Places might be more than the sum of the instrumental conditions for their existence. Mountain, valley, stream, houses, wind, sun, flora, fauna, people, etc. This uncertain “plus” can be designated as the sense of place, even if contingent and changing.

On the other hand, through the simple use of personal and affective memory, several places may exist under the same “influence” or “aura”, through connections that we can perceive in some of their dimensions: geographical, architectural, social, cultural, symbolic, etc. These “influences” that induce bonds, even if merely symbolic, between geographical places and communities, can generate fertile ground to address the complexity of places and the issue of multiple identities.

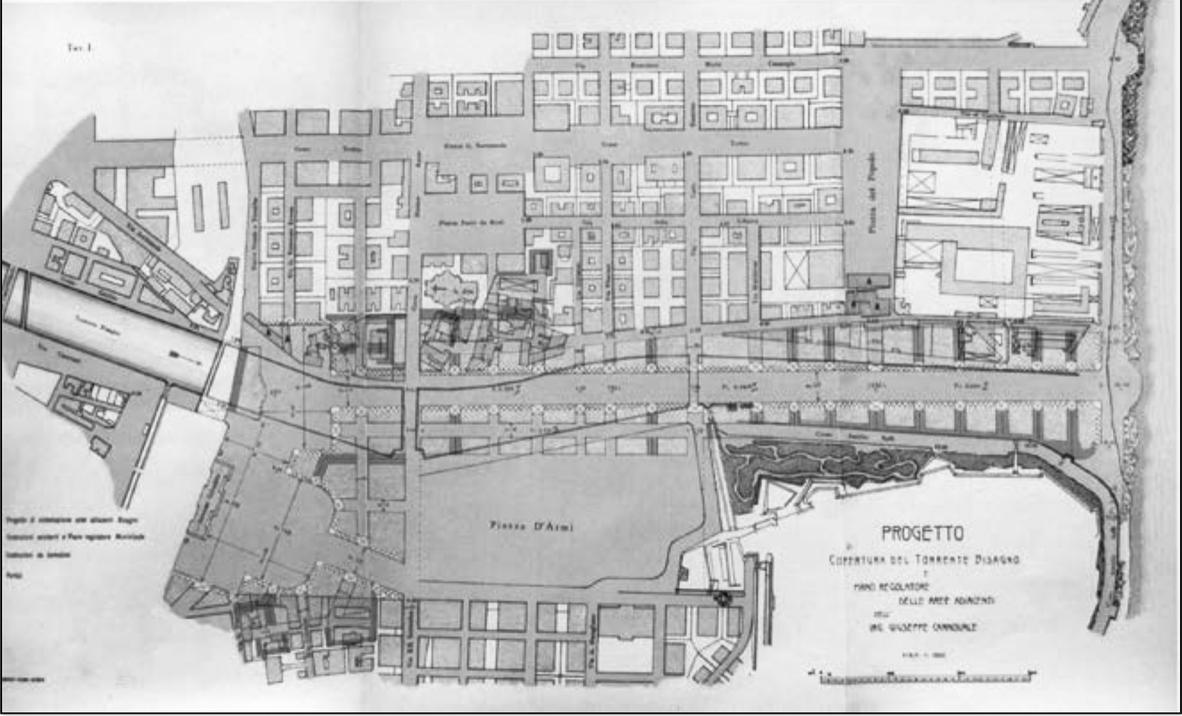

The artistic project “The third river: an imaginary journey between distant waters”, carried out in December 2024, focused on the memory of fluvial contexts, in the wake of a multidisciplinary artistic research that uses orality, historical and geographical information, soundscapes and poetic texts about water, to reflect on the affective impact of rivers and streams from two distinct regions: the Bisagno Torrent, in the province of Genoa (Liguria, Italy) and the Paiva river valley, in the Portuguese region of Viseu Dão Lafões.

Two Rivers, Two Worlds

The Paiva River is a Portuguese river and a left-bank tributary of the Douro River, with an approximate length of 112 km and draining a watershed of 759 km². It originates at an altitude close to 1,000 meters in the Leomil mountain range, in the parish of Pera Velha, near the village of Carapito, in the municipality of Moimenta da Beira. It flows through the territory of ten municipalities, including Moimenta da Beira, Sátão, Vila Nova de Paiva, Viseu, Castro Daire, São Pedro do Sul, Arouca, Cinfães, and Castelo de Paiva, tracing a winding path between the Leomil mountains (to the east), and the S. Lourenço, S. Macário, and Freita mountains (to the south), and Montemuro (to the north).

