SOUTH HILL

When Upper Canada’s first Lieutenant Governor, John Simcoe, decided in 1793 that an abandoned outpost known as Toronto should become the colony’s future capital he needed to entice the province’s fledging ar‐istocracy to relocate there. His solution: offer prominent officials 200‐acre lots in the surrounding Township of York. Some of the most desirable lands sat atop the escarpment on the north side of Davenport Road as their views of the town and lake made them ideal seats for country estates. With access offered by some of the earliest roads in the township (Avenue, Poplar Plains and Davenport) the area became home to palatial manors such as Spadina (1818), Russell Hill (1818), Rathnelly (1851), Glenedyth (replaced Russell Hill in 1872), Benvenuto (1888), Ardwold (1911) and Casa Loma (1914).

As the area developed, its component neighbourhoods opted to take advantage of the better municipal services offered by the city. Toronto’s northern boundary had been fixed at Bloor Street since the time of its incorporation in 1834 but it began to edge further north with the 1883 annexation of Yorkville. Other piecemeal annexations followed until the entire escarpment fell within city limits by the time Sir John Eaton moved into his Ardwold estate.

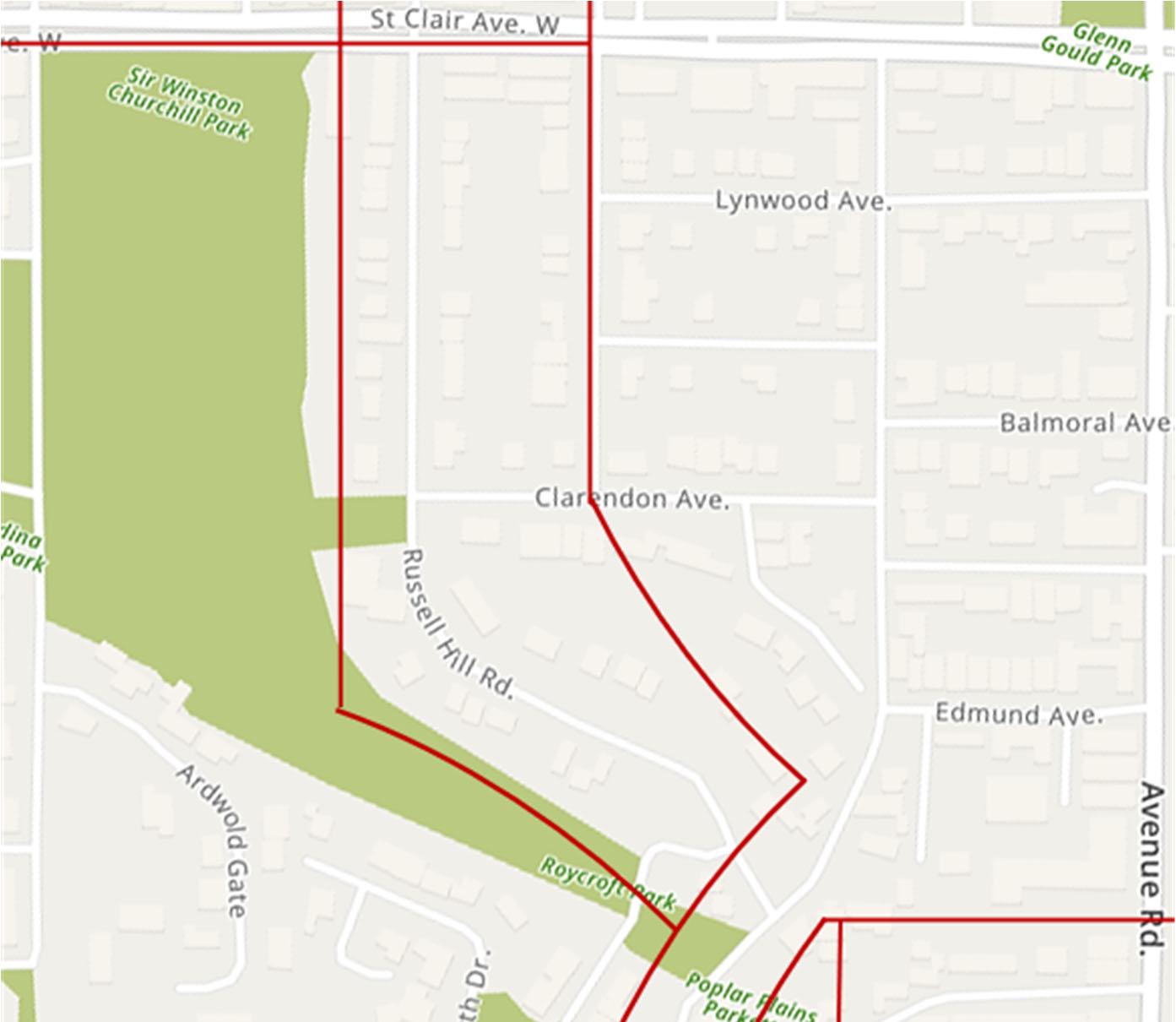

