Studies in Contemporary Architectural Theories

‘Clouds of Architecture’ and Other Stories

Led by Dr. Ella Chmielewska

Hazwan Husain s2530103

My warmest appreciation to Dr. Ella Chmielewska and her eloquent navigation in chartering through the constellations of this unit.

My gratitude also belongs to Alex, Giulia, Fergal, Daisy, Diana (M), Diana (H) and Natalia for their contribution and companionship throughout the seminar and conversation.

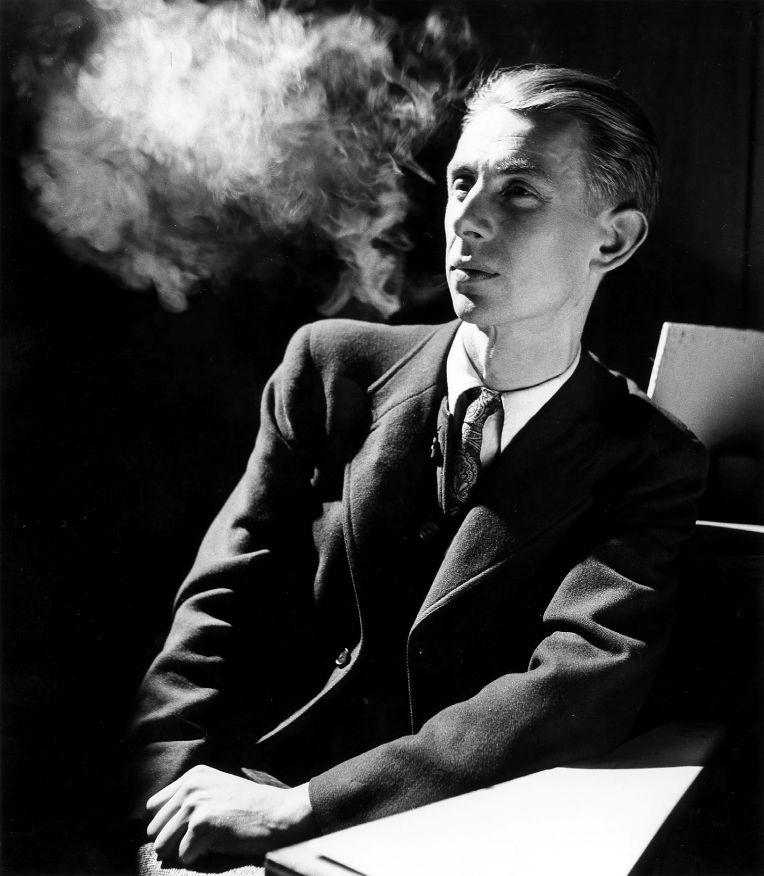

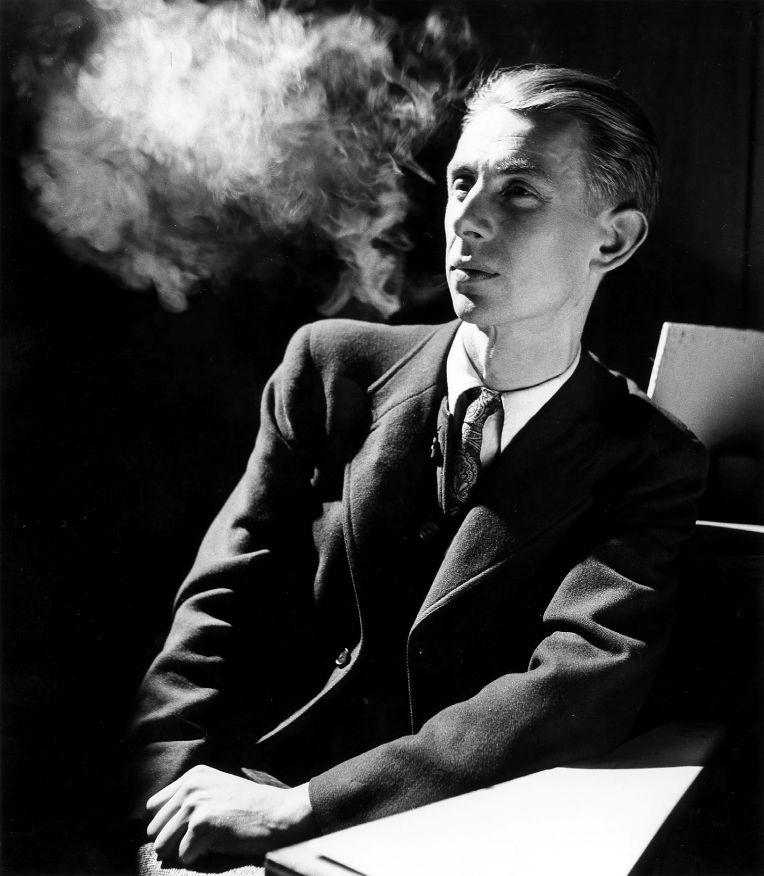

Mark Dorrian,

The photograph is a haunting image, which might also be thought [of as] an image of haunting. (1) The chiasmatic interplay of words established the departure of his writing by capturing the details using rhetorical devices and precision in describing the Lee Miller Photograph. What seems to be a delicate move is the way of how Dorrian opens the research and branching out the ideas drawn from the image. He started by describing the image, writing on the image as a starting point and then branching out towards further his research: -

strong light falls across from an unseen source to the left of image, casting his shadow on what seems to be a narrow table-top upon he leans, his posture drawing his shoulders down towards the shadows. his head is tilted slightly upwards, we would probably say that he was staring into space were it not for the strange, illuminated cloud suspended before his eyes like an apparition in the darkness. (1)

His description opens the border of ideas, making the border of the image not porous and extended the airy, floating and suspended nebular effusion, hinting on an idea of ambiguity. Perhaps the contrasting character of the image itself hints on the liminal quality; black and white, sharp lines and liquid-like object, tense figure yet the same time, a relaxing pose. The presumably cloud of tobacco smoke becomes the object of interest and flowed the sense of what the photograph might be understood to do. (1) He associated this frontispiece with the concept of Vanitas imagery, drawing out the smoke’s presence as an idea, being a form of cultural iconographic and use it to expand other examples of Vanitas imagery.

Branching from the given description, the undulating smoke is associated as a “ghostly” figure, initially thought to resemble a human head but the mysteriousness of how it appeared and the sensual experience that it portrayed hinted Dorrian to expand this image of contemplation of latency. Dorian condensed the cultural iconography of the smoke in two positions, expanding on the chiasmus that he described earlier – the materiality state and experiential aspect of a cloud, or as he quoted, the hermeneutic or interpretative atmosphere. The cloud always in constant changes, always in motion, in constant transposition of spaces and morphing its shape, responsive to the moment in the air. The cloud could be captured in the moment but never outside of it. The smoke gives rise to an effusion-or even a billowing – of connotation that cannot be particularised. The state or condition of the “atmosphere”.

The experiential aspect of the smoke is characterised by the feeling subjected to the effect or influence of a presence that are unable to be otherwise determined or located. (2) - This interconnected relationship between the state of being and experience implicated is what Dorrian describes as the way how the photograph conveys the contemplation of material atmospheric phenomena and is itself carefully attuned to produce an effect that we can rightly call ‘atmospheric’.

A haunting image and an image of haunting. The atmosphere as a being and the atmospheric as a feeling.

2 — (Non-Native)

A

that potentially

the

and atmospheric

through it’s

and

the body’s envelopes and sacs, everything of the kind required for breath to be retained, held under pressure, and issued.

The symbolic attack here signifies that removal of ground, or foreground which Dorrian build up upon Steve’s Conner establishment of the skin as a background, to which things adhere to, integrate and cohere. The idea of skin as an envelope in which Steve Connor and quoted by Dorrian1;

…it [The skin] is a fundamental condition is to be that on top of which things occur, develop or are disclosed. The skin is the ground for every figure. Perhaps the skin means, more than anything else in particular, the necessity for there to be:

a ground, a setting, a frame, an horizon, a before, a behind and underneath

Removal of the skin means removing the invisible surface to which rules and norm adhere to. The skin or envelope represents a double-faceted connotation as both foreground and background existed in the same plane and mutually integrated.

