N.G. Carrillos

Carlos Zapata and the Reinvention of Modernism

Zapata’s work presents a continuous alternating of oppositions that end up mutually eluding each other: peacefulness answers excessiveness, heaviness answers lightness, straightness-obliqueness, openness-closure, serenity-restlessness, stillness-movement, freedom-necessity. This is why this piece of architecture turns out to be controlled, on the whole. Stridency is only apparent. What is real is the quiet, sensuous taste for shapes and materials.

Aldo Castellano, The Restlessness of Architecture

The Venezuelan architect Carlos Zapata is trying to turn another page in the book of Modernism. He is trying to redefine what is ‘modern’ today by shedding away associations with the movement's shortcomings. After graduating from Columbia in the mid-80’s, Zapata was fortunate enough to find work at the progressive offices of Ellerbe Beckett in New York City. It was here while working under the tutorship of Peter Pran, that he was able to formulate a way to pursue a modernist aesthetic that does not come at the expense of a building’s performance.

Above all things, Modernism lost favor because of its high ambitions for a universality of means and processes ultimately disregarded the specifics of people and place. The proponents of mass production and standardization, while noble in their cause, stalled the evolution of architecture through the adoption of objective tenets such as generalization, repetition, and regularity. By extension, this de-emphasis on project specifics led to the creation of many poorly detailed modernist buildings, fundamentally insensitive to the needs of their inhabitants and the demands of the environment. The architecture of Carlos Zapata, on the other hand, aims to reinvent Modernism by reversing these priorities. In his work, it is not universals but circumstantial particulars such as context, process, and people that determine and ultimately enrich the project's outcome.

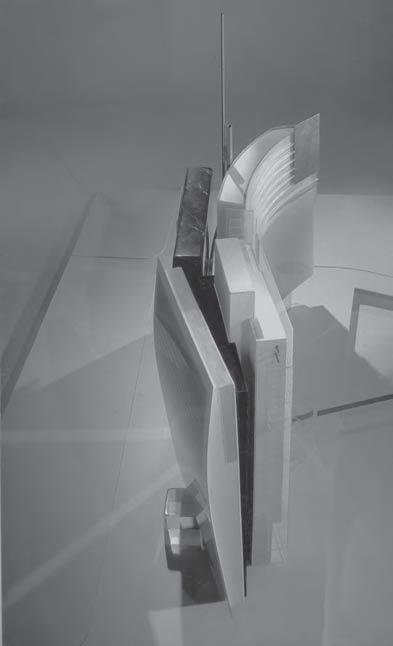

Model. Competition entry for Canadian National Royal Trust Office Building Complex, Toronto, Canada, Ellerbe Becket,1989.

Model. Competition entry for Canadian National Labbats Headquarters, Toronto, Canada, Ellerbe Becket, 1990.

Model. Competition entry for Consolidated Terminal for American Airlines / Northwest Airlines, John F. Kennedy International Airport, New York, Ellerbe Becket, 1988.

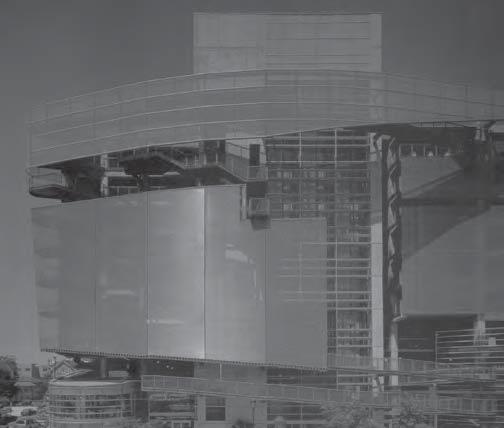

Chicago Bears Stadium & Midway Wood + Zapata

Chicagoland, Indiana, 1996

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

Carlos Zapata’s design process is similar to that of an artist. He is interested in ideas of motion, balance, hierarchy, and proportion. More specifically, he likes to consider the different ‘weights’ of surfaces in a manner not unlike artists who assess equilibrium in their compositions. Given this predilection, it’s not surprising to discover that Zapata’s design process is also very sculptural. He prefers foam models over digital ones. His studio is filled with models which are constantly in the process of development. In effect, it’s this preference for designing in the round that lends his buildings their sculptural quality. However, Zapata is quick to point out that form is only a means to a greater end:

“Form as an end unto itself leads to formalism. This is because this tendency doesn’t go inwards, but outwards. Only a live interior can own a live exterior. Only vital intensity is in possession of formal intensity. Every how is supported by a what. That which is shapeless isn’t worse that which is excessively shaped. The former is nothing, the latter is just showing off. Real form implies real life. But not past or only imagined form. This is the criterion: we don’t evaluate the result, but the beginning of the process of creating forms and shapes. It is precisely this process which reveals whether it was born in itself. This is the reason why the process of the attribution of a form or shape is so important to me. For us life is the decisive factor, in all its fullness, in its spiritual and real bounds.” 1

Similar to Mies, Zapata is also very interested in the expressive quality of materials. Particularly, how these respond when prompted by the introduction of light. As a result, his surface palette tends to favor highly receptive(and complimentary) materials such as aluminum, glass, and stone. Structurally, he prefers steel and concrete over masonry. This last one is completely absent in his body of work.

After establishing his studio in 1991 he continued to develop and mature this unique focus upon the specifics of the project. This approach is evident in both, his built and his unbuilt projects. The U-Penn mixed-use project (1.6), for instance, is a good example of a project that was enriched by its programmatic complexity. Here, his employment of a perforated metal envelope not only provides good overall shading but also unifies the multiple functions within the program. .

1.16 Framing.

Steel tubular catwalk supports.

Built-up steel girder.

Secondary steel framing.

Secondary open-web truss framing.

Skin wind girts.

Pre-cast seating steel “seat.”

Steel bracing.

Steel pipe brace.

Steel pipe-enclosed wide flange columns.

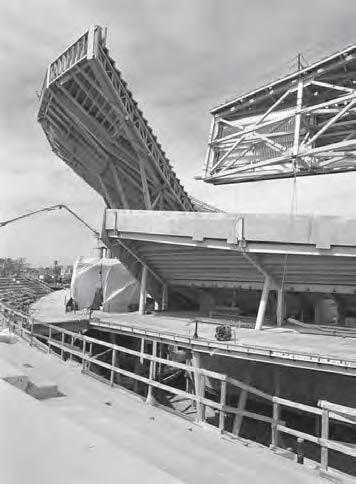

1.17 Under construction. Steel frame.

1.18 Under construction. North scoreboard.

1.19 Under construction.

Bench seating.

STRUCTURE

Zapata does not allow structure to determine the outcome of the design. His emphasis on the contextual specifics keeps him focused on the essence of the project. However, he is not afraid to delve into unprecedented territory; he turns to unconventional solutions if that is what the project requires. Accordingly, his structures often tend to be unconventional. This unconventionality, however, is not to be confused with irrationality. The structure at Soldier Field is a good example of this. Here, to achieve the levitating effect of the new ‘bowl,’ a steel frame system was required. The system is a very straightforward construction. As 1.11 illustrates, the structural framing is composed of massive built-up steel girders (the width of which determines the transversal span of the new bowl) that take up the load of the bench seating area and distribute it down to the columns below through plate connections. To prevent the lateral movement of these girders, secondary steel framing (in the form of open web steel trusses and steel I beams) and steel bracings are provided. The angled wide flange columns, which are doing the most work in the system, are further reinforced through the use of steel pipe braces. The steel tubular catwalks, which I will expand upon later, are here to provide access for the maintenance of the field light strip band that hovers above the bench seating section. These are connected to the steel girders through a welded plate connection. In addition, steel skin wind girts are introduced to provide support for the stainless steel interlocking planks that clad the exterior of the bowl. Lastly, pre-cast steel seats were included to provide a joint connection from which to attach to the fan’s seats. Images 1.12 and 1.14 show the way this system looked as assembly was being carried out. Image 1.12 shows the ‘cracks’ introduced in the latter stages of the design phase. As previously outlined, these were introduced to maximize the views of the urban scale at large, thereby making a contextual connection with the city.

