10 minute read

Will Building A Dyson Sphere Solve The Earth’s Energy Problems?

Earth has an energy problem. But for most of human history, energy consumption was modest [1]. People relied on caloric energy from the food they consumed or on animal power to perform daily tasks. Burning biomass such as wood was the biggest source of energy. Then came the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s and the rise of the new Holy Trinity of energy: coal, natural gas, and petroleum, all of which are non-renewable fossil fuels.

Our current annual global energy consumption is estimated to be 580 million terajoules –– roughly equivalent to the energy we would use if all 7.5 billion of us boiled 70 kettles of water per hour every day for a year [2, 3]. 80% of this energy comes from fossil fuels, a leading source of global warming pollution, damaging the planet at almost every stage [4]. The extraction of fossil fuels, done mostly through mining or drilling, damages land, threatens the health and safety of miners and causes water and air pollution. The refining and purifying of fuels into a usable state leaves excess waste material disposed of in ways detrimental to the health of the environment and the community. The transportation of fossil fuels over long distances also generates its own pollution and may result in disastrous accidents such as oil spills and gas leaks. And the burning of fossil fuels releases soot, the health consequences of which include chronic bronchitis and aggravated asthma, as well as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide, leading to acid rain. Most significantly, it releases carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that traps heat in the atmosphere and causes global warming. The hotter, drier climate has driven both the Australian bushfires and California wildfires –– we are literally setting the planet on fire.

But the solution to Earth’s energy problem might not come from the Earth itself. At any moment, the sun emits about 3.86 x 1026 watts of energy - 7 x 1017 times more energy than we need [5]. We’re just not harnessing it. Yet.

