PROJECTBASELINE 2.0

– Re-Connection: GUE & PB

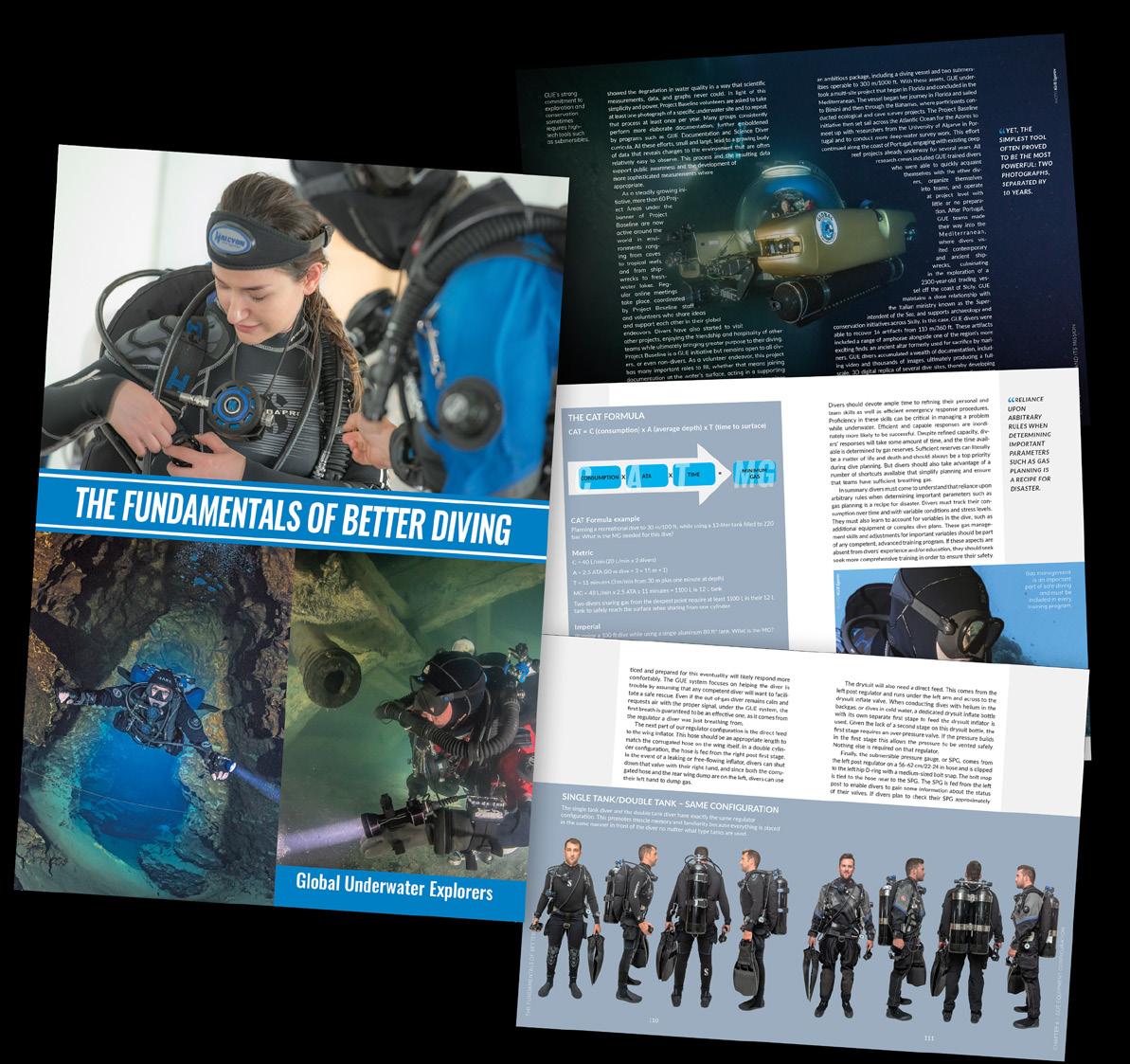

Project Baseline mobilizes citizen-divers to document and monitor changes in aquatic environments. Through strategic engagement with scientific, conservation, and governmental partners, it aims to contribute meaningful data that informs restoration and protection efforts for both natural ecosystems and cultural heritage sites. As a part 2 of the previous Quest article “The GUE Project Portal,” we will now touch upon all things Project Baseline: its mission, success stories, separation into a separate nonprofit, and the benefits of renewed synergy between GUE and PB with regards to the next generation of projects and conservation divers.

Project Baseline (PB) was initially started in 2009 to fulfill GUE’s commitment to underwater conservation. The idea for PB came about when GUE’s leaders realized that they were lamenting the degradation and loss of once stunningly beautiful underwater places due to the seemingly inevitable decline associated with progress and development. PB was, quite simply, their refusal to give into that notion of inevitability.

The baselines needed to define pristine, natural, or even acceptable environmental quality in the underwater world simply don’t exist. For the most part, the only baselines are the ones preserved in our memories, and those are shift-

ing progressively downward as every generation accepts some decline as inevitable. Unlike most terrestrial environments, underwater ecosystems lack the public visibility (the voice) needed to act on the alarming rates at which they’re becoming degraded and destroyed. PB was created to be that voice.

Project Baseline asks the people most connected to underwater environments to increase the volume of data needed by decision makers to restore and protect the type of world we all want to live in.

Meaningful contributions

Any diver—any snorkeler even—can make meaningful contributions to PB. The beauty of the initiative is that projects can be as simple as

Any diver can contribute to PB—from simple photo documentation to collecting scientific measurements.

November 2025 · Quest

TEXT MARCUS ROSE, TODD KINCAID, JENN THOMSON & JOSH MAXWELL

PHOTOS JASON BROWN & JP BRESSER

PHOTO JASON BROWN

taking a photo, or as complex as collecting data and/or detailed measurements for collaborating scientists, or anything in between. Regardless of the complexity, the highest aim of PB is to foster collaborations between divers and scientists to accelerate meaningful conservation efforts.

There are four loosely defined project definitions with PB:

COMMUNITY PROJECTS Typically volunteer divers working independently or as a team in their local areas or diving destinations.

COLLABORATIVE PROJECTS PB divers operating with academic or scientific organizations to advance scientific and/or conservation efforts. PUBLIC Ad hoc data submissions from the diving public.

MISSIONS Focused and aggressive survey efforts at the direction of one or more scientific or conservation collaborators that often involve more challenging diving and data collection techniques.

To date, 423 divers have contributed data to PB that they’ve collected from more than 10,000 dives conducted in 46 countries. They’ve documented more than 500 sites with nearly 5,000 photographs or videos and more than 125,000 data measurements. They’ve engaged in 33 collaborative projects and conducted 8 missions. There are currently 8 active collaboration projects, 20 active community projects, and 3 open public documentation projects.

More than just photos

Perhaps PB’s greatest weakness has been an inability to build on the good work of its members across the world to grow the number of participating divers. A persistent criticism of PB has been its emphasis on pictures. While it can be fairly said that simply photographing an environment falls far short of protecting it, that sentiment fails to recognize that lack of public awareness is the most pressing challenge facing underwater conservation.

Consider that people don’t tend to care about things or places they can’t see. Then consider that what divers take for granted will typically

never be seen by 99.9% or more of the population. Think then of the fraction of scuba divers who will take pictures of what they see and then the fraction of those pictures likely to depict how conditions may be impaired. Finally, think of the tiny number of that already tiny number that will ultimately be seen by anyone who might be in a position to act on the observation of conditions in a way that might lead to environmental improvement.

