SOUND FOUNDATIONS

A former dancehall now resonates with a different kind of music

A former dancehall now resonates with a different kind of music

From military strongholds to a community garden, a landscape shaped by many hands

A wartime hospital for soldiers has been given a new lease of life

The ancient stream flowing below Wellington’s streets

Tohu Whenua is your itinerary to history where it happened.

Explore now at tohuwhenua.nz

A chance childhood visit to a family friend sparked a lifelong love of New Zealand’s built heritage for Dame

From Māori pā and military strongholds to a prison garden, this landscape has been shaped by many hands

Building reconstructions at Lincoln University have seamlessly combined seismic engineering and traditional craftsmanship 28

An ancient stream below Wellington’s streets has now been recognised for its cultural and ancestral significance to Māori

Beneath Auckland’s Crystal Palace Theatre, a former dancehall now resonates with a different kind of music

A wartime hospital for soldiers has been given a new lease of life thanks to a dedicated community restoration

At an historic goldmining reserve in Central Otago, traces of the miners’ pursuits of fortune remain etched into the scarred landscape

A grand old Hawke’s Bay residence has become a guardian of local history, preserving the stories and records of the region

We’re always working to improve your membership experience — and there are some exciting changes ahead! These updates are designed to give you more choice, flexible pricing options, and a more streamlined experience. Many of you have been supporting us for the long term.

So another feature of our evolving membership programme will be a greater emphasis on acknowledging and rewarding your loyalty to our mission and work.

Expect to see this, and a more personalised experience as the changes are rolled out.

As we move more of our communication online and reduce the amount we send by post, it’s really important that we have your up-to-date email address and cell phone number.

If you haven’t already shared these with us, we’d love it if you did — and please let us know that you’re happy to hear from us this way.

And as always, we’re here to help. If you have questions or thoughts, don’t hesitate to get in touch.

Thank you for your continued support and for helping protect Aotearoa New Zealand’s heritage. Stay tuned for further exciting improvements to your membership experience.

Thank you / Ngā mihi

We are very grateful to those supporters who have recently made donations. Whilst some are kindly acknowledged below, many more have chosen to give anonymously.

Brenda Hannay and Graeme Macann

Mr Pieter Holl and Ms Felicity Cains

Ms Leonie Stieller and Mr Paul Aitken

Mrs Debra Stan-Barton and Mr Barry Barton

Mr Frank Bull

Mr Andrew and Mrs Bridget Read

Miss Karen Shepherd and

Mr David Tucker

Mr Cameron Moore

Mr Alan and Mrs Ann Jermaine

Mr Kevin Blue and

Mrs Marie Morton-Blue

Mr Ian and Mrs Jenny Thomas

Mrs Clare and Mr Mark Loeffen

Mr Malcolm Wade

Mr Mike and Mrs Rosalind Robertson

Mr Edward Ellison

Miss Gaye Matthews

Mrs Charline Baker

Mr David and Mrs Marilyn Ayers

Mr John and Mrs Angela Clark

Mr Paul and Mrs Patricia Mason

Mrs Velma Clarke

Mr Paul and Mrs Natalie Hickson

Mrs Patricia Taylor and Jo Taylor

Mr Erik and Mrs Rosanne Van Leeuwen

Mrs Catherine and Mr Edmund Brown

Mrs Ann McWilliam

Mrs Suzanne and Mr Wayne Morris

Mr Ray and Mrs Janet Ryan

Mr Wayne and Mrs Diana Hann

Mr Finlay Clements and Mrs Stephanie Muir

Mr Francis and Mrs Annette Piggin

Ms Sandra Mclachlan

Ms Elaine Hampton and Mr Michael Hartley

Ms Claire Martin

Mr Tony and Mrs Cath Morgan

Ms Alyth Grant

Miss Andrea Thomson

Mr Peter and Mrs Mary Fennessy

Mr Desly and Mrs Wendy Pearce

Mr Craig and Mrs Penny Hickson

Mr William and Mrs Jo Wilson

Mr Roger and Mrs Janice Reeves

Mr Michael Lloyd and Mr Hazel Nash

Ms Caroline and Mr Alan List

heritage.org.nz | visitheritage.co.nz

Issue 179 Raumati • Summer 2025

ISSN 1175-9615 (Print)

ISSN 2253-5330 (Online)

Cover image:

Te Motu Kairangi Miramar Peninsula by Mike Heydon

Editor Anna Dunlop, Sugar Bag Publishing

Sub-editor

Trish Heketa, Sugar Bag Publishing

Art director

Amanda Trayes, Sugar Bag Publishing

Publisher

Heritage New Zealand magazine is published by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. The magazine had a circulation of 8167 as at 30 September 2025.

The views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Advertising

For advertising enquiries, please contact Tony Leggett, Advertising Sales Manager. Phone: 027 474 6093

Email: tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Subscriptions/Membership

Heritage New Zealand magazine is sent to all members of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. Call 0800 802 010 to find out more.

At Heritage New Zealand magazine we enjoy feedback about any of the articles in this issue or heritage-related matters.

Email: The Editor at heritagenz@gmail.com

Post: The Editor, c/- Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140

Feature articles: Note that articles are usually commissioned, so please contact the Editor for guidance regarding a story proposal before proceeding. All manuscripts accepted for publication in Heritage New Zealand magazine are subject to editing at the discretion of the Editor and Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Online: Subscription and advertising details can be found under the Resources section on the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga website heritage.org.nz

HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND POUHERE TAONGA

National Office

PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140 Antrim House, 63 Boulcott Street Wellington 6011 (04) 472 4341 information@heritage.org.nz

Annie James, Manager Heritage Listing Kaiwhakahaere Rārangi Kōrero, discusses the purpose of the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero – and busts a few myths

For more than 50 years the identification of the places on the New Zealand Heritage List Rārangi Kōrero has been central to our work. The List tells the story of legislative change, the evolution of cultural heritage management, and the development of heritage identification in Aotearoa.

A combination of various recognition programmes through time, the List includes a wide range of places, from wāhi tapu and cultural landscapes to post-war suburbs and industrial sites. Under the current process set out in the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014, these places are considered not solely for their age but also for their social, cultural and historic significance to New Zealanders. Each reflects the diverse stories of Aotearoa and shifts the focus from just a place to the connection of people to that place.

The purpose of the List, as set out in the Act, is primarily as an identity and recognition tool, helping us understand why these places matter. While listing highlights the values of a place and can support environmental land use legislation, it does not in itself provide legal protection. Places are evaluated against robust criteria to recognise their significance, and List reports are based on verified sources. The process ensures the consistency, and credibility of the List, while making clear that recognition is distinct from regulation.

Heritage recognition tools such as the List help to shape who we are. They reflect our national identity and values, strengthen local pride, and give meaning to the places we share. Yet in the past, heritage recognition has often assigned privilege to certain

stories while leaving others out. With our organisational purpose of honouring the past and inspiring the future, initiatives such as the Rainbow List Project are helping to change this. Previously overlooked individuals and events important to queer history have been highlighted in our List entries. By broadening the histories and perspectives we recognise, the List can reflect all of Aotearoa and support a more inclusive future.

Many assume heritage-listed means a place is frozen in time, but listing doesn’t mean that a place can’t change. It means its values are recognised, and any changes don’t mean that those values are suddenly compromised. Many listed places continue to evolve, adapt, and serve new purposes while still telling their stories. A building that once housed the ‘Taj Mahal’ Public Toilets (Former) in Wellington (Listing: 1434) is now a celebrated pub. The Naenae Post Office (Former) (Listing: 9806) has a new life as a community centre. By reusing and adapting heritage places, we can also support environmental and sustainability goals. The List recognises the past while ensuring that places can continue to be useful and meaningful for the future.

The New Zealand Heritage List Rārangi Kōrero is a storytelling resource. It helps us to engage with our shared identity, celebrate our diversity, and make thoughtful decisions about the future. By understanding the true purpose and value of the List, we can better appreciate the role heritage plays in shaping a vibrant, inclusive Aotearoa. As the List grows and as more communities advocate for recognition, it reflects who we are now, not just who we were.

If you’re looking for a story that captures the drama and complexities of heritage in Aotearoa, it’s hard to go past the arrival of the Great White Fleet in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in 1908. If you haven’t heard of it before, it’s well worth investigating, combining international and local politics, secret invasion plans and one of the biggest parties the country has ever seen. When it came to the recent anniversary of the fleet’s arrival, we wanted to create a social media post that captured the event’s intensity – not just the daunting nature of the ships, but the scale and nuances of the celebrations.

In the past we’ve tried to do this using historical blackand-white photos, but the engagement has never been what we’ve hoped for. So, for this anniversary we decided to enlist help from artificial intelligence (AI).

Specifically, we used AI to colourise the photos. At first glance, this is a simple, long-established process. However, things are never as simple as they seem!

