Contentious Compliance: Dissent And Repression Under International Human Rights Law Courtenay R. Conrad

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/contentious-compliance-dissent-and-repression-unde r-international-human-rights-law-courtenay-r-conrad/

ContentiousCompliance

ContentiousCompliance

DissentandRepressionunder

InternationalHumanRightsLaw

CourtenayR.Conrad

AssociateProfessorofPoliticalScience

UniversityofCalifornia,Merced

EmilyHenckenRitter

AssociateProfessorofPoliticalScience

VanderbiltUniversity

1

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford.Itfurthers theUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship,andeducation bypublishingworldwide.OxfordisaregisteredtrademarkofOxfordUniversity PressintheUKandincertainothercountries.

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY,UnitedStatesofAmerica.

©OxfordUniversityPress

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereproduction rightsorganization.Inquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer.

AnOnlineAppendixisavailableathttps://dataverse.harvard.edu/

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

Names:Conrad,CourtenayR.,author. | Ritter,EmilyHencken,author.

Title:Contentiouscompliance:dissentandrepressionunderinternational humanrightslaw/CourtenayR.Conrad,EmilyHenckenRitter.

Description:Oxford[UK];NewYork,NY:OxfordUniversityPress,[] Identifiers:LCCN | ISBN(pbk.) |

ISBN(hardcover)

Subjects:LCSH:Internationallawandhumanrights. | Humanrights. | Treaties. | Politicalpersecution. | Dissenters—Legalstatus,laws,etc. | Government,Resistanceto. | Protestmovements.

Classification:LCCKZ.C | DDC./–dc LCrecordavailableathttps://lccn.loc.gov/

PaperbackprintedbyWebCom,Inc.,Canada

HardbackprintedbyBridgeportNationalBindery,Inc.,UnitedStatesofAmerica

1

DedicatedtoWillH.Moore

Acknowledgments xi 1.DoHumanRightsTreatiesProtectRights? 1 1.1.TreatiesandtheIncentivetoViolateHumanRights 5 1.2.ContentiousCompliance:TheArgument 7 1.3.ContributionstoScienceandPractice 12 1.3.1.HumanRightsTreatiesandRepression 17 1.3.2.HumanRightsTreatiesandDissent 20 1.3.3.HumanRightsTreatiesandtheLaw 23 1.3.4.HumanRightsTreatiesandAdvocacy 25 1.4.OrganizationoftheBook 26 PARTI:ATheoryofConflictandTreatyConstraint 2.AModelofConflictandConstraint 31 2.1.Institutions,Conflict,andDecision-Making 34 2.2.AModelofTreatyObligations,Courts,andConflict 36 2.2.1.TheEffectsandCostsofRepressionandDissent 39 2.2.2.TheExpectedValueofPowerandtheConsequencesof PolicyControl 45 2.2.3.InstitutionalConsequencesforGovernment Repression 49 2.2.4.SummaryofTheoreticalAssumptions 56 2.3.EquilibriumBehavior 57 2.4.Appendix1:ProofsofFormalTheory 59 2.4.1.ProofofEquilibriumBehavior 59 2.4.2.ComparativeStatics 60 3.EmpiricalImplicationsofTreatyEffectsonConflict 63 3.1.EstablishingtheBaseline:ConflictBehaviorsintheAbsenceofa Treaty 64 3.2.AFormalComparison:ConflictBehaviorsUnderaHumanRights Treaty 70 (vii)

CONTENTS

(viii) Contents 3.3.UnderstandingTreatyEffects 73 3.4.CommitmenttoHumanRightsTreatiesinExpectationof Constraint 78 3.5.SummarizingtheTheory 83 PARTII:AnEmpiricalInvestigationofConflict&TreatyConstraint 4.AnalyzingtheEffectofTreatiesonRepressionandDissent 87 4.1.MovingfromConceptstoMeasures 89 4.1.1.InternationalHumanRightsTreatyObligation 90 4.1.2.GovernmentRepression 93 4.1.3.MobilizedDissent 99 4.1.4.ExpectedValueofLeaderRetention 101 4.1.5.ProbabilityofDomesticLitigationConsequences 104 4.1.6.OperationalHypotheses 106 4.2.StructuralRequirementsofEmpiricalAnalysis 107 4.2.1.CounterfactualComparison 107 4.2.2.SelectionBias 110 4.2.3.TheSolution:ATwo-StageTreatmentEstimator 114 4.2.4.EstimatingSimultaneousConflictBehaviors 117 5.SubstantiveEmpiricalResults:GovernmentRepression 119 5.1.PresentingResultsBasedonCounterfactuals 121 5.2.EffectofCATObligationonGovernmentRepression 125 5.2.1.AdditionalTest:EffectofOPCATonGovernment Torture 129 5.3.EffectofICCPRObligationonGovernmentRepression 133 5.3.1.AdditionalTest:EffectofICCPRonPolitical Imprisonment 136 5.4.EffectofCEDAWObligationonGovernmentRepression 139 5.4.1.AdditionalTest:EffectofCEDAWonWomen’sSocial Rights 142 5.5.SummaryofFindings:GovernmentRepression 145 5.6.Appendix2:EmpiricalResultsforGovernmentRepression 148 6.SubstantiveEmpiricalResults:MobilizedDissent 151 6.1.LevelsofAnalysis&theStudyofMobilizedDissent 154 6.2.EffectofCATObligationonMobilizedDissent 157 6.2.1.AdditionalTest:AlternativeMeasureofLeader Security 162 6.3.EffectofICCPRObligationonMobilizedDissent 166 6.3.1.AdditionalTest:AlternativeExclusionRestriction Specification 170

Contents(ix) 6.4.EffectofCEDAWObligationonMobilizedDissent 174 6.4.1.AdditionalTest:AlternativeMeasureofMobilized Dissent 176 6.5.SummaryofFindings:MobilizedDissent 181 6.6.Appendix3:EmpiricalResultsforMobilizedDissent 183 PARTIII:Conclusion 7.Conclusion:HumanRightsTreaties(Sometimes)ProtectRights 193 7.1.A(More)CompletePictureofDomesticConflict 196 7.1.1.HumanRightsTreatiesandConflict 197 7.1.2.TreatyConstraintDespiteSelection 199 7.2.TheEffectofTreatyStatusonPopularExpectations 205 7.2.1.TheConditioningEffectofPoliticalSurvival 209 7.3.ExtendingtheTheory 214 7.3.1.VarianceinTreatyEffectiveness 217 7.3.2.OtherDomesticInstitutionalConstraints 218 7.3.3.OtherInternationalInstitutionalConstraints 220 7.4.AFinalNoteonPolicyPrescriptions 221 PARTIV:Appendix AppendixtoChapters4,5,6:SummaryofOnlineRobustness Checks 227 A4.1.GovernmentRepression 227 A4.2.MobilizedDissent 229 Bibliography 231 Index 251

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Theprogressofsciencereliesoncommunity.Webuildonthecareful workofotherscholars.Wepresentourresearchpublicly,openingitto critique,suggestion,andimprovement.Wedependonorganizationsand universitiesforthetime,space,andresourcestothink,process,write,fail, andsucceed.Weleanonacommunityofcolleagues—fromgraduateschool advisorstoseniorcolleagues,fromfriendsinthedisciplinetoeditorswho supporttheresearch—foradviceandencouragement.Wecontributetothe community,addingourideastothebodyofknowledgeinthehopesthey willassistothersinprovinguswrongandthinkingdifferentlyaboutsocial scientificoutcomes.Wethankourcommunityhere.

PROFESSIONALACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thetwoofusfirstmetin2008atasmallworkshoponcourtsandhuman rightsorganizedbyWillMooreandJeffStatonandsponsoredbyFlorida StateUniversityandEmoryUniversity.Althoughtheworkshopwasfilled withprominentseniorscholars(manyofwhomwethankbelow),this finallyforthcomingprojectdevelopedinpajamasandoverthecourseofcar rides,asFSUgraduatestudentCourtenayhostedEmorygraduatestudent Emilyonanairmattressforthedurationoftheconference.Thankyou, WillandJeff,forstartingusonajourneythatwillendurethroughoutour careers.

Likeallgoodgraduatestudents,wefinishedourrespectivedissertations beforewereallygotstartedonthisproject,whichbeganwithapuzzle andamodelandgrewfromthere.Theformaltheoryanditsimplications forgovernmentrepressionwerepublishedinthe JournalofPolitics in 2013.Theimplicationsandevidenceformobilizeddissentwerepublished inthe ReviewofInternationalOrganizations in2016afterbeingawarded theBestPaperinInternationalRelationsattheAnnualMeetingofthe

(xi)

MidwestPoliticalScienceAssociationin2012.Apublicpresentationof someoftheargumentscontainedinthisbookwerepublishedin the WashingtonPost’sMonkeyCageBlogin2017.Weappreciatetheeditorsandreviewerswhoexamined,attacked,dismantled,praised,and improvedthesemanuscripts—includingatthemanyjournalswherethey wererejected.Thankyou,especially,toOxfordUniversityPress,oureditor DavidMcBride,andthreeveryhelpfulanonymousreviewers.Reviewing evenaportionofabookmanuscriptisnosmalltask,andweappreciate everyone’seffortstowardmakingthisonebetter.

Somanyoftheideascontainedinthisbook—itsconcepts,interpretations,scope,alternatives,relationships,andexamples—emergedfrom thevarietyofscholarstowhomwehavepresentedthisprojectinits variousforms.Inadditiontorefiningtheargumentswithourcolleagues attheUniversityofCalifornia,Merced,weshareditinconferences,online workshops,graduateseminars,andinvitedresearchtalks,benefitingfrom newquestionsandideasallthewhile.Thankyoutotheparticipantsin seminarsatBinghamtonUniversity;theStateUniversityofNewYorkat Buffalo;theUniversityofCalifornia,Berkeley;theUniversityofCalifornia, Merced;DukeUniversity;EmoryUniversity;FloridaStateUniversity; GeorgeWashingtonUniversity;UniversitätHamburg;theUniversityofIllinois;theUniversityofIndiana;theUniversityofIowa;theLondonSchool ofEconomics;theUniversityofMaryland;theUniversityofMichigan;the UniversityofMississippi;theUniversityofNebraska;theUniversityof Pennsylvania;PennsylvaniaStateUniversity;theUniversityofPittsburgh; PrincetonUniversity;RiceUniversity;theUniversityofSouthCarolina; TexasA&MUniversity;theUniversityofTexas;TexasTechUniversity; StanfordUniversity;VanderbiltUniversity;andYaleUniversity.Thankyou alsotoconferenceparticipantsatPrincetonUniversity,theMultiRights SummerInstituteattheUniversityofOslo,PoliticalEconomyofInternationalOrganizations,VisionsinMethodology,andtheannualmeetingsof severalnationalandinternationalpoliticalscienceorganizations.

Inspring2016,wehostedabookconferenceattheUniversityof California,Merced.AlthoughwepromisedourparticipantsCalifornia sunshine,itrainedfortheduration,includingduringapostworkshopvisit toYosemiteNationalPark.Overthecourseofthatrainyweekend,we werefortunatetohavesomeextremelyintelligent,creative,andgenerous scholarstearourprojectdownandthenbuilditbackupagain.Thankyouto KathleenCunningham,JamesHollyer,YonLupu,HeatherElkoMcKibben, WillMoore,JeffStaton,andScottWolfordformakingthetriptoMerced andbringingwiththemtheirverybestideastoshapeourmanuscript.Allof ourcolleaguesandgraduatestudentsatUCMercedwentoutoftheirwayto

(xii) Acknowledgments

makeourguestsfeelwelcome,especiallyPeterCarey,JaredOestman,and AesilWoo,whotookdetailednotesandhelpedwithconferencelogistics; TomHansford,whoablyledourraincoat-cladgroupthroughYosemite Valley;andNateMonroeandDarickRitter,whooffereduslogisticaland psychologicalsupportinourattemptstofeedandhouseourcolleaguesfor severaldays.Bookconferencesareexpensive;wearegratefultothePolitical ScienceDepartment,theSchoolofSocialSciences,Humanities,andArts atUCMerced,andtheTonyCoehloEndowedChairofPublicPolicyfor fundingtheworkshop.

Manygenerousmentorsandcolleaguesofferedustheirtimeandexpertiseintheformofinvaluablecomments,critiques,anddiscussionson variouspartsofthismanuscript.Priortothebookworkshop,Christian Davenport,EmilieHafner-Burton,andJeffStatonservedasmembers ofabookadvisorycommittee,commentingonchaptersandoffering counselaboutthebookpublishingprocess.Inadditiontothepeople namedabove—manyofwhomwecouldthankineveryparagraphof ouracknowledgments—webenefittedfromtheexpertiseandthoughtful suggestionsofPaulAlmeida,PhilArena,SamBell,TomClark,Chad Clay,JustinConrad,DannyHill,YukariIwanami,AmandaLicht,Carolina Mercado,AmandaMurdie,MonikaNalepa,RobO’Reilly,HongMinPark, CesareRomano,BethSimmons,JensSteffek,ChrisSullivan,JayUlfelder, JohannesUrpelainen,ErikVoeten,JanavonStein,JimVreeland,Geoff Wallace,JimWalsh,andJoeYoung.ExtraspecialthankstoYonLupu, WillMoore,andScottWolford,whoreadmorebadanddecentdrafts ofthearticlesandbookmanuscriptthanapersonshouldeverhaveto doforacolleagueorfriend.WearegratefultoEllenCutrone,Jeanette Hencken,DanielHoffmann,andSusanNavarroSmelcerforcopyeditingthe manuscriptatitsinterimstagesandtoHeathSledge(http://heathsledge. com)forquickandablecopyeditingwhileweworkedtomeetourfinal deadlines.Overthecourseofourpresentationsofthiswork,wearegrateful tohavehadhundredsofadditionalhelpfulconversationsthatimproved ourargumentsimmensely.Wecertainlyhaveforgottentolistsomeone importantbyname,notbecauseweareungrateful,butbecauseweare overwhelmedwithgratitudeforthewealthofexpertiseonwhichwehave beenfortunateenoughtodraw.