The Paiva River is renowned for its pristine natural environment, characterized by steep valleys, dense Atlantic forests, and rich biodiversity. Over recent decades, conservation efforts have aimed to protect this ecosystem from the pressures of local development (such as water supply and wastewater management).

The Tramontana network, now in its second year, continues to follow the work of its researchers by collecting and documenting the spiritual heritage of Europe's highland regions, including Albania, Portugal, Italy, Spain, France, Romania, and Poland. While, up to 150 years ago, the mountains served as a refuge for much of Europe's population, today these areas are experiencing significant depopulation, bringing with it the loss of the communities' spiritual and cultural heritage. In the past, life in these regions was marked by large, extended families who, through collective effort, managed to survive in harsh climates and on challenging terrain. Their social solidarity fostered a rich spiritual life, expressed in both joy and sorrow. They were creators and interpreters of their own traditions, sustaining a circular, closed economy where everything was reused or recycled.

From within this rural mountain microcosm emerged a vast cultural wealth: songs, dances, lullabies, and folk chants; handmade costumes woven from wool, richly embroidered with diverse colors and motifs; culinary traditions; agricultural and pastoral practices; unique methods of house construction; and a harmonious relationship with the surrounding landscape. These communities were the true architects of the mountain way of life. Today, however, as younger generations grow increasingly urbanized and disconnected from their roots, this cultural legacy is at risk of being lost. Migration to cities—both within and beyond national borders—has broken the threads of intergenerational transmission, and with them, the continuity of a spiritual heritage shaped over centuries. It is therefore our duty to document and preserve these traditions before they disappear entirely.

These social phenomena are an inevitable consequence of human existence, and the only thing we can do is document as much as possible. This is the core mission of the interdisciplinary and international project Tramontana. The latest meeting took place in Arsita, Abruzzo, Italy, where 11 NGOs from eight European countries gathered to share the work, they had carried out over a 14-month period. The challenges of data collection, translation into English and French, preparation for archiving, cataloguing, and ensuring open access for researchers and artists were among the key topics discussed during the three-day gathering in Arsita.

continued at pg. V

Source: www.tesoridabruzzo.com

Arsita is a small mountain town in the province of Teramo, in the Abruzzo region of central Italy. It lies within the Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga National Park and the upper valley of the Fino River, at an elevation of around 470 meters above sea level. Formerly known as Bacucco until the early 1900s, Arsita preserves strong rural and pastoral traditions, closely tied to the rhythms of mountain life. One of the most important aspects of its cultural identity is transhumance—the seasonal migration of livestock, especially sheep, between mountain and lowland pastures. This ancient practice, recognized by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage, continues in Arsita not only as a historical tradition but also through modern events such as the Transumanza Verticale, where locals and visitors retrace the shepherds’ paths on foot, enjoy traditional mountain cuisine, and take part in outdoor activities like the Corsa del Transumante, a race celebrating the pastoral spirit.

continues from pg. I

These changing climate patterns and human activities continue to challenge the river’s salubrity, prompting ongoing initiatives to balance ecological preservation with sustainable use.

The Bisagno torrent, along with the Polcevera torrent, is one of the main watercourses of Genoa: it crosses the Ligurian capital transversely, giving its name to the homonymous valley. The orographic configuration of the Val Bisagno defines the territorial layout of three municipalities: Genoa, Bargagli, and Davagna. Among its tributaries are the Lentro torrent, Canate torrent, Geirato stream, Torbido stream, Molassana stream, and Fereggiano stream. Its length is approximately 25 km. It flows into the Gulf of Genoa at the neighborhood of San Pietro alla Foce (commonly called simply La Foce).

The Bisagno torrent presents a story of urban transformation and environmental stress. Historically a fastflowing mountain stream, the Bisagno has been heavily modified due to urban

question? Why not relating two distant rivers with different contexts and evolutions, trying to sense possible connections and divergences, through a mix of historical and ethnographic narratives blended with lateral thinking and imagination?

How Was This Project Created?

