broader shift in downtown Toronto’s de‐mographics during the Edwardian era. The city had grown signifi‐cantly since its upper class had first laid down roots on the relatively remote parklands of Sherbourne and Jarvis Streets and the neighbour‐hood’s affluent residents were now decamping further away from the city’s increasingly busy and dirty industrial core.

ABOVE: Toronto Daily Star, April 17, 1909.

BELOW: In 1912 George Allan’s Homewood mansion was converted into the Welles‐ley Private Hospital, part of larger trend of repurposing large single‐family homes throughout the city. (Toronto Public Library Baldwin Collection)

In their wake, many of the former mansions were adapted for commercial or charitable use such as hospitals, private hotels, funeral homes or housing for unmarried mothers. But the most common conversion was into boarding houses. Typically, these consisted of a primary family that either owned or rented the premises and earned supplemental income from lodgers. This was the model utilized by the subsequent owners of 290 Sherbourne for decades to come with the house become increasingly rundown and over leveraged as a result.

The process began with the Stanleys taking out a $4,100 mort‐gage the day before they sold the house, which Elizabeth and James Hammill assumed as part of the $11,100 purchase price. The Hamills in turn borrowed another $2,200 only to pass both mortgages on to John Diamond in the same year when he bought the home with a $7,000 cash payment. Two months later in February of 1911 Diamond followed a similar routine, handing down the mortgages to Francis Perkins who provided a land swap in lieu of down payment. The rapid‐fire speculation finally came to an end in 1912 when the property was transferred to Wilbert Grace in exchange for yet another transfer of the two mortgages plus an additional $8,750 up front. Unlike his predecessors though, the 40‐year‐old single machinist was in it for the long haul.

None of these owners actually lived in the residence, but histori‐cal records provide glimpses of the tenants that did call 290 Sherbourne home during the early years of its board‐ing house tenure.

OPPOSITE: Sherbourne Street looking south toward Carlton, circa 1910. The road was one of the first in the city to be paved in 1890 and two years later was fitted for electric streetcar service.

BELOW: Wilbert Grace’s signature from the 1935 deed.

The 1911 census entry for 290 Sherbourne showing the names, marital status, birth dates and ages of its residents, along with their relationship to the head of the household.

The 1911 census reveals that the repurposed dwelling was first occupied by forty‐five‐year‐old railway conductor David Gall, his twenty‐seven‐year‐old wife Lola and teenage son Archie, along with a domestic servant named Margaret Baker and six lodgers ranging in age from sixteen to thirty‐one. The youngest of these – Sadie Baker –was no doubt a relative of the live‐in servant considering that it would have been unheard of for a teenage girl to live on her own at the time, regardless of her employment as a factory worker.

When the dark clouds of war rolled across Europe in 1914 the im‐pact was felt in virtually every Canadian home and 290 Sherbourne was no exception. The Toronto Daily Star of February 1, 1916 carried photographs of the members of No. 5 Platoon, 95th Battalion who were then training at the Exhibition grounds for overseas service. Included in this roster was John J. S. Bell identified as residing at 290 Sherbourne. City directories from this time do not list Bell as living in Toronto so it was likely that this twenty‐year‐old banker from Pickering stayed there just long enough to enlist in October 1915 and begin his training. He would be shipped overseas in May 1916,

John Johnson Stewart Bell was of the forty‐one young men training to fight in World War One who were featured in The Toronto Daily Star on February 1, 1916.

wounded by gunfire in France on July 28, 1917, admitted to hospital in England on August 1, 1917 then finally succumb to his injuries four days later at the age of only twenty‐two.

Sadly, Bell would not be the only casualty of war connected to this home. In November of that same year enlistment papers for twenty‐two‐year‐old Vincent Moore recorded his next of kin as his mother Sarah residing at 290 Sherbourne. He too would never return to the house, as he was killed in France in October of the following year.

The next decennial census in 1921 listed a single clerk named Clara Lipport age twenty‐two as the head of household. Living with her were her twenty‐three‐year‐old bookkeeper sister Emma along with four single male lodgers ranging from twenty‐seven to thirty‐one years.

