CCAS

I assumed the position of director in July 2023. Reflecting on this past academic year as director of CCAS, I see the many ways in which CCAS continues to play an important role in providing space for diverse and critical perspectives on events in the Arab world. One important role that CCAS has filled over the years has been to respond to current events in the region and to support members of our community effected by such events. Our first event this academic year was on the crisis in Sudan, and we held a second Sudan event in the spring semester. We also held events covering a range of issues in diverse contexts including Yemen, the Arab Gulf, and Lebanon. After the attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023 in which 1,139 Israelis were killed (including 695 civilians), and the subsequent war on Gaza, we quickly mobilized to organize several events meant to provide history, context, and analysis about Israel and Palestine.

We have dedicated this issue to our engagement with Palestine. This is only fitting given the ongoing genocide in Gaza in which Israeli occupation forces have killed, maimed or disappeared nearly 5 percent of the Palestinian population in Gaza since October 2023. In the West Bank, Israeli occupation forces have killed over 400 Palestinians since Oct. 7 and Israeli settlers continue to rampage through Palestinian communities burning homes and cars, as well as attacking Palestinians, resulting in several killings in this period. At the same time, 133 Israeli hostages continue to be held by Hamas. In this very difficult time, members of our community have responded by teaching, writing, speaking, protesting, and supporting and caring for others. Some of these efforts are captured in this newsletter.

The Israeli war on Gaza has also decimated the Palestinian education system in Gaza, destroying every university and over 75% of schools. In the months and years ahead, I hope that we in CCAS can work to support our Palestinian colleagues and students in restoring and rebuilding Palestinian higher education. Thanks to generous donations from members of our community, we will also be able to provide scholarships to Palestinian students for this coming academic year. I would also like to take this time to acknowledge the passing of two long standing members of our community. Professors Halim Barkat and Ibrahim Oweiss were pillars of our CCAS community and we were honored that their families chose to hold their memorials at Georgetown.

The CCAS Newsmagazine is published twice a year by the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, a component of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Fida J. Adely, Associate Professor and Clovis and Hala Salaam Maksoud Chair in Arab Studies; Director, Center for Contemporary Arab Studies

Killian Clarke, Assistant Professor

Marwa Daoudy, Associate Professor and Seif Ghobash Chair in Arab Studies

Rochelle A. Davis, Associate Professor and Sultanate of Oman Chair; Director, Graduate Studies

Joseph Sassoon, Professor and Sheikh Sabah Al Salem Al Sabah Chair

CORE AFFILIATES

Mohammad AlAhmad, Assistant Teaching Professor

Belkacem Baccouche, Assistant Teaching Professor

Noureddine Jebnoun, Adjunct Associate Professor

AFFILIATES FROM OTHER DEPARTMENTS

Osama W. Abi-Mershed, Associate Professor, Department of History

Mustafa Aksakal, Associate Professor, Department of History

Jonathan Brown, Professor, ACMCU and Department of Arabic & Islamic Studies

Elliott Colla, Associate Professor; Chair, Department of Arabic & Islamic Studies

Felicitas M. M. Opwis, Associate Professor, Arabic & Islamic Studies

Suzanne Stetkevych, Sultan Qaboos bin Said Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies

EMERITI FACULTY

Judith Tucker, Professor Emerita, CCAS and the Department of History

Dana Al Dairani

Senior Director of Programs

Susan Douglass K-14 Education Outreach Director

Dharini Parthasarathy

Assistant Director of Academic Programs

Coco Tait

Events and Program Manager

Vicki Valosik

Editorial Director

Editor-in-Chief Vicki Valosik

Design Adriana Cordero

An online version of this newsletter is available at http://ccas.georgetown.edu

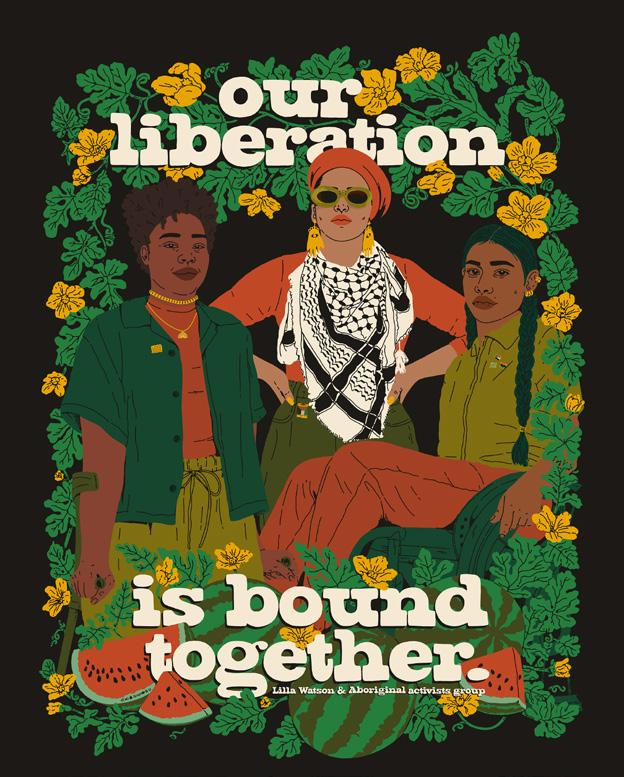

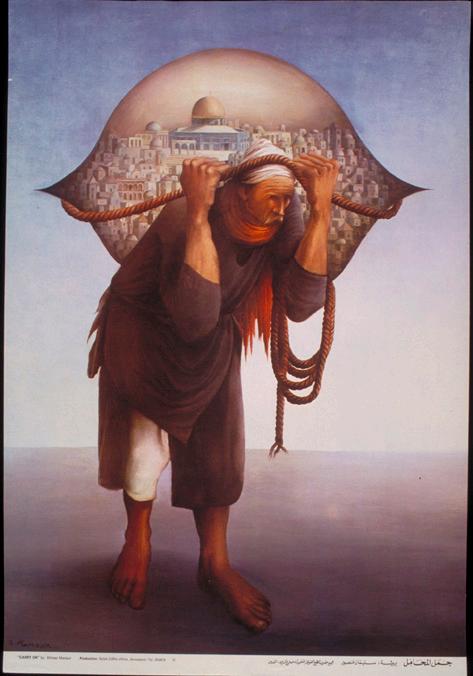

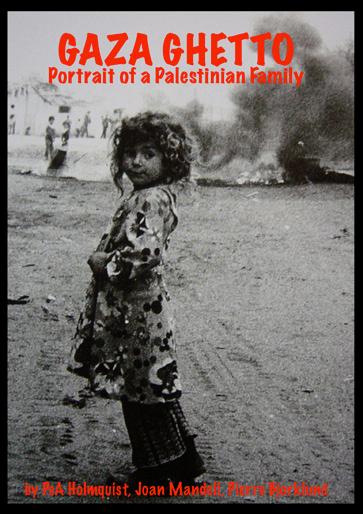

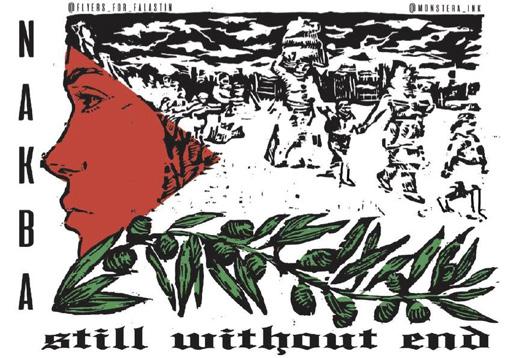

This issue, which is themed around Palestine, is illustrated with a series of “Palestine posters” from the collections of the Palestine Poster Project, the world’s largest archive of Palestine posters (numbering over 20,000).

The Palestine Poster Project was founded by MAAS alum Dan Walsh, whose passion for the genre first began in the 1970s when he was serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Marrakesh and practiced his language skills by trying to translate text on the posters that papered the buildings around town. One day, he paused to study a poster hanging outside of what happened to be the PLO headquarters in Morocco. A man invited him inside, and after a lengthy conversation, Walsh left with a dozen posters under his arm and an invitation to come back any time. “That’s how it all began,” he said. Upon returning to the US, Walsh launched his own design and distribution company and continued to build his poster collection. However, he says that he continued to understand the genre primarily from the “perspective of an activist and artist” until he joined the Master of Arts in Arab Studies program at the age of 55 and gained the “sort of intellectual architecture visual anthropology requires.” With the support of his professors, particularly Rochelle Davis, the Palestine Poster Project began to take shape.

