RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

LATEST APPROACHES TO

ALLERGIC RHINITIS COPD

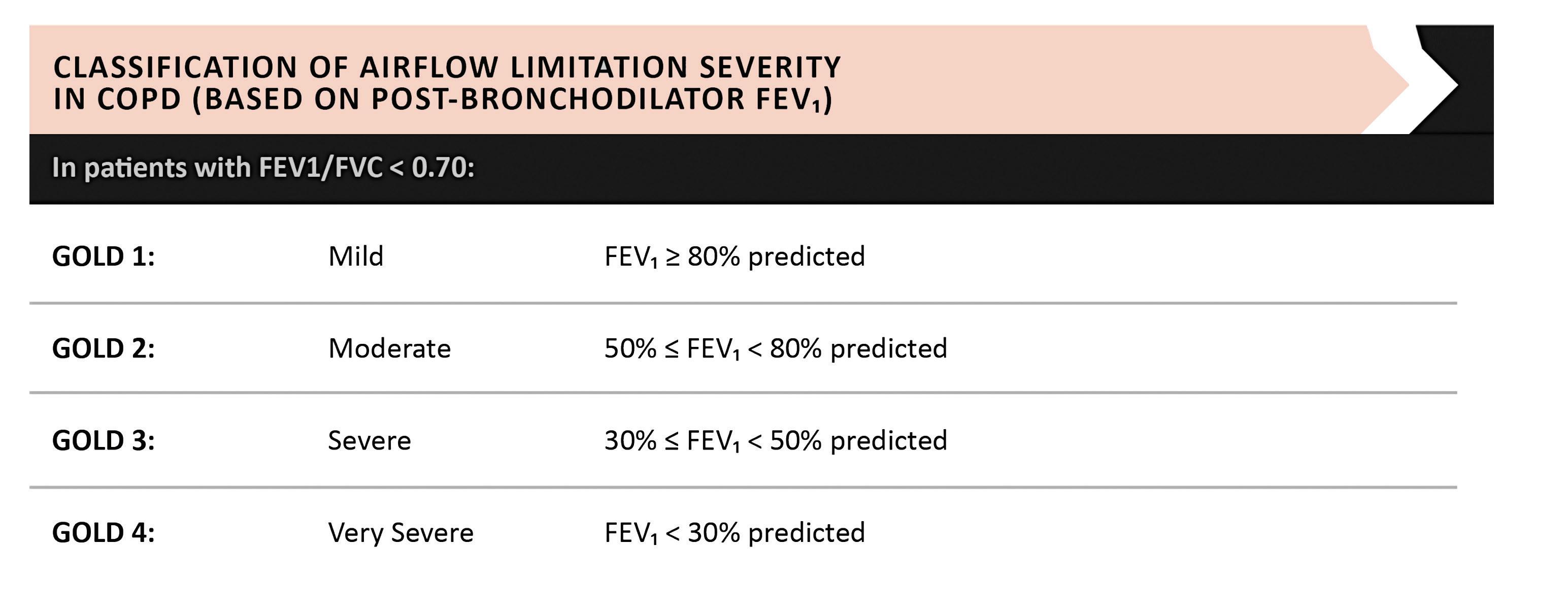

GOLD 2022 updates

Pulmonary rehab for

LONG COVID

LATEST APPROACHES TO

ALLERGIC RHINITIS COPD

GOLD 2022 updates

Pulmonary rehab for

LONG COVID

ASTHMA IN FOCUS

ASTHMA IN FOCUS

VOL 8 ● ISSUE 5 ● 2022

VOL 8 ● ISSUE 5 ● 2022

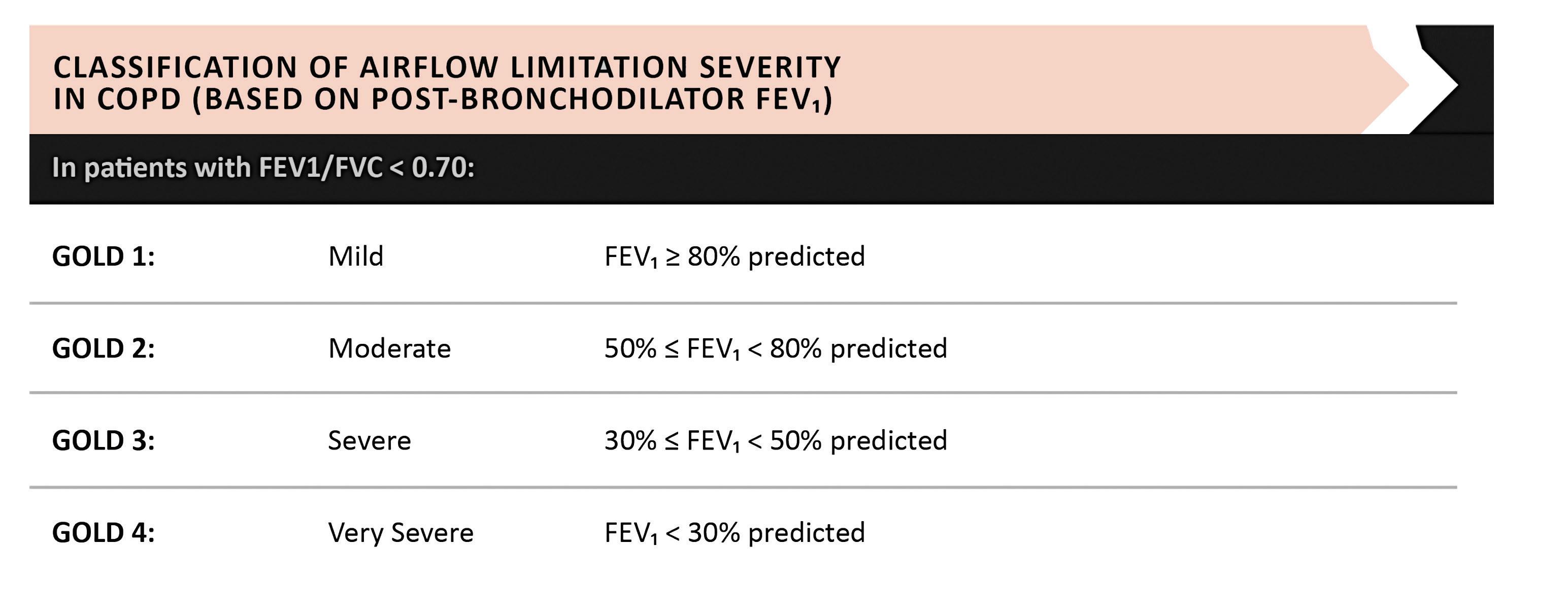

For patients not adequately controlled on dual therapy with moderate to severe COPD

UNLEASH THE PROTECTION

OF TRIXEO1,2

Significant protection against exacerbations*

TRIXEO Aerosphere is indicated as a maintenance treatment in adult patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who are not adequately treated by a combination of an inhaled corticosteroid and a long-acting beta2-agonist or combination of a long-acting beta2-agonist and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist.1

*Significant reductions in the rate of moderate or severe exacerbations vs LAMA/LABA (24%, n=2137 vs n=2120, annual rates 1.08 vs 1.42, 95% CI 0.69–0.83; p<0.001) and ICS/LABA (13%, n=2137 vs n=2131, annual rates 1.08 vs 1.24, 95% CI 0.79–0.95; p=0.003).1,2 COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist. In the clinical trial programme for TRIXEO, LAMA/LABA refers to glycopyrronium/formoterol fumarate and ICS/LABA refers to budesonide/formoterol fumarate. ©AstraZeneca 2022. All rights reserved.

ABRIDGED PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

TRIXEO AEROSPHERE® 5 micrograms/7.2 micrograms/160 micrograms pressurised inhalation, suspension (formoterol fumarate dihydrate/glycopyrronium/budesonide)

Consult Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing. Indication: Trixeo Aerosphere is indicated as a maintenance treatment in adult patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who are not adequately treated by a combination of an inhaled corticosteroid and a long acting beta2 agonist or combination of a long-acting beta2 agonist and a long acting muscarinic antagonist.

Presentation: Pressurised inhalation, suspension. Each single actuation (delivered dose, ex-actuator) contains 5 micrograms of formoterol fumarate dihydrate, glycopyrronium bromide 9 micrograms, equivalent to 7.2 micrograms of glycopyrronium and budesonide 160 micrograms.

Dosage and Administration: The recommended and maximum dose is two inhalations twice daily (two inhalations morning and evening). If a dose is missed, take as soon as possible and take the next dose at the usual time. A double dose should not be taken to make up for a forgotten dose. Special populations: Elderly:

No dose adjustments required in elderly patients. Renal impairment: Use at recommended dose in patients with mild to moderate renal impairment. Can also be used at the recommended dose in patients with severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, only if expected benefit outweighs the potential risk. Hepatic impairment: Use at recommended dose in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment. Can also be used at the recommended dose in patients with severe hepatic impairment, only if expected benefit outweighs the potential risk. Paediatric Population: No relevant use in children and adolescents (<18 years of age). Method of administration: For inhalation use. To ensure proper administration of the medicinal product, the patient should be shown how to use the inhaler correctly by a physician or other healthcare professional, who should also regularly check the adequacy of the patient’s inhalation technique. Patients who find it difficult to coordinate actuation with inhalation may use Trixeo Aerosphere with a spacer to ensure proper administration of the medicinal product.. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substances or to any of the excipients.

Warnings and Precautions: Not for acute use: Not indicated for treatment of acute episodes of bronchospasm, i.e. as a rescue therapy. Paradoxical bronchospasm: Administration of formoterol/glycopyrronium/budesonide may produce paradoxical bronchospasm with an immediate wheezing and shortness of breath after dosing and may be life threatening. Treatment should be discontinued immediately if paradoxical bronchospasm occurs. Assess patient and institute alternative therapy if necessary. Deterioration of disease: Recommended that treatment should not be stopped abruptly. If patients find the treatment ineffective, continue treatment but seek medical attention. Increasing use of reliever bronchodilators indicates worsening of the underlying condition and warrants reassessment of the therapy. Sudden and progressive deterioration in the symptoms of COPD is potentially life threatening, patient should undergo urgent medical assessment. Cardiovascular effects: Cardiovascular effects, such as cardiac arrhythmias, e.g. atrial fibrillation and tachycardia, may be seen after the administration of muscarinic receptor antagonists and sympathomimetics, including glycopyrronium and formoterol. Use with caution in patients with clinically significant uncontrolled and severe cardiovascular disease such as unstable ischemic heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrhythmias and severe heart failure. Caution should also be exercised when treating patients with known or suspected prolongation of the QTc interval (QTc > 450 milliseconds for males or > 470 milliseconds for females), either congenital or induced by medicinal products. Systemic corticosteroid effects: May occur with

any inhaled corticosteroid, particularly at high doses prescribed for long periods. These effects are much less likely to occur with inhalation treatment than with oral corticosteroids. Systemic effects include Cushing’s syndrome, Cushingoid features, adrenal suppression, decrease in bone mineral density, cataract and glaucoma. Potential effects on bone density should be considered particularly in patients on high doses for prolonged periods that have co existing risk factors for osteoporosis. Visual disturbances: May be reported with systemic and topical corticosteroid use. If patient presents symptoms such as blurred vision or other visual disturbances, consider ophthalmologist referral for evaluation of possible causes which may include cataract, glaucoma or rare diseases such as central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR). Transfer from oral therapy: Care is needed in patients transferring from oral steroids, since they may remain at risk of impaired adrenal function for a considerable time. Patients who have required high dose corticosteroid therapy or prolonged treatment at the highest recommended dose of inhaled corticosteroids, may also be at risk. These patients may exhibit signs and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency when exposed to severe stress. Additional systemic corticosteroid cover should be considered during periods of stress or elective surgery. Pneumonia in patients with COPD: An increase in the incidence of pneumonia, including pneumonia requiring hospitalisation, has been observed in patients with COPD receiving inhaled corticosteroids. Remain vigilant for the possible development of pneumonia in patients with COPD as the clinical features of such infections overlap with the symptoms of COPD exacerbations. Risk factors for pneumonia include current smoking, older age, low body mass index (BMI) and severe COPD. Hypokalaemia: Potentially serious hypokalaemia may result from ß2-agonist therapy. This has potential to produce adverse cardiovascular effects. Caution is advised in severe COPD as this effect may be potentiated by hypoxia. Hypokalaemia may also be potentiated by concomitant treatment with other medicinal products which can induce hypokalaemia, such as xanthine derivatives, steroids and diuretics.

