FRANK HASKELL, AN AIDE ON THE STAFF OF GENERAL JOHN GIBBON, WAS POSITIONED ON THE THIRD OF JULY AT PERHAPS THE MOST SALIENT POINT ON CEMETERY RIDGE AT GETTYSBURG. DAYS LATER, IN WHAT BRUCE CATTON WOULD RECALL AS "ONE OF THE GENUINE CLASSICS OF CIVIL WAR LITERATURE," HASKELL WOULD PEN ONE OF THE MOST POIGNANT MEMOIRS OF THE DRAMATIC EVENTS OF THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG.

14

"I would not have missed this for anything"

By Arthur FremantleAN ACCOUNT OF THE JULY 3RD ASSAULT ON CEMETERY RIDE BY A BRITISH OBSERVER WHO WITNESSED THE AFTERMATH OF THE BATTLE.

LOCATED ON THE NORTHERN BANK OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER, TWO HOTELS, TWO LITTLE STORES, A SHOEMAKER'S SHOP AND POST OFFICE CONSTITUTED THE TOWN OF PERRYVILLE, MARYLAND. WITH THE OUTBREAK OF THE CIVIL WAR, THE TOWN TURNED INTO A MAJOR SUPPLY DEPOT AND MULE SCHOOL FOR THE FEDERAL ARMY. A REPORTER FROM THECECILWHIGVISITED THE BUSTLING DEPOT IN THE FALL OF 1861 AND WROTE A DESCRIPTIVE ACCOUNT.

IN HIS RECOLLECTIONS OF A PRIVATE , WARREN LEE GOSS PROVIDES A UNIQUE PERSPECTIVE, TAKING US ON A JOURNEY FROM THE LIFE OF A LAW STUDENT TO THAT OF A PRIVATE. HIS ENGAGING AND HUMOROUS ACCOUNT OF THE EARLY DAYS OF 1861 IS A TESTAMENT TO HIS STORYTELLING PROWESS. THIS ACCOUNT, WHICH ALSO APPEARED IN SERIAL FORM IN BATTLES AND LEADERS OF THE CIVIL WAR , OFFERS A GLIMPSE INTO THE WIT AND CHARM THAT GOSS BROUGHT TO HIS WRITINGS. 4

from the editor

Jeffrey R. Biggs

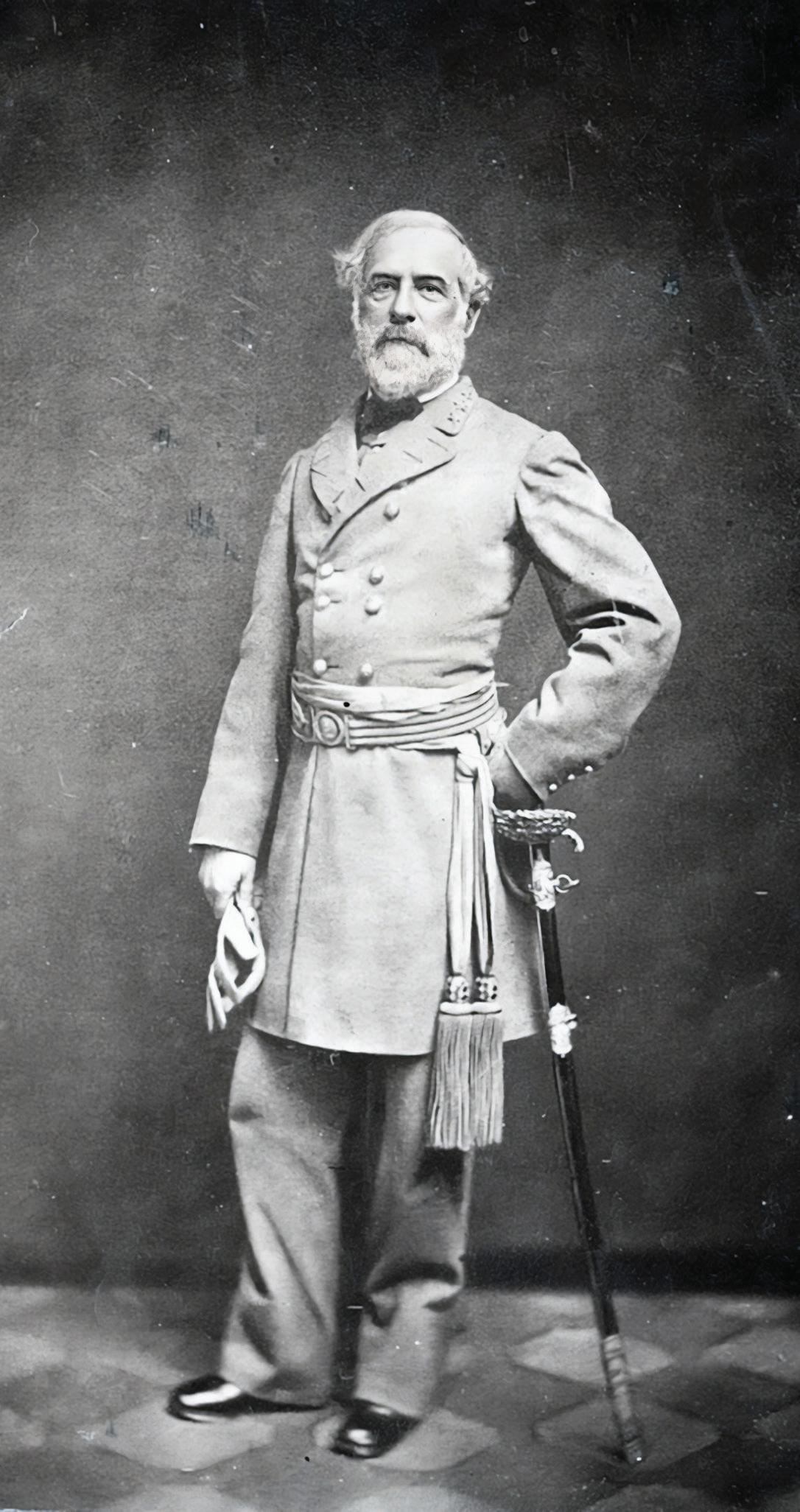

"It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it." - Robert E. Lee

During a recent bout of channel surfing, I chanced upon the BBC's comprehensive coverage of King Charles's notable attendance at the London annual Trooping the Colour celebration. This significant event, held every June 15 and known as the King's Birthday Parade, is steeped in history. More than 1,400 officers and enlisted men, accompanied by 200 horses and over 400 musicians, participated in this grand affair. These troops, fully trained and operational British soldiers, were adorned in the traditional ceremonial uniform of red tunics and bearskin caps. The King himself took the time to inspect and assess the Irish Guards. This martial spectacle, a part of the British monarchy's rich historical tapestry, might be unfamiliar to many Americans who, in our colonial past at least, have historically been unacquainted with such elaborate displays of military power.

I found the pageantry and precision, the orderliness and discipline, remarkable and beautiful, much like what Robert E. Lee saw when watching the precision and purpose behind the tragic and futile attack on Marye's Heights on December 13, 1862. As he was watching the Union's repeated attacks, he reportedly remarked that, "it is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it."

As a counterweight to our British cousin's display of military pride and tradition, our cable news outlets have filled in recent days with the horrid images of the ongoing struggles in Ukraine and the Middle East, where we see little of the pageantry of linear lines of troops marching in precise form, a traditional form of warfare, but only randomness and the horror of innocents being caught up in the conflict, a more modern and chaotic form of warfare.

Readers of Hardtack Illustrated and all of us who obsessively recall our own American Civil War should be reminded of Lee's warning from more than a century and half ago. As we delve into the details of the American Civil War, study its campaigns, and analyze troop movements, it's important to acknowledge the high cost of the conflict, nearly 700,000 killed, and reflect on the benefits it brought: the end of codified slavery on this continent. For me personally, who has been asked little to sacrifice for our freedom's sake, it's something I needed to be reminded of.

•

IWhat Lee was getting at was that - despite the pageantry and the appearance of good order - the reality is that all war is a bloody business and not to be treated lightly. Many of history's top military thinkers, from Sun-Tzu, William Techumsa Sherman to Colin Powell, feel that war should be a last resort after all other alternatives have been exhausted.

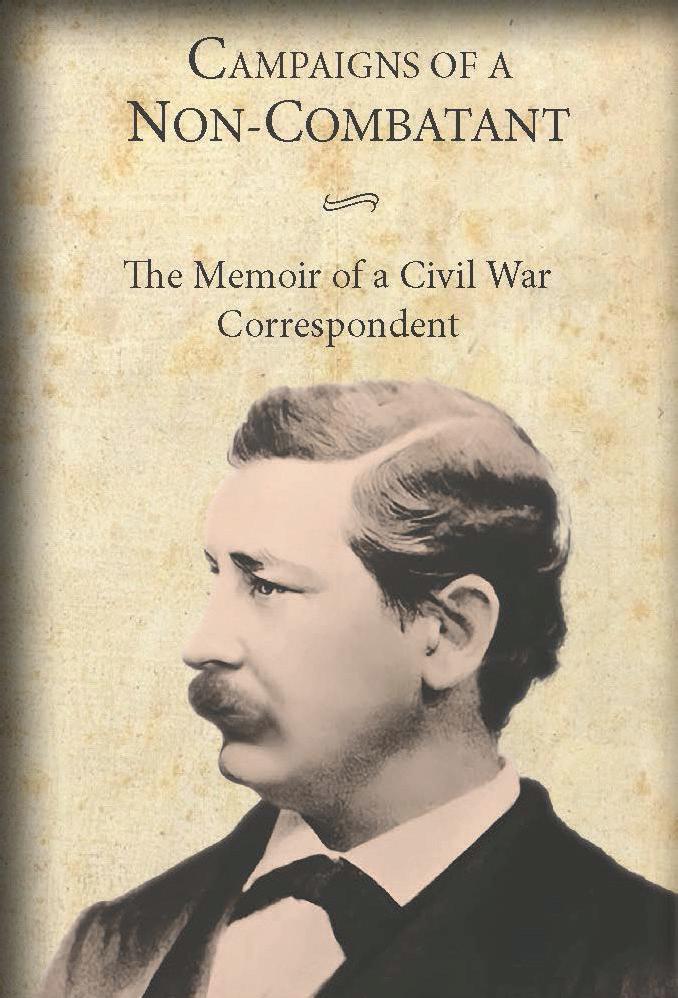

t's our third issue of Hardtack Illustrated , and we are encouraged by the number of views the electronic magazine is receiving. Since our spring 2024 release of George Alfred Townsend's memoir CampaignsofaNon-Combatant:TheMemoirofaCivilWarCorrespondent , the book is now available in many outlets, including Amazon, B&N, and Bookshop.org.

As we approach the anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg and the reopening of the iconic Little Round Top after a year-long rehabilitation, we felt it was only right to honor

this momentous occasion by sharing some authentic voices of those who witnessed it. In "I Would Have not Missed this for Anything," we include Sir Arthur James Lyon Fremantle's vivid description of Pickett's Charge and the atmosphere on the Rebel side of Cemetery Ridge following the repulse. Fremantle, positioned in the most suitable place to observe General Robert E. Lee's composure, provides a unique and personal perspective that brings the events of the battle to life.

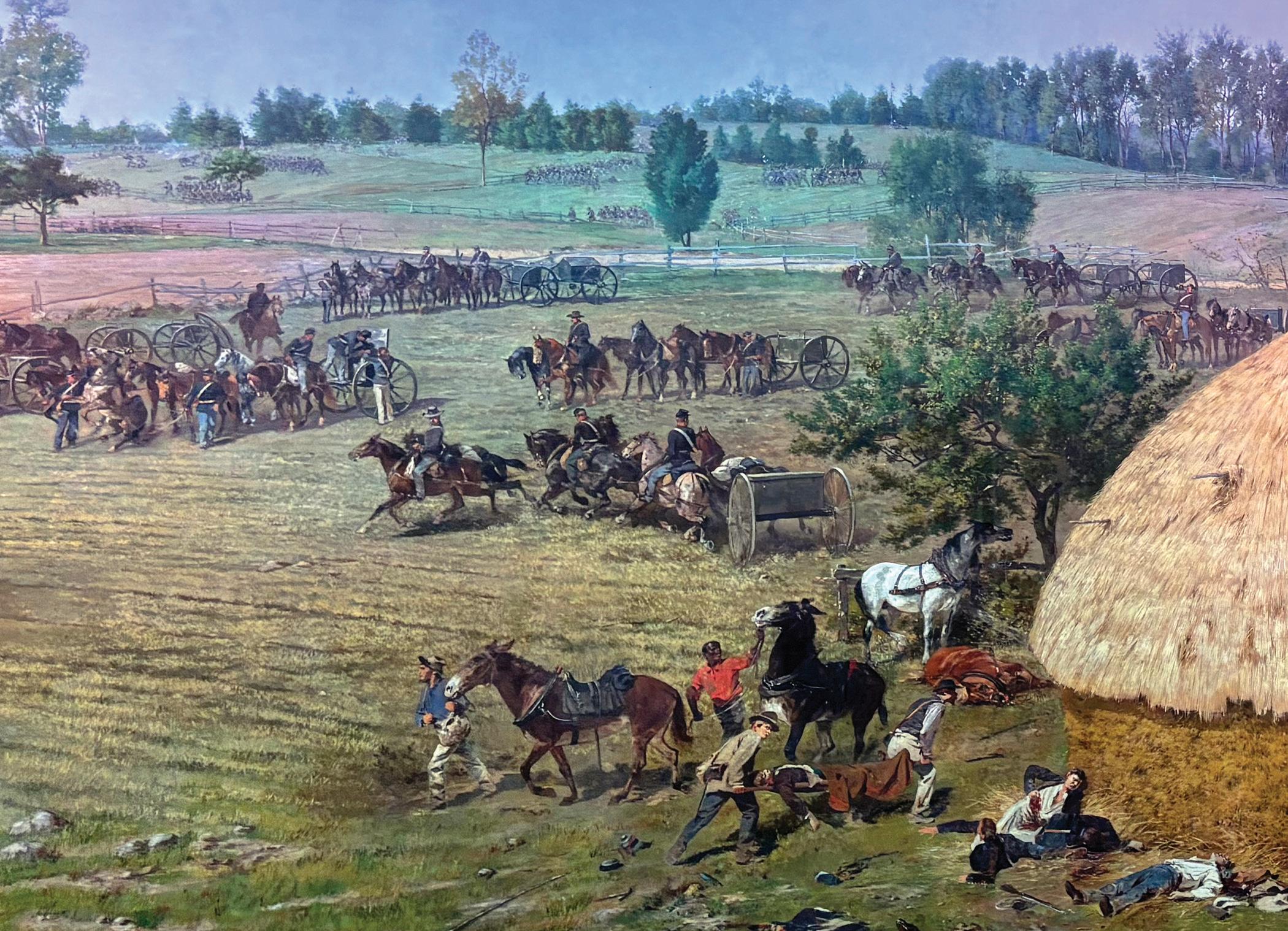

In another memoir, just as relevant but from the Union side of the ridge, is the Vermont native Frank Haskell's excerpt, which we entitle "An Awful Universe of Battle." In this account, Haskell provides a detailed, minute-by-minute narrative of the crucial moments when, for a few minutes, it seemed the tide of battle would favor the Rebels once more. This narrative, as Bruce Catton recognized, is "one of the genuine classics of Civil War Literature." It's a significant piece that deepens our understanding of the battle. We have supplemented Haskell's excerpt with recent images I took of the Paul Philippoteaux's cyclorama painting which is on display at the Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center.