The Palestine poster genre, which dates to the early 1900s, grew exponentially as a form of resistance and expression following the 1967 war. As the art journal Widewalls notes, “Palestinian posters provided a way to rebel, maintain hope, and sustain a collective identity during a decades-long fight for freedom—an act of rebellion and a manifestation of resilience through art.” The genre has continued to evolve and thrive, and according to Walsh, more Palestine posters are being created and distributed today than ever before. “Unlike most of the political art genres of the twentieth century such as those of revolutionary Cuba and the former Soviet Union, which have either died off, been abandoned, or become mere artifacts, the Palestine poster genre continues to evolve,” writes Walsh. “Moreover, the emergence of the Internet has exponentially expanded the genre’s network of creative contributors and amplified the public conversation about contemporary Palestine.” Given this evolution, most posters we selected for inclusion in this issue were produced in the last seven months and illustrate the relevance and vibrancy of the genre to today. We are thankful to the artists, the Palestine Poster Project, and Flyers for Falistin for allowing us to share these works.

Here are a few highlights of the recent activities of CCAS faculty

“Creative Insecurity: Institutional Inertia and Youth Potential in the GCC ” (Hurst, June 2023) – Dania Thafer

“Palestine and USA,” chapter in Between Diplomacy and Non-Diplomacy: Foreign Relations of Kurdistan-Iraq and Palestine (Springer, 2023) - Khaled Elgindy

“The Impact of the October 1973 War on the Palestinians,” chapter in The 1973 ArabIsraeli War (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023) –Khaled Elgindy

This spring, the CCAS community was pleased to welcome the Middle East Studies Association of North America (MESA), which relocated its DC headquarters to our center. MESA is a non-profit learned society that seeks to foster the study of the Middle East, promote high standards in scholarship and teaching in the field, and encourage public understanding of the region through programs, publications and education. “MESA is the preeminent association for Middle East studies,” said CCAS Director Fida Adely. “Our Center is an ideal fit as an institutional host since we share common interests in scholarship, research, programming, and teaching on the broader MENA region, and we represent a similar interdisciplinary combination among our CCAS faculty.”

“Stop playing politics with Palestinian lives” (The Hill, August 2023) - Khaled Elgindy

“In Search of My Family’s Home in PreNakba Palestine” (New Lines Magazine, November 2023) – Marwa Daoudy

“Gaza, Yemen, Syria, Human Rights, and Oil: The Elephants in the COP28 Room” (New Security Beat, November 2023) –Marwa Daoudy

“Israel Has Ruined 76 Percent of Gaza’s Schools in Systematic Attack on Education” (truthout, March 2024) – co-authored by Fida Adely

“ Water, health, and peace: a call for interdisciplinary research” (The Lancet, March 2024) – co-authored by Marwa Daoudy

“Gaza Ghetto: How to make a film under military occupation” (Jumpcut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 2024) – Joan Mandell

“Le projet très politique d’Israël et des Émirats avec la Jordanie” – Interview with Prof. Marwa Daoudy

“State autonomy, economic reform & business elite influence in the GCC ” (New Political Economy, January 2024) – Dania Thafer

“ Teaching during a time of war: Three faculty leaders reflect ” (Conversations on Jesuit Higher Education, February 2024) – co-authored by Fida Adely (reprinted on page 5 of this issue)

“As COP28 looks at conflict-climate overlap, northwest Syria should be exhibit A” –Interview with Prof. Marwa Daoudy by The New Humanitarian

“In Gaza, Israel is waging an invisible environmental war ” – Interview with Prof. Marwa Daoudy by The Hindu

“Bringing Awareness Through Research” – Feature on Prof. Marwa Daoudy in SFS Magazine

This spring, CCAS bid a bittersweet farewell to MAAS Assistant Director of Academic Programs Kelli Harris, who served in that position since 2009, and prior to that in Georgetown’s Arabic and Islamic Studies Department, for a total of 16 years of service at Georgetown. We wish Kelli all the best in her new endeavor as a PhD candidate in Lifelong Learning and Adult Education at the University of Pennsylvania. We will see you at the next debka line, Kelli! We were also pleased to welcome Dharini Parthasarathy, who joined the Center as the new Assistant Director of Academic Programs in April. Dharini holds an MS in Learning Experience Design from Brandeis University, an

MA in Higher Education and Student Affairs from New York University, a BS in Electrical Engineering and a BS in Mathematics and Statistics from Miami University. Prior to joining the Center, Dharini worked at NYU Abu Dhabi in the Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Community Programs as an Instructor and Learning Designer. In this role, she advised students, supported recruitment, designed a college readiness course for high-achieving Emirati high school students, and served as an assistant instructor.

Professors Nader Hashemi, Jonathan Lincoln, and Fida Adely, each of whom direct academic centers within Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, reflect on what it means to educate and care for students in this present moment.*

The Israel-Gaza war has quickly morphed into a global crisis. It has produced deep polarization in the United States and its university and college campuses. As a professor and academic director who teaches Middle East studies, I have adopted a two-pronged approach to support students. First, I have tried to help students who are most impacted by this war. I know they are struggling and hurting. I have devoted extra office hours to meet with students and encouraged them to contact me to discuss any topic on their minds. Some students have accepted my offer, others have not. I have repeatedly let them know that my office door is always open. Secondly, as an educator, I have spent considerable time in my classes devoted to an open and uncensored discussion of the Oct. 7 crisis in Israel/ Palestine. Students were eager to engage and discuss their views on this crisis. I felt I had a moral and pedagogical obligation to do this.

intellectually unsafe, to force you to confront ideas that you vehemently disagree with.”

I have used this as my guide during this Middle East crisis. I have advised students

giving counsel on political discourse that can avoid the perception of bigotry. Specifically, I have encouraged students to adopt an international law framework when publicly debating the Israel/Palestine conflict.

“Just

Today, there is a popular view among university and college administrators and some faculty that a key goal of a college education is to protect students from harm. My view is informed by an eloquent formulation from Van Jones, the prominent African-American public intellectual. He astutely observed that the goal of a college is to keep students “physically safe but

on how to respond if they feel physically harassed or intimidated. Since Oct. 7, there has been a surge in reports of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. I have counseled students on how to react in these contexts, including

More broadly, during moments of an international crisis, educators have a unique ethical responsibility to educate. I have understood this to mean that we need not less, but more public debate, discussion, and dialogue. The challenge is to do so constructively and with civility. This is especially needed in this moment, given the enormous human rights crisis in Gaza and the partisan role the United States has played in this drama. At SFS, we have organized a Gaza lecture series co-sponsored with several units on campus, and we have encouraged our dean to use his authority to organize public fora devoted to a critical and respectful engagement of this topic. There is a tendency during moments like this to shy away from political controversy with the hopes that the crisis will pass, and calm can be restored on campus. My view is the exact opposite. Global crises are teaching moments. We have a moral obligation to seize these moments and to do what we were hired by the institution to pursue, to educate our students.

The brutality of the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas on Israel and the subsequent war in Israel and Gaza have left many students and faculty in something akin to a state of shock. Although these events are happening far away from campus, many in our wider community, including students and faculty from Israel, have been directly affected—both personally and professionally. Students have reacted in a variety of ways. Some have turned to activism while others have retreated to safe spaces off campus. Some have found solace in one or more student groups, religious institutions, or academic communities.

Still, there is no single formula and our students have a wide range of experiences, opinions and connections to this conflict. Unfortunately, some have been less fortunate and found the prevailing atmosphere on campus stifling and even unwelcome, either to certain points of view or even for some merely seeking to understand the complexities of the debate. Along with our dedicated faculty, the Center for Jewish Civilization (CJC) has endeavored to respond by providing the necessary academic and social support to our students as they navigate these unprecedented times.

First and foremost, from an academic perspective, we have made space in the various courses we offer on the history and politics of the conflict to discuss and contemplate the ramifications of the war. We have also produced several events, often together with other academic centers and programs, for the broader university community to hear from our faculty and outside experts and engage in debate. Finally, we have set aside time each week to host a breakfast for students and faculty to meet, discuss issues and share thoughts and concerns related to life on campus, current events and other topics, all in a welcoming and judgment-free environment.