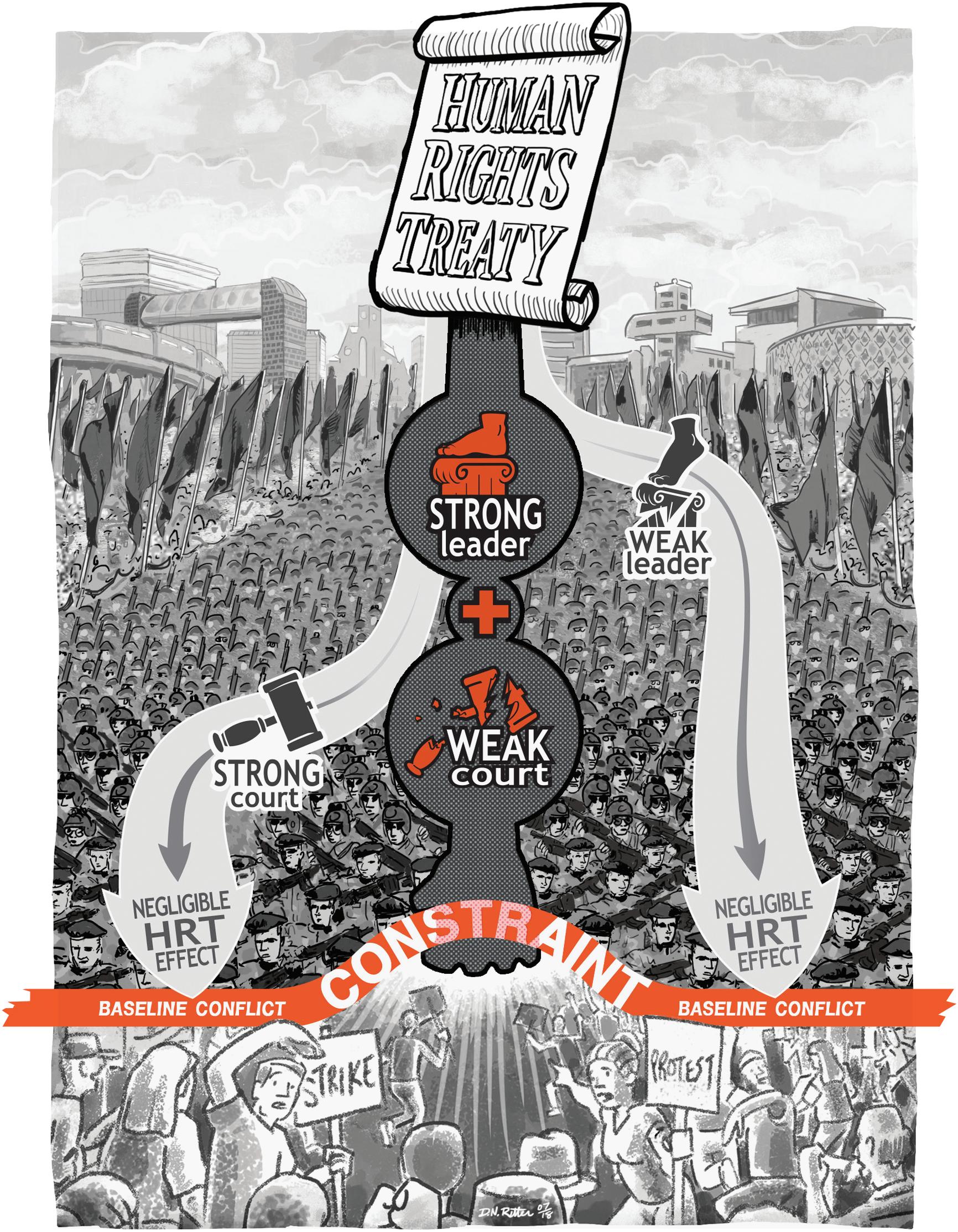

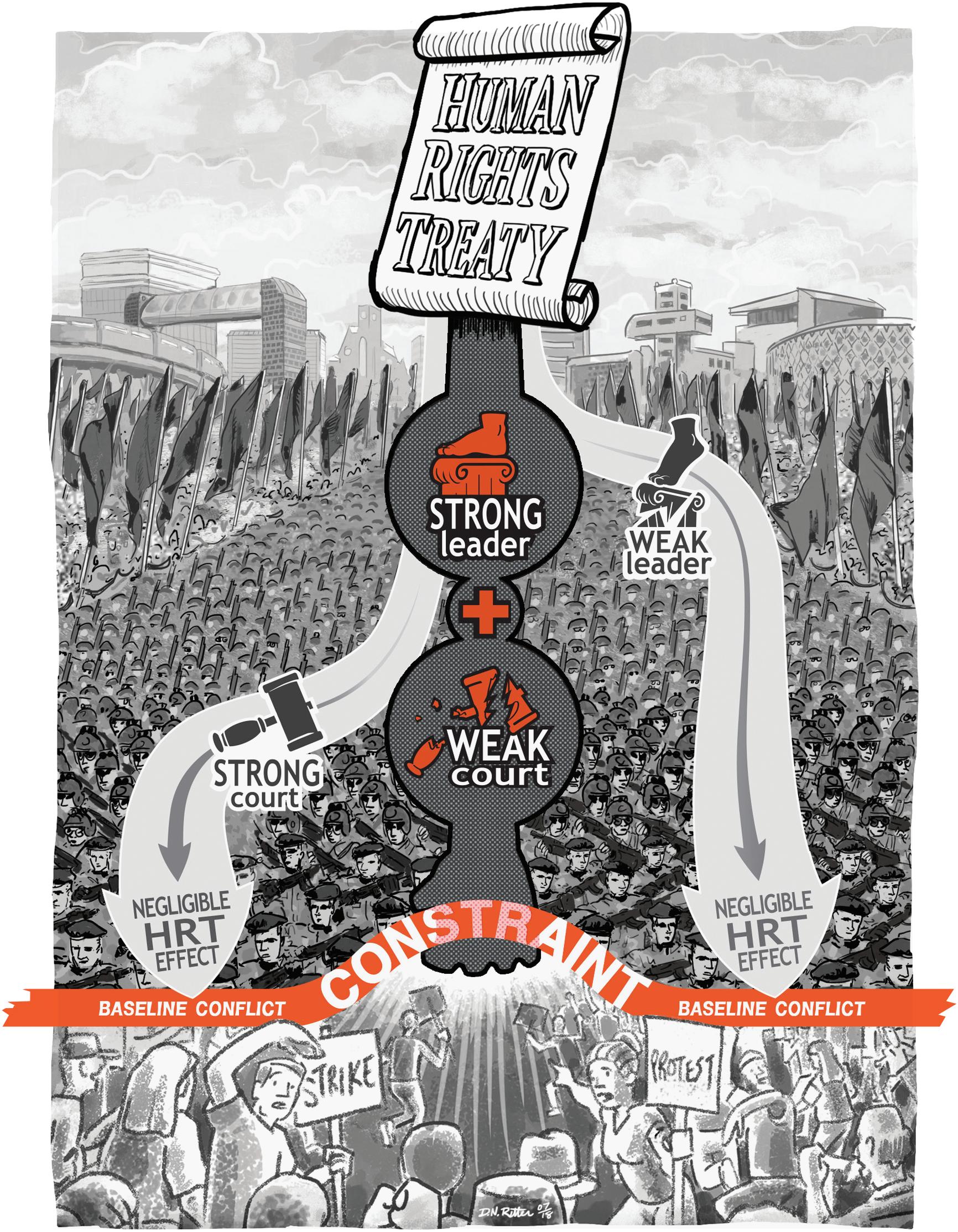

DarickRitter(www.sequentialpotential.com),whoisanincrediblytalentedartist,tookourformalmodel—basedonmathematicalequationsand socialscientificjargon—andturneditintoaworkofartthatconveysthe maincontributionsofthisbooktowideaudiences.Wearethrilledthat Oxfordagreedtopublishhiswork,Figure3.1,incolor,asitsuccinctly summarizes(andbringstolife!)thedynamicsofwhatsometimesfeelslike

Acknowledgments(xiii)

averycomplicatedstory.Darickalsodesignedandillustratedourbeautiful bookcover,whichwelove.Becauseourtheoryisbasedoncounterfactual analysis,itissimilarlychallengingtolocateillustrativeexamplesofits dynamics;tothatend,wearealsogratefultoPeterCarey,IshitaChaudhry, ChrisMedina,andgraduatestudentsatUniversitätHamburgforhelping usfindexamplestocolorourprose.

DEDICATION

WededicatethisbooktothememoryofWillMoore,whosework servesastheintellectualfoundationonwhichwebaseourarguments andwhowasanadvisor,amentor,andafriend.Overthecourse ofhiscareer,Will’sresearchtendedtowardtwomaintopics:the dissent-repression“nexus”andtheeffectofinstitutionsongovernment respect(orlackofrespect)forhumanrights.Theframeworkforthetheory andempiricalteststhatwepresentinthisbook—ourcontentionthat scholarsshouldtaketheconflictseriouslywhentheyinvestigatethe effectofinstitutionsonhumanrightsoutcomes—wasbornofWill’s influence.