Living near Perryville, Maryland, and frequently passing by the sign on I-95, we find the report carried in the CecilWhig , a proUnion organ out of Cecil County in north-eastern Maryland, of the brief bustling atmosphere around Perryville in the first year of the war to be eye-opening. The Mule School there furnished thousands of unfortunate beasts for the heavy loads supplying the eastern war effort. As a sidebar, we delve into some intriguing little-known facts about the Stump Mansion, a historical gem that was repurposed as a headquarters. It's still there and available for tours.

In "Going to the Front: Recollections of a Private," we carry an account from Warren Lee Goss, a native of Massachusetts, who following the war, gained some notoriety as a children's novelist and a whistle-blower on the treatment of Union prisoners of war. He was also an avid storyteller and shared his early days after enlistment. This edition includes an account, which also appeared in serial form in BattlesandLeadersoftheCivilWar , that offers a glimpse into the wit and charm that Goss brought to his writings.

I would like to extend to readers the opportunity to contact me in case you come across Civil War era material which you think would be great to include in future editions, or if you can think of ways to improve. I can be reached at jeffreybiggs@verizon.net.

all things civil war.

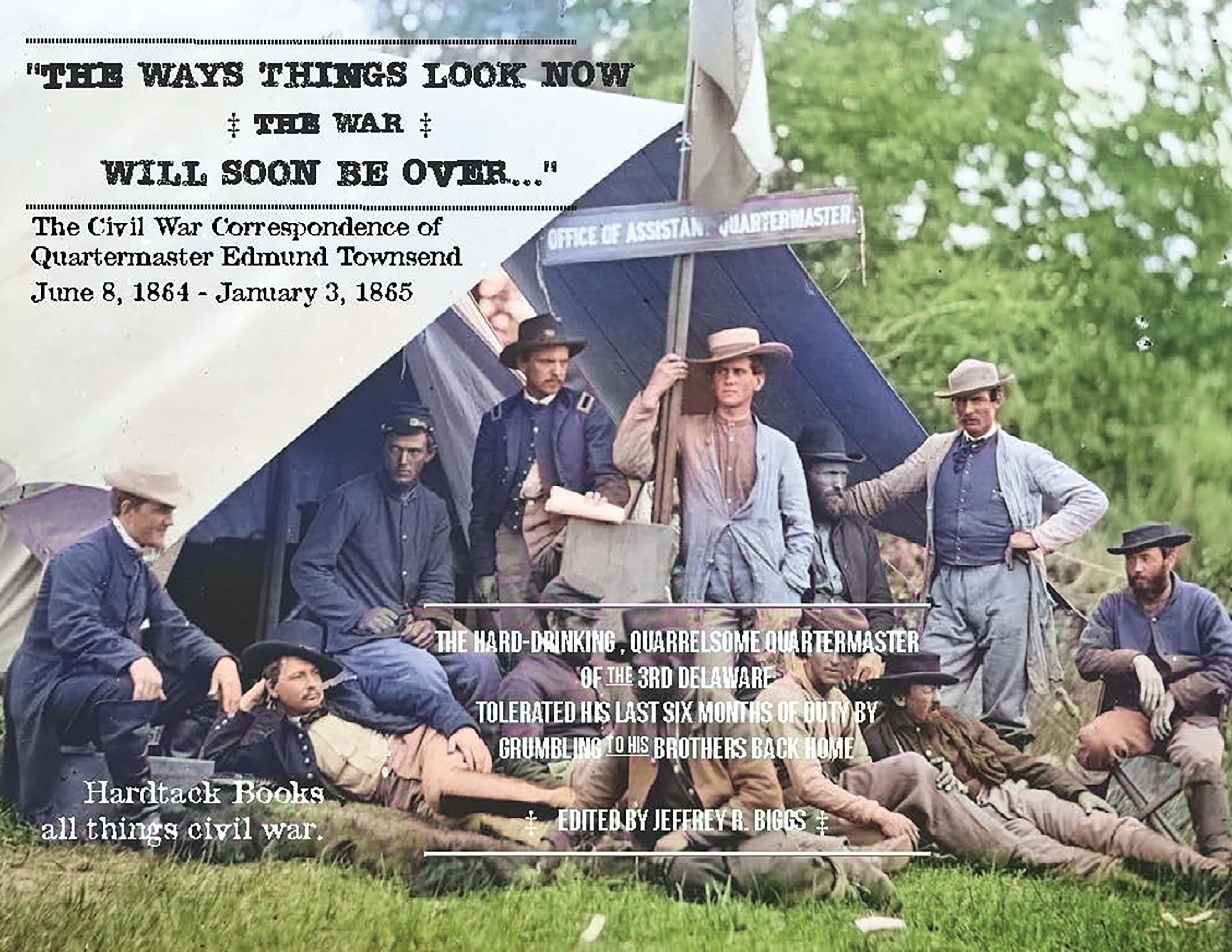

During the summer and fall of 1864, Lieutenant Edmund Townsend, the regimental quartermaster of the 3rd Delaware, penned a series of letters to his brothers, Samuel and John Townsend, during the siege of Petersburg. His letters serve as a fascinating insight into the mind of an independent and somewhat cynical minded staff officer who had his share of scrapes with the army command. Lt. Townsend, considered middle-aged at the age of forty-five, rails in his letters about army politics and martinet generals. When not pining for his discharge, Townsend describes his experiences as a witness to the trenchlike fighting along the Petersburg line, the City Point explosion and the 1864 presidential election. The following selections of letters date from Cold Harbor on June 8, 1864 until Townsend's discharge in January 1865.

Go to our website www.hardtackbooks.com for this additional content

Located on the northern bank of the Susquehanna River, two hotels, two little stores, a shoemaker's shop and post office constituted the town of Perryville, Maryland. With the outbreak of the Civil War, the town turned into a major depot and mule school for the Federal army. A reporter from TheCecilWhig visited the bustling depot in the fall of 1861 and wrote the following account.

WE STEPPED OUT of the Philadelphia train in company with some friends on Thursday morning and spent a few hours strolling about the various encampments of men, horses, and mules.

The first object we came upon, worthy of note, was the horse camp – we suppose it must be termed, that word being a la mode in these military times. We were very politely shown through the horse department by Mr. Arad Alexander of Northfield, Mass., who is chief manager of all the horses – having an amount of 2,000 at present in his charge, a large number having been, the present week, drawn from the Perryville depot, for the use of cavalry and artillery companies of Harford and Cecil, which have been fitted out for active service.

The horses are very neatly and com-

It's estimated that by the end of 1862, 11,000 mules and 3,500 horses passed through the supply depot established at Perry Point, MD.

fortably housed in long sheds, open at the sides, with boxes and troughs for feeding: by this economical arrangement, saving much provender, which, when fed loosely on the ground, as is the case in the green mule department, is unavoidably wasted. Mr. Alexander has his horses very methodically arranged, animals of the same color are placed together, classifying them according to color. A squad of men is appointed to take charge of the animals of a certain color, and by this judicious arrangement, when one gets loose, his locality is at once known, and the keepers cannot evade the responsibility of neglect of duty. The

Charles Sawtelle, an 1854 West Point graduate, organized the supply depot at Perryville under General McClellan's direction. He later took an active role in the Peninsular Campaign, disembarking and transporting troops and supplies to the Army of the Potomac.

horses are in fine keeping and are mostly beautiful animals. To people fond of viewing fine horses, a peep at those under Mr. Alexander’s charge at Perryville will richly repay the trouble. The cost of head was $120.00.

Quitting the horse camp, we next proceeded to the large mule pen below Mr. Stump’s mansion, where some 4,000 green mules were penned. These animals are fed by tumbling bales of hay and straw about on the ground inside their enclosure and emptying grain out in the same manner. Large quantities, of course, are wasted by the slovenly mode

The Stump mansion, pictured here in the 1890's, was requisitioned by the federal army, sharing it for a time with the Stump family.

of feeding. A bunch of mules collect around the bales of hay, and a general exchange of kicks is kept up by the pugnacious animals during the meal; the “bullies” being in possession of the heap, the weaker cattle, to a greater or lesser extent, are compelled to play the “grab game,” and snatch a bite between kicks. The animals, however, were in good flesh and looked remarkably well. There are about 9,000 mules, broken and unbroken, in the various camps. About 1,400 Regulars are encamped on this part of the Stump farm, who, at the time of our visit, were drilling in squads.

mense heaps, will be worth many more thousands of dollars to him.

Barracks are being erected for the better accommodation of the soldiers. These wooden quarters will greatly add to their comfort, and the constant coughing with proceeded from the ranks was sufficient indication that further protection from the inclemency of the season was much needed. Mr. A. J. Scott, of Elkton, is chief “boss” in the carpenter’s department, and a very arduous duty he must perform, but he seems fully competent at the task.

The next – and perhaps not the least

9,000

This farm is about one of the best locations for the use the Government has appropriated it to, of any that could be selected in the country. Mr. Stump receives $4,000 a year, we are informed, as rent from the Government and the manure, which is piled up already in im-

pleasant – feature our visit to drop into the mess room of the principle clerks and employees of Captain Sawtelle, who have resolved themselves into a club numbering 14 members – Captain Sawtelle has his headquarters at Mr. Stump’s Mansion – where we where hospitably

dined on Government fare, which we are free to confess is good and as bountiful as any hungry man could wish to enjoy. The Government ration is much more than they can consume, and the members of the club informed us that they had quite a surplus to dispose of, which formed a kind of, etc. fund.

From the dining room of the club, we were next conducted by Mr. Townsend, chief Commissary of the station, to the storehouse, which is one of the old depot buildings, where we were shown the life-imparting qualities of the army, and without which but a few short hours were required to annihilate the most valiant army that was ever collected in battle array. Here, barrels of flour, barrels of coffee, barrels of molasses, barrels of sugar, barrels of rice, and hard biscuits, boxes of bacon, and quarters of fat beef were heaped and piled all around.

When Mr. Townsend first took possession of the post, he ordered 80 pounds of beef per week; now, 4,000 pounds are required to provision, for the same length of time, fresh meat, the employees of the Government at this post. The bread heretofore has been baked in Havre-de-Grace, but a new oven has just been finished, capable of supplying the post with fresh bread. A new commissary building, 80 feet by 48, is being erected to supply the present wretched storehouse. From the neat and methodical arrangement which have been effected by Mr. Townsend in his present inadequate and inconvenient quarters, it is evident that the Government has a most efficient officer in the commissary department at Perryville, and the new and commodious building that is being erected, for the Commissary’s use will much convenience and assist in facilitating operations in this department.