The project began in December 2024 by picking two places, guided by personal connection and curiosity. Riverscapes became the central theme. Visits to each river meant listening, watching, and collecting sounds, images, and found objects. Meeting locals and recording their stories added depth and personality. Maps, books, and access to both institutional and family archives helped fill in the details. Creativity came into play through experimental collages, sound pieces, and poetic writing. Finally, all these elements were woven into an audiovisual essay — a creative format that can incorporate disparate elements, both factual and poetical.

expansion and industrialization. Its frequent flooding has led to significant engineering interventions, including channelization and containment works. Despite these measures, flooding risks remain, highlighting the tensions between urban development and riverine ecosystem management in a densely populated Mediterranean city.

Why are the Paiva river and the Bisagno torrent being put together? The answer may also be the reverse

Conclusion

The intertwining of place-based artistic practices enables conversations across distant rural communities, weaving together threads of history, memory, and identity in ways that transcend geography. By tapping into historical and oral archives, artists can unlock dynamic repositories of stories, reshaping them through inventive reinterpretation to foster fresh perspectives that reflect the complexities of places and communities, continued at pg. V

Sesion 4.11. Water, upland settlement, and memory: multidisciplinary perspectives on rural history in the 20th century Wednesday, 10th September 2025, Faculty of Arts and Humanities Organisers: Giovanni Agresti, Bordeaux Montaigne University, France

Luis Gomes da Costa, University of Aveiro, Portugal, Eltjana Shkreli, University of Genoa, Italy

As part of the ecosystem in the mountains and highland areas, water is an essential (key) component in the domestic, industrial, and agriculture/livestock economies. Rural livelihoods are dependent on adequate water supply, therefore in most cases, the upland rural communities are settled among the river valleys and streams/springs due to short water distancethe water has dictated settlements’ location, sustainability, and cultural development shaping the patterns of settlement.

This session connects to the work of the TRAMONTANA network, founded in 2011 and the objective is the documentation, cataloguing, restitution, artistic creation, and dissemination of intangible heritage from rural and mountain communities of Europe.

The session explores the intimate and multifaceted relationship between water and European highland rural communities in the 20th century, focusing on how water has influenced settlement formation, the emergence of water cultures shaped by environmental challenges and societal needs, and the evolution of water cultures and management practices that continue to impact rural landscapes today. Besides, the session will also highlight how water practices have shaped the cultural landscape, particularly in mountainous areas where water sources are both scarce and essential.

Settlement patterns in these regions have been intricately linked to the availability of water, resulting in unique cultural landscapes that reflect how humans have shaped and been shaped by their environment. The session will emphasize an interdisciplinary approach to rural history research, focusing on the main methodology of oral history (microhistory) to recover and preserve water cultures and their management practices. Living witnesses, especially elders within rural communities, offer rich, personal accounts of the relationship between water and settlement in the 20th century, providing valuable firsthand perspectives on traditional practices that may be fading due to the abandonment of Highlands and mountain areas. Oral histories could be compared across regions, offering a cross-cultural approach to understanding how water has been a shared, yet regionally adapted, resource in rural upland settings. Ultimately, this session would provide a platform for a multidisciplinary discussion of rural upland water cultures and their enduring legacy in the 20th century and beyond. In light of current global challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity, and rural depopulation, this research is more relevant than ever.

Abstract: Water system in Nikc in one century (Kelmend, Albanian Alps)

Eltjana Shkreli, University of Genoa, Italy

Nikc, an old settlement in the Albanian AA) is situated in Cem Vuklit river valley between mountain ranges, surrounded by water springs at an altitude 6007500m a.s.l. This village belongs to Kelmend tribe territory (AA), and before 1945 traditionally, the water management in this area was regulated by the Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini, the Highland common law that governed various aspects of life, including land use, water resource sharing, run bottom up.

During the totalitarian period (1945-1990) the rules in use changed as everything was state owned and run top-down passing through collectivization of land and flocks. After 90s, the communism collapsed and free market shifted the land ownership and public assets, like water irrigation system abandonned.

This paper aims to provide an overview how water system evolution in Nikc_Kelmend has impacted the settlement pattern in 20th century, based on spatial analysis and oral stories methodologies focusing on traditional water management techniques and irrigation practices. This is important in field as the previous research studies about AA rural landscape and/or its features water has been just a physical resource it has never been integral to the shaping of upland culture, highlanders’ communities, and the very idea territorial belonging.