It appears that Grace’s investment in the property was initially successful as he managed to pay off both mortgages within five years of its purchase and did not take out another until 1931 when he bor‐rowed $3,600. However, by the middle of the Great Depression he was in dire financial straits judging from his sale of the house in 1935 to Thomas Farrell for nothing more than a promise to take on the out‐standing mortgage (which had been reduced by only $50 in the inter‐vening years) and to agree to an IOU to Grace for another $900. That amounted to a total value of only $4,450 compared to the $15,000 Grace had paid twenty‐three years prior.

Farrell fared even worse. In 1942 the house was seized by his mortgage holder who then offloaded it for $500 cash and a $1,800 mortgage, a paltry $2,300 total value.

By this time Sherbourne Street was a shadow of its former self. While most of its original Victorian homes were still standing, their conversion to boarding houses and commercial usage had dimmed the street’s original grandeur, as did the removal of many of its original chestnut trees when it was widened around 1939. Conversely,

the replacement of street car service with quieter buses in 1942 may have been a welcome change for local residents and the neighbour‐hood had managed to avoid nearby Jarvis Street’s transformation into a red light district that resulted from a proliferation of licenced beer rooms on that strip in the 1930s.

In the decade following its forfeiture, the property was flipped four times before ending up in the possession of Helen Hladich in 1952 for total value of $9,000. Hladich then converted the house into an apartment‐style residence as evidenced by real estate classified ads the following year stating that the furnished rooms now featured kitchenettes.

The opportunity to earn $425 in monthly rental income appealed to Frederick and Gladys Vaughn who bought the house that year for $5,000 cash in addition to assuming over $8,300 in unpaid mortgages and borrowing an additional $5,200 from Hladich. The total price of $18,500 may have been a windfall for Hladich but apparently was a bust for the Vaughns as they sold the house three years later at a $4,000 loss.

The new owner, Milada “Millie” Muhle, made a similar purchase arrangement consisting of $4,250 cash, $8,310 in existing mortgages and a $1,940 new mortgage with the Vaughns. However, the fifty‐

The row of historic houses across the street from 290 Sherbourne were slated for demolition in 1971 to make room for two apartment towers until local activists halted the work. Ultimately this led to the city buying the properties and the new Toronto Non‐Profit Housing Corporation develop‐ing the city’s first “infill” hous‐ing behind them. (Canadian Housing Design Council)

four‐year‐old nurse’s assistant from St. Michael’s Hospital would turn out to have much more staying power as she remained a proprietor and occupant for the next twenty‐three years, tying Wilbert Grace’s record as the house’s longest owner.

During Muhle’s tenure Sherbourne Street underwent significant redevelopment, particularly on its east side. The section north of Wellesley Street was rezoned to allow the replacement of its original homes with the sprawling St. James Town apartment towers in the 1960s and a similar upheaval occurred south of Dundas Street. Closer to 290, a gas station was erected at the southeast corner of Gerrard

Street in 1964, the Sherbourne Lanes non‐profit housing project was constructed south of the station in 1976, and an apartment building and new townhouses replaced many of the block’s heritage Victorian homes on the west side of the street.

Muhle passed away at her residence in 1979 at the age of seventy‐seven. She was likely single judging by her obituary’s omission of the usual references to surviving family members and the fact that a Public Trustee was assigned to dispose of her estate. As sad as her passing would have been for her friends and colleagues, it nonetheless marked a new beginning for the long‐neglected house.

James and Margaret Beveridge were in their early sixties when they purchased 290 Sherbourne in 1980. James was a prolific docu‐mentary filmmaker for the National Film Board and the first chair of York University’s film department Throughout his career he had often collaborated with Margaret on his projects which led the couple and their three children to travel the world. The pair were able to pay the $106,000 purchase price in cash and were unencumbered by hand‐me‐down mortgages which had finally been paid off by a frugal Muhle during her previous ownership.