1.21 Curtain wall at south.

1.22 Curtain wall at bedroom.

1.23 Curtain wall at bedroom. 1.24 Model.

KLEIN RESIDENCE

Similar to Asplund, Aalto, and Neutra before him, Zapata is deeply focused on the role of sunlight in his projects. However, unlike these architects, his interest in sunlight stems not from an architectural perspective, but from a cultural one. In the following passage, the architect discusses both his design approach and his lifelong fascination with sunlight::

If we stop at pure geometry, we create a house that doesn’t take the outside into consideration, nor natural light or the very site of the house. I pull volumes away from each other to create spaces that allow light in which can control moods and create a sort of excitement: light moving along a wall is pleasant to behold. When certain spaces are opened and slanted, light can pass through and space starts moving. In the living room I created an aura of light similar to that which hangs over the heads of saints in South American religious paintings by making light filter through the sides of the suspended ceiling. When these possibilities have been explored, it is hard to go back to boxes.” 3

This fascination with light is a guiding principle that transcends through his body of work. However, he does not begin with light. Instead, he always looks to context for inspiration. In the case of the Klein Residence, it was the project’s site, a cliff’s edge overlooking the Andean mountains, which provided the impetus for formal manipulation. The architect sculpturally shaped the building to formally respond to the site. He then pushed and pulled planes apart to allow for the introduction of light into the interior spaces. To further intensify the effect, he then followed by introducing a curtain wall at the south face, thereby creating a stronger connection with the site and the elements.

NATURAL LIGHT AND SURFACE

At Soldier Field, just as in the Klein Residence, light once again resurfaces as a primary guiding principle in Zapata’s work. Here is also where this is achieved through the employment of a curtain wall. The versatility of this system proved ideal for the fulfillment of the designer’s intentions. Through its inclusion they were able to accomplish three complementary objectives with only one system: first, the maximum introduction of natural light; second, the employment of one continuous skin; and finally, the introduction of surface texture. This last objective was achieved through a dynamic interplay between mullions and glazed surfaces.

New Stadium at Soldier Field Wood + Zapata Chicago, Illinois, 2003

1.25 Primary and secondary structure at curtain wall.

A Steel column.

B Primary girder.

C Cross girder.

D Edge beam.

E Vertical aluminum mullion. The mullion is continuous throughout.

F Horizontal aluminum mullion.

G Steel shelf angle. Continuous structural support.

H Galvanized steel angle support. The angles support the mullions from the edge of the slab.

I Vertical structural steel support.

J Vertical sag rod.

K Horizontal structural tubing.

1.26 Curtain wall at Promenade.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY STRUCTURE

The structural clarity at Soldier Field is pervasive throughout. At the building’s perimeter, the clear distinction between primary and secondary structures is yet another example of this principle. At each level, primary girders run transversally, supported by columns that span continuously from foundation to ceiling. Cross girders and edge beams pick up the live and dead loads in their respective levels and transfer them onto the columns. These beams are fastened onto the primary girders through the use of bolted steel plates and angles. The entire curtain wall system is bolted onto galvanized steel angles embedded into the slab’s edge. The system is additionally supported at ground level through the employment of vertical steel rods anchored upon a horizontal steel tube that runs parallel to the wall. This rectangular tube, in turn, is connected to the primary structure through another tubular steel member. The vertical mullions of the system run continuously throughout the entire height of the wall. At the louver section, however, they are substantiated by vertical structural steel support. From top to bottom, the sequence goes as follows: the upper vertical mullions sit upon shelf angles, and the shelf angles are attached to vertical supports, which, in turn, span behind the louvers and the shadow box before finally reconnecting back to vertical mullions at the lower end. The attention given to these structural connections is very thorough. This, however, is not surprising given Zapata’s adherence to sound detailing principles.

THERMAL MOVEMENT

Another characteristic of the curtain wall that deserves further consideration is the precautions taken to prevent thermal movement. The curtain wall at Soldier Field addresses this issue in two ways: through the use of interlocking split aluminum mullions and the introduction of expansion joints. As employed in some of the masterpieces of High Tech architecture, such as the Lloyd’s of London (Richard Rogers), the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (Norman Foster), and the Institut du Monde Arabe (Jean Nouvel), the split mullion is a means to prevent the movement created by the expansion and contraction that materials undergo as changes in temperature occur. As noted in Jean Nouvel’s Institute du Monde Arab, another good reason to use this type of mullions is the added flexibility they provide in the assembly process.4 At Soldier Field, where the curtain wall curves continuously, this type of system was not only advantageous but essential. The reason for this is because the assembly of the curtain wall required the employment of a mullions system that could

New Stadium at Soldier Field Wood + Zapata Chicago, Illinois, 2003

1.27 Roof section.

A Primary girder.