Years of research in the Albanian Alps have been a source of inspiration and passion to shed light to the values of this region. Their rich natural and cultural resources, viewed alongside different or similar models across Europe and beyond, offer a different perspective. Documenting and interpreting these findings into in-depth scientific analysis has continually driven us to present them in international forums. Most recently, this included the 7th Biennial International Conference “Rural History 2025” in Coimbra, Portugal, organized by the European Rural History Organization and the University of Coimbra. Rural History 2025 aims to continue the positive trend of sharing diverse perspectives on rural and agricultural pasts. The increasing use of historical data is a resource for various disciplines, both for exploring new paths in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research and for informing the development of current policies. These forums raise numerous questions: How do rural and agricultural issues intersect with territorial development and with social, economic, political, institutional, environmental, scientific, or cultural dynamics that have become increasingly important? What is the role of history in building the sustainable solutions we need today? About 500 researchers in 124 parallel sessions discussed a wide range of topics. GO2Albania was the only entity from Albania represented in two sessions. One was co-organizer through Tramontana Network, with the topic “Water, mountain settlement, and memory: multidisciplinary perspectives on the rural history of the 20th century.” In this session, it was presented the irrigation system model in the settlement of Nikç, in Kelmend, in the Albanian Alps—its infrastructure and water-use practices during three historical periods: under customary law, under communism (cooperatives), and in democracy, within the free market.

The topic of the second session was “Comparing agrarian reforms across the 20th century: conflicts and contradictions.” GO2Albania presented the Albanian model, the impacts, and the conflicts generated by agrarian reforms in the Highland communities. The resulting debate became a motivation to further deepen this research and eventually produce a written document based on facts and testimonies. For instance, the recently approved “Mountain Package” Law—passed a few months ago—remains a step that should have been strongly grounded in such analysis; time will show how it will affect mountain communities (with or without social conflict and, consequently, economic impact).

through creative blending, audiovisual essays emerge as an interesting artistic format, challenging conventional storytelling with their layered, experimental forms, inviting audiences to engage with narratives in more immersive and

