依麗莎伯.列翁絲卡雅 鋼琴演奏會

Elisabeth Leonskaja Piano Recital

除特別註明,所有照片

Unless otherwise specified, all photographs © Jean Mayerat

演奏家介紹 Biography

曲目 Programme

樂曲介紹 Programme Notes

舒曼

Robert Schumann

蝴蝶,作品 2

Papillons, Op 2

布拉姆斯

Johannes Brahms

六首鋼琴小品,作品 118

Six Piano Pieces, Op 118

四首鋼琴小品,作品 119

Four Piano Pieces, Op 119

舒伯特

Franz Schubert

降 B 大調鋼琴奏鳴曲, D960

Piano Sonata in B flat major, D960

特稿 Feature

再逢列翁絲卡雅

The Emotional Art of Elisabeth Leonskaja

2.3.2006

香港文化中心音樂廳 Concert Hall

Hong Kong Cultural Centre

節目長約1 小時45 分鐘,包括一節 20 分鐘中場休息

Running time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes with a 20 minute interval

6 10 12 15 18 20

為了讓大家對這次演出留下美好印象,請切記在節目開始前關掉手錶、無㵟電話及傳呼 機的響鬧裝置。會場內請勿擅自攝影、錄音或錄影,亦不可飲食和吸煙 ,多謝合作。

To make this performance a pleasant experience for the artists and other members of the audience, PLEASE switch off your alarm watches, MOBILE PHONES and PAGERS. Eating and drinking, unauthorised photography and audio or video recording are forbidden in the auditorium. Thank you for your co-operation.