When viewed in that light, the perceived value of pictures that depict change in underwater environmental conditions through time hopefully increases. PB has not, however, been able to successfully make that case with the vast majority of the diving community. Consider what PB has been able to accomplish with the 423 participating divers. Then, imagine what PB could accomplish if 10%, or even 1%, of the roughly 8.6 million active divers in the world were participating.

Greatest challenge

Another major obstacle to PB’s success is the slow rate at which PB’s community projects make the jump to collaborations. Given that most of PB’s participants are not themselves scientists, perhaps not even well versed in the sciences describing the environments in which they dive, the reluctance to engage with professors, universities, research or government scientists, etc. is no surprise. Neither PB teams nor the scientists or conservationists they may hope to collaborate with will likely be very anxious to reach out to the other to get something started. The onus unfortunately will likely always fall to the PB team to make first contact.

Being able to point to their local PB efforts, regardless of how simple, and that their work is part of a global effort of organized and well-documented conservation work must and has made that first contact easier. It undoubtedly makes a positive outcome more likely. Once successfully engaged, PB’s history demonstrates that collaborative efforts will reap benefits often thought impossible by both the divers and the scientists with whom they work. The classic cliché is apropos: the whole truly is, or can be, greater than the sum of its parts.

Overcoming these obstacles, convincing divers of the value of pictures, leveraging the pictures and collected data to grow PB participation, and fostering effective and lasting PB conservation projects are our greatest challenges.

Models for collaboration

Between 2014 and 2017, GUE and PB worked with Global Subdive to develop and carry out a series of highly impactful scientific collaborations as part of several Baseline Explorer expeditions. The collaborative missions paired volunteer GUE technical dive teams with scientists from numerous universities, non-governmental organizations, and government agencies to document various types and localities of coral reefs between the near-surface and 100 m/330 ft depth.

The divers worked under the direction of the scientists, sometimes working alongside them in submersibles, to collect data and measurements that would advance scientific understanding of the coral reefs and, in turn, the politics of coral reef conservation. All of the collaborative

PB United Kingdom (PBUK) grew from local projects into a registered charity, creating a lasting, nationwide movement for conservation and community action.

missions were carried out aboard ships, mostly the r/v Baseline Explorer, enabling a nearly 24/7 focus on the mission objectives.

The overarching goal of the Baseline Explorer expeditions was to demonstrate the enormous value divers can bring to underwater scientific and conservation efforts. GUE and PB conducted several collaborative projects over the course of those four years, a few of which are summarized below.

One of the first missions aimed to document the distribution of black corals in the mesophotic zone along the slopes of several islands and seamounts comprising the Azores archipelago with a team of marine biologists from the University of the Azores in 2014. GUE divers collected video and coral specimens that were analyzed aboard the ship and subsequently used to support efforts to expand the designations of marine protected areas.

Working with the University of the Algarve, divers conducted video surveys and collected coral specimens to document the distribution of red coral (Corallium rubrum) in water depths

PHOTO JASON BROWN

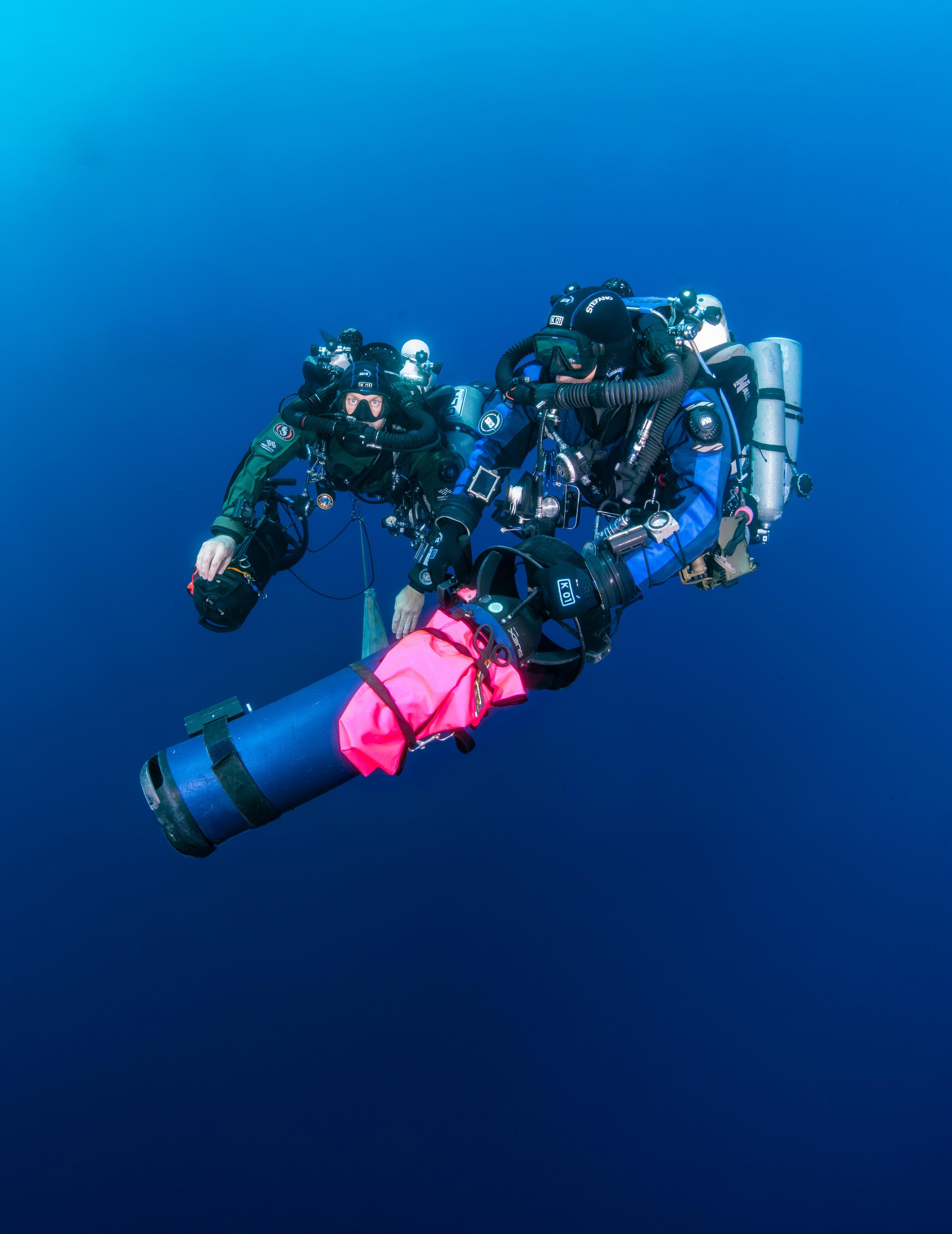

GUE divers joined the Baseline Explorer team, exploring deep reefs with the vessel’s submersible to support groundbreaking marine research and conservation efforts.

of between 60 and 100 m/200 and 330 ft off the south coast of Portugal. Their work extended knowledge of the distribution of Corallium rubrum in the Atlantic, led to the discovery of a rich deep-dwelling type of those corals, and verified the urgent need for protection from direct and indirect fishing activities.

