5 minute read

Rural Free Delivery, Parcel Post and Better Roads

them. The result was the Gleaner Amusement Company, started in 1906. Its fi rst director, Frank E. “Gene” Manley, often assisted Slocum at arbor organizing meetings. Members of the Company were employed by the Society and sent to arbor meetings, usually in a horse and buggy. “Professor” Harry Burton and his assistant, “Professor” Casselman, visited hundreds of arbors. An article in The Gleaner described an early program, probably typical of those that followed:

“The entertainment will consist of features of magic, ventriloquism, exhibitions of spiritualistic mystery, the wonderful Edison kinetoscope showing moving pictures of exceeding beauty and interest including views, illustrated songs, the latest Parisian sensation poses, plastic, mysterious, fascinating and pleasing to the eye, and numerous other high class numbers...”

Advertisement

Not all the programs featured “the latest Parisian sensation poses.” Some were instructive as well as entertaining. Many were thought-provoking and helped bring the farmer into the mainstream of American life. They also served to bind the Society together through shared experiences.

The Amusement Company was a success, but it passed from the scene in the 1920s. Moving pictures, the radio

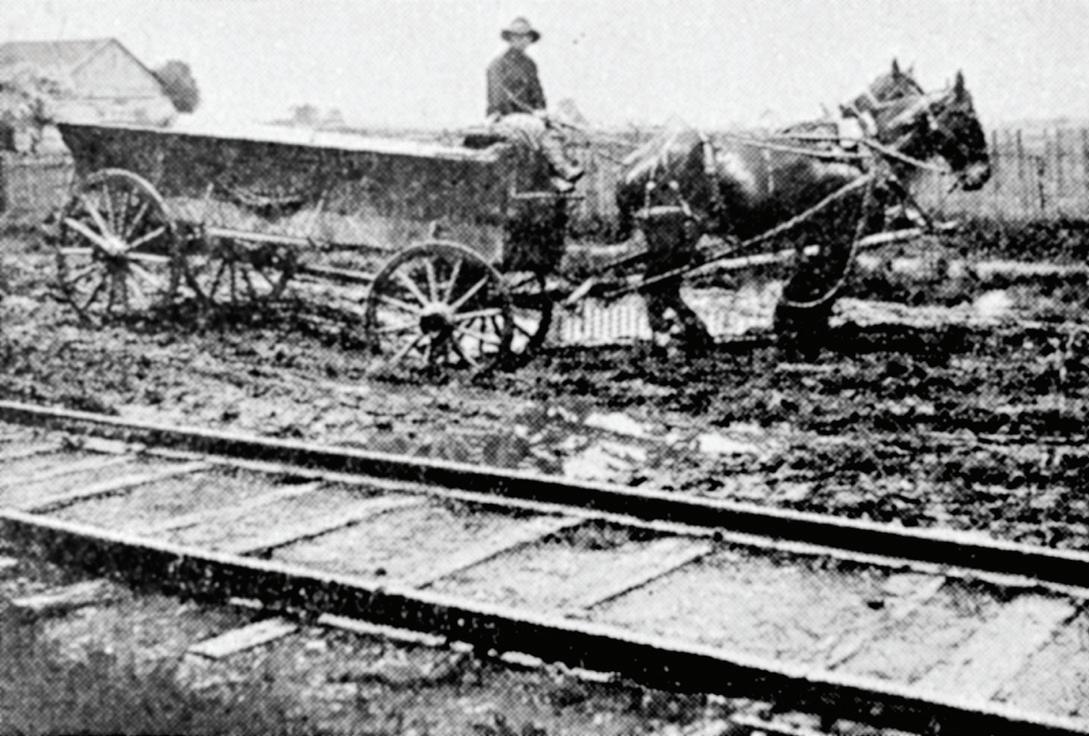

The Gleaner newspaper printed this 1912 cartoon showing wealthy express companies blocking the public’s path to have Congress create Parcel Post. Dirt roads that turned into muddy swamps were common when The Gleaner printed this in 1913. The Society pushed for state and federal funding to build paved roads.

and the automobile all replaced the traveling road show as a form of entertainment.

The Gleaner Society had a lot of political infl uence in the early part of the century. Because of their numbers, farmers were a large political block and as the Society grew it began to speak for more and more of them.

Nothing irritated the farmer more than the need to go to town to pick up his mail. House to house mail service was common in the cities, but not in the country. Why, he grumbled, should a person living two blocks from the post offi ce have his mail delivered while a farmer had to travel miles over bad roads for his? Didn’t stamps cost the same for everyone?

The campaign for rural free delivery was successful only after years of politics, pressure and hard work. The Gleaner organization was prominent in the eff ort, and in fact was the leader in Michigan.

The practice of purchasing goods by mail order is enjoying a revival in the United States today. Not many people know that buying through the Sears Roebuck or Montgomery Ward catalogues was a thriving business even before World War I. The rise of Sears and Montgomery Ward was made possible by the parcel post laws fi nally approved in 1912 and put in use in 1913.

In 1908, the Gleaner members began to campaign throughout the Midwest in support of parcel post. The United States mail confi ned itself to letters and parcels under four pounds in weight, a limitation making it impossible to purchase many items through the mail. The alternative was to use expensive commercial freight service such as Wells Fargo.

Nearly all farm organizations were involved in the campaign. They were opposed by merchants, wholesale salesmen, freight companies and even bankers. Local merchants were afraid of the competition from mail order houses and the salesmen had an obvious interest. The freight companies stood to lose a lot of very profi table business if the U.S. Mail delivered larger packages. The interest of those in the banking business was not as obvious, but they must have been supporting other businessmen on principle.

A congressional commission was formed to study the parcel post question. It met during the summer of 1911 and recommended a law be introduced. The suggested rates were so high, and the delivery range so limited, that most groups including the Gleaner membership opposed the bill. The Society, through its newspaper, claimed the rates were determined by the freight companies in an eff ort to make the law ineff ective.

The battle was still not quite over when the Senate voted the parcel bill out in August of 1912 with the higher rates. Because only 21 of the 96 senators were on hand, farm lobbyists succeeded in having the vote reconsidered. The fi nal version of the law represented a victory for the Gleaner Society and other farm organizations. The new parcel post system began on Jan. 1, 1913. Finally, after fi ve years of eff ort, a farmer could mail a package up to 50 miles away for as little as three cents per pound. He could now shop by mail from a catalogue company such as Sears or Montgomery Ward and receive the goods at a reduced rate.

The Gleaner organization invested a lot of time and money in the parcel post fi ght. Petitions were signed and letter writing campaigns were encouraged. A picture in the June 1912 issue of The Monthly Gleaner shows Slocum and his assistant editor with more than 3,000 letters being forwarded to Michigan’s congressional delegation. Delivery options and rates for U.S. parcel post have evolved over more than a century since, but the availability of a public delivery service exists today thanks to the Society and other groups who demanded its approval in 1912. The contribution of Gleaner members was a large one.

In addition to rural free delivery and parcel post, the Society advocated for better roads. It is diffi cult to imagine how poor roads were in the early 1900s. Rural roads were more like swamps in the spring and fall and only barely passable in the summer and during a freeze in the winter. Farmers often had trouble getting crops to market after the fall harvest.

Part of the problem with the roads was that they were usually constructed and maintained by adjacent property owners. Except for a few national or state highways, local governing bodies had the entire responsibility for rural roads. In Michigan, a local person was elected “pathmaster” for a section of the

A wagon bogged in a muddy road along railroad tracks was among photos printed in June 1909’s Forum to launch a campaign for better roads.