8 minute read

Psychedelics: Voodoo Of Science?

Psychedelics: Voodoo or Science?

Warren Zhu

What images pop out when you hear LSD, DMT and Magic Mushrooms? Hippies running around naked with flowers around their neck? Or freshmen parties streaming with vomit and chants? Yes, yes, yes. The reckless use of psychedelic drugs is almost invariably tied to the Hippie movement starting from the 60s, and most have been criminalised since then. Most would silently walk away from the hippies chanting love and peace and sex; it all seems pretty voodoo and nonsensical. But what if I tell you that psychedelics have been shown to do the following: 1. Relieve death anxiety from cancer patients (80% of cancer patients demonstrated clinically significant reductions in anxiety) 2. Suppress depression 3. Alleviate alcohol/tobacco addiction (80% after 6 months, 67% after 1 year for tobacco) Improve OCD symptoms4. 5. Increase the personality trait of

Openness to Experience, which correlates with creativity and empathy

Why do these drugs under the ‘Psychedelics’ umbrella have such a huge effect? Is it just bad science or is there really something behind these infamous Hippie drugs?

First, let’s look at the chemical structure of psychedelics. The Chemical Structure

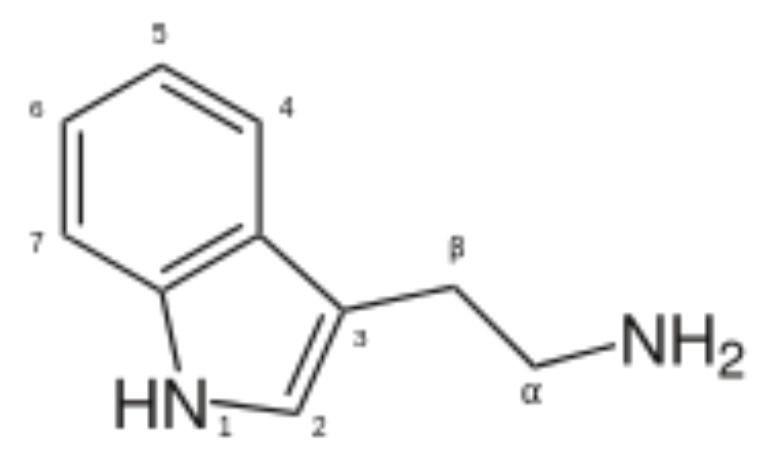

The organic compound tryptamine is common in all psychedelics (See Fig. 1). Tryptamine is one of the signalling molecules used between cells in plants, fungi, and animals. Fig. 1 Tryptamine (C 10 H 12 N 2 )

Perhaps the most famous of the tryptamines is the neurotransmitter serotonin. An elevated level of serotonin correlates to a decreased level of anxiety, an elevation in mood, and relief of distress. The tryptamine in the psychedelic compounds has a complementary shape with a serotonin receptor called 5-HT2A, meaning that it can bind to and activate the receptor, mimicking the effects of high levels of serotonin. What is more incredible is that LSD’s affinity to the serotonin receptor 5-HT2A is even better than serotonin itself! It is better than serotonin at fitting into a receptor designed for serotonin!

Effects on the Brain

Our brain is normally pretty rigid. There are a few neural pathways that we use often, and thousands that are barely activated. However, under the influence of psychedelics, one approaches a semi-dreamlike state, with thousands of novel brain pathways lighting up and uncommon connections forming. In technical jargon, there is an increase of ‘entropy’ in the brain, making it more disorderly and chaotic. This can yield a plethora of benefits, as it provides a whole host of new thoughts and ideas that normally would not be conjured by oneself. This can be a source of creativity and a way to increase one’s empathy towards others. The leading hypothesis is that these novel connections are being made because of the decreased activity of an area of the brain called the ‘default mode network’. This includes the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the hippocampus, the inferior parietal lobe, and the temporal lobe. The ‘default mode network’ is the part of the brain that causes you to think about all the preps that you haven’t done and all the lessons that you’re having but don’t want to have in the middle of an intensely boring lesson; it generates the constant chattering of the mind and is also turned off when skilled meditators are meditating. In this sense, the mind of a person on a psychedelic trip bears resemblance to a person in deep meditation. As the activity of the ‘default mode network’ decreases, the sense of the self as a separate entity from the world diminishes too. At this stage, there is a sort of ‘ego death’, in which one feels completely merged with the world. (Bear with me, I know this sounds pretty voodoo.) This may be the reason for the miraculous effect of psychedelics on relieving death anxiety, as death is the dissolution of the distinct boundaries between ‘them’ and ‘me’, in which one is returned to the world as a pile of organic matter, waiting to be decomposed and reused. I will elaborate further in the conclusion of the ‘entropic brain hypothesis’ which will help us to conceptualize why psychedelics have these effects.

Voodoo or Science?