B Galvanized steel angle support.

C Edge beam.

D 1/2” dense glass substrate.

E 3” metal roof deck.

F Vapor barrier.

G 3” rigid insulation.

H Single ply TPO membrane. 5/8” cement board with metal stud support.

J Setting wood block.

K 1/8” thick aluminum coping, PVDF coated.

L Galvanized sheet metal closure.

M Cant strip.

N GL-5: 1/4” thick shadow box glass.

O Snap-on aluminum cap, PVDF coated.

P 3” thick semi-rigid insulation with galvanized sheet metal back pan.

Q Painted sheet metal shadow box. This system is used to add depth to the wall.

R GL-4: 1” thick insulated vision glass with frits.

S Aluminum trim, finish to match enclosure system.

T Hung gypsum panel ceiling.

U Spring isolation hangers.

1.28 Wall section.

A Primary girder.

B Edge beam.

C 6” concrete slab on 3” metal deck.

D 4” vinyl base.

E Cant strip.

F 5/8” gypsum board with metal stud support.

G Aluminum sill finish with back support,

H Vertical aluminum mullion, PVDF coated. GL-4: 1” thick insulated vision glass with frits.

J Snap-on aluminum cap, PVDF coated.

K Steel shelf angle. Continuous structural support.

L Vertical structural steel support.

M 3” thick semi-rigid insulation with galvanized sheet metal back pan.

N Aluminum panel, PVDF coated.

O Galvanized steel angle support.

P Steel bracket attached to edge of slab.

Q Custom extruded aluminum louvers with insulated sheet metal blank off between ducts, PVDF coated.

R GL-3: 1 1/4” thick laminated-insulated glass with frit.

S Aluminum trim, finish to match enclosure system.

T Vertical sag rod.

U Wood ceiling planks supported by 16” stud framing.

be adjusted, or tilted, to account for the curvature of the wall. In addition to this system, Zapata also employs expansion joints at intermittent intervals with the mullions. Expansion joints act to prevent thermal movement in the same manner that split mullions do. At Soldier Field, given the mass quantities of concrete employed, this type of system was essential to the safety and overall success of the project.

INSULATION

The inappropriate insulation of surfaces is one of the harshest criticisms lashed against the early modernists. Some, like Frank Lloyd Wright, ardently believed that it was not necessary to insulate walls or floors at all. According to Wright, only roofs and the building’s edge (at grade) required insulation. Rudolph Schindler, having worked for some time at Wright’s office, carried on with these mystical practices. A crowd favorite amongst architects, Le Corbusier, also contributed his part to the damage. According to Ford, the Swiss-born architect had no concern, or perhaps no interest, for the implications of environmental impact upon architecture. Last, but not least, we could not talk about bad detailers without mentioning Eero Saarinen. This ‘talented’ architect further cemented the public’s distaste for modernism by making an enfilade of poorly insulated steel buildings throughout America. Carlos Zapata breaks away from these examples by providing for the proper insulation of surfaces in line with the conventions of current practice. In particular, the insulated glass system employed at Soldier Field deserves further consideration. Zapata uses three types of glass for the curtain wall. By his emphasis on design specifics, each of these serves a specific purpose. The roof section on 1.27 illustrates how two of these are applied. GL-5 is a single pane glass of 1/4” thickness. Its application is similar to that of spandrel glass on conventional office buildings. The only difference here is that it also acts, in conjunction with the recessed aluminum shadow box behind it, as a means to activate the wall by giving it an added sense of depth. Below the shadow box glass is the GL-4. This is a 1” thick insulated vision glass with ceramic frits. This type of glass is very convenient to use in applications where the reduction of sun glare is of particular importance. Last but not least is the GL-3. This is a 1 1/4” thick laminated-insulated glass with ceramic frits used particularly for curtain wall applications. The only difference between the GL-3 and the GL-4 is that the GL-3 comes with a thicker glass pane that has been laminated to protect against impacts and to account for the added angle of incidence the sun creates at ground level.