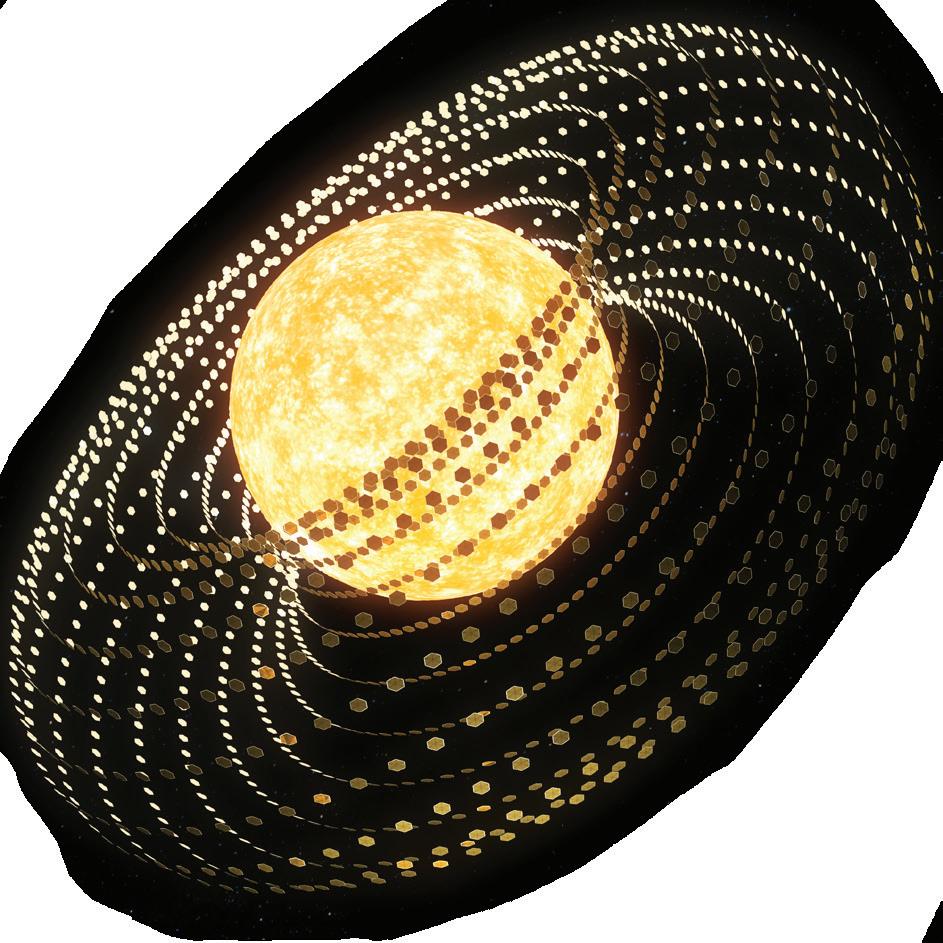

In 1960, British-American theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson first speculated about Dyson spheres, hypothetical megastructures that encircle a star to capture a large percentage of its power output [6]. A Dyson sphere would not be a literal solid sphere enclosing the sun, as the immense tensile strength needed is physically impossible to achieve with our current technologies. A structure like that would also be liable to drift and crash into the sun [7]. Instead, if we were to build a Dyson sphere, we would most likely use a Dyson swarm model, which is a collection of solar panels situated in orbit around the sun (See Fig. 1) [7, 8].

Fig 1. Dyson swarm 3D model

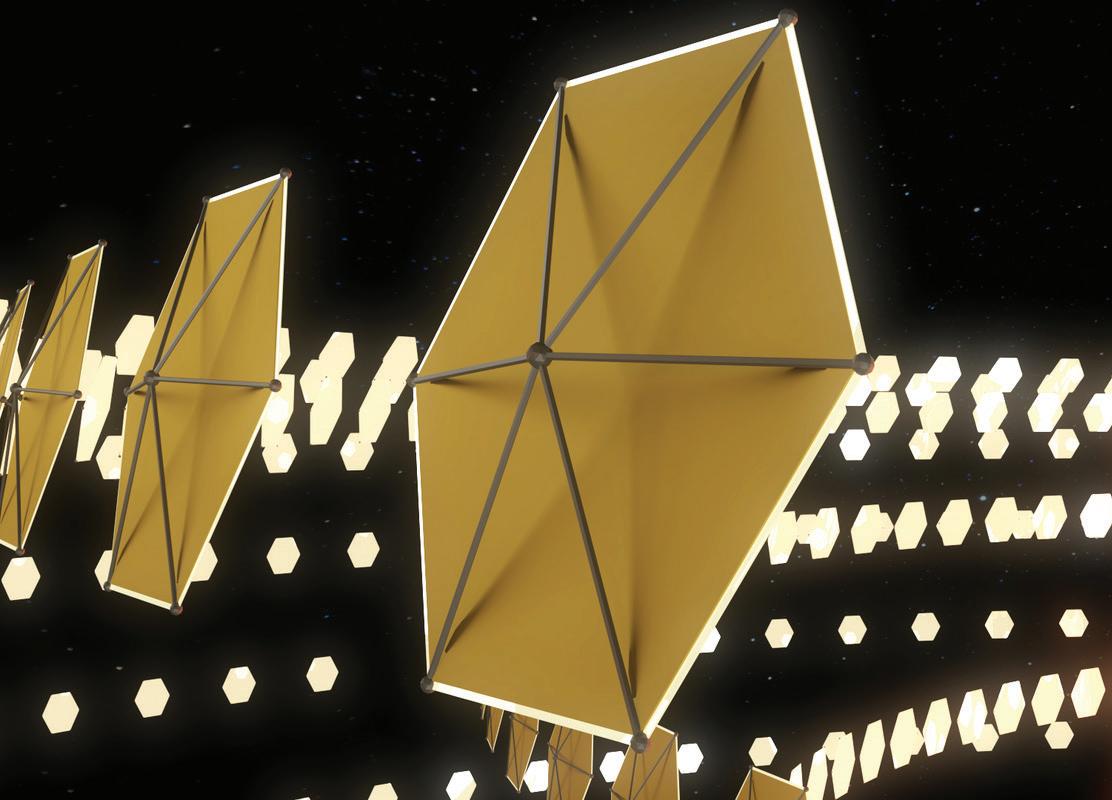

These solar panels would be very large lightweight mirrors, concentrating solar radiation down on focal points (heat engines combined with solar cells) where it would be transformed into useful work and beamed across space for use elsewhere [8]. They would need to operate without repairs for long periods of time and be cheap to produce, most likely made of polished metal foil bound to some supports (See Fig. 2) [9].

