The Advocacy & Awareness Issue

Winter 2023 A Publication of Hearing Health Foundation hhf.org

Winter 2023 A Publication of Hearing Health Foundation hhf.org

Speaking up to make a difference

The mission of Hearing Health Foundation is to prevent, research, and cure hearing loss and tinnitus through groundbreaking research and to promote hearing health. As the largest nonprofit funder of hearing and balance research in the U.S., we are a leader in driving innovation and treatments for people with hearing loss, tinnitus, and related conditions.

This issue’s theme is Advocacy & Awareness, an acknowledgment that hearing loss can be an invisible disability because it may not be immediately obvious that someone has difficulty hearing. It is also often the case that the person with a hearing loss has difficulty accepting and by extension treating their hearing loss. We hope this issue’s stories inspire readers to address their own or their loved ones’ hearing challenges. While over-the-counter hearing aids are poised to bring greater accessibility to adult consumers with mild to moderate hearing loss, managing hearing loss effectively still benefits from input from experienced medical or hearing care professionals.

Given the links between untreated hearing loss and overall well-being, including brain health, we owe it to ourselves to be as aware of our hearing health as we are about our vision, diet, or daily step count. Let’s all take care of our hearing, for life—get hearing tested regularly, remove the stigma of using hearing devices, advocate for quieter shared spaces, be aware of sound exposure, and wear earplugs when needed. Let’s love our ears. Please enjoy this issue and share it with family and friends. Thank you for your support and for being a part of our community.

Timothy Higdon President & CEO Hearing Health Foundation

Timothy Higdon President & CEO Hearing Health Foundation

Hearing Health

The Advocacy & Awareness Issue

Winter 2023, Volume 39, Number 1

Features 06 Living With Hearing Loss The Gene TMPRSS3 and Me. 08 Advocacy Science Is Just the Start. Daniel Fink, M.D. 12 Managing Hearing Loss If I Were the Minister of Hearing Health. Shari Eberts 13 Education What Social Media Can Teach Audiologists. Kathleen Wallace, Au.D. 14 Workplace Speaking Through Color. Matthew Masapollo, Ph.D. 18 Living With Hearing Loss Humming Again. Roberta Rubenstein Larson 21 Living With Misophonia My Misophonia Story. Kadyn Thorpe

Departments

46 Meet the Researcher Melissa Polonenko, Ph.D. Generously funded by Royal Arch Research Assistance

24 Research Spotlight On: Litao Tao, Ph.D. 26 Managing Hearing Loss Not Everyone Qualifies for OTC Hearing Aids. Stephen O. Frazier and Hansapani Rodrigo, Ph.D. 30 Living With Hearing Loss Educate, Educate, and Advocate, Advocate. Pat Dobbs 32 Advocacy A Daily Practice. Sarah Kirwan 34 Research Presenting the 2023 First-Year Emerging Research Grants Scientists. 38 Progress Report Recent Research by Hearing Health Foundation Scientists, Explained.

Publisher Timothy Higdon, President & CEO, HHF

Editor Yishane Lee

Art Director Robin Kidder

Senior Editor Amy Gross

Staff Writers Pat Dobbs, Shari Eberts, Stephen O. Frazier, Kathi Mestayer

Advertising GLM: 212.929.1300 hello@glmcommunications.com

Editorial Committee

Judy R. Dubno, Ph.D. Christopher Geissler, Ph.D. Lisa Goodrich, Ph.D. Anil K. Lalwani, M.D.

Rebecca M. Lewis, Au.D., Ph.D., CCC-A Joscelyn R.K. Martin, Au.D. Kathleen Wallace, Au.D.

Board of Directors

Chair: Elizabeth Keithley, Ph.D. Sophia Boccard Robert Boucai Judy R. Dubno, Ph.D. Jason Frank, J.D. Jay Grushkin, J.D. Roger M. Harris Cary Kopczynski

Sponsored 44 Advertisement Tech Solutions. 45 Marketplace

Hearing Health Foundation (HHF) and Hearing Health magazine do not endorse any product or service shown as paid advertisements. While HHF makes every effort to publish accurate information, it is not responsible for the accuracy of information therein. See hhf.org/ad-policy.

Cover A teen living in the Midwest, Lily created a website about variants in the gene TMPRSS3 that cause congenital hearing loss, like her own, as her Girl Scout Gold Award project.

Scan or visit hhf.org/subscribe to receive a FREE subscription to this magazine.

Sharon Kujawa, Ph.D. Anil K. Lalwani, M.D. Paul E. Orlin

Robert V. Shannon, Ph.D. Nancy Young, M.D.

Hearing Health Foundation PO Box 1397, New York, NY 10018

Phone: 212 257.6140 TTY: 888.435.6104 Email: info@hhf.org Web: hhf.org

Hearing Health Foundation is a tax-exempt, charitable organization and is eligible to receive tax-deductible contributions under the IRS Code 501(c)(3). Federal Tax ID: 13-1882107

Hearing Health magazine (ISSN 2691-9044, print; ISSN 2691-9052, online) is published four times annually by Hearing Health Foundation. Copyright 2023, Hearing Health Foundation. All rights reserved. Articles may not be reproduced without written permission from Hearing Health Foundation. USPS/Automatable Poly

To learn more or to subscribe or unsubscribe, call 212.257.6140 (TTY: 888.435.6104) or email info@hhf.org.

The Gene TMPRSS3 and Me

A teen learns about the genetic cause of her hearing loss, and is spreading the word to find out more.

My name is Lily and I am 15 years old. When I was born, I was diagnosed with profound bilateral hearing loss. At 10 months of age, I became one of the youngest in my state to receive bilateral cochlear implants. My parents were curious about the cause of my hearing loss. One expert told them they would probably never know, but my parents were determined to find out.

After connecting with a scientist at Harvard, my parents learned that the cause of my hearing loss was a variant in the gene TMPRSS3 (transmembrane protease serine 3). At the time, it was difficult for them to understand the implications. Scientists, primarily in Europe, had undertaken only a few studies. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become more interested in this subject and learned that while there’s been progress in the TMPRSS3 field, especially in the past few years, many of the same questions and challenges remain.

Having a hearing loss makes me interested in how the world works. Hearing with very complex computers—my cochlear implants—and participating in dozens of research studies from the time I was a baby, made me interested in science. I currently attend a science-focused high school and am learning about and doing research almost daily.

As a result of my passion for solving problems, my desire to help others, and needing to find the perfect project for my Girl Scout Gold Award (the highest honor for a Girl Scout), I created TMPRSS3.org. This website is the first and only of its kind, a comprehensive, easy-tounderstand source for anyone who wants to know more about the TMPRSS3 gene and its related hearing loss.

By drawing more attention to TMPRSS3, I want to make it easier for individuals, families, universities,

hospitals, and cochlear implant clinics to research, grow the knowledge base, and create potential future treatments and discoveries about this gene. More research will ultimately benefit those impacted by this gene. The more we learn about TMPRSS3, the more we can help others.

There are more than 123 genes linked to hearing loss, and researchers in this space have a lot of competition for their attention. TMPRSS3 is the fifth most common gene causally associated with deafness. Variants of the TMPRSS3 gene are the most common causative hearing loss genes in adults undergoing traditional and hybrid cochlear implantation.

TMPRSS3 is a complex gene, and can manifest differently in each person. The pathogenic variants in TMPRSS3 at the DFNB8 locus typically cause a postlingual (after speech) high-frequency/sloping hearing loss, with a slow deterioration of remaining hearing. In contrast, the TMPRSS3 DFNB10 variant is congenital, a prelingual (before speech) profound hearing loss at birth.