Working with the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute in 2014 and 2015, divers documented mesophotic coral (Oculina varicosa) reefs between 60 and 100 m/200 and 330 ft water depth along Florida’s east coast between Fort Pierce and Port St. Lucie, and algae growth associated with wastewater pollution on shallower coral reefs between West Palm Beach and Looe Key. Results of their work revealed substantial loss of Oculina varicosa, likely due to dredge and trawl fishing practices, and helped to verify the loss of 90% or more of Florida’s living coral cover.

100 new species

A short but high-profile mission was conducted in 2016 with Miami Waterkeeper to document

coral reef conditions near Port Everglades in advance of a proposed port expansion project that threatens to further degrade Florida’s coral reefs. The GUE/PB team hosted CNN and Philippe Cousteau aboard the r/v Baseline Explorer to bring public attention to the condition of Florida’s coral reefs and the causes of their decline.

The largest of the collaborative missions occurred in 2016 with a UK-based NGO, Nekton. The mission focused on the state of the ocean around Bermuda, the Sargasso Sea, and the Northwest Atlantic and was supported by 40 partners, including the Governments of Bermuda and Canada, UNESCO, 12 marine institutes, five media outlets, and six technology companies. Thirty-two technical scuba dives and 77 submersible dives were conducted over a 32-day period. GUE divers collected video, still images, coral, algae, and water samples along 73 transects at depths between 15 and 90 m/ 50 and 300 ft depth and assisted researchers with the deployment and retrieval of specialized sampling equipment. Scientists worked within

PHOTO JP BRESSER

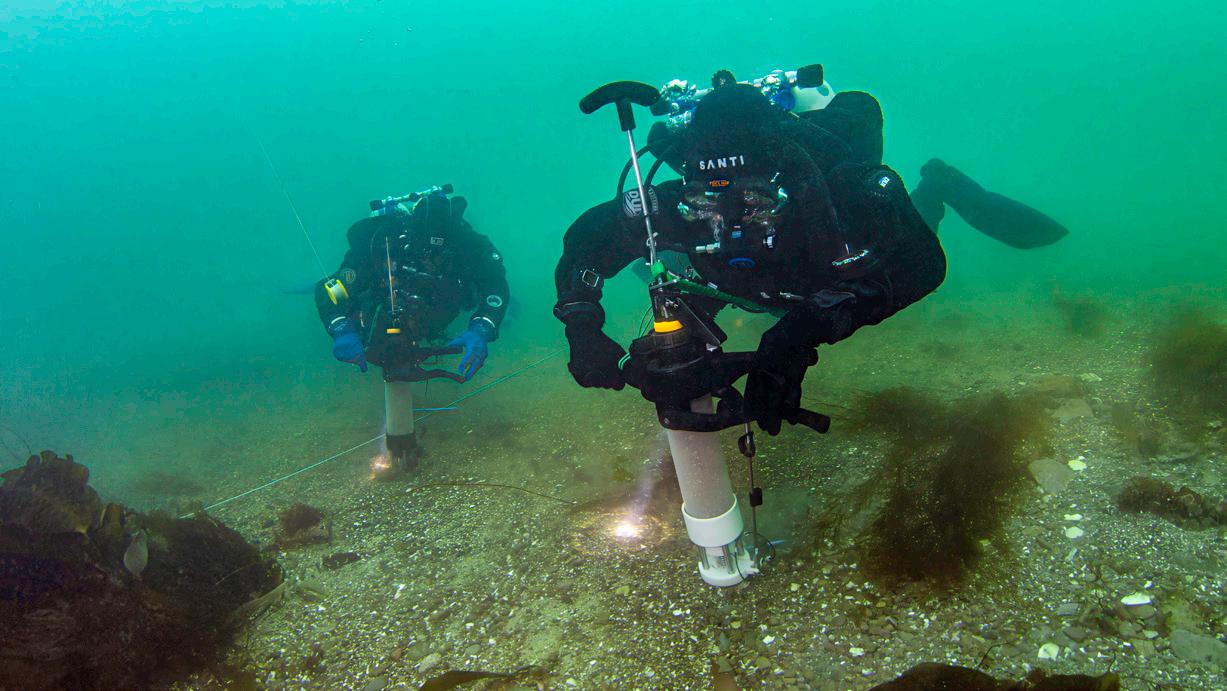

The PBUK team testing mechanical seeding devices designed to plant seagrass deeper into the substrate.

the submersibles along 65 transects in depths between 120 and 300 m/400 and 1,000 ft depth. Outcomes included the discovery of over 100 new species of marine life, 20+ scientific papers published, and curation of all specimens and samples into collections at the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo. Most importantly, the mission led to the Bermuda government committing to protect at least 20% of their ocean territory.