Perhapsasaresultofthisinfluence,helikedthebook.Atleast,we think helikedit;heinvestedinitbydismantlingmultipleversionsofitmultiple times.Hecelebratedwhenwefinishedthefirstdraft,andhecelebrated whenitwassentoutforreview.Willdiedoneyearagotoday,thedayon whichwepenthisdedication.Hedidnotlivetocelebratewithuswhenthe bookwasacceptedforpublication,ashehadwhensomanyofourother publicationswereputinprint.Wehopethefinalversionoftheproject wouldmakehimproud.

InadditiontobeinginfluencedbyWill’sscholarship,wewerealso incalculablyfortunatetobetherecipientsofhistime,hisenergy,and hismentorship.Willwasinsatiablycuriousandintellectuallytireless. Heinvestedheavilyinbothofourcareers,spendinghoursuponhours guidingusandpushingustoimproveourwork.Hemodeledthepractice ofdoingthingsnotbecauseit’showotherscholarsdoitbutbecause it’sfascinating,bold,weird,inviting,andmaybewrong.Hetaught ustobuildinstitutionswherenoneexisttosolveaproblem,towrite non-positivistarticlesifyouhaveanideatoshare,andtoaskquestions innewanddifferentways.Becausehewasabuilderofcommunity,Will alsoencouragedustobefiercelysupportiveofoneanotherandofother scholarsinourcommunity.IndedicationtoWill,wepromisetopayit forward.

(xiv) Acknowledgments

PERSONALACKNOWLEDGMENTS:COURTENAY

Ihavebeenfortunatetohavemanygenerousmentors,colleagues,and friendstodirectmeinthisprofessionandtoredirectmewhenIwanderedoffcourse.ButWillMoorestandsaloneasthemostimportant drivinginfluenceinmybecoming—andcontinuingtoworkas—apolitical scientist.Willwasmydissertationadvisorandmycoauthor.Hewasan irreplaceablesourceofsupportandadviceuntilhisdeath;Irarelymake aprofessionaldecisiontodaywithoutfirstaskingmyselfwhatWillwould do,whatWillwouldsay.(Askingthosequestionssometimesresultsinmy doingtheoppositeofwhathewouldhavesuggested,butIknowhewould understand.)Willisnotsimplyresponsibleforinfluencingmywork;Iama politicalscientistbecauseofWillMoore.Imisshimimmensely.AndIhope toonedaybeevenhalfthescholarthathetaughtmetobe.

Mymostimportantpersonalthank-youistingedwithprofessional gratitude.Myhusband,Nate,makesmylifeimmeasurablybetterevery day—byfillingmydayswithjoyandlaughter,byworkinghardtobuilda Homewithme,andbymakingmeaspiretobeabetterscholar.I’mgrateful tohavehisfingerprintsonmylifeandonmywork.ThankyoutoAbby andWillforembracingmeasfamilyandremindingme(daily!)aboutthe importanceofwork-lifebalance.Iloveyoubothverymuchandcannot waittoseeyouwithyournewsister,Charlie—who,thankfully,seemsto havedelayedherarrivaljustlongenoughforustocompletethisbook.Iam endlesslygratefultomyparents,BillandCharlotte,whoinstilledinmea greatloveoflearning,alwaysmaintainedhighexpectationsformeinspite ofmyfailures,andreassuredmetirelesslyalongtheway.Thankyoutothe restofmyfamily—Matt,Elaina,Mary,Keith,Amy,Dean,Dylan,Sadie, andPapa—forprovidingnecessarydiversionsfrommyworkandalways seeminginterestedinthisproject,evenwhenitfeltlikewemightnever finishit.Finally,anenormousdebtofgratitudegoestoEmily,whosets thebarincrediblyhighforcoauthors.Ithasbeen eight yearssincewefirst startedtalkingaboutthisproject;IcannotimagineanyonewithwhomI’d ratherhavecelebrateditssuccessesorcriedaboutitssetbacks.

PERSONALACKNOWLEDGMENTS:EMILY

Ihadbeenadvisedoverandoveragainnottowriteabookbeforetenure becauseoftheuncertaintyofitstimeline.Ididsobecausetheideasinour headsweretoobigforarticles.Itneededtobeabook.SooftenIwishedI hadtakenmycolleagues’advice,andsooftenIwasgladIhadn’t.Though Ididnotheedtheirwarningsonthisparticularpoint,Iconstantlylean

Acknowledgments(xv)

onmentors,colleagues,andfriendsforadvice,reassurance,examples,and encouragement.

Ihaveboundlessgratitudeformypoliticalsciencecolleaguesatthe UniversityofCalifornia,Merced.Iammovingtoanewuniversitythisyear afterfiveyearsatMerced,andthelossofthesecolleaguesleavesacrater inme.AtMerced,Ilearnedhowtothinkdeeplyandacrosscontexts.I learnedthevalueofbothlikenessanddiversityofthought.Ilearnedhow tobuildnewinstitutionsfromscratchanddisagreerespectfully.Ilearned howtomentorothersfromthosewhomentoredme.AndIlearnedhow tohonorandpracticework-lifebalanceandequityofexperience.Iam indebtedtomyUCMcolleagues,finepeopleandresearchersall:Aditya Dasgupta,DanieldeKadt,DavidFortunato,MattHibbing,HaifengHuang, BradLeVeck,MelissaSands,andAlexTheodoridis.Iamespeciallygrateful tothefoundersofthismagnificentdepartment,whosooftenbearmore service,responsibility,andkindnessthantheyshouldhaveto,sothat thejuniorfacultycansucceed,allwhileadvancingtowardasteadyvision andpublishingtheirownbrilliantwork.Thankyou,TomHansford,Nate Monroe,SteveNicholson,and(myseniormentor!)JessicaTrounstine. YourexamplewillfollowmeasIdevelopmyownroleasaseniorscholar.

Imustofcoursethankthemanysteadfastandsupportivementorson whomIrelyinmakingsomanycareerdecisions.WarrenRosenblumwasa keysupporterandcriticwhileIwasafledglingundergraduatescholarand remainsoneofmyloudestcheerleadersnow.DavidDavis,JeffStaton,Jen Gandhi,TomClark,DaniReiter,andespeciallyCliffCarrubbacontinually actasacademicfamilytome,steppingasidetowatchmegrowwhile continuingtoanswermycalls,longafterIlefttheEmorynest.Christian DavenportandWillMooreidentifiedmeasapersonwithpotentiallong beforeIwouldhaveknownit,andtheyinvitedmeintotheirfold.They shapedwhoIamasathinker,colleague,mentor,andparticipatorin academia.Ihopetosomedaybethekindofmentortosomeoneelse thattheyhavebeentome.ThankyouespeciallytoScottWolford,whose discerningeyeisoneverythingIwrite.IwouldnotbethescholarIamif notforyou.

Finally,Imustthankmyfamily—thoserelatedbyblood,marriage,or friendship.Mymom,Jeanette,taughtmefairnessandrespectforallpeople,andshepassedtometheexcitementofdiscoveryandunderstanding. Mydad,Tom,taughtmehowthingsworkandthemechanismsofcause andeffectinthegarage.Thankyou,both,formakingmeascientist.Thank youtothemanypeoplewholoveandrootformeinmyfamily—mysister, myin-laws,myaunts,uncles,cousins,grandparents—wearealargebrood ofloudlove.Thankyoutomybeautifulfriends:LindseyBarrow,Jessica

(xvi) Acknowledgments

Braithwaite,CassyDorff,KaraGibson,CarissaHansford,DanielHoffman, RyanLouis,DougMackay,AlexMain,AmieMedley,StephanieRaczkowski, TobyRider,SaraSchumacher,SusanNavarroSmelcer,JakanaThomas, JamesWilson,andScottWolford.Ioftenneedpullingupbymyarmpits andatriptotheoutdoorstofindmyselfagain,andyouarethepeoplewho findmewhenIamtoolosttodoitonmyown.AndtoCourtenay,with whomIamsoinsyncthatwemightbeofone(verydetail-oriented)mind: Icannotwaitforahundredmoreretreatsofcreating,writing,laughing, andcryingwithyou.

