(...the real one!)

WHAT HAPPENED?

The Great Emu War was less of a war, and more of an attempt to manage the rapidly expanding emu population in late 1932. The large birds were decimating farmers’ crops, leading Royal Australian Artillery soldiers to step in and attempt to control their numbers. The Lewis guns (a type of machine gun used in WWI) brought by the soldiers led locals and media to adopt the name “Emu War” when referring to the incident.

While the Australians attempted to figure out how to stop the emus, the emus continued to eat away at their wheat fields. They built their nests in farm territory and created gaps in fences, allowing more emus (and other animals, like rabbits) free reign of the crops.

The Great Emu War ended after about a month, with the government citing the emus’ incredible resilience to gunfire, poor public and press reception of the idea, and the cost of ammunition becoming too high to continue fighting. By the end, soldiers reported that about 1,000 emus were killed. This may seem like a lot—but in terms of the 20,000 emus that were said to have been in the area at the time (and growing), it didn’t make much of a dent in the population.

MAJOR MEREDITH

The Australian soldiers were led by Major Gwynydd Purves Wynne-Aubrey Meredith (shortened to Major Meredith in our show, so your tongue doesn’t get too twisted), and his Sergeant, S. McMurray.

Despite the humilation after being defeated by the emus, Meredith was seemingly impressed by their prowess. He commented on how resilient the birds were, wounded or not, saying: “If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds, it would face any army in the world...”

Emu photograph by Lincoln MacGregor

Major Gwynydd Purves Wynne-Aubrey Meredith

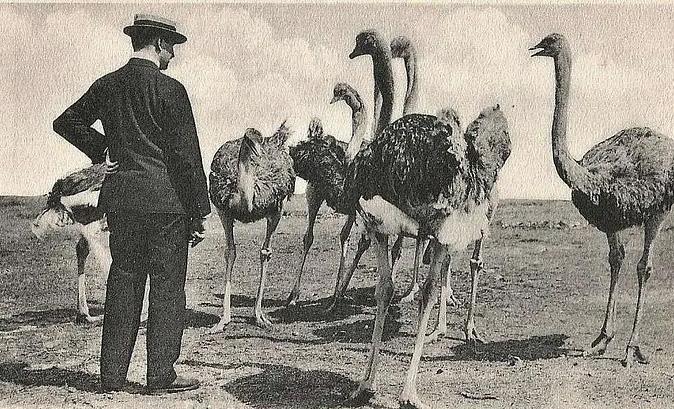

An Australian farmer standing with emus, 1900s.

THE WAR

November 2, 1932

The first day of the war. Australian soldiers attempted to corral the birds in order to ambush them, but the emus split into smaller groups, making them difficult to target.

It is said that no emus were killed in this first battle. Meredith states: “The Emus have suffered no casuaties. We have suffered no casualties.” The war continues.

November 4, 1932

Meredith and his soldiers attempted to ambush the emus again after spotting more than 1,000 heading towards their position. However, the gun jammed after killing just 12 of the birds, and the rest disap peared, not seen again for the rest of the day.

November 8, 1932

Growing more desperate, Meredith attempted to mount one of the guns on a truck and chase the birds. The emus were faster than the truck, and the bumpy outback prevented the gunner from accurately firing shots, leading to the truck breaking down beyond repair. The government called off the war for the time being due to bad press and the cost of the wasted ammunition. Meredith’s official statement: “The men have suffered no casualties, except for their dignity.”

November 12, 1932

The emus continued to destroy wheat fields at an alarming pace. Australian farmers asked for the return of government support, and they sent Meredith and his soldiers back in. They continued to be mostly unsuccessful until early December, when the soldiers found their stride, killing approximately 100 emus per week.

December 10, 1932

The war ended officially when the military was once again withdrawn by the government. Meredith claimed 986 confirmed kills, and 2,500 wounded birds that would likely die from their injuries. Fox Movietone News, who was filming parts of the war in an attempt to use the footage to suppress secessionist sentiment in Western Australia, ended up making Meredith and his army a laughing stock. A motion was even tabled in parliament in Canberra to award medals of valor to the birds.

The First Australian Field Artillery Brigade, WWI.

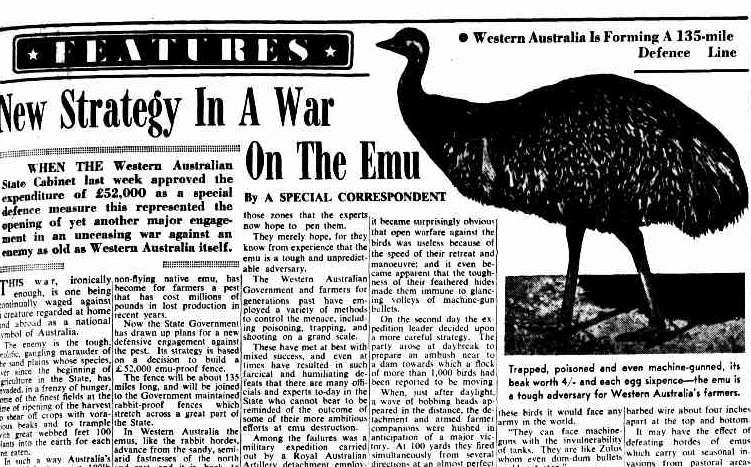

An article from The Sunday Herald, July 1953.

A large group of emus, 1932.