We encountered several challenges, with the most significant being historical accuracy. Professional colourisers often conduct months of research before they begin. Digital colourist Marina Amaral has noted that

she will check how specific dyes behave in different lights and investigate the impact of pollution before choosing colours. Unfortunately, we didn’t have time for this degree of research, but we did look into as many details as we could.

So, how accurate was our post – and did it capture the experience of Fleet Week? It’s hard to be sure, but one

thing the week did do was engage people, with more than 60,000 views across our channels.

If you’d like to know more about AI and colourisation, the work of Marina Amaral is a great starting point. You can find out more about Fleet Week here: visit-heritage. shorthandstories.com/thegreat-white-fleet/index.html

with Kerryn Pollock, Area Manager Central Region and Senior Heritage Assessment Advisor for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga

For this issue you write about Mātai Moana at Miramar Peninsula and Miramar Prison Garden. What’s something that you were surprised or interested to learn about this place/area?

I regularly visit Mātai Moana for weekend walks, but I didn’t know until I wrote that story about the historical importance of the farm. Seeing cattle and horses in the city, albeit in a large green space, reminds us that larger animals used to be a visible part of cities and that our urban centres have rural origins. Although we can perhaps be grateful that we don’t run the risk of tripping over a cow in the middle of the street at night due to lack of lighting like our early 19th-century forebears did (I once read a complaint about this in a Wellington newspaper on Papers Past).

What do you enjoy most about your job with Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga?

Heritage Assessment Advisors are the organisation’s historians (although our archaeologists may also lay claim to this title), and we get to be historical detectives, delving deep into the archives and finding new information and stories. This is a lot of fun and handy for pub quizzes! We are also privileged to work with communities to recognise their special places through heritage listing. It means a lot to be welcomed into these places and trusted with their stories.

What’s a favourite heritage place and why?

It’s so hard to choose one place so I will share an experience instead. I once visited the Treasurer’s House in York, England, and was intrigued by the story about Roman ghosts in the cellar, so I took the tour. Unfortunately for me, I was only haunted by being oppressively underground and fainted without seeing any spectral figures.

In ‘Carving the way’ in the Spring 2025 issue, we mistakenly referred to Martin Hadlee as Mark Hadlee. We sincerely apologise for this error.

At the risk of repeating myself, I’ll use this space to continue to emphasise the need for us to have up-todate contact details for our members – especially those details that allow us to communicate with you digitally.

This is because our membership programme is increasingly being delivered digitally.

As we’ve said in previous supporter news updates, the days of posting material to you are going, as it becomes more expensive and less viable (the exception being Heritage New Zealand magazine, which we will continue to deliver in the immediate future).

So we are working towards a digitally led programme for our supporters, one that will make renewing your membership as simple as possible. Plus, we’ll be enabling a more personalised membership experience where you can add the benefits you want or need.

However, all this will be delivered through email, our website and a digital account. That means if we don’t have a valid email address for you, you may miss out in the future, as we pivot away from post and towards this more personalised digital experience.

If you are one of those people who have an email address but haven’t yet shared it with us, please reach out. We can also discuss other options for getting information to you. If we can’t reach you by email, perhaps you have a mobile phone to which we can send messages and reminders (if you give us your permission to do so of course). And failing that, we may at least be able to help you renew and amend your membership more easily than by return of post.

As always, you can contact us using the details below. Yours digitally,

Brendon Veale

0800 HERITAGE (0800 802 010) bveale@heritage.org.nz

Go to heritage.org.nz for details of offices or visitheritage.co.nz to see historic places around New Zealand that are cared for by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

A selection of the wonderful heritage attractions available around the country this summer

Wellington Pasifika Festival (7 February 2026)

Wellington Pasifika Festival returns to Waitangi Park this year to celebrate the sights, sounds and flavours of the Pacific and highlight Wellington’s Pacific heritage. Last year saw a line-up of award-winning multicultural performers and a range of Pasifika food stalls, art displays and cultural experiences, alongside stone carving, a youth performance programme and an interactive experience for tamariki. And it’s free!

wellington.govt.nz/news-and-events/events-andfestivals/pasifika-festival

Art Deco Festival, Napier (19-22 February 2026)

Napier’s popular Art Deco Festival returns, celebrating the city’s claim to fame as the Art Deco capital of the world. Following the 1931 earthquake, the city was rebuilt in the style of the era, and nowhere else in the world can you see such a variety of 1930s-style buildings – from Stripped Classical to Spanish Mission, Prairie Style and, of course, Art Deco. What’s more, Napier’s Art Deco is unique, beautifully adorned with Māori motifs. Expect flying displays, parades, dances, fashion shows and much more.

artdecofestival.co.nz

Vero International Festival of Historic Motoring 2026, Nelson (15-21 March 2026)

This international rally of vintage and classic vehicles attracts people from all over the world, and this year also celebrates the 80th anniversary of the Vintage Car Club of New Zealand. Festival events include a ‘Museums Meander’, which takes in Willow Bank Heritage Village, Higgins Heritage Park and Nelson Classic Car Museum, and a ‘History Cruise’, which takes participants past many of Nelson’s historic buildings and sites, including Boulder Bank Historic Area. While you’re in the region, why not explore Trafalgar Street Historic Area, drop into the café at Melrose House (Category 1) or venture east to Rai Valley Cottage (Category 1), built in 1881 by the first people to settle in the isolated Rai Valley.

historicmotoring.org.nz

From 17 November 1925 to 1 May 1926, Dunedin hosted the New Zealand and South Seas International Exhibition, a world fair that attracted more than three million visitors (twice the population of the country) and covered 6.5 hectares of reclaimed land at Logan Park. The exhibition comprised seven pavilions grouped on either side of a grand court, a festival hall topped with a distinctive grand dome, a fernery, an aquarium, an art gallery, and an amusement park. It also had a ‘special exhibits’ section that focused on arts and crafts made by women. To celebrate the centenary of the exhibition, Toitū Otago Settlers Museum is hosting a display in its Twentieth Century gallery, as well as a public talks programme. There will be four talks, the last one in May 2026, so keep an eye on the museum’s events page for updates.

toituosm.com

@heritage_nz

@HeritageNewZealand

@HeritageNewZealand PouhereTaonga

@Pouhere_Taonga

@heritage-new-zealand -pouhere-taonga

When Heritage

New Zealand last spoke to Lindy Davis, she’d recently finished a seven-month project to restore the Category 2 former bank building in Waipū, which was reborn as Nova Scotia Junction, a commercial hub, so named because of its position on the corner of Nova Scotia Drive and Cove Road.

“Last year the building celebrated its 100th anniversary, and Nova Scotia Junction is now fully tenanted,” says Lindy.

“Alongside architecture firm Maxar Architecture on the first floor, there

are now Core Engineering Solutions, Harker Herbals’ head office, Little ’Lato gelato parlour (winner of New Zealand’s best gelato at the New Zealand Ice Cream Awards), The Cove Collective homeware store, which promotes crafts from New Zealand artisans, and Swell Yoga, a yoga and Pilates studio.”

The building started its life in 1924 as the National Bank of New Zealand, and when that closed in 1999 the complex was converted into a medical centre. It then

sat derelict for several years until Lindy and her family bought it in 2021. She managed the project and engaged local tradesmen, who set about stripping back years of modifications to reinstate the fabric of the original building.

Now the new tenants are able to enjoy the revitalised building and its restored heritage features. Swell Yoga’s studio has original polished rimu floorboards and a brick fireplace, with French doors opening to a large deck that overlooks

the garden. Harker Herbals’ office is a light-filled, openplan environment that combines the character of the original building with a modern, relaxed feel.

“Nova Scotia Junction now has a wonderful vibe,” says Lindy.

“It’s a world away from the derelict old bank building that was falling to its knees a few years ago.”

Ashort drive from Kerikeri in the Bay of Islands, at Butler Point, is Butler House and Gardens, a Category 1 historic place and the former residence of retired whaler Captain William Butler and his family. The 26-hectare property was established in the 1840s and has special significance as an early trading post that connected Māori, Pākehā and overseas commercial networks. The Butler Point Whaling Museum on the site explores the history of whaling in New Zealand through the story of Captain William Butler.

Surrounding Butler House are the Butler Gardens – designated a five-star Garden of Significance by the New Zealand Gardens Trust –which sit between the harbour’s edge and native bush. The gardens were restored in the late 1900s, and while many of the original plants were lost, notable trees include a southern magnolia and an olive tree, both planted during the Butlers’ tenure. Also on the site is an ancient pōhutukawa, thought to be around 800 years old, with a 12-metre trunk circumference that makes it one of the largest pōhutukawa in New Zealand. butlerpoint.co.nz

At an historic goldmining reserve in Central Otago, traces of the miners’ pursuits of fortune remain etched into the scarred landscape

Sheer cliffs, deep ravines, towering pinnacles and barren rock. No, this isn’t the American Wild West but Bannockburn Sluicings, a Category 2 historic place and Tohu Whenua, just a stone’s throw from Cromwell in Central Otago.

