Disclaimer:

ISSN

Disclaimer:

ISSN

A pair of Chinese studies have shown evidence that children of parents living with hepatitis B (HBV) are more likely to be born with a heart defect. The studies into newborn congenital heart disease (CHD) and parental HBV status were led by Hanbin Wu and Ying Yang, both of the National Research Institute for Family Planning (NRIFP) in Beijing.

In each study—one on mothers and one on fathers living with HBV—the researchers looked at people living with HBV, but differentiated between those who had been previously infected or had been living with the virus for a while, and those who were newly infected, when the woman became pregnant.

Congenital heart disease accounts for about a third of birth defects, making it the most common congenital disease in newborns with long-term impacts on the health of the child. Studies have shown links between viral infections and the development of CHD in the foetus, and while data analyses have shown association between maternal HBV infection in early pregnancy and CHD, until now, there had been no research into links between pre-existing HBV infection and heart defects in newborns.

The NRIFP studies examined millions of people, made possible by data from a national free health service for childbearingaged women who planned to conceive in the next year, and the state’s ability to crosscheck this information with the medical histories of both members of each couple involved in the pregnancy. The National Free Preconception Checkup data from 2013 to 2019 were collected throughout mainland China.

For mothers, the first study found that approximately 0.03% of women who had no history of HBV infection, or who were newly infected with the virus, carried an infant with

congenital heart disease. This compared with 0.04% of women with a longer-term HBV infection prior to pregnancy carrying an infant with congenital heart disease. There was no noticeable difference in heart disease rates in the children of women with no HBV history compared with those of women who were newly infected.

For fathers, the second study similarly found that previous paternal HBV infection was independently associated with congenital heart disease in offspring. As in the maternal study, however, although the rates were elevated, they were not actually very high. To put these results into perspective, 0.04% of cases equates to 1 in 2,500 infants, as opposed to 1 in 3,300 where hepatitis B is not a factor. Out of China’s 9.54 million births in 2024, that translates to an additional 3,816 infants born with congenital heart disease due to parental HBV infection. In each case the study only looked at couples where one partner had HBV — the effect of both father and mother living with the virus on rates of congenital heart disease in their children remains to be seen.

The studies make no suggestions about why HBV infection in a parent might contribute to congenital heart problems in the children. This is also obviously a topic for future research. What the analysis does suggest is that HBV screening and advice for people planning on becoming parents could be very helpful, and that HBV vaccination for everyone is only to be encouraged.

READ MORE:

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/ PMC10012042

jamanetwork.com/journals/ jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2822491

Hepatitis Australia and ASHM have released a statement reminding all Australians of the importance of hepatitis B vaccinations to protect the health and wellbeing of children. The statement pointed out that since 2000, the birth-dose hepatitis B vaccine has been recommended, and is provided for free under Australia’s National Immunisation Program.

Currently, four hepatitis B vaccinations are recommended before six months of age, with the first being preferably within 24 hours of birth when medically stable. Protection against hepatitis B is almost always longlasting, and the birth-dose is tolerated very well by newborn babies.

“Birth-dose vaccination is one of the strongest and most effective tools we have to prevent babies and children from developing chronic hepatitis B. Hepatitis B can have profound lifelong health impacts and increases the risk of potentially fatal liver cancer,” said Lucy Clynes, CEO of Hepatitis Australia.

“The risk of developing chronic hepatitis B is around 90% for babies who are exposed to hepatitis B. Any unnecessary delay to

childhood hepatitis B vaccination creates an unacceptable and avoidable risk of chronic hepatitis B.”

Under the childhood vaccination program, 93% of one-year-olds have been immunised against hepatitis B as of June 2025.

Childhood hepatitis B vaccination has supported a 60% decline in hepatitis B notifications in Australia in people aged under 20 between 2014 and 2023.

“We know that childhood vaccinations work,” said Alexis Apostolellis, CEO of ASHM. “Australia has shown great progress towards the elimination of hepatitis B transmission, particularly in children and adolescents. It is vital that all healthcare professionals continue to follow evidence-based clinical guidance in their practice.”

Healthcare professionals can view the latest recommended hepatitis B immunisation schedule for children, including state and territory-specific guidance, in the National Immunisation Program (NIP) Schedule.

Further evidence-based guidance around hepatitis B prevention and vaccinations can be found on ASHM’s B Positive web portal: hepatitisb.org.au/primary-prevention-ofhepatitis-b-virus-infection.

