TWENTY YEARS LATER

CCASNewsmagazine Center for Contemporary Arab Studies Georgetown University ccas.georgetown.edu Summer 2023

THE IRAQ WAR

A NOTE FROM THE OUTGOING DIRECTOR Joseph Sassoon

As my time as CCAS Director wound to a close this summer, I have had time to reflect on all that we, as a community, achieved in the past three years. I assumed the directorship in July 2020. The world was in the throes of the pandemic, and all the fear and uncertainty it brought made it a challenging and unusual time to take on the leadership of an academic department. The virtual learning environment was new to nearly all of us. But the faculty, staff, and students adapted amazingly, demonstrating unprecedented creativity and flexibility, and a shared determination to maintain not only the high educational standards, but also the sense of community, for which CCAS is known. Faculty underwent professional pedagogical training for the pivot to online learning, staff stepped up and took on a wide range of new roles and tasks, and students too, rose to the challenge, demonstrating incredible resilience. Looking back, I believe we not only survived, but thrived as a result of these efforts.

Over the past three years, CCAS has continued to matriculate diverse and talented cohorts of graduate students from all over the globe. We have increased our scholarship endowments, hosted research and post-doctoral fellows, and added a new tenure-line professor to our faculty. Thanks to the outstanding work of our staff, CCAS and Georgetown were awarded a Department of Education Title VI grant for over $2 million to support our programming as a National Resource Center on the Middle East. The work of CCAS is more impactful than ever, thanks to the transition of our public events and education outreach to virtual and hybrid platforms, which have enabled us to greatly expand the reach and diversity of our audiences. Following the murder of George Floyd, CCAS students, faculty, and staff formed a Racial Justice Task Force and undertook meaningful steps to deepen our commitment to inclusivity and to elevating diverse voices through our curriculum, events, and programming. Thanks to the dedication and tireless efforts of our faculty and staff, and to the energy and intellectual engagement of our students, the above list is only a small accounting of what the CCAS community has achieved despite the challenges of recent years. It has been my honor to serve as director for the past three years, and I’d like to congratulate Dr. Fida Adely as she takes the reins as the new CCAS Director.

CCASNewsmagazine

The CCAS Newsmagazine is published twice a year by the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, a component of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Core Faculty

Fida J. Adely, Associate Professor and Clovis and Hala Salaam Maksoud Chair in Arab Studies; Director, Center for Contemporary Arab Studies

Killian Clarke, Assistant Professor

Marwa Daoudy, Associate Professor and Seif Ghobash Chair in Arab Studies

Rochelle A. Davis, Associate Professor and Sultanate of Oman Chair; Director, Graduate Studies

Joseph Sassoon, Professor and Sheikh Sabah Al Salem Al Sabah Chair

Affiliated Faculty

CORE AFFILIATES

Mohammad AlAhmad, Assistant Teaching Professor

Belkacem Baccouche, Assistant Teaching Professor

Noureddine Jebnoun, Adjunct Associate Professor

AFFILIATES FROM OTHER DEPARTMENTS

Osama W. Abi-Mershed, Associate Professor, Department of History

Mustafa Aksakal, Associate Professor, Department of History

Jonathan Brown, Professor, ACMCU and Department of Arabic & Islamic Studies

Elliott Colla, Associate Professor; Chair, Department of Arabic & Islamic Studies

Felicitas M. M. Opwis, Associate Professor, Arabic & Islamic Studies

Welcome to Incoming CCAS Director Dr. Fida Adely

Associate Professor Fida Adely stepped into her role as the new CCAS Director in July. Dr. Adely joined the Center as a core faculty member in 2007 and holds the Clovis and Hala Salaam Maksoud Chair in Arab Studies. As an anthropologist, Dr. Adely focuses her research and teaching on education, labor, development, and gender in the Arab world. She previously served as the Academic Director of the Master of Arts in Arab Studies program.

“I look forward to taking over as CCAS director, and continuing the important work of my predecessors,” says Adely. “As we approach CCAS’ 50th anniversary, I

hope to reflect on our significant history and strengthen our academic program and public engagement moving forward. Our students and alumni are at the heart of everything we do, and I will work to further engage our alumni in the life of CCAS.”

On behalf of the CCAS community, we’d like to extend both a warm welcome to Prof. Adely and our sincere thanks to Professor Sassoon for his leadership, guidance, and support over the past three years. His many contributions have strengthened the Center and will continue to be felt long into the future. Please check back in the next issue for more on Prof. Adely and her vision as director.

Suzanne Stetkevych, Sultan Qaboos bin Said Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies

EMERITI FACULTY

Ibrahim Oweiss, Professor Emeritus, SFS

Judith Tucker, Professor Emerita, CCAS and the Department of History

Staff

Dana Al Dairani

Senior Director of Programs

Susan Douglass

K-14 Education Outreach Director

Kelli Harris

Assistant Director of Academic Programs

Coco Tait

Events and Program Manager

Vicki Valosik

Editorial Director

CCAS Newsmagazine

Editor-in-Chief Vicki Valosik

Design Adriana Cordero

An online version of this newsletter is available at http://ccas.georgetown.edu

2 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University

ABOUT THE ISSUE

The Iraq War 20 Years Later

In this issue, we delve into work being done by the CCAS community to better understand the lasting impacts of the American war in Iraq. CCAS professors Rochelle Davis and Joseph Sassoon discuss—respectively—the U.S. military’s conceptions of Iraqi culture and the regional growth of authoritarianism, post-invasion. Visiting Scholar Salma AlShami shares findings from a multi-year study on displacement in Iraq. Reflections on lessons learned are offered by alums Paul McKinney and Motasem Abuzaid. From our students, Besan Jaber details a project to honor slain Iraqi academics, while Shano Mohammed shares a powerful essay and a poem about the deeply personal impacts of war. We hope this issue serves to add to the ongoing reflections about the devastating legacy of the war and the deep injustices perpetrated against the Iraqi people.