High-quality data

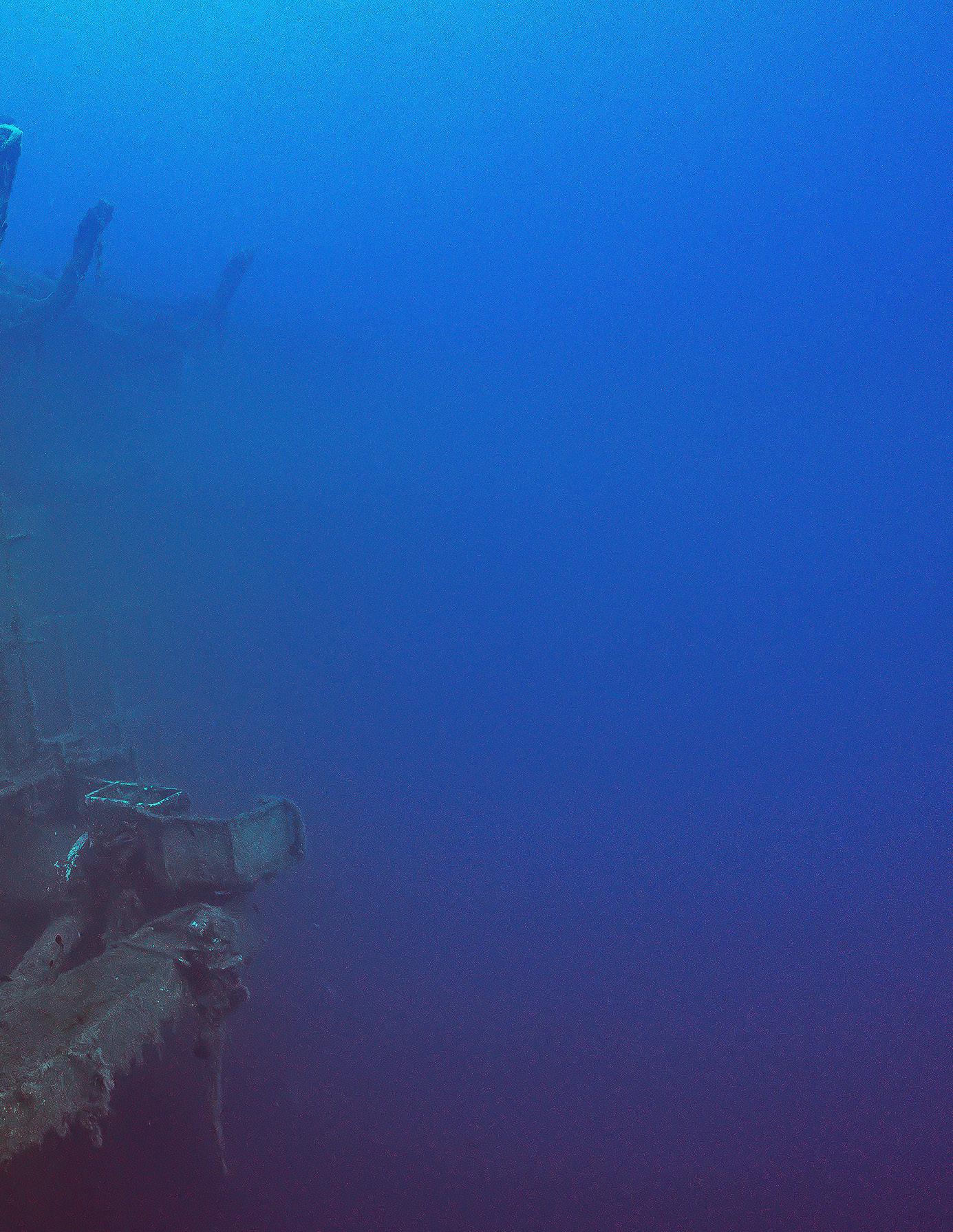

The collaborative nature of the PB missions also extended into the realm of shipwrecks, beginning in 2014 with the Italian Soprintendenza del Mare (Superintendency of the Sea) to document the wreck of the Hellenistic-era Panarea III off the coast of Sicily and ending with NOAA (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration) to document shipwrecks from the Battle of the Atlantic off the coast of North Carolina as well as protected shipwrecks with the Great Lakes National Marine Sanctuaries.

All of the collaborative missions were made possible by the efforts of volunteer divers pulled

from the global GUE community, working together to advance the ideals of PB. In each case, a small group of motivated and capable divers facilitated the collection of the high-quality data needed to support scientific documentation and reporting. Their efforts advanced the scientific and conservation goals of the collaborating entities much farther than those entities could have gone working within standard scientific diving programs.

Major team successes

Project Baseline is presently focused on helping teams across the world start and sustain collaborations of their own. Two of PB’s most successful projects in this regard are described below.

MARCUS ROSE (PROJECT BASELINE UK)

One of the success stories of PB has been the establishment of PB United Kingdom (PBUK) as its own registered charity. After several years of local community efforts popping up and then

PHOTO JASON BROWN

PBUK supported seagrass restoration through a variety of diving activities, including seabed surveys, seed collection, and planting.

tailing off in the UK, a small team decided to take a different approach in an attempt to establish a more enduring conservation effort. Rather than focusing all efforts on one small regional project, the team decided to take a national approach.

By setting up PBUK, the team created the flexibility to work with UK conservation groups or scientific initiatives wherever collaborators needed the divers to go. This approach in no way aims to undermine local efforts such as those of PB Midland Pools and PB Loch Alsh; however, an overarching nationwide approach has led to more collaborations, more variety for volunteer divers, and also provides an element of mentorship and support to the local community projects.

The decision to register PBUK as a charity was made to facilitate fundraising in the UK, as getting UK grants to pay into a US 501(c)(3) organization was extremely challenging. PBUK remains intrinsically linked to PB more broadly, but setting up as a charity in its own region made it easier to form collaborations. While the

local community projects are in no way subordinate to PBUK, the team has found real value in sharing resources and providing mentoring in both directions to further collective conservation efforts.

Since it was established in 2022, PBUK has completed several collaborative projects. The most notable of these has been the collaboration with the Blue Marine Foundation in the North Sea and work with the Ocean Conservation Trust on seagrass restoration on the south coast of the UK. The Blue Marine Foundation collaboration involved teams that conducted surveys for key species such as horse mussels and kelp as well as collected sediment samples for microplastics research. The most high profile of the efforts was benthic (seabed) surveys to support research into shipwrecks and their protection of marine species. This work ultimately resulted in the publication of an academic paper and educational materials for children.

PBUK’s support to seagrass restoration involved a range of diving activities, from simple seabed surveys to seed harvesting and planting.

PHOTO JASON BROWN

“The overall aim of the project is to restore seagrass ecosystems around the UK coast. Seagrass is an important habitat, as it provides both a carbon sink and a nursery for juvenile fish. Overall, the national approach taken by PBUK has led to more variety in the projects it supports and has created many more opportunities for collaboration by covering the whole of the UK. While this approach is certainly not for everyone, it shows the versatility of PB. Any project that is centered around exploration, documentation, or conservation has a place in PB. Provided the data associated with the project can be stored as a baseline for further projects, divers really do have the flexibility to take a PB effort in any direction they see fit.

of baseline data viewed by local scientific data collection agencies.

The overall aim of the project is to restore seagrass ecosystems around the UK coast. Seagrass is an important habitat, as it provides both a carbon sink and a nursery for juvenile fish.

The Monterey Bay site features four sites with a total of twelve stations. The baseline sites span a variety of dive areas to from which to collect data: Metridium fields, an old WWI-era sardine factory pipe, a sunken tugboat titled “Barge,” and a now-defunct scientific experiment to test kelp restoration protocols named the “Restoration site” that was set up in collaboration with local county agencies. The data collection from the Restoration site was particularly impactful because, after a two-year period, it helped demonstrate that culling endemic species of purple and red urchins was not the most optimal restoration solution.

JOSH MAXWELL (SITE MANAGER FOR POINT LOBOS, MONTEREY BAY SITES)

The PB sites at Point Lobos and Monterey Bay are managed by a group of dedicated GUEtrained divers that are also core members of Bay Area Underwater Explorers. The baseline site’s success can be attributed to consistent data collection efforts and being inclusive to all divers from all agencies. The Point Lobos site has been very active since 2015, and the Monterey Bay site has been active for 5 years, since its inception in 2020 during the pandemic.

Point Lobos State Park, which is considered one of the best California diving marine parks, features three new stations added just this past year and a total of twelve stations covering all the recreational diving range from 6 m to 30 m (20 ft to 100 ft) depth. The stations have shown giant kelp forests go from being completely depleted by hungry, grazing urchins during the seastar wasting disease period that spanned the eight years since 2015, to being fully restored with its lush algae kelp growth in the last two years. Site data features a rich photo mosaic

Both the Point Lobos and Monterey Bay PB sites are dive community success stories due to their consistent involvement in monitoring our local dive habitats and providing a database of rich photo mosaics.

Future synergy between PB and GUE (resources and classification)

In 2019, PB separated from GUE to become a standalone 501(c)(3) nonprofit, underscoring its commitment to collaboration with all divers and conservation stakeholders, regardless of affiliation. Despite this separation, the relationship between GUE and PB remains strong. GUE divers around the world continue to form the backbone of many PB efforts. The community-based nature of GUE, which is typically lacking in the broader diving community, has also proven to be a strong vehicle for the development of collaborative projects.

With the recent establishment of GUE’s NextGen program and project initiatives, and PB’s forthcoming database upgrade and reinvigoration of annual missions, it has become clear that the relationship between the two organizations needs to be, once again, re-envisioned such that their respective strengths can be best leveraged

PB allow divers to gain a unique connection to the ocean, turning every dive into a meaningful contribution to protecting marine ecosystems.

to achieve their shared conservation goals. A new and more formal framework of collaboration currently envisions: shared human resources and tools aimed at improving team coordination, public outreach and marketing, shared membership benefits and cross-promotion, and the integration of PB into the GUE NextGen program.