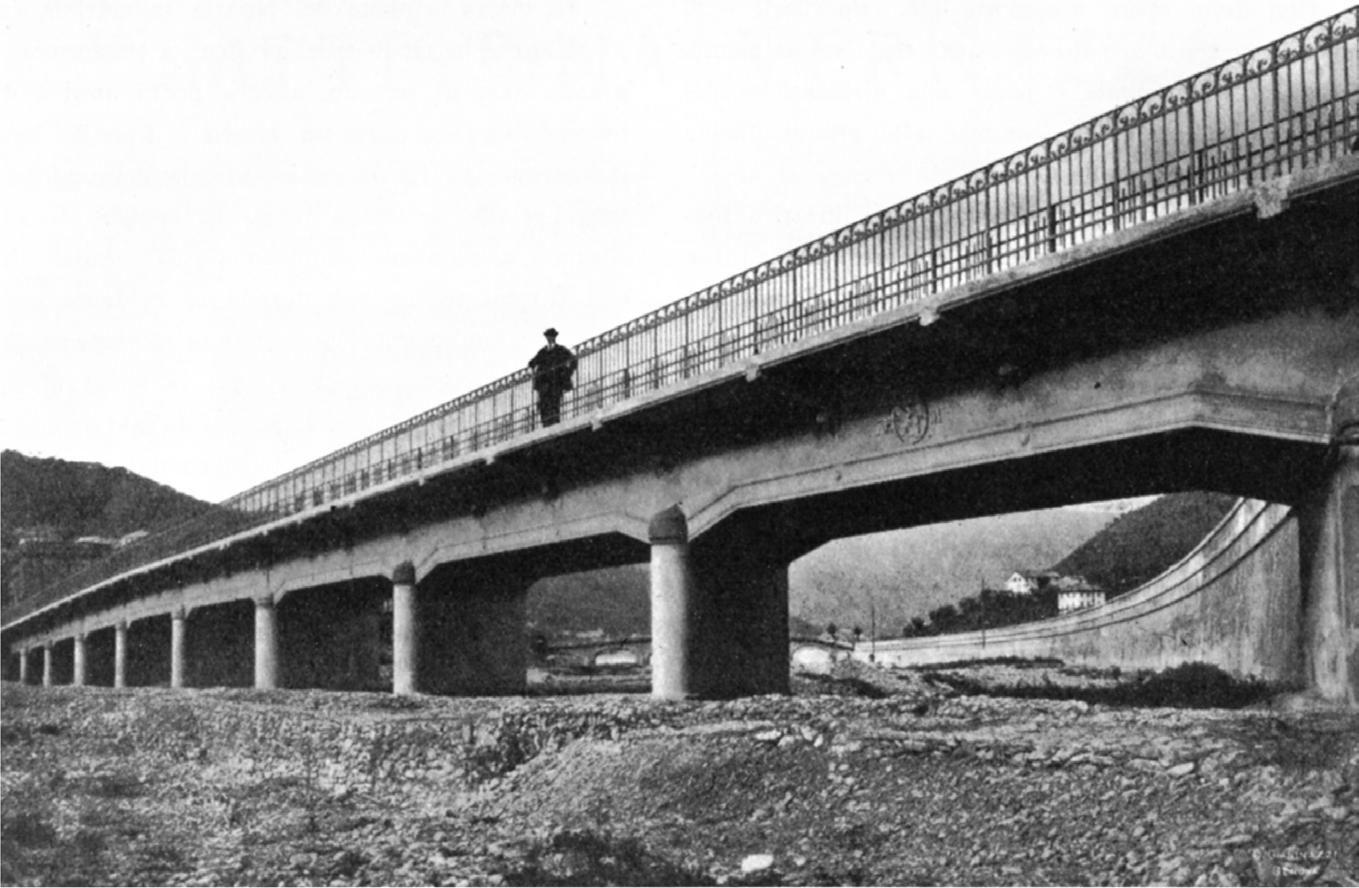

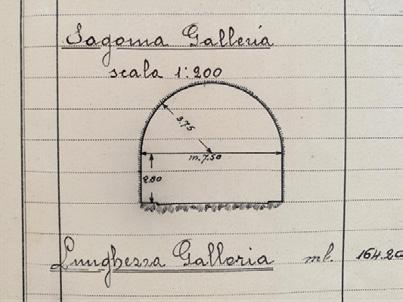

Construction project for the Boasi Tunnel drawn up by the Technical Office of the Province of Genoa on January 16th, 1928.

Source: Historical Archives of the Province of Genoa. Kindly provided by Associazione Amici di Pontecarrega (Genoa)

continues from pg. III multifaceted ways.

Artistic research, positioned at the heart of these explorations, offers profound insights into the intricate relationships between place, memory, and identity, while also addressing pressing ecological concerns, such as in the case of riverscapes. In this way, art can move beyond expression and be a vital tool for deepening our understanding of human experience and environmental interconnectedness across time and space.

Here is the result of “The Third River: An Imaginary Journey between Distant Waters”: https://www. re-tramontana.org/ portfolio-items/thethird-river/

Bibliography

Here are some books and articles that inspired this project: Breakell, S. (2017). Negotiating the archive. Routledge. Corrigan, T. (2011). The essay film: From Montaigne, after Marker. Oxford University Press. De Bono, E. (1970). Lateral thinking: Creativity step by step. Harper & Row. Fauconnier, G., & Turner, M. (2002). The way we think: Conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities. Basic Books. Foster, H. (2004). An archival impulse. October, 110, 3–22. Grant, C. (2016). The audiovisual essay as performative research. Journal of Media Practice, 17(1), 39–52. Martin, A., & Álvarez López, C. (2018). Introduction to the audiovisual essay: A child of two mothers. Studies in Documentary Film, 12(1), 1–16. Oliveira, A., Aguiar Gomes, C., Silva, F., Paiva, J. & Silveira, P. (1999). Rio Paiva. Campo das Letras. Rosso, R. (2014). Bisagno. Il fiume nascosto. Marsilio

continues from pg. II

We met many residents who had built their lives in Arsita and were clearly proud of their heritage, two of them were Albanians coming from Kavaja, Albania, 25 years ago. Their connection to the land, the community, and their cultural legacy formed a kind of sacred triangle of values. The celebration we attended on the final afternoon marked the culmination of over 30 years of work documenting the area's rich heritage of songs, dances, and instrumental music—including the accordion, ciaramella (a type of traditional oboe), organetto, violin, and various handmade instruments.