Vicki Valosik, Editor

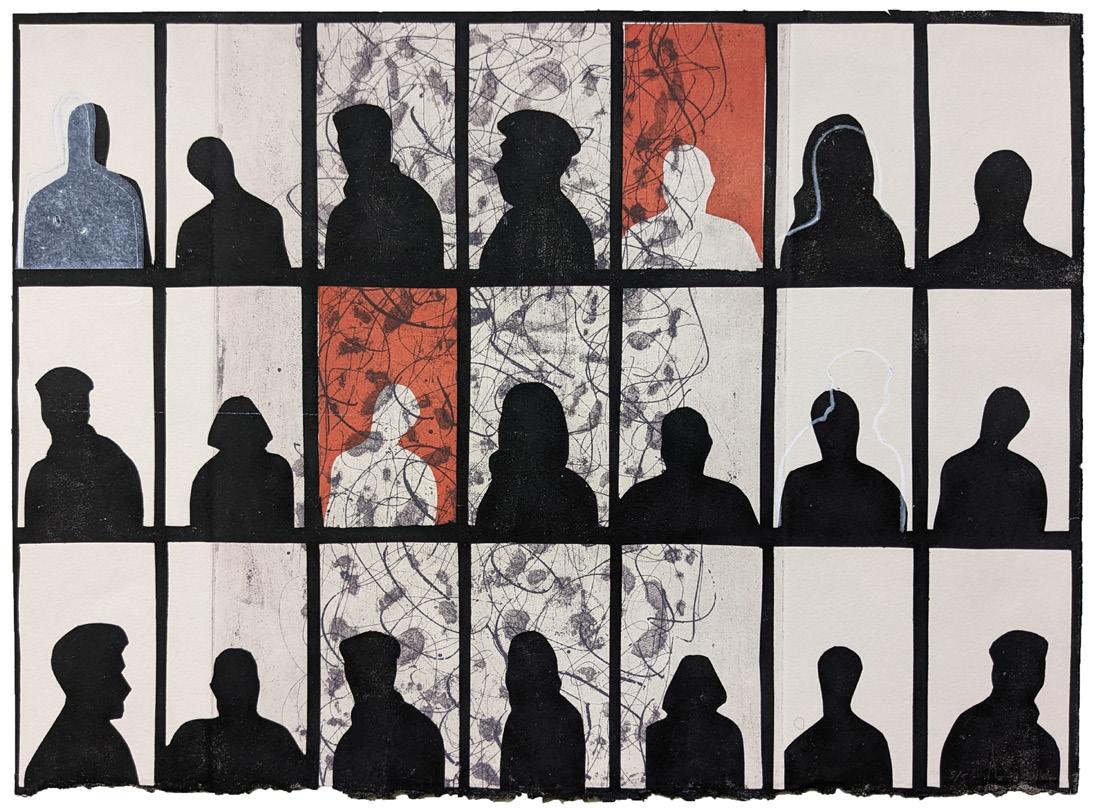

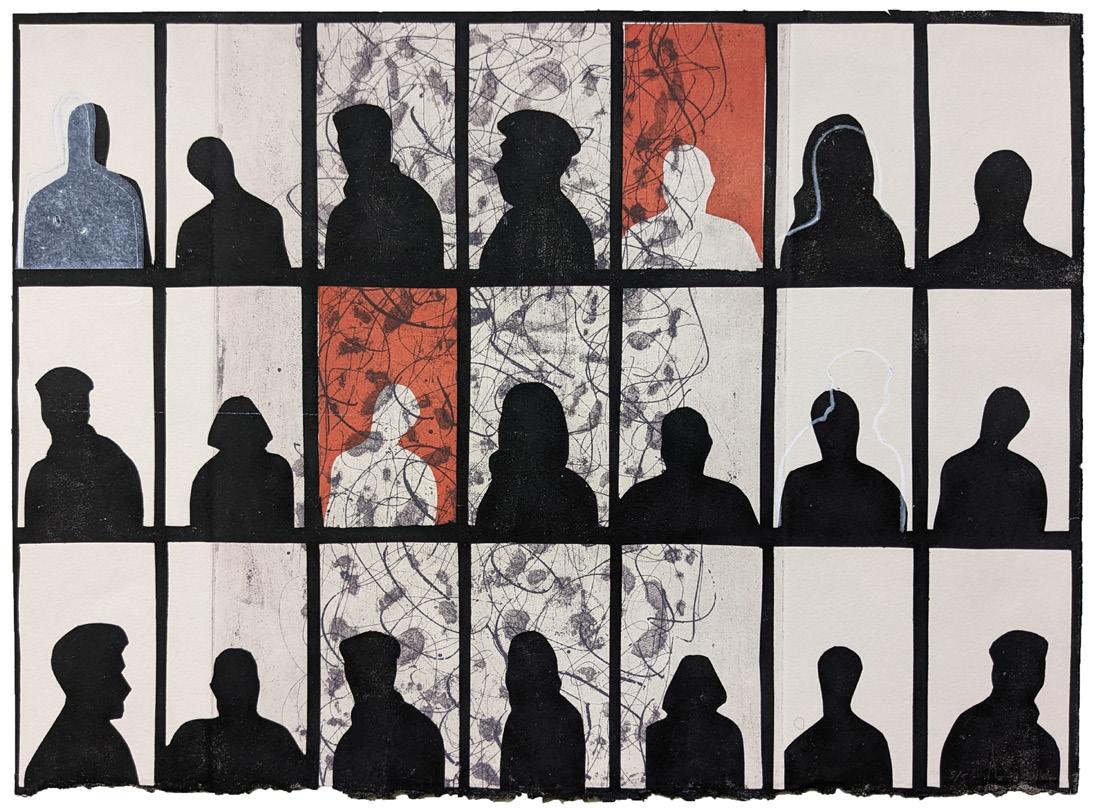

ON THE COVER Reach

Linocut and Chine Collé by Sarah Anne Decossard

ABOUT THE ART

The art featured on the cover and throughout the issue are part of "Absence and Presence," a print initiative of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here project. The project was founded by Beau Beausoleil in response to the 2007 car bombing of Baghdad’s historic al-Mutanabbi Street, the heart of the city’s intellectual community and home to numerous booksellers. The project, which has been archived by Columbia University, engages artists and writers from around the globe to create works that serve as witness to the bombing and express solidarity with the Iraqi people and other arts communities in the MENA region. Beausoleil has said that wherever someone sits down and begins to write towards the truth, or picks up a book to read, it is there that al-Mutanabbi Street starts. Contributing artists featured in this issue are Sarah Anne Decossard (cover), Bev Samler (pg. 6), Wilson Hill (pg. 10), Jennifer Vickers (pg.11), Anne Moreno (pg. 12), Iram Wani (pg. 13), and Art Hazelwood (pg. 19). Additionally, you can learn more about a new project of Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here called "Shadow & Light" on page 8. For more information on these projects, Beau Beausoleil can be reached at overlandbooks@earthlink.net

3

FEATURE ARTICLES New Research 6 What Iraq Tells Us About Displacement Student Feature 8 Honoring the Memory of Iraqi Academics 19 Astute War, a poem Faculty Feature 10 The American Invasion and Authoritarianism Alumni Feature 12 The Lessons We Choose to Draw Faculty Spotlight 14 No Good Way to Occupy a Country SPECIAL STORIES 16 Iraq 20 Years On: Prospects of Epistemic Reconstruction Dispatches 20 Life Beyond the Borders REGULAR FEATURES 4 Faculty News 5 Center News 18 Public Events

In This Issue

A few highlights of the recent activities of CCAS faculty

Book Chapters

“Water and Climate Challenges in the Middle East: A Human Security Perspective” chapter in Enhancing Water Security in the Middle East (MENA Water Security Task Force, Al-Sharq Strategic Research and Colorado School of Mines, 2023) - Marwa Daoudy

“Stranded in Decolonization: The Attritional Temporality of Sahrawi Activism in Moroccan-Occupied Western Sahara” chapter in In the Meantime: Toward an Anthropology of the Possible (Berghahn Books, 2023) - Mark Drury, CCAS Qatar Post-Doctoral Fellow

“ Tunisia: A Reframed Security-Centered Approach” chapter in Security Assistance in the Middle East: Challenges ... and the Need for Change (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2023) - Nouredinne Jebnoun

“Beyond Oslo: Reimagining Israeli-Palestinian Futures” chapter in The One State Reality: What Is Israel/Palestine? (Cornell University Press, 2023) - Khaled Elgindy

Journal Articles

“Revolutionary Violence and Counterrevolution” (American Political Science Review, December 2022) - Killian Clarke

“Ambivalent allies: How inconsistent foreign support dooms new democracies” (Journal of Peace Research, February 2023) - Killian Clarke

“Naming the City: Saharan Urbanization and Disaggregated Sovereignty ” (L’Ouest Saharien, February 2023) - Mark Drury

“ Why Security Cooperation With Israel Is a Lose-Lose for Abbas” (Foreign Policy, February 2023) - Khaled Elgindy

“From Victims to Dissidents: Legacies of Violence and Popular Mobilization in Iraq, 2003–2018” (American Political Science Review, April 2023) – Killian Clarke

Reports & Policy Research

“ Women, Peace and Security: Gulf Perspectives on Integration, Inclusion and Integrity ” (Gulf International Forum, November 2022) - Dania Thafer

“China-Gulf Ties: Tougher Acts to Follow Successful Show ” (The Arab Gulf States Institute, January 2023) - Robert Mogielnicki

“Gulf governments enjoy fiscal flexibility; must spend wisely over coming years” (Al-Monitor, January 2023) - Robert Mogielnicki

“Surge in West Bank violence further undercuts Abbas’s precarious leadership” (Middle East Institute, March 2023) - Khaled Elgindy

“Omani and Saudi Economic Zones Create Avenues for Cooperation” (The Arab Gulf States Institute, March 2023)Robert Mogielnicki

“Saudi Arabia’s New Murabba project to lure global investors, but at what cost?” (Al-Monitor, March 2023) - Robert Mogielnicki

“GCC Performing Strongly but Economic Opportunities Vary throughout the Region” (Henley & Partners, 2023) - Robert Mogielnicki

“DeSantis’ ‘war on woke’ looks a lot like attempts by other countries to deny and rewrite history” (The Conversation, July 2023)Rochelle Davis

Podcasts & Interviews

“No happily ever after: how Succession will end – by the experts” – Interview with Prof. Joseph Sassoon by London’s The Telegraph (March 2023)

“Exhibition Spotlight: Shadow & Light” – Prof. Rochelle Davis spoke about her involvement and that of and that of several MAAS students in an exhibit at the University of Iowa Pentacrest Museums examining themes of academic freedom (see page 8 for details)

“Knowledge Production on Iraq: Joseph Sassoon’s Intellectual Journey ” – Jadaliyya (April, 2023)

“Killian Clarke: Egypt’s Counterrevolution and the Return to Tyranny” – on Babel, the podcast of the Center for Strategic & International Studies (May 2023)

“The Sassoons: The Great Global Merchants and the Making of an Empire” – American Historical Association talk with Prof. Joseph Sassoon (May 2023)

Scholar Spotlight: Prof. Marwa Daoudy was the first to be featured in a new Scholar Spotlight series by the Environmental Studies Section at the International Studies Association 2023 convention

4 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University FACULTY NEWS

Fa culty Ne ws ﺲﯾرﺪﺘﻟا ﺔﺌﯿھ رﺎﺒﺧأ Sta ff Upda te s ﻦﯿﻔظﻮﻤﻟا رﺎﺒﺧأﺮﺧآ B o a rd Me mb e r Pro ile يرﺎﺸﺘﺳﻷا D ispa tche s تﺎﯿﻗﺮﺑ Pub lic Eve nts ﺔﻣﺎﻌﻟا تﺎﺒﺳﺎﻨﻤﻟا Educa tio n Outre a ch يﻮﺑﺮﺘﻟا ﻒﯿﻘﺜﺘﻟا In the He a dline s ﻦﯾوﺎﻨﻌﻟا ﻲﻓ Ma b ro uk! كوﺮﺒﻣ

MAAS News (Student News)

In Memoriam

Visiting Scholar

Mabrouk to the MAAS Class of 2023!