I’d like to bring the analogical thoughts and impose this paradox onto the first part of the passage that Dorrian excluded from Steve’s quote2 ;

If there were one function of the skin that might seem to unite or underlie all the others, it would be that of providing a background. Like the cinema screen upon which images play, the canvas on which paint is laid , or the paper on which words are scrawled or stamped, the skin is always in the background. [and being the foreground]

2 — (Non-Native)

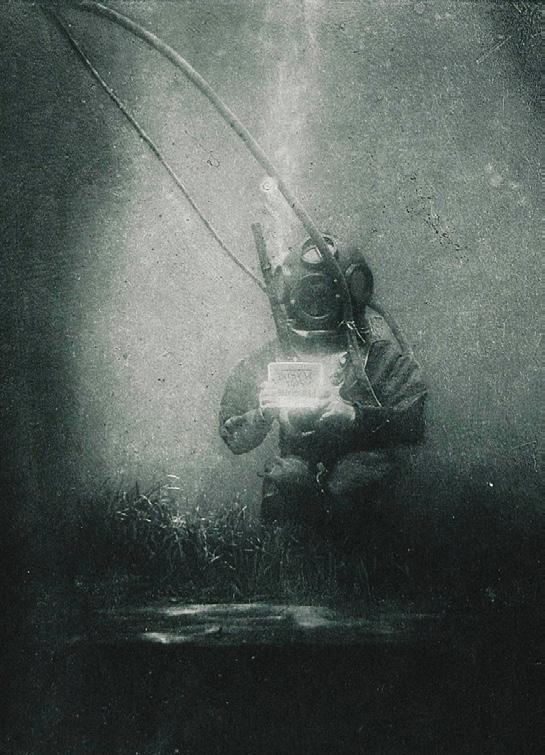

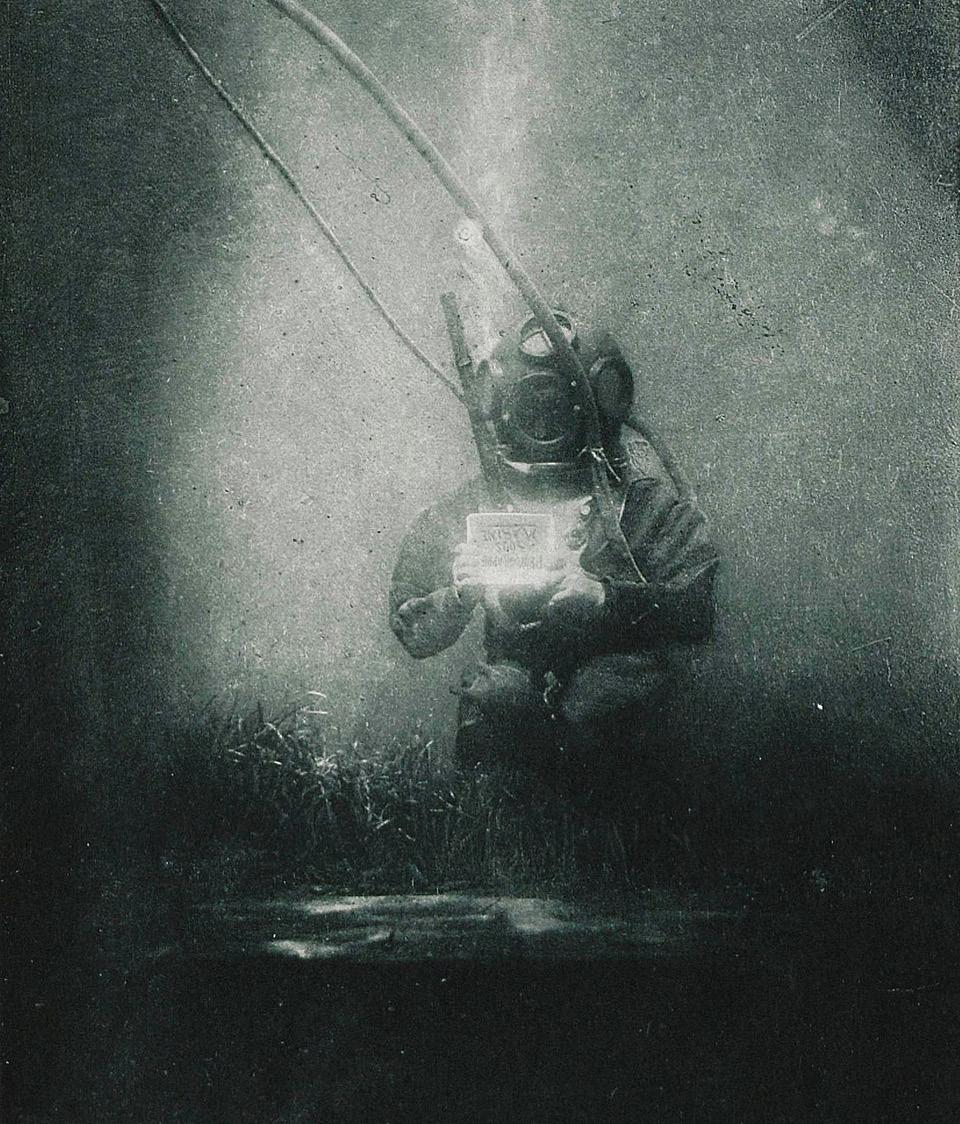

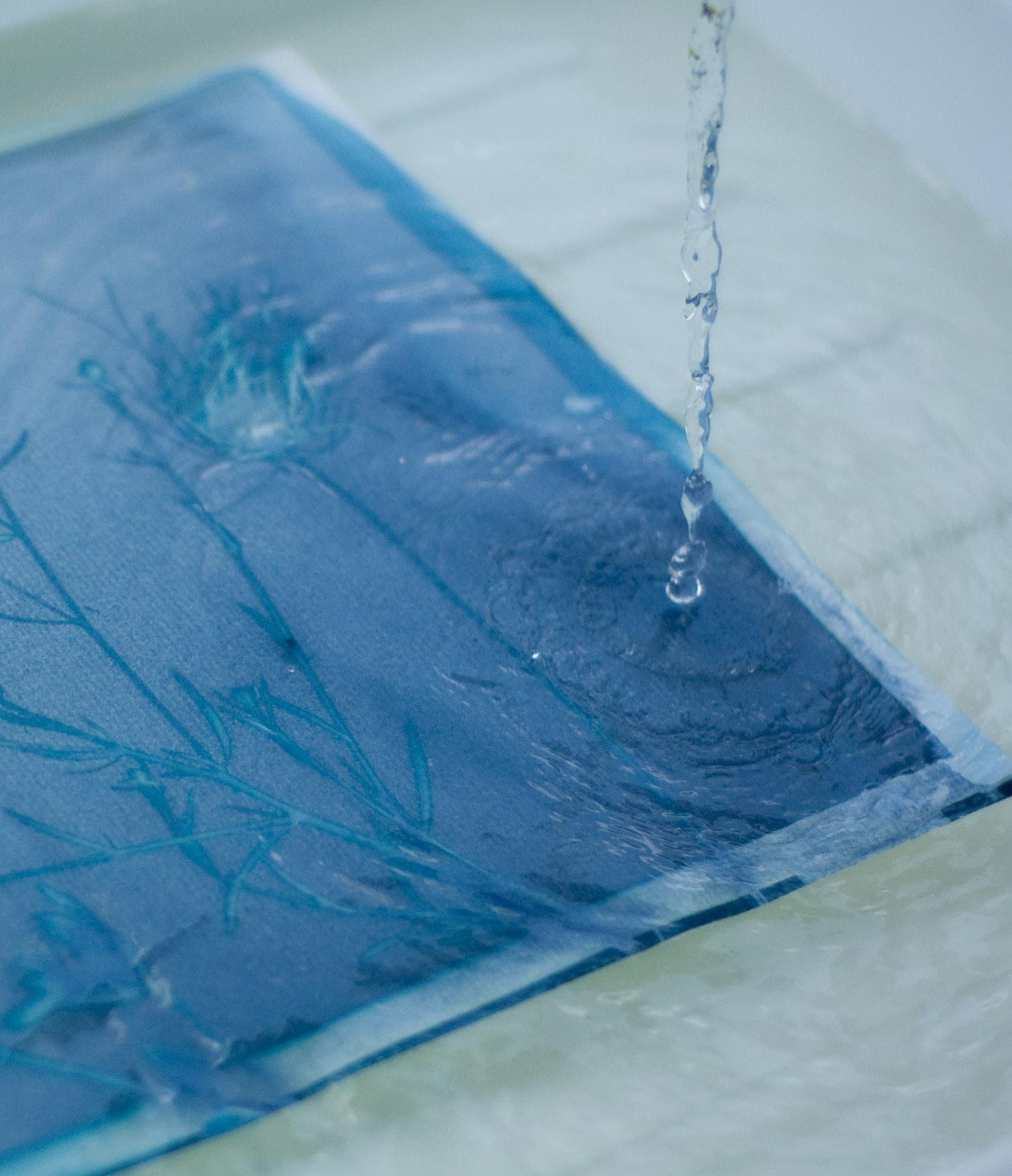

A Photograph of creating a “cyanotype” , a camera-less photographic printing process that produce Prussian blue images by using light-sensitive chemicals and sunlight, hinting at the idea of a surface being a background and a foreground through a (semiotically) self-torning process, Photo : Jodimichelle/ flickr, 22 June 2010

David Shapiro

in John Hedjuk’s The Collapse of Time and Other Diary Construction (London : Architectural Association,1987) np.

Architecture demands a film, not a model – Shapiro quoted in the Clock of Deletion, which then he suggested that John Hejduk seems to be the only architect who understands the temporal poetics of architecture as an essential and necessary part of the act of refuge. Hejduk’s clock structure is described as restless clocks embeds time and shows its contradictory potential, a homage which he draws from Shaffer’s idea on the duality nature of a clock.

The clock is a cabinet for death; Clocks are historically less significant as time-measuring devices than as model of the universe. This discrimination, as he quoted, framed Shapiro views on Hejduk’s work of the clock. The idiosyncratic blending of private and public space allows Hejduk to make a [clock] which is something that is portable as timepiece [time-measuring device] and turned into something as monumental as an obelisk [model of the universe]. Understanding this dichotomy unfolds the idea that architecture is both static and temporal at the same time. An overlapping function of between an obelisk which are static, allegorical, emblematic and a public clock; functional, systematic and austere.

Hejduk portrays these contradictory potentials through three components that make up the structure as a whole “system” to be understood as representative model that enunciates the analogy as a species of habitation for time. I’d like to expand on the term that Shapiro used here, as it gives a strong impression on how clock is conceptually seen as device to habituate or houses; it doesn’t contain the time, but it positions time in a traceable spectrum.

* All quotes are from David Shapiro, “TheClockofDeletion:TimeandJohnHedjuk’sArchitecture,” in John Hedjuk’s The Collapse of Time and Other Diary Construction (London : Architectural Association,1987) np

The temporality or plasticity of time is represented in the analogies of the descent of time and the positions of which the person on the chair is viewing the descension. From vertical; ‘flat time’ to a 45° angle or ‘isometric time’ to 0° or horizontal time’. Shapiro credited Hejduk as a great master-builder of metonymical distortions and lexical fiction as such the clock is both the representation of a clock and negation of all measuring devices. This idea is then expanded by Shapiro’s association of memento mori or vanitas as the strategy that Hejduk used particularly in the usage of readymade railroad wheels and spectral of no-colour of the monument that tragically express the tower becoming its own death bed. As the clock is meant to be descended and moved from a place to a place, from time to a time, the usage of the wheels enables this structure to be dislocated and displaced from its original position. of time in any measuring devices, moving and shifting in a cyclical manner until it reaches its own tragic end; it’s death.