Hyperglycaemia: Inhalation of high doses of ß2-adrenergic agonists may produce increases in plasma glucose. Blood glucose should be monitored during treatment following established guidelines in patients with diabetes. Co-existing conditions: Use with caution in patients with thyrotoxicosis. Anticholinergic activity: Due to anticholinergic activity, use with caution in patients with symptomatic prostatic hyperplasia, urinary retention or with narrow-angle glaucoma. Patients should be informed about the signs and symptoms of acute narrow-angle glaucoma and should be informed to stop using this medicinal product and to contact their doctor immediately should any of these signs or symptoms develop. Co-administration of this medicinal product with other anticholinergic containing medicinal products is not recommended. Renal impairment: Patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance of <30 mL/min), including those with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, should only be treated with this medicinal product if the expected benefit outweighs the potential risk. Hepatic impairment: In patients with severe hepatic impairment, use only if the expected benefit outweighs the potential risk. These patients should be monitored for potential adverse reactions..

Drug Interactions: Co-treatment with strong CYP3A inhibitors, e.g. itraconazole, ketoconazole, HIV protease inhibitors and cobicistat-containing products are expected to increase the risk of systemic side effects. Should be avoided unless the benefit outweighs the increased risk, in which case patients should be monitored for systemic corticosteroid adverse reactions. This is of limited clinical importance for short-term (1-2 weeks) treatment. Since glycopyrronium is eliminated mainly by the renal route, drug interaction could potentially occur with medicinal products affecting renal excretion mechanisms. Other antimuscarinics and sympathomimetics: Co-administration with other anticholinergic and/or long-acting ß2-adrenergic agonist containing medicinal products is not recommended as it may potentiate known inhaled muscarinic antagonist or ß2-adrenergic agonist adverse reactions. Concomitant use of other beta-adrenergic medicinal products can have potentially additive effects. Caution required when prescribed concomitantly with formoterol.

Medicinal product-induced hypokalaemia: Possible initial hypokalaemia may be

potentiated by xanthine derivatives, steroids and non potassium sparing diuretics. Hypokalaemia may increase the disposition towards arrhythmias in patients who are treated with digitalis glycosides. β-adrenergic blockers: ß-adrenergic blockers (including eye drops) can weaken or inhibit the effect of formoterol. Concurrent use of ß-adrenergic blockers should be avoided unless the expected benefit outweighs the potential risk. If required, cardio-selective ß-adrenergic blockers are preferred. Other pharmacodynamic interactions: Concomitant treatment with quinidine, disopyramide, procainamide, antihistamines, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants and phenothiazines can prolong QT interval and increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias. L-dopa, L-thyroxine, oxytocin and alcohol can impair cardiac tolerance towards beta2-sympathomimetics. Concomitant treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, including medicinal products with similar properties such as furazolidone and procarbazine, may precipitate hypertensive reactions. Elevated risk of arrhythmias in patients receiving concomitant anaesthesia with halogenated hydrocarbons.

Pregnancy and Lactation: Administration to pregnant women/women who are breast-feeding should only be considered if the expected benefit to the mother justifies the potential risk to the foetus/child.

Ability to Drive and Use Machines: Dizziness is an uncommon side effect which should be taken into account.

Undesirable Events: Consult SmPC for a full list of side effects. Common (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10): Oral candidiasis, pneumonia, hyperglycaemia, anxiety, insomnia, headache, palpitations, dysphonia, cough, nausea, muscle spasms, urinary tract infection. Uncommon (≥ 1/1,000 to < 1/100): Hypersensitivity, depression, agitation, restlessness, nervousness, dizziness, tremor, angina pectoris, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardia and extrasystoles), throat irritation, bronchospasm, dry mouth, bruising, urinary retention, chest pain. Very Rare (< 1/10,000): Signs or symptoms of systemic glucocorticosteroid effects, e.g. hypofunction of the adrenal gland, abnormal behaviour. Not known: Angioedema, vision blurred, cataract, glaucoma.

Legal Category: Product subject to prescription which may be renewed (B)

Marketing Authorisation Number: EU/1/20/1498/002 120 actuations

Marketing Authorisation Holder: AstraZeneca AB, SE-151 85, Södertälje, Sweden. Further product information available on request from: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals (Ireland) DAC, Block B, Liffey Valley Office Campus, Dublin 22. Tel: +353 1 609 7100.

TRIXEO and AEROSPHERE are trademarks of the AstraZeneca group of companies.

Date of API preparation: 10/2021

Veeva ID: IE-3166

Adverse events should be reported directly to; HPRA Pharmacovigilance, Website: www.hpra.ie Adverse events should also be reported to AstraZeneca Patient Safety on Freephone 1800 800 899

1. TRIXEO AEROSPHERE 5 micrograms/7.2 micrograms/160 micrograms pressurised inhalation, suspension. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at www.medicines.ie

2. Rabe KF et al. Triple inhaled therapy at two glucocorticoid doses in modeate-tovery-severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:35–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916046

COPD. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:35–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916046

Veeva ID: IE-3706 Date of Preparation: March 2022

NEW NEW

Bringing the focus back to day-to-day respiratory care

not afford to pay for the cost of getting a new prescription. A further 16 per cent of parents/ guardians reported having had to forgo other essential items in order to purchase their children’s asthma medications.

Welcome to the latest edition of Update Respiratory Medicine.

Asthma awareness week took place earlier this month and saw the publication of a new survey by the Asthma Society of Ireland, which focused on the experience of children with asthma – revealing some concerning findings.

One-in-10 children in Ireland have asthma and one-in-five will develop it at some point in their childhood. There are a number of factors that are key to making Ireland an ‘asthma-safe country’ for children, according to the Society, which include timely access to appropriate healthcare, affordable asthma medication, and support for parents and children to learn more about the illness and to build self-management skills.

However, the Society’s survey of Irish parents or guardians about their children’s asthma found that 73 per cent of surveyed parents have experienced anxiety around managing their child’s asthma and 28 per cent indicated they experienced this anxiety ‘always or often’.

The survey also found that 20 per cent of children with asthma worry always or often about having an attack, and the same number worry always or often about having to take their medication in public.

Worryingly, just over a quarter (26 per cent) of parents struggle with the cost of their child’s asthma medications – 5 per cent said they have forgone buying their child’s asthma medications as they could not afford the medication or device, while 5 per cent had forgone buying their child’s medication because they could

Rationing or forgoing asthma medication can lead to a serious exacerbation of symptoms, which can escalate to a dangerous asthma attack. The Asthma Society has been calling for the inclusion of asthma medications on the HSE’s Long-Term Illness Scheme since the organisation’s inception in 1973, but successive governments have refused to update the scheme.

The Society’s survey also highlighted the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on asthma in children – 19 per cent of respondents reported avoiding or delaying going to hospital for their child’s asthma due to fears of them contracting Covid-19, while almost 59 per cent of respondents reported being unsure whether their child’s symptoms were caused by asthma or Covid-19. As a result, almost 16 per cent reported that this uncertainty resulted in a delay in appropriate treatment for the child.

Commenting on the findings, Sarah O’Connor, CEO of the Asthma Society of Ireland, said: “When we looked at the survey results, they really do speak volumes about Ireland’s status as an ‘asthma-safe’ country for children. In a year when the paediatric Model of Care for asthma is being developed by the HSE, we believe it is imperative to note that Ireland is not currently an ‘asthma-safe country’ for children.”

To coincide with asthma awareness week, this edition of Update has a special focus on asthma, with articles on asthma in women, asthma in children, and an overview of the HSE’s new end-to-end Model of Care for Adult Asthma.

There is also an update from the Irish Lung Fibrosis Association, an overview of an

innovative singing exercise programme for pulmonary fibrosis, as well as expert clinical articles on the latest 2022 COPD GOLD guidelines and the latest approaches to managing allergic rhinitis, as well as an update on the roll-out of the HSE’s pulmonary rehabilitation teams for COPD, and an interview with one of the clinicians behind important new Covid-19related Irish research. Speaking of Covid-19, this edition of Update features an expert overview of the role of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients suffering from long Covid, which is an issue that will unfortunately be with us for the foreseeable future and clearly needs more resources to support these patients and their clinicians.

In addition, there is a brief look at continuing international and national efforts to tackle TB, which remains one of the world’s biggest infectious causes of mortality and morbidity and is on the rise again following the impact of the pandemic.

Also returning to our shores this past winter after a brief disappearance was influenza, with this edition containing a summary of the latest data on cases to-date and vaccination uptake in older adults.

Finally, there is a meeting report on Cystic Fibrosis Ireland’s 2022 Annual Conference, which heard about the very positive impacts the latest treatments for this disease are having.

So all-in-all, this is a packed issue that should hopefully prove interesting and useful to all our readers. Thank you to all our expert contributors for taking the time to share their knowledge and advice for the betterment of patient care.

We always welcome new contributors and suggestions for future content, as well as any feedback on our content to-date. Please contact me at priscilla@mindo.ie if you wish to give any feedback or contribute an article. ■

1 Respiratory Medicine | Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022

A message from Priscilla Lynch, Editor

28 Pulmonary

32 SingStrong: Singing for pulmonary fibrosis

Editor Priscilla Lynch priscilla@mindo.ie

Sub-editor Emer Keogh emer@greenx.ie

Creative Director Laura Kenny laura@greenx.ie

34 Irish Lung Fibrosis Association update

36 Cystic Fibrosis Ireland 2022 Annual Conference report 39 Influenza in Ireland –the

Battling TB –

Advertisements Graham Cooke graham@greenx.ie Administration Daiva Maciunaite daiva@greenx.ie

Update is published by GreenCross Publishing Ltd, Top Floor, 111 Rathmines Road Lower, Dublin 6 Tel +353 (0)1 441 0024 greencrosspublishing.ie

© Copyright GreenCross Publishing Ltd 2022

The contents of Update are protected by copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means – electronic, mechanical or photocopy recording or otherwise – whole or in part, in any form whatsoever for advertising or promotional purposes without the prior written permission of the editor or publisher.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in Update are not necessarily those of the publishers, editor or editorial advisory board. While the publishers, editor and editorial advisory board have taken every care with regard to accuracy of editorial and advertisement contributions, they cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions contained.