Aggregating Resources

The website TMPRSS3.org includes:

» Clear, understandable information about TMPRSS3 and DFNB8/10

» Database of 96 TMPRSS3 research studies (dating back to 1996)

» Trends analysis

» Key TMPRSS3 researchers (both past and present) and links to their labs

» Genetic testing information

» Opportunities for individuals to get involved with leading-edge TMPRSS3 research

At 10 months of age, Lily was one of the youngest in her state to receive bilateral cochlear implants. Her congenital hearing loss, the result of a variant in the gene TMPRSS3, led her to create a website about the gene that is her Girl Scout Gold Award project.

I’m thankful for my advisers and collaborators who continue to help me develop TMPRSS3.org and make it the best it can be. I’ve been encouraged by all the ear scientists, ENTs, Ph.D.s, and clinical experts who have been so kind with their time and mentoring. You never know the impact of responding to emails from “a 15-year-old.”

Throughout my life and through this process of developing my Girl Scout Gold Award TMPRSS3 Resource, I have had to be a strong self-advocate. Making this site available to those who can benefit is extremely necessary and very important to me.

So I ask readers of this story to do a few things. Please share this essential TMPRSS3 resource far and wide, and if possible, link it to your website or share it on social media. I appreciate your interest in hearing loss and look forward to any collaborations in the future to advance the science surrounding the TMPRSS3 gene.

Lily lives in the Midwest with her family. For more, see TMPRSS3.org. Contact her at tmprss3@gmail.com, or through the “contact us” box on the bottom of the TMPRSS3.org homepage.

Xi Lin, Ph.D., a 2000–2002 Emerging Research Grants (ERG) scientist, coauthored a study listed on TMPRSS3.org. Applications for the 2023–2024 ERG grants cycle are due February 28. Learn more at hhf.org/how-to-apply.

Having a hearing loss makes me interested in how the world works. Hearing with very complex computers— my cochlear implants—and participating in dozens of research studies from the time I was a baby, made me interested in science. I currently attend a science-focused high school and am learning about and doing research almost daily.

Share your story: Tell us your hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

Daniel Fink, M.D., in front of the Swiss Alps. He says he recorded daytime sound pressure levels of 42 dBA in the Alps, with the noise coming from the wind and distant road traffic noise, and nighttime levels of 30 dBA. A-weighted decibels, or dBA, emphasize the frequencies heard in human speech.

Science Is Just the Start

My path to outreach, advocacy, and activism around too much noise, and the successes—and ongoing challenges—so far. By Daniel

Fink, M.D.I’m a retired internist and have always tried to live a healthy lifestyle, but I had no idea that a one-time noise exposure could cause auditory symptoms for the rest of my life. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened to me at a New Year’s Eve dinner in Los Angeles, where I live, in 2007. As midnight approached, the restaurant kept turning the music up.

My wife could tell I was uncomfortable and suggested that we leave, but I didn’t want to offend our friends. When we finally left, my ears were ringing (that’s called tinnitus) and I later found that everyday sounds that didn’t bother others were actually painful for me (that’s called hyperacusis).

I wish I could say that I suffered in silence, but the world is too noisy for that. I became reluctant to go to restaurants. I started using earplugs at movies and sports events. I asked my wife, “Am I becoming grumpier as I get older?” and she immediately responded, “It’s too late for that, dear!”

In December 2014 I read an article about hyperacusis in The New York Times. I circled it in red and showed it to my wife, saying, “This is why I don’t want to go to restaurants anymore. They are all too noisy and it hurts my ears.”

I had recently left the board of a local environmental nonprofit, after my term concluded, so I had some extra time and energy and decided to see what I could do to make the world a quieter place.

First, I had to learn about the adverse effects of noise. This wasn’t something I had

learned in medical school or during residency training. Fortunately, the world’s scientific literature is now available to anyone with a device, internet connection, and search engine.

When I read that noise not only caused hearing loss, tinnitus, and hyperacusis, but also had non-auditory health effects, I knew I had to do something.

What could I do? Just knowing the science was not enough. I had to engage in outreach, advocacy, and activism. Outreach is letting people know important information. Advocacy is the act or process of supporting a cause. Activism is direct action in support of or in opposition to one side of an issue.

My activism is admittedly atypical. Instead of speaking at public meetings, writing letters and emails, organizing a petition, or getting neighbors to put up lawn signs, I focused on learning the facts about noise and then bringing those facts to the attention of those able to change public policy. I realized I needed to flip the typical activist mantra of “think globally, act locally” on its head, thinking locally but acting globally.

Policy change has to come from the top. I wanted to easily find a quiet restaurant in which to enjoy both a meal and conversation with my wife. I started with a presentation to my local health and safety commission about restaurant noise in January 2015, but quickly learned that it would be difficult to change people’s minds about noise when 85 decibels (dB) was regarded as the safe noise level.

The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders’ (NIDCD) webpage on noiseinduced hearing loss stated, “Know which sounds are dangerous (those at or above 85 decibels).” Plus, I could see it would be difficult to convince people that I wasn’t just a chronic complainer when the Acoustical Society of America and the America National Standards Institute define noise as “unwanted sound.”

I needed to change the nature of the conversation. I found a long-forgotten 1974 Environmental Protection Agency report online providing the only evidence-based safe noise level to prevent hearing loss as “70 dB timeweighted average” for 24 hours. In other words, our average exposure over the course of a day should be limited to 70 dB.

I realized what had happened: The NIDCD was citing the recommended occupational noise exposure level as the sound pressure level at which auditory damage begins. But the recommended occupational noise exposure level doesn’t fully prevent hearing loss in exposed workers, and it certainly isn’t safe for the public.

I found a long-forgotten 1974 Environmental Protection Agency report online providing the only evidence-based safe noise level to prevent hearing loss as “70 dB time-weighted average” for 24 hours. In other words, our average exposure over the course of a day should be limited to 70 dB.

In 2015 I was among those who brought to the CDC’s attention the fact that noise caused hearing loss in the general public, not just among workers in the workplace. (It’s also worth noting that noise exposure for the public occurs 24 hours a day and seven days a week, not just eight hours daily on weekdays at the workplace.) That led to the CDC embarking on both research and public health education about the dangers of non-occupational noise exposure.

Also in 2015, I was elected to the board of the American Tinnitus Association. I was no longer a lone-wolf activist.

In 2016, some of my noise colleagues and I started The Quiet Coalition, under the auspices of the existing nonprofit Quiet Communities Inc. (QCi), to focus specifically on making the world a quieter place.

That year I also submitted an abstract about the safe noise level to the Institute for Noise Control Engineering. To my surprise, the abstract was accepted for presentation. I submitted a manuscript based on my talk to the American Journal of Public Health (AJPH). Again to my surprise, the editor told me that if I rewrote it as an editorial, it would be published.

The AJPH editorial appeared online in December 2016, and it has now been cited 72 times in peer-reviewed scientific and medical literature. It led to an invitation to serve as an expert consultant to the World Health Organization for its Make Listening Safe program.

In 2019 I submitted an abstract to the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) about a new definition of noise—“noise is unwanted and/or harmful sound”—with the crucial addition of “harmful.” I presented the new definition and then published it. The definition hasn’t made it to the dictionary yet, but it was the first sentence of the January 2022 American Public Health Association policy statement, “Noise as a Public Health Hazard.”

I once saw a presentation by Paul Farmer, M.D., Ph.D., whom The New York Times termed “a pioneer of public health” in his February 2022 obituary. He asked the audience, “Can one person make a difference?” He cited Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, and Martin Luther King Jr. Farmer certainly made a difference, with his efforts to improve global health for the poor. More recently, so did climate change activist and Swedish teen Greta Thunberg.

