20 minute read

Two — The Early Years

Chapter Two The Early Years

A Hoxeyville, Michigan, band in Gleaner uniform stands ready for a rally in Manton, Michigan.

Advertisement

The articles of incorporation for The Ancient Order of Gleaners were drafted by Caro attorney Walter J. Gamble on Sept. 2, 1894, and sent to the Commissioner of Insurance for approval.

The application was signed by Slocum, England, Eayrs, Chase, Gamble, Ealy, L.W. Ostrander, C.D. Petershans, and D.A. Graham.

By the time state approval was sought 220 persons had been enrolled and their health certifi ed by Dr. Chase. The applications were held until the charter was received on Sept. 25. The fi rst certifi cates were issued Oct. 19. Offi ces were rented in what was known as “The Herman Block” on North State Street in Caro. The headquarters remained at that location until Aug. 1, 1898. The Herman Block still stands in Caro, housing retail shops in 2021.

As a newspaper publisher, Slocum understood the need to communicate with the members of the new order. In the fall of 1894, he published a four-page paper called The Gleaner, which eventually became a large and infl uential farm journal.

The Ancient Order of Gleaners was the fi rst fraternal society to be organized under Act 119 of the 1893 Michigan Legislature. The law was designed to bring order to the chaotic fraternal insurance business in the state. Act 119 was not a stringent law but it was the beginning of a series of state regulations that eventually placed all companies on a sound fi nancial footing. Act 119 did require yearly reports to the insurance commissioner and a review of rates.

Life insurance companies were slow to develop in the United States. The oldest is the Presbyterian Ministers Fund chartered in Pennsylvania in 1759, but the fi eld didn’t expand until the 1840s and 1850s when 18 new companies entered the trade. Business boomed during the Civil War but languished afterward as a series of

depressions racked the country. Few people of modest means could aff ord insurance and the old-line companies did not pursue mass marketing. That left the fi eld wide open for fraternal societies. People like Slocum saw that the need was there, and soon millions of people had insurance policies, or “certifi cates” as they were called.

Gleaner insurance was a newcomer in a crowded fi eld. L.W. Ostrander, one of the fi rst organizers, told the story of a man being hung in Shiawassee County for trying to start another insurance society. Although the story was told “tongue in cheek,” his remarks illustrate the problems faced by the early Gleaner members.

Slocum was critical of the older insurance societies and determined to set the Ancient Order of Gleaners on a diff erent and better course:

• The yearly assessment for expenses would be the same as that charged by the others ($1.00) but 50 cents would be set aside in an Emergency Fund.

• Only farmers or others in agriculture would be eligible for membership.

• Certifi cates would also provide disability benefi ts.

• The aff airs of the Society would be governed by a representative assembly and elected offi cers.

• Men and women would be admitted on an equal basis and both would be involved in the rituals.

• New members would be solicited by Gleaner members to avoid the employment of outside agents.

The creation of an Emergency Fund was a wise decision but, at the time, a controversial one. In a mutual insurance society, rates were presumably increased or decreased as needed to pay the benefi ts. Critics of the Emergency Fund said that members should be entitled to “keep the Emergency Fund money in their pockets until needed.” Slocum was not satisfi ed with that argument for two reasons. He saw that assessments might increase to the point people would leave the Society rather than pay them. He also thought the Emergency Fund might someday save the Society at a time of fi nancial stress.

The Gleaner Society came under criticism from other fraternal orders because of the Emergency Fund, particularly from the Maccabees. Both sides used the issue when recruiting new members. Slocum was eventually vindicated when state governments required all fraternal societies to create a fund similar to the Gleaner Emergency Fund.

The decision to restrict membership to farmers was not only based on fraternal considerations but for hardheaded business reasons. Slocum studied the vital statistics published by the state of Michigan in 1892 and discovered something the old-line companies may have missed. The death and accident rate for farmers was signifi cantly lower than that for city dwellers. The death rate was 13.1 per thousand residents for the cities and only 8.1 for rural areas. By only enrolling farmers in the Society, and by screening applicants carefully, Slocum hoped to make the Society fi nancially sound. Dr. Chase reviewed all applications for health problems and personally examined many applicants.