GreenCross Publishing is owned by Graham Cooke graham@greenx.ie

Contents 04 Covid-19 and ARDS: Irish research breakthrough 06 Latest approaches to allergic rhinitis 13 New HSE end-to-end Model of Care for Adult Asthma 14 Asthma in women 16 Asthma in children 19 COPD GOLD 2022 updates 26 HSE COPD pulmonary rehab update

rehab

for long Covid

of

updates from home and abroad

return

flu 40

A new horizon for Covid-19 treatment – Irish research

AUTHOR: Pat Kelly

As the evolving Covid-19 situation continues to move the ground under clinicians and researchers alike, a recent collaboration has provided hope for patients who have become critically ill with the virus, as well as their physicians. Working in partnership, the researchers from the RCSI and Beaumont Hospital in Dublin investigated the efficacy of an anti-inflammatory protein, alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT), to treat Covid-19 patients who have progressed to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

The study is notable for representing a number of ‘firsts’ – it was the first randomised, controlled trial of AAT for ARDS; the first randomised, controlled trial of AAT in the ICU; and it was the first trial of its kind of a Covid-19 therapeutic in Ireland. In designing the trial, the authors were acutely aware that treatment options for Covid-19 patients with ARDS are particularly limited.

AAT is a naturally occurring human protein that is produced by the liver and released into the bloodstream. AAT normally acts to protect the lungs from the destructive effects of common illnesses. In this trial, the researchers used AAT that had been purified from the blood of healthy donors in an effort to reduce inflammation in severely ill patients with ARDS associated with Covid-19. Overall, the results showed that treatment with AAT led to decreased inflammation after just one week and was safe and well tolerated. In addition, the treatment did not interfere with the patients’ own protective response to Covid-19.

Potential

Prof Gerry McElvaney of the RCSI Department of Medicine and Beaumont

Hospital, Dublin, is a senior author of the new research, which has been published in Med. He spoke with Update about the potential for this treatment approach to save lives and add a new option to the treatment armament of physicians dealing with these extremely vulnerable patients.

“From the very beginning of Covid, we had been working on trying to understand the inflammation in the lungs and the rest of the body that occurred because of Covid infection,” Prof McElvaney, a Consultant Respiratory Physician, explained. “We got a good handle on that. We learned early on that there are certain pro-inflammatory proteins in the blood that were found in Covid infections. We worked on ways of understanding those, because rather than just taking a ‘blanket’ approach and inhibiting those proteins, we wanted to find out what they caused and whether there was a physiological way to inhibit them,” he told Update

“We hit on the idea that although these individuals with severe Covid infection – we are talking about people who are on ventilators, for example –although they had a good, robust antiinflammatory response, in some cases it wasn’t effective enough to save them. We were working with colleagues in the US initially, and we found that there was a lot more inflammation than we had thought,” he said.

One of the human body’s main antiinflammatory agents is the AAT protein, and this prompted Prof McElvaney and his colleagues to measure the levels of AAT in blood. They found that in people with severe Covid-19 infection, whilst the levels of it were high, they were not sufficiently high enough to protect these patients’ lungs. “This gave us the impetus to design a study whereby we gave extra alpha-1 to people with Covid infection who are on ventilators. The idea was – because we weren’t 100 per cent sure it would work –that we wanted to compare it to placebo, so some people got placebo, and some got alpha-1,” he explained.

In the study, alpha-1 was given in two dosages: As a single once-off intravenous dose, followed by placebo once a week; and in the other group, once a week for four weeks. “We wanted to see whether giving this intravenous alpha-1 would decrease the inflammatory burden in people with Covid-19,” said Prof McElvaney. “Although it was a small study, we also wanted to see if it would have any physiological effect. It was a double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial with a relatively small number of patients, but we powered it; we knew how many people we would have to evaluate to see whether we would get an effect.”

4 Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022 | Respiratory Medicine

Prof Gerry McElvaney

Bonus findings

“We found that the key parameter that we were looking at was the effect of alpha-1 on a specific pro-inflammatory protein called interleukin-6 [IL-6] at day seven,” he continued. “We showed that intravenous alpha-1 decreased IL-6 at day seven, whereas with people given placebo, the IL-6 continued to rise at day seven.” There were unexpected bonus findings associated with the study, Prof McElvaney pointed out. “We also found that alpha-1 had other anti-inflammatory effects too – it actually decreased other proinflammatory cytokines.

“There were two other interesting things arising from that,” he said. “When steroids are administered, they seem to have great effect in inhibiting everything, but alpha-1 seemed to be a bit more selective. It inhibited pro-inflammatory cytokines, but did not inhibit anti-inflammatory cytokines, so this was a quite interesting effect. It gave some indication, but which was not statistically significant, in having an effect on time to extubate.” Prof McElvaney also noted that the alpha-1 used in the study was plasma-purified alpha-1, a protein that has already been used for many years throughout Europe and the US to treat patients with alpha-1 deficiency. “Unfortunately, in Ireland, our health service doesn’t reimburse for that, so we only have a small number of people in Ireland receiving plasma-purified alpha-1 antitrypsin for alpha-1 deficiency; a very small number compared to other countries. But we had a good idea about how it works because of that.”

In addition to its promising potential for Covid-19 treatment, Prof McElvaney’s research opens the door for clinical possibilities in a wider range of conditions. “What we really know is, it’s good in treating inflammation,” he said. “For example, in people with ARDS, even if it is not caused by Covid, theoretically, alpha-1 could work there too.

“There is good US data. Alpha-1 is effective in people with alpha-1 deficiency; it

may also be very useful in people with bronchiectasis or even cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis, where there is a lot of inflammation in the lungs, and we have actually been looking at that. There are a few other conditions [it could be applied to] – there is a very interesting skin condition associated with alpha-1 deficiency called panniculitis. We know that intravenous alpha-1 melts that away; it just cures it straight away, so it could also be used for certain skin conditions. Also, there is a series of conditions called vasculitides, and we know that alpha-1 may have a role in treating some of these vascular diseases as well. So the big ones [conditions] as I see it are in alpha-1 deficiency; ordinary COPD; ARDS, be it Covid- or non-Covid related; bronchiectasis, either cystic fibrosis or non-CF bronchiectasis; and panniculitis or vasculitis.”

into getting reimbursement for those in this country, which to me is bizarre.”

Variants

In the context of Covid-19, is this treatment breakthrough effective across all variants? “The people we looked at specifically were the very sick people,” Prof McElvaney said. “We looked at people on ventilators, for example, but it could be even more effective in people who are not yet on ventilators. We have no data on this, but it may actually even prevent the need for ventilation in some people, if it is given early enough. At that stage, the ‘horse has bolted’ so to speak, so it doesn’t really matter what variant they have. At that point, you are in an extreme situation because your lungs are so inflamed so at that point, the variant is irrelevant.

“Interestingly,” he continued, “alpha-1 may have another effect on Covid – it may also affect the ability of the virus to get into cells. One of the ways by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus gets into cells is that it is modified by a protease inside the cell, and alpha-1 inhibits that protease. So in addition to its anti-inflammatory effect, it may also have an antiviral effect. It is the second-most common protein in the body and it changes according to certain inflammatory processes.

Taken on the whole, the results of this translational research should open the door to reimbursement for alpha-1 as a therapy, Prof McElvaney suggested. “We are falling well behind the rest of Europe in this regard; most European countries pay for this [therapy]. In fact, we are conducting a big study at the moment with alpha-1 groups in Switzerland and Austria and the difference between us and them is that perhaps 50-to-60 per cent of their patients are on intravenous augmentation therapy, and we have less than 5 per cent of our people on it.” This highlights the acute problem in Ireland of gaining reimbursement for rare diseases: “And if you put this in context, even with the superdrugs we have for cystic fibrosis, there was an inordinate amount of effort that went

“We know that in Covid, the patients’ response to severe infection is not only to increase the amount of alpha-1 they have, but also to add certain sugars to it to make it more effective in being anti-inflammatory – there’s just not enough of it.”

Reference

McElvaney OJ, McEvoy NL, Boland F, McElvaney OF, Hogan G, Donnelly K, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous alpha-1 antitrypsin for ARDS secondary to Covid-19. Med (N Y). 2022 Apr 8;3(4):233-248.e6. doi: 10.1016/j. medj.2022.03.001

5 Respiratory Medicine | Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022

We learned early on that there are certain proinflammatory proteins in the blood that were found in Covid infections

Allergic rhinitis in focus

AUTHOR: Dr Iseult Sheehan, Clinical Director, Allergy Ireland (www.allergy-ireland.ie)

CASE REPORT

A 15-year-old boy is brought to our clinic by his mother in July, referred by his GP. He has had significant allergic rhinitis symptoms since early childhood. The symptoms are mainly present from May to August.

His main symptoms include rhinorrhoea, sneezing, nasal congestion associated with pruritis to his nose, palate, and occasionally his arms and legs. He also experiences features of allergic conjunctivitis with itchy, watery eyes, and swelling intermittently.

He has recently been experiencing asthma and eczema flare-ups on high pollen count days.

His symptoms are preventing him from sleeping. In addition, he has just completed his Junior Certificate exams. His ability to concentrate and study was hindered and his exam performance was reduced compared to his mock exams.

His parents are very concerned about his Leaving Certificate exams in three years. He is a motivated student with ambitions to attend university. He has

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common condition with a global impact. In Ireland, at least onein-five people suffer with AR.1 The economic impact is striking. The European Union recently estimated that the indirect cost of undertreated AR on work productivity may cost between €30-50 billion per year.2

The symptoms of AR are often considered to be trivial and as such AR is underdiagnosed and undertreated. However, the burden of this disease is significant with a reduced qualityof-life for these individuals. It has been shown to affect cognitive and psychomotor function and patients describe the impact on sleep as considerably debilitating.

been taking multiple antihistamines daily, which he thinks might be contributing to his fatigue. He is also using an intranasal corticosteroid.

Examination

The boy appeared tired with dark rings under his eyes. He was visibly mouth breathing.

Flexible nasoendoscopy confirmed rhinitis with significantly oedematous turbinates bilaterally. There was increased mucus and visible mucosal pallor. There were no polyps and no septal deviation. Chest and eye examination was normal.

Skin prick testing was performed, which confirmed a strong sensitisation to grass pollen.

Management

Allergen avoidance measures were discussed and daily saline irrigation of the nasal cavity advised. Given the severity of the symptoms, a short course of topical intranasal corticosteroid drops (Betamethasone) was used followed by the commencement of a combination

intranasal corticosteroid and antihistamine spray. Topical mast-cell stabiliser (sodium cromoglycate) eye drops were advised. His symptoms improved and at a review in August he was almost symptom free.