I’m definitely not in that league, and I want to emphasize that I didn’t work alone, but always had support and advice from a small group of colleagues. The late Bryan Pollard of Hyperacusis Research introduced me to QCi founder Jamie Banks, who in turn introduced me to David Sykes, whose suggestions and encouragement led to presentations at national and international noise meetings. Gina Briggs finds items to write about, and posts almost daily blog posts, many of which have been written by pioneering noise researcher Arline Bronzaft. (All of us are now part of QCi.) Noise experts around the world have generously shared their expertise with me, and told me when I was wrong.

I Count These as Successes

» The CDC recognized non-occupational noise exposure caused hearing loss in the public.

» The NIDCD removed language from its webpage on noise-induced hearing loss that implied that auditory damage began at 85 dB.

» The CDC now states (as of 2019): “Noise above 70 dB over a prolonged period of time may start to damage your hearing.”

» The International Telecommunications Union included recommendations for lower noise exposure levels for children and other sensitive users in its Guidelines for Safe Listening Devices/Systems.

» A question about screening for hearing loss in middle-aged and older adults was referred to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which reconsidered its recommendation even if the literature still didn’t support screening.

» The U.K. Advertising Standards Authority took action against Amazon for falsely advertising that headphones with an 85 dB volume limit were safe for toddlers and children.

» And now googling the term “safe noise level” gives results that say 70 dB is the safe limit, often mentioning my 2017 editorial, instead of the occupational limit of 85 dB.

But So Far These Remain Failures

» Restaurants are still too noisy. Gas-powered leaf blowers are still used in my city, despite an ordinance banning their use.

» Despite my efforts, the Federal Trade Commission hasn’t taken enforcement action against the vendors of the 85 dB headphones; and the Consumer Product Safety Commission hasn’t put warning stickers reading “This product may cause hearing loss” on personal listening devices.

» Movies and sports events are still too loud. So are weddings and birthday parties. The world remains noisy.

Quiet Activism

I’m not giving up. As I write this, I am also preparing for the December meeting of the ASA in Nashville, where I will be presenting three papers.

I will next submit manuscripts to the ASA’s journal, Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics. A publication lends greater credibility to what I have to say, and then I can send that link around in future emails to policy makers, government representatives, and other activists.

How will I measure success? When the world becomes a quieter place.

As intermediate steps, I’d like to see 1) the Surgeon General issue a Call to Action to Prevent Noise-Induced Hearing Loss, just like the Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer, and 2) the HealthyChildren.org website run by the American Academy of Pediatrics share as much advice for parents about noise and the ear as it does about sun and the skin.

Please join us to make the world quieter, and to make it a better place for those with auditory disorders like hearing loss, tinnitus, or hyperacusis. I encourage you to use your talents and contacts to advocate for quieter spaces. As noise activists—or is it quiet activists?—we really can make a difference.

Daniel Fink, M.D., is the founding chair of The Quiet Coalition, the interim chair of Quiet Communities Inc.’s Health Advisory Council, and a former board member of the American Tinnitus Association. He serves as an expert consultant to the World Health Organization on its Make Listening Safe Program, and as a subject matter expert on noise and the public to the National Center for Environmental Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This is based on his presentation at the 13th Congress (e-Congress) of the International Commission on Biological Effects of Noise in June 2021. For references, see hhf.org/winter2023-references.

Share your story: Have you advocated for quiet? Tell us at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

If I Were the Minister of Hearing Health

By Shari EbertsI am a huge Harry Potter fan so when someone asked me, “What would you do if you were the Minister of Hearing Health?” my head immediately filled with images of wands and other wizardly gear. Could I simply flick my wand and make hearing loss disappear, I wondered?

Okay, back to reality.

Hearing loss makes communication difficult, and communication is the glue that binds us to the people and activities we love. Healthy hearing helps us stay connected to the things that matter to us. When people at all stages of the hearing journey—even those with typical hearing— accept this link, we will see real change.

My Healthy Hearing Priorities

1. Link healthy hearing to overall health. Hearing loss is associated with many health problems including depression, a higher risk of falls, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Hearing loss is also one of the largest modifiable risk factors for developing dementia. Making this information more widely known is key.

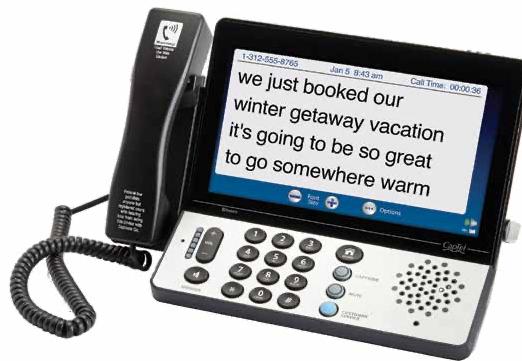

2. Beef up accessibility measures. According to the World Health Organization, 430 million people worldwide have disabling hearing loss, and this number is expected to jump to 700 million by 2050, affecting 10 percent of the population. Beefing up accessibility measures like captioning and assistive listening technologies in public spaces, entertainment venues, and online will help keep this growing population engaged.

3. Incorporate hearing into routine medical care. Why don’t doctors regularly screen for hearing loss? Perhaps they don’t understand the linkages to overall health, or perhaps they are not reimbursed for doing so. Insurance plans and medical school training must be modified to put hearing care center stage. We must also learn to understand our role in receiving proper hearing care.

4. Make hearing devices of all types affordable. Hearing aids are expensive. So are cochlear implants, but at least in the United States, implants are usually covered by insurance. New over-the-counter hearing aids for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss will help improve access, but overall affordability is lacking. We must

expand national health and private insurance plans so they include not only regular hearing tests, but also devices and aural rehabilitation services.

5. Promote hearing loss prevention. Scientists cannot yet repair damaged hearing, so we must protect it. Health curricula for students of all ages must teach how and why to protect hearing. Making the use of hearing protection cool would save millions from the challenges of hearing loss. As would better enforcement of noise protection laws.

6. Support research into treatments and cures. The more scientists learn about how hearing works (and doesn’t work), the more success they will have in developing new cures and better ways to prevent hearing loss. Governments must allocate more funds to support this work.

If I were a fantasy Minister of Hearing Health, this is what I would hope to achieve. As a real-life healthy hearing advocate, I’m already spreading the word.

Staff writer Shari Eberts serves on the Hearing Loss Association of America’s Board of Directors and is a past chair of HHF’s Board of Directors. This is adapted from her blog at livingwithhearingloss.com. Eberts and Gael Hannan, coauthors of the book “Hear & Beyond,” discuss the topic of this column on the Habits & Health podcast, at tonywinyard.com/shari-eberts-gael-hannan. For references, see hhf.org/winter2023-references.

Share your story: What would you do as Minister of Hearing Health? Tell us at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

What Social Media Can Teach Audiologists

By Kathleen Wallace, Au.D.Audiologists are a tiny, but mighty, profession consisting of only 13,000 professionals to service the third most common chronic condition in the United States (hearing loss), the most common service related disability (tinnitus), the leading cause of visits to the emergency rooms (falls), and the condition for which one billion people worldwide are at risk (noise-induced hearing loss). Yet, most people don’t know what an audiologist is and pay little attention to their own ears.

When I meet new people and get asked what I do, my answer is often met with blank stares. On the occasions when someone does know what an audiologist is, it is typically a game of word associations: audiologist with hearing aid and old people or perhaps nurse with hearing screening and elementary school

This, however, doesn’t come as a surprise. Audiologists have long struggled with promoting the profession both within healthcare and among the general public.

But what tends to happen next is where things really get interesting. Once people know I’m an audiologist, friends, family, and strangers come out of the woodwork with ear questions. I have been asked about earwax at funerals, my thoughts on over-the-counter hearing aids at weddings, hearing protection at baptisms, and vertigo at birthday parties. It turns out people are actually quite curious about their ears! They just never knew who to ask.