Two researchers from the Tramontana group— ethnomusicologist Marc Magistrale and anthropologist Gianfranco Spitilli—have formed a symbiotic relationship with the community, preserving and revitalizing the memories of generations. Their work was honored with the inauguration of a museum that day, dedicated to keeping this cultural legacy alive.

At the village restaurant, we sampled the unique cheese called pecorino prepared by stomach enzymes of pigs, traditional dishes such as maccheroni alla molinara (handmade pasta), coatto (lamb stew), and fracchiata (a type of polenta made with chickpea flour and legumes).

Federico, one of the residents, told us about the Feast of Saint Anthony the Abbot in January—a celebration that combines sacred processions with ancient folk rituals. The Church of Santa Vittoria, which dates back to the 16th century, stands as a central symbol of both local faith and architectural heritage.

Every August for the past 31 years, Arsita has hosted the annual Valfino al Canto folk music festival—a vibrant tradition that gathers artists from across Italy and abroad. The event celebrates oral traditions, music, and storytelling through performances, communal meals, and a strong sense of shared identity. More than 5,000 visitors attend, drawn by the authentic spirit of the Abruzzo mountains and the enduring legacy of the people who have lived— and continue to live—there. GO2Albania

The Liri River rises in the lower part of the settlement of Cappadocia. Plunging into a narrow gorge between the Simbruini Mountains and the Nerfa Valley, it reaches Castellafiume, located about a hundred meters lower, where— reinforced by the spring known as Fonte Rio Sonno—it becomes larger and more impetuous before continuing toward the Roveto Valley, passing through the towns of Capistrello, Canistro, Civitella, Civitella d’Antino, Morino, San Vincenzo, and Balsorano. These two valley systems, adjacent to one another and rich in springs, define the area known as the Upper Liri.

It is difficult to trace or contain an anthropology of water. This is due to what can be called the “authoritativeness of water”: not merely a material substance and resource, but an “active subject,” a “creative agent.” An element that generates opposites: source of death/life, ordinary/ extraordinary, sacred/profane, normal/thermal, mythical/scientific, urban/rural, internal/external, contained/containing, immanent/environmental, devotional/medical, pilgrimages/travel, ancestral/modern, banal/miraculous, scientific/ belief-based, scarce/excessive, absent/flooding, used/wasted, utilitarian/anti-utilitarian, masculine/ feminine, conflictual/peace-making, minute/expansive, known/ unknown, visible/subterranean1

As water is universally central to human, biological, and social life, it is endowed with powerful meanings in every cultural context2. Examining how human groups relate to it— using it in both material and symbolic ways—reveals the fluidity of a process situated within the dynamics underlying the relationship between humans and their environment3 Identity, besides residing in kinship structures and forms of social organization, or in concepts

of ethnicity expressed through genealogical and genetic heritage, has in recent anthropological works been linked to the memory of places, especially in small communities far from urban areas.

Until the post-war period, the economy of all the aforementioned towns was closely tied to the waters of the Liri and based on the triad agriculture/pastoralism/forestry. In addition to playing a central role in irrigating fields, the water resource was used to power mills and fulling mills, in paper mills, and more recently in power plants, thus shaping both the natural and human landscape of the region. Furthermore, one of the springs near Canistro, “CotardoFiuggino,” brought prosperity to a bottling plant thanks to its highly regarded organoleptic qualities: Santa Croce mineral water, one of the best-selling in Italy.

In the Upper Liri area, Benedictine monks specialized in engineering works on this important watercourse during the Middle Ages, harnessing it as a productive force and employing much of the local population in the construction of hydraulic works. The mastery of such a powerful natural force represented a significant step for humanity, enabling the notable development of craftsmanship and proto-industries. At the same time, control of water and of the mills became an instrument of power, wealth accumulation, and coercion under feudal rule. Numerous trades emerged around water: fountain keepers responsible for aqueducts, water carriers tasked with drawing water from springs and delivering it to households, sawyers working at hydraulic sawmills, millers engaged in grain milling, paper-makers, and woolworkers operating the fulling mills. The proliferation of social customs and artisanal and architectural knowhow became a driver of technological innovation in other sectors as well.

continued at pg. VII

1) Breda N., Per un’antropologia dell’acqua, in La Ricerca Folklorica, no. 51, Antropologia dell’acqua (Apr.2005), p. 3.