This allegorical movement is meant to be part of the larger stage-set, a model of multiplicity as Shapiro described, to be read together with two other structures: the security and booth. There is a kind of ambiguous fog that still alludes me to read and understand this representative model, the clock tower in relation to its other two counterparts. Perhaps that is the possibilities of perspective mentioned by Shapiro in the opening and how Hejduk addressed his persistence of time; present time cannot be seen…present time has an opacity… present time is opaque…present time erases…black out time…

Mark Dorrian, in Writing on the Image: Architecture, the City and the Politics of Representation (London: IB Tauris, 2015), pp. 107-118.

There is a moment in Dorrian’s radio essay where he speaks of a photograph that holds the dust, which unfolds to be a captured as instances of suspension and becomes a symbolic image. His intention to explore the architectural aspiration for cloud might be understood as an attempt, a test trial to grasp the idea of “cloud,” despite the irony that the true nature of cloud is ungraspable. A kind of classic chiasmatic play by Dorrian, as seen in his other essays. Dorrian quoted Hubert Damishes’ characterisation of cloud as “matter” aspiring to “form,” thereby registering its infinite provisionality and imminence. By seeing this as a consequential relationship, he added that cloud could equally be thought as “matter after form,” the characteristic “thing” that accompanies destruction and demolition, a trace of something that once held a structure. The dust happens for a moment and then dissipates.

The dispersion and suspension of particles that follow the convulsion of matter. As physical as it could be, this dispersion and convulsion could also be seen through the rhetorical and political grounds that follow destruction and demolition. It is a result of an undoing. Such examples would be the two famous examples of architectural undoing that Dorrian highlighted in the text, but they stemmed from distinctly different causes and were curiously designed by the same person. 1

In the case of the Pruitt-Igoe demolition, the destruction was planned to facilitate a better condition. The housing blocks could no longer be sustained in their current condition, albeit being ‘Clouds

* All quotes are from Mark Dorrian, ‘Clouds of Architecture’ in Writing on the Image: Architecture, the City and the Politics of Representation (London: IB Tauris, 2015), pp. 107-118.

relatively new. The cloud here is, indeed, a representation of the systemic flaw and resembled an end or death towards modernistic views of architecture, famously promoted by Charles Jenck; as a death-rattle of modernism itself. The cloud could be traced as an icon that registers the collapse not just on a specific project but of an entire ideology.

A similar situation could be seen through the recent demolition of the three multi-storey buildings at 11, and 191 Wyndford Road in Glasgow. The debate around rationalisation behind this demolition, whether politically and economically motivated, remains ambiguous like the cloud dust formed in the aftermath. One could draw the idea of the provisionality of the cloud being imposed on the shifting densities implied in this development scenario. As the cloud shrinks, dissipates, and disperses, so do the 600 units that were flattened to pave the way for 400 units to be emerged in its afterlife (with its planning permission voyage have yet to be seen)2. Despite the shrinking of density being the subject of constant debate, it renders the idea of buildings and architecture being in a constant state of morphology.

Perhaps this might be symbolic of Coop Himmelb(l)au’s description of the cloud as a soft, fluctuating enigma – a building that does not want to be a building anymore. It moves, drifts and wavers… a product of a complex tissue of influences in which it constantly recreates itself... is entirely without identity... Always in the drifted in-between.

1 The other one being World Trade Center, designed by Minoru Yamasaki

Leslie, C. (2025).

‘The

King in

Mark Dorrian, in Writing on the Image: Architecture, the City and the Politics of Representation (London: IB Tauris, 2015), pp. 13-21.