Their new home was suitable for a documentary of its own. Decades of neglect during the boarding house years had taken its toll to the point that when the couple took possession they had to

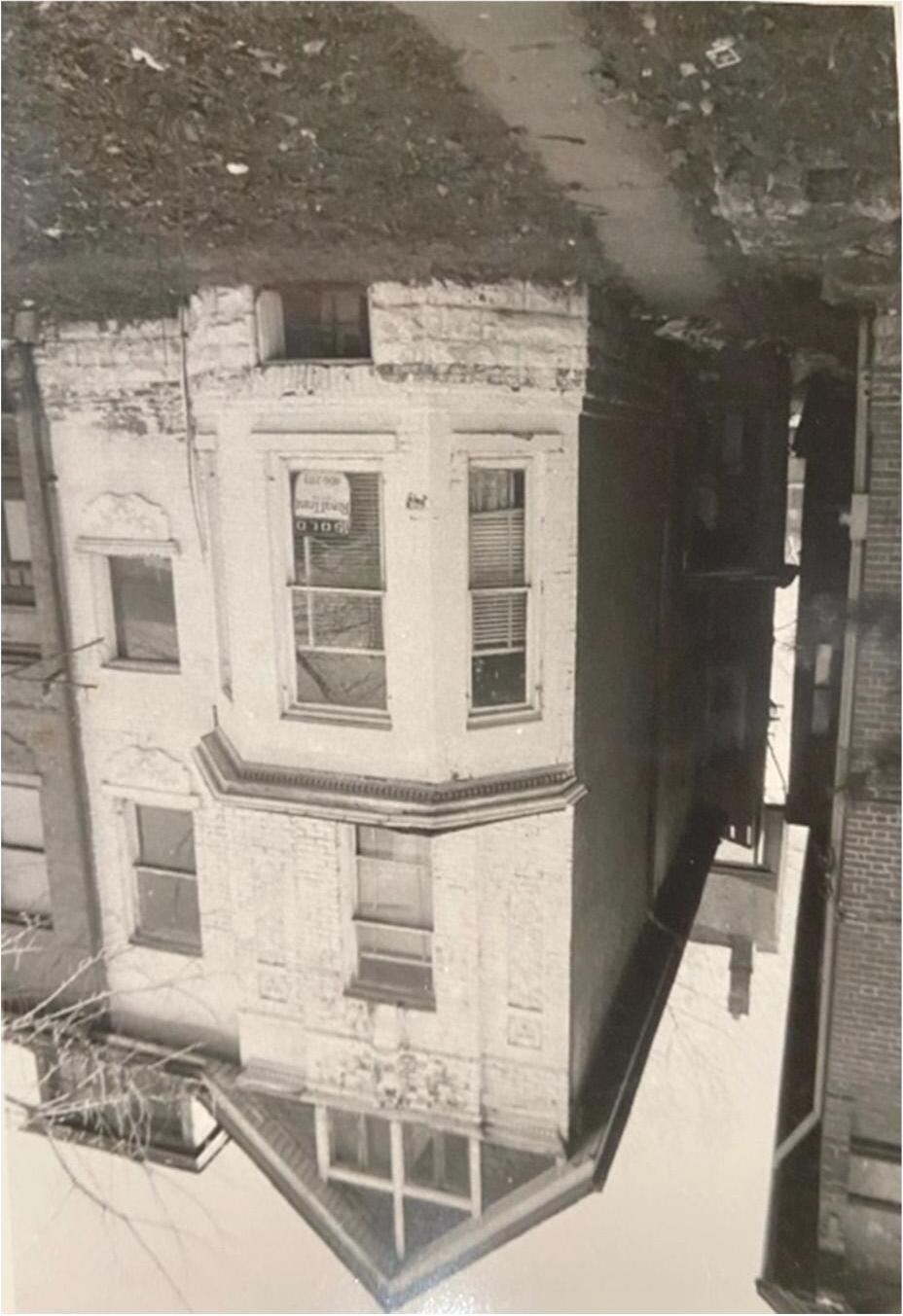

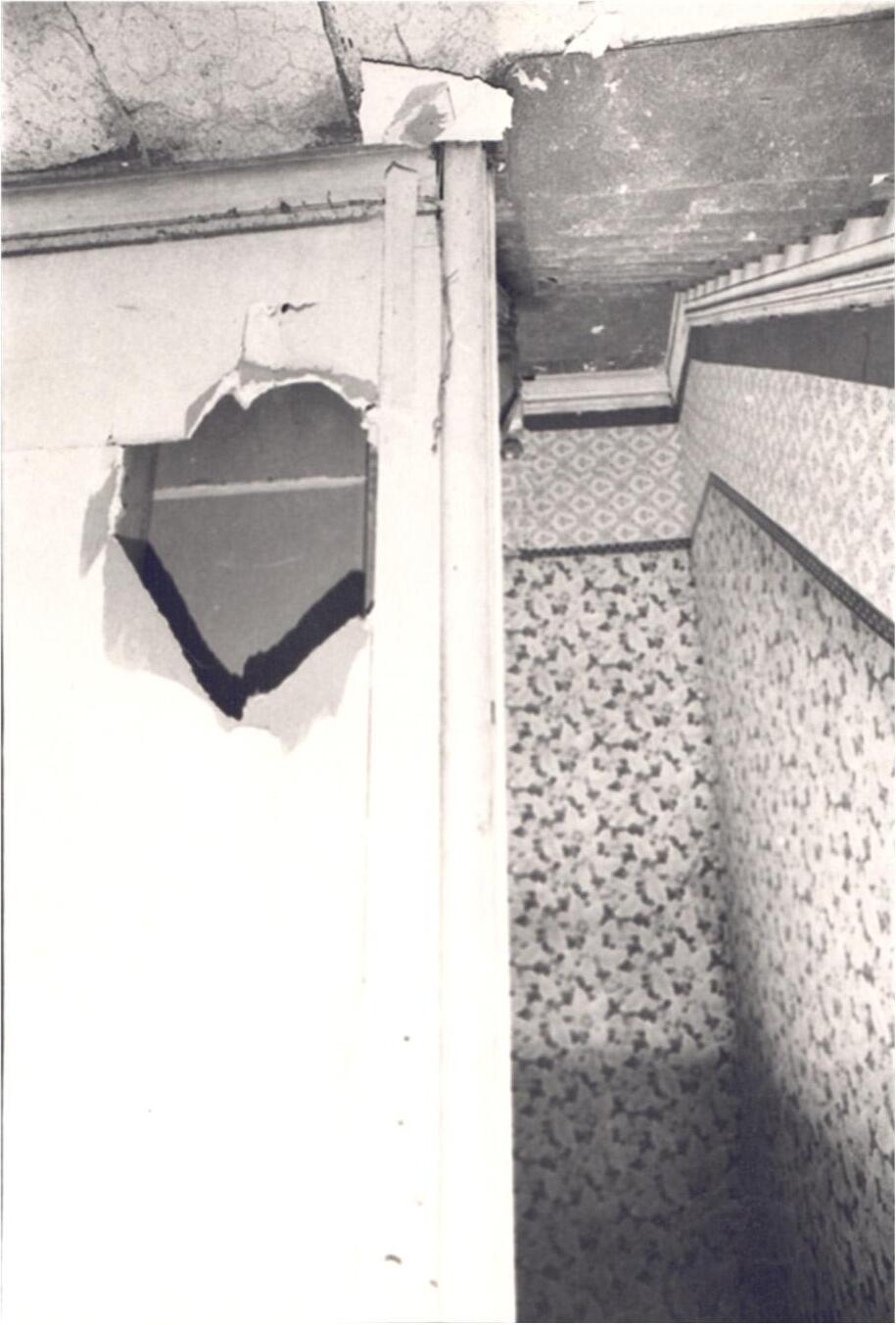

OPPOSITE: The state of the house in February 1980 as photographed by the Beveridges’ renovation coordinator. Top Left: the whitewashed exterior and barren front yard. Top Right: The third floor landing. Bottom: The dining room with a makeshift closet to the right. The crumbling ceilings and walls along with decaying flooring were ubiquitous throughout the derelict home. (All photos courtesy of Tim Ford)

physically prevent the boarders from walk‐ing out with the fireplace mantles. With the help of a $35,000 mortgage they undertook extensive renovations including the addi‐tion a sunroom to the back of the house and creation of two self‐contained apartments in the basement and on a portion of the second and third floors. Outside, they landscaped the barren grounds and stripped away the exterior paint previously applied as a cheap attempt to freshen the house’s dilapidated appearance as was common in the sixties and seventies. In the end, their loving restoration was a perfect gift for the house’s centennial anniversary in 1987.