Following annexation, established place names such as Wychwood Park, Forest Hill and Deer Park remained in use but the area bounded by these three localities continued to lack a distinctive identity. By the 1950s even historic neighbourhood names had fallen out of use among Torontoni‐ans. It was not until the 1980s that old names were resurrected and new ones invented, primarily by real estate agents employing them as a market‐ing tool. One of those new labels was South Hill, presumably named for its location at the southern edge of the escarpment. The area’s boundaries were formalized in 1997’s Your Guide to Toronto Neighbourhoods as being from Spadina Road to Avenue Road and St. Clair Avenue to roughly Poplar Plains Crescent. In 2001 the city issued its own official neighbourhood designations which incorporated the district under the wider Casa Loma umbrella. However, the South Hill moniker remained, reinforced by the 2009 addition of Toronto neighbourhood profiles to Wikipedia based primarily on the Guide. A notable variation was the online profile’s exten‐sion of the neighbourhood’s southern boundary to the CPR tracks.

Today the neighbourhood’s old estates have long been subdivided and most of the manors demolished. However, their titles live on in local street names and their prestige still extends to the homes that replaced them.

2

Senator William McMaster’s Rathnelly in 1897. (Toronto Public Library)

Samuel Nordheimer’s Glenedyth aka Glen Edyth. (100 Years of Grandeur)

Real estate developer Simeon H. Jane’s Benvenuto in 1910. (Toronto Archives)

Sir John and Lady Eaton’s Ardwold. (Toronto Public Library)

