13 minute read

Five — The Roaring Twenties

60

Chapter Five The Roaring Twenties

Advertisement

The last Gleaner convention at which Grant Slocum, the Society’s founder, presided took place Dec. 5-7, 1923, at the Hotel Statler in Detroit.

The decade of the 1920s was a time of great change in American life and in the Gleaner organization. The Clearing House Association, that great experiment in farmer cooperation, came to an end in the recession of 1920. The Society safely passed through the fi nancial demands caused by the First World War and the infl uenza epidemic. The title of the Society’s chief executive offi cer was changed from secretary to president in 1920, and in 1924 the Society’s founder and president, Grant Slocum, died. Assets continued to grow but when the decade ended so did prosperity. The Great Depression of the 1930s began with the stock market crash in October 1929.

Secretary Ross L. Holloway was chosen to succeed Grant Slocum. Holloway was born on Jan. 19, 1866, on a farm near Norwalk, Ohio, but moved with his parents to Portland, Michigan, as a child. He graduated from Michigan State Normal College in Ypsilanti in 1892 and served as superintendent of schools in Caro until 1900. From 1900 to 1908 he was the editor of the Tuscola County Courier, Slocum’s newspaper. In 1908 he was appointed assistant secretary of the Ancient Order of Gleaners and moved with the organization to Detroit. He became secretary in 1920 and was named president by the Supreme Council on Aug. 22, 1924.

The term “social revolution” has been used to describe the 1920s. It was the age of Prohibition, jazz, the fl apper, the automobile, the radio, the airplane, and the moving picture. It was also the era of declining church membership, declining fraternal societies, and rapid population growth.