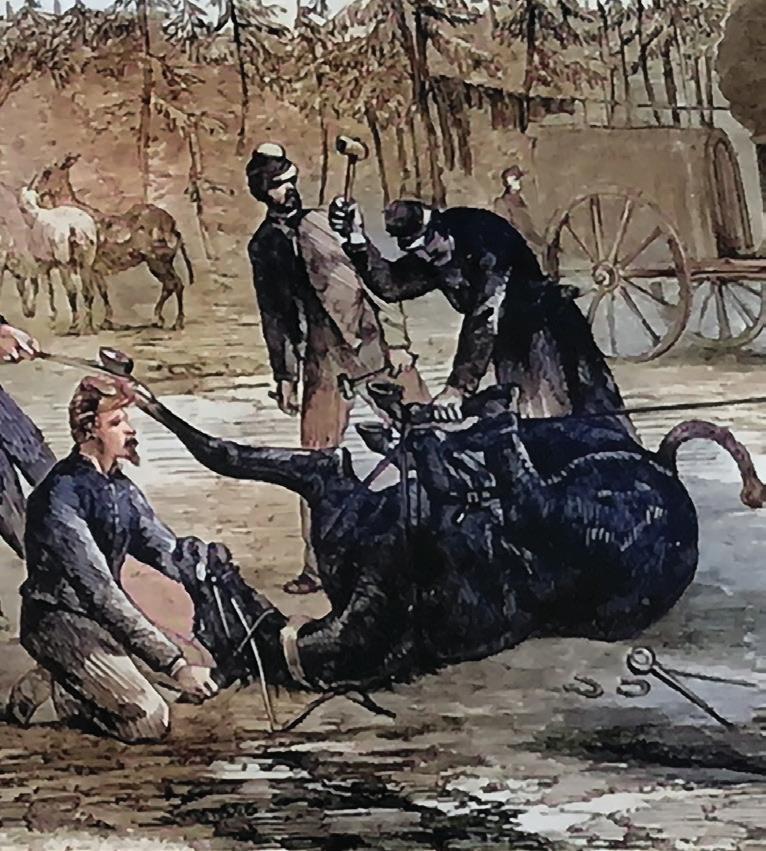

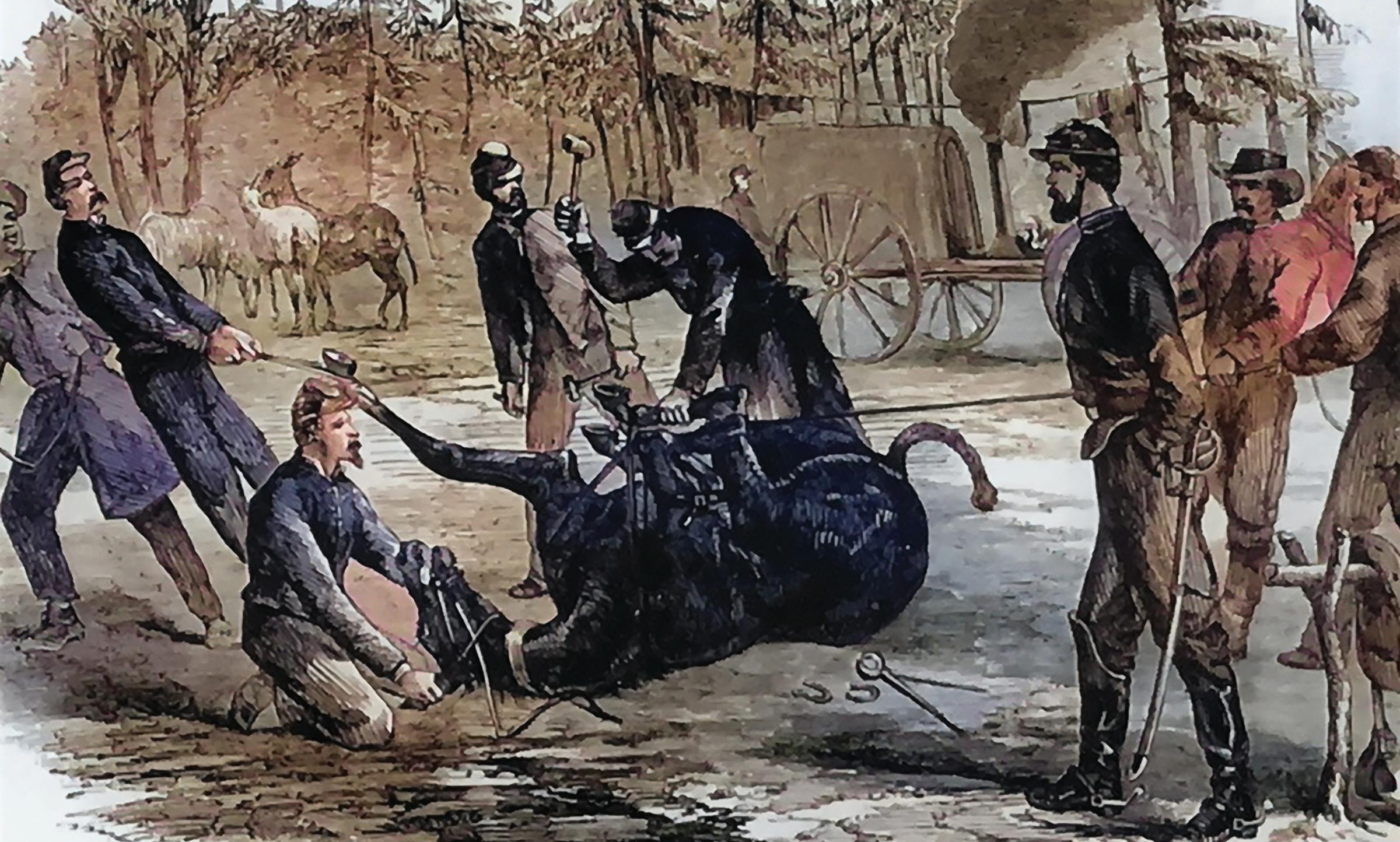

We next bent our steps to the mule breaking quarter. This we found to consist of a muddy pen, containing at the time we looked in, a little mule with a bridle on – a kind of “decoy” to another wild individual of the long-eared family, and three or four stalwart darkies with poles, wading through the mud and lashing the frightened animal into a corner where the “decoy” stood ready to dart into a narrow stall when the negroes closed in upon them with their long poles. The mule was at length driven in a rope passed round his middle like a girth, and another rope fastened to the animal’s forefoot and slipped through the girth rope. The mule being thus tied up, with the addition of another rope fastened about his head, the side of the stall was opened, and the animal jerked into another pen covered with tan and held down by “n*****” power; he was soon harnessed and forced outside, where a wagon awaited his muleship, he was hitched in along with some quiet, broken animals, and started. During this operation, there often occurs some grand and lofty tumbling, but being plenty of force, the mules are generally managed readily. It is generally believed that the mules are managed by the Rarey system, but there is nothing of the Rarey management whatever. Rarey’s science consists of persuasive and gentle treatment, while the Perryville system is one of force and compulsion altogether. It is impossible to give the reader a fair conception of the enormous amount of hay and straw that is piled round about the place. Perhaps if we say there are mountains of this kind of provender, it was the best figure to convey the idea we can make use of; while out on the wharves are piled bags of grain, and boats unloading more, and far out on the river and bay steamers may be seen towing barges piled up with bales, to keep up the supply which is daily consumed by so many thousand pairs of jaws. At 3 o’clock p.m. the steam whistle blew, and stepping into the cars we took leave of Perryville and the sights and sounds of that military depot on instruction to man and animal.

The VA Maryland Health Care System operates a museum on the former grounds of the Stump Mansion. The old Stump grist mill located on the campus of the Perry Point VA Medical Center is open seasonably from March to November on Thursday and the 1st and 3rd Saturday of each month. The mansion is an easy walk from the museum and worth a visit.

FOR DIRECTIONS: Take I-95 to exit 93 for Route 222 east toward Perryville. At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Route 222 and proceed for about two miles to the end of the road and turn left onto Broad Street. Continue for half a mile and turn right onto Ikea Way. In a quarter mile, turn right onto Marion Tapp Parkway. Follow the road until you come to the gated entrance of the medical center. After passing the medical center’s entrance gate, continue onto 5th Street. After a quarter mile the road splits and you will bear left to continue on 5th Street to Avenue D. Turn left onto Avenue D, then turn right onto 6th Street. Follow Sixth Street to the end and turn left onto Avenue A. The museum will be on your right shortly after turning onto Avenue A. The Stump Mansion 500 feet north along Avenue A.

CREDITS: All photographs courtesy of Library of Congress unless otherwise noted. Mule: Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper , March 14, 1863; Stump Mansion (post-war): Perry Point VA Medical Center; CecilWhig , 11/30/61

Built around 1750 from bricks brought from England to be used as ballasts on ships, the mansion was purchased in 1800 by John Stump. The property included a mansion, a grist mill, and an estate of nearly 1,800 acres. The view here shows the "drive front," where carriages would approach by the driveway; the other front faces the garden with a view of the Chesapeake Bay. The mansion and its grounds served as the social center of the Chesapeake area in Maryland, it is rumored that guests included

"Soon after the Civil War erupted in April 1861, Perryville became an important Union staging area. Adjacent to Fort Dare here, a riverside plantation was confiscated from Confederate sympathizers and immediately transformed into a special camp and school. The 'recruits' marched down Broad Street but were forbidden from mingling with thee curious citizenry, excluded from mess tents, and issued no uniforms, weapons or tents. They were mules, and they outnumbered men at the camp.

About 11,000 mules, 3,500 horses, 3,000 wagons, and 3,200 teamsters converged on Perryville for military training. The mules arrived unbroken and tended to stampede. They presented great challenges to those hired to train them and protested getting the U.S. brands on their shoulders. But by the time they left for war, they were harnessed four to a wagon in teams, obeyed commands, and hauled highly valuable military supplies. The mule's service was critically important to the Federal logistics and supply system, and the training academy at Perry Point took credit for the good behavior of the beasts. During the war, about 1.5 million horses and mules were wounded or killed."

George Washington and General Lafayette, who is said to have planted one of the estate's beech trees.

John Stump died in 1828, willing the estate to his son John Stump II. In the 1850s, the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad owners negotiated a rightof-way through the estate, which greatly added to the property's value. Recognizing its strategic value at the mouth of the navigable Susquehanna River, in 1861 the federal government took possession of the mansion and its grounds, using it as a supply depot and training station for army mules. The family was a slave-holding family with eight enslaved persons based on the 1860 slave schedule; the Stump's, for a few months, shared the mansion, but eventually, the closeness with the burgeoning federal presence proved too much, and the family relocated to nearby Harford County. The enslaved persons stayed behind and worked in the training of the mules as hired workers for the army.

When the depot was abandoned by the army, the Stump family returned and found the grounds to be badly used and neglected. John Stump II died in 1898 leaving the estate to his ten surviving children.

This market established by Civil War Trails recalls The Perryville Mule School. The marker is located inside Perryville Community Park. The marker is on Marion Tapp Parkway, on the left when traveling south next to the post office.

We have collected links to Civil War-era newspapers from the Library of Congress Chronicling America series and Google Newspapers. A few others are accessible in various state archives, but all of these links are free, with no subscription required. We will keep adding as we come along others, but this is the place to start.

Our list of primary resources for Civil War research scratches the surface of what’s available. The list directs users to only free sites such as the Haithi Trust and Archive.org. We will keep adding to this list, but it will never be complete.

Government Congressional records, the OR's and Report on the JC on the Conduct of the War can be found here.

GHARDTACK BOOKS ALL THINGS CIVIL WAR.

eorge Alfred Townsend was a special war correspondent for the PhiladelphiaPress and NewYorkHeraldduring the Civil War. He followed McClellan’s Army of the Potomac and Pope’s Army of Virginia in the spring and summer of 1862, ling dozens of dispatches to his editors. Finally, a er su ering from the e ects of ‘swamp fever,’ he took a two-year break in Europe, where he lectured about his experiences. Townsend returned to the war front in 1865 and -a er taking the pen name of “GATH” - was the rst correspondent to describe the war’s climax at Five Forks. He released his memoir in 1866, detailing his personal experiences and recollections of the Civil War and those dramatic days.

Campaigns of a Non-Combatant: The Memoir of a Civil War Correspondent

ISBN 13: 978-0986361531

by: George Alfred Townsend

Release: 1st QTR 2024 | Price $17.99 |Pages: 269

Design & Editor: Jeffrey R. Biggs

INQUIRIES: Jeffrey Biggs, jeffreybiggs@verizon.net

AVAILABLE AT: Amazon.com | Ingram | Bookshop.com

is Hardtack Books reissue of Campaignsofa Non-Combatantis not a facsimile of the original work. Instead, it reimagines Townsend’s work in a modern font with dozens of illustrations and editorial footnotes.

About Hardtack Books: Hardtack Books specializes in republishing timeless Civil War narratives. Our goal is to make these captivating stories more accessible and appealing to today’s history enthusiasts at a moderate cost. By using modern styles in typography, graphics, and design, we bring to the twenty- rst century these rsthand accounts that shed light on both wartime experiences and the lives of those on the home front during the critical years of the Civil War.

At Hardtack Books, we are dedicated to preserving the rst-hand accounts of enlisted men, newspaper correspondents, and war leaders. Our mission is to bring these original sources, including memoirs, correspondence, and newspaper articles, together in contemporary publications.

"I WOULD HAVE NOT MISSED THIS FOR ANYTHING"

BY ARTHUR JAMES

BY ARTHUR JAMES

LYON FREMANTLE IN AN EXCERPT FROM THREE MONTHS IN THE SOUTHERN STATES.

BY

WHO WITNESSED THE AFTERMATH OF THE BATTLE

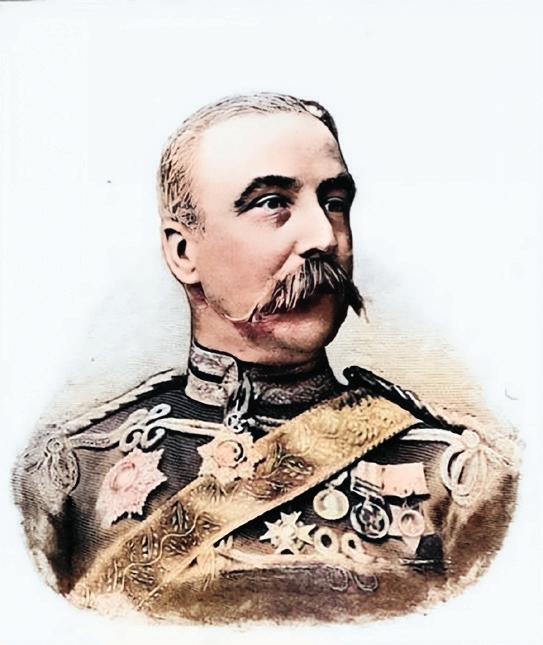

Arthur Fremantle, a British officer of the Coldstream Guards, spent three months in America during the Civil War traveling with the Union and Confederate armies. His memoir published as Three MonthsintheSouthernStatesgives readers an unvarnished view of the war from a foreigner's perspective

At 6 A. M.I rode to the field with Colonel Manning, and went over that portion of the ground which, after a fierce contest, had been won from the enemy yesterday evening. The dead were being buried, but great numbers were still lying about; also many mortally wounded, for whom nothing could be done. Amongst the latter were a number of Yankees dressed in bad imitations of the Zouave costume. They opened their glazed eyes as I rode past in a painfully imploring manner.

We joined Generals Lee and Longstreet's staff - they were reconnoitering and making preparations for renewing the attack. As we formed a pretty large party, we often drew upon ourselves the attention of the hostile sharpshooters and were two or three times favored with a shell. One of these shells set a brick building on fire, which was situated between the lines. This building was filled wounded, principally Yankees, who, I am afraid, must have perished miserably in the flames. Colonel Sorrell had been slightly wounded yesterday, but still

did duty. Major Walton's horse was killed, but there were no other casualties amongst my particular friends.

The plan of yesterday's attack seems to have been very simple: first, a heavy cannonade all along the line, followed by an advance of Longstreet's two divisions and part of Hill's corps. In consequence of the enemy's having been driven back some distance, Longstreet's corps (part of it) was in a much more forward situation than yesterday. But the range of heights to be gained was still most formidable, and evidently strongly intrenched.