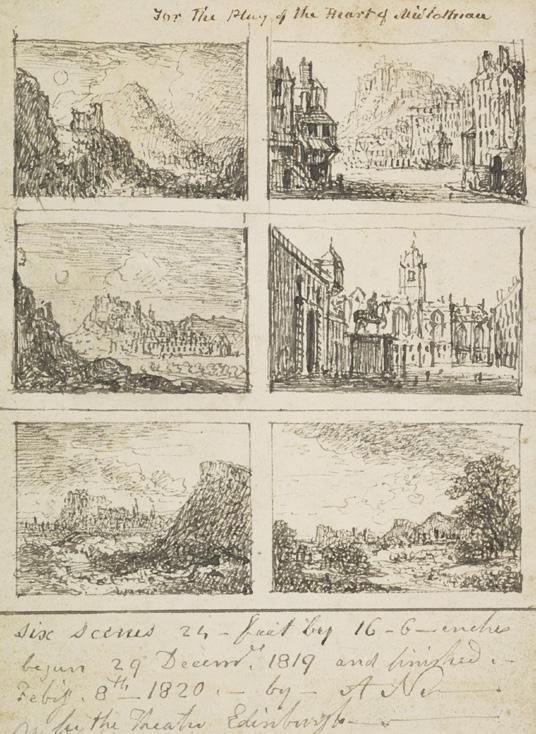

The city is a series of living stages. The treatment of the city in its presentation to the king as a sequence of tableaux [living stages] seems in some ways anticipated in the dramatic rendering [or accentuating] of Scott’s work by Alaxander Nasmyth in 1820 for the theatrical play of the Heart of Midlothian (19)

Arranged as series of frames, the stage sets drawn unfold different multiple visual modalities, positioned and composed as a sequence of theatrical and symbolically loaded tableaux. (14) The frames capture the panoramic visual field of the city, frozen and alive at the same time, influenced by the sense of association. In Dorrian’s word, association, through the vehicle of imagination shifted us [viewers and the viewed] away from the immediacy of the object and the empirical content of perception; the imagination characterised the frames into context and contrarily work similarly in contextualising the frame.

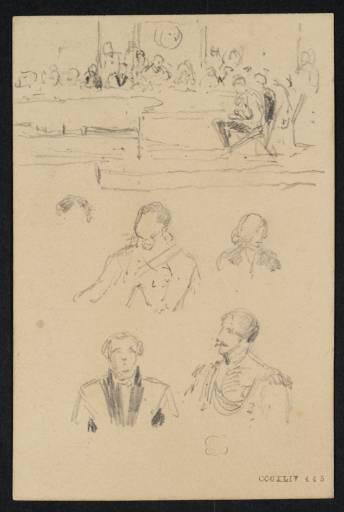

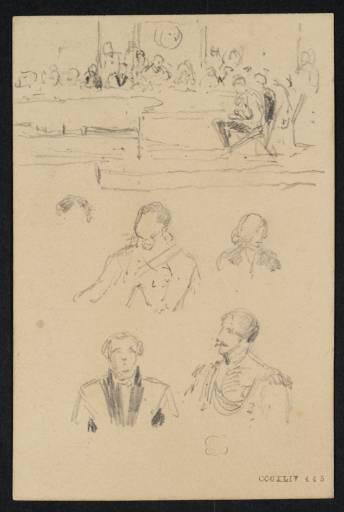

On a closer examination of the thumbnail sketches by JMW Turner; the people, decorations, tables and backdrop were being drawn in extensive details. This emblematisation of the body of king and its citizenry (14) were consciously located within notional pictorial series (16) – giving a sense association, a context. The contextualised frames attempted to capture the spectacular(s) in which both the king and the city were mutually staged in relation to one another. The association between the viewers and the viewed hinted at the city as a temporal stage, being fabricated and constructed for the king. This recto verso works similarly with the

— * All quotes are from Mark Dorrian, ‘‘TheKingintheCity:TheIconologyofGeorgeIVinEdinburgh,1822’ in Writing on the Image: Architecture, the City and the Politics of Representation (London: IB Tauris, 2015), pp. 13-21.

20

king being addressed and decorated for the city [and its citizens] for viewing the king. This chiasmus, as Dorian described in the text, entailed a very specific structure of spectatorship. The king observed the city and the city watched the king, watching it. (14)

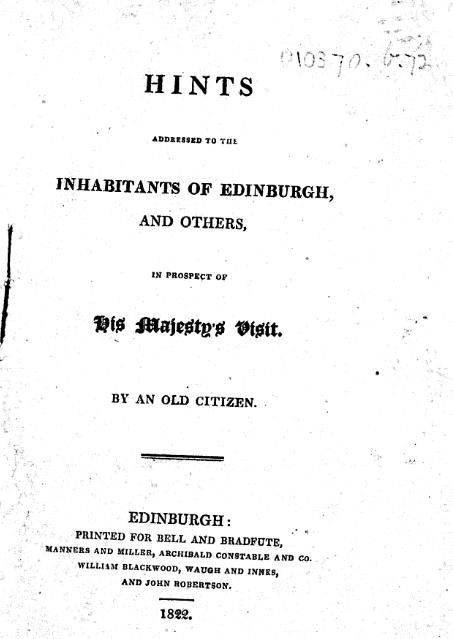

Dorrian deliberately compared the sequence of tableaux based on the two distinct accounts of the visit. The first one being the record of Scott’s stage-direction, the Hints1, a pseudonymous behavioural guidebook by “an old citizen” that turned out to be openly known for Scott’s own writing. This piece contains the rendition, associative plan of Walter Scott’s on how the city and the citizens would be fabricated, as a view for the king.i

The second account 2, which Dorian quoted “powerfully conveys the serial tableaux-like quality and gives us the impression of a sequence of pictures” (15) mapped the cities in the form of textual assemblage that could be rendered down and gives the impression of a series of picturesque frames:

A new scene opened upon view of the august Stranger

At every step of his progress towards the palace of his ancestors.

A number of street diverge from the head of the magnificient avenue by which he had entered the city, The route through it on which he had now entered is of a spacious breadth, And lined with with noble buildings; The long ranges of palaces to the north, And in front… were succeeded in diversified panorama

1 (Walter Scott) Hints Adressed to the Inhabitants of Edinburgh and Others, in prospect of His Majesty’s Visit, by an Old Citizen (Edinburgh : Bell and Bradfute, etc. 1822) also in Fig. 3 —

2 (By an eye-witness of most of the scence which were the exhibited)

It was during our reading of The King in The City that we were tasked to go out for a walk, one of the early weeks of our seminar.

“Walk along (what could be part of) the route taken by King George IV in 1822, and think about the semiotically charged optical events or visual situations, and the rhetorical figure of chiasmus deployed by Dorrian.”

At that particular moment, I had yet to fully understand or grasp the idea of chiasmus. What instantly came to mind, however, was of a personal bias; an idiom from my native language, Malay:

RajaSehari, literally translated as, “the king for a day”, It is a phrase used to denote the bride and groom on their wedding day. In our local wedding tradition, the couple is dressed in traditional attire, the type of which were once only reserved for Sultans or Kings. It is a gesture ,or rather, a staging meant to celebrate their special day with symbolic grandeur.

Little did I know then, this tradition is a subtle but poignant example of chiasmus in play.

As I walked down the street, the only thought lingering in my mind was: “What if… I envisioned myself as thekingfortheday?”

A frame, after a frame, after a frame, after a frame, after a frame of the city unfolds upon me, or it was I who was unfolding the frames as I walked along the route (that may have been) taken by the King George IV in 1822. The frames through which I unfold, or which unfolded upon me, were devoid of any orchestrated staging, romanticised temporary erections, triumphal arches or costumed citizenry as described in the many accounts that documented the king’s visit.