Margaret was able to enjoy the home for ten years before passing away in 1990 and James followed her three years later. The house was left to their two sons and daughter Nina, a computer graphics artist who had been living in one of the house’s apartments. In 1995 Nina bought out her brothers for $183,000 and set up her business on the main floor while living on the upper levels. During her residency she realized she wasn’t the only occupant and later recounted:

I always felt the top bedroom in the middle of the house was haunted and I had a very real experience one night with a visiting spirit. It was after that, that I was told by a neighbour that the previous owner had died in that room. Very terribly, she had a stroke and was paralyzed in her bed and apparently her tenants robbed her in her room while she was still alive.

Nina did not remain at the house long, selling it in 1997 for $305,000 to the current owner, Tim Ford. Ford would undertake his own significant renovations, updating the kitchen in 2004 and in 2008 incorporating the apartment on the upper floors back into the rest of the house to use as the offices of his video editing business.

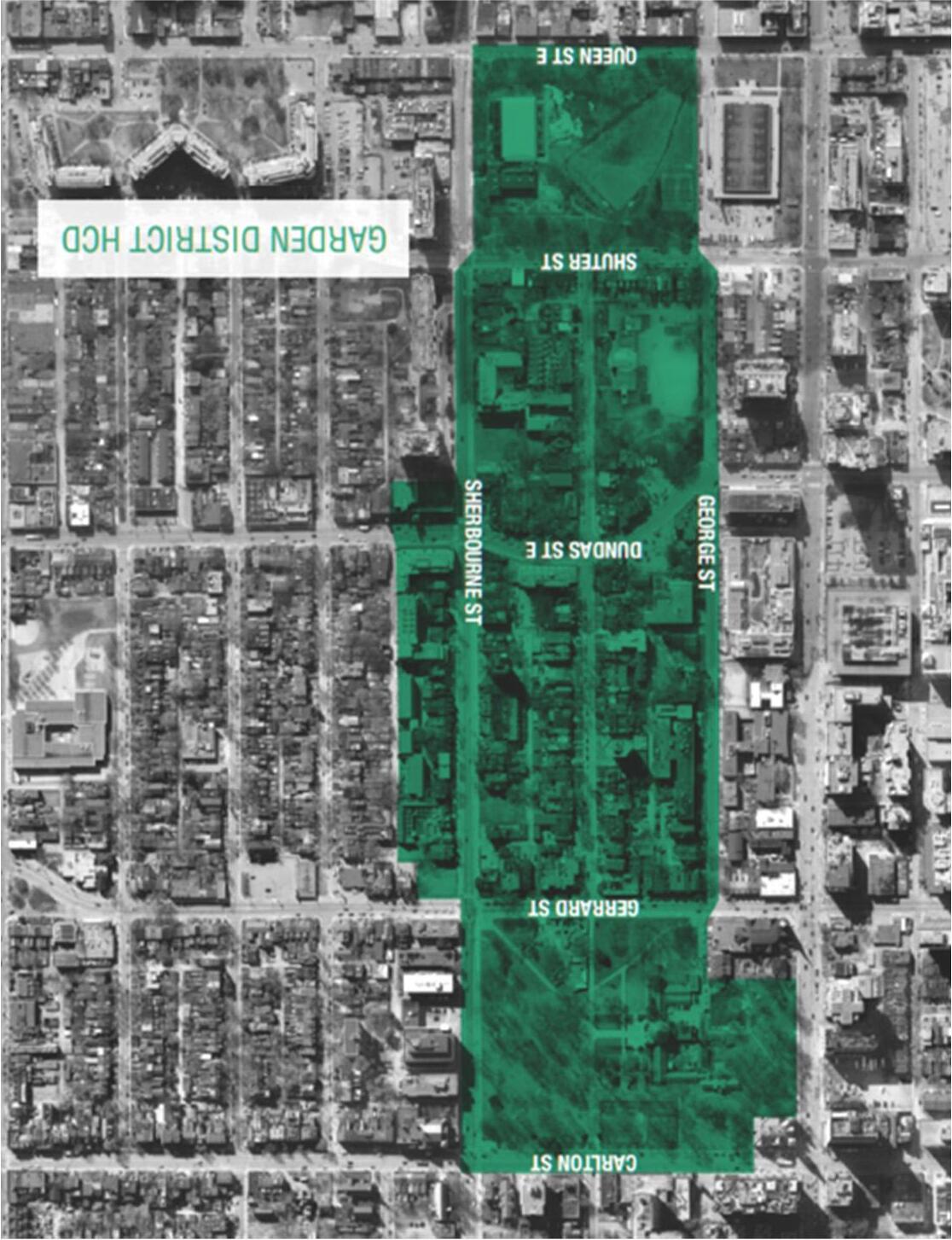

Developments in the surrounding area were not as much of a good news story. Prostitution emerged from the beer rooms onto the sidewalks of downtown east in the 1970s and in subsequent decades the area’s numerous flophouses, homeless shelters and social services centres gave rise to an increasing population of homeless persons, many of them suffering from addiction and mental illness. Conse‐quently, the Dundas‐Sherbourne area would become ground zero for violent crime in Toronto. In response, the ward’s councillors worked tirelessly to improve conditions for local homeowners and transients alike, often in conjunction with neighbourhood associations. Some of the resulting initiatives were the official designation of the area span‐ning Yonge to Sherbourne and Queen to Carlton as the Garden District in 2001 and the installation on Sherbourne Street of one of the city’s first dedicated bike lanes around the same time.

More immediate to 290 Sherbourne, familiar structures began giving way to vacant lots: the gas station across the street was razed in 2002 and in 2005 three derelict Victorian houses at 294, 296 and 298 Sherbourne were demolished.

Amidst all this change, Ford has remained rooted at the house and is now the longest owner in its existence. Equally remarkable is that as of his retirement in 2019, 290 Sherbourne is once again a single‐family residence, a classification that virtually every other surviving historic house in the area hasn’t claimed for over a century.