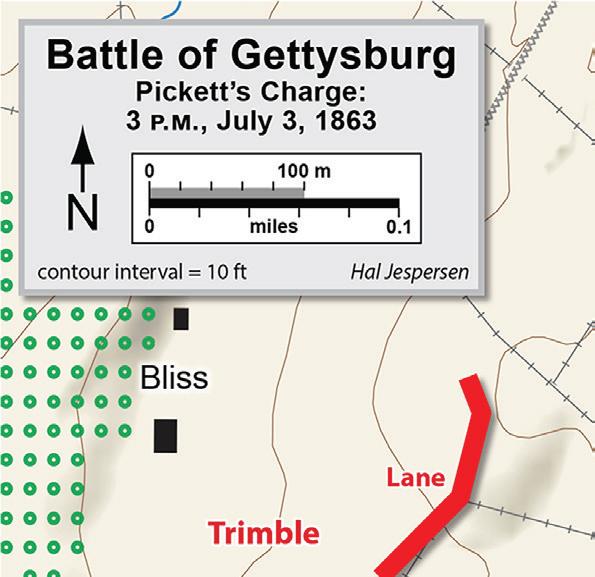

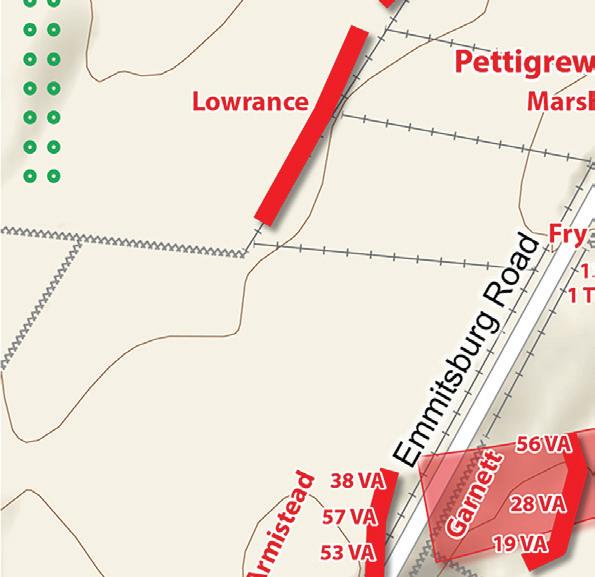

The distance between the Confederate guns and the Yankee position- i. e., between the woods crowning the opposite ridges - was at least a mile - quite open, gently undulating, and exposed to artillery the whole distance. This was the ground which had to be crossed in today's attack. Pickett's division, which has just come up, was to bear the brunt in Longstreet's attack, together with Heth and Pettigrew in Hill's corps. Pickett's division was a weak one (under 5,000), owing to the absence of two brigades.

At noon all Longstreet's dispositions were made; his troops for attack were deployed into line, and lying down in the woods; his batteries were ready to open. The general then dismounted and went to sleep for a short time. The Austrian officer and I now rode off to get, if possible, into some commanding position from whence we could see the whole thing without being exposed to the tremendous fire which was about to commence. After riding about for half an hour without being able to discover so desirable a situation, we determined to make for the cupola near Gettysburg, Ewell's headquarters. Just before we reached the entrance of the town, the cannonade opened with a fury which surpassed even that of yesterday.

Soon after passing through the toll-gate at the entrance of Gettysburg, we found that we had got into a heavy cross-fire; shells both from Federal and Confederate passing over our heads with great frequency. At length two shrapnel shells burst quite close to us, and a ball from one of them hit the officer who was

Based on a painting by Thure de Thulstrup, it shows Major General Winfield S. Hancock riding along the Union Lines during the Confederate bombardment - which Fremantle barely avoided - prior to Pickett's Charge of July 3, 1863.

conducting us. We then turned round and changed our views with regard to the cupola - the fire of one side being bad, enough, but preferable to that of both sides. A small boy of twelve years was riding with us at the time: this urchin took a diabolical interest in the bursting of the shells, and screamed with delight when he saw them take effect. I never saw this boy again, or found out who he was.

The road at Gettysburg was lined with Yankee dead, and as they had been killed on the 1st, the poor fellows had already begun to be very offensive. We then returned to the hill I was on yesterday. But finding that to see the actual fighting, it was absolutely necessary to go into the thick of the thing. I determined to make my way to General Longstreet. It was then about 2.30. After passing General Lee and his staff, I rode on through the woods in the direction in which I had left Longstreet. I soon began to meet many wounded men returning from the front; many of them asked in piteous tones the way to a doctor or an ambulance. The further I got, greater became the number of the wounded. At last I came to a perfect stream of them flocking through the woods in numbers as great as the crowd in Oxford Street in

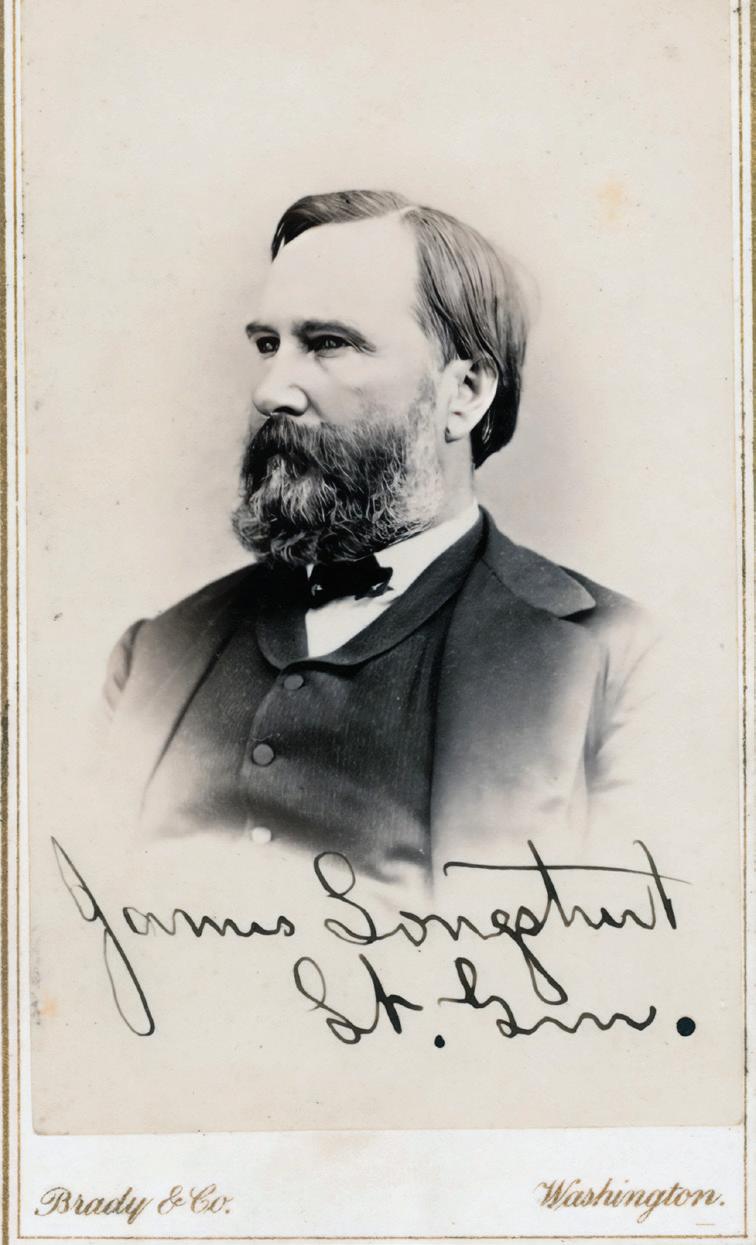

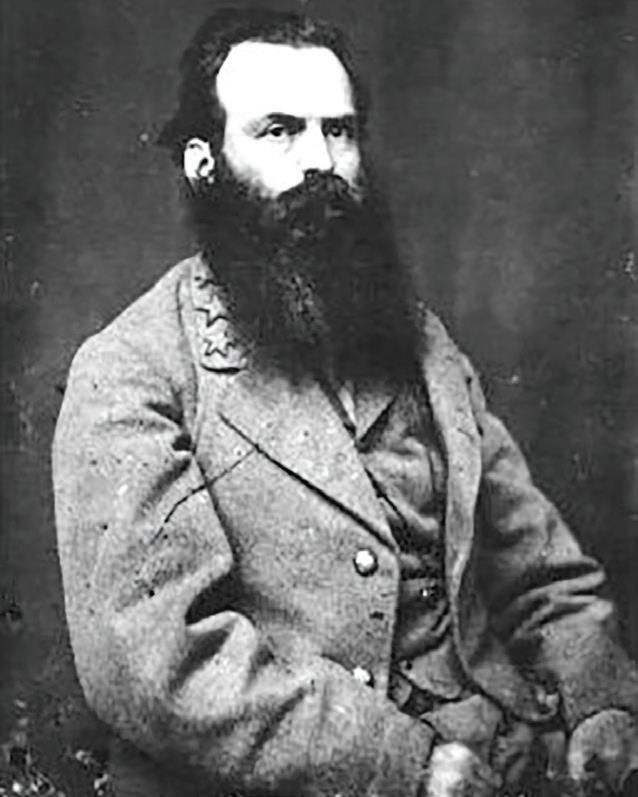

More impressed with Southern leaders and officers over their Yankee counterparts, the Englishman Arthur Fremantle seemed to favor James Longstreet particularly, who he wrote is "never far from General Lee, who relies very much on his judgement."

Arthur James Lyon Fremantle's account of the Army of Northern Virginia during the days leading up to and including the Battle of Gettysburg convey the urgency of those heady days of July 1863 when the outcome of the Civil War seemed to be at stake.

Fremantle's arrival in Lee's camp was a circuitous one. He traveled through South Texas - where he met Sam Houston - Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, and finally drinking tea in Richmond with Jefferson Davis.

The British officer caught up with the Army of Northern Virgina on June 26, crossing the Potomac at Williamsport just hours after Lee and Longstreet had crossed the river. Arriving that evening at Hagerstown, Fremantle was warmly received by Longstreet's military family during the rest of the campaign.

Fremantle watched the end of the first day's meeting engagement from a tall tree on Seminary Ridge. From this same tree, he watched the arrival of Longstreet's troops in the afternoon of July 2, watching the battle from field glasses as it raged in the southern part of the battlefield. The events of July 3 included in this excerpt are from his memoirs of the war, published in London at the end of 1863 as ThreeMonthsintheSouthern States . The work is based on his diary, which he kept during his months in America. Fremantle's travels were not limited to the South. Departing the Confederate camps on July 7, he was handled roughly by federal authorities, ultimately convincing them that he was not a spy but a weary English traveler. Ironically enough, arriving in New York City on July 12, he witnessed one of the most violent insurrections in American history known as the New York Draft riots, where angry mobs of white people - fed up with the politics of the troubled times - sought revenge on those they saw as the cause of their troubles.

Fremantle's book saw brief popularity in the British community and in 1864 was reprinted in New York and Mobile, Alabama, but interest waned with the end of the war. In 1952, the popular historian Walter Lord published a revised edition rekindling interest in Fremantle's work.

the middle of day. Some were walking alone on crutches composed of two rifles, others were supported by men less badly wounded than themselves, and others were carried on stretchers by the ambulance corps; but in no case did I see a sound man helping the wounded to the rear, unless he carried the red badge of the ambulance corps. They were still under a heavy fire; the shells were continually bringing down great limbs of trees and carrying further destruction amongst this melancholy procession. I saw all this in much less time than it takes to write it, and although astonished to meet such vast numbers of wounded, I had not seen enough to give me an idea of the real extent of the mischief.

When I got close up to General Longstreet, I saw one of his regiments advancing through the woods in good order; so, thinking I was just in time to see the attack, I remarked to the General that "I wouldn't have missed this for anything" Longstreet was seated at the top of a snake fence at the edge of the wood, and looking perfectly calm and imperturbed. He replied, laughing, "The devil you wouldn't! I would like to have missed it very much; we've attacked and been repulsed: look there!"

For the first time I then had a view of the open space between the two positions, and saw it covered with Confederates slowly and sulkily returning towards us in small broken parties, under a heavy fire of artillery. But the fire where we were was not so had as further to the rear; for although the air seemed alive with shell, yet the greater number burst behind us.

The General told me that Pickett's Division had succeeded in carrying the enemy's position and capturing his guns, but after remaining there twenty minutes, it had been forced to retire, on the retreat of Heth and Pettigrew on its left. No person could have been more calm or self-possessed than General Longstreet under these trying circumstances, aggravated as they now were by the movements of the enemy, who began

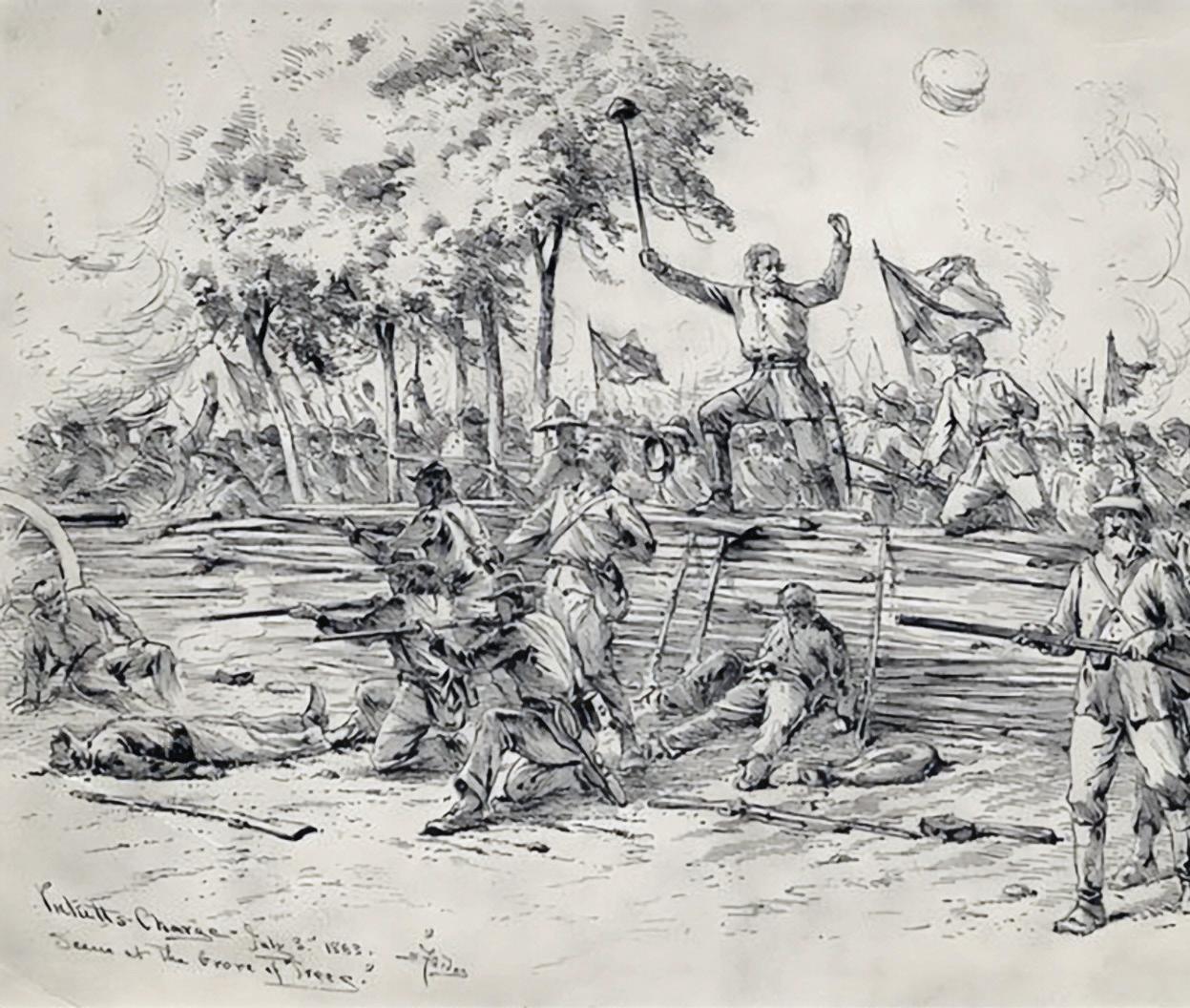

A wildly exaggerated depiction of General Armistead's assault of July 3rd; the reality is that few, if any without being captured, breached the Union works on Cemetery Ridge.

to show a strong disposition to advance. I could now thoroughly appreciate the term bulldog, which I had heard applied to him by the soldiers. Difficulties seem to make no other impression upon him than to make him a little more savage.

