Front Cover:

Gordon Coates, complete with white shirt, tie and hat, sorting full wool sheep in a pen at Ruatuna in about 1904.

Above: The Ruatuna stencil used to identify bales of wool.

All photographs are from the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga collection.

©Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga

ISBN 978-1-877563-61-4 (print)

ISBN 978-1-877563-62-1 (online)

heritage.org.nz | visitheritage.co.nz

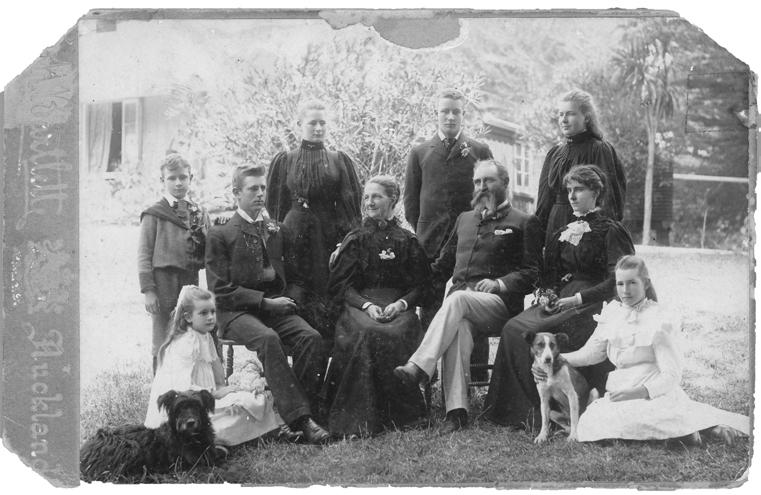

Nau mai haere mai, welcome to Ruatuna, the boyhood home of our first elected New Zealand-born Prime Minister, Gordon Coates.

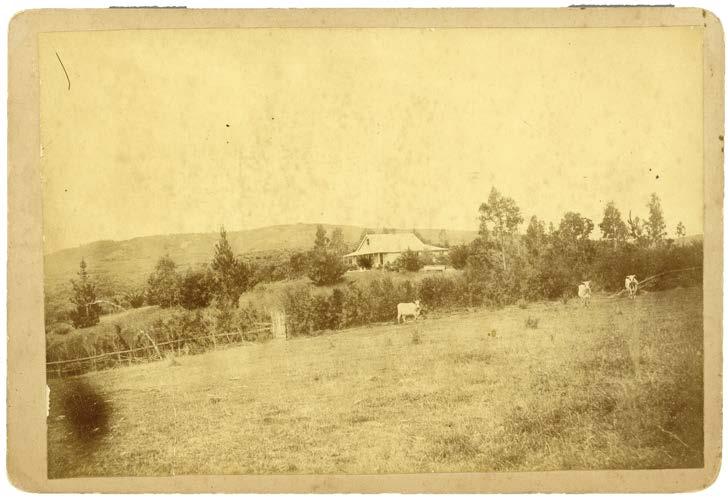

Built in 1877 from locally sourced kauri, Ruatuna was the home of the prominent Coates family and part of their extensive estate in the northern Kaipara.

Ruatuna – which means ‘two eels’ – was a social and economic hub for the tight-knit community, including Māori, farmers, farm workers and other landowners. It was also a centre for agricultural innovation – including the first Shropshire Down sheep brought into Aotearoa New Zealand, along with the first Hereford cattle to arrive in the North Island.

Ruatuna is a Category 1 historic place, a classification that identifies it as a place of outstanding national heritage significance.

Ruatuna was left to the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (now Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga) in 1976, with the organisation purchasing additional farmland associated with the house in 1997.

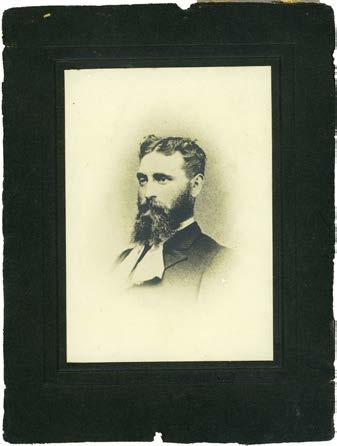

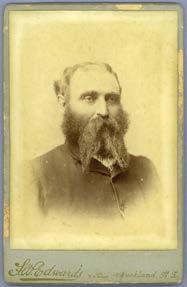

In 1866, Edward and Thomas Coates arrived in Auckland on board the Winterthur. The two were younger sons of an established Herefordshire gentry family, and were unable to inherit land in England. Instead, the brothers sought their fortune in New Zealand.