Fig. 2 Solar panel 3 D model

The sun is massive, so in order to surround it with solar panels, we would need to disassemble an entire planet. The easiest victim would be Mercury –– it’s the closest to the sun, has no atmosphere, only has about a third of the surface gravity of Earth, and is composed of 30% silicate and 70% metal, mainly iron or iron oxides, materials that will be used for the swarm [8, 9].

The initial energy generating source will be a 1 km2 array of solar panels, constructed on Mercury itself and then launched into space [8]. These will provide the energy to run miners which strip mine the planet’s surface and refiners, extracting valuable elements and fabricating them into swarm panels [9]. This forms a feedback loop, where the material removed will be made into solar captors that generate energy, allowing more material to be removed. 1/10ths of all the energy will be used to propel material into space. We can take advantage of Mercury’s low gravity to use mass-drivers such as railguns to launch the panels at high speeds into space –– much more efficient than using rockets. The entire process would be carried out by an army of automated robots overseen by a small group of human controllers [8, 9].

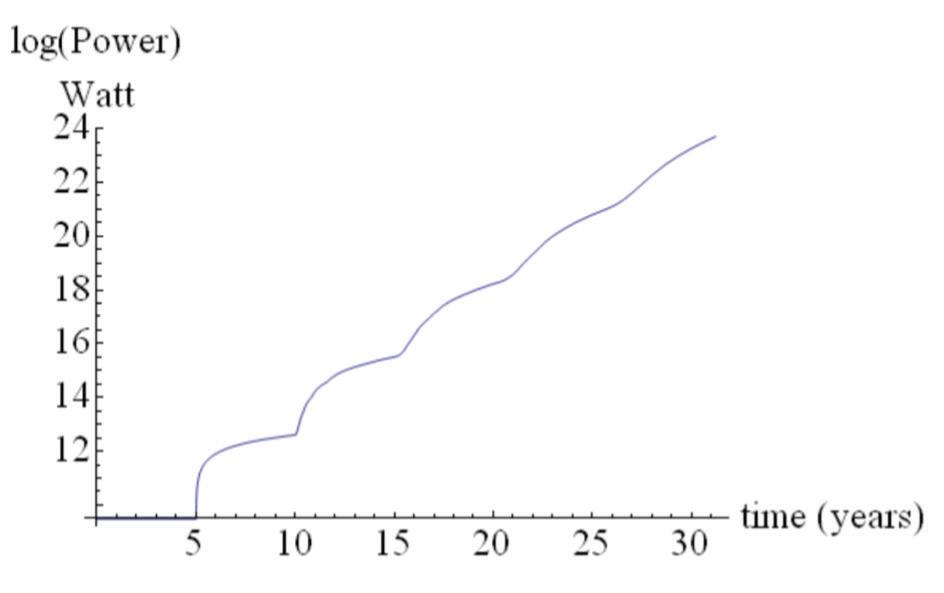

Assuming the overall efficiency of the solar captors is 1/3, that it takes five years to process the material into solar captors and place them in the correct orbit, and that half of the planet’s material will be suitable to construct solar captors, Mercury itself will be completely disassembled in 31 years and 85 days, thanks to exponential growth. The power available

increases initially in five-year cycles, which gradually smooth out to become linear on the log scale (See Fig. 3) [8].