The man-made ‘badlands’ are the result of the sluicing – or water blasting – that occurred during Central Otago’s gold rush, as miners descended on the area in the 1860s and ’70s in search of the alluvial gold deposited in gravels beneath the Kawarau River terraces.

Miners worked the area for around 50 years, employing both hydraulic sluicing –high-pressure jets of water – and ground sluicing –directing the flow of ground water using a water race or sluicing channel. According to Terry Davis, secretary of the Otago Goldfields Heritage Trust (OGHT), which promotes historic goldfields in the area, the miners had to remove up to 10 metres of ‘overburden’ to get down to the goldbearing gravels below.

Terry says the site is special because it represents

all the required facilities of a working goldfield.

“It has the water races that filled the dams, the dams that fed the sluicing channels, the tail races that carried away waste material, the cliff faces, and piles and piles of stacked stones.”

These stacked stones, or tailings, are rocks that were too heavy to be carried away by the tail races. Other stones are remnants of the miners’ houses; one especially large pile is what remains of the blacksmith shop. Poorer miners lived in caves and rock shelters, which are also dotted around the area.

Charlie Sklenar, Central Otago Operations Manager for the Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai (DOC), says DOC is proud to manage the area and support the work of Tohu Whenua, which promotes and shares the story of the landscape and its rich history.

LOCATION

Bannockburn lies 59km to the east of Queenstown in Central Otago.

“Our work involves maintaining tracks and facilities and protecting heritage and archaeological features as well as native flora and fauna,” she says. One of those tracks is a 3.5-kilometre loop, winding its way uphill through the dramatic, scarred landscape

to Stewart Town and Menzies Dam (both Category 2 historic places), which overlook the sluicing faces of Pipeclay Gully and the surrounding vineyards. These two sites are the legacies of miner David Stewart and stonemason John Menzies.

Both Scotsmen, Menzies and Stewart arrived separately in Bannockburn in the mid1860s. Stewart secured the water rights to Long Gully (the sluicing area’s main water supply) and built a water race. The duo then constructed the dam in 1876, enabling them to control the miners’ access to desperately needed water and sell it at a premium.

Stewart and Menzies, along with other goldminers, including William Roy, lived in nearby Stewart Town, a cluster of nine earth and stone buildings centred around one larger stone house. This dwelling, known as Stewart’s Cottage or the Lind House, was built of split schist and mud mortar, and had a corrugated iron roof.

Both bachelors, Stewart and Menzies lived in the cottage together until Stewart’s death in 1883. Menzies died in 1894, and the cottage and dam were bought by miner David McGregor. It then passed through various hands until its last occupant left in 1938.

Today, little remains of the settlement – just Stewart’s Cottage and an orchard, thought to have been planted in the late 1800s or early 1900s by McGregor, that still yields apples, pears and apricots each summer.

In 2017, after receiving more than $180,000 in grants from the Lotteries Commission and Central Lakes Trust, the OGHT worked with DOC to undertake restoration work on the cottage and dam.

Damaged mortar and stones were replaced on the cottage, and a new freestanding roof was added to protect the walls from further water damage. Parts of the walls of the dam were also stabilised and rebuilt.

Terry says it was very much a community effort, with local businesses and individuals providing resources, expertise and labour.

“Donal Hickey [Wainwright & Hickey stonemasons in Dunedin] was in charge of the repointing and stabilising of Stewart’s Cottage, as well as work to restore the dam wall,” he says.

Local engineer Bevan Todd, from McIntyre Engineering in

Cromwell, manufactured the roof structure, and a builder who grew up playing in the cottage as a child fitted the roof with iron.

“We reused the iron that was removed from the roof of Bannockburn’s Coronation Hall during its restoration in 2016,” says Terry.

Another local, Jack Davis, borrowed a tractor to lift the pre-made roof into position, and OGHT members handdug the holes for the corner posts and concreted them.

A heritage tree grove was also planted just west of Menzies Dam, using saplings propagated from the 130-year-old apricot trees beside Stewart’s Cottage, and

a picnic table was built out of recycled telephone poles.

The OGHT organised an opening celebration to commemorate the restoration work.

“We had a ‘Victorian picnic’, where attendees dressed in period costume took part in games such as three-legged races, sack races, and egg and spoon races, and enjoyed a feast of scones, cupcakes and other Victorian-themed picnic items,” says Terry.

Jill Mitchell-Larrivee, Regional Co-ordinator for Tohu Whenua Te Wai Pounamu South Island, says Bannockburn Sluicings is an excellent example of a Tohu Whenua – a special place that helps tell the story of Aotearoa New Zealand.

“It’s authentic, accessible and ready for visitors, and the story of the place unfolds as you explore,” she says.

“What looks a bit desolate when seen from the entrance turns into a rewarding labyrinth of trails through a valley of caves, tunnels and rock tailings left untouched since the area was abandoned by the last of the mining men.”

Search the listing numbers at heritage.org.nz/places to read more.

A grand old Hawke’s Bay residence has become a guardian of local history, preserving the stories and records of the region

WORDS: NICOLA MARTIN / IMAGERY: SARAH HORN

In the heart of Hastings, a 19th-century villa hums quietly with the vibrancy of memories.

Just off the Hawke’s Bay Expressway, Stoneycroft House is a landmark in the streetscape at the intersection of the Expressway and Omahu Road. Built in the 1870s in the distinctive

Carpenter Gothic style, the Category 2-listed Stoneycroft is considered one of the oldest homes in Hastings.

It is more than a heritage building, however; it has become an archive and community hub that is now home to the Hawke’s Bay Knowledge Bank, a digital record of the region and

its people. Also operating from its grounds is the Lily Baker Library, which includes a collection of important records accumulated by Hawke’s Bay genealogists.

Linda Bainbridge, Hawke’s Bay Knowledge Bank Manager, says the building’s age and architectural features make it a fitting

Hastings is about 18 kilometres southwest of the coastal city of Napier in Hawke's Bay.

home for the organisation. “We’re housing and creating history in an historic building, and that’s a lovely dynamic.”

Built in the mid-1870s as a townhouse, Stoneycroft passed through various owners before being purchased by the Ballantyne family in 1954. Diamond Allan Ballantyne and his wife Joyce lived in the house for 50 years, altering little during this time. It was Joyce Ballantyne who pursued the heritage covenant on the home, having it registered in 1995. After her death, the house was purchased by Hastings District Council in 2005.

In her recent report on Stoneycroft, Anna RentonGreen, Heritage Assessment Advisor Central Region for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, traced the history of the house and its original construction, as well as its later history as the home of the Ballantynes.

As part of that research, Anna discovered the house was originally built by the Birch brothers, William and Azim, who owned a stock run and holdings in Pātea. The

brothers most likely had the home built as their base, as they were both councillors and active in the local Napier-Hastings community.

After making many difficult 10-day journeys by packhorse through to Napier for wool sales and agricultural services, the Birch brothers were instrumental in the construction of the Napier-toTaihape road. Both brothers gave Stoneycroft as their address between 1878 and circa 1884, when they seem to have moved permanently to Pātea. William Birch’s wife Ethel was also active in the Pātea community, and was the first European woman to climb Mount Ruapehu.

“While Stoneycroft has a new and important role in the Hastings community as an archive repository,” says Anna, “it is also noteworthy as a representation of settler lifestyle, pastoral enterprise, and regional development in Hawke’s Bay.”

The transformation to the living archive it is today began in 2011, when the Hawke’s Bay Digital Archives Trust was formed to create a space for safeguarding the region’s history. With support from the Hawke's Bay Branch of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists and local fundraising, the building was restored and reopened on 1 December 2012.

A solid community has been built around the home and its historic offerings. Linda says a core of about 12 volunteers involved with the trust drove the restoration from 2011 and now a team of up to 60 keeps the doors open every day.

“The house was pretty much in rack and ruin when we moved in,” says Linda. “When it rained, the water literally ran down the inside of the walls.”

The renovation of the historic building was a massive undertaking.

Volunteers worked alongside expert tradespeople to deal with everything from water damage to possum infestations. They stripped and repainted original surfaces, rebuilt the maids' quarters and worked to preserve original wallpaper and woodwork.

“It took them four months to strip paint off the staircase, sand it back, and get it to the condition that it’s in today,” says Linda.

When they stripped back the fireplace in the main room, they discovered that there were 13 different types of wood.

“You don’t get that kind of craftsmanship today; the detail of the building is something I love.”

Today, Stoneycroft’s charm remains intact. From kauri skirting boards that extend almost 30 centimetres to century-old wallpaper befitting the period, every detail tells a story. Even the upstairs bathroom, with its window overlooking the park, holds quiet appeal.

“That’s one of my favourite spots,” says Linda. “The window is shaped like a house, and you look out over the park.”