Edward and Thomas headed north to the Kaipara, and after some investigations found a 2500 acre block of land on the Hukatere Peninsula known as the Unuwhao block. A family friend had already established himself at nearby Mangawhai, and agreed to act as agent and buy the Unuwhao land, with funds supplied by the brothers’ wealthy brother-in-law.

The Coates brothers then took possession as tenant farmers. In 1871, a further 10,410 acres (called the Hukatere Block) was leased from local Māori. Edward built his family homestead (Ruatuna) on this land and when the lease lapsed some years later, he purchased a 294 acre piece surrounding the homestead.

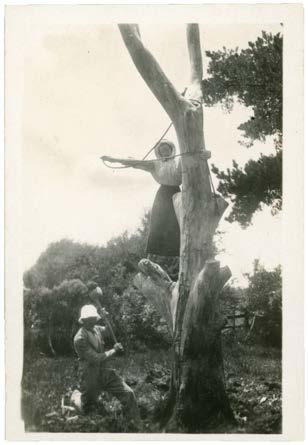

Ever the English gentlemen, Edward and Thomas were known to do physical work on the farm dressed in white shirts and ties – at times even working by hurricane lamp at night – as they worked to transform the scrub and bush into farmland.

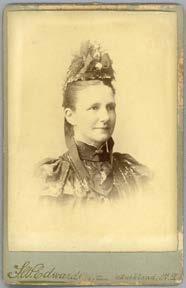

Named after the nearby creek, Ruatuna Homestead was constructed in 1877 by local builder Samuel Cooksey. The house was built in preparation for Edward Coates’ marriage to Eleanor Aickin that year.

The building fused the symmetry of early colonial architecture with elements of the newer Gothic Revival style – including prominent central gables at the front and rear, as well as a front parlour that was open to the roof. Family tradition suggests that the front room was modelled on a Scottish hunting lodge that Edward had visited. A talented singer, Edward liked the acoustics of the high ceiling.

Edward and Eleanor went on to have a large family. Their eldest son Gordon played a significant part in New Zealand’s political history.

Gordon and his six siblings experienced an almost idyllic childhood growing up at Ruatuna, spending their spare time riding horses, catching eels in the tidal inlets and punting on the river. He also learned to round up cattle and handle a gun, frequently bagging pheasants, ducks and even wild pigs to provide food for the family.

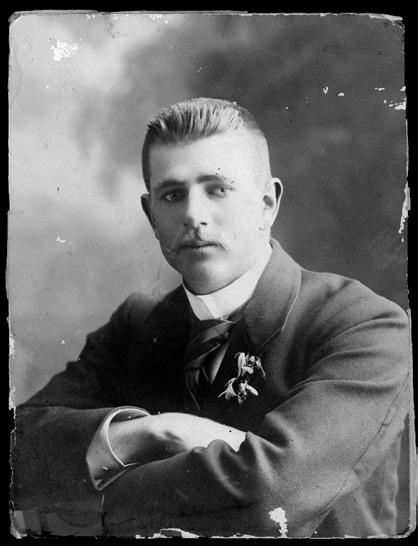

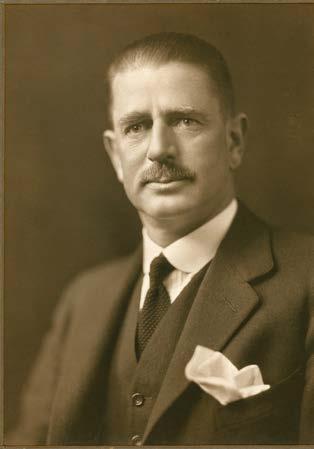

Tall and athletic, things didn’t always go his way. An early riding accident left him with an unusual gait whenever he walked, and a kick from a horse disfigured his upper lip – though this was covered in later years with a moustache.

Although family life was generally happy, things began to deteriorate when his father’s manic depression grew worse during the 1890s, eventually leading to his admission into an Auckland mental institution.

By the time he was in his early twenties, Gordon found himself running the farm in partnership with his younger brother Rodney.