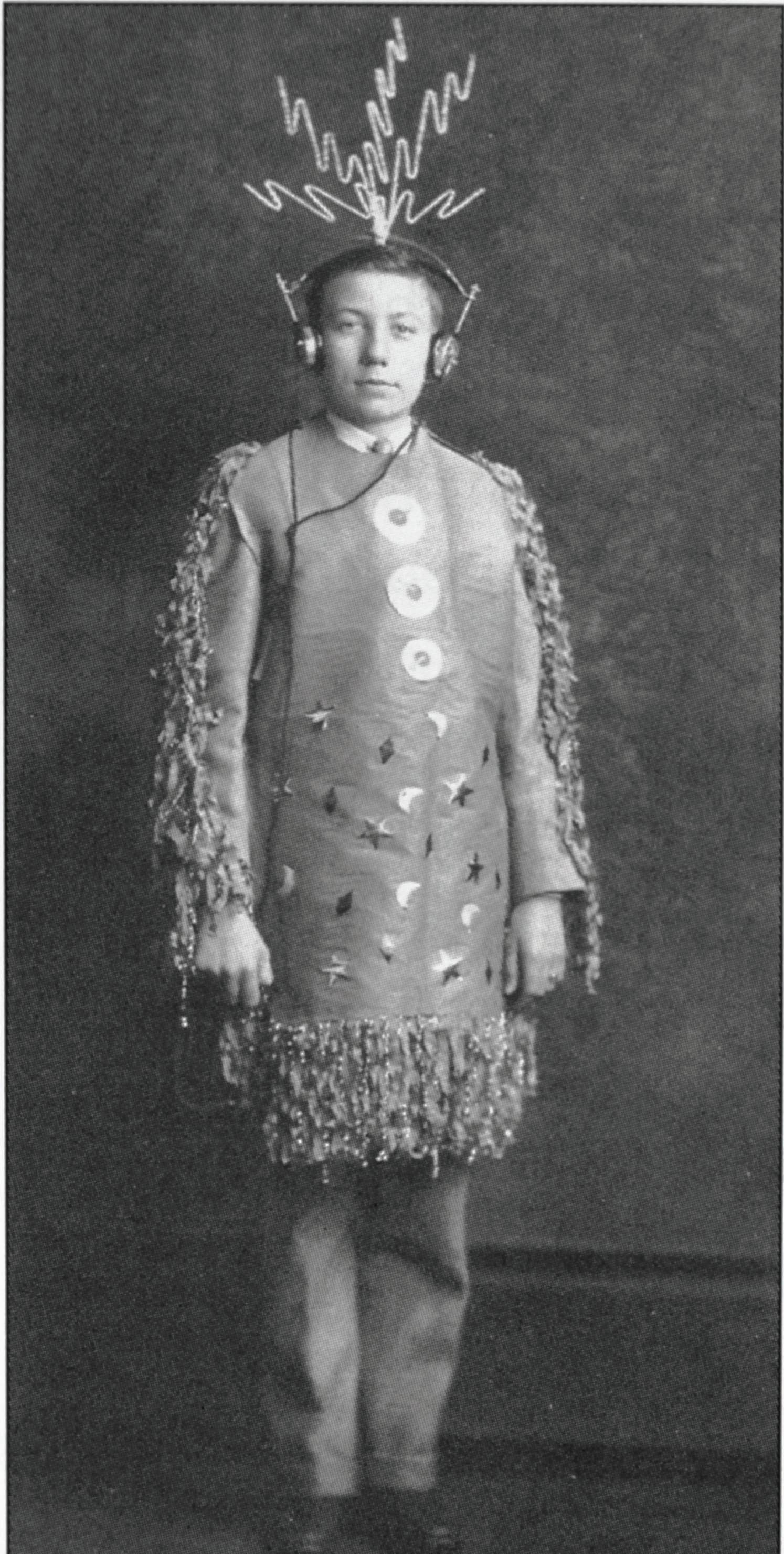

Gleaner members celebrated the growth of commercial radio with a youth announcer at their 1927 Biennial Convention in Kankakee, Illinois. Dorothy Tanner of Kankakee Arbor, Illinois, welcomes delegates to the 1925 Biennial Convention in South Bend, Indiana.

Prosperity followed the 1920 recession, allowing farmers to buy automobiles and other labor-saving devices. Rural isolation became a thing of the past. The Gleaner Forum editorialized:

“Time and distance have been largely eliminated as obstacles to our activities. They (radio and the automobile) have modi ed our viewpoints and our style of living. The moving picture has largely succeeded other forms of public entertainment.”

The changes in society had a profound eff ect on Gleaner arbors. Rural people became less dependent on arbors for social activities and support in time of crisis. Attendance fell at arbor meetings as it did for other similar institutions. The Forum reported:

“All these changes have combined to create a serious condition for the small lodges of all fraternal organizations and for that matter some of the larger lodges. Interest has steadily been declining. Attendance, especially in isolated rural points, has fallen o .”