Gleaner members showed fraternal charity, especially toward widows and orphans such as the Leitch family of Cass City, Michigan. The father had forfeited his membership when he took an especially risky job in 1901 as an engineer at a tile plant. A few days later he was killed in a boiler explosion. Although the Society was not legally obligated, members raised enough money to pay o the mortgage on the family’s farm home and to protect the three children.

Disability coverage provided by the AOOG certifi cate was a popular feature which brought many into the Society. A $250 certifi cate holder could receive $5 per month, increasing to $10 for a $500 certifi cate and $20 for anyone insured for $1,000. The benefi t was either repaid or deducted from the face amount of the policy. Those totally disabled could receive half the face amount of the policy. One-fi fth of the face amount was paid for the loss of a hand or foot, and half the face value for loss of both hands or feet. Although the amounts do not seem large today, they off ered a degree of family security.

Even during those fi rst hectic months Slocum preached that the value of the AOOG was to be found in its fraternal ideals. One of the fi rst articles in The Gleaner newspaper contained this:

“Men have won fame by brave deeds performed on bloody battle elds, by the subjugation of opposing forces and peoples; but far nobler in the sight of a just God are those forces and associates which build up rather than destroy, which inculcate friendship, love and truth, rather than enmity, hate and wrong.”

Slocum also saw life insurance in a fraternal as well as a business context. He quoted this comment by Pennsylvania Insurance Commissioner George B. Luper:

“While I regard life insurance purely as a business and not as a charity, yet in every thread of its warp and woof I can see the golden tints of the sweetest and rarest charity in the world. It is one of the ladders reaching from heaven to earth, down which comes the answers to the prayers of the widows and orphans as they humbly lisp, ‘Give us this day our daily bread.’”

During that fi rst year the offi cers concentrated on organizing Tuscola County. In January 1895, The Gleaner reported that every township had at least one arbor, with a total of 43 arbors in 23 townships. Ellington Arbor, located just east of Caro, was the largest with 40 members while none had fewer than 10. The Ancient Order of Gleaners was obviously meeting a deeply felt need in the community. The fi rst convention of the AOOG was held in the Odd Fellows Hall in Caro on Dec. 31, 1894. Less than three months had passed since the fi rst certifi cate was issued. To the surprise of many, 70 delegates representing 60 arbors and 670 members were present. The treasury held only $167.50 after paying the fi rst death claim to the family of Ada Hutchinson, a member of Ellington Arbor. Only $250 certifi cates were sold in the fi rst three months of operation but by December there were enough members to increase the maximum amount to $500.

In his report to the delegates Slocum explained how the Society was able to begin operation without a treasury. He credited John Ealy with arranging the necessary bonds to qualify for the charter. What he didn’t say was that he, Ealy, Chase and England had each contributed $250 to cover organizing costs. The money was never repaid, and the debt was eventually canceled at their request. He also expressed appreciation to the banking firm of Carson, Ealy and McNair for agreeing to pay 4% interest on the Emergency Fund, a higher rate than normal.

Michigan law did not permit women to buy insurance with their husbands as benefi ciary. The reason isn’t clear but evidently the death of a wife was not viewed as seriously as the death of a husband. The delegates supported a change in the law and in May 1895 were able to announce that House Bill 48 had removed the inequity. The Gleaner organization supported many other women’s issues over the following decades.

The care with which the Society conducted its affairs is illustrated by the way emergency benefits were approved. Slocum suggested that until total disability could be certified, a three-month limit be placed on payments. Thirty days after the last payment, a review was made by Dr. Chase, and a final decision made. This limited the Society’s liability while maintaining the integrity of the disability guarantee. Slocum warned the delegates, “All through the charter there are little holes which should be covered before the Order gets stronger and becomes operative.”

Charter offi cers elected were: Chief Gleaner: Joseph J. England Vice Chief Gleaner: Benjamin F. Eayrs Secretary: Grant H. Slocum

Treasurer: John M. Ealy Medical Examiner: Dr. Sherman F. Chase Inner Guard: J.P. Jeff rey Outer Guard: L.W. Ostrander Two additional offi ces were created: Chaplain: Rev. Christopher England Conductor: George D. Moore

In the next four years after the fi rst convention a strong eff ort was made to recruit in southeastern Michigan. By 1899 there were 301 arbors, all of them still within 75 miles of Caro.