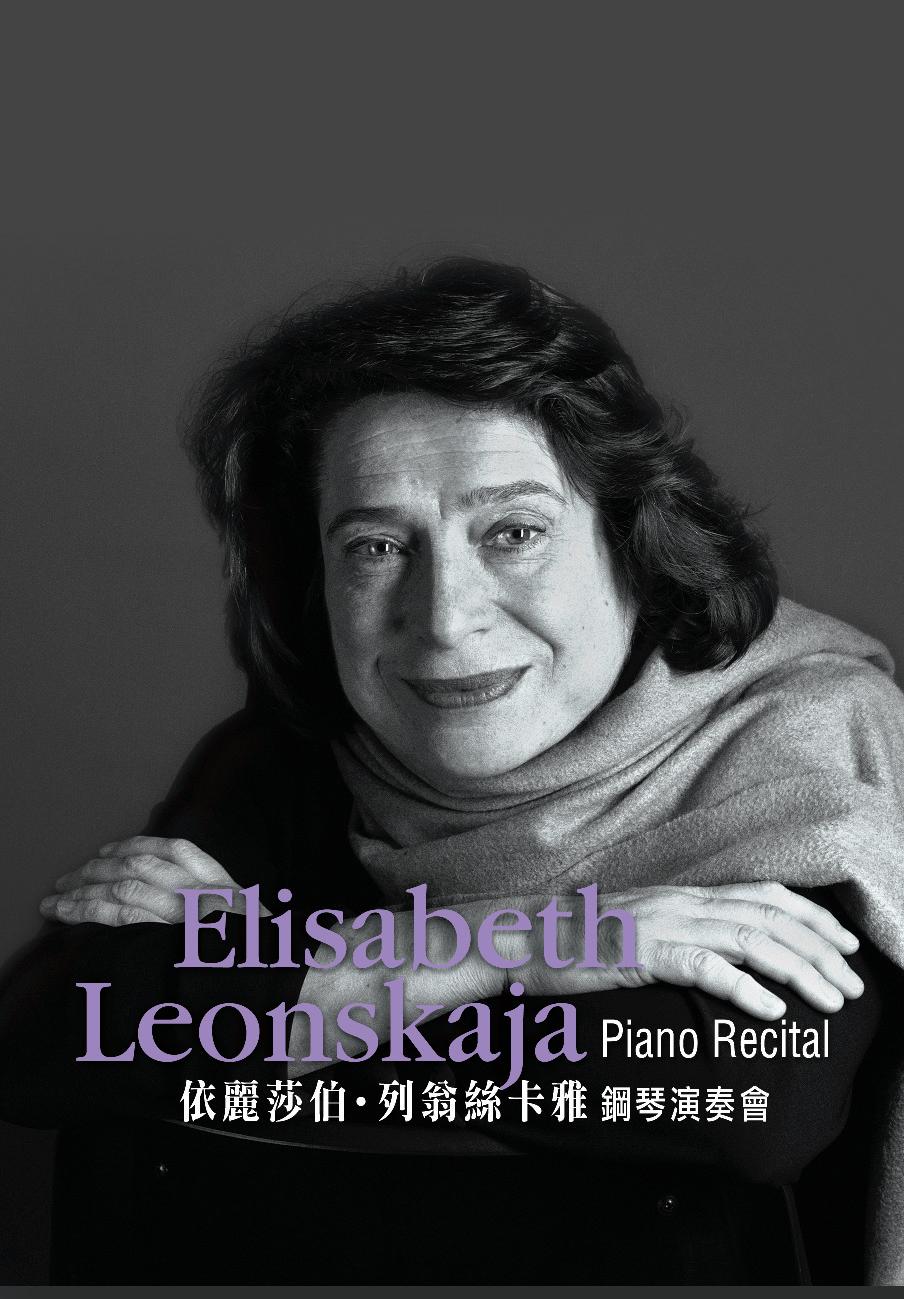

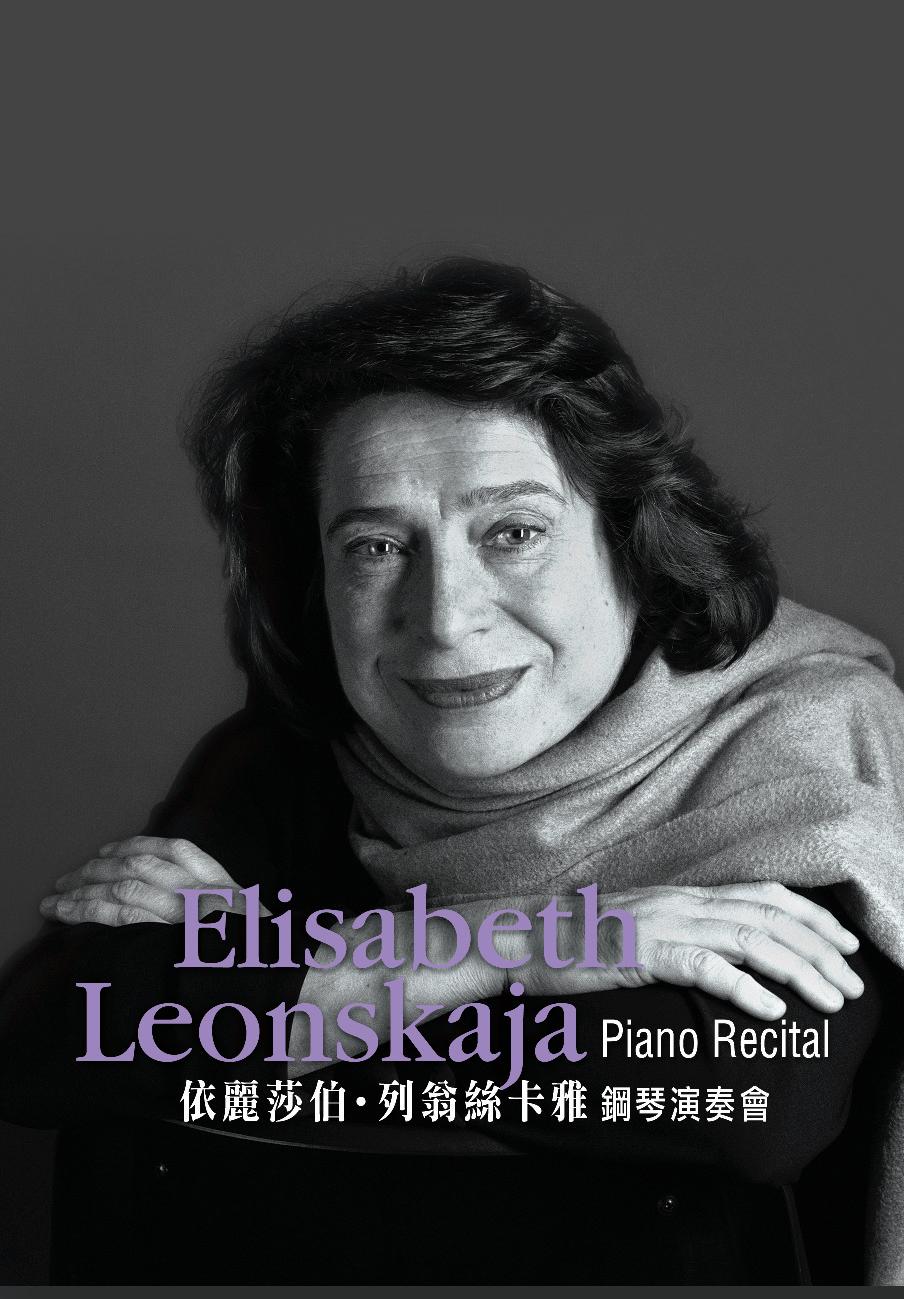

麗莎伯.列翁絲卡雅在世界芸 芸頂尖鋼琴家當中佔着特殊的 位置。生於前蘇聯格魯吉亞, 列翁絲卡雅於莫斯科音樂學院師從米 爾斯坦。 1978 年由前蘇聯移居維也納 之前,她已贏得多個重要的鋼琴比 賽,包括羅馬尼亞的恩尼斯高鋼琴大 賽、法國瑪格麗特.隆音樂大賽、及 比利時依麗莎伯女王音樂大賽;她的 演出無數,當中與李赫特的合作,對

Elisabeth Leonskaja holds a distinguished position among the leading international pianists. Of Russian origin, she studied under Jacob Milstein at the Moscow Conservatory, and won the prestigious Enesco, Marguerite Long and Queen Elizabeth Competitions before emigrating from the former Soviet Union and settling in Vienna in 1978. She had also given many concerts, which included duets with Sviatoslav Richter in a partnership that had a profound influence on her subsequent

她後來的藝術事業發展起了深遠的影 響,然而,是她在 1979 年首次於薩爾 茨堡藝術節的精采演出,使她在西方 音樂界聲名大噪。

自此以後,她在無數國際音樂節中演 出,並經常受邀在世界知名的音樂廳 演出。在最近和未來的幾個樂季况, 她將參與愛丁堡、維也納、石勒斯維 格- 霍爾斯坦等地的藝術節,並會在倫 敦、巴黎、布魯塞爾和柏林的國際鋼 琴系列中亮相。在 2002/03 年的樂 季,列翁絲卡雅在雄偉的、新的多蒙 特音樂廳擔當留駐藝術家。

列翁絲卡雅經常在歐洲作巡迴獨奏演 出,與多位一流的指揮家合作,如馬 素爾、艾申巴哈、楊頌斯、泰米卡諾 夫等,最近合作的樂團有柏林愛樂樂 團、維也納交響樂團、慕尼克愛樂樂 團、蘇黎世音樂廳管弦樂團、倫敦愛 樂樂團、巴黎交響樂團以及捷克愛樂 樂團。

她與洛杉磯愛樂樂團在荷里活露天音 樂節的合作,是她首次踏足北美洲舞 台。隨之而來的邀約包括克里夫蘭交 響樂團和紐約愛樂樂團。樂評人一致 認為她的演出洋溢暖意、優雅、風格 精緻,帶來出神入化的演奏。

列翁絲卡雅熱中室樂,和她合作緊密 的室樂團有貝爾格、鮑羅丁和寡奈里 四重奏,還有大提琴家希夫和維也納 愛樂室樂團; 2004 年,維也納音樂廳 特別主辦了一系列鋼琴五重奏音樂 會,讓她與傑出的弦樂四重奏合作 演出。

她灌錄的多張唱片取得不少國際重要 獎項,例如她的布拉姆斯鋼琴奏鳴曲 唱片就獲得比利時的凱西利亞獎;而 她的李斯特作品專輯則替她拿到唱片 界夢寐以求的法國金音叉唱片獎。

development as an artist. However it was her sensational debut at the 1979 Salzburg Festival that rapidly brought her name to the attention of western audiences.

Since then she has given countless recitals at numerous international music festivals and is a frequent guest in some of the world’s most prestigious concert halls. Recent and future seasons have and will include appearances at the Edinburgh, Vienna, Schleswig-Holstein Festivals as well as the International Piano Series’ in London, Paris, Brussels and Berlin. During the 2002/03 season Leonskaja was the Artist-in-Residence at the magnificent new Dortmund Konzerthaus.

She regularly appears as a soloist across Europe and works with many of the leading conductors such as Kurt Masur, Christoph Eschenbach, Mariss Jansons, Yuri Temirkanov and many others. Among the orchestras with whom she has performed recently are the Berlin Philharmonic, the Vienna Symphony, the Munich Philharmonic, the Zurich Tonhalle, the London Philharmonic, the Orchestre de Paris and the Czech Philharmonic. Her North American debut with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl Festival was followed by invitations to appear with the Cleveland Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic and other American orchestras. Critics agree that warmth, stylishness and elegance distinguish her virtuoso playing.