Hepatitis B is a virus which can lead to acute or chronic hepatitis B conditions, with the latter being associated with increased risk of liver damage and liver cancer. Anyone seeking further information about hepatitis B, including vaccination, can call HepLink on 1800 437 222. READ MORE:

In Australia, just under 300,000 people live with chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis C, liver infections caused by the hepatitis B and C viruses.1 If the infections become chronic, they may cause liver disease and liver cancer, which has the fastest increasing mortality rate in Australia compared to other cancers.2

Hepatitis B and C are often referred to as ‘silent killers’, due to the slow and asymptomatic disease progression, and are an overlooked public health challenge. The burden of these infections falls hardest on marginalised and underserved communities: people from migrant and refugee backgrounds, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people in prison settings, and those who currently or previously injected drugs.3 These communities face systemic barriers to accessing health care and commonly report adverse exchanges with health services, leading to prolonged suffering, delayed treatment, and ill health.4

As an educator, I use my platform not only to build clinical confidence but to emphasise that hepatitis B and C are not just liver issues, they are issues of equity and social justice. In 2016, Australia became one of the first countries in the world to commit to the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030. Elimination targets include increasing diagnosis, improving engagement in care and treatment rates

for affected communities, and reducing hepatitis-related mortality. This article highlights that nurses and midwives play a critical, yet underutilised, role in making hepatitis B and C elimination a reality.

In 2023, an estimated 220,000 people in Australia were living with chronic hepatitis B.5 Globally, hepatitis B is most often transmitted from mother to child during birth. It is spread through contact with blood and body fluids, which can also occur through sexual contact, unsafe injections, unscreened blood transfusions, or sharing of injecting equipment.6 More than 70% of people living with hepatitis B in Australia are from migrant or refugee backgrounds, contracted at birth or in early childhood. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are also disproportionately affected by hepatitis B. While hepatitis B is vaccine-preventable and manageable with monitoring and medication, engagement in health care remains poor. Alarmingly, 31% of people living with hepatitis B remain undiagnosed. Of those diagnosed, many face ongoing barriers to accessing care or understanding the importance of monitoring and treatment. As a result, only 24% of people with chronic hepatitis B are receiving regular care.

Hepatitis C affects around 69,000 Australians and primarily impacts people who inject drugs. Unlike hepatitis B, hepatitis C can be cured. Since 2016, more than 100,000 Australians have been successfully treated and cured with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). DAAs are safe, all oral medications that eliminate the virus in 98% of people after 8-12 weeks of treatment. Despite this, hepatitis C elimination targets

are slipping. Reaching priority populations remains challenging due to stigma, drug criminalisation, housing insecurity, and health system gaps.

But statistics only tell part of the story. Hepatitis B and C are deeply personal conditions, often carried in silence by people who may not even know they are infected. Many live with anxiety, uncertain futures, and/or shame. For culturally and linguistically diverse communities, hepatitis B is often referred to as a ‘family disease’, passed silently between generations. People born overseas face broader challenges such as navigating the complex Australian healthcare system, difficulty accessing education, employment or housing, and a lack of social connectedness that compound health inequities.

For people living with or at risk of hepatitis C, particularly those who use drugs, stigma is pervasive. Health services may be experienced as inflexible, unwelcoming, or unaffordable. Many report feeling dehumanised when trying to access care.

These aren’t just abstract problems, they’re personal, painful, and ongoing.

For example, Sue was called by the dental clinic and informed she had been moved from first on the list to last on the day, with the receptionist coolly stating this was “clinic policy for infection control.”

Matt, who was recently removed from a surgery waitlist altogether at a busy Melbourne hospital, was told to rebook only after completing hepatitis C treatment. No referral or follow-up support was provided.

In one case, an emergency department doctor expressed surprise when Tom declined an 8-week treatment course that would cure his hepatitis C. Tom later explained to his trusted alcohol and other drug nurse practitioner that 15 years ago, while in prison, he was held down three times a week for six months to receive interferon

injections he never consented to, medication that made him sicker than the virus itself.

Stigma also seeps into assumptions. A friend and colleague working in hepatitis C advocacy was congratulated by a GP on having a job, with the doctor assuming because she uses drugs that she wouldn’t be employed.

These experiences show how deep-rooted and damaging stigma and discrimination can be, both systemically and interpersonally. They erode trust, discourage engagement in care, and make people feel unsafe in health settings.