While students at the CJC come from diverse backgrounds, the acute rise in antisemitism across the country and in many parts of the world—something that predates the war—has also had a particularly worrying impact on the students we serve. Antisemitism extends far beyond Georgetown’s campus, but sadly our campus is not immune. We are thankful for the support the University has provided in addressing many of these concerns.

Overall, we are proud to be part of this academic community and identify strongly with the Jesuit commitment to holistic education. This is certainly a difficult period but as we hope and pray for a more peaceful future, we also reaffirm our shared commitment to our students and their wellbeing.

These have been trying, painful, and bewildering times for many of the students I teach, advise, and encounter in my role as a professor of Arab Studies. Many are from the Arab world or have lived and worked there. Many felt dehumanized and ignored because of the way in which the events in Israel and Palestine were discussed in the United States. Others feared that they would become the victims of doxing, defamation, and even violence as they watched what was happening around the United States. While there has long been censorship and repercussions for those who critique the policies of the Israeli government, the level of censorship and harassment since October has been unprecedented and students needed help navigating this charged landscape.

In the first few weeks of this war, my colleagues and I held multiple informal gatherings to create a space to be with each other and to be able to speak freely about the violence that was unfolding. We also held many events with speakers who reflected on the contexts for the war, a longer history of occupation, siege and displacement, and the United State’s involvement in funding the Israeli military and its occupation. While many universities were censoring such conversations, we held many such events, and Georgetown has remained committed to protecting the spaces of critique and discussion that are so central to a university’s mission.

Some of my students have faced tremendous loss, with scores of family members killed in the Israeli war on Gaza. Others, not directly impacted, were nonetheless grieving. Sometimes what we needed to do is to grieve together—to acknowledge that nothing we say can ameliorate the tremendous violence and loss of life. Grieving means not being afraid to be vulnerable— showing emotion and attending vigils where the names of too many dead are read aloud. It also means giving hugs, feeding people, being understanding and flexible.

Some students are struggling to make sense of long held beliefs about international laws and conventions, about Israel, or about Arab governments. Again as both a teacher and mentor, my goal has been to create opportunities for students to speak freely about their misgivings, about what they don’t know or are not sure of, in the classroom, in small gatherings, and in one on one meetings.

What has been perhaps most important for me as a faculty member is to support my students through solidarity. By going to their walkouts, vigils and the teach-ins they organize, I try to support those students who speak up despite all the attempts to scare them into silence. Also, by speaking up myself, I try to model a commitment to social justice that was cultivated in part through my education at an undergraduate Jesuit institution where I learned that we must labor against all forms of injustice. That to love others — to be men and women for others — demands that we act, that we do not remain silent.

*This article was first published by Conversations on Jesuit Higher Education on February 25, 2024.

Two CCAS instructors reflect on their experiences of teaching Palestine in this historic moment.

Last fall, my seminar on Palestinian Politics (ARST 4467) started off much as it had the previous three occasions I had taught the class since 2021. The course was designed to explore the history and development of the modern Palestinian national movement from its origins in the years before and after the 1948 Nakba, through the trials and tribulations of the Palestine Liberation Organization during the 1970s and 80s, the advent of the Oslo peace process and the creation of the Palestinian Authority in the 1990s, up to the present-day schism between Fatah and Hamas.

Barely a month into the semester—ironically just after discussing Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon—the attacks of October 7, 2023 and Israel’s subsequent assault on Gaza radically transformed both the region and the nature of our class. For several weeks after 10/7, I set aside time at the start of each class to talk through the ongoing events and what they meant. Unlike previous cohorts, a majority of the students enrolled in the class either hailed from or had family in various Arab countries, including two students with relatives inside Gaza. Moreover, given the unprecedented scale and brutality of both the 10/7 attack and the war on Gaza, I felt it was important to acknowledge and address the very real and profound trauma that my students, particularly the two from Gaza, (and I) were experiencing.

At the same time, the events taking place in Gaza and the region presented a unique learning/teaching opportunity. Questions about the ongoing Fateh-Hamas split, the future of Palestinian leadership (or lack thereof), the impact of regional dynamics on internal Palestinian decision-making, as well as the interplay between internal Palestinian politics and the US-sponsored peace process were no longer abstract concepts relegated to the past but tangible and highly fluid realities unfolding before our eyes.

Khaled Elgindy is an adjunct instructor at CCAS and a senior fellow and director of the Program on Palestine and Palestinian-Israeli Affairs at the Middle East Institute.

When I had first agreed to teach a class on Palestine at Georgetown it was months before the October 2023 outbreak of the war on Gaza that would rock the region and the world. “Arguing Palestine/Israel,” what I decided to name the course, would commence in the spring semester of the following year—by which time the war had grinded on for several months. I wanted to design a class that would approach the issue in a different way and decided to teach about the confrontation between the Palestinian people and Zionism over the past 130 years through the prism of public debate. Given current events and the heated debates around the war on Gaza, the class registration was full and had numerous students on the waitlist.

Students in my seminar grapple with primary sources over this history in the shape of arguments made from various perspectives. For a mid-term assignment, I challenge the students to “find an argument and make an argument.” They are tasked with finding a compelling argument through a primary source document that isn’t already included in our readings and then to make an argument themselves for why that source should be included in a future version of the syllabus. The exercise gets the students to familiarize themselves with the archives, dig through material they are unfamiliar with, think about how it relates to other material in the class, and then make a pitch for its inclusion. It also affords them a unique opportunity to express themselves and take some ownership over shaping the class. The quality of the papers they submitted, like the students themselves, has been very strong.

It has been a rewarding experience, for both myself and the bright and dedicated students in the class. Teaching a class like this, in this moment when there is so much argument over Palestine/Israel in the public discourse, allows the students to reflect on just how much has changed in the way this issue is debated and just how much hasn’t.

Dr. Yousef Munayyer is an adjunct assistant professor at CCAS and a senior fellow at the Arab Center Washington DC, where he heads the Palestine/Israel Program.

MAAS alum Michael Fischbach discusses his groundbreaking research on divisions within the 1960s Black Freedom Struggle in America over the Israel-Palestine conflict and how Black Power activists supported the Palestinian struggle for liberation—planting the seeds for transcontinental solidarity that continues today.

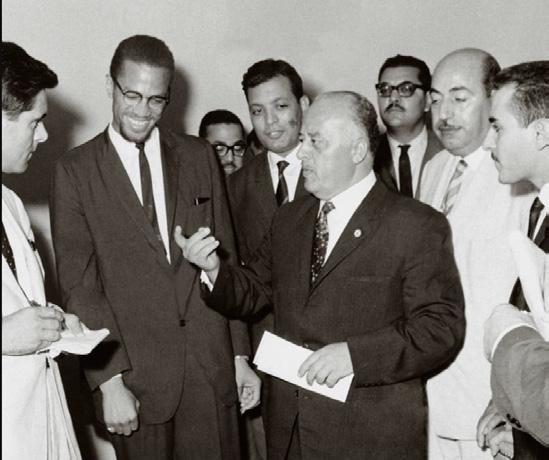

By Michael R. FischbachBack in 2010, I stumbled by chance across a reference to the fact that American Black Power advocate Malcolm X traveled from Cairo to Gaza for a two-day visit in September 1964. He had been in Cairo attending a conference of the Organization of African Unity and was driven to Gaza to meet with Palestinians and survey the situation facing the population there. He returned to Cairo, met with officials of the newly established Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and wrote a scathing attack on Zionism in an Englishlanguage Egyptian newspaper. I was stunned. After decades of deep familiarity with the history of Palestine/ Israel (including publishing three books on the losses sustained by Palestinian refugees and Jews who left the region following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War), as well as American history during the 1960s, I had never heard of this trip or indeed of any Black American connections to the Arab-Israeli conflict during the era of Civil Rights and Black Power. This surprising information about Malcolm X—along with revelations about other famous Americans of the 1960s traveling to the Middle East and meeting with Palestinians—prompted me to embark upon a years-long research project on the ways that American political activists reached beyond domestic concerns to focus on issues relating to Israel and the Palestinians during the Long 1960s (the period from the late 1950s to the early 1970s). My research led me to university and government archives in a number of U.S. states and foreign countries, as well as a deep dive into other primary and secondary sources. I also sought out classified U.S. government documents via the Freedom of Information Act and conducted many interviews in America and the Middle East. This lengthy project resulted in two books: Black Power and Palestine: Transnational Countries of Color and The Movement and the Middle East: How the Arab-Israeli Conflict Divided the American Left, published by Stanford University Press in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

In Black Power and Palestine, I document how both “wings” of the Black Freedom Struggle in the 1960s and 1970s—the Civil Rights wing and the Black Power wing—not only engaged with the Palestinians, Israel, and the Arab-Israeli conflict but embraced one side or the other in ways that not only reflected their ideologies but also their own sense of identity and political activism in America. Black Power advocates felt that they were waging a revolutionary struggle within the United States and thus saw the Palestinians as a kindred people of color also waging a revolutionary struggle for freedom alongside other Global South peoples during the age of decolonization. By contrast, Civil Rights leaders sought to reform the U.S., not revolutionize it. Supporting Israel, an American ally, along with moderate white allies who were helping them fight for Civil Rights “within the system,” was in keeping with this reformist vision.