A committed chamber musician, Leonskaja collaborates closely with the Alban Berg, the Borodin and Guarneri Quartets as well as Heinrich Schiff and the Vienna Philharmonic Chamber Ensemble. Last year the Vienna Konzerthaus presented her in a series of concerts featuring piano quintets with some of the world’s greatest string quartet players.

Her recordings have received a number of prestigious international prizes including the Caecilia Prize for her recording of Brahms’ piano sonatas and the coveted Diapason d’Or for her recording of works by Franz Liszt.

舒曼 (1810-1856)

蝴蝶,作品 2

序曲

急板

華貴的

活潑的快板

如歌的小快板

極快板

樸素的 生氣勃勃的快板

急板

速度轉慢

充滿活力的快板 終曲;快板

布拉姆斯 (1833-1897)

六首鋼琴小品,作品 118

A 小調間奏曲

A 大調間奏曲

G 小調敘事曲

F 小調間奏曲

F 大調浪漫曲

降 E 小調間奏曲

四首鋼琴小品,作品 119

B 小調間奏曲

E 小調間奏曲

C 大調間奏曲

降 E 大調狂想曲

- 中場休息 -

舒伯特 (1797-1828)

降 B 大調鋼琴奏鳴曲, D960

有節制的中板

稍慢的行板

諧謔曲;活潑及柔和的快板 不太快的快板

加料節目

3.3.2006(五)下午2:00-6:00

大師班香港演藝學院演奏廳 主持:依麗莎伯.列翁絲卡雅 德語講授,英、粵語翻譯 詳情可參閱「藝術節加料節目」小冊子或瀏覽藝術節網站 www.hk.artsfestival.org

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Papillons, Op 2

Introduzione

Presto

Pomposo

Allegro vivace

Allegretto cantabile

Allegro molto

Semplice

Allegro con brio

Presto

Meno mosso

Allegro con spirito

Finale. Allegro

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Six Piano Pieces, Op 118

Intermezzo in A minor

Intermezzo in A major

Ballade in G minor

Intermezzo in F minor

Romance in F major

Intermezzo in E flat minor

Four Piano Pieces, Op 119

Intermezzo in B minor

Intermezzo in E minor

Intermezzo in C major

Rhapsody in E flat major

– Interval –

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Piano Sonata in B flat major, D960

Molto moderato

Andante sostenuto

Scherzo. Allegro vivace con delicatezza

Allegro ma non troppo

Festival Plus

3.3.2006 (Fri)2:00-6:00pm

MasterclassRecital Hall, Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts

Instructor: Elisabeth Leonskaja

Conducted in German with English and Cantonese interpretation For details, please refer to Festival Plus booklet, or visit th e Festival website www.hk.artsfestival.org

舒曼在 1832 年 4 月從萊比錫寄出一封家書,在信况請各人「盡快去 看尚保羅的《少不更事的年頭》的終章,因為《蝴蝶》會是這場化裝舞 會的音樂演繹。」他所指的是尚保羅.里希特寫於 1804 年的小說况 的高潮,場景是懺悔星期二的化裝舞會。這一章題為「面具舞會」 (在法文中,「面具」一詞語帶雙關,亦作「幼蟲」解),替舒曼提供了 多層意義

以音樂描述由幼蟲到蝴蝶的蛻變,同時象徵着小說 幾個主人翁的轉變。

《蝴蝶》中的部份章節是舒曼較早期的創作,結構鬆散,大致上以 D 大調為本調重心,再配以重複出現的動機,但是經常轉變的本調重 心及豐富的旋律素材,令早期的聽眾甚感迷惑。序曲以齊奏段開 始,代表布幕徐徐升起,又或是一雙情侶高雅地走進舞池,然後跳 着優美的圓舞。晚會中,一首首舞曲層疊而過;接着的短小的〈急 板〉,好像清理舞池,迎接一位自視甚高,似乎很有份量的紳士到 來一樣。〈華貴的〉旋律先在左手以八度奏出,然後是右手,樂思稍 稍得到發展之後,新的舞曲又開始了。每一樂章都與前者對比鮮 明:旋動的〈活潑的快板〉後是細緻的〈如歌的小快板〉,緊隨着〈樸 素的〉是〈生氣勃勃的快板〉,最後〈華貴的〉樂調回到舞池飛快的轉 了一圈,隨着夜愈深,對比愈加強烈,終於我們聽到熟悉的調子 《祖父之舞》 一支舞會傳統上最後的樂曲。在這樂譜的末段, 舒曼寫着:「舞會由喧鬧漸歸平靜」,而「鐘樓報來清晨六時。」