17 Carlos Zapata and the Reinvention of Modernism

1.29 Alternate roof section.

A 1/2” dense glass substrate.

B 3” rigid insulation.

C Single ply TPO membrane.

D 5/8” cement board with metal stud support.

E 1/8” thick aluminum coping, PVDF coated.

F Setting wood block.

G Insulated aluminum panel system, PVDF coated.

H Galvanized sheet metal closure.

I 3” metal roof deck.

J Galvanized steel angle support.

K 4” X 4” galvanized steel tube.

L Panel clip and fastener.

M Primary girder.

N Edge beam.

1.30 Alternate wall section.

A B C D E F 6” concrete slab on 3” metal deck. 4” vinyl base. Cant strip.

5/8” gypsum board with metal stud support. Aluminum sill finish with back support, PVDF coated.

GL-4: 1” thick insulated vision glass with frits.

G Snap-on aluminum cap, PVDF coated.

H Galvanized steel angle support.

I Steel bracket attached to edge of slab.

J Insulated aluminum panel system, PVDF coated.

K Primary girder.

L Edge beam.

ALTERNATE WALL SYSTEM

The alternate details I propose are a modification of Zapata’s details at the Soldier Field curtain wall. In my analysis of his details, three themes stand out with consistency: light, form, and materials. Light is the source of inspiration, form is the means to introduce light, and materials respond through performance and expression. In the alternate sections (1.29 and 1.30), I substituted Zapata’s glazed curtain wall system with a perforated aluminum panel system (also known as a rain screen). Light is addressed by replacing the stadium’s floor-to-ceiling glazed wall with an insulated/ fritted window encased in an aluminum frame. The triangular mullion caps in Zapata’s wall system have been substituted with flat aluminum caps. In Zapata’s wall, these caps contributed by giving volume and adding texture to an otherwise homogeneous surface. In this version, however, since the aluminum panels are already providing the needed texture, the inclusion of triangular protrusions is of little assistance. The form remains loyal to Zapata’s version. Zapata’s diagonals are not unsound. They are formal responses to contextual and programmatic needs. Here, as in Soldier Field, the intent behind the diagonal tilt of the wall is to maximize the amount of light that enters the interior spaces. Finally, I believe that the introduction of a textured, pressuredifferentiating, anti-corrosive system such as the aluminum rain screen would be very much in keeping with Zapata’s criteria for material selection.

FIRE PROTECTION AND MATERIAL DETERIORATION

At Soldier Field, the argument of whether to use a monolithic or a layered system of construction did not exist. Due to the fire hazard it represents, building codes in the United States do not allow the use of exposed steel in buildings that are taller than three stories. During the 50’ and 60’s, both, Mies and Saarinen built a large number of monolithic exposed steel buildings in America. These buildings, in addition to posing a fire threat, required a lot of maintenance and performed very poorly in aspects of thermal efficiency. Zapata, by contrast, confronts these issues head-on at Soldier Field. To prevent fire hazards, all structural steel has been insulated: spray-on foam insulation has been used for the beams, and steel deck and gypsum boards have been used for the columns. This practice also eliminates the thermal bridges that are created when steel is left exposed. As an additional precaution, safing, a fire and smoke retardant, has been inserted into the gaps between the slab and curtain wall. Aluminum is one of Zapata’s favorite materials to use. As we can see from sections 1.27 and 1.28, he employs it heavily throughout the entire

19 Carlos Zapata and the Reinvention of Modernism

New Stadium at Soldier Field

Wood + Zapata

Chicago, Illinois, 2003

1.31 Section at Promenade/Concourse level.

A Vertical sag rod.

B Vertical aluminum mullion, PVDF coated.

C GL-3: 1 1/4” thick laminated-insulated glass with frit.

D Horizontal aluminum mullion, PVDF coated.

E Snap-on aluminum cap, PVDF coated.

F Fin tube radiation, coated to match curtain wall.

G Expansion joint.

H Aluminum sill starter coping, PVDF coated, continuous at curb.

I New concrete slab with 5” higher ADA detection curb.

J Secondary steel concourse framing.

K Primary girder.

L Steel column.

1.32

A B C D Section at Promenade/Concourse level. New concrete slab with 5” higher ADA detection curb. Snap-on aluminum cap, PVDF coated.