This superimposed description of photograph that I took at the end of Constitution Street appeared to be of a constracting quality to the textual reconstruction from an accounts that Dorrian directly quoted in his essay, powerfully conveys the serial tableaux-like quality of the unfolding city and gives us the impression of a sequence of pictures 1:

A new scene opened upon the view of the august [automotive] at every step of his progress towards the place of his [examination]. A number of streets diverge from the head of the [mundane] avenue by which he had now entered is of a [narrowed] breath, and lined with [ordinary] buildings: the long ranges of [renovated tenements, with a one particular distinct blue-painted shopfront] [along the edges of the streets] and in front… were succeeded in diversified panorama by the [ordinary accumulation of overhead tram lines, traffic lights, street devices and road signages] . On the other hand was the [double decker bus] towering in [the crowded bus stop], fitted [to accommodate multiple passengers]…These objects, as he passed in succession under his [seminar tutor’s instruction] , evidently [perplexed] his admiration : and at last, when he came in full view of the [retail buildings] of [Newkirkgate Shopping Centre at the end of Constitution St.], he fairly stood up from the [electric tram] and exclaimed. [“How boring!”] 2

“Boring” or “mundane” is perhaps an experiential consequence of a devoid in association, something that Dorrian implies is transported through the vehicle of imagination. Imagination drives one’s experience to locate the immediacy of objects and the empirical context of perception. ³ The act of walking while thinking through the route is rarely neutral; it is constantly mediated by imagination.

Within my own perception, the frames I encountered were not ingrained with grandiosity or empathy. They were limited by the frame of my imagination as an international student in the city, riding a tram for an assignment tour. The route and the city were staged in a different way as opposed to grandeur or ceremonial spectacle, but shaped instead by the interests of daily rituals, of everyday infrastructures, of buses and shopfronts and not by a triumphal arch.

The vehicle of imagination brings forth a different modality of framing the city. In 1822, citizens might have associated the moment with emblematic sympathy toward the monarchy, a gesture of accepting power and authority which led to the city being staged in celebration of this symbol of power. A symbolic display of body politics 4 enabled the king, as a figure, to ascend to a panoramic view over his subjects, and consequentially allowed the subjects, in turn, to exchange gazes upon the figure of power.

This framing of the city for symbolic power was curiously repeated, almost exactly dated two centuries later 5, when the deceased Queen Elizabeth II was carried in funeral procession through the same city, toward the same destination. (The interval is almost similar betwen Charles II-George IVElizabeth II)

This recent contemporary event of the Queen’s funeral procession mirrored another similar yet contrasting description of the king’s visit 6. Juxtaposing the event onto another direct quotation in Dorrian’s text : -

The intention in referencing this recent event is not to romanticise the funeral procession, as many accounts did with the King’s Visit in 1822, but rather to examine the chiasmatic effect, how the city was staged, and to accentuate the multiple visual modalities exchanged when the city is fabricated for a significant event. While the King’s Visit remains a documented historical fact, Dorrian describes it as a kind of conceptual event in his essay. This synecdoche is mirrored in the Queen’s funeral procession, an event where gazes were exchanged, and both sides of the viewers were staged upon. Just as Walter Scott directed the orchestration in 1822, the City Council released similar instructional guide and visual directives on how the funeral would be staged.8

The idolised King, or a deceased Queen, is not merely regarded as a monarch or an important person, but rather as power itself, or a sign of power. In 1822, the “Crown” was personified through a living monarch during the royal visit, whereas in 2022, it was personified by a deceased monarch during the funeral procession. The “Crown” was viewing the city, as much as it being viewed, as a symbol of the royal system to which its subjects adhered, and toward which they expressed sympathy.

The “Crown” does not signify an actual physical crown but instead situated as an emblem of power, manifested through temporal events in the city, shaped by association and sympathy. These distinct events may be understood as signs of the city (and its citizenry) accepting power or authority imposed upon its existing (social) fabric. This echoes how Dorrian frames the visit as a conceptual event rather than solely a historical fact, an exchange of gazes between the King and the city, both mutually staged and being staged.9

Stages were set up, roads and pathways diverted, subjects gathered and mourned, temporary barricades erected and guarded, flowers laid from Balmoral Castle to the Palace of Holyrood. Association breeds polarity. For some, the staged event represented grief, empathy, and the expression of condolences toward a figure of power. For others, the temporal staging created a barrier, a nuisance, and restricted the movement of the abled body to accommodate the passage of the disabled, or more accurately, the ceased body for permeating through.

The route that once served as the shortest path to a destination was transformed into a kind of circumambulation around the inner city. Bridges flooded with people attempting to cross and resume their daily rites.10 An apparent disturbance to the usual rituals woven into the city’s fabric. The whole city was reshaped and replanted for this temporal event.

Expanding upon the framing of temporal events and the association of power, one can draw from various instances where cities have been staged, manipulated, and altered to serve a particular narrative or strategy. The phenomenon of cities being re-scripted to accommodate displays of power, rhetorical spectacle, and political idealisation can be traced across city-wide massive and significant events.

City of Nuremberg, ZeppelinField-APlaceforLearning , Panorama picture of a march-past on the “Day of the Wehrmacht” during the 1938 Party Rally.

Photo : Documentation Centre Nazi Party Rally Grounds , 1938

A photograph showing a procession and flag ceremony at the Nuremberg Rally of 1934, the annual rally of the

Albert Speer, the chief architect commissioned to design the Zeppelin Field, wrote in his memoir: 16

“I struggled over those first sketches until, in an inspired moment, the idea came to me: a mighty flight of stairs topped and enclosed by a long colonnade, flanked on both ends by stone abutments… Hitler liked to say that the purpose of his building was to transmit his time and its spirit to posterity. Ultimately, all that remained to remind men of the great epochs of history was their monumental architecture…

The Nuremberg Rally was a definitive of an emblematic event. A figure of a leader treated like a saint, revered or seeking reverence through propaganda. Within the arena, armies of people were decorated and grouped into battalions, religiously stand in awe waiting for the dramatic speeches by their saint. Flags and banners were raised in striking manners, towering in symmetrical arrays that anchored the arena’s entire visual field. The infamous swastika logo appeared as a potent symbol of the party and its imperial ambition.

Lighting was carefully calibrated, especially since the most significant parades were held at night. Intriguingly, Speer noted in his memoir that he initially opted for night parades to conceal the poor marching abilities and even poorer physiques of thousands of party members but eventually realised the dramatic potential of powerful lighting. 17 What initially began as a means of masking evolved into an impactful framing strategy by design choices. The event became a ritual, replicated annually, possibly to maintain and reinforce the party’s position of power in the public perception.

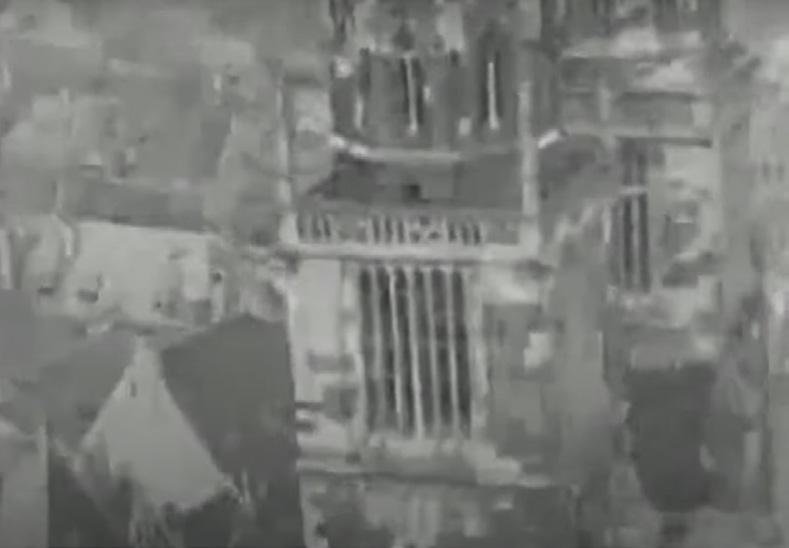

A similar rendition of propaganda could be found in Leni Riefenstahl’s film 18, the Triumph of the Will (1935) where the opening scene starts with an aerial footage of the city, captured from presumably a military plane. It started with the plane manoeuvring down, cutting through clouds and exposing the city below. The plane then seems to be flying at a relatively low altitude, passing through several buildings, and the scene shifts towards a series of frames that capture details of spires and tall monuments in the city. The scene then unfolded with the plane landing, cheerfully celebrated by a crowd of people, waving the infamous salute. A god-like figure then descended from the plane, smiled at his subject, or perhaps at his panoramic view.