Nurses and midwives are uniquely positioned to change this trajectory. Nurses and midwives care for patients holistically – not as a collection of diseases or symptoms, but as whole people shaped by their lived experience. We also act as trusted advocates, ensuring our patient’s wishes and best interests are upheld, their voices are heard, and their dignity is maintained throughout their healthcare journey.

It needs to be acknowledged that nurses and midwives face challenges in providing holistic hepatitis care, usually unintentionally. Time pressures, high workloads, limited training on viral hepatitis, and a lack of confidence can all act as barriers.7 That’s why continued education, support, and systemic resourcing are essential. As an educator, one of my goals is to empower nurses and midwives with the tools they need to feel capable and confident to care for people with hepatitis B and/or C.

The good news is, you don’t need to be a specialist to make a meaningful difference. Nurses and midwives already have the skills to raise awareness, guide patients, and support care across all settings. In clinics, hospital wards, emergency departments, community health centres, and remote area posts, we are often the first point of meaningful contact for people affected by hepatitis.

For example, in maternity care, midwives may be the first to identify a pregnant person’s hepatitis B or C status and help prevent mother-to-child transmission, including through promoting the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccination. Maternal and child health nurses support new parents to continue the hepatitis B vaccine schedule. In primary health settings, nurses frequently provide screening, vaccinations, treatment support, and referrals to local services. In emergency departments, we can offer opportunistic testing and link clients to social or harm reduction services. In remote clinics, particularly in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, nurses play a vital role in closing the gap.

Perhaps most importantly, nurses and midwives are in a powerful position to challenge stigma, the biggest barrier to achieving hepatitis elimination. We must refrain from making assumptions, ensure our care is welcoming, respectful and non-judgemental, and normalise difficult conversations. This was summed up powerfully by Peta Gava, a Lived Experience Peer Worker at Peer Based Harm Reduction WA, who spoke at the 15th Australasian Viral Hepatitis Conference (6–8 August 2025, Melbourne): “When people have experienced healthcare that is respectful, affordable, and accessible, they remain engaged and present —not just in times of crisis”.8

Hepatitis B and C may be silent, but as nurses and midwives, we cannot afford to be. Your voice matters. We are advocates,

educators, and healers. Voices for those too often unheard. Every test you offer, every vaccine you administer, every moment of compassionate, non-judgemental care contributes to better outcomes.

The type of care you provide can be the difference between someone seeking help or staying silent. As nurses and midwives, we are not just witnesses to health inequity. We are agents of change.

Let’s rise to this challenge.

Mieken Grant is a Victorian Viral Hepatitis Educator | Clinical Nurse Consultant at St Vincent’s in Melbourne. This article was originally published in the Australian Nursing & Midwifery Journal, and is reprinted with permission.

1. Department of Health and Aged Care. (2023). National Hepatitis B and C Strategies 2023–2030. Australian Government. www.health.gov.au

2. AIHW. (2022). Cancer in Australia 2022. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. www.aihw.gov.au/ reports/cancer/cancer-in-australia-2022

3. Kirby Institute. (2022). National surveillance report on blood-borne viruses and STIs in Australia 2022 UNSW Sydney. kirby.unsw.edu.au

4. Burnet Institute. (2021). Stigma and viral hepatitis in Australia. www.burnet.edu.au

5. MacLachlan, J., Mondel, T., Purcell, D., & Cowie, B. (2025). Hepatitis B in Australia: Monitoring and surveillance report 2023. Doherty Institute.

6. World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Hepatitis B and C: Key facts. www.who.int

7. Wallace, J., Scott, N., Draper, B., & Pedrana, A. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to nurse-led hepatitis care: A review. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 28(3), 210–218.

8. Gava, P. (2025, August 6–8). The elimination of hepatitis C “by 2030” is a sector goal, not a community one. [Conference presentation]. 15th Australasian Viral Hepatitis Conference, Melbourne, Australia

Flinders Medical Centre hepatology nurses are urging people to get tested for viral hepatitis. Throwing their support behind Hepatitis SA’s World Hepatitis Day green T-shirts activity, the nurses put paint to fabric to produce wearable messages to spread the word that hepatitis testing saves lives.

Hepatology Nurse Consultants Rachel Wundke, Rosalie Altus and Kylie Bragg were proudly wearing the green shirts with messages telling people that viral hepatitis increases liver cancer, to ask their GP about testing, or to speak to them how to go about it. One message pointed out that early detection is key to better outcomes.

