UNKNOWN

Dear Reader,

Letter from the Editors

Things aren’t good.

We could pretend they are. We could mirror the sentiment of rejuvenation peddled by the same government that got us here in the first place. We could create a summer issue complete with bright colours, sickly optimism, and a cry for collective cheer. However, it seems a big ask for a group of disillusioned students in their 20-somethings nigh on graduating into an unrecognisable world that has transitioned into a dystopian hellscape. Besides, we already did that (see spring issue).

In this vein, UNKNOWN concerns itself primarily with paranoia. Not so much with a tangible threat, or a clear hurdle to be overcome, but with the inescapable, all-encompassing dread that is symptomatic of our uncertain future. With this future-focus, we explore our increasingly digital existences, and the dangers that arise from this shift. UNKNOWN investigates the little cultural riptides that pull us down further into our own personal fears: the warranted and yet socially-invalidated apprehension of online dating; the anxiety induced by life within a privately-operated surveillance state; and the unpredictable consequences of gene-editing technology.

Reckoning with the aftermath of Covid, and the subsequent international governmental and cultural disintegration, serves as a reminder of the extent to which unchecked and undeserved influence has infected our society. Fear and mistrust have woven themselves deeper into the social fabric of our culture. As we hurtle back into so-called normality, we find ourselves thrust, unprepared, into a frenzied, disordered world, and towards a future that is as undesirable as it is unnerving.

All of this isn’t to say that UNKNOWN is devoid of hope. It is through the interrogation of the fucked up state of things that will enable us to approach this unpredictable future with the wool wrestled from our eyes, armed to deal with whatever comes our way.

Hence, the radical, opinionated, and intelligent minds that have filled these pages over the last 9 months are reason to remain hopeful. The future is bleak. The future is not coherent. And it is certainly not back under our control, as if it ever was. But for every Jeff Bezos clone inflicting unprecedented damage on our society, there’s a young creative with a laptop who’s sure as hell going to make sure you know how much of a prick they are. UNKNOWN is not doomsaying, but a necessary warning. It’s a guide for how we may still correct our path, communicated directly from the very individuals who will be living with the consequences.

We hate to make this all about us, but UNKNOWN is also the final issue created by the 20/21 GUM team. Leading GUM through the last academic year has been a beautiful, stressful, life-changing experience. 3 quarterly issues, the launch of a secondary publication, podcast, and art exhibition later, working with so many artists and writers from Glasgow and beyond has been a dream. We set out this year to make the voice of GUM louder than ever, and we’re walking away considering this goal achieved, all thanks to our incredible team, contributors, and readers.

We hope you have a great summer, and GUM will be back this winter. Bye from all of us for now, and thank you.

Don’t let the bastards get you down!!!!!

With love,

I. FEATURES

BORED IN DYSTOPIA by Grace Stanley PARANOID IN LOVE by Kate Fryer

II. CULTURE

THIS LITTLE PIGGY WENT TO THE ATM by Cain Mckendry NOT WITH A BANG, BUT WITH A BUNKER by John Tinneny

III. ART & PHOTOGRAPHY

SELECTED WORKS by Filipa Semedo FUTURE? UNCERTAIN by Magdalena Kosut

IV. POLITICS

TERRORISM ON OUR TERMS by Ella Field WHO GIVES A SHIT? by Grace Graham-Taylor

Dystopia noun

an imagined state or society in which there is great suffering or injustice, typically one that is totalitarian or post-apocalyptic.

Dystopia flooded our bookshelves and our screens for the recent golden-era of young adult fiction, right as Gen Z were entering their teenage years. Sagas like TheHungerGames, Divergent, The Maze Runner and countless others were published and subsequently filmed in our formative years. For some, they became fundamental markers of young adulthood, influencing the development of our worldview in the process.

Dystopian fiction often positions itself as some kind of warning for the future, an insight into what could be in store if we don’t change our ways. Often featuring widespread poverty, mass oppression, and heavily policed states, the political commentary woven into dystopian novels is typically thinly veiled. YA dystopian fiction often features a single hero - some 16-year-old caught in a love triangle - who gains a consciousness of the great wrongdoings in their world, and embarks on a journey to change society and save their loved ones.

Of course, dystopian fiction is nothing new, and these teenage-led dystopian novels were far from revolutionary. This current trend of dystopian fiction can be traced through generations from Zamyatin’s We, Huxley’s Brave New World, Orwell’s 1984, and Golding’s Lord of the Flies right up to now. However, these classic dystopian novels less frequently center teenage characters, and rarely have the reasonably ‘happy’ ending we’ve grown accustomed to.

Pessimism surrounding the political landscape, the economy, and the environment has surrounded us for as long as we, as a generation, can remember. Dread surrounding our uncertain future has long defined our present. Despite the space these conversations take up in popular conversation, solutions are rarely offered. Whilst real world politicians are often devoted to invalidating concerns about impending catastrophe, the writers of YA dystopian fiction that many of us grew up on - through their allegorisation of real world humanitarian disasters - were at least attempting to reckon with our precarious social framework and unstable future. Dystopian fiction as we knew it was filled with young revolutionaries rebelling against the system and taking down authority. It confirmed for many of us the nagging suspicion that adult institutions and their concentrated power were built upon corruption. It allowed us to entertain the idea that we could be a Katniss and save not only ourselves, but - hopefully - some of our loved ones too.

But, nowadays, we’re becoming increasingly aware of great suffering, injustice, and the totalitarianism which many live within. In 2015, academic and cultural theorist Mark Fisher coined the term ‘Bored Dystopia’ to describe how late stage capitalism is designed to make us believe in its necessity - despite its glaring flaws - and subsequently began to chronicle its progression in a Facebook group. A ‘Bored Dystopia’ describes how ‘Advanced Capitalist Society is not only dystopian, but also incredibly boring’. Essentially, the world today is becoming even more hideous and gruesome, but doing so without a bang and more of a dull murmur. This ‘Bored Dystopia’ that we are living in displays all the characteristics of a classic novel - only without the aliens, the revolution, and the romance. We simply don’t need to imagine or read about a world steeped in corruption when the reality of life today isn’t far from it. We do not need poetic political statements about what we should’ve done at some stage before most of us could even talk. We need real life change and real life solutionsand unfortunately for us, Tinder will not provide some toxic love triangle to help us get through it.

The desire to embody the dystopian hero we once adored has left many a Gen Z with a glaring saviour complex, and a belief that they can fix anything and anyone - even when it is clear some things are beyond repair. Except, outwith dystopian narratives, saviour complexes typically come from those with plenty of privilege, namely middle class white people who believe their efforts are charitable. Whether it’s a gap year ‘volunteering’ abroad, fundraised teenage-led

BORED IN DYSTOPIA 5

building projects, or TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) qualifications, we now collectively understand that whilst these experiences may seem to be good natured acts, they are, at heart, self-serving, opportunistic ventures that only further neo-colonialism in the name of CV-building. This glorification of certain groups or individuals is seen within the dystopian narratives we consumed as adolescents. Katniss became the face of her revolution: whilst in our early years we may have idealised this, in reality, she was somewhat unwilling to take on this role and - in all honesty - was kind of a shit leader who didn’t care about all the injustice half as much as, say, Johanna or Rue. This glorified heroism of a fallible leader has now spilled into our contemporary activism. Centering individuals within movements is something that, while widely criticized, is still happening. Recently, Patsy Stevenson became the poster-girl for the Sarah Everard case, a media driven move which contributed to counterproductive conversations. We can’t continue to criticise this behaviour in our everyday whilst dignifying it in our literature. Our developing understanding of this truth is seeing us move away from these narratives themselves.

When we look back, deeper, at the fiction we all enjoyed the glaring horrors are even more clear. Poverty, prejudice, and pandemics were all commonly romanticised in dystopian novels. These tropes are significantly less romantic when, as an adult, you realise it’s not merely fiction. The contemporary glorification of such figures is testament to the fact that dystopian fiction - ever present - is now failing to act as a warning. We now know warnings don’t work- somehow we still ended up here. Here, in a world that is still rife with conflict, prejudice, and hatred. In a world where too many have too little and too little have too much. Literature and film are supposed to be a form of escapism, a short venture from our lives into someone else’s story - something different and something unknown. Dystopias just aren’t cutting it anymore.

The Hunger Games’s President Snow said it himself: “Hope, it is the only thing stronger than fear”. These stories are no longer giving us the hope we need. Rather, we are perpetually in fear.