He was then paraded through the city, in a similar fashion to how the various records illustrated the King would have embarked on the Port of Leith in 1822. This dramatic rendering brought upon the tension of situating the scenes in the city and propaganda ideals to be dispersed, permeated, and ingrained as the frame unfolds

This particular proto-cinematic apparatus contains a built-in viewing mechanism based on the stereoscopic principle, juxtaposing two images of the same subject taken from slightly different angles to produce an illusion of depth. 20 Through an ocular motion, one views these images sequentially, akin to a carousel. The set of seats surrounding the device allows multiple viewers to simultaneously embark on a visual tour, typically of cities or exotic places.

When associated with the discourse of power and authority, the panorama becomes a critical tool in framing perception. In the King’s visit, the Queen’s funeral procession, and the Nuremberg rallies, the city itself is staged as a kind of panorama, flipped through and toured as shifting scenes. Dorrian notes the historical emergence of the panoramic viewpoint as a representational form, referencing an essay that considers panorama as an authoritarian device:

”The panoramic visual field… is an important colonisers’ tool, first brought to perfection against [the Highland Scots] before being exported across the globe in the service of Hanoverian geopolitical ambition.”21

The King’s descent to Holyrood Palace, as recorded by Mudie, is described as the most picturesque and national of scenes—where he looks “with emotions which may well be conceived, upon the gilded spires of his ancestors.” 22

This architectonic use of the city, with its spires and towers, is mirrored in Triumph of the Will. Its opening scene renders the city’s vertical silhouettes as semiotic devices, acting as stage props in a cinematic play that romanticises the Führer. The constructed urban scenery becomes a surface across which frames play, leads the subject to be immersed in the scenic vista and authoritarian ideology. This rendition of architecture as a scenic-political instrument is further deepened in Michael Charlesworth’s description of the Hoober Stand—a structure designed for rulers to indulge in the panorama.23

Hoober Stand, let us remind ourselves, is a panoramic device that functions within, and as a product of, class relations. The middle-class artists climb a building erected by a rulingclass landowner who twice held supreme political power. At the top, they are provided with the surrogate eye of the rulers (the telescope) and indulge, for the space of an afternoon only, in the ‘view from the top’, which is usually the purview and property solely of the rulers.

10 —

Geograph.org.uk, Hoober Stand, Wentworth the most prominent landmark in the Dearne Valley. Photo : Christopher Thomas , 25 September 2005

Situating the city through tableaux vivants, or living pictures, the city can be framed as a series of momentary, temporal scenes. In the temporal event of 1822, the accounts recorded orchestration in multiple framings: the control of the route taken by the royal procession, the marshalling and costuming of the citizenry, and various temporary erections. These markers of points captured the event as being framed and staged accordingly through Scott’s detailed planning via his pseudonymised guidebook. 24 A similar pattern could be extrapolated through the Queen’s funeral procession, in which the Council provided certain guidelines on how the city and public should behave throughout the event. A mise-en-scène 25, a detailed orchestration and stage arrangement in the play.