PB-DB 2.0 and PB Missions

The initial priority is the release of PB’s new and improved database. PB-DB 2.0 will be a major leap forward, accepting and displaying any form of numerical data, images, video, and 3D models. PB-DB 2.0 will also provide an upload interface, allowing Project Managers and select users the ability to better manage their data. Perhaps the biggest change will be the ability to accept survey data and generate line maps (e.g., cave maps) on the fly.

Moving forward from 2025, PB and GUE will once again work together to organize at least one mission opportunity per year. The overarching goal will be to conduct missions that are at least one week long in areas of the world that feature different forms of marine life. Each mission will aim to establish and document multiple

sites while following a systematic documentation plan. Divers will consist of volunteers from the GUE community who possess the level of training commensurate with the documentation objectives , whenever possible all divers at or above the Tech 1 level.

Another goal will be to collaborate with one or more scientific or conservation entities, which will likely require the assembled team to learn about and develop documentation/sampling plans with guidance from the collaborator(s). All collected data will be shared with the collaborators and uploaded to the PB-DB 2.0.

Between dives, participating divers will be able to attend lectures and presentations covering all aspects of PB, as well as topics related to understanding the specific forms of life and the ecosystem at the mission locations. The divers will also be asked to participate in or even organize outreach efforts, including social media posts and videos, and potentially a presentation for the local community.

It is hoped that these missions will inspire more divers to engage in PB and inspire scientists and conservation organizations to seek out PB collaborations.

PHOTO JASON BROWN

Before he ever dreamed of diving into the ocean, Thanapol Tantagunninat dreamed of floating among the stars. A fascination with machines and exploration led him from Thailand to the U.S. Space & Rocket Center, where a simulated “neutral buoyancy” session revealed something profound: the same sense of wonder he’d imagined in space existed beneath the water’s surface. That moment set the course for a life defined by curiosity, precision, and purpose. As the GUE NextGen Scholar for 2024-25, Thanapol’s journey has taken him from robotics labs at Georgia Tech to the underwater classrooms of High Springs, Mexico, and Cyprus. Along the way, he’s discovered that both technology and diving share the same core values: teamwork, responsibility, and the pursuit of excellence. “From Space to Sea” is his story—a reflection on how exploration, in any medium, begins with imagination and grows through community.

SCHOLAR

Growing up, I was the kind of kid who took apart remote-control cars just to see how the gears worked. I was fascinated by machines and the invisible logic of technology shaping the world around us. My biggest dream was to become an astronaut—an explorer of unknown worlds.

Years later, that dream took me to the U.S. Space & Rocket Center, where I attended the week-long Advanced Space Academy. One afternoon, we were told we’d experience “neutral buoyancy” in the Underwater Astronaut Trainer, providing a way to simulate the feeling of weightlessness in space.

The moment I descended into the pool, something clicked. I remember the hiss of the regulator, the stillness of the water, and the strange comfort of being suspended in three-dimensional space. For the first time, I felt the freedom and curiosity I’d always associated with space—only this time, it was underwater. It was humbling to realize that human ingenuity had allowed us to breathe in the place where we were never meant to. That experience never left me.

When I returned home to Thailand years later, I carried that memory like a compass. During college, I saved every baht I could until I could finally afford my Open Water course in the eastern sea of Thailand. Then finally, I did it. My instructor was technical-minded. While most students were content to “just dive,” he emphasized awareness, control, and problem-solving. He shared knowledge, stories, and pathways into technical diving that deeply inspired me.

For the first time, I understood that diving wasn’t just about science—it was about art and craft as well. Watching my instructor move calmly underwater, I felt admiration. I wanted to reach that level—not for recognition, but because of the pursuit of excellence itself.

To me, diving is a privilege. The more we expand our capabilities to dive, the more we realize how fortunate we are to witness a world that fewer and fewer people will ever see. And that privilege carries a responsibility to dive thoughtfully, to learn from the inner space of our planet, and to protect it for the future.

Engineering the depths

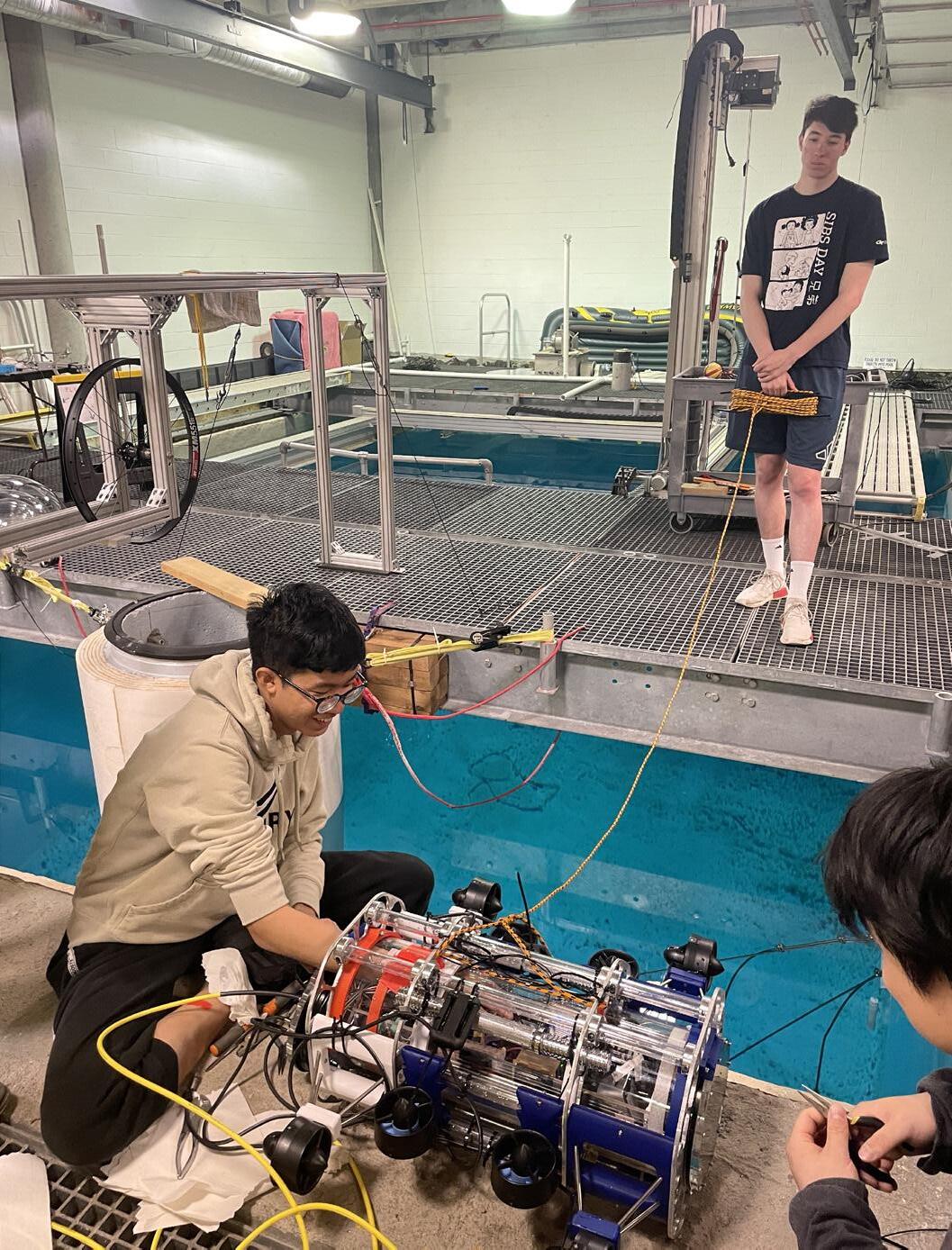

That same pursuit of excellence guided me to Georgia Tech, where I pursued a master’s degree in robotics.