In May, we celebrated the graduation of 35 students from the Master of Arts in Arab Studies program. All of us at CCAS extend our congratulations to the graduates. We look forward to seeing what you all will achieve!

Thank you to our summer interns!

The CCAS community was deeply saddened to learn of the recent passing of Dr. Halim Barakat, a renowned Arab sociologist and novelist, and a professor at CCAS for 27 years. Dr. Barakat, born to a Syrian family and raised in Beirut, received both his undergraduate and master’s degrees from the American University of Beirut. His doctoral studies in social psychology took him to the University of Michigan, where he earned his PhD in 1966. Dr. Barakat joined the CCAS faculty in 1976. The Center had been founded at Georgetown only a year earlier, and Dr. Barakat pioneered numerous sociology courses and became instrumental in shaping the identity, activities, and curriculum of CCAS during its formative years.

CCAS Senior Director of Programs Honored for Staff Excellence

CCAS is pleased to congratulate our Senior Director of Programs Dana Al Dairani on receiving the 2023 School of Foreign Service Staff Excellence Award recognizing her outstanding work and many contributions to the Center and the School! The award honors SFS staff members who go above and beyond the duties of their positions and whose work has a lasting impact on the school. Dana, who joined CCAS in 2018, received the SFS Staff Excellence Award for her leadership and innovation at CCAS, as well as her role in shepherding the school through a major and successful Department of Education grant application. “Dana is an incredible worker who combines initiative, hard work, and a long-term vision of what the center does or needs to do,” said outgoing CCAS Director Joseph Sassoon. “This recognition is absolutely well deserved.”

Board Member Profile

Dispatches تايقرب

Each summer, CCAS partners with the National Council on US-Arab Relations and Bethlehem University to bring undergraduate student interns to campus to work with CCAS faculty and staff. This summer, CCAS had the privilege of hosting Suhair Mohammad Ali and Leen Altamimi (Bethlehem University), Matthew Audi (Bowdoin College) and Aydin Henderson (Wheaton College).

Dr. Barakat was a prolific scholar, publishing seventeen academic volumes, plus numerous essays and articles during his career. Much of his work focused on contemporary challenges facing the region such as alienation, exile, and crises of civil society. His path-breaking book, The Arab World: Society, Culture, and State (University of California Press, 1993), is considered a classic in the field of Arab studies. Beyond his influence as a social scientist, Dr. Barakat was also an award-winning novelist and short story writer whose creative works served as a bridge between the literary and academic communities. Two of his best-known novels were translated into English. Sitat Ayam (Six Days), published in 1961, has often been called “prophetically named for a real war yet to come in 1967” and served as a prelude for ‘Awdat al-Ta’ir ila al-Bahr (Days of Dust) about the June War of 1967.

The passing of Dr. Barakat is a tremendous loss to the academic community, and CCAS extends our sincere condolences to the Barakat family. You can read a longer biography, as well as remembrances of Professor Barakat written by colleagues and students on the CCAS website

5 CENTER NEWS

Recipients of the 2023 SFS Staff Excellence Awards (Left to Right): Julie McMurtry, Lauren Bauschard, Dana Al Dairani, and Robert Lyons

زكرملا رابخأ

Center News

بلاطلا

ثحاب رئاز

سيردتلا ةئيه رابخأ

Faculty News

Staff Updates نيفظوملا رابخأرخآ

يراشتسلأا

Clockwise from top left: Suhair, Leen, Aydin, Matthew

What Iraq Tells Us About DISPLACEMENT

Salma Al-Shami

Salma Al-Shami

Over pizza in the charming town of Ankawa on the outskirts of Erbil, Iraq, survey field researchers start telling their stories from the field. “I’m visiting this one house, and I come to the question about ‘do you consider yourself displaced,’” recounts a veteran Iraqi researcher. “The hajji [elderly man] stares at me silently for a minute, and then with a deadpan expression on his face says, ‘Do I consider myself displaced? No, I consider myself a lawyer!’ He then angrily yells at us to get out.”

The table erupts in laughter. The casual outing in summer of 2018 had been proceeded by a week’s worth of training workshops on survey and interview best practices, discussions on questionnaires,

and logistical meetings in a stuffy, high-rise hotel on Erbil’s 60 Meter Street. Research teams from Georgetown University (GU) and from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) were gathered in preparation for the latest round of qualitative and quantitative data collection for the joint project Access to Durable Solutions Among Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Iraq.

The first-ever study of its kind, Access to Durable Solutions Among IDPs in Iraq followed, over a five-year period, nearly 3,600 Iraqi households that had been displaced by ISIS/ISIL. In this one evening away from official formalities, what crystalizes among the GU and IOM teams is that the study’s substantive contributions and innovations stem from the strengths of this academic-NGO partnership.

In addition to contributing to the study’s methodological rigor, GU’s participation ensured that the research was not an extractive process of collecting data on a given population in service of knowledge creation. The GU team used all resources at its disposal—including input on budget allocation and the team’s status as educators—to ensure that both the IDP households themselves and the Iraqi research teams benefitted from the study. As such, the partnership reaffirmed that the transfer of knowledge, skills, and benefit from participation in research need not be unidirectional.

The commitment of IOM’s research leadership to the project ensured not only continuity of material resources to sustain it, but more importantly, knowledge of the intersection between IDPs’ self-reported challenges and proposed humanitarian policy solutions and initiatives. IOM field researchers and local staff provided invaluable feedback on questionnaires and new policies and laws that affected the study and its trajectory.

Six rounds of surveys and qualitative interviews with the same IDP households between 2016 and 2021 sought to assess how, when, and if Iraqi IDPs were reaching one of three, “solutions” to their displacement: voluntary return home, local integration, or resettlement to another country or location. Determination of whether these solutions

6 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University NEW RESEARCH

Untitled Etching by Bev Samler Courtesy of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here project

were achieved were based on eight criteria outlined by the Inter Agency Standing Committee’s (IASC) Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons: safety and security, standard of living, livelihood, housing, access to documentation, family reunification, participation in public affairs, and access to justice.

Of the many findings the study unearthed in these numerous reports, perhaps the most important was to highlight the need for the IASC Framework to be more deliberate and explicit in its accounting for IDP preferences in what they considered the “end” of displacement. The answer to the question “when does displacement end?” for some was simply, “it doesn’t.” As such, the “end” of displacement should not be thought of in terms of an arrival point or a solution but instead of an ever-evolving process of access and belonging.

“Do you consider yourself displaced?” was a key question leading to this finding. Its purpose was to give voice to IDPs’ self-perceptions and compare them against standardized indicators measuring attainment of a “durable solution,” defined by the IASC Framework as being achieved, “when IDPs no longer have specific assistance and protection needs that are linked to their displacement and such persons can enjoy their human rights without discrimination resulting from their displacement.”* While many of the Iraqi IDP households represented by the study had met benchmarks of a “solution,” by the final round of data collection in 2021, more than half of all IDP households living in displacement indicated they still considered themselves displaced.

The five-year study yielded six summary reports on the experience of protracted displacement; five thematic and policy reports on topics such as livelihoods and economic security and experiences of female-headed houses; and three academic papers investigating education in displacement and experiences of return. Findings from the study were publicly disseminated at numerous presentations for audiences variously

gathered in front of the International Forum on Migration Statistics, Mercy Corps, the Gulf International Forum, the World Bank, IOM-Iraq, and the University of Kurdistan, among others.

Making such deliverables feasible required the herculean efforts of a large team. Lorenza Rossi, IOM’s Regional Data Hub and DTM Coordinator, conceived of

encouraged to learn how to use the qualitative and quantitative data for research papers and projects.

the project and CCAS Professor Rochelle Davis, shepherded it for its duration. ISIM professors Susan Martin, Elizabeth Ferris and Katharine Donato, CCAS and ISIM staff members Abbie Taylor, Grace Benton, Dana Al Dairani, and Vicki Valosik, and IOM-Iraq’s Olga Aymerich, Erin Neale, Shano Mohammed, Mazn Shkoor, and more than 25 Iraqi field researchers pooled collective talents to keep the behemoth study in motion. This core group conceived of topics and populations to include, wrote interview questions, programmed software, gained necessary legal access letters, oversaw fieldwork and conducted interviews, authored reports, and organized events and disseminated findings online and in print. Teams of GU student research assistants painstakingly translated interviews, coded qualitative excerpts, cleaned data, and conducted literature reviews and secondary research. In Dr. Davis’ courses over the years, undergraduate and graduate students were

In the field, despite the question of whether respondents considered themselves displaced being met with resistance if not ridicule, IOM’s team of Iraqi field researchers became the mediators of researchers’ intention and respondents’ understanding. Training workshops and handbooks the GU team ran and authored over the years became key pieces of capacity building intended to hone interviewer skills and enable future employment. The hope was that those facilitating the study could be better equipped to handle challenges on both this project and others. The workshops and handbooks discussed strengths and tradeoffs of quantitative and qualitative data; how to write questions; respondent selection considerations; and best field interview practices in conducting both surveys and qualitative interviews. The interviewer team became one that IOM subsequently employed in other projects. At the same time, the feedback of the interviewers on the wording and content of the questions alerted the research team to key themes that were conspicuously absent or sensitives that were obscuring results.