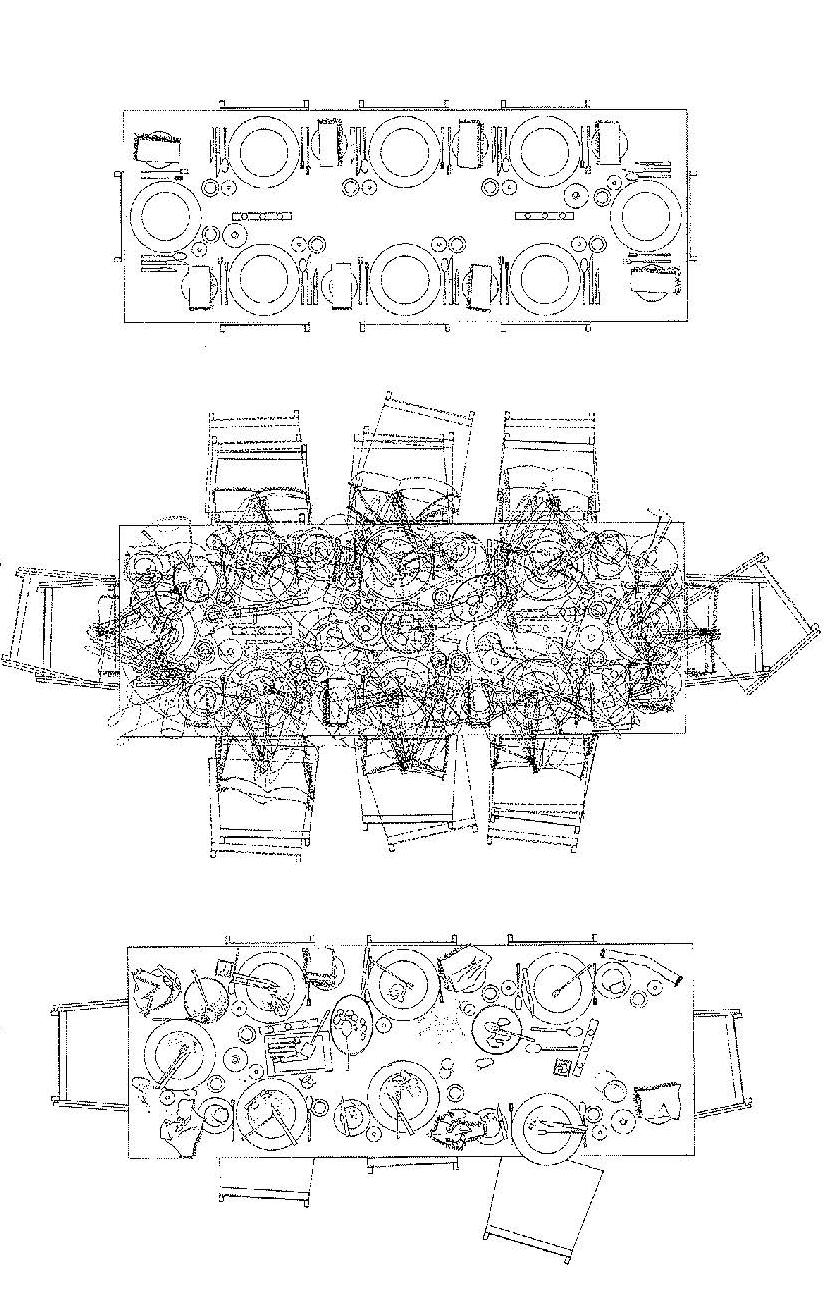

The Lay of the Table

An architectural ordering of place, status and function

A frozen moment of perfection

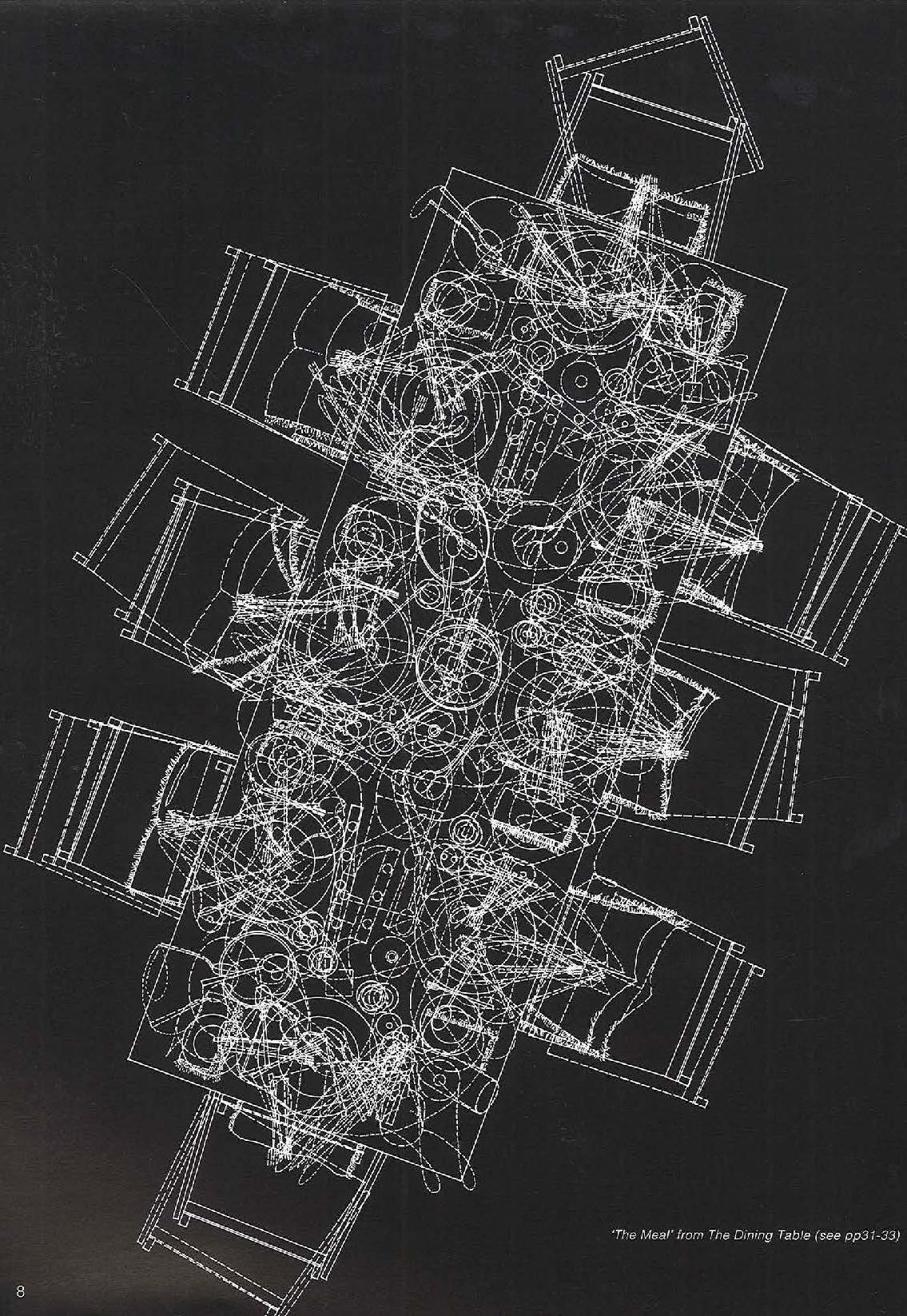

The Meal

Use begins to undermine the apparent stability of the (architectural) order Traces of occupation in time

The recognition of life’s disorder

The Trace

The dirty tablecloth witness of disorder Between space and time The Palimpest

Fig. 12 —

Sarah Wigglesworth and Jeremy Till, TheEverydayandArchitecture, The Dining Table Drawings p. 32

This drawing brings to my mind the momentary depiction in Sarah Wigglesworth and Jeremy Till’s drawing, The Dining Table. The table is seen as a temporal object,it is left undefined, without a purpose, to be defined by momentary acts. “At no time,” they write, “can the Dining Table be said exclusively to represent one side of life more than another.”29

Sarah Wigglesworth and Jeremy Till, TheEverydayand Architecture, The ‘Meal’ from The Dining Table p. 8 Fig. 13 —

It was in this instance, I found a similarly powerful tableux-like quality descriptions of a dining table as how Dorrian found the accounts for the King’s visit : -

“The Dining Table sits in the centre of our ‘parlour’. the front room of our terraced house. On it stands items of everyday domestic use such as salt cellar and pepper mill, vases of flowers, fruit bowl and candlesticks. On an average day it collects the detritus of domestic life : letters and mailshots, magazines, keys, bike lights and small change. At regular intervals it becomes the site for meals, gathering over time the marks of the food and drink spilled on its surface. At other times, it is the venue for office meetings, because our office is not large enough to accommodate more than four people. At such time it is be found scattered with pieces of paper, models, drawings, pens and other evidence of office life.... a surface that retains the patina of time—the traces of past events indelibly etched into the surface ” 30

Framing the moments of temporality became the fundamentals of how I pursue to document the frames upon frames upon frames that I encountered in the context our live-build project in the Architectural Design Studio, Radical Harvest; a method to unfolding temporality. As this essay unfolds onto the subsequent frame, or its subsequent frame that is unfolding... I would like the curtain to come down and change the scenery with a Benjaminian passage from Caution: Steps! from One-Way Street:

“Work on good prose has three steps: a musical stage when it is composed, an architectonic one when it is built, and a textile one when it is woven.” 31

Dorian quoted the anonymous accounts directly in his essay The King in The City as the textual passage itself give the impression of sequence of pictures being unfolded. The passage is directly sourced from the book, An Eyewitness of Most of the Scenes which were then Exhibited (1822).

Superimposing or juxtaposing my observation from the walk onto the actual textual passage construction of the tableuxlike sequence, taken from the Eyewitness book .

Dorrian , the King in the City in Writing on the Image, p.18“Association”

Dorrian , the King in the City in Writing on the Image, p.19“The Dynamic of Sympathy”

King Geoge IV visit to Edinburgh was from 15 to 29 August 1822, while Elizabeth II funeral procession in Edinburgh was from 11 September to 12 September 2022

Dorrian quoted in the King in the City, p.19, sourced from Simpson, Letters to Sir Walter Scott, p.24

Similar technique of superimposing my observation of the Queen’s funeral procession onto the textual construction sourced from Simpson’s Letter to Sir Walter Scott.

See HM : The Queen How to pay your respects, The City of Edinburgh Council website, https://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/ queen-elizabeth and Queen Elizabeth II: Coffin to travel by road from Balmoral to Edinburgh https://www.bbc.co.uk/ news/uk-scotland-62862148

Dorrian , the King in the City in Writing on the Image, p.13p.14 “Spectacle and Spectatorship”

First-hand personal experience shared by my seminar tutor, Ella who was there in the city during the funeral procession

The Vila Autodromo, a favela (informal housing typology in Rio De Janeiro) were as it deemed “unpleasant” also due to it’s proximity with Rio’s Olympic Park, further read : TheOlympic Juggernaut: Displacing The Poor From Atlanta To Rio by Bill Littlefield ; https://www.wbur.org/onlyagame/2016/08/05/ autodromo-rio-atlanta-olympics

Large scale restructing of Beijing for the Olympic in 2008, Looking back and ahead: Lessons from the 2008 Beijing OlympicGames a blog written by Hyun Bang Shin for London School of Economics and Political Science, August 2012, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/looking-back-2008beijing-olympic-games-shin/

Accounts by John Ruch, an Atlanta journalist on his remarks on the interview for Atlanta 1996, on the same blog article ; TheOlympicJuggernaut

Quotes from Hinton, Chris & Hite, John, Weimar & Nazi Germany. Hodder Education Publishers, 2000., as a secondary reference from NurembergRally,WorldHistoryEncyclopedia, https://web.archive.org/web/20250108223652/https://www. worldhistory.org/Nuremberg_Rally/

Memoirs of Alber Speer, Nazi’s architect sourced from Speer, Albert. InsidetheThirdReich. Simon & Schuster, 1997. p.97 as a secondary reference from ibid.

ibid.