An issue that lay like a cloud over the fi rst convention was the question of insurance rates. The initial rates were the same as those charged by other fraternals, but none of them had been adequately researched. Rather than having regular premiums at predetermined times, fraternal societies of the time levied assessments on each certifi cate whenever death claims reduced funding below certain levels. Members who failed to pay their assessment were suspended. As it grew, the Gleaner Society proudly levied only fi ve assessments in 1896. However, as growth slowed and members aged, the number of assessments grew. By 1914, certifi cate owners faced 12 assessments per year. The Society was accepting an ever-growing liability as the membership grew but not fast enough to guarantee fi nancial stability.

The second yearly convention of the State Arbor was held in the Caro Music Hall on Dec. 19, 1895. After 14 months there were 1,808 members and $1,718.59 in the treasury. Net assets were $1,010. Some of the “little holes” predicted by Slocum the year before had to be fi lled.

A change was made in how the Society was governed. An Executive Council composed of Chase, England and Eayrs was in charge of both business and fraternal activities, but these activities sometimes came into confl ict. Applications for disability benefi ts were more numerous than expected and some were denied because “all kind of fraud” was being used to secure benefi ts. The Executive Council soon came to realize that those working with fraternal activities should not also be making unpopular business decisions. The 53 delegates approved the creation of the Supreme Council to supervise all insurance and other business aff airs while the Executive Council continued to supervise fraternal activities. In order to separate the Council from member complaints it was agreed the members could not hold any other offi ce in the Order. Chase, England and Eayrs were elected to the fi rst Supreme Council. Ara Collins of Marlette was elected Chief Gleaner to replace England and W.H. Fritch of Imlay City replaced Eayrs as Vice Chief Gleaner. This action made the Society stronger and more fi scally responsible.

Other offi cers elected in 1895 were: George D. Moore of Medina, Conductor; James Fee of New Lothrop, Chaplain; and S.S. Wood of Ellington, Outer Guard.

Delegates also approved the sale of $500 and $1,000 certifi cates and the elimination of those for $250. The change was made to bring Gleaner policies in line with other fraternals. Rates for the new certifi cates were increased at the request of the Commissioner of Insurance, proof the 1893 law was working. Offi cers stated, “If the assessment rate is a little higher it will be paid less often.” The thin line on which the insurance program operated is revealed in the statement made at the meeting:

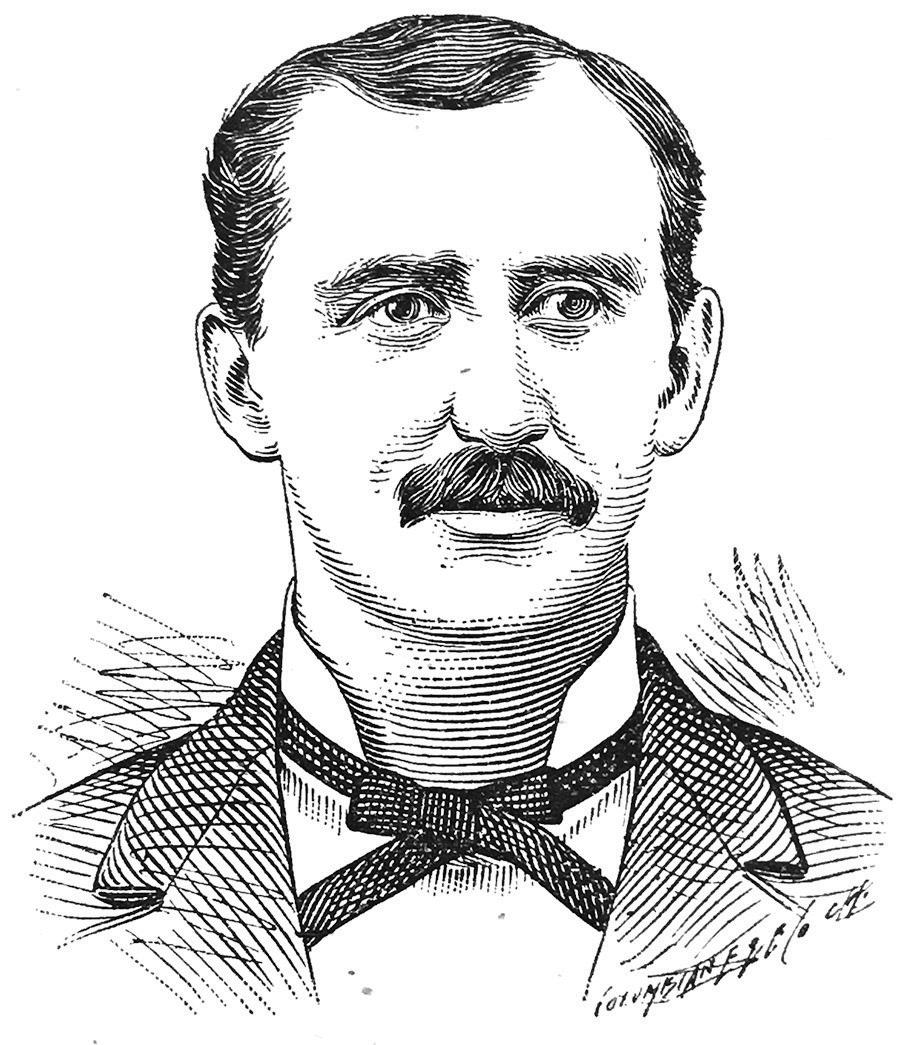

George D. Moore of Medina, Michigan, was among the rst Gleaner o cers. He served as Conductor and, later, was serving as Chaplain when he became one of the rst o cers to die in 1900.

“The epidemic of fever which fell so heavily on the other societies passed by the Ancient Order

1915 Supreme Council. Back row, left to right: Ross L. Holloway, Frank C. Goodyear, Joseph J. England, Grant H. Slocum, and John Livingston. Front row, left to right: Henry I. Zimmer, Mrs. Elfa Munn, and George I. Strachan.

of Gleaners, and showed our proud ship out of reach of epidemics.”

The year 1898 was a watershed for the Gleaners. Assets grew rapidly after that date, and the membership began to expand into other states, Ohio fi rst and Indiana soon after:

Year Arbors Members

1894 (Dec.) ............................... 60 670 1895 (Dec.) ............................... 85 1,808 1896 (Dec.) .............................147 3,101 1898 (June) ............................301 8,601 1899 (Jan.) ..............................380 11,115

Assets grew in proportion to the number of members:

1894 ........................................................................................ $167.50 1895 ....................................................................................... 1,010.00 1896 ....................................................................................... 2,529.00 1897 .....................................................................................12,594.77 1898 .................................................................................. $21,775.61 During the next few years offi cers were forbidden to invest Emergency Fund money for fear a loss would occur.

By 1900 the constitution was changed in order to get a larger return on investments than banks would pay. United States bonds were fi rst purchased in 1899 and school district bonds in 1905. Eventually a large share of the money was invested in farm mortgages. Always cautious where Gleaner funds were involved, offi cers would only loan 50% of the assessed value of real estate.

By 1900 assets were still less than $50,000 while insurance in force exceeded $16 million. Despite the 1895 increase, premiums were still small compared to the rates charged by old-line companies. Fraternal insurance societies were caught in a dilemma. They existed because they charged low rates to people who could not aff ord to pay more. Higher rates would mean a loss in membership.

In a sense, fraternal insurance societies were operating what became known as “pyramid schemes.” The payment of future benefi ts depended on the enrollment of more and more new members to carry the cost. Since the certifi cates could be assessed, it was assumed by many that future defi cits would be covered by additional charges to individual members. Competing fraternals,

Gleaner picnics were popular from the Society’s beginning. This 1910 picnic at Deibert Station south of Kalkaska, Michigan, featured both a colt show and a baseball game.

however, determined their rates by keeping an eye on what each other charged and making sure their rates were competitive.

The failure rate of fraternal insurance societies was fairly high. Slocum, and a few others, understood the reasons very well. He wondered aloud and in print about what would happen when membership peaked, as it inevitably would. In an article published in The Monthly Gleaner, he stated that by 1926 the Maccabees would have to recruit one and a half million new members each year in order to stay solvent! By 1901, 12 Michigan fraternals had gone out of business, but still the total number increased from 39 to 71. The National Fraternal Congress was created to bring some stability to the movement. The Fraternal Congress, which published the magazine The Fraternal Monitor, merged in 1912 with the Associated Fraternities of America and in 2011 became the American Fraternal Alliance. By 1901, the AOOG was the third-largest Michigan member of the Fraternal Congress.