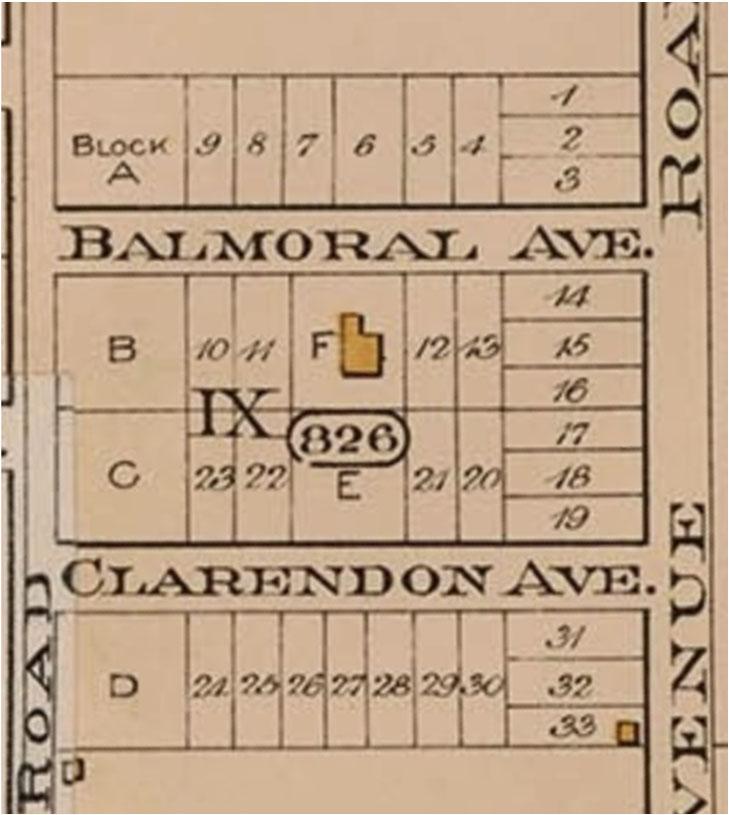

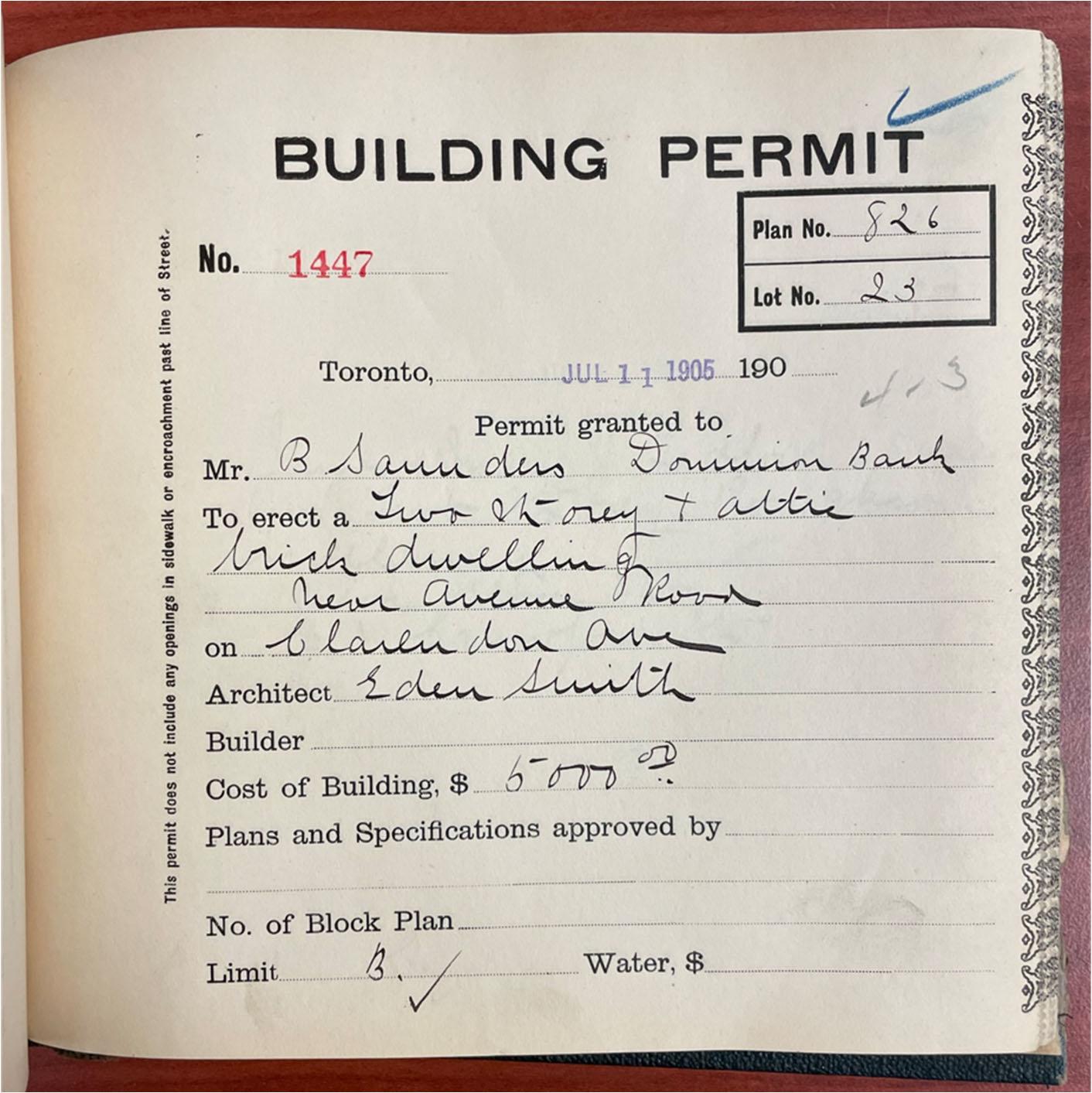

BERNARD DALY SAUNDERS

At the dawn of 1905, thirty‐three‐year‐old bank manager Bernard Daly Saunders and his wife Beatrice had just returned to Toronto with their three ‐year‐old son Thomas after briefly living in Winnipeg. While residing on upper Sherbourne Street they sought out a more tranquil alternative to what had previously been one of the city’s most prestigious neighbourhoods. They found it perched atop the Avenue Road hill where Bernard’s brother Dyce had recently purchased a vacant lot at the corner of Clarendon Avenue and Poplar Plains Road. In February 1905, Bernard acquired a 65‐foot by 135 ‐foot plot next door for $1,250. Both men commissioned architect Eden Smith to design their houses, and work on Bernard’s $5,000 residence began in July.

By the following year the family had settled into their new home at 16 Clarendon Avenue. Bernard continued to build his successful career at the Bloor and Dovercourt branch of the Dominion Bank while Beatrice tended to their growing family. Their second son, Guy, arrived in 1908 and their daughter Annette was born at the house in 1909. The Saunders moved out in 1913, selling the home to Bernard’s Dominion Bank colleague John Wedd who would live there with his own family until 1946.

After briefly residing on Collier Street, the Saunders purchased the Woodlawn estate in Deer Park in 1920 and spent many years restoring the

4

RIGHT: Bernard Saunders and his brothers in 1909. Bernard is on the left. Eldest sibling and next‐door neighbour Dyce is seated second from the right. (Wellington County Museum and Archives PH 16855)

BELOW: Beatrice Saunders and newborn son Thomas in 1901. (Wellington County Museum and Archives PH 16348)

1840 manor. During this time Beatrice also became known as a gifted singer and accomplished painter.

Bernard died at Woodlawn in 1953 and Emma followed in 1957 at which point their son Guy carried on the restoration of what is now the second oldest continually inhabited home in the city.