Major Walton was the only officer with him when I came upall the rest had been put into the charge. In a few minutes Major Latrobe arrived on foot, carrying his saddle, having just had his horse killed. Colonel Sorrell was also in the same predicament, and Captain Goree's horse was wounded in the mouth.

The General was making the best arrangements in his power to resist the threatened advance, by advancing some artillery, rallying the stragglers, &c. I remember seeing a General (Pettigrew, I think it was). This officer was afterwards killed at the passage of the Potomac come up to him, and report that "he was unable to bring his men up again." Longstreet turned upon him and replied, with some sarcasm: "Very well; never mind, then, General; just let them remain where they are: the enemy's going to advance, and it will spare you the trouble."

Fremantle was positioned in the most suitable place to observe General Robert E. Lee's composure following the defeat of Pickett's Charge. Much of the post-battle accolades given to Lee began with Fremantle's description of Lee's words as he met his defeated troops: "This has been MY fault—it is I that have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it in the best way you can."

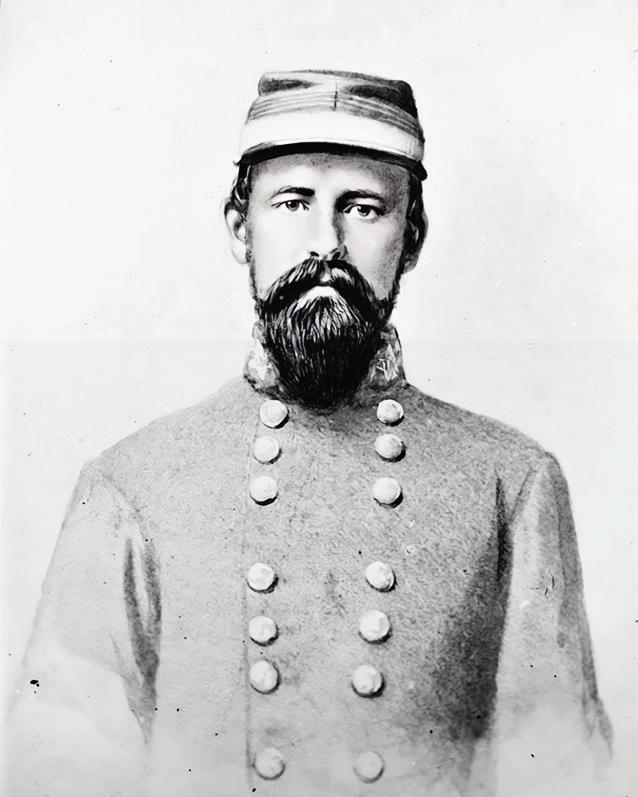

James Kemper (l), image believed to be Richard B. Garnett (c), and Lewis Armistead (r) were the three brigade commanders of Pickett's Division. Only Kemper survived although he was seriously wounded.

He asked for something to drink: I gave him some run out of my silver flask, which I begged he would keep in remembrance of the occasion; he smiled, and, to my great satisfaction, accepted the memorial. He then went off to give some orders to McLaws's Division. Soon afterwards I joined General Lee, who had in the meanwhile come to that part of the field on becoming aware of the disaster. If Longstreet's conduct was admirable, that of General Lee was perfectly subline. He was engaged in rallying and in encouraging the broken troops and was riding about a little in front of the wood, quite alone - the whole of his staff being engaged in a similar manner further to the rear. His face, which is always placid and cheerful, did not show signs of the slightest disappointment, care, or annoyance; he was addressing to every soldier he met a few words of encouragement, such as, "All this will come right in the end: we'll talk it over afterwards; but, in the meantime, all good men must rally. We want all good and true men just now," &c. He spoke to all the wounded men that passed him, and the slightly wounded he exhorted "to bind up their hurts and take up a musket" in this emergency. Very few failed to answer his appeal, and I saw many badly wounded men take off their hats and cheer him. He said to me, "This has been a sad day for us, Colonel--a sad day; but we can't expect always to gain victories." He was also kind enough to advise me to get into some more sheltered position, as the shells were bursting round us with considerable frequency.

Notwithstanding the misfortune which had so suddenly befallen him, General Lee seemed to observe everything, however trivial. When a mounted officer began licking his horse for shying at the bursting of a shell, he called out: "Don't whip him, Captain; don't whip him. I've got just such another foolish horse myself, and whipping does no good."

I happened to see a man lying flat on his face in a small ditch, and I remarked that I didn't think he seemed dead; this drew General Lee's attention to the man, who commenced groaning dismally. Finding appeals to his patriotism of no avail, General Lee had him ignominiously set on his legs by some neighbor-

ing gunners.

I saw General Wilcox (an officer who wears a short round jacket and a battered straw hat) come up to him, and explain, almost crying, the state of his brigade. General Lee immediately shook hands with him and said cheerfully, "Never mind, General, all this has been MY fault - it is I that have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it in the best way you can." In this manner I saw General Lee encourage and reanimate his somewhat dispirited troops, and magnanimously take upon his own shoulders the whole weight of the repulse. It was impossible to look at him or to listen to him without feeling the strongest admiration, and I never saw any man fail him except the man in the ditch.

It is difficult to exaggerate the critical state of affairs as they appeared about this time. If the enemy or their general had shown any enterprise, there is no saying what might have happened. General Lee and his officers were evidently fully impressed with a sense of the situation, yet there was much less noise, fuss, or confusion of orders than at an ordinary field day; the men, as they were rallied in the wood, were brought up in detachments, and lay down quietly and coolly in the positions assigned to them.

We heard that Generals Garnett and Armistead were killed, and General Kemper mortally wounded; also, that Pickett's division had only one field officer unhurt. Nearly all this slaughter took place in an open space about one mile square, and within one hour. At 6 P. M. we heard a long and continuous

Yankee cheer, which we at first imagined was an indication of an advance; but it turned out to be their reception of a general officer, whom we saw riding down the line, followed by about thirty horsemen. Soon afterwards I rode to the extreme front, where there were four pieces of rifled cannon almost without any infantry support. To the nonwithdral of these guns is to be attributed the otherwise surprising inactivity of the enemy. I was immediately surrounded by a sergeant and about half-a-dozen gunners, who seemed in excellent spirits and full of confidence, in spite of their exposed situation. The sergeant expressed his ardent hope that the Yankees might have spirit enough to advance and receive the dose he had in readiness for them. They spoke in admiration of the advance of Pickett's Division, and of the manner in which Pickett himself had led it. When they observed General Lee they said, "We've not lost confidence in the old man: this day's work won't do him no harm. 'Uncle Robert' will get us into Washington yet; you bet he will!" &c. Whilst we were talking, the enemy's skirmishers began to advance slowly, and several ominous sounds in quick succession told us that we were attracting their attention, and that it was necessary to break up the conclave. I therefore turned round and took leave of these cheery and plucky gunners.

At 7 P. M., General Lee received a report that Johnston's division of Ewell's corps had been successful on the left, and had gained important advantages there. Firing entirely ceased in our front about this time; but we now heard some brisk musketry on our right, which I afterwards learned proceeded from Hood's Texans, who had managed to surround some enterprising Yankee cavalry, and were slaughtering them with great satisfaction. Only eighteen out of four hundred are said to have escaped.

At 7.30, all idea of a Yankee attack being over, I rode back to Moses's tent, and found that worthy commissary in very low spirits, all sorts of exaggerated rumors having reached him. On my way, I met a great many wounded men, most anxious to inquire after Longstreet, who was reported killed; when I assured them he was quite well, they seemed to forget their own pain in the evident pleasure they felt in the safety of their chief. No words that I can use will adequately express the extraordinary patience and fortitude with which the wounded Confederates bore their sufferings.

I got something to eat with the doctors at 10 p.m, the first for fifteen hours. I gave up my horse today to his owner, as from death and exhaustion, the staff are almost without horses.

CREDITS: ThreeMonthsintheSouthernStates , by Arthur Fremantle, 1863. All photographs courtesy of Library of Congress unless otherwise noted. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. "Pickett's Charge, July 2, 1863" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-fa46-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99; Fremantle's grave: Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave. com/memorial/12745678/arthur_james_lyon-fremantle: accessed May 14, 2024); Fremantle on horse (cover), NPG Ax50875, National Portrait Gallery,

Arthur Fremantle's adventures did not end with his return to England after the Gettysburg Campaign. He was promoted to Major General in 1882 and served as a Governor in the Sudan. In 1894, he was appointed the Governor of Malta. He died in London in 1901 at the age of sixty-five.

The story does not end there - Fremantle's headstone was laid flat in 1935 and subsequently lost to history. The grave was discovered by an Englishman who portrays Fremantle in reenactments, and a more permanent plaque was erected in 2001 to memorialize the contribution Fremantle's memoir made to the Civil War.

EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF

CHARGE, JULY 3, 1863

FRANK HASKELL, AN AIDE ON THE STAFF OF GENERAL JOHN GIBBON, WAS POSITIONED ON THE THIRD OF JULY AT PERHAPS THE MOST SALIENT POINT ON CEMETERY RIDGE AT GETTYSBURG. DAYS LATER, IN WHAT BRUCE CATTON WOULD RECALL AS "ONE OF THE GENUINE CLASSICS OF CIVIL WAR LITERATURE," HASKELL - IN A LETTER TO HIS BROTHER - WOULD PEN ONE OF THE MOST POIGNANT MEMOIRS OF THE DRAMATIC EVENTS OF THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG. THIS EXCERPT FROM HIS MEMOIR IS A VIVID DESCRIPTION OF THE REPULSE OF PICKETT'S CHARGE.

The distinct sharp sound of one of the enemy's guns, square over to the front, caused us to open our eyes and turn them in that direction, when we saw directly above the crest the smoke of the bursting shell, and heard its noise. In an instant, before a word was spoken, as if that was the signal gun for general work, loud, startling, booming, the report of gun after gun in rapid succession smote our ears and their shells plunged down and exploded all around us. We sprang to our feet. In briefest time the whole Rebel line to the West was pouring out its thunder and its iron upon our devoted crest. The wildest confusion for a few moments obtained sway among us. The shells came bursting all about. The servants ran terror-stricken for dear life and disappeared. The horses, hitched to the trees or held by the slack hands of orderlies, neighed out in fright, and broke away and plunged riderless through the fields. General [Gibbon] at the first had snatched his sword, and started on foot for the front. I called for my horse; nobody responded. I found him tied to a tree nearby, eating oats with an air of the greatest composure, which under the circumstances, even then, struck me as exceedingly ridiculous. He alone, of all beasts or men near was cool. I am not sure but that I learned a lesson then from a horse. Anxious alone for his oats, while I put on the bridle and adjusted the halter, he delayed me by keeping his head down, so I had time to see one of the horses of our mess wagon struck and torn by a shell. The pair plunge--the driver has lost the reins--horses, driver and wagon go into a heap by a tree. Two mules close at hand, packed with boxes of ammunition, are knocked all to pieces by a shell. General Gibbon's groom has just mounted his horse and is starting to take the General's horse to him, when the flying iron meets him and tears open his breast. He drops dead and the horses gallop away.

No more than a minute since the first shot was fired, and I am mounted and riding after the General. The mighty din that now rises to heaven and shakes the earth is not all of it the

voice of the rebellion; for our guns, the guardian lions of the crest, quick to awake when danger comes, have opened their fiery jaws and begun to roar--the great hoarse roar of battle. I overtake the General halfway up to the line. Before we reach the crest his horse is brought by an orderly. Leaving our horses just behind a sharp declivity of the ridge, on foot we go up among the batteries. How the long streams of fire spout from the guns, how the rifled shells hiss, how the smoke deepens and rolls. But where is the infantry? Has it vanished in smoke? Is this a nightmare or a juggler's devilish trick? All too real.