With this insight, I took to social media to gauge the appetite for people to learn more about their ears. I decided that I’d turn the countless questions I’ve gotten in real life into short, digestible, educational videos where I answer them as if I just met you at a party. On social media as @EarDocOfTikTok, I’ve garnered millions of views, tens of thousands of comments, and thousands of followers. The comments section is (mostly) filled with more ear questions or topic requests, ranging from fairly simple

inquiries like how to pronounce tinnitus to more complex topics like why accents are so difficult to understand.

Here are a few insights I’ve gained from TikTok: » Social media challenges you to deliver your message as succinctly and clearly as possible, and to do so in an engaging manner. It has been excellent practice for counseling patients and figuring out how to boil down years of study and clinical experience into salient points.

» It has been the best market research possible, giving a pulse on how people are thinking about their ears, audiologists, areas of interest, and service delivery methods. There are a lot of opportunities for audiologists to evolve if we’re willing to listen to what our patients truly want.

» People want the guidance of a professional, but many don’t know how to get to one. Our knowledge base is more sought after than many may realize; we just aren’t reaching them in the right way. Audiologists have to continue public outreach and engagement.

My hope is these videos will help close the gap between audiologists and the public and pull the veil back on the often convoluted hearing healthcare space. By putting education and awareness at the forefront, audiologists can build the trust needed to evolve this profession and better serve our patients. All we have to do, ironically, is listen.

Find Hearing Health editorial committee member

Kathleen Wallace, Au.D., at @EarDocOfTikTok in TikTok, @drkathleenwallace on Instagram, via TunedCare at tunedcare.com, and at her practice in New York City. For more, see kathleenwallaceaud.com.

Matthew Masapollo, Ph.D., works to support, mentor, and encourage those who are perpetually underrepresented in speech science because of a lack of resources and opportunities.

As part of his research, he uses the University of Florida Gator (opposite page) to help explain speech motor control.

Speaking Through Color

The ongoing effort to train students of diverse backgrounds in speech communication and engineering research.

By Matthew Masapollo, Ph.D.Higher education has multiple missions and purposes. At a public research university like the University of Florida (UF), my home institution, producing knowledge and preparing students for careers in the years that follow is the primary objective.

A secondary objective of that education is to elevate students and prepare them for achievement and fulfillment in a wider context, as they become professionals and community leaders within the broader society. Achieving these objectives entails creating and maintaining academic environments in which the differences among people enhance rather than detract from what we are able to learn and accomplish together.

Yet, while living with difference is a ubiquitous reality today, diversity remains a central challenge. As a faculty member in the department of speech, language, and hearing sciences at UF, diversity and fairness are of great concern in my own endeavors. My laboratory, which is engaged in basic and clinical research on sensorimotor mechanisms in speech motor control, is both multicultural and multidisciplinary.

The lab draws together talented, promising students from across the UF campus to combine the latest technology, principles, and tools from

engineering and computer science with speech and hearing science to facilitate advancements in our understanding of impaired speech communication. Our ongoing Hearing Health Foundation–funded work, in collaboration with Susan Nittrouer, Ph.D., is examining speech articulation in congenitally deaf individuals who receive cochlear implants. This diversity of perspective has undoubtedly been critical to our ability to innovate and conduct high-risk/high-payoff research on auditorily guided motor control.

Unfortunately, though, our field as a whole is woefully lacking in diversity—over 90 percent of speech-language pathologists are white, and only 4 percent are Black, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association’s membership data. Even fewer make it to scientific prominence in the field. Large disparities also exist between how individuals who are racial minorities receive speech therapy compared with white individuals.

Each of us must rigorously examine our own actions, motivations, and commitment to ensure that higher education and our profession become increasingly diverse and inclusive. Toward that end, I am constantly thinking of ways to remediate this problem and take affirmative steps to support, mentor, and encourage those who are perpetually underrepresented in speech and engineering science because of a lack of resources and opportunities to pursue an education in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics).

I actively incorporate first generation undergraduate

students of color into my research projects and engage them in the processes of creativity and innovation. Jessica Goel is a class of 2023 biomedical engineering major and the director of industry relations for the UF Society of Women Engineers. She is carrying out original research alongside me to develop optimal methods to dynamically image laryngeal (glottal) and supra-laryngeal vocal tract (lip, tongue, and jaw) structures during speech production. We are imaging individuals with congenital auditory deficits as well as peers with typical hearing using state-of-the-art electromagnetic articulography (EMA) and electroglottography.

Undergraduates who receive training in engineering and speech motor control typically have sparse access to, and gain little expertise with, these types of measurement tools and clinical populations. But in our lab, first generation undergraduates like Jessica have the opportunity to conduct world-class, mentored, hands-on research, and contribute meaningfully to the creation of new knowledge. Jessica has already co-authored several peer-reviewed journal articles—including one that made the October 2021 cover of JASA (Journal of the Acoustical Society of America) Express Letters—and presented her work at local and national meetings, which has helped her begin building a professional network.

This set of experiences has helped to set Jessica on an early path toward science. She plans to pursue a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering, with a focus on imaging and medical devices.

While living with difference is a ubiquitous reality today, diversity remains a central challenge. As a faculty member in the department of speech, language, and hearing sciences at the University of Florida, diversity and fairness are of great concern in my own endeavors. My laboratory, which is engaged in basic as well as clinical research, is both multicultural and multidisciplinary.

Recruiting undergraduate lab assistants at an annual campus research expo is an opportunity to meet with and encourage underrepresented students to consider a career in science— which many of them cannot yet imagine for themselves.

Opposite page: Masapollo is training undergraduates like Jessica Goel to conduct world-class, mentored, hands-on research and contribute meaningfully to the creation of new knowledge.

Many other undergraduates like Jessica who come from a wide range of disciplines—including linguistics; psychology; speech, language, and hearing sciences; computer science; and neuroscience—yearn to be future communication scientists and clinicians. As a result they are working with me on various research projects and manuscripts, such as through independent studies or thesis projects, that provide them with an exciting window into something that they want to do.

For example, Siddhi Kondapalli is a class of 2024 applied physiology and kinesiology major, and Ana Rodriguez is a class of 2024 speech, language, and hearing sciences major who recently received the Robert W. Young Award for Undergraduate Research in Acoustics from the Acoustical Society of America. They are each working on thesis projects using EMA to determine how the lips, tongue, jaw, and glottis work together to produce smooth and coordinated movements during skilled speech production. Aleena Alex, a class of 2025 biomedical engineering major, is exploring the role of auditory feedback in spatiotemporal coordination of speech movements in the context of an independent study project.

Cultivating a diverse and energetic lab group is a constant challenge, especially in a state like Florida which banned the use of affirmative action in undergraduate admissions. To keep the lab diverse, I utilize several recruitment and retention strategies. UF hosts an annual research expo where I am able to meet with and encourage underrepresented students to consider a career in science, which many of them cannot yet imagine for themselves. Recruitment efforts for underrepresented groups also include outreach to campus organizations, such as the Society of Women Engineers, that serve STEM education for minorities nationally.

Prospective students are also encouraged to tour the lab, attend my weekly lab meetings, and observe experimental sessions to help gauge if research might be their chosen path. Once a student commits to a research project, I am proactive in ensuring that they receive strong support as they move through their training program, and encourage them to view themselves as a young

Prospective students are encouraged to tour the lab, attend my weekly lab meetings, and observe experimental sessions to help gauge if research might be their chosen path. Once a student commits to a research project, I am proactive in ensuring that they receive strong support as they move through their training program, and encourage them to view themselves as a young colleague actively participating in the process of knowledge creation. At some point during their training, most students will experience moments where they falter, become discouraged, or think the hard work of conducting rigorous science is not worth it, and we must be in a position to support them when they need us.

colleague actively participating in the process of knowledge creation. At some point during their training, most students will experience moments where they falter, become discouraged, or think the hard work of conducting rigorous science is not worth it, and we must be in a position to support them when they need us.