Despite the challenges, it wasn’t long before Gordon’s natural leadership abilities came to the fore, and he began assuming community responsibilities as his father had done a generation earlier.

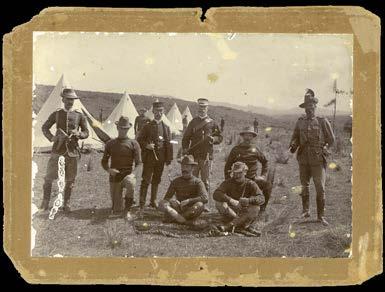

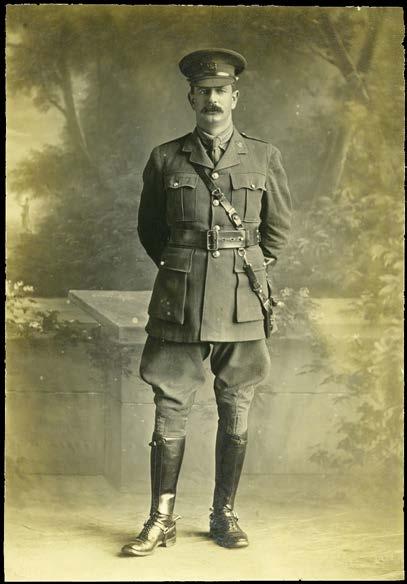

In 1900, he joined the Ōtamatea Mounted Rifles – one of many local volunteer military groups around the country formed as a result of patriotic fervour generated by the South African War. Coates rapidly became its leader. He also commanded B Squadron of the 11th Mounted Rifles between 1911 and 1912. Coates was also becoming a local political force. In November 1905, he was elected to the Ōtamatea County Council and from 1913 to 1916 served as its Chairman, gaining administrative skills and experience in local government. In 1911, he was elected Kaipara’s Member of Parliament (MP), standing as an independent Liberal.

Coates agreed to support the Prime Minister Sir Joseph Ward, though his support was conditional. When Ward faced a vote of no confidence in February 1912, he voted with the Liberals, enabling them to hold office by a slender majority. Another confidence vote later that year – this time against the Liberals – saw Coates voting for William Massey’s Reform Party whose support of freehold land tenure reflected his own views.

Never a ‘party man’, Coates was always guided by practical solutions to problems rather than political ideology. He nevertheless became the Reform Party’s official candidate in Kaipara in 1914.

On 4 August 1914 – the day World War I broke out – Gordon Coates married Marjorie Grace Coles in Wellington. It was the beginning of a successful and mutually supportive marriage partnership that was to last until his death 29 years later.

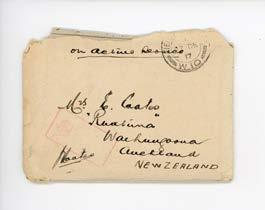

With Gordon’s time and focus increasingly spent on the demands of his role as an MP in Wellington, he had less time to visit Ruatuna, though the farm was ably managed by his brother Rodney assisted by his sister Ada. While in Parliament he drew no income from the farm.

Given his own military experience with the Ōtamatea Mounted Rifles, Coates had been transferred to the Reserve of Officers with the rank of Captain in 1912. His almost in-bred sense of patriotism made him desperately keen to serve overseas.

Coates enlisted soon after the war was declared and also took part in recruitment campaigns. However, Prime Minister William Massey – whose majority in the House was minimal and who needed every vote – refused to release him for military service. He was therefore unable to leave for the war until November 1916.

Ada Coates was the last child of Edward and Eleanor Coates to live at Ruatuna.

A skilled and accomplished agriculturist, Ada farmed Ruatuna ably assisted by her niece Joy Aickin who joined her there in 1948. Ada died in 1976, leaving the house to the then New Zealand Historic Places Trust. Joy retired in 1996 and sold the Ruatuna farmland to the Historic Places Trust the year after though she continued to live in the house until her death in 2000.

In March 1917, Gordon Coates was posted as Second in Command of the 15th (North Auckland) Company of the 1st Battalion of the Auckland Infantry Regiment in France. It wasn’t long before his rose-tinted views of war would be tempered by the harsh reality of trench life.

Liked and respected by the men he led, Coates fought at Ypres, and on 31 July 1917 won a Military Cross for his action at La Basseville.