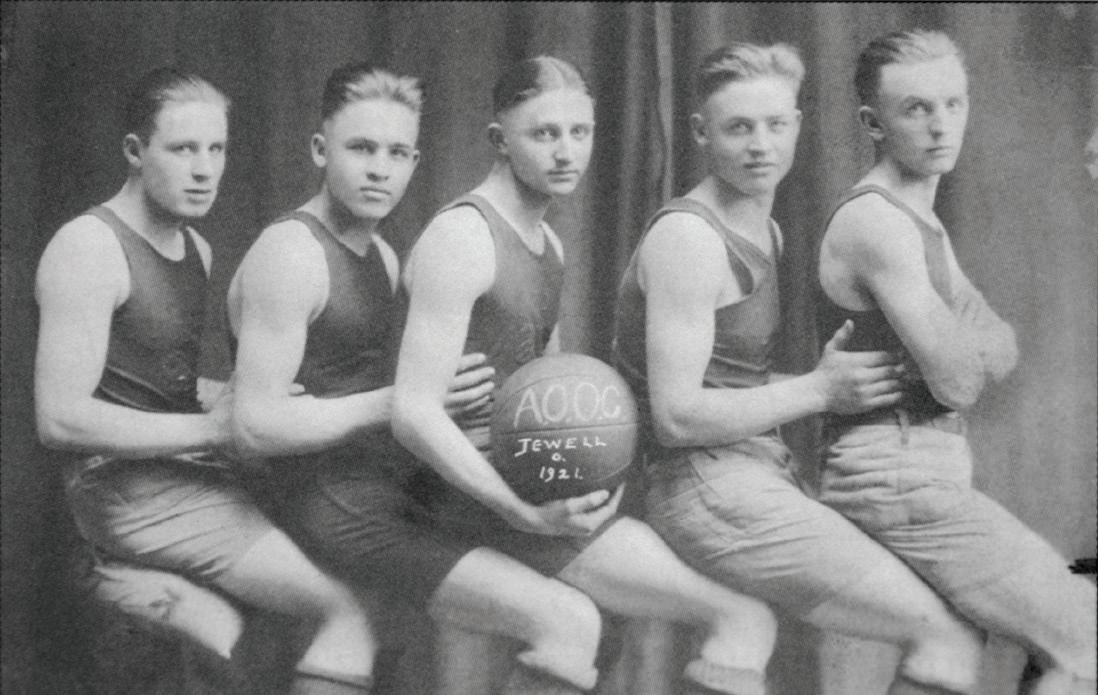

Jewell Arbor, Ohio, Basketball Team, 1921. Left to right: Emmit Dunbar, Lee Hammer, Laverne Patton, Kenneth Hammer, Charles Mohr.

Special lifeguard Rae Shannon demonstrates the Schae er Method of Resuscitation for Junior Gleaner summer campers in 1929 at Camp Gray, Michigan. Girls learned exercises at 1929’s Junior Gleaner summer camp. They were pictured at Camp Gray near Saugatuck, Michigan.

Total Gleaner membership began a steady decline. Membership reached a peak in 1912 when 75,215 were enrolled. By 1920 the number had fallen to 63,427 and by 1930 to 49,949 including 4,100 in the juvenile department.

The ratio of assets to liabilities continued to be a problem for the Society throughout the decade. From 1895 to 1906 only four to six assessments per year were called for while insurance in force expanded rapidly. From 1907 to 1913 assessments averaged only seven per year. After Class B was established to slow the widening gap between assets and liabilities, 10 and then 12 assessments were called for in Class A (the original insurance program). When Class B was fi nally adopted, rates recommended by the National Fraternal Congress were adopted for new members, making that part of the business actuarially sound. An actuarial department, established under Professor James Glover at the University of Michigan, helped guide the Society.

At the 1921 biennial convention held in Toledo, a committee recommended new rates as proposed by the National Fraternal Congress. Michigan law required a referendum be held on the question. The membership approved the higher rates in August 1922. The increase was necessary, but the adoption probably contributed to the decline in membership that followed. At the time assets were approximately $2 million and insurance in force more than $50 million. By 1926 nearly 38,000 members holding the old Class A certificates had converted to what became known as the American Experience class at much higher rates.

At the 1923 biennial convention held in Detroit, a “Great Leap Forward” movement was announced, to start in 1924. The new Standard Certifi cate was described as, “Absolute and complete protection under plans which have the approval of the most competent actuaries and which are fully sanctioned by state and national laws.”

Members who still held the original certifi cates were urged to convert to the Standard Certifi cate and to use their assets in the Emergency Fund to pay future premiums.

After two decades of eff ort the rate question was fi nally solved, but at a cost. A new kind of Society emerged, smaller but fi nancially sound. It was better suited to make its way in a changing world.

Another signifi cant change took place at the 1923 meeting. The Law Committee recommended, and the delegates approved, a resolution to abandon the

The Society’s Junior Gleaner program was o cially started in 1926, although many arbors had Junior Gleaner clubs prior to that. This Illinois Junior Gleaner group was shown in pageant costumes.