It is clear that the use of psychedelics, especially under professional guidance and advice, can dramatically alter one’s perspective on life and improve one’s quality of living. However, more research is needed to determine how much of the observed effect comes from psychedelic rather than the placebo effect, and how much is really due to the compound itself. This is evident in how much a psychedelic experience relies on the purposeful creation of an environment that is conducive to its use, and how drastic a difference there is between recreational use of the drug and clinical use of the drug. The effects of psychedelics may partly be attributed to a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ in which one’s expectation for the drug’s effectiveness ultimately makes the drug effective. Some researchers have postulated that psychedelics are no more than an ‘active placebo’, meaning that psychedelics merely assist one in actualising one’s expectation of their effects instead of having any real effects themselves. This is further complicated by the fact that a double-blind controlled experiment is almost impossible to conduct with psychedelics simply because of the unique effects of the drug. Moreover, it has always been known that the placebo effect is the strongest in the newest drug due to the mysterious aura surrounding its existence. Considering the mystery surrounding psychedelics and the cultural taboo around psychedelic drugs, the placebo effect may be exaggerated further. As you can see, it is all a big hot mess. However, there is still great hope about the effectiveness of psychedelics. For example, one of the leading hypotheses is the ‘entropic brain hypothesis’ which states that because psychedelics increase the entropy (disorder) inside the brain, the brain’s normal way of functioning is disordered and one can jump out of the previous rigid way of thinking. Depression, under this hypothesis, is a mode of operation in which one has trapped oneself within a solely pessimistic view of the world, and addiction, too, is the brain craving for order and returning to its default way of operating.

Perhaps it is fair to say that psychedelics are voodoo and science - where the immeasurable spiritual and materialistic sciences coincide and synthesise. And, at the end of the day, why should we even care, so long as they help and save lives?

Bibliography

Barrett, Frederick S., Hollis Robbins, David Smooke, Jenine L. Brown, and Roland R. Griffiths. “Qualitative and Quantitative Features of Music Reported to Support Peak Mystical Experiences During Psychedelic Therapy Sessions.” Frontiers in Physiology 8 (July 2017): 1–12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01238.

Bogenschutz, Michael P., Alyssa A. Forcehimes, Jessica A. Pommy, Claire E. Wilcox, P. C. R. Barbosa, and Rick J. Strassman. “Psilocybin-Assisted Treatment for Alcohol Dependence: A Proof-of-Concept Study.” Journal of Psychopharmacology 29, no. 3 (2015): 289–99. doi:10.1177/0269881114565144.

Brewer, Judson. The Craving Mind: From Cigarettes to Smartphones to Love—Why We Get Hooked and How We Can Break Bad Habits. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2017.

Buckner, Randy L., Jessica R. AndrewsHanna, and Daniel L. Schacter. “The Brain’s Default Network: Anatomy, Function, and Relevance to Disease.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1124, no. 1 (2008): 1–38. doi:10.1196/annals.1440.011.

Carbonaro, Theresa M., Matthew P. Bradstreet, Frederick S. Barrett, Katherine A. MacLean, Robert Jesse, Matthew W. Johnson, and Roland R. Griffiths. “Survey Study of Challenging Experiences After Ingesting Psilocybin Mushrooms: Acute and Enduring Positive and Negative Consequences.” Journal of Psychopharmacology 30, no. 12 (2016): 1268–78.

Carhart-Harris, Robin L., et al. “Neural Correlates of the Psychedelic State as Determined by fMRI Studies with Psilocybin.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, no. 6 (2012): 2138–43. doi:10.1073/ pnas.1119598109.

“Psilocybin with Psychological Support for Treatment-Resistant Depression: An Open- Label Feasibility Study.” Lancet Psychiatry 3, no. 7 (2016): 619–27. doi:10.1016/S2215- 0366(16)30065-7.

Carhart-Harris, Robin L., Mendel Kaelen, and David J. Nutt. “How Do Hallucinogens Work on the Brain?” Psychologist 27, no. 9 (2014): 662–65. Carhart-Harris, Robin L., Robert Leech, Peter J. Hellyer, Murray Shanahan, Amanda Feilding, Enzo Tagliazucchi, Dante R. Chialvo, and David Nutt. “The Entropic Brain: A Theory of Conscious States Informed by Neuroimaging Research with Psychedelic Drugs.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8 (Feb. 2014): 20. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00020.

Fadiman, James. The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide: Safe, Therapeutic and Sacred Journeys.Rochester, Vt.: Park Street Press, 2011.

Grob, Charles S., Anthony P. Bossis, and Roland R. Griffiths. “Use of the Classic Hallucinogen Psilocybin for Treatment of Existential Distress Associated with Cancer.” In Psychological Aspects of Cancer: A Guide to Emotional and Psychological Consequences of Cancer, Their Causes and Their Management,

Grob, Charles S., Alicia L. Danforth, Gurpreet S. Chopra, Marycie Hagerty, Charles R. McKay, Adam L. Halberstadt, and George R. Greer. “Pilot Study of Psilocybin Treatment for Anxiety in Patients with Advanced-Stage Cancer.” Archives of General Psychiatry 68, no. 1 (2011): 71–8. doi:10.1001/ archgenpsychiatry.2010.116.

Killingsworth, Matthew A., and Daniel T. Gilbert. “A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind.” Science 330, no. 6006 (2010): 932. doi:10.1126/ science.1192439.

Moreno, Francisco A., Christopher B. Wiegand, E. Keolani Taitano, and Pedro L. Delgado. “Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Psilocybin in 9 Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67, no. 11 (2006): 1735–40. doi:10.4088/JCP. v67n1110.

Nour, Matthew M., Lisa Evans, and Robin L. Carhar-Harris. “Psychedelics, Personality and Political Perspectives.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs (2017): 1–10.

Pahnke, Walter, “The Psychedelic Mystical Experience in the Human Encounter with Death. Harvard Theological Review 62, no. 1 (1969): 1–22.

POLLAN, M. (2019). HOW TO CHANGE YOUR MIND: The new science of psychedelics.