He was then transferred to the Somme and was promoted to Company Commander of the 3rd (Auckland) Company of the 1st Battalion. It was during the battle at Mailly-Maillet that Coates won a bar to his Military Cross on 26 March 1918.

A leg injury suffered in that battle resulted in several months of recuperation during which time he was permitted to visit his relatives in Herefordshire.

Coates was promoted to Major, and was subsequently involved in the final incursions into Germany in late 1918. After the Armistice, he left for home on the Remuera in March 1919, receiving a hero’s welcome when he arrived in the Kaipara two months later.

Still an elected MP, and even though he had been serving overseas, Coates was promoted to Minister of Justice, Postmaster General and Minister of Telegraphs in September that year. He then became a Junior Minister at the age of 41.

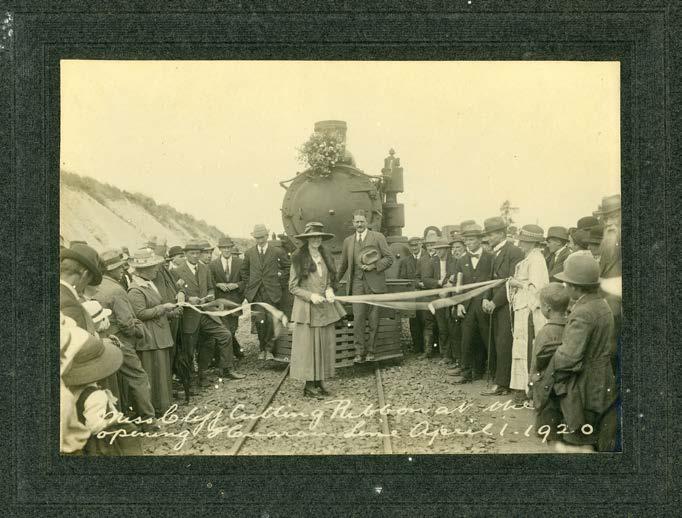

Coates was re-elected easily in December 1919 and was made Minister of Public Works in March 1920 and Minister of Railways in 1923.

Falling export prices made for challenging economic times, but Coates still managed to produce impressive results within his areas of responsibility, earning a reputation for being a person who got things done.

Coates completed the three main trunk lines – the Midland, East Coast and North Auckland lines – based on sound business principles rather than local political interests which had influenced railway development prior to that.

He also centralised the construction of hydroelectric dams and progressed plans for projects on the Waikato and Waitaki rivers.

Faced with the increasing number of cars in New Zealand – 30,000 by the end of World War I – Coates turned his attention to roading. Eighteen highway districts created under the Main Highways Act 1922 designated highways that were then funded centrally through taxes on tyres, motor vehicle registration and fuel.

Coates also maintained his connection with working New Zealanders. He was known to drop by at construction sites on occasion and share a drink and a chat with workers, and was widely regarded as an effective and hard-working Minister.

Between 1921 and 1928, Gordon Coates served as Native Minister and established strong relationships with prominent Māori leaders of the day, including Apirana Ngata and Princess Te Puea Hērangi.

Quoted in Hansard in 1928, Coates declared that Māori were “one of New Zealand’s great assets, and a poetic asset at that”. Certainly as Native Minister he attempted to tackle issues affecting Māori more sympathetically than his predecessor Sir William Herries, who maintained that Māori should either use their land or lose it.

Coates reversed Herries’ land acquisiton policy and scaled down the land purchase section of the Native Department. Instead he supported title reform and instructed the Māori Trustee to lend only to Māori farmers so that Māori could make better use of their own land.

Coates also set up a commission to investigate the confiscation of Māori land after the wars of the 1860s, though its recommendations were conservative.

In 1926, a Māori Arts and Crafts Bill was introduced, and the School of Māori Arts was established in Rotorua the following year. Coates felt strongly that Māori arts and crafts should be displayed with pride in public buildings.

Coates was generally regarded by Māori at the time as being one of the most understanding Ministers to have held the Native Affairs portfolio.

The Coates family’s connection to Māoridom ran deep, beginning with the close relationship that Edward Coates had built with Māori when he first arrived in the Kaipara. The Coates family always retained close links with the local marae, providing meat for tangihanga and other occasions.

Gordon was cared for by a Māori nanny from the age of one, and when he was older he could speak some Māori, though he understood a lot more. Later, during World War II, he was known to perform haka at the request of American soldiers stationed here.