My research also charts how, despite the demise of Black Power by the mid-1970s, support for the Palestinians did not recede but began extending into the Black mainstream. Among other things, this became clear when traditional Civil Rights figures like Joseph Lowery, Jesse Jackson, and Andrew Young

involved themselves in Arab-Israeli peacemaking by meeting with Yasir Arafat and others in the PLO in 1979. Other mainstream African American groups like the Congressional Black Caucus began speaking up for Palestinian human rights. Black support for the Palestinians had come to stay.

Many things struck me when carrying out this research. One was the sophisticated, deeply ideological, and strident nature of what many Black Power advocates said and wrote about Palestine/Israel. This was particularly true of the writings of various members of the Black Panther Party as well as activists like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture). Conversely, it amazed me to see how much certain traditional Civil Rights leaders like Roy Wilkins and, in particular, Bayard Rustin (the subject of the 2023 film Rustin, starring Academy Award nominee Colman Domingo), went to great lengths to embrace Israel, champion it, and consciously (and also stridently) distance themselves from Black Power attacks on the Jewish state.

When Black Power and Palestine came out in 2018, the historical events and ideas it explored proved to be highly relevant to what was happening in the world at the time: the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, the rise of intersectional American activism around various global issues, and the growing and concomitant prominence of public Black support for the Palestinians. Now, six years after publication, the book and the issues it documents continue to gain traction. Since the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7 and Israel’s resultant invasion of Gaza, I have received numerous interview requests from media in the U.S., Europe, and Asia asking me to comment, not on the situation in Gaza, but rather on why many Black Americans have been outspoken in their support for the Palestinians, both historically and today. Such requests not only highlight the ways in which African Americans continue to involve themselves in the Question of Palestine but also the fact that the mainstream media is paying attention to this phenomenon. This is particularly true as the Democratic Party tries to mobilize Black voters in advance of the November 2024 presidential elections amidst serious internal party divisions over President Biden’s indulgence of Israel’s war in Gaza. It is not just Black lives that matter, but Black voices and votes as well. ◆

Dr. Michael R. Fischbach is Professor of History at Randolph-Macon College. He graduated from the MAAS program in 1986 and was CCAS’ first-ever doctoral fellow at Georgetown’s Department of History, where he received his PhD in 1992.

An interview with CCAS Qatar Postdoctoral Fellow

Adey Almohsen on his research historicizing Palestinian thought in the years between the Nakba and the Six Day WarBy Vicki Valosik

Why did you choose to focus on the period between the 1948 Nakba and the 1967 War in your research?

Almohsen: Much of the recent historiography on modern Palestine focuses on either: 1) the late Ottoman and British mandatory eras and the years leading to the 1947-9 Nakba and the establishment of Israel; or 2) the period following the Arab defeat (Naksa) in the 1967 Six Day War, which saw the rise of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the intensification of the transnational Palestinian Revolution. The historiographical gap thus emerging spans the two decades separating Nakba from Naksa—or what Rashid Khalidi labeled as the “lost years.” My book project, Minds in Exile: An Intellectual History of Palestinians 1945–70, argues that much of our contemporary notions of Palestinian history and identity had their roots in this period, and that the intellectual debates of those years hold the key to understanding why certain visions of Palestinian identity have proven dominant.

While historians often work against ruptures in the line of time and instead point to contingencies and continuities between one historical moment and the next, the Nakba—at least with regard to Palestinian history—is a rather schismatic event that altered what it means to be Palestinian: socially, politically, psychologically, and culturally. It isn’t surprising, therefore, that Palestinian thought after the Nakba took on new meanings and proceeded from different priorities. Palestinian intellectuals were faced with the task of processing not just the Nakba’s human scale—e.g., the violent dispossession and depopulation of three-quarters of a million Palestinians—but, significantly, its multitudinous effects on their individual lives as stateless exiles and refugees

in a still-decolonizing Arab world. Yet, despite the odds stacked against them to critique, compose, and publish, Palestinians managed to do so in ways that redrew the Arab world’s intellectual map. In my forthcoming book, I historicize this messy process of Palestinian-Arab-global intellectual and literary exchange and investigate its tensions and antinomies between 1948 and 1967.

How did the literature produced during that era contribute to ideas about Palestinian identity, and how did Palestinians view the Nakba in intellectual terms?

Almohsen: I’ll answer by taking the example of Palestinian poet, critic, artist, and novelist Jabra Ibrahim Jabra (1919–94). In January 1948, Jabra and his family narrowly escaped death after the terrorist bombing of the Semiramis Hotel in West Jerusalem and fled the violence in Palestine with nothing more than a “battered suitcase,” containing “books, papers, a small box of paints and brushes, and half a dozen paintings on plywood” (Mejcher-Atassi, 2023).

By way of Damascus and Amman, Jabra eventually settled in Baghdad, where he’d stay until his death in 1994. Yet, in what could be seen as part of the dark irony of Palestinian being, his Baghdad house—along with the papers and paintings he’d produced there since the Nakba—would suffer a fate like that of his Jerusalem home and was destroyed in a car bomb in the waning days of the US invasion of Iraq.

Though Jabra died before seeing it multiply in scope and in cruelty, he compared the effects of the original

Nakba to the flood of Noah in its devastation. At the same time, his works reveal his conviction in the Nakba’s productive potential and as a harbinger of possibility, and Jabra was confident that from its ashes, Palestinians would emerge as renewed individuals. Indeed, on the tenth anniversary of the Nakba, Jabra argued in Shi’r magazine that Palestinians, “despite wounds and afflictions and despite being cut off from Palestine,” were steadily discovering and rediscovering themselves.

Jabra’s fascination with the individual-as-creator and his deep-seated belief in individuality could be viewed as the outcome of his intellectual leanings and political affinities. While this holds some weight, I argue that Jabra’s centering of individuality should be understood as the outcome of his experience of exile—a traumatic response to his banishment in the wake of the Nakba and to the discrimination he faced firsthand. Although he was an educated Palestinian, he could never be perceived as such, but was instead viewed as a wanting refugee possessing a dangerous intellect.

Despite the messiness of the Palestinian intellectual scene after the Nakba, much of Palestinian historiography continues to investigate Palestinians as a coherent unit. At a basic level, this historiographical unification is not surprising when one is trying to write into history a people long denied their beingness—and whose beingness is now under unrepentant, criminal bombardment. Yet exile and catastrophe do not homogenize their subjects, which is why my research seeks to write Palestinian subjects as individuals, first; and as members of an ambiguous, ever-sprawling nation-in-exile, second.

My main contention, thus, is to rethink the Nakba as not merely a unifying event within Palestinian history but an individuating one as well—a moment that brought into sharp relief for its first wave of victims (including Jabra and a score of other Palestinian figures I investigate in my book) the importance of individual freedom, self-making, self-renewal, self-constitution, and, by extension, self-determination. To rethink the Nakba in this way is not to ignore its lethal gravity or tragic upshots from 1948 to the present. Rather, this rethinking is about rejecting nationalist beginnings and understanding nation as a subjective, malleable entity.

What can your research reveal about the current Israeli war in Gaza?