MygreatestlovesareDarickandHenryRitter.Thankyouforgivingme wings,pushingmetofly,andremindingmetocomebackhome.Youare myeverything.

Acknowledgments(xvii)

ContentiousCompliance

Figure. Thetheory:ConditionalpredictionsofHRTobligationonconflictbehavior

Figure. Thetheory:ConditionalpredictionsofHRTobligationonconflictbehavior

DoHumanRightsTreaties ProtectRights?

Everyonewantstobesafefromgovernmentviolence.Unfortunately, billionsofpeopleexperiencehumanrightsabusesasawayoflife.More peopledieatthehandsoftheirowngovernmentthaninwar.Minority groupsareexcludedfrompower,peoplearedeniedaccesstoeducation, dissidentsarebeaten,prisonersaretortured.Accordingtoannualreports onhumanrightspracticespublishedbyAmnestyInternational(AI)andthe U.S.DepartmentofState,everygovernmentviolatestherightsofsome ofitscitizensineveryyear.Duringthelasttwodecadesofthetwentieth century,over70percentofgovernmentshaveengagedintortureineach year.1 In2012alone,overahundredcountrieswereaccusedoflimiting theircitizens’rightstofreedomofexpression,andthesecurityforces offiftycountrieswerereportedtohaveunlawfullykilledcitizens.2 The mostfrequentvictimsofrepressionaremembersofvulnerablegroups: womenandchildren,elderlypersons,indigenouscultures,andimpoverishedpopulations.3 In2011,forexample,AIreportedthatindigenous peoplesintheAmericasstruggledforgovernmentrecognitionoftheir landrights,andinEuropeandCentralAsia,migrants,theRoma,and lesbian,gay,bisexual,andtransgender(LGBT+)individualscontinued tofacewidespreaddiscrimination.4 Violationsofhumanrightscanhave

1.Cingranelli,Richards,andClay2014;Conrad,Haglund,andMoore2013.

2.AmnestyInternational2013.

3.See,e.g.,Conrad,Haglund,andMoore2013;Rejali2007.

4.AmnestyInternational2012.

CHAPTER

(1)

widespread,direconsequences:Restrictionsofindividuallibertiesareassociatedwithpovertyandinequality,societalconflict,andnondemocratic governance.

Inthefaceofsuchabuses,individualsallovertheworlddemandthe righttospeaktheirmindsandchallengetheirgovernmentswithoutfear ofdiscriminationorviolentreprisal.Groupsofpeoplewhoopposeexisting policiesorresourceallocationscanworktogethertopressurethegovernmentforchange,peacefullyorviolently;authoritiescanendordeterthe popularthreatbyrepressing,accommodating,oradaptinginoneofmany otherways.Evenindemocracies,majoritiesandotherpowerfulgroupsmay supportrepressionbecausetheyderivepowerfrommaintainingthestatus quo.5 Asininternationalconflict,domesticdiscriminationandviolenceare extensionsofbargainingoverdisputedpoliciesandresources.Manypeople seegovernmentrepressionasanaturalpartofpolitics.

Victims,humanrightsadvocates,andpolicymakerscontinuallysearch forwaystoendgovernmentabusesandtheirheinousindividualandsocial consequences.Theremedymostoftensuggestedislaw.Governmentsand internationalorganizationsaliketurntolawsandcourtstoidentify,stop, andpreventviolationsofhumanrights.Lawsdefineindividualrights, layingoutthegovernment’sobligationswithregardtopeople’ssecurity; courtsadjudicateviolationswhentheyoccursothattheycanberectified.6 Unlikemanyotherdemocraticinstitutions,theruleoflawisintendedto protectminoritiesfromthewill(andabuse)ofthemajority,andlawand courtsarethusidealforprotectingvulnerablepopulationsfromviolations ofhumanrights.7

Thisisthedrivingideabehindinternationalhumanrightstreaties (HRTs),designedinthewakeofWorldWarIItoprotectcitizenrightsfrom governmentintrusion.8 Inratifyinganinternationalhumanrightstreaty, nationalgovernmentspubliclycommitthemselvestoprotecttherightsof personsundertheirdomesticrule.Theselawsexplicitlydefinetherights towhichpeopleareentitled,aswellasthelegaldutiesoftheratifying countriestoprotectpeoplefromtheinfringementofthoserights.Some treatiesarebroad,governingawideswathofhumanrightsandrelevant populations(liketheInternationalCovenantonCivilandPoliticalRights). Othersaremorespecific,definingtherightsandobligationswithregardto

5.Conrad,Hill,andMoore2017.

6.See,e.g.,Cross1999;Hathaway2005;Keith2002b;Moustafa2007;Powelland Staton2009.

7.Conrad,Hill,andMoore2017.

8.Anumberofprominentscholarshavewrittendetailed,informativeaccounts ofthehistoricaldevelopmentoftheinternationalhumanrightsregime,including Simmons(2009,Chapter2)andHafner-Burton(2013,Chapter4).

(2) ContentiousCompliance

oneviolation(liketorture,asintheUNConventionAgainstTortureand OtherCruel,InhumanorDegradingTreatmentorPunishment)oroffering specificprotectionstoonegroup(likechildren,asintheUNConventionon theRightsoftheChild).

Governmentleadersfacedomesticandinternationalpressuretoobligate themselvestointernationalhumanrightslaw.Domesticactors,including nongovernmentalorganizations(NGOs),unions,andpoliticalopposition parties,encourageheadsofstatetosignhumanrightstreaties.9 Internationalleadersandinstitutionsalsopressuregovernments,usingavariety ofpunishmentsandrewardstoencouragethemtocommittointernational standardsbasedonanassumptionthattreatieswillpositivelyinfluence governmentalrightsprotections.10 Victimsandadvocatesoftenactas iftreatieshavethelegalandpoliticalstrengthtobindauthoritieswho wouldviolaterights.Theyrefertointernationalobligationstoprotectin domesticcourtcases,inprotests,innewsreports,andinsocialmovement campaigns.

Butdoesinternationalhumanrightslawactuallyreducegovernment repression?Althoughhumanrightstreatiesclearlydefineobligations andarelegallybinding,theyrarelyincludemechanismsfordomestic orinternationalenforcement.Signatorygovernmentsmustrestrain themselvesandtheiragents,eitherbycreatingdomesticinstitutions thatpunishrightsviolationsorchoosingontheirownnotto repress.

Withoutinherentenforcement,scholars,policymakers,andevendissidentsexpecthumanrightstreatiesto“work”onlywhensignatorieswould notviolaterightsanyway;inotherwords,treatiesconstrainrepression onlyintheabsenceofadomesticthreattopower.Governmentauthoritieswillallowthemselvestobeconstrainedbytreatiesonlywhenthey canusetacticsotherthanrepressiontoeffectivelycontrolchallenges. Institutionsthatallowforpeacefulleaderreplacement,forinstance,are morelikelytoprotectrightswhenoppositiongroupspushforelectoral turnover.11

If,instead,theypredominantlyrepresswhenchallenged,governments ignoretheirinternationalobligations.Autocraticregimesarefrequently signatoriestointernationalhumanrightstreatieswhileviolatingthe treaties’termswithimpunity.Forexample,countriesincludingtheDemocraticRepublicofCongo,China,Egypt,Syria,andmanyothershaveratified

9.Hafner-Burton2009.