Collaboration between students and faculty on research projects is especially important for underrepresented students. In science it’s so critical to have role models and peers for these groups and other people who look like you and are like you. I experienced this firsthand. As a gay man, I very much remember wanting to see more individuals with a similar identity as mine captured and represented in the scientific arena.

While I was an undergraduate at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, one of my faculty mentors was also gay. At that point, I had never met an “out” gay scientist before. Just being able to talk about data and theories with him made me feel like I had a place in the scientific community. Our conversations meant an awful lot to me, and I hope to be able to call on so many things that I learned from him as I continue to mentor my own students.

The bottom line is that a strong and empowering education can overturn notions of inferiority and inadequacy, and that is why we must not be silent in higher education but rather “speak through color” and persist in our struggle to foster the representation of minorities in our classrooms, clinics, and laboratories.

A 2022–2023 Emerging Research Grants scientist, Matthew Masapollo, Ph.D., is the director and principal investigator of the University of Florida’s Speech Communication Laboratory.

Share your story: Tell us your hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

Humming Again

A professor of literature chronicles her hearing loss journey through her personal and professional spheres.

By Roberta Rubenstein Larson

By Roberta Rubenstein Larson

When did I first recognize that I might be losing my hearing? Perhaps it was when I became quite ill while in college and was hospitalized for a week with a severe case of mononucleosis complicated by strep throat. Among the treatments I received was streptomycin, an antibiotic that was successful for treating strep throat, tuberculosis, and other infections, but was later discovered to be ototoxic, causing irreversible damage to cochlear hair cells and the onset of permanent hearing loss in some patients. However, I knew nothing about these potential side effects at the time.

Several years later, signs of my hearing loss began to be visible—or, I should say, audible. During my early 20s, while I was visiting vacationing family members at a lake in Maine, someone commented on the haunting cries of loons calling to one another. What loons? I could not hear these unique water birds’ melancholy songs, which range over many frequencies, including high pitched notes—the same upper frequencies at which many human hearing losses are first discovered during audiological exams.

Not too long after I became aware of my hearing loss, I awoke in fright one morning. Every sound was significantly distorted, as if it had been drastically remixed inside a noisy tunnel. I immediately contacted an otolaryngologist, who diagnosed the condition as sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL).

Though the cause of this audiological crisis is—like that of most hearing losses—unknown, the doctor mentioned that it may be triggered by common conditions like earwax or viruses, or more serious conditions such as head injury, side effects of certain medications, or autoimmune reactions. It may also be triggered as a reaction to sulfites used in the production of wine, which I speculated was my case, from a party the previous evening. Though treatment with steroid medication restored some but not all of my lost hearing, for decades afterward I avoided red wine entirely, regarding it as the cause of an allergic reaction I hoped never to experience again.

A Progressive Loss

During the early years of my career as a professor of literature at American University in Washington, D.C., my hearing loss inexplicably progressed. I struggled to maintain auditory competence in the classroom, boosting the hearing in my better ear through a series of increasingly powerful hearing aids. My poorer ear could not be aided because the interval between barely audible and painfully loud sounds was too small.

I dreaded the annual audiological exam. Sitting in the soundproof cubicle, I concentrated intensely on raw tones delivered at different frequencies and volumes or strained to repeat words and phrases spoken by a recorded voice. Each audiogram confirmed the downward slope of the graph as my hearing loss progressed from moderate to severe to profound.

As a professor in midcareer whose teaching directly depended on the spontaneity of class discussions rather than prepared lectures, I began to suffer from depression. I faced the prospect of early retirement from a profession I loved. Having received positive student feedback and several teaching awards, I knew I was an effective teacher—except for the challenges to comprehension posed by students who mumbled, spoke softly, or commented with a hand over their mouth.

The loss of hearing is a profoundly emotional occurrence. It is disheartening to miss key portions of dialogue in ordinary conversations, telephone chats, film voiceovers, theater performances, and virtually every other aural context. It is demeaning to be perceived as cognitively impaired when one simply asks for directions and misses crucial details in the answer.

During the peak years of the Covid pandemic, face masks made (and still make) life much more difficult for people with hearing loss. While protecting the wearer, a mask muffles speech and removes the possibility of

reading lips. Missed words particularly affect the aural rhythms of jokes, which typically depend on wordplay and a rapid reversal of listeners’ expectations. Just when one anticipates the emotional payoff that elicits laughter, the volume of the speaker’s voice drops with the punchline. We miss the joke.

In response to my diminishing hearing aptitude, I learned over time to employ two coping mechanisms. First, I spontaneously learned to read lips; second, in concentrating to comprehend speech as fully as I could, I became a very attentive listener—a valuable skill for a professor. To improve my lipreading proficiency, I took several classes offered by a woman who, when she was only 21 years old, had suddenly lost all hearing due to a severe viral infection and had become a skilled speech reader and teacher.

Ready for Implants

At this point, during my 50s, my audiologist informed me that I was profoundly deaf in both ears and recommended that I consider getting a cochlear implant (CI). With some trepidation, I proceeded to do so, receiving the first of two implants in 2000. This remarkable surgically implanted device functions by transforming sounds received by a speech processor into digital information, bypassing the damaged hair cells in the cochlea to stimulate the auditory nerve directly.

My doctor was John Niparko, M.D., the distinguished otolaryngologist and ear surgeon at Johns Hopkins University Hospital, who died at age 61 in 2016. He concurred with my preference to have the implant in my poorer ear. Since I simply could not imagine actually hearing via digitally processed sounds, I reasoned that I had less to lose if I received the implant in the unremediated ear that had not apprehended meaningful sounds for years. Though otolaryngologists have disagreed on whether implantation in the better or poorer ear in patients is the more successful strategy, clinical research has demonstrated that the difference in outcomes is inconsequential.

Fifteen years later, I received a second implant, in my once “better” ear. The speech processor, whose components were produced by Advanced Bionics (also the maker of my first processor), featured many enhancements, including rechargeable batteries that last 18 hours rather than just four hours on a single charge. But, disappointingly, it was less successful than the first one.

Because of technical advancements during the 15-year interval between my two implants, the two processors

were essentially incompatible. For the first six months after the newer device was implanted, I experienced the audiological equivalent of double vision as my brain tried to reconcile two dissimilar sound streams. Although the separate sound streams eventually merged into one, my brain continues to rely primarily on the older implant.

Outpatient CI surgery is followed by a six-week recovery period while the surgical site heals. Before my first implant was activated, I wrote in the journal I kept of this unparalleled experience:

“I’m looking forward to this adventure, as my brain learns to make sense of sounds I haven’t heard for years. I hope that in due course I’ll be able to hear without always having to see the speaker, use a phone, hear in the dark, and—maybe—enjoy classical music again. I also hope that, when I don’t have to struggle so hard to hear, I’ll relax more in my life.”

Then: The CI audiologist “turned on” the device and… I heard sounds! The problem was, I could make no sense of them. (I had been told to expect this first stage.) When my husband drove us home on activation day, I heard something coming from the car radio but had no idea whether it was speech or music.

Sound recognition and speech comprehension do not arrive instantaneously, like turning on the tap for water. Rather, new CI recipients are assisted by specially trained CI audiologists, who fine-tune (“map”) digital settings in the external processor to align with the recipient’s sound comprehension profile, and by speech therapists, who help them recognize letters and words amid a garbled stream of sound. Over time, CI recipients retrain their brains to make sense of sounds that were initially incomprehensible.

There were so many new sounds, especially environmental ones, to identify. Before my implant, I hadn’t realized that for many years I had not heard birds singing in my garden. Once I began to hear them, I recalled the unheard loon calls years earlier that were the first evidence of my hearing loss and cried with joy at these newly audible dimensions of my environment.