後來,有些人乾脆把《少不更事的年頭》當作樂曲的內容,舒曼對此 不以為然,曾辯說他「以文本襯托音樂,不是反過來以音樂作襯 托」。他的音樂與這本書的關係顯然複雜得多;《蝴蝶》雖然只是一 小型作品,但卻是舒曼創作路上的一個重要里程碑,在往後的十 年,他把文學糅進更大型的音樂創作,而在《狂歡節》(1834) 及《大 衛同盟舞曲》(1837) 中,「化裝舞會」更再三成為虛擬的場景。

Robert Schumann

Papillons, Op 2

In a letter to his family, written from Leipzig in April 1832, Robert Schumann asked that everyone “read the last scene in Jean Paul’s Flegeljahre as soon as possible, because the Papillons is intended as a musical representation of that masquerade”. He was referring to the climactic scene of Jean Paul Richter’s Fledgling Years (1804), set at a Shrove Tuesday masquerade ball. This ‘Larven-Tanz’ chapter provides Schumann with several layers of meaning, with the metamorphosis from larva to butterfly (papillon) symbolic of the transformation of the novel’s main characters, now depicted through music.

Schumann had completed Papillons partly from pieces composed much earlier. Unified only loosely by an overall tonal centre of D major and recurring motifs, the constantly shifting tonal centres and wide array of melodic material bewildered many early listeners. The introduction begins with a unison passage that suggests a rising curtain, or perhaps a couple walking gracefully onto the dance floor, followed by a delicate waltz. With ‘the evening’ underway, the individual dances cascade past. A brief Presto clears the floor for what seems to be a heavy gentleman who takes himself very seriously.

We hear this Pomposo melody first in the left hand in octaves, then in the right. The ideas are developed a bit and then a new dance begins. Each piece is set in vivid contrast to the one that precedes it: a swirling Allegro vivace then a delicate Allegro cantabile , Semplice followed by an Allegro con brio . Eventually Pomposo returns to the dance floor for a quick turn. Contrasts grow more pronounced as the night wears on, and finally we hear the familiar tune of the Grossvatertanz, or Grandfather Dance, the customary final number. At this point in the score, Schumann noted “The noise of the carnival dies away” and “The tower clock strikes six”.

In response to those who where looking to Die Flegeljahre for a simple programme Schumann soon became uneasy, writing that he had “underlaid the text to the music and not the reverse”. The relationship between his music and the book is certainly more complex and the slender proportions of Papillons belies the work’s importance as a starting point for Schumann, who would go on to blend literary and musical traditions in even greater works throughout the decade, and use the masked ball as the figurative setting in both Carnaval (1834), and the Davidsbündlertänze (1837).

布拉姆斯

六首鋼琴小品,作品 118

四首鋼琴小品,作品 119

1850 年代初,藉着舒曼的幫助,布拉姆斯得以首次發表作品,奠 定日後成為專業作曲家的基礎;四十年後,被一致認為真正繼承了 貝多芬和舒伯特的布拉姆斯,卻打算結束他自小開創的事業。 1890 年 12

月,在與出版商西姆洛克的通信中,布拉姆斯宣告他的 五重奏,作品 111 ,將會是他封筆之作。奮鬥多年,他想休息一 下,但不久就發現他還有一些工作需要跟進;在 1892 到 1893 年 間,布拉姆斯重拾他最愛的樂器,編寫了一系列鋼琴小品:作品 116 到 119 。

1893 年夏季,布拉姆斯在度假小鎮巴德伊舍完成最後兩組作品, 分別是《六首鋼琴小品》,作品 118 和《四首鋼琴小品》,作品 119 。

對於作品的創作歷程,後世所知不多,但有證據顯示,當中一些樂 章可能在多年前已寫成,他只是把這些舊作拼合修飾。

一如布拉姆斯其他晚期作品,這些樂曲基本上是無言歌;在作品76 (1879) 和 116 中,布拉姆斯交替運用嚴肅的間奏曲和輕鬆的隨想 曲,頗有舒曼 1830 年代作品的風格,但到了作品 118 和 119 ,他卻 棄用隨想曲:在作品 118 的四首間奏曲况,加插一首敘事曲和一首 浪漫曲;而作品 119 則是在三首間奏曲之後,以一首延綿的狂想曲 作結,平衡了前面樂曲的氣氛。這十個樂章况包含了布拉姆斯成熟 風格的所有元素,不管是內斂或是嚴肅的作品,全都樸實無華,旋 律常隱藏在內聲部,有部分甚至晦暗不明,例如作品 119/1 。