Fig 3. Power available during the disassembly of Mercury

Image by Stuart Armstrong and Anders Sandberg

http://aleph.se/papers/ Spamming%20the%20universe.pdf

Harnessing even a tiny fraction of the sun’s energy using the Dyson sphere would give us the energy for projects such as terraforming planets, forming space colonies, or building other megastructures such a stellar engine to move our star, and thus the solar system, through the galaxy.

So if building a Dyson sphere can solve our energy problem and offer almost unlimited energy from our current energy consumption standpoint, why haven’t we done it yet? Well, because it’s impossible. For now, at least.

The Dyson sphere was originally conceptualised as a way for an intelligent alien civilisation to satisfy their energy needs after having gained the ability to use and store all of the energy available on its planet, meaning the aliens are already a Type 1 civilisation on the Kardashev scale. The Kardashev scale is a method of measuring technological advancement based on the amount of energy a civilisation can use [10]. A Dyson sphere is an indicator of a transition to a Type 2 civilisation, which can use and control energy at the scale of its planetary system, and an eventual evolution to a Type 3 civilisation, which can control energy at the scale of its entire host galaxy [10]. We haven’t even reached the threshold to become a Type 1 civilisation yet, so trying to build a megastructure around the sun is probably not a good idea.

Building a Dyson sphere would be the largest, most ambitious project undertaken by humanity and would require global cooperation on a level we just haven’t reached yet. We also don’t yet have the technology to achieve some of the more ambitious steps necessary.

The plan involves mining Mercury until the planet is entirely disassembled. The deepest mine on Earth, the Mponeng Gold Mine, has a depth of 4 km below the surface [11]. The radius of Mercury is 2,439.7 km [12]. Additionally, Mercury is supposed to be mined mostly by robots, which we don’t even have in mines on Earth yet [11]. There’s also the issue of Mercury’s unusable mass, which becomes debris [11]. Transmitting power back to Earth poses another problem. Wireless transmission of electricity is possible, but not exactly easy. Microwaves can transmit electricity, though the furthest distance scientists have been able to do so is 148 km, with most of the energy being lost [11]. Lasers are another possibility yet similarly have limited distance. Unfortunately, we currently are not able to transmit any of all that glorious solar energy across the 102.1 million km between Mercury and Earth [13].

We have far from exhausted the solutions to our energy problem right here on Earth. In 2019, only around 11% of global primary energy came from renewable technologies, 7% being hydropower, one of our oldest and largest sources of low-carbon energy [14]. The World Wildlife Federation’s 2011 Energy Report states ‘it is technically possible to achieve almost 100% renewable energy sources within the next four decades’, with the major sources being wind, solar, biomass and hydropower. It estimated that a million onshore and 100,000 offshore wind turbines could meet a quarter of the world’s energy demand by 2050 [15].

When energy consumption is narrowed down to just electricity, which is easier to decarbonize as it is less reliant on oil and gas, around a quarter of energy comes from renewables [14]. These numbers can still be increased. Although there is concern that the deployment of renewables will result in higher electricity prices, research has shown this doesn’t have to be the case. Energy storage is swiftly evolving and growing cheaper, meaning an energy grid run entirely on renewable energy up to 95% of the time is an increasingly realistic idea [16].

If renewables alone cannot save the planet, we can look to nuclear energy, which still poses a risk of radioactive contamination and dangerous nuclear waste, but has a small land footprint and low CO2 emissions, allowing it to eventually replace fossil fuels at a low cost [17]. While uranium, the fuel most widely used for nuclear fission, is not technically renewable, existing uranium from U-mine sites and existing spent fuel in fast reactors provide sufficient uranium fuel to produce 10 trillion kWh/year for thousands of years, making it a sustainable energy source [18]. Uranium extracted from seawater is replenished continuously, so if seawater extraction production costs fall and the source of uranium changes from mined ore to seawater, nuclear energy would also become a renewable energy source [18].