The men of the infantry have seized their arms, and behind their works, behind every rock, in every ditch, wherever there is any shelter, they hug the ground, silent, quiet, unterrified, little harmed. The enemy's guns now in action are in position at their front of the woods along the second ridge that I have before mentioned and towards their right, behind a small crest in the open field, where we saw the flags this morning. Their line is some two miles long, concave on the side towards us, and their range is from one thousand to eighteen hundred yards. A hundred and twenty-five rebel guns, we estimate, are now active, firing twenty-four pound, twenty, twelve and ten-pound projectiles, solid shot and shells, spherical, conical, spiral. The enemy's fire is chiefly concentrated upon the position of

Detail of the artist Paul Philippoteaux's famed cyclorama of an exploding limber box of a Union gun during the cannonade that preceded the Confederate assault on Cemetery Ridge.

the Second Corps. From the Cemetery to Round Top, with over a hundred guns, and to all parts of the enemy's line, our batteries reply, of twenty and ten-pound Parrotts, tenpound rifled ordnance, and twelve-pound Napoleons, using projectiles as various in shape and name as those of the enemy. Captain Hazard commanding the artillery brigade of the Second Corps was vigilant among the batteries of his command, and they were all doing well. All was going on satisfactorily. We had nothing to do, therefore, but to be observers of the grand spectacle of battle. Captain Wessels, Judge Advocate of the Division, now joined us, and we sat down behind the crest, close to the left of Cushing's Battery, to bide our time, to see, to be ready to act when the time should come, which might be at any moment.

Who can describe such a conflict as is raging around us? To say that it was like a summer storm, with the crash of thunder, the glare of lightning, the shrieking of the wind, and the clatter of hailstones would be weak. The thunder and lightning of these two hundred and fifty guns and their shells, whose smoke darkens the sky, are incessant, all-pervading, in the air above our heads, on the ground at our feet, remote, near, deafening, ear-piercing, astounding; and these hailstones are massy iron, charged with exploding fire. And there is little of human interest in a storm; it is an absorbing element of this. You may see flame and smoke, and hurrying men, and human passion at a great conflagration; but they are all earthly and nothing more. These guns are great infuriate demons, not of the earth, whose mouths blaze with smoky tongues of living fire, and whose murky breath, sulphur-laden, rolls around them and along the ground, the smoke of Hades. These grimy men, rushing, shouting, their souls in frenzy, plying the dusky globes and the igniting spark, are in their league, and but their willing ministers.

We thought that at the second Bull Run, at the Antietam and at Fredericksburg on the 11th of December, we had heard heavy cannonading; they were but holiday salutes compared with this. Besides the great ceaseless roar of the guns, which was but the background of the others, a million various minor sounds engaged the ear. The projectiles shriek long and sharp. They hiss, they scream, they growl, they sputter; all sounds of life and rage; and each has its different note, and all are discordant. Was ever such a chorus of sound before? We note the effect of the enemies' fire among the batteries and along the crest. We see the solid shot strike axle, or pole, or wheel, and the tough iron and heart of oak snap and fly like straws. The great oaks there by Woodruff 's guns heave down their massy branches with a crash, as if the lightning smote them. The shells swoop down among the battery horses standing there

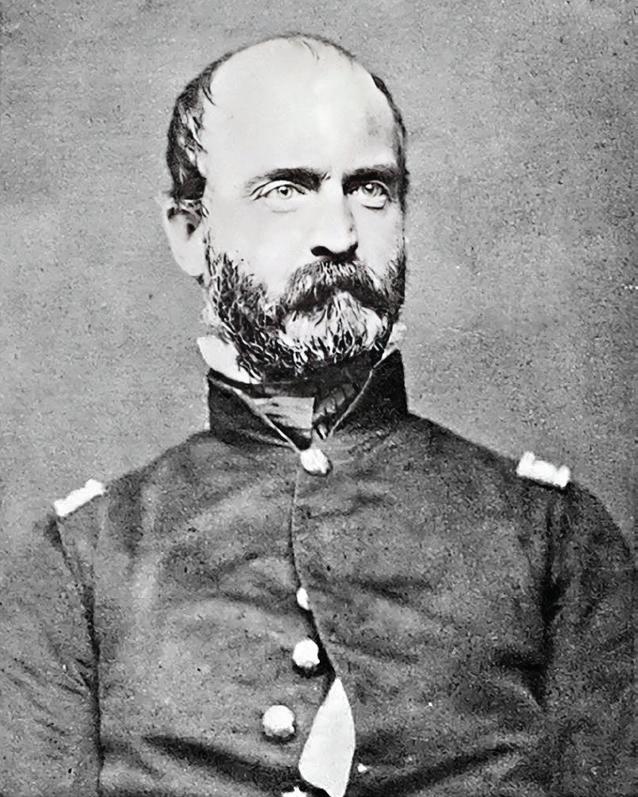

Born in Vermont in 1828, Frank Aretas Haskell graduated with distinguished honors from Dartmouth in the class of 1854. He immediately entered into practicing law, which would have likely been his lifetime's vocation had not the fate of war intervened. Commissioned a first lieutenant, Company I, 6th Wisconsin in June 1861, he served as adjutant until April 1862 when he was called to serve as aide-de-camp to General John Gibbons.

Haskell's experience as Gibbon's aide placed him in a unique position to recall the events of Gettysburg. In February 1864, Haskell was promoted to colonel of the 36th Wisconsin until he was struck in the head with a bullet at Cold Harbor dying instantly on June 3, 1864. Haskell's historical account of the Battle of Gettysburg is not just a memoir but a testament to the human spirit in the face of adversity. Penned in a long, 72-page letter to his brother, it provides a detailed and vivid account of the horrors and heroism he witnessed. Originally not intended for public consumption, this personal narrative was published as a pamphlet fifteen years after the battle. Its significance was further recognized when Dartmouth College reprinted it in 1898 as part of the history of the class of 1854.

The version included here, focusing on Pickett's Charge, is from the 1908 edition published by the Wisconsin History Commission, a testament to its enduring historical value. His work is not intended to be a definitive account of the events of July 3; rather, it represents the views of one man who wished to memorialize the courage and chaos he saw on that fateful day in Pennsylvania.

apart. A half a dozen horses start, they tumble, their legs stiffen, their vitals and blood smear the ground. And these shot and shells have no respect for men either. We see the poor fellows hobbling back from the crest, or unable to do so, pale and weak, lying on the ground with the mangled stump of an arm or leg, dripping their life blood away, or with a cheek torn open, or a shoulder mashed. And many, alas! hear not the roar as they stretch upon the ground with upturned faces and open eyes, though a shell should burst at their very ears. Their ears and their bodies this instant are only mud. We saw them but a moment since there among the flame, with brawny arms and muscles of iron wielding the rammer and pushing home the cannon's plethoric load.

Strange freaks these round shot play! We saw a man coming up from the rear with his full knapsack on, and some canteens of water held by the straps in his hands. He was walking slowly and with apparent unconcern, though the iron hailed around him. A shot struck the knapsack, and it, and its contents flew thirty yards in every direction, the knapsack disappearing like an egg, thrown spitefully against a rock. The soldier stopped and turned about in puzzled surprise, put up one hand to his back to assure himself that the knapsack was not there, and then walked slowly on again unharmed, with not even his coat torn. Near us was a man crouching behind a small disintegrated stone, which was about the size of a common water bucket. He was bent up, with his face to the ground, in the attitude of a Pagan worshipper before his idol. It looked so absurd to see him thus, that I went and said to him, "Do not lie there like a toad. Why not go to your regiment and be a

battery, and at the same instant, another shell over a neighboring box. In both the boxes the ammunition blew up with an explosion that shook the ground, throwing fire and splinters and shells far into the air and all around, and destroying several men. We watched the shells bursting in the air, as they came hissing in all directions. Their flash was a bright gleam of lightning radiating from a point, giving place in the thousandth part of a second to a small, white, puffy cloud, like a fleece of the lightest, whitest wool. These clouds were very numerous. We could not often see the shell before it burst; but sometimes, as we faced towards the enemy, and looked above our heads, the approach would be heralded by a prolonged hiss, which always seemed to me to be a line of something tangible, terminating in a black globe, distinct to the eye, as the sound had been to the ear. The shell would seem to stop, and hang suspended in the air an instant, and then vanish in fire and smoke and noise. We saw the missiles tear and plow the ground. All in rear of the crest for a thousand yards, as well as among the batteries, was the field of their blind fury. Ambulances, passing down the Taneytown Road with wounded men, were struck. The hospitals near

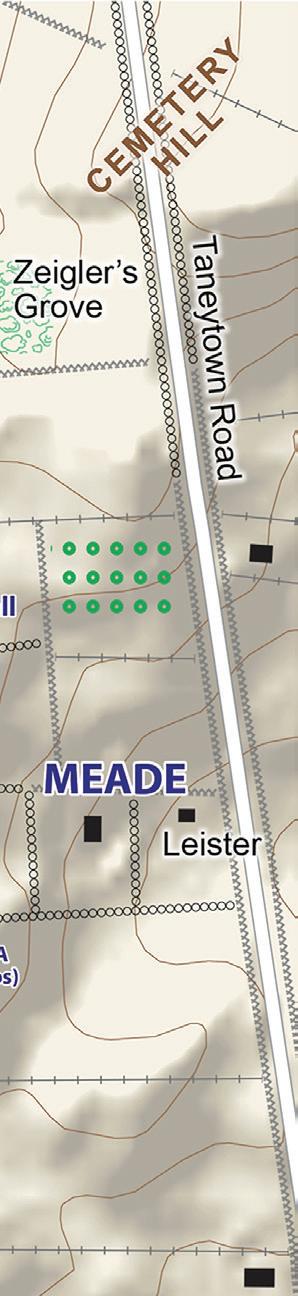

A PANORAMIC VIEW OF THE BATTLEFIELD LOOKING EAST WITH TANEYTOWN ROAD IN THE FOREGROUND AND CEMETERY HILL IN THE DISTANCE

man?" He turned up his face with a stupid, terrified look upon me, and then without a word turned his nose again to the ground. An orderly that was with me at the time, told me a few moments later, that a shot struck the stone, smashing it in a thousand fragments, but did not touch the man, though his head was not six inches from the stone.

All the projectiles that came near us were not so harmless. Not ten yards away from us a shell burst among some small bushes, where sat three or four orderlies holding horses. Two of the men and one horse were killed. Only a few yards off a shell exploded over an open limber box in Cushing's

this road were riddled. The house which was General Meade's headquarters was shot through several times, and a great many horses of officers and orderlies were lying dead around it. Riderless horses, galloping madly through the fields, were brought up, or down rather, by these invisible horse-tamers, and they would not run any more. Mules with ammunition, pigs wallowing about, cows in the pastures, whatever was animate or inanimate, in all this broad range, were no exception to their blind havoc. The percussion shells would strike, and thunder, and scatter the earth and their whistling fragments; the Whitworth bolts would pound and ricochet, and bowl far away sputtering, with the sound of a mass of hot iron plunged in water; and the

great solid shot would smite the unresisting ground with a sounding "thud," as the strong boxer crashes his iron fist into the jaws of his unguarded adversary. Such were some of the sights and sounds of this great iron battle of missiles. Our artillerymen upon the crest budged not an inch, nor intermitted, but, though caisson and limber were smashed, and guns dismantled, and men and horses killed, there amidst smoke and sweat, they gave back, without grudge, or loss of time in the sending, in kind whatever the enemy sent, globe, and cone, and bolt, hollow or solid, an iron greeting to the rebellion, the compliments of the wrathful Republic. An hour has droned its flight since first the war began. There is no sign of weariness or abatement on either side. So long it seemed, that the din and crashing around began to appear the normal condition of nature there, and fighting man's element. The General proposed to go among the men and over to the front of the batteries, so at about two o'clock he and I started. We went along the lines of the infantry as they lay there flat upon the earth, a little to the front of the batteries. They were suffering little, and were quiet and cool. How glad we were that the enemy were no better gunners, and that they cut the shell fuses too long. To the question asked the men, "What do you think of this?"

the replies would be, "O, this is bully," "We are getting to like it," "O, we don't mind this." And so they lay under the heaviest cannonade that ever shook the continent, and among them a thousand times more jokes than heads were cracked.

We went down in front of the line some two hundred yards, and as the smoke had a tendency to settle upon a higher plain than where we were, we could see near the ground distinctly all over the fields, as well back to the crest where were our own guns as to the opposite ridge where were those of the enemy. No infantry was in sight, save the skirmishers, and they stood silent and motionless--a row of gray posts through the field on one side confronted by another of blue. Under the grateful shade of some elm trees, where we could see much of the field, we made seats of the ground and sat down. Here all the more repulsive features of the fight were unseen, by reason of the smoke. Man had arranged the scenes, and for a time had taken part in the great drama; but at last, as the plot thickened, conscious of his littleness and inadequacy to the mighty part, he had stepped aside and given place to more powerful actors. So

GENERAL WINFIELD HANCOCK, COMMANDER OF UNION 2ND CORPS, AND HIS STAFF AS HE DIRECTS TROOPS ON THE AFTERNOON OF JULY 3, 1863.

it seemed; for we could see no men about the batteries. On either crest we could see the great flaky streams of fire, and they seemed numberless, of the opposing guns, and their white banks of swift, convolving smoke; but the sound of the discharges was drowned in the universal ocean of sound. Overall the valley the smoke, a sulphury arch, stretched its lurid span; and through it always, shrieking on their unseen courses, thickly flew a myriad iron deaths. With our grim horizon on all sides round toothed thick with battery flame, under that dissonant canopy of warring shells, we sat and heard in silence. What other expression had we that was not mean, for such an awful universe of battle?

Ashell struck our breastwork of rails up in sight of us, and a moment afterwards we saw the men bearing some of their wounded companions away from the same spot; and directly two men came from there down toward where we were and sought to get shelter in an excavation near by, where many dead horses, killed in yesterday's fight, had been thrown. General Gibbon said to these men, more in a tone of kindly expostulation than of command: "My men, do not leave your ranks to try to get shelter here. All these matters are in the hands of God, and nothing that you can do will make you safer in one place than in another." The

men went quietly back to the line at once. The General then said to me: "I am not a member of any church, but I have always had a strong religious feeling; and so in all these battles I have always believed that I was in the hands of God, and that I should be unharmed or not, according to his will. For this reason, I think it is, I am always ready to go where duty calls, no matter how great the danger." Half-past two o'clock, an hour and a half since the commencement, and still the cannonade did not in the least abate; but soon thereafter some signs of weariness and a little slacking of fire began to be apparent upon both sides. First, we saw Brown's battery retire from the line, too feeble for further battle. Its position was a little to the front of the line. Its commander was wounded, and many of its men were so, or worse; some of its guns had been disabled, many of its horses killed; its ammunition was nearly expended. Other batteries in similar case had been withdrawn before to be replaced by fresh ones, and some were withdrawn afterwards. Soon after the battery named had gone the General and I started to return, passing towards the left of the division, and crossing the ground where the guns had stood. The stricken horses were numerous, and the dead and wounded men lay about, and as we passed these latter, their low, piteous call for water would invariably come to us, if they had yet any voice left. I found canteens of water near - no difficult matter where a battle has been - and held them to livid lips, and even in the faintness of death the eagerness to drink told of their terrible torture of thirst. But we must pass on. Our infantry was still unshaken, and in all the cannonade suffered very little. The batteries had been handled much more severely. I am unable to give any figures. A great number of horses had been killed, in some batteries more than half of all. Guns had been dismounted. A great many caissons,

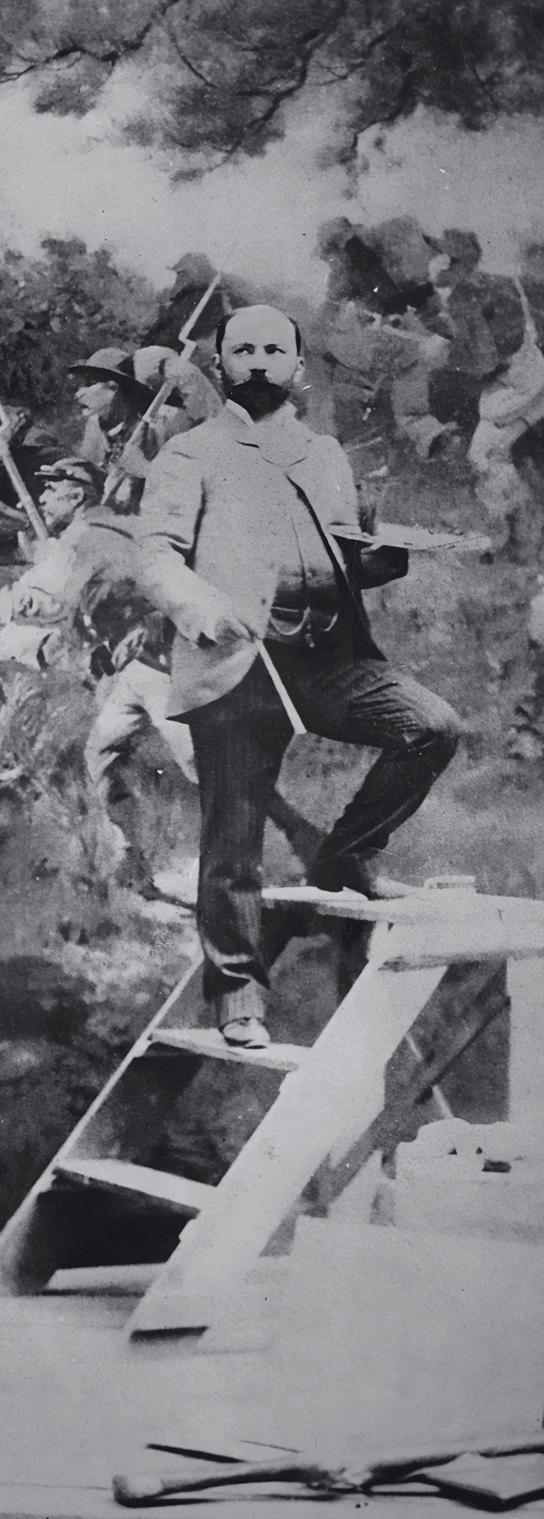

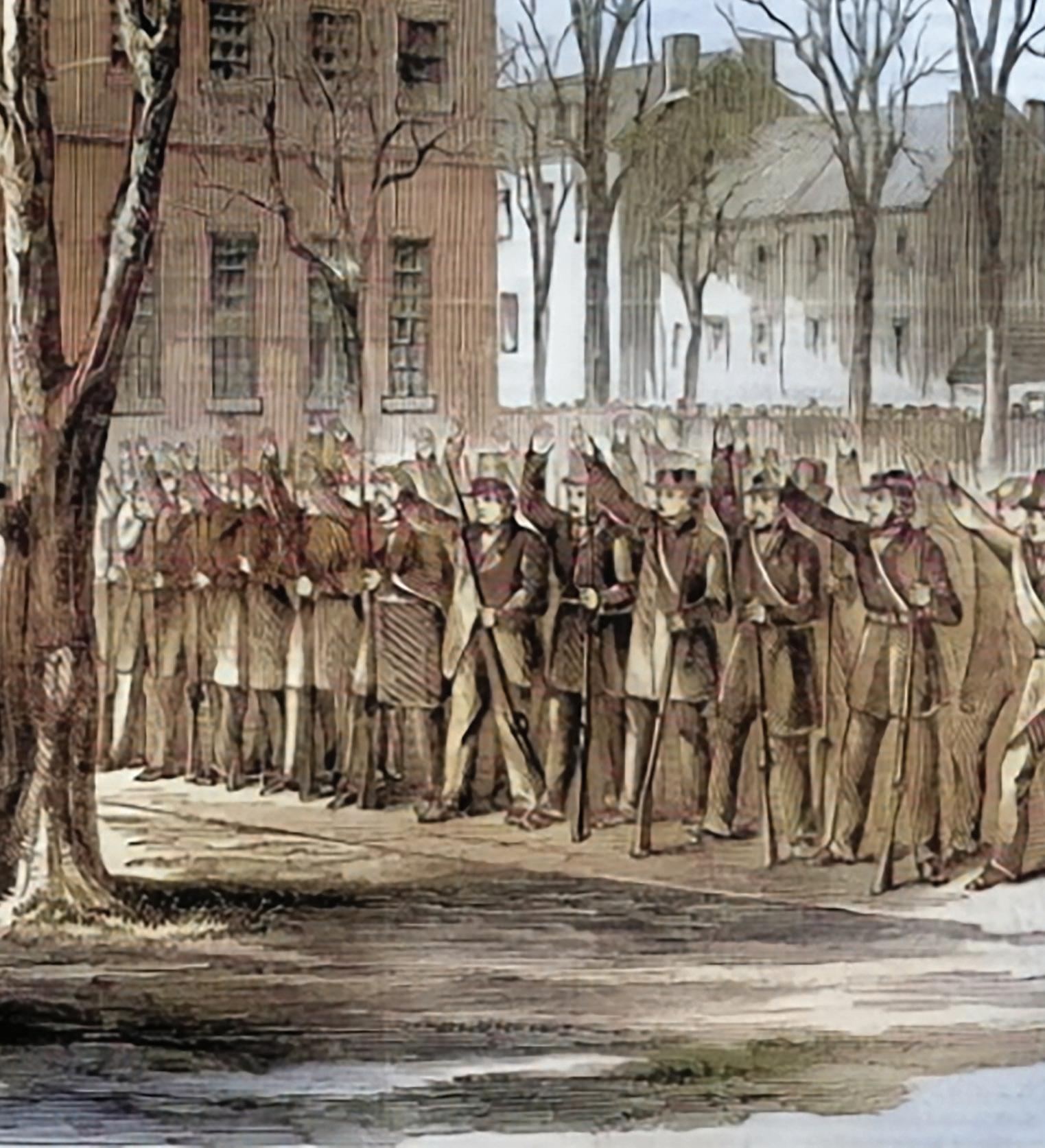

The detailed images that supplement Haskell's memoir in this edition are from the painting by Paul Philippoteaux, "The Battle of Gettysburg." Completed in 1884 in the cycloramic format popular in the nineteenth century, standing in the middle viewers could get the effect of a 360-degree image — longer than a football field — showing many of the critical moments of the Union Army's triumph on Cemetery Ridge on the afternoon of July 3, 1863.

The celebrated French artist and a team of twenty painters created four identical paintings based on sketches, battlefield photographs, interviews, and historical accounts. The project was commissioned in 1879 by a group of Chicago investors and completed five years later. In April 1882, Philippoteaux visited Gettysburg, where he erected a wooden platform on present-day Hancock Avenue to provide the best vantage point. During his visit to Gettysburg, the painter interviewed Union and Confederate survivors, including Winfield Hancock and Alexander Webb, who are featured prominently in Haskell's account. The local Gettysburg photographer William Tipton was hired to take a 360-degree photograph of the battlefield. He continued adding details as eyewitnesses brought things to his attention. The work took a uniquely unbiased view of the politically charged battle.

The original work was exhibited in Chicago in 1883, where General Gibbon reportedly was impressed and veterans were brought to tears. A second version was exhibited in Boston in 1885 where it was initially a commercial success. The painting toured various American cities in the 1880s, but motion pictures replaced the cyclorama movement, and public interest waned.

The painting, a significant piece of history, is now preserved at the Gettysburg National Military Park. The painting at Gettysburg is the Boston version, which, by the turn of the century, had suffered damage from wear and weather. Despite this, it was viewed in its original circular style in Gettysburg for the 50th anniversary of the battle in 1913. A remarkable $12 million restoration was undertaken in 2005, and the restored painting can now be viewed at the Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center, a testament to the enduring legacy of "The Battle of Gettysburg."

THE FRENCH ARTIST SHOWN HERE PAINTING "THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG"

limbers and carriages had been destroyed, and usually from ten to twenty-five men to each battery had been struck, at least along our part of the crest.

Altogether the fire of the enemy had injured us much, both in the modes that I have stated, and also by exhausting our ammunition and fouling our guns, so as to render our batteries unfit for further immediate use. The scenes that met our eyes on all hands among the batteries were fearful. All things must end, and the great cannonade was no exception to the general law of earth. In the number of guns active at one time, and in the duration and rapidity of their fire, this artillery engagement, up to this time, must stand alone and pre-eminent in this war. It has not been often, or many times, surpassed in the battles of the world. Two hundred and fifty guns, at least, rapidly fired for two mortal hours. Cipher out the number of tons of gunpowder and iron that made these two hours hideous.

Of the injury of our fire upon the enemy, except the facts that ours was the superior position, if not better served and constructed artillery, and that the enemy's artillery hereafter during the battle was almost silent, we know little. Of course, during the fight we often saw the enemy's caissons explode, and the trees rent by our shot crashing about his ears, but we can from these alone infer but little of general results. At three o'clock almost precisely the last shot hummed, and bounded and fell, and the cannonade was over. The purpose of General Lee in all this fire of his guns - we know it now, we did not at the time so well - was to disable our artillery and break up our infantry upon the position of the Second Corps, so as to render them less an impediment to the sweep of his own brigades and divisions over our crest and through our lines. He probably supposed our infantry was massed behind the crest and the batteries; and hence his fire was so high, and his fuses to the shells were cut so long, too long. The Rebel General failed in some of his

plans in this behalf, as many generals have failed before and will again. The artillery fight over, men began to breathe more freely, and to ask, What next, I wonder? The battery men were among their guns, some leaning to rest and wipe the sweat from their sooty faces, some were handling ammunition boxes and replenishing those that were empty. Some batteries from the artillery reserve were moving up to take the places of the disabled ones; the smoke was clearing from the crests.

There was a pause between acts, with the curtain down, soon to rise upon the great final act, and catastrophe of Gettysburg. We have passed by the left of the Second Division, coming from the First; when we crossed the crest the enemy was not in sight, and all was still - we walked slowly along in the rear of the troops, by the ridge cut off now from a view of the enemy in his position, and were returning to the spot where we had left our horses. General Gibbon had just said that he inclined to the belief that the enemy was falling back, and that the cannonade was only

ocean of armed men sweeping upon us! Regiment after regiment and brigade after brigade move from the woods and rapidly take their places in the lines forming the assault. Pickett's proud division, with some additional troops, hold their right; Pettigrew's (Worth's) their left. The first line at short interval is followed by a second, and that a third succeeds; and columns between support the lines. More than half a mile their front extends; more than a thousand yards the dull gray masses deploy, man touching man, rank pressing rank, and line supporting line.

The red flags wave, their horsemen gallop up and down; the arms of eighteen thousand men, barrel and bayonet, gleam in the sun, a sloping forest of flashing steel. Right on they move, as with one soul, in perfect order, without impediment of ditch, or wall or stream, over ridge and slope, through orchard and meadow, and cornfield, magnificent, grim, irresistible. All was orderly and still upon our crest;

one of his noisy modes of covering the movement. I said that I thought that fifteen minutes would show that, by all his bowling, the Rebel did not mean retreat.

We were near our horses when we noticed Brigadier General Hunt, Chief of Artillery of the Army, near Woodruff 's Battery, swiftly moving about on horseback, and apparently in a rapid manner giving some orders about the guns. Thought we, what could this mean? In a moment afterwards we met Captain Wessels and the orderlies who had our horses; they were on foot leading the horses. Captain Wessels was pale, and he said, excited: "General, they say the enemy's infantry is advancing." We sprang into our saddles, a score of bounds brought us upon the all-seeing crest. To say that men grew pale and held their breath at what we and they there saw, would not be true. Might not six thousand men be brave and without shade of fear, and yet, before a hostile eighteen thousand, armed, and not five minutes' march away, turn ashy white? None on that crest now need be told that the enemy is advancing. Every eye could see his legions, an overwhelming resistless tide of an

no noise and no confusion. The men had little need of commands, for the survivors of a dozen battles knew well enough what this array in front portended, and, already in their places, they would be prepared to act when the right time should come. The click of the locks as each man raised the hammer to feel with his fingers that the cap was on the nipple; the sharp jar as a musket touched a stone upon the wall when thrust in aiming over it, and the clicking of the iron axles as the guns were rolled up by hand a little further to the front, were quite all the sounds that could be heard. Cap-boxes were slid around to the front of the body; cartridge boxes opened, officers opened their pistol-holsters. Such preparations, little more was needed.