Almohsen: Israel’s ongoing genocidal campaign against Gaza has dreadfully made my research topic—which looks at how Palestinians reacted in intellectual terms to the attempt to raze their existence in 1948—all the more poignant. Indeed, Israeli forces have so far killed dozens of Palestinian poets and academics and wrecked countless libraries, universities, and cultural sites in hopes of disabling any possibility of Palestinian intellectual reaction. Yet what never ceases to fascinate me— and what Israel continually fails to grasp—is the intellectual tenacity of the Palestinian people; a tenacity that is arguably more productive and more perennial than other displays of Palestinian tenacity. Yet, as we all witness the murder of Gaza’s Palestinians in mass, I hope, through my book, to write against the unrelenting attempts to massify Palestinians—either into a mass of hapless victims in need of saving or into a mass of savage terrorists in need of eradication. Against the flattening of Palestinian livelihoods and diversities, my book reckons with how Palestinian thinkers asserted their individuality and humanity in the wake of the historic Nakba, which is now dwarfed by Gaza’s 2023–2024 Nakba. ◆

Dr. Adey Almohsen is a cultural and intellectual historian of the Arab world from the eighteenth century to the present. He is the 2023-4 Qatar Postdoctoral Fellow at CCAS. In 2024-5, he’ll finish writing his book and publish it with the support of a fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies.

Throughout the past academic year, CCAS has responded to the war in Gaza by holding more than a dozen workshops and teach-ins to help educate the Georgetown community and general public on the history of the conflict, as well as a wide range of subtopics. We have hosted Palestinian scholars and professionals, partnered with departments, universities, and organizations across our campus and the country. Here are a few of the highlights.

CCAS has supported and contributed to the Gaza in Context Teach-In Series, which is part of the Palestine in Context Project, an initiative led by the Arab Studies Institute and supported by 21 partner organizations. The project convenes weekly conversations, teach-ins, and other activities that introduce our common university communities, educators, researchers, and students, as well as the general public, to a host of issues related to the ongoing war on Gaza. This project has hosted prominent speakers such as Diana Buttu, a PalestinianCanadian lawyer and analyst based in Haifa; Rana Barakat, an Associate Professor of history at Birzeit University in Palestine; and Rashid Khalidi, the Edward Said Professor of Modern Arab Studies at Columbia University.

CCAS partnered with the Alwaleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding (ACMCU) over the academic year to hold two event series focused on the conflict in Israel and Gaza and its global impact. In the fall, the series featured MAAS alum and political analyst Mouin Rabbani; Amira Hass, an Israeli journalist and author; and Peter Beinart, a political commentator and journalist. Each speaker discussed unfolding events as well as the impact on the broader Palestinian and Jewish diasporas. In the Spring, CCAS and ACMCU, along with the African Studies Department and Georgetown University Qatar, hosted the four-part Gaza Lecture Series. The first event featured Raz Segal of Stockton University and Shannon Fyfe from the Department of Philosophy at George Mason University, who discussed Israel’s assault on Gaza and the question of genocide in the conflict. For the second event, Ilana Feldman of George Washington University explored the multiple forms of humanitarian danger confronting Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. Tareq Baconi, president of the board of Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy

Network, was the speaker for the third event and provided a broader historical context for Hamas’ surprise attack on Israel on Oct. 7. The fourth and final event in the series featured Ussama Makdisi, Professor of History and Chancellor’s Chair at the University of California Berkeley, who drew attention to a long denial of Palestinian history and humanity, and the question of genocide.

In addition to these events focusing primarily on foreign policy and SWANA academia, CCAS fostered new partnerships and collaborations to diversify our programming on Palestine. In the fall, CCAS partnered with the Sports Industry Management Program at Georgetown to host the event “Not Allowed to Win: Exclusionary Policies Towards Palestinian Athletes” featuring Georgetown University Qatar professor Danyel Reiche. Reiche’s talk provided an overview of political issues around Palestinian sport and presented case studies on Palestinian athletes living in Lebanon and the discrimination they face due to their statelessness. In the spring, CCAS, along with Georgetown University Medical Students for Palestine and Doctors Against Genocide, hosted a panel of five healthcare work-

ers for the event “Voices from Palestine: Healthcare Advocacy in a Humanitarian Crisis.” The speakers shared their firsthand experiences working in Gaza and Palestine and the challenges of providing complex medical care with little resources during a humanitarian crisis. ◆

Coco Tait is the CCAS Events & Program Manager.

Reflections on the 2024 Kareema Al-Khoury Lecture, featuring Professor Noura Erakat, human rights attorney and leading voice on Palestinian rights.

By Leena KhanOn February 15, 2024, CCAS welcomed renowned legal scholar Professor Noura

Erakat to deliver the 2024 Kareema Al-Khoury lecture, “ The Limits and Potential of International Law in Achieving Accountability in Gaza.” The Kareema Al-Khoury Distinguished Lecture Series is an annual speaker event established in 1976 to bring eminent scholars of the Arab world to Georgetown. Professor Erakat is a human rights attorney, author, and activist who has emerged as a leading voice worldwide on Palestinian rights. Erakat, an Associate Professor at Rutgers University, joins the esteemed list of Kareema Al-Khoury guest lecturers that have included Edward Said, Laila Abu Lughod, Albert Hourani, and Kamal Boullata.

Since October, all eyes have been on Gaza witnessing as a horrific genocide has unfolded live on television and social media.

The International Court of Justice has issued a nearly unanimous ruling ordering Israel to prevent genocidal activities in Gaza.

Meanwhile, Congress was (at the time of writing this article) deliberating a defense-spending bill promising $14.1 billion of security assistance to Israel, which would supplement the annual $3.3 billion of unconditional military aid that the United States already provides. The world’s highest international court, our federal government, and citizens around the globe are all watching Gaza with rapt attention. Professor Erakat provided invaluable insight into how these visions map out by international law and what they mean for the future of Gaza.

has published groundbreaking work on human rights law and social justice, including the award-winning book Justice for Some: Law and The Question of Palestine She is a co-founding editor of Jadaliyya, an electronic magazine producing critical analysis on the Middle East through scholarly expertise and local knowledge. She has served as legal advocate for the Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Refugee and Residency Rights, and as national organizer of the US Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation. Professor Erakat has commented on major news networks about the Palestinian question, including CNN, BBC, and MSNBC. We were honored to hear her thoughts on international law and Gaza here at Georgetown.

Professor Erakat opened her discussion with a brief overview of a January 26, 2024 preliminary ruling by the International Court of Justice on South Africa’s case alleging that Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinian people in Gaza in direct violation of the Genocide Convention of 1948. The Court ordered provisional measures requiring that Israel prevent acts of genocide in Gaza. The response to this order has been mixed — South Africa and the Palestinian Authority declared it a victory, yet Israel and the United States celebrated the absence of an explicit call for a ceasefire as an alignment with their current policy. Professor Erakat clarified exactly what this decision means: that the ICJ demanded a ceasefire in everything but name.

Professor Erakat has exceptional expertise on international law and its applications to Palestine. Born in California to Palestinian immigrants, Erakat received her J.D. from U.C. Berkeley and L.L.M in National Security at Georgetown University. Since then, she

Erakat explained that the decision was groundbreaking because it recognized there was standing to bring the case to begin with. In the context of international law, “wars are legitimate, but genocide is never okay,” she said. The ICJ observed that Israel’s actions in Gaza do not amount to a self-defensive war, but to total destruction, citing genocidal statements made by Israeli political leaders and

the devastating level of civilian death in Gaza, among other things. In light of this evidence, the ICJ commanded that Israel prevent the mass killing of civilians. “This a strong decision,” Erakat asserted, “and we can use it as a tool to demand an immediate ceasefire.”

Erakat refuted the two defenses that Israel put forth against the genocide accusation. Genocide has a narrow legal definition; it amounts to targeting members of a non-political identity group with the intent to destroy. Israel contended it is killing Palestinians for their political status as Hamas, not because of who they are as Palestinians. But the evidence raises a different presumption. Israel has targeted all 35 hospitals in Gaza, it has assassinated dozens of journalists, it has killed an average of 117 Palestinians per day. Palestinians are guilty for the simple crime of existence, for their refusal to disappear. “Their national existence challenges Israel’s settler sovereignty,” Erakat explained, and so Israel kills Palestinians “because of who they are, regardless of what they do.”

Israel’s second defense was that it has been engaging in legitimate self defense since the Hamas attack on October 7th, and therefore all means employed in its campaign are legitimate. However, according to the Fourth Geneva Convention, a state has no right to military force against a territory that it occupies. Erakat explained that Israel has controlled Gaza’s land, sea, and air borders for the past 17 years, which effectively makes it an occupying power. Put simply, an occupier cannot defend itself against the occupied; it is in a naturally offensive position against them. Israel has attempted to blur its legal status as an occupier by naming Gaza a “hostile entity” rather than a sovereign people, yet international legal bodies like the ICC have decisively recognized Gaza as an occupied territory.