Follow-up

The following year he was commenced on a similar plan from early April. However, on review in early June his symptoms were persistent. A trial of a leukotriene receptor antagonist was commenced, which significantly improved symptom control.

Following the pollen season, he was commenced on sub-lingual grass pollen immunotherapy and tolerated it well. He continued to take immunotherapy daily and the April prior to his exams he recommenced the medication plan as before. His exams went well and he remained asymptomatic throughout. He will continue to take immunotherapy to complete a threeyear treatment plan. As a result, it is expected that he will require less medications to control his allergic rhinitis in the future.

While struggling with AR symptoms, the ability to participate in social and sporting activities is reduced and missed days at work are a feature.

In addition, AR has a worrying impact on a child’s education. Missed or unproductive days at school are common. This becomes particularly apparent during hay fever

season, which coincides with exam time. A UK study of teenagers found that there was a reduction in exam performance for those with seasonal AR compared with other times of the year.3 This is most relevant for Leaving Certificate students and those in university.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that AR affects at least

6 Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022 | Respiratory Medicine

The symptoms of AR are often considered to be trivial and as such AR is underdiagnosed and undertreated

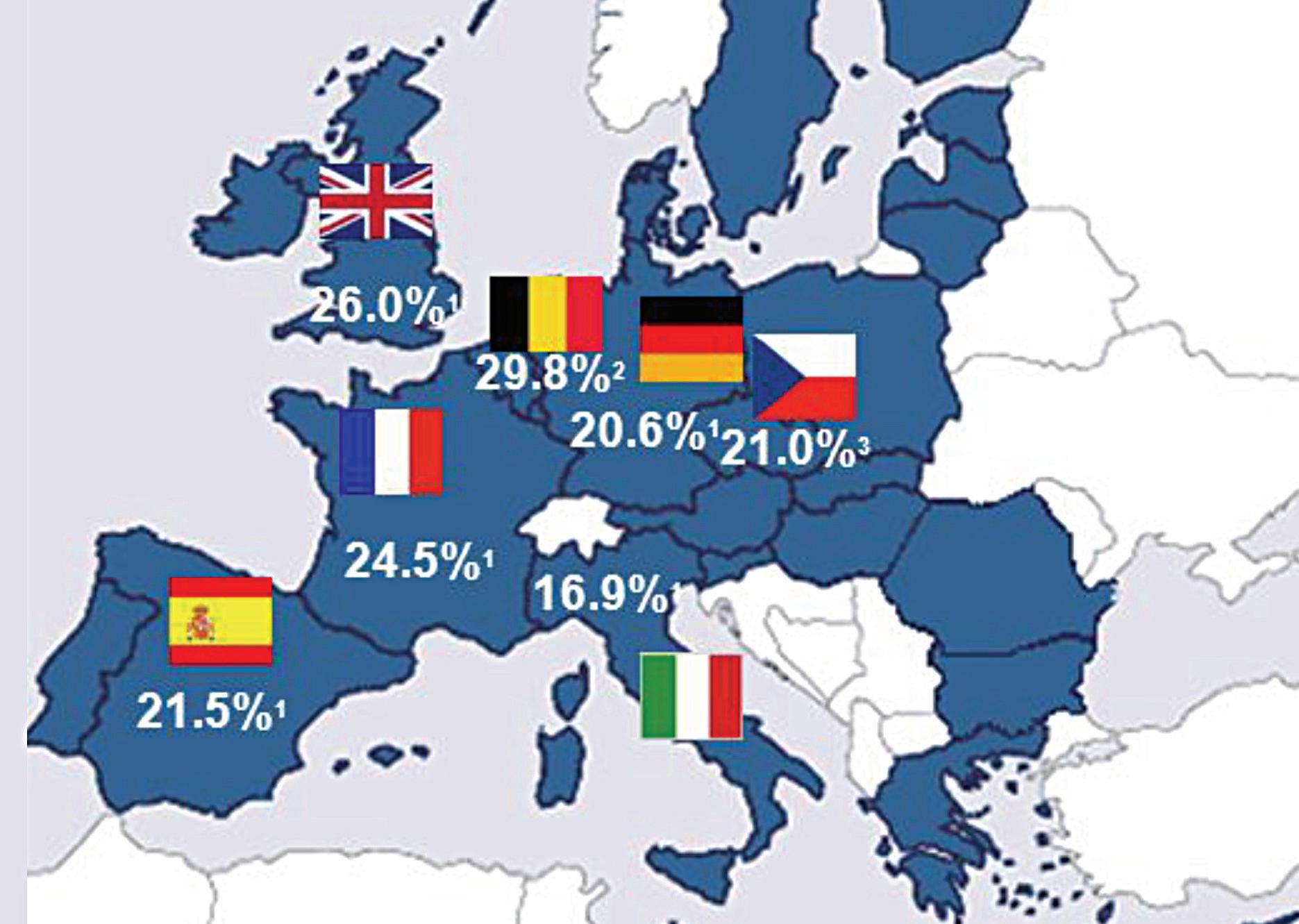

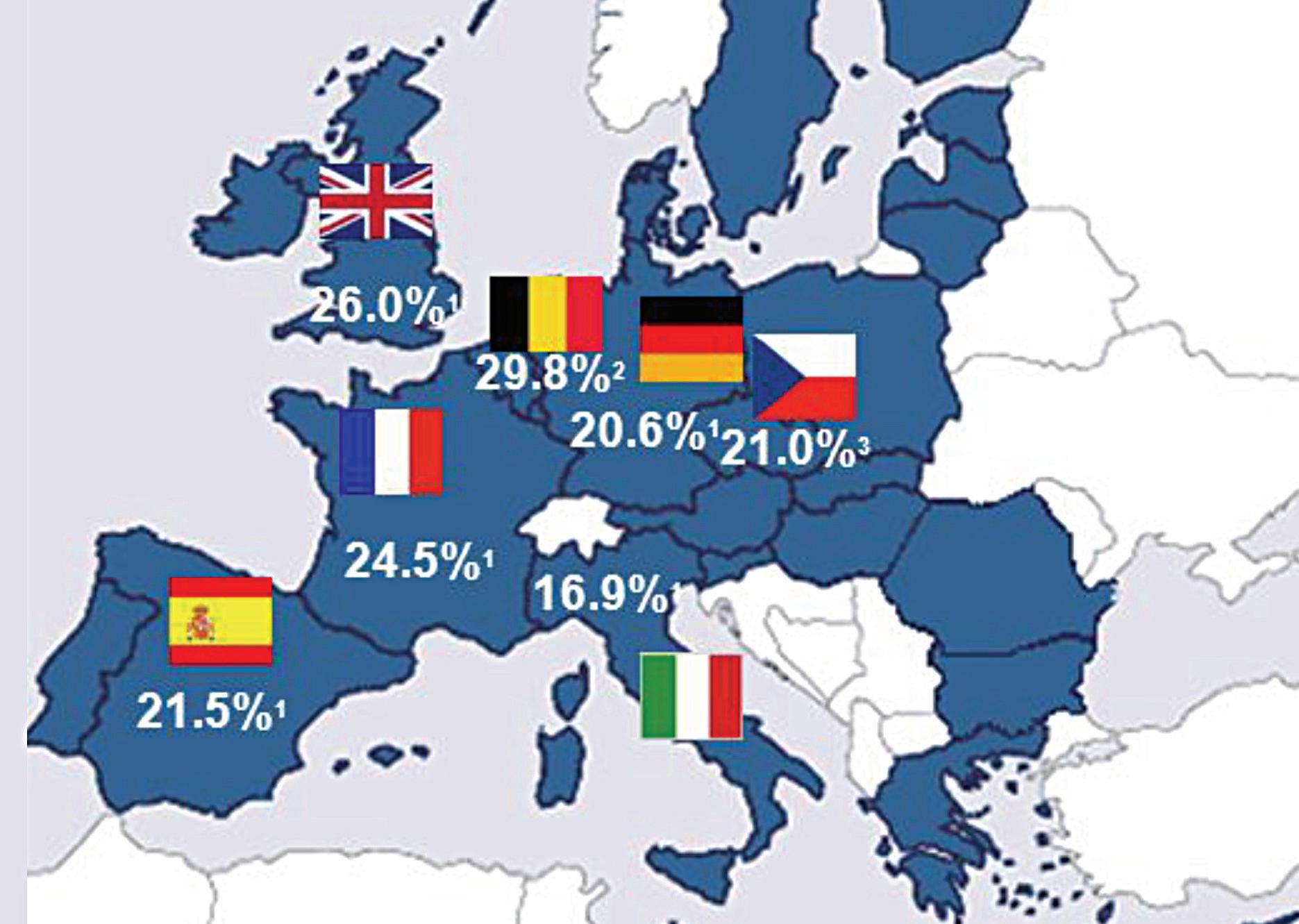

400 million people worldwide and the prevalence within Europe is between 17and-29 per cent.1 The UK has a prevalence of 26 per cent1 and Ireland is likely to be similar to this.

AR will often begin early in life, but prevalence increases with age. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC, 2006) phase 3 study demonstrated this, showing a 5 per cent prevalence in those aged three years, an 8.5 per cent prevalence in those aged six-to-seven years, and a 14.6 per cent prevalence in those aged 13-to-14 years.4

What is most concerning is that the prevalence of AR is increasing globally; as was corroborated by this ISAAC study, which found an increase in prevalence of AR from 13-to-19 per cent over an eight-year period in a cohort of 13-to14 year olds.4 A smaller study in Cork demonstrated an increase in prevalence from 7.6 per cent to 10.6 per cent over a five-year period in a cohort of six-to-nine year olds. 5

Nature versus nurture

The cause for this rising prevalence is unclear, although risk factors may include

overuse of antibiotics, exposure to air pollution, maternal/passive smoking, and climatic factors among other theories.6

Certainly, environmental exposures are key to understanding the rising prevalence of allergies. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ was proposed as an explanation whereby the

more sterile Western lifestyle was reducing infections and resulting in less type 1 immune responses. More recently, there is a better insight into the development of allergen tolerance with the microbiome during early life being an essential component. Antibiotic use will disrupt this, among other environmental factors.

7 Respiratory Medicine | Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022

FIGURE 2: Allergic sensitisation. Adapted from Bousquet et al. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 202010

FIGURE 1: Prevalence of AR in Europe. Adapted from Bauchau et al. Eur Respir J 20041 (Figure from Stallergenes)

Exposure to irritants such as cigarette smoke and air pollution, particularly diesel exhaust fumes, has been shown to contribute to and exacerbate AR.

In addition, global warming is seen to be playing a role in Ireland, with milder weather resulting in prolongation of pollen and spore seasons. This is confounded by the introduction of new pollens such as ragweed, which would usually be a common allergen in North America and continental Europe.