Initially, hearing many sounds that I did not recognize, I would ask my husband or children, “What was that?” Random sounds, such as the blip a decoding device makes as it registers the barcode on groceries, were entirely new to me. I was surprised to discover that the wood floors in my house squeaked and that the refrigerator, dishwasher, and other appliances hummed. I began to hum myself.

As I became more proficient in interpreting sounds and speech, I realized that the learning process undertaken

by new CI recipients is analogous to the way infants learn language, beginning when they first recognize their own name and advancing as repeated words emerge from a bewildering stream of noise. This process of comprehension is the essential developmental stage that commences long before babies speak their own first words. It was thrilling for me to be immersed in this process the second time around, this time as an adult who could observe while experiencing what was happening not in my ear but in my brain. When I attended my first child’s college graduation a year after my implant, I was elated to understand almost every word spoken, not only by my daughter and her friends and professors but also by the commencement speaker that year, Toni Morrison.

Hearing Gains

Placing my experience of hearing losses in context, I— like so many other people with hearing loss—am also the recipient of numerous hearing gains. We are fortunate beneficiaries of a technological revolution, including not only cochlear implants but also increasingly sophisticated hearing aids as well as assistive devices, apps in theaters and cinemas, and mobile phones. Increasingly, we can access captions on computers, television, and phones as well as in many live theaters and cinemas.

Most of these accommodations are the result of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the 1990 civil rights law that “[prohibits] discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life….” For the most part, people with hearing loss have gained entrance to a kindlier environment that has liberated us from the woefully silent, lonely world that those before us have experienced for most of history.

I feel exceptionally fortunate. My hearing journey has ultimately been a positive one, both personally and professionally. Although I once dreaded involuntary early retirement, necessitated by my profound hearing loss, instead I continued to teach for the next 25 years. After 51 deeply gratifying years in the classroom, just three years ago, in May 2020, I retired from American University as Professor Emerita of Literature.

Roberta Rubenstein Larson lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland. For references, see hhf.org/winter2023-references.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

My Misophonia Story

When I was 13 years old, I was diagnosed with misophonia. This is my story. By

Kadyn ThorpeMisophonia is a brain disorder. For those who have it, certain noises will send them into a fight or flight type of response. We call these noises triggers. My triggers include loud eating, plates and silverware clanking, crunching, whispering, and many more everyday sounds. When I hear these sounds, it’s not just an annoyance that overtakes me; it’s rage.

When I was 12 years old I could tell there was something wrong with me. I remember riding in the car with my papa and having this feeling take over my body when he would chew on ice. It was a mixed feeling—rage, irritation, anxiety, and confusion all in one. My body would start to shake, and I would feel pain hearing the sounds coming from his mouth. I would start to distract myself from the pain by scratching my arms and legs, digging my nails into my skin. I know now that this is a response to the misophonia pain, to create another source of pain to try to ignore it.

I went on like this for a year, listening to my friends and family eat with their mouths open, crunching on chips, and constantly hitting their plates with their forks while eating. I thought I was insane. I was too afraid to tell anyone. I couldn’t tell them that these noises put me in a feeling of anger and pain.

I started retreating to my room when dinner was ready, but that still didn’t help. All the triggers were amplified in my head. My family could be downstairs eating and I could be upstairs, in my room, door closed and television on, and still hear the sounds of forks hitting the plate and the crunching of food as they enjoyed their meal. It was torture.

I fought it till one day, while shopping with my mom. She was walking through the store chewing gum, smacking every second louder than an airhorn in my mind. I would start walking slower, trying to get away, because I didn’t know how else to deal with it. She got mad and I couldn’t hold it in anymore. She thought I was crazy, and hearing it said out loud, I couldn’t even believe myself. What person is so sensitive that they can’t deal with everyday sounds?

After that day, I finally decided to look up my symptoms and try to find answers. I know, I know, you shouldn’t google your symptoms, but I was desperate. I found a brain disorder called misophonia, which described exactly how I was feeling, so I shared it with my mom. After that we decided we should go to the doctor to figure out what exactly was happening to me.

An Early Misdiagnosis

We made an appointment with the doctor, and when the day finally came I was so excited. I wanted someone to tell me I wasn’t crazy and the feelings I had were valid. That did not happen.

When I started to explain to my doctor what was happening, he said I did not have misophonia (keep in mind, he had never heard of it before), but rather it was my hormones that were out of whack. I was starting puberty, and that seemed like the safe answer. Not wanting to accept that I had a brain disorder, I

A recent graduate in marketing and communications, Kadyn Thorpe is sharing her story so others can understand what misophonia is.

agreed with him. In order to “normalize” my hormones, my doctor put me on the pill. Yes, the birth control pill. I was 12.

As many people know, birth control messes with your hormones, especially when you keep changing it, and we did. Every three or so months, I changed my birth control. I would change it, be off it for a couple of months, and then back on another one. I was young, so I didn’t know taking the pill at the same time every day made a difference. I would forget one night and take it in the morning, I would skip days on end because I just didn’t care enough to continue it.

It messed with my emotions, I was depressed to the point where I didn’t want to get out of bed, I lost all my interest and hated everything. I fought so hard to go back to being the person I was before, the happy-go-lucky girl I used to be, but I couldn’t. And they just kept me on the pill, changing it every time I had an issue. My emotions got worse and my reactions to triggers stayed the same.

Once my family understood, minimally, what was happening to me they tried so hard to stop smacking their lips while they ate. We bought paper plates and plastic silverware to use during dinner time. They stopped eating salads, popcorn, chips, and other crunchy foods. They did everything right, but my triggers would surround me no matter what. At school, I would take a test in a silent room while the person next to me smacked on a piece of gum. Movie theaters were a nightmare—the crunch of the popcorn, the wrestling of the candy wrappers, the groups of people whispering. I refused to go.

These noises happen everywhere, and when you have misophonia, they are louder than normal. People can usually tune them out or they don’t even notice them. When you have misophonia it’s like these are the only sounds you hear, and once you hear them, you can’t drown them out until they stop.

A Diagnosis

Finally, more than a year later, we found a doctor who understood what misophonia was. We got an appointment, but my expectations were low. I had been through so much with changing medications, my body changing, and my emotions at an all-time low, all while simultaneously trying to figure out what was happening to me every day.

When I went to see the doctor, they gave me a piece of paper and told me to answer the questions. The questions asked me about certain noises, rating them on how much they hurt to hear and how I felt when I heard them. They asked how I felt mentally and physically on a daily basis and how I decided to cope with the issues I had been having. Once I finished, the doctor reviewed it and pulled me into her office to talk to me. She told me that based on my answers, there was no question that I had misophonia.

Afterward, she decided to give me a hearing test. I sat in a room facing a wall with headphones on and a button in each hand. For 10 minutes they played clicks in my ears, and I had to push the button when I heard it.

When I finished they explained to me that I have near perfect hearing, which is the reason everything was amplified in my head. Misophonia is the brain disorder where noises send you into rage, and the people who have it have great hearing.

She started to explain misophonia to me. For the first time, I had someone who knew exactly what I was going through. The doctor sat me down and told me exactly what was happening to me. She told me that it was like the wires in my brain were crossed, so when I heard these sounds, which she called triggers, my brain took it as a threat, sending me into fight or flight mode.

“It’s similar to your brain’s response to hearing fingernails scraping down a chalkboard,” she explained.

Then came the bad news—the news that there is no cure and that there is no good way to help this; I just have to

These noises happen everywhere, and when you have misophonia, they are louder than normal. People can usually tune them out or they don’t even notice them. When you have misophonia it’s like these are the only sounds you hear, and once you hear them, you can’t drown them out until they stop.

live with it. Not to mention that this brain disorder causes people to develop depression and anxiety.