But despite the strength of the case against Israel, Erakat predicted that the ICJ trial will end without a guilty conviction. The law relies on precedent, and

precedent is simply unfavorable. For instance, after the Bosnian genocide, the ICJ ruled that only one massacre constituted genocide, and even then, that the Serbian government was not responsible for it. Moreover, the original genocide against the Palestinian people, the 1948 Nakba, has long been accepted in international law. When Israel declared its statehood in 1948, it denied that Arab Palestinians also had a right to statehood and ethnically cleansed them from the land. United Nations Resolution 242, passed nineteen years later, normalized Israel’s bloody seizure of the land. It refers to the Palestinians displaced by Israel merely as the “refugee problem,” eliding their long-overdue right to self-determination and their legitimacy as a people.

In the context of international law, “wars are legitimate, but genocide is never okay,” said Erakat.

Erakat’s overarching lesson was that there are serious limits to international law in achieving accountability in Gaza. Even in the unlikely scenario that the ICJ issues a guilty verdict, the Court doesn’t have the authority to enforce it. However, there is hope on the horizon. The ICJ may not be able to enforce its rulings, but, according to Erakat, we certainly can. Erakat explained that the power of international law rests in the people who choose to use it. She presented international law as a tool to shape imagination, legitimizing the efforts of individuals, organizations, and governments taking action against the genocide in Gaza. Erakat shared some examples, noting that following the preliminary ruling ordering Israel to prevent genocide, Dutch rights groups sued their government and stopped weapons shipments to Israel. Another example was a Japanese company that recently ties with Israeli defense businesses.

International law is an important tool to promote accountability for powerful world actors that otherwise commit atrocities with absolute impunity. But it is by no means our ultimate moral authority. Neither are our governments, nor our corporations, nor any of the institutional forces that have enabled this genocide. The ongoing atrocities in Gaza are an absolute failure of our current systems of justice, and the people have noticed. We are awake, and we are committed to enact change. “I believe in your rebellious generation,” Erakat said, and was met with a standing ovation.

A video of Professor Erakat’s talk is available on the CCAS YouTube Channel ◆

Leena Khan, a 2023 SFS graduate, majored in International Politics and earned an Undergraduate Arab Studies Certificate from CCAS.

“Farewell, my library! Farewell, the house of wisdom, the abode of philosophers, a house and witness for literature! How many sleepless nights I spent there, reading and writing, the night is silent and the people asleep…goodbye, my books! I know not what has become of you after we left: Were you looted? Burnt? Have you been ceremonially transferred to a private or public library? Did you end up on the shelves of grocery stores with your pages used to wrap onions?”

-Khalil Sakakini, a Palestinian educator and writer, expelled by Israel from his home in Qatamon, Jerusalem in 1948.

ASa PhD candidate researching the Palestinian Revolution during the 1960s and 1970s, my discussions with former revolutionaries, known as the fidayeen, are always marked by their enthusiastic recollections of the books that profoundly transformed their being, thoughts, and imaginations. These books have transported them to other anti-colonial struggles, solidifying their commitment to revolutionary ethos and the liberation of Palestine.

Take Suhayla Bahlwan, an avid reader whose cozy apartment in Amman was filled with old and rare books, periodicals, and novels. As a young woman, she used to return home from her work as a teacher and pour into the works of Socrates, Descartes, Kant, Sartre, deBeauvoir, Camus, Hegel, Marx, and Lenin. Then, after witnessing the devastation and the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians in 1967, Suhayla began voraciously reading Palestinian history. She says that hearing first-hand accounts from Palestinian refugees who arrived in Jordan transformed her life’s trajectory and prompted her to join the Palestinian revolution.

Khadijeh Habashneh, a clinical psychologist and a revolutionary, also underscored the pivotal role of reading in fueling her own commitment to revolutionary struggles. For Khadijeh, liberating the land was tied to liberating one’s mind and soul through the accumulation of knowledge. She loved theater, literature, and history and read everything from Arabic, Russian, and French poetry to political books on the Algerian, Vietnamese, and Cuban Revolutions. Besides her political engagement, Khadijeh authored a book highlighting Palestinian women’s contribution to the revolution,

produced two films in Lebanon, and helped establish and document the journey of the Palestinian Cinema Unit, which, in turn, played a major role in documenting the Palestinian revolution.

The experiences of Suhayla and Khadijeh echo a common narrative among the fidayeen I interviewed— that reading had been, for them, an emancipatory practice. Reading expanded their horizons and connected them with other revolutionaries, thinkers, and philosophers, while also arming them with historical facts and theories that informed their revolutionary work and strengthened their commitment to returning to Palestine.

Since its emergence in Palestine in the early twentieth century, the Zionist project has been acutely aware of the transformative power inherent to knowledge and the spaces that safeguard it, such as libraries, archives, and community centers—and has consistently marked these spaces as a threat. Consequently, the Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) have systematically targeted these spaces, either by bombing and destroying them, looting them, or by falsely depicting them as sites that foster “hate.” This cultural genocide has been well documented by scholars, including Daud Abdullah, whose work charts the intentional and systematic approach adopted by Zionists to erase and destroy Palestinian culture through the theft or outright destruction of books over the past century.

During the 1948 Nakba, Israeli forces looted 30,000 books and manuscripts from the homes of Palestinians from West Jerusalem alone, while the total number of books looted and stolen during that period is estimated at 70,000. They include the private collection of the

renowned Palestinian educationist Khalil Al Sakakini, whose lamentation over losing his library opens this article. Other forms of cultural production were looted as well, such as original photographs by Ali Zarour and Ibrahim Rissas, who were among the leading Palestinian photographers in Jerusalem in the early twentieth century. Their stolen collections were discovered later by a lecturer at Tel Aviv University in the Israeli archives.

These acts of destroying Palestinian culture and knowledge did not cease after the Nakba. In 1958, the Israeli authorities ordered the eradication of 27,000 Palestinian textbooks from the pre-1948 period, which were deemed by the state as either useless or threatening, and sold them to a paper plant to turn them to pulp. According to Israeli PhD student Gish Amit, this act was “a cultural massacre undertaken in a manner that was worse than European colonialism, which safeguarded the items it stole in libraries and museums.” Nearly twenty-five years later, during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, Israeli forces targeted the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) research center, as well as the Institute for Palestine Studies, a private organization in Beirut. The New York Times cited PLO research center director Dr. Sabry Jiryes, who said Israeli troops stole not only the entire library, which included 25,000 volumes in Arabic, English, and Hebrew, but also their printing press, microfilms, manuscripts, and other archives—smashing filing cabinets and furniture in the process and making off with telephones, heating equipment, and electric fans.

Given this history, the destruction of all universities and many libraries in the Gaza Strip since last October, though shocking in its unprecedented scale, should not be viewed as an aberration. Rather, it represents a continuation of Israel’s colonial policy aimed at obliterating Palestinian knowledge production—at not only erasing its past and present but hindering its future possibilities as well. According to a report by Librarians and Archivists with Palestine, at least 22 archives, museums, and libraries in Gaza were destroyed, damaged or looted by Israeli armed forces between October 2023 and January 2024.

The decimation of Gaza’s libraries began on October 9, 2023, when the IOF leveled the library of the Islamic University of Gaza. The following day, the Samir Mansour Bookshop and Library, which was demolished in 2021 and then rebuilt, was again bombed to the ground. Soon after, the Jawaharlal Nehru Library at Al-Azhar University was destroyed, along with the entire university. On November 25, the Diana Tamari Sabbagh Library in the Rashad al-Shawa Cultural Center was demolished by Israeli shelling, resulting in the loss of tens of thousands of books and the destruction of a building that had been providing refuge to thousands of displaced Palestinians. Two days later,

local sources reported that the Gaza Municipal Library caught fire, causing severe damage to the institution. On December 6, six additional scholarly institutions in Gaza City were reported destroyed: the Enaim Library, the Kana’an Educational Development Institute and its community library, the Lubbud Library, Al-Nahda Library, Al-Shorouq Al-Daem Library, and Al-Quds Open University Library. Another grave loss occurred on December 8 with the complete destruction of the 7th-century Omari Mosque, including its library, which housed one of the most significant collections of rare books in Palestine, some dating back to the 14th century. Fortunately, over 200 manuscripts from the

library’s holdings were digitized in 2022. Israel’s relentless targeting of Palestinian libraries and other sites of knowledge production continued into the new year. On January 18, a video circulated showing the IOF’s controlled demolition of Al-Israa University, including its library and National Museum, which contained over 3,000 archeological artifacts.