Nevertheless, AR appears to be the consequence of environmental exposures in those with a genetic vulnerability. Indeed, genetic predisposition or atopy accounts for at least 50 per cent of AR cases,7 and genetic

studies have demonstrated that multiple susceptible loci can contribute to AR alone.8

Multimorbid AR

Multimorbid AR is whereby AR and asthma or atopic dermatitis co-exist. Interestingly, a differing variety of genetically susceptible loci are attributable to multimorbid AR, for example, IL-5 and IL-33 for those with AR and asthma. 8

AR is a risk factor for asthma. In fact 90 per cent of asthmatics have AR and 30-to40 per cent of those with AR have asthma.9

A ‘united airways’ disease approach to management is the more favoured approach in recent years. Moreover, the treatment of nasal inflammation in asthmatics has been shown to improve

outcomes. This highlights the importance of assessing for both asthma and rhinitis in these patients.

AR can also be associated with comorbid dermatological conditions, such as atopic dermatitis and urticaria, upon exposure to an allergen. Interestingly, the treatment of AR can very often result in improvements in these dermatological conditions.

Presentation

AR is an IgE-mediated inflammatory reaction following exposure to an allergen. This results in inflammation of the nasal lining and/or conjunctiva. The symptoms characteristically include rhinorrhoea, nasal obstruction, sneezing, and nasal itching.

Additionally, symptoms will often include an itchy palate and irritated, watery itchy eyes with associated periocular oedema or dark rings under the eyes (allergic shiners).

Patients can experience fatigue, snoring, mouth breathing due to nasal obstruction, and a feeling of heaviness in the head or a ‘fuzzy’ head. If the sinuses are affected the patient may experience sinus pressure and headaches and a post-nasal drip.

8 Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022 | Respiratory Medicine

IMAGE 1: Allergic shiners

IMAGE 2: Allergic salute

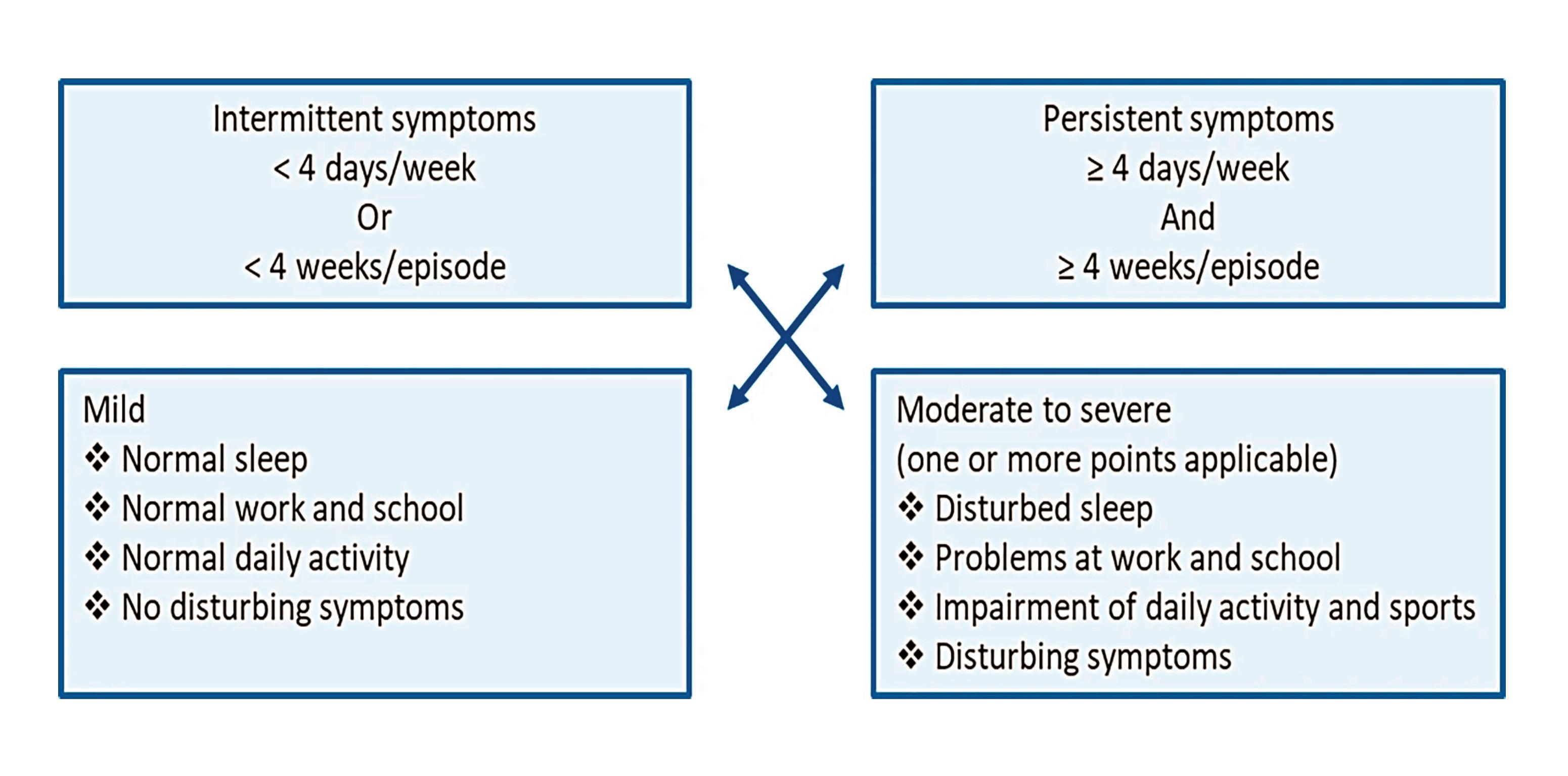

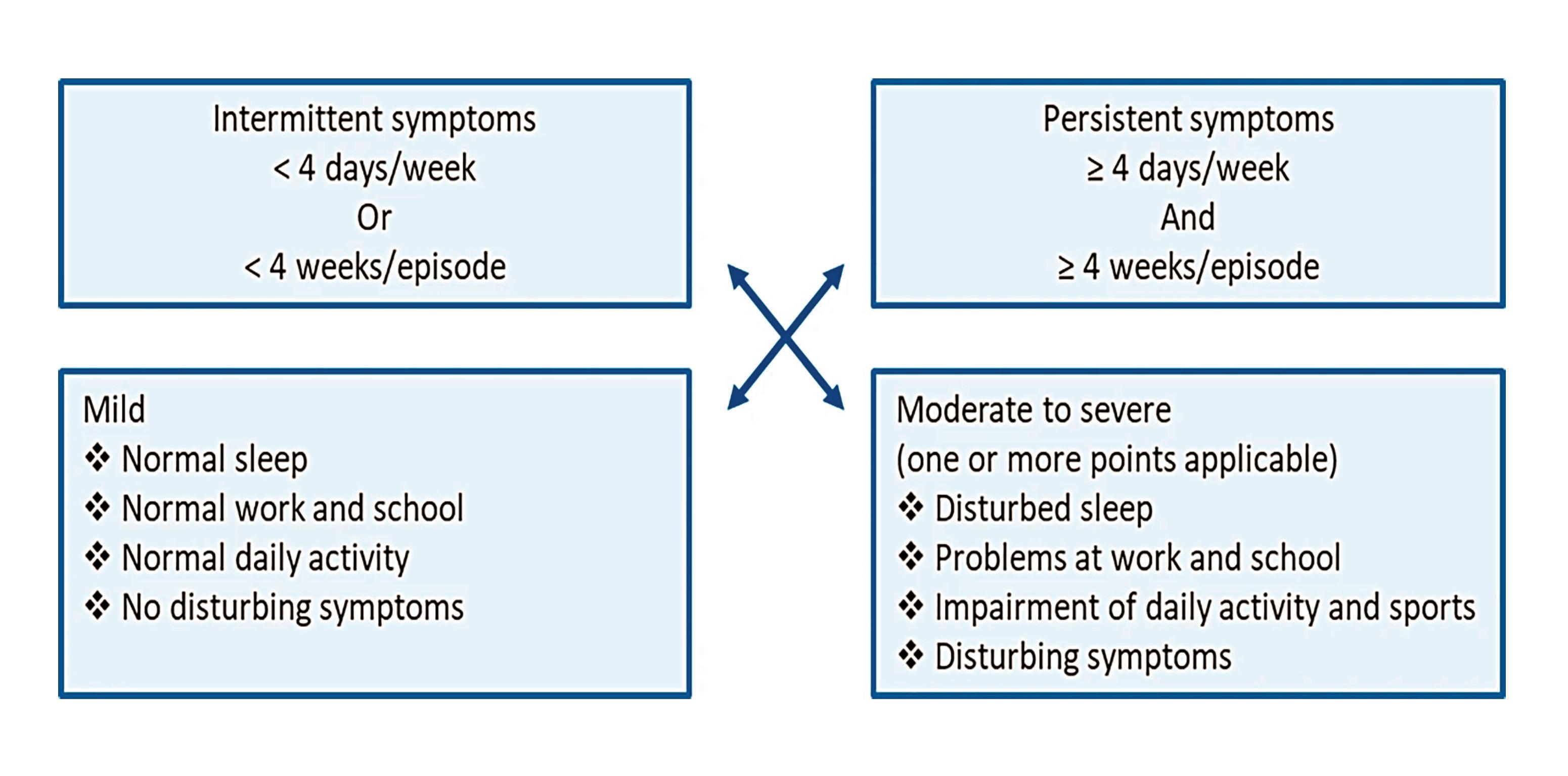

FIGURE 3: AR classification. Adapted from Aria Guideline 20199

120mg and 180mg Film-coated tablets

A NEW generation antihistamine offering non-drowsy, long-lasting relief from allergy symptoms

Abbreviated Prescribing Information

Telfast 120 and 180 mg film-coated tablets

Each tablet contains 120 or 180 mg fexofenadine hydrochloride.

Presentation: Telfast 120 mg: Peach, capsule-shaped, film-coated tablet with 012 on one side and a scripted e on the other side. Telfast 180 mg: Peach, capsule-shaped, film-coated tablet with 018 on one side and a scripted e on the other side. Indications for Telfast 120 mg: Telfast 120 mg is indicated in adults and children 12 years and older for the relief of symptoms associated with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Indications for Telfast 180 mg: Telfast 180 mg is indicated in adults and children 12 years and older for the relief of symptoms associated with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Dosage: Adults and children aged 12 years and over: One tablet once daily before a meal. Not recommended for children under 12 years. Studies in special risk groups (elderly, renally or hepatically impaired patients) indicate that it is not necessary to adjust the dose of fexofenadine hydrochloride in these patients.