Rachel, the mover behind the fun but meaningful project, was one of the first to jump at the Hepatitis SA offer of green T-shirts and white fabric paint to decorate them, and wear them for the WHD campaign. The outcome stood out among the many other shirts painted and decorated during the lead up to World Hepatitis Day.

Green is the colour of the global NOhep movement and central to the Australia Glow Green WHD activity where landmarks around

the country are lit green to draw attention to the global and national campaign to eliminate viral hepatitis. In South Australia, the Adelaide Oval, Footbridge, Parliament House and the Elemental in Victor Harbor were all glowing green on 28 July, along with the Hepatitis SA office and car park.

Support for the WHD campaign also came from Viral Hepatitis Nurses from the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, who were in attendance all day at shopping centres (Hollywood Plaza in Salisbury Downs and Arndale Shopping Centre at Kilkenny), providing free liver fibroscans to members of the public. The nurses were able to explain scan results and provide referrals for follow up if needed.

The clinics were organised by Hepatitis SA in partnership with Relationships Australia SA (RASA) and the Central Adelaide Local Health Network (CALHN).

World Hepatitis Day is an annual event to raise awareness about viral hepatitis and its impact on public health. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C are the leading causes of liver cancer. In Australia liver cancer is the fastest growing cause of cancer related deaths and

Opposite: Hepatology nurses Kylie (at right in first picture), Rachel (centre) and Rosalie with their important World Hepatitis Day messages [supplied by R Wundke]

the primary cause of liver cancer is viral hepatitis.

While hepatitis C numbers are reducing due to new cures made available on the PBS in 2016, re-infection is occurring due to lack of transmission reduction programs in prisons, and remarkably one fifth of people with chronic hepatitis C are undiagnosed.

There is a vaccine for hepatitis B but people 25 and over i.e. those born before the introduction of hepatitis B vaccination for newborns in Australia, would not have the benefit of that protection and may have been at risk of infection. Furthermore, hepatitis B numbers are increasing, going from 200,000 last year to 220,000 this year: an increase of 20,000 in 12 months, much of it due to migration.

Of great concern is the fact that about one in three people with chronic hepatitis B are undiagnosed. There is as yet no cure for hepatitis B but there is treatment to keep the virus under control. As such, on-going monitoring and care is vital to minimise adverse outcomes. Unfortunately, about half of Australians with chronic hepatitis B have not received any care at all in the last 10 years!

Australia has signed up the the World Health Organization’s target of eliminating hepatitis B and hepatitis C by 2030. To achieve that goal, it is important that we act to increase testing to find undiagnosed cases and facilitate access to treatment and care.

SA Health Viral Hepatitis Nurse, Jeff, explains fibroscan results to Kath who had just got a check.

As the coronavirus spread globally in 2020, and people all around the world began to be uncomfortably familiar with RAT tests and PCR tests, NSW historian Michelle Bootcov realised her in-progress PhD on the history of hepatitis B was also a history of the medical discoveries underlying the world’s ability to respond to the pandemic.

“Both the rapid antigen tests (RAT tests) and the variant sequence analysis (PCR tests) that became common knowledge to the general public during COVID, had historical antecedents in hepatitis B research of the 1960s to 1990s,” explained Dr Bootcov, who received her doctorate from the University of NSW in 2024.

Hepatitis B was a medical emergency in the 1960s, because the increasing use of blood transfusion was accompanied by an increasing incidence of post-transfusion hepatitis. “Although the incidence was low in Australia, elsewhere it was as high as 20% to

50%, particularly for multi-unit transfusions from paid donors” Dr Bootcov said.

“This was especially problematic because HBV infection is frequently asymptomatic, and at that time there was no way to rapidly detect the virus in donated blood, and thus prevent transmission.

“In fact, there was no way to rapidly diagnose any viral infection. Laboratory diagnosis took so long that the saying was that patients were dead or discharged from hospital before the results came back.”