The next thing she said I remember perfectly. She told me how many people who have this disorder decide that it isn’t worth continuing, because they are having to deal with the fear of going anywhere, the fear that these emotions are going to take over your body simply because someone near you is just existing.

She told me, “I want you to know, your life is worth living, even if you think it’s too hard.” Those words have stuck with me since.

Living With Triggers

Although there are no cures for misophonia, there are ways that the noises can be limited. For me, it was hearing aids. These weren’t normal hearing aids—obviously I didn’t need noises to be louder; I needed them to be gone. These hearing aids played “white noise” in my ear, attempting to drown out my triggers, but it didn’t work. I could still hear. The triggers were quieter, yes, but not gone. Those emotions were still there, swallowing me whole.

As the years went by I figured out the places I couldn’t go to and stayed clear. I haven’t been to the movie theater in over five years. I tried a couple of times, but it always proved to be a bad idea. I would be begging for the movie to end so I could get out of there.

By no means did this ever get easier for me. I still have to muster up the courage to go to restaurants, stores, work even. Triggers surround me every day, and I have to act as if nothing is wrong.

I started keeping it more of a secret. I didn’t tell a lot of friends, and still to this day haven’t told many of my family members. I didn’t want to be treated differently. My family did everything they could to make me feel comfortable. But rather than me feeling loved and understood, I felt guilty. I didn’t want anyone to change their ways because I couldn’t

deal with the sound. Even though the emotions and my reactions to triggers were valid, I still felt that I shouldn’t be upset by this—that these noises are a part of life, and I should appreciate that I could even hear. But I didn’t.

It’s been almost 10 years since I was diagnosed, and although the emotions my triggers bring are still the same, I can try to control them because I’ve accepted that this is something that is a part of me. I can’t change it and it will never go away, but I can make it my story. I can share the obstacles I’ve had to jump through in order to come to terms with what having misophonia means.

I can share my story with people who feel the same way. I can share my story with doctors, who would otherwise think these reactions and emotions are because of changing hormones. I can help people who, just like me, wanted validation, and didn’t get it for far too long.

I wrote this so people can understand what it’s like figuring out misophonia. By no means do I believe that this is how everyone’s misophonia story goes, but this is mine. Being able to understand misophonia is the first step to understanding how to diagnose it. Although misophonia is not as prominent as other brain disorders, it’s still here. It’s still impacting lives every day not only for the people who have it, but their friends and family as well. It’s not puberty, it’s not out of whack hormones; it’s a brain disorder that needs to be addressed.

Kadyn Thorpe lives in Colorado.

The doctor started to explain misophonia to me. For the first time, I had someone who knew exactly what I was going through. She sat me down and told me exactly what was happening to me. She told me that it was like the wires in my brain were crossed, so when I heard these sounds, which she called triggers, my brain took it as a threat, sending me into fight or flight mode. “It’s similar to your brain’s response to hearing fingernails scraping down a chalkboard,” she explained.

Spotlight On: Litao Tao, Ph.D.

Hearing Health Foundation’s Hearing Restoration Project welcomed its newest member to the consortium in October 2022. Litao Tao, Ph.D., received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at China’s Tsinghua University and his doctorate at University of Southern California, where he also did postdoctoral studies. An assistant professor in the department of biomedical sciences at Creighton University in Nebraska, Tao is part of the HRP’s Cross-Species Epigenetics working group.

What is your area of focus?

We are interested in the role of epigenetic repression (i.e., chromatin architecture and histone modifications to block gene expression) in the silencing of sensory hair cell programming in the supporting cells of the mammalian cochlea. We hypothesize that in mammals, the epigenetic silencing state of hair cell genes in supporting cells hampers reactivation of those genes and hence blocks the conversion of supporting cells to hair cells, one major hair cell regeneration mechanism found in non-mammalian animals. Investigation of the epigenetic regulatory mechanisms not only helps us understand the failure of sensory hair cell regeneration in humans, but also provides potential targets for us to manipulate the epigenetic status of genes to stimulate gene expression for hair cell regeneration toward hearing restoration.

How did you decide to get into scientific research?

Chinese Taoism teaches that every movement or change in the universe is dictated by certain rules ( ) and that people become powerful if they understand those rules. When I was a little kid, I was fascinated by Taoist stories, and I started to pay close attention to natural phenomena and wanted to understand the rules behind them. Expectedly and unexpectedly, I found myself interested in science and became a scientist instead of a Taoist.

Why hearing research?

The first time I saw the structure of the human cochlea, I was immediately drawn by the delicate structure and the beauty of sensory hair cells. On top of this, I had the good fortune to work with the late Dr. Neil Segil, who was a member of HHF’s Hearing Restoration Project. Dr. Segil welcomed me as a Ph.D. student and encouraged me to study hair cell death induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics. From these ototoxicity studies conducted in the supportive environment of the Segil lab, I developed a fondness for the science of the inner ear.

Tell us about the most exciting parts of your work. Compared with other tissues and organs, the cochlea presents unique challenges in order to be studied. This tiny organ is buried in a bony structure and contains a limited number of specialized cells. Implementing new techniques and designing novel experimental approaches to overcome these challenges is an ongoing journey in hearing research and an essential part of the job, without which many of our biggest questions would be difficult or impossible to address. The most exciting part of our work is seeing results generated successfully with these new techniques and approaches, regardless of whether they support or contradict our hypotheses.

Describe a typical day. After dropping my daughter off at school, I begin my workday catching up on email correspondence. Then I walk into the lab to greet my lab members, and if I don’t have a lecture to give, I’ll discuss experiments with them. Next, I spend an hour or two putting together lecture materials, analyzing new datasets, or preparing presentation slides. Lunch is usually followed by student presentations, journal club discussions, seminars featuring an invited speaker, or department meetings. I spend most of my time in the afternoon in various meetings and discussions with students, lab members, colleagues, and collaborators. After finishing up any paperwork, and reading and sending a few more emails, I say goodbye to the lab and head home. When it gets dark, I spend my evenings playing basketball or jogging for a little while, and then enjoy some reading or writing before bed.

Tell us about something you enjoy doing outside the lab. I like fishing. I used to go deep sea fishing or surf fishing once a week when I lived in Los Angeles, and now I am exploring the fun from lake fishing and river fishing in the Midwest. Staring at the float or pole tip quickly isolates me from the surrounding environment so that I can think about something without interruption from the world outside. Of course, the bites from fish always pull me back to the real world.

How has the collaborative approach helped your research?

The HRP’s collaborative effort from multiple groups working with a variety of species makes it possible to address this intriguing and important question: why the mammalian cochlea lost the capacity to regenerate sensory hair cells, while robust hair cell regeneration happens in non-mammalian animals.

What do you hope for the HRP over the next few years?

The HRP brings some of the greatest minds in auditory science together, supporting many diverse projects by encouraging collaboration and cooperation. This unique platform has greatly accelerated hearing research and played a significant role in advancing our knowledge of the inner ear. Over the next few years, I would like to see more resources allocated to projects geared toward the translational aspect of hearing research, with themes such as drug screening, gene delivery, and expression manipulation for potential therapeutic treatments. Of course, we cannot make this happen without the continued support from HHF and its generous donors.

Chinese Taoism teaches that every movement or change in the universe is dictated by certain rules and that people become powerful if they understand those rules.

Not Everyone Qualifies for OTC Hearing Aids

Relatively basic over-the-counter hearing aids, indicated for mild to moderate hearing loss among adults, may end up pushing features like directional hearing and telecoils into prescription hearing aids for more severe types of hearing loss.

By Stephen O. Frazier and Hansapani Rodrigo, Ph.D.The intent for the over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids that made their debut in October 2022 was to serve the needs of adults with a mild to moderate hearing loss. The models range from the very basic to those having a variety of advanced features such as Bluetooth capability, directional mics, rechargeability, smartphone apps, and even telecoils. Consumer sales will make the final determination as to what attributes in hearing aids and their accessories are important to this subgroup of the nation’s nearly 29 million people the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders says could benefit from being fitted (if they are not already) with hearing aids.