This capacity development component of the study complemented a second distinguishing feature: the largest line item in the budget of the project was an in-kind payment of monthly mobile phone credits to the IDP households who remained in the study. IOM Iraq’s field researchers used the TextIt System, a text messaging platform, to maintain monthly contact with IDP families participating in the study and to verify and update their locations as they moved around in Iraq.

What also became increasingly clear over the course of the project was that the study’s results—and indeed the data itself— needed to be more widely distributed and accessible. In service of this goal, the team translated many reports and findings into Arabic so that they could be accessed by a wider range of people

7

Members of the IOM and Georgetown teams enjoying a pizza break with survey field researchers during the 2018 project training in Erbil, Iraq. Courtesy of Salma Al-Shami continued on p.

15

Honoring the Memories of Iraqi Academics

By Besan Jaber

She will not awaken, will not come back to life. I thought that I could carry on, would carry on her legacy. I knew I would never be half the lawyer, half the teacher she was, but I thought I could carry on, keep her memory alive. I would ask the same questions, meet the same silences, get the same look that conveyed a deadly warning. But what was her death if I did not ask? What was my freedom if I did not question?…

- Dr. Persis Karim

These lines are an excerpt from the poem “ When We Dead Awaken,” written by Dr. Persis Karim in memory of Iraqi academics Muneer al-Khiero and his wife Leila al-Saad. The couple worked together at Mosul University’s College of Law—Dr. Al-Saad as Dean and Dr. Al-Khiero as a lecturer. On June 21, 2004, both were found dead in their home in the Dandan neighborhood, South of Mosul. The pan-Arab newspaper Asharq Al- Awsat quoted a police official as saying that the killings were not motivated by theft, as large sums of money were found, untouched, in the couple’s home.* Instead, Al-Saad and Al-Khiero were likely the victims of targeted assassinations, placing them among the hundreds of Iraqi academics and educators brutally killed in the decade following the U.S.-led invasion and occupation of the country. Although the exact number is not known, the Brussels Tribunal verified and published the names and details of the deaths of over 400 Iraqi academics who were killed—more than half at point-blank by firearms, while others were kidnapped, including some by security forces, and died in detention.

Karim’s poem commemorating the couple is part of “Shadow and Light,” an on-going project to set up exhibitions of photographs and artists’ statements honoring the hundreds of Iraqi academics and educators brutally killed in the decade following the U.S.-led invasion and occupation of the country. “Shadow and Light” was founded in 2018 by poet and San Francisco-based activist Beau Beausoleil, who

sees the project as one of “witness, memory, and solidarity.” The women and men memorialized in the exhibit enriched diverse fields of knowledge, ranging from history to calligraphy to the study of bees, said Beausoleil. “Each assassination represented an attack on the underlying principle of education—to share knowledge—and served as a threat to scholars throughout Iraq that they were at risk.”

For the project, writers and artists reach out to Beausoleil to select an Iraqi scholar to honor, using a list of names compiled by a Spanish NGO. They then photograph a scene, devoid of people or animals, and write a reflection on the image and the person they are commemorating. Like many of the contributors reflecting on the lives of the slain academics, Karim did not know much about the personal lives of Al-Saad or Al-Khiero, but as a poet and professor of comparative and world literature at San Francisco State University, she shared their passion for education and knowledge.

CCAS Professor Rochelle Davis, whose work has for many years focused on Iraq, was also a contributor to “Shadow and Light.” She chose to write her reflection on Dr. Aiad Ibrahem Mohamed Al-Jebory, a former neurosurgeon at Tikrit University, an institution with which Davis has been working on a grant project to help develop the university’s research program.

Thus far, 57 Iraqi academics have been commemorated by a community of writers, poets and artists from across the globe. As many of the artist statements are written in English, Davis felt it was important to think about how the growing collection of narratives and images could be communicated back to Iraqis. With support

8 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University STUDENT FEATURE

بﻼﻄﻟا ﻦﻣ صﺎﺧ Student ea ure (Wissam)

Image by Dr. Rochelle Davis as part of her reflection, written in memory of Dr. Aiad Ibrahem Mohamed Al-Jebory

from Beausoleil, Davis began working with a team of research assistants to translate the artist statements into Arabic over a several month period. The team included three MAAS students—Noor AlShaikh, Hoda al-Haddad, and myself—as well as CCAS Professor Dr. Mohammad al Ahmad. After we translated the statements, they were then reviewed by Professor Al Ahmad to ensure the Arabic was correct. The Arabic translations are available online (see link in box below) and will be included in future exhibitions of “Shadow and Light” alongside the English, as Beausoleil continues to seek venues to host exhibitions.

Translating different forms of poetry and prose was challenging, as many of the statements are deeply personal and carry complex meanings of human connection. AlShaikh, a native Arabic speaker, shared that she found herself asking, “How can I transform a poem in a language that I know, yet I do not have a strong emotional connection to, into Arabic?” Through her work on the project, she realized that translation is a creative process that entails reproducing not just the words, but also the meaning in a piece of writing. For al-Haddad, working with the words by and about others created a sense of connection. “I felt that the authors of these letters, the people to whom the letter is written in the memory of, and I have traveled together through time and space,” said al-Haddad. “In some way we all exist outside of our physical forms from the moment the words are written.”

Focusing on the lives and deaths of these slain individuals was a somber process as well. “I tried to put aside my own emotions,” said Prof. Al Ahmad, “in order to produce Arabic texts that communicate the authors’ feelings and words about these departed souls.” He asked that readers forgive any errors in translation “as our minds were preoccupied, and remain so, with these souls suspended in the Iraqi heavens.” As my role included fact-checking the translated texts using Arabic news outlets and social media posts, I had to look up the name of every one of these assassinated scholars. The list is long indeed, and it saddened and disheartened me. Yet reading the warm words of their colleagues, students and family members, along with the statements and poems produced by the artists, I also felt deeply motivated and a little uplifted. As a way to honor these individuals, I decided to say their names out loud even when I was alone working from my office with no one there.

Selected writings and photographs from the “Shadow and Light” project have been part of both physical installations and virtual exhibitions hosted at universities across the country, including UC Santa Barbara, University of Michigan, University of Illinois, the University of Pennsylvania, as well as the Liverpool Arab Arts Festival. Much more than a collection of art and poetry, the reflections included in “Shadow and Light” serve as an archive and remembrance of Iraqi scholars whose lives were cut short by violence. In the words of Professor. Davis, “they remind us that these professors taught students, conducted research, and wrote books that advanced human knowledge. They also invite us to remember them and honor their lives.” The “Shadow and Light” project also serves as a history and demonstration of international solidarity with the people of Iraq, through the global network of poets, artists, academics, and translators who have reflected on the lives and contributions of these individuals. We hope that our translations will contribute to this effort. ◆

*See https://archive.aawsat.com/details.sp?issueno=9165&article =240953

Besan Jaber, a second generation Palestinian from Jordan, just completed her first year in the MAAS program.

Learn more

You can visit a virtual exhibition of “Shadow and Light,” including artist statements and their translations, on the website of Pentacrest Museums at the University of Iowa. Beausoleil is seeking additional venues to host exhibitions. https://pentacrestmuseums.uiowa.edu/shadow-light

9

Photos by Dr. Persis Karim to accompany her artist statements “In the Time of Cherries” and “When We Dead Awaken,” written to honor Dr. Leila Abdu Allah al-Saad and Dr. Muneer alKhiero, respectively.

The American Invasion and Authoritarianism

Professor Joseph Sassoon discusses the durability of authoritarianism and the decline of American predominance in the years following the Iraq War.

By Joseph Sassoon,featuring research conducted with Motasem Abuzaid

The American invasion of Iraq in 2003 was not an isolated episode—as interventions by superpowers have been a recurring feature in the contemporary history of the Middle East and its authoritarian trajectories. Even so, the American invasion stands out in terms of its scale and the reach of its aftermath. The events of 2003 have influenced Arab regimes and societies far more than other wars or softer forms of global involvement—and in ways that remain more distinct today.

The fallout and lingering effects of the American invasion included regional polarizations, securitization, sectarian/ethnic manipulation, transferred counterinsurgency practices, and the expansion of carceral systems. Although Middle Eastern regimes varied in their capacity to translate their learning in the face of social and geopolitical pressures, these fallouts found unique expression in the “rogue states” that were targets of American democratization campaigns and played a key role in autocratic revival and well-being post-2011.