Slocum began to discuss the liability problem both publicly and privately. In an article published in The Fraternal Monitor he wrote:

“The word fraternal will not have the power to transform a few dollars into a thousand dollar bene t for the widow and orphan. When a new member unites with the order we increase our liabilities, but through him fail to increase our accumulating assets in proportion.”

He began to look for something other than the Emergency Fund to protect the Society. At the 1901 convention held in Lansing he sought and received approval to issue a new type of insurance called “Class B.” The new class was not based on assessments but on the whole life principal requiring monthly premium payments. The original certifi cates, now called “Class A,” were paid through assessments averaging six per year. From that time on Class A certifi cates were limited to $1,000. Those who wanted additional insurance bought Class B. That decision placed a limit on future liabilities, but at a level high enough to be worrisome.

Class B insurance was not popular with the members. It was 1907, fi ve years later, before there were enough applications to put the plan into eff ect. Only a period of farm prosperity starting in 1905 kept the waiting period from being even longer.

The Emergency Fund and Class B kept the Gleaner Society well ahead of other fraternals, but it was still not enough. Eventually it took an act of the Michigan

Legislature to solve the problem. An act called the Mobile Law was introduced in the Legislature in 1911 but failed to pass. It was fi nally approved in 1913 despite opposition from some insurance societies. Those who opposed the Mobile Law believed they could not survive if higher rates were charged. The new law required an evaluation of all outstanding certifi cates at the close of business in 1913 in order to compare assets and liabilities. It also required higher rates to ensure that promised benefi ts would be paid. With assets of $461,561, the Society still had to adopt a new rate structure. The issue was placed before the delegates at the convention held in Toledo in 1913.

Slocum told the delegates:

“The Class A can meet the requirements without being transferred to another class, or even paying a rate that is in any way excessive.”

Assessments had to be increased to 10 per year in 1913 and 12 thereafter. The delegates approved the change with only fi ve of 400 voting against. Three of those later changed their vote to yes. You can feel the relief in Slocum’s voice when he said:

”If anyone ever had any doubt as to the future of this organization, those doubts have been expelled.”

The records do not say if Slocum or the AOOG opposed the Mobile Law but if they did the opposition must have been half-hearted. As so often happens in history, timing played a part in the success of the 1913 convention. The fi rst World War started in Europe the following year, leading those nations to import more of their food, and creating farm prosperity in the United States. The new rates were easier to bear and soon became accepted.

At the 1895 meeting it was decided to hold biennial conventions starting in 1897. The practice continues today, interrupted mainly by a four-year period in the 1930s and during World War II. The fi rst biennial meeting was held in Caro on Dec. 28-29, with 80 delegates present. It was recorded that emergency loans had been made to 40 men and 15 women. Death claims totaling $22,750 had been paid since 1894, “all on the lowest rates of any order in Michigan.” Two-thirds of the members were men and one-third women. Delegates heard an offi cer state that 30 new arbors had been created in one 60-day period. At that time there were 190 arbors in 11 counties.

The early Gleaner companions were devoted to the ideals expressed in the rituals. Arbor meetings were well-