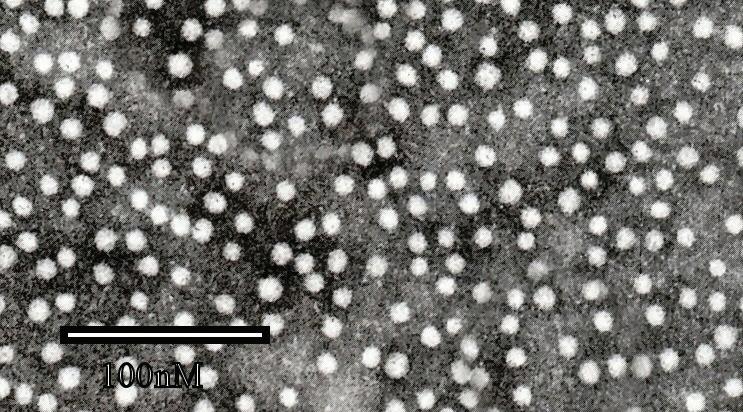

Without a detection test for the virus, the extent of hepatitis B infection was unknown, and only identified in asymptomatic donors when their blood recipients developed posttransfusion hepatitis, at which point it was obviously far too late to prevent transmission. After decades of futile research by virologists and haematologists, in the late 1960s there was a breakthrough: a test that could detect an antigen associated with the virus. An

antigen is a substance that causes the body to make an immune response against it. The presence of one particular antigen in blood reliably indicated hepatitis B infection, and improvements to those antigen testing techniques soon reduced the time to get test results to just a few hours. This was an essential requirement for the use of donor blood products. And this test was the first rapid antigen test for mass screening for a virus anywhere in the world.

The antigen in those first hepatitis tests was a protein on the surface of the hepatitis B virus, and initially it was called “the Australia antigen” because the blood in which it was discovered came from an Indigenous community in Central Australia.

“The Australia antigen was serendipitously identified in the mid-1960s through genetics enquiry. Within a few years, following a series of research twists and turns and two hepatitis B transmission events that caught the attention of alert scientists, it became clear that the Australia antigen was not the product of a human gene, it was a viral protein,” said Dr Bootcov.

Transmission electron micrograph of Hepatitis B virus surface antigen, or “the Australia antigen”.

The method used in genetics to identify the Australia antigen became the method by which hepatitis B infection could be detected rapidly in donor blood. “This discovery transformed blood transfusion services’ management of donor blood, and the high demand for those tests fuelled

the establishment of the viral diagnostics industry,” explained Dr Bootcov. Reliable testing also revealed the true and frightening extent of hepatitis B infection. In some countries it was hyper-endemic.

These improvements in blood donor testing paved the way for blood management when HIV/AIDS emerged in the 1980s.

Hepatitis B was also amongst the first viruses to be fully sequenced and its variants analysed. This is a type of analysis that became all too familiar across the world during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Delta, Omicron, and other variants were discovered, traced and tracked.

“Looking back to December 2019 and the emergence of an unfamiliar pneumonia in Wuhan, China, it is amazing to recall the speed with which the coronavirus was isolated, and its genome fully sequenced and published,” noted Dr Bootcov.

“Soon rapid antigen tests (RATs) could be conducted at home within 15 minutes, [and] PCR and sequencing was so fast that a result could be texted within hours, and viral variant transmission tracked in real time. Few paused to marvel at the magnitude of that scientific possibility!”

“It had come to be expected. And much of it was thanks to the technologies that emerged through research that began with the hepatitis B virus and its Australia antigen.”

The blood–brain barrier is a hugely effective “wall” that protects the brain from pathogens in a person’s body. It’s like a highly selective, very fine sieve that allows vital nutrients and other chemicals that the brain needs to be taken from the blood supply, while keeping out a vast number of dangerous molecules and diseases.

Past research has suggested that psychiatric illnesses such as major depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia may be sometimes caused or exacerbated by viral infections, but scientists have not been able to find any direct traces of these viruses in the human brain. Some experts have suggested that perhaps this is because the viruses may not attack the brain directly, but may instead target the brain’s lining, or meninges.

A team of medical scientists at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center have recently published a study, in the Nature journal Translational Psychiatry, showing that they have evidence of hepatitis C in the human brain’s choroid plexus, a collection of cells that make up the lining of the fluid-filled cavities, or ventricles, which produce the

Cross-section of the human brain, showing the Choroid Plexus vesicles which are filled with cerebrospinal fluid

cerebrospinal fluid that protects the brain and spinal cord.

This fits with previous studies which have found that there are much higher than expected rates of hepatitis C infection in people living with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. The John Hopkins research team, led by neuroscientist Dr Sarven Sabunciyan, suggests that it may be the HCV infections which are associated with the cause of the psychological illnesses, rather than more commonly blamed factors like injecting drug use.

Between 150,000 and 200,000 Australians are living with schizophrenia, while approximately 2.2% of Australians live with a form of bipolar disorder (1 in 50 adult Australians experience bipolar disorder each year).