Despite this tragically long list, authors of the report note that Israel’s ongoing bombardment of Gaza, the targeting of journalists, communication blackouts, widespread displacement, as well as the maiming and killing of researchers, librarians, and archivists have made a full accounting of the destruction to knowledge production sites impossible, and that the list is necessarily incomplete. Such obliteration of our artifacts, documents, art, literature, poetry, rare books, memoirs,

and archives—what Palestinian scholar Karma Nabulsi referred to back in 2009 as “scholasticide”—not only stands as an irreparable loss, but also prompts a fundamental question: Why would an entity claiming to be “civilized and modern,” juxtaposing itself against the “barbaric and backwards” natives, commit such barbaric and egregious crimes? What is it about Palestinian knowledge production that poses such a threat?

The answer is that the destruction of Palestinian knowledge is a fundamental part of Zionism. From its inception, Zionism propagated a constructed narrative

deeming Palestine an empty land devoid of culture, heritage, and history. Palestinians were maliciously portrayed as uncultured, barbaric, and backwards. This racist, orientalist, and distorted perception laid the groundwork for a narrative that sought to institutionalize the erasure of Palestinian existence. Settler colonialism is built on the replacement of one people with another, and this process entails ethnic cleansing that is both bodily and epistemic. It not only aims to

kill and annihilate the Palestinian body across historic Palestine and beyond but simultaneously seeks to destroy its physical infrastructure, including its archeology, artifacts, museums, libraries, and archives. According to scholar Kevin Chamberlain “The destruction of a people’s cultural heritage amounts to the destruction of a people’s memory, its collective consciousness and identity. In other words it is ethnic cleansing by another name.” By targeting Palestinian cultural and educational institutions, Zionist settler colonization aims to erase the Palestinian past, present, and the future in order to continue cementing its existence over the ruins and history of the indigenous people.

But, despite the efforts of settler colonialists, people indigenous to occupied lands always resist, and Palestinians are no different—even with the death, loss, and dispossession they have endured for a century. Academic researcher, and PhD candidate Hamzeh Abu Toha, whose house in Beit Lahia, north of the Gaza Strip, was recently bombed by the IOF, wakes up every day amidst the rubble and searches for remnants of his destroyed personal library. Abu Toha, now 27 years old, has spent much of his life amassing precious books from different countries in the region, a challenging process given Israel’s siege on Gaza. Comprised of over 18,000 books spanning history, literature, grammar, morphology, religion, and other subjects, Abu Toha’s library was not just about the physical books, he says, but about “knowledge, history, memories, dedications by authors, and a story of living throughout my life.” Abu Toha ended his interview by pledging to remain on his land, to rebuild his home and library in Gaza, and to open the library to the public. Although the war took “everything from us,” said Abu Toha, “it did not take Gaza from us…Gaza taught us to persevere, sumud.” This determination to remain, to piece together and rebuild the libraries and archives of Palestine’s history for the future embodies the Palestinian love for their land, their commitment to protect and preserve their culture, history, and knowledge, and their insistence to live in spite of Zionist efforts to eradicate Palestinian life. ◆

Samar Saeed, a 2019 graduate of the MAAS program, is currently a PhD candidate in History at Georgetown University.

The first documentary on Gaza, co-produced by CCAS Professor Joan Mandell forty years ago, provides an historical record of daily life under occupation.

By Shifaa Alsairafi

Gathering for Alarba’een, a day of remembrance when mourners come together on the 40th day after the death of a loved one or prominent figure, is a common practice in much of the Arab world. The 40th anniversary of the groundbreaking film Gaza Ghetto: Portrait of a Palestinian Family, 1948-84, which was co-directed by CCAS Professor Joan Mandell and was the first documentary produced about Gaza, was accompanied by a similarly solemn tone—not only because the neighborhoods depicted in the film have been destroyed since the documentary was released in 1984 but also because the situation in Gaza has grown exponentially worse in recent decades.

Gaza Ghetto is set in Jabalia, which—along with the entire Gaza Strip—came under Israeli occupation following the 1967 war, and by the 1980s had become home to the largest refugee camp in the occupied Palestinian territories. Mandell and her co-directors chose Jabalia as the primary site for the documentary not only because of its size and historical importance, but also because of her familiarity with many intellectuals and artists living there who could narrate their story. “Jabalia had a vibrant life of arts and activism, and many people who wanted to share it,” recalls Mandell. Although the film includes interviews with many Jabalia residents, its producers decided to center the story around an individual family so that they could document daily life under occupation. They ultimately selected the family of Abu el-Adel because of the family’s openness and ability to articulate their own experiences as part of a collective story. Indeed, the personal stories narrated by Abu el-Adel, his daughter Itidhal and son-in-law Mustafa, were representative of the tragedies facing thousands of Palestinians and the mass dispossession forced upon them by the Israeli state. Mandell recalls that Itidhal and her daughter Ra’ida—both strong female figures—were a major reason she was drawn to portray this family. The film opens with Itidhal confronting the Israeli settlers who live in a town that displaced her father’s village and includes scenes of Itidhal caring for her six children while husband Mustafa works the nightshift, as well as sharing the story of how her mother died in childbirth

when Israeli soldiers would not allow an ambulance to reach her during a camp lockdown.

The film chronicles life in Jabalia beyond the Abu el-Adel family, depicting friends and neighbors coming together to share their stories and discuss the hardships of the occupation. Palestinian voices are also juxtaposed throughout the film with those of Israeli soldiers on foot patrol and government officials directly responsible for the administration of the military occupation. In their interviews, those with boots on the ground express dismissal of Palestinian lives and show their lack of concern for the gravity of the dispossession faced by the people whose lives they are policing. Through this dichotomy between the Abu el-Adel family’s self-awareness and strength, and the dismissive attitude of Israeli soldiers and settlers, viewers get a glimpse into the dichotomous existence of the colonizer and the colonized.

Although Mandell had experience as a journalist, she didn’t set out to be a filmmaker. During college, she worked as a photographer and editor-in-chief of her university’s daily newspaper, and later as an editor at MERIP Middle East Reports. In the early 1980s, she accepted a job as a journalist for Al-Fajr, an English-language weekly newspaper based in East Jerusalem that was trying to expose Palestinian life under occupation to the West—particularly to the United States. Many articles she wrote, however, never saw the light of day, as the newspaper was censored by the Israeli government. Mandell began thinking about other ways to share the stories and interviews she was collecting, including potentially writing a book, when an unexpected opportunity came along—in the form of Swedish cinematographer and director PeA Holmquist. Holmquist had secured funds from Swedish arts and

government sources to produce a feature film about Gaza, but as a newcomer to the area, he needed the help of someone with on-the-ground experience and connections. Mandell had both, along with Arabic language skills and the carefully built trust of local communities. She says she found Holmquist to be a “determined and

of whom Mandell has stayed in close contact with over the years—as well as new generations of Palestinians in Gaza, make the film difficult to revisit, she says. “As a filmmaker and a friend [of the families depicted in the film], I carry photographs in my brain of the places and the people. I can see the buildings and the colors of the

dedicated chronicler, with a penchant for representing stories of disenfranchised people with utmost respect,” and agreed to co-direct the film, with the hopes that it would be an effective way to carry Palestinian voices from Gaza to the West.

For Mandell, who now teaches oral history and documentary filmmaking at CCAS, producing Gaza Ghetto was not just about gathering facts and presenting them on screen—it was also about combining those facts with narrative. Even forty years ago, she says, it was evident that Palestinians were not allowed to have a narrative, let alone share it with the world. At the same time, narrative—or the human element—is what galvanizes audiences and brings about action. “The film is just one piece of the puzzle,” explained Mandell. “It is the audience that sees it and the characters depicted within it that complete the puzzle.” Mandell felt it was critical that the film depict a rich spectrum of life in Gaza—not only the harsh realities of occupation but also the resilience of those living under it—and show that Jabalia was “a place where people celebrate first love, children play and go to school, and inspiration and poetry are alive.”