Inside, the Knowledge Bank is a hive of activity. The 60-plus volunteers contribute more than 1000 hours each month, digitising letters, photos and records.

“We rely on people to give us information,” says Linda. “You don’t have to be important to bring your family history here; we hold it all.

“Councils are expected to retain information at a regional level, but it doesn’t tell you about the people who made up the region. We help to tell those stories.”

People can also access the archive online. Putting in your family surname can return some really interesting information, says Linda. She

recalls her first task at the Knowledge Bank in 2016: transcribing The Handbook of Hastings (1929), a publication offering a vivid snapshot of life before the 1931 earthquake.

“It had things like how many streetlights there were, how many streets had footpaths, and even detailed the monkeys in the zoo at Cornwall Park,” she says.

“It was so detailed, and little did they know that their lives were going to fall apart in two years’ time when the earthquake hit.”

One current standout project is the Cyclone Gabrielle oral history collection being compiled by volunteers, capturing stories from 150 Hastings residents.

“We have so many dedicated volunteers, and without them the Knowledge Bank wouldn’t be able to do this work,” says Linda.

However, as it is with the preservation and maintenance of many heritage buildings, funding remains a challenge. With annual costs of around $100,000, the organisation receives modest support from councils and grants but must reapply each year. A suggested donation system is being introduced to help ease the burden, says Linda.

Despite the challenges, Linda and the team of volunteers are resolute.

“If we don’t continue to preserve these stories, they’re going to be lost.”

Stoneycroft is not just a building; it’s a place in which history is made, remembered and shared. Those who pass it on the Expressway may admire it as a striking landmark, but inside, it’s alive with the voices of Hawke’s Bay.

Search the listing number at heritage.org.nz/places to read more.

A chance childhood visit to a family friend sparked a lifelong love of our built heritage for Dame Jo Brosnahan, Board Chair of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga

“The stories we tell ourselves as a nation are incredibly important to the nature of the people that we are. Built heritage, both Māori and colonial, is at the very core of that storytelling.”

For Dame Jo Brosnahan, it was this core belief that made her decision to take on the role of chair of the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Board a straightforward one. Now almost a year into the role, Jo says that, despite having a full dance card of governance, leadership and service roles, accepting the role of chair came down simply to believing she could add value.

Much of this value comes from her professional experience, having served as chief executive with both Northland and Auckland regional councils, as well as chair for a range of organisations such as Northpower Fibre, Taitokerau Education Trust, Maritime New Zealand, Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua, Harrison Grierson, and Leadership New Zealand Pūmanawa Kaiārahi o Aotearoa. It’s a career and commitment to service that in 2005 saw Jo appointed a Companion of the Queen’s Service Order for public services, and then, in 2023, Dame Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

Alongside all those achievements and accolades, Jo has also maintained a lifelong passion and interest in history and heritage.

“I remember walking around that villa thinking how incredible it was to be able to touch a tangible piece of the past”

“Our membership number [of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga] is 202, so my husband and I joined right near the very beginning. I’ve always had that passion for heritage and the stories around it, so when I was approached about being chair, while I wasn’t really looking for another board role, because it was heritage I had to say yes.”

Jo’s passion for heritage was first sparked as a child in Whangārei, when her parents took her to an old house owned and about to be renovated by family friend Kev Wilkinson. That visit remains firmly fixed in Jo’s memory.

“I remember walking around that villa thinking how incredible it was to be able to touch a tangible piece of the past. I can still

Although she has a broad, wide-ranging interest in New Zealand’s heritage, Dame Jo’s own family history is woven into the country’s DNA.

“My great-grandfather, Colin Campbell, came to New Zealand in the 1860s, first to Dunstan and then Hokitika before going to Ross as the bank manager for what was then the Bank of New South Wales. He built the original bank building, which is now the Ross Information Centre (part of Ross Historic Area), although it was later rebuilt. He was in the goldfields at the beginning of the rush right through to the end. He moved on to Reefton and then Milton, where he built another grand bank building.

“My great-great-grandfather, Dr George Bodle, settled in Alfriston, south of Auckland. His forebears had come from Alfriston in England a few generations before. He helped to build the little Christ Church (Category 2) there, along with a tiny meeting hall that’s still there but very dilapidated.

“That was all on my mother’s side. On my father’s side, my great-great-grandfather owned big circuses, and my

great-grandfather was a clown. They travelled New Zealand from the 1870s right through to the 1940s. My grandmother came out to New Zealand as a concert violinist and ended up marrying the circus proprietor!

“My other great-grandfather, Alexander Campbell, came with his family to New Zealand from Scotland and moved to the Kaipara area. They found the property to be nothing like it had been promoted, so he ended up in Auckland as a warehouseman, importing clothing. He built a property in Symonds Street that’s still there, protected by the University of Auckland. Then he bought the end of Northcote Point and lived there till he died.

“I love genealogy because I love the stories, and I love being able to travel around the country with my husband Chris. His family history is also interesting – his great-great-grandfather was Paddy Gilroy, a whaler from Bluff with extensive connections there to Ngāi Tahu.

“We travel the country and find the places, talk to the people and visit the old museums. It’s amazing how the past can come alive – it’s that sense of being able to travel back in time, to touch history and to know who we are.”

Dame Jo was photographed at Ewelme Cottage in Auckland. Find out more information and how to visit at www.visitheritage. co.nz/visit/ auckland/ewelmecottage

“If I have one hope for what I’d like us to achieve, it would be for more people to share that love and fascination for these places”

remember the kauri and the beautiful tiled fireplaces.

“I felt a similar thing when we used to visit the Ruapekapeka Pā when I was a child, long before it was restored in any way. Lying in the long grass with the old cannons and the holes in the ground, you could imagine the battle and the people who had been there. It really brings the past to life.

“I’m still fascinated by that today, travelling around to old gold towns like Hokitika or places like Ōamaru and Dunedin, where all those old buildings still remain. I remember on the Whanganui River being shown an old pātaka in the bush. You can really feel the past.”

Although that love of history has not played a fundamental part in her professional life, it has helped inform some projects of which Jo is most proud. The restoration of traditional baches and an early concrete homestead at Scandrett Regional Park in Auckland is one; the full archaeological survey of archaeological sites around Whangārei Harbour is another.

“I always tried to make sure we maintained a respect for heritage and undertook some depth of research around it. We made it a particular focus at the Auckland Regional Council.”

Through her years in local government, Jo says one of the biggest changes she’s seen is the attitude towards the preservation of Māori heritage.

“It’s been a growing thing over the years, as we have all recognised the importance of these places in different ways, and the fact that without conscience in many places our Māori history has been largely built over by Europeans.

“It is important that we do what we can to uncover that, for Māori and for all of us in Aotearoa. There has been some great work done more recently to identify sites that can be used to tell the story,” she says, citing the preservation of Te Aro Pā (a Category 1 historic place) in Wellington as an example.

As well as continuing to work closely with the Māori Heritage Council on the protection and preservation of Māori sites of importance, Jo sees raising brand awareness of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga as key to the organisation’s ongoing success. She believes increased awareness, looking to the UK’s National Trust as one example, could help drive a growth in membership and the ability for the organisation to become more self-funding.

Having spent her first months as board chair

travelling around the country, Jo says one place to start is working with communities to help promote the treasures they may have and gain a better understanding of how those places sit within their communities already, and how that affects the way they’re used and preserved for the benefit of heritage tourists and locals.

She cites Russell’s Pompallier (a Category 1 historic place) as a prime example. “It’s probably the key heritage tourist attraction in Russell, but it’s not just the house itself and its history. It also has a great store and a fabulous café, which is one of the most popular places to gather in Russell.

“These properties are multifaceted and highly connected to their local communities. It’s important to recognise that.

“If I have one hope for what I’d like us to achieve, it would be for more people to share that love and fascination for these places. They tell our story as a nation; they identify where we came from and who we are. That would mean they’re better protected and funded.

“That said, as I’ve travelled around the country I’ve been incredibly impressed by the calibre of people we have who are dedicated to promoting and enhancing these heritage places.

“We’re called Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, and I think taonga is exactly the right word. These places are our taonga. I want to do my bit to protect and promote them.”

pātaka: storehouse taonga: treasure

From Māori pā and military strongholds to the grounds of a prison garden, the landscape of this Wellington peninsula has been shaped by many hands

WORDS: KERRYN POLLOCK / IMAGERY: MIKE

It’s a beautiful Wellington day and I’m heading out with my wife and our dogs to Mātai Moana

Mount Crawford on Te Motu Kairangi Miramar Peninsula. Mātai Moana is an ancestral mountain for Taranaki Whānui ki Te Upoko o Te Ika, mana whenua of Te Whanganui-a-Tara. It is a place of layered histories stretching back centuries, and it helps to know a little before you go. This is where Kate Curtis, local history educator and Miramar Prison Garden volunteer, comes in.