The Survey

Adults with a hearing loss greater than mild to moderate will still need to be fitted with prescription hearing aids to adequately address their condition. A 2021 survey holds insights into what features this group wishes to have in their hearing aids.

Nearly 15,000 hard of hearing participants who have varying degrees of hearing loss and all age groups participated in a 21-question survey, conducted by Vinaya Manchaiah, Ph.D., and colleagues, with the results published in the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology.

The responses to the survey were also used online in a different report by Abram Bailey, Au.D., and team on Hearing Tracker. Hansapani Rodrigo, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley,

Oppopsite page: Listed in order from top to bottom, these are the attributes that people with severe to profound hearing loss want in their hearing aids.

collaborated on the original study. She provided the statistics on the 4,027 survey participants who had a severe to profound hearing loss—that is, those who don’t qualify for OTC hearing aids—for this article.

The Results

According to the report in the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, the four most common attributes identified as “extremely” or “very” important for the overall group—those with hearing loss that ranges from mild to moderate to severe to profound—were:

» improved ability to hear friends and family in noisy settings (88.3 percent)

» reliability (85.1 percent)

» improved ability to hear friends and family in quiet settings (75.3 percent)

» physical comfort (74.3 percent)

For the severe to profound (S/P) group, the top four attributes rated “extremely” or “very” important were:

» improved ability to hear friends and family in noisy settings (88.9 percent)

» reliability (85.8 percent)

» improved ability to hear friends and family in quiet settings (84.1 percent)

» improved hearing on mobile telephones (71.2 percent)

Not surprisingly, both the overall group and the S/P group rated ability to hear well in noisy settings as the

most important attribute desired in hearing aids. But the S/P group seems to have more difficulty hearing even in quiet settings compared with the overall group. Reliability was more important to the S/P group, as was being able to hear well on cell phones.

Streaming audio, whether from a mobile phone or TV, ranked higher in the minds of the S/P group than the full group and stood at 54.3 percent for mobile phone streaming (versus 48.5 percent for the full group) and 51.6 percent for TV streaming (versus 45.5 percent).

The S/P group was less concerned about the visibility of their hearing aids (33 percent) than was the full group at 44 percent.

As for the ability to recharge the devices, it was less important to the S/P group at 32 percent than to the full group who rated it at 39 percent. Surprisingly, in this increasingly technological and digital world, the ability to control hearing aid volume and settings using a smartwatch was almost equally unimportant to the two groups, with the S/P group at less than 12 percent and full group at 15 percent.

Of Loops and Microphones

Being an advocate for hearing loop technology, I was disappointed that just 27.9 percent of all respondents felt that the ability to receive audio broadcast by a hearing loop through their hearing aids was important. Among the S/P group, 35 percent indicated this often ignored technology is still an important capability—and I consider this group, because of their greater hearing loss, to be more hearing impacted and therefore more experienced hearing aid consumers.

It is also worth mentioning that telecoil-equipped hearing aids and a cell phone with a jack for a neck loop would help those who wish for the ability to better converse on cell phones.

Even my audiologist was not aware that many remote microphones now, in addition to streaming sound they “hear,” contain a telecoil. This means they have the capability to stream the sound from a hearing loop directly to hearing aids that don’t have telecoils using Bluetooth. Among the S/P group, 26 percent felt the availability of this kind of remote microphone was extremely or very

important, versus 21 percent of the overall group.

Another thing to point out is that since the ability to stream sound to hearing aids from a variety of sources was rated very important by so many respondents, streaming is almost a “must have” for hearing aid buyers. For the many hearing aid wearers whose devices do not contain telecoils, the advent of remote microphones such as Starkey’s Remote Microphone Plus can ensure improved communication access since these remote microphones can connect to hearing loops. The Oticon EduMic not only has a telecoil, it can also connect to the signal from an FM assistive listening system.

Questions Remain

OTC hearing aids may shrink the overall size of the client pool for prescription devices but have little or no impact on the group whose hearing loss is severe to profound, who will continue to need to purchase prescription hearing aids.

Will the price of prescription hearing aids go up to make up for income lost to OTC competition? Will other hearing aid makers join Starkey in developing an OTC hearing aid? Will the features the S/P group both want and need be discontinued in order to lower the price to compete with the new OTC kid on the block?

Will the burgeoning online sale of all types of hearing aids (OTC and prescription) result in less availability of inperson care from a local audiologist or hearing instrument specialist? Will more hearing care offices unbundle their services to treat online and OTC hearing aid buyers?

We’ll continue to monitor the hearing aid market and optimistically hope that the greater accessibility and affordability will benefit all.

Trained by the Hearing Loss Association of America as a hearing loss support specialist, staff writer and New Mexico resident Stephen O. Frazier (left) has served HLAA and others at the local, state, and national levels as a volunteer in their efforts to improve communication access for people with hearing loss. Contact him at hlaanm@juno.com. For more, see sofnabq.com and loopnm.com.

Hansapani Rodrigo, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at the School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, in Edinburg, Texas.

For references, see hhf.org/winter2023-references.

Share your story: What is your top must-have in hearing aids? Tell us at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

Being an advocate for hearing loop technology, I was disappointed that just 27.9 percent of all respondents felt that the ability to receive audio broadcast by a hearing loop through their hearing aids was important. Among those with severe to profound hearing loss, 35 percent indicated this often ignored technology is still an important capability—and I consider this group, because of their greater hearing loss, to be more hearing impacted and therefore more experienced hearing aid consumers.

Educate, Educate, and Advocate, Advocate

By Pat DobbsI grew up with typical hearing, but now I rely on my bilateral cochlear implants to hear. So although I live in the hearing world, I sometimes feel like a ghost, hanging around but unable to participate when I can’t follow conversations.

I’ve been learning how to do something about it. It’s a simple lesson that I must remind myself to keep practicing: Advocate through education with a good sprinkling of humor and persistence.

Here’s how.

When eating out. I ask my dining companions to look straight at me when they talk, speak louder (and maybe more slowly wouldn’t hurt), and try to speak one at a time. Most of the time, my friends react positively to this—after all, they want me to hear them.

It’s a pain to remind them when they forget, which inevitably happens, but I’m getting over it. I need the education and patience as much as they do.

When in a public venue. Interested in attending a play, lecture, or movie? What about a school board meeting? In theaters, auditoriums, and lecture halls, it’s not a question of interacting with your companions. It’s a technology problem. Many venues have not installed the assistive listening devices that have been such a boon to the hearing loss community. In this case, advocate and educate.

Call the theater or meeting place ahead of time and ask about the accommodations they have made for people with hearing loss.

And please be respectful if they tell you there will be a sign language interpreter available.

Ask if they have installed a hearing loop, which will work with your telecoil-enabled hearing aid or cochlear implant. Or maybe they have an FM or IR system. If they do, where are the devices? How often do they check or test them? You don’t want to end up at a place where the technology is present but broken or inoperable.

When there is a screen. Another accommodation is captioning. My preference is open captions, where the captions are displayed on the screen so your eyes focus in one place. Some theaters and other public venues display closed captions on your tablet or phone, which is better than no captions at all, but your

One tip: Call the theater or meeting place ahead of time and ask about the accommodations they have made for people with hearing loss.

focus must go back and forth.

When I go to see a play, I tell patrons around me I’m using my tablet for the captions. After all, I don’t want to create the embarrassment recently experienced by an actor on Broadway who mistakenly called out a patron with a hearing loss for using her tablet; the actor thought she was recording the performance.

When, more broadly, you need to remind folks it’s the law.