Gaza Ghetto poignantly demonstrates the rootedness of Palestinians to their lands, but this is sadly an image that Israel would like to erase from both distant and recent memory. In the forty years since Gaza Ghetto was produced, the film has become not only an historical archive of what once was, but also a study of the conditions that have led to the present moment. The continued realities faced by those in the documentary—many

Left to right: Itidhal combs her daughter Shurouk’s hair; her children Samar, Abdullah and Reham listen as she discusses the curfew; Itidhal confronts settlers at Kibbutz Erez.

homes where I spent so much time, and to know that Israel destroyed so much of it is heartbreaking.”

Today, with the vitality of the internet, there is more information available about life under occupation in Gaza, and Palestinians have become their own international journalists, photographers, and filmmakers as they share the atrocities Israel continues to commit against them. Even so, Palestinian voices often remain silenced, even in the West, which has long held sacred the value of free speech, as Israel and its supporters shut down any voices of dissent. For this reason, it is all the more important to get films like Gaza Ghetto out of the archives—as CCAS did in January when it hosted a screening of the film followed by a discussion with Mandell. As an historic document that has recorded and preserved the personal narratives of Palestinians, as well as the atrocities committed against them, Gaza Ghetto has become both an artifact and a tool of resistance— one that helps us understand both the precarity and persistence of the Palestinian situation in Gaza and its persistence in Palestinian life. ◆

Shifaa Alsairafi, originally from Bahrain, is a second-year student in the MAAS program.

The events of October 7, 2023 in Palestine and Israel immediately increased the demand for Education Outreach teaching materials and presentations, as many teachers lacked information they could trust that provides historical background for contemporary events. In addition, schools and school systems requested help dealing with the effects of the conflict, namely the high emotions and conflicting opinions it engendered. Through my capacity as director of the education outreach programs at CCAS and the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, I worked with school leaders to devise presentations to help them deal with accusations of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia among students, as well as incidents of bias that occurred in schools, on social media, and among “the adults”— family members, teachers and community leaders. We were particularly well prepared to address these needs because of CCAS’ teaching resources and because of the Bridge Initiative at ACMCU, which, for several years, has been researching and tracking the occurrence of Islamophobia at national and global levels.

nineteenth century period of imperialism and colonization of Muslim regions in Asia and Africa, and the struggles for independence in Eastern Europe. The presentations include stereotyped images of Muslims that have appeared in movies and animated films throughout the decades, including Bugs Bunny’s encounter with a swarthy, big-nosed, scimitar-bearing figure—an image multiplied and expanded on in the notoriously stereotyped images of Arabs in Disney’s Aladdin. Images from the collections of Brandeis University and the Philadelphia Holocaust Museum also demonstrate that anti-Semitic propaganda is cut from the same cloth as Islamophobia and that both forms of xenophobia have propagated remarkably similar denigrating tropes, including stereotypes of physiognomy, metaphors comparing these groups to vermin or swarms of insects, and figures striding the globe to hint at widespread conspiracies, the growing reach and un-assimilability of Muslims and Jews.

At the same time, these presentations have pointed out the shared linguistic roots of Hebrew and Arabic, that Arabs are also a Semitic people, and that the people who have for millennia populated the Levant, or the Holy Land, have been part of the Abrahamic faith traditions and shared cultural movements. Moreover, Christians, Jews, and Muslims have co-existed peacefully in the Middle East and North African region and beyond since the rise of Islam. It has not been ancient hatreds, but colonialism and nationalisms that have interrupted the legal and cultural structures of these societies—in particular since the post-WWII period.

The presentations we developed discussed the centuries-long existence of Islamophobia, which is defined by the Bridge Initiative as “an extreme fear of and hostility toward Islam and Muslims which often leads to hate speech, hate crimes, as well as social and political discrimination.” Islamophobia dates back to medieval Europe but saw an upsurge during the

Summer Teacher Institute 2024: Teaching the History of Palestine and Israel in the K-12 Curriculum

July 29-August 2

This year’s Summer Teacher Institute at CCAS, co-sponsored by ACMCU, will provide information on the deep history of Israel-Palestine conflict, as well as teaching resources that meet both academic content and skills standards, including the ability to understand multiple perspectives through analysis of documentary sources.

The second focus of the presentations has been to educate students, parents, and administrators on the impact of bullying and prejudice and to provide tools for combating both. We also address ways to become “up-standers” who speak up against bullying and support its victims in positive, non-aggressive ways. In addition to highlighting resources from the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Education, and advocacy organizations such as the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding and the David’s Legacy organization, the presentations feature scenarios taken from students’ actual experiences and include discussions and advice for dealing with similar, real-life situations. These presentations have been given for large groups through the Montgomery County Public School system, with more than 100 teachers and 500 students at some individual sessions, as well as at other regional schools and at the Smithsonian Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

It is hoped that inclusion of various forms of prejudice will send a message of unity and empowerment in these learning communities rather than the focus on which side is right or wrong on the very issue that has created the renewed need for such messages. ◆

Dr. Susan Douglass is the Director of Education Outreach at CCAS.

In my book, Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced (Stanford University Press, 2011), I explored how histories are constructed and told, and the power to narrate the past. I was keen to understand what sort of narratives became “history,” and in particular how known historical events are fleshed out, supplemented, clarified or undermined by individual and collective memories and experiences. Today we are witnessing the retelling and reassertion of the past, on the global stage, as Israel executes its genocidal violence on Gaza.

Palestinians are at a disadvantage in the struggle to create official historical narratives. Because Palestinians live in a number of different countries and have no state

This repeated destruction of the institutions that Palestinians build to tell their history, transmit their culture, educate their children, and create their society is part of the attempt to eliminate and silence them. But Palestinians persevere.

of their own, they have had little ability to hold on to records and documents, build archives, and maintain other material and structural sources that are used in the writing of history. They are without a state, do not sit as a state in the United Nations General Assembly, and until the post-1993 Oslo Accord creation of the Palestinian Authority, did not create their own school textbooks. Even when they have created archives, libraries, and institutions, they are subject to Israeli targeting and destruction. For example, in the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the Palestine Research Center was looted and all of the material was taken to Israel—documents, photographs, films—and later returned to the PLO in Algeria to an unknown fate. Among the targets of destruction in the 2002 Israeli re-invasion of the West Bank was the Ministry of Culture. In Gaza today, the term “scholasticide” is used to describe the destruction of every institution of higher education (twelve) and 80% of schools. In addition, the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) documented the damage to or destruction of “more than 200 of the 325 registered sites in Gaza.” This repeated destruction of the institutions that

Palestinians build to tell their history, transmit their culture, educate their children, and create their society is part of the attempt to eliminate and silence them. But Palestinians persevere. They write their histories in other ways. Collecting oral histories and the stories of the elders was and remains a hugely important part of Palestinian life. During my research, I spent a lot of time talking to Palestinians about where they learn their histories. In the early 2000s in refugee camps and urban neighborhoods in Damascus, Beirut, Tripoli, Ramallah, and Amman, Palestinians told me over and over that it was their grandparents, aunts, uncles and other family members who they turned to in order to learn history. My conclusion was that for many Palestinians, the past is held alive in the present through the people in their lives, their memories, and their stories.

These sources have provided rich material for different ways of writing history. What has emerged from research institutes, universities, communal organizations, and individuals’ collections and memories, are projects to tell those stories and histories from the perspectives of the people who lived. These projects include autobiographies, village memorial books, and oral history collections that exist on a popular level as expressions of individual, local, and communal understandings of the past. And more as people collect documents and make films, find old family photographs and document heritage practices, they have established museums, websites, and YouTube channels to preserve these histories.

Another part of the challenge Palestinians face in

telling their histories is managing the framing or meaning of those histories. Take, for example, an event—a massacre—that happened in 1948. On April 9 of that year, more than a month before the creation of the state of Israel, at least 107 Palestinians in the small village of Deir Yassin were killed in an attack on the village by the Zionist Irgun and Stern Gang militias. The massacre was communicated with horror and fear on the radio (in Arabic), in newspapers, and from person to person. For Palestinians at the time, the killings served to frighten them as they imagined what would happen if the Zionist militias came to their own towns or villages. For many years, it formed a narrative node around which story of the Palestinian Nakba of 1948 and the creation of the Israeli state was told. In the 1980s, Birzeit University, a Palestinian university in the West Bank, wrote about Deir Yassin in their village book oral history series, documenting life before the massacre along with the names of those killed and displacement of the villagers.