Kate moved to Miramar from Sydney in 2015 and found her way to Mātai Moana. She got involved after becoming interested in the history of the garden and the wider area. With a background in teaching, Kate’s contribution is education and while she remarks, “I sometimes feel like the garden member who does the least gardening!”, her footprint is everywhere.

She has created a mini museum in the greenhouse and learning materials for the Aotearoa New Zealand Histories curriculum, including a trail map of the

many historic sites of Mātai Moana, and she runs school programmes and workshops. But it’s more than personal interest that drives Kate.

“The more I learned about the stories of the people who had settled, lived and worked up here, the more I knew they were the key to engaging people. I wanted others to learn what I had and to advocate for the future of Mātai Moana. If you don’t know about a place, you can’t grow to love it. And if you don’t love it, you’re not going to take care of it.”

Map in hand, we set off from the carpark next to Mount Crawford Prison (which opened in 1926 and closed in 2012), walk down Nevay Road, and enter a paddock through a classic pipe-and-netting steel farm gate. Our four-kilometre walk will take in pā, kāinga, military, prison and commemorative sites. The inconspicuous track is a little hard to find but the map tells us to look out for a patch of concrete. Once we’ve spotted it, we go forth like hobbits on our great adventure.

We detour through a bush-clad gully when we encounter a herd of cattle resting on the track. While they gaze in our direction with an air of disinterest, we don’t want to push our luck. We are in their territory after all – part of Mātai Moana is leased for farming, and cattle are part of the experience. It is considered one of New Zealand’s oldest continuously run farms, dating back to early Pākehā settler James Coutts Crawford, who acquired the land in 1840. It was later farmed by prisoners and has been leased to a local for the past 26 years. The farm is Kate’s favourite place on Mātai Moana.

“To have a working cattle farm within a major city provides such a wonderful learning opportunity and link to rural life,” she says. “The groups of students I bring up are beyond delighted to be able to see cows and horses up close, often for the first time.”

We rejoin the track at a plateau above the gully. We’ve reached our first site of interest, Puhirangi Pā. This early 1500s Ngāi Tara fortification site has commanding views and is associated with the rangatira Te Rangitūpewa and Te Ihunui o Tonga, his wife, who is immortalised in the mōteatea she composed at Puhirangi after the passing of their daughter Rangi. Standing on the plateau where Te Ihunui o Tonga sat hundreds of years ago to farewell her daughter, it’s easy to imagine her lament being carried on the wind and out to sea:

I a au ki roto o Puhirangi / Here in Puhirangi I sit E rauwiri noa mai rā a Hine-moana i waho / Looking forlornly forth on Hine-moana surging unrestrainedly beyond the headlands

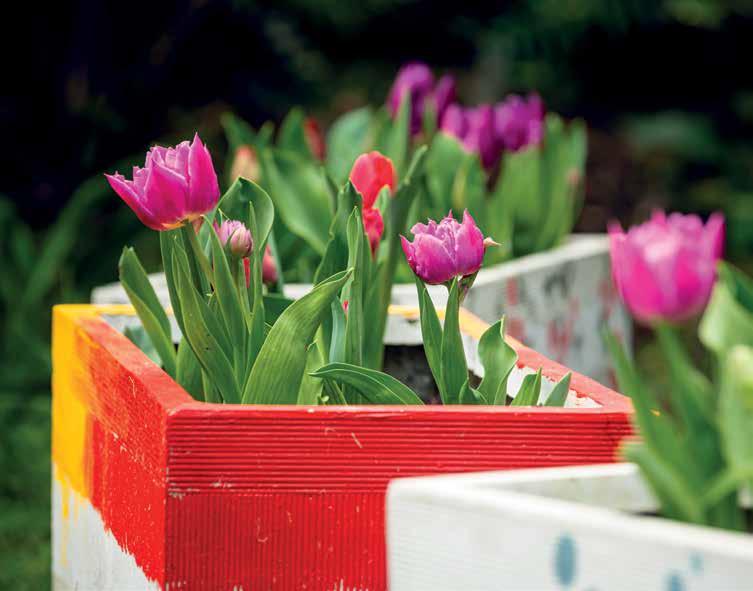

1. Kate Curtis, local history educator and Miramar Prison Garden volunteer, at her favourite place on Mātai Moana, the farm.

2. The Massey Memorial.

3. Daisy, Kerryn and Kate on one of the farm tracks.

4. Prisoner-built retaining walls and steps in Miramar Prison Garden.

5. Tulips are some of the many different flowers grown in the prison garden.

6. Inside Fort Ballance.

7. Kerryn and Daisy inspect one of the old farm buildings.

Tēnā ia koe ka riro i te au kume / But you have gone, borne on the ocean stream.

We walk through a gate to the glorified track that is Fort Ballance Road. A Category 1 historic place, Fort Ballance was constructed in 1885 in response to a feared Russian attack that never eventuated. It is incredibly intact, and you can walk through the tunnels and gun pits and peer out of the loopholes in the musket parapet to the harbour entrance.

Fort Ballance was built on Te Āti Awa pā Te Māhanga (The Snare), which had a similarly strategic oversight of Te Au a Tāne. Down below on Massey Road is the site of Te Māhanga kāinga, a seasonal fishing village that was a favoured residence for Te Ātiawa people in times of peace. From the 1880s, Māhanga Bay was used for military purposes and volunteer soldiers held war game camps there until World War I.

Further along Massey Road, near the centre of Kau Bay, pine trees clinging to the slopes retreat inland at the site of Kau-whakāra-waru kāinga, a Ngāi Tara village. We walk a further 500 metres and arrive at the much-photographed Point Halswell Lighthouse, built in 1912. The te reo Māori name for Point Halswell is Rukutoa, indicating a diving spot best tackled by the strongest toa only.

Next, we head to the Massey Memorial, also a Category 1 historic place, and the final resting place of Prime Minister William Ferguson Massey and his wife Christina. The classically influenced Tākaka marble and Coromandel granite memorial was built

“The more I learned about the stories of the people who had settled, lived and worked up here, the more I knew they were the key to engaging people”

in 1930 on the site of a gun pit associated with Point Halswell Battery, another Russian-threat-era site.

A steep track on the slope above takes us to World War II anti-aircraft batteries: four octagonal concrete gun emplacements and a rectangular command post built in 1942. The view over Te Whanganui-a-Tara from the northernmost emplacement is magnificent, and it is well worth stopping here for a picnic.

Further up is the site of Port Halswell Barracks and Prison, built in the 1880s, and its successor, Port Halswell Women’s Reformatory, constructed in 1920.

A brick retaining wall and steps to nowhere are remnants of the reformatory. An 1885 military road takes us towards our starting point as we pass more World War II structures and the site of the centuriesold Ngāti Ira pā Te Mata ki Kai Poinga.

Three hundred metres up the track, we’ve come full circle. Our final stop is Kate’s beloved Miramar Prison Garden, where prisoners produced food for the prison kitchen and seedlings for tree regeneration on the peninsula and beyond. After the prison closed in 2012, community gardeners led by John Overton took

over guerrilla-style and secured a lease two years later. The garden is concealed by tall trees and we feel a bit like Mary Lennox of The Secret Garden encountering a hidden place of beauty. It is a horticultural wonderland of five garden areas full of vegetables, fruit trees and flowers, with a mature pūriri tree at the centre beside a greenhouse built by prisoners around 1940, and retaining walls, paths and planters throughout the site.

It is easy to understand why Kate is so passionate about its preservation. The recently announced 72-hectare Mātai Moana Reserve, to be managed by

Taranaki Whānui, Wellington City Council, and the Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai through a trust, includes most of the places we visited on our walk but not the prison nor garden. Nevertheless, Kate says having the reserve wrapped around the garden will help it flourish.

“There is a wonderful community of locals and visitors who, now that they know about this place, love it and want to care for it.”

We leave the garden with our fingers firmly crossed that it too will be safeguarded into the future.