OPPOSITE: Top Left: The front room with its oddly off‐balance half‐size window.

Right: By October 1980 the renovations were nearly com‐plete. The rear of first floor had been extended and the original brick exterior had been re‐stored in dramatic contrast to the neighbouring semi. Bottom Left: The front room today. The original half‐height win‐dow has been expanded to harmonize with the larger bay windows. (All photos courtesy of Tim Ford)

BELOW: 296‐298 Sherbourne was demolished in 2005 along with number 294 to the south. The lots remain vacant but a plan to develop them was finally submitted to the city in 2021. (Architectural Conserv‐ancy Ontario)

While this status is naturally subject to change in the future, the structure’s inherent existence is not. In October 2021 the city designat‐ed the local area as the Garden District Heritage Conservation District with 290 and 292 Sherbourne officially listed as two of its “contributing properties”. This means that the “physical form, scale and architectural features” of Joseph’s Thompson’s 1887 semi‐detached houses are to be protected and conserved, ensuring that many more chapters are yet to be written in their storied histories.

○ Ontario Land Registry abstracts, parcel registers and subdivision maps, 1811‐present

○ Goad’s Fire Insurance Plan of the City of Toronto, various editions 1880‐1964

○ Goad’s Atlas of the City of Toronto, various editions 1884‐1924

○ Toronto tax assessment rolls, 1845‐1920

○ Toronto city directories, 1840‐1970

○ Federal censuses, 1861‐1921

○ The Globe and Mail digital archives, 1844‐2018

○ Toronto Star digital archives, 1892‐2019

○ Toronto Archives historical photo collections

○ Toronto Reference Library historical photo collections

○ Ancestry.com family trees and genealogical records

○ Garden District Heritage Conservation District Plan by Toronto City Planning Department. 2021.

○ Handbook of Toronto. George P. Ure, A Member of the Press. 1858.

○ History of Sherbourne Street, A. Ernest Edmondson. 1994.

○ “Remembering the Sherbourne Streetcar (1874‐1942)” James Bow and Pete Coulman. Transit Toronto blog post accessed December 2022.

○ “Sherbourne: Toronto’s ‘City in One Street’” Mary Ormsby. Toronto Star November 29, 2009

○ “Simcoe’s Gentry”. Ontario Genealogical Society, Toronto Branch web site. Accessed December 2022.

○ Toronto Architecture: A City Guide. Patricia McHugh and Alex Bozikovic. Third Edition, 2017.

○ Toronto Past and Present: A Handbook of the City. Charles Pelham Mulvany. 1884.