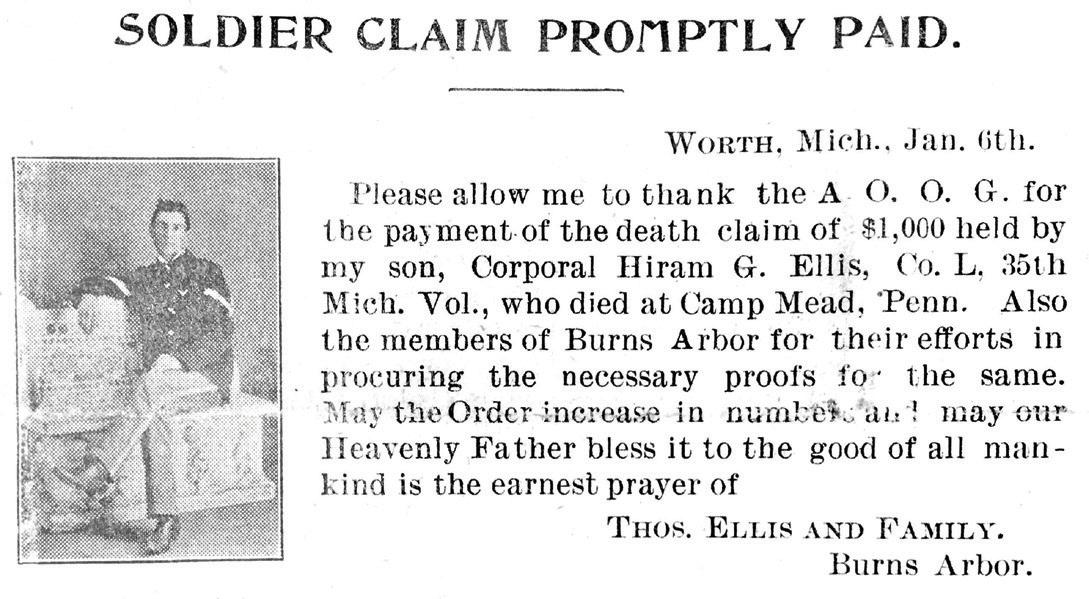

The rst Gleaner member who died in wartime service was Army Cpl. Hiram G. Ellis of Worth, Michigan, in 1898 during the SpanishAmerican War. The Society resolved to pay all service members’ war claims even when not legally obligated. This thank you letter from his parents appeared with a photo of Cpl. Ellis.