Coates’ fourth daughter was given the name Irirangi (‘Beautiful angel’ or ‘Voice from the heavens’), possibly from Ngāti Porou. Irirangi, who in later years worked in the New Zealand Embassy in the United States, said that her name was the best gift she ever received as it broke the ice on many occasions and opened up many conversations.

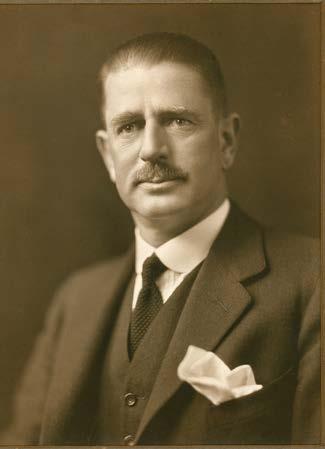

By 1925, Gordon Coates’ reputation as a charismatic, effective Minister preceded him and he was regarded by many as the natural successor to Prime Minister William Massey, whose health was failing.

With his war record, reputation for achievement and generally impressive appearance, Coates won a ballot in the Reform Party caucus. On 30 May 1925, he succeeded Sir Francis Bell, the temporary fill-in for Massey who had died earlier that month.

1925 was also an election year, and a few months after becoming Prime Minister Coates was on the road campaigning to keep his new job. The mastermind behind the Reform Party campaign was Bert Davy, who used the latest techniques from the commercial advertising industry to develop an American-style presidential campaign.

Labour politician John A. Lee recalled the impact of the campaign:

“We had the Prime Minister’s photo coming to us in the morning news, in the evening news, wrapped around sausages, wrapped around fish. The Reform Party advertised the Prime Minister much in the same way that an advertising agency would peddle pills, soap, corn-cure or backache plaster”.

The campaign worked. The Reform Party – with Coates at the helm – won by a landslide. Lee described him as New Zealand’s “Jazz Premier”.

Expectatons were high when Coates was elected Prime Minister – though the times were against him. A depressed British economy meant prices for New Zealand’s farm produce fell in 1926.

The New Zealand Dairy Produce Control Board attempted to fix the price of butter on the British market to help boost farmers’ incomes, though it ultimately failed. The government was forced to convince the Board to desist, deferring the hopes of farmers until the British market improved. Coates copped the blame.

Coates introduced family allowances for families with three or more children in 1926 – though this progressive welfare policy only alienated his government from the Reform Party’s conservative constituency.

Other unpopular measures and factors beyond his direct control resulted in Coates’ government being humiliated in the 1928 general election. He was then demoted to Leader of the Opposition.

When it came to managing his own money, Gordon Coates was generous to a fault.

Widely known as a soft touch, if anyone asked him for help – particularly an exsoldier with a hard-luck story – Coates would immediately empty his pockets for them. Raised to be generous by his mother Eleanor, he was perhaps inclined to overdo it.

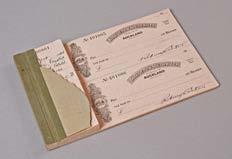

Gordon was generally undisciplined with finances – so much so that when he was working with his brother, Rodney had to countersign cheques made out by him. However, Rodney – who was more savvy in financial matters – had the freedom to write cheques using just his own signature.

In the early 1930s, Coates influenced the Reform Party towards forming an alliance with the other non-Labour Party, the United Party. In September 1931, a coalition government between Reform and United was formed; the coalition of the two parties was the beginning of today’s National Party.

Coates’ portfolios in the coalition government included Public Works, Transport and Employment, though the timing couldn’t have been worse with the effects of the Great Depression continuing to bite.

With unemployment reaching 80,000 in September 1933, Coates advocated for public works expenditure to be reduced, and resources invested instead to fund people made redundant into purchasing farms to boost national productivity. Minister of Finance, Downie Stewart, rejected his request for money to carry out his plan.

Coates also pushed for the devaluation of New Zealand’s currency to boost farmers’ incomes – initially unsuccessfully, though eventually Cabinet accepted his positon. Downie Stewart then resigned and Coates became Minister of Finance.

In his new role Coates advocated strongly for farmers including his Small Farms (Relief of Unemployment) Bill in 1933, and by starting the Mortgage Corporation

of New Zealand in 1935 to help farmers refinance loans at lower interest rates. He also passed the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bill establishing a central bank. Despite his practical fiscal measures, and some signs of economic recovery, the coalition suffered a huge defeat in the November 1935 election.