Leni Riefenstahl was a prominent film director, producer, screenwriter and had produced several propaganda film for Nazi’s Germany; Triumph of the Will (1932) & Olympia (1938)

Greil Marcus, Preface section in Walter Benjamin’s One-Way Street (2016 edition)

Peselmann Veronica, Enacting public perception in the late 19thcentury:TheKaiserpanorama, 2016

Dorrian , the King in the City in WritingontheImage, p.18

Michael Charlesworth, ‘Thomas Sandby Climbs the Hoober Stand : The Politics of Panoramic Drawing in Eighteen Century Brintain’ where he described in detail about Hoober Stand being a panoramic tool

(Walter Scott) HintsAdressedtotheInhabitantsofEdinburgh and Others, in prospect of His Majesty’s Visit, by an Old Citizen (Edinburgh : Bell and Bradfute, etc. 1822)

Mise-en-scene : Translated from French, it means “setting the stage”

Alexander Nasmyth, Views of Edinburgh. Six Designs for Stage Sets for ‘The Heart of Midlothian’ artwork theatrical play based on the novel by Walter Scott under the same name, December 1819 - February 1820. Photo : National Galleries Scotland

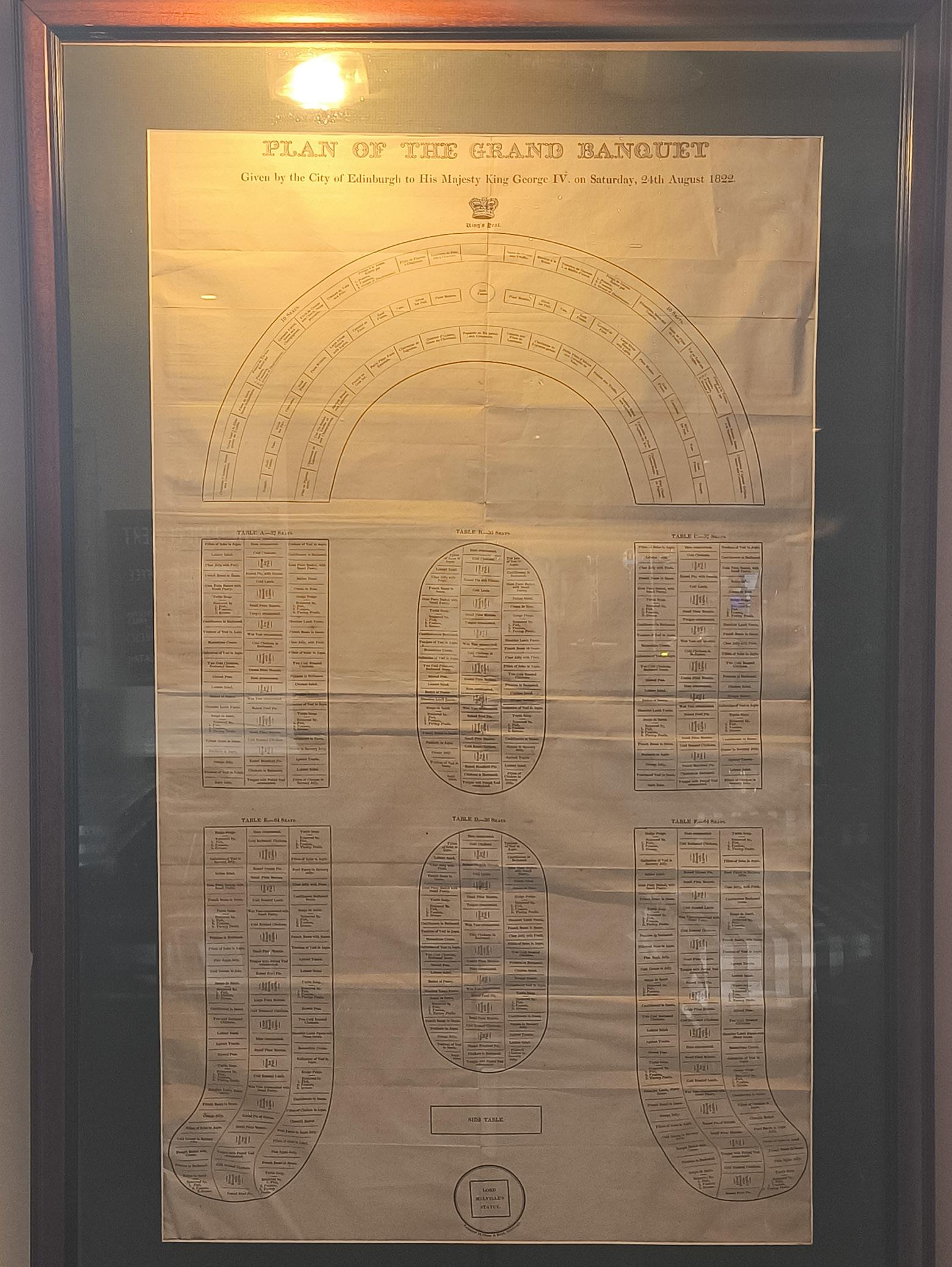

For a higher resolution scanned image of the drawing, see : PlanoftheGrandBanquet,University of St. Andrew, University Collection ID, : sDA817-V06M-8-4 ,https://collections.standrews.ac.uk/item/plan-of-the-grand-banquet/100461

What caught my attention here was the exotic dish of turtle soup, something I just only discovered existed. Once popular in the UK, its popularity declined with the dwindling turtle population, as it rightly should have.

Sarah Wigglesworth and Jeremy Till, The Everyday and Architecture, p.31

ibid.

Walter Benjamin, One-WayStreet (2016 edition), p. 41

Fig.1a&b—

Author, Photograph of the scenery as I walked down the street, pretending to be a king, intersection of Constitution Street, Leith Walk looking inwards, towards the city.

20 January 2025

Fig. 2 —

Fig. 3 —

BBC News, Queen Elizabeth II coffin leaves St. Giles Cathedral, 13 September 2022

Photo : PA Media.

BBC News, Edinburgh roads close as city prepares for Queen mourners Council workers setting up barriers on the Royal Mile, Photo : unknown, 10 September 2022

Fig. 6 —

Fig. 7 —

A photograph showing a procession and flag ceremony at the Nuremberg Rally of 1934, the annual rally of the Nazi party. (photo : Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-16196), published 01 Oct 2024 on worldhistory.org

A 1937 photograph showing the dramatic stage lighting used at the Nuremberg rallies in Nazi Germany. (photo : US National Archives), published 27 Sept 2024 on worldhistory.org

Fig. 8 —

Fig. 4 —

Fig. 5 —

Bill Littlefield, The Olympic Juggernaut: Displacing The Poor From Atlanta To Rio, Vila Autodromo, a favela in Rio de Janeiro, was razed in preparation for 2016 Summer Olympics. Photo : Mario Tama/Getty Image, August 2016

City of Nuremberg, Zeppelin Field - A Place for Learning , Panorama picture of a marchpast on the “Day of the Wehrmacht” during the 1938 Party Rally.

Photo : Documentation Centre Nazi Party Rally Grounds , 1938

Fig. 9 —

Snippets from introduction scene of Triumph of The Will (1935), produced by Leni Riefenstahl. Retrieved from Youtube Channel : Totalitarian Cinematography, uploaded 21 Feb 2023

Woodcut for Kaiserpanorama device advertisement, source : unknown, circa 1880. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (image on public domain)

Fig. 10 —

Geograph.org.uk, Hoober Stand, Wentworth the most prominent landmark in the Dearne Valley. Photo : Christopher Thomas , 25 September 2005

Dorrian, Mark.SomethingintheAir:OntheAtmosphereofaLeeMillerPhotograph in Drawing Matter Journal 3 - Storytelling (Drawingmatter.org. , 2025) p.1-18

Dorrian, Mark. Voice, Monstrosity and Flaying: Anish Kapoor’s Marsyas as a Silent Sound Work, in Architectural Theory Review 17, no. 1 (2012): p.94-102

Shapiro, David.TheClockofDeletion:TimeandJohnHedjuk’sArchitecture, in John Hedjuk’s The Collapse of Time and Other Diary Construction (London : Architectural Association,1987) np. Connor, Steve. The Book of Skin London : Reaktion, 2004, p. 37-38

Dorrian, Mark. Clouds of Architecture in Writing on the Image: Architecture, the City and the Politics of Representation (London: IB Tauris, 2015), pp. 107-118.

Dorrian, Mark. The King in the City: The Iconology of George IV in Edinburgh, 1822 in Writing on the Image: Architecture, the City and the Politics of Representation (London: IB Tauris, 2015), pp. 107-118.

Walter Benjamin. One-WayStreet(Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press 2016), preface, p. 41