My research focused on bio-inspired underwater soft robotics—machines that mimic the flexibility and undulating motion of marine life. I loved the idea of designing robots that could move gently, efficiently, and harmoniously through the water, extending exploration into places that require delicate, environmentally friendly interaction.

As the Mechanical Lead for the Georgia Tech Marine Robotics Group’s RoboSub team, I led the hardware design of autonomous underwater vehicles capable of completing complex navigation and manipulation missions. Long nights tuning tolerances for 3D prints and balancing buoyancy taught me that exploration is never a solo act—it’s a harmony of design, collaboration, and trust in your team.

Through both robotics and diving, I’ve come to see technology not as a replacement for humans but as a partner in exploration. Robots can survey hazardous environments, map caves, or provide live data to scientific divers. But the human element—intuition, emotion, problem-solving, and storytelling—remains irreplaceable.

The path to the NextGen Scholarship

Fast forward to 2023. At the GUE conference, I stumbled across a silent auction listing: “GUE Fundamentals Course.” My heart raced. I’d been dreaming of taking Fundamentals to start my journey toward technical diving, but during grad school, it felt out of reach. Without thinking twice, I placed a bid—and a few days later, I won!

That’s how I met GUE Instructor Arthur Nguyen-Kim, who had donated a spot in his class to the auction. Arthur didn’t just teach me to dive better; he introduced me to GUE’s world, where mentorship means believing in someone’s potential before they see it themselves. His support during that first class cemented my commitment to this path.

I didn’t just want to be a better diver; I wanted to live by the same standards of excellence GUE represents. So, I applied for the GUE NextGen Scholarship and was selected.

Tan working on autonomous underwater vehicles at Georgia Tech Marine Robotics Group’s RoboSub team.

After earning his Recreational pass, Tan trained to improve his cold tolerance until he finally decided to get a drysuit.

Just like 2022 NextGen Scholar Jenn Thomson’s experience, Jarrod surprised me during an initially camera-off call, with only one question asked during my so-called “interview”: Was I ready to be a GUE NextGen Scholar? And of course, Jenn was his accomplice! I was still shocked a few days after that.

Getting started

During my scholarship year, I aimed to learn as much as possible from GUE’s world-class instructors—explorers, conservationists, scientists, and educators who embody the highest standards of diving and exploration. I wanted to connect with GUE communities across the globe, experience diverse diving environments, and gain a deeper understanding of these unique environments while identifying opportunities for improvement in diving and conservation projects. I approached this year as an opportunity to lay the foundation for a stronger path forward, both for my own growth and for contributing to the future of exploration and the diving community.

Training in Florida with Stretch Altenhein in pursuit of a Fundamentals Technical pass.

My GUE NextGen journey officially began in High Springs, Florida, under the instruction of GUE Instructor Jon Kieren. Jon’s experience spans the world’s hidden frontiers, from the legendary KUR projects in Florida to deep cave systems in Mexico’s Rio Uluapán and Huautla Resurgences, Texas’s Phantom Cave, and Sardinia’s Su Gologone. He teaches with a significant emphasis on what he learned from thousands of hours down there, where mistakes aren’t a viable option.

Every drill he taught carried the weight of necessity. Maintaining trim, perfecting propulsion, and maintaining awareness weren’t just checking skills boxes; they were a language of precision. I learned to rush less, think more, and move with intention.

Jon’s mentorship went beyond skills. “It’s easy to get caught up in trying to pass,” he said. “But don’t forget why you started this—because it’s fun.” That hits hard. Whenever I find myself stressed about performance or results, I return to that reminder: I started all of this because diving is fun!

PHOTO KYLE COOPER

Refining the foundations

As part of the NextGen Scholarship, each scholar receives a personalized Halcyon wing.

After earning my Recreational pass, I kept practicing, determined to refine every weakness— especially my cold tolerance. Winter diving in Florida meant 20°C/68°F water and 4°C/40°F air at Morrison Springs. After one freezing dive, I decided: that’s it, I’m getting a drysuit. Thanks to our generous sponsor Halcyon, who is also the Santi distributor in the US, I used a big chunk of my scholarship equipment budget towards a beautiful Santi Elite+ drysuit to continue my journey.

A few months later, I trained with Kelly Colwell in Panama City Beach for a Drysuit Primer. Drysuit diving completely changed my experience. No more cold, no more shivering—just stability and comfort. Kelly’s patience and deep knowledge helped me learn proper care and control (and how not to end up like a turtle on the surface).

Next, I trained with Stretch Altenhein in pursuit of my Fundamentals Technical pass. Stretch had a gift for turning jam-packed, intense days into enjoyable learning experiences with his patience and kindness. Under his men-

torship, I earned my Tech pass and discovered the beauty of constructive and compassionate teaching. He also shares his love for nature—especially the beautiful duckweed pond of Manatee Springs State Park.

With the goal of being a resource to the team in mind, I embarked on my journey to refine my rescue skills in multiple scenarios. My Rescue Primer journey took me to the heart of Mexico’s cenotes under the guidance of Annika Persson. We practiced everything from compass-based searches and lost diver scenarios to full Basic 5 surface rescues and unconscious diver rescue scenarios. Even routine procedures revealed their complexity underwater: small mistakes could cascade quickly, and every action demanded thoughtfulness. Navigating challenging scenarios and learning from Annika’s decades of experience highlighted the heart of GUE training: awareness and prevention over reaction. We're not just training to dive—we're training to be reliable and competent teammates. The kind of divers who are assets, not liabilities, to their team.

Scooter diving in Cyprus after completing the GUE DPV 1 course in the clear blue Mediterranean.

PHOTO IMAD FARHAT

Before GUE, I thought competence meant independence. After GUE, I realized it means interdependence—knowing your role, mastering it, and trusting others to do the same.

Expanding horizons

By May, I found myself on the rocky shores of Protaras, Cyprus, standing beside my DPV like a kid with a rocket ship. The water shimmered in the most beautiful shade of blue from my childhood sketchbook.

At the very start of my NextGen year, Imad was very kind to offer me a spot in his GUE DPV 1 class. Thanks to Jenn, who connected me with Imad for this amazing opportunity.

For the first few days of my trip, I joined as a teammate in Imad’s GUE Fundamentals class, training alongside Marcel from Germany in the turquoise waters of Green Bay, a place that quickly became our outdoor classroom for the week. It was my fourth Fundamentals class, yet each one feels new; the further I go into GUE training, the more I realize that there are endless learning opportunities for those who seek them.

his spirit—that exploration isn’t only about doing serious stuff to hit goals, but it’s also about joy, spirit, and passion for the underwater world.

Sharing the passion

As I packed up my gear on the last day, I realized how much this experience had given me: new skills, deeper confidence, and friendships that made the journey even more meaningful. Cyprus was more than a course; it easily turned into an unforgettable week for me.

“Before GUE, I thought competence meant independence. After GUE, I realized it means interdependence—knowing your role, mastering it, and trusting others to do the same.

Once DPV 1 began, everything changed. Controlling the scooter, balancing thrust, maintaining awareness while task-loaded, and executing drills was both technical and exhilarating. Imad’s engineering mind on efficiency was evident in every detail, from the way he structured each day of training and organized the logistics to how he handled problems under stress.