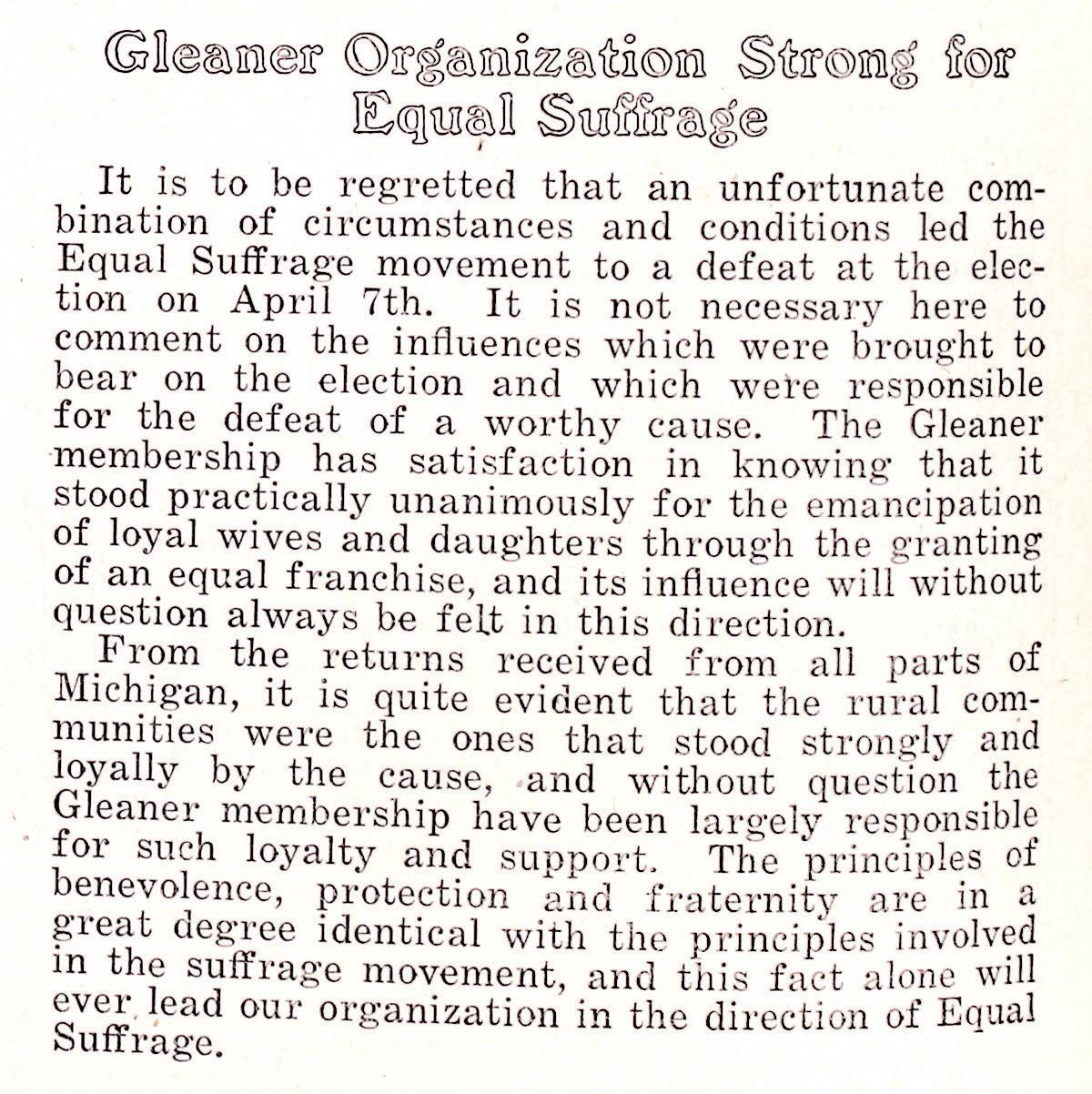

Founding Gleaner bylaws gave women the same rights as men, and the Society pushed for women’s rights to vote for years. This Forum item lamented the defeat of Michigan’s 1913 equal su rage ballot item, but vowed to continue the ght. Grant Slocum led a coalition that in 1917 helped Michigan pass a successful ballot measure.

attended, and members often expressed their support for the Society through the Gleaner newspaper. One of the fi rst projects undertaken by the State Arbor was a scholarship fund. A competition was announced for study at the Fenton Normal School in the spring of 1897. John Kelly was given the award at the biennial convention in 1897. The scholarship program was popular and two scholarships were announced for the next year, one for a male and one for a female.

The fi rst Gleaner picnic recorded in the newspaper was held at Spring Lake Arbor in September 1895. Picnics soon became a part of the Society’s tradition and fraternal activities.

The Spanish-American War of 1898 caused a problem for insurance companies. Some did not have a “war exclusion clause” in their policies to avoid war-related death claims. Eventually the federal government provided special insurance for those in the military, but that was still far in the future. The Society responded by declaring its intention to honor all war-related death claims. The practice was continued during World War I and World War II. The first death in the Spanish-American War was that of Cpl. Hiram G. Ellis of Company L, 35th Michigan Infantry. The decision to pay all war claims is still a source of pride to members of the order.

The Gleaner organization began to develop a distinct personality under the leadership of Slocum. Although offi cially non-partisan, the Society was clearly in tune with the Populist Party and its program. Unlike other fraternals, the Society actively pursued economic as well as social goals. The fi nancial health of the farmer was as important as his spiritual well-being. The Society supported a variety of social causes in the early years. The fi rst article on temperance appeared in The Gleaner in 1898, long before the 18th Amendment to the Constitution temporarily limited liquor sales, manufacturing and transportation. The Women’s Rights Movement was supported in a variety of ways and female suff rage became a special issue for Gleaner members. Slocum personally chaired a federation of dozens of organizations that led Michigan voters to approve a state constitutional amendment in 1918. In

Gleaner leaders at the time of greatest membership recruitment in 1917. Shown from back row to front, left to right: Row 1: Ross L. Holloway, National Secretary; George I. Strachan, Councilman; Dr. M.M. Wickware, Medical Director; William Brown, General Counsel; William Harris, Field; George Carr, Fire Insurance; Harry H. Hough, Ohio State Manager; and “Uncle Tom” Elliot, Field. Row 2: Nathan F. Simpson, Councilman; Frank C. Goodyear, Councilman; John Livingston, Councilman; Henry I. Zimmer, Councilman; Will Wright, Indiana State Manager; Joseph J. England, Chairman of the Council; and J. Floyd McKinstry, Supreme Chief Gleaner. Row 3: Grant H. Slocum, Secretary; Mrs. Elliott; Mrs. Minnie Wright; Mrs. Margaret Goodyear; Mrs. Ada Slocum; Mrs. Elfa Munn; and Mrs. Jennie Zimmer. Row 4: Dr. John M. Ealy, Treasurer; Mrs. J. Floyd McKinstry; Mrs. Minerva Livingston; Mrs. Mary England; Mrs. Leona Strachan; and Miss Mary Holderman, Supreme Chaplain. Row 5: Mrs. Elsie Hough; Mrs. Marvin Harris; Miss Lucia Bellamy, Secretary of Lecture Bureau; and Mrs. William Harris.