2) Illich I., H2O and the water of forgetfulness, Marion Boyars, New York, 1986; Feld S., A Poetic of Place: ecological and aestetic co-evolution in a Papua New Guinea rainforest community, in R. Ellen and K. Fukui, Redefining Nature: ecology, culture and domestication, Berg, Oxford, 1996, pp. 61-88.

3) Strang V., Fluidscapes: Water, identity and the senses, in Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology, Brill, Leiden, 2006, pp.147-154.

Water. A symbol of life, a source of renewal in the mountains. In the Sudetes it usually means clear streams rushing down slopes, springs feeding valleys, waterfalls drawing walkers and tourists. Yet when the balance is broken, when rain no longer trickles but crashes, water becomes a merciless destroyer.

In September 2024 the Sudetes (Poland) experienced this with brutal force. For days, rain fell without pause. Torrents carved through the Owl Mountains and Bystrzyckie Mountains, swelled the Biała Lądecka, the Bystrzyca, the Bóbr. Valleys turned into brown seas. Embankments burst, bridges vanished. This was no ordinary storm but an assault — water tearing at the very fabric of mountain life, sweeping away roads, houses, and with them the security of local communities.

A Mountain Landscape in Ruins

The Kłodzko Valley bore the heaviest blow. Stronie Śląskie, Lądek-Zdrój, Bystrzyca Kłodzka, and Kłodzko saw their centres drowned. Roads collapsed into rivers, while smaller towns like Międzylesie or Trzebieszowice were cut off entirely. In the Jelenia Góra Basin, floods from the Bóbr surged into villages, covering gardens and schools. Official figures speak of more than 5,200 homes damaged across the Sudetes. Yet statistics disguise the reality: families living for months in relatives’ spare rooms, children without classrooms, farmers watching fields buried in mud. ‘All I heard was a roar, as though the mountain itself was cracking,’ recalls Elżbieta from Bystrzyca Kłodzka. ‘Then water came through the kitchen window. I felt the whole house drifting away.’

The Fight for Survival

In the first hours, there was no time to think of numbers. Firefighters from mountain towns, soldiers, neighbours, and volunteers formed human chains, carrying children and elderly residents from half-collapsed houses. Local volunteer fire brigades from tiny villages became lifelines, guiding people across torrents on improvised planks.

Marek from Lądek-Zdrój remembers pulling an elderly woman from a crumbling house: ‘She sat on a chair with a rosary, refusing to move. We carried her out by force. An hour later the wall collapsed. She would never have survived.’

At the same time, emergency repairs began on mountain roads — Nadbrzeżna, Zielona, and Hutnicza streets in Stronie Śląskie, where tarmac had simply slid into the river. Breaches in embankments were filled with stones; broken bridges patched with wood.

A Year On — Life in the Shadow of Floods

Almost a year later, scars remain everywhere in the Sudetes. Stronie Śląskie’s centre still resembles a construction site. In Trzebieszowice, nine out of ten households were hit. In Radochów, people describe living ‘as if in a camp’: houses standing but kitchens missing, floors gone, walls damp.

continued at pg. VIII

*) Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:2024_Most_%C5%9Bw._Jana_w_L%C4%85dkuZdroju_(6).jpg (accessed 2025-09-19).

Local inhabitants attribute miraculous powers to the Liri. Its waters are said to cure ringworm—a disease that afflicted children until the early twentieth century—as well as other ailments and deformities. Near Castellafiume, there is a fountain-trough whose water is believed to relieve stomach pain.

On June 24th, the feast of St. John, people still go to the riverbank to perform “lavacri”, ablutions described even in historical sources4. In Castellafiume, in addition to immersing oneself in the icy waters of the Liri as a purification rite, it was customary to drink the water and take some home in glass flasks5. A little farther downstream, in Civitella, a Mass was once celebrated during which children received the sacrament of Baptism at dawn, while adults stood immersed in the river6

Water is a source of life, but also of destruction when it arrives in the form of torrential rain. To ward it off, in Castellafiume a blessed candle from Candlemas Day is placed on the windowsill.