For the study, the team first analysed choroid plexus samples from postmortem brains of individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression, as well as unaffected controls. The samples were obtained from the Stanley Medical Research Institute collection, a repository of brain tissue donated after death from people with mental health disorders.

Since past research had failed to find viruses inside the brain tissue itself, the researchers specifically focused on the choroid plexus, and their analysis revealed the presence of various viruses there. The researchers found that more viruses were present in samples from people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. But, unlike other viruses, HCV was only present in the brain lining of people who had schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Notably, the virus was not present in some individuals who were known to have been living with chronic HCV, suggesting that the infection does not automatically spread to the brain lining in every infected person.

During the next phase of the study, the research team analysed a large sample of electronic health records, and found that HCV was documented in 3.6% of those with schizophrenia and 3.9% of those with bipolar disorder—almost double that of those with

major depression (1.8%), and approximately seven times that in the control population (0.5%). The researchers say while illicit drug use is common among people with all three disorders, drug use did not account for the higher prevalence of HCV in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder compared with major depression.

The team also looked for viral RNA in sequencing data from the hippocampus, a region of the brain that supports learning, memory and other functions, of subjects identified to have HCV, and found that the virus was absent in this tissue despite being present in the brain lining. However, the presence of HCV in the brain lining altered gene expression in the hippocampus, providing a possible mechanism by which an infection in the lining can affect brain functions and behavior without the virus itself penetrating into the brain.

While the researchers caution that their study does not mean that everyone with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder has an HCV infection, they believe their findings provide compelling support for the existence of the virus in the choroid plexus, and that the implications that come from this are serious.

“Our findings show that it’s possible that some people may be having psychiatric symptoms because they have an infection,”

Dr Sarven Sabunciyan explained, “and since the hepatitis C infection is treatable, it might be possible for these patients to be treated with antiviral drugs and not have to deal with psychiatric symptoms.”

Dr Sabunciyan now wants to work with mental health professionals to screen for HCV in people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. If treating hepatitis C in these patients also eases or cures their psychiatric issues, this would be an amazing extra ‘side-effect’ of the extremely effective hep C cures currently available, and a powerful new reason for everyone to get tested and treated today!

READ MORE: nature.com/articles/s41398-025-03387-3

Findings from the Australian Needle and Syringe Program (NSP) Survey 30-year National Data Report shows highly significant reductions in hepatitis C infections and high levels of treatment and cure among NSP clients.

The report was released to mark the project’s 30 year anniversary. Conducted annually since 1995, the Australian NSP survey served as a strategic early-warning system designed to monitor blood borne viral infections, injecting and sexual health.

• The proportion of respondents who had been exposed to hepatitis C, measured by HCV antibody status, fluctuated over the last 30 years, but showed an overall decline remaining under 50% since 2017 and was 39% in 2024.

• Among new initiates to injecting, hepatitis C antibody prevalence was highest in the period following changes to heroin markets, with prevalence of 38% observed in 2002 but overall, HCV prevalence among new initiates declined from 22% in 1995 to 2% in 2024, a finding that supports a decline in hepatitis C infections among people who inject drugs.

• Among respondents assessed as eligible for hepatitis C treatment, those reporting ever having treatment remained low at around 10% between 2008 and 2015 but following introduction of direct-acting antivirals in 2016, treatment rate reported increased substantially from 11% in 2015 to 78% in 2024. In South Australia the treatment rate rose from 16% in 2015 to 84% in 2024.

• Testing for HCV RNA among respondents was first conducted in 2015 when 51% tested positive. This declined to 8% in

2024, suggesting a high level of treatment and cure among PWID following the introduction of the new treatments.

• The proportion of respondents with no evidence of exposure to hepatitis C increased from 43% in 2015 to 61% in 2024.

• The proportion of respondents with cleared infection (HCV antibody positive and HCV RNA negative) increased from 6% in 2015 to 31% in 2024 and the proportion of respondents with active hepatitis C infection (HCV RNA positive) declined substantially, from 51% in 2015 to 8% in 2024. In South Australia, the rate declined from 49% in 2015 to 6% in 2024.

In SA, two NSP services—Noarlunga Primary Health and Port Adelaide NSP—participated in the survey for 26 and 24 years respectively. Other participating sites included SAVIVE Shopfront/Anglicare Salisbury (1995 to 2018) and Nunkuwarrin Yunti, an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. In the first three years, sample sizes were less than 60 respondents but that subsequently increased to between 200 and 355. In 2024, there were 232 respondents.

One SAhrps worker, commenting on the decline in hepatitis C prevalence among respondents between 2015 and 2024 said, “This is an excellent result we should all be super proud of having a part in achieving. Still more work to do but that’s an incredible drop.”

• The median age of respondents has increased significantly from 27 years in 1995 to 45 years in 2024. The proportion of respondents aged 45 years or older

increased from 2% in 1995 to 52% in 2024 and the proportion of young people aged less than 25 years declined from a high of 36% in 1997 and 1998 to between 2% and 3% from 2020 to 2024. This suggests an aging cohort of people accessing NSP in Australia.

• Since 2005, methamphetamine has been the most commonly reported drug last injected, and was reported by just over half (52%) of all respondents in 2024.

• The proportion of respondents who reported last injecting pharmaceutical opioids increased from 3% in 1995 to 16% in 2010. Since 2010, prevalence has declined, with 3% of respondents last injecting this class of drugs in 2024.

In releasing the report, the ANSPS acknowledged the 65,000 occasions NSP clients across Australia had participated in the survey since its inception in 1995, as well as the ongoing support and assistance from staff and management at participating NSP services.

The report further acknowledged the original investigators and steering committee responsible for developing the survey methodology and the dedication and vision of the founding members of the project and in particular the late Dr Margaret MacDonald who was responsible for the development and conduct of the ANSPS from 1995 until 2003.

READ MORE: www.kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/ files/documents/Australian-NSP-Surveynational-data-report_1995-2024.pdf

In early September, Uniting Communities, and its partner agencies and supporters, celebrated the opening of a new ground floor space within the Uniting Communities U City site in Franklin Street. This houses the relocated NSP and a new service, UConnect, that undertakes client intake and assessment. Until being relocated, the NSP was on level 1 and accessible only by stairs or elevator, which often presented a barrier for people wanting to use it. In addition to being on the ground floor, the NSP is now directly accessible from Pitt Street.

Speakers at the opening included our own SAhrps Sessional Peer, Penni, who talked about peer education and how having peers/ people with lived experience engaging with service users can enhance services and increase access for the most marginalised. An opening of a new service is not complete without a ribbon cutting ceremony, and Jeremy Brown, Chief Executive of Uniting Communities performed this task, with support from Penni.

Uniting Communities: UCity NSP 8 Pitt Street, Adelaide Open 10am–4pm Mon–Fri

The long-awaited directacting antivirals have had significant benefits, with those cured facing much better outcomes than people who have not been treated.

However, a number of challenges threaten to undermine the individual and public health gains provided by DAAs:

Overall mortality is higher for people who have been cured when compared to the general population.

Stigma remains a barrier to healthcare and social inclusion, either because of misunderstandings about antibody positive status or because of the association of hepatitis C with injecting drug use.

Maintaining cure is an ongoing challenge for people who live with the same risks that led to their initial infection.

The articles in this alert highlight the need for continued care after cure and include calls to expand the focus of elimination efforts to include the overall healthcare needs and human rights of people affected by hepatitis C.

Our findings bring into focus the importance of establishing robust care and harm reduction pathways after successful HCV treatment. As we move towards HCV elimination, treatment programmes must strike the right balance between treating HCV and treating the patient.*

*Hamill V, Wong S, Benselin J, Krajden M, Hayes P C, Mutimer D et al. Mortality rates among patients successfully treated for hepatitis C in the era of interferonfree antivirals: population based cohort study BMJ 2023; 382 :e074001 doi:10.1136/bmj-2022074001

Australia’s national hepatitis C strategy must address post-cure lives

Melbourne, Gender Law and Drugs (GLaD), 2022. 4p.

Identifies 3 important issues for the next strategy: stigma and discrimination including persistence after cure; more careful language, in acknowledgement of the challenges of post-cure life; and the approach to human rights. bit.ly/postcure

Mortality rates among patients successfully treated for hepatitis C in the era of interferon-free antivirals: population based cohort study

London, BMJ Group, 2023. 13p.

Mortality rates among people treated are high compared with the general population. Highlights the need for continued support after treatment to maximise the impact of DAAs. bit.ly/bmjcohort

Liver cancer risk and changes in lifestyle habits after successful hepatitis C virus therapy post-DAA HCV therapy

London, Springer Nature, 2025. 10p.

The eradication of the Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) reduces the risk of liver cancer (LC), but lifestyle changes after cure may counterbalance its benefit.

bit.ly/postdaa

Life after hepatitis C treatment : health, wellbeing and the future

Melbourne, ARCSHS, 2022. 18p.