Bohemian Folk Dancers, Sulphur Springs Arbor, Illinois, 1927.

requirement that only farmers and those connected with agriculture could be benefi t members. The action was probably inevitable. The number of those engaged in agriculture decreased as farms became more mechanized and their size increased. More young people raised on the farm migrated to the cities out of necessity, and simple arithmetic explains why. A couple with four children will, if their children marry and each have four children, soon fi nd the family farm of 80 to 120 acres trying to support 50 people. Since the days of plentiful public lands and the Homestead Act were long over, young people left the farm for new careers elsewhere. Gleaner members recognized the change and set out to recruit new members in the cities and small towns.

Exceptions to the membership rules had been made over the years. Slocum, the founder, was a printer and newspaper publisher. Chase was a physician, and treasurer Ealy a banker. Slocum later claimed to be a farmer when he purchased a small farm near Lake St. Clair.

Even after the changes adopted in 1923, membership was still restricted. Applicants had to be “of good moral character, sound mentally, in good health, not addicted to liquor or narcotics, reside in a territory in which normal death rates have been experienced, and be between 16 and 60 years of age.” In addition, the Supreme Council was required to approve any new territory open to membership.

Starting in 1928 it became necessary to eliminate some arbors and consolidate others. Many of the arbors organized between 1894 and 1910 disappeared. The Gleaner Forum explained:

“The Gleaner organization in this, as in other matters of progress, is now among the rst to appreciate this call for adaptation and to make a rational, practical solution of it. We are forming centralized Gleaner units not with the idea that the local lodge is of less importance, but that is of more importance than ever, that it must be fostered as never before; that its light must shine stronger than in the past years, shedding its rays over larger communities. A few more miles of travel these days means nothing.”

Arbors were consolidated only with the approval of the local membership and the Supreme Council, but there was little choice in most cases. County Associations, common in Ohio for several years, were encouraged. Twenty-fi ve Michigan counties formed associations in 1928 and 1929. Five were formed in Illinois in 1929. The consolidation eff ort resulted in larger arbors, greater fi nancial support, and injected greater effi ciency into the Society’s insurance business.

Despite the loss of membership the Society prospered during the 1920s. Assets increased from $1,342,104 in 1920 to $5,295,437 at the end of the decade. The net worth of the Society doubled in the four-year period ending in 1929. The gain came from a greater return on investments and higher insurance premiums. Insurance in force expanded to more than $41 million, all of it on a legal reserve basis. The Society invested heavily in farm mortgages returning 6.5% interest and bonds paying

Women of Gleaner

Ada “Peggy” Maxwell

When Gleaner co-workers needed answers, Ada C. “Peggy” Maxwell was often the person they asked for more than 44 years — even though she couldn’t hear them.

The 1970 winter edition of Forum, just over 50 years ago, covered Peggy’s retirement after 44 ½ years of service in the Society’s Home Offi ce. “Farewell to Peggy” noted that Peggy was “handicapped by isolating deafness,” so she pursued lip reading and “was recognized as Michigan’s champion lip reader.”

Peggy graduated from Port Huron High School in 1920. After her fi rst job with the Ladies of the Maccabees, and then a break to care for her grandmother around 1926, she spent her entire career onward working with Gleaner statistics. She became a member in 1937 and was an actuary for the Society when the plastics industry was in its infancy. Because no one had satisfactory answers about its various occupational risks, Peggy spent her vacation visiting diff erent plastics facilities and studying the issue.

Peggy became the second person in Society history to be listed as an underwriter in 1948. In 1958, she was put in charge of Policy Service, giving her an extensive background.

Peggy died in 1984 at age 81 in Livonia and was buried in Port Huron, where four of her nieces and nephews lived. Monitor Arbor, Indiana, Patriotic Drill Team was pictured outside the arbor’s hall Nov. 19, 1926.

Liberty Center Arbor, Ohio, men’s precision drill team.

6%. Nearly 200 of the farm mortgages were investigated by Society offi cers because of the infl ated values brought on by World War I. Some were foreclosed and others were negotiated.