When the coalition government lost the 1935 election, Coates was no longer a Minister. In addition to losing his position, he also lost his income and his home (until then he and his family had lived in ministerial accommodation).

Besides a small bach at Bayley’s Beach, Gordon Coates did not own a family home. Never wealthy, he was now financially stretched.

A fundraising function held in Dargaville by a group of Coates’ supporters and well-wishers raised £500, enabling Gordon and Marjorie to buy a modest cottage and relocate it onto the Unuwhao block farmed by Gordon and Rodney. The house became his family home, and was directly funded by the people he had served for many years – such was his standing in the community.

Coates at the Imperial Conference of 1926 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oaZ30_Br040

After the loss in 1935, Gordon Coates moved his family back to the Unuwhao block in the Kaipara, and re-established his sheep and cattle breeding partnership with his brother Rodney.

Although he kept a lower profile, Coates was still in demand as a speaker – and he had his fair share of supporters who believed he was the best man suited to lead the new National Party. Coates represented the political past, however, and the National Party caucus was keen to present new faces.

Coates’ time wasn’t over. Following the outbreak of World War II in 1939, he offered his services to the government. Knowing his capacity for hard work, and his effectiveness, Prime Minister Peter Fraser asked him to join the War Cabinet, commissioning him to look into all aspects of defence preparedness. Coates travelled the country in this role, pushing for an end to partisan politics.

On 30 June 1942, with New Zealand at war with Japan, Coates became Minister of Armed Forces and War Coordination. He continued to work closely with Fraser, earning the Prime Minister’s gratitude and friendship, though a breach had opened up between Coates and his own party.

A punishing schedule meant Coates had difficulty getting home to the Kaipara at weekends – a journey that involved taking the Express train to Auckand on a Friday evening, driving three hours to Matakohe on Saturday, and then returning to Wellington on Monday. Nevertheless he made the trip whenever he could.

Coates had been diagnosed with heart problems, and he collapsed and died in his Wellington office on 27 May 1943 aged 65.

Prime Minister Peter Fraser called him “a statesman of the front rank” who on the battlefield and elsewhere “proved himself to be of truest steel – a trusted counsellor, a true friend and comrade, and intrepid leader”.

Following his death in 1943, the Labour Government – after consultation with the family – chose to memorialise Gordon Coates by building a church in Matakohe paid for by the government with donations from the local community. Opened in 1950, it is the only church in Aotearoa New Zealand dedicated to a Prime Minister.

Another monument, the Coates Memorial, is located at the junction of State Highway 1 and the road to Matakohe – the site marks the exact spot where Coates always knew he’d made it home.

The Coates Memorial was erected by friends of Coates, and the words on the plaque reflect the respect with which he was held in the community:

"Takoto e pa i runga i au mahi nunui mo te Pakeha me te Maori – Rest thou, O father, upon the great work you have performed for Pakeha and Maori alike".

Film of Gordon

funeral Weekly Review No. 94 (1943) (Archives NZ) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUn6tazQEjk

Besides Ruatuna’s connection to our first elected New Zealand-born Prime Minister and the rural community that shaped his political views, it was also a centre for stock breeding and the introduction of new breeds of sheep and cattle. Ruatuna reflects changes in land ownership and land use in the northern Kaipara in the late colonial period, and also tells the story of an all-female household who farmed the land.

Ruatuna mirrors the development of rural New Zealand in what was then an isolated part of the country. Through Coates’ political career, it also reflects the values of rural pragmatism which, for a number of years in Aotearoa New Zealand’s development, were influential on government.

“Has very marked determination. Cheerful disposition. Absolutely reliable and conscientious. Plenty of balance. Very energetic. Tactful and Man of the World. Good appearance. Readily assimilates new ideas and imparts knowledge well. Has application, imagination and initiative ...” Report on Gordon Coates, Senior Officers’ School, Aldershot, 1918

Bibliography:

Michael Bassett. 'Coates, Joseph Gordon', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1996. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Michael Bassett. Coates of Kaipara, Auckland University Press, 1995. Ruatuna. The New Zealand Heritage List / Rārangi Kōrero. www.heritage.org.nz/list-details/7/Ruatuna

www.visitheritage.co.nz/visit/northland/ruatuna

heritage.org.nz | visitheritage.co.nz