So why instead aren’t we looking toward depictions of utopia? Jill Lepore of the New Yorker described the difference succinctly: ‘A utopia is a paradise; a dystopia is a paradise lost.’ Instead of seeking out idealistic depictions of life as it could be we are enamored with mundane and uneventful retellings of our lives right now. Sally Rooney’s Normal People had us all wrapped up in the somewhat uneventful story of Marianne and Connell - and his acclaimed chain. The novel and following TV adaptation did exactly what it said on the tin: told the story of really very normal people. It’s indicative of a discreet, yet widespread cultural shift. We want a respite from the incessant reports of the world’s conflict - even if just for an hour or two. Our definition of utopia is different; we’re craving the insignificant and boring details of life we once took for granted.

Every generation is told by the last that they’re lucky to live in the time they do. We’ve all heard it, ‘In my day we didn’t have...’. The world we are (were?) living in was maybe utopia for some, but most certainly not for everyone.For our generation a utopia could be simple, - less of an idyllic Garden of Eden and more just having a garden. Less of eating everything and more of just eating enough. And, in reality, utopias just don’t exist. From Greek, ou-topos, meaning ‘nowhere’, the idea of utopia itself is as out of reach as some dystopian fiction once seemed, and out of reach isn’t enough to give us hope. Could we, from a Bored Dystopia, strive for a Bored Utopia? Probably not.

Gen Z took refuge in fictional dystopias to distance ourselves from the oncoming dystopian reality. Now that we’re in said dystopia, that bit older and wiser, we don’t need - or want - them anymore.

WORDS

Fryer

paranoidparanoid paranoidparanoid in love in love in love in love

CW: mentions of violence, sexual violence, violence against children, kidnapping, stalking, emotional abuse

We’re a paranoid generation. We’ve grown up with stories of stranger danger, conspiracy theories, and the FBI carefully listening to private convos through our iPhones. Paranoia can be a diagnosed mental illness, but it can also be understood as either a deep anxiety that someone or something will harm us, or simply a level of concern that is labeled, by others, as irregular, be that in content or degree. In the context of dating, let us understand paranoia, here, as a conflation of both anxiety and this allegedly irregular concern.

Growing up against the backdrop of the Madeline McCann case and the omnipresent ‘man in a white van’, we have grown accustomed to the fear of falling victim to violence - be it physical, sexual, or verbal. Yet, most of us would have also found ourselves on Omegle at a sleepover, aged 12, in those anxiety ridden days when we were just learning how to do winged eyeliner and watching Skins for the first time. We didn’t want to admit it, but the whole experience really just affirmed what our parents were saying. There are people out there, hard to identify often until it’s too late, who are very much willing to take advantage of any vulnerability. It is this combination of adults incessantly instilling fear in us and being flashed by creeps through our pals’ cracked iPad screens that has seen some of us develop mixed feelings when it comes to dating. A paranoia, if you will.

The fear of ‘stranger danger’ and dating intersect at one of the cornerstones of contemporary society – online dating. For our first 17 years and 364 days it’s drilled into us to never talk to anyone you don’t know online - don’t post your name, your location, or even your age, lest you find yourself attacked, kidnapped, murdered. But the minute the clock strikes midnight on your 18th birthday, it’s a free-for-all on Tinder. With dating apps (Tinder, Hinge, Bumble – pick your poison) so normalised - downloaded halfway through whatever budget wine you’re drinking - it’s pretty easy for any concerns to be brushed off as ‘paranoia’. Regardless, I know that the idea of it awakens the fear in me, hence why I’ve never had Tinder for more than one day. I know that the chances of Glasgow University’s answer to Joe Goldberg stalking me is pretty improbable. But a long-ingrained mistrust of the internet coupled with an awareness of the prevalence of violence and assault in the dating world are enough to stop me in my tracks - and I know I’m not the only one. This obviously has its knock-on effects in the realm of my love life, especially whilst we’re in a state where there aren’t plentiful real life opportunities to meet new people.

A general paranoia regarding safety seems to permeate through all aspects of dating – regardless of whether or not strangers and dating apps are involved

A general paranoia regarding safety seems to permeate through all aspects of dating – regardless of whether or not strangers and dating apps are involved

A general paranoia regarding safety seems to permeate through all aspects of dating – regardless of whether or not strangers and dating apps are involved

A general paranoia regarding safety seems to permeate through all aspects of dating – regardless of whether or not strangers and dating apps are involved. The speculation as to possible outcomes of a date turning sour (to put it lightly) can affect every ounce of behaviour before, during and after a date. The age-old question of ‘what was she wearing?’ can cause many an outfit change, just in case we need to be able to defend ourselves with our clothing choices. This concern of possible victim-blaming also poses a major issue when it comes to the classic pub date. The potential of being taken advantage of in a drunken state, and the events that may follow, will have some pointing blame to me, to us, rather than the only one responsible – the one taking advantage. This fear doesn’t really cooperate with the desire to have a pint of cider in hand for liquid courage.

This leads us onto a different variety of paranoia, one harder to justify to pals or back up with statistics and horror stories. It isn’t embroiled with the distrust of people and society, but rather distrust in oneself. We never say the right thing. It’s always too much or too little. Too pretentious or too boring. Did it look like you were trying to show off? Or like you’re the dullest person around? This ability to find fault in whatever we may say of course often manifests itself in saying nothing. Whilst some may swear by ‘playing hard to get’, not communicating at all doesn’t lead to desired results. Nonetheless, what is one to do? When

the very idea of sparking up conversation with someone makes you feel sick to your stomach with dread, the only reasonable option is to say nothing, go home and agonise over how much of a weirdo you must look for doing so –it makes for a fun evening. What’s more, as someone who made the rookie error of mistaking friendship crushes for actual crushes in high school, concerns can also arise when I start to like someone. Do I actually fancy them or do I just think they’re sound? Am I just bored in a pandemic, wanting something to focus on that isn’t a uni deadline? The desire to avoid committing such a blunder leads to – you guessed it – paranoia whenever a potential crush rears its head.

But emotion-based paranoia isn’t solely restricted to the self - it comes out in relationships as well. Are they lying? Cheating? Am I overreacting to comments they’ve made? Of course, being told repeatedly that you’re ‘ridiculous’, ‘upsetting them’ or just plain ‘paranoid’ leads to a questioning of your own feelings. We’re gaslighted. The paranoia is further instilled within us - we’re paranoid about being paranoid. And paranoia isn’t hot right now. No one wants to date - or be - someone in a tin foil hat, and the ‘crazy girlfriend’ stereotype plays into exactly that collective consensus.

The thing is, none of this is really paranoia. Our so-called paranoias are very much rooted in reality. The reality is that, unfortunately, there is always a potential risk - whether that’s in regards to love, or, on the more serious side of the spectrum, to personal safety. The fact is that our distrust in ourselves and concern over how others perceive us is rooted in our past experiences: these feelings are perfectly natural, even if highly frustrating at times.

The paranoia is further instilled within uswe’re paranoid about being paranoid. And paranoia isn’t hot right now. No one wants to date - or be - someone in a tin foil hat

The paranoia is further instilled within uswe’re paranoid about being paranoid. And paranoia isn’t hot right now. No one wants to date - or be - someone in a tin foil hat

The paranoia is further instilled within uswe’re paranoid about being paranoid. And paranoia isn’t hot right now. No one wants to date - or be - someone in a tin foil hat

Inevitably, we may all run the risk of cockblocking ourselves into oblivion with our so-called paranoias. We may transform any potential match into a disaster in our heads. But let’s not get angry with that ‘lil inner voice for trying to protect us. It’s worth acknowledging your inner paranoia and saying to yourself: ‘thanks for the concern, love, but I’m alright. I trust and like what I’m doing’. When it comes to safety, let’s be careful to label these concerns as paranoia. This heightened awareness is rooted in past experiences - and it can come out on anything from a chill date to a hook-up that’s admittedly got really quite creepy vibes. Is it better to be paranoid or heartbroken? It’s a bit of a toss up. Is it better to be paranoid or dead? Para, please.

This Little

CW: discussions of addiction

‘You deserve it’, whispers a young woman, clad in latex. She spits into the camera and stops recording. Posted to Twitter by a user named ‘Goddess Ivy’, the video, only 8 seconds long, is accompanied by the caption: ‘POV after I’ve maxed all your credit cards, leaving you with crippling debt’. In small communities across Twitter, Tumblr, and other forums further afield, men pay for insults like these, and goddesses like Ivy have their worshippers: paypigs.