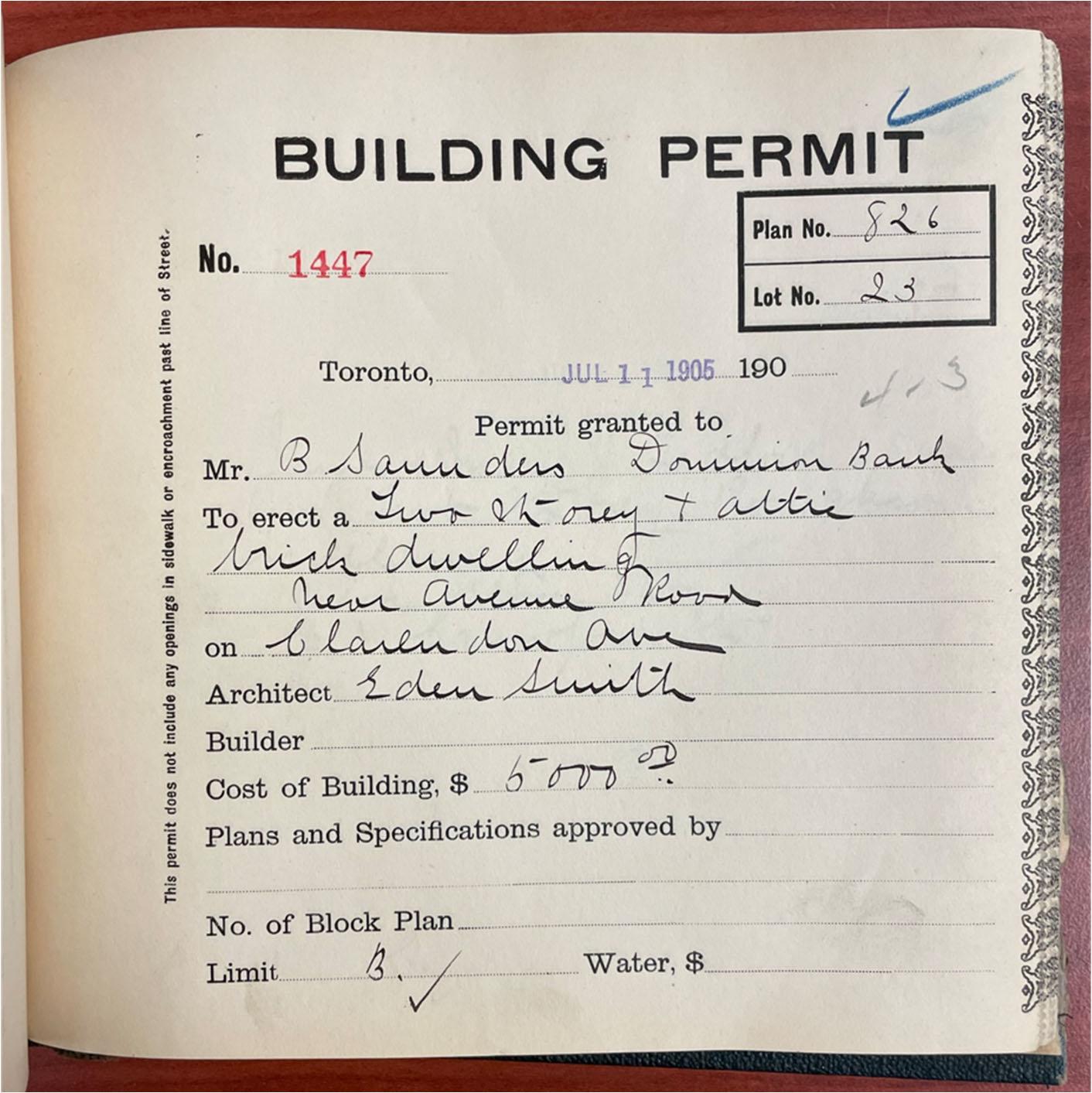

TOP LEFT: The original building permit stub for 16 Clarendon Ave. identifies the property by its legal designation as Lot no. 23 in subdivision Plan no. 826 as seen below. In actual fact, it also initially included the western 15 feet of Lot 22. (Toronto Archives)