Historically, western interests in the Middle East have hardly been homogenous. U.S. foreign policy found its way into combatting Soviet (read communist) influence and preserving American oil interests. Beyond maintaining the political stability of allies and the region as a whole, core interests also

included economic liberalization through international financial actors like the IMF and World Bank and political liberalization through the promotion of democratic values and human rights. Political players in the region learned how to navigate these contrasting pressures and turn constraints into opportunities. Even so, an invasion of this scale was unprecedented, and Arab leaders

and bureaucrats were equipped to face neither the American hegemon nor popular threats to their rule should they align themselves with the occupying force.

The positions of senior figures in various Arab establishments reflected a great deal of uncertainty in the immediate aftermath of the invasion. A patent line of ambiguity, for example, emerged in the Syrian narrative. On the one hand, Syrian officials described American actions as “genocide,” “terror,” and “war crimes,” and expressed their approval of suicide missions against the United States. On the other hand, they welcomed a visit from Colin Powell and signaled to observers that Syria was ready to commit to further reforms, albeit on a gradual and restricted scale.

Among the most noticeable and immediate consequences of Saddam Hussein’s toppling was the Libyan nuclear disarmament. This was Gaddafi’s gambit to set the record straight with the United States, particularly given the sanctions on Libya and the U.S. pursuit of banned weapons. But at the same time, Libya denounced the wide mismanagement of Iraq’s daily affairs and “bloody operations” like the killing of Uday and Qusay Hussein.

Iran took the opposite approach, doubling down on nuclear weapons, which it considered the only guarantee against foreign intervention. The regime capitalized on the anti-U.S. sentiments prevalent across the region—which have contributed to the election of conservative

10 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University FACULTY FEATURE

Fa culty Fe a tur e صﺎﺧ ﺲﯾرﺪﺘﻟا ﺔﺌﯿھ ﻦﻣ

ىﺮﻛﺬﻠ

Prosperity Digital Print by Wilson Hill Courtesy of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here project

In Me mo r ia m (in me mo r y o f so me o ne

leaders—to justify its growing domestic repression and military involvement in Lebanon. As Iran’s intentions were revealed, other Arab countries followed suit, and by the end of 2006, Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and the UAE had all declared their intentions to acquire a “nuclear capability for civilian purposes.”

Post-2006: Doubling Down on Authoritarianism

While the United States was well-prepared for a military invasion, it was ill-equipped for the administration of Iraq. As the U.S.occupation gave rise to various ideological groups, the insurgency expanded into a prolonged and vicious conflict that resulted in the large-scale displacement of Iraqis. Despite setting up key institutions of Iraqi democracy, the U.S. was compelled to gradually deprioritize democratic influences as it lost control of the security situation.

Divisions grew, with two particularly trendsetting polarizations taking place in the mid-2000s: those between Sunnis and Shi’as and between anti-American and anti-Iranian camps. The former, based on sectarian divisions, was due to the de-Baathification and dissolution of the army, followed by insurgency, then civil war (2003–2008). The latter did not fall neatly along the lines of Arabs and non-Arabs. Instead, what emerged was more of a “New Arab Cold War” that revolved around the representation of “Arab interests” between states (e.g., Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia) and “radical” non-state actors (e.g., Hezbollah and Hamas) that stemmed from social movements appealing to an Arab-Islamic narrative.

By 2005, Syria’s stronger ties with Iran became critical in repositioning the state’s relations and policies with its neighbors, and all attempts to isolate Syria failed. Similarly, Gaddafi gained significant confidence following Iraq’s Civil War. He defended the “resistance” in Iraq and, by 2007, backed the Iranian nuclear project (even though it contradicted his own earlier stance). In response to social pressures, Gaddafi would fall back on anti-U.S. rhetoric.

Iran emerged as the major winner of the invasion, with its authoritarian stance faring better given the country’s ideological, economic, and geopolitical prominence. In the

process, Iran achieved two of its main goals: putting a stop to territorial threats from Iraq and gaining an ally government in Iraq, which it sustained through several spheres of influence including loyal politicians, covert networks and militias. Iran was also free of its two major regional nemeses— the Taliban and Saddam Hussein—thanks, ironically, to the United States.

Regimes in the Gulf endeavored to maintain intimate ties with Washington, even against the demands of their respective populations. But throughout the 2000s, the GCC established neither high-level diplomatic missions nor embassies in Iraq, and hence fell short in joining the efforts of building stable and democratic statecraft in Iraq to check the Iranian influence.

By the end of the 2000s, Arab regimes employed new mechanisms of legitimation, based on multiple polarizations and on the structures of American militarism. The Arab uprising of 2011—which the dominant perspectives of the 2000s failed to predict— exposed the full spectrum of the regimes’ learning of authoritarianism. Following 2011, regional polarizations evolved into a vacuum in global leadership. The result was the further securitization and militarization of the various camps involved in what would emerge as a new institutional assemblage of regional security.

Key learning in terms of intelligence and security cooperation took place within these alliances. For example, the Abu Ghraib model inspired a number of regimes to adopt supermax prisons as part of their punitive measures. And while the official number of prisons in the region is estimated to be over 1,600, many informal prisons were constructed by non-state actors (e.g., Hezbollah, al-Qaeda, and the Nusra

Front) following critical milestones such as the 2006 Lebanese war or the 2011 Arab uprisings. Sparking sectarianized conflict, a technique used in the past by Arab regimes, became a key tool that helped these groups thrive and also served as a defensive securitization tactic.

Authoritarianism is rising globally and remains strong in the region. This is supported by recent findings from the Arab Barometer, which measures social, political, and economic attitudes across the region. A 2022 Arab Barometer survey of 23,000 participants across nine Arab countries and the Palestinian territories showed that the “majority of citizens across the Arab world are losing faith in democracy as a system of governance to deliver economic stability.”

Conclusion

The American invasion in 2003 was a critical juncture point that altered both the U.S. hegemony and the regional balance of power for the following two decades. It could be argued that the invasion helped sustain the durability of authoritarianism in the Middle East—albeit in disproportionate ways. While the fall of Saddam’s regime made each state in the region liable to domestic and international pressures to reform, these regimes—already remarkable in their authoritarian resilience—adapted well. As the repercussions of American intervention and the dynamics

p. 15

11

Arab Puzzle Newspaper and stitch collage by Jennifer Vickers Courtesy of the AlMutanabbi Street Starts Here project continued on

The Lessons We Choose to Draw

By Paul J. McKinney

In September 2003, just a few violent months after the Bush administration proclaimed major combat operations had ended, the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) – the US-led civilian body charged with administering occupied Iraq – organized a two-day workshop in Baghdad to identify best practices for countries transitioning from state-led to market economies. Seeking to draw lessons that may be applicable to Iraq, the CPA invited former ministers and finance officials from Central and Eastern European countries to share their experiences. Evidently impressed by Poland’s “shock therapy,” in which Warsaw introduced a drastic neoliberal package during the country’s emergence from Soviet domination in the early 90s, the CPA appointed the former Polish finance and prime minister responsible for those reforms, Marek Belka, to head the CPA’s Office of Economic Policy. With Belka at the helm, lessons learned from Poland’s transition would be univer-

salized and superimposed onto Iraq, with little regard to contextual factors. Iraq was, after all, seen as a blank canvas upon which the West could project its own visions.

Zealously driven by a belief that markets are the most efficient way to organize a society and, by extension, to optimize individual freedom, the CPA issued what can only be described as the economic equivalent to the U.S. military’s “shock-and-awe” campaign. Within a year, the CPA issued an astoundingly high number of Orders to build the new neoliberal state. Some of the most notable included, for example, selling about 200 state-run enterprises,

12 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University ALUMNI FEATURE

ﻦﯿﺠﯾﺮﺨﻟا ﻦﻣ صﺎﺧ

Sombras Pasean Por La Casa de los Recuerdoes / Shadows walking around in the house of memories Etching, Cardboard & Polyethylene, pencil by Anne Moreno Courtesy of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here project

eliminating the right to unionize in most sectors, outlawing labor strikes, opening Iraq’s banks to foreign ownership and control, mandating a regressive flat tax on income, lowering the corporate rate to a flat 15%, eliminating taxes on profits repatriated to foreign-owned businesses, and even prohibiting Iraqi farmers from re-using “protected” varieties of genetically modified seeds.