以十九世紀晚期的標準來看,他的和聲可算保守,偏好三度和弦; 在作品 118/1 ,他把 A 小調的中央調性抑壓着,直到末段,然後以 第二樂章輓歌體的間奏曲主調 A 大調終結。大多數樂章都是分明的 三段式; G 小調敘事曲的兩端豪放大膽,與溫婉的中段形成強烈對 比; F 小調間奏曲也有相似的結構;作品 118 的終章間奏曲,濃濃 的憂鬱揮之不去,而熱情的中段,可稍稍舒緩這個終結樂章的沉重 氣氛。

即使布拉姆斯把這些作品視為一個年邁音樂家個人的、最後的陳 述,作品寫成後卻很快獲得賞識。在送交出版商之前,布拉姆斯先 把樂譜交給年老的克拉娜.舒曼過目,她後來為布拉姆斯演奏作品 118 中的幾段,那是1895 年,也是兩人最後一次見面。舒曼的學生 艾彬舒姿於 1894 年在倫敦演奏作品 118 及 119 ,獲英國樂評人一致 讚許;在維也納,荀伯格視這些晚期作品為表現主義的先驅,因為 在作品况可聽到作曲家的心聲,訴說着人生的遺憾和渴望。

Johannes Brahms

Six Piano Pieces, Op 118

Four Piano Pieces, Op 119

It had been with Robert Schumann’s help in the early 1850s that Johannes Brahms secured his first publications, thereby establishing himself as a professional composer. Forty years later and now widely regarded as the true successor of Beethoven and Schubert, Brahms was preparing to close what he had begun as a young man. In December 1890, he wrote to his publisher, Simrock, notifying him that with his Op 111 Quintet he would be retiring After many years of hard work he wanted to relax, but soon found that he still had some tidying up to do. Between 1892 and 1893 he returned to his preferred instrument, producing four collections of short piano pieces, Opuses 116-119.

Brahms completed the final two sets, the Six Piano Pieces, Op 118 and Four Piano Pieces, Op 119, in the summer of 1893 at the resort town of Bad Ischl. He left few clues to his compositional processes, but there is evidence that some of these pieces may have dated from years earlier and that he may have been occupied mostly with assembling them into collections and rounding them off.

As in other late works, they are all essentially songs without words. However, whereas in Op 76 (1879) and Op 116 Brahms alternated the more serious intermezzo with the lighter capriccio, much in the manner of Schumann’s works of the 1830s, in these two sets he dispenses with the capriccio

To the four Intermezzos of Op 118 he adds a Ballade and a Romance, and following the three Intermezzos of Op 119 he ends with a single, expansive Rhapsody that balances all that precedes it. All the elements of his mature style are present in these ten pieces. Whether subdued or serious, they contain little outward display. Melodies are often placed in the inner voices and sometimes even obscured, as in Op 119, No 1.

His harmonies are conservative by the standards of the late 19th century. He favours relationships of a third. In Op 118, No 1 he withholds the central tonality of A minor until nearly the very end, and then closes on A major, the key of the elegiac Intermezzo No 2. Most of the pieces are in clear, ABA forms. The bold outer sections of the Ballade in G minor are sharply contrasted with the more tender middle section. The Intermezzo in F minor is similarly constructed. In the final Intermezzo of Op 118, a passionate middle section provides respite from an otherwise unrelentingly sombre conclusion to the set.

If Brahms viewed these works as the private, final statements of an aging musician it did not prevent others from appreciating them soon after they were completed. Before submitting them to his publisher he sent copies to the elderly Clara Schumann, who played for Brahms from the Op 118 at their last meeting, in 1895. Schumann’s student Ilona Eibenschütz played the pieces in London in 1894, where they were well received by English music critics. In Vienna, Arnold Schoenberg looked on these late works as precursors of expressionism, hearing in them intensely personal utterances of regret and longing.