“There is a wonderful community of locals and visitors who, now that they know about this place, love it and want to care for it”

kāinga: settlement/village mana whenua: those with tribal authority over land or territory mōteatea: lament/ traditional chant pā: fortified settlement rangatira: chief toa: champion/warrior

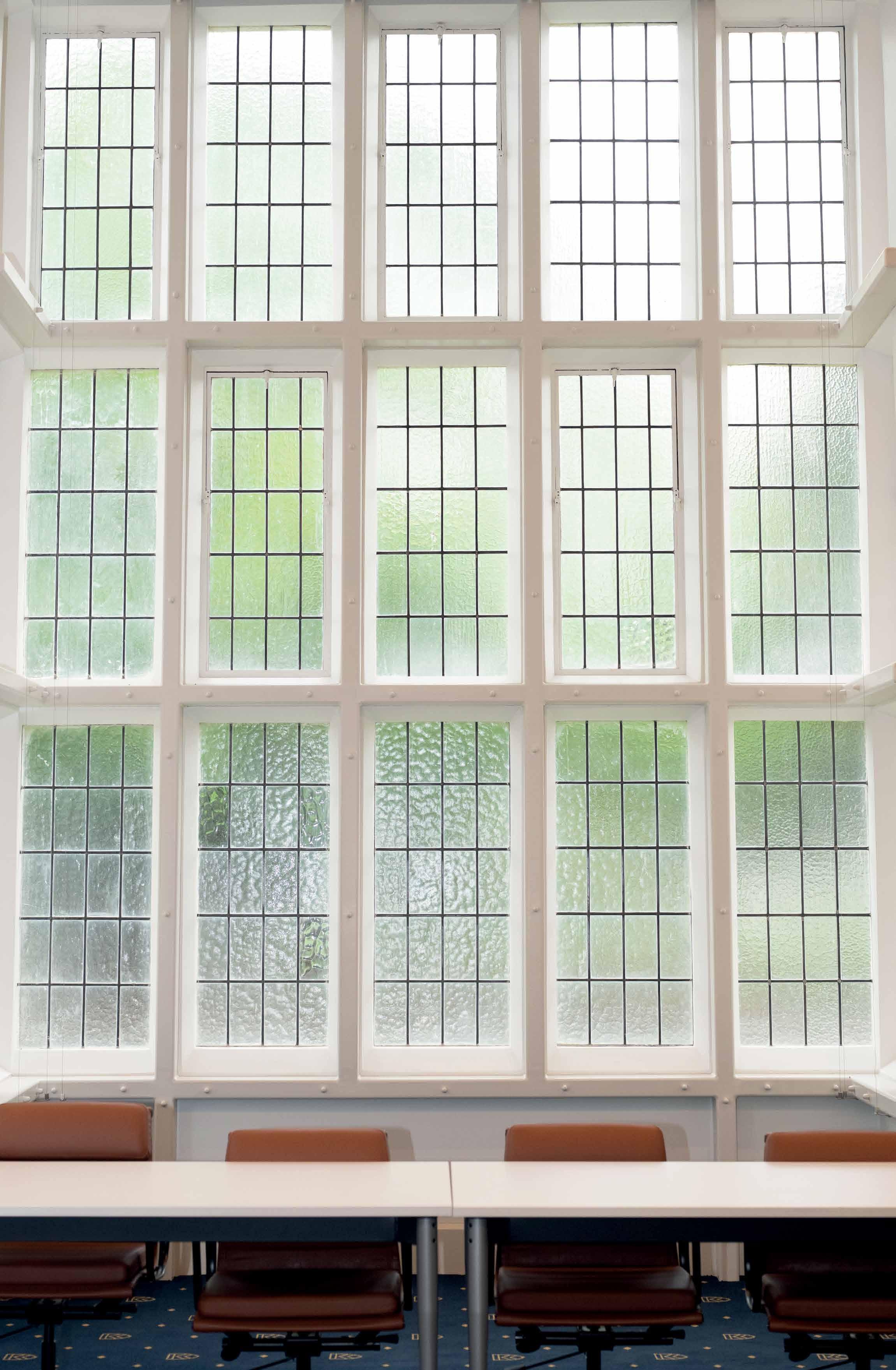

The reconstructions of Ivey

Lincoln University Te Whare Wānaka o Aoraki have seamlessly combined seismic engineering and traditional craftsmanship

WORDS: KATHY YOUNG / IMAGERY: NICOLE GOURLEY

Standing in the restored corridors of Ivey West and Memorial Hall today, it’s hard to imagine that these buildings once lay in ruins. The 2010-11 Canterbury earthquakes left the most historic structures at Lincoln University Te Whare Wānaka o Aoraki severely damaged.

Yet in February 2025, these buildings reopened as the administrative heart of New Zealand’s only specialist land-based university, their Category 1 historic place status preserved and celebrated through one of the country’s most ambitious heritage restoration projects.

Ivey Hall, designed by Frederick Strouts and built between 1878 and 1880, is one of New Zealand’s earliest large structures in the Jacobethan architectural style still in existence. This building was largely unaffected by the earthquakes because of previous strengthening work in the mid-1980s.

However, Ivey West (the west wing of Ivey Hall), which was added to Ivey Hall in 1881 to provide student accommodation, suffered collapsed gables and cracked and displaced unreinforced masonry walls.

The same fate befell Memorial Hall, which was designed by Cecil Wood, a student of Strouts, and completed in 1923. Built to commemorate Lincoln staff and students who lost their lives during World War I, and later acknowledging losses from the South African War and World War II, it became a focal point for local Anzac Day commemorations. It also hosted international peace talks in 1998 between Papua New Guinea and Bougainville. This culminated in the Lincoln Agreement, which ended 10 years of civil war in Bougainville.

Christine Whybrew, Director Southern Region for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, congratulates Lincoln University for honouring these special buildings and finding new uses for them.

“Generations of alumni have enduring connections with Memorial Hall and Ivey West, so it’s heartening to see them reinstated at the centre of campus life.”

When the university’s council gave the green light to reconstruct and restore Ivey West and Memorial Hall in June 2022, the complex preservation puzzle began. These were not merely old buildings but irreplaceable examples of New Zealand’s colonial architectural heritage. They needed to function as modern administrative spaces in ways that honoured both their past and future needs.

Also central to the restoration was the need to make the buildings perform to modern standards without sacrificing their essential heritage character. Better connectivity, daylighting and insulation were required to enhance functionality and user comfort. New accessible pathways were needed to connect the buildings to the wider campus, including the adjacent Ivey Hall and campus library, creating a continuous heritage facade.

“There was a balance between making the buildings useful and modern, so that they could fit within the needs of the university, while still retaining existing heritage value,” explains William Fulton, heritage architect at Team Architects and Lincoln University alumnus, whose team led the architectural element of the restoration.

This balance of old and new defined every decision throughout the project, from structural engineering to interior layout, from mechanical systems to material choices.

The restoration team’s approach varied between the two buildings, reflecting their different historical purposes and structural conditions.

Memorial Hall, with its sacred function as a war memorial, was treated with particular dignity.

“The architectural concept was to ensure that the space felt the way it did pre-earthquake,” says William.

While some steel reinforcement is visible in the rafters in the vaulted ceiling, the space needed to maintain its essential character as a memorial to fallen soldiers.

“War memorial plaques were carefully reinstated, and the space was designed to accommodate both solemn Anzac Day services and practical university functions like council meetings,” explains Alistair Pearson, Property Director at Lincoln University.

“At our recent student Hui Whakatuwhera Open Day, we were delighted to hear many visitors and prospective students commenting on the impressive nature of the buildings.”

Ivey West presented a different challenge. Originally a series of small boarding house cells, much of the internal structure required complete reconstruction. Yet even here, the design honoured the building’s history.

“The offices are the same size as the original dormitory rooms,” William says, “but now with glass walls instead of masonry.”

This approach maintained the spatial rhythm of the original floor plan, while creating modern, flexible office space flooded with natural light.

The structural demands of this project were staggering. The buildings, constructed of unreinforced masonry, required extensive asbestos removal, stone and brickwork repairs, and complete seismic strengthening to meet modern building codes. The engineering challenge was compounded by the need to install contemporary mechanical systems in buildings that originally relied on fireplaces for heating and open windows for ventilation.

“Essentially the integrity of the external facades remains intact,” says Alistair. “New work was required to replace lost and damaged fabric. A new slate roof, new brick gables and new limestone cappings were all replaced with like-for-like materials. Where changes were made to support new entry points, they were designed to be obvious modern insertions, following conservation principles that distinguish new work from historical fabric.”

The total reconstruction took 96 weeks.

One of the project’s most significant aspects is its integration of Māori cultural narratives into the colonial architecture. Working with Ngāi Tahu artist Morgan Darlison and Cultural Advisor and Lincoln University’s Pro-Chancellor Puamiria Parata-Goodall from

“There was a balance between making the buildings useful and modern, so that they could fit within the needs of the university, while still retaining existing heritage value”

1. The space has a modern interpretation to accommodate the flexible office spaces.

2. Ivey West and Memorial Hall have been meticulously preserved.

4. Memorial Hall has a sacred function as a war memorial.

5. These offices were once dormitory rooms.

6.

Te Taumutu Rūnanga, the team wove tangata whenua storytelling throughout the restored spaces, thus valuing both the historic European heritage and te ao Māori.

Grant Edwards, Vice-Chancellor of Lincoln University, is delighted with the results.

“Morgan has designed patterned wallpaper and glass manifestations that represent various aspects of our takiwā, the local flora and fauna, and the narratives,” he says.

“The glass designs relate to the ebb and flow of the waterways and the mauri of the water to sustain all living things. It’s all about growth, cultivation and regeneration.”