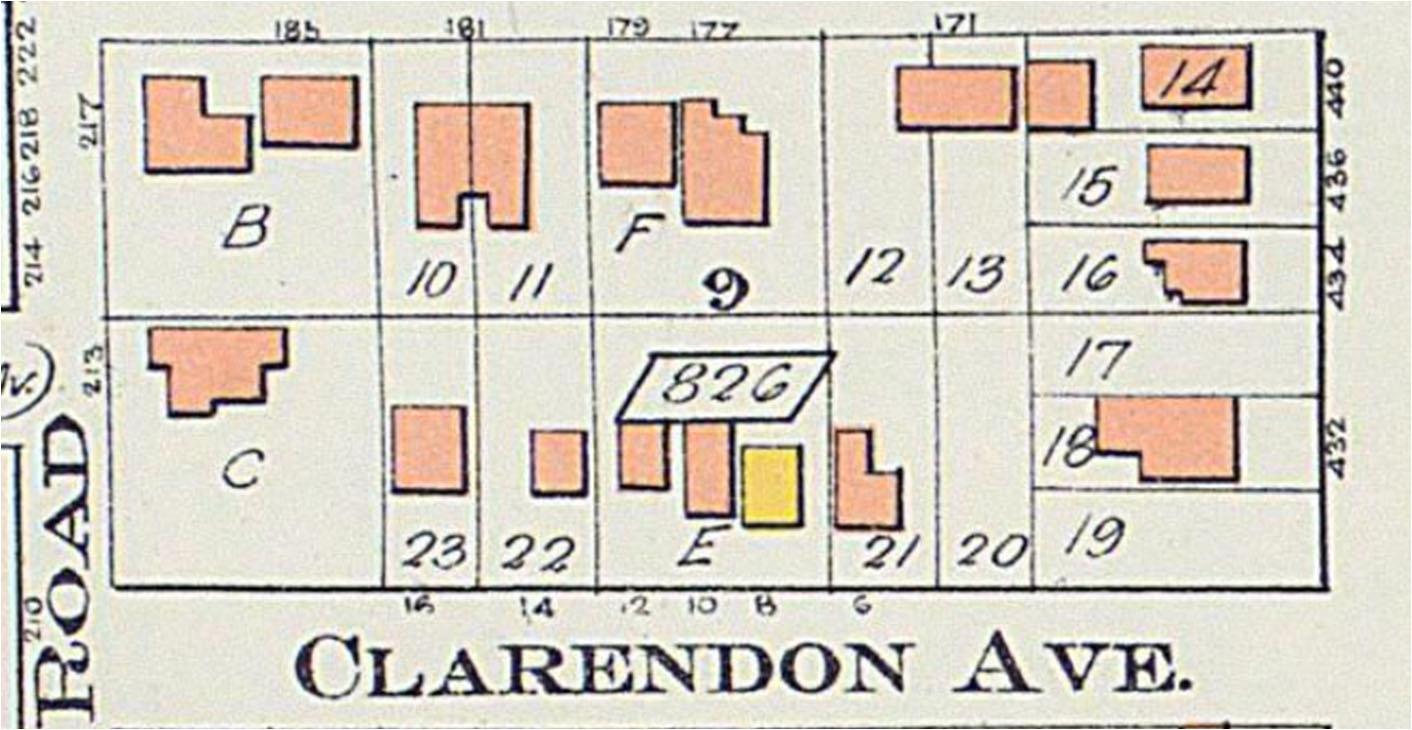

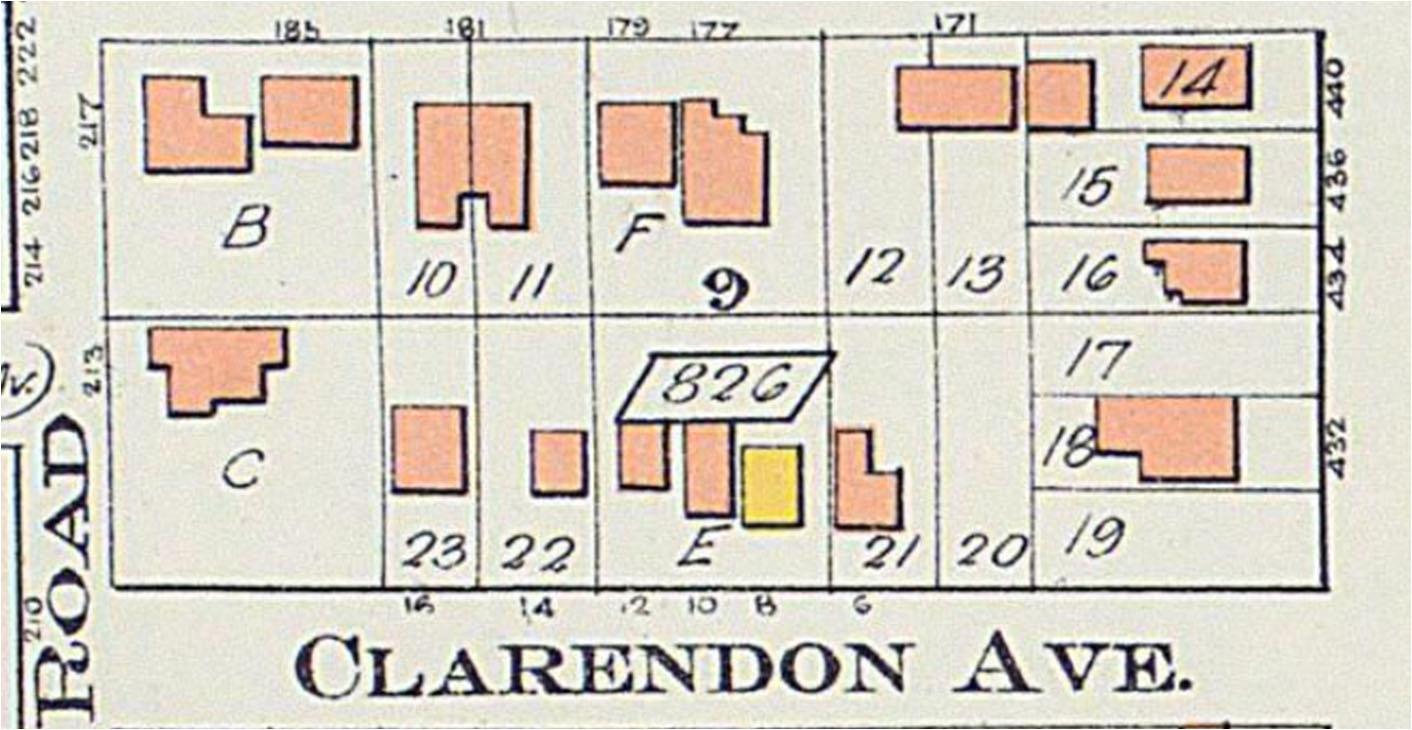

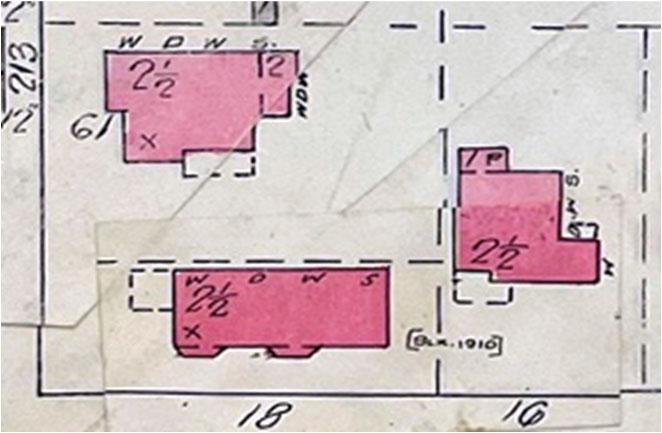

BOTTOM LEFT: Charles E. Goad’s 1910 Atlas of the City of Toronto showing the newly built 16 Clarendon in lot 23 as well as Dyce Saunders’s 213 Poplar Plains house in Block C.

5

ARTS AND CRAFTS STYLE

The prevailing architectural styles in early nineteenth century England and, by extension, Canada were revivals of Classical and Gothic principles, typically with extensive ornamentation. At the same time, construction materials were increasingly mass produced in newly emerging factories. By the mid 1800s this type of derivative styling, sentimental decoration and crass commercialization had come under criticism by a group of English artists and architects who advocated instead for a return to medieval values when master craftsmen put in honest work to create honest works.

By the 1880s this philosophy had been coined the Arts and Crafts movement and embraced both the decorative arts and architecture. Its proponents rejected the practice of imposing an arbitrary style on a house to make it fit a pre‐conceived notion of respectability and instead argued that a home should be designed “from the inside out” so that its function dictated its form. A characteristic example of this was the positioning of rooms to take advantage of the warmth and light of the sun even if that meant placing the main entrance at the side of the house. The movement’s architects found inspiration in the manor houses, farmhouses and cottages of rural England, manifested in distinctive half‐timbering — a wooden framework whose gaps are filled with stucco — steeply pitched roofs, tall chimneys, and bands of small‐paneled casement windows.

This new aesthetic was exported to Canada in the 1890s where it was often referred to as English Domestic Revival or English Cottage Style. Whatever the name, one thing is certain: its undisputed champion was architect Eden Smith.

EDEN SMITH

Born in Birmingham in 1859, Smith worked with his father’s building company then joined an architectural office at the age of seventeen while taking evening classes at the Birmingham Architectural Association. It was here that he most likely came in contact with leading thinkers of the nascent Arts and Crafts movement which was centered in the city.

In 1881 Smith married Ann Charlton and four years later they immi‐grated to Canada. By late 1887 he was employed as a draftsman in Toronto. He completed his apprenticeship in 1890 and the following year began his own practice.