– Interval –

雖然舒伯特早以多產見稱,但在他短暫人生的最後一年,作品的質 與量仍然叫人驚訝,當中很多更有極高的原創性。在 1827 到 1828 年的這些作品中,我們找到他惟一完整的鋼琴三重奏、僅有的弦樂 五重奏、室樂幻想曲、一套鋼琴即興曲,以及最後三首鋼琴奏鳴曲 (D958 、 D959 和 D960) 。舒伯特畢生探索鋼琴奏鳴曲的創作,這 幾首遺作是一個令人滿意的總結;他的奏鳴曲大都沒有引起聽眾的 注意,直到二十世紀才有知音人去發掘這個寶藏。最後幾首鋼琴奏 鳴曲對舒伯特極具個人意義,把它們寫好成為他當務之急,而樂曲 的草稿在較早時已完成,當時他一股勁兒加以整理,在 1828 年9 月 完成全部三首作品,兩個月後他就離開人世。

這幾首鋼琴奏鳴曲極受舒伯特剛完成的聯篇歌曲《冬之旅》所影響; 《冬之旅》以穆勒的二十四首詩為藍本,描述一個孤單的浪人怎樣渴 望死亡,這正是一個引起舒伯特強烈共鳴的題材,他選擇過孤獨的 生活,自從 1822 年染上梅毒後,他就自知活不長久。一如在《冬之 旅》中,舒伯特在奏鳴曲况運用了微妙的循環結構,把四個樂章的 素材聯繫起來。

這些細微的關係加強了作品的連貫性,並平衡了舒伯特一些創新的 寫法和不協和的效果。他喜歡把對比的素材並置,就像降 B 大調鋼 琴奏鳴曲的第一樂章,寧靜的、和音穩定的第一主題群以一串使人 不安的降 G 低音顫音結尾;這樣的編排在一降 G 樂段中重複,然後 音樂利落地回到降 B 大段,突然一躍,第二主題群在相隔更遠的升 F 小調奏出。

第二樂章整體音質渾厚而內斂,調性是遠處的升 C 小調,這個安排 在第一樂章的發展部已經有所預示。諧謔曲的音質輕鬆愉快,它把 我們帶回降 B 大調。總結的迴旋曲,氣氛較前兩個奏鳴曲的終曲都 來得輕鬆,中和了第一和第二樂章的感傷。

樂曲介紹:拜恩.湯臣 場刊中譯:黃家慧

Franz Schubert

Piano Sonata in B flat major, D960

Even by his own prolific standards, in the final year of his short life Franz Schubert produced an astounding number of fine works, many of them of stunning originality. Among these 1827-1828 works, one finds his only complete piano trios, his only string quintet, his only chamber fantasies, a set of piano impromptus, and his last three piano sonatas (D958, D959 and D960).

Schubert’s final piano sonatas provided a satisfying conclusion to a genre he had explored throughout his life. Most of his sonatas would be forgotten, and await rediscovery in the 20th century. The final sonatas are among Schubert’s most personal works, and their completion was especially urgent for him. Having previously sketched the broad outlines of the sonatas, and now working at a furious pace, he completed all three in September 1828, just two months before his death.

The influence of Schubert’s recently completed song cycle Winterreise hangs heavily over these final sonatas. Based on 24 poems by Wilhelm Müller, Winterreise tells a wanderer’s story of loneliness and longing for death. It was a subject that resonated very strongly for Schubert, who had chosen a solitary life and since 1822 lived with the expectation of an early death after contracting syphilis. In the sonata, as in Winterreise, Schubert makes use of a subtle cyclical organisation, linking material in each of the f our movements.

These often imperceptible relationships bring continuity and balance some of Schubert’s harmonic adventures and jarring effects. He favours the odd juxtaposition of contrasting materials, as in the first movement of the B flat sonata, where the serene and harmonically stable first theme group ends with a menacing low trill on G flat. The process is repeated with an excursion into the second key area (G flat), followed by a clear return to B flat, and then an abrupt jump into the more remote key of F sharp minor for the second theme group.

The overall tone of the second movement is profound and subdued. Its remote key of C sharp minor is foreshadowed in the development section of the first movement. The tone of the Scherzo is light and buoyant. It returns us to B flat major. The concluding Rondo is lighter in mood than the finales of the two preceding sonatas, and provides a counterbalance to the pathos of the first two movements.

Programme Notes by Brian C Thompson

再逢列翁絲卡雅

文:李名強

麗沙伯.列翁絲卡雅是俄羅斯中年 一代鋼琴家中非常突出的一位。

1945 年 11 月 23 日出生,她於前蘇 聯加盟共和國格魯吉亞的首都第比利斯成 長。 1959 年 14 歲時畢業於第比利斯七年制 音樂學校後,進入扎哈里亞.柏里亞什維 里音樂學院跟羅約克教授學習。就是在那 個時候我第一次知道她的名字。 1964 年參 加羅馬尼亞第三屆恩尼斯高國際鋼琴比賽 的時候,她才 18 歲。性格開放,演奏男性 化,她演奏的李斯特梅菲斯托圓舞曲,普 羅科菲耶夫第二奏鳴曲和拉赫曼尼洛夫第 二鋼琴協奏曲充滿青年人的朝氣和衝擊 力,雖然不夠成熟,但是效果鮮明而刺 激,結果得了第一名。