“The meaningful integration of the cultural narrative and the expression of the enduring presence of Ngāi Te Ruahikihiki is outstanding,” says Christine. “This demonstrates the possibilities for recontextualising colonial era heritage buildings, and it’s beautiful too.”

The project’s commitment to land-based heritage extended to material choices that reflect the university’s agricultural focus. Wool-based products were used throughout the restoration. Wool carpets, carpet tiles and acoustic panels became canvases for artwork.

These panels, developed by the Wool Research Organisation of New Zealand in partnership with Lincoln University, Lincoln Agritech and AgResearch, are fire-resistant and chemical-free, and have been likened to ‘acoustic wallpaper’. This adaptive reuse significantly reduced the carbon footprint of the building. Today, the buildings serve as the Vice-Chancellor’s office and the offices of the Senior Leadership Te Manutaki, Alumni and Development, Strategic Communications and Project Management teams.

Rather than preserving the buildings as museum pieces, the historic structures have been given new life while retaining their essential character and cultural significance. The buildings now embody what William calls “a contemporary quality of lightness that references a deeper history”.

As Lincoln University approaches its 150th anniversary in 2028, the restorations of Ivey West and Memorial Hall are now aligned with the university’s resilience and vision and have allowed them to reclaim their status at the heart of the campus.

“It’s an absolute pleasure and honour to occupy these restored spaces,” says Grant. “Everyone will have their favourite spaces. For me, it’s the historic kauri staircase and the custom carpet featuring the Lincoln University crest. All of the restored buildings and surrounding artworks, landscapes and farms speak to the unique mauri of this place, this whenua and its deep connections to our people – past, present and future.”

mauri: life force takiwā: region tangata whenua: people of the land te ao Māori: Māori world view whenua: land

Flowing mostly unseen below Wellington’s streets for more than a century, an ancient stream has now been officially recognised for its cultural and ancestral significance to Māori

Arecent addition to the New Zealand Heritage List Rārangi Kōrero (the List) retraces the pathway of a small awa consigned to almost complete darkness in the heart of Wellington City.

The small portion of the Kumutoto Awa that still flows above ground has been recognised as a wāhi tūpuna (a place important to Māori for its ancestral significance and associated cultural and traditional values), casting new light on the history of this buried waterway. Located in Kelburn’s Kumutoto Forest, it’s also the only section of the awa that still follows its natural course.

Research for the listing was undertaken by Dennis Ngāwhare, who is Kaiwhakatere Kaupapa Māori Manager of Māori Heritage Recognition for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. He oversees the addition of wāhi tapu, wāhi tapu areas and wāhi tūpuna to the List, and also lectures part-time at Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka.

As an undergraduate in 2002, Dennis was introduced to the awa by Peter Samuel, the kaumātua of Te Herenga Waka. Later, revisiting the awa with students from his cultural mapping paper grew his interest and knowledge of the awa pathway, which once flowed uninhibited from the hills of

Kelburn to the sea. When he received an application from representatives of Ngāti Te Whiti to recognise the Kumutoto as a wāhi tūpuna on the List, Dennis was ecstatic.

“I walk past the Kumutoto daily, between my home in Kelburn, the university and Antrim House. I always felt that the story of the awa and the tūpuna who once lived there needed to be told. This was a great opportunity to weave the story of water and people together in a listing report.”

After much research, investigation, and some encouragement from mana whenua, he completed a report that explores Kumutoto Awa and brings to light the history of Kumutoto Pā, a traditional harbourside papakāinga.

The origins of the name Kumutoto are blurred by time, but stories recall a special place – a birthing pool and birthing stone in the lower reaches of the awa. Here babies likely entered Te Ao Mārama (the world of light), and their mothers bathed away the exertions of childbirth.

The Kumutoto listing is unusual because the extent, centred on the daylighted part of the awa and surrounding Kumutoto Forest, is a tiny representation of a much broader area encompassing the Wellington

Botanic Garden ki Paekākā, the university and a portion of heavily built city land up to the old harbour shoreline. History rich, the report reveals details of 19th-century Māori occupation in the heart of Wellington city and touches on the much earlier significant explorations and occupations of Ngāi Tara, Ngāti Ira and other iwi who were present in and around the harbour and along the South Coast area over many generations.

From the summer of 1818, land occupation changed through the presence of the musket gun. Other iwi pushed their way into Wellington Te Whanganui-aTara, driving Ngāti Ira away.

Later, migrations from Taranaki, including Te Atiawa, Ngāti Tama and Ngāti Mutunga, occurred. They settled the inner harbour, and papakāinga were set up at Te Aro, Pipitea, Kumutoto and other sites.

Kumutoto Pā was established by Wi Piti Pomare of Ngāti Mutunga at the mouth of Kumutoto Awa in 1824, approximately on either side of present-day Woodward Street. Here the awa met the sea at what is now Lambton Quay.

“Kumutoto Awa was an important waterway for the ancestors of Ngāti Mutunga and Te Atiawa. Its name is linked to traditional birthing practices, and the stream

1. An escape into the calm of nature. 2. A chalk scrawl welcomes visitors on the one-year anniversary of restoration efforts. 3. With rubbish and weeds removed, the water clearly reflects sky and surrounds. 4. Dennis Ngāwhare. 5. The rocky bed of the awa provides a habitat for tiny native fish and crustaceans.

played a central role in Māori life during the early settlement of Wellington,” says Dennis.

In 1835 ownership was passed over to the tūpuna Ngātata-i-te-rangi of Ngāti Te Whiti, Te Atiawa and associated hapū, when Ngāti Mutunga migrated to the Chatham Islands Rēkohu Wharekauri.

“Kumutoto Pā had strong traditional associations with ancestors significant to Taranaki iwi and hapū and Te Atiawa maintains mana whenua over this area today,” says Dennis.

The Kumutoto māra kai were located near the source of Kumutoto Awa on Pukehinau, below what is now Wellington Botanic Garden ki Paekākā. The urupā for the people of Kumutoto Pā, Pipitea Pā and other settlements was situated where the Bolton Street Cemetery is today.

After the massive 1855 earthquake, which provided the rapidly expanding city with 155 hectares of new harbourside land for reclamation, parts of Kumutoto Awa were culverted.

Today the upper reaches of the stream are channelled under Kelburn Parade and fed by the water table beneath Pukehinau Ridge. Aside from its brief journey in fresh

awa: stream

hapū: sub-tribe kaiwhakatere: project manager

kākā: native parrot

kaumātua: elder

kaupapa: project, initiative or principle

kawakawa: pepper tree

kererū: wood pigeon

kōaro: whitebait

korimako: bellbird

kōura: freshwater crayfish mana whenua: those with tribal authority over land or territory

māra kai: food gardens

papakāinga: village

pīwakawaka: fantail tūpuna: ancestors

urupā: burial ground

wāhi tapu: site of sacred significance

wāhi tūpuna: site of ancestral significance

air, the stream pours through old pipes and modern stormwater outlets into the Terrace Tunnel culvert.

Before the northern motorway was constructed, the stream ran through the forested Shell Gully behind The Terrace. “Generations of people grew up with this stream flowing through their gardens,” says Dennis.

Today, pipes run under the motorway and Kumutoto Lane, parallel to The Terrace, before branching at Woodward Street and finally entering the sea at Kumutoto Plaza.

Present-day Wellingtonians and explorers of this beautiful, green-fringed city will be familiar with Woodward Street, a welltrodden, herringbone-patterned concrete brick roadway connecting pedestrians with The Terrace and Lambton Quay. The listing hopes to encourage greater awareness of the buried remains and history of the significant Kumutoto Pā, and of the awa running beneath their feet.

1. ‘Ngā Kina’, a sculpture by Michael Tuffery at Kumutoto Plaza.

2. The awa is now a more attractive place for the community.

When Martin Andrews went for a wander through the Woodward Street tunnel in Wellington in 2017, he had no idea that Kumutoto Awa or Kumutoto Forest existed.

Kedron Parker’s sound installation – ‘Kumutoto Stream’ –inside the public access tunnel was his first introduction to the lost streams of Wellington.

It was not until 2021 that he traced the full 1.5-kilometre length of Kumutoto Awa and found his way to the daylighted section. “It was not a healthy place; it smelled bad and was overgrown with weeds. Seeing it that way had a profound effect on me,” he says.

Martin, Project Lead for the Kumutoto Restoration Project, has a background in the social sector (Kaibosh Food Rescue) and freshwater research, so he began an in-depth study into the fresh waterways of Wellington.

Surprised by the lack of accessibility, signage and storytelling, Martin began to think about what could be done to showcase the history of past decisions to perhaps better inform those of the future.

“What if I built a self-guided audio walking tour the length of Kumutoto and talked about the history?” he says.

It is likely that Kumutoto Awa was partly culverted just 27 years after the arrival of the European settlers who purchased Port Nicholson (as Wellington Harbour was then known) for the New Zealand Company, circa 1839. Since that time, wastewater, including raw sewage, dyes, chemicals, food waste and household detergents, from the community has fed relentlessly into the Wellington stream network.