Just as important as providing physical security, these reforms were seen as essential to enhancing human security, and the surest path to achieving democracy, stability, and prosperity for Iraq. According to this logic, once the remnants of the regime were ousted, a comprehensive sanctions regime lifted, and market-oriented reforms enacted, foreign direct investment would be bountiful, and its fruits would trickle down. Revenues from Iraq’s natural resource wealth would generate the national funds needed for its reconstruction, elections could be held, and a constitution drafted. The order of events here matters: Iraq’s neighbors and, indeed, the entire Arab World, would see a thriving democratic country because it was “open for business.” Meanwhile, in the real world outside the Green Zone fortress, the security situation worsened each day, and unemployment soared to nearly 60 percent. For anyone paying attention, it was clear the country was burning. Undeterred by events on the ground, however, the CPA vigorously pursued the opening of the Iraq Stock Exchange: the September workshop had, after all, identified a functioning equity market as a critical part of any economic transition.

Twenty years later, the results of the CPA’s attempts to remake Iraq in its vision speak for itself. According to a 2020 World Bank report, which uses similar metrics as the CPA to measure economic growth, Iraq’s non-oil GDP has remained flat for the past two decades, its economy continues to suffer from low labor participation and one of the lowest female participation rates in the world, and the country places just above Afghanistan in its “Ease of Doing Business” ranking. And despite (or partly due to) its hydrocarbon wealth, Iraq has abysmally low levels of human and physical capital, coupled with the third-highest poverty rates in the world among upper-middle-income countries. While most Iraqis struggle to make ends meet, elites have captured the state and treat public resources like personal slush funds. This was evidenced most egregiously in October 2022, when the Ministry of Finance announced $2.5 billion dollars of Iraq’s national funds had been stolen from the General Commission of Taxes account over

the previous year by five shell companies, implicating several senior government officials. Few are holding their breath that the funds will be fully returned or that justice will ever be served.

With Iraq back in the news surrounding the 20th anniversary, I’ve thought about the U.S.-led occupation a great deal in recent weeks, and I keep coming back to this “lessons learned” workshop of 2003, dominated as it was by self-proclaimed experts – many with limited regional knowledge. Although I was not present, it is not difficult to imagine how those conversations unfolded, and we heard echoes of them in several recent articles and events held contemplating the invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq. Sadly, many of the popular accounts from U.S. perspectives frame the tragedies of the Iraq War primarily as a result of poor execution, focused mainly on poor planning and administrative dysfunction. While it is well-documented that the Bush administration failed to prepare for the “day after” it began occupying Iraq, and turf wars between Foggy Bottom and the Pentagon often resulted in incoherent policies, far less attention was given to the deeper structures and sets of beliefs that informed decision-making to go to war and which shaped the policy prescriptions that followed, such as the dogged conviction that neoliberal reforms necessarily lead to free, open, and prosperous societies.

Like the workshop twenty years ago, these popular narratives – perpetuated by “thought leaders” in the DC think tank circuit – are dangerous because they provide a false sense of greater understanding without seriously challenging any underlying assumptions. Without space for deeper reflection, we risk misidentifying the root causes of the cataclysmic injustices perpetrated against Iraq and Iraqis. And if only superficial critiques of the Iraq War are made accessible, then we should not be surprised when the mainstream “lessons learned” literature is confined to ahistorical and myopic thinking, offering only small tweaks along the margins of a faulty system anchored in notions of American exceptionalism and neoliberal beliefs that are clearly in need of fresh thinking and radical transformation. The importance of this publication and others like it is that they encourage critical analysis, and act as a counterbalance, offering alternatives to the same tired ways of thinking and set of tools that contributed to the tragic consequences of the Iraq War twenty years ago. ◆

13

Paul J. McKinney is a 2021 MAAS alum and a veteran of the Iraq War.

Streets Have Souls Collagraph by Iram Wani Courtesy of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here project

No Good Way to Occupy a Country: Conceptions of Culture in the Iraq War

Q&A with Professor Rochelle Davis

CCAS Professor Rochelle Davis’ latest book project examines the role that the U.S. military’s conception of culture played in the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Her work—which makes use of interviews with U.S. servicemembers and Iraqis, as well as military documents, cultural training materials, journalist reports, and soldier memoirs—analyzes the narratives that are told about Iraqis, Afghans, Arabs, and Muslims and explicates the paradoxical military objectives of cultural sensitivity and occupation. Professor Davis, who has published two prior books on Palestine, is currently finalizing the manuscript for No Good Way to Occupy a Country. She shares a bit about her project below.

How did you get started on this research?

When I came to teach at Georgetown in 2005, the U.S. occupation was in its third year and CCAS had invited the late Anthony Shadid to speak on his book Night Draws Near: Iraq’s People in the Shadow of America’s War. I recall an American military officer in the audience remarking that “we are trying to do better, we are trying to provide cultural training now.” As an anthropologist whose academic discipline is about culture and society, I was intrigued and wondered about the content of military cultural training. I began going to lectures by civilians who worked for the military about their vision of “cultural training” and collecting material and eventually trained six student research assistants to conduct interviews with veterans and current services members. The

research—which includes interviews with 70 U.S. military personnel and 50 Iraqis, plus thousands of pages of written material and videos—grew into a book project, which is now almost completed.

What are some of the takeaways from the book?

First, that so much of the cultural training is mired in Orientalist and/or racist tropes copied and pasted from material that is ten, twenty or seventy years old. For example, the

the entire mission: “American success or failure in Iraq,” it reads, “may well depend on whether the Iraqis [...] like American soldiers or not.” This idea of the offendable Arab gets repeated in a Department of Defense Pocket Guide to the Middle East from 1962: “To avoid offending Arabs, you must observe their customs when you are with them. If you do, you will gain their warm friendship. Since their religious and social customs are closely intermingled, one misstep on your part might violate both.” Fast forward forty years to the American invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan—and soldiers were still receiving similar information. One reported being told in his cultural training: “Instead of shaking hands, use the hand gesture of putting your palm over your heart. Not showing the bottoms of your feet. The type of conduct that would be offensive to an Iraqi you picked up quickly.”

idea that Arabs take offense easily has been baked into military guides across the decades. The 1943 U.S. military’s Short Guide to Iraq issues a warning to take care in not offending locals, as that could undermine

This trope of Arabs taking offense suggests that somehow Arabs are rigid and bound by their own behaviors, and thus are not familiar with other ways of life. The focus on avoiding offence also struck me as misplaced. Perhaps because I saw the invasion of the country (any country) as wrong, the concern that a soldier might do something “offensive” seemed to focus on something trivial, given there was so much American violence toward Iraqis and the discounting of Iraqis’ expertise and knowledge. Suggesting that “causing offense” was what was critical to the occupation missed the point about why some Iraqis were not supportive of the U.S. presence in Iraq. One soldier described how, in his experience with cultural training, the power dynamic was framed almost as if the soldiers were tourists in a host country, and causing offense could result in getting

14 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University FACULTY SPOTLIGHT Faculty spotlight ةئاضإ ىلع ةئيهلا ةيميلعتلا

Mealtime etiquette tips from “A Short Guide to Iraq,” produced in 1943 by the U.S. War and Navy Departments, advised soldiers— even “southpaws”—to eat only with their right hands and to accept up to three cups of coffee, when offered, but to decline the fourth.

laughed or shouted at or kicked out of a café. “You know,” he recalled learning “here are three or four things that you can do to not offend people. In sort of the same way that you would tell a tourist, which was not really … I don’t think at the depth of what we needed.”

Another example is the simplified depictions of the kufiya. For example, a red and white kufiya, according to the Iraq Culture Smart Card, meant the person was from a country with a monarchy, while black and

cultural training material relied on wrong information and Orientalist stereotypes and failed to demonstrate an understanding of the big picture. Was it racism on the part of the developers? Lack of time? Lack of knowledge? Much of the material lists no author, so it is difficult to probe further.

In other words, American soldiers being sent to invade and occupy Iraq to free its citizens were being told that Iraqis were not ready for democracy. This is despite the fact that Iraqis were on the street demonstrating for elections to be held after Paul Bremmer cancelled them in June 2003.

card was produced in 2006 by the Marine Corps and provided to U.S. soldiers as a pocket reference to the Iraqi people, their customs and history.

white indicated he was from a country with presidential rule. A plain white kufiya signified that the wearer had not been on pilgrimage to Mecca. But what did all this have to do with Iraq? Over and over again the

A second takeaway from the book was how the cultural training was counter to the U.S. government’s stated reasons for the invasion and occupation of Iraq. The examples are many, but a blatant one is that President Bush cited, as one of three reasons for the invasion, the goal of bringing democracy to Iraqis. Many of the soldiers interviewed gave the same reason as to why they thought they were there. At the same time, the Soldier’s Handbook to Iraq, published by the Army 1st Infantry Division in 2003, declared that Iraqis are essentially unable to practice democracy because of their culture and faith: “[Their] desire for modernity is contradicted by a desire for tradition (especially Islamic tradition, since Islam is the one area free of Western identification and influence). Desiring democracy and modernization immediately is a good example of what a Westerner might view as an Arab’s ‘wish vs. reality.’”

In presenting my research, I’ve had a number of military contractors and personnel ask me how I would recommend it be done differently. My response is always: “I’d start by not invading other countries”—hence the title of my book. I know that military personnel don’t have a choice. They have to obey their orders.