Today, the abundance of Liri water—which once supported subsistence agriculture and a thriving artisanal economy—is almost entirely diverted to the Marsica aqueducts, sadly notorious for the extensive leakages that waste enormous quantities. What will its future be?

4)

5)

6)

Session 7.2.: Comparing agrarian reforms throughout the 20th century: conflicts and oppositions 1 Thursday, 11th September 2025, Faculty of Arts and Humanities Organisers: Sergio Riesco Roche, Carlos Manuel Faísca, Dimitris Angelis-Dimakis

Abstract: How land reforms affected Albanian highlands (communities) Liridona Ura, GO2Albania Sustainable Urban Planning Organization, Albania, Eltjana Shkreli, University of Genoa, Italy

Comprising almost 1/3 of the territory, mountainous areas remained less affected by any state land reform in Albania. The region’s tribal social organization, governed by the medieval laws, regulated land use and limited Ottoman authority to taxation. In the north, where no feudal system existed, collectivization following the 1945 Agrarian Reform primarily impacted properties of regime opponents and religious institutions, while family-owned land remained largely unaffected. Impossible in a dictatorship, opposition to land reform became epidemic through the informal use of any space considered public in post-communism area, leading to socio-economic conflict between individuals, but also between them and the state.

But highland communities rejected the land reform in 1991, standing by the former pre-war property ownership to mitigate disputes, resulting in stronger conflicts with the state. Previous studies on these particular agrarian reforms have tackled a general impact at national level, lacking a case-study based analysis, particularly in the mountainous regions. Using primary field data and archival sources for a comparative analysis and oral history, the paper investigates whether these conflicts originated from the 1945 reform or the 1991 law, ultimately arguing that, despite its challenges, the reforms contributed to a more equitable distribution of land.

continues from pg. VII

‘All winter we kept the stove burning, just to dry the rooms. But the dampness always returns. I feel we are breathing mould,’ says Krystyna, mother of three.

More than 890 mountain residents have yet to return home. They live with relatives, in rented rooms, or in municipal hostels — lives suspended between past and future. Reconstruction in the Mountains

The government announced eight billion złotys in aid for the Sudetes. Bridges are slowly re-emerging; in Trzebieszowice, a new crossing is almost complete. Railways linking Wrocław with Kłodzko and Międzylesie are being restored. EU funds and regional programmes target infrastructure, while money has also been set aside for mountain heritage sites — churches, spa architecture, historic town halls.

Yet mountain residents know that while a bridge can be rebuilt, the rhythm of daily life takes longer to restore. The memory of torrents sweeping through narrow valleys is harder to erase. ‘You can fix a wall. But you can’t silence the fear in a child who wakes at night when the rain starts,’ says Józef, a farmer near Międzylesie. Social Consequences in Mountain Communities

Floods cut deeper than stone. In mountain towns, life revolves around schools, fire stations, cultural centres — the very institutions water destroyed. Without them, communities felt adrift. Children studied in makeshift classrooms, while

adults gathered not for village festivals but to shovel mud.

The health impact is equally stark. Damp homes breed mould, triggering asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia. Families without insurance face impossible choices: rebuild or leave. Winter was a season of illness and anxiety, with coal stoves burning day and night simply to push back moisture.

What the Future Holds for the Sudetes

The Sudetes are rebuilding, slowly but persistently. Hydraulic works are reshaping riverbanks, dams are being reinforced, and retention reservoirs modernised. New flood defences may lessen the danger, yet locals know water in the mountains is always unpredictable. Sudden storms, narrow valleys, and steep slopes make the region especially vulnerable.

‘You can rebuild a house, but you cannot rebuild trust in the mountains,’ says Józef. ‘When the rain drums on the roof, I stay awake. Waiting. Listening. A person is never the same again.’

And yet hope flows too. Every new bridge, every repaired road, every repainted farmhouse is a reminder of resilience. The Sudetes have lived for centuries between the extremes of nature — harsh winters, landslides, floods — and each generation has learned to endure. Water may be stronger than any individual, but not stronger than the solidarity of mountain people.

Magdalena Masewicz-Kierzkowska Maciej Kierzkowski