6

Eden Smith’s first home on Indian Road in High Park. (William Morris Society of Canada)

Eden Smith in undated photo. (Canadian Encyclopedia)

Smith is believed to be the first architect to introduce the Arts and Crafts Movement to Toronto — and possibly the country — as a response to the existing standards of Canadian architecture which he derisively referred to as “jerry built” and “cheap and nasty.” The home he built for himself in High Park in 1896 would set the benchmark for the new era.

The distinctly British nature of the English Cottage style was a natural draw for Edwardian Toronto’s landed gentry. Consequently, the design became prevalent in pastoral upper‐class WASP enclaves such as High Park, Wychwood Park, Forest Hill and Casa Loma. At that time, neighbourhoods were typically developed in a piecemeal fashion by multiple small builders. The houses were either constructed on speculation for rent or sale, or were custom made for wealthy clients. The majority of Smith’s houses were the latter.

Smith designed fifteen houses in the South Hill area alone, beginning with the homes of Bernard and Dyce Saunders in 1905. They are both visible in the 1915 photo below, flanking 18 Clarendon Ave. which Group of Seven artist Lawren Harris commissioned from Smith in 1912 after purchasing the southern portion of Dyce’s corner lot.

In all, Smith would design more than 250 structures in Toronto by the time he retired in the mid 1920s. Many of them, including the Dyce Saun‐ders house, have since been demolished making the remainder a priceless part of the city’s built heritage.

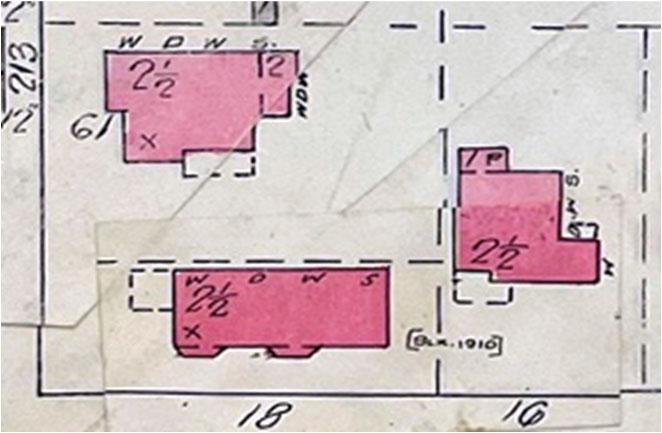

ABOVE: Charles E. Goad’s 1914 Insurance Plan of the City of Toronto volume 5 showing detailed outlines of the original Eden Smith houses at 16 and 18 Clarendon Ave. and 213 Poplar Plains Rd. Numbers within the outlines indicate amount of storeys and dashed extensions represent porches.

BELOW: 18 Clarendon Ave. flanked by 213 Poplar Plain Rd. on the left and 16 Clarendon Ave. on the right. (Contractor magazine, July 1915)

7

SELECTED SOURCES

Ontario Land Registry records

Goad’s Insurance Plan of the City of Toronto, various editions 1880‐1964

Goad’s Atlas of the City of Toronto, various editions 1884‐1924

Toronto tax assessment rolls

Toronto city directories

Canada censuses, 1911‐1931

The Globe and Mail digital archives

Toronto Star digital archives

Toronto Archives

Toronto Reference Library Baldwin Collection of Canadiana Ancestry.com genealogical records

“

Arts and Crafts” at ontarioarchitecure.com. Accessed July 2023.

Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800‐1950. dictionaryofarchitectsincana‐da.org. Accessed July 2023.

Eden Smith: Toronto’s Arts and Crafts Architect W. Douglas Brown, 2003.

Lost Rivers historic house profiles at lostrivers.ca. Accessed July 2023..

Lost Toronto. Doug Taylor, 2018.

The Estates of Old Toronto. Liz Lundell, 1997.

Toronto Architecture: A City Guide. Patricia McHugh and Alex Bozikovic, 2017.

Your Guide to Toronto Neighbourhoods. David Dunkleman, 1999.

8

10