Could the cultural training have been better? Certainly. Would it have changed the outcome? Unlikely. The most damaging impacts of the occupation resulted not from the types of surface-level, cultural interactions covered in the training materials. They resulted instead from policies that created sectarian political representation, postponed elections, and disbanded the Iraqi military and police—to name but a few. ◆

continued from p. 11 DISPLACEMENT

AUTHORITARIANISM

continued from p. 7

affected by—and endowed with power to affect—displacement-related policies. More significantly, the GU-IOM partnership concluded by creating a website where not only the published reports, but also the methodology, questionnaires, and merged panel dataset (combining rounds one through five of the study) are all publicly available for download and use.*

At the inception of the study in 2015, IOM Iraq reported that there were approximately 3.3 million IDPs in the country. Today, the IDP population stands at just under 1.2 million. These numbers, however, are calculated using the internationally recognized and codified standards of “counting” IDPs. If the IASC Framework suggests that most of Iraq’s IDPs have, over the years, found a solution to their displacement, Access to Durable Solutions Among

IDPs in Iraq should serve as a reminder that it is equally important to take into account how IDPs see themselves; or in other words, to remember not only what the Framework tells us about the end of displacement in Iraq, but what Iraq tells us about the end of displacement. ◆

Salma Al-Shami is Director of Research at Arab Barometer, a non-resident visiting scholar at CCAS, and an adjunct professor in the Global Human Development Program. She served as the chief data analyst for Access to Durable Solutions Among Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Iraq.

*See also https://ccas.georgetown.edu/resources/iom-gu-iraq-idp-study/ to read the IASC Framework and summary reports.

of instability and war in Iraq unfolded, this resilience allowed them not only to survive threats at home but also to reap benefits from the regional insecurity left by the United State—and resulted in the clear decline of American predominance in the region. ◆

Joseph Sassoon is a professor of history and holds the Sheikh Sabah Al Salem Al Sabah Chair at CCAS. The research for this article was conducted with Motasem Abuzaid, an alum of the MAAS program and current PhD student at St Antony’s College, Oxford.

15

Associate Professor Dr. Rochelle Davis is the Director of Graduate Studies and holds the Sultanate of Oman Chair at CCAS.

Depictions of the kufiya from the “Iraq Culture Smart Card.” The

CCAS Conference on Iraq Twenty Years On: Prospects of Epistemic Reconstruction

By Motasem Abuzaid

Commemorating the 2003 invasion of Iraq twenty years on, CCAS hosted a conference exploring the invasion’s economic, social, and geopolitical consequences, as well as its representation in Iraqi arts and culture. The conference, held on March 31 in partnership with George Mason University’s Middle East and Islamic Studies Program and the Arab Studies Institute, also included a screening of the 2004 documentary, About Baghdad, the first film made after the fall of the Ba‘th regime. The film screening provided a way of foregrounding native Iraqi voices and perspective on the aftermath of the war and was followed by a discussion with the film’s directors.

The conference’s first panel session, titled “The Invasion of Iraq and After: Twenty Years On,” offered concise insights from a broad range of angles: the occupying forces, the state, the geopolitical order, and most importantly, ordinary Iraqis. It convened panelists with a considerable history of intellectual engagement with the subject,

while silencing certain historical events, Antoon highlighted how the “United States of Amnesia” has ignored or romanticized its actions (read congenital crimes) in the 1991 Gulf War and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. These actions, he asserted, led to the devastation of Iraq’s infrastructure, economic collapse, and the suffering of its people under American sanctions.

was inherent to Iraq and that Iraqis were incapable of democracy, contradicting one of the stated reasons for invading Iraq in the first place. (Read about her research on page 14)

who had the challenge of presenting their work in only twelve minutes each—twelve minutes for “twenty years and more, and one million lives,” remarked Iraqi writer Sinan Antoon on the magnitude of responsibility in the task at hand. With emphasis on the process of constructing historical narratives

Antoon, who is a MAAS alum, also pointed out the epistemic violence that has been perpetrated against Iraqis in various forms, such as the fragmentation of Iraqi identity, the introduction of ethno-sectarianism, and the looting of artifacts (roughly 170,000 artifacts from museums and archaeological sites) and cultural objects (more than a million books and manuscripts, not to mention the Ba‘th Party archives). In line with this argument, CCAS Professor Rochelle Davis illustrated the tools underpinning this epistemic logic by analyzing the cultural training material provided to U.S. military personnel about Iraq. Davis, who interviewed over 90 American soldiers between 2002 and 2007, reported that the majority found the cultural training to be unhelpful, but still used the vocabulary and framework from the training to make sense of their mission. The framing of Iraqi identity, she maintains, assumed sectarianism

Taking an economic perspective, Case Western Reserve University Professor Pete Moore used the concept of a war economy to understand how regulatory seizure has allowed organized criminal groups to take control of parts of Iraq’s public sector, leading to a form of “unbuilding” the Iraqi State. The state has not disappeared but rather has adapted to new political power, with the public sector expanding from 900,000 employees in 2003 to more than 3 million in 2015. However, these shifts have not led to improved socioeconomic outcomes for Iraq, which has one of the lowest human development index (HDI) scores. On the other end of political economy, Omar Sirri, a research associate at the University of London, highlighted the neglect of public infrastructure and the struggle for a “public” in Iraq. He gave the example of vendors of basic materials like speed bumps selling primarily to local residents rather than to the government, as it was beyond imagination to think of the state taking responsibility for public roads—a reality that underlines the lack of trust in the successive governments since the invasion. Years of for-profit governance have privatized social life to such an extent that a return to any semblance of public administration would be difficult—and even the idea of it has become hard to entertain.

Geopolitically, the 2003 invasion of Iraq led to a spillover effect of authoritarian adaptation and practices. These have included regional polarization, securitization, sectarian and ethnic manipulation, transfer of counter-insurgency practices, and expansion of carceral systems (which bred early cells of the Islamic State). Iran was the major

16 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University PUBLIC EVENTS

political winner, and China the economic. In this light, CCAS Professor Joseph Sassoon explored a new institutional architecture of regional security in which the Abu Ghraib model inspired the adoption of supermax prisons by various regimes in the region as a punitive, often militarized, measure.

The second session, “Perspectives on Cultural Production Post-2003,” included a discussion with Lowkey, a British-Iraqi hip-hop artist, academic, and political campaigner. Drawing on historical examples of cultural resistance against British colonialism, Lowkey underscored the importance of culture in moments of tension between the occupier and occupied. In his view, the U.S. employed “soft power” and cultural diplomacy to shape narratives about Iraq and the invasion. American and European companies were awarded contracts for psychological operations, with a focus on altering Iraqi perceptions of the coalition forces. In a sense, much of the cultural production has been co-written by intelligence networks or their corporate “extractivists” to acquire Iraq and warp the art created.

Teacher and art-maker Rijin Sahakian shared her own take on epistemic violence, noting the challenges facing Iraqi artists and local cultural production, such as the lack of funding, limited access to resources, and constant exposure to successive trauma and instability. She noted how Iraq and its artists can sometimes be instrumentally used or misrepresented, as exemplified in the use of exhibitions on Iraq to whitewash past actions of a particular government or “philanthropist” against the Iraqi people, or to publicly normalize the dehumanization of Iraqi victims and the display of their tortured bodies. On that note, Hanan Jasim Khammas, a postdoctoral fellow at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, insisted that the increased interest in translating and awarding post-2003 Iraqi fiction should be carefully considered, as it can lead to the commodification of people’s suffering into cultural products subject to market demands. After all, Iraqi literature should not be seen only as a record of pain and trauma, but also as a testament to life, creativity, and resilience.

In response to a question about the absence of U.S. invading forces in post-2003 Iraqi literature, the panelists noted how contemporary writing is still processing the 30 years of dictatorship and the horrors experienced under the Ba‘thist regime. They pointed out that the wounds of an eight-year war, the mass destruction in 1991, followed

by genocidal sanctions, all persist to this day. Still, to Khammas, the sentiments induced by the invasion were akin to an Iraqi Nakba, so to speak. Several observations stand in support of this analogy: The invasion went against UN charters, the death toll today nears a million, and the internally displaced approximate 1.2 million, while 8 million more are scattered across the globe. Throughout the 2000s, displaced Iraqis lived in the neighborhoods of Jaramana and Sit Zainab in Damascus right next to the Palestinians, in various districts in Istanbul and Berlin before the arrival of displaced Syrians, and formed cosmopolitan commu-

or views of how Iraq should be governed. Released in 2004, the film pushed against the post-invasion hegemonic media current of the time and remains relevant with more recent youth-led protests in the country against the “1,000 more Saddams” in place of the original. More than 600 protesters were brutally killed, injured, or forcibly disappeared in 2019 as the world looked on with indifference.

nities in London and Birmingham, as well as Detroit and Chicago. As such, how many decades of writing would it take to actually process the catastrophic consequences of the invasion—which are still manifesting—and elevate them to a level of collective consciousness that counters the epistemic and moral disregard for Iraqi lives?