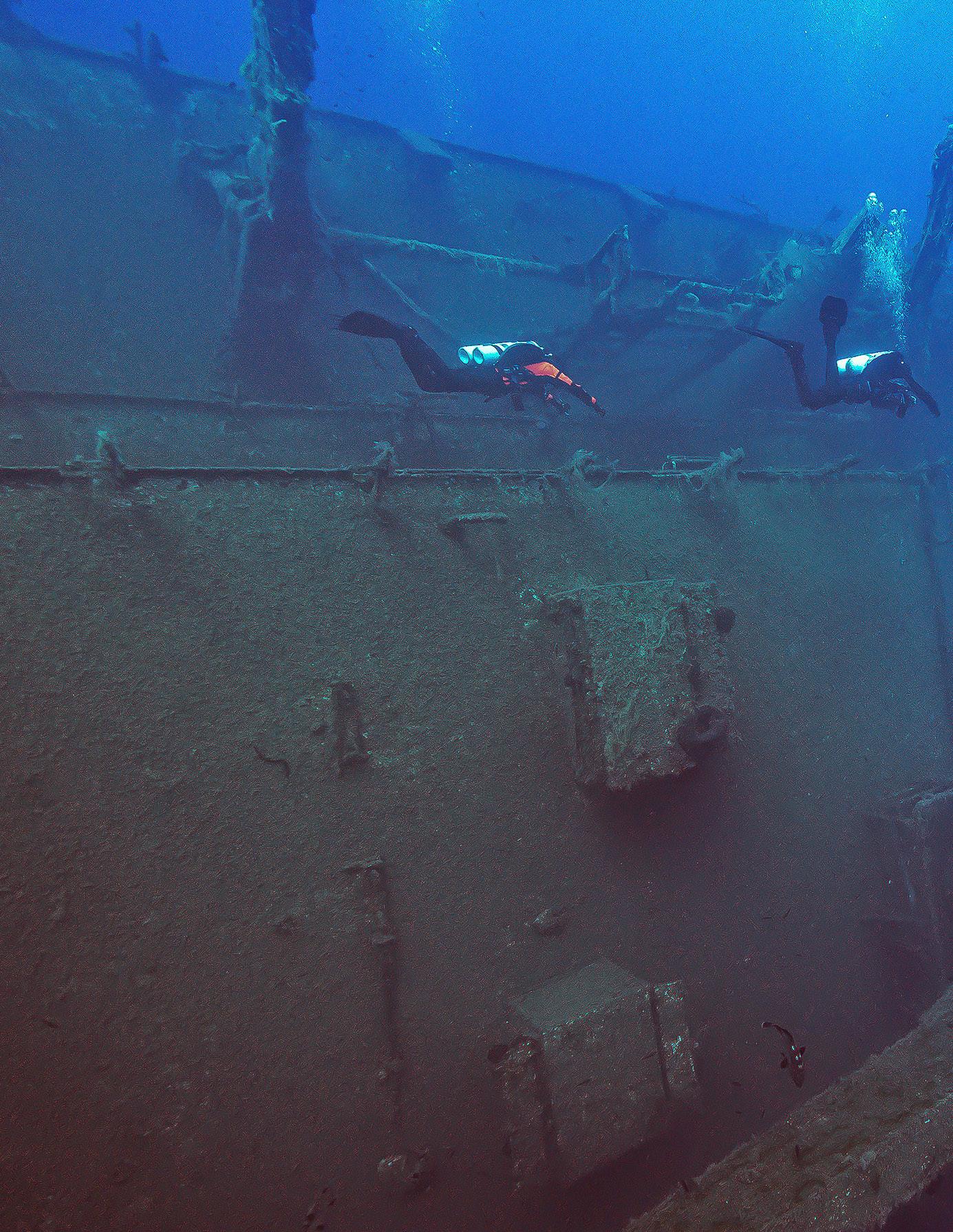

The highlight of this GUE DPV 1 course was planning and executing a DPV dive to the Ottoman-era wreck Nissia, part of Cyprus’s archaeological project. We planned a 20-minute scooter ride out into the blue, and wandering through history with a scooter felt like time travel—a blend of technology, curiosity, and wonder. Imad’s mantra stuck with me: “There’s no DPV dive that isn’t a great dive.” It perfectly captured

After Cyprus, I joined the first-ever GUE Young Divers Program in Sardinia, which was a completely different kind of adventure. Instead of focusing on training programs, this time it was about sharing—passing on the excitement of diving and sharing passion with divers of a similar age from around the world. We also had the opportunity to learn from the group of great GUE instructors who were supporting the next generation of young divers through the project diving, documentation, and cave geology workshop, led by GUE Instructors JP Bresser, Dorota Czerny, and Jenn Thomson. We worked together on capturing and documenting the experience. Between dives, we experimented with cameras, lights, project planning, and storytelling—figuring out how to make simple footage come alive. We learned how much good narration, composition, or even a well-placed light could change how people feel about what they see.

To make things even more interesting, we also had a “Psychologically Wise Leadership” workshop with Dr. Sean Talamas, which focused on growth through storytelling and failure, the power of advice giving, and reflecting on individual values and identity. This is where we got the opportunity to learn more about our inner selves and our teammates on a deeper level, and grow together to be the future leaders. It wasn’t the most technical week, but it was one of the most rewarding. The program reminded me that creativity, perseverance, and diving go hand in hand.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THANAPOL TANTAGUNNINAT

YEAR AROUND THE WORLD

Sardinia’s clear blue waters, stunning underwater topography, and beautiful caves are incredible. I only wished I had the skills and knowledge to perform a cave dive so I could explore this island on the inside!