GL-3: 1 1/4” thick laminated-insulated glass with frit. Aluminum sill starter coping, PVDF coated, continuous at curb.

E Expansion joint.

H Fin tube radiation, coated to match curtain wall.

G Primary girder.

H Secondary steel concourse framing.

I Cross beam.

J Steel column.

K Slide connection for expansion joint.

1.33 Interior at Concourse level.

1.34 Detail of curtain wall structural support.

A Steel column.

B Vertical sag rod.

C Galvanized steel angle support.

D Snap-on aluminum cap, PVDF coated.

curtain wall; the mullions and their caps, the ‘shadow box’ panels, the trim, the sill, the parapet’s coping, the expansion joint coping, and even the diffuser are all made of aluminum. It is important to note that all of these examples have been PVDF coated to prevent their corrosion. The advantages that aluminum has over exposed steel are many. It can be extruded in a variety of shapes, it can be easily insulated, it can be painted to match any finish and it can, as formerly mentioned, also be left exposed to the elements.11 With all these considerations in mind, it is easy to see why Zapata likes it so much.

VENTILATION

In a building the size of Soldier Field, issues of ventilation are of great concern. It is imperative that this type of buildings is allowed to ‘breathe’ and distribute air properly in order to prevent condensation and moisture buildup in its surfaces. At the curtain wall, Zapata addresses these concerns in two ways: through the use of louvers and diffusers. The introduction of natural ventilation through the employment of aluminum louvers allows the building to minimize the moisture content and the mildew build up that can occur when surfaces are not provided with a means from which to ‘breathe’ property. The choice of aluminum, as previously outlined, is a very sound one when you take into consideration the fact that these components will have constant exposure to the elements. In 1.28 we can witness the manner in which this system is supported through the employment of a vertical structural member. At the base of the curtain wall, Zapata prevents the buildup of condensation and heat loss through the use of a fin tube radiator. This type of ventilation system is a form of radiant heater/cooler that essentially operates by forcing the flow of hot/cold water through a copper pipe and allowing it to radiate over to the desired spaces/surfaces. Frank Lloyd Wright pioneered its use very early on and influenced others such as Richard Neutra to follow in the same footsteps. More recently, the High Tech architects have adopted similar systems for inclusion in their curtain wall applications. Among some of the seminal buildings of the twentieth century that include some variation of this systems are Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel 1922, Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal at JFK, Richard Roger’s Lloyd’s of London and Norman Foster’s Hong Kong and Shanghai building.

A B C D E F G H

MATERIAL SELECTION

Throughout the 20th century, architects and artists have been preoccupied with the search for the appropriate means to express motion. The Futurists and the Russian constructivists were not so much concerned with the mechanics of the objects they studied as much as they were fascinated with their surface appearance. Similarly, Le Corbusier, in his study of the machinery of the new age, only did so at surface value. Perhaps it was not until Eero Saarinen’s office conducted its research of industrial objects that the real value of these objects came to be applied in architecture. Despite his shortcomings elsewhere as an architect, it is in this area where Saarinen redeems himself as a true innovator. Saarinen’s adaptation of industrial components such as gaskets and Cor-ten, taken from the automobile and rail industries respectively, set a precedent for future material exploration. The British architect Norman Foster followed suit by conducting substantial research into the aircraft industry. From these studies, principles such as the ‘tolerance’ of materials (and craftsmanship) have been adapted into the design of his buildings. However, Foster does not deny that his appeal for aerodynamic design is both, intellectual and aesthetic. Neither does designer Carlos Zapata. As an architect fascinated with motion in architecture, he has also sought to find the appropriate means of expression. Just like Foster, he looks to find materials that can marry aesthetics and functionality. A good case sample can be found in his employment of tubular steel. The drawings on 1.35 and 1.36 illustrate the application of tubular steel at the Soldier Field ‘light band.’ As we can see from these drawings, the material is employed for more than just one use: it is employed for the members of the truss, the handrails of the catwalk, and as the supports for the field lights. Its appeal to Zapata is understandable. The curvilinear nature of the material is very much in keeping with his will to streamline. In addition, as Frampton has noted, the form provides ‘greater strength with the economy,’ since it ‘concentrates the cross-sectional area away from the center of gravity.’ In short, it marries strength and beauty, which, as noted before, is exactly the type of all-inclusive quality that Zapata looks for in materials.