The conference ended with a screening of About Baghdad (available on YouTube) and a panel discussion with its directors: Sinan Antoon, Suzy Salamy, Adam Shapiro, and Bassam Haddad. The filmmakers noted the importance of offering a non-linear, fragmented perspective and focusing on the voices of average Iraqis eager to share their stories. They sought to highlight that Iraqis were not a monolith by showcasing historical and cultural diversity and varied perspectives on the war. The multiple interviews and conversations elucidate how living under a dictatorship for so long could generate drastically different impressions on the calamitous potential of the occupation

“Do wars ever come to an end?” asked Sinan Antoon. They do end for the politicians and the pundits, he answered, but not for civilians—scars remain in the psyches of people, in their bodies, and in the urban and social fabric in which they live. Youth under the age of 25 today constitute two-thirds of the population and hardly remember the invasion. But these young Iraqis are also breaking free from narratives of victimization, incorporating revolutionary paradigms into the cultural landscape and moving away from colonial domination at the epistemic level (i.e. under the terms of tahrir or taghyir). Most of the panelists viewed collective action as a viable means for restoring the “public” and unshackling Iraq from the ethno-sectarian order that has been institutionalized in the post-invasion years. Compared to the discussions surrounding the tenth anniversary of the invasion, and despite the continued need for greater inclusion, Iraqi perspectives have been better represented in the major English-speaking publications and platforms this time around. Emerging scholarship—not to mention journalism, art, and literary production—dedicates more space to Iraqi voices, as exemplified through the works of Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, Sana Murrani, Omar Sirri, and Balsam Mustafa, among others. Such works also challenge America-centric knowledge production. Standing in the face of an imperial juggernaut may be exacting, but as the conference demonstrated, this generation of Iraqis is equipped with a more solid intellectual and political foundation to express the suffering of their people and to engage in epistemic reconstruction of resistant imaginations.

Motasem Abuzaid (MAAS ‘22) is a DPhil student in Politics at the Department of Politics and International Relations (DPIR) at the University of Oxford (St Antony’s College). Having lived in Damascus as a Palestinian, his current research examines the intersection of identity, local politics, and political violence in the Levant and Iraq.

17

◆

Dr. Omar Sirri, a research associate at the University of London, speaking at the “Iraq 2023: Twenty Years On” conference

A Hub of Knowledge Production

By Coco Tait

CCAS has been fortunate this year to work with over a dozen external partners to expand our audience and the diversity of our public programming, with our twenty-five hybrid and virtual events reaching thousands of live attendees. Highlights of the spring events programming included three major conferences and a multi-part series on Palestine, which are detailed below and on page 16.

Palestine: Land, Life, Dignity

Over the spring semester, CCAS collaborated with American University’s Arab World Studies to feature four prominent Palestinian scholars and activists in a multi-part series exploring questions relating to land, life, and dignity within anti-colonial struggles. Their work brings to the forefront the living textures of colonial existence and highlights the centrality of innovation and collaborative visions in working against colonial erasures and in helping to forge emancipatory futures. Dr. Nour Joudah provided a glimpse of how mapping initiatives for Palestine and Hawai’i defy settler temporalities and work to actively build emancipatory futures. Ghadeer Malek performed poetry and discussed her seminal compilation (with co-author Ghaida Moussa), Min Fami: Arab feminist reflections on space, identity, and resistance Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s event focused on the power of the story, and of indigenous feminist voices that articulate presence, steadfastness, and wounds. Shalhoub-Kevorkian emphasized that these voices mark existence, despite colonial attempts of erasure. Vivien Sansour shared images and processes of development for two of her most recent art works, “The Belly is a Garden”, and “Something Else is Possible.”

Towards Sustainable Peace and Democracy in Yemen

The conference “Towards Sustainable Peace and Democracy in Yemen” was held on January 9th, in partnership with the DC think tank Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN) and the Tawakkol Karman Foundation. It brought together leading Yemeni figures, subject matter experts, and Biden Administration policy makers to discuss how best to reach a permanent ceasefire and build a lasting peace. The conference highlighted how the U.S. and the international community can play an important role by uplifting Yemeni voices, addressing major humanitarian crises, and supporting the regional economy. For this conference, CCAS served as a resource and hub for knowledge production by providing the logistical management and incoming CCAS Director Dr. Fida Adely delivering opening remarks.

The Druze in their Adopted Lands

On April 14-15th CCAS, in partnership with the American Druze Foundation (ADF) and the Department of History and Archaeology at the American University of Beirut, hosted The Druze in their Adopted Lands. The conference, which brought together panels of leading researchers from across the United States, Europe, and the Middle East, explored the social and cultural evolution of the Druze, and the political roles of Druze communities, both in their countries of origin as well as in the diaspora. Among the speakers and moderators were current and former CCAS American Druze Foundation Fellows, including Dr. Benan Grams, Dr. Graham Pitts, and Dr. Lindsey Pullum

Coco Tait is the CCAS Events and Program Manager.

Education Outreach Explores the Long 19th Century

During the week of July 31 to August 4, CCAS hosted the 2023 Summer Teacher Institute, “The Long 19th Century in the Middle East and North Africa, and Its Global Impact.” The institute provided educators with a framework for understanding and teaching about the forces, groups and individuals who were agents of the enormous changes that took place during the mid-1700s to early 1900s—a period known as the "long nineteenth century"—and their impacts on people at all levels of society. Several Georgetown faculty, past and present, were among the speakers, including Joseph Sassoon, Mustafa Aksakal, Emad Shahin, Daniel Neep, Graham Pitts, and Benan Grams. The institute was made possible by a Title VI grant from the U.S. Department of Education and held in partnership with the Alwaleed bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding.

18 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies - Georgetown University

PUBLIC EVENTS

Astute War

By Shano Mohammed

Yesterday my town fell ill at dead of a sunless dawn from its eyes, a fire blazed dazzlingly everyone rode

From a Phoenix bird to ants’ swarms.

At the feet of astute war, brought to their knees, until they grew frail, mothers in faint voices wept from what they have bled, for what they have borne. on sidewalks and under tents, children were born others were abandoned little girls were placed, Under barren trees and on hills, for fate to step in. grandmothers went underworld not even a slight handwave

for a goodbye to hold on Solemn kisses were left On forehead of youth years Spring dreams by tombstones at rest one prayer mat centered muezzin and saint Whose minaret died

For the sake of marine corps I asked my mother who are the new arrivals? shouldn’t we serve visitors tea? what differs them from the usual? little did I know! our tea and land fell in their hands and we no longer owned our house little did I know she was making Sophie’s choice to remain and have faith or flee and save us both! At frontline rebel forces formed

Fathers bravely relented Wrestling foreign forces alone there was not much of a choice food, schoolbooks, legal papers

In Nana’s colorful hand-sewed suitcase from cradle to coffin one purpose and only one

From remnants in unified rage to rise above mines and guns one step after another fleeing death on feet until the sky appears overhead towards foreign fields able to bear Wounded identities and weeping hearts beyond the borders of the homeland where our humanity was crossed out

19

Shano Mohammed is a rising second-year student in the MAAS program. See page 20 to read a personal essay by Shano.

STUDENT FEATURE بﻼﻄﻟا ﻦﻣ صﺎﺧ Student ea ure (Wissam)

Arise from Flames Woodcut by Art Hazelwood Courtesy of the AlMutanabbi Street Starts Here project

DISPATCHES Notes From Abroad

Life Beyond the Borders

by Shano Mohammed

I was born in March 1991, at the back of a lorry carrying nearly 100 women and children fleeing the horrors of Saddam Hussein’s regime. My life started amid the Kurdish uprising in Iraq, during which my family sought refuge in the Kurdish region of neighboring Iran. Being born under these circumstances, in war-torn, conflict-ridden, indeed blood-soaked Kurdistan, shaped my life and colored my personality in ways that I continue to discover every day.

My mother was forced into a marriage at the age of twelve, to an older man, who abused her for sport. My faint memory of home is of the recurring cries, screams, aches, and pains of mother and daughters abused by father and brother, while outside the confines of my so-called home, everyday life teemed with loud explosions and airstrikes. Everyone seemed to proceed with their ordinary lives, but I could not.

As a female in a Muslim Kurdish family from the historically-disputed, oil-rich city of Kirkuk I became acutely aware of the injustices that constantly surrounded me. I also became critical of the ultranationalism and religious zealotry that was forced down my throat from my early childhood education onwards. The possibility of a different way of life, wherein we all cherish our humanity and accept our differences, became my life pursuit. In that pursuit, I developed a voracious love of reading. I read everything within my reach. Perhaps this was because of the words that my mother often recited, almost like a sacred prayer: “Look at me, you don’t want to be like me, your education is everything, go study and be something, be someone.”