6 minute read

SUSAN DAVIS

from 2018 Donor Report

by hailstudio

“I feel very fortunate to have spent 14 years with an organization that is faith-based and has a deep sense

of spirituality.” — SUSAN DAVIS

Advertisement

LEADING BY EXAMPLE

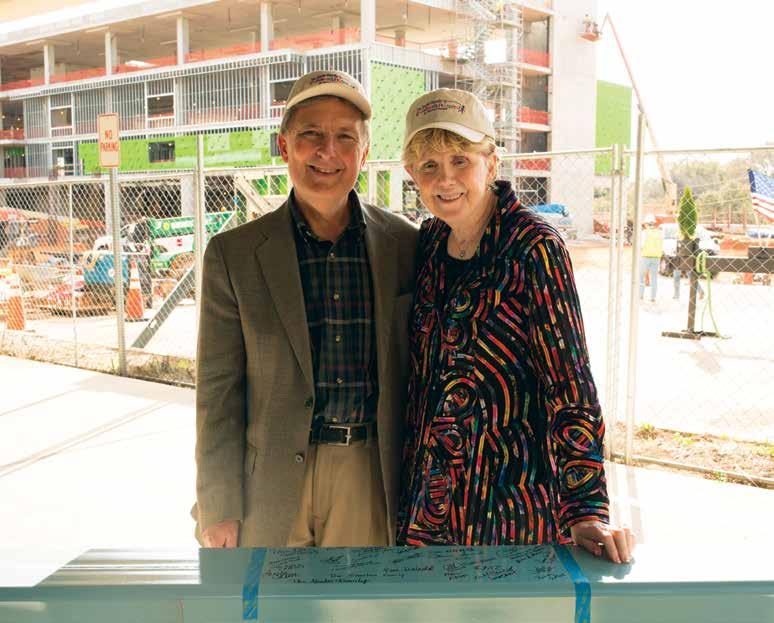

Susan Davis steps up in support of her beliefs with a $1 million gift

BY STEVE BORNHOFT

WWhen Susan Davis’ father believed strongly in something, it didn’t matter to him what was usual or customary. What mattered was doing the right thing.

It was on that basis that Herbert “Lee” Davis went to court seeking custody of his then-only child, who was about to turn 4. Mr. Davis believed Susan’s best interests would be served if he were the parent in her life each day.

“Fathers getting custody, that just didn’t happen in the 1950s,” Susan said. “My father knew what he was up against, but he went forward anyway and he prevailed.

And, from that point forward, he tried always to make sure that my life experiences were not diminished by the fact that there was no mother in my life.

“My dad was both father and mother to me.”

So it was that he escorted Susan to mother-daughter events. And he tried to become a Brownie troop leader.

In that effort, he was ahead of his time, but he felt like he had to try.

Susan completed elementary school in New Jersey and was about to enter junior high when her life suddenly and dramatically changed. Her father wasn’t perfect; he had a weakness for placing bets with bookies. Eventually, that habit translated to financial straits that made moving an imperative and, without warning, Lee Davis packed up the car one day and headed for upstate New York.

“My father had a job selling pharmaceutical drugs for Hoffman-La Roche, and one of his customers was a surgeon who owned a dude ranch,” Susan recalled. “The doctor had always told my father that he could come up to his ranch and get a job anytime he wanted it and, when the need arose, Dad took him up on the offer.”

Mr. Davis became the “social director” for the dude ranch in exchange for room and board. He arranged activities, including square dances, bobsledding, horseback riding and rodeos. During the day, he taught math at a local high school.

Despite his struggles, Lee Davis, who died in 2017, instilled in his daughter a stubborn sense of optimism and a work ethic that may have exceeded his own — so much so that it’s not possible to carry on a conversation with Susan for long without her touching upon one or both those qualities.

As the CEO and President of Sacred Heart Health System, a position she held for six years beginning in 2012, Susan had a small sign in her office that read simply, “It CAN Be Done.” That was an outlook, she said, that she intended for all of her senior managers to embrace.

She is herself an impressive demonstration of the power of that affirmation. And she is a woman, said Carol Carlan, President of the Sacred Heart Foundation, who “has made a difference wherever she has been.”

Susan’s father was newly remarried when she was set to begin her post-secondary educational career. She enrolled first at Orange County Community College in Middletown, New York. Her father had no money for tuition, so Susan both went to school and worked full time, something she would do until finally she earned a master’s degree in Nursing Administration and a doctorate in Education. Her advanced degrees came from Columbia University in New York. She earned her bachelor’s degree from Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, New York.

Along her educational way, she worked as a nurse, nursing officer and chief nurse. While at Columbia, she traveled 80 miles to jobs at Vassar Brothers Medical Center in Poughkeepsie. By the time she earned her doctorate, she was the Chief Operating Officer at the 370-bed medical center and later led the facility as its CEO.

Susan was at Vassar when she was contacted by Bob Henkel, then the COO at Ascension Health. (Bob retired in 2017 from his position as Ascension Executive Vice President.) Bob was looking for someone to take the helm as CEO at St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Bridgeport, Connecticut. And it was Bob who later would ask Susan to lead Sacred Heart Health System.

At St. Vincent’s, Susan did some of her most transformational work in the area of patient safety. She has witnessed unforeseeable technological advances in the course of her career and the arrival of new generations of drugs for the treatment of disease, but “the most rewarding change I have had the honor of being a part of has been creating a culture of safety in an organization,” she said.

“Patients come to us trusting that we are going to do the right thing and keep them safe,” Susan stressed. “That’s a sacred obligation. Hospitals are a combination of different disciplines dealing with a wide range of diagnoses. There are a lot of opportunities for error.

Moreover, Susan saw to the replication throughout Connecticut of the systems and culture she helped put in place at St. Vincent’s.

In 2017, the Catholic Health Association recognized Susan with its Sister Concilia Moran Award and noted particularly her patient safety work.

In eight years at St. Vincent’s, she dramatically improved mortality rates by strengthening accountability for patient outcomes. Then, working with the Connecticut Hospital Association, she engaged all of the state’s hospitals in efforts to eliminate preventable patient harm. In doing so, she promoted disclosure of medical errors to patients and the public and helped bring about the passage in 2010 of a state law that required expanded public disclosure of medical errors by hospitals and clinics.

“That effort had nothing to do with competition between providers,” Davis said. “It was about doing the right thing for our patients.” (There’s that theme again.)

Susan speaks freely and frankly about her own battles with health issues.

She was newly arrived at St. Vincent’s when she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Twelve years later, she underwent a regular screening mammography that concerned her radiologist.

At this writing, Susan has been cancer-free for almost twoand-a-half years. That is an achievement she attributes largely to staying positive. And, she has been buoyed by the love and support of her husband and “life partner,” Richard Henley, her daughter Stacie and her four grandchildren.

“Never lose hope. I told many cancer patients that and then

I had to say it to myself,” Susan said. “Hope is critical to your survival. Henry Ford once said that whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you are probably right. You always have to think you can. That’s a powerful mindset.”

These days, she continues to work to encourage contributions to The Studer Family Children’s Hospital project at Sacred Heart.

It was Susan’s husband, a private equity consultant, who turned to her and said, “If this project is something we believe in, we need to step up.”

They did so, with a contribution of $1 million.

“This gift is a reflection of our commitment to improving the quality of life of children as well as our commitment to Sacred Heart. I feel very fortunate to have spent 14 years working for two exceptional faith-based organizations and staff who are dedicated to making a difference,” Susan said.