Method of administration: Oral. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or any of the excipients. Warnings and precautions: There is limited data in the elderly and renally or hepatically impaired patients. Fexofenadine hydrochloride should be administered with care in these special groups. Patients with a history of or ongoing cardiovascular disease should be warned that, antihistamines as a medicine class, have been associated with the adverse reactions tachycardia and palpitations. Interactions: Fexofenadine does not undergo hepatic biotransformation and therefore will not interact with other medicinal products through hepatic mechanisms. Coadministration of fexofenadine hydrochloride with erythromycin or ketoconazole has been found to result in a 2–3 times increase in the level of fexofenadine in plasma. The changes were not accompanied by any effects on the QT interval and were not associated with any increase in adverse reactions compared to the medicinal products given singly. Animal studies

have shown that the increase in plasma levels of fexofenadine observed after coadministration of erythromycin or ketoconazole, appears to be due to an increase in gastrointestinal absorption and either a decrease in biliary excretion or gastrointestinal secretion, respectively. No interaction between fexofenadine and omeprazole was observed. However, the administration of an antacid containing aluminium and magnesium hydroxide gels 15 minutes prior to fexofenadine hydrochloride caused a reduction in bioavailability, most likely due to binding in the gastrointestinal tract. It is advisable to leave 2 hours between administration of fexofenadine hydrochloride and aluminium and magnesium hydroxide containing antacids. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Fexofenadine hydrochloride should not be used during pregnancy unless clearly necessary. Fexofenadine hydrochloride is not recommended for mothers breast-feeding their babies. No human data on the effect of fexofenadine hydrochloride on fertility are available. In mice, there was no effect on fertility with fexofenadine hydrochloride treatment. Driving and operation of machinery: On the basis of the pharmacodynamic profile and reported adverse reactions it is unlikely that fexofenadine hydrochloride tablets will produce an effect on the ability to drive or use machines. In objective tests, Telfast has been shown to have no significant effects on central nervous system function. This means that patients may drive or perform tasks that require concentration. However, it is advisable to check the individual response before driving or performing complicated tasks. Undesirable effects: Headache, drowsiness, dizziness, nausea. Refer to Summary of Product Characteristics for other undesirable effects. Pack size: 30 tablets. Marketing authorisation holder: Opella Healthcare, 82 Avenue Raspail 94250, Gentilly, France SAS T/A Sanofi. Marketing authorisation number: PA23180/003/002-003. Medicinal product subject to medical prescription. A copy of the SPC is available on request or visit www.clonmelhealthcare.ie. Last revision date: March 2022.

Distributed in Ireland by Clonmel Healthcare Ltd. 2022/ADV/TEL/067H

Compression of the olfactory nerve due to oedema within the nasal cavity can result in an altered sense of smell and/or taste.

Pathophysiology

There are two phases which are paramount to the development of an allergy. Phase one occurs when an atopic individual is first exposed to the allergen. The allergen is taken up by antigen-presenting cells, particularly dendritic cells (DC), and is processed into peptide fragments. The DC will move through the lymphatics towards the lymph node where it will present this peptide fragment to a naïve T-cell.

The naïve T-cell becomes activated to express cytokines, particularly IL-4, which drives the differentiation of these cells to Th2 helper cells. An environment rich in cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 is created and is responsible for inducing IgE production from B-cells. Additionally, IL-5 is responsible for eosinophil recruitment and activation. The cytokine profile is vital as it determines a Th2 immune response.

In the meantime, T-cell dependent activation of B-cells stimulates further cytokine production, particularly IL-4, and promotes irreversible immunoglobulin class switching to allergen-specific IgE antibodies.

Allergen-specific IgE will attach to mast cells and basophils. This is referred to as primary sensitisation. In addition, memory B-cells are generated and a small number of memory T-cells remain.

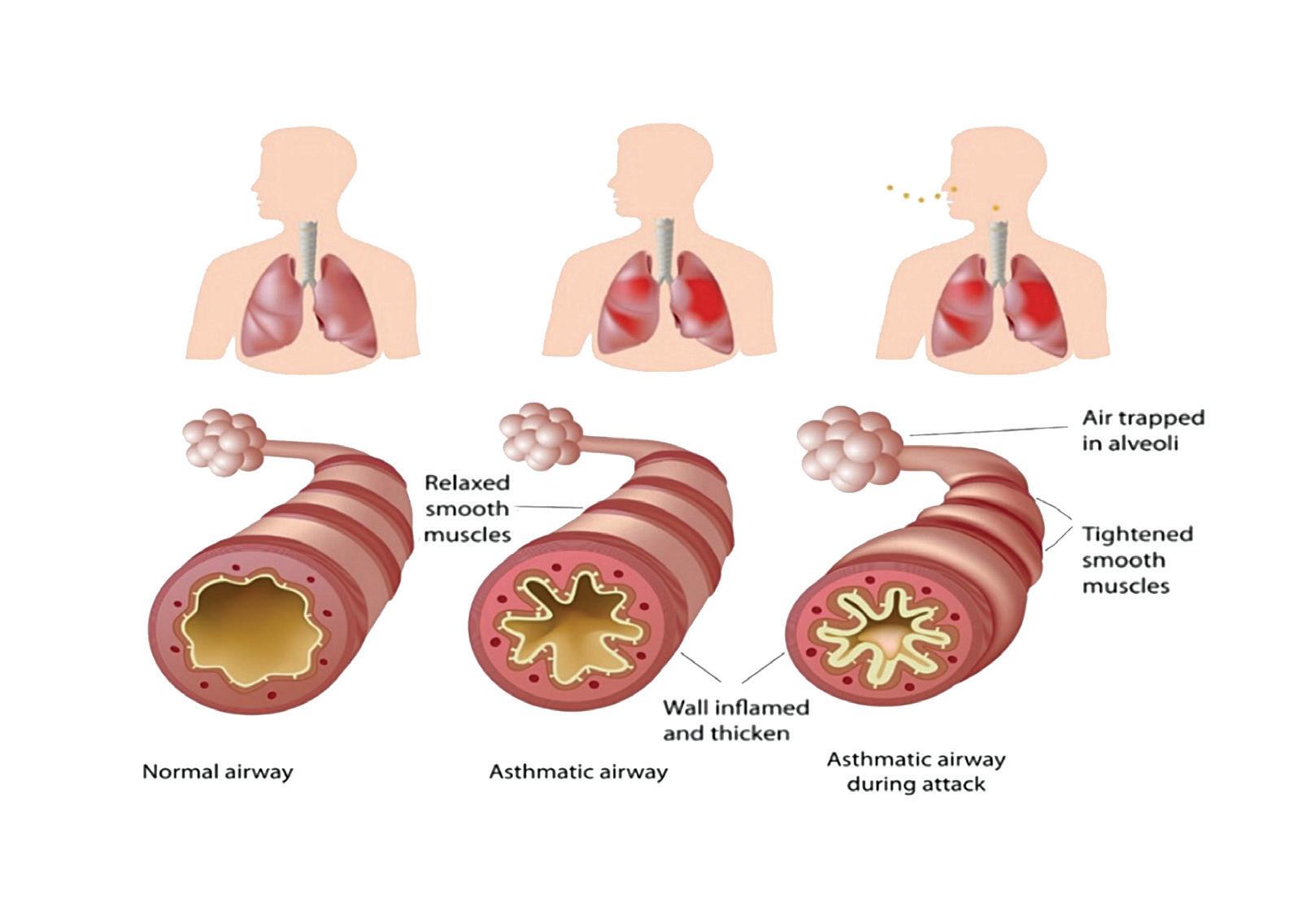

Phase two occurs on subsequent exposure to this allergen. The allergen binds to the sensitised mast cells, triggering degranulation of the mast cell; releasing pre-stored and newly synthesised inflammatory mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins. These contribute to vascular permeability, eosinophil infiltration, and increased mucus production.

Furthermore, with repetitive allergen exposure, nasal priming occurs. This appears to cause an accumulation of

effector cells in the nasal mucosa and results in a hyper-responsiveness to the allergen and prolongation of symptoms. In addition, there appears to be a neural component to this hyper-responsiveness. Changes to the sensory nerves of the nose have been demonstrated in those with AR. In addition, innate immune responses can be initiated in the nasal epithelium by allergens directly compromising the epithelium and resulting in the release of alarmins such as IL-33, further activating the inflammatory response.

Classification of AR

AR can be divided into seasonal and perennial based on allergen triggers. Seasonal rhinitis includes sensitisation to grass, tree, or weed pollen, and fungal spores. Whereas perennial rhinitis is commonly triggered by house dust mite or animal dander. This classification system is effective at giving a likely diagnosis of the trigger, which assists with recommending appropriate avoidance measures.

However, a new classification system focusing on the functional ability of the patient, including the frequency and severity of symptoms, has become a much more effective tool for making treatment decisions. This guideline was developed by Allergic Rhinitis and the Impact on Asthma (ARIA) in collaboration with the World Health Organisation (WHO).9

Diagnosis of AR

The diagnosis of AR is generally based on clinical symptoms. However, skin-prick allergy testing or specific IgE blood testing can be used to confirm the allergen trigger.

In addition, it is vital to examine the nose whereby you will often see bulky oedematous turbinates with visible increased mucus production (Images 3 and 4). Pallor of the mucosal lining is often present, particularly in longstanding cases. Occasionally, the mucosa will lose its smooth appearance and instead will have ridges and pitting from chronic allergic challenge. Pre-polypoid tissue can occasionally be present.

Non-pharmacological management

Allergen avoidance should be discussed. Nevertheless, avoidance alone is generally not sufficient to manage symptoms. In cases where the allergen trigger is animal dander, avoidance is effective if the animal is removed from the home.

Smoking cessation should be advised always. Smoking can be associated with chronic nasal symptoms and may even be associated with the development of polyposis. Passive smoking or ‘vaping’ appear to carry similar risk.

Saline irrigation is an effective way to directly cleanse the nasal cavity with the resultant reduction of mucus, inflammatory mediators, and bacterial burden. It has also been shown to improve mucociliary function.

Pharmacological management

In patients with mild intermittent symptoms an antihistamine is

10 Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022 | Respiratory Medicine

IMAGE 4: Bulky oedematous inferior turbinate with mucosal pallor

IMAGE 3: Normal inferior turbinate

symptom control”1

effective allergic symptom control”1 moderate / severe ic

For moderate / severe allergic rhinitis

Dymista is indicated for the of moderate to severe perennial allergic rhinitis with either intranasal glucocorticoid is not considered sufficient.

tions: Dymista is indicated for the relief of symptoms of moderate to severe seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis if monotherapy with either intranasal antihistamine or glucocorticoid is not considered sufficient.2

INFORMATION:

Dymista (azelastine hydrochloride / fluticasone propionate) 137 micrograms / 50 micrograms per actuation, Nasal Spray, Suspension. Please refer to Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing. Indications, Dosage and Posology: Relief of symptoms of moderate to severe seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis if monotherapy with either intranasal antihistamine or glucocorticoid is not considered sufficient. Posology, For full therapeutic benefit regular usage is essential. Contact with the eyes should be avoided. Adults and adolescents (12 years and older), One actuation in each nostril twice daily (morning and evening). Children below 12 years, Dymista Nasal Spray is not recommended for use in children below 12 years of age as safety and efficacy has not been established in this age group. Elderly, No dose adjustment is required in this population. Renal and hepatic impairment There are no data in patients with renal and hepatic impairment.

Duration of treatment: Dymista Nasal Spray is suitable for long-term use. The duration of treatment should correspond to the period of allergenic exposure. Method of administration: Dymista Nasal Spray is for nasal use only.

For full therapeutic benefit regular usage is essential. Contact children below 12 years of age as safety and efficacy has not only.