Will building a Dyson sphere solve Earth’s energy problem? No. But innovation in order to improve renewable energy technology, a push to increase sustainable energy consumption, and a transition to a green economy will. Once we’ve done all that, building a Dyson sphere may no longer be an impossible concept, but rather the logical next step to open up limitless possibilities.

PHYSICS AND TECHNOLOGY 31

Bibliography https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=pP44EPBMb8A&t=472s [1] “Earliest Energy.” Earliest Energy | EME 803: Applied Energy Policy, Penn State College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, [10] Knapp, Adam. “Kardashev scale.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, October 18, 2020, https://www.e-education.psu.edu/ eme803/node/502#:~:text=Prior%20 https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Kardashev_scale to%20that%2C%20early%20 people,an%20important%20source%20 of%20heat. [11] “A Few More Notes On The Impracticality Of Building A Dyson Sphere.” Forbes, Forbes Media, LLC, [2] “Terajoules of Energy Used.” The April 18, 2012, World Counts, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ https://www.theworldcounts.com/ challenges/climate-change/energy/ global-energy-consumption/story alexknapp/2012/04/04/afew-more-notes-on-theimpracticality-of-building-a-dysonsphere/#5b1be47f31ae [3] Gray, Richard. “The biggest energy challenges facing humanity.” BBC Future, BBC, 13th March 2017, [12] Williams, David R. “Mercury Fact Sheet.” NASA, 27 September 2018, https://www.bbc.com/future/ article/20170313-the-biggest-energyhttps://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/ factsheet/mercuryfact.html challenges-facing-humanity [13] “How far is Mercury from Earth? [4] “The Hidden Costs of Fossil Accurate distance data.” The Sky Live, Fuels.” Union of Concerned Scientists, Jul 15, 2008, https://theskylive.com/how-far-ismercury https://www.ucsusa.org/ resources/hidden-costs-fossilfuels#:~:text=Burning%20fossil%20 fuels%20emits%20a,the%20 [14] Ritchie, Hannah and Roser, Max. “Renewable Energy.” Our World in Data, 2017, environment%20and%20public%20 health.&text=Acid%20rain%20is%20 formed%20when,precipitation%20 that%20is%20mildly%20acidic https://ourworldindata.org/ renewable-energy [5] “The Sun’s Energy.” The University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, [15] “Is It Possible for the World to Run on Renewable Energy?” Knowledge@Wharton, Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Apr 23, 2015, https://ag.tennessee.edu/solar/Pages/ What%20Is%20Solar%20Energy/ Sun%27s%20Energy.aspx https://knowledge.wharton.upenn. edu/article/can-the-world-run-onrenewable-energy/[6] Mann, Adam. “What Is a Dyson Sphere?” Space.com, August 01, 2019, [16] “GE’s North American Studies Show No Hard Limit to Renewables https://www.space.com/dyson-sphere. html on a Grid System.” GE News, May 23, 2016,

[7] Dvorsky, George. “How to build a Dyson sphere in five (relatively) easy steps.” Sentient Developments, March 20, 2012, https://www.ge.com/news/pressreleases/ges-north-american-studiesshow-no-hard-limit-renewables-gridsystem

http://www.sentientdevelopments. com/2012/03/how-to-build-dysonsphere-in-five.html [8] Sandberg, Anders and Armstrong, Stuart. “Eternity in six hours: intergalactic spreading of intelligent life and sharpening the Fermi paradox” Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford University Philosophy Department, 2012,

http://aleph.se/papers/Spamming%20 the%20universe.pdf [9] Kurzgesagt - In A Nutshell. “How to Build a Dyson Sphere - The Ultimate Megastructure.” YouTube, 20 Dec 2018, [17] “3 Reasons Why Nuclear is Clean and Sustainable.” Office of Nuclear Energy, United States Department of Energy, April 30, 2020, https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/3reasons-why-nuclear-clean-andsustainable

[18] Conca, James. “Is Nuclear Power A Renewable Or A Sustainable Energy Source?” Forbes, Forbes Media, LLC, Mar 24, 2016,