A goal of the Kumutoto Restoration Project is to test whether community engagement will lead to positive behaviour changes and more conscientious decisions about what is emptied onto streets and into gutters.

“It’s an environmental project, but with an educational front end. We will explore topics like the Port Nicholson purchase agreement and early settlement of Wellington, and its impact on our fresh water,” says Martin.

The first year’s work has been focused on creating a network with mana whenua and council, setting up a charitable trust, getting the clean-up of the awa underway, removing rubbish, and trapping predators.

“What we are building is an accessible, easy way for people to learn this history and finish at the restored awa,” he says.

The entire ecosystem for fish, kōura and insects is supported by fresh water. Predator trapping, better accessways, replanting and clearing of rubbish is making an enormous difference. Volunteers and

1. Martin Andrews, Project Lead for the Kumutoto Restoration Project.

2. A kākā perches on a branch in the forest.

3. Invertebrates temporarily removed from the awa for closer investigation.

4. Martin Andrews with visitors during the Kumutoto Community Open Day in September.

visitors are already enjoying the increased birdlife, the noisy beat of kererū wings and their creaking, branchstraining landings, the intriguing calls of sap-harvesting kākā and honey-drinking tūī and the endearing tweets of tiny pīwakawaka. A rare korimako, probably a visitor from the nearby Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne ecosanctuary, has even been recorded singing there. Year two will focus on building the walking tour and website and creating art pieces.

“We are hoping to launch the walking tour as part of the 2026 Wellington Heritage Festival,” says Martin. The work of the Kumutoto Restoration Project team is helping to share the story of Kumutoto Awa, and the organisation was the winner of the Rising Star Award at the 2025 Wellington City Community Awards. Kumutoto Forest is now rich in native plants, such as karaka, rangiora, patete and kawakawa, and small native fish like banded kōkopu, kōaro and kōura have been observed in the awa.

The track through the forest is a pleasant walk from the university to The Terrace, an opportunity to escape the bustle of city life for a few minutes and embrace the calm of nature. n

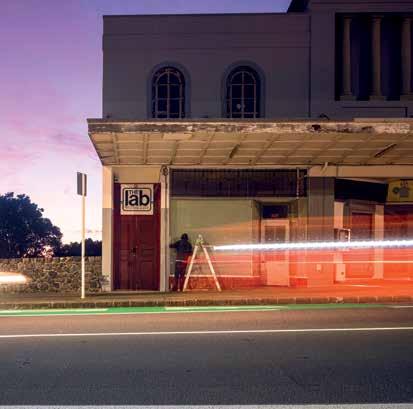

Beneath Auckland’s Crystal Palace Theatre, a former dancehall now resonates with a different kind of music

WORDS: GARETH SHUTE / IMAGERY: MIKE HEYDON

In mid-2025, The Lab recording studio held one of its loudest rehearsal sessions. Australian-born drummer Phil Rudd (AC/DC) and others including Jon Toogood (Shihad), Jennie Skulander (Devilskin), and Milan Borich (Pluto) were rehearsing for the upcoming Synthony event, named Full Metal Orchestra, to be held at Spark Arena.

Overseeing the session was inhouse engineer and studio manager Olly Harmer. His recording skills weren’t needed that day, but he adjusted the mix going to each performer’s headphones so they could hear themselves over Rudd’s powerful pounding.

For the most part, The Lab usually functions as a recording studio rather than a rehearsal space. Over the past two decades, it has been used to record parts for multi-platinum-selling albums, including The Crusader (2004) by Scribe and Passive Me, Aggressive You (2011) by The Naked and Famous. The latter saw Olly win MAINZ Best Engineer alongside Thom Powers and Aaron Short at the Aotearoa Music Awards that year.

To learn more about Crystal Palace, view our video story here: youtube.com/ HeritageNewZealand PouhereTaonga

Nonetheless, it’s hardly a surprise to find it being used for a range of musical purposes, given that this type of usage extends to its very beginning. This space below street level was first opened in 1929 as a cabaret and dancehall known as the Winter Garden, intended as an adjunct to the newly opened Crystal Palace Theatre above. The entire building is now a Category 2 historic place on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero.

Martin Jones, Senior Heritage Assessment Advisor for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, explains that music has been central to how the building has been used over the decades since.

“Silent films in the upstairs auditorium were initially accompanied by the eight-piece Crystal Palace Theatre Orchestra, as well as interspersed with live vaudeville and musical acts,” he says.

“An early concert featured the noted AustralianIrish tenor Alfred O’Shea, a popular singer of

1. Merv Thomas with the same trombone and in the same outfit as when he led the resident band at the Crystal Palace dancehall from 1958 to 1963.

2. and 3. The main room of The Lab recording studio. Its sloping ceiling is due to the cinema above.

4. A shared space where musicians can relax between takes.

5. The Merv Thomas Dixielanders in 1960. Merv is in the front row, second from the right.

6. The view from the control room of the main studio.

7. The exterior of the Crystal Palace building.

ballads, opera and Irish folk songs, who also performed at the Royal Albert Hall in London and Carnegie Hall in New York.

“In the downstairs dancehall, music could range from Rex Sayers and his Seattle Snappy Six (as on the Winter Garden’s opening night) to Royal Maka and his Syncopated Islanders ‘featuring the wizard of the electric steel [guitar] Mati Hita’ – a pioneering virtuoso who played there in 1945.”

Becoming known as the Crystal Palace dancehall, it was particularly popular between 1935 and 1953, by which time Epi Shalfoon and the Melody Boys were the resident act every Saturday night. One night, however, tragedy struck. Epi got up for a dance with his daughter Reo Shalfoon, who had become a star attraction as a singer in the group, and then suddenly collapsed and died.

Finding a replacement for such a popular band proved difficult, until promoter Phil Warren reached out to trombone player Merv Thomas. Rock ’n’ roll was just becoming popular and Merv had recorded the debut single by Johnny Devlin, but he decided that for the Crystal Palace he’d aim for a more mature crowd by playing Dixieland.

His band had a successful five-year run, which was aided by the line-up of floorshow guests they brought in, including the Howard Morrison Quartet and Merv’s regular singing partner, the jazz chanteuse Marlene Tong.

Jumping forward to recent years, Merv has visited The Lab on many occasions to take part in recording sessions. He still recognises some features from the old days – the bathrooms are still in the same location and, above them, a large section of the contemporary wallpaper still remains.

In the corner of the main studio is a soundproof booth that was once the stage. Merv can recall when it was originally built.

“We used to get complaints from the theatre upstairs. They could hear the bass during film screenings, although it was only an acoustic bass – we weren’t using an amplifier. We reasoned that it was probably because the band was on a wooden floor and it was reverberating up through the timbers, so eventually Phil decided to make a concrete stage.”

“We used to get complaints from the theatre upstairs. They could hear the bass during film screenings”

“With its history as a 1930s dancehall, it’s great that it’s still a musical space, and it’s really nice to think we are keeping that tradition alive”

While the stage was under construction, Merv and his band made light of the situation by appearing on a temporary stage dressed in workmen’s clothes. They even set up a workbench at the front and stood on it during solos. Things almost went too far, however, when pianist Clive Laurent took a hammer and nailed guitarist Jim Allison’s shoes to the ground.

When The Lab took over many decades later, they decided the solid flooring of the old stage would make it perfect for a soundproof booth, so it remains the same recognisable shape in the corner of the room. However, there were many other hurdles to overcome when turning this old nightclub into a modern recording space.

Recording studio owner Bill Lattimer had been running The Lab since 1981, moving between three different locations across the city. When the third location was in a building slated for demolition, he considered closing up for good, but he received a tip that the space below Crystal Palace was in need of a tenant. He met with the owner and was lucky enough to get the lease.

Bill enlisted his friend Brian Smith to build the new studio. The space had been through many iterations since Merv and his Dixielanders had been there, continuing as a nightclub into the 1970s, then being issued with a cabaret licence in 1973.

In 1980 it was taken over by Innovation Recording Studios, which was run by country singer/songwriter Ginny Peters and her husband Errol. They sold up in 1982 and the space was turned into a martial arts and yoga studio. Its most recent use before the arrival of The Lab was as a photography studio.

At the peak of his career, Epi Shalfoon was New Zealand’s most popular dance bandleader. Two buildings in Ōpōtiki played a crucial role in the career of Epi Shalfoon. His family were Māori-Syrian, and as a youngster he worked in his family’s general store – the Shalfoon Brothers Shop Buildings – which is now a Category 1 historic place and is run as a museum.

Next door is the De Luxe Theatre (Category 2), which opened with a performance by Epi Shalfoon and the Melody Boys in 1926. Shalfoon then used his experience in shopkeeping to open his own musical instruments store in the same complex. n