Spray must be primed by pressing down and releasing the seconds by tilting it upwards and downwards and the protective protective cap to be replaced. Presentation: Nasal Spray, drug interactions in patients receiving fluticasone propionate to the patient outweighs the risk of systemic corticosteroid corticosteroids and may vary in individual patients and between rarely, a range of psychological or behavioural effects including propionate in patients with severe liver disease is likely to significant adrenal suppression. If there is evidence for higher the lowest dose at which effective control of the symptoms considered whenever other forms of corticosteroid treatment receiving prolonged treatment with nasal corticosteroids is Visual disturbance may be reported with systemic and topical cataract, glaucoma or rare diseases such as central serous and/or cataracts. If there is any reason to believe that adrenal operation or injury to the nose or mouth, the possible benefits contraindication to treatment with Dymista Nasal Spray. Dymista contains plasma concentrations of fluticasone propionate are achieved propionate are unlikely. A drug interaction study in healthy subjects postmarketing use, there have been reports of clinically significant drug expected to increase the risk of systemic side-effects. The other inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4 produce negligible cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors (e.g. ketoconazole), as there is doses have been performed. However, they bear no relevance central nervous medications because sedative effect may are no or limited amount of data from the use of azelastine SmPC) Lactation: It is unknown whether nasally administered newborns/infant. Undesirable effects: Very common (≥1/10): adverse reactions: Reporting suspected adverse reactions via HPRA Pharmacovigilance, Website: www.hpra.ie Adverse renewed (B)

Instruction for use Preparing the spray: The bottle should be shaken gently before use for about 5 seconds by tilting it upwards and downwards and the protective cap be removed afterwards. Prior to first use Dymista Nasal Spray must be primed by pressing down and releasing the pump 6 times. If Dymista Nasal Spray has not been used for more than 7 days it must be reprimed once by pressing down and releasing the pump. Using the spray: The bottle should be shaken gently before use for about 5 seconds by tilting it upwards and downwards and the protective cap be removed afterwards. After blowing the nose the suspension is to be sprayed once into each nostril keeping the head tilted downward (see figure in section 4.2 of the SmPC). After use the spray tip is to be wiped and the protective cap to be replaced. Presentation: Nasal Spray, suspension.

Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substances or to any of the excipients listed in section 6.1 of the SmPC. Warnings and precautions: During post-marketing use, there have been reports of clinically significant drug interactions in patients receiving fluticasone propionate and ritonavir, resulting in systemic corticosteroid effects including Cushing’s syndrome and adrenal suppression. Therefore, concomitant use of fluticasone propionate and ritonavir should be avoided, unless the potential benefit to the patient outweighs the risk of systemic corticosteroid side-effects (see section 4.5 of the SmPC). Systemic effects of nasal corticosteroids may occur, particularly when prescribed at high doses for prolonged periods. These effects are much less likely to occur than with oral corticosteroids and may vary in individual patients and between different corticosteroid preparations. Potential systemic effects may include Cushing’s syndrome, Cushingoid features, adrenal suppression, growth retardation in children and adolescents, cataract, glaucoma and more rarely, a range of psychological or behavioural effects including psychomotor hyperactivity, sleep disorders, anxiety, depression or aggression (particularly in children). Dymista Nasal Spray undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism, therefore the systemic exposure of intranasal fluticasone propionate in patients with severe liver disease is likely to be increased. This may result in a higher frequency of systemic adverse events. Caution is advised when treating these patients. Treatment with higher than recommended doses of nasal corticosteroids may result in clinically significant adrenal suppression. If there is evidence for higher than recommended doses being used, then additional systemic corticosteroid cover should be considered during periods of stress or elective surgery. In general, the dose of intranasal fluticasone formulations should be reduced to the lowest dose at which effective control of the symptoms of rhinitis is maintained. Higher doses than the recommended one (see section 4.2 of the SmPC) have not been tested for Dymista. As with all intranasal corticosteroids, the total systemic burden of corticosteroids should be considered whenever other forms of corticosteroid treatment are prescribed concurrently. Growth retardation has been reported in children receiving nasal corticosteroids at licensed doses. Since Dymista is also given to adolescents, it is recommended that the growth of adolescents receiving prolonged treatment with nasal corticosteroids is regularly monitored, too. If growth is slowed, therapy should be reviewed with the aim of reducing the dose of nasal corticosteroid if possible, to the lowest dose at which effective control of symptoms is maintained. Visual disturbance may be reported with systemic and topical corticosteroid use. If a patient presents with symptoms such as blurred vision or other visual disturbances, the patient should be considered for referral to an ophthalmologist for evaluation of possible causes which may include cataract, glaucoma or rare diseases such as central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) which have been reported after use of systemic and topical corticosteroids. Close monitoring is warranted in patients with a change in vision or with a history of increased ocular pressure, glaucoma and/or cataracts. If there is any reason to believe that adrenal function is impaired, care must be taken when transferring patients from systemic steroid treatment to Dymista Nasal Spray. In patients who have tuberculosis, any type of untreated infection, or have had a recent surgical operation or injury to the nose or mouth, the possible benefits of the treatment with Dymista Nasal Spray should be weighed against possible risk. Infections of the nasal airways should be treated with antibacterial or antimycotical therapy, but do not constitute a specific contraindication to treatment with Dymista Nasal Spray. Dymista contains benzalkonium chloride. Long term use may cause oedema of the nasal mucosa. Interactions with other medicinal products and other forms of interactions: Fluticasone propionate Under normal circumstances, low plasma concentrations of fluticasone propionate are achieved after intranasal dosing, due to extensive first pass metabolism and high systemic clearance mediated by cytochrome P450 3A4 in the gut and liver. Hence, clinically significant drug interactions mediated by fluticasone propionate are unlikely. A drug interaction study in healthy subjects has shown that ritonavir (a highly potent cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitor) can greatly increase fluticasone propionate plasma concentrations, resulting in markedly reduced serum cortisol concentrations. During postmarketing use, there have been reports of clinically significant drug interactions in patients receiving intranasal or inhaled fluticasone propionate and ritonavir, resulting in systemic corticosteroid effects. Co-treatment with other CYP 3A4 inhibitors, including cobicistat-containing products is also expected to increase the risk of systemic side-effects. The combination should be avoided unless the benefit outweighs the increased risk of systemic corticosteroid side-effects, in which case patients should be monitored for systemic corticosteroid side-effects. Studies have shown that other inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4 produce negligible (erythromycin) and minor (ketoconazole) increases in systemic exposure to fluticasone propionate without notable reductions in serum cortisol concentrations. Nevertheless, care is advised when co-administering potent cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors (e.g. ketoconazole), as there is potential for increased systemic exposure to fluticasone propionate. Azelastine hydrochloride No specific interaction studies with azelastine hydrochloride nasal spray have been performed. Interaction studies at high oral doses have been performed. However, they bear no relevance to azelastine nasal spray as given recommended nasal doses result in much lower systemic exposure. Nevertheless, care should be taken when administering azelastine hydrochloride in patients taking concurrent sedative or central nervous medications because sedative effect may be enhanced. Alcohol may also enhance this effect (see section 4.7 of the SmPC). Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Fertility: There are only limited data with regard to fertility (see section 5.3 of the SmPC). Pregnancy: There are no or limited amount of data from the use of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate in pregnant women. Therefore, Dymista Nasal Spray should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the foetus (see section 5.3 of the SmPC) Lactation: It is unknown whether nasally administered azelastine hydrochloride/metabolites or fluticasone propionate/metabolites are excreted in human breast milk. Dymista Nasal Spray should be used during lactation only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the newborns/infant. Undesirable effects: Very common (≥1/10): Epistaxis Common (>1/100, <1/10): Headache, dysgeusia (unpleasant taste), unpleasant smell For details of uncommon, rare and very rarely reported adverse events and those of unknown frequency, see SmPC. Reporting of adverse reactions: Reporting suspected adverse reactions after authorisation of the medicinal product is important. It allows continued monitoring of the benefit/risk balance of the medicinal product. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions via HPRA Pharmacovigilance, Website: www.hpra.ie Adverse reactions/events should also be reported to the marketing authorisation holder at the email address: pv.ireland@viatris.com or phone 0044(0)8001218267. Legal Category: Product subject to prescription which may be renewed (B)

Summary of Product Characteristics.

ine Hydrochloride/Fluticasone Propionate

“Provides effective allergic rhinitis

Job code: DYM-2022-0025 Date of Preparation : February 2022 Viatris.com For more information, please refer to Summary of Product Characteristics References: 1. Meltzer E et al. Clinically relevant effect of a new intranasal therapy (MP29-02) in allergic rhinitis assessed by responder analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;161(4):369–77. 2. Dymista Nasal Spray Summary of Product Characteristics. ABBREVIATED PRESCRIBING

Marketing Authorisation Number: PA2010/059/001 Marketing Authorisation Holder: Mylan IRE Healthcare Limited, Unit 35/36, Grange Parade, Baldoyle Industrial Estate, Dublin 13, Ireland Full Prescribing Information available on request from: Viatris, Dublin 17. Phone 01 8322250. Date of revision of Abbreviated Prescribing Information: 10 Nov 2021 Reference Number: IE-AbPI-Dymista-v003

often effective. Second-generation antihistamines are recommended as they carry less cholinergic and sedating side-effects. Oral or nasal decongestants can be used as a rescue medication, but for no longer than five days to avoid rebound symptoms.

The ARIA guideline recommends intranasal corticosteroids as the firstline treatment for moderate-to-severe intermittent or persistent AR.9 A low bioavailability is recommended and so newer generation intranasal corticosteroids are preferred.

If the nasal cavity is very obstructed, a nasal spray may not be effective until the oedema has been reduced using intranasal corticosteroid drops. Should this not be effective, a combination intranasal treatment is now available combining corticosteroid and antihistamine.

Eye symptoms can be managed conservatively with cold compresses and tear supplements. However, if these

symptoms persist, it is advisable to consider oral and topical antihistamines, topical mast cell stabilisers (sodium cromoglicate), or decongestants. Topical corticosteroids should ideally be prescribed under the care of an ophthalmologist.

If there is evidence of lower airway irritability or asthma, a leukotriene receptor antagonist can be trialled. In severe cases, short courses of oral corticosteroids are occasionally required.

Newer treatment options:

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has been shown to significantly reduce symptoms and medication requirements and is recommended by the ARIA guideline. Additionally, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2020 guideline recommends that immunotherapy be considered for asthmatics sensitised to dust mite.11 Immunotherapy involves exposing a patient to minute quantities of the allergen trigger, allowing the

immune system to build up a tolerance. It is essentially like a vaccination. It can be given as a subcutaneous injection or as a sublingual tablet. Sublingual therapy is used predominantly in Ireland and is currently available for grass pollen, dust mite, and tree pollen. Compliance is crucial and regular follow-up advised. It is usually a three-year process whereby the patient takes it daily. It is highly effective and well-tolerated.