During the ’20s the Society began to invest in city real estate, and state, municipal, and school district bonds. Despite a drop in land values, $6 was invested in farm mortgages for every $1 in city property. The percent of solvency ranged from 113% to 118.9% with an average of 115%. Investments seemed to be conservative and well-secured.

A Juvenile Department, fi rst proposed by Slocum in 1914, was fi nally established in 1926. The eff ort was

West Lockport Arbor, Illinois, Gleaner hall, constructed in 1923.

an immediate success with more than 4,000 members at the end of the decade. In addition to insurance, the department off ered “such activities and useful training as will appeal directly to these young minds and hearts, tying them to our Society by cords of personal interest.” The Juvenile Department had its own rituals and local Arbor activities.

It was also during the ’20s that updating the name of the Society began to be considered. Although the records do not include the debate that must have occurred, the reason for the change seems obvious. “The Ancient Order of Gleaners” must have seemed an old-fashioned name not in tune with a more sophisticated world. Delegates at the 1931 biennial convention in Toledo approved the new name Gleaner Life Insurance Society.

The change was refl ected in a statement made by the new president:

“The function of a fraternal society are dual in nature and purpose. First there must be nancial soundness. This condition can be kept secure only through proper plans of protection, adequate premium schedules and e cient eld organization. Then there must be continually developed and carried forward such social and benevolent activities as are consistent and practical.”

The emphasis was on “fi nancial soundness” and not on the great, and sometimes impractical dreams, of the early Gleaner movement. Out of necessity the Society turned away from populist reforms and toward saving what had been achieved. The insurance reforms of the 1920s were necessary and may be said to have saved the Society from extinction. President Holloway was sensitive to what was happening when he wrote:

“The establishment of the Society upon a thoroughly sound and modern business basis might sometime be suggestive of a departure from the old fraternal spirit and practice. Far from it! Rather these transformations have been to render the work more e cient ...”

At the same time, it is easy to recognize the passion and dedication of Grant Slocum as he railed against the “commission men” and all those who tried to take advantage of the farmer. One must admire the zeal with which the early Gleaner members supported female suff rage and fought for Prohibition. Older members must have been nostalgic about the days when the local arbor formed its own elevator, petitioned the Legislature for better roads, and opposed the war fever sweeping the country in 1915. Who but the Gleaner Society would have thought to campaign for rural restrooms or take a stand against vivisection (still being debated today), or threaten early automobile owners with mayhem only to become advocates of the internal combustion engine? The one great failure, the Clearing House Association, might have succeeded except for the depression of 1920, but even in failure it was a magnifi cent eff ort.

In the early days it was accepted that the order would

The Ottokee Arbor, Ohio, Junior Gleaner Council No. 9 was pictured in the late 1920s.

Ottokee Arbor, Ohio, members dressed in costumes for a mock wedding party at a July 4, 1928, Fulton County parade.

“The Spirit of ’76” at the 1925 Biennial Convention in South Bend, Indiana, featured from left John Rathman, Wilber Rathman and Warren Asher.

National o cers in 1926 were (back row, from left) Herbert Baker and Dr. Malcom M. Wickware; (middle row) Joseph J. England, Henry I. Zimmer and Mrs. Elfa Munn; (front row) George I. Strachan, John R. Hudson, Treasurer; Ross L. Holloway, President; Raymond Reitter, Secretary; and Frank C. Goodyear.

soon cover all 46 (later 48) states and eff orts were made to expand in all directions. Everything seemed possible, and ambition for the Society knew no bounds. But, as always happens in history, the survivors are numbered among those who adapt to change.

Gleaner Life Insurance Society learned to adapt in ways not dreamed of by The Ancient Order of Gleaners. By 1932, the Society was signifi cantly transformed. Despite the changes, dedication to Benevolence, Protection and Fraternity still existed and the motto “Thoughtful for the Future” was still on the masthead.

Ross L. Holloway

President, August 22, 1924 - November 5, 1936

68