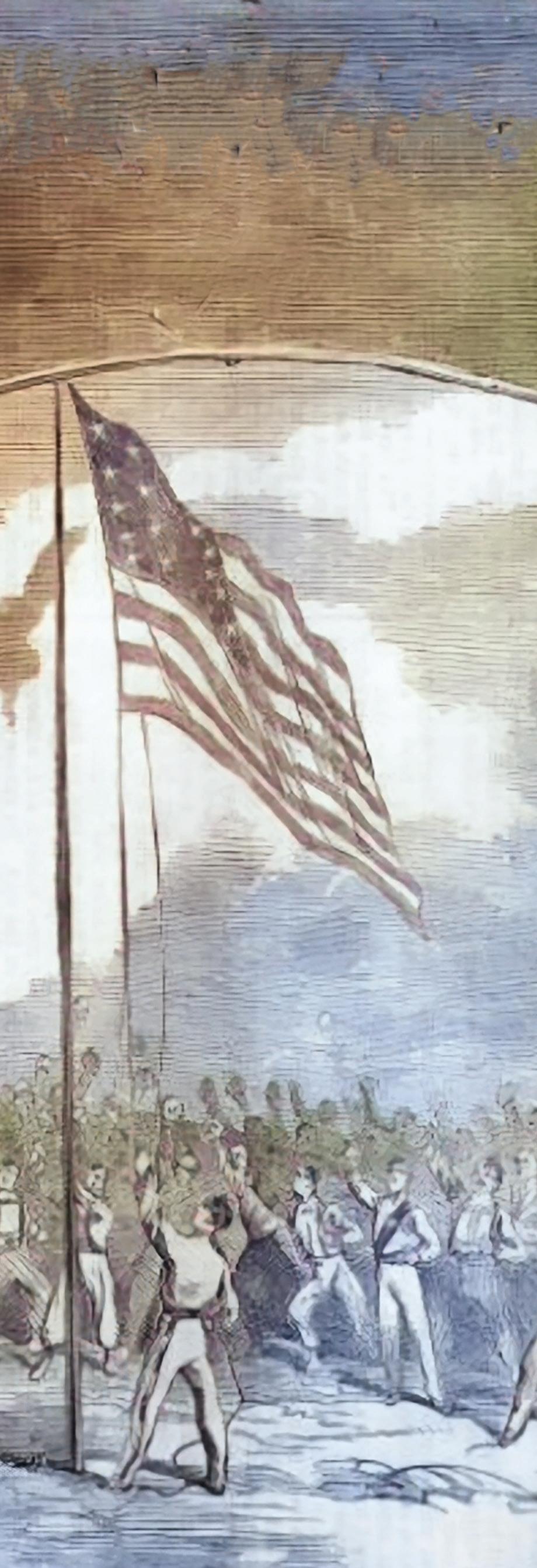

The trefoil flags, colors of the brigades and divisions moved to their places in rear; but along the lines in front the grand old ensign that first waved in battle at Saratoga in 1777, and which these people coming would rob of half its stars, stood up, and the west wind kissed it as the sergeants sloped its lance towards the enemy. I believe that not one above whom it then waved but blessed his God that he

was loyal to it, and whose heart did not swell with pride towards it, as the emblem of the Republic before that treason's flaunting rag in front.

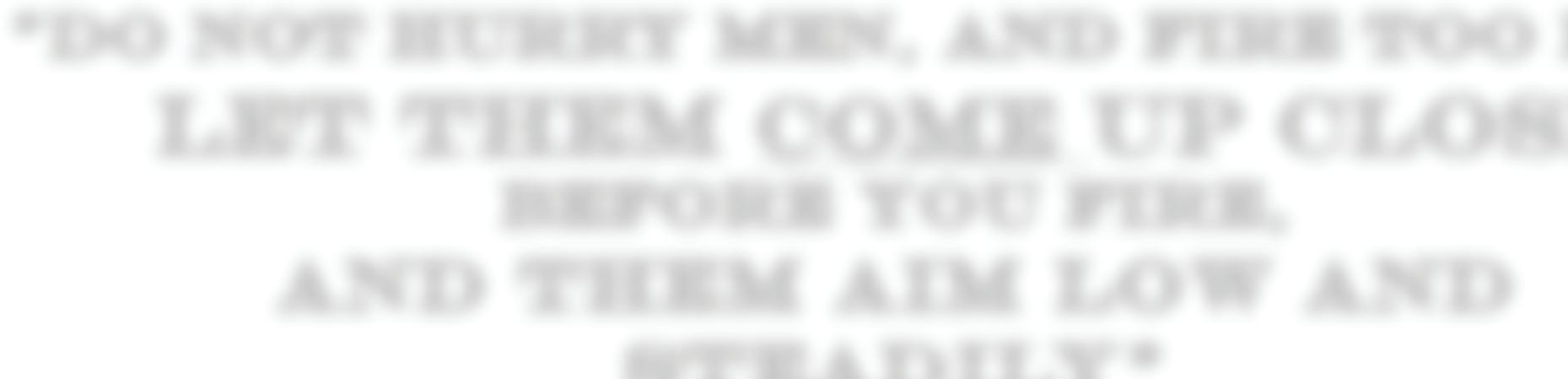

General Gibbon rode down the lines, cool and calm, and in an unimpassioned voice he said to the men, "Do not hurry, men, and fire too fast, let them come up close before you fire, and then aim low and steadily." The coolness of their General was reflected in the faces of his men. Five minutes has elapsed since first the enemy have emerged from the woods--no great space of time surely, if measured by the usual standard by which men estimate duration--but it was long enough for us to note and weigh some of the elements of mighty moment that surrounded us; the disparity of numbers between the assailants and the assailed; that few as were our numbers we could not be supported or reinforced until support would not be needed or would be too late; that upon the ability of the two trefoil divisions to hold the crest and repel the assault depended not only their own safety or destruction, but also the honor of the Army of the Potomac and defeat or victory at Gettysburg. Should these advancing men pierce our line and become the entering wedge, driven home, that would sever our army asunder, what hope would there be afterwards, and where the bloodearned fruits of yesterday? It was long enough for the Rebel storm to drift across more than half the space that had at first separated it from us. None, or all, of these considerations either depressed or elevated us. They might have done the former, had we been timid; the latter had we been confident and vain. But, we were there waiting, and ready to do our duty--that done, results could not dishonor us.

Our skirmishers open a spattering fire along the front, and, fighting, retire upon the main linethe first drops, the heralds of the storm, sounding on our windows. Then the thunders of our guns, first Arnold's then Cushing's and Woodruff's and the rest, shake and reverberate again through the air, and their sounding shells smite the enemy. The General said I had better go and tell General Meade of this advance. To gallop to General Meade's headquarters, to learn there that he had changed them to another part of the field, to dispatch to him by the Signal Corps in General Gibbon's name the message, "The enemy is advancing his infantry in force upon my front," and to be again upon the crest, were but the work of a minute. All our available guns are now active, and from the fire of shells, as the range grows shorter and shorter, they change to shrapnel, and from shrapnel to canister; but in spite of shells, and shrapnel and canister, without wavering or halt, the hardy lines of the enemy continue to move on. The Rebel guns make no reply to ours, and no charging shout rings out to-day, as is the Rebel wont; but the courage of these silent men amid our shots seems not to need the stimulus of other noise. The enemy's right flank sweeps near Stannard's bushy crest, and his concealed Vermonters rake it with a well-delivered fire of musketry. The gray lines do not halt or reply, but withdrawing a little from that extreme, they still move on. And so across all that broad open ground they have come, nearer and nearer, nearly half the way, with our guns bellowing in their faces, until now a hundred yards, no more, divide our ready left from their advancing right. The eager men there are impatient to begin. Let them. First, Harrow's breastworks

THE PIVOTAL MOMENT OF THE BATTLE AS THE CONFEDERATE ADVANCE BREACHES THE UNION LINE. GENERAL WEBB IS SEEN HERE TO THE LEFT ORDERING MEN INTO THE BREACH

flame; then Hall's; then Webb's. As if our bullets were the fire coals that touched off their muskets, the enemy in front halts, and his countless level barrels blaze back upon us. The Second Division is struggling in battle. The rattling storm soon spreads to the right, and the blue trefoils are vieing with the white. All along each hostile front, a thousand yards, with narrowest space between, the volleys blaze and roll; as thick the sound as when a summer hail-storm pelts the city roofs; as thick the fire as when the incessant lightning fringes a summer cloud. When the Rebel infantry had opened fire our batteries soon became silent, and this without their fault, for they were foul by long previous use. They were the targets of the concentrated Rebel bullets, and some of them had expended all their canister. But they were not silent before Rhorty was killed, Woodruff had fallen mor-

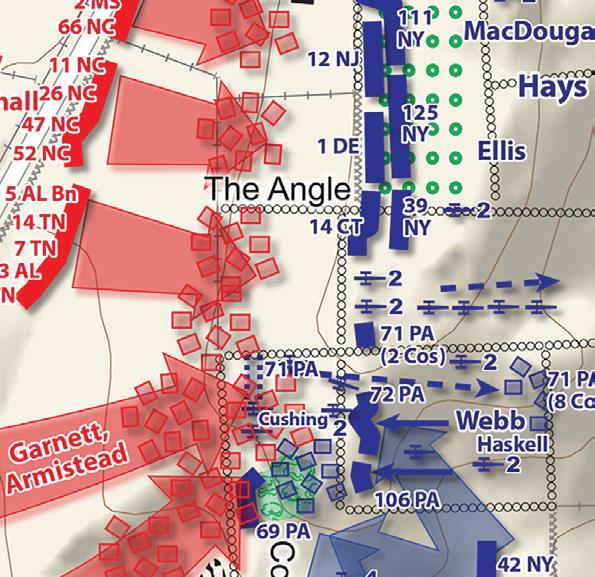

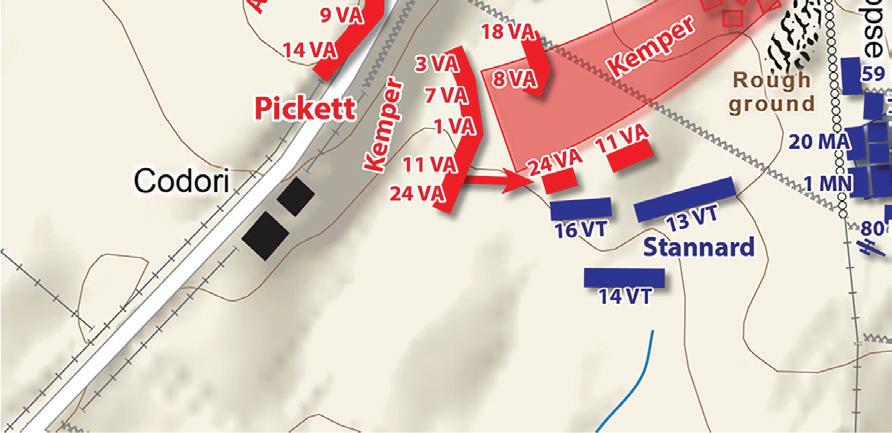

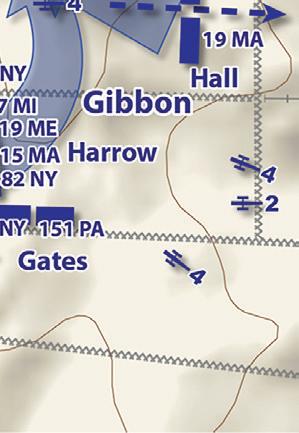

SOME CONSIDER THE HIGH-WATER MARK OF THE CONFEDERACY AS THE FINAL ASSAULT OF JULY 3, 1863 AS A COMBINED FORCE OF 15,000 ATTACKED THE UNION DEFENSES ON CEMETERY RIDGE

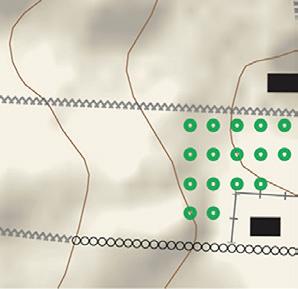

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com.

tally wounded, and Cushing, firing almost his last canister, had dropped dead among his guns shot through the head by a bullet. The conflict is left to the infantry alone. Unable to find my general when I had returned to the crest after transmitting his message to General Meade, and while riding in the search having witnessed the development of the fight, from the first fire upon the left by the main lines until all of the two divisions were furiously engaged, I gave up hunting as useless - I was convinced General Gibbon could not be on the field; I left him mounted; I could easily have found him now had he so remained - but now, save myself, there was not a mounted officer near the engaged linesand was riding towards the right of the Second Division, with purpose to stop there, as the most eligible position to watch the further progress of the battle, there to be ready to take part according to my own notions whenever and wherever occasion was presented.

The conflict was tremendous, but I had seen no wavering in all our line. Wondering how long the Rebel ranks, deep though they were, could stand our sheltered volleys, I had come near my destination, when - great heaven! were

Detail of the artist Paul Philippoteaux's famed cyclorama of the fighting by the stone wall on July 3, 1863. The original massive painting measures over 300 feet in circumference and based on interviews with veterans and tours of the battlefield.

bull. Webb's men are falling fast, and he is among them to direct and encourage; but, however well they may now do, with that walled enemy in front, with more than a dozen flags to Webb's three, it soon becomes apparent that in not many minutes they will be overpowered, or that there will be none alive for the enemy to overpower. Webb, has but three regiments, all small, the 69th, 71st and 72d Pennsylvania - the 106th Pennsylvania, except two companies, is not here to-day - and he must have speedy assistance, or this crest will be lost.

Oh, where is Gibbon? where is Hancock? - some general - anybody with the power and the will to support that wasting, melting line? No general came, and no succor! I thought of Hayes upon the right, but from the smoke and war along his front,

it was evident that he had enough upon his hands, if he stayed the in-rolling tide of the Rebels there. Doubleday upon the left was too far off and too slow, and on another occasion I had begged him to send his idle regiments to support another line battling with thrice its numbers, and this "Old Sumpter Hero" had declined. As a last resort I resolved to see if Hall and Harrow could not send some of their commands to reinforce Webb. I galloped to the left in the execution of my purpose, and as I attained the rear of Hall's line, from the nature of the ground and the position of the enemy it was easy to discover the reason and the manner of this gathering of Rebel flags in front of Webb. The enemy, emboldened by his success in gaining our line by the group of trees and the angle of the wall, was concentrating all his right against and was further pressing that point. There was the stress of his assault; there would he drive his fiery wedge to split our line. In front of Harrow's and Hall's Brigades he had been able to advance no nearer than when he first halted to deliver fire, and these commands had not yielded an inch. To effect the concentration before Webb, the enemy would march the regiment on his extreme right of each of his lines by the left flank to the rear of the troops, still halted and facing to the front, and so continuing to draw in