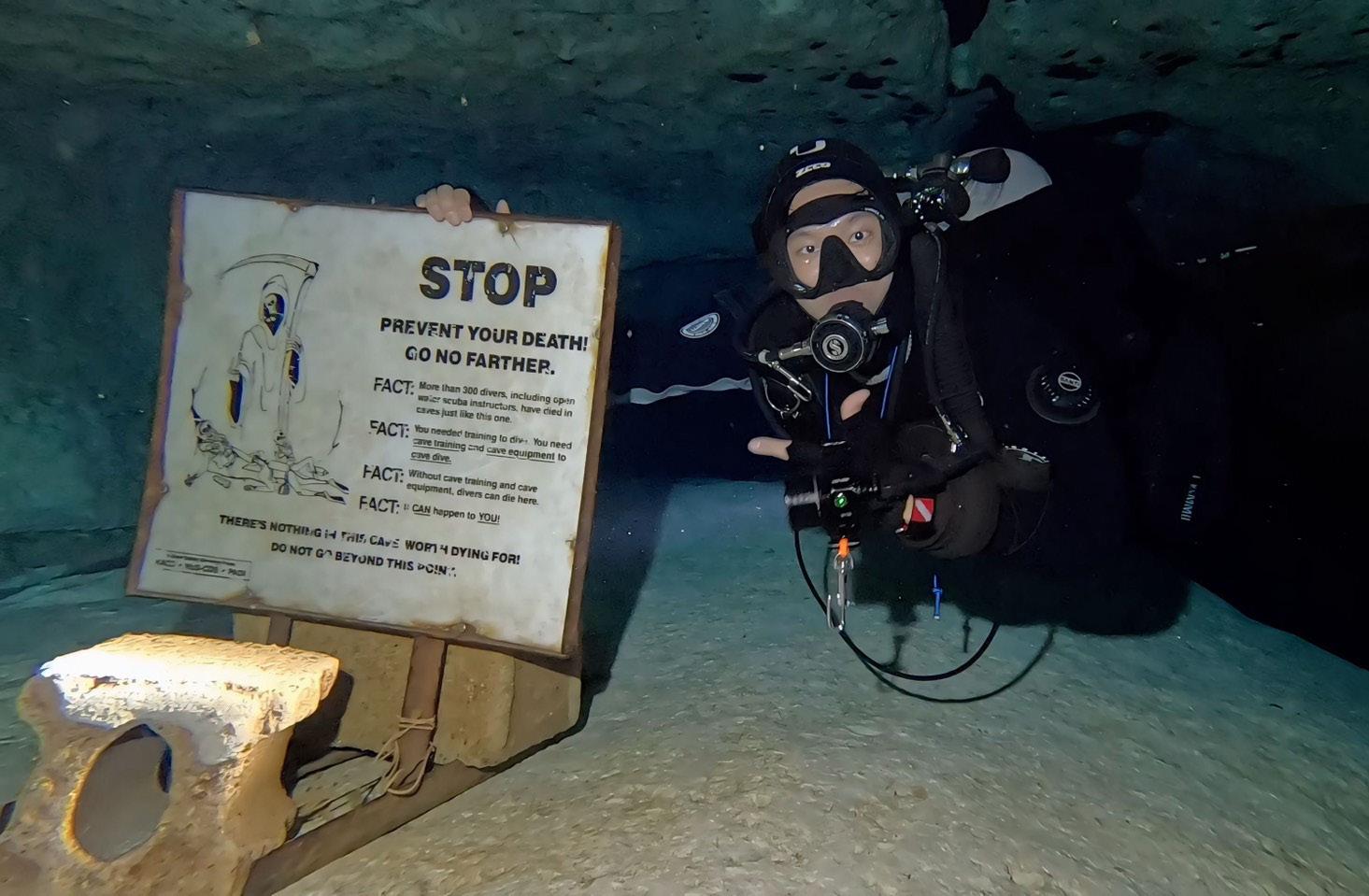

Into the darkness

Caves are among Earth’s last frontiers—vast, dark, and still largely unexplored. Despite our advanced robotics technology, these environments still demand human explorers.

“Under Jon’s guidance, I learned what true awareness means. Everything he emphasized in my first Fundamentals class—trim, light communication, team positioning, and procedures—suddenly made perfect sense in the cave environment. What once felt like a nitty-gritty detail now felt like an essential trait we need to perfect for survival.

The Global GUE Community

Throughout the year, I joined GUE communities across continents: SEUE, PCUE, GUE Thai, GUE Austin, GUE Cyprus, GUE Mexico, OCUE, MWUE, and BAUE. Each was unique in setting with different locations and different environments, but all were united in spirit.

When I finished the course, I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude. Gratitude for the instructors who believed in me, for the training that prepared me, and for the privilege of seeing places even a smaller fraction of humans ever will.

The GUE community is the closest thing I’ve ever seen to a global family—a network of people bound by shared standards, values, and curiosity. Everywhere I went, I was welcomed as “one of us” and offered continuous support. It was never about proving yourself to be “good enough” to join; instead, the question was always, “When can we dive together, what do you need, and how can we help?”

This is uniform amongst all GUE communities I’ve met, and I believe that community is one of the pillars that gives GUE its strength today.

During a zero-visibility drill, I shared gas with my teammate, maintaining physical contact as we slowly followed the guideline out. During every kick and every signal, awareness mattered the most. The training from Fundamentals came back instinctively. That’s when I understood: any diver can go into a cave, but only the well-trained cave divers can make it back home safely.

Hearing how his excited student wanted to be an explorer, he smiled and said, “Those caves will always be there—it’s just a matter of when you’ll get to them.” That line stuck with me. Exploration isn’t a race; it’s a journey earned through patience, perseverance, and trust in yourself.

When I finished the course, I felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude. Gratitude for the instructors who believed in me, for the training that prepared me, and for the privilege of seeing places even a smaller fraction of humans ever will. Because that’s what cave diving truly is—a privilege.

Closing notes

Looking back, I see a mosaic of role models, mentors, teammates, and lessons that shaped me into the diver I am today—proud to be a GUE diver and to be a part of the GUE community. This scholarship gave me more than opportunities; it gave me perspective, experience, and lessons that extend far beyond diving.

I want to express my deepest gratitude to GUE for supporting the NextGen Scholarship program and making this transformative year possible. To every instructor who shared their time, knowledge, and passion—Arthur Nguyen-Kim, John Kendall, Jon Kieren, Kelly Colwell, Annika Persson, Stretch Altenhein, Imad Farhat, JP Bresser, Dorota Czerny, and Jenn Thomson— thank you. Your selfless dedication, patience, and belief in my potential have left a lasting mark on me. Every lesson, every piece of guidance, and every moment of mentorship meant far more than a certification. Your wisdom, philosophy, and passion for exploration are truly

Caves remain one of Earth’s final frontiers. Even with advanced robotics, these environments still rely on human exploration. Everything from his first Fundamentals class suddenly made sense in the cave, revealing these details as essential for survival.

PHOTO AUSTIN BARBER

PHOTO SJ ALICE BENNETT

“To every GUE diver I met across the globe: thank you for showing me that wherever we dive, we truly share the same purpose. The sense of community, support, and shared purpose is unlike anything I’ve experienced elsewhere.

Thanapol “Tan” Tantagunninat is a Thai mechanical engineer, roboticist, and passionate diver whose work connects exploration and technology. His fascination with the ocean began at the U.S. Advanced Space Academy, where a first breath underwater in the Underwater Astronaut Trainer inspired a lifelong curiosity about the links between space and the sea. Tan earned his

Master’s in Robotics from Georgia Tech, leading the design of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle and developing a bioinspired soft robot for delicate marine environments. As GUE’s 2024–2025 NextGen Scholar, he hopes to advance as a capable, resourceful diver while integrating technology and diving to support innovation, exploration, and conservation.

Thanapol Tantagunninat

contagious, and I hope to carry that spirit forward, sharing it with others around the world.

I also want to thank Halcyon and Santi for their generous support with top-quality equipment. The tools they provided allowed me to fully engage with each experience and focus on learning, exploration, and growth in style, without having to worry about their reliability.

To every GUE diver I met across the globe: thank you for showing me that wherever we dive, we truly share the same purpose. The sense of community, support, and shared purpose is unlike anything I’ve experienced elsewhere.

Looking forward, I hope to continue growing as a capable, reliable, and resourceful diver,

ready to contribute to exploration, conservation, documentation, and scientific projects. I dream of using my engineering skills to bridge gaps in these efforts, creating a future where technology extends our reach, while human intuition ensures our humanity remains at the heart of exploration. Beyond my own growth, I aim to share my work, my story, and my passion with the broader public and the next generation of divers, inspiring others to pursue curiosity, responsibility, and excellence—all beneath the one flag of GUE, a global community united by shared values and a love for exploration.

And sometimes, late at night, I find myself back in that Space Camp pool, remembering the dive where it all began.

During the DPV course in Cyprus, Tan also had the opportunity to explore the iconic Zenobia wreck.

MORE

www.gue.com/nextgen-scholarship