ENCLOSURE AND SUPPORT

It is amazing to see the multiplicity of applications that light gauge steel is used for in layered architecture. Prior to interning at Wood + Zapata, I imagined that a lot of these structural elements were custom-made works of art. I now realize that nothing could be further from the truth.

1.36 Section at lightband.

A Perforated steel tubular arm.

B Tubular steel truss.

C Field light, spaced continuously 24” o.c.

D Transformer.

E Steel catwalk grating.

F Handrail.

1.37 Section at enclosure.

A Perforated steel tubular arm.

B Corrugated stainless steel panel enclosure.

C Open-web truss.

D Light-gauge steel framing.

E Steel channel.

F Stainless steel interlock grating plank.

In actuality, in steel construction, just about anything that needs to be braced or supported is done with nothing more than steel studs, plates, and angles. At Soldier Field we see light gauge employed just about anywhere: at the knee wall, supporting the mullions, bracing the ceilings, and even used to make the formwork of sculptural elements such as the curved rim at the top of the cantilevered bleachers. In the section on 1.37, we can truthfully attest to the versatility of light gauge steel. Essentially, the rim’s formwork is composed entirely of light gauge construction. Initially, studs extend from the uppermost trusses (whose job at this point is to brace the steel tubular arms) and connect to a curved light gauge member that has been extruded to take the shape of the rim. Steel channels, in turn, brace these curved members and, in conjunction, all of these provide the necessary support for the corrugated steel envelope to anchor onto. On the bleacher side, the same method it is employed once again. The only difference on this side is that only straight members are applied to create the siding’s support. Here again, as in the curtain wall, we see how Zapata employs different materials at the point where forms shift in another direction. In the same manner that aluminum channels provide a transition for the glass at the curtain walls, corrugated steel is hereby employed to provide the transition from the grating planks onto the tubular steel arms. The decision to employ corrugated steel at these transitional points, it must be added, is not one solely based upon aesthetics, but also upon the appropriateness of the material’s inherent qualities. Buckminster Fuller was one of the first to pioneer the use of this material in his Dymaxion Deployment Units (D.D.U). The material’s supplementary strength (created by the ridges), and its ease of fabrication were the ideal qualities Fuller sought in a material well suited for housing mass production. In addition to these qualities, the gauge thinness of corrugated steel lends itself to ease of formal manipulation. More so, at least in the economic sense, than it would be to do with other materials such as glass or masonry.

CONCLUSIONS

The architecture of Carlos Zapata is redeeming the name of Modernism through a critical re-evaluation of its values. This mission has to be thorough in conception in order to acquire true significance. As we have witnessed from an analysis of his work, he does not disappoint. On the contrary, he appears to be doing a pretty good job so far.

1 Castellano, Aldo. “The Restlessness of Architecture.” Carlos Zapata. The Restlessness of Architecture. (Milan: l’Arca Edizioni, 1996), p.26.

2 Ibid. p.12.

3 Giovannini, Joseph. “Wood + Zapata: Soldier Field.” Architectural Record. May 2004, p.120.

4 Ford, Edward R. The Details of Modern Architecture, Volume 2:1928-1988. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 397.

5 Ford, Edward R. The Details of Modern Architecture, Volume 1. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1989, p.337.

6 Ibid. p.293.

7 Ibid. p.247.

8 Ford, Edward R. The Details of Modern Architecture, Volume 2:1928-1988. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 269.

9 Allen, Edward. Fundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and Methods, 3rd edition. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1999. p.389.

10 Ford, Edward R. The Details of Modern Architecture, Volume 2:1928-1988. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 269.

11 Allen, Edward. Fundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and Methods, 3rd edition. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1999. p.718.

12 Ford, Edward R. The Details of Modern Architecture, Volume 1. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1989, p.247.

13 Ford, Edward R. The Details of Modern Architecture, Volume 2:1928-1988. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 395.

14 Ibid. p. 16.

15 Ibid. p. 271.

16 Frampton, Kenneth. Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture, ed. John Cava. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1995, p. 211

17 Ford, Edward R. The Details of Modern Architecture, Volume 2:1928-1988. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 387-.