後來她去了莫斯科音樂學院跟雅科夫.米 爾斯坦教授深造。米爾斯坦是伊戈姆洛夫 的學生,後來做了伊戈姆洛夫的助教。伊 戈姆洛夫去世後,他的另一個弟子,著名 鋼琴家阿什肯納齊的老師奧波林,也繼承 了他的位子,成了莫斯科音樂學院鋼琴系 四個教研室主任之一。米爾斯坦就是這個 教研室的一員大將。他是當時蘇聯鋼琴家 中極少數擁有博士銜的教授,學問淵博, 治學嚴謹,曾負責編過蘇聯出版的李斯 特、斯克里亞賓、布拉姆斯和舒伯特的鋼 琴作品。他的教學顯然對列翁絲卡雅後來 的發展產生了影響。

另一個對她的演奏產生影響的是鋼琴大師 李赫特。李赫特對後來蘇聯一批年輕的音 樂家,不光是鋼琴家如加夫列洛夫,列翁 絲卡雅和維沙拉澤,也包括小提琴家如卡 崗和大提琴家如古特曼。通過和他們一起 演奏,在嚴肅和忠實於原作的精神方面對

他們留下了很深的影響,而這一方面正是 老的俄羅斯學派不夠重視的地方。

1978 年列翁絲卡雅離開蘇聯移民去了維也 納,這對她擴大和拓展曲目,深入研究和 演奏維也納經典學派的作品肯定也有影 響。她這次獨奏會演奏的全是德奧學派的 作品:舒曼的《蝴蝶》作品2 ,布拉姆斯作品

118 和 119 的鋼琴小品和舒伯特的降 B 大調 最後一首鋼琴奏鳴曲 D960 ;這很像是一張 當年李赫特的節目單。我沒有聽過她演奏 的舒曼和布拉姆斯,但她近年大量演奏舒 伯特。她的舒伯特除保留了她原有大膽、 明朗的風格外,對舒伯特後期作品的哲理 性有了更深刻的理解,對舒伯特結構上的 層次感也表現得十分細緻,自然而得體, 音色變化多端,極富樂隊的交響性。

闊別四十餘年,我十分高興她將第一次來 香港演出,我期待着欣賞一個面目全新的 列翁絲卡雅!

The Emotional Art of Elisabeth Leonskaja

by Robert Turnbull

When critics refer to pianist Elisabeth Leonskaja as ‘distinguished’, the impression conveyed is of an establishment figure resting comfortably on her laurels. In fact she is anything but that.

Leonskaja can enrapture, mesmerise, fascinate, even confound and irritate if the mood takes her. By harnessing a formidable technique and the gift of generosity, she creates live performances that are both personal and individually memorable.

Leonskaja’s preferred repertory is romantic, pride of place given to the masterpieces of Brahms, Schumann, Chopin and Liszt. Brahms’ last compositions for the piano are among his most intimate expressions. The 1879 Opuses 118 and 119, alternately gentle and vigorous, are written with a concentration and intensity lacking in his previous piano pieces.

The other composer with whom she has a special affinity is Schubert. For Leonskaja, Schubert’s late great sonatas might lack “the dramatic pathos of Beethoven at his best”, but are as outstanding for their melodic power and melancholy mood. “Schubert’s music has a particular poetical expression which is not easy to render,”

she says. “The length and melodic lines, especially in the late sonatas, cause some difficulty and require a certain sensibility and style. But the overwhelming problem is knowing how to find the balance between what are, on the one hand, symphonic poems of almost Brucknerian vastness with music moving in a unique poetical world. Schubert talks above all about intimacy.”

Awareness of these essential contrasts is very much at the root of Leonskaja’s musical thinking. However her style, the element that marks her out from many of her contemporaries, is the courage to play with emotion, to add the crucial dimension of feeling surprisingly absent in much of today’s music making.

She is also a master of surprise and the enemy of predictability. Whereas one pianist might observe the classical and balanced structure of a piece, Leonskaja will stress its romantic and rhapsodic qualities with flamboyancy and panache; or rush headlong into the piece like some Florida-bound hurricane. As Michael Tumelty in The Herald wrote of her 2004 Edinburgh Festival recital, “her incredible lightness at some moments was offset by powerhouse thunder at others, her sense of repose by the rage and fury, rather than mere drama at yet others. If the word mercurial did not exist it would have to be invented for this remarkable musician.”