Newer treatment options: Endonasal phototherapy

Phototherapy is well-established for skin conditions and is now being used within the nasal cavity to manage AR. It uses UVA (25 per cent), UVB (<5 per cent) and visible light (70 per cent) to induce a local immunosuppressive effect by inhibiting allergen-induced histamine release from mast cells and inducing apoptosis of T-lymphocytes and eosinophils. It essentially desensitises the nasal cavity, thus reducing symptoms. It is particularly useful when pharmacological treatment is insufficient or contraindicated.

References

1. Bauchau V, Durham SR. Prevalence and rate of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Eur Resp J 2004; 24(5): 758

2. Zuberbier T, Lötvall J, Simoens S, Subramanian SV, Church MK. Economic burden of inadequate management of allergic diseases in the European Union: A GA(2) LEN review. Allergy 2014; 69(10): 1275-9

3. Walker S, Khan-Wasti S, Fletcher M, Cullinan P, Harris J, Sheikh A. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is associated with a detrimental effect on examination performance in United Kingdom teenagers: Case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120(2): 381-7

4. Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the

prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006; 368(9537): 733-43

5. Duggan EM, Sturley J, Fitzgerald AP, Perry IJ, Hourihane JO. The 2002-2007 trends of prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in Irish schoolchildren. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012; 23(5): 464-71

6. Asher MI, Stewart AW, Mallol J, et al. Which population level environmental factors are associated with asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema? Review of the ecological analyses of ISAAC Phase One. Respir Res 2010; 11(1): 8

7. Zacharasiewicz A, Douwes J, Pearce N. What proportion of rhinitis symptoms is attributable to atopy? J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56(4): 385-90

8. Lemonnier N, Melén E, Jiang Y, et al. A novel whole blood gene expression signature for asthma, dermatitis, and rhinitis multimorbidity in children and adolescents. Allergy 2020; 75(12): 3248-60

9. Bousquet J, Schünemann HJ, Togias A, et al. Next-generation allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) guidelines for allergic rhinitis based on grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) and real-world evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145(1): 70-80.e3

10. Bousquet J, Anto JM, Bachert C, et al. Allergic rhinitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020; 6(1): 95

11. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Updated 2020. Available at: https://ginasthma. org/. [Last accessed on 3rd January 2021]

12 Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022 | Respiratory Medicine

The End to End Model of Care for Asthma

AUTHOR: Ms Ruth Morrow, Registered Advanced Nurse Practitioner (Primary Care); Respiratory Nurse Specialist (WhatsApp Messaging Service Asthma Society of Ireland); and Nurse Educator and Consultant

Asthma is the most common chronic respiratory disease in Ireland, with approximately one-in-10 of the population having asthma. Asthma control remains suboptimal in a large proportion of patients, which places significant health, social, and economic burden on the community and on healthcare. The reasons why asthma control remains poor is multi-factorial, but fragmented and unstructured care is believed to be an important contributory factor. The cost of asthma care in Ireland is over €500 million per annum, most of which is in secondary care.

The HSE’s new End to End Model of Care (MOC) for Asthma has been developed in consultation with a wide range of stakeholders including nurses, consultants, GPs, physiotherapists, patients, and patient support organisations. It covers the full spectrum of care provided in both hospital and in the community with a focus on developing partnerships between acute hospital services, general practice and community services, with the patient and his/her family being central to the model. The End to End MOC for adult asthma has been developed in tandem with the HSE strategy for chronic disease management. It outlines the structures that we should adhere to and adopt in the care of patients with, or at risk of, asthma. This MOC is guided by national and international best practice.

The document is not meant to be a guideline document outlining interventions to be used in varied clinical circumstances that present when managing patients with asthma. In this regard the National Clinical Care Programme (NCP) Respiratory endorses the guidelines produced and updated regularly by the Irish Thoracic Society (ITS), the ICGP, and Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). However, the MOC document details how patients should be able to access care at various stages of their asthma and also outlines the roles and

responsibilities of the healthcare professionals (HCPs) providing this healthcare. It is envisaged that the implementation of this MOC will result in a reduction in the variation of care delivered to patients with asthma in Ireland, and additionally result in an improvement in their asthma control, clinical outcomes and quality-of-life.

The MOC seeks, through the implementation of its guidelines, to improve the standard of care provided to adult asthma patients in all healthcare settings, with a particular focus on primary care where the majority of asthma is managed. This MOC will place a particular focus on the ‘at-risk’ patients who are vulnerable to developing asthma and those at risk of experiencing an acute asthma event. This includes those in lower socio-economic groups, smokers, patients with multiple co-morbidities, and those with psychological problems.

The implementation of the MOC aims to ensure that optimum care is delivered using the principles of Sláintecare; so people with asthma receive the right care at the right time in the right place.

The spectrum of services, ranging from primary prevention to tertiary care, includes:

Primary prevention and health promotion.

Risk factor identification and management.

Early detection of asthma and its diagnosis.

Secondary prevention.

Primary care management of asthma.

Shared primary and secondary care management of asthma.

Secondary care management of chronic asthma.

Tertiary care.

In addition to guiding the delivery of the aforementioned objectives, this End to End MOC for adult asthma reflects the key reform themes identified by the HSE to improve the health of the population and to

reshape where and how healthcare services are provided in Ireland. These themes include improving population health, delivering care closer to home, developing specialist hospital care networks, and improving quality, safety, and value.

MOC scope

The scope of this MOC is to define the services required to support the general population of adults in the management of their asthma. It includes health services operated and funded by the HSE and includes community-based services as well as access to hospital-based secondary and tertiary care services if required. It acknowledges that specific health and social care settings, high-risk and vulnerable groups will require additional interventions and support. Working with other relevant national clinical programmes (paediatric and neonatal) and services, this MOC will inform the future development of shared pathways, policies, strategies and services to improve health outcomes in these settings.

Supporting documents include clinical guidelines published by the ICGP, ie, Asthma – Diagnosis, Assessment, and Management in General Practice Quick Reference Guide. The National Clinical Guideline for the Management of an Acute Asthma Attack in Adults (NCEC) is also referred to in this document. International clinical guidelines, such as those from GINA (2021), underpin the diagnosis and management of asthma.

Future development includes the NCP Respiratory collaborating with NCP Paediatrics and Neonatal to form a paediatric working group to develop Part 2: Paediatric Asthma.

Download the End to End MOC at: www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/asthma/ resources/end-to-end-model-of-care-for-asthma.pdf for more information.

13 Respiratory Medicine | Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022

Women and asthma

AUTHOR: Ms Ruth Morrow, Registered Advanced Nurse Practitioner (Primary Care), Respiratory Nurse Specialist (WhatsApp Messaging Service Asthma Society of Ireland), and Nurse Educator and Consultant

During childhood, boys have nearly twice the risk of developing asthma over girls. This changes once children reach the age of 12/13 years. Sex hormones, genetics, social and environmental factors, and responses to asthma treatments are important factors in the sex differences observed in asthma incidence, prevalence, and severity.

In childhood, obesity, regardless of physical fitness, is associated with higher asthma prevalence and morbidity in girls, but not in boys. In girls older than 11 years and women, asthma is five-to-seven times more common in obese people compared to those of normal weight (Koper et al, 2017).

Asthma prevalence is higher in women who have multiple pregnancies, women whose periods started earlier in life, and women with hormonal disturbances such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) (Morales-Estrella et al, 2018). Women who are diagnosed with endometriosis also have an increased risk of asthma. A study by Morales-Estrella et al (2018) showed that 23.8 per cent of women who had endometriosis developed asthma, compared with 13.2 per cent of women who were taking oral contraceptives (OCS).

Testosterone, which increases in boys from the age of 12/13 years, has an antiinflammatory effect in the airways and is thought to be one of the reasons why asthma is less prevalent in boys at this age. Female hormones increase at this age in girls, which is thought to increase the risk of developing asthma and increase symptoms in those who are already diagnosed with asthma.

As adults, women have an increased prevalence and severity of asthma. For women, fluctuations in sex hormone levels during puberty, the menstrual cycle,

pregnancy, and menopause are associated with asthma (Nowrin et al, 2021). Later in life, asthma incidence and severity are higher in women than in men, and highest in women between the fourth and sixth decade of life. During adulthood there is a shift to a female predominance, which affects mainly non-atopic asthma. In the elderly, the gender-related differences decrease. As testosterone levels decrease in older men, the incidence of asthma can also increase in this age group (Koper, 2017).

In addition, pathophysiological abnormalities can be seen, which includes blood eosinophilia which seems to be more prominent in girls with asthma, but in adipose tissue. Girls with asthma tend to have a higher prevalence of noneosinophilic asthma (60 per cent) compared to corresponding boys (30.8 per cent).

Is asthma worse for women?

Severe asthma primarily affects boys before and at school entry age, as well as women around the time of menopause. Women also develop ‘corticosteroid-resistant’ or difficult-to-treat asthma more often than men (Moore et al, 2007).

Studies show that compared to men, women can have worse symptoms more often:

Women are more at risk of acute asthma flare-ups and are admitted to hospital more often with their asthma.

Women who develop asthma for the first time later in life, after menopause, are more likely to have asthma that is difficult to control, and to need specialist care and treatments to help deal with their symptoms.

Lung function starts to decline after about the age of 35 years in both males and females. For women it declines more quickly after the menopause.

Statistics show that women with asthma aged over 65 years are more at risk of lifethreatening asthma attacks.

Women who develop asthma at perimenopause tend to be less atopic, less corticosteroid-responsive, and obese, with steroid refractory asthma (Moore et al, 2007, Wu et al, 2014). These women frequently require high doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) to manage their asthma. Their asthma tends to be difficult to manage and have a higher rate of healthcare utilisation and poorer health outcomes.

Hormones and asthma

Women are more likely to notice worse symptoms around times of hormonal change like puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and perimenopause. Not all women are affected.

One-third of women report worse asthma symptoms before or during a period.

Some women, particularly those with severe asthma, have worse symptoms during pregnancy. Although many women notice an improvement or no change at all when they’re pregnant.

Asthma symptoms can get worse during peri-menopause.

Women who have never had asthma can develop asthma at peri-menopause.

Hormones can be an asthma trigger in their own right, but they can also make the woman more sensitive to other triggers, such as hay fever or colds and flu. It is not yet clear why this is the case. It could be because it increases inflammation in the body and causes inflammation in the airways.

Do women have different asthma triggers?

Women can also have all the same triggers as men, but some of these triggers may be worse for women or affect them more often. For example:

Food allergies are more common in women than men, with female hormones making them worse.

Cigarette smoke can affect women more

14 Volume 8 | Issue 5 | 2022 | Respiratory Medicine

than men. Women and girls may be more sensitive to cigarette smoke and girls with asthma who start to smoke may take longer and need more help to quit.

Stress, anxiety, and depression are more common in women, particularly older women who tend to be carers more often.

Indoor triggers such as cleaning products, cooking fumes and house dust mites, may affect women more as statistics show they’re more likely to be doing the cleaning at home.

How can women lower their asthma risk?

Having an annual asthma review, including assessment of symptoms, checking adherence and inhaler technique, and a review of their asthma ‘Action Plan’ can benefit women. At other times women should be advised that as they approach the peri-menopause, symptoms and asthma control may worsen and they should be advised to have an asthma review with adjustment of treatment if required.

Risk can also be lowered by: