ONE GOOD MASON SAVED – ANOTHER GOOD MASON DEAD

One Good Mason Saved —Another Good Mason Dead Dean S. Clatterbuck, P.M.

I

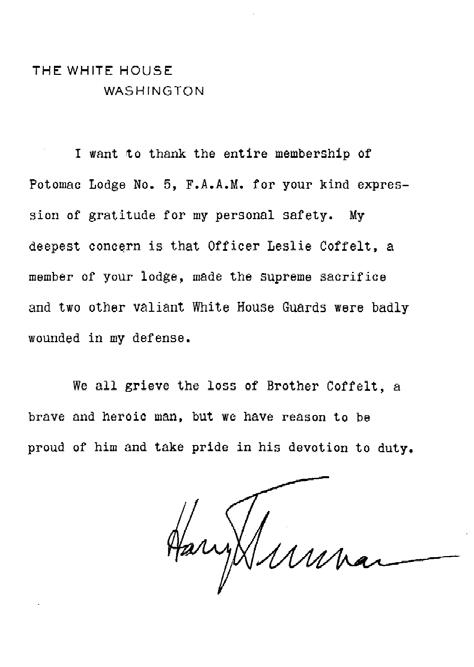

t is Wednesday, November 1, 1950, one hundred fifty years to the day since John Adams became the first president to occupy The White House. Harry S. Truman is the 33rd president of the United States and extensive repairs to The White House have forced the Truman family to move across Pennsylvania Avenue to the Blair House, usually reserved for use as a temporary residence for visiting dignitaries. It will be the home for the president and his family for almost all of his presidency, and will become quickly dubbed, “The Truman White House.” Harry Truman’s schedule for the first of November is a bit lighter than usual and by one o’clock, his appointments concluded, he makes the short trip across the street to Blair House to have lunch with Bess and then catch a nap. Later that afternoon, he is scheduled to travel across the Potomac to nearby Arlington National Cemetery to join the British Ambassador and others in unveiling a statue of Sir John Dill, a British Field Marshall who has died while in Washington on assignment as the senior British representative to the Combined Chiefs of Staff. After lunch, Truman retires to a second floor bedroom at the front of Blair House for a nap. The hour is two o’clock. It won’t be a long nap, for he is scheduled to depart for Arlington National Cemetery at 2:50 p.m. But the next thirty minutes will make that Wednesday a day which Harry Truman will remember for the rest of his life. He would remember it because of an attempted assassination that day on his life by two Puerto Rican nationalists, Griselio Torresola and Oscar Collazo. Griselio, a full time and totally dedicated Puerto Rican Nationalist, had spent time previously in New York, raising money for the cause and to recruit others to the movement. Oscar, also in New York, was such a man. Back in Puerto Rico, on October 30, 1950, an attempt at a coup in San Juan collapsed in a bloody barrage of shots in which the sister of Griselio was shot and captured. Now the cause became personal as well as political. It was time to act; to do something to bring attention to the perceived

plight of Puerto Ricans living under the thumbs of the yanquis. The time was now, and the deed should be something big. Something like assassinating the President of the United States. On October 31, 1950, Oscar and Griselio met at Penn Station in New York City and caught a train to Washington, D.C. They walked from Union Station and within a short distance found themselves at the Hotel Harris on Massachusetts Avenue. N.W., where they registered under assumed names and turned in about ten in the evening. The next morning, they walked from the hotel to the U. S. Capitol and calmly took a tour. Returning to their hotel, they ate lunch, and Griselio gave Oscar some hurried instructions on the use of the weapon Griselio had purchased for him, a Walther P38. Hailing a cab, the men asked to be taken to The White House to see where the president lived. But the cab driver corrected them, telling them that Truman wasn’t living in The White House because it was undergoing renovations — he was living across the street at the Blair House. Upon their arrival in the area of the Blair House, Griselio and Oscar surveyed the situation and re-formulated an improvised plan, not having known about Blair House until minutes before. As they looked over the scene, they could see two White House Police officers in their guard houses, one at either end of the Blair House. One of them was forty-year-old Leslie Coffelt, a native Virginian hailing from a small town outside of Strasburg, who had begun his law enforcement career with the Metropolitan Police Department. He briefly left the force to try his hand at other endeavors, but he was a policeman at heart, and he returned to the force. After eight years, he transferred to the White House Police, the Uniformed Division of the Secret Service (and the forerunner of the Executive Protective Service), where he now had seven years of service as a Private, except for a break to serve in the army during World War II. The Voice of Freemasonry

9