In the realm of BDSM, relationships between goddesses and their pigs fall under the category of financial domination, or findom. Findom relationships consist mostly of dominant women (or dommes), known variously as Queens, Goddesses and Mistresses, and submissive men, paypigs, who derive sexual pleasure from lavishing their goddesses with money and gifts, sometimes in return for nothing but often for humiliation. For those outside of the community, humiliation, relinquishing financial control, and being ‘drained’ of money might seem strange, but for those within findom, such transactions form the basis of what is often a highly intimate relationship between sub and dom.

Similar to real pigs, of which there are hundreds of breeds ranging from mini to domestic or wild boars, there are also dozens of types of paypigs. Some pigs pay to participate in other people’s relationships, and to watch or be degraded for watching their partner have sex. Some are entirely dedicated to worshipping feet (real and photographed). Others even wish to be knowingly drained by catfish dommes, two of whom I encountered impersonating Emily Ratajkowski and Kylie Jenner. And, banal as it might seem, there are even ‘spoons’ pigs: paypigs who get pleasure from paying for food, drinks and tables at Wetherspoons.

if the pandemic has been far from financially-friendly for the best of us, it can’t have been any easier for those who need to send and spend cash to cum

The fetish’s highly virtual nature makes its participants relatively easy to find. A search using the right terms on Twitter results in countless whip-yielding, leatherwearing goddesses, all demanding that their paypigs pay ‘the small dick tax’ (yes, that’s a thing), reimburse their various purchases, or double and triple ‘measly’ sums of money exhibited in PayPal screenshots. Beneath each post is a myriad of paypigs – some already owned by dommes, some independent – who often have as their Twitter icons some variation of a small cartoon pig (one of which I recognised from the Disney cartoon, Gravity Falls). These cute icons are often contrasted against their explicit bios, some of which read: ‘loser… female supremacy…’, ‘addicted to sending to hot bratty girls’, and ‘please take my chastity keys’ (referring to the keys of a chastity cage locked around their penis).

Yet, alongside the more light-hearted pigs, there is a darker side to the fetish. Certain paypigs derive their sexual gratification from being blackmailed and are turned on by the threat of having their real lives ruined. The Twitter bio of one domme named ‘Blackmail Mistress’ reads: ‘I will blackmail you, seduce you, homewreck you, humiliate your wife and you will thank me’. While for some pigs, this fear can be sexually exhilarating, for most others their ‘real life’ relationships are often the reason for keeping their fetish a secret, a habit buried in the underside of their daily lives about which they have nobody to confide in but other internet users.

One former domme who I spoke to, named Sarah, similarly tells me that ‘paypigs are secretive’. A fellow student in her 20s, Sarah no longer takes part in findom for the fear that it will ‘affect [her] future employability’. Another deciding factor for her stems from the impact of the pandemic on the community. While for Sarah, some paypigs would ‘pay more because they were spending more time at home’, the majority ‘just kind of stopped paying’ either because ‘they would be at home with their wives/partners’, or simply because they could no longer afford their fetish. Chatting with Sarah raises the valid concern that if the pandemic has been far from financially-friendly for the best of us, it can’t have been any easier for those who need to send and spend cash to cum.

WORDS

Cain Mckendry (he/him)

ART

Ella Ottersbach-Edwards (she/her)

Piggy WE ATM NT TO THE

For one former pig I spoke to, the pandemic has been a time of reflection. Alex, who describes himself as a ‘recovering findom addict’, tells me how the pandemic unearthed the fetish’s more problematic aspects for him, such as the slippery slope it offers ‘into the black hole of debt and misery’. Due to findom, Alex is over ‘£30,000 in debt on a £1600 a month salary’. While I have no way of verifying his story, he also has no reason to lie to me. Before the pandemic, Alex would pay women ‘£150 an hour’ to physically dominate him, an ‘incredibly manageable’ sum, but the transition to virtual paypigging was the final straw: ‘the click of a button can have a catastrophic, life changing effect’. Shortly after speaking to Alex, he returned to findom. In his own words, ‘findom ruins lives and the weirdest thing is THAT is the turn on’.

Alex’s account is not an isolated one, but is part of a growing number of current and former paypigs who label findom as an ‘addiction’. Given the unique intersection of financial and sexual power dynamics within the community, it is difficult to know when enough is enough, and when enjoyment turns to addiction. For various reasons, findom addiction is hard to spot, and even harder to treat. Like other ‘virtual’ addictions such as to pornography, findom addiction is not taken seriously and, as a result, is seriously understudied. Added to this, the shame that often accompanies the fetish makes it difficult for those who might be struggling to speak up and seek help.

Yet while findom can feel like a sticky web for those who are trapped in it, accounts like these are for the most part still the minority. For the majority of goddesses and their pigs, healthy boundaries and proper consent has created safe spaces tucked in the corners of the internet where both can freely express the highly intimate and highly misunderstood sexual practice of findom. During the pandemic, the collective increase in screen-times has led to the inevitable increase in non-BDSM users stumbling into these spaces. For some of us, this new spotlight on the fetish has meant cracking open our piggy banks for the very first time; for others, filling them up. For the rest of us, though, more needs to be done before people like Alex feel comfortable discussing findom and before it is accepted as a healthy, if obscure, installment in our bedrooms and webrooms.

Not with a bang, but with a bunker

I’ll admit that before writing this article, my idea of your standard ‘prepper’ was one that resembled the usual stereotypes: camoclad men living in the woods with hunting guns; people huddled in bunkers designed for the impending nuclear holocaust; or those preparing for the coming rapture, clothes crumpling to the ground as they ascend into heaven. But over the course of my own survey through the interviews and articles produced about preppers, it became clear how their worldview, if not wildly popular, seems to strike a distinct chord these days. In an era defined by unexpected upheavals and catastrophes, the idea of preparing yourself for impending disaster isn’t the pessimistic doomsaying it once seemed. Indeed, though there are more extreme ends of it, mild forms of prepperism seem increasingly like a reassuring and responsible precaution - a way of reasserting some limited form of agency in the face of an uncertain future.

In an era defined by unexpected upheavals and catastrophes, the idea of preparing yourself for impending disaster isn’t the pessimistic doomsaying it once seemed

Appearing under its current usage in the latter half of the 20th century, prepping was originally associated with those who, fearing nuclear annihilation during the cold war, prepared themselves through the construction of bunkers and the accumulation of food supplies, amongst other things. It also has a specific significance for religions which foretell rapture-like events, like the Church of the Latter Day Saints, who as it turns out, have a network of silos and food stores as their own form of preparation - a fact which is as unexpected as it is faintly impressive in terms of sheer infrastructure. Prepping can cover a wide range of practices, from assembling a ‘go-bag’ for a quick exit to constructing ‘bug-outs’. These are locations of refuge, designed to be fled to in the face of imagined unrest, which, according to my findings, can take the form of anything from a caravan to a fortress with bulletproof windows.

One could argue this prepper mindset resonates with some cultures more than others. In the US, for example, prepping chimes with a historic frontier mindset which values individual resilience, which mightn’t map as easily in a UK context. But even with that said, one can find more and more examples of preppers not just within Britain, but around the globe, with this lifestyle centred on sometimes isolated individuals turning into what you could dare to call a community. There’s even a website aptly called ‘The Prepared’, and within this online community, one finds an unexpected range of diversity, moving away from the idea of eccentric nuclear doomsayers and devout Christian sects. The community hosts people from both rural and urban areas, with an even gender split, and the demographic is fairly young too, thus suggesting that prepping is not simply a hangover from the cold war, but instead carries its own modern relevance.

One possible explanation as to why prepping has acquired a new, broader appeal is the increasing discussion around and experience of catastrophe, particularly in response to a climate crisis and mutating global virus. In the wake of wildfires in Australia and California, to name just two in a long and ever-growing list, the act of prepping can be seen as one of the few steps the individual can take to reassert agency. The preppers subculture is symptomatic of a deeper cultural belief: the idea that, when everything goes to shit, when the ‘big one’ hits, there won’t be much our elected officials will be able to do about it. We’re on our own. The participation in prepperism, the ridiculing or writing off such practices as fantastical, as ludicrous, are all rooted in the same fear. The fear of unconstrained, uncontrollable societal collapse.

