2 minute read

The Panic of 1893

candidates Milo D. Campbell and Herb Baker because they were farmers and Society members.

Above his type rack at The Je ersonian was a picture of Ruth, the heroine from the Old Testament. She was a familiar fi gure to someone raised in a religious family, and she became a special symbol for Slocum. Ruth represented hard work, steadfast loyalty, and the special virtues of rural living. Her picture reminded Slocum again that those virtues were seldom rewarded on the family farm.

Advertisement

As he worked, occasionally glancing upward, an idea and a plan began to form in his mind. What would happen, he thought, if farmers joined in a great fraternal society to celebrate the ideals of Ruth the Gleaner and at the same time acted together in their own best interest? What if they cooperated at planting time to avoid fl ooding the market with beans one year and wheat the next? Could they market their produce directly to the consumer to avoid the middlemen and the commission agent? Could they save money by buying common items in large bulk? What if they sold at diff erent times of the year to avoid driving down prices? If they learned to cooperate, farmers might even convince government to improve the roads.

As early as 1888, Slocum began to discuss his ideas for a fraternal society with friends and neighbors. The key to it all, he said, “was the need for cooperation.” He talked with anyone who would listen, but soon came to realize not many people were interested. Out of necessity, farmers were self-reliant, and depended only on themselves and their families. It was hard to convince them of the advantages of cooperation in raising or marketing their crops. In their minds, other farmers were competitors, not partners.

Slocum’s plans for a great fraternal society were put away but not forgotten. It wasn’t the last time he found himself promoting an idea ahead of its time. Among his virtues were patience and timing. Events taking place far from Caro fi nally gave him a more receptive audience.

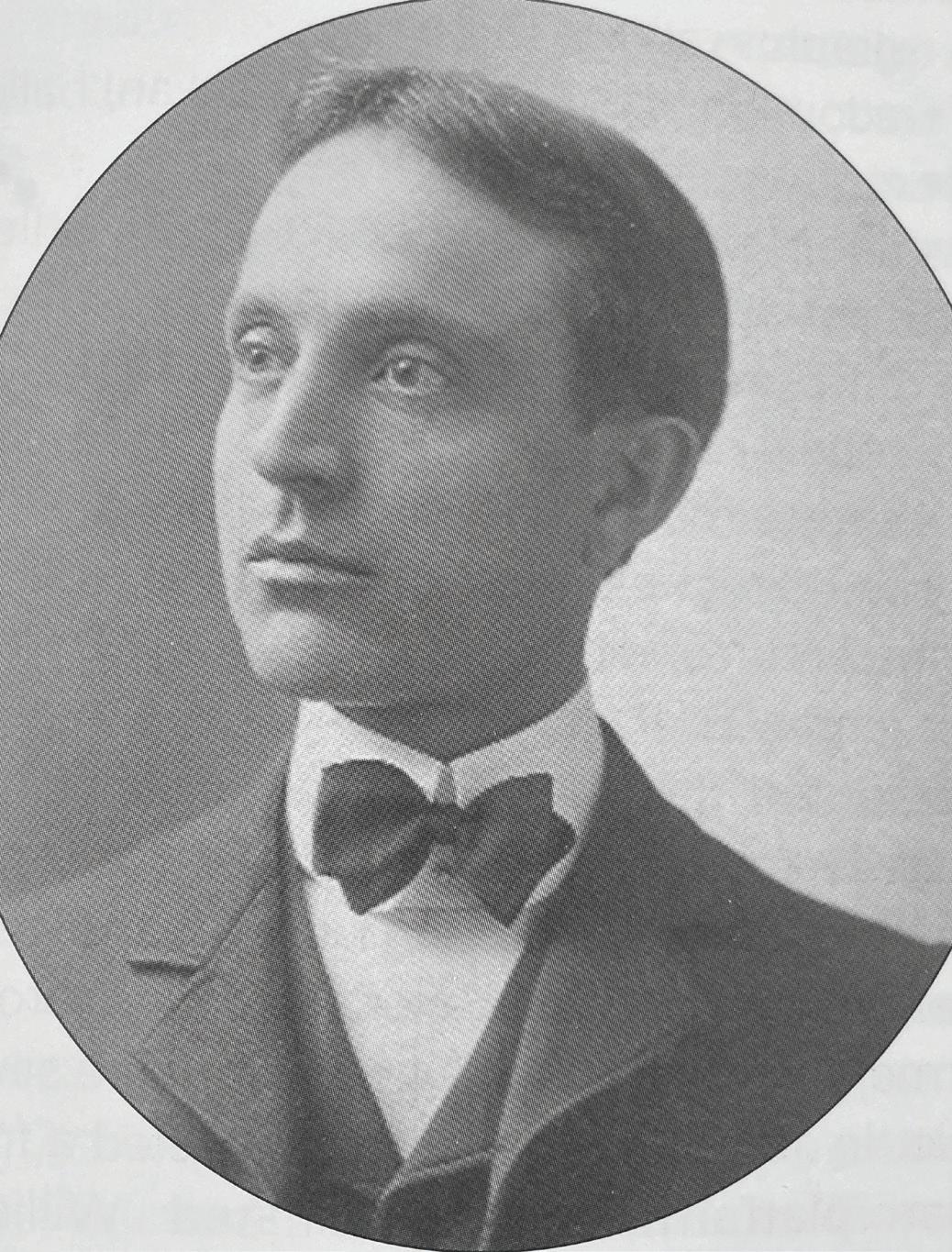

E.H. Streeter The Panic of 1893

The history of the 1880s and 1890s explains a good deal about why the Gleaner movement became a success.

Economic conditions changed rapidly in the country during the late-1880s after the Panic of 1873. “Panic” was the term used in those days for recessions, often marked by panicked selling or bank withdrawals. A reduction in farm prices began as early as 1881 after wheat reached its second-highest price in decades. The country enjoyed an expansion after the Panic of 1873 when the western and northern states fi lled up with settlers. By 1890, the western lands were settled except for the least desirable acreage and the economic stimulation created by western migration came to an end. The government was still on the gold standard and, as a result, the amount of money in circulation did not keep up with increasing population and booming business. A shortage of money, and other factors, led to a general depression.

An estimated 8,000 businesses failed in the fi rst months of 1893. Four hundred banks failed, most of them in the western and southern states. In the absence of federal deposit insurance, the bank failures had a further depressing eff ect on the economy. Cash to pay bills and transact business became very scarce. Forty-six railroads