10.FinnemoreandSikkink1998;KeckandSikkink1998;Risse,Ropp,andSikkink 1999.

11.Hafner-Burton,Hyde,andJablonski2014.

DOHUMANRIGHTSTREATIESPROTECTRIGHTS? (3)

theUNConventionAgainstTorture(CAT)whilecontinuingtoengage inthetortureandill-treatmentoftheircitizensatalarmingrates.Syria accededtotheChemicalWeaponsConventionin2013,duringitsongoing civilconflict,butinApril2017unleashedchemicalagents,killingdozens andmaiminghundredsofcivilians.12 Democraticleadersdothis,too,publiclydenigratinginternationallawswiththeintenttoviolatetheirterms. PrimeMinisterTheresaMayrespondedtoterrorattacksin2017byproposingtochangeBritain’shumanrightslawstoallowauthoritiestodeportsuspectedterroristswithoutsufficientevidencetoconvict.Shehassimilarly arguedthattheUnitedKingdomshouldleavetheEuropeanConvention forHumanRights(ECHR),saying,“TheECHRcanbindthehandsofparliament,addsnothingtoourprosperity,makesuslesssecurebypreventing thedeportationofdangerousforeignnationals—anddoesnothingto changetheattitudesofgovernmentslikeRussia’swhenitcomestohuman rights.”13

Withfrequentabusesinallregimetypesandpublicdisdainforinternationalrightstreatiesamongstateleaders,scholarsandpolicymakerstend tobepessimisticabouttheabilityofhumanrightslawtolimitgovernment repression.Manyarguethatinternationalhumanrightstreatiesaremere windowdressing,lettingstatesputonabenevolentimagewhileviolating rightswhenevertheycanjustifyitintheinterestofpower.14

Inthisbook,wearguethatgovernmentdecisionsaboutwhetherto complywithinternationalhumanrightsobligationsaredirectlytiedto conflictswithciviliansoverpolicies;inotherwords, compliance with internationalhumanrightslawisafunctionof contention.Toknowwhether andwhenhumanrightstreatieswilleffectivelyconstraingovernments fromrepression,wemustunderstandthecontextofdissentfacedbythose governments.Mostscholarsstudyinghumanrightstreatiesfocusonthe extenttowhichauthoritieshavethe opportunity torepress.Theyassume thatgovernmentswillviolaterightswheneverpossibleandinternational anddomesticinstitutionslimitthegovernments’possibilitiesoropportunitiestodoso.Thisapproachassumesthatcountrieswithstronginstitutionsofconstraint,likedomesticcourts,contestedelections,ordemocratic legislatures,aremoreresponsivetohumanrightstreatyconstraintsthan thosewithweakinstitutions.15 Yet,aswithanypotentiallawviolation,

12.LoveluckandDeYoung2017.

13.May,quotedinAsthanaandMason2016.

14.Downs,Rocke,andBarsoom1996;Goodliffe,Hawkins,etal.2012;Hathaway 2002;vonStein2016.

15.See,e.g.,CingranelliandFilippov2010;Keith2012;Lupu2013a,2015;Simmons 2009;vonStein2016.

(4) ContentiousCompliance

opportunitytomisbehavewithoutthemotivetodosoyieldsnocrime.

Popularchallengesandthethreattheyrepresenttoagovernment’shold onpoliciesandpowerconstitutethestate’sprimary motive torepress.To determinewhetherinternationalhumanrightstreatiescanmeaningfully influenceagovernment’shumanrightsbehaviors,wemustfirstconsider theincentivesthatmotivateleaderstorepress.

.TREATIESANDTHEINCENTIVETOVIOLATE HUMANRIGHTS

Posner(2014,Chapter1)openshiscontroversialbookwithavignetteabout AmarildodeSouza,aBrazilianbricklayerwhoinJuly2013wastortured anddisappearedbymembersoftheUnidadedePoliciaPacificadora(UPP) aspartofitsoperationtocrackdownondrugtrafficking.Followinghis disappearance,protesterstooktothestreetsinMr.deSouza’shometown ofRocinhaandthroughoutBrazil,callingforaninvestigationintothe disappearance.Inseveralinstances,demonstrationsweremetwithadditionalpoliceviolence.OvertwentyBrazilianpoliceofficerswereeventually chargedwith(andtenwereconvictedof)torturingandmurderingMr.de Souza.BasedonthedeSouzacaseandhisownaccountoftheprevalence ofdisappearancesinBrazil,Posnersuggeststhatinternationalhuman rightstreaties—institutionsintendedtoconstraintheseverytypesof governmentbehaviors—havefailed.AccordingtoPosner,Mr.deSouza wouldnothavebeentorturedandkilledifhumanrightstreatieswereable tosuccessfullyconstrainnationalauthorities.

Certainly,Mr.deSouza’sdisappearancehighlightsthefactthatthe Braziliangovernmentengagedinhumanrightsabusesevenafterthe countrybecamepartytoseveralinternationalhumanrightstreaties.But perhapsBrazilianabuseswouldhavebeen worse absenttheirinternational commitment.WhatwouldBrazilianhumanrightspracticeshavebeen ifthecountrywerenotamemberoftheinternationalrightstreaties towhichitisaparty?Woulddisappearanceshavebeenevenmore prevalent?Obviously,itisimpossibletoknowforsure;thisexerciseis hypothetical.Butratherthanassumethatonehighlyvisibleabuseof humanrightsmeansthathumanrightstreatieshavefailed,weusecareful deductionbasedontheobservablecharacteristicsofcountriesto predict whatthosecountrieswouldhavedoneunderadifferenttreatyobligation status.

InternationalcommitmentsdidnotpreventthecrimeagainstMr.de Souza,buttheymayhavepreventedothercrimesfromoccurring.Police mighthaveusedviolenttacticsmoreopenly,oragainstmorecivilians,

DOHUMANRIGHTSTREATIESPROTECTRIGHTS? (5)

intheabsenceofinternationalobligations.Brazilianauthoritiesmay represslessoverallthantheywouldhavewithouttheconstraintsoffered byinternationaltreatycommitments.Humanrightstreatiesalsomight beresponsible—eitherdirectlyorindirectly,viatheireffectonthepublic’s willingnesstoprotest—forensuringjusticeinBraziliancourtsforMr.de Souzaandhisfamily.Followingtheprotests,NGOHumanRightsWatch repeatedlypressuredBraziltoupholditsinternationalobligations,stating, “TheBraziliangovernment’sobligationunderthisbodyoflawandnorms [internationalhumanrightslaw]isnotonlytopreventtortureandcruel, inhuman,ordegradingtreatmentbutalsotothoroughlyinvestigateand prosecutesuchactswhentheyoccur—includingbymakingcertainthat detaineesarebroughtbeforejudicialauthoritieswithoutunnecessary delay.”16 Althoughtreatylawmaynotpreventallviolationsofhuman rights,wearguethattreatiesaffectdomesticconflictandpolicyoutcomes. Anation’scommitmenttothetermsofinternationalhumanrights—and theexpectationthatauthoritiescanbeheldlegallyresponsibleforrights violations—canemboldenpopularprotest,andprotestitselfinfluences governmentrepression.

Thissimpleexampleillustratestheimportanceofidentifyingthecounterfactual.Whatwouldhappeninatreaty-obligatedcountryifitfacedthe verysameinstitutionsandconflictbut wasnot obligatedtoaninternational humanrightstreaty?Whatwouldhappeninanunobligatedcountry ifitfacedthesameinstitutionsandconflictbut was obligatedunder internationallaw?

Toanswerthesequestions,wecannotlooksimplyathumanrights practicesbeforeandafteragovernmentratifiesaninternationalhuman rightstreaty.Adecreaseinviolationsaftertreatyratificationdoesnot necessarilymeanthetreatyisresponsibleforthechange,andanincreasein violationspostratificationdoesnotnecessarilymeanthetreatyisfailingto limitgovernmentrepression.Reductionsingovernmentabusesofhuman rightsmaybetheresultofotherinstitutionsthatconstrainauthorities fromrepression17 orofbehavioralchangesinpoliticalinteractionsthat reduceincentivestorepress,18 suchthatthetreatyisnotmeaningfully constrainingstatebehavior.19 Andwhilegovernmentsmayviolaterights moreafterratifyinganinternationaltreatythantheydidpreviously,ifthat heightenedlevelofrepressionislessthantheywouldhavechosenunder

16.HumanRightsWatch2014.

17.vonStein2016.

18.Ritter2014.

19.See,e.g.,Downs,Rocke,andBarsoom1996;SimmonsandHopkins2005;von Stein2005.

(6) ContentiousCompliance

thesameconditionsabsentthetreatycommitment,internationallawhas successfullyincreasedprotectionforhumanrights.

Inthisbook,wecarefullyinvestigatetwocounterfactuals.First,for countriesthathaveratifiedaninternationalhumanrightstreaty,does thatobligationimprovegovernment respectforhumanrightsrelative totheprojectedlevelofrepressionthatwouldhaveexistedabsentthe treaty?Second,forcountriesthathavenotcommittedtoaninternationalhumanrightstreaty,wouldtreatyratificationimprovegovernment respectforhumanrightsrelativetoextantrightspracticesabsentthe treaty?

Ofcourse,itisimpossibletodirectlyobservewhatwouldhavehappened inanalternativetreatystatusforeachcountry.Weusecarefullydefined conceptsandmathematicaltheorytohelpusidentifythemostlogicalpossibleoutcomeforeachunobservedstate.Weassumethatallgovernments faceasetofincentives—dissidentsconsideringameaningfulchallenge tothestatusquoandinstitutionsthreateningconsequences—thatinfluencetheirdecisionstocommittointernationalhumanrightslaworto violatepeople’shumanrights.Domesticandinternationalconstraining institutions,andthegovernment’sstrategicinteractionwithdissidents, determinetheextenttowhichagovernmentwillrepress.Weusethe observablecharacteristicsofacountryatagivenmomentintimetopredict levelsofrepressionanddissentfortwoalternativescenarios,oneinwhich thecountryiscommittedtointernationalhumanrightslawandonein whichthecountryisnotcommittedtointernationalhumanrightslaw. Thedifferenceinconflictactivitiesacrossthetwoscenariosrepresentsthe treaty’seffectonhumanrightspractices.

.CONTENTIOUSCOMPLIANCE:THEARGUMENT

Themainpointofthisbook—itsmostimportantcontribution—istopoint outthatinternationalhumanrightstreatieswork.Theyimprovehuman rightsoutcomes.Notallthetime,andnotwithperfectcertainty.Butunder certainconditions—namely,whenthestakesofretainingpowerarehigh forpoliticalleadersanddomesticcourtsarerelativelypooratconstraining theexecutive—internationalhumanrightslawaltersthestructureofthe strategicconflictbetweenpoliticalauthoritiesandpotentialdissidents, significantlydecreasinggovernmentrepressionandincreasingmobilized dissentactivities.

Todrawconclusionsaboutwhetherandhowinternationaltreatyobligationsaffecthumanrightspractices,weneedtoestablishwhenandwhya

DOHUMANRIGHTSTREATIESPROTECTRIGHTS? (7)

governmentwouldwanttoabusehumanrightsinthefirstplace.Todothat, wemodelthepoliticalconflictbetweendissidentsandgovernmentauthoritiesanditseffectsongovernmentoutcomes;thislaysoutthegovernment’s baselinemotivetoengageinrepression.Inaddition,weincorporateinto ourtheorythedomesticinstitutionsthatwouldconstrainthoseleaders fromrepressing.Thisdefinestheopportunitytorepress,enablingusto seetheextenttowhichgovernmentrepressionisdomesticallypermitted orprevented,regardlessofthegovernment’streatystatus.Finally,governmentscanchoosewhethertoratifyaninternationalHRT,whichwillcreate consequences—somemarginal,somesignificant—forviolatingitsterms. Inwhole,thetheoryallowsustopredictwhatgovernmentrepressionwould looklikeinacountrywithaparticularsetofcharacteristicsandthendraw predictionsabouthowrepressionwoulddifferunderanobligationtoan internationalhumanrightstreaty.

Repression isdefinedasanythreatenedlimitorcoerciveactionlevied bygovernmentauthoritiestocontrolorpreventdomesticpoliticalchallengesthatwouldalterthestatusquopolicyordistributionofpower.20 Repressionismotivatedasaresponsetoorinpreventionofdissent.21 Itcanbelegalorillegal,violentornonviolent,anditincludestactics rangingfromgovernmentlimitsonfreedomofspeechandassembly, discriminatorypolicies,andunlawfulsurveillancetopoliticalarrests,mass torture,andkilling.Itincludesbothwhatscholarsandpractitioners callcivillibertiesviolationsandphysicalintegrityviolations.Anybehaviorusedtopreventpeoplefromparticipatingintheirowngovernance canbeconsideredrepression,andthevariousformsofrepressionare almostalwaysviolationsofhumanrightsasdefinedintheUniversal DeclarationofHumanRights(UDHR)andamultitudeofinternational treaties.

Ourdefinitionofgovernmentrepressionconstitutesanarrowerconceptualizationthanthebroaderlegalcategoryofhumanrightsviolations. Manyscholarsofhumanrightsfocusontherightsfirstdefinedassuch intheUDHR.Inadditiontotheviolationsthatweconsiderrepression, thelargercategoryofhumanrightsincludes,forexample,arightto education,tohealthcare,andtoone’sownculture(Hafner-Burton2013, Chapter2).Governmentsmayviolatetheserightsforpurposesofexclusion orcontrol,aswhenwomenarenotallowedaneducationoragroupis deniedtheuseofitsnativelanguage;weconsiderthosebehaviorsto berepression.However,theserightsmayalsobeviolatedduetoalack

20.Cf.Davenport2007a;Goldstein1978;PoeandTate1994;Ritter2014. 21.RitterandConrad2016b.

(8) ContentiousCompliance

ofinfrastructuralcapacitywithinagivenstate;wedonotconsidersuch violationstoberepression,althoughtheyareindeedrightsviolations. Wefocusourattentiononrightsviolatedwiththeintenttocontrolor preventdomesticchallengestothepoliticalstatusquo,soastocorrectly capturethepoliticalprocessofcontentionratherthancapturingviolations thatoccurbecauseofalackofcapacitytoprotect.Werefertothese governmentviolationsinterchangeablythroughoutthebookas(human) rightsviolationsandgovernmentrepression.

Governmentsdonotviolatehumanrightsrandomlyorwithoutreason; theyrepressduringconflictsoverdomesticpolicy.Authoritieswantto controlthestatusquothroughpolicyorpracticeorregime,and(some) peoplewithinthestate’sterritorialjurisdictionlikelypreferadifferent policyorpracticeorregime.Governmentsviolatehumanrightstoretain controlwhentheyarethreatenedbyanimplicitorexplicitdomestic challenge.Repressioncanreducepoliticalchallengers’abilitytothreaten theincumbentgovernment22 orhelpthegovernmentdeterminetheextent towhichdissenterswillgotoupsetthestatusquo.23 Tobesure,authorities alsoviolaterightsformanynontacticalreasons,includingbias,culture, resourcelimitations,ortheinterestofdomesticsecurity.24 Thesemotives arelessmutablethanthedesireforcontrolorpower,andtheyproduceoutcomesviaadifferentprocessthanrepression,whichisexplicitlyconnected tothreat.Wefocushereonrepression.