WORDS John Tinneny (he/him)

ART

Ella Ottersbach-Edwards (she/her)

There’s certainly an undeniable comfort to be found in prepping, especially if we consider the reckless behaviour of larger organisations in their acceleration of climate catastrophe - one of the frontrunners in the race to start the apocalypse. The UK government, for example, try to position themselves as ‘climate leaders’ even as they approve (and, in a partial u-turn, are forced to open a public enquiry into) the opening of a new coal mine. The oil company Shell is audacious enough to ask their Twitter followers what they’re prepared to do to save the environment (showing that oil capitalists have brass necks as another source of mineral wealth at least). In the face of this, prepping may be one of the few genuine ways to assert some kind of control, even if it is deciding what canned food you’ll be eating for the first few weeks of a new world (dis) order.

The preppers subculture is symptomatic of a deeper cultural belief: the idea that, when everything goes to shit, when the ‘big one’ hits, there won’t be much our elected officials will be able to do about it

Prepping, of course, has its limitations; you can store all these cans in case supply chains fail, but if the world has truly collapsed, there’ll come a time when you will need to leave the bunker, and seek more resources or help. But aside from these minor practical issues, the overarching practicality of all but the most extreme forms of prepping is hard to deny. If the Covid pandemic has shown us one thing, it’s that we can truly be blindsided by unexpected events, and as many preppers found watching most of us panic buy toilet paper like amateurs, it can pay off to prepare. And so, though you might not disappear into the woods like Bear Grylls, small things like go-bags may become more incorporated into our lives in the coming years. The thought seems strange, but then again so did face masks. The only difference is that we adapted to those after the necessity became clear. Maybe in the future, we’ll be taking these measures early, looking ahead more to what’s to come.

Filipa Semedo

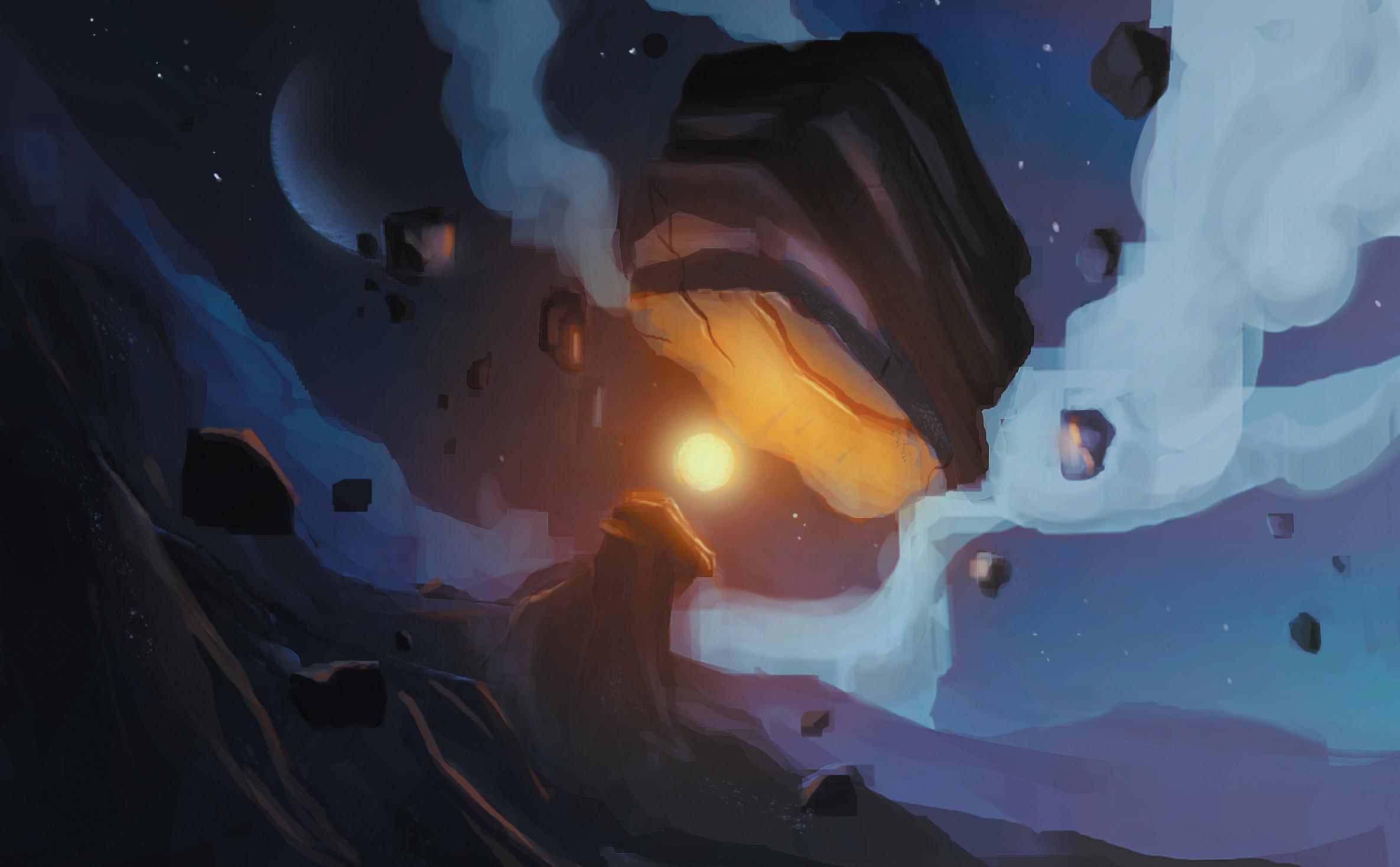

I’ve always had a fascination with time travel and the multiverse theory and so my art, more than being just a way to express myself, is a vehicle that allows me to explore the unknown, both its scary and exciting possibilities. I paint to travel through scenarios that never came to be or scenarios that may still come true. I paint to visit places, times, and people that are pure fiction and never to exist, or to experiment with what could one day be our reality. When I imagine these scenarios I’m mainly influenced by the cyberpunk and solarpunk genres. The first is a hopeful sort of unknown, but it also brings out the cynic in me, which is why I created these creatures that I keep going back to who are humans merged with nature. I like to explore how their minds might work, which is just a more intimate type of unknown. With the latter, some things feel so close to what I already know that I get this paradoxical sense of nostalgia. But the unknown is still present, it’s there in the search for alternatives to capitalism and in the promise of what’s to come. Maybe a solarpunk world?

Magdalena Kosut

Through this piece, called ‘FUTURE? UNCERTAIN’ , I wanted to explore the instability of these recent times, as well as our equally precarious future - a time period juxtaposed with multiple radical opinions and movements, and intense feelings. Throughout the process of making this piece, I was also thinking a lot about how our focus is constantly shifting. We hear about tragic events and monumental historical moments happening far away from us the instant they take place. We’re immersed in 24/7 world news and a constant flow of information, causing us to reflect heavily on our own experiences and our community closer to home. Sometimes this can leave us feeling confused, guilty, and stretched too thin. This piece is about how maintaining hope may be harder than ever, but also more important than ever.

TERRORISM ON OUR TERMS

CW: discussion of terrorism, violence

In 1878 Russian socialist revolutionary Vera Zasulich stood before a court in St Petersburg on trial for shooting Fedor Trepov, the city’s governor. When asked why she had only wounded but not murdered him, she famously responded, ‘I am a terrorist, not a murderer!’ . For this, she received applause from the trial’s audience and, with the help of an excellent lawyer, was acquitted of her crime.

Ella Field (she/her)

WORDS

This adulation and acquittal is a far cry from the response we’d expect to a declaration of terrorism today. In recent decades the image of terrorism and terrorists carefully crafted by governments, mainstream media and certain terrorist organisations, have served to make those branded as terrorists some of the most despised and feared people in society. In deep contrast to an applause, a terrorist in 2021 would be feared, fled from, and incarcerated - not to mention all the institutionallyinduced presumptions the average onlooker would have about that individual’s character, colour and religion. Even the words ‘self-declared terrorist’ feel like an oxymoron. Today to be a ‘terrorist’ is more of a societal condemnation than a label one would choose to proudly identify with. So what changed? When and how did terrorism fall from the grace of a political act to enact change and come to connote all the dirty, divisive and murderous things it does today?

If the state controls the meaning of terrorism, they likewise control what, and whom, society fears most

It would be easy to dismiss the change in perception of terrorism by using Noam Chomsky’s cliché and overused quote that ‘one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter’. This sentiment would ascribe the difference in reception to Vera versus Al Qaeda as simply the bias implicit in the individual defining the political violence. Yet whilst it is undeniable that Zasulich’s famous line would not have received applause with a politically opposed audience, the crucial point is not the reaction, but the fact that she was both a terrorist and freedom fighter without contention.

Whilst the contents of Chomsky’s quote do not get us any closer to understanding how the meaning of terrorism has changed from its beginnings in anarchism and the French Revolution, it does alight on a significant problem in understanding terrorism - its complete lack of definition and the sheer ambiguity created as a result. Due to its complexity, subjectivity and contentiousness, terrorism is notoriously difficult to define. This has led to the kind of vagueness and subjectivity we see in ‘one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter’ and has resulted in some scholars even arguing that the only globally workable definition of terrorism is simply ‘violence I don’t support’. Scholar and head of UN Terror prevention branch Alex Schmid analysed the myriad definitions of terrorism and found that while over 80% of definitions included violence, only 65% contained a political element and only 51% included a fear of terror. Whilst it is true that any definition of terrorism is going to reflect the bias of the definer, the foggy no man’s land created by no definition leaves space for terrorists and governments alike to repeatedly redefine terrorism according to their own agendas.

Due to this subjectivity, terrorism cannot be considered as an entity in itself, but a lens through which strategically chosen violence is viewed. Our society is one in which use of violence as a means to power is inescapable - from individual actors to mafias to states. The ability to normatively frame this violence for public perception carries a lot of power. States function by monopolising this violence legally, financially and militarily in order to control populations and exert hard or soft power as far as possible. When states function well, this monopoly on violence is condoned and legitimised by a population who accepts the control the state has as generally beneficial. A state’s legitimacy, however, is chronically fragile due to its reliance on being believed in by the people.

By nature, a state is desperate to vindicate its monopoly on violence, terror and ideology, and determined to demonise those who threaten it - such as terrorists. A great way of achieving this is to control the meaning of the word terrorism, as global superpowers in the West do.

Since the term terrorism’s conception in the French Revolution we have seen nation states and the monopoly on violence they command become further entrenched. The very concept of a nation state has been exported across the globe, and with it the formation of an interconnected, globalised and highly militarised world Bonaparte could hardly have dreamt of. As the West has stretched its terror and ideological tendrils across the world in order to sustain global capitalism, it has become more fragile, its legitimacy now reliant on the support of not just one populace but the entire world. With this increased fragility, it is no wonder that the word terrorism has lost its political meaning - the states reporting terrorist acts do not wish to legitimise, or even acknowledge, the opposing political goals of those committing violence out of fear of losing their teetering legitimacy. They instead paint a picture of certain terrorists as crazed, inhuman barbarians, using Julius Caesar’s societally endemic maxim of divide and conquer to create a barbaric ‘other’ and a righteous ‘norm’. It is because of this that far fewer murderous white supremacists have been labelled terrorists than people of colour who commit similar acts. Terrorism, as opposed to anything that quantifies terror or political motivation, has become a tool of the state to condemn those who threaten its legitimacy. Since white supremacists who commit acts of terror do not structurally challenge our racist post-colonial society, their acts of violence are rarely deemed terrorism in mainstream discourse. In this sense, what government or popular media deems terrorism can be understood as a manipulation of the emotionally-charged term. If the state controls the meaning of terrorism, they likewise control what, and whom, society fears most.

By nature, a state is desperate to vindicate its monopoly on violence, terror and ideology, and determined to demonise those who threaten it - such as terrorists

Terrorism as a definition-less, emotional and divisive term owned by those creating the narrative serves only to create division and uphold existing hierarchies that benefit the elite. This leaves us with two options - abolition or reconception. To abolish the word terrorism from discourse feels like a pretty tall order, albeit one I would support given its uselessness at delineating anything meaningful and its usefulness at inciting fear, hate and anger. However, reconception of the term and what it means to us, is very much within our remit as the people. If we change our own definition of terrorism to include violent political acts from anti-fascist rioters, Nelson Mandela and Vera Zasulich, to mass school shootings, state air strikes and ISIL, terrorism loses its current meaning and power. By acknowledging all political acts of violence as terrorism, we take the narration on terrorism away from elites and into our own hands, allowing us to analyse the morals and motivations for violent acts with rationality instead of prejudice.

Poe’s Law is an unofficial law of the internet which essentially states that, without marking one’s statement online as sarcastic or false, there is no way that it can be properly distinguished from true statements, or those of trolls. The law is named after Nathaniel Poe, a contributor to the Christian message board ‘christianforum.com’, who took part in a discussion on creationism in 2005. After some members of the discussion expressed the worry that they were being trolled, Poe musingly commented that, ‘Without a winking smiley or other blatant display of humour, it is utterly impossible to parody a Creationist in such a way that someone won’t mistake it for the genuine article’. In other words, on the internet, it is impossible to distinguish fake stupid from real stupid.

The question then becomes, do we take everything seriously, or nothing at all?

Shitposting is an irony-drenched brand of internet humour which usually involves a user, or troll, responding to something posted online with something entirely unrelated (often a meme) to derail the conversation. Since its conception, this seemingly harmless humour has become a weapon of the alt-right. Under the guise of ‘lulz’, real political agendas are being disrupted, and it’s getting harder and harder to tell who’s in on the joke. QAnon, the latest half-baked conspiracy-turned-ideology to escape from the confines of the internet, a theory which claims Satan worshippers run the government and plotted against Donald Trump, has now become a legitimate political force. It seems like the line between satire and reality has officially collapsed, and we have to live with the consequences.

That said, shitposting isn’t always bad. It’s ubiquitous on the internet, and most of it is innocuous and benign. Sometimes the joke can get out of hand, such as the ‘Storm Area 51’ debacle of 2017, but, ultimately, the goal is to entertain. The word itself is hard to define, primarily because it’s a self-descriptor, but journalist Jessica Lindsay aptly describes it as: ‘nothing of value. It is the online equivalent of shooting tin cans with a spud gun in a patch of wasteland. It’s repeating what the person you’re with says in a stupid voice until they give up and go home’.

In the face of a bleak reality, shitposting seems like a natural response to how darkly ridiculous the world has become

However, shitposting can also be a subversive and meaningful way to express discontent with prestigious individuals, corporations and establishments, by making a mockery of their attempts at co-option. When Mountain Dew attempted to crowdsource a name for their new flavour of soda in 2017, they quickly found their website hijacked by shitposting trolls. In punishment for this, ahem, brandloyalty-building-campaign-posing-asdemocracy, frontrunning names ended up being ‘Diabeetus’ and ‘Moist Nugget’ (also, more disturbingly, and more in line with my previous alt-right observations, the name ‘Hitler did nothing wrong’).

Irony like this is why shitposting has been compared to the ethos of Dada. Emerging from a profound disgust with the world, Dadaists created absurd, disruptive works that reflected the alienation and madness of 1910s and ‘20s post-war Europe. As in the era of the Dadaists, within our own era, sentiments of confusion, alienation and disillusionment are rife towards traditional bodies of authority (such as politicians), the widespread commercialisation of culture, and skyrocketing income inequality in many advanced economies. Or as Nobel-peace prize winning economist Sir Angus Deaton puts it, ‘There is this feeling that contemporary capitalism is not working for everybody’.

In the face of a bleak reality, shitposting seems like a natural response to how darkly ridiculous the world has become. However, the absurdity of the world is in part informed by the absurdities of the internet: real life and digital life operate in a feedback loop, informing and reinforcing each other. By investing ourselves in an online culture of irony, we are ostensibly losing the ability to distinguish between what’s serious and what’s not in real life. Due to this, genuine bigotry can parade itself as comedy and the ambiguities of ironic humour can function as the alt-right’s mask for their extremist views. By burying their messages in memes and absurdist humour, white supremacists and far-right extremists have been able to spread their ideologies, and normalise otherwiseunthinkable behaviour, all while claiming it’s a joke.

Genuine bigotry can parade itself as comedy and the ambiguities of ironic humour can function as the alt-right’s mask for their extremist views

One example is the New Zealand Christchurch shooter, who opened fire on two mosques in 2019, killing 49 people. The shooter left behind a manifesto, replete with memes and insider references, which he posted on the infamous 4Chan board, /pol/ (politics), before the attack. The manifesto begins: ‘it’s time to stop shitposting and make a real life effort post’. All of this, it has been argued, was designed to distract and confuse mainstream journalists, whilst also forcing them to unintentionally ‘repost’ these memes in their coverage of the attack, sending a message to fellow extremists. As Matt Goerzen claims in ‘Notes Toward the Memes of Production’, the extreme right has seized the memes of production and is now utilising them to spread their message, radicalising more people in the process.

Where does this leave us, then, with regards to posting meaningless shit on the internet? It’s becoming increasingly obvious that shitposts – especially those perpetuated by the alt-right – can and do have serious political consequences. This is partly because, despite their inanity, shitposts do serve a meaningful expressive function: through ironic, exaggerated humour, emotional truths can emerge that would otherwise be too difficult to express straight. But, often, it’s ultimately the sentiment of the shitpost, and not its content, which resonates with people. The sheer amount of people drawn to the alt-right’s conspiracy theories is a stark reminder of the posttruth future we’re heading towards, or perhaps already living in.

The sheer amount of people drawn to the alt-right’s conspiracy theories is a stark reminder of the posttruth future we’re heading towards, or perhaps already living in

The alt-right sows the seeds of distrust in the media and the language of political elites by exploiting the pre-existing sentiment that these organisations are not working for the everyday individual, for you. After the seeds are sewn, the alt-right offers an alternative theory, one which validates this sentiment. Ultimately, this problem extends far beyond the internet, and will require a great deal of collective soul-searching to fix. Perhaps, just perhaps, a good place to start is with more open and honest communication.

WORDS

Grace Graham-Taylor (she/her)

TRIPLE X

Direction: Daniel Castro (he/him), Lara Delmage (she/her), Graham Peacock (he/him)

Photography: Samuel Mitchell (he/him)

Designer: Oliver FJ Jones Studio

Models: Latex (she/they), Jack Patton (they/them)

The editorial project for GUM’s summer issue is titled TRIPLE X The title refers to the censorship and erasure of queer bodies in the mainstream, and serves to make brazenly visible those who society would like to make unseen. In this vein, the UNKNOWN editorial photoshoot showcases the talents of queer, Glasgow based creatives which is manifested in a series of intense portraits. Fundamentally transgressive of established social norms, this project captures forms of self-expression which embrace the realm of divergent sexuality and gender. By platforming artists whose work and identities are at odds with entrenched yet outdated ideals, TRIPLE X is a reclamation of power by those who have long been condemned as outsiders.

Andru Musda Reza (she/her)

Watching me, watching you

CW: needles, COVID

In 2021 it is almost impossible to go unseen. Take the London Underground for example. Over 15,000 cameras inhabit the sprawling network. They roost above platforms, crane around corners, and nest in the thundering carriages of each train, capturing every moment of its commuters. Yet this omnipresence of surveillance isn’t restricted to what can be perceived by the public eye. Recent years have seen a rise in more discreet recording systems and privately-owned cameras - from businesses attempting to protect their stock, to security cameras implanted in doorbells.

That we now take for granted that the majority of our movements are recorded - sometimes without our awarenessis a suggestion that we may have become too accustomed to this surveillance state. From the minute we wake up in the morning we are monitored – whether it’s turning on our phone with our fingerprint, being listened to by our smart devices, or even doing a spot of online shopping, our data is being harvested 24 hours a day. And who is really to blame for our complacency? This is not a hostage situation - instead of being prescribed our telescreen or tracking chip by the government, we all headed to Amazon to buy them for ourselves.Through our acceptance of a modern world which insists technological advancement is the only way to ensure security and simplicity, we have bowed down to the systems that watch over us, adding fuel to a fire that shows no sign of diminishing.

all, social media. But this just struck me as absurd. The juiciest shots my CIA officer was going to get was of me sitting in my stained hoodie watching Netflix. Whether or not there was any weight to the WikiLeaks claims became besides the point. The fact that the government - or any other institution, company, or individual for that matter - could hack into our webcams, could watch us in our bedrooms, the most private and intimate settings of all, gripped our collective consciousness.

instead of being prescribed our telescreen or tracking chip by the government, we all headed to Amazon to buy them for ourselves

Of course, constant surveillance has its advantages –be it identifying criminals, tracking the whereabouts of missing people and even allowing us to monitor how long the library queue is (tip: if you can see it on the library camera, it’s not worth leaving your flat). One lasting side effect, however, is paranoia. Our adverts seem eerily tailored, Snapmaps tells our exact location within seconds and smart speakers pipe up at the slightest mention of a desired time. Our traceability leaves us vulnerable. The world feels so much smaller. Big cities have become tiny villages where privacy feels like a rarity.

And this paranoia goes even further. Beyond everyday concerns regarding personal confidentiality, a growing number of people fear that the government is trying to tap into our everyday lives. In 2017 massive controversy ensued when WikiLeaks claimed that the CIA had the ability to hack into webcams. The internet went mad. People began to fear they had their own designated CIA officer watching their every move. Quickly cameras were covered with stickers, precautions were made and society feared they were living in a total surveillance state against their own knowledge. To express their disgust they ironically turned to the place that harvests the most data on us

Even more recently came the conspiracies surrounding microchips being planted in the Coronavirus vaccine. The fact that the integrity of a vaccine that has the potential to end a pandemic and save countless lives is being questioned as a government ploy to monitor its citizens suggests just how far this paranoia has spiralled out of control. But it isn’t just a small group of society that believes this, A recent survey suggested 28% of Americans believed that Bill Gates had planned to carry out this massmicrochipping program. Of course, there was very little information to support these claims, and the likelihood is that the government or the man who made the Word Doc is not trying to microchip our brains. Even more ironically, much of the information spread about this conspiracy happened via Facebook, a platform that spreads fake news faster than any other social media platform, according to Forbes.

Despite the obvious inaccuracy of these claims, they are nonetheless a symptom of the paranoia that defines modern society. The rapid integration of surveillance systems into every aspect of our lives have left us wondering how much is too much. From the cookies stored on websites we visit, to police body cameras, to the recording device on our neighbour’s doorbell, it has become impossible not only to entirely comprehend how much of our personal movements are being recorded, but also who exactly has access to this information. For every benefit offered by this new technology comes an equally concerning drawback. The end result is a mistrust of our own concerns, an invalidation of warranted fear. As an incredibly lucrative and booming industry, a world in which we do away with the surveillance state is altogether inconceivable. A far more likely, imaginable future is one in which we rid ourselves of traditional surveillance technology only to instead become our own surveillance devices.

This leaves us with an uneasy conclusion: CCTV and surveillance appears to have become an unavoidable aspect of modern life. Both the ability and desire to go unseen are contemporary myths which appear impossible. Maybe the extent of the surveillance we are facing has become too great. However, the honest truth is: we might just have to deal with it.

Life hack

CW: discussions of chronic illnesses

A few decades ago, the prospect of altering our DNA seemed like science fiction. Now, not only is genome editing a reality, it has become a relatively simple and cost-effective process with the discovery of a revolutionary gene editing technology: CRISPRCas9. This powerful tool, which can edit the DNA of almost any organism, is already reshaping the future of research, agriculture and medicine. With this, the eradication of genetic disorders and global humanitarian crises such as world hunger appear conquerable. But the path to human gene editing is strewn with ethical dilemmas and social concerns. In a future where the human body can be deconstructed on a cellular level and reassembled in whatever fashion we deem most convenient, how far should we go when rewriting our genetic code?

The human genome is an instruction manual made up of over 3 billion letters. If the DNA in each of our cells were unpacked, it would be roughly 2 metres long – so the ability of CRISPR-Cas9 to target a precise location in the whole genome is unprecedented. CRISPR-Cas9 works like a pair of molecular scissors that cuts out a target DNA sequence, for instance a ‘faulty’ gene responsible for a specific disease can be snipped away and replaced with a ‘corrected’ version. It comes as no surprise that this revolutionary technology won Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, the women behind CRISPR-Cas9, the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Now that we hold the key to editing life’s instruction book, the applications are limitless. For instance, 1 in 25 children are born with a genetic disorder, which is passed on from generation to generation. Genetic diseases are caused by mutations in our DNA and can be extremely debilitating, even life-threatening. This includes chronic illnesses such as cystic fibrosis, and haemophilia, a bleeding disorder. CRISPR-Cas9 has the potential to cure genetic disorders like these by editing out the harmful mutations that cause them, treating the disease at its very root and subsequently eradicating them.

The applications of CRISPR extend well beyond the scope of medicine. With our global population expected to grow to almost 10 billion by 2050, we need to find ways to meet the increasing food demand without putting more pressure on our already strained planet and resources. Genetically engineered crops could be the solution by editing crops to become disease-resistant and climateresilient. CRISPR holds the potential to craft a future free from the eco-fascist myth of overpopulation. The nutritional value of certain staple foods is also being enhanced to counter malnutrition in developing countries. For instance Golden Rice, a genetically engineered rice with high levels of beta-carotene, which is converted to vitamin A in our bodies, has already been approved for consumption in several countries.

In 2018, a Chinese researcher claimed to have edited the DNA of two human embryos to reduce their risk of HIV infection. This experiment sparked global outcry,and scientists considered that he had disregarded safety risks and violated ethical norms. But when it comes to altering the gene pool of future generations, the ethical boundaries are unclear. Of course, steaming ahead without carefully considering safety implications is unethical, but withholding a tool that could potentially alleviate human suffering on a global, irreversible scale from modern science likewise paints a bleak picture for our future.

gene editing offers not only the future of the global healthcare industry but likewise a new sector for private organisations to capitalise on

But gene editing can do a lot more than just correct ‘faulty’ DNA. There is hope in the scientific community that CRISPR can help combat cancer by genetically engineering our immune cells to better recognise and attack cancerous cells. This hypothesis was tested 5 years ago in a baby with leukaemia, who became the first in the world to be treated with designer immune cells. Although she was originally given months to live, she is now cancerfree, a response described as miraculous by doctors.

Although CRISPR is progressing in the agricultural world, there’s a lot more at stake when it comes to human health. One of the most contentious debates surrounding CRISPR is the question of germline editing. In other words, should we alter the DNA of our unborn children? While somatic gene editing only affects the patient being treated, germline editing changes the DNA of an embryo at its earliest stages, affecting every cell, including egg or sperm. This means that the edited gene will be passed onto future generations, along with any collateral DNA damage

Many have argued that gene editing in embryos is completely justified for disease treatment or prevention. But what if we want to simply enhance our children’s genes – make them more intelligent, more athletic, increase their lifespan? Is that justified? The prospect of genetic enhancement is thrilling to some, and terrifying to others. What may have started as an earnest scientific advancement to reduce disease or mortality may just develop into the creation of a superhuman race. Unequal access to healthcare across nations, as well as specific communities within nations, threatens non-discriminatory access to this revolutionary tool. Gene editing offers not only the future of the global healthcare industry but likewise a new sector for private organisations to capitalise on.

The next few decades will be crucial in determining how we handle this newfound power to rewrite our DNA. The events of the last year will leave a long-lasting fear of disease in our culture, and a mistrust of our body’s natural integrity. And if there’s one thing we’ve learned from recent events, society often finds itself scrambling to catch up with the fast-paced developments of the scientific world. So sometimes, it pays to be prepared.

WORDS:

32 THE FANTAS UNDER TICAL KNIFE

In the past half-decade, the body’s reality as a malleable surface has been brought to the foreground through the myriad of corporeal alterations advertised to us. Plastic surgery now ranges from getting filler at your local Superdrug, to the installation of permanent elf ears. The boundaries of what is possible under the knife broadens every day. Describing themselves as an ‘International Plastic Surgery Model’ and ‘Future fantasy being’, Luis Padron (@luispadron.elf) exemplifies this new trend in plastic surgery, which sees a shift from the ‘ideal’ to the fictional. Padron, who looks like an elf and who is currently waiting on their facial implants, acts as a visual representation of fantasy as a site of non-fiction. The questions then arise, why is this shift occurring and what are its implications?

Lucy McLaughlin (she/her)

ART: Yana Dzhakupova (she/her)

In

refashioning our faces to refect a fctional

While plastic surgery once functioned to overcome any bodily ‘defects’ or undesirable shoots and branches, it is now often used to champion a realm of aesthetics which goes beyond human perfection. In the case of the fantastic body altered by plastic surgery, the body becomes the surface upon which the worlds of reality and fantasy collide. However, people don’t always react positively to figures like Padron, and perhaps this is because when creaturely morphing takes place, our image of the ‘human’ becomes muddied. In refashioning our faces to reflect a fictional reality, we dismantle the concept of being ‘human’ and instead create a ‘post-human’ aesthetic. Those who aren’t ready to progress into this visual reality will be resistant, and those who want to move past the idealised beauty standards of the day will rejoice.

Though Padron moves towards the elf aesthetic, there are a plethora of other bodies transforming into other creatures. Anastasiya Shpagina (@anastasiya_fukkacumi) provides an alternate example of the unreal creature as she fashions herself as a doll – veering more towards the visual realm of toys, rather than sci-fi or fantasy. As with any female-presenting body, the feminine ‘doll’ aesthetic has a distinctly youthful quality to it which, unfortunately, always risks fetishization and misogyny. With her enlarged doll eyes and plastic appearing skin, Shpagina is undoubtedly one of the closest things we have to an anime character come-to-life. By transforming her facial features with both surgery and skilful makeup strategies (a parallel, temporary form of body alteration), Shpagina’s face becomes something other, something which normative society is not used to, someone people may react with hostility to.

the current rise of nihilism, in tandem with academic postmodern thought, has resulted in the disavowal of outdated labels, binaries and divisions as markers of a ‘true’ reality

Reactions, implications, and controversies of this post-human movement aside, it is important to also ask why figures like Padron and Shpagina choose to alter their surface appearance in favour of the fantastical in the first place. Is this turn to unreality a form of aesthetic escapism? Perhaps, and here’s why: the current rise of nihilism, in tandem with academic postmodern thought, has resulted in the disavowal of outdated labels, binaries and divisions as markers of a ‘true’ reality. Those who make the aesthetic fantasy their reality, such as Padron and Shpagina, embrace this nihilism, move into a post-human future, and roll with the hyperreal punches. They embrace the anarchy of a post-human existence through plastic surgery, transcending those who wish to defend more traditional markers of a stable reality.

Despite the positive view provided of those who lean into the post-human aesthetic, bleaker readings can be found if we poke our noses further into Instagram. For example, within the platform can be found a community of ‘Instagram dolls’ who name their plastic personas after their surgeon, thereby filling the role of a walking, talking, visual advertisement for their services. On their pages, there are a plethora of squares which detail desired shapes and provide a catalogue for future dolls to window shop procedures. The bodies of the dolls therefore oscillate tensely between images of empowerment and images of a potential capitalist transaction; in other words, they become objectified. Therefore like more traditional plastic surgery bodily ‘ideals’, post-human plastics also fail, in some regards, to provide a truly radical form of ‘post-human’ empowerment, one that is not co-opted into the modern system of capitalism or power, and its unachievable standards.

That being noted, it is fair to say that using plastic surgery to achieve a more fantastical art form definitely strays from the more idealistic, contemporary ‘baddie’ aesthetic that plastic surgery is typically utilised for. Especially at this post-human extremity, plastic surgery serves to connect the corporeal with the ideological, and to amalgamate reality with fantasy. In an era in which bodily autonomy is becoming increasingly celebrated, which end of the spectrum will you choose?

To be perceived is to have your existence acknowledged, but the way we’re understood is not always synonymous with our views of ourselves. While we attempt to control the way we’re seen, as women and femmes, the control is often wrestled from our hands. Being perceived by the world, and by men in particular, threatens not only the authentic depiction of our character, but also our safety. The male gaze is not just a by-product of capitalism or a talking point for film studies; it is a real presence in every aspect of our lives. It exists everywhere: in the street, at work, at school, and even seeps into our own perceptions of ourselves.

As a woman who reached puberty in the advent of social media, I have always been aware of the dangers associated with allowing myself to be seen online. When I first joined Instagram, my mum insisted on following me to make sure I wouldn’t post anything she deemed ‘too grown up’ or inappropriate. I thought this a melodrama until I saw girls years younger than me innocently uploading videos of gymnastics routines or photos with friends, only to be flooded with vile, sexual comments by fully grown men. They perceived these young girls as objects for their pleasure, validated by the fact these girls had, in their eyes, given them permission to gawk. The thing that broke my heart was that these girls saw no issue with these comments, thinking these ‘compliments’ accompanied by a heart eyes emoji were a sign of innocent admiration. It was then that I realised how little control I had over how I was perceived, and the extent to which male voyeurism concerning the bodies of women and children is normalised in our culture.

One online platform which has become a focal point in the discourse surrounding the risks of existing as a woman online is OnlyFans. When it comes to controlling your perception online, OnlyFans is a different ball game. In a world where girls posting selfies on Instagram is seen as an invitation for objectification and hypersexualisation, you don’t have to think too hard to understand that having OnlyFans, as a woman, makes you especially vulnerable to those who see your body as their property. To gain perspective I spoke with OnlyFans user Jo Helly about her experience on the site and the effect it has had on her existence online, and in real life.

of

Being perceived by the world, and by men in particular, threatens not only the authentic depiction of our character, but also our safety

The pain of being

Jo believes that starting an OnlyFans is the best thing she’s ever done. When I asked if she was able to keep the platform separate from other areas of social media, she explained that the promotion of Onlyfans on social media accounts is essential to the growth of your page - it’s impossible to keep the two worlds separate. However, Jo says one way she and other sex workers can maintain a sense of anonymity is to create separate social media accounts under an alias. Other precautions include avoiding any mention of where she lives, and making good use of the ‘block’ function should anyone cross a line in their communications. Despite these precautions, Jo admits she feels less safe online than before.

Online sex work can affect not only personal safety, but future job prospects also. When asked about this risk, Jo admits that although impact on employment opportunities is a fear, she doesn’t ever see herself in a regular 9-5. She explains, ‘I am painfully stubborn and independent so being anything other than self-employed for the time being absolutely does not suit me. I can’t imagine any other job giving me the amount of fulfillment online sex work does. OnlyFans and other sex working sites are absolutely included in my 5-year plan. I don’t majorly see myself being solely a sex worker as my career, but I wouldn’t count out the other skills sex work has taught me: photography, set design, editing, directing’.

Many of those who shame these women online are not only upholding harmful misogynistic ideals, but a twisted understanding of respectability as linked to traditional, capitalist ideology

Jo’s explanation emphasises the short-sightedness of those who perceive women that showcase their sexuality as incapable or unintelligent, falling back on their sexuality because they’re somehow lacking in other arenas. Of this, Jo says ‘In most cases sexuality is a direct route to lower intelligence in a lot of people’s minds. With some people, this is so entrenched that it’s not worth the emotional labour in trying to correct their ignorance.’

Rose Inglis (she/her)

Jo’s admission of the emotional labour involved in being perceived as a woman online touches on another important issue. So often, women are expected to explain and justify their presence online to those who are offended at their existence as multi-faceted individuals. In our misogynistic culture, existing online as a financially-successful, sexually confident woman comes with the inevitable backlash from men who fear women’s sexual prowess. In an attempt to hide their blatant sexism, those who shame online sex workers by claiming they’ll never find employment seem to miss the point entirely. The boom of online sex work is not only anti-patriarchal, but inherently anticapitalist. It is indicative of a wider disillusionment with traditional heteronormative dogma which values sexual modesty, marriage, and personal subordancy in the name of financial profitability, above all else. In an era of mounting unemployment and non-existent job security, the business model of online sex work provides a framework for the future of the working world. One in which we are no longer tied to the shackles of an employer, where we can determine for ourselves how much our time is worth. Many of those who shame these women online are not only upholding harmful misogynistic ideals, but a twisted understanding of respectability as linked to traditional, capitalist ideology.

Being perceived can be painful, but it should also be empowering. Our perceptions of selfhood, and our expression of femininity whether binary or otherwise, should not be altered by the ideals of others, online or in the real world. If we truly wish to move towards a future where women are not forced to overanalyse their every move, the commitment to eradicating societallyingrained, internalised thought patterns is a responsibility we must all bear. The future doesn’t have to be painful, but the weight of our collective action will be the deciding factor.

Yana Dzhakupova (she/her)

perceived WORDS

My mother always told me that I was a good child because I had no wants. She could take me with her to buy the groceries - only the essentials, of course - and I would walk past the aisles of bright plastic children’s toys and sickly sweets and glossy hardbacks adorned with dragons without so much as a glance.

At seven she told me the playground mothers were asking her for tips. She told me they were asking her because I was perfect. I was silent and small and I could slot into the kitchen cupboard and close my eyes when she needed some time alone. She told the mothers that there was no secret - really, nothing - other than believing. Believing in perfection and nothingness and seeing it materialise.

WORDS

Aimee MacDonald (she/her)

A PP N O P EA CH CO MPANION

It was ten years later when I began to wonder if I really existed. At seventeen, the boys and girls were at each other’s throats with love or hatred or ambivalence. Ambivalence which is not nothingness, because to be ambivalent is to have autonomy, I think. I never needed help with homework and I only spoke to the teacher once. When I did, standing at her desk after class, she looked right through me to the yellow wall adorned with mock World War Two propaganda posters. My poster wouldn’t stick to the plasterboard, no matter how much blue tack I used. It peeled and curled and took flight in a breeze from the open window, fluttering to rest at my feet on the rough hewn carpet.

The month before I turned twenty-one, I had an awakening of sorts. I awoke wanting a something, needing a someone. And I told my mother because she could hear me. She told me to think about what I wanted. Picture it until you can touch it and hear it and see it in perfect clarity. Until it appears in your dreams with a knowing smile. Until you unequivocally believe your imagined someone is a reality. Until your face in the mirror blurs slightly and your skin takes on a slight lucid shimmer and sometimes, sometimes, you may ever see yourself vanish for a brief moment – a second, half a second. Picture her until you would die so she may live.

This was the first and only thing in my life that I wanted, so my mother offered to help me. Not with the actual manifestation process, which was between just me and my someone. No, instead mother would sit me on her stiff pink chaise lounge in the living room – a room in our small house I had never previously entered – and tell me about myself.

When you first appeared, you were tiny and plastic. A little doll with black painted eyes and horse hair lashes. You came apart at each joint so I had to be careful not to drop you. I had to sing to you and change you and put you to bed and stroke your coarse fake head and you were oh so real. You were everything I had wanted – my quiet, quiet baby – and when I would take you out, we would be stopped every few steps by old people who wanted to coo and cackle and touch your chubby toes. An old lady placed a pound coin in your pram for good luck and I swear that was the first time I heard you gurgle. Then, the milk, which had dripped down your smooth cold cheeks – you began to drink it in, never demanding more and only taking what I was willing to give. And oh, I was willing to give you everything.

Later, in the bathroom with the door closed, I pictured my someone in the tiny square of mirror above the sink. I pictured individual segments, like pixels, as opposed to my someone as a whole. The soft delicate skin dotted with translucent hairs, the feeling of it on my fingertips, the dimples and curves and blemishes. My someone is not without fault like my mother’s someone. The sweet smell, fragrant, fresh. I became so absorbed that I could taste it on my tongue.

I could taste you.

You came into being on the morning of my birthday. My mother didn’t get me anything and I didn’t mind because she never had.

Our kitchen is at the back of the house, with a little window above the clinical white tiles that looks out over the square patch of our neatly trimmed lawn. Mother was hunched over with her elbows on the counters staring out into the green. You are going to have to give your someone so, so much life, she said as I entered.

And there you were in the porcelain sink, ripe and delicious with tap water trickling down your sides and collecting in your soft fur. The product of my long, lonely hours and the result of my years of nothingness.

A lifeless mother retreated from the room. It is a peach that sits on the side, daughter. And the fruit lights up your eyes.

///WORDS/// Trey Kyeremeh (he/him)

///CW/// discussions of death

CONTRIBUTORS

Words

Grace Stanley

Kate Fryer

Cain Mckendry

John Tinneny

Ella Field

Grace Graham-Taylor

Mia Squire

Ada Enesco

Lucy Mclaughlin

Rose Inglis

Aimee MacDonald

Trey Kyeremeh

Artwork

Charlotte Docherty

Yana Dzhakupova

Ella Ottersbach-Edwards

Filipa Semedo

Magdalena Kosut

Photoshoot

Designer: Oliver FJ Jones Studio

Photographer: Samuel Mitchell

Direction: Daniel Castro, Lara Delmage, Graham Peacock

Models: Latex, Jack Patton

TEAM

Editors-in-Chief: Graham Peacock, Lara Delmage

Editorial Coordinator: Ella Field

Features Editor: Eilidh Akilade

Politics Editor: Tom Hall

Culture Editors: Cain Mckendry, John Tinneny

Art & Photography Editor: Eilidh Wright

Science & Tech Editor: Tiarna Meehan

Style & Beauty Editor: Daniel Castro