Lived experiences of treatment for hepatitis C in Australia.Concludes with recommendations to improve support and care following

hepatitis C treatment and cure. bit.ly/lifeafterc

The time of cure: hepatitis C treatment and the matter of reinfection among people who inject drugs

London, Taylor and Francis Online, 2024.15p.

Hep C treatment and the complexities that endure for many post-cure: “We conclude that our understanding of reinfection needs to move beyond its current, narrow biomedical conception ... and incorporate complexity in practice.”

bit.ly/timeofcure

Monitoring hepatitis C elimination among people who inject drugs: a broader approach is required

London, Elsevier, 2025.

Argues that the overall goal of hepatitis C elimination for PWID should be improved

QOL and enhanced access to high-quality, non-judgmental healthcare and prevention services, resulting in reductions in morbidity and mortality.

bit.ly/monitorelim

Hepatitis SA provides free information and education on viral hepatitis, and support to people living with viral hepatitis.

Postal Address:

Kaurna Country PO Box 782

Kent Town 5071

(08) 8362 8443 1800 437 222

www.hepsa.asn.au

Community News: hepsa.asn.au/ communitynews

Library: hepsa.asn.au/library

@HepatitisSA

@hepatitissa.asn.au.bsky.social

Resources: issuu.com/hepccsa

Email: admin@hepatitissa.asn.au

Free hepatitis A, B and C information, confidential and non-judgemental support, referrals and printed resources.

We can help. Talk to us. Call or web chat 9am–5pm, Mon–Fri

HEPATITIS SA BOARD

Chair

Lindy Brinkworth

Vice Chair

Bill Gaston

Secretary

Sharon Eves

Treasurer

Michael Larkin

Ordinary Members

Janice Scott

Memoona Rafique

Lucy Ralton

Tamara Shipley

Kerry Paterson (CEO)

Hepatitis SA has a wide range of hepatitis B and hepatitis C publications which are distributed free of charge to anyone in South Australia.

To browse our collection and place your orders, go to hepsa.asn.au/orders or scan the QR code below:

Viral Hepatitis Nurses are nurse consultants who work with patients in the community, general practice or hospital setting. They provide a link between public hospital specialist services and general practice, and give specialised support to general practitioners (GPs) to assist in the management of patients with hepatitis B or hepatitis C. With advanced knowledge and skills in testing, management, and treatment of viral hepatitis, they assist with the management of patients on antiviral medications and work in shared care arrangements with GPs who are experienced in prescribing medications for hepatitis C or accredited to prescribe section 100 medications for hepatitis B. They can be contacted directly by patients or their GPs:

CENTRAL ADELAIDE LOCAL HEALTH NETWORK

Queen Elizabeth Hospital

Phone: 0423 782 415, 0466 851 759 or 0401 717 953

Royal Adelaide Hospital

Phone: 0401 125 361 or (08) 7074 2194

Specialist Treatment Clinics

NORTHERN ADELAIDE LOCAL HEALTH NETWORK

Phone: 0401 717 971 or 0413 285 476

SOUTHERN ADELAIDE LOCAL HEALTH NETWORK

Phone: 0466 777 876 or 0466 777 873

Office: (08) 8204 6324

Subsidised treatment for hepatitis B and C are provided by specialists at the major hospitals. You will need a referral from your GP. However, you can call the hospitals and speak to the nurses to get information about treatment and what you need for your referral.

• Flinders Medical Centre Gastroenterology & Hepatology Unit: call 8204 6324

• Queen Elizabeth Hospital: call 8222 6000 and ask to speak a viral hepatitis nurse

• Royal Adelaide Hospital Viral Hepatitis Unit: call Anton on 0401 125 361

• Lyell McEwin Hospital: call Bin on 0401 717 971

Visit hepsa.asn.au: no need to log in, lots of info & updates

Visit hepsa.asn.au - no need to log in, lots of info & pdates

Follow Community News online: hepsa.asn.au/communitynews

Follo the HepSAY blog - hepsa.asn.a /blog

Order print resources at hepsa.asn.au/orders

SMS/WeChat us on 0403 648 348

Order print resources - hepsa.asn.a /orders/ Follo s on T i er @hep_sa or Facebook @Hepa sSA

Follow us on social: Bluesky @hepatitissa.asn.au.bsky.social or Facebook @HepatitisSA

Full range of syringes and needles. Water and filters also available in limited quantities for free.

Hepatitis B and Baby