Wedefine mobilizeddissent asacoordinatedattemptbyagroupof nongovernmentactorstoinfluencepoliticaloutcomesoutsideofmeans organizedbythestate.25 Governmentauthoritiesaremorelikelyto repressdissentasitbecomesmoreviolent,moremultidimensional,more organized,ormorethreateninginitsgoals.26 Ifthereisno(threatof)dissent,leadershavelittlereasontorepress.Somecountriesfacelittledissent andconsequentlyhavelittlereasontoviolatehumanrights;acountry’s positivehumanrightsrecordisnotalwaysduetorightsprotectionsfrom internationalhumanrightstreatiesoranyotherinstitutions.

Repressionanddissentareconnected,inthattheyoccuraspartofa strategicinteractionbetweenthegovernmentandpotentialdissidents.The governmentengages(ornot)inrepressioninexpectationofdissent,and

22.NordåsandDavenport2013;Sullivan2016b.

23.Galtung1969;RitterandConrad2016b.

24.Hafner-Burton2013.

25.Weusetheterms dissent and challenge interchangeably.Forsimilardefinitions, see,e.g.,Tilly1978;Tarrow1991;andMcAdam1999.

26.See,e.g.,Davenport1995,1996,2000;DavisandWard1990;Francisco1996; GartnerandRegan1996;Moore1998;Poe,Tate,Keith,andLanier2000.

DOHUMANRIGHTSTREATIESPROTECTRIGHTS? (9)

dissidentsmobilizeandtakeaction(ornot)inexpectationofrepression.27

InPartI,wepresentaformaltheorythatstartsfromasimplemodel ofstrategicconflict:Governmentauthoritiesanddissidentschoosehow muchtorepressanddissent,respectively,intheattempttowincontrol oversomepolicyoutcome.Becauserepressionanddissentchoicesareso intertwined,wespecifyatheoryofsimultaneousaction,meaningthata leaderandagroupofdissidentseachchoosetheirconflictbehaviorsin theknowledgethattheotheractorismakingdecisionsatthesametime. Anythingaffectingthegovernment’schoicetorepress—forexample,a commitmenttoaninternationalhumanrightstreaty—affectsnotonlythe government’sdecisionaboutrepressionbuttheentiretyoftheconflict. Whenatreatyconstrainsthegovernment’sabilityorwillingnesstorepress, italsoinfluencesthedissidents’choicesregardingdissent,whichinturn altersthegovernment’sdecisionaboutwhethertorespondwithsome formofrepression.Fromthistheory,wedrawconclusionsaboutthe effectsofinternationalhumanrightstreatiesonbothgovernmentrepression and mobilizeddissent—interdependentoutcomesofasingleconflict process.

Governmentauthoritiesfacedwithdissentdonotalwaysrepress:they aremorelikelytoviolatehumanrightswhendissentoccursinacontext thatisparticularlythreateningtotheirabilitytosetpoliciesorhold power.28 Whenlosingtheconflicttoadissidentgroupdamagestheleader’s authority,theleaderrepressestoavoidthatoutcome.Theleaderisalso morelikelytorepressasthestakesofholdingofficeincrease.Whenholding officeisparticularlyvaluableortheconsequencesforlosingofficeare terrible,dissidentsaremorelikelytochallengethegovernment.Thus,as thestakesofholdingofficeincrease,leadersaremorelikelytorepressto preventpossiblelosstodissidents.29

Someleaderswhoaremotivatedtorepressareneverthelessconstrained fromdoingsobydomesticpoliticalinstitutionsthatmakerepression morecostly.Thedomesticinstitutionmostconsistentlyfoundtoconstrain 27.Cf.Ritter2014.

28.Davenport2000;Lorentzen2013;Poe,Tate,Keith,andLanier2000.

29.Wereferformallytothisconceptasaleader’s expectedvalueforpower.Weuse theterm“expectedvalue”becauseitencompassesbothhowmuchtheleaderbenefits fromretainingpowerandhowmuchtheyexpecttoremaininthatposition.Formally, thisisavonNeumann–Morgensternexpectedutilityfunction,whichmultipliesthe probabilitythattheleaderwillremaininpowerattheendoftheinteraction(whichwe denoteas θ ,where0 ≤ θ ≤ 1)bythevalueofstayinginpower(vin )orthevalueoflosing it(whichwenormalizeto0).Theleader’sexpectedvalueofretainingpowerisspecified as E[UL ]= θ ∗ vin + (1 θ) ∗ 0.

(10) ContentiousCompliance

governmentrepressionisthecourt.30 Aleadermotivatedtorepress dissidentshastoconsidertheprobabilityofincurringcourt-relatedcosts forviolatinghumanrights.Individualscanbringcivilandcriminalcases againstauthoritiesforviolatingrights,andtheirbeliefsaboutsuccessin thelegalprocessinformtheirpropensitytolitigate.Evenifthecourtswere toultimatelyruleinfavorofthegovernment,theprocessoflitigation involvescoststhatleadersprefertoavoid.Thepotentialforcostlylegal consequencesleadsauthoritiestorepresslessandremainunderthecourt’s radar,31 andthatrestraintopensopportunitiesfordissent. 32

Whenagovernmentratifiesaninternationalhumanrightstreaty,the treatyisincorporatedintoanexistingbaselineofconstraint,muchofwhich comesfromthedomesticcourt.Wearguethataninternationalhuman rightstreatyobligationaddstothebaselinepropensityforlitigationof humanrightsviolation,addingtoexistinglaws,33 increasingthevisibility andlegitimacyofrightsclaims,34 andencouragingNGOactivitysupporting victimsofhumanrightsviolationsinbringinglegalaction.35

Existingdomesticconstraintsthereforeconditionhowmeaningful internationaltreatiescanbeforchanginghumanrightsoutcomes.Whena governmentalreadyhaslawsthatprotectrights,policewhoenforcethose protections,andcourtsthatidentifyviolations,theprobabilityofhuman rightsprotectionchangesverylittlewhenatreatyisaddedtotheseexisting mechanisms.Inhis1970testimonytotheU.S.Senateduringdebateabout ratificationoftheGenocideConvention,RichardGardner,formerdeputy assistantsecretaryofstateforinternationalorganizationaffairsandalaw professoratColumbiaUniversity,testified,“Ratificationoftheconvention wouldcreatenonewcriminalliabilityforAmericancitizens,sincegenocide alreadyisacrimeunderfederalandstatelaw.”36 Countrieswithfewlawsin placeorcourtsthathavedifficultyrulingagainstthestatecandrawstrength frominternationaltreatyobligations.Thesearethecontextswherean internationaltreatycanmostchangethedomesticlegalenvironment. Inshort,internationalhumanrightstreatyobligationscreatenewand

30.See,e.g.,Cross1999;Hathaway2005;HillandJones2014;Keith2002b;Mitchell, Ring,andSpellman2013;PowellandStaton2009;Simmons2009.Foranargument thatitisnotthecourtbutthecourt’slitigantsthatconstrainthegovernment,see Rosenberg1991.

31.PowellandStaton2009.

32.RitterandConrad2016a.

33.Hill2015.

34.Simmons2009.

35.Hafner-Burton,LeVeck,andVictor2016.

36.Thisisaquotationfromanarticlesummarizinghisstatements.See“Genocide Convention”1971.

DOHUMANRIGHTSTREATIESPROTECTRIGHTS? (11)

Figure. Thetheory:ConditionalpredictionsofHRTobligationonconflictbehavior

Figure. Thetheory:ConditionalpredictionsofHRTobligationonconflictbehavior